‘It was no lie. We were all sorry. The whole world had lost him. And the whole world had come to mourn its loss.’

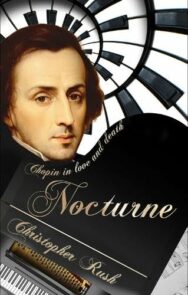

Christopher Rush is a fantastic writer of historical fiction that centres on artistic genius and his latest novel explores the love life of Frédéric François Chopin.

Nocturne

By Christopher Rush

Published by Sparsile

Journal of Eugene Delacroix

Entry for 9th February

I have just returned to my studio after a long tiring day working in the Chapelle des Anges at Saint-Sulpice, and my faithful Jenny has handed me a letter informing me of the death of Miss Jane Stirling in Scotland three days ago. I was not close to this lady, although I knew her well enough through Chopin, but the news has saddened me, partly because any story of unfulfilled love and longing is a sad one, but more so because the letter has revived the terrible memories of ten years earlier, when poor Chopin was taken from us and we were left like paupers to mourn our loss, no one more so than Miss Stirling, although I was cut to the quick by my own grief for the passing of the best man I have ever known, and of whom I think so often, now that I am no longer able to see him before me in this world, nor hear his divine harmonies.

I last heard them at his funeral. It was 30th October 1849. A clear sky sparkled over Paris that morning, nothing like the rainstorm during which the remains of Mozart only six decades earlier had been slung into an anonymous hole in the ground in Vienna, the downpour turning the quick sprinkling of quicklime to burning mush, rising like a mist from the uncoffined corpse.

This was so different. A classic autumn crispness prevailed, the sort I love to feel at my dear retreat at Champrosay, where I drink the air like white wine. Even here in the city you could hear deep inside you the sharp still sounds of the dead seasons turning over. Miss Stirling confessed she felt it too. She knew nothing of Champrosay, but I remember how she said to me that she could hear the stubble fields of her native Perthshire, back home in Scotland, piping farewell to the earth, echoing the blue emptiness, all the air suddenly becalmed between being and non-being. When she said that, I felt an instant wish to return with her to Scotland, and paint that sound, that feeling, express it as Constable would have done. But I’m no great traveller, and I’m an old man now. I know I never will.

She said something else too. She said she felt something deep in her belly, something deeper than grief.

‘It’s as if I were having a baby,’ she said. ‘His baby.’

It was an odd remark to make on the day of his funeral, but I understood what she meant.

‘I can hear it crying, you know. But it’s the unheard cry of a stillborn baby, one that is about to be buried. It’s the sound of that stillborn love being laid to rest, a love that should have been mine.’

At that point I must confess I wondered if she was deranged. Grief can unsettle the emotions and even unhinge the faculties. I was slightly embarrassed and murmured the usual platitude that I was sorry for her loss. It was no lie. We were all sorry. The whole world had lost him. And the whole world had come to mourn its loss.

The pallbearers stood up and I joined them as arranged, as we all came forward, ready for our burden. I knew that the massive casket far outweighed what it contained, the pathetic six stones of his remains, all that the long years of dying had left of him, all that could die of Frédéric Chopin. He’d been dying all his life.

The procession moved east, following the boulevards, skirting the slums, the sleepy whores, all the way to Père Lachaise. We inched away, stepping back a little from the grave, our pallbearers’ work done. In the end they throw dirt over the dead head – that’s the end of every story – and you have to turn your back on the place of tombs and walk away. I knew I’d never walk away, not in my heart. I knew Miss Stirling would never walk away either. The love of his life, so-called, Madame Sand, did not form part of our close circle of grief. She deserted him in death as she had in life.

As for me, I was in no mood to stay and suffer the interminable handshakes and mumbled platitudes of that vast crowd. I was only too glad to get back to the studio and to collect my thoughts. Jenny produced a wonderful capon she’d brought from Champrosay, cooked with enough garlic to put a whole company of British Grenadiers to flight. What a housekeeper I have! We dined on it together. Afterwards we had coffee, and to put me to sleep I took with me to bed a large glass of cognac. It unlocked all the doors in my brain, door that opened on the past, and all night long my dreaming head was filled with my friend Chopin.

Nocturne by Christopher Rush is published by Sparsile, priced £20.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Specimens by Mairi Kidd

The Specimens by Mairi Kidd

‘We took his body out the coffin,’ William said, all in a rush. ‘Myself and Hare.’

The Book … According to Malachy Tallack

The Book … According to Malachy Tallack

‘The most beautiful books are often those that make you look anew at something that previously felt …