Having decided to walk the Antonine Wall from east to west, I was immediately faced with an important question. Where was I to set off?

Charting the voyage on foot of one of Scotland’s most fascinating ancient monuments, this is the personal account of historian Dr Alan Montgomery’s journey across the Roman frontier that has inspired myths and legends for centuries. You can read a snapshot of his journey below, exclusively on Books from Scotland.

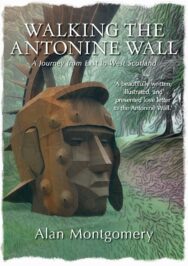

Walking the Antonine Wall: A Journey from East to West Scotland

By Alan Montgomery

Published by Tippermuir Books

Carriden to Falkirk

Having decided to walk the Antonine Wall from east to west, I was immediately faced with an important question. Where was I to set off? Although previous generations of cartographers and archaeologists have recorded much of the course of the Roman frontier allowing us to accurately map it even in places where no physical signs of it now remain above ground, the exact location of its eastern end has long been a mystery. The distance sculpture dug up at Bridgeness in the nineteenth century is still the most easterly relic of the rampart to have been discovered – beyond that its route becomes completely untraceable. I realised that I needed to do some (metaphorical) digging and look at the writings of my predecessors, the historians and antiquarians who studied and explored the Antonine Wall in centuries past, in the hope that they might provide an answer.

I soon discovered that several potential locations have been proposed for the east end of the Roman frontier, some more convincing than others. Bede’s eighth-century Historia ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum placed it two miles west of Abercorn, which would mean somewhere near the picturesque medieval castle at Blackness. Bede’s muddled references to the Antonine Wall’s history and geography, however, are full of inaccuracies, and it is likely that he never visited the monument in person. The name of Walton, a small village to the south-west of Blackness (somewhere, I assume, close to the modern Walton Farm), led some antiquarians to claim that this supposed ‘Wall-town’ must have been the spot where the frontier ended, but to me it was too far south to be a viable option.

Sir Robert Sibbald, the eighteenth-century antiquarian who spent much of his time hunting for Roman antiquities in this part of the world, believed that the frontier extended further east beyond Abercorn, but then he was convinced that a long earthwork in East Lothian was the famous Wall built by the Emperor Hadrian, so we should certainly treat his conjectures with caution. The modern Ordnance Survey map shows the Antonine Wall as a dotted line which hits the coast of the Firth of Forth on the eastern edge of the town of Bo’ness, but this is purely conjectural, and since a scruffy industrial estate next to a noisy road did not seem like the best place to start my walk, I quickly discounted that possibility.

So far, so confusing. There was, however, one other place name that I noticed in medieval and early modern accounts of the Antonine Wall. The vague and confused descriptions of the Roman frontiers in Gildas’ original De excidio et conquestu Britanniae contain no specific geographical detail, but an early thirteenth-century manuscript copy of it, written at Sawley Abbey in Lancashire, noted that the Antonine Wall ran westwards from ‘Kair Eden’. This idea was repeated by fourteenth-century Scottish chronicler John of Fordun, who wrote that its eastern terminus could be found ‘juxta villam Karedin’, meaning ‘next to the village of Karedin’.

The discovery of Roman artefacts in the following centuries in the place now known as Carriden demonstrated to eighteenth-century antiquarians that there had certainly been extensive Roman activity in the area. The village may be gone, but Carriden House and its grounds survive, loitering just beyond the eastern outskirts of Bo’ness, near to Bridgeness. Modern archaeology has confirmed that this was once the site of an important Roman military installation located at, or more probably a short distance from, the end the Antonine Wall. I knew that it was a spot with an interesting story to tell, so it was there that I chose to begin my journey.

The next question I faced was how to get there. Few people visit Carriden nowadays, I suspect, because it is not an easy place to find. The journey from Edinburgh, only 15 miles as the crow flies, would take over an hour on public transport, hopping on and off trains and buses before finishing on foot. You can drive it in half the time, but there are no signposts to point the way, and nowhere to leave your car when you get there. I ended up taking the easiest but most expensive option, catching a train from Edinburgh to Linlithgow and then calling for a taxi at the station.

The taxi driver was a friendly sort and interested to hear of my plans. He was aware of the Roman frontier, but not particularly impressed by what he had seen of it: ‘The thing is, it’s really just a ditch’, he told me, as if to prepare me for disappointment. For a moment I felt the urge to correct him, to explain the unique qualities of this ancient wonder, but in the end, too polite or maybe too lazy, I simply nodded, smiled and changed the subject.

The taxi dropped me off on Carriden Brae, north of a cluster of cottages known as Muirhouses, where a lodge house sits at the end of a long, straight drive. I walked down this drive, past an abandoned eighteenth-century kitchen garden, once filled with fruit trees and vegetables, its worn and fractured brick walls now offering shelter to nothing more than long grass and weeds. Carrying on through woods, I passed a group of outbuildings, an old stable block recently converted into houses by the look of it, catching glimpses of a larger building hidden further back in the trees to my left before I emerged into an open field.

The harvest had recently been gathered, leaving behind only a rough stubble of straw poking out of the broken earth, a soil that the Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland of 1884 described as ‘generally light and early, capable of producing good crops’. I stepped off the tarmacked road and onto the field, through a dark, soggy patch where lines of tyre tracks ended their sinuous routes through the golden stalks. My walking boots, worn in on London streets, finally got a taste of Scottish mud.

My arrival clearly came as something of a shock to the local wildlife. A small brown bird, a female pheasant perhaps, instantly took fright and tottered anxiously across the open ground towards the safety of nearby bushes. Seconds later a rabbit sprang to life, briefly breaking its camouflage as it hopped into a clump of long grass. And then, well nothing much, just the soft sound of the wind in the trees and light clouds sailing across the late summer sky, some darker outliers to the north sliding ominously towards me, bringing with them the threat of summer showers.

Walking the Antonine Wall: A Journey from East to West Scotland by Alan Montgomery is published by Tippermuir Books, priced £9.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

David Robinson Reviews: The Romantic

David Robinson Reviews: The Romantic

‘The fluidity and randomness of life – that great Boydian theme – are all here in abundance.’

Nasim Asl Reviews: Orpheus Builds a Girl

Nasim Asl Reviews: Orpheus Builds a Girl

‘As the story progresses, the characters’ mental states become more and more exposed and the lines b …