‘It cried again, loud enough to shake the ferns at Kensa’s waist and call her towards it, towards Elowen, towards nothing she had ever seen before.’

The Salt Bind is a gothic, fantastical fairy tale that pays tribute to all those women named as witches in the 18th century. In it, Kensa is a daughter of a feared pirate, but she is determined to make her own mark in the world, training in the secrets of The Old Ways. This extract relays the appearance of an unwanted omen.

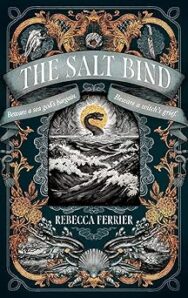

The Salt Bind

By Rebecca Ferrier

Published by Renegade Books

Ever since she could remember, Kensa had been unwelcome. That’s what came with being the daughter of Alexander Rowe. Rumour was, after he was hanged and strung up over Percuil River, his body refused to rot. Others say his body disappeared altogether, swallowed by the tides for an unpaid debt. Kensa thought she remembered that day, too – the hanging – and if she didn’t, she’d been told of it so often that a memory had formed nonetheless.

And she’d been told what she’d done.

‘That chit crawled on to the scaffold and put her hands in his pockets,’ said Old Sal. ‘Thieved from her own father afore he was cold.’

It was true, but Kensa had not taken money. Instead, she had removed a hagstone from her father’s coat. It was as large as her palm with a hole knuckled through it. She could not forget the first time she’d seen it. Her father had come home from sea, rattling with gifts and thick with beard. He’d chased her round their small cob- walled dwelling and placed that hagstone to her eye.

‘Here’s how I know when a storm’s coming,’ her father told her. ‘Here’s how I know to go wrecking.’

Although the hagstone had not protected him from the law and the noose, it was a comfort to Kensa. A weight as natural as her own flesh, carried from one scorn to the next. Her fingers strayed to it now in the salting house, nerves hidden behind that flat, hard mouth.

In the corner, quiet as always, Elowen played with another child. How easily she made friends. Charming everyone with her cow- long lashes and dainty steps. Ones that would always follow Kensa, asking her to slow down, to wait, to stop. And her name a question, always a question, asked over and over: Kensa? Kensa? Kensa?

She turned away, stretching to glare inside a half- filled barrel. A dozen pilchard eyes stared back. Her chest grew tight. It always did when she thought on her father. Distracted as she was, she did not see Elowen approach. ‘Kensa?’ A sudden pull on her sleeve startled her, her fingers slackened, the hagstone tumbled into the dark and bounced beneath Old Sal. And when the heavy- set woman fell, it was with a hard thump. One which brought a pilchard barrel with it, clattering into two others and sending the carefully packed fish and salt across the bloody floor. Four hours’ work gone, a hard night ahead, a wage that had to be earned.

Kensa scrabbled for her hagstone and found Old Sal’s face pressed into hers.

‘I didn’t mean to—’

Her excuses fell unheard, replaced by threats to box ears and tan hides. ‘You’re as twisted as your father was,’ said Old Sal. ‘He brought badness with him and now you’ll do the same. Out, go on! Take the little one with you! I want you gone.’

Kensa’s neck burned. Eyes – woman and child and pilchard – turned to her. She opened her mouth to protest and closed it, firmly, teeth clacking together. Head down, she wrenched herself from the salting house, dragging Elowen behind her.

Anger kept Kensa walking. Portscatho’s natural incline, a deep slope to the ocean, propelled her towards the harbour. A full moon lit the cobbles, turning what would be red in daylight into a long black stream. By the sea wall, the men had finished unloading the boats and sat together with lit pipes and empty tankards. Only when she felt a tug on her arm did she slow, remembering the shorter legs which struggled to match hers.

‘Kensa?’

‘No,’ she spat, furious.

One word and all the shame inside her reached out to echo against the receding tide.

Elowen gasped, a small huff into Kensa’s face, only a hair’s breadth away. The men on the wall quietened, their low murmurs fading as they listened. Next came a chance, a beat where Kensa could have sunk down, grasped her sister’s arms and apologised. After all, it was not truly Elowen’s fault, it was a mistake. Yet she did not, could not admit it. The younger child, eyes spilling over with tears, wrenched herself away and ran. Her buckled shoes slapped shingle and her fair hair trailed behind her. She left Kensa standing there, with curdled seafoam and fish blood stiff and drying on her skirts.

It served her right. Kensa repeated this to herself as she paced. Near by, the drunken men at the harbour were laughing at lewd jokes, though the few words she overheard made little sense to her. Of course, it was always Kensa in the wrong, never her sister.

‘Elowen?’

Where had she gone? Now it was Kensa’s turn to ask, call, wait.

Her voice bounced off cob wall and quarried stone. There was no answer. She cuffed her nose with her sleeve and walked. Uphill was home, a small dwelling elbowed into a long terrace which lined the main road through Portscatho. Elowen had gone the other way, along the path which bordered the coast and dipped precariously close to the sea. Kensa went after her. As she began to move, her anger was replaced with worry, then guilt. She called out again and again. No reply. How far could Elowen’s legs have taken her? Kensa pushed on, faster, her path a gloom of ferns and tree roots. She knew the stories, had been raised on them, about the beasts who would snatch a child from its cradle or a maid from her virtue, should the Father of Storms – the Bucka – wish it. Kensa did not like to think on him too close to the sea, lest her thoughts summon him, impossible though it seemed. To her left, the ocean sighed and over the waves came a sound.

It was a low, keening cry. A wail like wind across a rum bottle, clear and high and sweet to hear. Loud, terribly loud: inhuman and unanimal. It tightened a knot in Kensa’s chest. Her feet pummelled the earth as she sprinted towards it, that sound, and the creature who made it.

Elowen had got there first.

From a high point on the path, Kensa saw her sister standing on the Towan’s shore, dwarfed beside a ship- sized mass. She was a thin stripe against a hulking body. Could it be a whale? It cried again, loud enough to shake the ferns at Kensa’s waist and call her towards it, towards Elowen, towards nothing she had ever seen before.

This was no whale. This was a sea monster.

The Salt Bind by Rebecca Ferrier is published by Renegade Books, priced £18.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

A Bad, Bad Place by Frances Crawford

A Bad, Bad Place by Frances Crawford

‘Teenage protagonists have a special place in fiction, offering a view from the no-man’s land betwee …

A Death in Glasgow by Eva MacRae

A Death in Glasgow by Eva MacRae

‘The hand keeps coming. But when it reaches the front of her coat, it’s not a grab. It’s a push.’