David Robinson Reviews

‘Of course, writes Kennedy, there has to be justice. But there has to be mercy too “because the acting out of mercy cleans and saves us all.”‘

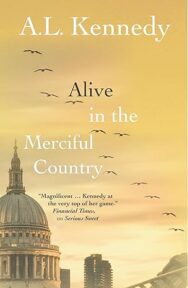

A new novel from A. L. Kennedy is always cause to celebrate, and Alive in a Merciful Country is a a great reason to run right to your nearest bookshop. David Robinson finds the novel ambitious, full of imagination and deeply human.

Alive in a Merciful Country

By A. L. Kennedy

Published by Saraband

On the verge of lockdown, Anna McCormick is teaching her Year Fives at Oakwood Primary School all about Rumpelstiltskin. They’ve made masks, wondered whether it would be possible to spin straw into gold, and worked out what kind of dance he might perform as he sets the princess the seemingly impossible task of guessing his name – which, as you might remember from your own time in Year Five, is the only way for her to avoid having to give him her first-born child.

A. L. Kennedy, herself the child of a primary school teacher mother, makes sure that Anna has no doubts about the importance of her job: ‘I am the person who keeps your society working right from the start, who tries to make sure it isn’t full of broken people.’ Working at Oakwood Primary (motto: ‘There’s always a bright side – we just need to find it’), living in a Victorian coachyard flat she adores in central London, she has a spectacularly good relationship with her 19-year-old son Paul, who matches her for both idealism and banter. Then there’s her website designer boyfriend Francis; even someone like Anna, a habitual worrier, knows that this is love. On their first night together, she confides to her diary, ‘it’s as if you’ve had an open cupboard door swinging back and forth while you walk about and now it’s comfortably closed and snug, and nothing important will fall out, not ever again.’

Happiness, two kinds of unwavering love, a job rooted in hope: this isn’t normal A. L. Kennedy territory. Where has all the nuance gone? The layers of pain? The caustic social commentary? The emotional complexity, the wry, self-aware, pared-down stories we’re used to her sending spinning like a fairground waltzer?

They’re all there, it turns out, lying in wait in that sentence I began with. Because back in the 1980s, long before Anna McCormick became the undoubtedly excellent primary school teacher she now is, she was in a group of radical clowns, musicians, street theatre performers and acrobats who went under the collective name of the OrKestrA. They were the kind of troupe you’d see playing in Hunter Square on the Edinburgh Fringe, more Merry Pranksters than any kind of serious revolutionary threat to society. That didn’t, however, stop them being infiltrated by a police undercover agent. He has many aliases, but here we’ll just call him what Anna calls him most of the time – Buster.

Buster busted up the OrKestrA. True, he had charisma and was good at his role in the troupe as the deadpan silent film star they nicknamed him after, but he betrayed Anna on every level: he was never who he said he was, and his whole life – and his relationship with her – was a lie. Now, all these years later, when the country is under Covid lockdown, he sends her an unsigned letter in which he confesses to all the various deceits – and far, far worse – that he subsequently committed.

Separately then, both Buster and Anna are looking at and writing up their past, the way so many people did in lockdown, trying to make sense of their lives at a time when time stilled and the future looked fuzzier than ever. For Buster’s narrative, not only are the typefaces different, but so is the language. When Kennedy first shows us what has happened to him, it’s already 2016 and (we later learn) he has spent decades living under assumed identities. It takes the reader a while to realise this. At first, all we know is that he has disguised himself as a security systems employee in order to assassinate a plutocrat in his mansion in the New England woods. Kennedy makes him think in a way which is more than half robotic:

‘The breeze kicks sudden wicked. We are in a cold snap since two days past and the final autumn foliage rags are curled in on themselves and murdered with the new chill and dropping thick on the ground. I am cold but do not make this personal because then my skin will form memories and skin memories are hard to shift.’

At this stage, because Kennedy has still left the cupboard doors of her plot swinging back and forth, the reader’s brain is starting to fizz, almost as if we are seeing two completely different films at the same time – say, Sally Hawkins in Happy-Go-Lucky for Anna and Michael Fassbender in The Killer for Buster. The exploded text in the Buster section (‘foliage rags’ etc) adds that extra frisson that only a novel can do, forcing us to become more attentive to his storyline, although the more used to killing he gets, the more ordinary his language becomes.

Buster takes on and discards identities as a vigilante at will, killing some very obvious Bad Guys (that New England plutocrat was also a sex trafficker). We follow for all the obvious reasons: a) will he get found out? b) what links the victims? but, most of all, c) what’s a serial killer doing in an AL Kennedy novel in the first place?

Already, though, she has told us. Or rather, Anna McCormick has told the Year Fives of Oakwood Primary. That story about Rumplestiltskin, she said, has been around for not just hundreds of years but thousands (4,000: Dr Google agrees). It’s something we all need to know: that the way to defeat all monsters is by knowing who they really are.

Stiltskins, or monsters, are all around these days, not least in post-Brexit Britain, which as Anna points out in her diary, is ‘a little triggering for people like me’. A little? To Anna, the spy cops were only the start of it. Arts funding cuts were made ‘because chaos is profitable and worshipped in myths about genetic superiority’. These days, caring enough about other people ‘to organise food for the hungry, or to advocate for breathing, or clean water or similar luxuries will mean you automatically anticipate surveillance and malign interventions.’ Education ‘is on a Strasbourg goose process – forcing the low-grade corn and keeping them caged and docile.’ Then there’s Twitter, which mainly consists of ‘enticing mistakes that will eventually drown out everything that’s true’. The police don’t help, what with their burglaries of ‘troublesome households, political households, questioning households – burglaries that were cop intrusions and feral surveillance squad intrusions and messing with your head intrusions for cop fun.’

To Anna, Covid is a Stiltskin playground. ‘They kill us for not being them and to make themselves feel special, but they dress it all up in the pseudoscience of mass infection and dreams of genetic superiority’. Still, at least Oakwood Primary isn’t a state school, so they can all wear masks ‘because no health minister can bully us. He picks on council kids.’ Even when the government insists that teachers wear masks, Anna says, it’s just another Stiltskin trick.

Much of this is her obvious paranoia, seeded by Buster’s betrayal, but some isn’t. Either way, Anna can’t show any sign of despair to her young charges. She may be convinced that, outside of her own cocoon of love, she is living in ‘an age of fury and Russian roulette’, but the world has to be made better than it is, and Year Five at Oakwood Primary is as good a starting point as ever. So as well as telling them about Rumplestiltskin, she also tells them a story based on a hadith collected by Imam Muhammed al-Bukhari in the ninth century about a man who has murdered 100 people. He can’t be forgiven, he is told, unless he reaches a merciful country. There is such a country, but it is hard to get to, and the murderer has only just reached its border when he dies. His body is only halfway across that border, but God moves the whole world to make sure that all of it is safely inside the merciful country, where his sins can be forgiven.

Of course, writes Kennedy, there has to be justice. But there has to be mercy too ‘because the acting out of mercy cleans and saves us all.’ Hence the novel’s title, which for most of its 408 pages is heavily ironic. It might be hard to imagine now, so far our society has fallen so far from where it should be, but in the merciful country, even Stiltskins can be forgiven.

Alive in the Merciful Country by A. L. Kennedy is published by Saraband, priced £18.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

This Is What You Get by Iain MacLachlain

This Is What You Get by Iain MacLachlain

‘Aa those who’d been equipped in this buildin an had been sent awa tae break their kit in. Tae be to …

The River by Craig A. Smith

The River by Craig A. Smith

‘Seven ghosts had been visiting his dreams; some pleasant, some not so much.’