‘We are now beginning to understand the full costly consequences to society of our peatland legacy. Global leaders herald their importance and action is being taken to conserve them.’

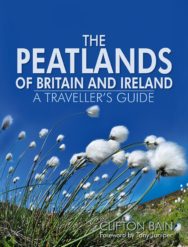

Clifton Bain’s latest book is not only a guide to the most scenic peatlands in the country, but celebrates the conservation efforts for this vital and beautiful habitat.

Extracts from The Peatlands of Britain and Ireland

By Clifton Bain

Published by Sandstone Press

Often described as the Cinderella habitat, peatlands have long been considered worthless, even malevolent, or simply a resource to exploit. Yet they are immensely important to our well-being and can display great beauty. These enchanting, saturated, watery landscapes can at first appear rather muted, with wide vistas displaying only pastel shades of browns and greens, but closer inspection reveals a wealth of colour and pattern, rich in the spectacle and sounds of unusual wildlife. This natural state of a peatland contrasts with the blackened, bare, eroding expanses that have been damaged in an often-failed attempt to make peatlands profitable. Our shocking treatment of this wonderful part of our natural environment not only threatens wildlife but has left a legacy of degradation that now imposes great cost on society as we lose the natural benefit of peatlands.

Peatlands are characterised by waterlogged conditions that restrict decay and allow dead plant material to build up over time as peat. Blanketing our mountain tops and engulfing low-lying land, peat is one of our most abundant soils, not surprisingly in such a persistently wet country. Peatlands also pervade our culture, from the drama of Wuthering Heights and Sherlock Holmes’s canine mystery on Dartmoor to the aromatic basis for whisky and the modern use of peat in gardens. Widely known, but now practised by few, is the craft of turf cutting to provide fuel in remote rural areas.

Going back over millennia, the association of people with peatlands has been uniquely captured by their excellent preserving qualities that have allowed us to come face to face with the actual bodies of our ancestors as well as incredible cultural artefacts. One of my earliest associations with peat was from my father’s bookcase in the form of a small paperback book, The Bog People by P. V. Glob, with its captivating cover of the perfectly preserved Tollund Man who had lived over 2,000 years ago. The serene, calm face belied the fact that this individual had been hanged and placed in the bog as part of an Iron Age ritual.

The peatland story is one of contradictions. Often disregarded as wasteland, peatlands are immensely valuable. Visions of dangerous, boggy swamps with their derogatory associations contrast with the reality of colourful carpets of mosses bejewelled by clear pools of water and hemmed with delicate, white cotton-grass heads.

Over the centuries, the draining and clearing of our peatlands has been one of the most extensive acts of environmental destruction ever imposed on this country. Worldwide, the situation is just as desperate in many other hotspots of human population, where extensive peatlands in Europe, America and South East Asia have been drained and exploited. Global news coverage has shown the human suffering resulting from huge fires on drained peatlands in Indonesia and Russia extending over thousands of kilometres. The economic damage from these fires was estimated at several billion US dollars.

We are now beginning to understand the full costly consequences to society of our peatland legacy. Global leaders herald their importance and action is being taken to conserve them. Huge projects are underway to repair damaged peatlands and reinstate their watery conditions, to allow wildlife to thrive and help secure the benefits we can all derive from them.

With awareness of their international conservation importance there has been considerable investment by governments and environmental charities to provide protected sites with excellent visitor facilities, offering the opportunity to get into the heart of these wildlife treasuries.

*

Peatlands’ true benefits

In our enlightened times, peatlands are seen as beneficial to society in their natural state, and we understand the costly consequences of past exploitation. Protecting peatlands from damaging development is not only preserving the past but also offering a positive future as a place to celebrate the uniqueness of rich wildlife and uninterrupted space. One of their main long-term rewards is in their natural ability to inspire, rejuvenate and re-energise people, just as they did for the ancient saints in Ireland. Across Europe, the opportunity to escape modern stresses and experience such an uplifting environment is becoming more and more challenging. With the world waking up to the importance of our peatlands, switching from exploitation to helping people enjoy the natural experience while conserving peatlands must surely be the right way to treat the goose that lays the golden eggs.

With climate change now a global priority, the role of peatlands and their behaviour as long-term carbon reservoirs has been increasingly scrutinised in recent years. There has long been a popular misconception that peatlands are damaging because they release methane, a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change. However, we now understand that peatlands are a huge asset in storing vast amounts of carbon and locking it up on millennial timescales. Methane is produced deep in the peat as a byproduct of decay by bacteria that live in low-oxygen, waterlogged situations. In a healthy mire this methane is broken down by other bacteria in the oxygen-rich acrotelm before it can escape into the atmosphere. In damaged peatlands methane emissions may be reduced as oxygen penetrates the drying out peat, but there will be continued release from waterlogged drain-bottoms and peat cracks.

Flammable methane is often thought to be the source of the eerie lights referred to in folklore as ‘will-o’-the-wisp’, ‘fairy lights’, or ‘spunkie’ in the Scottish Highlands, though it may actually be another much less common gas based on the more reactive element phosphorus that is the true source. The names for these lights nevertheless all refer to some form of evil spirit holding a flaming torch or candle that draws travellers to their doom into the dangerous bog or fen.

Since methane forms in wet conditions, the draining of peatlands was thought to be a solution to halt the greenhouse gas emission. We now know that drainage results is a far greater problem through causing the release of large quantities of carbon dioxide as oxygen enters the system and allows aerobic decay of the peat. The loss of carbon dioxide in a drained bog far outweighs any reduction in methane loss and becomes a significant climate change problem.

Across the UK it is estimated that damaged peatlands release around twenty-three million tonnes of carbon dioxide annually – equivalent to over half of all the country’s annual greenhouse gas reduction achievements in recent years. In other words, it negates half of all the climate change efforts made in industry and households every year. With over three billion tonnes of carbon stored in peat deposits, we face serious consequences if peatlands are left in a deteriorating state. International climate change policy now recognises the importance of these natural carbon stores and encourages both protection and restoration to re-wet and rehabilitate the peatlands. In future, farmers could well be paid to maintain these carbon stores on behalf of the nation.

The Peatlands of Britain and Ireland by Clifton Bain published by Sandstone Press, priced £24.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Joan Eardley: Land and Sea – Life in Catterline

Joan Eardley: Land and Sea – Life in Catterline

‘Many of her landscapes were painted less than thirty paces from her front door.’