‘More than anything though, I wanted to foreground the lives of ordinary working people in what could be a harsh urban environment. Families living in Aberdeen tenements were crammed close together with minimal facilities – tensions could run high, even between those who were normally on friendly terms.’

Nina Allan has written a fantastic new novel, A Granite Silence, that explores a murder of a child in Aberdeen in 1934. It’s a hugely inventive novel that also explores how stories are made and how creativity happens. We spoke to Nina about her favourite books.

A Granite Silence

By Nina Allan

Published by riverrun

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

I can barely remember a time when I wasn’t reading. Very early memories include the Ladybird Books version of The Little Red Hen, which I actually found quite frightening but could not keep away from. Another early favourite was John Burningham’s Borka: The Adventures of a Goose with No Feathers, which I still find absolutely magical. I soon moved on to the Enid Blyton ‘Adventure’ series, and from there to everywhere else. By the time I was seven, I could not imagine being on a long car journey or anywhere, really, without a book to keep me company.

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest novel A Granite Silence. What did you want to explore in writing it?

A Granite Silence tells the story of a real crime that took place in Aberdeen in 1934. The case attracted an enormous amount of press attention at the time, but has fallen out of the conversation since, at least partly because of the massive social and societal changes brought about by World War Two. The coverage of the trial in the newspapers brought to light some of the ways in which women were set at a disadvantage in the all-male world of the justice system, and I wanted to shed some light on that. The case was also one of the very first to have hinged on the scientific analysis of forensic evidence. Scotland was in the forefront of the development of forensic science, a fact I thought it was both interesting and important to draw attention to. More than anything though, I wanted to foreground the lives of ordinary working people in what could be a harsh urban environment. Families living in Aberdeen tenements were crammed close together with minimal facilities – tensions could run high, even between those who were normally on friendly terms. I would like to think that readers of A Granite Silence will come to know the people involved in this case as if they were their own neighbours.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

Reading Sylvia Plath’s landmark poetry collection Ariel for the first time at the age of sixteen taught me everything I needed to know – both then and for the future – about the realisation of a personal vision through the medium of the written word. Plath’s immaculate synthesis of feeling, form and image can never be bettered in my eyes. My response to Plath’s work now remains as passionate as it was forty years ago, and reading her always leaves me both inspired and fortified. I would also add that anyone wanting to discover more about Plath’s life and work should seek out Heather Clark’s 2022 biography Red Comet. It is better than any of the others by some distance, centring Plath’s achievement as a poet and dialling down some of the rhetoric around her relationship with Ted Hughes.

The book as . . . an object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

This would have to be my Folio edition of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. As well as being one of the finest examples of true crime literature ever written, this particular edition contains some of the original photographic reportage of the crime at the centre of the story at the time it took place, images that formed part of Capote’s extensive files of research materials and that would have been there on his desk as he was writing. They are, still, immensely atmospheric. I like always to have this book in mind as an example of what can be accomplished in the field of the ‘factual novel’, as Capote himself referred to it, and this Folio edition is just such a joy to handle and read.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

My late husband and I talked about books non-stop, every day of our life together, but one particularly precious memory concerns the time soon after we met, when we were constantly comparing notes on the books that meant the most to us. I remember describing to him a novel I’d read when I was in my teens, a work of speculative fiction that imagined a world in which Queen Elizabeth 1 had been assassinated and Britain became a strictly Catholic country, with all development of the sciences firmly repressed. The book had made such a deep impression on me I could remember entire chapters virtually by heart – but I had no memory of the title or the name of the author. My husband was able to tell me even before I’d finished describing it that the novel in question was Pavane, by Keith Roberts, now seen as a classic of British speculative fiction. It turned out that he had read it on first publication in 1968 and it had always remained one of his favourite books!

The book as . . . rebellion. What is your favourite book that felt like it revealed a secret truth to you?

I first read Arthur Koestler’s 1940 novel Darkness at Noon in my late teens, and reread it several times over the following decade. The novel’s protagonist is Nikolai Rubashov, a committed communist in Stalin’s Russia who inevitably ends up falling foul of the secret police. The arguments rehearsed in the book – about art, about freedom, about whether the ends can ever justify the means – parallel Koestler’s own philosophical struggles and loss of faith in political ideology and had a profound and lasting effect on my own thinking.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

This might well be Michel Faber’s The Book of Strange New Things, which takes place on another planet! The main character, Peter, is being sent as a Christian missionary to the planet of Oasis, while his wife Bea is left behind to cope with life on Earth amidst the accelerating problems of climate change and deepening social inequality. At the time Faber was writing this novel, his wife Eva, an artist and photographer, was dying of cancer, and Peter’s experience of estrangement and grief strongly reflects Faber’s own, albeit within an entirely different context. In Peter’s interactions with Oasis and its people, Faber has succeeded in creating a genuine sense of alien-ness as well as a strange kind of beauty. This is a novel that repays multiple readings and that has a truly timeless feel.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

I am about to start reading Daniel Kehlmann’s brand new novel The Director, which tells the story of Georg Wilhelm Pabst, the great Austrian film director who flourished under the Weimar Republic but who was later forced into a deeply uncomfortable relationship with the Nazi Minister for Propaganda, Josef Goebbels. Kehlmann has often based his novels around historical events involving real characters, but he always approaches his material from an unexpected angle and produces work that hovers mysteriously between the real and the imagined. I’ll read anything he writes!

A Granite Silence by Nina Allan is published by riverrun, priced £20.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Walk Like a Girl by Claudia Esnouf

Walk Like a Girl by Claudia Esnouf

‘Suddenly there was a huge bang. The driver yelled. The car screeched to a stop. We all gasped, lurc …

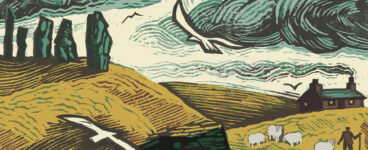

David Robinson Reviews: Storms Edge by Peter Marshall

David Robinson Reviews: Storms Edge by Peter Marshall

‘And the way Marshall writes history, putting the spotlight on Orkney and its people and showing how …