‘It was 1930, the year of the election in which the Nazis, having polled just 2.6 per cent of the vote two years earlier, gained more than six million votes and became the second-largest political party in the Reichstag. The year in which Henry’s first memories also happen to register, soft and gauzy like dreams.’

Homelands: The History of a Friendship is a story about two unlikely friends, one born in 1970s Britain to Indian immigrant parents, and the other arriving from Nazi Germany in 1939, who was fleeing persecution. Navigating family, migration, belonging, racism, anti-semitism, grief and resilience, Chitra Ramaswamy’s new book holds at its heart how we carry our pasts into our futures. You can read an extract below.

Extract taken from Homelands: The History of a Friendship

By Chitra Ramaswamy

Published by Canongate Books

‘The mustard is running over!’

I have never been to Nuremberg. In fact, for a spectrum of reasons ranging from my autistic son to the climate emergency I have not left Britain, nor been on a plane, for seven years. But I have visited 15 Fürther Strasse, Henry’s childhood home, many times, courtesy of that most modern mode of transport, Google Street View. The routine is always the same, as if I were a resident treading a morning route to pick up a pint of milk. I click on the image and a satisfying rush towards the street takes place. I hold my index finger down on the touchpad and look this way and that, up and down the street, as if I am preparing to cross it. I examine the late nineteenth-century architecture of the building where the Wugas’ “at was located on the floor, which appears now to be the offices of an insurance company. I picture Henry and his parents moving around the four large, traditionally furnished rooms separated by heavy double doors, with the warehouse and store for his father’s stationery business towards the back. I imagine the thirteen-year-old boy with his brand new typewriter and desk, where he keeps his libretti. I imagine the room that, when ‘things got difficult’, is let to a German army lieutenant known for his friendliness towards Jewish people. A man who tries to protect the household, particularly Henry’s mother, as much as he can from regular ‘incursions’, as Henry calls them, by the Sturmabteilung, the Nazi Party’s paramilitary wing known as the SA.

My vision of all this is coloured, even contaminated, by a scene in Austerlitz. In Sebald’s novel, which must be the most famous fictional treatment of a Kindertransportee, not that there are many, the titular character is a Jewish refugee sent on a train from Prague to London as a small boy. Jacques Austerlitz learns his history slowly, in fragments, just as we discover his life story through a disjointed series of encounters with an unnamed narrator across Europe. More than halfway through, Austerlitz describes learning how his father, Maximilian Aychenwald, who escaped Prague for Paris, was wary of the Nazi threat from the start. How, visiting Austria and Germany in the 1930s to ‘gain a more accurate idea of general developments’, he went to Nuremberg during one of the annual party rallies. There, he saw for himself ‘the entire population . . . and indeed people from much further afield’, standing ‘shoulder to shoulder all agog with excitement along the predetermined route’. Maximilian watched a motorcade of limousines slowly gliding down an alley, parting ‘the sea of radiant uplifted faces and the arms outstretched in yearning’. He stood in the square next to the towering medieval Lorenzkirche, a Nuremberg landmark a couple of miles from 15 Fürther Strasse, and saw the motorcade ‘making its slow way through the swaying masses down to the Old Town’ where the occupants of the old half-timbered houses with their crooked gables hung out of the windows ‘like bunches of grapes’. When Henry tells me about Nuremberg in the 1930s, this is what I see.

Though for a few years he sees none of this. When hundreds of thousands of supporters gather in Nuremberg to watch the torchlight parades, Nazis marching with flags and swastikas, and Hitler’s long hate-filled speeches, Lore and Karl send their son away to family in Heilbronn. But one year, for reasons children never know, Henry stays in Nuremberg. He looks out of the window of 15 Fürther Strasse and sees uniformed Nazis marching ‘fifteen abreast’ down the wide expanse of his street. ‘We tried not to look,’ says Henry. ‘It was quite horrifying.’ Alice, the maid, who will soon be forced to leave when the Nuremberg laws ban Jewish people from employing female German maids under the age of forty-five, opens the double windows to lean out over the marching crowds. ‘The mustard is running over!’ she screams, referring to the mass of brownshirts seething in the street. Karl pulls her back in and quickly shuts the windows. ‘If they had heard they would have come and wrecked our “at there and then,’ says Henry. ‘How we weren’t beaten up I don’t know to this day.’

I direct the cursor along that same street, my hands long accustomed to doing the instinctive work of my feet. I swivel past two saplings to a café opposite Henry’s building. People with pixellated faces sit at the pavement tables. The number plates of the parked cars are blurred out too, as are the buildings above the café and shop next door. But Henry’s building has not been anonymised. I run the cursor up and down its stone walls. Vault over the top of 15 Fürther Strasse and the young boy’s life playing out inside it almost a century ago.

Henry’s building looks old. One has to keep in mind that when he and his parents moved in, it was new. Henry was six years old at the time. It was 1930, the year of the election in which the Nazis, having polled just 2.6 per cent of the vote two years earlier, gained more than six million votes and became the second-largest political party in the Reichstag. The year in which Henry’s first memories also happen to register, soft and gauzy like dreams.

‘Going to fetch milk from a local farm.’

‘Sunday walks in the countryside with my parents.’

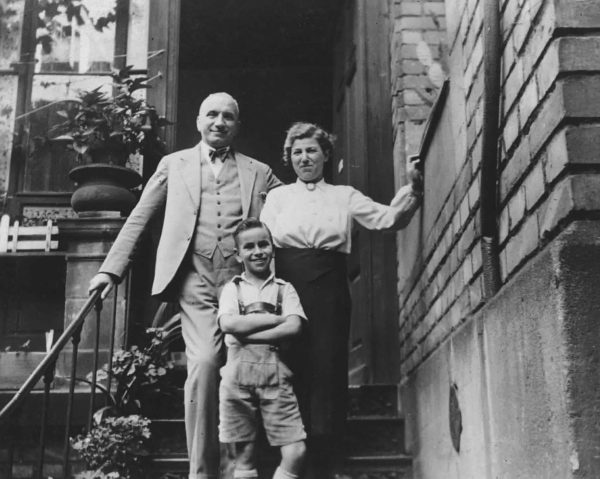

‘My father lying down for a nap after lunch with his newspaper across his face.’ Henry emails me a photo of 15 Fürther Strasse. It was sent to him by his mother after the war, and arrives in my inbox upside down so I have to turn it once, twice, in order for my brain to grasp what I am seeing. A close-up, in black and white, of the doorway of the last place in Germany Henry called home. His address. Blackened. A history in ruins.

Homelands: The History of a Friendship by Chitra Ramaswamy is published by Canongate, priced £16.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Q&A: Jim Byers and Jonathan Trew on Edinburgh’s Greatest Hits

Q&A: Jim Byers and Jonathan Trew on Edinburgh’s Greatest Hits

‘I think one of Edinburgh’s strengths is its creativity and eclectic spirit.’

Homelands: The History of a Friendship

Homelands: The History of a Friendship

‘It was 1930, the year of the election in which the Nazis, having polled just 2.6 per cent of the vo …