‘My late dream that night contained the image of a young footballer in a blue top, ceaselessly scoring the same goal, but on turning to receive adulation from his fellow players is reminded that he is dead.’

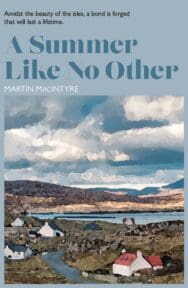

Step back to the summer of 1978, where young Colin Quinn finds himself on South Uist with his charismatic uncle, Ruairidh Gillies in A Summer Like No Other by Martin MacIntyre, the English translation of his acclaimed Gaelic novel Samhradh ’78. Enjoy this extract with lovely nostalgic detail!

A Summer Like No Other

By Martin MacIntyre

Published by Luath Press

The moon suddenly broke through the murky sky and spilled through my back window. I had a look out, wondering too whether to have a last cup of tea and slice of toast – both from newish appliances – but the illumined fields held my attention. Their sepia wash conjured daytime vigour gone-by rather than today’s empty waiting evening.

Then a thud against the loose wooden frame threw me back a few feet. ‘What the…?’ My first thought was of a dead body unloaded and allowed to fall under my very nose, but the preceding silence pointed against this. A gormless, toothless, goat-grin pushed my humour more than it should have.

‘Thalla!’1 I screeched, lifting the windowpane. The billy darted backwards then forwards again, as if mimicking a dog. It wanted me to play – perhaps throw a ball like that poor woman’s collies. Unusual for Ruairidh to leave the gate open. My cool enquiries outside confirmed he hadn’t. The wily beast had slipped through a barbed gap in the fence. It did though exit through the gate. I made sure of that. But who kept goats in Eòrasdail?

While 1971, the year of my thirteenth birthday, will forever be linked to Creamola Foam – mostly orange – 1978 was the summer of lemon curd. I had tasted the stuff before, but it wasn’t something my mother ever purchased. Ruairidh had got it in for me on Ealasaid’s recommendation. This surprised me a little, as the homemade jams at Duns had been so varied and plentiful; but, of course, while much lauded by Ruairidh, these really had been the ‘preserve’ of Aunt Emily.

I remember laughing at this unexpected, unintentional, pun and wondered if I might slip it casually into conversation with my uncle. Given our earlier encounter with Jane MacDonald, perhaps it was better I didn’t prod memories of his late wife’s prowess, or risk offending him, when I was greatly enjoying lathering my toast with Co-op bought goo.

A bit strange, I thought back in the sitting room, that someone as able as Emily never returned to work after she’d had Iona, the elder of my cousins. Had running everything connected to hearth and home provided as much satisfaction as a busy hospital job? Neither daughter had chosen medicine. I wondered whether this was a consequence of their mother’s decision or more from having lived with Ruairidh.

In the living room, I’d stretched up to turn on the radio for the headlines when the front porch door opened. While swivelling the aerial, I learnt that a previous despot’s life had just been ‘ended’ in Comoros. Where exactly was this troubled country, I wondered, as muffled sounds slunk through Taigh Eòrasdail’s passageway?

And what might be the impact of the other news: that Labour, and not the SNP, would now represent Hamilton in Parliament – even though the bi-election was brought forward to accommodate the World Cup? No, none of my uncle’s usual brisk movements or a hummed or whistled tune were in evidence.

The programme finished, the pips played out in full signalling 11.00pm, and we were well beyond Rockall in the Shipping Forecast, before I heard a hand on the opposite side of the door. At first it failed to open – that worn brass handle could slide a little, even without the help of errant butter or lemon curd.

‘Ruairidh?’ I shouted, leaping to release the latch from my side. My uncle half-stumbled, half-fell, through, still in his coat and hat. Tears filled his normally lively, now-dulled, eyes.

‘He was almost gone, Colin.’

‘Alasdair mac Sheumais Bhig? O dear…’

‘No! Stuff him and his poisoned-dwarf minder. The wee fellow. Anna Morrison’s new baby.’

Ruairidh suspected a near cot death, the child being blue when his frantic father ran into Daliburgh Hospital at 9.00pm. He had fed well, exclusively on the breast – despite the pressures – and had shown no change in character all that day. Plenty wet nappies. No unusual or prolonged crying. No signs of a cold or fever. Nothing. Anna had placed him on his tummy like all his brothers and he’d slept contentedly without a fight.

‘They’ll have to do further tests in Glasgow’s Yorkhill, look for some sort of underlying condition. Having a child die on you is horrible, a Chailein!’ My uncle’s last sentence in Gaelic: mìchiatach, the descriptor. ‘By the grace of God, or some sixth sense, I popped in on my way home from an old dear in Kenneth Drive. Of course, Eric Adams rushed down and stayed. His wife arrived later with soup and a new shawl, a lovely gesture. The family were in total shock. You still on the lemon curd? Well done, a laochain.’2

How might it have been for Uncle Ruairidh, I considered, while tossing and turning on the pillow, to have come back to an empty house after such an incident, especially if the baby had died? To sit there where I had been sitting – a widower alone with his mortality and the bleak unyielding rhythm of the Shipping Forecast? Ruairidh needed me now, no matter what happened with the bold Jane. He might though ban me from trying.

My late dream that night contained the image of a young footballer in a blue top, ceaselessly scoring the same goal, but on turning to receive adulation from his fellow players is reminded that he is dead. ‘Tha sibh michiatach!’3 he screams and tries again.

- Scram!

- lad

- 3. You’re all horrible!

A Summer Like No Other by Martin MacIntyre is published by Luath Press, priced £10.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Witch, the Seed and the Scalpel

The Witch, the Seed and the Scalpel

‘Witchcraft,’ said Father. ‘It is said that should any person catch the falling chestnut before it t …

Muckle Flugga: A Q & A with Michael Pedersen

Muckle Flugga: A Q & A with Michael Pedersen

‘My Muckle Flugga, though based on the real life Muckle Flugga we swooned over, has perhaps grown to …