This delicious and healthy recipe is sure to delight your taste buds! Chef Helen Partridge from the Ethiopian Vegetarian Food stall at London’s Greenwich Market also talks about her global culinary influences.

Brown Lentils: Ethiopian Vegetarian Food

You don’t see Ethiopian food in many markets, and Helen’s stall at Greenwich is a real find. Her food sings with simple clean flavours: tiny, crispy samosas so hot from the fryer you need to juggle them; warming, spicy chickpeas; a wonderfully soothing lentil and spinach soup, golden with turmeric. And these lovely little brown lentils, cooked simply with garlic, ginger and turmeric – guaranteed to turn around any cold winter’s day.

Serves 4

• 4 tablespoons sunflower oil

• 2 onions, finely chopped

• 3 tomatoes, finely chopped

• 3 garlic, finely chopped

• thumb-sized piece of fresh ginger, grated

• 1 teaspoon turmeric

• 250g brown lentils

• salt

Heat the sunflower oil in a large saucepan over a medium heat, and throw in the onions. Fry them until they are very soft and golden, then add the tomatoes, garlic, ginger and turmeric. Give it all a good stir, add a pinch of salt, and fry for another 5 minutes until the tomatoes have cooked down a bit and the fragrances are starting to sing. Pour in 1.2 litres of water, then add the lentils. Bring to the boil, then turn the heat down and leave to simmer for 45 minutes to 1 hour – the cooking time will vary according to the age of your lentils so if they’re not tender, give them a little bit longer. Add salt to taste and serve with rice and maybe some spinach on the side.

Q&A with Chef Helen Partridge

Name: Helen Partridge

Stall name: Ethiopian Vegetarian Food

What are your main culinary influences?

I am from Ethiopia and serve vegetarian food influenced by the flavours of the Horn of Africa. In Ethiopia they don’t use ovens – all the food is cooked over an open fire which is something you can really taste. Unfortunately I can’t do that in the market, but otherwise it’s really authentic!

What’s so special about Greenwich Market?

I trade at quite a few markets – Brick Lane, St Pauls, St Katherines Dock – and I think Greenwich has the best atmosphere. The traders are like a family and the market is a lovely mixture of tourism and local eccentricity. Just wonderful, crazy characters against a backdrop of stalls selling everything from vintage tins to toy cars and of course beautiful food!

This Ethiopian lentils recipe is from The Greenwich Market Cookbook (£15.99, PB), out now published by Kitchen Press

Jonathan Bennett has travelled all over the world to ride the waves, and in this interview he situates Scotland firmly on the surfing map. He also reveals how he came to write Around The Coast In Eighty Waves, which saw him live in an old, unheated campervan for fourteen months, including the coldest winter for thirty years.

Jonathan Bennett

When did you first start surfing?

I started far too late, in my mid-thirties, by doing a couple of week-long surf courses in northern Spain, first in Bakio and then in Zarautz (both of which are fabulous). I then spent hours and hours in the water in Barcelona, where I was living at the time. The surf isn’t great there, and very sporadic and short-lived, but it was better than nothing. This was just at the start of the surf school boom, before surf schools were more ubiquitous than seaside rock. I really wish I had started earlier – though it’s also almost never too late (though it’s such a physical and steep learning curve that the later you leave it, the harder it gets).

How long has the book taken to complete?

The trip itself took 14 months, including three or four month-long interruptions for various reasons, and including a second trip up to the north coast of Scotland to catch a few places I had missed, and to avoid the summer crowds down south. Then it took about three years to write the first draft, in between writing other things.

Where was the best surf you found?

I was completely at the mercy of conditions, because I wanted to make my way round the coast more or less in sequence, rather than jumping around to catch places when they were going to be at their best. But I happened to be at exactly the right place a handful of times, on pretty much every coast line. I happened to stumble across fabulous waves at Thurso (Caithness), Bantham (Dorset), Freshwater West (Pembrokshire), Godrevy (Cornwall) and a little-named reef just north of Whitby (Yorkshire) – though you’ll have to read the book to find out where it is!

Which was the most challenging area you surfed in and why?

The Hebrides were fantastic, but very isolated, and I was surfing on my own most of the time. It’s not very advisable, but I had no choice, and the isolation added an extra frisson of excitement. Sandwood Bay is a challenge because it’s four miles from the nearest access point, so you have to drag your board, wetsuit, food and water over four miles of moorland. It’s worth it, though, for the feeling of surfing off the corner of Britain, and the waves were among the most powerful I came across. Apart from that, there are a handful of reefs around Britain (Thurso, Porthleven, the Gower) that are on the edge of my ability, and which filled me with fear and foreboding – though whenever I caught a wave, the fear was replaced by absolute exhilaration.

What was your motivation for undertaking this project?

I wanted to surf more, and I wanted something substantial to write about – I was in a bit of a rut trying to get TV scripts commissioned. I thought I could take a few months out, write a bestseller and return to mega-stardom. I was way out on the timing. And on everything else, it turns out.

Have you got plans for another challenge?

I would love to do a similar project either in Europe, or Ireland, or just focusing on islands in Britain. At the moment, though, it’s enough of a challenge to get into the water, so my plans are currently on hold.

If you had the chance to surf anywhere in the world, where would you choose?

That’s a really tricky one! Indonesia or the Mentawais, probably. Or the South Pacific. But everywhere is so busy, and I’m not good at hustling for waves, so I would probably take a deserted Hebridean beach over most places.

What is your advice for those new to surfing?

Give up and go home, because it will ruin your life. And anyway, there are too many people in the water. You don’t want to add to their number, do you? Failing that, start young. Failing that, live by the sea and surf every day.

Most of all, do a course, preferably somewhere warm like Spain or Portugal. Having a decent instructor will save you a lot of time flailing around in the shallows (though you’ll still do a lot of that anyway). And more specifically, when you’re really just starting, make sure you’re far enough forward on your board. You always see learners trying to surf with their board at 45 degrees, and you’ll never catch a wave like that.

Around The Coast In Eighty Waves by Jonathan Bennett is out now published by Sandstone Press (PB, £8.99)

Free Love by Ali Smith

I was in my twenties with a small baby on my hip, dreaming of all the things I could have been. Then I read this. It transported me – the everydayness of the stories and their sudden shifts into freedom and love.

The Trick is to Keep Breathing by Janice Galloway

A brilliant (and original) dissection of grief and mental breakdown that demonstrates how subject matter can also mirror form.

Case Histories by Kate Atkinson

OK, anything by Kate Atkinson really but I love this series following former police detective Jackson Brodie as he navigates the only accounting sheet that matters: ‘Lost on the left, Found on the right’.

The Pirates in the Deep Green Sea by Eric Linklater

Read to me as a child while holidaying in the West of Scotland, this is the perfect underwater adventure. Set in and around a fictional Scottish Isle.

The Adoption Papers by Jackie Kay

Our new Makar’s first collection. Three voices, separate and entwined, tell the story of what it means to have more than one mother.

Mary Paulson-Ellis

And the Land Lay Still by James Robertson

The sweep of life and politics in twentieth century Scotland. It includes a scene in Brownsbank Cottage, last home of our great cantankerous poet of nationalism, Hugh MacDiarmid. I came upon that passage while on a writers retreat at Brownsbank Cottage (first writer-in-residence, James Robertson…) Scotland’s literary history flowed through my veins.

The Vanishing Act of Esme Lennox by Maggie O’Farrell

I’m always eager to read Edinburgh writers who also write about Edinburgh, as I do, and this elegant story of a lost life recovered that slides between the city of the ‘30s and the present day is a lyrical gem.

Report for Murder by Val McDermid

I enjoy Tartan Noir (Rankin, Mina, Welsh et al), but my entry point to crime was this delight. Journalist Lindsay Gordon investigates murder most foul in a girls’ boarding school. Only discovered much later that McDermid was an obsessive reader of my own childhood favourite, those Chalet School girls.

The Missing by Andrew O’Hagan

Wonderfully evocative narrative non-fiction – part reportage, part social history, part memoir exploring the world of those who ‘disappear’.

My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin

This irrepressible coming of age tale was a passion of my youth. Written in the 1890s when the author, Stella Franklin was only 16, it is quintessentially Australian. But her (often drunk) tutor on the cattle station where she grew up was a Scot who introduced her to literature; and it was first published by Blackwoods in Edinburgh. She also went on to serve in Elsie Inglis’ Scottish Women’s Hospitals during WW1 so I think it counts. An amazing independent spirit.

The Other Mrs Walker by Mary Paulson-Ellis is out now, published by Mantle/Pan Macmillan.

Mary will be appearing at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on 22 August 2016; details are here. She also appears at the Bloody Scotland Festival on 10 September 2016; details are here.

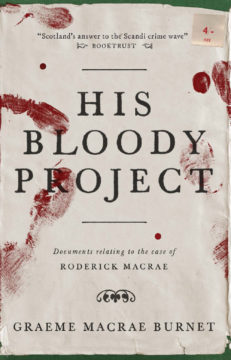

Books from Scotland is delighted that His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet is one of thirteen books longlisted for the 2016 Man Booker Prize. Published by Contraband, an imprint of the independent Scottish publishing house Saraband, the novel is a crime thriller and already it has been singled out in The Guardian’s article of 27 July as the most “eye-catching” book on the list. Serious Sweet by Scottish writer AL Kennedy (Jonathan Cape) is also on the longlist.

His Bloody Project is the story of a savage triple-murder in a remote crofting community in the 19th century. The question is not who did it – 17-year-old Roderick Macrae freely admitted to the killings – but why did he do it? Graeme Macrae Burnet ingeniously recounts the story of the murders and the subsequent trial with the aid of Roderick’s memoir, along with court transcripts, medical reports, police statements and newspaper articles.

The longlist was chosen from 155 submissions published in the UK between 1 October 2015 and 30 September 2016. The judges noted that publishers large and small are represented with six titles from Penguin Random House imprints (Harvill Secker, Jonathan Cape, Hamish Hamilton, Viking); two from Simon & Schuster’s Scribner UK imprint; and five from independent publishers, including Saraband, Faber & Faber, Salt, Granta and Oneworld.

The shortlist of six books will be announced on Tuesday 13 September at a press conference at the London offices of Man Group, the prize’s sponsor. The shortlisted authors each receive £2,500 and a specially bound edition of their book.

The 2016 winner will then be announced on Tuesday 25 October in London’s Guildhall at a black-tie dinner, one of the highlights of the publishing year. The ceremony will be broadcast by the BBC. The winner of the 2016 Man Booker Prize will receive a further £50,000 and can expect international recognition.

In this excerpt James Crawford introduces Fallen Glory and explains how he came to be interested in tracing the biographies of some of the world’s most fascinating lost and ruined buildings. Arguing that the lives of these iconic structures were packed with drama and intrigue, Crawford gives unique insight into how buildings combine war and religion, politics and art, love and betrayal, catastrophe and hope.

Fallen Glory: The Lives and Deaths of Twenty Lost Buildings from the Tower of Babel to the Twin Towers

By James Crawford

Published by Old Street Publishing

Introduction

Several years ago I visited the ruins of the palace complex of Knossos on the island of Crete. It was an early morning in September, but the sun was already very hot, and the surrounding olive groves throbbed with the scratching of the cicadas. I had just smashed my big toe against an ancient – and well hidden – flagstone, and was bleeding profusely into the ground: my inadvertent offering to a site that archaeologists believe was once used for human sacrifice. I liked to imagine I might be standing somewhere within the labyrinth built to hold the infamous mythological resident of Knossos – the Minotaur. Had I been one of the Athenian youths sent to feed the monster, I would have been in big trouble: limping through the maze in my cheap, plastic flip-flops, leaving a trail of blood in my wake. At the northern fringe of the ruins, I could see a broken chunk of portico propped up by three columns, each painted a deep orange. On the wall behind the columns, a bright fresco showed a bull bending its head to charge. This is one of the iconic show-pieces of the site, a fragment framed in a million tourist photographs, including my own. And it is a fake.

In 1900, the English archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans bought the entire site of Knossos and its surrounding land. He embarked on a massive programme of excavations, and then began what he called his ‘reconstitutions’. There is nothing ancient about the portico. It is, in fact, one of the very first reinforced concrete structures built on Crete, and its construction was overseen by Evans himself.

Evans has come in for a great deal of criticism over the years. Some say he was carried away by his passion for classical mythology and lost track of his duties as historian and scientist. The less kind verdict presents him as an odious product of Victorian Britain: egocentric and supercilious, he is accused of creating a skewed account of the origins of Cretan civilisation that was more about his own repressed sexuality than the actual archaeology. I suspect Evans would never make my personal dinner party dream team – how do you cater for someone who, throughout his time on Crete, continued to import his food by the crate-load from England, and refused to drink the local wine? – but I can’t help but feel some affinity with what he was trying to do at Knossos. After uncovering the remains of a building situated at the centre of one of the ancient world’s most significant cultures, Evans wanted to go further still. I think of him standing among the excavation works, looking out at the surrounding amphitheatre of green, terraced hills, letting his mind wander back to the mid-second millennium BC . He wanted to know the story of this great palace. How was it born and how did it die? Who were its kings, princes and queens? What did they believe in? What was the basis of their faith? What formed the inspiration for their wondrous art? Evans’ response to these questions was perhaps extreme and ill-judged, but I can’t fault his enthusiasm. I feel the same whenever I’m confronted by a ruin, or by a story that begins ‘where you are standing now there was once…’ The scattered stones are not enough for me. I want to rebuild these fallen glories in my mind’s eye and let them live again.

I have experienced this sensation in a number of places around the world. I remember climbing the steps of the Paris Metro at the Place de la Bastille, to be greeted by a blast of car horns and a buzz of scooters.I took a seat at a pavement café and looked out over a roundabout and past a bronze ‘freedom’ column to the glass and stone bulk of the Opéra National. But there was no trace of the Gothic fortress-prison that once provoked a revolution. The only remaining fragment of dissident spirit I could spot was some anti-Sarkozy graffiti, high on an apartment wall.*

In London, I have crossed the Millennium Bridge from the Tate Modern many times. Faced with Wren’s masterpiece, I can’t help but picture a different city skyline. If the Pudding Lane bakers had been less cavalier about fire safety, would Old St Paul’s, one of the largest, most venerable – and most ramshackle – medieval Cathedrals in Europe, still crown Ludgate Hill in place of today’s iconic, baroque dome?

Once, on a summer road trip through Andalucia as we drove west out of Cordoba, a Spanish friend pointed through our windscreen across a grass plain towards a complex of stone buildings in the foothills of the Sierra Morena. These were, he told me, the remains of one of the greatest palaces in Spanish and world history, the Madinat al-Zahara. It was early evening and, with the sun dipping, we took a detour to the ruins. The battery in my digital camera was dead, but I can still see in vivid detail the low light turning the stones red and the dramatic panorama across the plain. I imagined the last caliph enjoying this same view a thousand years earlier – perhaps just days before a civil war erased this dream palace forever.

There is no question that we invest our greatest structures and constructions with personalities. We care about buildings – sometimes, perhaps, more than we care about our fellow human beings. We shout with joy when we raise them up; we weep with sorrow when we destroy them. And, of course, we do continue to destroy them – buildings young and old, all over the world. Even the longest human life barely exceeds a century. How much more epic are the lives of buildings, which can endure for thousands of years? Unlike the people who made them, these structures experience not just one major historical event, but a great accumulation of them, in some cases stretching all the way from the prehistoric era to the present day. In its lifetime, the same building can meet Julius Caesar, Napoleon and Adolf Hitler. What human could claim the same? If we let them, buildings have the potential to be the ultimate raconteurs. These are some of their stories.

* My visit was before the Je suis Charlie marches in January 2015, since when the Place de la Bastille has once again been covered in ‘dissident’ messages.

James Crawford is Publisher at Historic Environment Scotland. Born in the Shetlands in 1978, he studied History and Philosophy of Law at the University of Edinburgh, winning the Lord President Cooper Memorial Prize. He has previously written a number of photographic books, including Above Scotland: The National Collection of Aerial Photography, Victorian Scotland, Scotland’s Landscapes and Aerofilms: A History of Britain from Above. In 2013, he wrote and acted as design consultant on Telling Scotland’s Story, a short, graphic novel-style guide to Scottish Archaeology published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Fallen Glory: The Lives and Deaths of Twenty Lost Buildings from the Tower of Babel to the Twin Towers by James Crawford is published in paperback by Old Street Publishing priced £12.99 on 12 July 2016.

Alpha, by French author Bessora and award-winning graphic novel and picture book artist Barroux, goes right to the heart of today’s political landscape. Books from Scotland introduces Alpha and showcases some stunning illustrations from this timely forthcoming book.

Alpha is a powerful collaboration by French author Bessora and award-winning graphic novel and picture book artist Barroux. Alpha tells the story of protagonist Alpha Coulibaly, whose wife and son have left Abidjan on the Ivory Coast for Paris. Travelling without visas, Alpha cannot contact them. Finally, in desperation, he sells up and attempts to follow. With a visa his journey would take hours; without one it takes months. Alpha is a story of endless dirt roads, refugee camps, people traffickers, perilous sea crossings and constant danger. Along the way Alpha meets an unforgettable cast of characters – wannabe footballer Antoine, little Augustin, the beautiful, damaged Abebi – whose varying experiences challenge dehumanising discourse around migration.

Alpha is translated from French into English by Sarah Ardizzone and it is introduced by former Children’s Laureate Michael Morpurgo. Mairi Kidd, the MD of publisher Barrington Stoke who commissioned the translation of Alpha into English, spoke to Books from Scotland about why the book is so important: “We believe that Alpha is quite simply a story that needs to be told. It is a first-person ‘diary’ that reminds us that each one of Cameron’s ‘swarm’ of immigrants is an individual. Bessora set out to have Alpha ‘whisper into the reader’s ear’ and his voice is very real, very human, complex, and often conflicted. In the light of recent political developments we are especially proud to publish a book that does not flinch from portraying the brutal reality of the great humanitarian crisis of our times. It is a cry for help and care. Of course, it is also a Scottish commission of a French translation. Vive les relations amicales entre nos pays!”.

For the Alpha artwork, illustrator Barroux chose to create it using simple felt-tip pen and wash, materials that Alpha himself might be able to access. Books from Scotland is delighted to show you some spreads from Alpha below.

Alpha: Abidjan to Gare du Nord will be published by Barrington Stoke as part of their Bucket List imprint priced at £16.99 for the hardback edition. Alpha launches at the Edinburgh International Book Festival with Barroux and a special live performance on Saturday 13 August. You can read more about this exciting event here, part of Edinburgh International Book Festival’s Migrant Stories series.

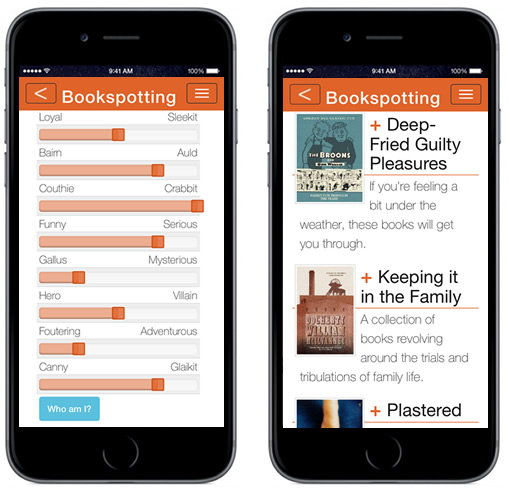

The new Books from Scotland Issue on Architecture, Innovation and Design launches later this week. In the meantime we wanted to highlight some of the best Scottish book-related apps out there and the best bit is that they’re all free. Find out about Bookspotting, Edinburgh’s Bookshops, When Wine Tastes Best and LitLong: Edinburgh below.

Bookspotting helps you to discover Scottish-interest books – from old favourites to the latest reads – making the most of the functions built in to the smartphone in your pocket. It features a host of titles with a strong connection to a place, a landscape, an island, or a city in Scotland, and using GPS technology geo-locates a wide range of books – fiction, children’s, history, humour, Gaelic, Scots, and travel – even when your phone or tablet isn’t online. A collaboration between Publishing Scotland in Edinburgh and Saraband Books and Spot Specific in Glasgow, Bookspotting features over 3500 books and links them to character, place, setting, author, date and theme. Find out more about the Bookspotting app here.

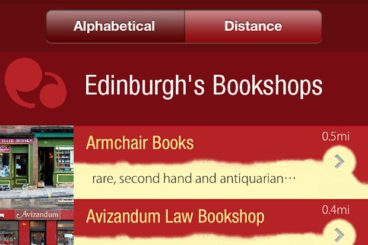

Edinburgh’s Bookshops is a free iPhone app and website trail launched by Edinburgh UNESCO City of Literature Trust. It brings together the capital’s fifty-two bookshops in one handy guide. Offering a comprehensive overview of all of Edinburgh’s brilliant bookshops as well as highlighting handy information such as opening times, contact details and shop-specialities, the app and trail gives readers and book buyers the definitive guide to finding their ideal bookshop in Edinburgh. Find out more about the Edinburgh UNESCO City of Literature Trust’s app here.

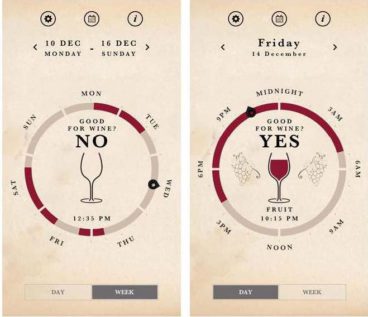

Can a bottle of wine really taste better on one day rather than the next just due to the movement of the moon? When does wine really taste best? If you love wine then the When Wine Tastes Best app, free for iPad and iPhone from Floris Books, is for you. The app allows you to quickly and easily find out the best days to drink wine, according to the biodynamic sowing and planting calendar. Find out more about the When Wine Tastes Best app here.

Featuring nearly 550 novels, stories, memoirs and journals, with LitLong: Edinburgh you can explore literary Edinburgh from the inside. Whether you’re looking to trace a path through a single book or the work of a particular author, whether you’re interested to see how any location has been written about, or whether you just want to wander through some of the many stories that have contributed to the city’s literary history, LitLong:Edinburgh can take you there. Find out more about the University of Edinburgh‘s free LitLong: Edinburgh app here.

Ed Hollis introduces his love of buildings and makes a convincing case for understanding their often untold historical lives. We also include a short extract from The Secret Lives of Buildings that highlights the continual significance of the Berlin wall to Volker Pawlowski who, ‘once upon a time’, was a construction worker in East Berlin.

The Secret Lives of Buildings: From the Parthenon to the Vegas Strip in Thirteen Stories

By Ed Hollis

Published by Portobello Books

Concrete, marble, steel, brick: little else made by human hands seems as stable, as immutable, as a building. ‘Architecture is frozen music’ we say, as if the act of building could stop the passage of time in its tracks.

But there’s nothing fixed nor timeless about a building. Even as we build them to last forever, so they outlive the people that made them and the purposes for which they were made. Give a building seventy five years or so, and all the original reasons it was created will have fallen away.

And once they do, something wonderful and strange happens to buildings. Liberated from the circumstances of their origin, they start to live extraordinary lives all of their own. It often happens over periods of time so extended we don’t see it happening – it’s a secret – but it’s one that is taking place in plain sight.

The Parthenon, now fragments of shattered marble, scattered across museums from London to Petersburg, was a temple once, dedicated by the ancient Greeks to the Goddess Athene. That much most of may know, but fewer of us remember that for many centuries in between it was a working church and a mosque.

Ancient buildings are always turned to new uses – temples into churches, churches into mosques, and mosques into museums. So, often, are the stones that made them. The marble that covers San Marco in Venice was ripped from the churches and palaces of Constantinople, and shipped across the sea in the thirteenth century.

Sometimes whole buildings make the trip. If you want to see the little house in which the baby Jesus was brought up by Mary and Joseph, there’s no point in going to Nazareth. It’s in the Italian hill town of Loreto, whence it was carried by angels in 1292. Our Lady of Loreto is, after all, the holy patroness of air travel.

Such miracles are, perhaps, easier to believe about buildings in the middle ages, than those of our own era; but the past has no monopoly on magic and idolatry. The trade in relics – real and faked – of the Berlin Wall for example, is still brisk, more than twenty years after it was torn down.

Buildings are still subjected to barbarities. The Hulme Crescents in Manchester, for example, were torn apart their its own inhabitants, flat by flat, floor by floor, in a series of drug-fuelled parties in the early 1990’s. The council who owned the estate handed them matches to set it alight in the end, and they burnt it down.

If these seem like fairy tales, then that is because buildings are like stories – handed down from one generation to the next, altered with every retelling, becoming more fantastical as each year passes. Like stories, buildings are gifts, and like gifts, if we wish to enjoy them, then we must pass them on.

The Secret Lives of Buildings is Ed Hollis’ first book. He is Reader in Design at Edinburgh College of Art at the University of Edinburgh, where he lecture and writes on interior design, uncovering, creating, and retelling the stories that buildings have to tell.

PATENT NUMBER 6076675

Volker Pawlowski lives happily ever after in Bernau, the town outside Berlin for which Bernauerstrasse is named. He is the proud owner of a building yard, a huge silver Chrysler cruiser, and US patent number 6076675, issued to him for a presentation and holding device [i] for small-format objects that has at least two transparent joinable halves that form a hollow body when fitted together into a corresponding opening in a presentation surface, such as a picture postcard. The hollow body is effectively used to contain an object which has some connection with the motif presented on the picture postcard.

Once upon a time Pawlowski was a construction worker in East Berlin, but he slipped a disc around the time when the gates of the Wall were opened. Stuck at home, he came up with the modest device that has made his fortune. Pawlowski’s invention is only half the secret of his wealth, for it is the specific motif presented on the picture postcards he sells, and the ‘small-format objects’ that have a connection with it, that lend patent 6076675 its awesome power.

Every so often, Volker Pawlowski drives his truck into Berlin and picks up sections of the Wall. Then he brings them back to his building yard, where they are unloaded and showered in bright spray-paint to make it appear as if they have been covered in graffiti. When the paint has dried, workers chip away at the slabs until there is a pile of little concrete shards on the ground. These are sorted into different sizes; and then, in accordance with patent number 6076675, they are attached to postcards of famous sections of the Berlin Wall in its heyday.

In pieces pinned to postcards, the Wall is taken back into town. Alongside old Russian army uniforms and GDR badges, it is piled up on souvenir stalls around Checkpoint Charlie, the Brandenburg Gate, and Potsdamer Platz. At the height of his business, Pawlowski was shifting between 30,000 and 40,000 postcards a year. That’s a lot of wall. ‘It’s worthless,’ he says, ‘but people seem to want it, and who am I to complain?’

[i] a presentation and holding device

The Secret Lives of Buildings: From the Parthenon to the Vegas Strip in Thirteen Stories is out now published by Portobello Books (£9.99, paperback)

www.bloodyscotland.com

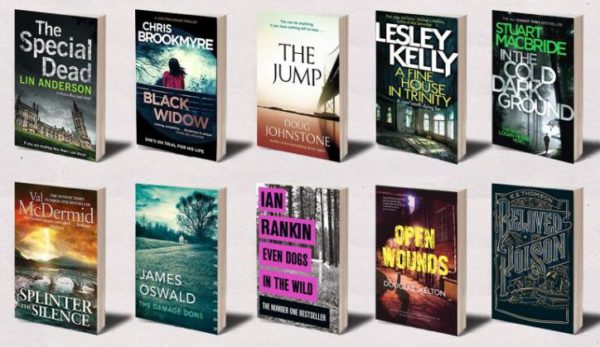

Today it was announced that the longlist for Bloody Scotland’s McIlvanney Prize, previously named the Scottish Crime Book of the Year, comprises the following books:

- The Special Dead by Lin Anderson (Pan Macmillan)

Read Lin’s interview with Books from Scotland here.

- Black Widow by Christopher Brookmyre (Little, Brown)

Read about Christopher’s Top 10 Scottish Books here.

- The Jump by Doug Johnstone (Faber)

Read about the Edinburgh setting of The Jump here.

- A Fine House in Trinity by Lesley Kelly (Sandstone Press)

- In the Cold Dark Ground by Stuart MacBride (Harper Collins)

- Splinter the Silence by Val McDermid (Little, Brown)

- The Damage Done by James Oswald (Michael Joseph)

- Even Dogs in the Wild by Ian Rankin (Orion)

- Open Wounds by Douglas Skelton (Luath Press)

- Beloved Poison by E.S. Thomson (Little, Brown)

The McIlvanney Prize recognises excellence in Scottish crime writing and it is named in tribute to the great Scottish author William McIlvanney. The longlist has been chosen by an independent panel of readers, and the final judging panel consists of journalist Lee Randall, award-winning librarian Stewart Bain, and former editor of The Scotsman and The Times Scotland Magnus Linklater. Hugh McIlvanney OBE, the brother of William McIlvanney, will present the award.

The winner’s prize includes £1000 and nationwide promotion of their book in Waterstones. For more information visit Bloody Scotland’s website.

The Bloody Scotland festival takes place from 9-11 September 2016. You can browse the festival brochure below.

Do you have a favourite book from this longlist? Let us know via our Twitter and Facebook pages.

Authors Neil Baxter and Fiona Sinclair reveal the background to their recent Scotstyle book, published by the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland, which maps and celebrates the 100 best buildings in Scotland from 1916 onwards. Scotstyle demonstrates a rich history of creativity, pride, and ambition and shows that Scottish architecture undoubtedly competes on the world stage.

Extract from Scotstyle: 100 Years of Scottish Architecture (1916-2015)

By Neil Baxter and Fiona Sinclair

Published by RIAS

Scotstyle is both an exhibition (three versions touring Scotland in a ‘pimped up’ 1979 VW Camper Van) and a 240 page, full colour, publication. Both feature 100 buildings nominated by the public with the final selection by an expert panel of ten who, in turn, became the authors of the book (ten buildings each). The whole endeavour is a headline event of the Festival of Architecture 2016, celebrating the centenary of The Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland (RIAS).

The following, adapted from the book’s preface, reflects on the previous Scotstyle when again the general public had nominated their favourite buildings, on that occasion from the previous 150 years. One of the editors of the new book, Fiona Sinclair, wrote the 1984 book while her fellow editor, Neil Baxter, now RIAS Secretary, sat on the selection panel.

The original Scotstyle exhibition and publication in 1984 made curious bedfellows out of farm steadings and glasshouses; churches and railway stations; lighthouses and mausolea. In the 1984 list the Arts and Crafts-inspired, stone-built, slate-roofed East Suffolk Road Halls of Residence (1916) lay sandwiched between two utilitarian examples of early in-situ concrete construction (Weir’s Administration Building in Cathcart, and the long-gone Crosslee Cordite Factory near Houston). This time around, it more happily rubs shoulders with the romantic Cour House in Argyll and the idiosyncratic Dutch Village in the Fife countryside.

03 – Dutch Village © Jamie Howden

In 1984, the selection was book-ended (quite literally) by two great public institutions, William Playfair’s Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh (1834), and the Burrell Collection in Glasgow’s Pollok Park (1983). Though publicly accessible both reinforce the notion that “architecture” is experienced at arm’s length. Now, in this year of centenary celebrations, the bookends are instead two housing projects of clear architectural and social ambition: urban exemplars offering an inclusive and exciting future.

Colin McWilliam, who wrote the preface to the original book, found the 1984 survey relatively evenly distributed across the country. He remarked that, “outside the big towns Strathclyde (21) and Tayside (12) are well ahead, leaving the other regions in single figures and Dumfries and Galloway nowhere.” Happily, this most southerly of regions is now better represented. However the real success story is the emergence of significant new buildings on the islands, Tiree, Skye, Orkney and Bute.

Of the original 145 buildings illustrated in Scotstyle, 56 were eligible for reinclusion, although in the event, only 37 have made a re-appearance. The pre-war decades have seen little change – few architects can match the end-of-career conviction of Robert Lorimer, JJ Burnet and James Miller (and few the creative energy of a young Jack Coia or Basil Spence) – but from the late 1930s and early 40s emerge two hidden gems in Aberdeen. The succeeding decade revealed the inexplicable omission first time around of the National Library of Scotland.

39 – National Library of Scotland © Grant Bulloch

In large part down to its relatively recent urban renaissance (not to mention the effect of the 1999 City of Architecture and the 2014 Commonwealth Games), Glasgow now chalks up an impressive 36 entries (only one less than in 1984), whereas Edinburgh is represented by a significantly reduced 19 projects. What it lacks in numbers, however, the Capital more than makes up for in being represented by two big-hitters, the National Museum of Scotland (1998) and the Scottish Parliament (2004).

Tourism, and the promotion of the nation’s attractions, emerges as an important initiative. And while the 1875 Kibble Palace glasshouse in Glasgow has fallen off the list, the equally elegant John Hope Gateway (2009) in Edinburgh’s Royal Botanic Gardens has nicely filled its place, with the popular Princes Square on Buchanan Street (1987) similarly occupying the spot vacated by Jenners’ Store on Princes Street (1895).

A one-man castle built of in-situ concrete, sand and shell on Loch Inver (1950) lends intrigue to the 2016 list. There are fewer churches (now, just six, the most recent opened in 2012), and instead there are cathedrals to the newspaper industry (1936), hydroelectric power (1934), and tobacco (1949). There are now houses (and a church, and parliament) on whose roofs turf and sedum have been planted. With the early 1990s came a resurgence in the use of public sculpture. The use of contemporary sculpture in the remarkable urban block, the Italian Centre in Glasgow (1991), has yet to be bettered.

76 – Italian Centre © Keith Hunter

But of all the building types represented – housing, industry, commerce, education, research, arts, leisure and worship – it is healthcare that has consistently encouraged architects to raise their game. The first UK hospital built after the Second World War at Vale of Leven (1951) is no longer cutting-edge, but the country’s Maggie’s Centres are consistently exceptional, with two of the most sublime represented.

Of course, an analysis of 100 years of Scottish architecture throws up changes in politics, patronage and production. Despite a strong showing from Aberdeen and Argyll, this selection features less indigenous granite and sandstone than it does homegrown timber, imported brick and copper and there is an emphasis on recycled (and recyclable) materials, sustainability and sophisticated services.

Of course the Scotland that our architects continue to shape is much changed over the last century. Public patronage has been fizzed up with lottery funding, enlivening our arts and cultural built landscape. However, no change has been more significant that the devolved, confident, governance following the Scotland Act of 1998. The Parliament building, though more ‘marmite’ than any other of recent times, is deservedly here.

The Scottish Parliament was recognised in one of the first RIAS Andrew Doolan Best Building in Scotland Awards. The RIAS has also, more recently, launched its own national awards for Scotland. As well as bestowing laurels on an annual ‘top ten’ (or thereabouts) the RIAS Awards also recognise the increasingly ingenious use of timber, energy efficiency, sustainability and conservation best practice, emerging architects and perhaps, most significantly, the crucial role of the client in any successful work of architecture. There are 100 buildings in this book, that’s 100 inspired clients encouraging and supporting their architects to excel.

Fiona Sinclair FRIAS and Neil Baxter Hon FRIAS

Scotstyle is out now published by RIAS (£25, paperback)

This excerpt by Micky Piller delves into the wonderfully idiosyncratic and original world of Dutch artist Maurits Cornelis Escher and provides an insightful overview of his life and multifaceted work.

Extract from The Amazing World of M.C. Escher

Published by National Galleries of Scotland

Maurits Cornelis Escher 1898-1972: A Singular Artist

By Micky Piller

The world-famous prints of Maurits Cornelis Escher were a familiar feature of the childhood and adolescence of many people born after 1950. His works can still be seen in restaurants, teenagers’ bedrooms, doctors’ waiting rooms and classrooms. Yet at the time, the art world was slow to appreciate his woodcuts and lithographs. There was a tendency to regard his prints as technical novelties primarily designed to illustrate mathematical problems.

A couple of years before the period in which Escher’s art came to be admired by the general public, abstract art had been enthusiastically welcomed as the New Art that broke with the ‘mistakes’ of the past. The idea gradually took hold that if, contrary to the spirit of the times, an artist persisted in an allegiance to figurativism, they were deliberately placing themselves outside contemporary art. Escher chose to make prints when everyone believed that art consisted of the broad, painted gesture. And that was seen as old-fashioned. Yet as early as 1951, The Studio, Time and Life magazines all published stories on the artist, introducing him to a US audience. In 1961 E.H. Gombrich wrote about his work – to Escher’s great satisfaction.

There was thus an enormous gap between the recognition Escher received from the public and the lack of appreciation displayed by official bodies. His first large retrospective at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague did not take place until he was seventy years old. By then he had sold over 650 prints of a single woodcut: Day and Night, 1938.

Escher knew exactly why his art appealed to the layman:

My subjects are […] often playful. I cannot help mocking all our unwavering certainties. It is, for example, great fun deliberately to confuse two and three dimensions, the plane and space, or to poke fun at gravity.

Are you sure that a floor cannot also be a ceiling? Are you absolutely certain that you go up when you walk up a staircase? Can you be definite that it is impossible to have your cake and eat it?

I ask these seemingly crazy questions first of all of myself (for I am my own first viewer) and then of others who are so good as to come and see my work. It’s pleasing to realise that quite a few people enjoy this sort of playfulness and that they are not afraid to look at the relative nature of rock-hard reality.

Escher made these remarks in 1965 on being awarded a Dutch cultural prize. The quote reveals character traits that can also be seen in his work: humour and a predilection for the unexpected. And at the age of sixty-seven he was still a cheerfully unconventional thinker.

From the mid-1950s onwards Escher was able to live on the income from his work. He was flattered by the many requests he received for lectures and prints, but at the same time complained that he hadn’t enough time to work on new ideas. If a request came for a print that had sold out, he made new copies. He used a small egg spoon made of bone to print woodcuts in his workshop at home, a procedure that demanded time, concentration and peace and quiet. For mezzotints he used a small printing press. He took his litho stones to a professional printer, but always oversaw the whole printing process.

That Escher led an orderly, structured life is clear from his own remarks and those of his eldest son. He spent hours in his workshop and went for a daily walk in the afternoons. Mauk – as Escher was known to friends and family – was often exasperated by visitors who wanted to know the deeper significance of his work: he thought such questions were downright nonsense. He didn’t accede to every request. Mick Jagger wrote him a letter, starting ‘Dear Maurits’ and asking for a print to grace the cover of the Rolling Stones’ new LP. ‘Who is this Jagger person?’ Escher apparently grumbled. It wasn’t such a strange request: there were already LP covers featuring his work. But Escher was by no means unworldly. He followed international political developments and, unlike many Dutch people of his generation, opposed the war in Vietnam.

Escher wanted to portray a clear-cut logic (which he called ‘order’) in his work, an order which he believed underlay the chaos of daily life. His prints can be divided into two large groups: in the first eternity, or time, plays a major role; in the second infinity, or space. Sometimes the two are interwoven and equally important. But more than anything, the effort to inspire amazement was his driving force. As he wrote to his friend Bruno Ernst in 1956: ‘Maybe I focus exclusively on the element of wonder, and therefore I also try to evoke only a sense of wonder in my viewers.’

Books from Scotland is delighted to show you some spreads from The Amazing World of M.C. Escher below.

© National Galleries of Scotland

© National Galleries of Scotland

© National Galleries of Scotland

The Amazing World of M.C. Escher is out now published by National Galleries of Scotland (£19.95, paperback)

This fascinating photographic article goes behind the scenes of the making of the iconic Kelpies showing how Andy Scott, the sculptor, saw the project evolve from drawings and steel panels to the magnificent sculpture known around the world today.

Extract from The Kelpies: Making the World’s Largest Equine Sculptures

By Andy Scott

Published by Freight Books

“The Kelpies came to life as the specific recognisable features were added. When the eyes and ears were painstakingly raised and bolted onto the colossal heads, the structures started to ‘speak’ to their audience. They transformed from abstract steel assemblies into living equine giants.”

– Andy Scott

The Kelpies: Making the World’s Largest Equine Sculptures is out now published by Freight Books (£25, hardback)

The modernist ruin of St Peter’s College has sat on a wooded hilltop above the Scottish village of Cardross for more than three decades and has gained cult-like status among architects, preservationists and artists today. Books from Scotland provides a preview, including impressive photography, of what you can expect when St Peter’s, Cardross: Birth, Death and Renewal is published later this year.

The modernist ruin of St Peter’s College has sat on a wooded hilltop above the village of Cardross for more than three decades. Over that time, with altars crumbling, graffiti snaking across its walls and nature reclaiming its concrete, it has gained a mythical, cult-like status among architects, preservationists and artists. A new book to be published in November by architectural historian Diane Watters – St Peter’s, Cardross: Birth, Death and Renewal – will trace the story of an architectural failure which morphed into a tragic modernist myth.

© NVA

St Peter’s only fulfilled its original role as a seminary for 14 years, from 1966 to 1979. As its uncompromising design gave way to prolonged construction and problematic upkeep, the Catholic Church reassessed the role of seminaries, resolving to embed trainee priests not in seclusion, but in communities. Although briefly repurposed as a drug rehabilitation centre, the building was soon abandoned to decay and vandalism.

© NVA

Ever since, people have argued and puzzled over the future and importance of St Peter’s. It has been called both Scotland’s best and worst twentieth century building. In 1992, it was listed category A. One of its architects suggested the idea of ‘everything being stripped away except the concrete itself – a purely romantic conception of the building as beautiful ruin’. And now in 2016, St Peter’s is undergoing renewal as a cultural space through the work of the arts charity NVA.

© NVA

Author Diane Watters will look at the history of a structure that emerged out of an innovative phase of post-war Catholic churchbuilding. For some, the story of St Peter’s is a story of unappreciated architects betrayed by an unloving client, and abandoned by an uncaring society. For others, the real building became lost in a media-led narrative of crumbling modernist grandeur. This is a historian’s account of the true story of St Peter’s College: an exploration of how one of Scotland’s most singular buildings became one its most troubled – and most celebrated.

© NVA

Released on the 50th anniversary of St Peter’s original opening, this is the first major history of the building. Published by Historic Environment Scotland in partnership with NVA and the Glasgow School of Art, it will feature large amounts of previously unpublished imagery, including original plans and photographs, and views of the ‘Hinterland’ immersive arts event which took place at Cardross in March 2016.

© Glasgow School of Art

Author

Diane M Watters is an architectural historian at Historic Environment Scotland and teaches at the University of Edinburgh. A specialist in nineteenth and twentieth century architecture and conservation in Scotland, she has undertaken a succession of research based publications and is currently researching the history of Edinburgh’s school architecture.

Publisher

Historic Environment Scotland is the lead public body for Scotland’s historic environment: a charity dedicated to the advancement of heritage, culture, education and environmental protection. It cares for over 300 properties across Scotland, actively records and interprets the nation’s past, and holds the national record of architecture, archaeology and industry, a collection of over 5 million drawings, prints, maps, manuscripts and photographs. Its books, aim to tell the stories of Scotland – exploring ideas and starting conversations about the past, present and future of the nation’s history and heritage.

St Peter’s, Cardross: Birth, Death and Renewal will be published in November 2016 by Historic Environment Scotland (£30, hardback). All photographs included here are taken from the book.

This extract highlights how George Wyllie’s bold artistry connected him to both Scotland and to the wider international arena. Through authors Wyllie and Patience we are given fascinating insight into the political and cultural context of his 1980s sculptures ‘A Robin in a Cage’ and ‘Berlin Burd’.

Extract from Arrivals and Sailings: The Making of George Wyllie

By Louise Wyllie & Jan Patience

Published by Polygon

A Way with the Birds

The liberation George felt at being able to pursue his art on a full-time basis led him to make connections and form firm friendships with many like-minded souls. He may have been in his sixties, but he had the energy of a man half his age. His gregarious nature helped, of course, not to mention his ability to get on with people of all ages from all sorts of backgrounds and cultures. In 1981, as well as his work with Beuys in Edinburgh, he exhibited with Dawson Murray at the Stirling Smith Museum and Art Gallery in a show called Counterbalance. For this thoughtful exhibition, George made sculpture in response to Dawson’s paintings and vice versa. Years later, in 1999, George and Dawson revisited this idea of responding to one another’s work with a monumental installation in Glasgow’s brand new Buchanan Galleries shopping centre. In this work, Divine Rythm, George suspended a 400kg stone on a stainless-steel beam in front of Dawson’s painting of the earth’s strata. It was underpinned by a quotation from Hugh MacDiarmid’s poem ‘On a Raised Beach’.

In 1981, George also had another solo exhibition at Strathclyde University’s Collins Gallery called A Way with the Birds, which travelled on to London’s Serpentine Gallery, where it was a major attraction during the summer months. This was George’s first big exhibition in London and it attracted press attention on an unparalleled scale, especially outside Scotland. This included an appearance on the BBC’s popular early evening current affairs programme Nationwide. He started to receive fan letters and he made sure he answered each and every one of them. The exhibition’s title was a nod to George’s continuing fascination with making birds from steel – or ‘burds’, as he referred to them, in the Scots vernacular. A Way with the Birds featured several portrayals of birds, including A Robin in a Cage, a simple yet poignant little steel robin – with painted red breast – trapped in a cage.

A Robin in a Cage by Wyllie

George and Daphne always used to wonder if his attraction to creating birds or featuring them in his work had something to do with Andy’s influence from beyond the grave. One of the most memorable feathered friends George made was his Berlin Burd. This gangly big bird was commissioned in 1988 by the City of Glasgow as part of the European Capital of Culture celebrations that year in Berlin. George sited it at the Berlin Wall at Reinickendorf where it peered over into what was then Communist East Berlin. He invited schoolchildren in West Berlin to participate by making their own birds for display alongside his own five-metre tall bird. Ironically, or perhaps prophetically, the wall came tumbling down just two months after George’s Burd was planted on its lofty vantage point. The Berlin Burd combined aneducational project with street theatre and art-with-a-message and George revelled in its surrealism. The planning powers-that-be in West Berlin were reluctant to allow him to install the Berlin Burd initially, but he reminded them that ‘ein Vogel ist kein Stein’ or ‘a bird is not a stone’ and that students would not be throwing it in demonstrations. He later wrote about the experience: ‘I think the bird looking over the wall in Berlin was quite good. I said to this German, “This wall’s a bit stupid really, because there’s Germans on this side, Germans on that side, and we’re all really together, except this wall’s keeping us apart. It’s an absurdity.” “You’re right,” he said. “It takes one absurdity to question another.”’

Berlin Burd by Wyllie

One of the biggest hits at George’s A Way with the Birds exhibition was the Heath Robinson-esque All British Slap and Tickle Machine, a kooky contraption with a recycled bicycle seat for people to sit on, operating pedals, a welter of floppy leather hands and a somewhat risqué tickling finger. George told the media this machine was designed to prevent the loss of ‘a sense of joy in things’ during the Thatcher years. George’s gift for making people laugh brought all sorts of visitors into galleries who had never visited one before. The Serpentine Gallery staff were amazed at the laughter ringing through the space during the exhibition’s run in London. George knew, from his lifelong fascination with performance, that humour was a way to permeate people’s hearts and minds.

Around this time, George met Barbara Grigor, a charismatic film and television producer as well as an art lover, who had set up an organisation called the Landmark Sculpture Trust, later the Scottish Sculpture Trust. At that point, together with her husband Murray, Barbara ran a film company called Viz. George didn’t meet Murray until a few years later, but all three would go on to enjoy a fruitful and life-enhancing friendship. Murray recalls his late wife (Barbara died in 1994 at the age of just fifty), coming home from George’s first solo show at the Collins Gallery in 1976 ‘completely bowled over by his work and his wry wit’. According to Murray, ‘They really got on so well because Barbara shared George’s attitude to the mandarins of Scottish art who seemed always to be obsessed with reshowing London exhibitions in Scotland. “Pioneering Old Hat,” as Barbara called it. She invited George onto the board of the Scottish Sculpture Trust, which greatly livened up meetings.’

George also got to know jazz musician, art critic and fellow lover of Surrealism George Melly. The two men shared many interests and met up whenever they could. In September 1982, Melly sent George a letter headed ‘Dear George the Pataphysician’, which alluded to their shared passion for the work of surrealist French writer and philosopher Alfred Jarry. Jarry was the man responsible for coining the term ‘pataphysics’, meaning ‘the science of imaginary solutions’. Referring to having just read George’s A Day Down a Goldmine script, Melly writes: ‘You’re right about usury of course. You can’t eat it, make love to it or take it with you and yet it runs, very badly, the world. All it’s good for is to spend & I’m very proficient at that, hence the squirrels’ wheel.’

Arrivals and Sailings: The Making of George Wyllie is out now published by Polygon (£25, hardback)

This extract from Site Works by Robert Davidson takes the reader to the building site to shed light on what really goes on in construction. Site Works is the story of the men and their work engineering a huge drainage project in northern Scotland, which sees the men toil through the daylight hours and into the night, enduring hardship and conflict.

Extract from Site Works

By Robert Davidson

Published by Sandstone Press

It’s the Clearances all over again

Last to go would be the towering batching plant with its mounds of aggregate and sand and bags of cement. An industrial relic it overlooked the men’s hut like a strange Gothic watchtower. Ikey saw it as having religious significance, the great mixer and maker, an alchemist device that turned loose materials into unyielding concrete. Standing by the Plant Contractor’s van he observed its outline against the blue sky and then lowered his gaze to the the wooden cludge that would be the last structure to be moved up the road.

Willie Sweeney was also outlined against the sky. Balanced on the men’s hut, last to descend, he kicked at the roofing felt where it had come loose at the crest.

‘What’s it like,’ Cammy shouted up.

‘It’s a hundred years old, bullet riddled and torn. This must be the hut Custer hid in when the Apaches were closing in.’

‘Sioux!’ Ikey shouted up. ‘They were Lakota Sioux, Mr Sweeney, and it was the other way round. Custer attacked them.’

Willie pointed at him with his hammer.

‘Did you read that in a book? You’re spending too much time in that cludge.’

‘Lakota,’ Ikey repeated.

‘I wouldn’t argue with Willie,’ Jimmy English said, exiting the hut.

‘I was a farrier in the 7th back then,’ Willie said. ‘They busted me after the massacre, said the whole thing turned on a loose horseshoe, but they were covering up for Reno. He was one of them in ways I could never be.’

‘Is it usable,’ Jimmy asked, impatient, ‘the felt?’

‘Nope, it’s had it,’ Willie said. ‘No wonder the hut lets in.’

Willie crouched on his hunkers and took the claw of his hammer to the roof nails, drawing and releasing them and letting them slide down and fall to the ground, pulling the felt away from the crest like a blanket, dropping it also to the ground.

Stores had been the first hut down. Too far gone to be repaired and reused Cammy had broken it up and started a fire with the rotted roof joists. He dragged the first sheet of felt over and threw it on to blacken and curl and take light. As it shrivelled he pushed the edges into the fire’s heart with his boot.

‘More costs for Swannie,’ he said. ‘He won’t like it.’

‘And he’d avoid replacing it if he could,’ Willie said. ‘We’re doing the Lochdon troops a favour.’

‘Whoever they are,’ Cammy said.

Squatting precariously at the end of the roof Willie leaned over and prised at the nails that kept the remaining felt in place. ‘Who is staying and who is going, that is the question.’

‘Everybody’s staying,’ Jimmy said. ‘Lochdon is a bigger job, more pipelines, three Pumping Stations, four Tanks. I’m seeing Swannie about rates when the light goes. We’ll get the work if we’re not too greedy. Start maybe next week.’

‘The sooner the better,’ Willie said, ‘because there’s no money in this.’

‘Perzackly!’

A flat lorry bounced in off the A9 with Derek the Steelfixer at the wheel. By now the joiners had the mess hut, the last hut, down and stacked. It remained to get the panels of all three huts onto the back of the lorry, tied safely down and carried up the road to Lochdon. Two journeys Jimmy reckoned.

Willie shielded his eyes with his hand and made a great play of peering under the lorry.

‘Where’s Trots, Derek? Shouldn’t he be driving this thing?’

‘He says it’s not his job and won’t be until he’s paid the rate.’

‘So it’s yours?’

‘There’s no money in Lochdon till this is done. The best thing I can do is move the job along and take whatever rate Swannie will pay. Give me a hand with these panels.’

Willie and Cammy each took a corner of the first wall panel and powerful Derek took the other side by himself. When Jimmy moved across to help he shook his head. The three men threw the panels one by one on the back of the lorry.

Where the huts had stood the ground was marked with the rectangle of their floor shapes. The compound fence hung from its posts and the gate swung on its hinges. Where Stores had been was littered with oil drums and loose bolts and spilled gravel. It was a place where life had once been but was no more.

Jimmy came over and stood beside Ikey.

‘The place is like a battlefield,’ he said.

‘The Little Big Horn,’ said Willie.

‘No,’ Ikey said, ‘the Clearances. It’s like the Highland Clearances all over again.’

‘Did you know it was Jimmie burned out Strathnaver?’ Willie said. ‘He’s changed since then. The love of a good woman saved him.’

Cammy’s fire crackled and sparked and grew as he scoured the area for odd pieces of scrap timber and threw them on.

‘Good women,’ Willie sighed. ‘Whatever happened to them?’

Panels secured on the back of the lorry Derek fired the engine and drove out, heading back north to Lochdon. Jimmy climbed into his car and followed leaving Willie and Cammy to tend the fire, to make sure everything that could burn was consumed. Later in the day, maybe tomorrow, Conn would dig a hole and doze in the waste and bury it.

Ikey superstitiously tapped the wooden side of his pride and joy, the cludge, as if it contained the spirit of the work, the Great Manitou of Civil Engineering, as some said all cludgies did, and took a walk to the Settlement Tanks where Conn’s jib stood tall above Tank Two.

The double chain hung taut with the load of an aluminium scum trap that he swung in slow instalments closer to the tank wall. Below him on the concrete base the Plant Contractor’s foreman opened and clenched his fist slowly and slower still as the dead weight drew closer to the wall. Abruptly he raised both arms and brought the movement to a halt.

Conn locked the jib, opened his cabin door and spat out the remains of his roll-up.

‘Yo ho, Ikey.’

With the scum trap hovering gravity neutral by the wall two fitters moved in to sit by either side. They pushed and eased it into exact position and shoved the holding bolts through and into the pockets that had been boxed out before the pour. As they tightened with their spanners the weight of the trap was transferred and the chains became slack.

‘You moving up the road to Lochdon?’ Conn asked.

‘Mr Lammerton has yet to decide, sir.’

‘Or if he’s decided he hasn’t said. That’s how these people work.’

‘Nil carborundum, Mr Conn.’

‘Bullseye, wee man, I hope they take you along. You deserve it.’

‘Thinking of movement, Mr Conn.’

‘That’s Conn, just Conn.’

Ikey struggled against saying to Conn what he wanted to say to Willie but eventually it came out.

‘Did you know there were Highlanders at the Little Big Horn?’

Conn eyed him warily.

‘I didn’t. Which side?’

‘With the Long Knives.’

‘Joined up? Joined the Long Knives, the White Eyes, Roundeyes, Yellow Legs, Red Coats? Playing the pipes as the arrows came thudding in? Gathering in a circle at the end and singing their Gaelic psalms?’

‘Yes sir.’

‘We were the same in Kerry with the Roundheads, on the wrong side as ever. In the end they always win. Did you know?’

‘I did, sir, and for better or worse we join them. They would have been cleared from up by. Strathnaver, sir, or the likes.’

Ikey stood talking to Conn and the plant operatives as the light of day began its departure and Conn switched on the crane’s one headlight, watched while the troops leaned dangerously over the Tank to tighten the bolts, as they levelled the spill-over rim to ‘near enough’.

Feeling the call of nature he wandered back to where the compound had been. Inside the cludge he hung up his jacket, took The Brothers Karamazov from his pocket and sat to ease himself through the last bowel movement of the Ness and Struie Drainage Project with the last sustained read.

The boys had killed their father. Well, he understood, although the reading of C G Jung and the living of his life had taught him all he needed to know about the slaying of the father and its futility.

When he came out the sun was gone. All was dark and there was barely a star in the sky. Willie and Cammy had been joined by Derek the Steelfixer, returned for the cludge when they had broken it down. The three were silhouetted against the fire that overtopped them by twice their own height and might have been made for the burning of a witch or some other unredeemed soul bound for hell.

In the darkness of daytime night the temperature dropped and a sparkling frost formed on the ground and on the site’s detritus and there hardened. Ikey joined the three others by the fire and felt its heat and its call to the primitive and wondered about guilt, sin, revenge, justice and what they were. Damned little, he thought, against the great round of history’s repetitions and humanity perpetually breaking up and moving on.

Site Works is out now published by Sandstone Press (£8.99, paperback)

James Taylor presents an introduction to history and context surrounding the instantly recognisable and highly popular posters used in the UK for various propaganda purposes during World War I and II. We also showcase three Scottish poster designs.

Extract from Your Country Needs You: The Secret History of the Propaganda Poster

By James Taylor

Published by Saraband Books

Introduction

This book coincides with the global centenary commemorations of World War I and it reveals, for the first time, the true story and full extent of the vital role played by the art and design of recruitment posters in the war – not just in the UK, but around the world in Europe, Australia, Canada, India, South Africa and the USA. The posters were particularly important during the initial stages of the conflict, when they were devised as part of a wide-ranging campaign to recruit the millions of men needed for frontline action. Today, one poster above all others is recollected by name: Your Country Needs YOU. It is a poster that we all feel we know so well, but do we really?

There is no doubting the enduring influence of the striking, arm-stretching and finger-pointing cartoon of Lord Kitchener first created by the British-born commercial artist Alfred Leete as the cover for London Opinion magazine on 5th September 1914. The original artwork for this cartoon was acquired by the Imperial War Museum in 1917 and has ever since been mistakenly assimilated into the minds of millions as being one and the same as an imagined recruitment poster bearing the same slogan with mass appeal. But was this poster really as popular as people now think? There is certainly evidence that the image of the cartoon – as opposed to the poster – was very popular. For example, London Opinion, which sold more than a quarter of a million copies a week in the early months of the war, issued reproductions of the cartoon on fine art paper. Postcards bearing the image are also thought to have appeared in order to aid recruitment.

The popularity and success of the Kitchener cartoon lies in its combination of an easy-to remember slogan and a simplistic and adaptable design that derived from commercial advertising pre-dating the war. However, there is no conclusive evidence to support the claims made by many historians that a poster version of Leete’s cartoon was the most popular and effective official design of the war. A list of the official posters in order of popularity has been compiled here and Leete is conspicuous by his absence. Leete’s poster was published privately and no records survive of the precise numbers printed.

As well as examining the story of Leete’s Kitchener image, this book delves into the remarkable life and achievements of Leete himself, and explores the influence of cartoonist contemporaries such as Bruce Bairnsfather (creator of ‘Old Bill’) and John Hassall (Skegness Is So Bracing), alongside the colourful and controversial world of the brilliant American artist, cartoonist and illustrator James Montgomery Flagg. In 1917, Flagg adapted Leete’s design for his celebrated poster depicting Uncle Sam. Entitled I Want YOU For U.S. Army, it is arguably the most familiar image in the USA after the ‘Stars and Stripes’ national flag.

The designs of both Leete and Flagg still resonate powerfully today and have been used for many diverse campaigns for economic, educational, financial, military and political purposes during World War II and in the following decades up to the present day. They have become design icons.

© King’s College London

© King’s College London

King’s College London

Your Country Needs You: The Secret History of the Propaganda Poster is out now published by Saraband Books (£16.99, hardback)

In this interview author Lari Don talks to Liam Davison about the writing process, what inspires her, and her journey to becoming a best-selling children’s author of books including The Secret of the Kelpie. We also highlight the fun and interactive Kelpie Map of Scotland which you can use to see how the story of the mythical kelpie varies around the country.

Lari Don, author of books including the award-winning Fabled Beasts Chronicles series and the hotly anticipated forthcoming Spellchasers trilogy, has always been a writer – she was making books before she could even write.

“My mum used to come into my bedroom every night and read me a book. After she put out the light and closed the door, I would sneak out of the bed, put the light back on, and get a piece of paper. I would fold it up until it looked like it had that function of the book, the opening pages, and I wrote stories in those books.”

But more than a writer, she has always been a sharer of stories – the carefully scribbled piece of paper would be slipped under her mother’s bedroom door late at night. So after a career in politics and journalism, it is little wonder that Lari is now a full-time writer and storyteller.

Lari’s latest book is a retelling of the classic Scottish myth of the Kelpie, a beautiful water horse that would lure children to the lochside and try to drown them.

But why is writing so important to Lari?

“I think in stories. I have had other jobs, but they’ve always been about words and they have always been about stories. Working in politics is about trying to make people see a ‘happy ever after’, and to make people follow the same narrative you are, to take people on a journey along with you. So I’ve always played with stories. My previous jobs were factual, so you had to gather the facts. Now I just get to make it up, and that’s great!”

Some writers work best with a clearly defined plan for their books. Others, like Lari, take a spark of inspiration and see where it takes them.

“That was the excitement of opening a book as a child. For me as a writer, the excitement is in having an idea and not knowing what’s going to happen with it. I think I have at least a dozen novel ideas on my wall – it’s going to take me years!

“I don’t plan my novels. Having an idea and then writing it has all that excitement bound up in for the months that I’m writing. I don’t know how it’s going to end! I don’t know what’s going to happen. I don’t know where I’m going to take it.”

But isn’t that a little risky?

“It is quite terrifying, particularly if you say to an editor, ‘hey, I’ve got a great idea… I’ll give it to you in a year or six months’, or whatever, and you don’t actually know what you are writing. You’ve just agreed to write a book and you don’t know whether it will work. You don’t know what will happen in the end. And it’s absolutely terrifying.”

When she sits down to write, at a computer surrounded by notes and ideas for other stories, Lari says that she tries to focus solely on the novel at hand.

“What’s interesting is that when I am working on a novel I tend to be very, very locked inside that novel, and don’t to have many other ideas for books. But when I am in an editorial phase, I find new ideas. I find editing and redrafting and rewriting books almost uses a different part of my brain, and that’s when I have the next ideas.”

How important is the editing and redrafting process?

“Everything I have ever written is too long, and I would be embarrassed to show it to anybody. So I go back and I slice out scenes I didn’t need, maybe tweak things at the beginning so it fits. I distill it down to what I actually need it to say to the reader. I love writing but my books would be rubbish if I didn’t also edit.

“But equally, they would be rubbish if the editor didn’t edit it after that… if an editor didn’t ask me difficult questions that prompt me to step back and see what I’ve written.”

Whereas the Fabled Beasts Chronicles, starting with First Aid for Fairies, are original novels, Lari’s new book The Secret of the Kelpie is a retelling of a classic Scottish Kelpie myth, and writing this necessitates a different approach.

“If I’m retelling a traditional tale I know how it ends. Or I know roughly how it ends! I’m not slavish to sticking to the actual traditional tale, and will change and tweak… it’s more of a craft than an art, I think.”

That craft is evident in The Secret of the Kelpie, which is at once familiar and new. Some of the Kelpie myths can be quite shocking or scary, with children being maimed or worse by the beautiful white horse. In Lari’s new version, some quick thinking by the youngest child, Flora, saves her impulsive siblings.

“The Secret of the Kelpie isn’t a retelling of a story that exists. There are lots of lots of little snippets of folklore about Kelpies, so I read lots of books, gathering lots of different bits of Kelpie lore, from lots of different bits of Scotland. I created a story out what I thought were the best and most exciting, and honestly the most child-friendly, bits.”

The Secret of the Kelpie is just one of the many myths and legends that Lari has written about, yet Lari didn’t plan to be a writer and collector of traditional folklore.

“I hadn’t expected to be. I’m a fiction writer, a novelist, and I didn’t expect to do that. I always thought I would make up my own stuff. But when I was approached [by Floris Books, her publisher], I realised that the stories that inspired the novels that I write, they were already in my head. I realised that I wanted to share those stories that inspire me, as much as I wanted to share the fiction they inspire.”

Lari Don is a registered Storyteller at the Scottish Storytelling Centre, but admits that she is a writer first, and storyteller second.

“I was a writer before I became a storyteller, when I had children I started telling them stories. And I thought this is something I could learn to do, professionally. I learnt how to do it for two reasons.

“I genuinely love it, these are stories I am passionate about, I have to share them. But also, honestly, because I could see it had advantages for somebody who wanted to write. It has helped me learn how I love to tell stories.

“For me, a key to telling a story is finding the heart of it, finding the bit that I really want to share. And it isn’t about memorising a story, it’s about sharing it. When I’m storytelling, for me the pinnacle of success would be a child going home and telling that story to somebody else.”

Finding the heart of the story, as Lari puts it, is key to why she has turned to the myth of the Kelpie for the new picture book, The Secret of the Kelpie. There are lots of considerations when turning a favourite myth into a book to be read by children.

“I love lots of traditional tales, but not all of them are suitable for younger kids, or at least, not suitable without having their heart ripped out, which I don’t want to do. When I discussed potential stories for this strand with my editor, this story of the Kelpie seemed perfect. Partly because this imprint is called ‘Kelpies’. Also I’m working with Kelpie magic in the trilogy of novels I’m writing just now.

“But I had to give serious consideration to one element of the story – I had to put the children in danger, but ultimately not actually drown or devour any of them. So, getting that level of tension right was a discussion I had very early on with my wonderful editor. Making a story exciting and magical and a bit risky, without actually going so far that it terrifies the readers, requires a bit of thought. I wanted to be true to the Kelpie lore, which is about a genuinely scary and dangerous beast, but also respectful of my readers.”

Pitching a story to children means getting the balance right. Lari has written for children of all ages, from pre-school picture books like The Big Bottom Hunt, adventure novels for eight to twelve year olds, and a novel for teenagers, Mind Blind.

Lari delights in the risk and dangers she puts her characters through in the Fabled Beasts Chronicles:

“I will hurt them… the fairy is so easy to injure, it’s wonderful! I do terrible things to her. There will be danger, they will be in pain, they will have terrible things happen to them. I want the readers worried about the characters and identifying them, and to do that I have to put the characters in peril. But whatever I put them through on the journey, by the end, everyone is (almost) fine. I always leave the readers and characters with a bit of hope and a bit of happiness.”

But things are different for teenage novel Mind Blind.

“Honestly, no holds barred! People died in it, children died in this book… This is a question that popped into my head as I was writing it. It became very clear very quickly this was not a book I could read to Primary 4s or 5s. It had to be for older.”

For a picture book like The Secret of the Kelpie, the illustrations can help build just the right amount of tension. Lari is full of praise for the pictures drawn by Philip Longson: