‘Somehow, in an alchemical process that involves stirring together vast knowledge of plants, history, spirituality, magic and local folklore, Kassabova has mastered the art of tying together the inner and outer landscapes of southern Bulgaria.’

In Kapka Kassabova’s Elixir, her latest book on her native Bulgaria, David Robinson finds an imaginative history and a fantastic landscape.

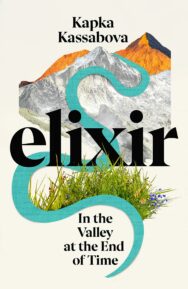

Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time

By Kapka Kassabova

Published by Jonathan Cape

THERE is a double-page map at the start of Kapka Kassabova’s Elixir which, with its uncial script, drawn mountains, and places with names like The Dark, The Village of Storks, The Birches, and Valley at the End of Time, will remind Tolkien fans of Pauline Baynes’s map of Middle Earth in Lord of the Rings. An inset map in the same faux-archaic style makes clear that we are in the southern Balkans, not Middle Earth, the Rhodope Mountains not Rivendell. Just over the border to the south is Greece, to the west is North Macedonia. We are in Bulgaria’s Deep South, which to me is a faraway land about which I know almost nothing other than what I have read in the two other books in Kassabova’s Balkan Quartet (this is the third) about her homeland.

So let’s start, as she does, in Empty Village, two kilometres south of Dogwood and five north of Thunder. Like almost everywhere else on the Elixir map, she has named these villages herself. Sixteen pages in, she tells us that Empty Village is really called Leshten, meaning hazel, and light research with Dr Google tells you that Dogwood is really Gorno Dravano and Thunder is really Garmen. This renaming persists throughout the book, but it has a purpose: nothing to do with Tolkien, but everything to do with the imagination, and the repeated overlaying of the past on the present. Strip away some of those layers, Kassabova is suggesting, and you might be able to glimpse a different land altogether, one more closely linked to nature. One where the valleys she is exploring – specifically the Valley at the End of Time, which the very real Mesta River flows through – do indeed offer the elixir of hope.

What kind of hope? Well, look again at some of those chosen double names: Dogwood, The Birches, Chestnut River. Then look at how the book itself begins. For the last ten years, Kassabova has lived near Beauly. An idyllic part of the Highlands, you’d have thought, and maybe it was until the first spring of the pandemic, when swathes of the nearby forest were razed. The local quarry was already expanding and mega-pylons had started marching out of Scotland’s largest power substation. The landscape, which had once enchanted her, had now become so noisy and mechanised that she found it hard to work (‘My blood sloshed like a river jumping its banks’). She needed to get away, to go somewhere the natural world didn’t feel quite as broken.

Southern Bulgaria is, apparently, such a place. A herbalist’s heaven, not only is it one of Europe’s leading exporters of medicinal and culinary plants, but every village seems to have its own expert plant-gatherers, healers and mystics with elaborate spells and recipes for their use. In The Empty Village – once home to 500 people year-round but now to only three – she finds herself living next door to a poet who has spent decades roaming the hills, collecting stories and recording songs. Kassabova sets off from there with the aim of doing something similar for the region’s foragers, healers and herbalists.

It’s not paradise: she’s clear about that. If it was, villages wouldn’t be empty, house prices wouldn’t have shot up a hundredfold in a generation (no, I don’t understand how those two things go together either), there’d be no gangsterism, Roma slums, or high unemployment. The scenery may be spectacular, but personally I’d rather visit the villages around Lake Ohrid, the double world heritage site (both natural and cultural) some 160 miles to the east that Kassabova wrote about in her 2020 book To The Lake. Then again, maybe that’s just me: I’ve always been more interested in history than herbs.

That said, there’s still plenty of history here too, going at least as far back as the Borgomils, those tenth century neo-Gnostics who were mocked for going around carrying two bags, one for books and one for healing herbs. And few groups of people have been quite as tangled up in history’s blues as the Pomak population of south Bulgaria – non-Turkish Muslims who converted to Islam under the Ottoman Empire – whose folk traditions Kassabova explores here.

It’s the Pomaks – persecuted by Communists for trying to cling onto their own customs and before that by their Orthodox neighbours for not being Christian – who know how to ‘bring down the moon’ (naked women at a crossroads at midnight summoning the moon’s power), how to use cuckoo-pint to fight off cancer, and how to conceive (an odd one for Muslims, this, but spending the night in a Christian church named after St George on St George’s Day apparently does the trick). Got a face rash, venereal disease or eye problems? The Pomaks have the very herbs you’ll need, but you’ll also need to know how the spell works, how the bread has to be left for the spirits, why you have to cut the plants from west to east, and what to do with the wheat and salt as you chant the magic words.

I’m a sceptic. Kassabova isn’t. Even in Scotland, where local knowledge of where to find specific herbs has often disappeared, she is a firm believer in the efficacy of herbal cures (and also, she admits, a hypochondriac). In southern Bulgaria, though, knowledge of herbs is deeper-rooted. If you want to meet the Pomak healers, work with the herb dealers, or find out the folklore behind the plants, it seems relatively easy to do so. Kassabova is also a good listener, even to women who tell her they get their secrets from ‘healers from the stars’.

So why, in the village of The Birches, does she admit that ‘all the women I met were taking tranquillisers or anti-depressants’? She would doubtless argue that this is because Communism broke the link between the land and the people, because the Pomaks’ forests have been cut down, because they were made to work on collective tobacco farms and stripped of their Muslim names and forbidden to wear their traditional dress. Yet if Kassabova can find a healer there to wave an egg in front of her face and cast out negative energy, so could the rest of the villagers. Why don’t they do just that instead of going to the doctor for tranquillisers? Come to think of it, why did those medieval Borgomils, for all their knowledge of how to use plants for healing, have a life expectancy less than half of our own?

Yet, when you’ve finished the book, look again at that double-page map. Its place-names may have been changed from those on any atlas, but nothing has been lost and much gained. Somehow, in an alchemical process that involves stirring together vast knowledge of plants, history, spirituality, magic and local folklore, Kassabova has mastered the art of tying together the inner and outer landscapes of southern Bulgaria. Elixir may well suffer the fate of being filed under ‘travel’ in your local bookshop, but it is far more than that – indeed, it makes those books whose maps use places’ actual names appear positively anaemic by comparison.

Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time, by Kapka Kassabova is published by Jonathan Cape, priced £20.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

In Ascension

In Ascension

‘In Ascension is unmistakably a Martin MacInnes novel, who with Infinite Ground (2016) and Gathering …

The Darker the Night

The Darker the Night

‘No matter how many times Fulton cast his mind back he could never find the truth. It was like a ble …