We go behind the scenes of Martine Nouet’s à table: whisky from glass to plate to hear how Nouet relocated from Normandy to the Hebrides and found the perfect pairing of food and whisky.

The title of Martine Nouet’s new book, à table: whisky from glass to plate, intriguingly hints towards French influence. Martine was born in Normandy and from a very early age she remembers the joy of her mother’s summons to the table, “À table, les enfants!” In her own words Martine reveals how her childhood shaped the book:

“Those magical words still resound in my memory as a prelude to delight. I was the first to rush to the dining table. Always hungry, breathing in the delicious aromas of the chicken roasting in the oven or the crème caramel which would make my day, I was the happiest girl in the world. I still experience the same thrill of pleasure each time I come to the table, especially if friends are joining me. This is why I chose this title, which symbolizes two of my favourite ways of being: sharing and enjoying.”

While it is not surprising that Martine’s chosen career centered upon food and drink, what is surprising is her transition from France to Scotland. Martine first discovered whisky when she was working as a journalist, covering food and drink in France. In 1990, still working in this area, she visited the Isle of Islay, famous for its single malt whiskies. She recounts how, descending from the plane and before her feet had even touched the ground, she was smitten with the purity of the sea-salted air. There and then she wished that Islay would one day become her home. In 2001 she found a cottage in need of renovation and seven years later, in 2008, she settled into her new Hebridean home.

But it was not just the island; whisky too captivated her heart. Since that first visit to Scotland, Martine has established herself as an acclaimed whisky and food writer. She hosts dinners world-wide, introducing her guests to the sensory delights of pairing a particular whisky to a food counterpart to enhance its true essence. Anyone who attends a session with Martine leaves enthused and it has long been demanded that she produce a cookbook. Here it is at last!

Islay

à table: whisky from glass to plate is priced £20 and published by Ailsa Press.

In this humorous short story from LoveSexTravelMusik first-time visitors to Copenhagen, including Hans and Daniel, take in the major sights of the city while discovering that the perpetual happiness of the Danes is, to their relief, unrealistic.

Extract from LoveSexTravelMusik: Stories for the Easyjet Generation

By Rodge Glass

Published by Freight Books

ORIENTATION #1

Visitors will find the Tivoli1 easily. This 170-year-old landmark — described on its official website as a unique mix of amusement park, dining area and performance venue — is conveniently situated in Center (the area also known as K, or Indre By) and is clearly signposted on surrounding streets. Tivoli is prominently advertised on the Top Attractions page of visitcopenhagen.com (where you can source things to do under categories like Gay, Climate Friendly and Kids), and also in the many paperback guides available for a price which can surely not be sustained in this age of affordable data roaming. Chances are, the entrance is only ten or fifteen minutes’ walk from your hotel. So get there and get in the queue. It’s very straightforward to find.

What you may find less straightforward is the reason you are in the Tivoli at all. Indeed, even at the moment you suggested a visit to your partner, friends or children, you may have been unable to remember why you chose this place over any other number of attractions in this City of Towers, such as the ruins of Bishop Absalon’s 12th Century Castle, or the ever-popular Carlsberg Brewery. It’s not like you knew the history of the Tivoli. You’re not planning to ride the rollercoaster. Some of the visitors in the queue with you may say they always wanted to come here; others may blame Highlight Syndrome, the phenomenon by which tourists are drawn to already popular sites, creating a self-perpetuating escalation in visitor numbers. Still others may more honestly ask, Isn’t this what everyone does?

Denmark is a land rich in culture and heritage; many believe the site known as København was founded in the late Viking age, so there’s history in these streets. In 1658 the city withstood a furious assault led by the Swedish King Charles X (1622-1660). In 1728 it burned to the ground and had to be completely rebuilt. The same happened in 1795. It’s rarely taught in British schools but Nelson exploded some of Denmark’s finest ships here in 1801, widely considered the famous Admiral’s hardest-fought victory, and in 1807, the British subjected Copenhagen to what many now call the first terror bombardment of a civilian population. And that’s not mentioning defeat by the Prussians in 1864, where Denmark lost one fifth of itself to Prussia — or occupation by the Nazis in more recent times. So Danes are tough, they’ve survived more than a little domination by larger neighbours, and if you reach out to Dr Bo Nielsen, a distinguished local Professor who happens to be walking past the Tivoli at this exact moment, you’ll discover how much you don’t know. Tap him on the shoulder. Ask him to prise open Denmark for you while the queue trickles forward. Bo can reach into cracks in the walls and draw out bunches of flowers. He can make a dish out of nothing. And isn’t that what travel is all about? So fire him a question — what are you interested in? The Royals? Really? Okay, you’re in charge. Whatever’s your thing is our thing too.

The Tivoli in Cophenhagen

Bo will explain that, though not as widely advertised as the British Windsors (who have a bigger budget and PR staff) or Juan Carlos’s increasingly scandal-prone Spanish House of Bourbon, there is a fully functioning, respectable Royal Family here in Denmark, which is one of the oldest in the world. Since 1972 this has been led by Margrethe II (1940 — ), the first Danish Queen since the Act of Succession and subsequent referendum of 1953. She recently celebrated 40 years on the throne by first laying wreaths at her parents’ graves, then riding from her birthplace, Amalienborg Palace, to the Rådhus (City Hall) in a gold carriage, escorted by the Regiment of Garderhusars. There she and other Royals attended a reception in Margrethe’s honour and listened to a series of speeches about how great they all are. But you’re probably not interested in dry constitutional details. If Bo focuses on them too much, ask him for more colour. More humanity. He won’t be offended.

In a patient, clear, lilting accent, Bo will tell you that Margrethe II was raised in Denmark, before spending a year at boarding school in Hampshire and going on to study Prehistoric Archeology at Cambridge University— he’ll tell you she speaks five languages and married a French diplomat. Otherwise, as any specialist will confirm, the Danish Royal family is riddled with Greeks. It’s also related to the Spaniards via their Queen Sofia, a prominent member of the tongue-twisting Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg dynasty. That sounds like a complicated family tree but it’s all one big bowl of royal soup. Despite the French call for Liberté! Egalité! Fraternité! and Robespierre’s guillotine-happy Terror, visitors to Copenhagen will note that over two centuries later, much of Europe’s aristocracy is still alive and as incestuous as ever. It benefits from politicians who make them look positively democratic. Anyway, visit the Palace — as Bo will point out, it’s enjoyable as a visual spectacle even if you’re a republican or some kind of communist.

It also hosts fine examples of Danish Rococo architecture. Ask Bo about that and his eyes will become torches; his wife prefers people to buildings and so he rarely gets the chance to talk on the subject. Once you’ve finished chatting, let Bo go on his way. He’s already late for a meeting and has been too polite to say so.

Step back in line.

The queue has hardly moved. It’s the busiest time of the week and the height of the season, so there’s no point cursing. This was the only week you could get off work anyway — it’s not like there was another option. Perhaps, while you wait to be admitted to Denmark’s No.1 tourist spot, contemplate Bo’s knowledge of his nation and consider what you might learn if you listened to these walls. And what about the others: is the Canadian family of five in the next line having a good time? Are the couple behind arguing? Even here you have to look hardto find anyone who is totally, truly joyful. So visitors toCopenhagen may wish to consider what makes you feel like a child on a swing.

Ahead in the queue, Richard from Johannesburg is gazing through the entrance at the resident Tivoli orchestra, who are playing the theme tune to Disney’s The Little Mermaid. He’s forty-three and not keen on instrumental music, but the notes have become words and now his skin is dancing. Like many visitors to Copenhagen, the imitation Little Mermaid statue in Langelinie2 is Richard’s next stop after here.

Though he’s not aware of Hans Christian Andersen’s 1837 fairy tale3, or indeed the opera, and would probably dislike both, the sanitised Disney film is his daughter’s favourite.

He’s not seen her since the start of an access dispute but is planning to email his pictures to California where she now lives with her mother. This will be the start of a bad year — what the French would call a Série Noire— which will end with a conviction for trafficking South African girls to Europe, and bring a speedy end to the access dispute. He might not be a good guy, he might have body odour issues and an online dating profile full of lies, but if you forget the background noise and just look, Richard is simply a man, in the sun, enjoying an innocent sound rising from the bandstand and filling the whole park with colour. Soon the sounds will evaporate, as useless to him and to us as a sword made of sand. But for now Richard is a singing pitchfork. And what’s so wrong with that? You can see demons everywhere in this world, but you’ll never smile in your sleep.

Actually, this wait is ridiculous.

Look to your left. See that door peeping open? That’s a Security entrance. The staff are paid badly and poorly motivated here, so it’s easy to ghost through, and besides, the entrance price is a joke.

Step away from the queue.

Visitors to the city sometimes called Københavnstrup4 will notice as you duck under the Security Only sign and swim towards the crowds that it’s party time in the Tivoli.

It’s always party time! Here, excitement is continuous and consequence-free. There are over twenty restaurants and many bars. The entertainment is world class and it’s all laid out for you: it couldn’t be easier. Perhaps you find it relaxing to watch fish? If so, you can visit the aquarium and follow the feeding timetable: you’ve missed the sharks at 1300 but the seahorses are at 1500, piranhas at 1600 and the octopus, a real favourite with the little ones, is at 1700. After that you can take in a ballet at the Pantomime Theatre or a classical piece at the Concert Hall. It’s Friday, which means Fredagsrock, and the cream of Danish music. All tastes are catered for — but perhaps you’ll get more from your visit if you step away from the crowd. Yes, this way. Behind this bush. Shh. See those two men over there? At the outside tables, the bar next to the ice cream parlour? Come on, come closer. Listen in.

Meet Hans, 29, and Daniel, 27. Hans has been single for five years, and struggling with manic depression for ten. Daniel hasn’t stopped shaking since he left home. He’s been single for five days, since his relationship with Jennifer finally snapped and she returned to her mother, in tears. Both men are drinking cold beers in the sunshine. Both got EasyJet flights for the price of a family meal at the Tivoli, they both came alone, and became friends late last night, meeting at a strip club bar populated by Romanian, Russian and Thai girls who feed off the sex tourists, responsibly wiring money home every month to their families. These girls could have told Hans and Daniel something about sacrifice if only they’d asked a question or two — but they only wanted to talk about themselves.

How women treated them. How they’d given up on love.

How they were here because they’d run out of hope.

Hans and Daniel drank in the club for hours, one eye on the floor show, pouring their lives all over each other. At intervals they tagged, going through to a back room where different girls danced for them. These girls did their standard act, then pulled each man’s head softly to their breasts and listened to them talk. They whispered I love you and rubbed up against their jeans before sending them back to the bar. Later on, their colleagues repeated the process. Hans and Daniel left with empty pockets, having discovered they were currently reading exactly the same book, and had come to this part of Denmark sometimes referred to as Djævleøen (Devil’s Island)5 for the same reason. This was evidence! The fates had brought them together! They resolved to remain friends for life, making their promise at 5.30am on a dark Copenhagen side street. It’s lunchtime now, they haven’t slept, and both men are still drunk.6

If visitors look closely between Hans and Daniel they’ll notice that sitting face-up on their table there’s a copy of the book they were talking about, Affluenza by Oliver James. This edition has a man and a woman on the cover, both elegantly dressed, both standing in a futuristic lift, looking like they’ve lost a bet.7 In the book, the author argues that the more money human beings have, the less happy they are. Brazil, this is true. China, this is true. Australia: absolutely true. In seventeen case studies (some of which Hans skipped — he runs a business and doesn’t have much spare time) James links happiness to earnings, to the GDP of a nation. People in these nations get a pay rise, they get depressed. They buy a big house, they yearn for the cramped terrace they were raised in with their sisters. They win the lottery, they notice old friends acting differently and soon start dreaming of suicide.

But it doesn’t count for everywhere. Nearly, but not quite. Look, visitors to Copenhagen: the exception is all around you. In Denmark, it turns out, people are fairly happy, even though they have the crippling disadvantage of being rich. The book says so. The studies prove it. It’s something to do with equality between the genders and paternity leave or whatever. So visitors might want to change that schedule of theirs and study these streets, the buildings, the laws and regulations of this country that create such a successful blend, instead of standing with all the other moneyed miseries and taking photographs of the Little Mermaid. Hoover up the smell here. Talk to people.

Ask them how they live. This country is more likely to leave you at ease in your own skin. That is, if you leave the Tivoli for a second and go see something real.

For the last eight hours, Hans and Daniel have been touring places they think will make them happy. The Tivoli was supposed to be one of them, and in the haze of the strip club the idea seemed funny — from one extreme to another, no? They got in early, before the queue grew arms and legs. They went on some rides, ate ice cream, saw a show. They laughed for a couple of hours. But now time is treacle, all they can see are ghosts, and discussing the book is making it worse. Daniel in particular is drinking hard, to wipe out Jennifer. Love’s a hard thing to kill. So now, when Hans suggests a visit to Christiania, Copenhagen’s famous free state where marijuana is effectively legal, Daniel agrees. He’s never tried drugs, either hard or soft. He’s a bit of a drugs prude. But, stripped, hollowed and desperate to be someone else, he feels that now, when everything he feared losing has already been lost, he might as well get wasted — if only for something to do, and to escape the couples holding hands here. So Hans and Daniel get up, take the book and begin walking through the Tivoli. Follow them. They’ve no idea where they’re going but who cares?

Affluenza will surely be their guide in this city some call the Queen of the Sea. And it’s not like they’re in a rush. If they’d looked up events in Copenhagen before arriving, Hans and Daniel might had a different adventure.

At this exact moment they’re walking right past a café which does the best schnapps and herring in Denmark, and for a reasonable price too. Only a short walk away is the Literaturhaus, where tonight Carsten will spin golden word webs for an audience who will fly out of the door afterwards, looking at the world anew. Not that Hans and Daniel are into this sort of thing but they could be spontaneous. They could join the tattooed, the pierced and the hooded at an underground electronica club at the next corner, dancing themselves happy till the early hours.

But no, they haven’t got past the obvious. As the two men wander across a road, almost getting run over, Hans says, Maybe we should just throw all our money away. He looks left and right, thinks about which direction to go in, then takes a guess. Slurring his words he says, Then we won’t be rich. And we’ll be happy. How much have you got?

Keep following, visitors to Copenhagen: see how, for a moment, Daniel is unable to answer. Hans might be living off a generous allowance from his father in a tidy apartment in Kreuzberg, but since losing his job, Daniel has been struggling to accept the idea that where he’s from, it’s the excess of money, not the lack of it, that’s the problem. He says, Actually mate, I’m nearly at my overdraft limit. Then, But yeah, why not? Daniel raises both hands in the air, lets out a roar — ON TO CHRISTIANIA! — then falls. Hans drags him up and the two men stagger forwards, singing and linking arms as they walk, bathed in sunshine and, they imagine, the warmth of the Danish people. It might look dirty to you but if you asked both men, at this exact moment, they’d tell you: this is the cleanest they’ve felt in years. Yes, alcohol is a depressant, but it also gifts fleeting moments of joy.

Visitors to Copenhagen will need to keep their distance.

Or else they’ll spot us.

At this exact moment, Hans and Daniel and are only just realising they have come full circle, being almost back at the entrance to the Tivoli. They can see it up ahead. They realise the mistake they’ve made and at the exact same moment they crack up, unable to hold back how absurd this all is. Say what you like about these two but at least they’re able to poke fun at themselves. They can’t stop laughing, in fact. And they instantly give up on the idea of going to Christiania, at least for tonight. Watch them hug and laugh, long and deep. For a while there, before they finally pulled apart, Daniel wondered whether he and his new friend had become one person. Now they’re definitely two people. From where we’re standing, Hans is now slightly in shadow, facing one way, and Daniel has his back to us, facing the other.

This is the beginning of the end for them. After all, in a few days they will want to forget their mistakes here, also their all-night quest, and the best way to do that is silence.

It’ll be easy. They can swap numbers and email addresses, then not use them. But for now they hold themselves together, keep telling themselves they’re doing something worthwhile. As we can see, Hans lights a cigarette, stops a local in the street and asks, Can you recommend a bar where there will be absolutely no tourists? A woman in her forties answers, But if I tell you where it is, there will soon be two tourists there. Why don’t you try the Tivoli? The queue seems to have gone down a little. As the local woman walks away Hans says to Daniel, She seemed cheerful. Maybe we should ask her for the secret. But before they can act, she’s gone, disappeared into the crowd. Hans suggests he and Daniel rest by the entrance a while. All this searching for happiness is exhausting.

If any of the above reminds you of your own life then simply step away. Nobody will blame you. Get back in the queue and have yourself a nice pleasant time — go up and down the rollercoaster, put off admitting the truth and get your picture taken with Pitzi, the Tivoli mascot.

I’ll let you decide whether to stay here or leave: you are in charge of these adventures. If you’re feeling wild you could leave the crowds and head out to Jutland to explore the area around Hald Sø and Dollerup Bakker (Hald Lake and the Dollerup Hills), or go to the stunning Mols Bjerge National Park, right on the nose of Jutland, where you can witness first-hand the rolling hills formed at the end of the last ice age. Hire a bike: ride it. As you can see, cycling is popular here, and some of the cyclists are smiling. But it doesn’t matter if you don’t like physical exercise, there are many other ways to amuse yourself. Georg Carstensen (1812-1857) reminded King Christian VII (1786 — 1848) during his application for the original five year charter to create Tivoli, When the people are amusing themselves, they do not think about politics. But then, maybe some of us don’t need to be distracted any more. The people of Denmark are happier than most. And you could be too, if you listen to the walls.

1 The Danish Tivoli was originally called Tivoli and Vauxhall. It was named after the Jardin de Tivoli in Paris (which was, in turn, named after the Tivoli near Rome), and also the Vauxhall Gardens in London, England. ‘Tivoli Gardens’ is also a term used to refer to a community in Kingston, Jamaica.

2 Sculpted by Edvard Eriksen, this was commissioned by Carl Jacobsen, son of the founder of Carlsberg, after he witnessed The Little Mermaid ballet performed at Copenhagen’s Royal Theatre. The prima ballerina, Ellen Price, modelled for the head of the statue, while the sculptor’s wife, who was prepared to model in the nude, provided the body. The statue in Copenhagen Harbour, which has been defaced many times, has always been a copy. The original is kept at an undisclosed location.

3 The original 1837 story, titled Den Lille Havfrue, features cut out tongues, eternal damnation, betrayal and the little mermaid dancing in excruciating pain: fans of the Disney version wouldn’t recognise it.

4 This is a derogatory nickname used by Danes who are not from Copenhagen. It translates as ‘the little unimportant city of Copenhagen’.

5 This is another derogatory nickname used by some in Jutland for the whole of Zealand, of which Copenhagen is a part. These Jutlanders make no distinction between Copenhagen and the rest of the island, though West Zealand and Copenhagen are very different in nature.

6 There is no point in visitors becoming distracted at this juncture by the Swedish teenager storming past the two men with her headphones in, mascara streaking down her cheeks and pretending to play the drums. She’s wearing full goth uniform and is full up with music: SOME PEOPLE’S LOVE ISN’T STRONG ENOUGH she screams — and given her family background, she does have a point. Her tears are a flood. She has a bruise on her left cheek. She’s run away from parents who are dining at a restaurant in the Tivoli and are done pandering to her tantrums. This girl has never been at ease and she never will be. Look into her future and see that no matter how many people try to help, she will never be reached. She will commit suicide in seven years’ time. She can’t help us in our quest, some people are just doomed I suppose — so why look even for a second? If you offered her a tissue, a hug, some advice, she probably wouldn’t be interested. If you offered her money, she’d reject it. The reality is, some people are just happier being unhappy. Go on, return to Hans and Daniel.

7 Oliver James is a popular psychologist, also the author of They Fuck You Up: How to Survive Family Life (Bloomsbury, 2002), named after the famous opening lines of the Philip Larkin poem. Affluenza: How to Be Successful and Stay Sane (Vermilion, 2007) has since been followed by a sequel to They Fuck You Up, entitled, How Not to Fuck Them Up, (Vermilion, 2011). When Hans becomes a father this time next year, he’ll buy it.

Travel back in time to the city of Salonika in 1916. Formerly Ottoman and now suddenly Greek, it is filled with French, British and Serbian soldiers defending it against the Austro-German and Bulgarian forces to the north. In a nominally neutral city seething with wartime intrigue, café society continues unperturbed.

Extract from The Birdcage

By Clive Aslet

Published by Sandstone Press

Red plush, gilt carving and mirror glass; chairs by Thonet drawn up to round tables with marble tops. This was the international style of Paris, London, Vienna, Budapest, Turin… and Molho Frères. The café was like the wayward child of one of Europe’s great metropolitan cities which had run away to find itself lost among the wooden streets of Salonika. There it seemed a little overdressed. The Frères, one of whom was bound to be found in the establishment that bore their name, were similar: cosmopolitan, pomaded, looking endlessly surprised that they were not in a more imposing city. Although the pre-war café had been very different from its present manifestation, the Molho patriarch had nevertheless followed Jewish custom by sending his sons to the other cities to improve their chances in life. One brother could help another. If Istanbul disappointed, trade might be better in Trieste. One by one they had been called home. For café proprietors, Salonika was the place to be.

Only part of the café lay inside. To enter it, you had to squeeze past tables that spilled out onto the pavement and sometimes into the street, one of the busiest of the city. Whereas the interior was brightly lit to show off the novelty of the electric light, the mood of the terrace was softer: shaded, beneath vines, by day, mysterious, with the twinkling of candles, by night. Men who stayed inside usually had a half-acknowledged desire to watch the chocolate maker at her craft. Her profile was precisely that of a bust of Queen Nefertiti which German archaeologists had recently found in Egypt.

Custom at Molho’s had been nothing much before the War, and some of the Salonika community might have doubted the family’s wisdom in investing so much in a concern whose takings were a thin silver stream, not a golden gush. Salonika, Pearl of the Aegean, was a merchant city. Although it contained some prosperous families, they did not like to spend two piastres where one would do. A merchant would take a coffee, clicking his worry beads as he did so; it would last all morning. The Jewish matrons, who rewarded the good behaviour of their offspring with cakes, allowed only one drink each, and left no tip. Once the French and then British arrived in 1915, however, the tills rang merrily. The café was always full. Its doors opened to yawning officers, newly arrived on an overnight sleeper train from upcountry, and wanting breakfast. Men with sagging spirits and red eyes looked in for a mid-morning refresher. Aperitifs were served before lunch, tea in the afternoon, cocktails at sundown. Dawn might be breaking as the last of the previous night’s tables were cleared and the rats took undisputed possession of the kitchen. Their reign, though, was short. Molho’s had barely drawn breath, let alone closed its sleepy eyes, before the lock turned in the door and a flat-footed waiter began to clatter the coffee pots.

In choosing Molho’s as the place to begin an evening in female company, Sunny showed no originality. Officers of all the Allied nations regarded it as de rigueur. Not that everyone was lucky enough to have a nurse to take. Others went in groups, or by themselves. The atmosphere encouraged conversation. A French artilleryman might be observed noisily exchanging ideas with a member of the Russian cavalry, or an Italian transport officer, none of whom spoke the other’s language, so that communication took place only through gestures and imitative sounds, the cavalryman turning his chair into a mount and striking his thigh with an imaginary whip, the officer of the artillery making a dumb show of exploding shells. Molho’s inspired feelings of good fellowship. To the polyglot military force, its international character gave a connection with the larger world – the one that existed beyond the confines of the Birdcage, the one to which they would go back after the war. They could feel at home at Molho’s, when so much of Salonika was strange.

Or so it was with the more sophisticated officers, the ones – and there were many of them – who ordered their uniforms from West End tailors, towered over malnourished Other Ranks and generally bloomed with the healthy pink sleekness of prosperity. No clothes hung well on Winner. His uniform had quickly become a collection of bulges and creases, which seemed only to have a distant kinship with the sartorial elegancies on display at Molho’s. Short, swarthy and heavily spectacled, he seemed less of a god than an imp.

In London, Winner had not been a Café Royal man. He said he could not afford it, but that was only part of the story; had he been as rich as Croesus, he would still have preferred to hurry home to his village beside the marshes.

Isabel would enjoy Molho’s, Winner imagined; by Salonika standards, it was smart – too smart, perhaps. She was clearly not a young lady to go to such places in London, with their overtone of actresses and the demi-monde; but this was wartime. Salonika was different. Molho’s was like a kind of club for both sexes, if such a thing could be imagined. It was perfectly above board. She had been brought up to enjoy company.

Elsie was, of course, a different quantity, but she came as part of the package. She was the part that Winner felt more comfortable with. She had not been to the Café Royal; of course not – you could not expect someone in her position to have gone anywhere. That, too, was the extraordinary thing about wartime. Isabel and Elsie were now sitting at the same table. Winner protectively showed her to a place next to his. He tripped over the leg of a neighbouring chair while doing so.

The men had a little money in hand. In comparison with the golden coinage of England, the grubby drachma notes seemed laughable, disgusting. Like other soldiers, they did not understand, or care very much, what they were worth. It hardly seemed to matter in this foreign town.

Winner surveyed the scene through his spectacles, blinking. He did not feel part of it. ‘This is unexpected,’ he heard Isabel say, ‘for Salonika. I almost feel I’m on the stage.’

‘Is it as bad as that?’ asked Sunny. ‘We could go to the terrace, if you’re dazzled.’

‘I meant the uniforms. Those must be French chasseurs, enjoying their Vermouth. And what about those bejewelled specimens?’

‘Russians,’ returned Sunny. ‘Fantastic, aren’t they? That morose table is a group of Serbs – always so gloomy. Unlike the Italians.’

‘The little Greek officer doesn’t come off well by comparison – I say, the man in black with the long beard must be an Orthodox priest.’

‘Our khaki looks rather drab.’

Winner perceived Isabel turning to him. ‘As an artist, don’t you find the foreigners charming, Mr Winnington-Smith?’

To him, the room might have been an effusion of highly coloured mist. ‘Very,’ he said laconically.

‘Do see that beautiful creature making chocolate,’ continued Isabel in a stage whisper. Winner turned and peered at the chocolate girl, then hurriedly turned away, not wishing to appear rude. He did not know that the girl was thoroughly used to being watched with frank and sometimes insistent observation by officers. ‘Her hair almost comes down to her waist,’ continued Isabel. ‘I’m quite envious of it.’

‘Imagine coming here every day,’ exclaimed Elsie. To her, Molho’s was like one of the London gin palaces with which her father had been familiar, only less beery. Nor was there the same volume of noise. There was, however, an undeniable excitement to it.

‘What?’ reproved Isabel. ‘Making chocolate rather than nursing!’

‘I didn’t say I wanted to.’ Molho’s was not for the likes of her. ‘Mind you, we’ve got no patients at the hospital now that the Lieutenant has left,’ continued Elsie cockily. ‘In addition to which, Miss Hinchcliff, we’ve run out of petrol. We’re stuck.’ The fuel from the staff car had sufficed for the journey down to Salonika, but the Ford had used more than expected and it did not seem there would be enough to get back. They needed more, and had found it was not so easy to get.

Isabel found Elsie almost impertinent. She did not seem to know the rule (applicable to servants as well as children) about being seen and not heard. Elsie was there on sufferance: opinions were neither expected nor desired.

David Torrance casts an astute eye over the political backdrop to the EU Referendum on 23 June 2016, when the UK will vote to either remain part of or leave the European Union. Darren Hughes of the Electoral Reform Society also provides valuable insight into this important event.

Extract from EU Referendum: A Guide for Voters

By David Torrance

Published by Luath Press

Chapter 1: The Referendum

On 20 February David Cameron, the Prime Minister, set 23 June 2016 as the date for a referendum on the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union. On that day, voters will be asked the following question in a nation-wide ballot:

Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union, or leave the European Union?

‘This is perhaps the most important decision’, commented Mr Cameron, ‘the British people will have to take at the ballot box in our lifetimes.’ His Government had originally planned a straightforward ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ referendum, similar to that held on Scottish independence in September 2014, but the Electoral Commission (which regulates elections and referendums in the UK) believed this wording might be leading – or biased – and asked for it to be changed to ‘Remain’ and ‘Leave’.

The First Ministers of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland formally objected to the proposed June date, arguing that it came too soon after elections to their devolved assemblies and parliaments in May 2016, but the Prime Minister said he believed the two campaigns could comfortably co-exist. Mr Cameron also made it clear that members of his Government (and individual Conservative MPs) would be free to campaign on both sides of the referendum, and soon after he announced the referendum date Cabinet members began declaring in favour of Leave or Remain.

The possibility of holding another referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU (the first having been held in June 1975) had been raised over several decades, not least because it has changed significantly since the UK first joined in 1973, with many more members and a far greater number of shared competencies. Over the past 20 years Prime Ministers Tony Blair, Gordon Brown and David Cameron all promised to hold referendums on new EU treaties but later changed their minds, infuriating those who wanted to cast their verdict. A ballot was finally proposed, however, by Mr Cameron during a speech at Bloomberg’s London HQ in January 2013. He promised that if the Conservatives were re-elected at the May 2015 general election then he would ‘renegotiate’ the UK’s membership and hold an ‘in/out’ referendum by the end of 2017.

When the Conservatives won a majority at that election, MPs soon debated and passed the European Union Referendum Act 2015, which enables the referendum to take place on 23 June. It will be only the third such ballot to take place across the whole UK, the first having been in 1975 and the second in 2011 on switching to the Alternative Vote for elections to the House of Commons. Voters in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar will also vote in this referendum, as they are subject to full EU membership. Although EU citizens resident in the UK cannot vote in the referendum (except citizens of Ireland, Malta and Cyprus), UK citizens resident in other EU Member States can (as long as they have been resident overseas for less than 15 years), as can citizens of the Commonwealth or British Overseas Territories (like Bermuda and the Falklands) based in the UK or Gibraltar, provided they are old enough and on the electoral register. Citizens of Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Man, however, will not take part, as those British Crown Dependencies are not formally part of the EU.

The Electoral Commission will also regulate campaigning activity before 23 June. On 13 April it designated Vote Leave and Britain Stronger in Europe the ‘lead campaigners’ for, respectively, a Leave and Remain vote on the basis of how much cross-party support each enjoys, as well as campaign tactics and organisational capacity. There will be strict guidelines for campaign finance, but each lead campaigner can spend £7 million on making their respective cases; each will also gain access to television and radio airtime, mailshots and a publicly-funded grant of up to £600,000. The official referendum campaign began on 15 April 2016, and on polling day there will be 382 local voting areas grouped into 12 regional counts, each of which will have a separate declaration. The Chief Counting Officer will be Electoral Commission Chair Jenny Watson, who will announce the overall referendum result (combining the 12 regional counts and that in Gibraltar) in Manchester Town Hall on Friday 24 June 2016. A simple majority of the total vote is required to provide a winning result, for the UK to either Remain part of or Leave the European Union.

Although bagpipes are usually associated with Scotland, there is however a longstanding history of bagpipes throughout Europe where they have been played widely, especially from the 12th century onward, catalysed by trade opportunities and significant cultural developments.

Extract from Bagpipes: A National Collection of a National Instrument

By Hugh Cheape

Published by NMS Publishing

With so little known about the bagpipe in Europe in the course of the first millennium of the Christian era, one or two elements may be teased out of the known history since they represent, however remotely, aspects of the wider context, socially and culturally, of piping. A distance-marker stone, now in National Museums Scotland, raised at Bridgeness, Falkirk, at the east end of the Roman Wall in honour of the Second Legion, carries sculpted panels including a figure of a musician playing a double pipe. It is dated to AD142 and represents the earliest graphic evidence in Scotland for music and context, since this depicts a ceremony of animal sacrifice for the ritual cleansing of the Legion.

After the ‘fall’ of the Roman empire the milieu of urban life and forms of bureaucratic government were in decline, and trade and movement of people, goods and culture in suspension. We are given some insights into the ways of life of ‘Celtic’ peoples: first in Gaul through the writings of Greek and Roman authors, and second in the so-called ‘Irish Sagas’ such as the ‘Cattle Raid of Cooley’, giving as the late Prof. Kenneth Jackson described ‘a window on the Iron Age’ – in other words, a glimpse into prehistory. What is absent from all these descriptions is a detailed impression of the culture of music and song, although some early evidence on, for example, horns and trumpets, is illuminating. […]

Piper, carved in relief on a wooden panel, from Threave Castle, Calloway, late 15th century. © National Museums Scotland

In the wider Europe, the bagpipe appears to have spread rapidly in the circumstances of what historians have called the ‘Twelfth Century Renaissance’ when towns and town life, trade and trade routes developed dramatically, and music circulated as part of a minstrel and troubadour culture in the 12th and 13th centuries. At this time Scotland’s and England’s economies began to change radically with the reorganisation of landholding, the beginnings of forms of capitalist farming, and startling innovations detectable in the surviving datable and provenanced material culture, for example in pottery, metalworking and glass. Absent from the material record is anything organological such as pipes or bagpipes. Nothing of the importance and status of the Carnyx, an Iron Age bronze horn, has been recovered in Scotland archaeologically to throw light on the use of woodwind instruments in prehistory. A small ‘whistle’ of brass, 14cm in length, with six finger-holes, was excavated at a site, Tusculum, in North Berwick. A considerable number of ‘Jews Harps’, datable to different periods, have been recovered and provide some material evidence of a rich and protean musical tradition. More specifically three tuning pegs or pins (Scottish Gaelic cnagan) for the Highland harp or clarsach have come from the National Museums of Scotland’s excavations at Finlaggan, Islay, the former centre of the Lordship of the Isles. These items can be dated to the 14th century.

The bagpipe must have been played widely throughout Europe, especially in the period from the 12th century, when we first begin to learn more about it, until the 17th century when the pipes began to be displaced in music-making by new orders of instruments. From the 1100s our sources are documentary (then becoming more common), graphic evidence in the form of manuscript illumination with angels, monkeys, rabbits and pigs playing bagpipes, and carvings in stone and wood surviving usually in churches and monasteries. As a matter of note, the earliest surviving representations of the bagpipe in Scotland are the sculpted figures of the late 14th and early 15th centuries at Melrose and Roslin in southern Scotland. They (the piper on the Abbey at Melrose is a pig) are shown with single-drone instruments, most closely resembling the Spanish Gaita of today rather than an imagined proto-Highland bagpipe. Melrose of course was a Cistercian monastery, strongly dependent culturally on its links with France. Roslin is a collegiate chapel, a cosmopolitan status symbol and aristocratic fashion statement of medieval Scotland. These vivid representations pose questions on the status of the pipes and pipers and contemporary attitudes towards them. If the pipes were an angelic instrument but also notionally played by pigs, a medieval symbol for gluttony and sin, attitudes were ambivalent.

Pig piper as carved stone ‘gargoyle’ on Melrose Abbey, dating probably to the rebuilding of the Cistercian monastery around 1358. This is one of the earliest representations of the bagpipe in Scotland and shares all its characteristics with European iconography. © National Museums Scotland

We learn about the bagpipe in Mediterranean countries such as Spain and Italy, in the Netherlands and England. Players or minstrels travelled the roads and seaways of Europe and provided some of the most popular entertainment in court, castle and burgh. Payments by the kings of England for music and minstrelsy are document in this period, and patronage was a matter of fashion as well as taste to be emulated by other ranks of society. The earliest possible references to piper-minstrels in Scotland are for the reign of David II (1329-71). They are certainly travelling folk, possibly from England or the Continent, rather than court appointments. They brought news and gossip, as well as music and song, to a highly localised world. The function of the bagpipe was therefore to provide music for song and dance, and also evidently for work, to enliven and quicken toil.

A sense of Europe as an entity with its own cultural traits (such as music) emerged, particularly under the influence of the Christian church and pressure from without. Under attack from Islam, the counter-attack was launched by the Papacy, and a series of military expeditions was mounted in the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries to recover Jerusalem and the Holy Land. The linking of Western Europe to the Eastern Mediterranean and prolonged contacts with the Arab world, particularly through Byzantium, Venice, Sicily and Spain, reintroduced Western Europe to the arts and sciences of the Greek and Roman, a civilisation which had also evolved with the learning of Islam. Traders and colonisers brought back musical instruments such as the lute and other string instruments, and wind instruments such as the shawm which was also widely distributed throughout Asia.

In contrast to the UK, 88 percent of countries in the world have a school starting age of six or seven. Sue Palmer draws upon Nordic schooling in particular to passionately argue that young children who actively play and explore for longer are more likely to be resilient, healthy and motivated to learn throughout their lives.

Give Me A Child Till He Is Seven Years Old…

You’re probably aware of problems in English education. More exams than any other country – testing system currently in chaos. Long school days with break-times reduced due to bullying. Miserable teachers, kids under stress, a crisis in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). Last month, thousands of worried parents actually kept their children off school for a day in protest.

Scottish schools are, thank goodness, in rather better shape. But we’ve had a few exam problems too, our teenagers are the most stressed-out in Europe and Scotland’s CAMHS is just as over-stretched as England’s. Nicola Sturgeon’s decision to introduce national tests in primary schools is likely to increase pressures on children, and from an earlier age.

Contrast all this with education in Finland. No national tests till eighteen, no inspections, short school days with fifteen minutes recess every hour, confident teachers, kids who ‘learn with joy’. And they don’t start school till they’re seven – before that, they spend four years learning through play in a kindergarten.

The laid-back Nordic approach obviously pays off. Finland leads the western world in international surveys of educational achievement, while the UK lingers near the bottom of the top twenty. It appears – not surprisingly – that children learn better when they’re relaxed and happy than when they’re stressed and overwrought. So rather than introducing more tests, why doesn’t Nicola Sturgeon look north for educational inspiration?

The starting point for Finland’s success is those play-based kindergartens. There’s a growing body of research showing that children who have plenty of opportunities for play – particularly active, outdoor play with other kids – are likely to be healthier (both physically and mentally), more socially well-adapted and more emotionally resilient than children who haven’t had these experiences. So when play-rich kindergarten kids start school, they settle in more easily than their play-poor counterparts.

In fact, play is the inborn human learning drive – it’s the way young human beings were designed by nature to find out about the world. Opportunities to learn through play – supported by well-qualified kindergarten staff – develop children’s curiosity, perseverance and desire to carry on learning. So, once they hit the classroom, they don’t need a draconian system of tests and targets to keep them up to scratch.

In the past, we could take it for granted that children reaped the developmental benefits of play – even in countries (like the UK) with an extremely early school starting age, they’d be playing outdoors with their pals after school, at weekends and in the holidays. But twenty-first century lifestyles have transformed children’s recreational habits. From an increasingly early age, active outdoor play is being displaced by indoor sedentary screen-gazing.

It was concern about the long-term consequences of this change that inspired my book Upstart: The case for Raising the School Starting Age and Providing What the Under-Sevens Really Need. I believe British children are becoming seriously play-deprived, which is contributing to both physical and mental health problems, as well as our lack-lustre educational performance. Rather than piling on the pressure with more tests, governments in the UK should learn from Finland (and other educationally successful European countries, such as Switzerland and Estonia) and provide a play-based introduction to education for the under-sevens. All children would benefit from a few carefree years before formal schooling begins when they can run, jump, explore, experiment, sing songs, paint pictures, make models, listen to stories and learn about the natural world by getting out and about in it (the woods, the beach, local wild spaces).

There’s plenty of research to support Upstart’s case. Long-term studies suggest that any advantage gained from an early start on desk-bound learning tends to ‘wash out’ by the time children reach their teens, but the social and emotional consequences can last a lifetime. A too-early formal schooling has been associated with overall under-achievement, relationship difficulties in mid-life, stress-related physical and mental health problems… even premature death. And if you think that sounds far-fetched, check out the mountain of neuroscientific evidence about the impact of early childhood experiences on lifelong well-being.

As the Jesuits put it: ‘Give me a child till he is seven years old and I will show you the man.’ So rather than tightening the screws on the education system until all our children have mental health problems, British politicians should learn from our northern neighbours. Raise the school starting age and provide what the under-sevens really need: play.

Upstart: The Case for Raising the School Starting Age and Providing what the Under-Sevens Really Need is published by Floris Books on June 16th 2016

In this Q&A the celebrated Edinburgh-based author Alexander McCall Smith talks to Books from Scotland about his love of Italy and how it inspired his latest novel My Italian Bulldozer.

BfS: The novel exudes deep affection for Italy’s food, wine, people, and idiosyncrasies. How did your love of Italy begin and did you always intend to set a novel in Tuscany?

AMS: Who doesn’t love Italy? The food, the wine, the charm of the people, the heat of the sun, the history of the country, the language, the buildings – I could go on. I’m very fond of Italy. I spent some time there as a student and then as a visiting professor in the University of Siena. Like any writer, I store information from visits to this place or that and only years later find that it comes together in a story.

Montalcino in Tuscany, where My Italian Bulldozer is set.

BfS: My Italian Bulldozer is based on a highly popular short story. At that initial stage did you plan to develop it into a longer work? If so, is this process typical to the development of your writing?

AMS: I really enjoyed the characters and the setting of the short story but more than anything I was delighted with the response from readers. I revisited Tuscany last year and found that there was a lot of detail that I wanted to add and a longer story to be told. I have developed short stories into novels before – in fact The No.1 Ladies’ Detective Agency started life as a short story written for friends and we are now on book number sixteen of that particular series. But I would not say that this is typical of my writing. I write novels and serial novels, short stories, poetry, libretto and non-fiction books. I take a different approach to each and every one of these.

BfS: Paul Stuart, the protagonist, is a Scottish food writer who fits the longstanding tradition mentioned in the novel whereby ‘the North comes to the South to discover all about love and beauty’. What in particular made you decide to take Paul to Italy as opposed to elsewhere?

AMS: A recent holiday to Tuscany sealed his fate.

BfS: The novel references Italy’s rich and ancient history which you describe as ‘a palimpsest’ with ‘layers and layers of meaning’. What drew you to explore this in the novel?

AMS: Italy’s history, both ancient and more recent, has long held a fascination for me.

BfS: The Tuscan setting undoubtedly shapes Paul’s literal and figurative journey in My Italian Bulldozer and you recently said that places you get to know tend to find their ways into your books. In addition to Italy, where else have you visited that captured your imagination?

AMS: ‘Place’ takes centre stage in many of my books – whether I am writing about Botswana, or Edinburgh, or Australia or Italy.

Alexander McCall Smith in Botswana. Photograph by Chris Watt.

BfS: Finally, what is next for you?

AMS: I have just completed the next book in The No.1 Ladies’ Detective Agency series, Precious and Grace, which will be published this Autumn. I am now writing the next volume in ‘Scotland Street’ which is currently appearing in daily episodes in the Scotsman newspaper and will be published in book form in August as The Bertie Project, and a new children’s book, The Sands of Shark Island, is also due out in the summer.

My Italian Bulldozer by Alexander McCall Smith is out now in hardback priced £14.99 from Polygon

Whether you’re visiting the islands or want to simply let your imagination take you there, there’s a book for that!

- Lewis

- Barra

- Mull, Coll & Tiree

- Islay, Jura & Colonsay

- Shetland

- Skye

- Harris

- Arran

- Uist

- Orkney

If you are getting out and about around Scotland then also check out the new food trail ebook from Visit Scotland.

‘If a city hasn’t been used by an artist, not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively.’ So observes Duncan Thaw, the protagonist of Alasdair Gray’s Scottish classic, Lanark. In the introduction to Dear Green Sounds below, editor Kate Molleson takes us through a journey of Glasgow’s musical history and landscape, locating its artistry in its music halls, churches and theatres, in ‘the bricks and stones that have made Glasgow’s music what it is today’.

Introduction

Edited by Kate Molleson

Published by Waverley Books

What makes a city musical? Glasgow’s cultural history is all fits and starts: centuries of reformation and migration, industrialisation and depression, great wealth, deep problems, sporadic regeneration. Today the place is sprawling, stylish in parts and rough around the edges. And yet, or so, it is a blazingly musical city.

This book aims to capture the spirit of that musicality. It could never have been written as one unified story. Glasgow became a UNESCO City of Music in 2008 thanks to the countless kinds of music that coexist on these streets. Delve into the demographics and it’s easy to see where that diversity comes from: Glasgow has always been a meeting place. It’s a city built by Celts and Romans, the Irish and Highlanders and recent communities too numerous to list here. Each has contributed its voice to the urban soundtrack. Glasgow’s music has been born of piety and poverty, pride and sectarianism, poor decisions and grand vision, bedroom pipedreams, and politics with a ‘p’, large and small. Incomers have sung of exile, community, isolation and integration; suburbs have bred songs of boredom, aspiration and sheer devilment. Classical music took off relatively late here but blossomed with the wealth of the Second City of the Empire, where merchants woke at 6 am to sing madrigals, and more than 100 choirs were going strong by the turn of the 20th century. Glasgow was flourishing and had something to sing about.

How to encompass such a raucous place in just one book? I could have attempted a great sweeping chronology or designated a chapter to each major genre or big name. But music and cities don’t work like that; there are too many loose ends, blind corners, one-offs, crossbreeds.

Ultimately this is a book about music and place, so it seemed right to celebrate the buildings themselves: those hallowed and not-so-hallowed places where Glaswegians have flocked to hear, play, sing and shout their music over the centuries. Some venues are still standing, others tragically gone.

This book has taken shape as a series of snapshots. Each chapter focuses its lens on one of the pubs, ballrooms, clubs, concert halls, streets, recording studios, societies or holy places that have hosted the music made in Glasgow since the Middle Ages. Countless other buildings could have been included and countless other stories could have been told. There can be no comprehensive guide to this messy, mischievous city – and that is part of its great charm.

A Brief Look Back

Glasgow began as a fishing and trading village on the River Clyde. Its streets were laid to the sound of bone flutes, wooden whistles and folk songs. The Roman post of Cathures (c. AD 80) introduced chime bells and pipes of a different tune. Later, Celtic traders with their own songs settled in the area, and in the sixth century St. Mungo built his church where Glasgow Cathedral now stands, where early Christian chant was sung and where this book’s first chapter begins.

The earliest reference to an organ in Glasgow dates from 1520. By the onset of the Reformation there were more than 50 song schools across Scotland, and Glasgow’s 16th-century choristers were well versed in Gregorian chant and part singing. Life outside the kirk walls bustled to jigs and reels, ballads and airs, pipes, clarsachs, fiddles (mentioned in Scottish documents from about 1450 onward) and drums. The vast majority of music from this period was never written down, and still more was lost during the destruction brought about by the Reformation. In August 1560, the Scottish Parliament abolished the Mass and adopted Calvinism. Only the song schools of Edinburgh and St Andrews survived the first zealous wave of the Reformation. Whole churches were razed, destroying centuries’ worth of manuscripts and the means of employment for at least a generation of musicians. Church music was reduced to a handful of simple psalm tunes. Organs were frowned upon by the new church – too decorative – and music on the streets was hushed up. Like most of reformed Scotland, late 16th-century Glasgow was a quiet place to be.

In 1579, King James VI threw a lifeline to Scotland’s music. ‘The art of musik and singing,’ he warned in a personal decree, ‘is almaist decayit and sall shortly decay without tymous remeid be providit.’ He instructed all councils ‘of the maist speciall burrows of this realme’ to ‘erect and sett up ane sang scuill with ane maister sufficient and able for instructioun of the yowth in the said science of music.’ Glasgow’s post-Reformation ‘sang schwyll’ opened its doors in the 1630s under the instruction of ‘maister’ Duncan Burnett. The students sang in church but the psalms they intoned were much plainer than Scotland’s earlier polyphony.

Gradually, power structures shifted. The clout of the church gave way to the wealth of the merchants who had made Glasgow the second largest city in Scotland (after St Andrews) by 1670. This class of nouveau riche indulged in playing instrumental art music at home. International traders introduced foreign manuscripts and instruments into the mix – notably the Italian violin, which had turned up in Scotland by the early 17th century. This more resonant instrument all but wiped out the medieval fiddle, and with it came new musical inflections: English country dances, German hornpipes, ditties in the Italianate sonata style. The latest French fashions (lutes, virginals, clavichords, violins and viols) had already started filtering in with Scotland’s French queens. Louis de France, the most famous music teacher in Scotland during the late 17th century, taught privately in Glasgow homes from 1691. All very cosmopolitan!

Glasgow has always been a hub for Highlanders and Gaels, whose wandering came and went between Scotland and Ireland. The collapse of Highland communities in the decades after Culloden channelled an influx of Gaelic speakers southwards and the first stages of the Clearances brought more laments of exile to the city. The gap between Glasgow’s urban rich and poor grew alongside its industrial wealth, but culture paid less attention to class boundaries than social conditions did. Private soirees in the fine homes of the Trongate segued between rustic airs and refined imported tunes in a genre-defying blend that you’d be lucky to find nowadays.

Even Glasgow’s church music eventually began to loosen up. More churches in the city meant more precentors; more precentors meant more musical activity, and more room to manoeuvre. One bizarre permutation of the strict church rules was the ‘psalmody-rhyme’ – the practice of singing nonsensical lyrics to psalm tunes so that church choirs could practise their music without bandying about their sacred words. Imagine a foursquare psalm tune with these jaunty lyrics:

I gued and keekit up the lum,

The skies for to behold,

A daud o’ soot fell in my e’e,

Which did me quite blindfold.

Read the full introduction here:

This summer will see the launch of the inaugural Publishing Scotland International Fellowship, with publishers from across the globe convening in Edinburgh for an exchange with Scottish publishers and agents. This got us thinking more generally about the exciting role Scotland has to play on the international literary scene. Have a look at just a few of the cross-cultural engagements taking place in Scotland this year.

Publishing Scotland International Fellowship

We couldn’t resist telling you just a bit more about our own international event. Taking place between 24-30 August 2015, and timed to coincide with the Edinburgh International Book Festival, this new scheme has 8 international publishers visiting publishers and agents in Edinburgh, Glasgow and the Highlands, and provides networking opportunities, market presentations, and an engagement with the wider literature sector.

Funded with help from Creative Scotland, Scottish Development International, and Emergents, the visit aims to facilitate professional exchange between the international publishers and their Scottish counterparts, outside of the frenetic environment of trade fairs. The scheme will run in 2015 and 2016. For more information, contact Publishing Scotland.

- Peter Borland

- Markus Naegele

- Lina Muzur

- Halfdan Freihow

- Enrico Racca

- Sarah MacLachlan

This year, the Fellows are:

- Peter Borland, VP and Editorial Director, Atria/Simon and Schuster, US

- Halfdan Freihow, Publisher, Font Forlag, Norway

- Eduardo Rabasa, Foreign Rights Director, Sexto Piso, Mexico

- Enrico Racca, Editorial Director, Children’s books, Mondadori, Italy

- Markus Naegele, Heyne Hardcore Verlag, Germany

- Sarah MacLachlan, House of Anansi, Canada

- Lina Muzur, Aufbau Verlag, Germany

- Claire Wachtel, Harper Collins, US

Amnesty International Imprisoned Writers Series

Speaking of the EIBF, they will once again be bringing in their landmark Imprisoned Writers Series, run in conjunction with Amnesty International. It is difficult to overstate the importance of this series, which sees an array of authors, playwrights, politicians and poets give voice to the work of imprisoned writers from around the world, covering some of the most pressing human rights issues today. Events will run each day of the festival, with two events hosted by Scottish PEN this year:

In Memory of Armenia

Tunisia: Enemies of the State

The Robert Louis Stevenson Fellowship

Keeping company with some of history’s great artists, the 2015 Fellows have been named for this prestigious residency. The award aims to provide Scottish writers with an escape to the French countryside at Hôtel Chevillon International Arts Centre at Grez-sur-Loing, a favourite haunt of Robert Louis Stevenson and many other renowned artists and musicians. The fellowships are awarded by The Scottish Book Trust, with funding from Creative Scotland.

The International Writers’ Conference Revisited: Edinburgh, 1962

A look back at one of the great moments in Scotland’s literary history: this anthology from Cargo Publishing retraces the watershed literary conference of 1962, which brought together prestigious delegates from around the globe, ignited international debate and influenced a generation of literary imaginations. The book includes photographs from the event, as well as newly-commissioned pieces by the event organisers.

The Translation Gap

Finally, as part of the EIBF’s Talking Translations series, Publishing Scotland will bring together a panel of publishers, translators and writers to discuss the place of translated fiction in Scotland. Tickets are on sale now.

For more than three decades, John Lister-Kaye has been enraptured by the spectacular seasonal metamorphosis at Aigas, the world-renowned Highland Field Centre. Gods of the Morning follows a year though the turning of the seasons at Aigas, exploring the habits of the Highland animals, and in particular the birds – his gods of the morning – for whom he has nourished a lifelong passion.

Extract from Gods of the Morning

By John Lister-Kaye

Published by Canongate Books

Did ever the raven sing so like a lark,

That gives sweet tidings of the sun’s uprise?

Titus Andronicus, Act III, scene I,

William Shakespeare

There is nothing dull about a raven. As glossy as a midnight puddle, bigger than a buzzard, with a bill like a poleaxe and the eyes of an eagle, its brain is as sharp and as quick as a whiplash. Surfing the high mountain winds, ravens tumble with the ease and grace of trapeze artists, and their basso profundo calls are sonorous, rich and resonant, gifting a portent to the solemn gods of high places. Ravens surround us at Aigas, and they nest early.

Yesterday, a puzzling January day so gentled by a southerly breeze streaming to us from the Azores that it could easily have been April, I sauntered the half-mile to where the road lifts and snakes east, then veers north high above the river to look down into the black waters of the Aigas gorge, most of which is invisible to the casual passer-by sealed in his car. A day so beguiling under the cool winter sun that great tits began sawing and dunnocks bubbled and trilled from the roadside broom thickets. I wanted to see if the ravens were attending their habitual site on a vertical cliff overhanging the satanic flow of the Beauly River.

They weren’t, although a faint ‘cronk’ from somewhere high above and beyond the forested horizon echoed back at me from the rock walls. I hadn’t expected them to be at the nest site so early in the year, but because that seductive airstream had brought the rooks back to their nests for an hour or two before vanishing again, it got me thinking of crows in general and climate change in particular.

Attempting to draw conclusions about aberrations in climate from one or two odd incidents is risky and always bound to be proved wrong when suddenly everything happens in reverse. It is also unwise to work from the premise of any ‘norm’. What defines normal weather, and when did it become normal? Is a winter bound to be defined by cold and snow? Clearly not since Britain and many other parts of northern Europe have experienced mild, wet winters off and on for decades. And yet most careful observers are convinced our climate is changing. All I can do, trapped in our Highland glen, is to watch and monitor the common standards of climate, temperature, precipitation and wind speed, and do my best to work out the impact these fluctuating parameters have on the wildlife around us. I thought the ravens might throw some light on this conundrum.

Ravens are always the first to nest every year – nests built in early February, eggs laid towards the end of the month – but if the weather is clement our gorge pair often spend a few late-January days repairing the twiggy stack, now a yard high, that they have used for the last decade. The Aigas gorge is a perfect site for raising their brood of greedy, belly-bulging, reptilian fledglings. (As I write this, I am struck by an irresistible word-play: ravens nest in the Aigas gorge; ravens gorge in the Aigas nest.)

The valley is U-shaped and glacial, stretching back twenty-two miles into the Affric Mountains. As the ice thawed ten thousand years ago the meltwater streams created the broad, meandering flow of the river, which, on hitting a fault line in a wall of friable and ice-shattered conglomerate rock, washed out two separate channels, presenting us with a fifty-acre island, Eilean Aigas, bounded on both sides by a deep gorge with rushing falls and creating an ideal site for someone to come along and build a dam for hydro power, which is precisely what happened in the 1950s.

The gorge and the impressive Druim Falls, studded with rapids rolling around huge mid-stream rocks known as the Frogs, became a celebrated Victorian beauty spot and remains so, but the flooding of the falls by the hydro scheme caused the rapids to vanish, unless the river is very low when they re-emerge as foaming turbulence never quite breaking the surface. In a boat or canoe the going between damp and ferny seventy-foot walls is calm and eerily silent, but as you approach the flooded falls the flow suddenly springs into life as it grounds upon the submerged rocks, heaping up over them, carrying the air with them so that you are engulfed in rushing and streaming chevrons of white water.

The hydro dam (20-megawatt generation) undoubtedly cramped the gorge’s tourist appeal, but not for the birds. The high, vertical cliffs stretching for a quarter of a mile are ideal as a secure nest site and are variously occupied but jackdaws, kestrels and peregrines, grey wagtails and dippers as well as ravens, while cormorants whitewash the rocks with guano as they haul out on the Frogs to hang their oil-less feathers out to dry.

In 2014 Publishing Scotland celebrated 40 years of publishing in Scotland. To mark this occasion, an exhibition was produced in collaboration with SAPPHIRE and Edinburgh Napier University, showcasing some of the best of Scottish Publishing over the previous 40 years.

Please click on the images below.

See all of the 40 Years of Publishing in Scotland Exhibition Panels

To mark Robert Louis Stevenson Day, the Association for Scottish Literary Studies presented three uncanny stories by Robert Louis Stevenson: ‘Thrawn Janet’; ‘The Tale of Tod Lapraik’; and ‘The Bottle Imp’. These eerie tales of witches, warlocks, and demonic pacts are outstanding examples of the storyteller’s art. Listen to the readings below.

Thrawn Janet read by Alan Bissett

The Tale of Tod Lepraik read by James Robertson

This wee book is available to download from the ASLS website where you can also listen to Louise Welsh read The Bottle Imp.

Click any image to view the slideshow

Glasgow’s Book Festival turned 10 this year and put on a wonderful celebration of books in April. We’re already looking forward to next year, but, for now, check out this great video of some of the Aye Write! authors wishing the festival

a very happy birthday.

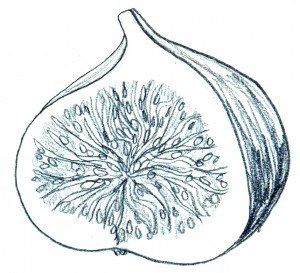

Happy Cooking!

Recipe from The Parlour Café Cookbook

By Gillian Veal

Published by Kitchen Press

Ingredients

250g shortcrust pastry

2 red onions, divided into eighths

1 tablespoon olive oil

150g ricotta cheese

3 sprigs thyme, leaves only

zest and juice of 1 unwaxed lemon

1 whole egg and 2 yolks, beaten

100g rocket

250g creamy Italian gorgonzola

3 ripe fresh figs, quartered

salt and freshly ground black pepper

also…

10” tart tin, greased

Preheat the oven to 190ºC and put a baking tray in to heat up.

Put a baking sheet in the oven to heat up, then roll out the pastry onto a lightly floured surface and line your tart case. Prick the base all over with a fork, cover with a piece of greaseproof paper and some baking beans (any dried bean will do) and put on the hot baking tray in the oven. Bake for 15 minutes before taking it out to cool (discarding the paper

Put a baking sheet in the oven to heat up, then roll out the pastry onto a lightly floured surface and line your tart case. Prick the base all over with a fork, cover with a piece of greaseproof paper and some baking beans (any dried bean will do) and put on the hot baking tray in the oven. Bake for 15 minutes before taking it out to cool (discarding the paper

and beans).

Put the onions on another baking tray, drizzle with the olive oil and roast for 20 minutes.

In a mixing bowl, beat the ricotta with the thyme, lemon zest and juice and the egg and yolks. Season well with salt and freshly ground black pepper. Spread the rocket out evenly on the cooled pastry case (it will almost fill it, but that’s ok, it cooks right down again) and pour over the ricotta mixture.

Break up the gorgonzola with your fingers and scatter it over, and then arrange the roasted onion and figs artfully or randomly on top, pressing them lightly in. Season lightly and bake for 25 minutes, or until the tart is puffy and golden. Best served warm (not hot) or at room temperature.

Serves 4-6

Kitchen Press is an award-winning independent publisher specialising in food writing. They work with independent restaurants and chefs to create bespoke illustrated cookbooks that capture the flavours that make them unique.

The New Writers Award recognises serious aspiring writers and provides them with the opportunity to develop their craft. Watch this space for the new up-and-coming names in literature.

This month, we introduce you to the writing of awardee Claire Squires.

Extract from Novel in Progress

By Claire Squires

They launched the wherry as the rain began to fall, and headed north across the dark river. Their kit lay across the flat bottom of the boat; the ladders, and the old and new ropes. Each one thought ahead to the Dome, standing solid at the centre of the city, seemingly unassailable, but their target for the evening. Aly felt her stomach twist and tighten, mingled anticipation and fear. At her side, she felt Paw’s eyes trained upon her, but she didn’t turn to meet his face. She glanced across the boat at Murdo, who smiled back crookedly.

She closed her eyes, and imagined the heights ahead. The easy route up the back of lower storeys of the building, and then the set of statues that ran all the way around it. A quick push onto the first, flat roof, but then the circular base of the Dome. Murdo and she had discussed their plan earlier, drawn diagrams and envisioned their route. The crux, they had decided, was at the beginning, getting traction onto the dome itself. It had none of the usual embellishments, but was sheer, sloping, and – they feared – slippery smooth. They’d worked out that their only chance was to get a good rope point over the statue at the top. Murdo had been practising all week, taking lessons from the men.

The wherry reached the northern shore. Murdo jumped ahead into the mud, running the rope up to the mooring. His father followed, and then all the men heaved it forwards so it was hidden from view. They stood quietly for their final briefing.

‘If anything goes wrong, the first back here should take the wherry over. Don’t wait for the ithers. We’ll meet back at the drinker,’ said Murdo’s Paw. ‘Aly, Murdo – if you get separated from the rest, take the tunnel. Go to the drinker and let John M’Nair know you’re there. Then head hame. He’ll send out for you when it’s safe.’

They moved through the streets, melding into the shadows cast by the tall buildings. They walked rapidly, the only noise the rough fabric of their clothing rubbing against itself. They skirted the art towers, its red-lit finials reaching high into the sky. Aly read its routes, seeing how she would tackle its verticles. She fell behind the group briefly, as the red lighting shifted to blue.

‘Wish you were climbing that tonight?’ whispered Murdo.

Aly summoned as much bravado as she could muster. ‘Naw, no really. We can always take it in on the way hame. You know, for warmin down.’

‘Aye right. Just fer the fun o it,’ Murdo responded. ‘Ah think we’ll all be wantin to be doon the drinker if this goes right, not up at the heights again.’

Aly nodded, and they continued through the dark streets to the Dome.

Have a look at just some of our favourite new titles from Scottish Publishers

- Michael Russell, described by the Scotsman as a ‘talent to be followed closely’, debuts with a novel, Lie of the Land (Polygon) set in a post-catastrophe Scotland

- Dacre’s War (Polygon) by Rosemary Goring, the sequel to the well-received After Flodden, follows the fortunes of Adam Crozier a decade after the battle of Flodden, in a story of personal and political vengeance

- Scarlett Thomas’s The Seed Collectors (Canongate) is a contemporary tale of inheritance, enlightenment, life, death, desire and family trees, and is out now in hardback. Neil Gaiman’s a fan, calling it ‘a sharply observed contemporary novel of real people and real plants and real desire and real hurt, and somehow also one of the sharpest fantasies I’ve encountered’

- Prolific writer Chris Dolan has released his latest novel, Aliyyah, a modern Arabian tale set in an unnamed war-torn country. Publisher Vagabond Voices describes it as ‘a Romeo and Juliet story, but one for an age where scientific materialism is crossing bloody swords with religion’

- In Eva Makis’ prize-winning fourth novel, The Spice Box Letters (Sandstone Press), Katerina inherits a wooden spice box containing letters and diaries after her grandmother dies. As she pieces together her family history, she learns of the shattering effects of the Armenian tragedy of 1915

- In poetry, Tessa Ransford’s new collection, A Good Cause (Luath Press), offers a new selection of previously uncollected poems, the ‘good cause’ being ultimately the intrinsic good of poetry itself

- In children’s, Cathy Forde’s new book, The Blitz Next Door (Floris Books), is the latest addition to the Kelpies series and centres on the devastating events of the Clydebank Blitz

- In non-fiction, 100 Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland (NGS) by John Leighton, the director-general of the gallery, features such beauties as the sumptuous home-grown Lady Agnew of Lochnaw (a keen favourite of Phil Jupitus, apparently…) as well as pictures by Titian, Rembrandt and Vermeer, Picasso, Hockney and Warhol

V&A Dundee – A Very Exciting Prospect Becoming a Reality