‘Like so many queer musicians, Somerville discovered a safe space in music – “I found a freedom on the dancefloor and also found a place to be on my own. I was in my own little world and I didn’t need to deal with anything else.”

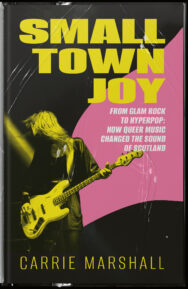

In Small Town Joy, trans writer, musician and broadcaster Carrie Marshall discovers the sometimes surprising ways LGBTQ+ artists changed Scotland’s soundtrack, meeting Scots artists, industry insiders and music fans to celebrate the music and musicians that filled floors, opened minds and changed lives. Here’s an extract that focuses on the brilliant Jimmy Sommerville and Disco.

Small Town Joy

By Carrie Marshall

Published by 404 Ink

‘Smalltown Boy’ may be one of the strangest singles ever to top the charts, peaking at number three in the UK and charting for twenty weeks in 1984. Where other artists took a kitchen-sink approach, throwing everything they could into their production, ‘Smalltown Boy’ is more minimal, centring those glacial synth notes and Jimmy Somerville’s beautiful, soaring countertenor, a voice that announces its presence with a note so high it could be a scream. ‘Smalltown Boy’ sounds like what it is: a song of sadness, of escape, of hoping for something better. Somerville’s backing vocals sound like ghosts.

Jimmy prefers not to do press interviews any more, but he’s talked about his love of music and of his songs many times. As he told The Quietus on the release of his disco album Homage in 2015, he spent his childhood in Glasgow’s Ruchill either watching Top of the Pops ‘religiously’ or being glued to the radio. Disco was huge at the time and he found himself drawn to it. ‘I think when I look back at all of those songs there would be a celebration and something positive in the sound,’ he says.

Although the teenage Somerville visited Glasgow’s gay clubs where disco was the soundtrack, he really made a profound connection with the music in his bedroom. Short, red-haired and looking ‘like a little girl’, as he described himself, Somerville was experiencing the ‘shame and guilt and real anxiety’ that so many LGBTQ+ people experience – but then ‘I would look in the mirror and pretend to sing like a Black man,’ he says. ‘It was my escape and my freedom.’

His primary gay club was Shuffles, in Glasgow city centre. ‘I first went on my own and I was completely shitting myself. I think I was so scared, I threw up on the bus on the way.’ But when he got to the club, Giorgio Moroder-flavoured magic was waiting. ‘The first thing I ever danced to in a grown-up club was fifteen minutes of Love Trilogy by Donna Summer,’ he says. ‘By the time it had finished I remember thinking: this is it. This is what it is all about and what I am all about.’

Like so many queer musicians, Somerville discovered a safe space in music – ‘I found a freedom on the dancefloor and also found a place to be on my own. I was in my own little world and I didn’t need to deal with anything else […] everything I have ever done has been to get to a club in order to dance.’

And he found something more. ‘Looking back at the history of the politics of disco, it was about gay men, Black men and also women having an uplifting celebration in the face of adversity and discrimination,’ he recalls. ‘While it’s easy to dismiss disco as a throwaway genre – stuff like The Bee Gees and Saturday Night Fever – it is actually about a whole movement of emancipated people seeking liberation.’

Disco happened a long time ago and it’s been endlessly parodied ever since, so what tends to stick in our mind is the worst of it from its final days, a time of novelty records, cynical cash-ins and even more cynical bandwagon jumping. Its modern-day incarnation as the sound of pink prosecco-fuelled hen nights and bad karaoke hasn’t helped either. But disco was much more than the two-dimensional caricature that persists in popular culture. Before it became commercialised and diluted, it was celebratory and defiant and dangerous – joy as an act of resistance.

It’s not a coincidence that disco started just after the bricks were thrown at Stonewall. That happened in the summer of 1969 after one heavy-handed police raid too many on the mafia-owned gay bar; one of the most influential disco clubs, The Loft, hosted its first party on Valentine’s Day 1970. The host was David Mancuso, whose house parties had already provided a safe space for his gay, Black and Latino friends to dance without fear of police harassment, and The Loft would continue that tradition. Regulars would soon be pivotal in creating hi-NRG and house music via their own nights, such as Larry Levan’s Paradise Garage and Frankie Knuckles’ warehouse parties in Chicago.

Denied safety and dignity by the outside world and by the US cops in particular, marginalised people found safe spaces to celebrate their lives, their love and their joy – and they did so at a time when the civil rights and gay rights movements in the US were moving away from a deferential, don’t-rock-the-boat kind of politics to something much more visible, vocal and vital. Disco was the soundtrack to a post-Stonewall world.

Inevitably, there was a backlash. Disco was too flamboyant, too decadent, too Black, too queer; Time magazine called it a ‘diabolical thump-and-shriek’. And perhaps the most visible example of the backlash was Disco Demolition, the ‘disco sucks’ event in the summer of 1979 that saw disco records smashed and scratched by a very white, very cis, very straight, and very male crowd in a Chicagoan baseball stadium. Instead of the expected crowd of 20,000, slightly more than the usual crowd for the White Sox, more than 50,000 people turned up and thousands more sneaked in after the gates had closed. The event ended in a white riot with an estimated five to seven thousand people invading the pitch, causing so much damage that the White Sox couldn’t play.

The parallels between the ‘disco sucks’ crowd and today’s self-proclaimed anti-‘woke’ warriors aren’t hard to draw, and while those involved in the event have long denied racism or homophobia, it’s hard to be charitable about a movement primarily made of straight, white young men who described disco as a ‘musical disease’ destroying art primarily made and enjoyed by Black and Latino people, gay people and by women. Attendees noted that the records some of those young men brought to smash weren’t even disco records, but albums in other genres by Black artists such as Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder and Curtis Mayfield. As White Sox pitcher Rich Wortham put it, ‘This wouldn’t have happened if they had country and western night.’ At the end of 1979, Dave Marsh wrote in Rolling Stone, ‘White males, eighteen to thirty-four, are the most likely to see disco as the product of homosexuals, blacks and latins, and therefore they’re most likely to respond to appeals to wipe out such threats to their security. It goes almost without saying that such appeals are racist and sexist.’

Between ‘disco sucks’, novelty records such as Rick Dees’ quack-packed ‘Disco Duck’ – voted the worst song of the 1970s by Rolling Stone readers – and the inevitable commercialisation and dilution that ruins any successful musical movement, disco’s imperial phase was over. But while the reactionaries may have won the battle, they lost the war. Forced back underground, disco would be instrumental in the birth of house music, the New York clubs that would so inspire Madonna and a generation of pop idols, and the clubs in Europe that would create Eurodance. What had become tired and formulaic in the charts would return triumphant in a galaxy of new genres.

Small Town Joy by Carrie Marshall is published by 404 Ink, priced £11.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Walk Like a Girl by Claudia Esnouf

Walk Like a Girl by Claudia Esnouf

‘Suddenly there was a huge bang. The driver yelled. The car screeched to a stop. We all gasped, lurc …

The Malt Whisky Murders by Natalie Jayne Clark

The Malt Whisky Murders by Natalie Jayne Clark

‘It had been up to me, alone, to cram these bodies back into their cask coffins, replace the fetid l …