Author RD Dikstra talks to Books from Scotland about the inspiration behind his new children’s River Clyde-set picture book The Adventures of Captain Bobo: Bananas!

Your last book Tigeropolis was all about vegetarian tigers, so what’s the link to paddle steamers and the West Coast?

Actually my first involvement with publishing wasn’t Tigeropolis, but was in helping one of CalMac’s best known Masters, Captain Robin Hutchison, tell his life story in Hurricane Hutch’s Top 10 Ships of the Clyde. The book was as much a social history of the Clyde (from the War up to the late 90s), as it was a book about ships such as the Queen Mary, or the Waverley. In researching the book we heard many comical stories of life on board, but unfortunately we just couldn’t fit them all in. Nonetheless we knew theses stories needed to be told, and we also wanted to do that in a way that would appeal to children. The Clyde, and the sea-faring heritage of all the people who sailed those waters, are just too important to be forgotten. So, I think you can say the idea for Captain Bobo was born not long after Hurricane Hutch was first published back in 2014, it’s just taken us a while to finally get there.

What is the story of The Adventures of Captain Bobo?

The series is intended for children aged 4 plus, but hopefully will appeal to a far wider audience. In ‘Bananas’ we introduce the reader to Captain Bobo and his crew and of course to his wonderful old paddle steamer Red Gauntlet. All the stories are based loosely on real life events from the days before car ferries. This book is inspired by one story we heard about how animals used to be transported to and from the islands. In the story the new Island Safari Park’s star attraction misses the ferry and gets left behind. It’s left to Captain Bobo to try to save the day. I don’t think I’m giving too much away to say that with a little ingenuity, and some great teamwork from Red Gauntlet’s crew, it all ends surprisingly well.

So tell us a bit about the main characters.

The key characters are all part of Red Gauntlet’s crew :-

Captain Bobo is the very experienced captain who is always willing to go that extra mile to help people. His ship, Red Gauntlet, is an old paddle steamer – it’s due to be replaced by more modern vessels, but as the stories will show it’s always able to help save the day.

Sheila is First Mate – very much younger than Captain Bobo, but very able – she really knows her stuff and is always able to deal with a crisis.

Puffy Watt – is Chief Engineer – there is nothing he does not know about the workings of Red Gauntlet.

Then there’s Boing Boing the Assistant Engineer, Bleep the Bo’sun, Billy the Cabin Boy and Zoe the island’s Pier Master.

This particular book also features Tufty, a wonderful, and banana loving, elephant. I wouldn’t be surprised if he makes a reappearance later in the series.

Last, but not least, is Salty – Captain Bobo’s faithful dog – a Scots Terrier.

Animals seem to feature a great deal in your books. Why is that?

I’ve always been interested in wildlife and conservation – my Tigeropolis books are based on my travels in India and long time involvement in issues around tiger conservation. The tigers in Tigeropolis were inspired by my first ever encounter with a tiger – that tiger (a tigeress called Vijaya) seemed totally in control of events. The books are principally fun, but they do have an underlying message about conservation, and have been well received by a number of India’s foremost conservationists.

Is there any particular message in this new picture book?

Bananas! is principally just a good story, but I hope it helps foster some appreciation of wildlife (there’s even a dolphin making an all too rare appearance on the Clyde at one point). That and the value of teamwork.

So what’s your connection with the Clyde?

I was born in Glasgow, so had many trips down the Clyde in my childhood. I can still remember sailing down from the heart of Glasgow on the Jeannie Deans aged about 6 or 7, with all the sparks and flares, clanks and bangs coming from the shipyards, either side of the river, working away as we sailed by. For 10 years I also had a house right on the water at Skelmorlie, so I well remember making breakfast about 7 am with “Ding, Dong” … and … “Welcome Aboard Cal Mac,” blaring out of a tannoy from outside on the river as a car ferry slipped past on its first run of the day.

Who created the illustrations for the book and can you tell us how you worked with your illustrator?

We’ve been working with Matt Rowe since Tigeropolis when we fell in love with his characters. Children respond immediately to the characters – they are cute and full of expression, which helps bring life to the stories. We work well together – I set out roughly what might work and where, and Matt comes back with some pencil sketches which we then develop as needed. Strangely we have never met in person. Matt likes to work from home and, although we have regular calls and emails, we have yet to meet face to face.

The Adventures of Captain Bobo: Bananas! by RD Dikstra & Kay Hutchison with illustrations by Matt Rowes out now published by Belle Media priced £7.99.

Our monthly columnist meets Angus Roxburgh, the former foreign correspondent and former Kremlin PR advisor, to talk about his newly published memoir Moscow Calling. Roxburgh reveals some of the highlights of his long-standing career from Soviet times to the present, and explains why he has always felt affection for, and been compelled to understand, the inner workings of this complex country.

In June, far too late to include in Moscow Calling, his new book of memoirs, Angus Roxburgh found himself under arrest in a police station in Nizhny Novgorod.

These days, he no longer works as a foreign correspondent. Those stories he once filed for the Sunday Times and the BBC about the spectacular collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of the Wild West capitalism that replaced it, are old news. But every summer for the last few years, for those with enough money and interest, he has led political study tours to Russia, and that’s what he was doing, chatting over a hotel breakfast with the group he had shepherded into Nizhny Novgorod the previous evening, when five policemen walked in and placed them all under arrest.

Roxburgh couldn’t understand it. He’d led political study groups like this before, and there hadn’t been any trouble, nor was there any hint of anything wrong on this trip when they’d visited Moscow. The man they were meeting over breakfast was a supporter of Putin’s party, not an opposition leader. It didn’t add up.

The police took three members of the group and interrogated them for three or four hours before letting them go, but they held on to Roxburgh. Finally, his lawyer arrived. He went out of the room to talk to the police inspector and returned 20 minutes later. “You’ve got a choice,” the lawyer told Roxburgh. “Either they deport you now or you sign a confession admitting that you have broken the condition of your visa and pay a small fine.”

“I didn’t have a choice at all,” he tells me. “I had to look after the group. But I still don’t know what will happen the next time I apply for a visa when I apply again next summer.”

You have only to read Moscow Calling, recently published by Birlinn, to realise what Russia would lose if, next year, some idiot bureaucrat denies Roxburgh a visa. Foreign correspondents like him have long since became an endangered species, but someone like Roxburgh has an Russia that few if any westerners can match, from charting the wild absurdities of its bureaucracy to the innermost circles of the Kremlin, where he subsequently worked for three years as a PR adviser.

Let’s take absurd bureaucracy first. Back in the USSR, when he began working there as a translator in the late Seventies, Roxburgh saw it at first hand on innumerable occasions. When he and his wife wanted to return to Scotland and take Russian books home with them, anything published before 1976 had to be taxed at 100 per cent, so he had to provide a list of his books with publication dates certified by the Lenin Library with a fee payable at another building. Friends’ paintings could only be evaluated at a convent in the city on Tuesday mornings, with three photos of each painting and a letter approving export from the artist. No parcels could be wrapped, no notes left inside books, only one post office in the city could deal with anything sent abroad, no parcels weighing more than 25kg could be sent per day, each of them had to have four customs declaration forms and one accompanying form checked at a different counter… You get the idea.

Despite all that, Roxburgh’s affection for the country ran deep. He loved its contrariness, the bravery of its intellectuals, the depth of the friendships he made there. And when communism collapsed, he had a ringside seat. He was at the dissidents’ meetings at which the unsayable became sayable, saw the fissures open in the Baltic states and widen all the way across Eastern Europe. He’d just started working as the BBC’s man in Moscow when, on 8 December, 1991, Yeltsin and the leaders of Belorussia and the Ukraine signed a deal that effectively ended the USSR. He rang the newsdesk and informed the deputy news editor. “Oh, they’re always saying things like that, aren’t they?” was the reply. On the day the USSR ceased to exist, it didn’t even make the BBC headlines.

For the last three years, Roxburgh has been living in Edinburgh, writing this memoir and working on a number of other projects – including writing some rather excellent songs (check them out on YouTube). But if he were back in Russia, I ask, what would he want to be reporting on now?

“Same as everyone else, I think – the crackdown on human rights, the threats to internet use… At the moment, the authorities could switch off whole sites at a time. They could do that with political sites at any time if they wanted to. Young people don’t watch the propaganda rubbish that goes out on Russian television, but they do watch the internet. You can go on the Moscow Metro, log onto the free wi-fi, and log onto as much anti-Putin material as you want.” True, the internet was a big factor in the spread of anti-corruption demonstrations organised by opposition leader Alexei Navalny across the country earlier this year, but Roxburgh reckons that they are no real threat to Putin, who will next year easily be re-elected for another six-year term, when he will try to find a successor who won’t turn against him “the way that he himself turned against Yeltsin”.

What, then, about the notion popularised last year by British general Sir Richard Shirreff in his book 2017: War with Russia, that an expansionist Russia will follow its invasion of Crimea and incursions into Ukraine by moving into the Baltic states, ostensibly at the request of their Russian minorities?

He smiles. “That’s all greatly exaggerated by the people there and by Nato. I don’t think that’s remotely in Putin’s mind to invade. He may be adventurous, but he is not crazy. Firstly, they are members of Nato, secondly the Baltic states were never part of Russia. Of course, there are parts of western Latvia that are practically 100 per cent Russian. Last year there was this notorious film on the BBC which postulated that if there ever was a war, this would be where it would start, and that the Russians there would demand that their troops come over the border to help them.

“Well, this summer we went there as part of our first political study tour of the Baltic republics, and we went to that part of Latvia. The people there just laughed at the idea. The fact is that people in Latvia have a much better life than they would in Russia. They are members of the European Union with all of its benefits. Why on earth would they want to be invaded by Putin? It’s just not going to happen.”

Understanding Russia, he says, is easy enough. All you have to do is to put yourself in their shoes. When you do, you see a country facing an alliance that spends ten times more on defence, facing what it sees as US meddling in Ukrainian elections and encirclement. Add that to a history of civil war, collectivisation, purges, unimaginable brutality in the Second World War, more purges, and more economic brutality as with the arrival of capitalism. “If you don’t understand what the Russians have had to suffer, and what they have been through in the last 100 years,” he says, “you’ll never understand why they feel they need a strong leader who they think will defend them.”

Roxburgh has spent a lifetime understanding Russia, and it shows on every page of his engrossing memoir. The next time he’s in Nizhny Novgorod, somebody should tell that police inspector not to go arresting the wrong guy all over again.

Moscow Calling by Angus Roxburgh is out now published by Birlinn priced £17.99.

New Writing Scotland is an annual volume publishing poetry and prose by both emerging and established writers. Featuring pieces published in print for the first time, the anthologies are drawn from a wide cross-section of Scottish culture and society. Here we present a short story, in full, by Kelso-based Lis Lee, taken from the newly published edition of New Writing Scotland 35: He Said, She Said, I Said.

Extract from New Writing Scotland 35: He Said, She Said, I Said

Edited by Diana Hendry & Susie Maguire

Published by ASLS

Road Ending

By Lis Lee

Baseball glove or brown owl? I flinched though I was inside my car. It was an owl, pitching sideways over caramel winter bracken. I

braked, pulled into a passing place, turned off the engine, wound down my window, inhaled ozone. Once it made me dizzy. Visiting years later, I remembered.

An old man used to live close to this place on a raised beach, a chin on the west face of the island. Blackhouse ruins bristle here, stubble on a turf cheek. The man had a pet owl. That was the craic after the burial. We hadn’t known about it until he died. Duncan Mhor would mount guard at his road end, a scarecrow wearing a hat, earflaps akimbo like a cormorant’s drying wings. His greatcoat was belted with twine and his army boots had no laces. He would adze down the hooked, fractured path from his cottage, whatever the weather and stand, staring one way then the other.

His road end was where I saw him when I drove past to my own slice of bog. Tar whelks pinned his track to the single-track road alongside a gravel bar where road menders took their break and leaned for tea.

His marshmallow house gripped hill rock with split log toenails, softened in Atlantic rain baths and long past the dryness for burning. The house wept roof slates and shed shards of whitewash. It seemed to be melting. Sash windows boxed postcard panoramas of a loch whose mouth spat rock incisors and bit the island almost in half.

Duncan fought in the Second World War and returned to become a recluse. It was public isolation. The island hinted signs of occupation in children who keeked out of doorways and men who rode tractors on never-level fields. Caravans were home to the homeless; broken down cars, windows punched out, were kennels to the kennel-less. Washing lines of nappies gave away secret women when rain held off. Herons with legs like scissors still share spring tide shores with hunched gatherers, Quasimodos turning over rocks and searching with cold, wet fingers for apocryphal heaps of whelks that might be swept up with a broom. Aye.

Duncan never married. He stopped working the croft after the war. His parents had died. Ribs of ragwort bearing a dusting of gold medals were easy in his fields. Lichen-mapped boulders huddled in low heaps, wall duty done.

A cockerel with a crow-green tail and a few toffee hens used to feed on the hill with black-faced sheep and dun rabbits on summer days. The hens roosted among wee purple ballet-dancers in a fuchsia hedge that clung with stout brown arms to a grey wall. In the old garden, rare pink montbretia poked from a sphagnum loofah. The birds perished, their foolish roost a larder for polecats the colour of badgers.

I called at Duncan’s from time to time and left him eggs from my own hens. I repaired the green wooden mailbox at the road end so that his bread and cheese, left by the travelling grocer, stayed dry and were safe from sheep and ravenous sheepdogs. They eat shit, a New Age traveller told me. I knew. If the old man hadn’t been seen by anyone for a few days I climbed the hill. Duncan never invited me in. I satisfied myself that he was upright, dressed and pink.

On a January day, when he hadn’t been seen at his post for a week, I tacked in stiff oilskins through horizontal sleet and chapped at his door. There was no answer so I pushed my way in. Duncan was slumped in a sagging armchair, wearing his greatcoat and hat. His boots lay on their sides on a cold range, rows of nail heads in the soles like a currant grin on a gingerbread man.

The room was freezing and smelled of mould. A table was frosty with used crockery. A bed in one corner was undressed, the mattress gaudy with sepia stains. A high tide of blankets congealed on the linoleum floor.

Duncan was gasping, his eyes closed. The skin on his cheek was cold as sand. I dragged a blanket over and as I was wrapping him I heard a shifting, a soft-shoe shuffle in the hall. It was an owl, set on the banister, an ill-placed piece of taxidermy with real eyes. Guano was cemented to the floor below. Chipolatas of fur, embedded with small teeth and bones, lay about.

I opened the door to the white outside and clapped my hands. The owl looped down with a dry snap, brushing my face, and for a

moment was framed like a crucifix in the doorway.

The sun shone the day we sank Duncan. The granite church was built on bedrock lapped by bog. Gravestones heeled over. Waterlogged topsoil gagged on coffins. Grass paths would rise and fall, tamped down by mourners’ feet. John Smith’s grave on Iona was just the same.

The wake was held in a neighbour’s kitchen. Winter woollens were steaming over an oil-fired range. We talked about old Duncan, Duncan Mhor, the Gaelic speaker who went to war and came back broken. Befriended an owl. Aye.

Lis Lee trained as a journalist. Her poetry, drama and prose have appeared in various anthologies and journals, including New Writing Scotland. She lives and works in Kelso, in the Scottish Borders. Her most recent poetry collection was Vanilla Summer, published by Dionysia Press, Edinburgh.

New Writing Scotland 35: She Said, He Said, I Said is out now published by ASLS priced £9.95.

The twentieth-century Scottish Renaissance saw a sudden and dramatic change in Scotland’s literary landscape. Beginning in the 1920s, Scottish writers increasingly engaged with contemporary social and political issues, and with questions of national identity. An integral part of this development was the radically new literary status accorded to the Scots language. This poem by William Soutar is emblematic of the themes that this dynamic collection highlights.

Extract from A Kist o Skinklan Things

Edited by J Derrick McClure

Published by ASLS

The Makar

By William Soutar

A Kist o Skinklan Things, edited by J Derrick McClure, is out now published by ASLS priced £14.95.

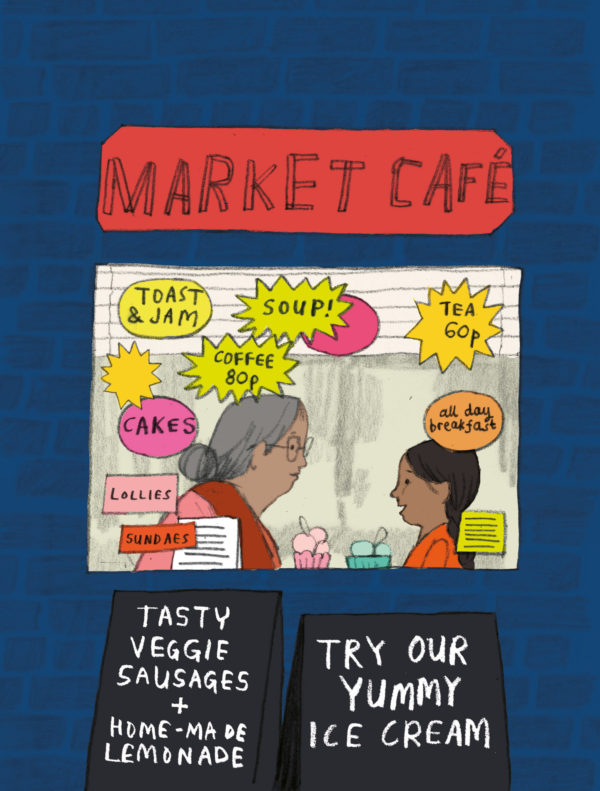

Artwork from Mint Choc Chip at the Market Café

By Jonathan Meres with illustrations by Hannah Coulson

Published by Barrington Stoke

Mint Choc Chip at the Market Café by Jonathan Meres and Hannah Coulson is the latest addition to the popular Little Gems series for early readers and explores the very special bond between young children and their grandparents. Priya loves helping out at her family’s market stall. She spends her Saturdays rummaging around the market with her friends. But one day she meets Stan. His dad sells everything from dog treats to fish tanks – just like the Sharma family! Priya is horrified that their family stall could be in danger, but Nana-ji is on hand to offer a life lesson – over a bowl of ice cream, of course. The book is beautifully illustrated in colour by Hannah Coulson.

Mint Choc Chip at the Market Café by Jonathan Meres, illustrated by Hannah Coulson, is published on 15 October by Barrington Stoke priced £6.99.

Orkney’s Italian Chapel, on the island of Lamb Holm, is unlike any other building in Scotland. Lovingly and resourcefully built during the Second World War by Italian prisoners of war, this extract invites you to voyage north with the bestselling author Alexander McCall Smith as he visits this remarkable historic site.

Extract from Who Built Scotland

By Kathleen Jamie, Alexander McCall Smith, Alistair Moffat, James Robertson and James Crawford

Published by Historic Environment Scotland

Far From Home: The Italian Chapel by Alexander McCall Smith

I went to the Italian Chapel on the Orcadian island of Lamb Holm on an egregiously raw spring day. Orkney is well known as a place of winds, and that week gales had roared in from the west, lashing the Pentland Firth into a maelstrom of angry waves. These gales lasted for several days, with only occasional periods of calm while the weather gods regrouped for a fresh onslaught. Going through my mind was that irredeemably dyspeptic poem by a naval officer, Hamish Blair, posted to Orkney during the Second World War. Entitled ‘Bloody Orkney’, it is a rant against everything in Orkney, including the weather, and includes the memorable lines: ‘All bloody clouds, and bloody rains’. Blair was obviously a churlish guest of these charming and friendly islands and would seem to have deserved the anonymous reply penned by one of his Orcadian hosts: ‘Captain Hamish “Bloody” Blair / Isna posted here nae mare / But no-one seems to bloody care / In bloody Orkney.’

Hamish Blair would have been dispirited by the unrelenting gales, but I found that even if they made being outside a challenge, they had a spectacular impact on the landscape. Perhaps Orkney, beautiful though it may be on a fine day, comes into its own in difficult conditions; it is a place of high winds and turbulent seas; it is a landscape of flattened hillsides and bent, discouraged trees. This is not Highland Scotland, but something quite different; it is a halfway house to Scandinavia, where low-lying islands and a cold sea are the backdrop to daily life.

I drove down from Kirkwall on the road that runs to Scapa Flow. It was too early for lambing, and the sheep were standing about waiting for their time to come, indifferent to the winds to which they were so accustomed. The farmhouses along the side of the road, like many of the buildings on the island, had a low, huddled look to them, as if they were keen to burrow back into the protective earth. Had they been brochs, rather than houses, they would not have seemed out of place.

Orkney Isles scheduling team work trip. Record images of the Italian Chapel, South of Orkney mainland, by the Churchill barriers

The road ran straight, even if it went up and down as it followed the gentle folds of the Orkney countryside. No journey in Orkney is all that long, the blessing of an island being that it is, usually, a place of short distances. Such a landscape never suffers from the loneliness that can infect those that go on forever. The American West and the Australian Outback are melancholic places because of their distances. Orkney is not like that at all; it may be relatively sparsely populated, but I suspect it would be hard to be lonely there.

The road ends where the sea begins, and you turn off, should you wish, to make the journey over the barriers to one of the outlying islands, to Burray or South Ronaldsay. That route is hard in these windy conditions, as the sea is whipped into plumes of spray as it meets the sides of the causeways. But I did not have far to go, as my destination was just over one of these causeways, on the island of Lamb Holm, and I could already see the squat, white-fronted building, so tiny in the distance. The Italian Chapel. And next to it, energetic in the gale, the Italian flag. Again, a line of a poem came to my mind, and I thought of Auden’s description of a flag in the wind in his ‘Journey to Iceland’. He describes a flag as ‘scolding’, and it seemed just right. Here was the Italian flag, scolding in the wind.

I crossed the barrier and stood before a building I had seen many times before in photographs. It was so small, as buildings – and people – so often are when you seem them in the flesh. But it had such presence that it would have seemed wrong for it to be any bigger.

I went in.

Who Built Scotland: A History of the Nation in Twenty-Five Buildings, by Kathleen Jamie, Alistair Moffat, Alexander McCall Smith, James Crawford, and James Robertson, is out now published by Historic Environment Scotland priced £20. If you’re in the St Andrews area you can join authors James Crawford and James Robertson at this event at Topping and Company bookshop on 10 October.

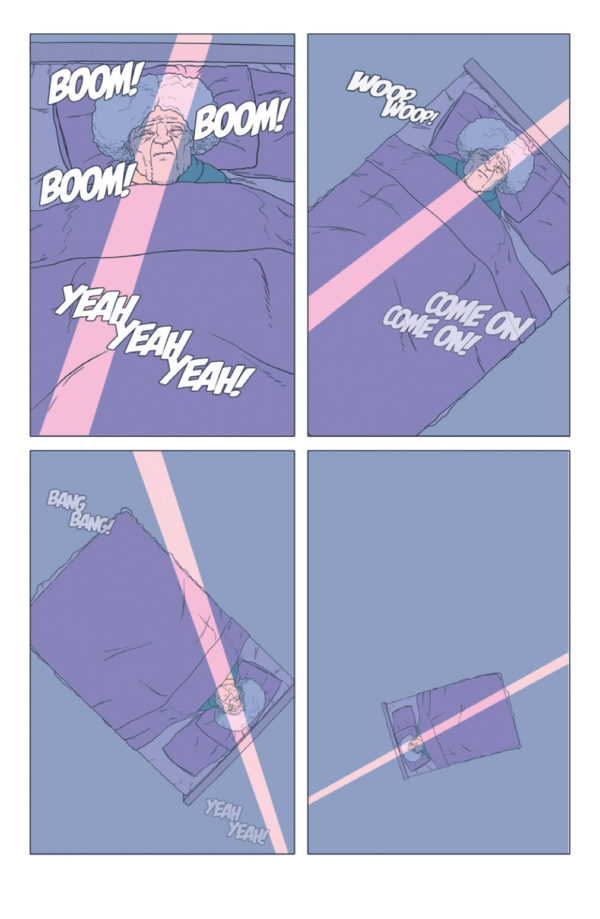

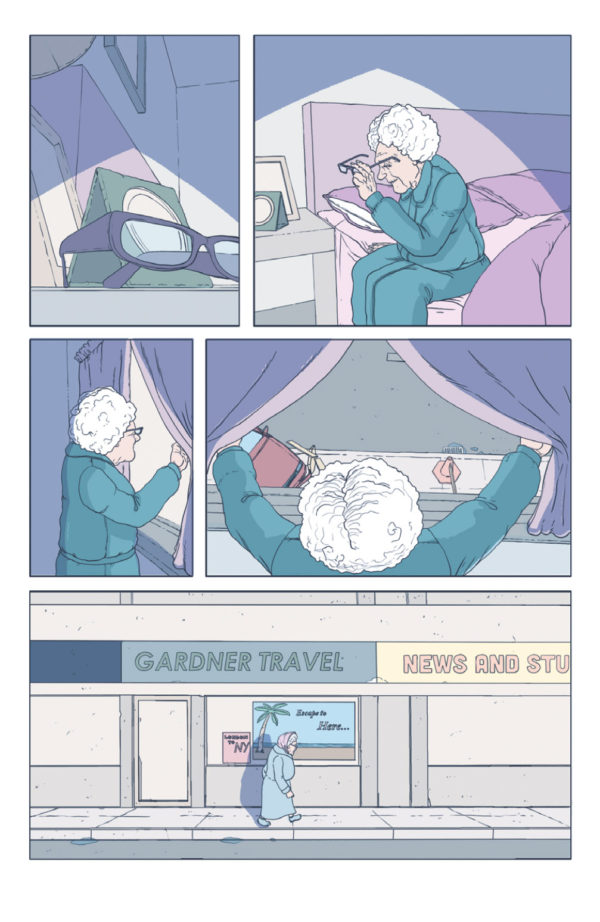

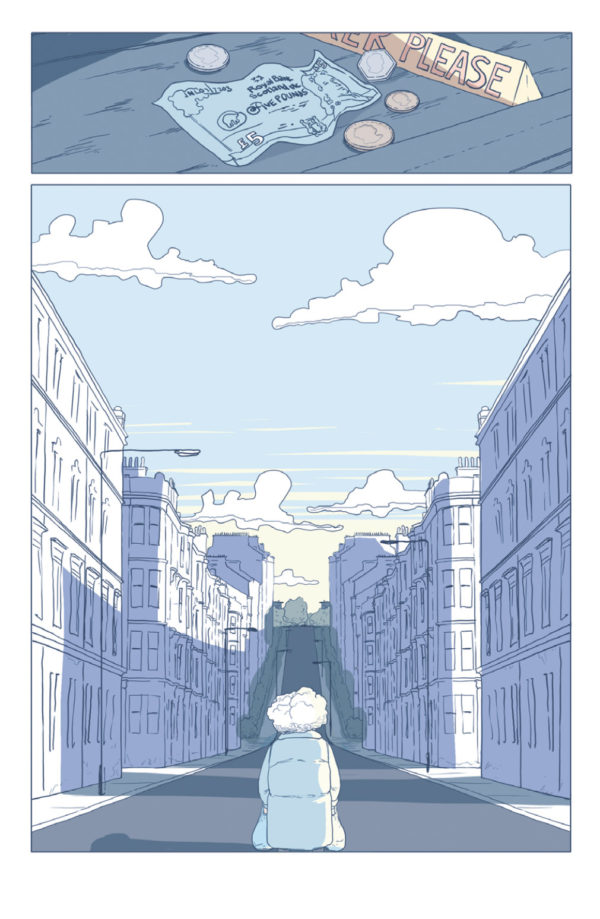

When an old lady wakes up one morning to find the rest of the world has disappeared, she struggles to cope with the isolation. But perhaps she’s not as alone as she thought… This new graphic novel tells a universal story with some recognisably Scottish scenes in the artwork by acclaimed artist Gerry Mac.

Extract from Tomorrow

By Jack Lothian and Gerry Mac

Published by BHP Comics

Tomorrow by Jack Lothian and Gerry Mac is out now published by BHP Comics priced £7.99.

Meet Maggie, who hates her new mittens. Maybe she can find them a new owner on her trip around Scotland… somewhere Mum won’t notice! Join Maggie – and her mittens – on this charming tour of Scotland. Click below to preview the first few pages of this delightful new story.

Maggie’s Mittens by Coo Clayton and Alison Soye is published by Black and White Publishing on 12 October priced £6.99.

William MacGillivray was Scotland’s foremost 19th century ornithologist. Aged just 21, on the verge of his career as an outstanding naturalist and bird artist, he left Aberdeen to spend a year at his childhood home at Northton on the Hebridean island of Harris. In that year he kept a detailed journal that provides a rare insight into rural life in Scotland.

Extract from Travels With A Hebridean Naturalist

By William MacGillivray

Edited by Dr Robert Ralph

Published by Acair

North Town, Tuesday, 14th October, 1817

On Sunday, the 5th, I left Luachar about mid day. As the deer lay near the way I intended to take, I proposed to decapitate them, & carry the spoils on my back to North town, and this I did. Ewen accompanied me as far as Strom nan Scurt, a prodigious rock in the pass of Miavag. Between this and Tarbert, the road, or rather rout, for there is scarcely any appearance of a foot path, lay over hills and heaths, rivers and bogs. The Common Ling is the predominant plant in these regions. The sun had set before I reached Tarbert, and night fell long before I attained the summit of Benluskentir. In course I made but slow progress upon the hill; and it was after twelve when I found myself seated upon a chair in my bedroom at North town.

On the evening of Monday the 6th word came from Rodell that Miss Jessy Macdonald of Ord, a cousin of Mrs McGillivray’s, had arrived from Skye, my uncle in consequence went to meet her. I should have gone, had not my late journey put me completely out of trim. Mr Finlay MacRae came to the house in the dusk. The evening was spent agreeably. We conversed upon poetry and religion, and drank a little Rum punch.

On Tuesday, the 7th, my uncle arrived in the morning with Miss MacDonald, and Mr Finlay departed. After breakfast, I accompanied my uncle to Ard Nisbost, where there was to be an exhibition of stallions. Here I saw Messrs Stewart, Torrie, McKinlay, D. McLellan, Archd. Stewart & McLean the schoolmaster. Stewart gave me leave to shoot a deer. My uncle, the Doctor, and I are to form a party, on our way we called at Borve.

On Thursday, the 9th I was sent for by Duncan MacLellan of Ensay to visit a sick servant of his. As my uncle was anxious that I should go, I gave my assent. On the way I met my aunt MarciIla, with two of her children, from Glasgow. On arriving at Ensay I found a robust woman in her bed, senseless, motionless, speechless – pulse regular, slow and weak, breathing apparently easy. She had been but lately delivered of her first child, had gone out the evening before, taken milk at the fold, returned, sickened and complained of intense pain in her head. She had not spoken since ten o’ clock of the preceding night, a lancet was thrust into her arm and about eight ounces of blood obtained. Shortly after she revived, spoke quite sensibly, recognized her friends, said she felt easy, excepting that she had a slight pain in her forehead. By the bye, a little gruel and whisky with caraway seeds had been given immediately after the bleeding. About nine at night she became delirious, and ten or twelve ounces of blood were taken. This again restored her to her senses. I lodged with Duncan – we played at cards. On the morning of Friday I got over to Kyles in Archibald Campbell’s boat, and reached North town about nine o’ clock.

On Saturday, the 11th my uncle and I sailed through the islands of Ensay on our way to Berneray. He shot a sea bird, and we landed on a sand bank where I obtained specimens of shell fish. In the evening we reached Kyles of Uist. The family here consists of Mr & Mrs McNiel, Masters William & Ewen and Miss Mary – The good man is a polite, well-formed, agreeable man, about fifty – He is suspected however of dishonesty, and does not bear a good character in regard to equity and humanity. Mrs McNiel is of the same age, has a curious phiz, (face) semicircular in profile, a rough voice, and not very agreeable manner – though she is said to have been handsome. This I deny: for her face, and person are quite at variance with the laws of proportion. Miss Mary is a pale faced, wry-necked, ackward girl – poor creature! She looked like one dying of love, or troubled with amenorrhoea. As to William & Ewen, the latter is a boy, the former a gigantic raw-boned, rough, illiterate, impolite yet good hearted: and possibly honest fellow.

On Sunday, some business brought my uncle to the preaching – at about three miles distance from Kyles. Mr MacNiel and I accompanied him. Mr MacRae preached. The meeting house was thatched: yet having some good seats, and being well filled with a very decent and well-dressed congregation, appeared far superior to our parish church in Harris. After sermon Mr MacRae treated us with a mutchkin of aqua-vita. We returned in the evening. Mr MacNiel and my uncle retired to a tippling house at Kyles, while I walked into the parlour or dining-room, for it is both. Here I found Mary, and spoke a little to her.

Travels With A Hebridean Naturalist by William MacGillivray is out now published by Acair priced £15.00.

Kasia Matyjaszek is the illustrator of The Fourth Bonniest Baby in Dundee, which has just been shortlisted for the Scottish Book Trust’s Bookbug Picture Book Prize 2018. But who is Floris Books’ latest prize nominee? Kasia’s publisher introduces the illustrator behind messy (but adorable!) babies and Dundonian streets.

Who is Kasia Matyjaszek?

Kasia is an Edinburgh-based freelance illustrator. Along with illustrating The Fourth Bonniest Baby in Dundee and This Bonny Baby for Floris Books, she’s worked with Barrington Stoke, Ladybird Books, Templar Books and publishers Dwie Siostry Publishing and Wysokie Obcasy Extra in her native Poland.

Her illustration career so far

After starting her first career in architecture, Kasia decided to swap blueprints for brushes. She graduated from the Edinburgh College of Art with an MA in Illustration, and now works there as an illustration tutor. When not teaching at the University of Edinburgh, Kasia runs creative workshops for young children.

She was destined for illustration

Kasia recalls drawing avidly as a child. Once her teacher sent a note to her parents saying, “Kasia did not listen during class. She drew silly drawings in her notebook and laughed at them.” She’s now proud to make a living by her silly drawings!

No stranger to prizes

To help establish her reputation as a children’s picture book illustrator, Kasia submitted artwork for illustration competitions. She was highly commended in the Macmillan Book Prize and a finalist in both the Picture Hooks mentoring scheme and Clairvoyants picture book competition. Now, she’s shortlisted for the Bookbug Picture Book Prize 2018 with The Fourth Bonniest Baby in Dundee, AND she created the Scottish Book Trust’s competition artwork for next year’s prize.

Kasia’s process and methods

She experiments with various media, tools and ways of making marks. For both The Fourth Bonniest Baby and This Bonny Baby, she made lots of paint splats by standing on her desk and dropping ink onto a piece paper on the floor. She admits she missed a few times before coming up with perfect splats! She then finishes off using digital methods, what she calls “the tidying up after all the messy fun!”

Perks of the job

Kasia loves promoting books and meeting audiences in schools, libraries and festivals. She says “Illustrating can be a lonely process, where the artists spends a lot of time with imaginary characters. It’s great to get out of the studio from time to time and work with real people!”

Favourite things to illustrate

Crocodiles, dragons and confident girls.

Her inspiration

Kasia lists her main inspirations as naïve art, social realism, and mid-century design. She also loves the new ideas sparked by drawings and comments made by children she meets at her illustrator events.

Her top tips for illustrators

Don’t feel the need to work in sequence – if you get stuck just move on to a different illustration and then go back to the problematic spread when you’re ready. Take a day off, go for a walk or for a long cycle, ideally somewhere close to the sea; all of the good ideas are at the bottom of the sea just waiting to be discovered!

This Bonny Baby, a mirror board book, by Kasia Matyjaszek and Michelle Sloan is out now published by Floris Books priced £5.99.

In this exclusive article bestselling children’s author Lari Don muses upon endings – both in her writing and in the changing seasons – as the final instalment of her exciting Spellchasers trilogy is published. And, like the changing seasons which lead onto renewal and growth, she finds that endings should be embraced as they are an essential, and indeed joyful, part of the creative process.

A Season of Endings

By Lari Don

Autumn is about endings. About leaves falling and all the growth of spring and summer fading away.

I’ve been thinking a lot about endings recently, because the third book in my Spellchasers trilogy (The Witch’s Guide to Magical Combat) has just been published.

The end of a story has to be perfect. Of course, getting the beginning right is important, to hook the reader. But getting the ending right is vital. The end of a book creates the feeling that the reader takes away, the last memory and enduring sense of the story. If the ending doesn’t work, the story hasn’t worked.

From a practical point of view, if the ending isn’t satisfying, the reader won’t want to read your next book, or recommend this one to anyone else!

From a creative point of view, if the ending doesn’t answer the question asked at the start of the story, what was the point of everyone – writer, characters and reader – going on the journey?

Like almost everything else to do with a trilogy, writing the ending is a lot more complicated than writing the end of just one novel. In a trilogy, the third book is the ending, but it also has to be a story in its own right.

Lari Don

As I worked on the third Spellchasers book, I was conscious of trying to ensure that this novel’s purpose wasn’t just to tie up previous plot lines. I did resolve those storylines, but I also introduced a new character (who’d been in the other books, but hiding in the background), new magical powers and dangers, and a new baddie (who’d also been in the story before, hiding in the foreground…)

I wanted Witch’s Guide to feel like a continuation of the Spellchasers story, but in a new and surprising way.

I aimed to write a story with its own shape and flavour, but also bring the wider story of the whole trilogy to an end.

And because I write adventures for kids, I didn’t want all my effort and structuring and resolving to feel heavy or overthought or obvious to the reader. So I threw in a few chases and fight scenes, and a bit of shapeshifting…

I had fun writing a third adventure with a team of characters I love. But I knew I had to finish it. I had write a last battle. A last problem. A last chapter. A last page. A last line.

And I hadn’t been writing towards that last line for a year, like I had with my other novels. I had been writing towards that last line for more than three years.

The trilogy turned out to be about a choice, about how my main character – who began the trilogy cursed to turn into a hare, but found the ability to control her shapeshifting – would decide to use the magic she’d discovered.

I thought I knew, right from the first page of the first book, what she would choose, how her magical journey would end. But in the final quarter of last book, I realised Molly’s attitude to magic was becoming very different to my attitude, and she was moving towards a different decision. I was happy about that, because the resolution of a story has to fit the character. (Especially if you’ve spent three years and three books bringing that character to life!)

But when we leapt into the last battle and neared that final decision, Molly and I together found another option entirely, one which hadn’t occurred to me earlier. Her decision surprised me, so I hope it will surprise the reader as well…

Most of all, I hope it will be satisfying. I hope it will feel like the perfect end.

So I’ve reached the end of my time with this trilogy and these characters. I’ll read from the books at festivals and in schools, and answer readers’ questions about their favourite characters. But I’ll never write about them again. I won’t send them on quests, or put obstacles in their path, or wonder what surprising decisions they will make when I confront them with danger. I’ve reached the end of my journey with the Spellchasers team.

And that goodbye is a very autumn sort of a feeling…

But, just like autumn and winter lead to spring and summer, and new life stirs under fallen leaves, I hope the beginning of the next story is starting to grow slowly and tentatively in my head.

Because the end of a story is important, of course it is, but perhaps the start of the next story is even more exciting?

Lari Don’s new book The Witch’s Guide to Magical Combat has just been published by Floris Books. Find out more about the Spellchasers trilogy, visit Lari’s website or find Lari on Twitter.

You can read many more articles by Lari on Books from Scotland – have a look here.

Offering an alternative version of the history of modern Scottish art, this book challenges the accepted view of the dominance of the Scottish Colourists and the influence of France, by examining the most progressive work made by leading and lesser-known Scottish artists. Three important modernist artworks are introduced below, alongside expert commentary, ahead of the major forthcoming exhibition.

Extract from A New Era: Scottish Modern Art 1900-1950

By Alice Strang

Published by National Galleries of Scotland

Edward Baird, The Birth of Venus, 1934. Oil on canvas, 51 x 69 cm. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh: accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, 2002. © Graham Stephen.

This is a rare example of Scottish Surrealism. It was painted as a wedding present for the artist James McIntosh Patrick and his wife, who were married in 1934. McIntosh Patrick said of Baird’s gift, ‘It rather shocked me as he painted so few pictures yet he gave this one away. He was our best man and, being a sentimental person, he chose Venus, the goddess of love, as the subject of the painting. He was a keen Scottish Nationalist; he also admired Botticelli and Crivelli. Hence the “Scottish Venus” as he called it, arose out of his associations with a wedding, his involvement with Scottish Nationalism, his love for messing about in boats, and his love of Botticelli.’ The grey filters, mirror and circular plate in the top left of the painting belong to a sextant. The woman, presented on the beach at Montrose, is Ann Fairweather, Baird’s fiancée and later (from 1945) wife. When the painting was exhibited in Montrose in 1935, the Montrose Standard noted: ‘This is in the type of the school of Surrealism, and supporters of this school will recognise its beauty and splendid detail’.

[Patrick Elliott]

Robert Burns, The Hunt, c.1926. Oil or tempera and gold leaf on canvas, 198.1 x 198.1 cm. Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh: purchased 1987.

This painting was produced as part of the commission for Crawford’s Tea Rooms in Edinburgh and was originally a panel fitted into a staircase. The previous title of the work was Diana and Her Nymphs, but – as none of the traditional attributes of the goddess (the moon, bow and arrow), which Burns was always careful to include in his other depictions of Diana, are present – it was later renamed The Hunt. An adaptation of the female figure at the centre of this work featured on biscuit-tin labels for William Crawford & Sons. A separate panel (now lost) was titled Diana the Huntress and is thought to have related to this work, indicating that the figures here may be followers of Diana. The animals depicted in this vibrant panel have been identified as white-headed capuchin monkeys; a magpie tanager; and ocelots or ‘dwarf leopards’. A personal touch by the artist is the small green car at the bottom: a nod to his passion for motoring.

[Claire Walsh]

William Crozier, Edinburgh (from Salisbury Crags), c.1927. Oil on canvas, 71.1 x 91.5 cm. National Galleries of Scotland: purchased 1942.

William Crozier was born in Edinburgh, the second of four children, and grew up in the Marchmont area of the city. His father was a printer’s compositor for Thomas Nelson & Sons. Both William and his younger brother Thomas, were haemophiliac, so certain constraints were placed on their lifestyles. Crozier gained a bursary for George Heriot’s School in Edinburgh and at the age of sixteen went to work for the North British Rubber Company. Working life was always something of a struggle for him because of his condition, which meant that even the slightest knock could cause serious internal haemorrhaging, and he soon turned to painting as an occupation he could maintain at his own pace. […]

Being a little older than his friends, Crozier’s influence can be seen in much of their earlier work, and he has been an overlooked presence in the Edinburgh School perhaps due to his early death at the age of only thirty-seven. Crozier died in December 1930, after a fall in his studio which caused a cerebral haemorrhage. He had been elected as an Associate member of the RSA in March of that same year.

This view of Edinburgh from Salisbury Crags clearly shows the lessons Crozier had learnt from his time studying with André Lhote in Paris. Lhote favoured a cubist approach to formal composition, where the subject is simplified into cubes, cylinders and cones, as famously described by Cézanne. While still anchored in realism, the synthesis of Crozier’s Edinburgh, seen from a viewpoint along the Radical Road, owes much to his experience in Paris but also nods in the direction of S.J. Peploe, an artist whom Crozier knew and greatly admired. The high viewpoint allows Crozier to take full advantage of the strong northern light across the city, with the dark mass of Edinburgh Castle in the background.

[Kerry Watson]

A New Era: Modern Scottish Art 1900-1950 by Alice Strang will be published in January 2018 by National Galleries of Scotland. The book accompanies an exhibition to be held at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh from 2 December 2017 to 10 June 2018.

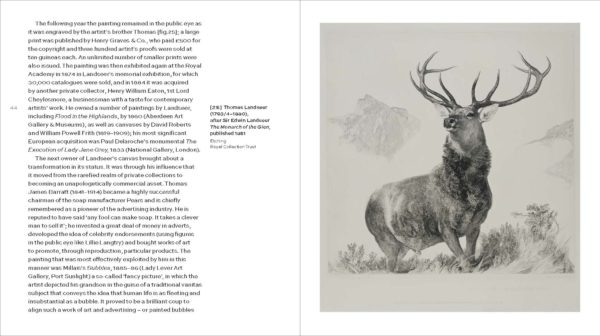

Many view Landseer’s The Monarch of the Glen as an iconic painting of, and from, Scotland. But the story of the painting is not without controversy, as Christopher Baker reveals in this illuminating introduction, which sketches the historical and contemporary context of this much-loved artwork.

Extract from The Monarch Of The Glen

By Christopher Baker

Published by National Galleries of Scotland

[Landseer’s] greatest enjoyment was to wander in the lonely glens, or climb to the steep mountain-top, in search of that nature, animate and inanimate, with which his heart was in accord, and there it was that he derived the inspiration which prompted the greater part of his noblest productions.

– Obituary from The Report of the Council of the Royal Scottish Academy of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, 1873

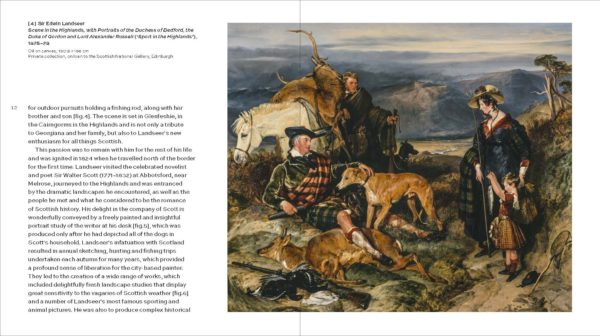

Sir Edwin Landseer, The Monarch of the Glen, c.1849–51. Oil on canvas, 163.8 x 168.9 cm. Scottish National Gallery Edinburgh.

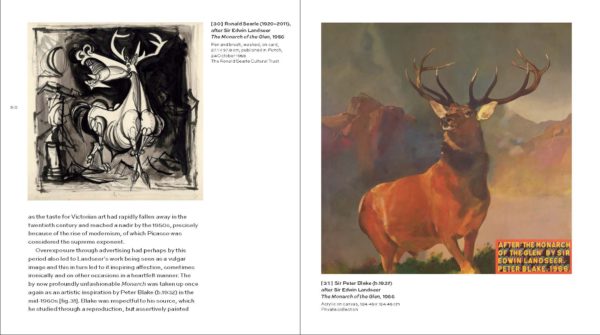

Few British paintings of the nineteenth century are as instantly recognisable as The Monarch of the Glen. It has so often been reproduced that it has become part of our shared visual memory. This familiarity means that it’s hard to look at it afresh; that is, however, precisely what this book sets out to try and do, by placing the painting in the context of the career of the highly-accomplished artist who created it and considering some of the many different and contradictory interpretations it later inspired. These have ranged from it being seen as a splendid technical achievement and a romantic evocation of Scotland’s wildlife, to it being viewed as an archaic image and an irrelevant aristocratic trophy. Through endless reproduction it has also almost become a kitsch icon, in a way that would have been inconceivable to Landseer and his contemporaries.

Today Landseer is not a household name. However, he was one of Victorian Britain’s most successful and fêted artists. The breadth of the appeal of his work as an animal painter is hard to recapture – it transcended class distinctions and had a global reach. His paintings were deeply admired by Queen Victoria and could be found reproduced in prints displayed in modest homes across Britain and its empire around the world. The drama, sentimentality and often sophisticated exploration of the complex interaction between people and animals found in his works, struck a chord with millions. Through the twentieth century, however, many aspects of Victorian culture were dismissed as outmoded and an impediment to progress: this included paintings of the period, which languished in gallery storerooms. The Monarch of the Glen intriguingly survived this fundamental shift in taste, as it had taken on a new role, being employed as a highly successful marketing image; as such its fame probably extended even further, although the original circumstances of its commission were long forgotten. It now has a complex and fascinating status in an age when Victorian art has been reassessed by scholars and is widely admired once again, but the élite associations that Landseer’s Monarch conjures up are challenged as being at odds with some modern values and contemporary views of Scottish nineteenth-century history. […]

In March 2017, 166 years after it was painted, Landseer’s Monarch of the Glen finally became a public possession, when it was acquired by the National Galleries of Scotland.

It seems especially appropriate that it now has this status, as for much of its life the picture has played a role in British and Scottish popular culture, being so often reproduced and ‘owned’ at least by proxy by so many people, whether through engravings or in connection with whisky bottles.

The painting now poses a key question: is it still fitting to promote a work by an English artist who conformed with aristocratic taste, which is clearly cloaked in a romantic view of Scottish culture, as relevant in the twenty-first century? This is an especially compelling issue at a time when Scotland is defining a strong role for itself as a distinctive, modern, democratic and technological nation. Some will undoubtedly conclude that the painting is an anachronism. Others will want, however, to continue to celebrate the picture because of Landseer’s remarkable artistry and the way in which it symbolises the natural wonders of the country. What is certain is that his work has retained a powerful quality of recognition and been able to take on a wide range of different roles and interpretations, often simultaneously. It will now be seen by more people than ever before and new debates and artistic responses will undoubtedly develop around it. These may well focus on another fascinating issue: whether the painting fits into the narrative of Scottish art? In answer to this, perhaps it is helpful to view The Monarch of the Glen as an important example of Scotland’s art – a more inclusive description which accommodates the work of painters from across Europe and beyond who have contributed to the rich imagery that has come to be associated with the nation.

The Monarch Of The Glen by Christopher Baker is out now published by National Galleries of Scotland priced £9.99. The spreads featured above are all from this book.

From Roman pay-offs to Pictish treasure, silver has long been the currency of Scotland. Ahead of the major National Museum of Scotland exhibition, this extract examines why silver – rather than gold – has provided the most valuable clues in furthering our understanding of social change from Roman through to Victorian times.

Extract from Scotland’s Early Silver

By Alice Blackwell, Martin Goldberg and Fraser Hunter

Published by NMS Publishing

Silver, not Gold

Silver was the most precious metal in Scotland for a thousand years. This book tells the story of this powerful material during a pivotal time, from the arrival of the Roman army until the dawn of the Viking Age, 700 years later. We trace silver through changing times, as Roman Iron Age tribal societies gave way to a patchwork of Early Medieval kingdoms. Silver provides a valuable path through this period of transition and social change, a time when historical sources give us few clues and where a firm archaeological footing is rare.

Hunterston Brooch

Silver first arrived in Scotland with the Roman army in the 1st century AD. Handfuls of silver coins – a soldier’s pay packet – and precious dress accessories were the earliest silver objects used in Scotland. From these small beginnings grew a new social order, built on the haves and have-nots, those with and without silver of their own. One hundred years of Roman frontier policy brought substantial quantities of silver coins to the north, gifted to buy off Iron Age tribes beyond their borders. These coins had no monetary value beyond the Roman frontier – instead they had prestige, being used to show off and given as offerings to the gods. Hoarded and buried, this silver was not melted down. But crises in the Roman economy in the 3rd century AD meant that ‘silver’ coinage contained increasingly little silver, making it an unattractive gift. Instead, hacked-up high-quality silver objects, especially vessels, were turned into bullion; and for the first time in Scotland they began to be recycled into new, local types of objects.

This was the start of generations of recycling – the forging of new status symbols. From elaborate Roman vessels a new Early Medieval language of power was wrought, spelled out in massive silver chains and intricately decorated brooches. Worn and buried, hoarded and melted, these objects speak of the transformation of society through the first millennium AD.

Why silver? The answer is a combination of availability and choice. Though the Roman economy relied on gold, Roman foreign policy in Scotland worked almost entirely in silver. This is a sharp contrast with other parts of Europe beyond the Roman frontiers where gold and silver were used to buy ‘barbarian’ allegiance. These different inheritances of Roman metals had implications for what happened next. While in England and on the continent gold became the epitome of Early Medieval wealth and social status, in Scotland silver loomed large. Availability always governed its use, but silver was chosen for local expressions of power.

Taprain Hoard

Silver can be valued in different ways. The tipping point between these kinds of value tells of societal and cultural attitudes. When silver was first introduced to Scotland the scales were firmly tipped in favour of social value: this Roman silver was not treated as bullion, not melted down or made into local types of objects. Around the 3rd century AD, the scales tipped the other way, towards bullion value: Roman silver began to be recycled and remade into new types of objects. From then, those using silver had to make a choice – to preserve a silver object, to recycle it, or to take it out of circulation by burying it. Understanding how, when and why these choices were made can tell us a lot about the political and economic history of Iron Age and Early Medieval Scotland. But these ancient choices also have significant implications for interpreting archaeological silver. In the face of failing supplies in a post-Roman world, substantial ancient recycling has left us with relatively few silver survivals. Very rare hoards give us glimpses of objects that chance saved from the crucible; many are exceptional, even unique.

But this rarity makes understanding objects difficult, restricting our ability to date or provenance key pieces. And the tensions between social and bullion value are not just an issue for deep history. The tipping point between archaeological value and bullion value in the 19th century saw quantities of ancient silver recycled into Georgian and Victorian tableware. Written accounts of the time are the only trace of tantalising treasures lost to the crucible.

This book accompanies a special exhibition, Scotland’s Early Silver, at the National Museum of Scotland (October 2017–February 2018). It tells a new story of an old metal – one which used to be more powerful than gold.

This excerpt is from the introduction to Scotland’s Early Silver by Alice Blackwell, Martin Goldberg and Fraser Hunter, to be published 13 October by NMS Enterprises Ltd – Publishing, National Museums Scotland.

Think you know everything about whisky from A to Z? Think again. Iain Hector Ross brings in-depth knowledge to The Whisky Dictionary, forthcoming from Sandstone Press. Having worked in distilleries, and helped to set up the first legal distillery on the Isle of Raasay, in this Q&A Iain tells us about his road to publication, and reveals some of his favourite whisky terms.

Why whisky?

It all began on an annual ski trip to France in 2013 when an old friend of mine told me he was looking to build a business in Scotland with long term market presence and legacy. We brainstormed a few bright ideas such as reinventing the bunnet for the upwardly mobile urban male and launching a fashion brand for men in their fifties specialising in cardigans. After the third dram we realised we were nursing the ultimate brandable Scottish global product in our hands. Whisky!

Back in Scotland I realised I knew very little about the world of whisky other than as an occasional enthusiastic consumer. I set about learning and understanding the language of whisky. I took a journey into the whisky industry, working in a distillery whilst studying production and researching the archaic words and terms belonging to the whisky makers of another age. Two years later in 2015 I had come so far down the road and collected so many stories, tales and fascinating facts that I realised I was actually writing a book. A book that will never really be finished as long as whisky is made, but a book nonetheless!

Could you tell us a bit about pitching at Xpo North?

In 2015 I had my radio play The Coffin Road broadcast on BBC Radio. I was looking for my next project when Xpo North announced an innovative Twitter event where writers could pitch their book ideas in 140 characters direct to agents and publishers. I pitched The Whisky Dictionary and was invited along to the live event – a sort of Dragons’ Den where each author had 3 minutes to sell their book to a panel of inscrutable publishers. Despite carefully writing out my pitch beforehand I almost immediately went off script and just spoke directly to the panel about my enthusiasm for the project and some of the fascinating words I had already collected. Needless to say, I was delighted to get the call next day from Moira at Sandstone Press who invited me to Dingwall for a chat. Two years later The Whisky Dictionary will shortly be available in bookshops.

Could you tell us a bit about how the publishing process has been for you?

I’ve written a lot of factual and fictional narrative prose over the years. Writing a dictionary is a very different experience in that you soon realise that people will not be reading your work as one storyline. Instead they will pick up and put down, read from the back to front and dive about the pages as the fancy takes them. As a writer, I took had a similar approach. Whilst I laid the book out alphabetically, I didn’t write it as such. Instead it was written in bursts and small runs with the definitions sometimes becoming ‘micro stories’ in themselves.

Then I delivered the final text. The formatting stageand endless reviewing was an education in itself in how demanding a format I’d chosen for someone used to free-flowing prose. Keira and the team at Sandstone were fantastic at schooling me through it, and having the technical and creative skills to nurture the project and see that original pitch through to this beautiful finished work. A bit like a fine single malt, actually.

What came first – the distillery or the book idea?

I’d have to say that confirmation that the distillery was going to happen was the trigger for me as an outsider to turn towards the world of whisky and commit to researching its story and the language which has grown around it.

How did you gather the terms and their definitions?

By talking to lots of people in the industry, cramming lots of notebooks with extracts from Industry textbooks, business archives, attending tastings, visits to distilleries, maltings, working in a distillery and general nosiness about the contents of the endless number of whisky wagons going up and down the A9. I’m still gathering!

Finally, what’s your favourite whisky term and why?

I love the word Skalk. It’s one of these great words that is shared across Scotland’s languages. It derives originally from the Scots Gaelic Sgailc which means a dunt, a skelp or a blow to the head. But that meaning has been appropriated in the context of whisky drinking to mean a bumper dram and in particular a bumper dram early in the day or the occasional Highland indulgence of enjoying whisky for breakfast. In Gaelic, the Sgailc-nid is the first dram of the morning. In fact the -nid means ‘nest’ or more accurately ‘bed’ as it describes a large, generous measure of whisky enjoyed in bed. This Highland custom is perfectly acceptable if reserved for very particular circumstances and special days and was noted in 1783 by Dr Samuel Johnson during his Tour to the Hebrides: “A man of the Hebrides, for of the woman’s diet I can give no account, as soon as he appears in the morning, swallows a glass of whisky; yet they are not a drunken race, at least I never was present at much intemperance; but no man is so abstemious as to refuse the morning dram, which they call a skalk.”

The Whisky Dictionary by Iain Hector Ross is published on 10 October by Sandstone Press.

The island of Little Ross was unknown to most people until 1960 when a murder in the lighthouse buildings brought it widespread notoriety, to the grief and consternation of all who were involved. David R Collin examines how 117 years of devotion to duty, peacefulness and calm, was disrupted forever by a day of inexplicable violence, and reveals how he found himself at the heart of the island’s unusual and disturbing story.

Extract from Life and Death on Little Ross

By David R Collin

Published by Whittles

The writing of Life and Death on Little Ross was inspired initially by a tragic event which occurred 57 years ago, when I was nearly 20 years of age. My late father and I had sailed to Little Ross Island in South West Scotland, close to our home in Kirkcudbright, intending to spend a few hours there for a picnic lunch and then to return homewards in the late afternoon. Our day did not go as planned, for on that remote and beautiful island, we discovered the body of one of the two keepers who manned the lighthouse, and noted the absence of the other keeper. It later turned out that we had discovered not merely a tragedy, but a mystery which was soon revealed to be a murder. The missing lighthouse keeper had shot his colleague in the head while he slept, and had then fled. He was soon arrested and charged with murder, and we later had to give evidence at his trial, which resulted in him being sentenced to death.

Speedwell North East of Ross

The dramatic and romantic setting of the island, combined with public fascination about the lives of lighthouse keepers made this a story, widely reported all over the world, with varying degrees of accuracy. I have often been asked to tell my story, and the frequency of requests increased sharply after the recent 50th anniversary of the event. It is sad for me to realise that I am now one of very few people, or possibly the only one, left alive who played a key role in the events of that day in 1960.

Station from South East

Concerned by the lurid press accounts of the time, I resolved to investigate the entire history of Little Ross Island, and to tell the complex story of the case for there being a lighthouse on it, the struggle to gain its approval, and its design and construction. Many hours were spent in the Stewartry Museum in Kirkcudbright, The National Library and the National Archives in Edinburgh, delving into, among other things, the records of the Stevenson family who were responsible to the Northern Lighthouse Board for the lighthouse’s design and construction. I particularly wanted to describe the lives of all the peaceful and law-abiding keepers and their families who had lived on the island for 117 years and to tell their stories. The resulting tale is predominantly one of romance, dedication to duty, resilience in times of hardship, tenacity in providing good and comfortable homes for generations of children who were born on the island, and observation of the island’s wildlife. All of the former lighthouse keepers have been identified, some have left diaries and articles which have been quoted, and a few people have given invaluable first-hand accounts of their time spent living on the Island.

Tower from South East

The task of writing my book had been completed and my publisher was making excellent progress with its production, when to my great surprise, the owner of the private 29 acre island of Little Ross decided to offer it for sale. The prospect of being able to acquire a private Scottish island for a relatively modest sum of money was given widespread publicity by the press, and when reporters made the link to the past tragedy, the story spread like wildfire to nearly two generations of people who were too young to remember it in its original form. For the second time in its long history, Little Ross Island became a prominent story in newspapers in many parts of the world. The island and I both featured on BBC Radio and Television News programmes in the UK and also on French television. The story this time round was slightly different, and writers focussed on speculation that the island’s price was low because it was unlikely to sell, due to a totally unfounded theory that it was a desolate and creepy place, haunted by the ghost of the murdered relief keeper, Hugh Clark. Friends and colleagues of Hugh have subsequently told me that if he was to have had a ghost, it would have been gentle, kind and friendly like him, so there would have been nothing to fear.

Garden, Byres and Forge

Prospective buyers seemed undeterred by the lurid tales of a grisly and gruesome murder, and over one thousand expressions of interest were reportedly made to the vendor, from people in the UK, France and Switzerland. At the time of writing, an offer well in excess of the asking price has been accepted, and the people of Kirkcudbright and its surrounding area eagerly hope that their favourite island has found sympathetic and caring owners. I am pleased to have had so much unforeseen advance publicity, and hope that readers will enjoy my attempt to introduce some balance to the remarkable story of Life and Death on Little Ross.

Life and Death on Little Ross: The Story of an Island, a Lighthouse and its Keepers by David R Collin is published in November by Whittles priced £18.99.

Did you know that most of Britain’s gin is in fact produced in Scotland? Let us take you on a mini tour – from major cities to Hebridean islands – to find out what exactly makes some of Scotland’s many distinctive gins so delicious, and so loved worldwide.

Extract from Gin: A Guide to the World’s Greatest Gins

By Dominic Roskrow

Published by Collins

- Edinburgh Gin

producer: Spencerfield Spirit Company

abv: 43%

region and country of origin: Edinburgh, Scotland

website: www.edinburghgindistillery.co.uk

botanicals: Thirteen botanicals, including juniper berries, angelica root, citrus peel, coriander seeds, orris root, heather, and milk thistle

There’s something very special about the Edinburgh Distillery, which is underground, right in the heart of Edinburgh. Its owners describe it as being in a rabbit hole. It’s in the heart of Scotland’s capital that a range of gins and gin liqueurs are put together, including a very special navy strength gin by the name of Cannonball. This is the more standard offering and is a solid and well-made gin. The distillery welcomes visitors and offers tours, and you can try your hand at making gin while visiting. Proof that Scottish gin can be every bit as classy as a single-malt whisky.

- Pickering’s

producer: Summerhall Distillery

abv: 42%

region and country of origin: Edinburgh,

Scotland

website: www.pickeringsgin.com

botanicals: Juniper berries, coriander, cardamom, angelica, fennel, anise, lemon, lime, cloves

Summerhall Distillery has been making gin since 2004, so it precedes the current craft distilling boom, but there’s nothing very conventional about it. It operates out of an old animal hospital, which was part of a veterinary school known locally as The Dick Vet. Now it’s an arts centre called Summerhall and there is a pub next door called The Royal Dick. Simple, really. The whole operation is done by hand and distillation

takes place on two stills called Gert and Emily, after the founders’ maternal grandmothers. This version has a red wax seal, and the navy strength one has a busby. Don’t ask. The gin itself is very good indeed and has picked up a number of awards.

- Eden Mill Love Gin

producer: Eden Mill Brewery

abv: 42%

region and country of origin: St Andrews, Scotland

website: www.edenmill.com

botanicals: Juniper berries, coriander seed, angelica, rhubarb root, rose petals, goji berries, elderberries, marshmallow root, raspberry leaves, hibiscus flowers

A glance through those botanicals explains how this gin comes to have a pink hue but, while the whole concept might seem a touch tacky and gimmicky, this is a serious offering from brewer turned distiller Eden Mill. The story goes that the team set themselves the task of creating an ideal Valentine’s gift for February 14, 2015, and this is what they came up with. There’s method to the pink-tinged madness, because the mix of fruit and flowers makes for a smooth, subtle, sophisticated gin with true élan.

- Ginerosity

producer: Ginerosity

abv: 40%

region and country of origin: Edinburgh, Scotland

website: www.ginerosity.com

botanicals: Juniper berries, coriander, angelica, lemon, lime, orange, lemon myrtle, heather, cardamom, cloves

The name is a bit gimmicky and suggests that there’s more to this gin than a few botanicals. Let’s deal with the gin itself, first, though. Made by Pickering’s at Summerhall Distillery, this a well-made, stylish Scottish gin made with ten botanicals. But a clue to what makes this gin stand out is contained in the name. Purchase a bottle and all the profits from it are poured back into projects that will help deserving young adults to build themselves a better future. ‘That isn’t just a worthwhile cause, it’s a vital one,’ say the five-person team behind the idea. ‘And we’re exceptionally proud that we’re the first spirits company to do it.’ Ginerosity has linked up with the charity Challenges Worldwide to help young adults from disadvantaged backgrounds take part in International Citizenship Service (ICS) programmes.

- Hendrick’s

producer: William Grant & Sons

abv: 41.4%

region and country of origin: Girvan, Scotland

website: us.hendricksgin.com

botanicals: Juniper berries, yarrow, elderflower, angelica root, orange peel, caraway seeds, camomile, cubeb berries, coriander, orris root, lemon, rose, cucumber

While Bombay Sapphire can take much of the credit for bringing gin in from the cold, Hendrick’s played a key role in the drink’s rehabilitation. It’s owned by William Grant & Sons, a Scottish family-owned company that you’d expect to be stuff y and oldfashioned but that is anything but. With Monkey Shoulder blended malt whisky playing a similar role for Scotch whisky, Hendrick’s was targeted at the

trendy cocktail set and, backed by an ultracool website, it set about bringing a steampunk mentality to the drink. It’s flavoured with rose and cucumber post distillation and new drinkers were won over by a constant supply of new drink serves. Classy.

- Wild Island Botanic Gin

producer: Colonsay Beverages

abv: 43.7%

region and country of origin: Colonsay, Scotland

website: wildislandgin.com

botanicals: Juniper berries, coriander seeds, lemon peel, orange peel, liquorice, cinnamon bark, angelica root, orris root, cassia bark, nutmeg, lemon balm, wild water mint, meadowsweet, sea buckthorn, heather flowers, bog myrtle

Colonsay is a remote rocky Scottish island some two and a quarter hours from the mainland, and it is, indeed, a wild island, a mix of long sandy beaches, rocky outreaches, and stunning natural beauty. About one hundred people live here, and it’s known for its fresh oysters and honey from its native black bee. There is also a general store and a brewery. And it’s from the brewery that this gin comes. Take a look at the botanicals and it’s clear how strong an influence Colonsay’s landscape has had on this gin. The gin is produced in small batches on a copper still and only 750 bottles are released at a time. This is a gin of exceptional quality.

Gin: A Guide to the World’s Greatest Gins by Dominic Roskrow is out now published by Collins, part of the Little Books series, priced £6.99.

Mona McLeod worked in Kirkcudbrightshire during the second World War. The girls were given heavy agricultural work in fields, with animals, carrying hundred weight sacks, sawing wood, felling trees, filling up rat holes. This unique memoir provides a valuable record of a time when women faced the rigorous physical challenges involved in winning the war at home.

Excerpt from A Land Girl’s Tale: Concentrating on Winning the War

By Mona McLeod

Published by Scotland Street Press

With a rainfall of fifty-eight inches, Galloway was ideal dairy country. Snow and frost rarely lasted and grass often grew for eleven months in the year. On adjoining farms the Armstrongs usually had over one hundred Ayrshire cows. At Littleton, the larger of the farms, they made cheese. My training started disastrously in the dairy which was staffed by the dairyman and his wife and daughter. Milking started at 5am, cheese making after breakfast and the second milking about 4pm. Most of the cows would let down their milk to machines but the ‘difficult’ cows had to be hand-milked. By the end of the week every cow I had tried to milk had gone dry. The dairyman suggested that I should be moved to the stables: the cows and I were equally delighted.

There I was much happier. Horses keep more civilised hours than cows and we had always got on well together. There were five Clydesdales at Littleton, three at Townhead, and it was 1944 before the first of the tractors which were to replace them appeared. The thistle-cutting part of my training became much easier when I persuaded the men that I could manage a proper scythe better than the inefficient hook which was thought to be more appropriate for a girl. But to the end of the War I depended on one of the men to sharpen my scythe.

One of the pleasures of a mixed farm is the variety of the work. I became the orraman, defined in the dictionary as ‘a farm worker kept to do any odd job which might occur’. They usually worked on their own. I did most of the carting – hay, corn, turnips, dung and lime – and simple operations like drilling with one horse or harrowing with two. The men did the ploughing and, with three horses, drove the binder. I have ploughed, but would not claim to be a plough-woman. In my first summer I was entrusted with the hay rake, a simple horse-drawn rake which gathered cut grass into rows. These were ‘coled’ – drawn into small heaps manually – and a few days good drying would turn the grass into hay. This would be built into small stacks for further drying. Given a week of good weather, these would be carted to the steading, built into larger stacks and stored for winter feed. Inadequately dried grass would heat and moulder, ruining the hay. Silage, better suited to the Galloway climate, did not reach the Armstrongs’ farms till after the War. A method of preserving grass which had been developed in the thirties, it required a pit in which to store the grass – the silo – and a tractor to provide the pressure necessary to exclude the air. Cut green, the grass was stored in the silo and each layer compressed by the tractor and sprayed with molasses. When full, the silo was covered with a plastic sheet weighed down by old tyres or earth. The smell was terrible but animals loved the end product. In the large black bags seen in the fields now, air has been excluded by the pressure of the baler. Silage has taken the place of hay as the main source of winter feed.

Haymaking in the west of Scotland will always be a gamble; so too is the harvest. Heavy summer rain can flatten the crop and lack of sunshine delay ripening. Wheat and barley were limited to the arable farms of the east. In the west the use of combine harvesters was delayed until efficient drying techniques had been developed, but the horse-drawn binder worked well, cutting and tying the oats into sheaves and throwing them clear of the machine. Before any reaping machine could operate, the old-fashioned scythe had to be brought into use to clear a path round the field. One of the men would scythe the crop growing on the head rig and two of us would follow him, gathering the cut corn into sheaves and binding them with their own straw. A squad of workers would then follow the binder, building the sheaves into stooks, usually eight to a stook. If the sun shone they might be ready for stacking in a week but too often it rained and the corn began to sprout. The increasingly bedraggled stooks then had to be moved, sometimes repeatedly, to let in dry air and the harvest could drag on till September. During hay and harvest we worked a sixty hour week – seven to six – without extra pay. From six to eight there would be overtime at ten pence an hour for a woman. Although we might have worked longer the horses couldn’t. Unlike tractors, they had to have food and rest.

A Land Girl’s Tale: Concentrating on Winning the War by Mona McLeod is published on September 30th by Scotland Street Press priced £7.99. The Scottish Arts Club in Edinburgh hosts the launch event on 28 September from 6-8pm.

This new book explores the histories of individual flint glassworks in Scotland from the 18th to the 21st century, when Scottish glass production was flourishing. Major works in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Leith are looked at in detail, while other smaller, virtually unknown, producers like the Clyde Flint Glass Company in Greenock are also covered. This excerpt introduces some of the book’s main themes and identifies some of the key moments, and trends, in Scottish glass manufacture through the ages.

The Magic and Misery of Glassmaking: Researching the History of the Scottish Glass Industry

By Jill Turnbull

Published by Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

Glass is easily ignored. We look through it, drink from it, admire our reflection in it, adjust our lenses and take it for granted. It’s just there. But when the Edinburgh Crystal chemist described glass to me as eighty percent chemistry and twenty percent magic, I realised there is a lot to discover. This short article will try to demonstrate the sort of insights obtainable from material such as recipes in an archive, legal documents in the National Records of Scotland, old newspapers and personal stories covering a period of over 170 years, which illustrate a little of the magic and some of the work which goes into creating glass.

Researching the post-1750 history of Scottish glassworks involved all the usual sources: Court of Session papers, sasines, registers of deeds, estate papers, newspapers, facts and figures. But in the Museum of Edinburgh is the Ford-Ranken collection, a treasure trove of material from the 94 years of the Holyrood glassworks, including design drawings, vital to the identification of Scottish glass, and recipes, which show how difficult it can be to make the magic work.