For more than a century and a half the real story of Scotland’s connections to transatlantic slavery has been lost to history and shrouded in myth. As this foreword shows, this important book by leading scholars and historians sheds light on a previously untold area of Scotland’s history by uncovering the country’s connection to slavery in the Caribbean.

Recovering Scotland’s Slavery Past: The Caribbean Connection

Edited by Tom M Devine

Published by Edinburgh University Press

Foreword by Philip D. Morgan

Scotland’s connections to slavery can seem tenuous, almost nonexistent. After all, few vessels left Scottish ports for Africa to participate in the horrific slave trade. By the end of the eighteenth century, when England had a black population of about 15,000, perhaps fewer than one hundred black slaves resided in Scotland. Furthermore, Scots were in the vanguard of the abolitionist movement; and Scotland can pride itself as a pioneering abolitionist nation. A country that was about 10 per cent of the United Kingdom population contributed at times about a third of the petitions to Parliament advocating abolition of the slave trade. Iconic figures such as James Ramsay and William Dickson were in the forefront of the opposition to the slave trade. Moreover, in Duncan Rice’s view, scholars of the Scottish Enlightenment ‘perfected most of the eighteenth century’s rational arguments against slavery’. Scottish philosophers discussed slavery at greater length than their continental counterparts. Adam Smith’s famous The Wealth of Nations contains a condemnation of the slave trade and slavery not only as morally repugnant but as economically inefficient. Is it any surprise that many general histories of modern Scotland fail to mention slavery at all?

But the essays in this impressive collection make clear that, if Scots think their country has few or no connections to slavery, they are sorely mistaken. In effect, they are engaging in a form of collective amnesia, for in fact Scotland’s connections to slavery were extensive. Scots participated fully in slave trading from ports such as Liverpool, Bristol and London. At the height of the slave trade, a fifth of the ship captains and two-fifths of the surgeons manning slavers out of Liverpool, the world’s major slave-trading port at the time, were Scots. The image of Scots, dressed in tartan, playing golf by the slaving fort of Bance Island, Sierra Leone, points to the quotidian nature of Scottish involvement in that nefarious business. One Scottish slave trader thought so familiarly of slavery that he named his vessel after his daughter. This book shows that Scots owned and managed enslaved people in many New World slave societies – from Maryland to Trinidad, from St Croix to St Kitts. Scottish slave owners named many of their slaves and their plantations in ways to remind themselves of home. According to Edward Long, the historian of late eighteenth-century Jamaica, one-third of the whites on that island were Scots. Other societies such as Grenada and the other Windward Islands, as well as Demerara and Berbice, also experienced heavy Scottish influxes. In the early nineteenth century, Scots accounted for about a third of the planters on St Vincent. Scots fulfilled many roles within New World slave societies: from indentured servants to bookkeepers, from merchants to bankers, from attorneys to planters, from nurses to doctors. The scale of Scottish involvement in the slave economies and societies of the New World was therefore wide and deep. If Scotland can boast of its abolitionists, it should also take ownership of the many Scots who defended and profited from the institution. Even the slaves themselves took note of Scots: in one colony they tagged shellfish that clung to one another as clannish Scotchmen.

The economic links between Scotland and New World slave societies were impressive. Slave societies provided markets for Scottish textiles, herring and a range of manufactured goods. In turn, those societies supplied Scotland with tobacco, sugar, rum, coffee and cotton. Capital from the Chesapeake and the Caribbean made its way into Scottish industries and landownership. Indeed, as Sir Tom Devine suggests in Chapter 11, the small scale of the Scottish domestic market and the nation’s relative poverty probably accentuated the impact of the slave-based economies of the Atlantic. As he notes, there is evidence pointing to ‘an even greater per capita Scottish stake’ in British imperial slavery than for any of the other nations of the United Kingdom.

At the same time, this outsized Scottish involvement in the slavebased economies of the Atlantic must not be exaggerated. The Scots were not much of a presence in Barbados or some of the Leeward Islands. Between 1750 and 1834 only about 34,000 Scots travelled from Scotland to the West Indies, a small proportion of the Scottish population of just over 1.5 million in 1801. Furthermore, the Caribbean was a graveyard not just for slaves but for immigrant whites, many of whom died within a few years of arrival. A commercial handbook published in 1766 for ‘men of business’ in Glasgow recommended sending ‘two, three or more’ factors to the West Indies so ‘that on the death of one’, others could replace him. The famous volatility of the Antilles took its toll on Scots. The impact of slavery on the homeland was also limited in some respects. As Nicholas Draper emphasises in Chapter 8, only ‘between 5 and 10 per cent of British elites were close enough to the slave-economy to appear in the compensation records, as owners, mortgagees, legatees, trustees or executors’. The other 90 to 95 per cent had no discernible connections to slavery. Scotland, it is true, is over-represented among absentee slave-owning claimants, accounting for 15 per cent of them. Still, the point Draper makes about the general significance of slavery also applies to the Scots, namely that ‘slave wealth could be incidental in the sense that other sources of wealth appear to dwarf it in the composition of an individual’s overall net worth’.

More work therefore remains to be done precisely linking slavery to Scots at home and in the diaspora. The impact on Scotland – not just measured in investments but in everything from diet to country houses to material culture – will also need careful and precise calibration. But any claim that Scotland grew rich from slavery may not be easily sustained. The flow of profits from slaving and slave-related business, while notable, probably accounted for only a small proportion of domestic capital formation. The value added by the Caribbean sugar sector was approximately 2 per cent of British national income. As Devine notes below, ‘the origins of industrialism were far from being monocausal’. Rather, he adds, ‘the commitment of the landed elites to economic improvement, indigenous levels of literacy, the practical impact of improving Enlightenment thought, English markets within the Union, new technologies and the indigenous natural endowment of coal and ironstone resources, inter alia, were all part of the mix’. Slavery was important to Scotland’s development, as these essays abundantly and rightly demonstrate, but quite how profound the institution’s impact was awaits further investigation. Still, these splendid path-breaking essays point the way forward, by providing a sturdy foundation on which others can build.

Recovering Scotland’s Slavery Past: The Caribbean Connection edited by Tom M Devine is out now published by Edinburgh University Press priced £19.99.

Ever wondered how a book is illustrated? In this guest blog by the National Galleries of Scotland, we’re taken behind the scenes of the making of An Art Adventure, a specially commissioned colouring book by the talented Eilidh Muldoon who graduated from Edinburgh College of Art in 2013. So read on for an art adventure…

An Art Adventure

By Eilidh Muldoon

Published by NGS Publishing

An Art Adventure blog by Sarah Worrall, former Publishing Project Manager at the National Galleries of Scotland

I spend a lot of time immersed in long texts, questioning everything – making sure a book will become a complete and whole object; in tandem with all the labour that goes into the words from both author and publisher, will it be a nice product that people want to pick up and hopefully run off with…?

Illustrator Eilidh Muldoon at work

In keeping with this latter aim, I had the great pleasure of working with the illustrator Eilidh Muldoon on the latest National Galleries of Scotland Publishing venture, a children’s colouring book. It was a complete change for me – a book with very few words, and I was working with an artist, not an author. Eilidh had already worked with the Education Department at the Galleries, so they put us in touch and we began to discuss the possibility of a colouring book that takes people on a journey around the National Galleries of Scotland.

The book went through only a few drafts, with much valued input from several parties within and outside the Galleries. Meg Faragher, Families & Communities Learning Coordinator, held a tester day with some early proofs of the book, where it became apparent that all ages enjoyed colouring in and it became an activity that was happily shared between generations. I’d had initial doubts that a four year old would have the patience to colour in such (beautiful) detail. This doubt was quickly shot to pieces by several dedicated and focused four year olds.

Similar to Mindfulness colouring in, the book has a subtle narrative and aims to engage ‘readers’ with Edinburgh, buildings and works of art. Each time the book went for a revision, the pages came back to be met with genuine delight. I wanted the book to have a tactile sketchbook feel: something not too precious that can be carted about Edinburgh and enjoyed. My own four year old happily tested the dummy book’s robustness with a variety of pens resulting in no punctures and the binding holding strong.

I’m only used to working with InDesign and Microsoft Word files, so in the sometimes anxious pre-to-press moment I asked Eilidh, ‘if we need to change something within the illustrations at the last moment – do you have to redraw the whole page, or can you correct it magically?’ Cue a wise look from Eilidh: ‘Err, I can change it. By magic.’

Working drafts

Working drafts

The finished book

An Art Adventure: Around the National Galleries of Scotland is out now published by NGS Publishing priced £7.95. This article was originally published on the National Galleries of Scotland blog.

We’re also doing an exciting giveaway with NGS Publishing where you can win a copy of An Art Adventure and Charles Rennie Mackintosh In France. Find out the deadlines and how to apply in this article about the competition.

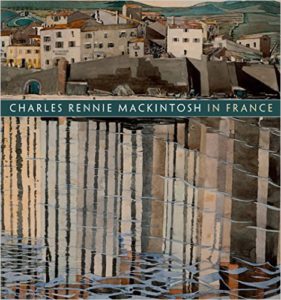

Towards the end of his life, Charles Rennie Mackintosh gave up his principal career as an architect and moved to the south of France where he devoted himself to painting in watercolour. This introductory excerpt contextualises these paintings in relation to Mackintosh’s wider career whilst the accompanying spreads showcase some key work from this lesser-known period of Mackintosh’s life.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh In France: Landscape Watercolours

By Pamela Robertson and Philip Long

Published by NGS Publishing

Today Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) is celebrated worldwide as one of the most creative and individual architect-designers of the 1890s and early 1900s. His achievements are promoted in international exhibitions and publications, and his works fetch world-record prices at auction. Such acclaim was not achieved in Mackintosh’s lifetime, and he spent the final four years of his life in quiet seclusion in the south of France, with his wife, Margaret Macdonald (1864–1933). There, he devoted himself to painting, producing a series of some forty watercolours depicting mountain landscapes, farm buildings, hill towns, ports and flowers. The watercolours are both highly sophisticated compositions and also important documents. In the absence of other evidence, they provide a valuable visual diary of the couple’s final years together, and resonant testimony to Mackintosh’s mastery of the watercolour medium. […]

When Mackintosh moved abroad in 1923, he began a period in his life and working practice which, in comparison with all the phases of his earlier career, can be characterised by its isolation. In France he produced a body of work that was required to satisfy nothing more than his critical temperament and a wish that his efforts might culminate in an exhibition. This is in marked contrast to the years for which he remains best known, the decade or so around 1900, when his work and his professional reputation were shaped in a more public way: through his relationship with clients, his critical reception, and his contact with progressive artists across Europe.

For Mackintosh, however, this vital period was short, and from around 1910 the story of his career is traditionally seen as one of decline. Fourteen years separate the completion of his final major building project (the second phase of the Glasgow School of Art, finished in 1909) and his departure for France. A range of circumstances contributed to Mackintosh’s difficulties during this time, not least changing fashions in architecture and the paralysing effects of the First World War. Although Mackintosh remained active as a designer and painter, the succession of unrealised architectural projects exacerbates a perception that his late watercolours are remote and detached in style from his earlier work. There was virtually no public awareness of the paintings he produced in France until their inclusion in the Mackintosh Memorial Exhibition held in 1933, a fact that contributes to a romantic interpretation of Mackintosh’s later circumstances. The paintings themselves, however, are made with a conviction and have a coherence which emphasises their importance to Mackintosh as a new phase in his work and, for him, the circumstances of their making must have been liberating.

Mackintosh’s French paintings are not made with the radical approach to art and design that characterises his more startling early work. In turning full-time to painting, it is fascinating to think that Mackintosh might have developed as fresh an artistic language as he had in his designs from the 1890s onwards, which as a young man had surprised his contemporaries and brought him attention from across Europe. The fact that his late paintings were not overtly avant-garde should not be interpreted as a consequence of a failing imagination. Rather, his French watercolours can be seen as a natural, fully orchestrated development of the sketches of buildings and landscapes he first made while a student, a development which is traced through the introductory works in this exhibition and more fully in the preceding essay. Here, it is important to emphasise that from the outset of his career Mackintosh produced sketches of buildings and landscapes and in some of the most interesting of these explored the interweaving of the man-made and the natural, as he would in his French works thirty-five years later. In tune with Arts and Crafts ideals and those of Fra Newbery, the director of the Glasgow School of Art who fostered Mackintosh’s talent, Mackintosh always viewed himself as an artist, and artistic values constantly underpinned his work as an architect and designer. His sketches played a crucial part in the development of his architectural vocabulary; they can be described as the germ from which his innovative designs grew. Painting itself remained important for him throughout his career and if his late works are considered in a broader artistic context, we find that not only are they in tune with British painting of the time, but they also show Mackintosh’s wider knowledge of recent developments in European art.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh in France, by Pamela Robertson and Philip Long, is published by the National Galleries of Scotland and priced £16.95. All images in this article are from the book.

We’re also doing an exciting giveaway with NGS Publishing where you can win a copy of An Art Adventure and Charles Rennie Mackintosh In France. Find out the deadlines and how to apply in this article about the competition.

This book exposes the stories of Scots who were guilty of dastardly deeds after leaving Scotland for America. These emigrants were rogues, con artists, charlatans and reprobates of the worst order. In some cases they literally got away with murder. Lundy explores their crimes in detail as this excerpt, on the centrality of a Scot – James Thomson Callender – to the controversial US presidential election campaign of 1800, shows.

Between Daylight and Hell: Scots Who Left a Stain on American History

By Iain Lundy

Published by Whittles Publishing

The US election campaign of 1800 between President John Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson was to go down as the most malicious and poisonous in American history. These two luminaries who had helped the U.S. shake off her colonial shackles engaged in vitriolic personal attacks, dirty tricks and mud-slinging that would make the most hardened modern-day spin doctor blush. Far from behaving like statesmen, they traded insults like street urchins. It was a disrespectful and slanderous campaign and it brought nothing but shame on the new nation but naturally, the two protagonists let others do the dirty work.

Enter the Scot James Thomson Callender. Callender had left his native land under a cloud and carved out a career in America as a salacious journalist. His writing was undoubtedly powerful and eye-catching, although it was filled with personal invective, and he had developed a reputation as a muck-raking guttersnipe.

Under a variety of pen-names, Callender had been responsible for almost all the shocking anti-Adams propaganda. Every lie, every libel, every last hurtful insult that dripped from Callender’s quill was approved and financed by the great Thomas Jefferson – the man known as the Apostle of Democracy.

The election campaign was Callender’s most spectacular offensive. He enjoyed expressing his anger in print; he had been doing it all his life, and it was his way of earning a living. John Adams was only one victim of his pen; he also had the temerity to write disparagingly about the father of the nation, George Washington, another founding father Alexander Hamilton, and then without compunction, he turned the tables and directed his venom with devastating effect at his old friend Jefferson.

The Bill Clinton/Monica Lewinsky affair may have shocked the nation during the 1990s, but the scandal-mongering of James Callender uncovered the first two major sex scandals in United States history. Whatever criticisms can be levelled at Callender’s behaviour and the tenor of his writing, he achieved something no journalist has managed to do since – he single-handedly determined the outcome of a U.S. election and thereby altered the course of American history.

Callender’s reputation as a polemicist had caught the attention of Thomas Jefferson. The two men had met in Philadelphia and, with an election looming, Jefferson decided he wanted the Republican-minded journalist as his attack dog to maul Federalist rival John Adams. He cautiously provided financial support but tried to keep a discrete distance.

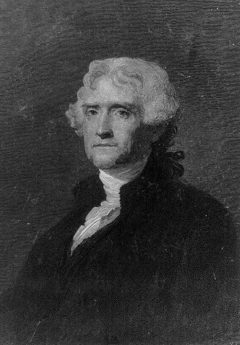

Thomas Jefferson from Library of Congress

In return for Jefferson’s patronage, Callender promised the future president ‘a tornado as no government ever got before, for there is in American history a specie of ignorance, absurdity and imbecility unknown to the annals of any other nation’. It was a dark warning of what lay ahead. Callender aimed to destroy the sitting president of the United States; little did Adams realise the character assassination he was about to endure. Callender was in the mood to repay Jefferson’s investment – and then some.

In early 1800 the ‘tornado’ that Callender had promised Jefferson arrived with the publication of his most famous pamphlet The Prospect Before Us. It was political dynamite; it savaged John Adams in a way no American politician had ever been attacked before or, arguably, since. Jefferson was sent a copy for his approval and remarked, ‘Such papers inform the thinking part of the nation’. The document contained 20 separate passages that were found to be libellous. A copy was sent to Adams when he and his family were at home in Massachusetts. What they read horrified them; they knew the election campaign had degenerated but not to this level.

Callender wrote that Adams, who had led the country since the 1797 election, was ‘mentally deranged’. If he was re-elected he would, said Callender ‘crown himself king’ of the United States and he was already grooming his son, John Quincy Adams, as his successor to the throne. Other examples of Callender’s venomous penmanship included:

He is not only a repulsive pedant, a gross hypocrite and an unprecedented oppressor but, in private life, one of the most egregious fools on the continent.

Future historians will enquire by what species of madness America submitted to accept, as her president, a person without abilities, and without virtues; a being alike incapable of attracting either tenderness, or esteem.

John Adams from Library of Congress

John Adams is a blind, bald, crippled, toothless man…who secretly wants to start a war with France while he is not busy importing mistresses from Europe.

Callender was charged with and found guilty of sedition, jailed for nine months and fined $200. However, Jefferson triumphed in the election, and his first act was to pardon and release Callender, although he could not have guessed at the turn of events that lay ahead. Callender’s demands for money or a government post, both refused by the new president, turned him against Jefferson.

Then on 1 September 1802 Callender’s paper, the Richmond Recorder, carried a ‘literary weapon of mass destruction against the President’. The newspaper report read: ‘It is well known that the man, whom it delighteth the people to honor, keeps and for many years has kept, as his concubine, one of his own slaves. Her name is SALLY. The name of her eldest son is TOM. …’ It added, ‘By this wench Sally, our president has several children…THE AFRICAN VENUS is said to officiate, as housekeeper, at Monticello’.

Yet again Callender had succeeded in finding his target by way of a scurrilous rumour. Jefferson had become the third serving U.S. president to be defamed in print by the Scot.

Author Iain Lundy

Finally it all backfired on Callender. Jefferson refused to dignify the allegation with a response, Virginia society closed ranks, and even Callender’s Federalist newspaper allies distanced themselves from him. Callender was jailed again in 1803 and ten days after he was released from jail, he was seen in a state of extreme intoxication in the streets of Richmond and the following day his body was recovered from the James River. Whether a drunken accident or suicide, it was a suitably melancholy end to a joyless life, and to a relatively short but bitter and tempestuous chapter in American political history.

Between Daylight and Hell: Scots Who Left a Stain on American History by Iain Lundy is out now published by Whittles Publishing priced £18.99

Celebrated Edinburgh-based author Alexander McCall Smith takes us through an urban landscape of ‘ fragile beauty, of secretive corners and sudden vistas’ as he connects Edinburgh’s colourful architectural heritage with being a unique and inspiring city steeped in literature.

A Work of Beauty: Alexander McCall Smith’s Edinburgh

By Alexander McCall Smith

Published by Historic Environment Scotland

City of Literature

Is there something in the Edinburgh water that explains why the city has produced so many writers? BBC Scotland, in a playful mood, broadcast a discussion on this subject some years ago – on the First of April. It is hard to imagine anybody falling for such an absurdity, but the setting of a city – if not its water – probably does help literary creativeness. Edinburgh is a city of fragile beauty, of secretive corners and sudden vistas – such a city will always attract writers and provide them with inspiration.

First built in 1622, today Lady Stair’s House is the home of the Writers’ Museum. © HES

In the nineteenth century Scotland held the attention of the romantic imagination in all branches of the arts, including music: Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture and Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor are examples of Scotland’s influence on composers, even if their actual experience of Scotland was slight. Painters, too, were drawn to the magnificence of the Scottish landscape, and indeed often exaggerated it in their romantic enthusiasm: Highland mountains often seem loftier in nineteenth century paintings, waterfalls whiter, mists thicker, and even stags more at bay. Reality may be impressive, but sometimes it is not quite as impressive as we would like it to be.

In literature, the greatest romantic of them all, Walter Scott, put Edinburgh at the heart of European literature, while at the same time effectively inventing an idea of Scotland that proved not only popular but also persistent. The literary critic Stuart Kelly has described that invention in his book Scottland: if it had not been for Scott, he suggests, we would never have all the familiar accompaniments of stage Scottishness: the ubiquitous tartans, the shortbread tins with Highland cattle, or even the songs of Harry Lauder and Kenneth McKellar. The point is well made, but even if Scott’s vision of his country inspired a raft of romantic contrivances, his literary achievement is still outstanding. Scott is generally credited with the invention of the historical novel. And it was no bad thing for Scotland, surely, that this small nation on the edge of Europe should have produced a writer whose fame was unequalled in his day. It was quite fitting then, that the city should have created for him a monument on such a scale. Most writers would be more than satisfied with a modest plaque on the side of their former home: Scott was given an astonishing spiky edifice, complete with winding stone staircases up which literary pilgrims may climb their way to the top. It certainly makes its point: altogether there are over 80 statuettes on its exterior representing characters from Scott’s novels or figures from Scottish history. To the modern eye it is, admittedly, odd to the point of being eccentric, but it is a landmark without which one of the best known views of Edinburgh – looking west along Princes Street – would appear very different.

The Scott Monument, photographed c1890. © HES

The story of Edinburgh’s association with literature does not begin with Scott, or even with Burns. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the Scottish court was enlivened by a number of poets, or makars as they are known in Scots, whose works laid the foundations of a national literature. William Dunbar, a poet, and David Lyndsay, a playwright, both found time outside their courtly duties at Holyrood to satirise the state of Scottish society. Lyndsay was the author of A Satire of the Three Estates, which is widely regarded as the first great Scottish play. That tradition of poking fun at human foibles is still strong in Scottish writing, and is probably the reason why Molière translates so well into Scots; more than one modern Scottish writer has produced Scots language versions of the French dramatist’s works, with one of these, Liz Lochhead’s Tartuffe, proving lastingly popular with the public.

Just about every street of any note in the Old Town has its literary associations. The area around the University is particularly rich in this regard, even if the University’s attitude to its architectural heritage has at times been disappointing. The redevelopment of George Square and some of the surrounding streets changed irrevocably an area of great character that could have been conserved and sympathetically modernised. As building after building was replaced, it has become increasingly difficult to find the sites in which men and women of note lived. Plaques that say something like On this site stood the house in which… are depressing reminders of how our connections with our cultural past may be lost, overnight, and so very easily. Cities have to change, of course, but change need not obliterate character and particularity. How dull life will be when we find ourselves all living in cities that look the same as each other – bland, utilitarian boxes of concrete and glass that could be anywhere, and are in fact nowhere.

Edinburgh’s close association with literature continues. It was the first UNESCO city of literature, a title given to a handful of cities that have particularly strong literary connections. It also has its own makar – an official poet – in the same vein as the poets that once received the patronage of the Scottish royal court centuries ago. In one view, poets should never be official, as ‘official poetry’ can often be strained and meretricious. Scotland’s official makars, both local and national, have been anything but that, and in Ron Butlin, who occupied the post in Edinburgh, we found a poet who captures the moods and ways of Edinburgh beautifully.

The ‘Banana Flats’, Leith – the home ground of Sick Boy in Trainspotting. © HES

In fiction, the contemporary city has been portrayed with verve and wit by writers who have set their face against the conventional vision of Edinburgh and have concentrated instead on those at the receiving end of society. Irvine Welsh presides over that school of Edinburgh writing, and does so with considerable skill and humour. Welsh’s Edinburgh – or Leith – exists, of course, and is part of the fabric of the city’s life, as is the dark underbelly that Ian Rankin describes in his Rebus novels. The contrast between worlds – the world of wellset middle class Edinburgh and the world of deprivation and desperation – is stark, but undoubtedly adds to the richness of the city’s literary portrayal. It is not necessarily a comfortable literature: there is resentment and irony and pawky irreverence. There is light and dark along with a great deal that is opaque. Which suggests that the Edinburgh literary imagination exactly mirrors the city it sets out to portray – a city of complexity and subtlety, revealed at one moment, concealed the next.

A Work of Beauty: Alexander McCall Smith’s Edinburgh by Alexander McCall Smith is out now published by Historic Environment Scotland priced £14.99. If you enjoyed this article you might also like this Books from Scotland Q&A with Alexander McCall Smith about his 2016 novel My Italian Bulldozer.

Scotland’s Landscapes tells the enduring story of the interaction between man and environment. Stunning new imagery from the National Collection of Aerial Photography comes together in this landmark book to build up a picture of a dramatic terrain forged by thousands of years of incredible change. Read on to discover how Scotland’s unique 12,000km coastline shaped the lives of Viking raiders when they arrived at Ardnamurchan around the tenth century AD.

Scotland’s Landscapes: The National Collection of Aerial Photography

By James Crawford

Published by Historic Environment Scotland

Coastlines

Sometime around the tenth century AD, on the Ardnamurchan peninsula in the western Highlands, a group of Vikings dragged a boat inland from a sheltered beach. This was no ordinary coastal landing, however. As they reached a low mound above the shore, they began to dig a hole in the earth about 5 metres long and 1.5 metres wide. After manoeuvring the boat into this channel, they then lowered the body of a dead warrior carefully down into its wooden hull. Once in position, they arranged a host of possessions around the body. A shield was placed over the chest, while a spear, axe and an iron sword – with a beautifully decorated silver pommel and a bone hilt – were laid alongside. They also added a bronze drinking horn, flints for making fire, a metal pan, pottery from the Hebrides, a bronze ring-pin from Ireland, and a whetstone from Norway. Finally, the boat was filled almost completely with rocks. This burial ritual was reserved only for Vikings of the highest status: for chieftains, or great, ocean-going adventurers. The boat itself was a symbol of a life connected intimately to the sea. It is surely no coincidence that this final resting place looks out past the island of Eigg and the rocky peaks of Rum to where the sun sets on the open water.

The Ardnamurchan Viking remained lost for over 1,000 years, until the grave was chanced upon in 2011 by a team of archaeologists working on the peninsula. Believing at first that the burial mound was debris deposited by farmers during field clearances, closer inspection revealed hundreds of metal rivets – many attached to rotten slivers of wood – laid out in the distinctive outline of the pointed prow and stern of a Viking boat. Fragments of an arm bone and several teeth were all that were left of the warrior. But, along with the possessions and the wooden remains, archaeologists believe that laboratory testing may reveal where this person came from, and even the origin of the trees felled to build their vessel. This discovery, thought to be the first complete Viking ship burial found on the British mainland, would be remarkable enough on its own. But it is in fact just one of a number of monuments to the dead left in this bay going back almost 6,000 years. On a hillock just above the Norse burial site there is a stone cairn built around 4000 BC, with an internal chamber where human remains were placed. Over time the way people were buried in this cairn changed, from cremations to tight bundles of bones, and then, a thousand or more years after it was first constructed, a single, complete body was laid to rest along with pieces of pottery. This last burial saw the cairn sealed for good. Yet about 1800 BC, and just 10 metres away, a new tomb was built.

Behind the small nineteenth century settlement of Sanna on the western tip of the Ardnamurchan peninsula, a vast crater of rock tells a story of the landscape going back some 60 million years. As the North Atlantic trench widened and the earth’s crust thinned, a line of volcanoes burst into the western seaboard of Scotland, running from St Kilda, Skye and Rum to Mull, Arran and Ailsa Craig. At Ardnamurchan, rings of once molten magma now define a series of concentric circles – known as a ‘caldera’ – which mark out the magma chamber and foundations of a giant volcano. The legacy of this turbulent geological past is a fertile landscape – today a farm even sits right in the centre of the ancient volcano – and a coastline of sheltered bays and rocky inlets that has seen thousands of years of human activity, from Neolithic and Viking burials to medieval castles and crofting townships. © HES

Again, a single body was placed inside, this time with a jet bead necklace – a sign of far-flung trading connections – before the entrance to the grave was blocked off. There was clearly something special about this place, something that, over an extraordinarily long period of time, brought different people and cultures to the same spot to commemorate their dead.

For millennia the coast has been a gateway for the people of Scotland – landing ground for hunter-gatherers; beachhead for Viking raiders; staging point to strike out to abundant fishing grounds; borderland to the open highway of the sea. With so many lives half-lived on the water, it seems no surprise that communities would view the coastline as a symbolic location for ritual and remembrance. Perhaps these monument-graves were placed deliberately on the ‘edge’, in a landscape part-earth, part-sea; a landscape that defined the traditions and myths of the people who lived there – and also of those who were just passing through.

Of course, not all remains are designed to be lasting memorials, and there is more to this one Ardnamurchan bay than just ancient tombs. Immediately to the west of the beach, on a rocky promontory overlooking the inlet, there is evidence of a fort dating back to about 200 BC, with traces of burning and slag that hint at a centre for Iron Age metalworking. A thousand years before the Vikings arrived to perform their burial ritual, it is clear that there was a strategic need to watch the seas and mark ownership of the surrounding land. And it does not end there. Close to the fort, on a crescent of hillside, there are the rocky footings left behind by a nineteenth century farming community. The people of this township had worked the land of the bay up until 1853 – and then their houses were abandoned and demolished to make way for a sheep pasture.

This is just one tiny fragment of Scotland’s near 12,000km of coastline, a sliver of land on a Highland peninsula now seen as remote to our modern eyes. Yet its long, varied history demonstrates the cultural richness of our coastal landscape, and the enduring importance of the sea. Take almost any beach, bay, dune or cliff-side, and you will find the layered traces of man’s presence across time, from ancient harbours, promontory castles and medieval saltpans to stone ‘fish-traps’ and smugglers’ caves. The shoreline has represented security, survival, opportunity and adventure over many thousands of years. Yet a day does not go by without the inexorable shift of this physical border. From the coming and going of the tides, to rising sea levels and the never-ending process of erosion, the histories and memories contained within this landscape are at once enduringly vibrant and dangerously fragile.

Scotland’s Landscapes: The National Collection of Ariel Photography by James Crawford is out now published by Historic Environment Scotland priced £14.99.

Extolling the many merits of the literary podcast, David Robinson reveals his favourites for you to discover and enjoy. Think you’re too busy in the run-up to Christmas to get downloading? Think again. This, David argues, is in fact a great time to immerse yourself in the world of audio available at just a click of a button. So ‘lie back and listen’…

I don’t know how you are about new technology, but me, I’m a late adapter. So late, in fact, that I still don’t want a smartphone and have only now, about eight years after everyone else, discovered podcasts.

Why did nobody ever tell me about them? Why did no-one ever shake me by the lapels and insist that I listen the New Yorker’s Fiction podcast? That I really ought to download John Lanchester’s exquisite exposition of the Brexit bungle – still the best I’ve heard – on the London Review of Books? That on no account should I miss the podcast of Melvyn Bragg and his assorted professors on Radio 4’s In Our Time distilling several lifetimes of learning into a 40-minute scintillating discussion of Orwell’s Animal Farm?

You think these are rhetorical questions? They’re not. I read books all the time, discuss them, go to book festivals. Professionally and personally, books and talking about books frame my life. So why have literary podcasts passed me by? Do they pass most people by too? Do people talk about them, recommend them to friends the way they do books? If so, why did that never happen to me?

I only wish it had. An iPod loaded with podcasts, somebody should have told me, is like having your own book festival, the only difference being that it’s one for which you can get all the tickets you want and they’re all free. But because nobody ever did tell me that, I’ve become that person instead. The kind who, eyes evangelically bright, will insist that you try trawling through the backlists of Backlisted, Literary Friction, Longform, Slate’s Audio Book Club, The Book Show from RTE, or Guardian Books. Whose recommendations will be simplicity itself: type Andrew O’Hagan, Ali Smith or Amos Oz into your iPod, lie back and listen.

So let me do you a favour. It’s nearly Christmas, and I bet there are still a whole load of chores you’ve still got to do. If it isn’t the seasonal shopping and queuing, it’ll be the usual cleaning and the ironing and walking the dog. This is all what we podguys call “dead time”. So: out with the iPod, in with the earbuds, click on (say) the New Yorker Fiction site and all of a sudden you’re listening to Margaret Atwood read a short story by Mavis Gallant and explain the roots of her fandom. Or Roger Angell, still writing immaculately at 96, reading John Updike’s late story “Playing With Dynamite” and remembering editing him. Or Allan Gurganus reading Grace Paley’s “My Father Addresses Me on the Facts of Old Age” and explaining just how much her mentoring meant to him. Or …. But you get the drift.

You’re probably wondering where the Scots are in all of this, and so am I. Yes, of course, you’ll find Damian Barr hosting The Literary Salon in London, and over the last five years a handful of fellow-Scots such as Maggie O’Farrell, Kirsty Wark, and Janice Galloway have joined him. And which literary podcast host can possibly compare to Jim Naughtie, who has been at the helm of Bookclub since 1998? The programme started off with Sebastian Faulks’s Birdsong, and there have been well over 200 since – all downloadable – with guests including Elmore Leonard, JK Rowling, Toni Morrison, Zadie Smith, Doris Lessing, Salman Rushdie, and Muriel Spark (talking about The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie: check it out). When BBC Scotland complain that the audience for a dedicated radio book programme just isn’t there, perhaps Naughtie could enlighten them: even on a late Sunday afternoon, Bookclub still manages to pull over more than a million listeners.

The BBC is, of course, a cultural powerhouse like nothing else in the language. Across its radio network alone, it offers no fewer than 513 podcast series, covering everything from pop to philosophy. And although Bookclub and Open Book on Radio 4 and the Arts & Ideas strand on Radio 3 might seem to be a small proportion of that, books and authors figure prominently in other programmes. In the last couple of months, for example, both Jackie Kay and Ali Smith have appeared on Desert Island Discs. I’ve read scores of print interviews with both of them (and written a few myself) but I’ve never come across ones that mirrored Jackie and Ali’s openness and generosity of spirit as clearly as their interviews with Kirsty Young – proof, if it be needed, that she is at least as good as anyone who has sat in the interviewer’s chair in the programme’s history. (Talking of which, because there are so many programmes in the Desert Island Discs podcast archive, if you started listening to 24/7 on 1 January, it would mid-May 2017 before you needed to find something else).

Apart from the BBC, Scotland doesn’t do as well as it ought to on the literary podcast front. The Herald attempted a few before giving up, the Scotsman never really did – both papers being too small and under-resourced to try properly – and Scottish Book Trust’s series of fortnightly alternating interviews and book group discussions, which started in October 2012 lasted for two and a half years before being abandoned.

When I think about it, perhaps this points to one of the reasons nobody has ever talked to me about podcasts. Maybe this very uncertainty about how something provided for nothing can ever make enough money to survive undermines our faith in podcasts’ viability, so instead of including them in cultural discussions they start to look like add-on, easily discarded extras. The contrast with audiobooks – where we all understand how publishers make money from their product – couldn’t be stronger. Over almost exactly the same period that Scottish Book Trust experimented with its own podcast series, national sales of audiobooks more than doubled.

Hats off, then, to two Scottish organisations that are out to prove me wrong. For the last seven years, the Scottish Poetry Library has been steadily building up an impressive (and well produced) pile of podcast interviews with and readings by some of the finest poets around. Again, because I have interviewed some of them of them, I can compare and contrast, and I must reluctantly concede that the SPL’s interviewers have often done a better job. There are nearly 240 to choose from, and as I have only just started listening to them on my daily dogwalk, I can’t yet give you a definitive report on which is the best. But if you try the ones with JO Morgan, Ian Bell, Niall Campbell, and Andrew Greig talking about Norman MacCaig, you’ll at least want to start off on your own poetry podcast pathway.

As I attend practically every Edinburgh book festival event it is humanly possible for one person to do, I have been in the audience at quite a few of the events from this year’s programme to have been given a podcast afterlife and can recommend the ones with Chris Packham, Kevin Barry, Edna O’Brien, Michel Faber. On my next dogwalks, I’ll start listening to the ones I missed out on at Charlotte Square in August, then do the same working backwards through the years. Then it’s back to the New Yorker Fiction, for another of Deborah Treisman’s elegant interviews, another classic short story, another discussion. By then it will probably be Christmas again. In the meanwhile, season’s greetings!

David Robinson is a freelance journalist and editor and from 2000-2015 he was books editor of The Scotsman.

Against the terrifying backdrop of bombs, the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq – NYOI – began in the most trying and tragic circumstances. In Upbeat the Orchestra’s compelling story is told by its musical director Paul MacAlindin. Listen to the NYOI, a beacon of hope and achievement, play Beethoven’s iconic Eighth Symphony below.

Paul MacAlindin

Upbeat: The Story of the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq

By Paul MacAlindin

Published by Sandstone Press

The story of the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq is here told by its musical director from its inception to its eventual end. The NYOI came through the most difficult and dangerous of times to produce fine music not only in Iraq but also in Britain, Germany and France. A beacon of hope and achievement the young musicians and their tutors made bridges across their own ethnic divisions, made great music in the most trying and tragic of circumstances, and became their country’s best ambassadors in 5000 years.

Author Paul MacAlindin discovered from an early age that he loved being an artist leading artists. As a musician, dancer and all-round performer, he found his voice through conducting, a passionate journey that has led him to work with orchestras and ensembles all over the world, from the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra to the Armenian Philharmonic to the Düsseldorf Symphoniker.

Upbeat: The Story of the National Youth Orchestra of Iraq by Paul MacAlindin is out now published by Sandstone Press priced £19.99. You can read more about the book, the NYOI, and it’s unusual genesis in this article here.

We’re delighted to launch an exclusive giveaway in collaboration with the National Galleries of Scotland where you can win two brilliant books!

An Art Adventure around the National Galleries of Scotland colouring and drawing book takes us on a journey through Edinburgh, visiting each of the three National Galleries of Scotland. Intricately illustrated and decorative, there are drawings to complete, colour and embellish, and paintings and sculptures from the National collection to be discovered! Enjoyable for all ages.

Eilidh Muldoon (Muldoodles) is an Edinburgh-based illustrator and designer. Eilidh Muldoon is the illustrator of the children’s book, Never Bite a Tiger on the Nose by Lynne Rickards. Much of her work is inspired by the iconic buildings in the city.

Known worldwide for his architecture and interior designs, Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) was also an extremely gifted painter. Towards the end of his life he gave up his principal career as an architect and moved to the south of France where he devoted himself to painting in watercolour. Meticulously executed and brilliantly coloured, these landscape watercolours are conceived with a sense of design and an eye for pattern in nature, which owes much to his brilliance as an architect and designer.

This book charts Mackintosh’s time in France and explores his career as a landscape painter, placing his work in the context of the modern movement. The forty-four paintings Mackintosh is known to have completed while in France are illustrated, and are supported by documentary photographs of the places he painted as well as extracts from his letters written to his wife and friends. This is the first publication to discuss in depth this period of Mackintosh’s work.

Check out the Books from Scotland Twitter here for details of how to apply; the giveaway will run until noon on the 13 December and the winner will be notified via a Twitter Direct Message that day.

The forthcoming December Issue of Books from Scotland will go behind the scenes of making An Art Adventure and there will also be an extract from Charles Rennie Mackintosh in France.

An Art Adventure: Around the National Galleries of Scotland by Eilidh Muldoon and Charles Rennie Mackintosh in France by a leading Mackintosh expert are out now published by NGS Publishing.

If you’re an art lover you also might like to know that the National Galleries of Scotland are hosting a major Joan Eardley exhibition from December 3rd. Why not check out this article on Books from Scotland about Joan Eardley’s life and work?

In this guest post from Scottish Book Trust, in celebration of Book Week Scotland 2016 (21-27 November) and the theme of Discovery, we explore some great books by Scottish authors that are definitely worth seeking out.

- All the Little Animals by Walker Hamilton

First published in 1968 and recently republished by Freight Books, All the Little Animals is the story of Bobby, a 31-year-old man with the emotional development of a ten- year-old boy, the result of a childhood car accident that killed his father. After the death of his mother, he runs away from a privileged but abusive life with his stepfather in London to Cornwall, where fate draws him to Mister Summers, a strange little old man who has inexplicably dedicated his life to burying roadkill. Bobby finds his true calling and the pair embarks on an idyllic but all-too-brief life together before the past catches up with shattering consequences.

- The Disappearance of Adele Bedeau by Graeme Macrae Burnet

The Disappearance of Adele Bedeau is the debut novel from Man Booker shortlisted Macrae Burnet, written before His Bloody Project. Manfred Baumann is a loner. Socially awkward and perpetually ill at ease, he spends his evenings quietly drinking and surreptitiously observing Adele Bedeau, the sullen but alluring waitress at a drab bistro in the unremarkable small French town of Saint-Louis. But one day, she simply vanishes into thin air. When Georges Gorski, a detective haunted by his failure to solve one of his first murder cases, is called in to investigate the girl’s disappearance, Manfred’s repressed world is shaken to its core and he is forced to confront the dark secrets of his past.

- Chronicles of the Canongate by Sir Walter Scott

A collection of short stories published between 1827 and 1828.

Set within a framing narrative told by Chrystal Croftangry, these three stories are set in the years following the Jacobite defeat and all feature characters who are leaving Scotland to seek their fortunes elsewhere. In ‘The Highland Widow’ and ‘The Two Drovers’, two young men find themselves torn between traditional Scottish loyalties and the opportunities offered by England. And ‘The Surgeon’s Daughter’ follows three young Scots to India during the first phase years of the British Empire.

- Espedair Street by Iain Banks

A little-known novel exploring rock pop excess in the seventies and eighties by the hugely popular writer of fiction. Daniel used to be a famous, not to say infamous, rock star. At 31 he has been both a brilliant failure and a dull success. He’s made a lot of mistakes that paid off and a lot of smart moves he’ll regret forever. Contemplating his life, he realizes he has only two problems: the past and the future.

- Skye: the Island and its Legends by Otta F Swire

Otta F Swire was the author of three books on Hebridean Folk Tales, all highly acclaimed as sources of folklore. Her most famous fan is Neil Gaiman, who cites her as a big influence, and who got the title of his novella, The Truth Is A Cave In The Black Mountains, from Swire’s account of a cave in the Cuillin mountains. Skye: the Island and its Legends, is a fabulous treasury of legend and wonder; tales of monsters who dwell in lakes, of small people who trap humans in earthen mounds where time stands still; of dark, shape- shifting spirits whose cloak of human form is betrayed by the sand and shells which fall from their hair. In the absence of a written tradition, for generations of Skianachs, these tales, handed down orally, contained the very warp and weft of Hebridean history.

- The Raiders by SR Crockett

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Galloway-based SR Crockett was a very successful writer. His popularity has necessarily declined over the years, but his best-known book, The Raiders, was republished in 2002 by Canongate Classics and is well worth seeking out. Caught up in the strife between smugglers on the Solway Coast and the gypsies of Galloway, young Patrick Heron is flung into a society of social outcasts, outlaws and downright murderers. But this world of moonlit confusion and bloody horror offers a kind of freedom, too, as Patrick travels far beyond the conventions of his day to enter a world made anew by fear and desolation and courage and energy. Crockett’s raciest narrative is full of the wild Galloway landscape which he knew so well and loved so much, informed at every turn of the plot by his delight in local history and old folk tales of the region.

- A Den of Foxes by Stuart Hood

Described by freelance critic Stuart Kelly as “work of supreme ingenuity”, A Den of Foxes was written by a former controller of BBC television and investigates what happens when Peter Sinclair, a writer and academic, receives an invitation to take part in a “war game”. The invitation comes from a man who writes from a part of Northern Italy Sinclair himself knows well – a part where he saw killing behind enemy lines during World War II. Sinclair decides to join the game.

- The Hundred and Ninety-Nine Steps by Michel Faber

A little-known novella from the author of the highly acclaimed The Crimson Petal and the White, The Hundred and Ninety-Nine Steps follows the story of Siân, troubled by dark dreams and seeking distraction, joins an archaeological dig at Whitby. The abbey’s one hundred and ninety-nine steps link the twenty-first century with the ruins of the past and Siân is swept into a mystery involving a long-hidden murder, a fragile manuscript in a bottle and a cast of most peculiar characters. Equal parts historical thriller, romance and ghost story, this is an ingenious literary page-turner and is completely unforgettable.

- The Comforters by Muriel Spark

In Muriel Spark’s fantastic first novel, the only things that aren’t ambiguous are her matchless originality and glittering wit. Caroline Rose is plagued by the tapping of typewriter keys and the strange, detached narration of her every thought and action. She has an unusual problem – she realises she is in a novel. Her fellow characters are also possibly deluded: Laurence, her former lover, finds diamonds in a loaf of bread – could his elderly grandmother really be a smuggler? And Baron Stock, her bookseller friend, believes he is on the trail of England’s leading Satanist.

- Caged by Theresa Breslin

Carnegie Medal winner Theresa Breslin explores the dangerous world of cage-fighting in this dark and powerful novel. Escaping from a troubled home and struggling to survive on the streets, the abandoned tunnels of the London Underground are a perfect sanctuary for Kai. Along with other teenagers running from their pasts, he finds somewhere to belong in this strange community of outcasts. But Kai is now facing a very different kind of fight. Every night, led by the enigmatic Spartacus, the runaways must become cage fighters, each fight broadcast to the outside world via YouTube. With gambling profits from these videos racking up, Kai and his friends hope to be able to start a new life. Yet treachery and danger are never far behind, and a new arrival threatens the order that Spartacus has worked so carefully to maintain. And then there is the looming finale, the last battle between Kai and his nemesis Leo: the Kill Fight…

There are hundreds of free book events running right across the country during Book Week Scotland (21 – 27 November). Events include ‘Design by the Book: A Scottish Publishing Showcase’ and literary afternoon tea with historical novelist Sara Sheridan both at Edinburgh Castle. Check out www.bookweekscotland.com for details of these events and more.

The author of a book about the new Scottish superhero on the block Slugboy – AKA eleven-year-old Murdo McLeod – reveals his top 10 superheroes. You can also sing along with the Slugboy theme tune!

Image Credit: Darren Gate

10. Thor

The only character in my top ten that makes it onto the list purely on the strength of his movies. Chris Hemsworth is brilliant and hilarious as the Norse God of Thunder, stealing scene after scene in the Avengers films.

Thor: [walking into a pet shop] I need a horse!

Pet Store Clerk: We don’t have horses. Just dogs, cats, birds…

Thor: Then give me one of those large enough to ride.

9. The Incredible Hulk

The strongest one there is. This guy once held up an entire mountain to keep his buddies from being squashed. Nuff said.

8. The Fantastic Four

Love the unique family dynamic of the FF. Plus the Human Torch and Thing help to keep things light-hearted, even when the fate of the world hangs in the balance.

7. The Avengers

Earth’s mightiest heroes, the Avengers are at their best when tackling ridiculous out-of-this-world threats that no single superhero could overcome.

6. Magneto

Superheroes would be nothing without supervillains, and they don’t come any better or more compelling than the master of magnetism. He isn’t out to rule the world. He’s not interested in power or money. All he wants to do is protect his kind – mutants – from persecution. Sure, he almost always goes about it the wrong way, but I like that he has noble intentions behind his diabolical actions.

5. Slugboy

Image Credit: Darren Gate

11-year-old Murdo McLeod isn’t your typical superhero. He’s small and scrawny and he’s absolutely hopeless. But he’s eternally optimistic, he never gives up… and his heart’s in the right place, bless him. Did I mention that he also appears in my fabulously funny new novel, Slugboy Saves the World? Available now in all good bookshops and online!

4. Captain America

In a world where a lot of superheroes are dark and edgy, Cap’s old-fashioned values are actually very refreshing. He believes in honesty and justice and he always tries to do the right thing. Simply put, he’s a really nice guy trying to do some good in the world. A terrific role model for young people everywhere.

3. Spider-Man

One of the few superheroes whose civilian identity is as much fun as his costumed alter ego. As Peter Parker, he’s an unpopular geek, contending with money problems, girl problems, school bullies, homework, exams and hiding his secret identity. As Spider-Man he has awesome powers, one of the coolest and most iconic costumes of all time… and he’s really funny! He also boasts some of the best villains of all time, including Doctor Octopus, Venom, Electro, Rhino, Mysterio and the Green Goblin.

2. The Uncanny X-Men

By far my favourite superhero team. No other team comes close. I could’ve quite easily filled this top ten with individual members of the X-Men, like Cyclops, Phoenix, Beast and Shadowcat, but it’s when these characters are combined that they really shine. The mutants have tackled lots of big issues over the decades and have featured in some of the greatest and most celebrated superhero stories of the last fifty years, including The Dark Phoenix Saga, Days of Future Past and God Loves, Man Kills.

To see the X-Men at their best, I highly recommend checking out Astonishing X-Men, by Joss Whedon and John Cassaday. Hilarious and heart-breaking, featuring widescreen action, pitch perfect dialogue, spot-on characterisation and beautiful artwork. It’s absolutely brilliant – everything a superhero comic should be!

So who could possibly beat the X-Men to the top spot?

1. Wolverine

Simply put – the best there is at what he does. Over the years he’s been a secret agent, a soldier and a samurai. He’s gone from being a hot-tempered loner to a devoted team member. He even joined the Avengers and became head teacher of the X-Men’s school! Through it all, he’s remained true to his character: a tough-talking, hard-as-nails brawler who doesn’t take any rubbish from anyone – and the greatest superhero of all time.

And last but certainly not least you can sing along with Slugboy to his theme tune!

Slugboy Saves The World by Mark A Smith won the Kelpies Prize 2015 and is out now (PB, £6.99) published by Kelpies.

In this thought-provoking excerpt Tattersall, a leading medical authority on diabetes, traces the evolution of the disease – named ‘the pissing evil’ in the 16OOs by the Royal Physician to King Charles I – in the twentieth century.

Extract from The Pissing Evil: A Comprehensive History of Diabetes Mellitus

By Robert Tattersall

Published by Swan & Horne

Given the thirty-year history of false dawns since 1889, it is not surprising that the reports about insulin from Toronto were greeted with scepticism, especially in Europe. It is said that Naunyn wrote to Minkowski telling him not to believe a word of it as it was another case of American bluff! However the imprimatur of the North American scientific community was given at a meeting of the Association of American Physicians on 3 May 1922, when Macleod presented the clinical results. No physician present seemed to doubt them and Rollin Woodyatt moved that the association give a standing vote of appreciation to Macleod and his associates. Joslin could not remember such an action in the twenty years he had been involved with the society. Insulin was first supplied to American physicians in August 1922 and their experiences were published in a special edition of Allen’s Journal of Metabolic Research; this did not come out until 1923. The journal contained ten papers and was 438 pages long.

It is a truism that a picture is worth a thousand words. The most impressive papers at that time were those by Rawle Geyelin and Kansas professor of medicine, Ralph Major; both were illustrated with before and after photographs of the children they had treated. The main aim was to fatten up these extremely emaciated children, so they were deliberately given two or three times more carbohydrate than they received previously.

One case in Geyelin’s paper was a 15-year-old girl who had developed symptomatic diabetes in 1918 and was treated with the standard regimen including occasional fasting days. In July 1921 she was admitted to hospital because she still had glycosuria on as little as 20 g of carbohydrate daily. She was eventually discharged with her carbohydrate and fat allowances halved. Unsurprisingly, she deteriorated over the next year and was so weak she could not go to school. In July 1922 she was admitted again, this time for acidosis, with a blood sugar of 428 mg/dL (23.8 mmol/L) and weighing just 46.75 lb (21 kg). She was discharged on an exceptionally restricted diet – 6 g of carbohydrate, 25 g of protein and 30 g of fat per day – on which she still had continuous glycosuria. In September 1922, on three control days before insulin was started she excreted 44 g of sugar per day, weighed 48 lb, and had generalised oedema. Over the next six months, while on insulin, she grew by 3.2 cm, her weight increased from 48 to 57 lb, and her daily carbohydrate was increased from 10 to 55 gm.

Another case described a 10-year-old boy with diabetes for four and a half years who, when admitted for insulin in November 1922, was so weak he could not lift his head from the pillow without help. Emaciation was extreme and he weighed only 27 lb (14.6 kg). Over the next three months he grew by 2 cm and his weight increased to 48 lb. On a diet of 80 g of carbohydrate a day he took 35 units of insulin per day. What is interesting from the chart in the paper is that the lowest blood sugar of 240 mg/dL (13.3 mmol/L) was recorded before he started insulin.

The most famous before-and-after pictures are those of a patient of Major – Billy Leroy. In the first picture, the three-year-old Billy had had diabetes for two years and weighed only 6.8 kg. In the second picture, taken after three months, his weight had increased to 13.6 kg and he was aglycosuric on a daily regimen of 55 g of carbohydrate and 25 units of insulin. These pictures were not representative of all patients who survived the Allen starvation regimen because, as Chris Feudtner pointed out, hardly any young patients starved to the degree of those shown in the dramatic pictures; they had lost 30% or more of their body weight, but 10% was more typical.

Joslin’s first patient to be treated with insulin (also reported in the Journal of the American Medical Association in June 1923) was Miss Mudge, aged 42, who had had diabetes for five years during which time her weight had fallen from 72 kg to 33 kg. She could not be kept sugar free on any diet and had only been out of her house once in nine months before beginning insulin in August 1922. Her weight increased by 9 kg and she had a normal blood sugar before and after breakfast on 10 units of insulin and 25 g carbohydrate. Twenty five years later, Joslin remembered that:

Colonel Palmer, a most brilliant young officer in the Canadian army whose career was shattered by diabetes just before the First World War, came back for insulin. When he saw the children, his first reaction was: ‘Now they make a noise’. Formerly they sat with protruding bellies, silent for hours, resignedly consuming their washed 3% vegetables. Yet today of those feeble creatures there is many a one alive, breathing and standing on his own feet. Von Noorden shuddered and turned aside at the sight of one of them a quarter of a century ago.

The Pissing Evil by Robert Tattersall (HB, £40) is published by Swan & Horn in November 2016

The Saltire Society’s annual literary awards shines light on Scotland’s wealth of literary talent and is a highlight of the cultural calendar. Here our columnist – and this year’s chair of the judges – delves into the 2016 Non Fiction Shortlist which includes five brilliant books by Amy Liptrot, James Crawford, John Moore, Richard Holloway, and John Kay.

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about literary prizes, because in the next couple of weeks, I’m judging one. As I write, we have still to pick the five category winners for the Saltire Literary Awards – best fiction, non-fiction, poetry, first book and history – and then the overall winner, but we’ve already chosen the shortlists.

At this stage, I could easily imagine any one of at least half a dozen books winning the overall prize. And it’s this part of the judging process – when everything is still up for grabs, when just one of the judges’ passionate advocacy could still sway the room, when doubts about front-runners have still to be articulated and certainties have still to be frayed by debate – that I like the best.

On 24 November, the overall winner of the Saltire Best Book of the Year will be announced, and the news will filter out across the media in headlines that will seem to spell certainty, resolution, and objective fact. But right now, the shortlisted books are all in play, every one of them, each with their own supporters ready to point out their originality, style, impact, narrative flair, depth of research, breadth of imagination and singularity of purpose, or any number of other qualities. All of the books are on the table – literally so: at our last meeting, they were piled up on the table around which the eight judges sat, a visual reminder of the sheer range of Scotland’s literary imagination.

Every time a literary prize is announced, the chair of the judges invariably says how the abundance of quality writing made picking the winner such a difficult decision. I’ll probably end up saying the same thing myself: just because it’s a cliché doesn’t mean that it isn’t also true. Meanwhile in the audience, many people will be inwardly muttering, ‘Yes, yes, of course. Now can we please get on with the main event? Can’t you just tell us who’s won?’ This time, as a judge, I almost want to change that around, to say: ‘Never mind who’s won. Just look at what we had to choose from.’

I don’t have the space to do that for all five categories, so let’s just look at one. I’ll pick non-fiction, and rather than subverting the judging process by looking at how the books in the category measure up against a general standard (style, originality etc), I’ll confine myself to looking at which of them was best at a particular one: filling the yawning chasms of my own ignorance.

There are five on the non-fiction shortlist: The Outrun by Amy Liptrot, Glasgow: Mapping the City by John Moore, Other People’s Money by John Kay, Richard Holloway’s A Little History of Religion, and Fallen Glory by James Crawford. Or, to put it another way, an acclaimed memoir about overcoming addiction on Orkney, a scholarly study showing how Glasgow grew, an economist’s critique of how the financial sector dangerously distorts our economy, a crisply written guide to the world’s religions and a history of the world’s greatest lost buildings.

In terms of books that did the most to fill in gaps in my own ignorance, I’ll keep them in that order too, ending up with James Crawford’s Fallen Glory as the book from which I learnt the most. Perhaps the things I learnt from the other books were more significant – the clarity of Holloway’s exposition of how doctrines of the afterlife and resurrection made their first appearance will stick in my mind, as will Kay’s takedown of a financial sector grown too big for its boots, whose profitability is overstated and which, after all, only directs 3 per cent of its total lending to firms producing goods and providing services.

But Crawford’s book – a 566-page history of the world’s greatest lost buildings – is, for me, a triple ignorance-buster. First of all, it tells me the kind of things that, in hindsight, I’m embarrassed that I didn’t already know – like precisely where the Tower of Babel was built and what’s there now, which is the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world, where the first lottery in Britain was drawn, or which 17th century siege (with, according to contemporary reports, a besieging army so large it occupied 30 square miles) made its victor the richest man on earth. *

Crawford realises that just as important as depicting fallen glories is showing what they reveal about human nature – both the grandiose dreams of their creators and the fantasies about the past sometimes unleashed by wishful archaeologists. Agamemnon’s tomb at Mycenae, for example, was visited by Himmler, Goering and Goebbels, lured by archaeology that – wrongly – seemed to hint that those fighting armies from the Age of Heroes were proto-Nazis. At Knossos on Crete, meanwhile, Arthur Evans was busy trying to prove the opposite – that the ancient Minoans had been civilised, sporting pacifists rather than bloody savages. The most recent evidence, Crawford points out, suggests that the archaeologists got it the wrong way round: the Mycenaeans were farmers and traders, while the Minoans certainly sacrificed humans and may well have been cannibals too.

But it’s the third, deepest level of Crawford’s ignorance-busting that impresses me the most. The first level is, after all just the pub quiz question: you either know the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city or you don’t. But Crawford has the knack of introducing new facts about stories you might have thought you already knew – facts which, although they might not radically alter the historical record, widen and deepen it immeasurably.

Take 9/11, for example, and look at it through the eyes of two architects. The first is Minoso Yamasaki, Japanese-American architect of the World Trade Centre. When it was finished in 1973, he went out on the roof of what was then the world’s tallest building with two of his colleagues. They celebrated with champagne, looking down on the planes landing and taking off from Newark airport ten miles to the west.

A year earlier, at St Louis, Minnesota, nearly a thousand miles further west again, in what Crawford calls the creation of “the first great American ruin”, the first three of the 33 tower blocks Yamasaki built in the 1950s were blown up (the rest followed in the next three years) after they became a byword for public housing policy failure. The destruction of the Pruitt-Igoe flats is one of the more spectacular moments in Godfrey Reggio’s 1982 film Koyaanisqatsi. It was, said architecture critic Charles Jencks, the moment modern architecture died.

Our second architect was four years old at the time the Pruitt-Igoe flats were blown up. Later, for his post-graduate degree, he studied in Germany, where his 162-page thesis took issue with the way in which western modernism – buildings like the Pruitt-Igoe flats or smaller-scale examples of Yamasaki’s ‘New Formalism’ – often overrode local architectural traditions. The architect was Mohammad Atta, and the city whose architecture, according to the thesis he spent five years putting together, was being swamped by western modernism was the one I’ve already mentioned twice without naming. You know, the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world. I didn’t know either, because for some reason they never mention it in all the news reports. Aleppo.

* Tower of Babel? That would be the Temple of Etemenanki in Babylon, south of Baghdad on a site levelled – and ruined – by coalition forces in the 2003 war. The first recorded lottery drawn in Britain was at the West Door of (Old) St Paul’s in London in 1569, and the 1687 siege of Golconda fortress in Hyderabad, centre of the world’s diamond trade gave Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb control of the south of India and made him vastly richer than he already was.

David Robinson is a freelance journalist and editor and from 2000-2015 he was books editor of The Scotsman. This year David is convener of the Saltire Society’s Literary Awards panel; find out more about the awards here. The winner of the Scottish Non Fiction Book of the Year will be announced at the awards ceremony on 24 November 2016.

Following on from the success of The Novel Cure, the Story Cure authors turn their attention to children and further their convincing case: that reading the right stories at the right time can help you see things differently and even be therapeutic. At Books from Scotland HQ reading is the best type of medicine that we can imagine…

Extract from The Story Cure

By Ella Berthoud & Susan Elderkin

Published by Canongate Books

Introduction

Between ‘Once upon a time’ and ‘happily ever after’ is a land we’ve all been to. Strange and marvellous things happen there.

Sometimes they’re things we don’t normally get to do – like riding on the back of a dragon, or finding the golden ticket to the chocolate factory. Often they’re things we want to do but are too scared or sensible – like running away from home. And sometimes they’re things we wouldn’t want to happen to us at all, but we’re very curious to know what it’d be like if they did – like being orphaned, or stranded on a desert island, or raised by a badger, or tragically turned into a rock. By the time we come back, brushing the dust off our hats, a new, worldly look in our eye, we alone know what we’ve seen, experienced, endured. And we’ve discovered something else, too: that whatever is going on in our actual lives, and whatever we’re feeling about it, someone else has felt that way too. We’re not alone, after all.

When we suggested, with our first book The Novel Cure, that reading the right novel at the right time in your life can help you see things differently – and even be therapeutic – the idea was surprising and new. That children’s books can do the same for children won’t surprise anyone at all. Parents, godparents, grandparents and kindly uncles – not to mention librarians, English teachers and booksellers (who are, of course, bibliotherapists in disguise) – have long been aware that the best way to help a child through a challenging moment is to give them a story about it, whether they’re being bullied at school, have fallen in love for the first time, or the tooth-fairy failed to show up. The best children’s books have a way of confronting big issues and big emotions with fearless delight, their instinct to thrill but also, ultimately, to reassure.* No rampaging toddler ever feels quite so out of his depth after Where the Wild Things Are. No pre-teen girl so alone with her questions after Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret.