‘Not only can [Robinson] write well, but his storytelling structure is satisfyingly complex, looping back chronologically in a way that is every bit as balanced and engineered as the rocking chair prototype he makes for his Linlithgow shop.’

In his latest review, David Robinson savours the passion for woodwork and the outdoors which exudes from Callum Robinson’s debut memoir, and the family stories that are revealed within the wood.

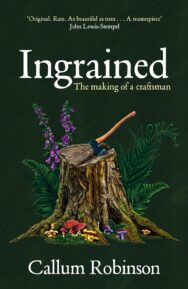

Ingrained: The Making of a Craftsman

By Callum Robinson

Published by Doubleday

Some David Robinsons are exceptional. Not me, but there’s a craftsman with the same name who lives in East Lothian and who can handle wood so well that he can produce miracles like these:

https://www.callumrobinson.org/journal/conjuring-wildlife-from-wood

His son Callum is similarly talented, though he brings different skills to the woodwork table: those of a high-end furniture maker, of an entrepreneur, and above all, someone with the skill to write well about both.

Now I know little about entrepreneurship and even less about woodwork, so I am hardly an ideal reader for Callum Robinson’s engrossing debut Ingrained: The Making of a Craftsman. I haven’t held a chisel in my hand since I was about 12 and even then my accomplishments didn’t stretch beyond making a basic picture frame. Many of Robinson’s readers may, I suppose, be equally ignorant about how extracting old or cold resin from a knot is like digging toffee from a tooth cavity, or how a last-minute slip of a knife might ruin a tabletop worth thousands. Like me, they won’t have wandered in sawmill yards full of old-growth hardwoods, have a clue how long it takes for a log to dry out (a year per inch and then some), or know that yew sawdust is as toxic as iroko dust. Let’s face it, they probably won’t even know what iroko looks like in the first place.

For all that, Ingrained held my attention throughout. Much of that is down to Robinson’s clear love of his job, his delight at working with “the ghostly, almost luminescent” sycamore, the “vivid orange” yew or “tense, fretful” cherry or the wondrous elm “the tenacious, swaggering, dandy of the forest”. We pick up on the passion, then the challenge, of turning designs into 3-D reality. All good, all interesting enough, and to those of us who have never, say, fashioned anything out of a tree’s burr knots, even enlightening.

But it’s always going to take more than that, isn’t it? Process, design, materials: this is the stuff of the specialist magazine, not something to stir the antennae of the general reader. Beautiful as Callum Robinson’s credenzas, display cabinets and travel trunks undoubtedly are – the kind of luxury goods that formed the basis of the first business he and his designer wife Marisa Giannasi had – we want more. We need what we always need: story.

And this is where Ingrained really scores. Robinson’s first business implodes when an order on which Robinson and his small team had banked on getting – enough for half a year’s work – evaporates. Suddenly, their business – built up over a decade – looks doomed. There’s no chance of an overdraft: if anything, the bank will be wanting to call in its debts. They’ll have to lay off people they care about. Selling off offcuts as kiln-dried firewood is the only thing they can think of, and even that won’t touch the sides of their debt. Bankruptcy is within touching distance.

When Robinson spots an empty shop in Linlithgow, he starts dreaming again. If they’re going to go down, at least they could go down swinging, trying to sell speculatively built furniture. It’s a gamble, and if it works at all, it will have to work quickly. But is West Lothian ready for the kind of prices they need, prices way beyond anything else on the High Street? The lease is signed, and the countdown to opening day begins. He can hardly sleep: “inside my head excitement limbers up for its night-time battle with panic.”

Tense as this is, the general reader needs yet more. The countdown to the big day is the feature of so many television DIY shows, as is the last-minute flurry of problem-solving. Put the two together and it’s still just a business magazine feature running along predictable lines.

What gives Ingrained its heft is something else altogether: its psychological honesty. Both David and Callum Robinson, father and son, seem to be rather thrawn individuals. Both have started businesses after setbacks, and Callum is honest enough to admit that, as a “frankly loathsome” adolescent, he sometimes resented both being roped into his father’s business and being unable to do so many of the tasks expected of him. For five years, he worked alongside his father: it wasn’t a conscious career, just something to do while drifting through his late teens and early twenties.

This being a Scottish family saga, many of his feelings went unexpressed at the time. When things went wrong, Callum got angry; when they went well, he kept it to himself. He has, he admits, a hair-trigger temper, mistrusts most people in authority, is useless at small talk, and almost incapable of talking instruction, even when he realises he is out of his depth. For years, he has suspected that his father, the more studied and steadier craftsman of the two, thought his son too incautious in business. It must have been galling when his dad seemed to have been proved right.

Callum, we should not be surprised to read, is occasionally exasperated at some of the people who drift into his Linlithgow shop: time wasters, sticky-fingered children, or anyone who fails to grasp that these should reflect the long hours spent designing and crafting bespoke pieces of furniture. But if all of this is ingrained in his character, so too is its corollary: a deep appreciation of clients and craftspeople who share his love of wood and woodworking. In this, father and son – who were never really far apart in the first place – find reconciliation and respect. The drifter has found a purpose, and has firmly locked onto it. “Engaging with the natural world through expressive manual labour speaks to something ancient within us,” he concludes. “Furniture-making is as fine a way of making a living as there is.”

Impressively, the craftsmanship on display in this book isn’t all about woodwork. Although there are a couple of pages of sources and acknowledgements at the end, within the text itself, there’s never so much as a hint that Callum Robinson ever had any ambitions to be a writer in the first place. Yet not only can he write well, but his storytelling structure is satisfyingly complex, looping back chronologically in a way that is every bit as balanced and engineered as the rocking chair prototype he makes for his Linlithgow shop.

“From such crooked timber as humanity is made of,” Kant famously observed, “nothing entirely straight can be made.” We general readers are quite happy with that: straight is straightforwardly boring. Things that are knotted and rounded and crafted and complex – like David Robinson’s table otters or his son Callum’s memoir – are infinitely more enjoyable.

Ingrained: The Making of a Craftsman by Callum Robinson is published by Doubleday, priced £22.