‘No one had challenged the banns because she knew no one here, was nothing here. She was completely and wholly alone.’

The Needfire tells the story of Norah Mackenzie, fleeing from a past in Glasgow she wants to forget straight into a marriage of convenience to a Highland aristocrat. In this extract her regrets appear soon after the marriage ceremony.

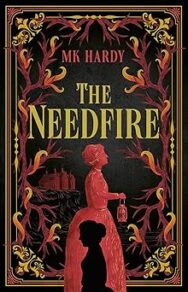

The Needfire

By M. K. Hardy

Published by Solaris

The kirk was nowhere and then suddenly right before them, the mist parting to admit them into its waiting open doors. They had only walked back down the driveway and partway along a side path, though with the thick mist and the light fading fast it felt as though they had left the house far behind nonetheless. The building was broad and squat and harled just like the house, and it occurred to Norah that they had probably been built at the same time. It was built for practicality rather than beauty, a far cry from the delicate spire and stained glass of St John’s back home. Still, the unadorned windows glowed from the light within, and at the sight of it some warmth returned to Norah’s belly. She had chosen this. As strange as it was, this was her will.

They stepped from the falling blanket of night into the church, lit with candles and sturdy lamps along its nave. The interior was dressed sandstone, muting the glow of the flames and capturing what little warmth they radiated. Standing at the altar was a man so like the housekeeper that had greeted her that she had to glance between them just to believe her eyes. He had the same dark eyes set in a face of sharp angles and planes, the same broad shoulders and straight-backed bearing. And he looked at her in the same peculiar way, as if suspicious of her sudden arrival despite the fact that it was he himself who had asked her here—he who had arranged for them to meet like this, in a church, first setting eyes on one another minutes before exchanging eternal vows.

The minister was a slight and unassuming sort of character with steely hair and a narrow, pinched face, fully a head shorter than her fiancé. He was drowning in his vestments, which were a spartan affair and clearly made for a much larger frame. He was the first to break the silence by clearing his throat. The sound echoed around the chamber, impossibly loud.

‘Gunn.’ Norah fancied the minister did not like the taste of that word in his mouth and her mind began to spin stories as to why. ‘And you must be Miss Mackenzie. It’s good to meet you at last.’ He did not speak like Gunn or the man with the cart. His speech was clipped and monotone, though still a little unfamiliar to Norah’s ear. An east coast lowlander.

‘Good evening, Reverend. I must thank you for coming all the way out here to perform the service—I hope to be able to visit your church one day soon, and meet the families who attend.’ She couldn’t shake the feeling that she was being hidden away; why else have the service here instead of in the village? Was he ashamed of her?

‘Indeed,’ replied the minister with a smile, though it was close-lipped and didn’t reach his pale eyes. ‘I was sorry to hear that his lordship’s health would prevent him from attending, as indeed it has these past few years.’ The tone was significant, and Norah turned to scrutinise the man by her side all the closer, but then Gunn spoke up.

‘Ah, there you are, Jamie.’ Nobody else had noticed the light-haired man letting himself in. He was wearing a flatcap now, and a threadbare jacket instead of his earlier coat. ‘Miss Mackenzie, I believe you met earlier: Jamie MacCulloch is our groundskeeper.’ The man tipped his head in greeting again, but didn’t move from his post by the door. Gunn turned her gaze back to the minister and lifted her dark eyebrows. ‘Are we ready, then?’

‘Please.’ It was the first word her fiancé had spoken, and it nearly made her jump out of her skin. His voice was deep and yet thin, scratchy, as though he used it little. ‘Begin.’

What followed was a perfunctory ceremony made all the stranger by the dead silence around them.

There were few bodies in the church to muffle the sound, and so the minister’s voice reached every corner where it hung, expectant and ringing with judgement. Norah fixed her gaze on his face, suddenly unable to look at the man beside her as their fates were woven together by fiat of God and His representative here on earth.

What had she expected? That she might set eyes on her fiancé and find the pit in her stomach miraculously vanished? That he might be a guiding light in these damp and dreary environs? She had never thought as much consciously, but it seemed she must have hoped it, for as the minister pressed onward and she mechanically followed his instructions to turn and face her groom, she was gripped with a sudden and all-consuming terror. She had made a dreadful mistake.

It was not sentimentality that made her quail; she had never dreamed of her wedding as some little girls did, so a perfunctory ceremony in her travelling clothes was as favourable as a cathedral filled with well-wishers—perhaps more so, given the expectations that would place upon her. No, her dread stemmed from a far more mundane source: the dawning realisation that she was surrounded by strangers, for despite the dozens of letters they had exchanged, Lord Alexander Barland regarded her with nothing but mild chagrin as they recited their vows. No one had challenged the banns because she knew no one here, was nothing here. She was completely and wholly alone.

The staff were their witnesses (Norah chided herself inwardly for her mild surprise that McCulloch signed his name and not an ‘X’). The minister presided over the whole affair with that same pinched-face expression, clearly under sufferance, though whether due to the obviously unromantic technicalities of this union or being dragged away from his manse on a Saturday evening was hard to say. Comfort, when it came, was from an unexpected source: as Norah looked up from signing her own name, her eyes met those of the housekeeper, standing in front of the pews, still in her coat. Gunn favoured her with a grim, tight-lipped smile, and for just a flicker of a second, Norah perceived something real behind her unmoving gaze. Not sympathy, exactly, but not its sanctimonious cousin pity either. She glanced from Gunn to her new husband, two straight-backed peas in a pod, and her heart sank again. There was no such secret warmth in his eyes.

It was properly dark when they emerged from the church into frigid air. The clouds were too heavy for stars and even the waxing full moon was a hazy smudge. The land sloped steeply off to the north and Norah knew the sea was spread out forever beyond, but it was gone now, nothing but the path before them visible in the fog.

‘Stay close.’ It was Gunn and not the baron who’d fallen into step at her elbow, and she was perversely relieved. She had to keep from moving closer still, her body hewing to Gunn’s out of cold and not a little apprehension.

‘Is this normal? That the fog should be so low and dense?’

‘Sometimes.’ A pause. ‘Often, in the mornings and at night. In the summer it usually burns off during the day.’

‘I’m beginning to think arriving in the summer would have been a far wiser choice,’ Norah said with a rueful shake of her head. ‘The dark is…’

‘You don’t have the dark in Glasgow?’ The tone was even, flat, and yet Norah thought she could hear the tease in it.

She ducked her head, holding back a smile of gratitude at this small gesture. ‘Not like this. At ho—in Glasgow the dark is always softened by the streetlights, the lamps shining out of people’s windows. It never feels truly dark, even in the dead of winter.’

‘Well, it will never feel truly dark by the middle of summer here, so you have that to look forward to.’

Norah hadn’t thought about this; hadn’t thought about many things to do with her new life, it seemed. She considered it now, the fact that they found themselves so far north that in winter, the sun barely deigned to come near at all, its absence casting the world into perpetual dimness. How did the plants and animals grow in these conditions? How did the people?

At length, Gunn cleared her throat. ‘You did not bring a lady’s maid,’ she said. ‘Are you accustomed… will you be requiring my services?’

‘Oh.’ She hadn’t seen any other servants in the house, it was true, but then, she’d barely spent ten minutes inside before being whisked off to the church. She’d assumed—hoped—that there’d be a lady’s maid already in position, since her mother had steadfastly refused to let her away with the one they had ‘shared’ for the past year or so. In truth her mother had kept the poor girl so busy that Norah had taken to seeing to her own needs rather than require the girl to work twice as much for paltry pay. She’d gotten proficient enough at most tasks that she wouldn’t feel the lack of a maid now, even if it was unexpected. ‘I’ll manage just fine, thank you. I’m sure you have enough to be getting on with, anyhow.’

‘There’s plenty to do, right enough. Careful—’ The last utterance was accompanied by a firm hand on Norah’s elbow as her footing betrayed her on the steep root-laced path. For a moment everything seemed to tilt, and vaguely Norah pondered that if the light could forsake them this far north, why not gravity as well? But then her boot settled more firmly on the ground and Gunn pulled back her hand, and the world righted itself once more. The housekeeper’s next breath came out with a whoosh.

‘There’s a steep drop to your right,’ she said. ‘Mind yourself.’

Somehow Norah knew better than to look down. Sometimes one didn’t have to see the fall to know it was real. They arrived back at the house a few minutes later, the stillness broken only by Gunn’s key scraping in the lock. Norah heard a crunch of gravel behind her and had to fight the urge to spin round, her nerves taut as an overtuned fiddle. A moment later her husband moved past her through the doorway, a dark figure swallowed by the dark house. A hand on her arm again.

‘I’ll show you to your rooms. You can rest before dinner.’

The Needfire by M. K. Hardy is published by Solaris, priced £18.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Centenaries, Controversies and the Scottish Sixties

Centenaries, Controversies and the Scottish Sixties

‘Of course, our authors do not fit neatly into this binary model of cosmopolitan radicalism and humd …

Who Will Be Remembered Here? Queer Spaces in Scotland

Who Will Be Remembered Here? Queer Spaces in Scotland

‘She would see wives – like me and Eilidh! – walking hand in hand, legally married, kissing in broad …