‘She is still walking but he has stopped. She turns to find that he is waiting for a response to something and only now does the essential oddity of his story start to hit her.’

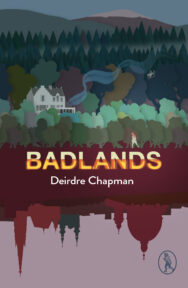

Badlands by Deirdre Chapman is a literary thriller that looks at memory, guilt and family secrets. In this extract, Charlotte has travelled to a solicitor in the Highlands to hear about the will of her great-aunt who lived and died Vienna. While there she encounters a strange man . . .

Badlands

By Deirdre Chapman

Published by Vagabond Voices

‘Is there a hotel here?’ she asks. The barman, proprietor, whoever, raises his head from polishing a glass and tilts it towards the ceiling which has not been painted since the introduction of the smoking ban. ‘This is a hotel,’ he says. ‘The Claymore.’

He is waiting for a reaction but all she can imagine happening upstairs is a flophouse for over-the-limit drinkers and a breakfast of fried things, black pudding, bacon, bread, token tomato slice. If he owns the taxi and the bar he will also own the hotel.

‘Is there somewhere . . . quieter?’ she says into the silence. It might get noisy at night, most pubs do.

‘Achindarnoch House Hotel.’ The voice comes from somewhere along the bar. She picks out the bright ginger eyes of her bus informant, breaking ranks. The barman/proprietor shoots him a look. She aims a smile in his direction.

‘Is that in walking distance? Can you give me an idea of what it’s like?’

‘Upscale traditional,’ says a voice from behind her. It’s the newcomer in the flash parka. He picks up his glass and brings it to the bar. ‘Picturesque situation. Ensuite facilities, tea and coffee kit, internet connection, dinner inclusive deals. A little draughty.’

‘You’re staying there? Could you direct me?’

‘I can take you,’ he says, and setting a three-quarter-full glass on the bar counter he nods to the company and ushers her decisively through the dodgy door.

‘Outside sleet is still falling. She pauses on the pavement to fasten her coat and to suss out what she’s getting herself into. He is looking away, avoiding her gaze.’

‘Are you on holiday?’ she asks as they set off. Nothing about that seems probable.

‘I shouldn’t think so.’ He is facing ahead as he says this so she can’t see his expression. They pass the butcher, the bank and the undertaker walking in silence and as they approach the doorway of MacMillan Partners he takes her elbow to steer her across the empty street. They pass a newsagent – he glances at a billboard outside it – then a school with an empty playground. She tags all these as landmarks in case the village up ahead erupts into urban sprawl. But the pavement is narrowing here and seems likely to run out here at the mountain end of the village. The road forks and they are clear of buildings so, she thinks, a country house hotel. ‘You see,’ he says breaking a long silence but without breaking his stride, ‘I’ve lost my memory.’

She slows – better not to stop – and turns up her coat collar, glancing back at the solicitors’ office, wondering if she should make a dash for it. This feels, after an hour spent among glamorous ghosts, all too real. His silence was calculated, his voice is serious.

The High Street, now that she’s leaving it, seems a place of charm. She has slowed the pace further, half-turning from time to time as if she might be weighing up her options, country hotel versus high street, but his hand comes up to cup her shoulder and turn her towards a right fork like a date he’s steered into his choice of bar.

‘And I’m counting on you to help me get it back.’

It’s quite a hike to the Achindarnoch House Hotel and he is using the time to sell the primacy of his predicament over whatever boring back story she might have. Distant traffic sounds reach them from the A road she saw signposted but now they are walking along an erratically surfaced road with trees closing in on either side and something is drawing her onwards more urgently than he is steering her. The place is beginning to talk to her, drowning out most of what he is saying. Once this tiresome escort duty is over and before she returns to her travel options she will explore these surroundings. But as they arrive at a pair of handsome gateposts leading to a tree-lined drive a thought strikes her.

‘Why me?’

He stops and looks at her as if she is being deliberately obtuse. ‘You’re a stranger here. You can’t be involved. Can you?’

Involved in what? As they start up the drive, crunching along a carpet of mulched tree debris it’s the ‘can you?’ that she’s hearing, a bleat of self-doubt in an otherwise unvarying and uninteresting account of the hotel layout and his exit from it. For the first time he is wondering about her. Like, who is she?

Who indeed? By-product of nineteenth century economic migration, refugee from light opera in far too many acts. Bit of a hybrid, bit of an orphan if she was inclined to see things that way which she is not.

The question, though, must have been rhetorical because he hasn’t waited for an answer. He is telling her in some detail of his escape from the hotel. He watched from his bedroom window as the hotel proprietor who was wearing a kilt saw off two groups of guests from the car park. Once they had gone the hotel proprietor had glanced round furtively then moved into a small clump of trees where he took from his sporran a pipe and tobacco, a pipe-smoker in denial, giving him the chance to escape the building unseen and find his way out of the grounds to the high street and the sanctuary of the pub.

The building coming into sight puts an end to what’s left of her attention. It’s a converted shooting lodge, she guesses, set in a huge wild garden, protected by a stand of trees she recognises, can even put names to. Beyond the hotel is the end-of-the-village mountain. All this – the building, its grounds, its trees, the scent that is pine resin, the other that is wood smoke, the non-metropolitan bird that shrieks and gets an answer – is familiar.

She is still walking but he has stopped. She turns to find that he is waiting for a response to something and only now does the essential oddity of his story start to hit her. ‘Why didn’t you just’ – he has turned away and she waits till he resumes eye contact – “I don’t know, just go to the reception desk and tell someone?’ He’s been holding out on her. Or she hasn’t been listening. Now he has all her attention.

‘There’s someone in my room.’ His voice is calm and rational. ‘A woman. She’s dead.’

He holds her gaze in a manner that, as the implications sink in, is clearly intended to reassure. She keeps her eyes on his and in doing so turns this into a two-way transaction in which she will take the lead.

‘A young woman?’

‘I’d say so. Late teens, early twenties.’

‘Natural causes?’ She diverts her gaze to the beech tree behind him.

‘I would think not.’

‘Did you . . . do you think you might have killed her?’

‘Then wouldn’t I be feeling something? Loathing? Or guilt?’ He notices the self-validating inversion and wonders if she does.

‘I don’t know.’ She faces him again. ‘I’ve never killed anyone. Have you?’

‘I shouldn’t think so. But then . . .’

‘Did you feel anything?’

‘Distaste. Surprise and distaste.’

‘OK. Putting myself in your situation . . .’ she pauses to let that idea self-destruct ‘. . . I don’t think I would be returning to the scene. Why are you?’

This is not helpful. Questions are not what he needs from her, actions are. Before he frames the answer he will have to run it past himself. For a while now he’s been getting messages from the person he thinks he is, and this person’s need to know is off the scale, way ahead of his anxiety to save his skin. His patient sifting of the meagre facts strikes him as meticulous, well-honed, even enjoyable. And that makes him wonder.

She is still meeting his eye. If he has scared her she is still in control. He smiles and shrugs, watches himself doing that. ‘I have to find out who I am.’

Badlands by Deirdre Chapman is published by Vagabond Voices, priced £12.50.