‘Milk became cream and cream became butter and corn became bread and peat became fire and flames and boys and girls became men and women.’

Angus Peter Campbell’s latest novel is a wonderful tale of recollection, of time passing, family and community. We hope you enjoy this extract.

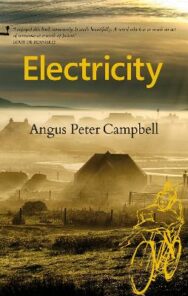

Electricity

By Angus Peter Campbell

Published by Luath Press

It was as if everything was still to be learnt, rather than already known. It took me ages, for example, to realise that birds fly by the wind as much as by their wings.

Strange to think now that electricity and aeroplanes were regarded then by some people as great dangers. Of course they were – we could all see that, in a way – but then again so was everything. You might fall into the well. A bull could gore you as you crossed a field. If you went up the hill the water-horse might get you. Lachlan MacIntosh had been drowned swimming in the sea because he refused to listen to anyone who told him it was dangerous. People fell into ditches all the time, stumbling their way home from the pub in the dark. They went there for company, to find someone to talk to. It was strange to want to be in company, and even stranger to want to be alone, so no one ever won.

Sometimes the more beautiful a thing was, the more dangerous it was. Martha in the next village was drowned trying to pluck one of the lovely purple water-lilies from Loch Challainn. She was so stupid, because we’d all been warned so often not to crawl out through the rushes to try and get them. They were so tempting though, floating ever so gracefully in the water. There were white and yellow ones as well as purple ones. We plucked the ones along the water’s edge and then took the sticky bits off and put the blossoms in our hair or sometimes in a vase in the house, even though Dad said that was unlucky. Maybe things should be left where they are anyway. We were brought up believing we should always leave things as we found them. Maybe the owners haven’t gone far – just popped out for a walk over the river a hundred years ago and will be back before evening.

Truth was that danger lay everywhere, and the arrival of electricity and the development of the local airstrip seemed to me no more dangerous than cycling downhill or when the first horse and cart or car arrived, or when the first steam boat sailed between the islands, billowing smoke out and up into the heavens. And besides, it was exciting: who didn’t want light at the flick of a switch, and who didn’t want to fly high in the skies like a beautiful bird? We could do everything instantly. When we wanted. Not when someone else decided. Be immediately on the other side of the globe, faster than on any imaginary magic carpet or any wick of straw that these daft old people at the time talked about. Who knew anything about an energy crisis as the pot bubbled on the peat stove? You can’t fathom the future by what you don’t know. You only fear it if you haven’t bothered to cut enough peats to last you through the whole winter.

***

We were conscious of a discontent, especially among some of the older folk, who feared that the imminent arrival of electricity would change everything and that the little they had would be taken from them. Things would be different, and not as they had been anymore. Already, things were getting faster and bigger and stronger and better. Old Murdo proved it by telling everyone that while a cart only had two wheels the new cars had four, so they could obviously go twice as fast. Though Mùgan reminded him that he’d seen kangaroos in Australia which, though they only had two legs, could still run faster than any four-legged sheep or cows he’d seen ambling lazily around our fields.

Who cared at the time? For life was all change, and Dolina and Morag and Katie and Duncan and Fearchar and I liked fast things.

Even as they stood still, in those long, endless days. We all dreamt of going fastest downhill without any brakes. Angela Smith held the record, though we all knew she’d cheated by taking off her outdoor clothing and shoes and doing it in just her vest and pants so that she’d be really light. There was no rule against that, but it wasn’t really fair because no one else was daft enough to go next to naked in public. Every day brought something new – Peggy making a new doll out of a wooden clothes-peg or Dolina who always picked the nicest flowers on the way to school and stuck them in a different way in her hair every day. Some days in a bunch, some days one above each ear, some days in a sort of hoop round her head. And then it was the best time of year again – time to pick the daisies and make chains. Dolina was always the best at it, splitting the stalks with her teeth and then weaving them into each other until they were just the perfect size to hang round our necks as decorations, though sometimes we all ganged up together and made one long chain that went on and on forever. Once, we made one that stretched from the school gate all the way across the playground, right over the wall and on over on the other side to the pond, and though the boys wanted to break it, none of them dared, for they knew that was bad luck and whoever broke it would die.

And we realised that seasons came and went and always looked forward to the lambs being born and then quickly forgot them in early spring time as they grew bigger when it was time in school again to play rounders, and we saw the hay and corn grow all summer long, and watched the older boys and girls grow big and tall and strong, and wondered as they suddenly sailed away to make their fortune. Milk became cream and cream became butter and corn became bread and peat became fire and flames and boys and girls became men and women.

Sometimes we got a shilling for keeping the birds off the corn. But as soon as we left, there they were again, gleaning away to their heart’s content.

Electricity by Angus Peter Campbell is published by Luath Press, priced £9.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Nothing Left To Fear From Hell

Nothing Left To Fear From Hell

‘But look again at that one scene – as far as I can tell, true to the historical record for 28 June …

Museum Mystery Squad and the Case from Outer Space

Museum Mystery Squad and the Case from Outer Space

‘Someone’s sent the museum a blackmail letter threatening to steal a prized exhibit from the brand-n …