Ahead of publication of her compelling new novel The Uncommon Life of Alfred Warner in Six Days, Books from Scotland talks to Berlin-based author Juliet Conlin about her love of history, voice-hearing, confronting difficult personal truths, her writing process, and much more.

Introduce us to your new novel The Uncommon Life of Alfred Warner in Six Days…

Alfred Warner knows he only has six days to live. A frail 80-year-old man, he has made the journey from England to Berlin to reveal a secret to his granddaughter, Brynja, which has haunted him his entire life. But when Brynja fails to meet him, Alfred’s only hope is to pass on his family secret to a stranger who takes him in. He tells her how he was tragically orphaned and of his terrifying ordeal at the hands of the Nazis — how he was conscripted into the German army and how he was imprisoned in a POW camp. And he reveals how he built a new life in Britain. Alfred’s story is remarkable. But its telling will reveal the secret which will save his granddaughter’s life…

The central protagonist Alfred hears voices. How did the character of Alfred, and his voice-hearing, come to you?

I’ve had an interest in the experience of voice-hearing for a long time. Several years ago, I was juggling three – to me separate – ideas: a short story (in German) about a German prisoner of war who decides to stay in Britain after WW2, a stream-of-consciousness narrative about a young woman suffering from mental illness, and a story based on Nordic mythology. Through some fluid, obscure, unspecifiable creative-mental process, the three somehow came together one day – and Alfred, Brynja and the Voice Women were born!

You have a keen interest in, and appreciation of, history which both of your novels – The Uncommon Life of Alfred Warner in Six Days and your debut The Fractured Man – show. What in particular made you choose the wartime period, and the rise of Nazism, as the backdrop to The Uncommon Life of Alfred Warner in Six Days?

A few hundred metres from where I live in Berlin, there are three small brass plaques set in among the cobblestones on the pavement. From a distance, they are hardly noticeable, but up close, you can see that each carries an inscription: a name, date of birth, date of arrest and date of murder. These are small, poignant and very personal memorials to Jewish men, women and children who were deported to concentration camps and murdered by the Nazis. They are called “Stolpersteine” – Stumbling Stones. To date, there are over 7,000 such stones in Berlin, and many thousands more across Europe. In The Uncommon Life of Alfred Warner in Six Days, the protagonist spends several years of his childhood during the 1930s at the Jewish orphanage in Berlin.

My decision to locate these years of Alfred’s life here was influenced by my own background. I was born to a German mother and a Welsh/Irish father. My maternal grandfather was, by all accounts (although no-one really likes to talk about it), a Nazi sympathiser. He was killed in action in 1945. Like every other German, I have been confronted with this aspect of my collective, genetic history, and I have found it by turns frustrating, enraging, difficult and occasionally shameful. So much has been written on this aspect of history, in fiction and non-fiction, so many angles have been examined, so many stories told. But one of the conclusions I have drawn from tackling my own German-ness is that this period must never be forgotten, and that for every story told, there is at least one story as yet untold.

Photo Credit: Annette Koroll

You live in Berlin which centrally features in the narrative as Alfred and Julia’s meeting place, and you also set the book’s action elsewhere including Scotland. How important is creating a sense of place to you as an author, and how did you research the different places for the novel’s settings?

Creating a sense of place is just as important as creating authentic, fully-developed characters. The Berlin setting was straightforward, as I live here. When I was choosing a location for Alfred’s time at a PoW camp, I decided to research PoW camps in Scotland (not least as an excuse for another visit!), and was surprised to discover that of the 600 camps in the UK during and after WW2, at least 25 of them had been in Scotland. I finally whittled my choice down to Kingencleugh Camp near the village of Mauchline in Ayrshire, as the location slotted nicely into my story. Kingencleugh Camp, Camp 112, had housed 500 German soldiers, who were put to work on the surrounding farms before most of them were repatriated to Germany after the war.

I then visited Mauchline to do some research and get a feel for the place, and was delighted by the openness and friendliness of the local residents, and their willingness to stop and have a chat over the garden fence. A few of the more elderly residents could even remember the camp (which is now completely gone, only a rusty Nissen hut remains on a farmer’s field). One old man, listening with interest to my description of the novel I planned to write, gave me a questioning look and said:

“Are ye talking about Joe?”

“Who’s Joe?” I asked.

“Johann,” he replied. “He was a prisoner of war in Kingencleugh, but he fell in love with a local lass and decided to stay.”

“And does he still live here?” I said (my heart beating wildly at having perhaps discovered a true-life Alfred).

“Aye, he does,” the man replied. “But he’s away in Spain with the wife.”

So, sadly, I didn’t have the opportunity to interview Johann, but was delighted at the discovery that life and art are so closely intertwined!

The Uncommon Life of Alfred Warner in Six Days is ambitious in scope in that it tells a whole life – and an extraordinary one at that – within its pages. Did you encounter any challenges when deciding how much of Alfred’s life to narrate and how much detail to give to the reader?

This was a huge challenge! In fact, the first draft of the novel was close to 600 pages and needed several re-writes to whittle it down to the 448 pages it has now. I had to decide on which aspects of Alfred’s life to focus in detail on and which to skim over. So, for example, his final twenty or so years are told in only a couple of paragraphs, but this reflects my own experience: the older you get, the more rapidly life goes by (at a frightening speed!).

Does having studied Psychology to doctoral level influence your writing? If so, how?

Much like writing a novel, the research and writing involved in a PhD are immense. Completing my doctorate gave me a huge sense of confidence and achievement, which I still draw on today when I feel myself falter. Also, the study of Psychology has provided me with a treasure trove of inspiration – I was very lucky to have access to the Centre for the History of Psychology at Staffordshire University when I was doing my MSc – I’m full of ideas! Now I just need the time…

Tell us a bit about your writing process. Do you have a favourite place to write? And do you follow a particular routine?

I approach writing very much like any other job, that is, I go and sit at my desk every morning at around 8 am. Mornings are my most fruitful time for creative writing, so I write as much as I can for a few hours, and save other stuff (e-mails, paperwork etc.) for the afternoons. I write a lot in longhand and need peace and quiet to write. Over the years, I’ve discovered that self-discipline and good time management are just as essential as an inspirational idea.

What advice would you give to aspiring novelists?

The obvious advice: read as much and as widely as you can. Write a lot. But also: get out of your comfort zone – if you normally listen to classical music, try hip-hop; if you are a night-owl, get up very early on occasion and take a ride on public transport at 6 am; if you like watching TV series, go and visit an experimental art installation; if you like hot climates, spend a long weekend in Iceland. It is amazing how your creative brain will respond to different, uncomfortable experiences!

When you’re not writing, what would we find you doing?

I also work as a freelance translator, which slots in well with my creative writing. Working with two languages keeps my brain plastic. I go for a short run every day to keep my joints from rusting. I also have four children who inspire and delight me, and who – importantly – have learned to respect the “Do Not Disturb” sign on my study door!

Do you have a favourite Scottish book or Scottish author that you particularly enjoy?

This might be a tough question, because there is so much fresh as well as established Scottish talent out there – A.L. Kennedy, Kirsty Logan, Louise Welsh, Jenni Fagan, Helen Sedgwick, Sara Sheridan, Graeme Macrae Burnet, John Burnside, to name but a few. But there is one Scottish writer who, for me, is nothing short of genius: Ali Smith. Smith elevates storytelling to its highest art form, and her writing leaves me feeling inspired and in awe in equal measure.

And finally, what’s next for you?

I’ve just finished the first draft of my next novel, Exile Shanghai, which is set in a Jewish ghetto in 1940’s China. This is an absolutely fascinating slice of history – Shanghai was a haven for tens of thousands of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany, who ultimately ended up in a ghetto on the other side of the world – and is at the same time disturbingly topical.

The Uncommon Life of Alfred Warner in Six Days by Juliet Conlin is published by Black & White Publishing on 23rd February priced £8.99. Juliet launches the book at The Edinburgh Bookshop on Thursday 23rd February.

This extract presents the account of the younger sister of the ill-fated Tsar Nicholas II. Her privileged life suddenly changed in 1917, at which time she was working as a nurse, tending casualties of World War I. The February Revolution seemed to come out of nowhere and, as she relates here, she and her family were forced to flee to Crimea. But even there they were not safe…

Extract from 25 Chapters of My Life: The Memoirs of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, Last Grand Duchess of Russia

By Paul Kulikovsky, Karen Roth-Nicholls and Sue Woolmans

Published by Strident Publishing

8th March 2017 marks the centenary of the start of the Russian Revolution, which saw the end of the Tsarist regime of Nicholas II and the introduction of Communism. The Russian Revolution was really a pair of revolutions – the February and October revolutions. So why the 8th March centenary when it’s called the February Revolution? Simple: in 1917 Russia worked to the Julian calendar, which is 12 days behind the Gregorian calendar that we (and Russia) now use.

The Flight to the Crimea

The news that a revolution had broken out in St. Petersburg came to those of us who worked in our hospital in Kiev like a veritable thunder bolt. We hadn’t heard a word – not even a rumour, but one morning it was all over the newspapers. We read the news over and over again and did not want to believe our eyes. Our patients were just as surprised and terrified as we were ourselves. They stared at us with bewildered eyes, and couldn’t stop asking what would become of them and the rest of us. We hadn’t a notion and barely knew what had happened. None of us could foresee how much it would disrupt all our lives.

My Mother immediately set off by train to the headquarters at Moghilev to see and speak with her eldest son, the Emperor. It was a trying journey for her…and it would have been many times more trying if she had known that it would be the last time she would be seeing Nicky. [Tsar Nicholas II.]

While Mother was away, the general mood in Kiev slowly changed. It was evident that the revolution was on the way. We discussed the situation and realised that we had to change our whereabouts. As soon as Mother returned to Kiev my brother-in-law, Xenia’s husband, suggested that we take her as far away as possible from the danger spot. We should take her to the Crimea where he owned an estate named Ai-Todor. It was situated on the Black Sea and here he believed that we would be in safety. He had already given his wife and children instructions to leave St. Petersburg and travel to the Crimea to join us there as quickly as they possibly could.

The next problem turned out to be how to get down there. The ordinary train connections were highly unreliable, but then with great efforts and through private connections my brother-in-law succeeded in procuring a special train which was made ready for immediate departure. My husband and I decided to accompany Mother and the others to the Crimea, but we intended to return immediately to our duties as soon as the whole family had been installed in their temporary home.

And then off we went. We set out late one night, but it was not from the station where it would have caused a commotion and where hundreds of helpless people were waiting for an opportunity to get away, but from a small wood a short distance from Kiev. We drove out there in the dark, found the train at the appointed spot, got in and away it immediately puffed. We were on our way for two days and stopped at a number of major stations. There our escort of a few soldiers stood at all the doors to prevent the wagons from being taken by storm by the crowds of demoralized people, who had decided to fish in troubled waters and who were waiting for an opportunity to get somewhere else where there was something going on. Thankfully, the journey went as planned, despite the many difficulties. All traffic was in a great state of chaos and we had the feeling that we were just waiting for our train to crash into another one which had been left on the tracks, because the staff could not agree to man it and drive it away. We still cannot really understand how our train avoided accidents and got through safely. It was such an emotional journey. As we approached Sevastopol the train slowed down and stopped at a previously arranged spot some distance from town. There some motorcars were waiting to drive us along the picturesque mountain road – some three hours’ drive – to our destination Ai-Todor […]

[…] After we had been there for three days we slowly started wondering what had become of Xenia and her children, but then they turned up safe and sound after a smooth though arduous journey from St. Petersburg. For the first week or so life seemed quiet and normal. We had the feeling that we had avoided a dreadful storm, and were in safety in our little cosy nook far away from the centre where the revolution was boiling. My mother and my sister would drive out or go for walks and enjoyed the early warm spring sunshine, which was especially early arriving that year as if it felt that we were in extra need of comfort. After a while our tingling nerves started to calm down. In March the chestnut trees were in bloom and wild yellow crocuses pushed their heads up between the stones. It was spring everywhere you looked. The only thing that worried us was the thought of my eldest brother and his family. We wished many a time that we had had them with us. The house wasn’t particularly big but we shared it as best as we could. My husband and I lived in a room downstairs next to one of my nephews. Mother, her maid and my eldest nephew lived upstairs. The rest of the family had moved over to the old house nearby.

But unrest also found its way to our little refuge. One night we were awakened by a violent knocking at our door – then it was opened and we heard the rattling of arms while a voice said: ‘Keep quiet and please put your hands on top of the blanket’. A sailor armed to the teeth stepped in, shut the door behind him and said: ‘In the name of the Provisional Government you are not permitted to leave this room!’ We were much too astonished at first to say anything so just lay there staring at this heavily armed guard.

What happened next?

The family survived this episode (whereas Tsar Nicholas II, his wife and children were murdered by the Bolsheviks) and fled to Denmark, only to find the Russian army on their doorstep once more during WWII…

25 Chapters Of My Life: The Memoirs of Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, Last Grand Duchess of Russia by Paul Kulikovsky, Karen Roth-Nicholls and Sue Woolmans is out now published by Strident Publishing priced £16.99.

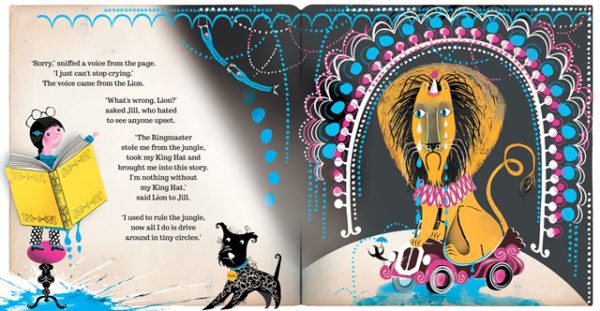

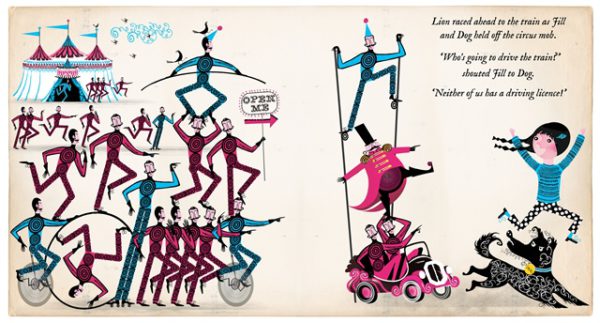

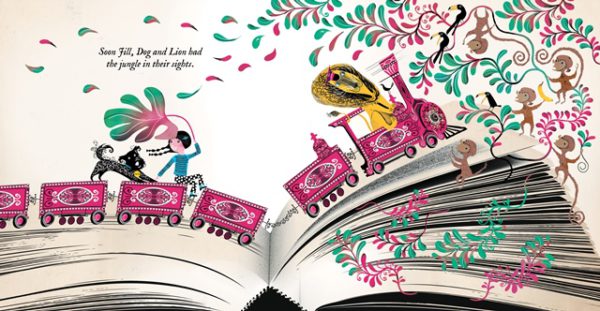

At Books from Scotland HQ we love this vibrant and dynamic book for children, Jill and Lion, by Glasgow-based illustrator and animator Lesley Barnes. In the stunning spreads below, our feisty young heroine Jill and her loyal companion Dog are back and ready for another magical adventure…

Lesley Barnes is an award winning illustrator and animator based in Glasgow. Her distinctive, bright and joyful work spans the worlds of fashion, music, children’s literature, film and product design. She is the author and illustrator of three children’s books.

Jill and Lion is published by Tate Publishing on Thursday 19th February priced £11.99.

Solnit’s lucid work offers an affirmative case for hope by tracing a history of activism and social change over the past five decades. This excerpt introduces Solnit’s central thesis, that profound and effective political engagement can lead us out of dark times by offering hope for, and the means to bring about, a brighter future.

Extract from Hope In The Dark

By Rebecca Solnit

Published by Canongate Books

It’s important to say what hope is not: it is not the belief that everything was, is, or will be fine. The evidence is all around us of tremendous suffering and tremendous destruction. The hope I’m interested in is about broad perspectives with specific possibilities, ones that invite or demand that we act. It’s also not a sunny everything-is-getting-better narrative, thought it may be a counter to the everything-is-getting-worse narrative. You could call it an account of complexities and uncertainties, with openings. “Critical thinking without hope is cynicism, but hope without critical thinking is naïveté,” the Bulgarian writer Maria Popova recently remarked. And Patrisse Cullors, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter, early on described the movement’s mission as to “Provide hope and inspiration for collective action to build collective power to achieve collective transformation, rooted in grief and rage but pointed towards vision and dreams.” It’s a statement that acknowledges that grief and hope can coexist.

The tremendous human rights achievements — not only in gaining rights but in redefining race, gender, sexuality, embodiment, spirituality, and the idea of the good life — of the past half century have flowered during a time of unprecedented ecological destruction and the rise of innovative new means of exploitation. And the rise of new forms of resistance, including resistance enabled by an elegant understanding of that ecology and new ways for people to communicate and organize, and new and exhilarating alliances across distance and difference.

Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognize uncertainty, you recognize that you may be able to influence the outcomes — you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others. Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists take the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting. It’s the belief that what we do matters even though how and when it may matter, who and what it may impact, are not things we can know beforehand. We may not, in fact, know them afterward either, but they matter all the same, and history is full of people whose influence was most powerful after they were gone.

There are major movements that failed to achieve their goals; there are also comparatively small gestures that mushroomed into successful revolutions. The self-immolation of impoverished, police-harassed produce-seller Mohamed Bouazizi on December 17, 2010, in Tunisia was the spark that lit a revolution in his country and then across northern Africa and other parts of the Arab world in 2011. And though the civil war in Syria and the counterrevolutions after Egypt’s extraordinary uprising might be what most remember, Tunisia’s “jasmine revolution” toppled a dictator and led to peaceful elections in that country in 2014. Whatever else the Arab Spring was, it’s an extraordinary example of how unpredictable change is and how potent popular power can be. And five years on, it’s too soon to draw conclusions about what it all meant.

You can tell the genesis story of the Arab Spring other ways. The quiet organizing going on in the shadows beforehand matters. So does the comic book about Martin Luther King and civil disobedience that was translated into Arabic and widely distributed in Egypt shortly before the Arab Spring. You can tell of King’s civil disobedience tactics being inspired by Gandhi’s tactics, and Gandhi’s inspired by Tolstoy and the radical acts of noncooperation and sabotage of British women suffragists. So the threads of ideas weave around the world and through the decades and centuries. There’s another lineage for the Arab Spring in hip-hop, the African American music that’s become a global medium for dissent and outrage; Tunisian hip-hop artist El Général was, along with Bouazizi, an instigator of the uprising, and other musicians played roles in articulating the outrage and inspiring the crowds.

Mushroomed: after a rain mushrooms appear on the surface of the earth as if from nowhere. Many do so from a sometimes vast underground fungus that remains invisible and largely unknown. What we call mushrooms mycologists call the fruiting body of the larger, less visible fungus. Uprisings and revolutions are often considered to be spontaneous, but less visible long-term organizing and groundwork —or underground work —often laid the foundation. Changes in ideas and values also result from work done by writers, scholars, public intellectuals, social activists, and participants in social media. It seems insignificant or peripheral until very different outcomes emerge from transformed assumptions about who and what matters, who should be heard and believed, who has rights.

Ideas at first considered outrageous or ridiculous or extreme gradually become what people think they’ve always believed. How the transformation happened is rarely remembered, in part because it’s compromising: it recalls the mainstream, when the mainstream was, say, rabidly homophobic or racist in a way it no longer is; and it recalls that power comes from the shadows and the margins, that our hope is in the dark around the edges, not the limelight of center stage. Our hope and often our power.

Hope In The Dark by Rebecca Solnit is out now published by Canongate Books priced £8.99.

Best-selling children’s author Lari Don writes exclusively on why she creates strong female characters in her books for children and young adults. Arguing that the fairy tale tradition of the helpless and passive female is damaging to women of all ages, Lari pertinently suggests that, to enable a true revolution to happen, we must stop telling ‘those old tales with princesses as prizes’.

Lari Don: Why I Write Strong Girls

A maiden is tied to a rock, weeping prettily as she waits to be eaten by a sea monster, then a hero swoops in to kill the monster.

A princess is offered as a prize, along with half the kingdom, to any hero who can slay the local dragon.

A girl ignores her mother’s advice to stay on the path, is eaten by a wolf, then cut free by a man with an axe.

I loved these stories as a girl. I thought those roles were the natural place for girls in fairy tales and legends. But I wanted more for myself, so I read Nancy Drew, I watched Wonder Woman, and I realised I could imagine my own stronger girls.

Now I write strong girls.

Lari Don

I write fantasy adventures for 8-12 year olds, with female protagonists who don’t sit about crying prettily waiting for heroes to save them. I write male characters too, just as brave and smart, flawed and foolish, as the girls. I try to treat my characters (whatever gender, race or species) equally. But in the end, it’s always my child characters who solve their problems, rather than waiting for a passing adult to intervene, and it’s always my female protagonist who saves herself and everyone else, rather than relying on a hero to defeat the monster.

That’s why Helen’s musical skill defeats the fairy queen in Wolf Notes and why Molly’s speed saves her friends in The Shapeshifter’s Guide to Running Away.

In my novels the girl defeats the monster, partly because she’s the main character, so that’s the satisfying way to end the story, but also because I’m still the child who read those fairy tales and wondered if girls could have other roles too.

And I’m not content to settle for weeping, waiting and weddings as the only jobs girls can have in fairy tales. Traditional tales are the wellspring of our culture. If the most popular stories are about passive girls, then boys and girls of every generation have to recognise and resist that message in order to grow up with any expectation of equality.

So I try to look beyond Victorian fairy tales with girls as passive recipients of heroism, and search out older stories with active and confident girls: the Sumerian goddess of war, the Chinese girl who defeats a seven-headed dragon, the little girl in a red cap who escapes from the wolf all on her own…

I don’t just write for girls. In fact I don’t write for girls at all. I write for adventure fans. For readers of any and all genders. It’s important that we all read about physically confident female characters and emotionally intelligent male characters, as well as the other way round.

There’s been a revolution in girls’ roles in fiction. In the 70s I had Nancy Drew and Wonder Woman. Nowadays I would run out of breath listing all the strong girls my daughters can read about and watch (and become!).

But we’re still telling those old tales with princesses as prizes, so perhaps the revolution isn’t over yet…

Lari Don is a children’s author and storyteller. Her books include the Fabled Beast Chronicles, the Spellchasers Trilogy (the second Spellchasers novel – The Shapeshifter’s Guide to Running Away – is published by Floris Books this month) and the collection of heroine tales Girls Goddesses & Giants.

Lari will be talking about creating strong female characters and telling heroine tales on 18th Feb 2017 at the Scottish Storytelling Centre in Edinburgh as part of the Audacious Women Festival.

For more insight into Lari, check out this interview here on Books from Scotland.

In this exclusive Q&A, Mike McInnes, author of Homo Passiens: Man the Footballer, explains the background to his science faction book which explores the evolution of mankind in relation to football – and ‘footballing genes’ – specifically.

Q. Why is your take on evolution so “revolutionary”?

A. Because it suggests that Homo sapiens is an offshoot of an older form of humans called Homo passiens – which goes against established theories of evolution as recounted in Yuvel Noah Harari’s book Sapiens: A Brief History of Mankind. Rational explanations of human evolution abound – for neoteny (our lack of a distinct adult form), for example, and ludeny (our propensity for adult game-playing); but no-one has provided a rational explanation for bipedalism – our ability to walk on two legs. Until me. Until now. Pretty revolutionary, eh? As is my idea that humans went bipedal and evolved all sorts of anatomical oddities in order to play games like football.

Q. What sort of odd anatomical features did Homo evolve that relate to its football prowess?

A. The narrow pelvis, for starters – with two hinged legs below. This inherent instability means we were/are always on the verge of toppling over, but we can change direction rapidly – backwards, forwards, upwards and so on. Our flat feet are levered for propulsion; outstep and instep, for bending and slicing; non-opposable big toes, for shooting. And our flat neotenous faces, with their non-sloping foreheads and non-protruding jaws, form a dome-shaped head – perfect for heading!

Q. This sounds like serious stuff – especially for a spoof! Is it based on fact?

A. Oh yes. Totally. The anatomy is spot on, and I follow Darwinian principles to the letter, as well as established theories like neoteny and ludeny, courtesy of serious academics like Harari, Huizinga and Jay Gould. Our robot future with Robo passiens? All true. I draw on several real – ologies – such as physiology, pharmacology, endocrinology and genetics – to create fantastic new concepts and biochemicals: the elbow gene for gain-of-function fouling (ELB HIT alpha-1), the cortisol analogue, scortisol; fannabinoids (similar to cannabinoids); scorotonin (very like serotonin); the award-seeking dopamine analogue, hopamine; and the beautiful hopoids (released during high-stress football matches).

Q. But it goes so much further than life science. Your entertaining claims are also backed up by earth science, archaeology and anthropology. Even particle physics! How does it all fit together?A. So easily. I extend existing thinking on human relics and culture across the world, spanning China, Orkney, the Isle of Man… Stenhousemuir… among others. Only with my amalgamated views will you appreciate that prehistoric petrospheres are abstract expressions of ancient football, or understand the significance of the mession particle that binds foot to ball (as discovered recently in the Great Hedron Collider), or value my predictions for the winners of the 2050 World Cup.

Q. You did this so well that, when I read the book, some of the things that I thought were fiction were – in fact – fact. Was this a deliberate

A. Absolutely. Truth is usually stranger than fiction. Even down to the truth behind the First World Cup competition and the coal-miners from West Auckland. This is precisely why the book works so well, because fact merges seamlessly with fiction, which adds immeasurably to the fun!

Q. There is a huge volume of specialist knowledge in this book – and not just about football! So where did you get it from and how do you convey this range of knowledge without readers doubting your credentials?

A. Well, I was a pharmacist and pharmaceutical innovator for many years. I also research in the field of sports physiology and carbohydrate metabolism. I was the instigator of the famous Honey Diet and have developed a formula for forward-provisioning of the brain during sleep. In my spare time, I’m forever delving into human culture, past and present, and of course spectating the beautiful game. To wrap up all this knowledge with aplomb, in a single credible character, I devised polymath and highly esteemed academic, the evolutionary scientist Professor Gordon P. McNeil, nominally from St Andrews University in Fife. He loves to throw his theories about with the slightest encouragement, especially over a pint in the “passiens” taverns (which also feature throughout the book, and were perhaps the hardest part of my research).

Q. Back to reality, then. What was the starting point for the book – the point at which the revolution “kicked” off – if you’ll excuse the pun?

A. Actually it was very specific. I was reading Harari’s book on Sapiens and came to a passage in which he discussed how humans lack genes for football. In his words: “Evolution did not endow humans with the ability to play football. True, it produced legs for kicking, elbows for fouling and mouths for cursing, but all that this enables us to do is perhaps practise penalty kicks by ourselves … human teenagers have no genes for football.” That really got me thinking and, the more I thought about it, the more I protested!

Q. Is the esteemed Professor Harari – author of Sapiens – aware of the revolutionary whirlwind his words have spawned?

A. Oh he is, totally! I sent him Gordon P. McNeil’s reaction to (attack on) his claims about humans’ lack of footballing genes. He loved it!

Q. I can imagine why footballers will love this book; it breathes life into certain mysteries and ideas relating to the gloriousness of football – the game, its players and its fans. Has the book been recognised by the footballing fraternity?

A. Oh yes! All the normal folk love it. And a bunch of those at the Scottish Football Supporters Association. And Irvine Welsh! In fact, somewhere between Trainspotting I and Trainspotting II he found the time to write the Foreword (or Forward) – in which he makes it all sound far more anarchic than I had intended.

Q. I can’t wait to read it properly. But what’s next on the agenda?

A. You’d think I’d outdone myself, wouldn’t you? Proving that penalty kicks are the highest expression of bipedal neotenous culture of mankind … But there is more! The book touches brain energy metabolism, and this relates to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia – a terribly serious issue in real life. That’s where I go next. Watch this space.

Homo Passiens: Man the Footballer by Mike McInnes is forthcoming from Swan & Horn.

Out of the many tartans available, Black Watch is undoubtedly one of the most popular. But how did this particular tartan come to exist? Here we reveal the story behind the iconic cloth from past to present.

The Black Watch was formed in the wake of the unsuccessful 1715 Jacobite Rebellion, where James Francis Edward Stuart (1688–1766), son of the deposed James II, fought to put the exiled House of Stuart back on the throne.

From 1725, General George Wade (1673–1748) formed six military companies from the clans of the Campbells, Grants, Frasers and Munros. They were stationed in small detachments across the Highlands to prevent fighting among the clans, deter raiding, and to assist in enforcing laws against the carrying of weapons. In short, they were tasked with protecting the interests of the Hanoverian throne in Scotland.

Wade issued an order in May 1725, for the companies all to wear plaid of the same sort and colour. Their original uniform was made from a 12-yard long plaid of the tartan that we know now as the Black Watch tartan. They wore a scarlet jacket and waistcoat, with the tartan cloth worn over the left shoulder. The name is said to come from the dark tartan they wore, hence “black”, and from the fact that they were policing the land, hence “watch”.

The Black Watch museum states that the cloth would be wrapped around both shoulders and firelock (a musket type of gun) in rainy weather, and served as a blanket at night.

The Black Watch saw action in the French wars (1745–1815); battles of the Empire (Crimea, Indian Mutiny, Egypt, Sudan, Boer War); First World War; Second World War; and (post Second World War) saw action in Korea; carried out peace-keeping duties in Kenya, Cyprus and the Balkans; and took part in the invasion of Iraq (2003–4). Since 2006, the Black Watch have been the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland.

Waverey Scotland Tartan Cloth Commonplace Notebooks

Text © Waverley Books

The Waverley Genuine Tartan Cloth Commonplace Notebook in Black Watch is out now priced £9.99. The tartan cloth for the notebook is supplied by and produced with the authority of Kinloch Anderson Scotland, holders of Royal Warrants of Appointment as Tailors and Kiltmakers to HM The Queen, HRH The Duke of Edinburgh and HRH The Prince of Wales.

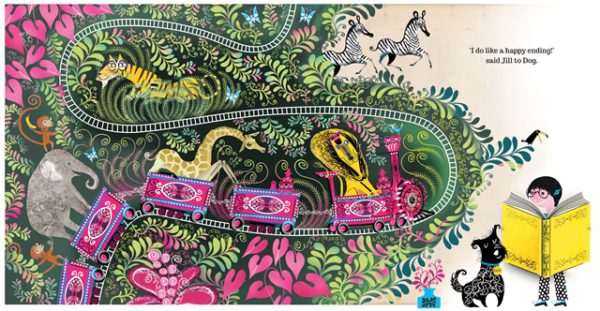

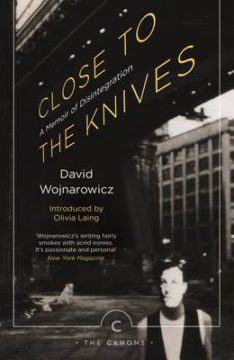

In this month’s column David Robinson encounters avant-garde artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz through two books: Wojnarowicz’s forthcoming ‘memoir of disintegration’ Close to the Knives, and Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City, which will both be published by Canongate Books in March. Delving into Wojnarowicz’s pioneering political oeuvre, Robinson makes clear his importance as both innovative artist and defiant activist.

One hundred years after the outbreak of the Russian Revolution – what the Bolsheviks called “the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution”, as opposed to their own “Great October Socialist” one – it’s easy to be cynical about revolutions and revolutionaries. A century later, the idealism of a few hardline optimists in 1917 has, after all, faded into the plutocracy and cynicism of Putin’s Russia. What’s to celebrate about that?

So I want instead to point to a different revolution and a different revolutionary – so different, in fact, that he might not have thought of himself as one. The one revolution that has made the biggest difference in my own lifetime is the bloodless one that has led to LGBT equality. Among people of my generation, every year that passes makes us look back with greater embarrassment at the “poof” jokes we used to laugh at in the 1970s and the bullying that children growing up gay would invariably encounter in the playground.

Let’s just pause for a while to look at how far we’ve come since then. These days, mainstream culture delights in highlighting the sexual intolerance that we may have on what we missed in our own times or which was completely covered up in the past. Polly Clark’s novel Larchfield, published next month and reviewed in my Books from Scotland column in March, fits perfectly into this pattern: we follow WH Auden’s search for a gay soulmate in straitlaced 1930s Helensburgh and – gay or straight alike – applaud his heroism in staying true to himself, in withstanding the massive gravitational pull of conformity. In the cinema, films such as The Imitation Game, Milk, and Pride – all, incidentally, also based on true stories – make essentially the same point. These are no longer arthouse films, no longer aimed at a niche market. Gay lives, we have quietly and collectively decided, matter.

Next month, Canongate Books will publish a new edition of artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz’s Close to the Knives, the “memoir of disintegration” he first published in 1991, a year before he died. This this takes us right back to a time when, as he saw it, gay lives didn’t matter at all. He was sick and tired, he wrote in 1987, of going to funerals and memorial services of friends who had died of AIDS – as he was to do himself – realising that that their loss had made no impact beyond the room in which the service was held.

“I imagine what it would be like,” he writes, “if each time a lover, friend or stranger died of the disease their friends, lovers or neighbours would take the dead body and drive with it in a car a hundred miles an hour and blast through the gates of the White House and dump their lifeless form on the front steps.”

That’s the side of Wojnarowicz – pronounced Wonna-row-vich – I want to concentrate on here. Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone gives an excellent portrait of his importance as an artist of the hidden side of late 1970s New York, of the squats in the empty buildings by the decaying Chelsea piers by the Hudson where the homeless could gather and gays could cruise, places of anonymous sex and casual crime, and enormous, unfettered freedom. Wojnarowicz’s paintings, film and photography fit neatly into Laing’s thesis about the loneliness and anomie of big city life, and as she writes in the introduction to Close to the Knives, his experience as teenage hustler and rent boy are key to the books vivid depiction of what it feels like to be an outsider in a homophobic world.

Wojnarowicz’s sheer rage, his insistence – against what was, in the 1980s, all the evidence to the contrary – that the lives of gay men dying from AIDS mattered is what makes him a revolutionary. The virus didn’t have a moral code, he insisted, and a society that thought it did was itself sick. Yet in 1987, when his mentor and former lover Peter Hujar was dying, in restaurants he would be asked to pay his bill by putting his money in a paper bag rather than just handing it over and thereby risk contamination with what Andy Warhol called “the gay cancer”. Prejudice was viscerally real, ubiquitous, tangible: this was a disease for which there was no end in sight, and no promising lines of research, no organised, civilised way of treating those with the virus. The only way to end AIDS, said the governor of Texas, was to shoot the queers. We in Britain might like to think of ourselves as more tolerant, but we weren’t: in the same year of 1987, three-quarters of us reckoned that sex between men was “either always or mostly wrong”. How did we get from there to here?

I don’t know the complete answer to that. I don’t know to what extent it was because as a culture we grew to love and celebrate the Freddy Mercurys, Elton Johns, and Boy Georges in our midst. In looking back at the social revolution that has all but wiped out anti-gay prejudice, I couldn’t tell you whether it was music, showbiz or the mid-1990s onset of combination drug therapies to treat AIDS that mattered more. Yet I have a feeling deep in my gut that when the recording angel finally gets around to doing the sums, David Wojnarowicz ’s eyeball-blistering howl of rage will be found to be part of the answer too. Because he scraped off the stigma when it still hurt to do so. Because he insisted on not being silent about that stigma both in his life and in his death.

I’ve already quoted from an essay in Close to the Knives where he realised the importance of making each death count, of holding the government accountable. When he died, his friends gathered outside the East Village loft in which he had lived with Peter Hujar. Hundreds of people walked in silence behind a black banner on which angry capitals announced DAVID WOJNAROWICZ 1954-1992 DIED OF AIDS DUE TO GOVERNMENT NEGLECT, and at an appointed spot, read his work and burnt the banner. 8pm, 29 July, 1992 was, notes Laing, “the first political funeral of the AIDS epidemic”.

There’s a coda to this story of a dead revolutionary. In October that year, AIDS activists staged an even bigger political funeral along the lines Wojnarowicz had envisaged. At 1pm on 11 October, they met on the steps of the Capitol, before marching off to the White House. Hundreds brought along the ashes of their loved ones. They dumped them through a chain-link fence onto the White House. David Wojnarowicz ’s ashes were among them. Is it really too sentimental to believe that it made a difference?

Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration by David Wojnarowicz and The Lonely City: Adventures in Being Alone by Oliva Laing are both published in paperback by Canongate Books on 2 March priced £10.99 and £9.99 respectively.

Alice Strang investigates the many women artists – and the many restrictions surrounding their vocation – in Scotland from 1885 to 1965. As artists Joan Eardley, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, Phoebe Anna Traquair and others struggled to achieve the same recognition and status as their male peers, the outstanding standard of the work produced by these modern Scottish women, against stifling societal odds, mark them out as trailblazers.

Extract from Modern Scottish Women: Painters and Sculptors 1885-1965

By Various Authors

Published by National Galleries of Scotland Publishing

Foreword: From Annan to Zinkeisen: Forty-five Scottish Women Painters and Sculptors’

By Alice Strang

In 1885 Sir William Fettes Douglas, President of the RSA, declared that the work of a woman artist was ‘like a man’s only weaker and poorer’.

…

As a general rule women were in the minority of [art school] students … Furthermore, the training received by male and female students was different, most significantly in terms of the limited access women had to the life class, considered ‘the bedrock of a professional art education’. In this class, models of both sexes posed, often in the nude, for the purposes of studying and drawing the human figure. It was considered morally degrading for women to view nudity and at most they were permitted to draw from a cast and later from a partially draped model.

Phoebe Anna Traquair, The Awakening, 1904 Oil on panel, 63.2 x 151 cm Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh Photo © National Galleries of Scotland

…

The question of women students’ access to the life class was embroiled in an established, gendered hierarchy of art genres, in which depictions of the human form were of the utmost importance. Painting was the most exalted, with flower painting broadly considered the most acceptable form for women to practise. As the writer Léon Legrange declared in 1860: ‘Let women occupy themselves with those kinds of art they have always preferred… the paintings of flowers, those prodigies of grace and freshness which can alone compete with the grace and freshness of women themselves.’

…

Women artists’ choice of subject matter was sometimes called into question … Joan Eardley’s Sleeping Nude, a painting of her friend Angus Neil, provoked upset when it was exhibited at the Society of Scottish Artists’ exhibition of 1955. As Christopher Andreae has explained:

It is hard to believe she did not know she was turning an art tradition on its head – a female painter painting a male nude was almost bound to be read as an assault on acceptable convention. No ‘shock horror’ headline would have followed it if it had been a male artist painting a female nude … It received, as Henry Guy describes it, ‘some inane criticism –directed at a “Girl Artist”– and poor Angus was likened to “an inmate of Buchenwald or Belsen”.’

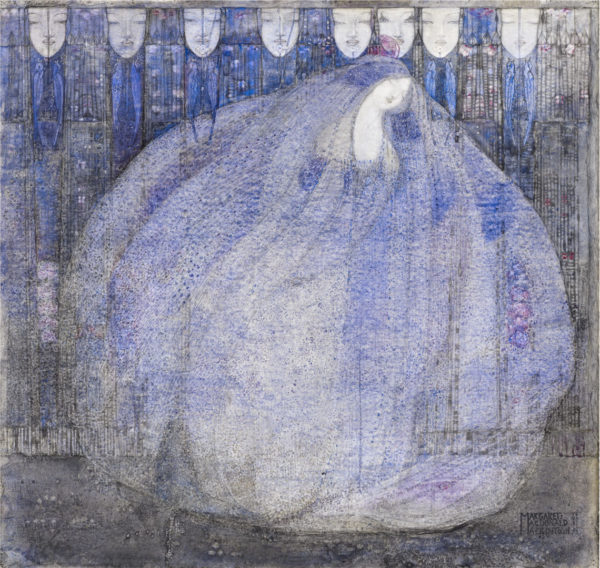

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, The Mysterious Garden, 1911 Watercolour, and ink over pencil on vellum laid on board, 45.1 x 47.7 cm Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh Photo © National Galleries of Scotland

Janice Helland has pointed out how contemporary commentators on the work of Mary Cameron, whose subject matter included bullfights and military scenes, were at pains to assert her femininity despite her subject matter: in an article about her as a ‘Scottish Artist at Work’ in the Scots Pictorial of 29 November 1902, Cameron was described as being ‘of great charm of manner, appearance and personality’, whilst Cameron herself stressed that being an artist ‘means hard manual labour … it means pulling up your sleeves and setting to work.’

Yet, attitudes towards women artists and their work were developing, as seen in a 1942 review in The Times of a women artists’ exhibition in London, whose author wrote: ‘is there any reason, any fundamental difference of outlook, which makes it necessary, or even especially useful, to show pictures painted by women apart from those painted by men? Historically there may have been such a reason, but it is hard to think of one which holds good to-day.’ The review then went on to single out Ethel Walker and Agnes Miller Parker for praise.

One of the most public forms of recognition for women artists practicing in Scotland between 1885 and 1965 was election to the membership of the Royal Scottish Academy … Josephine Haswell Miller was the first woman artist to be elected Associate Member of the RSA, in 1938. This was recalled in her obituary thus: ‘The significance of her achievement lies not only in her acceptance as an equal by her contemporaries and peers into a jealously guarded all male preserve, but even more to the fact that through her outstanding ability and effort she blazed a trail which she and others have followed to the lasting benefit of the Academy.’

…

As the twentieth century advanced, the achievements of women artists were increasingly marked with civic honours, including the award of Honorary Doctorates, such as those presented to Wilhelmina Barns-Graham; she was made a CBE in 2001 for services to art, whilst Ethel Walker was made a DBE in 1943. In 1982 and 1983 Mary Armour was made Honorary President of the GSA and of the RGI respectively. Of the former, she remarked of her first day as a student ‘if you had told me the day [I started at GSA] that one day they would make me president of the place, I would not have believed it, but it’s true.’

Norah Neilson Gray, Mother and Child, early 1920s Oil on canvas, 77.5 x 57 cm Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh Photo © National Galleries of Scotland

…

Overall, the varied experiences and achievements of the Scottish women artists examined here contradict Sir William Fettes Douglas’s opinion of them in 1885, at the same time as helping us to re-evaluate Scottish art history of the period from then until 1965. A century after Douglas’s speech, Cordelia Oliver was able to claim ‘the old imbalance between the sexes does seem to be lessening … by and large, all major exhibitions are open, now, to women on more or less equal terms.’ Perhaps the most pertinent rebuttal to Douglas was Ethel Walker’s declaration in 1938 that ‘there is no such thing as a woman artist. There are only two kinds of artist – bad and good.’

Modern Scottish Women: Painters and Sculptors 1885-1965 is out now published by National Galleries of Scotland priced £18.95. All images used here are taken from the book. You can read another excerpt from the book here on Books from Scotland.

MacLean’s extended political poem ‘An Cuilithionn’ (‘The Cuillin’) is featured here. Taking the iconic mountain range in Skye as a symbol for the international revolutionary movement, the poem has a significance which echoes far beyond time, country and language. An extract from this powerful poem is published here in Gaelic and English.

Extract from An Cuilithionn: The Cuillin 1939 & Unpublished Poems

By Somhairle MacGill-Eain | By Sorley MacLean

Published by ASLS

Please note: the poem below is in Gaelic and English

From An Cuilithionn 1939

Agus anns gach coire fòdhpa

gach breugaire sodail chum riù còmhnadh,

a choisinn bàrr am mòr-dhuaisean,

gach bàillidh, fear-lagha is uasal,

a dh’ith ’s a dh’imlich mun cuairt,

a shlaod ’s a spùill agus a ruaig:

bho gach coire agus sgurra

bhàrc an aon laoidh cuideachd:

“An ceann beairteis agus uaisle

gheibhear a-chaoidh ùidh nam buadhmhor;

thig is bheirear dhaibh mar dh’iarrar;

siud an comain ’s an lagh sìorraidh.”

Bhrùchd orm gàir chruaidh an iolaich:

“Tuath na leisge ’s na droch ghiullachd,

claoidh iad, tog iad agus sguab iad,

brist iad, iomain iad is ruaig iad.”

Thòisich na manaidhean air dannsa

’s gum b’ e i siud an iomairt sheannsail,

corranach an t-sluaigh a’ fàgail

an ceann gliongarsaich nan àrmann.

Thar farsaingeachd cuain agus àrainn

fhreagair Franco na Spàinne,

agus Pàp glas na Ròimhe

agus Chamberlain na seòltachd

agus caithream iolach Òdain.

Dhiùchd Bhinn is Barsalòna,

Seangaidh, Hamburg agus Hàirbinn,

Calcat, Boraraig is Lunnainn,

Pràtha is Napalais agus Muinich;

gach seòmar truagh fo roisg na grèine

don tig gaoir nam bochd ’s an èiginn,

mar a’ ghaoir air feadh an t-Sratha

a chuala Geikie is a bhrath e.

’S ged sgoilteadh guth eile an ceathach,

Lenin, Marx no MacGhill-Eain,

Thaelmann, Dimitrov, MacMhuirich,

Mao Tse Tung no a chuideachd,

bhàthadh an caithream diabhlaidh

guth nan saoi is glaodh nam piantan.

’S ged bhiodh neart is misneachd Stàilin

agamsa ri uchd na h-àmhghair,

chlaoidhteadh le sgread na fuaim mi

’s an Cuilithionn mòr a’ dol ’na thuaineal.

Air Sgùrr Alasdair ri lainnir

’s àilleachd airgid na gealaich ,

lean an glaodh ud ri mo chlaistneachd

dhrùidh is mhill e smior mo neairt-sa.

’S ged sheasadh ar Beinn Lì an uachdar

thar gach sgùrr agus bruaich dhiubh,

’s ged a chithinn creagan Bhaltois

a’ toirt bàrr air rèis na h-ealtainn,

’s ged bhiodh Beul Àth nan Trì Allt

mar a’ Bholga làn is mall,

leanadh sgread cruaidh a’ Chuilithinn

ri mo chlaistneachd ’na dhuilghinn.

’S ged chuala mi oidhche an talla

Phort Rìgh mo ghaoil, m’ eòil is m’ aithne

an seann seud, Dòmhnall MacCaluim,

siud a’ ghaoir a-mhàin a mhaireas;

is gus am bi an t-Arm Dearg còmhla

ri caismeachd tarsainn na Roinn Eòrpa,

drùidhidh iorram na truaighe

air mo chridhe ’s air mo chluasan.

Mìltean de dhaoine bochd air cnàmh

’nan closaich lobhte anns an Spàinn,

’s na ceudan mìle anns an t-Sìn,

ìobairt air am faide brìgh.

A liuthad Thaelmann anns a’ Ghearmailt

is “John Maclean” no a dhà an Albainn,

Mac a’ Phearsain fo ùir Chille Chòmhghain

’s an t-Eilean mòr glè rongach,

mise an seo air creagan spòrsa,

Alba a’ lobhadh an suain bhreòite.

From An Cuilithionn 1939 (English translation by Sorley MacLean)

And in every corrie under

every fawning liar who helped them,

who earned the cream of the big rewards,

every factor, lawyer and gent

who ate and licked around,

who stole and drove and plundered.

From every corrie and sgurr

surged the one hymn in unison:

“With wealth and rank

ever goes the devotion of the talented;

all they want will come and be given to them;

‘noblesse oblige’ and eternal law.”

Burst on me the hard cry of their slogan:

“Lazy, inefficient peasants,

oppress them, clear them and sweep them,

break them, drive them and rout them.”

The ghost band began a dance

and that was the auspicious exercise,

the coronach of the people leaving

mingled in the din of the gentlemen.

Over width of sea and march

answered Franco of Spain

and the grey Pope of Rome

and wily Chamberlain

and the revel-shout of Odin.

Appeared Vienna and Barcelona, Shanghai,

Hamburg and Harbin,

Calcutta, Boreraig and London,

Prague, Naples and Munich –

every poor room under the sun’s eye

to which comes the cry and extremity of the humble,

like the wail throughout Strath

which Geikie heard and did not conceal.

And though another voice split the fog,

Lenin, Marx, Maclean,

Thaelmann, Dimitrov, MacPherson,

Mao Tse Tung and his men,

the devilish revelry would drown

the voice of the wise and cry of the tortured.

And though in the face of distress

I had the strength and courage of Stalin,

the screeching noise would oppress me

while the great Cuillin reeled dizzily.

On Sgurr Alasdair, in the glitter

and silver loveliness of the moon,

that cry clung to my hearing,

pierced and spoiled my strength’s marrow.

And though our Ben Lee stood towering

above every sgurr and brae of them,

and though I saw the rocks of Valtos

excelling the birds’ career,

and though the Ford of the Three Burns were

like the Volga, full and slow,

the hard screech of the Cuillin

would cleave to my hearing, a distress.

And though one night in the hall

of my beloved well-known Portree

I heard the old hero Donald MacCallum,

that cry alone will remain;

and until the whole Red Army together

comes battle-marching across Europe,

that song of wretchedness will seep

into my ears and my heart.

Thousands of poor men rotting,

mouldering carcasses in Spain,

and hundreds of thousands in China,

a sacrifice of most distant effect;

the many Thaelmanns in Germany

and the one or two John Macleans in Scotland,

MacPherson in the earth at St Congan’s

and the Great Island languishing,

and I here on sporting rocks,

and Scotland rotting in sick slumber.

An Cuilithionn: The Cuillin 1939 & Unpublished Poems by Sorley MacLean is out now published by ASLS priced £12.50.

We are delighted to feature the Author’s Note and part of the opening chapter from The Jungle, Pooja Puri’s hotly anticipated debut novel, and the first book from new Edinburgh-based imprint Ink Road. Here we meet Mico as he navigates the many dangers of the migrant encampment in Calais, commonly known as ‘the Jungle’, including the merciless ‘Ghost-Men’…

Extract from The Jungle

By Pooja Puri

Forthcoming from Ink Road

Author’s Note

Much of the action of this story takes place in Calais, France. Here, on the border between land and sea, formerly lay the migrant encampment more commonly known as “the Jungle”. Its inhabitants came from far and wide – some to find a better life for themselves, others to escape political violence and war. The difficulties they endured on their journeys are unimaginable. Life in “the Jungle” was not much better. Facilities were, at best, basic; at worst, non-existent. There was little food. Charities did what they could but resources were limited.

While writing this book, I have tried to present as accurate a picture of the camp as I can. However, it is important to note that this story and its characters are a work of fiction. As such, there may be inevitable distortions between “the Jungle” as it existed in real life and the setting presented in the book. I hope, nonetheless, that in reading about Mico and Leila, readers can start to understand the despair and courage of those willing to risk everything for a brighter future.

Chapter 1

Mico was stealing.

He was lying in the dusty undergrowth, hidden by a screen of dense shrubbery. A thin layer of sweat had collected beneath his clothes; tufts of dirt and leaves clung to him like a second skin.

He inched forward. Ahead of him stood the tent. There were hundreds like it here, rising up from the ground like giant anthills. Small dots of people milled about them, their voices carrying across the air in an endless watery babble. If Mico closed his eyes he could almost imagine he was back home, fishing for squeakers or redfins. Almost.

The tent had been propped open with a bucket for ventilation, leaving just enough of a gap for him to see inside. In contrast to its neighbours, it was kitted out with everything: pans, clothes, a radio, chairs – real wooden ones, not the cobbled scraps used in the rest of the camp. The bread was on a table. Just looking at it made Mico’s stomach hurt.

Slowly he raised himself onto his haunches. He had been careful. He’d waited at the front of the camp until he’d seen the men leave. The newspapers called them people smugglers, but here they had a different name. They were the Ghost-Men. The men with magic; the spirits who could pass through borders without being seen.

There were always two of them. One was built like a crow, tall and beady-eyed; the second was a lizard, short with stumpy legs and stumpy arms. It was him you had to watch out for. Almost unconsciously, Mico raised his hand to his left shoulder. The skin had almost healed but there was a scar there now, a gift from the Lizard’s belt. He narrowed his eyes. One day, he hoped to return the favour.

Sometimes, the Ghost-Men would have other people with them, but today they had left alone. Mico had watched until they were no longer in sight of the camp entrance. He’d counted another five minutes just in case they’d forgotten anything. Then he’d crept the long way round the back of the tents. He’d made sure to stay deep in the bushes so that nobody would see him.

There were always plenty of people waiting for the Ghost-Men. Mostly new arrivals. They’d wash up on Calais hoping the Ghost-Men would help them. But the Ghost-Men were businessmen. Only if you could afford it would they spin their spell and help you disappear. Like him, most of them wanted to start a new life in England. For seven hundred pounds you’d get a place in a truck. It wasn’t the most secure option. Not now there seemed to be police on nearly every single checkpoint. Better to go in a car boot. Officers didn’t like stopping ordinary vehicles so as long as you had a decent-looking driver you’d be safe. But you needed money. A lot of it.

Mico shifted uneasily. He did not want to think what the Ghost-Men would do if they found him in their tent. But the bread was only a few paces away now. He gritted his teeth, readying himself to spring.

Suddenly, there was a movement to the far left of him. Mico dropped down like a shot. He saw the grasses rustle. Little by little, a foot emerged, followed by a hand, then the mud-stained face of a boy. He glanced warily around him, before taking a couple of steps forward. He stopped again, his ears pricked for any sound. Finally satisfied he was alone, he darted towards the tent.

A knife of frustration stabbed through Mico as the boy snatched up the bread. For a moment, he thought about confronting him. He could threaten to reveal him to the Ghost-Men. Force him to hand the bread over. But the boy was a lot bigger than him. A bruise the size of an orange gleamed on his chin. One thing was for certain. Mico wouldn’t be able to make him do anything.

He watched as the boy lay down on one of the camp beds. What was he doing? He had the bread. Why didn’t he leave? But the boy was clearly in no hurry. Snatches of tinny-sounding music swelled into the air as he turned on the radio.

“Get out, stupid,” whispered Mico.

The boy’s head snapped up. Mico instinctively flattened himself against the ground but it was not him the boy had heard. Through the long grass in front of him he saw the Ghost-Men entering the tent. The Lizard came first. The Crow, as always, followed behind.

The Jungle by Pooja Puri is published on 16th March by Black & White Publishing’s new YA imprint Ink Road priced £7.99.

In Creating Freedom, Raoul Martinez brings together a torrent of mind-expanding ideas, facts and arguments to dismantle sacred myths central to our society. In this Preface Martinez examines the language of freedom used today which ‘frames the most urgent issues of our time and the deepest questions about who we are and who we wish to be’, to ultimately propose that we must ‘reclaim’ freedom in order to transcend control over profit and power.

Creating Freedom

By Raoul Martinez

Published by Canongate Books

Preface

Free markets, free trade, free elections, free media, free thought, free speech, free will. The language of freedom pervades our lives, framing the most urgent issues of our time and the deepest questions about who we are and who we wish to be. Freedom is a stirring ideal, central to the concept of human dignity and visions of a fulfilling and meaningful life. Its universal appeal, its ability to unite and inspire, have long made it a powerful political weapon. For some it is a clarion call for revolution, for others a justification of the status quo. Academics, think tanks, religions, political parties and activists have recast the concept in different ways. In the scramble to define it, the ideal of freedom has been pushed, pulled, twisted and torn; expertly moulded to suit the interests of those with the power to shape it.

Even as they steer our economies, democracies and judiciaries, today’s dominant conceptions of freedom are unknown to most people. They are part of the conceptual foundation upon which society has been built, framing our thinking on everything from punishment and reward to capitalism and democracy. But this foundation, mixed as it is with myth and illusion, is crumbling. Plagued by civilisational crises – economic, political and environmental – the towering edifice it supports is not only unstable and unsustainable, but unjust. For too long the language of freedom has been used as a tool of control, helping to justify poverty, erode democracy and lend legitimacy to barbaric punishment.

As inequality soars, economic crises erupt, people work longer for less, as refugees surge across borders, corporate power intensifies, forests disappear and sea levels rise, it is time to engage in a fundamental reassessment of this hallowed ideal. When a society fails on multiple fronts, its foundational ideas must be questioned.

A simple principle animates these pages: the more we understand the limits on our freedom, the better placed we are to transcend them. We may well be less free than we like to think, but only through understanding the freedom we lack can we enhance the freedom we possess. Ignorance of our limitations leaves us vulnerable to those able to exploit them. Facing up to the limits on our freedom explodes a number of persistent myths – myths surrounding individual responsibility, justice, political democracy and the market. Some of these myths persist because they advance the interests of those in power; others because they flatter us, offering false comfort. All come at a price. The way we think about freedom shapes our view of the present and our vision of the future. It is a lens through which we interpret and evaluate the world, a compass by which we set our course. But not all conceptions of freedom are created equal. Each is based on assumptions about the world, some of which fly in the face of evidence and logic.

A sharp distinction is often drawn between questions of free will and those of political and economic freedom. Traditionally, these concepts have been separated into distinct categories, but this obscures more than it reveals. We dissect reality into manageable parts for study, but, if we do not put those parts back together in order to gain an understanding of the whole, we risk losing sight of the big picture. We risk losing touch with reality. This danger is inherent in modern education where the price of progression through the system is specialisation. Too often, where we should discover connections, we are taught to see impassable subject boundaries, but the limitations on our freedom are interconnected. A thorough understanding in one area enriches and changes our perception in others. To delve deeply into the meaning of freedom we have to breach disciplinary boundaries along the way. Insights and evidence from philosophers, psychologists, economists, historians, scientists, criminologists and environmentalists all play a role in the discussion to come. By building connections and teasing out their far-reaching implications, a radical, cohesive framework emerges – one that provides a much-needed overview of where we are and where we could be.

On the one hand, parts of society remain passive and deeply cynical about the possibility of change; on the other, social movements are rapidly growing around the world in response to the interlocking crises facing us. More and more people are questioning the systems that dominate their lives and diminish their liberty. Against this backdrop, it is time to reclaim the ideal of freedom for the urgent task of putting people and planet before profit and power.

We need a movement born of a shift in consciousness, one that will challenge the assumptions upon which our society is founded. To value truth – that elusive but all-important ideal – is to try and follow it beyond the shell that encloses our present understanding: to break through the defining labels of our inherited identity, the disciplinary boundaries that characterise our education and the limits set by society on our imagination. This book challenges ingrained assumptions about ourselves and the world and calls for an urgent transformation in our thinking and behaviour. It is a manifesto for deep and radical change. Through the prism of freedom, it examines the limitations of our dominant ideas and the failings of our current system, but it also explores the great potential that exists to create something better. The ideas and means to do this already exist, but we need to share them with each other, connect with each other and act on them. We need a revolution in our thinking that will spark a revolution in the way we organise our lives and structure our societies. A better world is possible, but if we take our freedom for granted we extinguish the possibility of attaining it.

Creating Freedom by Raoul Martinez is out now published by Canongate Books priced £20.00.

George MacLeod, founder of the Iona Community, is introduced as a Seanachaidh – Gaelic for storyteller – by Ron Ferguson who traces MacLeod’s journey back to his beginnings in Glasgow, preaching salvation to huge crowds on the streets of Govan.

Extract from George MacLeod: Founder of the Iona Community

By Ron Ferguson

Published by Wild Goose Publications

Tell Me the Old, Old Story

There is a Gaelic term, Seanachaidh (pronounced Shenachay), which fits George MacLeod. It means a story teller, a Celtic bard who tells tales and hands on the oral tradition. These folk tales are not just for interest, though they are truly interesting; they are told over and over, and the retelling helps bind the community together.

Jesus of Nazareth was, on one level, a Seanachaidh. He told vivid stories and parables which gripped the imagination. The tales had punchlines and stayed in the minds of his disciples, and are still retailed two thousand years on. The Sermon on the Mount was a composition of oft-repeated sayings and word-pictures which haunt the imagination. Vividness, concreteness and atmosphere are essential to such stories and sayings, which can be much more easily passed down the generations than can a thesis. St Columba of Iona was a Seanachaidh, his poems and word pictures luminous in the Celtic mist.

George MacLeod was aware of the power of the story. In his lectures to Church of England ordinands in 1936 (he also gave the Warrack lectures on preaching at Edinburgh and St Andrews Universities the same year) he advocated what he called ‘modern parabolic’ preaching – the use of powerful stories and images to engage the imagination. He practiced what he preached, repeating and repeating and repeating until his stories became a community litany.

How did the Iona Community really begin? The Seanachaidh tells it himself. ‘I remember preaching individual salvation in the street in Govan one day – yes to five hundred men on a weekday at 4 o’clock. What else was there for them to do in the market place but listen to curate or Communist? An outspoken man in question time, speaking almost as God spoke to Isaiah, asked: “Do you think all this religious stuff will save?” Very down at heel he was, but very clear of eye. Suddenly, as he was speaking, I realised he was preaching the gospel and not I. I asked him to come up on the platform, but he refused and left the meeting.

George MacLeod on the book cover

‘Some weeks later I received a message asking me to go to hospital and see a man called Archie Gray. I had never heard the name before, but when I reached the hospital I found it was my questioner from the meeting and he was dying of starvation. The man was single, in a whole household of unemployed, which he had left because he felt he was eating too much of the rations. Out of 21 shillings a week he was sending 7/6d a week to a ne’er-do-well brother in Australia. He said he was bitter about the Church, not because it was preaching falsehoods, but because it was speaking the truth and did not mean what it said.

‘Archie Gray was the true founder of the Iona Community.’

Typically, there are several versions of this story with variations and embellishments, all told by George at different times. The facts are now beyond recall: the truth lives on. At the heart of the myth there is the reality of a street encounter between an unemployed man and a privileged upper class preacher, in which the minister suddenly finds himself addressed by God in a moment which changes his life. To hear George retell the story with all the oratorical gifts at his command is first to be drawn into the Govan street crowd, and then to be addressed directly. Thus in the riveting modern parabolic preaching of the theatrical Govan Seanachaidh, a raw Glasgow street encounter becomes living story becomes contemporary Word-event becomes life-changing moment.

The story, and the repetitions of it, provides the main clue to the understanding of George MacLeod as he moves towards the founding of the Iona Community. It points to the burning heart of his conviction: that the Church has the message which the world needs to hear and it must not be apologetic about it in the face of other ideologies – but the message is being denied by the life and practice of the messenger. The story tells us more about George MacLeod than it does about the shadowy figure of Archie Gray. George despairs of the Church precisely because he loves it, and because he believes the Church to be the one body which can point the way forward for the world. The point is made in his lectures on preaching.

‘One of our local Clydeside brilliants, a quasi Communist who has smoked more of my cigarettes than any other man alive, suddenly burst into my room unexpectedly to proclaim, “You folk have got it: if only you knew that you had it, and if only you knew how to begin to say it.” It was his certainty that rebuked me; his implied need that moved me. What in effect he said was, “You know you could save me and you know you aren’t doing it.”

In leaving Govan, then, George MacLeod was seeking to make an experiment which would help the Church be true to its own message and, in a deep sense, to find its message.

George MacLeod: Founder of the Iona Community by Ron Ferguson is out now published by Wild Goose Publications priced £14.99.

Longlisted for the Walter Scott Prize of Historical Fiction, A Petrol Scented Spring shines a spotlight on repression, jealousy and love, and the struggle for women’s emancipation. Here we are introduced to sisters Arabella and Muriel Scott as Arabella’s desire to vote fosters a burgeoning interest, and later an active role, in political protest which leads the sisters to a London jail.

Extract from A Petrol Scented Spring

By Ajay Close

Published by Sandstone Press

A Petrol Scented Spring

I think of her as I saw her that day in Kensington, while Bill stopped Hilda from using the hammer she had brought.

That swan-like beauty. Serene amidst shattering glass.

Have you ever really looked at a swan? Curiously self-conscious. They hold their lovely necks so stiff it makes my shoulders ache. But if you rile them and they go for you with their stabbing beaks, they’re not so elegant.

I can’t be certain it was her. But this is my story, and hers was the face that floated into my head when I finally put two and two – or should I say, two and one – together. Hers or another’s, it doesn’t really matter. She’ll have felt the same blend of terror and elation. The suddenly-dilating capillaries. A kick-start from the adrenal gland. I went through something similar ten years later, the first time I performed an amputation, so I know how it feels to bluff your way through the unthinkable. And afterwards, to look in the glass and see the self you always hoped you’d become.

How could he not fall for her?

How can I not imagine myself in her shoes?

Arabella Scott.

Second sister in a brood of female brainboxes (with one petted baby brother) but, unlike so many other ambitious, intelligent Scotswomen, not a doctor. She can’t have been squeamish about gore, given what she put herself through, so why follow the more conventionally feminine path of teaching? Why else but ego? All those young hearts in love with her. Or am I being unfair?

She was used to taking a lead. That was the difference between us. The whole country was her classroom. She would instruct, and so improve, us all. What a marvellous chance she was given: to shout and smash and insult and burn in the name of high principle. All the petty irritations, the boredom – and God knows, it was boring, being a young woman then – all of it rolled up into a great yell of injustice. She saw the opportunity, and grasped it, while I went about coveting other women’s hats, and drinking myself lightheaded on Darjeeling, and flirting with young nincompoops, thinking myself quite the heartbreaker.

It starts at university. The old story. A new self. New friends. No one to pull you down, recalling that time the minister caught you watching his spaniel mounting Mrs Lawrie’s pug. If you want to be the very embodiment of high-minded intellect, who is to gainsay you? Then there’s the way your footsteps echo in the Old College courtyard, the freshness of your complexion against the grey stone, your crisp white blouse, the easy sway of your uncorseted gait, your waist so sweetly narrow in the cinch of your not-quite-ankle-length skirt. A bluestocking! A wholly new kind of woman – well, apart from lady novelists and Renaissance queens. The intellectual equal of any man, as rational and purposeful and far-sighted, but with an extra soulfulness. Born to show both sexes how far they fall short.

She has never given a thought to the vote, but now that it’s been mentioned, of course she must have it. And the women who come to speak at the Suffrage Society are so much the sort of women she would like to be. So assured and passionate and imperious. And it’s such fun, getting all dressed up to carry the banner, making speeches on a soapbox, heckling members of parliament.

It helps that she has her sister beside her. Dear Muriel. Clever, but not quite as clever. Courageous, but not in the same reckless way. She can’t remember a time when Muriel was not looking up at her with that admiring gaze. And part of what dear, loyal Muriel so admires is her big sister’s beauty. There’s no getting away from it: a beautiful woman can do things a plain woman had better not attempt. If it’s injustice that galls you, there’s injustice. Why should one pair of eyes, one nose, one mouth, be more pleasing than another? And not just pleasing: more aloof and unknowingly voluptuous, more like a ripe plum weighting down the branch.

Muriel is a solid little thing, her lips a little thinner, her eyes a little more bulbous. Touching in her true-heartedness, but not a beauty. They share rooms while studying at Edinburgh University. They walk to lectures together. They whip each other into a frenzy of indignation over the iniquities of our so-called democratic system. They admire the English heroines who get themselves arrested and starve in gaol, but their own roles are no less necessary. Chalking on pavements, handing out membership forms, waving placards at by-election meetings. In 1909 they travel to London to deliver a petition to the Prime Minister and are arrested for obstruction and sentenced to twenty-one days in Holloway Gaol, where they refuse to eat.

A Petrol Scented Spring by Ajay Close is out now published by Sandstone Press priced £8.99. Ajay’s new novel The Daughter of Lady Macbeth is published by Sandstone Press on 16th February priced £8.99.