‘I wanted to explore themes of loneliness, masculinity, mental health and trauma as well as how easy it is for boys and young men to be preyed upon by toxic ideologies like that of incels.’

We don’t know about you, but we’ve been excitedly anticipating Chris McQueer’s first novel ever since we read his first short story collection, Hings. And it’s here at last! We spoke to Chris McQueer about Hermit and its themes.

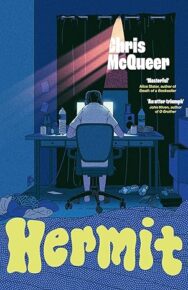

Hermit

By Chris McQueer

Published by Wildfire

Congratulations, Chris! Your debut novel, Hermit, is about to be released. Can you tell our readers about it?

Thanks very much! It’s a rotten little book about a mother and son, Fiona and Jamie, and how their already strained relationship gets worse as Jamie is groomed into the incel world. Fiona has been dealing with the aftermath of leaving an abusive relationship with Jamie’s dad, while Jamie has slumped deeper into a depression and online escapism. Lee, Jamie’s only pal, has already had his brain poisoned by an older incel, Seb, who lives down in London and now he’s doing the same to Jamie. With Jamie at rock bottom, he’s an easy target. Soon enough, Seb encourages the two boys to come down and join his ‘commune’. Of course, it’s absolutely nothing like what the boys are hoping for. I wanted to explore themes of loneliness, masculinity, mental health and trauma as well as how easy it is for boys and young men to be preyed upon by toxic ideologies like that of incels.

How did the writing experience compare to putting together your short story collections?

This was a very different experience. One I really wasn’t prepared for, to be honest. My first two short story collections, Hings and HWFG, were so fun to write and I felt there wasn’t any real sort of pressure on me; I was just trying to write daft stories that me and my pals would find funny. But Hermit was something else. I found it difficult not just because of the subject matter (which was fascinating but depressing to research), but because a novel is such a different beast. I’d spend anywhere from a couple of days to a few weeks on a short story, and I thought, in a quite astonishing display of hubris, that a novel would only take a few months, max. How wrong I was. Four years went by and I still just could not get it right. It was so hard to keep track of the different plot threads, the characters’ journeys and even just stuff like the logistics of getting them into the same room at the same time. With a short story, if you want to change something to do with the plot, it’s normally easy enough to sort out or rewrite completely. With a novel, you change one thing in the middle and then you have to go back tens of thousands of words to make it make sense. Trying to get the plot into place felt like trying to staple jelly to a wall.

You mention in your press release that your original idea of apocalypse morphed in the writing to what the book is now. How does a writer know when to make the switch?

Aye, the original version of what would become Hermit was an end of the world novel. I had the characters of Fiona and Jamie from the very start, and I thought an apocalyptic story would be the best way to tell their stories and explore their relationship. The idea was these two people, both hermits, trying to survive after a devastating nuclear bomb goes off in Glasgow. It just didn’t work though. The end of the world stuff felt like unnecessary background noise and distracted from the real interesting thing which was these two sad, lonely and traumatised people. It’s hard to know when to make the switch, I suppose. Maybe another writer would have persevered and made the end of the world angle work but I’m quite ruthless – if I don’t like something in my writing, or I’m not enjoying writing something, I tend not to try and fix it, I just delete and start again.

Did the pandemic lockdown help you understand your characters?

It definitely did. I’ve always been a wee bit of a loner, by choice, so I felt I had a relatively good handle of what it was like to just stay in all the time the way Jamie and Fiona do. But through the pandemic it was a different sort of isolation I suppose. Forced isolation. Which was tough to deal with for everyone, including me.

Can you tell us about your research into online incel culture?

I did a lot of research and it was all horrific, I have to say. I spent a lot of time on youtube watching documentaries about incels, as well as content made by them, to get an understanding of what could turn someone into an incel. I trawled through their forums to get the language and opinions right. As well as that, I read a lot about different mens rights groups. There are bits in the book, where Jamie’s reading these incel forums, that are loosely based on actual posts. They’re shocking and horrible to read, but they’re nowhere near the worst of what I saw in these sordid corners of the internet. I think it’ll maybe upset people to hear me say I feel sorry for some of the boys and young men I saw interacting on these forums. From what I saw, I think there really is a lot of grooming going on – slightly older guys enjoying a sense of power over, often very vulnerable, younger guys. There were more than a few posts which mentioned growing up in horrifically abusive homes, in poverty, dealing with learning difficulties and physical disabilities, just wee guys who’ve been dealt an unbelievably bad hand in life who are thinking this is maybe the only community that’ll have them, a chance to not feel so lonely, and before they know it, they’ve had their brains poisoned with this bile. That’s not to excuse their behaviour or abhorrent attitudes towards women in any way. I think it shows how devastating the cuts to mental health services in this country and beyond have been, as well as showing that there’s a huge amount of work to be done, by men, to talk to these boys – their sons, their friends, their brothers, their cousins, to make sure they’re okay, to lift them up, to challenge them on their views and to be the role models they need.

Though you write about dark subjects, you’re known for your humour and surrealism too. How do you balance the right tone in your writing?

I’ve always loved writing daft, weird stories and trying to make people laugh. I did initially want to write a funny novel, more in keeping with my short stories, but I found getting into the nitty gritty of a character’s mind much more enjoyable. There’s humour to be found in just about everything, and I think some of that came through in Hermit but maybe not as much as people might think. I still hope they’ll enjoy it, though.

What are you looking forward to reading in 2025?

Callum McSorley’s Paper Boy, Karen Campbell’s This Bright Life, Tim MacGabhann’s The Black Pool and We Do Not Part by Han Kang.

Hermit by Chris McQueer is published by Wildfire, priced £18.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

I Don’t Do Mountains: A Q & A with Barbara Henderson

I Don’t Do Mountains: A Q & A with Barbara Henderson

‘I took to heart the advice from children’s author Helen Peters: ‘You can NEVER have enough jeopardy …

Beautiful Ugly by Alice Feeney

Beautiful Ugly by Alice Feeney

‘Our adventure might have had a tricky beginning, but this is beautiful, and I experience something …