‘D.E.A.T.H. Don’t. Even. Ask. Too. Hot. Scalding. Singeing. Scorching.’

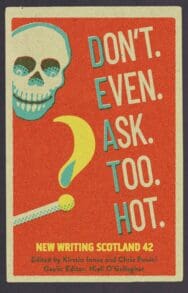

Each year, the Association of Scottish Literature publish an anthology of New Scottish Writing, and this year’s collection, Dont. Even. Ask. Too. Hot. is, once again, full of gems in prose and poetry, in English, Scots and Gaelic. Here is the powerful story that gives the anthology its name.

‘[A BILINGUAL DICTIONARY OF LOSS & MOURNING WEAVED WITH FRAGMENTS FROM A JOURNAL]’ taken from Dont. Even. Ask. Too. Hot.

Edited by Kirstin Innes, Chris Powici and Niall O’Gallagher

Published by Association of Scottish Literature

Ioulia Kolovou

[A BILINGUAL DICTIONARY OF LOSS & MOURNING WEAVED WITH FRAGMENTS FROM A JOURNAL]

Extracts A to E

[Prologue – Fragment 241019]

One month, two weeks, and three days have passed since that cold grey evening, grey September, grey streets, grey motorways – M8 ‘the friendly motorway’ not so friendly-looking just a few metres away from the entrance of the Royal – grey buses, underpasses, people rushing home after the last final shop of the day to tea and to TV. And inside, bright lights, too bright but not inside the ICU, where I see you, for one last time I see you. On your deathbed. I sit at your deathbedside. Deathbedside manner. Manner of speaking.

It still surprises me how much we people, we poor people, we poor wee people, whippoorwills, how we fear death and its apparatus and its very name.

D.E.A.T.H.

Don’t. Even. Ask. Too. Hot.

Scalding. Singeing. Scorching.

During the terrible years and months and weeks and days before, while R. was alive and he suffered and we suffered I often wished for death to come, for him, for me, for the whole world. In my head I composed funeral orations. His. Mine. The world’s. A strange consolation. Like putting a full stop at the very last sentence of a book. Like writing The End after days and weeks and months and years of hard labour. Prison. We were all prisoners then. When R. was alive and alcoholic and abusive and we suffered I fled the flat and I walked in the streets and everything looked as if it was made of iron, heavy, oppressive, unyielding. I put one foot ahead of the other, trudging on, this is it, this is how it feels to be in a hard labour camp, this heavy treading under unimaginable pressure. Composing his funeral oration is my head was a source of some comfort and relief. But now that he is dead –

I think of death and it is scary and sad, like when a terrified wife’s trying to appease an alcoholic husband. A terrified child trying to appease a violent father. Someone who was not always like that. Someone we loved and lost and found and lost.

Anakomidē

(n.) A harvest of bones.

Three years after the burial, the bones of the dead are dug up in the presence of close family – those who can bear it – and a priest. They are washed in wine and water, wrapped up lovingly in a white linen cloth, chanted over, blessed. (‘How can this small thing be his fine head?’ my mother wondered, holding my father’s skull, unknowingly evoking Shakespeare.) Then they are placed in the ossuary, in the company of all the other bones of ancestors, of friends who went before them, of fellow citizens, of strangers. They will stay in that company for eternity. Until a voice calls them to rise, and flesh and skin and hair grows back on them, ready for life eternal. Or, in another version of the future, until they are ground to dust and absorbed back into the elements, in the centuries and in the millennia to come, which is as good as eternity, I guess, for us humans, whose days are short as grass, as flowers in the field.

[Fragment 010919]

- is in hospital, dying, apparently. I saw my sister-in-law’s message at 1:30 a.m.; I was going to bed later than usual. I called her back just before 2 a.m. and we spoke for an hour. She’s staying at the Premier Inn in the city centre, near City Chambers.

Here’s the gist of it:

He was taken to hospital last Saturday and has been in there for a week, between the high dependency unit and the ICU. So far, the diagnosis is respiratory pneumonia and encephalitis. Kidneys and liver have given up. But his heart is strong, and he may yet live, although his quality of life will be very low, vegetative, more or less. They are not expecting him to recover this time; yet he may. I’m thinking of R. in a hospital bed down the road, unconscious and twitching in his encephalitis-induced sleep, the colour of mahogany, fighting for – or against – his life.

I have been expecting this phone call. Now that it’s come, it feels more like fiction than reality, a script someone wrote for some people who are not we.

Bury

(v.) To tuck the dead in bed.

Antigone, the eponymous character in the Greek play written and performed for the first time in 441 bce, dies because she refuses to leave the body of her brother unburied. Declared an enemy of the state, he has been left to rot out in the fields, a tasty treasure for dogs and vultures to find. But Antigone defies the explicit orders and buries her brother in secret. The first time, undetected. Everyone believes it’s a rebel group defying the King. The second, when she returns to complete the rites, she is caught.

How did she manage to bury him, twice, no group of hardened rebels but a girl alone against the law? She covered his body in handfuls of thin dust, she poured libations three, wine and milk and water, she wailed bitterly and tore her hair and clothes. With those acts, she performed the prescribed ancient rites, she rendered to Those Below what was theirs. For those acts, she died.

The verb for bury in the ancient text is kryptein = to hide under the earth. That’s where the word crypt comes from. A hiding place for the dead.

Elephants also bury their dead, covering them in dust.

[Fragment 020919]

I stay with R. for about an hour.

It is a strange, unreal experience to be with him in the same room and see him again after eight months. The last time we were in a room alone, he tried to strangle me, dishevelled and delirious, wild strangers lurking behind his eyes. This time the sight is not scary, not upsetting, quite the opposite, good after years of pure badness. I suppose this has something to do with the fact that he had been alcohol-free for nearly two weeks now. His skin clear from ulcers, his hands and feet soft, his fingernails long but white, not a trace of black, his beard and hair cut short and washed.

They care well for him in hospital. The unclean spirits went out. But the mark of death is upon him: his skin is thick, waxy, a deep tawny yellow, like jaundice – his liver is completely cirrhotic now. He looks a little like a prophet, all high forehead and deep-set eyes and aquiline nose and sharp cheekbones, venerable in spite of the tubes and drip feeds sticking out of his head and hands and body like tendrils.

He is peaceful, that’s why he looks good to my eyes, if pitiful in his total weakness and dependence on the machines (eighty per cent of his oxygen comes from the machine). Gone is the wild and evil look; the legion that had taken possession and peeped out of his eyes have gone; he is beyond their reach now.

Charon

(n.) Proper name, pronounced Khāron. Also Charos, or Charontas. A personification of Death. In European folklore he’s the Grim Reaper, a skeleton with an enormous scythe. In Ancient Greek mythology, Charon is the ferryman who takes the dead over the Lake Acherousia, the Black, Joyless Lake, to Hades, on a journey of no return. Coins were placed on the eyes of the dead for their fare. There is a funny story by Lucian of Samosata about a dead penniless philosopher who tried to trick Charon into returning him to the world of the living, since he did not have the fare to travel further into the world of the dead.

In the centuries after Antiquity, in Greek folk songs, Charon, who is now known as Charos or Charontas, is a splendidly dressed rider on a gigantic black horse in gold and silver harness. He has a wife, Charontissa, and children, the Charontakia. The Charon family house is filled with all the wealth in the world, which inevitably ends up there. Charon is merciless: he snatches people, babies off their mothers’ arms, young brides off the altar, strong young men, the old and the sick. He makes no distinctions of age, rank, wealth: a true egalitarian. He takes the dead, indifferent to their pleas and cries, on a miserable ride to the Underworld, where he makes them servants and slaves in his household. Sometimes they try to argue with him, but he is not as naïve as Lucian’s story makes him out to be. The World Below is the place from where no one returns.

In a Medieval Greek epic, a hero called Digenes Akritas, the strongest man of his era, fought Charon in single combat on a threshing floor made of marble. The fight went on for three days and nights. After a valiant fight, Digenes was thrashed on the marble floor.

[Fragment 030919]

I dream of people who are dead or lost to me as if they were dead. I had to walk through the sea to reach them. A cluster of sea urchins just under the surface of the water, black and spiky and perfectly round; I picked my way carefully through them, stepping on the slippery stones.

No news from the hospital. The last update, last night at around 9 p.m., was that his temperature was up a little. When I tell Mama, she says that this is a very bad sign. Bad for whom? I know what Mama thinks: it’s the best for everyone, including R. himself, that he dies. It will just be formalising something that has been happening for a long time now. The man we knew and loved died years ago. But what does that even mean? He’s still living, and he may yet come out of the hospital alive. It won’t be the first time that someone who’s been written off is snatched back from Charon’s teeth. Only, is that R. or the usurper who lived in his place these last several years?

Let me not beautify the past because R. is ill in hospital, possibly dying. He was good and loveable once. He had all the best intentions in the world. He loved me and A., he really did. But love could not conquer his self-destructive compulsion. The loving, caring, sensitive, funny, talented man was gradually replaced by the cruel, demented, selfish, soulless spawn of chemical dependency and addiction.

I tried to explain to A. what was happening to his dad using the plot of the Invasion of the Body Snatchers. He seemed to get it, and I’m sure he’ll look the film up. He’s interested in all sorts of pop culture lately, and he knows much more than I know. I hope it helps him to make sense of it all. Because I can’t really.

On the way to his guitar lesson in the East End, we passed the Royal, and again on the return home. It was dusk by then, and I showed him where his dad was, just a few metres away from us, in an ICU bed. I made up another story about our imaginary pets, the dog Brasidas and the cat Aristeides, who bear the names of the Spartan and Athenian rivals from one of the great wars in Antiquity and speak in human voices and are involved in all sorts of comical situations. I first began to make up those stories for him when we walked to his school in the morning, having tiptoed out of the flat like cat burglars to avoid waking up R. and setting off the madness. Then I would tell him another story at bedtime in his room, where we both slept with a chair jammed against the door to keep us safe during the night. Our imaginary pets kept us safe and sane throughout the terrible last two year of R.’s vertiginous descend into Hades. We laughed our way through that horror. In these stories, the world became a light-hearted, sunny, kindly place, where we could laugh and find relief from the netherworld into which R. was plunging and pulling us along.

Laughter saved us; we still laugh. To see the funny side of even the darkest situation is a gift. It’s one of the things they always said about A. at school: how much he enjoys jokes, puns, and banter; how they love to see his smile light up his face.

I hope we laugh for a very long time still; I hope we always find things to laugh about. I hope that the sense of fun and of the ridiculousness of most things, which softens the heart and makes forgiveness so much easier, never leaves us.

Dream Visions

Two days before he died, my father had a dream vision. He saw that an angel of the Lord came to him holding a scroll, like the ones holy figures are holding in Greek Orthodox icons. The angel showed him the scroll and tore it up and said: This is the contract of your debt. It is now forgiven. You are free.

My father took this to mean that he was absolved from his bondage to addiction. A smoker and drinker throughout his life from his early teens until nearly the end, even though he suffered from debilitating heart disease, he decided that he should die a free man. So he went into hospital – my mother and his doctors were begging him to do this for a long time but he had refused – because that was the only place where he would not be able to drink or smoke.

He was in for two days. The third day, he suffered cardiac arrest. When the doctors rushed in to resuscitate him, he made a signal to them not to. He said: ‘Can’t you see he’s already here? Saint George is here to escort me out.’ He was smiling and his face was bright and happy when he died.

‘Your father was – extraordinary,’ the doctor told my other sister, who wasn’t present at the moment of his departure, later. ‘I’ve never witnessed anything like that before.’

Dream visions and other visions that we would probably call hallucinations or vivid dreams now were nothing extraordinary for people who lived (or still live) in what we call the pre-modern era. Those visions were from heaven – or from hell. Patristic texts mention dream visions of temptation by demons. Contrary to the common prurient belief, those were not mainly sexual (even though the most famous are, which says more about the audience than the storytellers), but nightmares of sadness and despair. Most people who report dream visions in the country of my birth usually see angels, or saints, or the Virgin Mary. The faithful are protected in sleep. But for most of us, dreams are the rendezvous point where we meet the dead we loved and lost.

[Fragment 050919]

On this day, at ten minutes to seven, R. died, peacefully, free from bondage to alcohol, reconciled with the people who loved him best, clean and fresh and innocent like a baby. I was sitting next to him, holding his hand throughout, and his sister was sitting there too, and the hum of the cricket on the radio – he never missed it when alive – and it was sweet and bitter to see him go quietly, like a lamb, and all was forgiven.

No reproach or bitterness left.

Good night, R. Goodbye. I only weep because this is goodbye forever, because there is no place in this world where I can ever find you again.

Dust

(n.) The earth, ground in fine grains.

We all end up dead, dust upon dust; the earth is straining under the weight of so many dead people; the ground is made of bones ground in the great mill of time. No one remembers most of the people whose remaining particles make up the earth on which we step and which will eventually hide us. And if some are remembered, what does it matter to them now?

Eis Hadou Kathodos

(tr.) Descent into Hades, Journey into the Underworld.

Inanna. Orpheus, Herakles, Theseus. Odysseus. God, demigods, heroes made that journey to the place whence nobody returns. They all went willingly, albeit not happily, looking for someone, or something. A person, a dog, information. They all came back, some successful in their quest, some unsuccessful. Some barely escaped with the help of a divine adviser, others had to provide an exchange, someone who would be taken back there in their place.

In the Christian tradition, there is a time between Crucifixion and Resurrection when Christ is dead. But this death, exactly like all the dead in Greek folk tradition, is not nonexistence. It is a journey to the Underworld. Greek Orthodox iconography does not depict the Resurrection, as opposed to the Western tradition, in which Christ pops up from a tomb, like Jack-in-the-Box, amidst discarded tombstones and tumbled soldiers. Instead, the only icon that truly traditional Greek churches will display at Easter is known by the descriptive title Eis Hadou Kathodos (interpretatively translated into English as The Harrowing of Hell), in which the focus is on the epic journey and what happens there. Christ, dressed all in white inside a glory (= an almond-shaped pod) of star-studded, brilliant light, is descending into a dark, rocky, cavernous realm. On his right and left are groups of huddled people, crowned kings, bearded philosophers and prophets, common men and women, all looking scared and startled, as if awoken from a deep sleep to face a wondrous and terrifying sight. Christ extends his arms and grabs the hand of a very old man – Adam – to his right and a very old woman – Eve – to his left, pulling them upwards. The crowds are hanging on to Adam and Eve’s robes, and they are all pulled up towards the light. Beneath Christ’s feet are the broken gates of the Underworld, an assortment of keys and locks lying useless on the ground. A wild-haired, bearded man, Hades himself, is sitting nearby. His dejected posture, elbow on knee, hand cupping his chin, is the semiotic representation of suffering or distress in Byzantine iconography. That, and the mournful, resigned expression on his face signify acceptance of his defeat.

And yet, traditional laments from all over Greece, from The Iliad and The Odyssey to demotic songs, still speak of the place whence nobody returns, totally unconvinced about that victory.

Dont. Even. Ask. Too. Hot. is edited by Kirstin Innes, Chris Powici and Niall O’Gallagher, and published by Association of Scottish Literature, priced £9.95.