‘I kept on reading, and then it seemed that alarm bells were going off in my head constantly. It’s a period in which absolutely unthinkable things happened.’

Poor Creatures in Mairi Kidd’s latest historical novel which looks at Mary Shelley’s time in Scotland as a teenager and imagines its influence in the creation of Frankenstein. We chatted to Mairi Kidd about the genesis of the book.

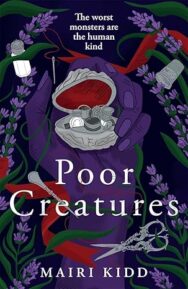

Poor Creatures

By Mairi Kidd

Published by Black & White

Mairi, I’m sure it’s lovely to see another novel of yours out in the world; what can you tell our readers about Poor Creatures?

Thank you – it’s a strange and slightly scary time, when the book becomes ‘real’ after being a file on a laptop for so long!

Poor Creatures introduces readers to a group of wild, wonderful and occasionally wretched women, all of whom lived in the early years of the nineteenth century. There’s Margaret, a seamstress imprisoned in Bedlam, and Isabel, the teenage daughter of a family of Dundee radicals. Harriet is the very young, pregnant wife of a poet trying to cope with an itinerant existence. Mary-Jane is a translator and publisher eking out a living in London and struggling with the trials of being a second wife and stepmother.

What all of these women have in common is a link to Mary Godwin, better known by her married name of Mary Shelley. When Mary was a teenager, she was sent away from home, first to Ramsgate and later to Dundee. The book picks up her story as she arrives in Scotland, and forms an intense bond with Isabel. In writing it, I wanted to do some ‘visible mending’ where there are gaping holes in Mary’s story, and invite the reader to consider how Frankenstein may have cast a shadow over Mary, and Mary in turn over the other women in her life.

What drew you to this part of Mary Shelley’s life?

The idea was actually suggested to me by my publisher. I had been in a TV programme about Mary Shelley’s links with Dundee, and then had rather put her out of my mind. When Ali McBride at Black and White asked if I thought there was a book in it, I did initially wonder whether there was anything new to say. I started researching fairly idly, and the first thing that happened was that I wondered some more about whether there was a story there, because there is a real paucity of material about that period in Mary’s life. But I kept on reading, and then it seemed that alarm bells were going off in my head constantly. It’s a period in which absolutely unthinkable things happened. A girl is sent away from home, apparently because there is something wrong with her arm. Somehow this arm issue affects her father’s trust in her. A man marries a girl half his age, she dies – we know not how – and then he marries her younger sister. A poet runs away with a schoolgirl, then abandons her and runs away with another schoolgirl. Two young women kill themselves. It’s all hugely troubling, and it seems to me that there has been a distinct lack of curiosity about these events among Mary’s biographers. Lots of things are taken at face value, ignored, or explained away. One might begin to suspect that the paucity of records could have happened on purpose…

Once all that was in my head, I decided I thought there was a novel in it after all – but I didn’t just want to focus on Mary. I wanted also to explore the other women in her life.

You focus of the kinship, loyalties, and jealousies between friends and sisters rather than the characters romantic relationships. Why did you make this choice?

There are two slightly different answers to this.

The first is simple(ish): when we meet Mary and Isabel in the novel, they are very young, and so it seemed to me natural that friendships versus love affairs would be central to their lives. We know their friendship was important to Mary because she wrote as much down; a break came later, and when they met again, Mary told people that Isabel was mad. That seems to me a pretty unpleasant thing to do to one’s supposed friend today, let alone in Regency England where reputation was all-important. That action of Mary’s makes me even surer that the friendship was quite an intense one; I see the falling-out as the flip side, the hate as fierce as the love.

The second answer is that I wonder about the Mary/Shelley relationship. Shelley didn’t believe in monogamy and there were always other women around. Some of them may have been around because Mary invited them, which is slightly disturbing. Did she arrange them as proxies? When Shelley died, Mary did not remarry and later in life she would say she became ‘tousy mousy’ for other women. I wonder whether her relationships with women were actually the major relationships of her life.

Alongside all this, I was also interested in playing with ideas of how Isabel and Mary might have – separately and/or together – started to become writers. We know Mary wrote as a young girl, but those papers were also ‘lost’.

You often write about history from a woman’s point of view, would you ever consider writing a novel in a contemporary setting? What is it about history that fascinates you?

I suppose I was pre-destined to be interested in history; my mum was a history teacher, my dad studied history, and I come from a long line of people who told stories of a type that might be called oral histories. I’m not the right person to be a historian, though, I always want to go a step further and try to imagine how people felt, how they thought – to step into their shoes, I suppose. Conjuring a world through places and things is such a lovely thing to do – it’s something historical fiction shares with fantasy, that element of world-building. It also lets us do that ‘visible mending’ trick of writing people back into the story, and for me that’s so important as women have been so badly neglected – or straight-up traduced – in traditional histories for so long. Of course it also lends us a lens to look at contemporary issues, how we have progressed – or not – and the roots of issues that may still plague us today. That’s the appeal for me.

I have written contemporary pieces for stage and TV and I have modern novel drafts at various stages from various periods in my life – they don’t half date quickly, though! I would never say never to writing about the present day; if I thought the time and the idea were right, I would certainly give it a go. The next book I’m working on is set further back than Poor Creatures, but the one after that does come forward in time quite a bit. It’s not modern, but it feels modern by comparison with my last books.

There’s a cheeky epilogue in the story concerning an old doll. Without giving any spoilers, what were you looking to explore with that addition?

I had fun writing that part. It’s partly just about the unknowability of the past and how easy it can be to overlook significance, while, simultaneously, many of us attribute all sorts of significance to old objects and may have a desire to own them – almost to ‘own the past’. It’s partly a tribute to textile crafts and all of the things women (and children) owned and made in history that haven’t been recognised as important, whether tangible or intangible. The doll appears elsewhere in the book, too, where it links to the Frankenstein idea of an inanimate object made animate. And I suppose I wanted to play with the idea of dolls as slightly uncanny. The doll is based on two separate real-life examples, one of which conceals a secret (readers can find out more in the end-notes if they wish). Oh, and it’s also my little tribute to one of my favourite books, A.S.Byatt’s Possession, but I won’t say any more on that for fear of spoilering!

What do you think Frankenstein offers the modern reader? Why is it still relevant today?

I think Frankenstein can be read in all sorts of ways. I spoke with a writer recently who saw the creature as an analogy for AI; I see him as reading across to a lot of modern bioethical debates, to the climate crisis, to the ways that children and young people – and indeed all of us – are being reprogrammed in a way by social media. It’s very human to create something, unleash it, and only then ask questions about what might happen next.

It is, of course, also a classic work of Gothic fiction and Gothic fiction is perennial; if Angela Carter was right in the 70s to say we lived in ‘Gothic times’, the modern world must be reckoned at least as challenging.

There is also something amazing about the fact that this book was written by such a young woman. I don’t think I ‘like’ Mary but I am fascinated by her and I do think she was – as a writer – a genius.

Now that we are nearing the end of 2025, what has been your favourite Scottish book this year?

That’s a tough question, there have been many wonderful books this year. In my day job at the Saltire Society, we deliver The Saltires, Scotland’s National Book Awards and I am very glad I only administer and don’t judge! I was lucky enough to go to Germany in Spring with Scottish Books International and discovered David Farrier’s gorgeously written, fascinating, clever books on the trip, so I will pick Nature’s Genius as a favourite among favourites.

Poor Creatures by Mairi Kidd is published by Black & White, priced £16.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet

Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet

‘As a result I acquired a reputation of being truculent and aloof and it may be true that I was what …

Looking Down at the Stars by Christina Riley

Looking Down at the Stars by Christina Riley

‘To say, “I want you to see this” for no reason other than the belief that it will bring pleasure or …