David Robinson Reviews

‘And although F Scott FitzGerald’s aphorism ‘character is plot, plot is character’ is drilled into anyone learning about crime fiction, if I was forced to pick between the two, I’d pick character every time. Wouldn’t you?’

David Robinson shows his appreciation for original and compelling characterisation in crime fiction.

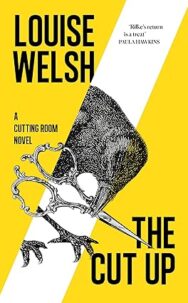

The Cut Up

By Louise Welsh

Published by Canongate

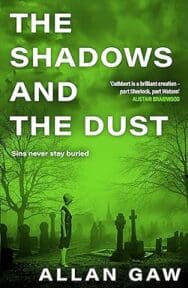

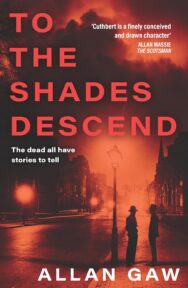

To The Shades Descend and The Shadows and the Dust

By Allan Gaw

Published by Polygon

Sometimes, if they’re in a particularly diffident mood, you’ll hear crime writers say that theirs are the easiest novels of all to write. At the very least, they’ll say that about the opening chapters. Most, after all, start off with a body being found, then a detective has to be summoned, then the pathologist has to explain how death happened, then there’ll be a few suspects and hey, before you know it, you’re halfway through your first draft.

Yet if you actually study crime fiction, you’ll get a rather different story. If, for example, you are lucky enough to be taught by Louise Welsh on the MLitt course in creative writing at Glasgow University, she’ll teach you that crime fiction is never just about the crime. Other things – character, place, originality – matter at least as much, if not more. And as she shows in her latest novel, she practises what she preaches.

True enough, The Cut Up begins with the discovery of a dead body. But after that, just count the original ways in which Welsh subverts the genre. This all starts with the man who discovers the body. Tell me, for example, how many gay Glaswegian auctioneers you have already come across as lead characters in crime fiction. No? Me neither. Welsh’s Rilke is such a one-off that he can even get by without needing a first name.

Then there’s the mode of death. In The Cut Up, this is by means of a hatpin through the eyeball. Trawling through every novel known to Chat GPT, this seems to be quite original, although it does have a category for ‘Eye-Stabbing Deaths (Non-Hatpin)’. Welsh sharpens her plot even further by making the murder weapon the very hatpin which Rilke’s boss (and friend) has just been waving in front of the cameras of a daytime TV show, adding helpfully that medieval knights used to use stilettos like that to stab enemies through the eye once they’d been knocked off their horses.

The biggest act of subversive originality is, though, still to come. Not only does Rilke deliberately wreck the crime scene by retrieving the hatpin but he then puts it in the next auction. Someone buys it and … well, we’re off. The reader is hooked. Even if you hadn’t already encountered the wildly charismatic Rilke in Welsh’s debut novel The Cutting Room (2002) or The Second Cut (2022), you would surely be drawn in by such a bravura beginning.

But although Rilke subverts all the usual methods of serving justice, he serves justice all the same. The police – corrupt and so incompetent they don’t spot the murder weapon even when it is under their noses – can’t be relied upon. And though the story I’ve outlined so far only takes us to Page 39 and contains no spoilers, Rilke is so convincingly Sherlockian in thought and deed, and so arrestingly stylish (brogues and demob suits) that we somehow know that he’ll end up finding the murderer.

Already, then, Welsh has moved the story a long way from the plodding procedural opening I outlined at the start. It’s on a different track altogether. The crime itself is, shall we say, interesting, but Welsh wants more than that. She always has. I remember a scene in The Second Cut in which Rilke is driving his close friend Les, a transvestite ‘who looked like Nureyev might have, if he had survived HIV and given in to the occasional fish supper’ in the passenger seat and three queer acquaintances in the back, two of whom had just been to a pro-trans demo in George Square. The scene itself was well-written, but two things about it made it stick in my mind. First of all, I realised I had probably never read about a car full of five queer Glaswegians. Secondly, I wondered why I never had.

So when Welsh tells her MLitt students that crime fiction isn’t just about the crime, this is the sort of thing she has in mind. Without either frightening the horses or writing a gender politics tract, The Second Cut showed how Glasgow’s gay life had changed in the two decades since she began writing The Cutting Room in 2000. Back then, the campaign to repeal Clause 28 (forbidding local authorities from ‘intentionally promoting homosexuality’) was in full swing; in 2022, she began its sequel with a gay wedding and continued with Rilke taking full advantage of Grindr.

In The Cut Up, there’s a hint that Rilke still is on Grindr and there’s a fling with a trans man. Yet far more important (at least to the plot) than Rilke’s sexuality is his character. His loyalty to his friend Rose is the reason he retrieved the hatpin in the first place. For the sake of that friendship – even though she is going out with a police inspector – he risks everything. He may be unconventional, but in all other respects he fulfils Raymond’s Chandler’s requirements for an ideal protagonist to the letter as someone who is solitary, uncorrupted, and courageous, ‘who walks down mean streets but is not himself mean’.

Another queer crime-busting protagonist comes to Glasgow in Allan Gaw’s To The Shades Descend, which is just published by Polygon. Gaw, 63, winner of Bloody Scotland’s Crime Debut of the Year award in 2024, came to crime writing after a distinguished career as a pathologist. As the fourth in his Dr Jack Cuthbert series (The Shadows and the Dust) is out this month and the fifth due out later this year, his second career is clearly off to a flyer.

Now you may well think, particularly if you’ve read a lot of Patricia Cornwell, that a former pathologist like Gaw, who has run big research clinics and has amassed an intimidating amount of experience in his field, would want to go down the corpse-DNA-result crime-busting plot path. But no. When I talked to him recently, he gave me a number of reasons why he deliberately set his Jack Cuthbert novels in the 1920s and 1930s.

‘We are now in a position,’ he said, ‘where we can analyse and quantify any chemical in the world. Anything you’ve been poisoned with, for example, I can find – I don’t even have to think about it. In some ways, it’s a little bit too easy. I wanted to show pathology in a world where you had to work much harder to get this information, to make it much more observational, because all through history, medicine has always been about observation. We talk about physicians attending their patients – they sit beside them and watch them, and that’s the way doctors used to work, because it was all they had.’ With the discovery of DNA, much of that attentiveness – ‘which is fundamentally about trying to form a connection with another human being’ – has been lost.

Gaw then said two things I’ve never heard from any crime writer, least of all one with a new book to plug: first, that he himself hardly reads any crime fiction, and secondly, that ‘there are probably quite a lot of people who do who won’t like my books. They’ll think there’s just too much dithering about for them.’

By ‘dithering about’ Gaw means back story. But creating a complete character – from flashbacks to Jack Cuthbert’s schooldays and his early crushes on his fellow pupils, to facing the horrors of the Somme – was what drew him to writing in the first place. That, and showing the past as realistically as he could – not just of Glasgow in the 1930s, but also the embryonic form the science he has studied all his life was back then – alongside the attentiveness Gaw mentions to help solve crimes.

‘I wanted to write book about a character: an interesting, complicated, layered character, where you weren’t going to know everything about them at first, but rather like peeling back the layers of an onion, you’d learn more and more about them and become more invested in them.’

Having read my way into his series so far, I think he’s onto something, and not least because this clearly holds true for Welsh’s Rilke too. However, even though I have rhapsodised about the brilliance of The Cut Up’s opening, it is really the strength of Welsh’s characterisation that keeps my attention to the end. And although F Scott FitzGerald’s aphorism ‘character is plot, plot is character’ is drilled into anyone learning about crime fiction, if I was forced to pick between the two, I’d pick character every time. Wouldn’t you?

The Cut Up by Louise Welsh is published by Canongate, priced £16.99.

To The Shades Descend and The Shadows and the Dust by Allan Gaw are both published by Polygon, priced £9.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Saltswept: A Q & A with Katalina Watt

Saltswept: A Q & A with Katalina Watt

‘I’ve always been obsessed with folkore around the sea and I think coming from two island nations – …

The Cut Up & The Shadows and the Dust

The Cut Up & The Shadows and the Dust

‘And although F Scott FitzGerald’s aphorism ‘character is plot, plot is character’ is drilled into a …