This new book from Wild Goose, official publishers of the Iona Community, celebrates the change of seasons and reflects on the darkness and light of autumn and winter. These reflective poems are ‘a ticket and passport for a spiritual journey’ and can be used in a daily discipline or with groups.

Winter Night/Longest Night

On winter’s longest night

ebony stillness unfurls

a field of cosmic sequins

incomparably vast,

flung out sparkling,

granulated from some

mass of stuff

long since exploded.

I ponder galaxies,

each embracing

a hundred billion

shining, spinning suns.

My mind stumbles

in this darkness,

but catches itself

on the solid joy

of living in this galaxy,

whirling around

this little sun,

grateful for firm grasp

of infinitesimal smallness,

expansive as the universe

on winter’s longest night.

The Heart Is a Field

There is a dormant place

a fallowness in the heart

that awaits awakening,

awaits furrowing,

awaits some seed to be sown

that will take root,

send out tendrils,

fill inner life

with flowers and fruit.

Who will put hand

to that plough, not look back,

ignore stone or weed,

scatter that seed?

Pulsing with potential,

beating beatitude,

the heart is a field.

Who will till and sow

and gather into barns?

From Darkness to Eastering

By Bonnie B Thurston

Published by Wild Goose

This is a book about how, on a cosmic and a personal level, darkness gives way to light. It does not sugar-coat the reality of darkness but is full of hope, reminding voyagers that ‘light shines in the darkness’, that darkness is required to perceive light – and that Easter means the light has come, life triumphs, and the promised Holy Spirit will empower us for growth: ‘eastering’…

These reflective, prayerful poems are ‘a ticket and passport for a spiritual journey’ and can be used in a daily discipline or with groups.

‘For each traveller I pray journeying mercies,’ Bonnie Thurston writes. ‘And I remind pilgrims: Take heart. He will come.’

Having resigned a professorship and chair in New Testament studies, Bonnie Thurston now lives quietly as a solitary near Wheeling, West Virginia, USA, working as a spiritual director and retreat leader and volunteering in a food bank. She is the author of over 20 books.

‘You are in skilled hands here, so let yourself be carried along, ready to experience delight, or be jarred into discomfort. Above all ponder, weigh, take time. For each poem comes out of the quiet depths of a person who is a fellow pilgrim, illuminating the familiar with her own God-given insight.’

From Darkness to Eastering by Bonnie B Thurston is published in September by Wild Goose Publications.

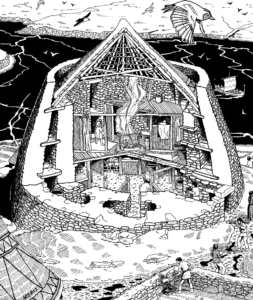

Book trailers are an increasingly popular way to reach readers. Ahead of publication of her new novel for children, Highlands-based author Barbara Henderson takes us behind-the-scenes of the making of the Punch trailer, to describe how it all came together from concept through to execution, despite a few obstacles along the way…

Making the Punch Book Trailer (Is that the way to do it?)

By Barbara Henderson

My new children’s novel Punch was going to be out in the big wide world in the autumn, and my thoughts were turning to the book trailer. After all, the Fir for Luck book trailer had over 800 views, and provided such an easy and visual intro to the book for school visits and events. It also definitely generated interest in Fir for Luck ahead of its publication in 2016.

Punch needed a trailer!

I got busy typing draft screenplays. But I found it surprisingly hard – after all, the book begins with a gigantic fire which completely destroyed part of the old town in Inverness. Kind of hard to recreate on the budged I was working with. Not to mention the pretty crucial role played by a dancing bear – again, footage was going to be hard to come by.

After a few drafts, I thought I had it: a one-minute trailer which would give a flavour of the story, without giving everything away. Flashes of fire, the frantic pace of a young runaway, flashes of landscape and of the world of travelling entertainers. Yes, this could really work. I arranged for family friend and filmmaker Ross Wiseman to visit for the day, primed ‘the talent’ (my 12-year-old son), gathered props and costumes – and kept my fingers crossed for the forecast!

The day arrived.

Along with eight hours of solid rain.

I picked up film guru Ross in the morning, and hopefully we headed off north to Strathpeffer – not only a lovely Victorian-looking place, but crucially, with a drier forecast. The buildings were grand, right enough, but not close enough together to create the impression of 1889 Inverness. On top of that, my previously willing talent had become a little self-conscious about walking and running around in the Victorian gear we’d borrowed from the theatre. We did many u-turns, reversed our way out of corners, drove along this street and that, before finally admitting the game was a bogey. Back to Inverness we went without a single shot in the can.

To our dismay, it still rained enthusiastically in my home town (and the setting of the book’s opening chapters). Time for a reboot.

Amazing what a bowl of soup can do for the dejected spirit – by the time we left for the museum at 2pm, the whole thing seemed tight, but almost possible again. We arrived early. The talent got changed and emerged a little reluctantly into the tourist-path between Inverness Castle and the town – it didn’t help that a group of passing Italians stopped to take pictures of him as soon as he appeared. Twenty minutes of scrambling up castle hill through long yielded our first usable footage. Ross the cameraman was beginning to smile.

Punch author Barbara Henderson

Into the museum for our appointment with the Victorian Punch and Judy puppets it was.

Handling and filming the very puppets with which the Morrison family had entertained Highland audiences from Victorian times, now that’s a privilege you don’t get every day. I had a fan-girl moment. I apologise for the completely unhinged grin in the picture. I have no excuse, I was carried away by the moment.

Next was a trip to my house which wasn’t far away: We needed my main character to witness the huge fire from the top of a tree.

We tried to film this in our tiny bathroom, the only room which we could black out completely, with me holding the laptop screen above the talent’s head so the flames would dance on his face, and daughter 2 waving a branch of fir tree beside, as if moving with a breeze. After all that effort, Ross scrutinised the screen: ‘No – too dark.’ We tried again outside and in the kitchen. It would have to do. On to daughter 2’s dancing feet, and some lovely landscape shots of Loch Ness.

The rain had cleared up by then, leaving behind a moody layer of cloud and mist. Some fiddle-scraping in a flowery field might give the summery impression we were after. As evening fell and the town emptied, the talent became a little more relaxed, and we were able to get some running shots in the old town, up and down the tiny patch of cobbles we had found in a lane.

With the husband home from work and our stomachs full of pizzas, we headed for our final stop. What are the chances – the beautiful staircase in Eden Court’s Bishop Palace, normally accessible round the clock, was being used for a wedding! Noooo! I needed a nice old stair for my murder victim!

And no, we could not return the next day! We had today, and only today, before Ross-with-the-camera was off to Glasgow again!

The husband, reluctantly supportive, seemed relieved. ‘Oh well,’ he sighed, grinning out his relief and steering towards home.

‘No wait! One more try!’ I had heard of the beautiful staircase in the Royal Highland Hotel. ‘You’ll never get permission at this short notice,’ the husband argued, but he must have felt confident he was right – he pulled in by the station and I tried my charm offensive with the receptionist. I needn’t have worried. No problem at all, apparently. Film away!

My husband’s grin quickly turned to a grimace when I told him that yes, I expected him to lie down, upside down, on a staircase in a tourist-crowded hotel lobby on a Friday night, and play dead. I still can’t help laughing pretty hysterically whenever I think of it! The only thing still missing was a little footage of an old clock which Ross and I sneaked in on the way home just after 11 pm.

My husband’s grin quickly turned to a grimace when I told him that yes, I expected him to lie down, upside down, on a staircase in a tourist-crowded hotel lobby on a Friday night, and play dead. I still can’t help laughing pretty hysterically whenever I think of it! The only thing still missing was a little footage of an old clock which Ross and I sneaked in on the way home just after 11 pm.

About seven different versions of the Punch Trailer were bandied around in cyberspace before we settled on what you see here. My teenage daughters recorded the panicked screams at a party with friends, but the volume had to be very low – it really just sounded like teenagers having fun. We had to abandon one of my very favourite shots, of the talent running across an old Victorian footbridge with Inverness Castle looming behind – simply because a moving car in the very background instantly broke the Victorian feel, and though it’s tiny, once I had seen it I couldn’t unsee it.

Music from my insanely talented friend Liza Mulholland completes the package.

Has it worked?

You decide.

Punch by Barbara Henderson is published by Cranachan Publishing on 23 October priced £6.99.

Publishing Scotland, in association with Creative Scotland, are pleased to present New Books Scotland, a selection of the best books to look out for from Scottish publishers during autumn and winter 2017.

You can discover new reads across fiction, non-fiction, and children’s, and if you’re an international publisher, rights are available for the showcased titles. Read the introduction, and view the PDF below, to find out what Scottish publishing is producing for your reading – and rights-buying – pleasure in the latter half of this year…

The print version of New Books Scotland launched in August 2017

Welcome to the latest showcase of Scottish writing and publishing for Autumn/Winter 2017. Here we feature new talent from small presses, established writers creating powerful new works, fantastic children’s books and young adult imprints. The selection of new and upcoming books offered in this edition of New Books Scotland reflects the energy and talent bursting forth from Scotland’s publishing scene.

Our publishers continue to delight and inspire young readers, with art-driven children’s titles from Serafina Press, Moonlight Publishing’s stunning illustrated information books, imaginative cross-over titles from dynamic Glasgow-based Strident Publishing, and Floris Books – Scottish Publisher of the Year (2016) and the largest children’s book publisher in Scotland. Floris Books also specialise in non-fiction for adults, with unusual titles bringing new perspectives on the world. This fresh outlook and passion for alternative voices is also evident in titles from Black and White Publishing which has grown into one of Scotland’s leading independent publishers with over 300 books in print across a variety of genres. In addition, creative independent publisher Saraband strive to offer readers an offbeat, original selection while ThunderPoint Publishing brings you radical ideas and challenging messages from established and first-time authors.

Elsewhere, Scotland’s publishers continue to forge partnerships internationally. Sandstone Press demonstrate a strong commitment to publishing titles from all over the world while Vagabond Voices is an independent publisher that is both Scottish and fervently European in its aims, introducing new titles from Scottish authors and translating fiction from other languages. Meanwhile, Scotland’s own languages are celebrated and promoted by the Association for Scottish Literary Studies (ASLS), a charity promoting the study, teaching and writing of Scottish literature.

Our capital city remains home to publishers large and small. The superb output by Edinburgh University Press reflects their place in one of Britain’s oldest and most distinguished centres of learning, while the wonderfully illustrated and immaculately researched titles from Historic Environment Scotland are a must for anyone with an interest in Scotland’s history and heritage. Such readers would also cherish publications from the Society of Antiquaries, an establishment which has actively supported the study and enjoyment of Scotland’s past for over 200 years. Relative newcomers Scotland Street Press have consistently produced quality fiction and non-fiction since their founding in Edinburgh in 2014, while Muddy Pearl, an independent publisher of Christian books, continue to provide a range of thought-provoking titles.

The breadth of output and diverse approaches from our member publishers continues to impress those at home and abroad. Whittles Publishing have forged an international reputation for their academic and professional titles, as well as their wide range of non-fiction books, while BHP Comics handle books from established creators alongside cutting-edge talent. Readers should also seek out William Collins, part of HarperCollins, for a roster of prize-winning and agenda-setting books spanning science, history, art, politics and current affairs, biography, religion and natural history. And finally, National Galleries of Scotland, with their influential books on the visual arts, continue to provide readers with engaging, accessible and affordable books, offering an insight into the nation’s collection and exhibitions. The high quality, diverse and inspiring selection of titles in this edition of New Books Scotland showcases the talent, creativity and dynamism of our member publishers, providing you with an insight into the exciting Scottish publishing scene.

Here bestselling author Lin Anderson introduces her new novel Follow The Dead, the twelfth book in the thrilling Rhona MacLeod series.

Sitting by the fire in my home village of Carrbridge playing Hogmanay party games, watching the blizzard rage outside, gave me the idea for Follow the Dead. Then visiting with Willie Anderson leader of the Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Team I learned that every death on the mountain is considered a crime scene, and because of this CMR are the first forensic team to secure the locus… and the story was truly born.

Extract from Chapter 1

Isla woke at two, knowing she would have to go outside, despite the weather. No one, but no one, went to the toilet inside the refuge, whatever the circumstances. Isla wished now that she hadn’t had that final whisky.

There was nothing for it but to go.

Unzipping the sleeping bag, she pulled herself reluctantly out, realizing almost immediately that the temperature had dropped further since they’d gone to bed.

It must be easily minus fifteen.

She pulled on her outer garments, then eased her way past the second sleeping bag and crawled out of the crevice entrance. On exit, an ice-cold wind met her head-on, snow immediately gathering on her lashes and mouth.

Lin with Willie Anderson (Team Leader of Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Team) being interviewed for STV by Emma Murray (at camera) about Follow The Dead at CMRT HQ.

She would have to be quick.

She realized then that the blizzard had momentarily eased and the powder snow that met her face was being whipped from the surface. Above her, the clouds parted, exposing a half-moon and accompanying stars. To the west, its beams had magically found the long strip of a frozen Loch A’an. For a moment she took in this wonder, then need drove her to locate a sheltered spot via her head torch where she might undress enough to relieve herself.

The snow began falling again as she rearranged her clothing, the wind returning with a force that suggested it had only paused long enough to allow her to go to the toilet. In moments she was surrounded by a swirling snowstorm, fierce and disorientating. Only yards from the cave, Isla was no longer certain of its exact direction. The huge slab of rock that formed the Shelter Stone had disappeared, as had the loch and surrounding mountains.

The force of a sudden gust thrust her to her knees and her head met a nearby rock. Dazed by the impact, she looked up to discover a tall figure beside her as though formed by snow. A gloved hand caught her arm. She thought it must be Gavin come to look for her, then registered that it wasn’t.

‘You okay?’ a male voice said.

Lin with Willie Anderson (Team Leader of Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Team) at CMRT HQ

She nodded. ‘I came out to—’ She halted, realizing she had no need to explain.

‘You have companions?’

‘Yes, at the Shelter Stone.’

He helped her up, the bulk of his white-suited body shielding her from the wind, and pointed the way. She wanted to ask him who he was and where he had come from, but that would have to wait until they got to the cave. Around her the air crackled as though charged with electricity and behind her the crunch of her companion’s footsteps seemed unnaturally loud and spaced out as though she was being followed by a giant.

The Big Grey Man of Ben Macdui.

She anticipated introducing him as such to the others and their imagined reaction brought a smile to Isla’s frozen lips.

Then, as the curtain of snow briefly parted, she suddenly saw what lay before her. They were going in the wrong direction, heading down the boulder scree towards the loch, rather than upwards to the stone. She turned to tell him this and her head torch picked out his face staring down at her.

As the wind swallowed her words – ‘We’re going the wrong way’ – Isla began scrambling back, her numb hands trying desperately to grip the snow-covered boulders.

Finding her feet again, she rose to face him. And in that moment she knew.

He has no intention of helping me.

Follow The Dead Launch event 12/08/2017 at Cairngorm Mountain Rescue Team HQ – panel: Professor James Grieve (Emeritus Professor of Forensic Pathology at University of Aberdeen), Jenny Brown (Chair), Lin Anderson, Willie Anderson

His gloved hand met her chest with a force that knocked the air from her lungs. She staggered, losing her foothold on the jumble of snow-crusted rocks. Thrust backwards by the impact, she tried to find her centre of gravity again, but couldn’t right herself before the second punch arrived, this time in her stomach. She crumpled under the impact, bile rising in her throat.

He had chosen the spot well. Behind her was nothing but a steep boulder-strewn slope that even the snow couldn’t soften. He was on his knees now, peering down at her, determined to finish the job this time. Isla made one last desperate grab for her attacker.

I’ll take the bastard with me.

Her grasping hand found his face and she dug her nails in hard. His muffled shriek told her she had hit home.

Then the short fight was over. The third and final impact achieved its aim. As she tumbled backwards, crashing against rocks, rolling, her mouth open in a silent scream, the tall figure melted into the blanketing snow.

Follow The Dead by Lin Anderson, the twelfth book in the Rhona MacLeod series, is out now published in hardback by Pan Macmillan priced £12.99.

Lin in Stavanger in June 2016 researching the parts of Follow The Dead set in Norway

You can catch Lin at the following forthcoming events:

5th September 2017 at 19:00 – Lin Anderson talking about Follow The Dead at Waterstones Aberdeen

8th September 2017 at 18:30 – Lin Anderson speaking about her contribution to the Bloody Scotland anthology of new short stories at Stirling Castle

9th September 2017 at 15:45 – Lin Anderson ‘The Dark Lands’ event at Bloody Scotland

30th September 2017 at 13:30 – Lin Anderson in conversation with author Maggie Craig at Culloden Visitor Centre for the 20th Anniversary of her classic book ‘Damn Rebel Bitches’

This month sees the launch of Trespassers, the much-anticipated sequel to YA author Claire McFall’s debut novel Ferryman. Charting the unbreakable bond between train crash victim Dylan and Tristan, an immortal guide who must lead her soul safely to the afterlife, Ferryman won a Scottish Children’s Book Award, was long-listed for the Branford Boase Award and was nominated for the Carnegie Medal. But that’s not where the Ferryman story ends.

A rights deal secured in June 2015 has launched McFall into superstardom in China, where she was the only UK author in the 2016’s Top 10 Fiction Bestseller list. With more than one million books sold worldwide, the arrival of Trespassers is sure to kick up an international storm. Read on for an extract of Ferryman, which has been reissued by Floris Books ahead of the Trespassers release….

Extract from Ferryman

By Claire McFall

Published by Floris Books

He was sitting on a hill to the left of the tunnel entrance, his hands wrapped around his knees, and he was staring at her. From this far away all that she could tell was that he was a boy, probably a teenager, with sandy hair that was being tossed around by the wind. He didn’t stand or even smile when he saw her looking at him, just continued to stare.

There was something odd about the way he sat there, a solitary figure in this isolated place. Dylan couldn’t imagine how he had come to be there, unless he ’d been on the train as well. She waved at him, glad to have someone to share this horror with, but he didn’t wave back. She thought she saw him sit up a little straighter, but he was so far away it was hard to tell.

Keeping her eyes firmly on him, just in case he disappeared, she slipped and slid down the gravel bank of the train tracks and hopped over a little ditch filled with water and weeds. There was a barbed-wire fence separating the tracks from the open countryside. Dylan gingerly grabbed the top wire between two of the twisted metal knots and pulled it downwards as hard as she could. It dropped just low enough for her to awkwardly swing her legs over. She caught her foot as she pulled her second leg over and almost fell, but she managed to cling on to the wire and keep her balance. The barbs cut into her palm, piercing the skin and causing little droplets of blood to ooze through. She examined her hand briefly before rubbing it against her leg. A dark stain on her jeans made her take a second look. There was a large red patch on the outside of her thigh. She stared at it for a moment before remembering wiping the sticky stuff from the carriage floor off her hands. Realisation made her blanch and her stomach heaved slightly.

Shaking her head to rid herself of the sick images that were swirling in her brain, she turned from the fence and fixed her eyes back on her target. He was seated on the slope about fifty metres above her. From this distance she could see his face, and so she smiled in greeting.

He didn’t respond.

Slightly abashed by this frosty reception, Dylan stared at the ground as she made her way up the hill towards him. It was a hard climb and before long she was panting. The hillside was steep and the long grass was wet and difficult to wade through. Looking down, concentrating on her feet, gave her an excuse not to make eye contact – not until she had to.

With cold eyes, the boy on the hill appraised the girl approaching him. He had been watching her since she had exited the tunnel, emerging from the dark like a frightened rabbit from a burrow. Rather than shouting to get her attention, he had simply waited for her to see him. At one point he had been concerned that she would head back into the tunnel, and he had considered calling out, but she had changed her mind, and so he’d contented himself with sitting silently. She would notice him.

He was right. She spotted him and he saw the relief pool in her eyes as she waved energetically. He did not wave back. He watched her face falter slightly, but then she approached him. She moved clumsily, catching herself on the barbed-wire fence and tripping on clumps of wet grass. When she was close enough to read his expression he turned his face away, listening to the sound of her drawing nearer.

Contact made.

Claire McFall is a writer and a teacher, living and working in the Scottish Borders. Along with Ferryman and Trespassers, she is also the author of dystopian thriller Bombmaker and her paranormal thriller Black Cairn Point, winner of the Scottish Teenage Book Prize 2017. Get your tickets to see Claire at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on 26 August 2017 here.

Ferryman by Claire McFall is out now published by Floris priced £7.99. Trespassers will be published by Floris on 14 September priced £7.99.

When the SS Kursk sank in Belgian waters in 1912 it carried a highly valuable shipment of precious French crystal. In this book, translated from the original Dutch into English for forthcoming publication by Caithness-based Whittles Publishing, through text and photography this extract gives insight into the ill-fated ship’s unique luxury cargo which was in-part bound for Russia’s Tsar Nicholas.

Extract from Diving For Treasure

By Vic Verlinden and Stefan Panis

Forthcoming from Whittles Publishing

Some North Sea shipwrecks hide valuable cargo that is discovered many years after the ship has been lost. For example, the SS Kursk contained a precious shipment of French Baccarat crystal. Worth a fortune in 1912, it was a luxury product only the richest could afford.

SS Kursk

Type: Steel cargo steamer

Built: Burmeister & Wains, Copenhagen, 1881

Company: DFDS

Propulsion: Steam engine/screw

Tonnage: 1,131 tons

Length: 80m, beam 14m

Speed: 8.5 knots

Storm on the North Sea

During the night of 26th August 1912, a heavy storm, tracking south-west, was raging in the North Sea, putting a lot of ships in distress. One of these was the SS Kursk, on its way to St Petersburg, Russia. When berthed in Antwerp, an 8m granite column with a bronze eagle was placed in the hold of the 80m long ship – intended to be erected at Borodino, Russia, to commemorate the battle fought there against Napoleon in 1812. The French sculptor Paul Besanval designed the monument and would be personally supervising its placement in Russia. When the loading of the Kursk was completed, Captain Wiencke and the Belgian pilot wanted to leave quickly as the weather was becoming worse by the hour.

Tsar Nicholas ordered part of the Kursk’s cargo

The Kursk is missing

The ship was built in 1881 at the Copenhagen shipyard of Burmeister & Wain, and was fitted with a 150hp steam engine. This was fired up by the stoker on the afternoon of 26th August 1912, and the SS Kursk commenced its long journey to Russia. When the ship was steaming down the Scheldt river the weather deteriorated, and once at sea a full-blown south-westerly storm developed, placing the Kursk in serious peril.

What happened next is anyone’s guess. One of the theories is that the ship took a north-westerly course, and taking the waves broadside made the ship roll heavily. This rolling could have made the monument slide to one side, creating a sudden list and subsequent flooding. What is known is that none of the passengers or twenty-seven crew were able to launch the lifeboats in an attempt to save themselves. The next day several bodies washed ashore on the Zeeland coast, including Captain Wiencke’s wife and the Belgian pilot. Some days later the newspaper noted that skipper H. Tanis of the fishing boat OD20 out of Ouddorp found a damaged white lifeboat carrying the name Kursk Kopenhaven offshore of Brouwershaven, close to Renesse, in the Netherlands.

A beautiful crystal decante

Unknown wreck at 13 miles

The wreck has been visited by divers for many years, although it was not until 1999 that a couple from Limburg found the first crystal in 1999 on the then unidentified ship. They kept their discovery a secret until a Dutch team led by Cor Wouben, who had nonetheless heard about the find, visited the wreck. This team found a small milk jug marked with the logo of the shipping company DFDS, the abbreviation of Det Forenede Dampskibsselskapet, Copenhagen. DFDS is still active and has a branch office in Belgium. When the story about the monument became known, the Netherlands Association for Ship and Underwater Archaeology (NISA) issued a salvage ban to protect the monument from treasure hunters.

Diving the Kursk

The salvage prohibition is still in force today and is enforced by the Dutch coastguard. The wreck is in the geographical position of 51.53.70 north/003.32.09 east. It is also marked on sea maps and is outside the shipping lanes. The top of the wreck is at a depth of 26m; however, if you drop down below the deck of the ship, a depth of 32m can be reached. The visibility can vary from centimetres, requiring divers to use a reel to navigate, to 6m on a good day.

Barrels covered in growth

The forward part of the wreck, up to the engine room, is buried under sand and silt. The engine room is still recognisable, but you need to watch out for fishing nets and lines in this area. The rear cargo hold contained the load of crystal, which has mostly been recovered. Another part of the cargo consisting of barrels is still visible, and over the edge at the stern you will find the propeller sticking up from the sand.

Dfdslogomelkkan

Milk jug with the shipping line’s crest

Borreglkursk, kristalwr1 and kriskast

Crystal found on the wreck

One of the authors, Vic Verlinden, with his camera

Diving For Treasure by Vic Verlinden and Stefan Panis is forthcoming from Whittles on 31 October priced £18.99.

Artist and author Martynas Noreika investigates the life and writing of Antanas Škėma, whose soon-to-be published novel The White Shroud was first published in Lithuania. Set in 1950s New York, The White Shroud’s narrative centres around the struggle of émigré poet Antanas Garšva to adapt to life in a completely different, and ultimately indifferent, modern metropolis.

By far the most popular image that comes up if you Google Antanas Škėma is a black and white headshot, fully in keeping with the aesthetics of Hollywood’s golden age, in which it’s hard to say what’s more coiled: the sensuous, swirling grey plumes of Marlboro smoke framing his face; or his smile, a sneer the likes of which Oscar Wilde would be proud of, to say nothing of the cravat. It’s posture, sure, but nevertheless he looks comfortable, at peace in his new home. Fully integrated.

Though I missed out on the good looks, I’ve got a few things in common with the man in the photo.

I was a foetus during my country’s Singing Revolution of 1990 and (if you’re talking to my dad) took my first ever steps in the shining dawn of a newly independent republic. One way or another we didn’t stay long. Spurred on by enthusiastic success-stories of emigration to the UK and beyond, my parents moved our fates to London in the early nineties. They brought elements of their history and culture with them and strained to keep the language alive in me and my brother. Yet despite their efforts, I grew up a mere semi-bilingual member of the Lithuanian diaspora.

At university we were encouraged to read far and wide across our interests and taught to see artworks as orphans: forever ready, willing and anxious to be adopted to the needs of any new circumstance. Since I always had room for the Modernists, it’s not much of a coincidence that many a late night, what-the-hell-should-I-read-next Wikipedia dérive would end up in front of Škėma’s Magnum Opus, White Shroud (Balta Drobulė, 1958). Time and again I’d stumble across references to the novel, but since all of my reading and formal education was conducted in English, any command of Lithuanian I still had was exclusively spoken. Whether I could get my hands on the text or not was irrelevant, as no English translation existed.

It’s now maybe a little unfashionable (and I can’t remember where I first heard it stated like this) but I’ve always felt an affinity with the more classical model of reading: an idea of the reader as an amateur musician. Someone who sits down at the piano or whatever and has some music by somebody they don’t personally know and cant possibly measure up to, and they have to use their skill to play the piece. The more you put yourself into a text, the harder you practice, the better your experience ultimately is. You can read well or you can read badly and in a work like this, being able to understand the words doesn’t immediately get you so far.

That being said I definitely don’t mean to put anyone off. The book is beautiful and well worth the effort.

Antanas Škėma. Image Credit: Alchetron.com

Many of my favourite pieces of Modernist art intentionally exclude faraway utopias or divine realms. Instead, they’re often about considering the familiar with an unusual vigour and sincerity, looking at specific experiences in everyday life. Škėma’s character Antanas Garšva – no prizes for guessing who he’s based on – is a struggling émigré poet working a menial job as a lift operator in a large New York hotel. He notes every passing detail, counting each individual coat hook (ask any aspiring artist: in a dull job you count everything, not just the clock). Good, judicious narrators recognise that lives can be meaningful even when they involve a lot of failure and humiliation, and much of the novel chronicles the transformation Garšva undergoes inside the shaft, going up and down in an enclosed room and feeling increasingly unwell, whilst selling the one commodity he has: his time.

Though Škėma occasionally flirts with narrow-world existentialist notions, namely the absurd condition of man as plotting his course without adequate reason or insight, the novel is generous and multifaceted, with every aspect of Garšva’s life handled with honesty and focus. Škėma had a good sense of how demented and fragile we all are deep down, and existentialism’s tragic dimensions of human existence come in the end only to inform the passages in the lift. For his protagonist, the act of writing poetry is more than a reaction to the banality of everyday life: it’s a passionate desire to overcome death through self-expression. The poet wants to leave his mark on the history of literature and believes deeply in the logic of his craft. The narrative shifts back and forth with frequent digressions to Garšva’s past, accessed by the reader through diary entries and standalone vignettes, brief chapters that express the artist’s inner-reflections or provide insight into the events that made him. After all, the book seems to suggest, beliefs are like loyalties: they’re only really meaningful when they’re tested. If the world is meaningless and it’s merely our delusions that drive us, are they really all that bad?

A particular joy for me was the dialogue, much of it featuring a kind of corrupted English émigré slang. I smirked like Škėma’s portrait whenever I encountered these in the text, as they brought back fond memories of my own family home and upbringing. Bilingual households tend to have a slippery, entirely natural overlap between tongues as they’re often spoken in tandem.

I can’t imagine that translating anything is ever easy or straightforward but with this novel in particular, let’s just say I have a huge amount of respect for the people involved. My basic grasp of the language meant that I could imagine how certain passages might sound, and in the resulting rhythm, constitute to a kind of independent meaning. While I’m sure that carrying this through to the translation would have been impossible, I nevertheless thought about the novel as an experiment with the musicality of language itself. The definition of what a ‘Changeling’ is as put forward by this publisher couldn’t be more apt. It’s a different animal.

On my second read-through I followed the text along with the original Lithuanian on audiobook and was thrilled at how melodic it sounded. Packed with onomatopoeic, jagged prose and angular chords, descriptions dependably rendered in high style; sonorous gems everywhere, regardless of subject matter. Škėma’s tone simultaneously lyrical and coarse yet always managing to flow, at times reminding me of the tumbling meter of Ginsberg and the Beats. Thanks to this translation, I felt doubly privileged to have been able to listen to the book as well as read it.

Martynas Noreika is an artist and writer based in Glasgow. He studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London and is currently working on his first novel.

Škėma’s novel The White Shroud will be published on 26 October by Vagabond Voices priced £10.95. This edition is translated by Karla Gruodis.

Aged just 17 Estelle Maskame, based in the North East of Scotland, exploded on the Young Adult publishing scene with her bestselling DIMILY [Did I Mention I Love You] trilogy. Her new YA novel Dare To Fall, published in July, has already caused a social media stir thanks to her global community of fans. In this interview Estelle explains how the book came about and why being a published author is a dream come true.

Estelle Maskame

Q. You started writing when you were only 13 years old and landed a three-book deal with Edinburgh-based Black and White Publishing by the time you turned 17. How did this come about?

A. I’d been posting my work online on several different writing communities, hoping to gain some helpful feedback from anyone who would take the time to read my work, when it blew up into something much bigger than I expected it to. Through promoting my work across social media and being consistent with my writing, I gained 4 million hits online and built up my own fanbase within less than four years. I was interviewed for my local newspaper, and then STV came along and wrote a few pieces about me, and then I was on their TV news. Word was spreading and that’s when Black and White Publishing came into the picture, and a month later, I signed my book deal and left school.

Q. What’s it like writing full time at such a young age?

A. I absolutely love it! Most days, I just get to enjoy my hobby, so there really is nothing more I could wish for. However, it can get quite stressful and isolating sometimes too.

Q. Your online following has played a big role in your publishing story and how you connect with readers across the world. You have a huge number of followers including almost 170K Twitter followers, some of whom are very devoted fans. What’s that like?

A. It’s amazing! Without a doubt, I wouldn’t be where I am today if it weren’t for the support of my readers across social media. I like to think of them all as my friends more than anything else, because I really do share everything with them and it’s such an incredible feeling knowing that there are so many people out there who believe in me and are rooting for me. I always want to do them proud, and I hope that I can inspire them to work hard to achieve their own goals and dreams too.

Q. The Did I Mention I Loved You (DIMILY) trilogy has been a huge success internationally and is currently licensed to an impressive 16 countries. Do you have any international highlights?

Q. The Did I Mention I Loved You (DIMILY) trilogy has been a huge success internationally and is currently licensed to an impressive 16 countries. Do you have any international highlights?

A. Definitely the time I visited Paris. DIMILY has done really well in France, and I can remember doing my first French book signing last year in Paris and glancing up at the three hour long queue and having it hit me all at once that I was living my dream – ever since I was young, all I had dreamed of was being an author who could do book signings in other countries where there would be a line of people holding my book in their hands, so that was a cool moment for me.

Q. Tell us about your new adventure – Dare to Fall.

A. Dare to Fall is my new Young Adult romance, in the same contemporary style as DIMILY, which is a standalone novel. It focuses on MacKenzie, a girl who is terrified of grief, and Jaden, a boy who is grieving. It’s been super fun to work on something new but also challenging, and I can’t want for people to read it!

Q. Lastly, what’s next?

A. I’m taking a break at the moment now that I’ve finished Dare to Fall, but soon I’ll be diving straight into my new project – it’s an idea I’ve been toying with since 2012, so I’m very, very excited to finally give it a go. Again, it’s still Young Adult contemporary romance, and I’m confident that my readers will love it, but it’s all still a secret for now!

A. I’m taking a break at the moment now that I’ve finished Dare to Fall, but soon I’ll be diving straight into my new project – it’s an idea I’ve been toying with since 2012, so I’m very, very excited to finally give it a go. Again, it’s still Young Adult contemporary romance, and I’m confident that my readers will love it, but it’s all still a secret for now!

Dare to Fall by Estelle Maskame is out now published by Black and White imprint Ink Road priced £7.99.

You can read an extract here from Did I Mention I Love You? on Books from Scotland.

First published in 1935, I Loved A German is one of the best known novels by the Estonian classical author AH Tammsaare. One of very few texts in the Estonian literature to present a Baltic-German perspective, this edition is forthcoming from Glasgow-based Vagabond Voices, an independent publisher that is both Scottish and fervently European in its aims.

Extract from I Loved A German

By AH Tammsaare

Forthcoming from Vagabond Voices

“Every educated person can write at least one novel – a novel about himself.” I’ve read those words somewhere, I remember it clearly. But where? I’ve forgotten.

It is very probable that I have read those words several times, because I’ve noticed that words are like announcements: they have to be repeated, otherwise they don’t catch your eye or stay in your mind.

There’s a reason why things happens like that: some thoughtful words appear first somewhere in a book, then in a magazine, and finally in a newspaper. But the order of appearance might be the opposite: first in a paper, then in a journal and finally in a book – as a serious scientific study or a respected novel which schoolchildren have to read.

For as education grows from year to year, people are writing clever things all over the place, so that you hardly know any more what you should take up to read. So for an educated person the only intellectual relaxation and treasure-house is the cinema, which doesn’t make you yawn or put you to sleep.

And yet the written word must have some importance in the future, there’s no denying it, or at least for now, and until educational institutions have been completely reformed. Since ancient times they’ve seen it as their duty to get young people used to reading boring books – only boring ones of course, on the correct assumption that the interesting ones will be read anyway, like it or not.

Apart from that, strangely enough, there are still people in the world who like to read books and other writings only when they’re bored. Even their tastes have to be satisfied.

Finally the written word is important for recording those things that don’t stick in your mind: such as the first sentence of these lines, so that everyone can look back at will and see who used it the first, second, third time and so on. Such a record could accommodate the names of all the films in the world, so that an educated person won’t have to go and see the same film again for the tenth time.

The general shape of my skull is oval, but with a certain inclination or pressure toward the back of the neck, which is said to be the seat of reason – something that so far I haven’t taken account of. The jaws have a musculature as if fate had marked me to be a biter, though I don’t actually have an urge to sink my teeth into anything. Today, for instance, it’s now past twelve o’clock, but I haven’t eaten anything yet and I don’t know when or where I’ll get anything. It might seem strange to some people, even incredible, but nevertheless it is so: I have jaws and teeth, I have a stomach and an appetite, which would like to put food in the stomach, but there is no food. At the same time the market is piled high with foodstuffs; I went there yesterday to take a look, because I had a cent or two in my pocket. I walked through row after row of berry-stalls to admire their abundance and freshness, and to sniff their almost entrancing smell. In some places I even asked the prices, where the garden strawberries were specially fresh and plump. When an old woman wanted to measure some out for me, I said I’d have to take a further look at the market and the prices, because I needed to buy a large amount. I chose the plumpest and most appetizing strawberries, and I asked the old lady what they cost because I wanted to taste, so I would know later where to buy from. She can’t sell berries for less than a cent, she said. I gave her two, and moved on. The woman shouldn’t have been thinking about the money; no, it was only a question of how the berries taste. That’s what it should be. But a beautiful berry eaten on an empty stomach just seemed sickly-sweet and plain watery. I felt very sorry to have wasted my two cents.

When I had suitably distanced myself from the rows of berries, I went to where they sell bread – black, brown and white – from tables behind which stood large carts or vans piled with supplies. In my pocket I counted out a handful of money to work out what to buy and how much. In the end, however, I didn’t buy anything here either, because it occurred to me there would be no point in carrying all that bread home, when right by the courtyard at home there is a shop where you can buy the same thing just as cheaply.

Generally it isn’t appropriate or polite for an educated young man in the street to carry a little packet whose shape reveals to everyone that it contains a piece of bread. It’s a different matter if your packet contains sweet buns, cakes or a tart – quite a different matter, because that implies certain relationships, acquaintances, adventures, delicacy and love. A piece of bread only speaks of hunger, which everyone considers to be a vulgar and crude thing demeaning to everyone who encounters it.

I Loved A German by AH Tammsaare is published by Vagabond Voices on 26 October priced £12.95. This edition is translated by Chris Moseley.

The Translation Fund, facilitated by Publishing Scotland, is now in its third year and encourages international publishers to translate works by Scottish writers by providing money toward the cost of the translation. Here Publishing Scotland’s Lucy Feather explains the process behind the funding and reveals some of the brilliant books from Scottish authors that have gone on to find new readers in Italy, Estonia, Croatia and many more.

The Translation Fund is now in its third year and was set up to encourage international publishers to translate works by Scottish writers by providing money toward the cost of the translation. We were delighted to be able to help Creative Scotland administer this project as it is a fantastic way of pushing Scottish writing to the forefront of the international publishing scene as well as getting fairly new authors a bigger audience. One of the criteria of the award is that the work is contemporary. Fiction, non-fiction, poetry, graphic novels and children’s literature have all received funding since the fund launched in 2015.

Kerry Hudson’s Tony Hogan Bought Me an Ice-cream Float Before He Stole My Ma published in Italian by Minimum Fax

Scottish authors works who have received funding for translation include Louise Welsh, Malachy Tallack, Graeme Macrae Burnet, Sara Maitland, Edward Ross, Lucy Ribchester, Allan Massie, Amy Liptrott, Jenni Fagan, Gavin Francis as well as more well-known writers such as Jackie Kay, Maggie O’Farrell, Ian Rankin, Ali Smith, Alexander McCall Smith, Nan Shepherd, James Robertson and James Kelman. Their mix of genre and talent is a great representation of all that is good on the current Scottish writing and publishing scene.

The reach thus far too has been brilliant – international publishers have received funding from countries such as Greece, Croatia, Bulgaria, Estonia, Norway, Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Macedonia, Istanbul, The Netherlands and Slovenia. And this year we have received applications from Russia, Korea and Sweden as well!

Jenni Fagan’s The Panopticon published in Croatian by Hena Com

The take-up of the fund is growing, which is great to see. Without doubt there is an interest in Scottish authors and a desire for them to be translated and sold overseas. Sadly it is not possible to fund all the applications that come in. The panel comprises former publishers, translators, writers and representatives from Publishing Scotland and Creative Scotland, who have a tough job making the decisions with the money available. They look for applications for books they feel would sell in that particular foreign market, the publishers back-list and how this title would fit, the budget and marketing plan provided from the applicant and very importantly the credentials of the translator assigned to the project.

It may be several months later that the translation project of a funded title is complete, and part of the criteria is that we are sent copies, one for the National Library of Scotland Legal Deposit archive and one for us. So it is a delight when they come in to the Publishing Scotland office and we see how the covers change and the impressions they give us can be so different in another language. We enjoy publicising the project and tweet pictures of these covers as they come in.

Ali Smith’s How To Be Both published in Italian by Big Sur

Overall, it’s a little insight into publishing houses from other countries and wonderful to see how we are able to influence their output a little with this fund. This fund is an exciting opportunity for international publishers to engage with Scottish material at a global level and we hope it will continue in the future.

Round 2 2016/17

There were 21 applicants for round 2 funding and 8 publishers and books received awards:

His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet in Estonian by Varrak

Haramada Publications, Greece, to translate Filmish: A Graphic Journey through Film – Edward Ross (Selfmadehero, 2015)

L’Altra Editorial, Spain, to translate This Must be the Place – Maggie O’Farrell (Tinder, 2016)

Ergon Publishing, Bulgaria, to translate School Ship Tobermory – Alexander McCall Smith (Birlinn, 2015)

Varrak Publisher, Estonia, to translate His Bloody Project – Graeme Macrae Burnet (Saraband, 2016)

The Undiscovered Islands by Malachy Tallack published in Norwegian by Vega Forlag

Vega Forlag AS, Norway, to translate The Undiscovered Islands – Malachy Tallack (Polygon/ Birlinn 2016)

Editions Metailie, France, to translate Dirt Road – James Kelman (Canongate, 2016)

Edition Steinrich, Germany, to translate A Book of Silence – Sara Maitland (Granta, 2008)

Crocetti Editore, Fondazione Poesia Onlus, Italy, to translate Darling – New & Selected Poems – Jackie Kay (Bloodaxe, 2007)

The Translation Fund was launched on 25 August 2015 at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. It is administered by Publishing Scotland, on behalf of Creative Scotland. Its purpose is to support publishers based outside the UK to buy rights from Scottish and UK publishers and agents by offering assistance with the cost of translation of Scottish writers. Find out more information about Publishing Scotland’s Translation Fund here.

This month our columnist dives head-first into the dynamic publishing practice of buying and selling rights in the international arena where risk needs to be balanced against reward. Robinson outlines the incredible journey of Babylon Berlin, bought by Dingwall-based Sandstone Press from a German publisher, as a stellar example of how Scottish independent publishing is truly international in ethos and ambition.

It’s October 2014 and Robert Davidson, publisher at Sandstone Press, is at the Frankfurt Book Fair when a German publisher asks him whether he’d be interested in buying a book from them.

Actually, adds the woman from Kiepenheuer & Witsch, it’s a series. The first four are already published in Germany: not best-sellers, but doing OK. They’re about a detective called Gereon Rath, and when the series starts, he is working undercover in 1929 Berlin. There will probably be another five, moving forward year by year towards the Second World War but stopping in 1939. Oh, and there’s talk of a series on German TV. Interested?

This, in essence, is what the world of rights is all about. Buy the English translation rights to Volker Kutscher’s series about Gereon Rath, and Sandstone Press can not only publish it in the UK but sell on those rights to America or Australia. But it’s an expensive business. Babylon Berlin, the first in Kutscher’s series, is over 500 pages long, so would cost at least £14,000 to translate. Margins are tight, and Sandstone is not a multinational with bottomless pockets but a small, albeit ambitious, publisher in Dingwall. Also, talk about TV deals is usually just that: talk. And Davidson doesn’t speak or read German. So, one more time: interested or not?

Me, I wouldn’t have been and here’s why. First, because I’d have to assume that all of those deep-pocketed multinationals had fallen asleep on the job. Every one of them – and what are the odds of that? Second, because I’ve already read a series like that in English: it’s by Edinburgh-born writer Philip Kerr, who started writing his hugely popular Bernie Gunther series back in 1989 with March Violets, has written 12 of them and hasn’t stopped. When it comes to fundamentally decent detectives trying to steer by their own moral compass through the Third Reich, in other words, there’s already one well-established fictional cop on the beat. And – reason No 3 – possibly with his own TV series lined up too: in April, the Sunday Herald claimed that HBO and Playtime, Tom Hanks’s production company, were working on a Bernie Gunther TV series. This, actor Woody Harrelson, has said, is the only role that would lure him back to the small screen.

Davidson, however, is made of gutsier stuff than me. Where I see only risk, he saw only opportunity. Kutscher has an outstanding track record as a writer in Germany, he says: his books sell, he makes a good living. Then there’s the question of authenticity: wasn’t it fascinating that here was a German writer exploring the darkest recesses of German history? Didn’t that give it an extra edge? Wouldn’t the background of Weimar’s high hedonism add to the appeal of the series? Didn’t we all love Cabaret? Beyond all of that, if Sandstone was ever to become the kind of company he envisioned – broad-based, international, independent and successful but one which just happened to be located on the inner Moray Firth – could it afford NOT to buy Babylon Berlin?

But what, you might be wondering, about that talk of an accompanying TV series back in 2014? Did it melt away, the way it usually does? Was it all just hot air and hype?

Interestingly, no. Babylon Berlin, which will be shown on Sky Atlantic in the autumn, will be the most expensive German television series ever made (40 million euros), with 250 speaking roles and 5,000 extras. Director Tom Tykwer (Run, Lola, Run, Cloud Atlas) wants to open up the action to the strife-ridden city – the streets, not just the interiors, which is mostly what we got in Cabaret – ‘and show how ordinary people like you or me could become fascists’.

And here’s another culturally significant change that might help: in Britain and the US, ordinary people like you or me now don’t mind watching well-made foreign TV. Last year, when Channel 4 screened Deutschland 83, it attracted 2.5 million viewers, making it the channel’s most popular foreign language TV series ever. The year before, it had been the first German series shown on a US network. Put the TV series for Babylon Berlin in the frame, and even I can see that I might have called it wrong had it been up to me back in 2015 – when Bob Davidson decided he was going to push the boat out and buy the book – and accept that he, in fact, got it right. Certainly, he’s been determined enough to make sure he got everything else right, from a ‘brilliant’ translation by Glaswegian Niall Sellar (with financial help from the Goethe Institute and XpoNorth) to ‘one of the best book jackets we’ve ever done’.

At this stage, I have yet to read Babylon Berlin, so have no idea how well it stacks up against Kerr’s Bernie Gunther novels. In a sense, it doesn’t matter. All I am looking at here is the strange balance between dreams and risk that buying rights involves.

Sometimes there mightn’t seem to be that much risk at all, but usually that is only because the publisher has already taken it and the book has gone on to win a prize. This – or even a shortlisting – makes selling rights a lot easier: after Daniel Shand’s Fallow won the Betty Trask Award in June, for example, Davidson had no problem selling rights to the US and Australia. A year ago, there was an even more spectacular example after the Man Booker longlisting of Graeme Macrae Burnet’s His Bloody Project, when Saraband publisher Sara Hunt was inundated with rights offers from all over the world. They’re now up to 25 deals, she tells me, more are in the pipeline and there will undoubtedly be still more when his third novel, The Accident on the A35, comes out in October.

Put like that, it all looks so easy. Strip out the hindsight and it’s not. ‘There hadn’t been too many successful literary novels centred on crime,’ says Hunt. ‘Hannah Kent’s perhaps, not many others. But I had spent such a long time trying to spread the word about Graeme’s book that seeing the rights sales flooding in was fantastic.’ Such levels of success might, she thinks, even have an effect on rights sales for completely unrelated books. ‘If you look at the popularity of Outlander and of His Bloody Project – they’re both quite different, but between them they have made Scottish historical fiction quite popular. A lot of colleagues have told me that at book fairs people have come by asking if they have any more Scottish historical fiction.’

Put like that, it all looks so easy. Strip out the hindsight and it’s not. ‘There hadn’t been too many successful literary novels centred on crime,’ says Hunt. ‘Hannah Kent’s perhaps, not many others. But I had spent such a long time trying to spread the word about Graeme’s book that seeing the rights sales flooding in was fantastic.’ Such levels of success might, she thinks, even have an effect on rights sales for completely unrelated books. ‘If you look at the popularity of Outlander and of His Bloody Project – they’re both quite different, but between them they have made Scottish historical fiction quite popular. A lot of colleagues have told me that at book fairs people have come by asking if they have any more Scottish historical fiction.’

Suppose you wanted to encourage that, or to make sure that rights for all kinds of books by Scottish writers or from Scottish publishers are sold throughout the world. How would you even begin to do it?

For the answer, you need to realise how books are bought and sold across boundaries, and for that you need to talk to people who sell rights. They’ll tell you that the only way to do it is to know the mind, tastes, and dreams of the buyer, and for that you need to meet them and talk to them face to face and find out if you’ve got anything they’d want, and if you haven’t, discover what they’re looking for. Talk to Scottish publishing’s rights experts and they’ll all agree that there’s one project that does just that, bringing international editorial managers and agents to Scotland so they can find out just what our publishers have to offer.

They’ll be coming again next week, nine international publishers (a different cohort each year) invited to Scotland via Publishing Scotland’s International Fellowship programme. Often, they will go back with deals in their pockets – if not now, then later. Last August, for example, Stephen Morrison, publisher at Picador USA, was one of the 2016 Fellows. They all went to Inverness, where Bob Davidson told them about the books he’d got on his list and his hopes for them. Morrison got back in touch in June about Babylon Berlin. Yes, he told Bob Davidson, he’d take the American rights. Definitely.

Publishing is a risk, always will be. If Babylon Berlin fails, Davidson told me, it would be a ‘significant setback’ for Sandstone. So far, though, it’s selling well, and I, for one, wouldn’t bet against him.

You can find out more about adapting Babylon Berlin for television in this recent article, ‘Nazis, Noir and Weimar Decadence: Babylon Berlin Recreates an Era for TV Detective Drama’, published by the Guardian.

Scotland Street Press, based in Edinburgh, acquired Glimpses of the Middle East by Patience Moberly whose diplomat husband became the British ambassador to Iraq under Saddam Hussein. After publication in English in the UK, Scotland Street Press then sold the rights for the book to be published in Arabic, where it’s been well received by a new readership. We present an extract from this insightful book below.

Extract from Glimpses of the Middle East

By Patience Moberly

Published by Scotland Street Press

Patience Moberly was born in 1923 and was one of the first women to qualify as a doctor from St George’s in London. Patience Moberly, and her diplomat husband John, were responsible for starting and training the first Intensive Care Unit in Gaza, they were founding members of Medical Aid for Palestinians, MAP. Any proceeds from this book will go to that charity.

Qatar

Two weeks after I was engaged, in 1959, my fiancé told me he had been posted to Qatar as a Political Agent, starting in eight weeks’ time. I’d never heard of the place.

“How do you spell that?” I asked.

“Q.A.T.A.R.”

“I suppose that is what I call Quetta.”

But of course it wasn’t, and eight weeks later we were landing in Kuwait in August, en route to this Sheikhdom in the Persian Gulf.

At that time in 1959 with their newly discovered oil, the Gulf Sheikhdoms were both potentially excessively rich and at the same time politically very vulnerable. Britain had a treaty arrangement with them to protect them from outside attack in exchange for conducting their foreign affairs, but the running of their internal affairs was entirely independent. In each Sheikhdom a British Foreign Office official called a Political Agent oversaw this arrangement under the overall guidance of a more senior diplomat in Bahrain called the Political Resident. The inhabitants of Qatar were, of course, mainly the Qataris themselves, ruled by their traditional Ruler, with a fairly large expatriate group consisting of Indian servants, professional Arabs and oil workers, the most senior of whom were predominantly British.

I got out of the plane that August day and looked around for the furnace that must clearly be nearby, because no climate could possibly be as hot as this. There was no furnace, it was just the Gulf on a nice cool summer evening. Twenty-four hours later we were staying in Bahrain for a night, before flying on to Qatar the next morning. Our Foreign Office host, standing in for his boss, the Political Resident, who was away at the time, had organised a supper party for us to meet various colleagues. I sat next to him and he began to talk about my husband’s new job.

“There’s a lot of unrest here at the moment,” he said. “If you had real trouble I suppose we might be able to get you out. The Consul in Mosul was killed recently by the mob. Head split open with a pickaxe, like a rotten orange. I hope we could get you out in time.” He obviously wasn’t convinced he could. He talked on, thinking about the problem. I assumed he must be giving me an unofficial warning that my husband of three weeks would probably shortly be killed. Somehow I managed to get through that terrible supper which seemed to go on forever, before we could go to bed. But how could I tell John it was likely he would soon be murdered? I waited till he was asleep, then put my head under the pillow and wept and wept.

The next morning in a little plane with the mail-bags, a man in a dishdasha, and a goat, we set off on the last leg of our journey. I was quite certain I would shortly be returning as a widow.

We were met at the Doha airport by John’s second in command, and there were also a crowd of people on the tarmac, who we supposed must be waiting for someone else. It turned out they too were part of our welcoming party.

“You’ll love it here,” they said, beaming. “So much better than stuffy old Bahrain.”

It was the beginning of two and a half fascinating years in what was still a medieval Arab society. There were no mobs with pickaxes.

From the nightmare of the supposed danger to John to an almost fairy-tale meeting with the Sheikh was only a matter of hours. The Ruler’s eldest son was giving a feast in our honour that evening. We drove out across the desert in the dark to a large fort-like building with turrets lit by neon lights and a huge door covered by an illuminated Qatari flag, like a scene from a Hollywood Arabian Nights. As we approached, the door was flung open and we were in a great courtyard filled with servants and retainers armed with guns and bayonets, dimly seen in the half-light. At another door on the other side the Sheikh, resplendent in his Arab robes, was waiting to greet us. We processed into a huge majlis, or reception room, carpeted in green with green velvet chairs round the walls and further chairs in the centre. It seemed all the rank and fashion of Qatar, both European and Arab, were there, nearly all men though with a few European women, who all came forward and shook John’s hand. Then everyone relaxed onto chairs and talked and drank Arabic coffee. I found myself between my husband and a cheerful beady-eyed Sheikh who I tried but failed to talk to in Arabic. Fortunately, not talking is not considered rude, which is a restful convention.

Scotland Street Press sold World Arabic rights for Glimpses of the Middle East by Patience Moberly at Frankfurt Book Fair 2016 to publisher Nasser Jarrous from Lebanon, whose life mission it is to foster good East-West relations through the world of publishing. It is now published in Arabic with an initial print run of 1000 copies.

Glimpses of the Middle East by Patience Moberly is out now published in English by Scotland Street Press priced £9.99.

Stornoway-based Acair publish a diverse array of books for adults and children in Gaelic, English and sometimes Scots. Here we showcase the art of translation by presenting a selection of poetry from Sorley MacLean with Derrick McClure, and Aonghas Pàdraig Caimbeul in different versions.

Meas Air Chrannaibh / Fruit On Branches

By Aonghas Pàdraig Caimbeul

Published by Acair

Translations available in Gaelic, Scots and English

“Ma tha neach cho beannaichte ‘s gu bheil gach cuid Gàidhlig agus Beurla aige, agus gu bheil ùidh aige ann an eadar-theangachadh, chanainn gun còrdadh an t-eadar-theangachadh a tha an seo gu math ris. Tha e, anns a’ chumantas, cuimseach agus ealanta… Ach ‘s ann anns na dàin fhein a tha an t-ionmhas.”

“If there is somebody so blessed as to be able to speak both Gaelic and English, who also holds a keen interest in the art of translation, I’d thoroughly recommend the following translation presented here. Generally, they are both accurate and artistic… But, it is within the poetry itself that lies the real treasure.”

– Dòmhnall MacAmhlaigh/Donald MacAulay

A’ Chuirm

Am pìobaire air thoiseach,

ged nach eil duine ag èisteachd ris a’ phort:

chan eil ann ach sealladh brèagha an fhèilidh,

agus am fuaim ag èirigh dha na speuran.

Tha a’ bhanais seachad

‘s gach neach air dhòigh: confeataidh is

clag nam camarathan ‘a tha ghrian a’ deàrrdadh

òr.

Seann bhanntrach taobh muigh na rèile

a’ guidhe gach beannachd air a chàraid-chèile:

an tè bu bhòidhche bh’ anns an t-saoghal

a’ faicinn tìm, le gàir’, ga trèigsinn.

The Waddin

First o aa, the piper,

naebody heedin his muisic, tho:

thay’re aa jist goamin at the glamour o ‘s kilt,

as the lilt spirls up tae the lift.

The waddin’s by,

an aabody’s cantie: confetti

an camera-clicks, an the sun glentin

gowd.

An auld weida outside the palins

prayin for ilka blessin on the ying fowk:

her at wes bonniest in aa the warld

watchin time as it rins lauchin awa.

The Celebration

The piper marching ahead,

though no one listens to his music:

everyone dazzled by the colours of the kilt

and the tune rising into the ether.

The wedding is sealed

and everyone well pleased: confetti

and the noise of cameras and the sun shining

gold.

An old widow outside the railings

praying every blessing on the newly-weds:

the most beautiful one in the whole world

watching time joyfully forsaking her.

Sangs Tae Eimhir

By Derrick McClure and Sorley MacLean

Published by Acair

Translations available in Gaelic and Scots

Ainmean nan Dàn

Dh’ fhoillseacheadh 50 dhen trì fichead Dàn do Eimhir a sgrìobh Somhairle MacGill-Eain air fad nuair a nochd an leabhar Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile ann an 1943 (ged a bha a dhà, VI agus XV, anns na ‘Dàin Eile’), ach cha tug MacGill-Eain ainm ach air ochd dhiubh. Ach nuair a nochd cuid dhe na Dàin do Eimhir ann an 1977 ann an leabhar de dhàin thaghte, Reothairt is Contraigh, cha robh iad idir ann mar shreath – ‘s ann a bha iad air an cur am measg nan dàn eile – is thug am bàrd an uair sin ainm air a h-uile gin a bha gun ainm. Thachair an aon rud anns a’ chruinneachadh O Choille gu Bearradh ann an 1989, ach gu robh tuilleadh dhe na Dain do Eimhir san leabhar sin – 36 air fad. ‘S iad na h-ainmean sin a chaidh a chleachdadh san leabhar seo, agus air sgàth gu bheil cuid dhe na Dàin do Eimhir nach do nochd san dà leabhar eile, tha iad sin gun ainmh fhathast.

Teitles o the Sangs

Frae among Sorley MacLean’s saxty Sangs tae Eimhir, 50 kyth’t in the buik Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile, furthpitten in 1943 (houbeit twa a thaim, VI an XV, wes amang the ‘Dàin Eile’ (Ither Sangs); but MacLean hed gien teitles jist tae eicht o thaim. In 1977, a curnie o the Sangs was inhauden in the outwale Reothairt is Contraigh, no in the oreiginal orderin but sparpl’t amang the ither poems in the buik insteid; an this time the makar hed gien ilkane o thaim a teitle. Mair o the Sangs – 36 aathegither – wes pitten intil the 1989 outwale O Choille gu Bearradh, aa wi teitles again. In the buik afore ye we hae uisit their teitles; but sen a whein o the sangs never kyth’t in aither o the twa outhales, thay bide wantin teitles still.

An DÙN ÈIDEANN: 1939

Tric ‘s mi gabhail air Dùn Èideann

baile glas gun ghathadh grèine,

‘s ann a lasadh e led bhòidhche,

baile lòghmhor geul-reultach.

IN EMBRA: 1939

Aft sic name I’d cry tae Embra:

toun sae gray, nae sun-glints dertin;

syne your fairheid set it lowein,

toun sae skyrie, starnie-splendant.

Meas Air Chrannaibh by Aonghas Pàdraig Caimbeul and Sangs Tae Eimhir by Sorley Maclean and Derrick McClure, are both available now from Stornoway-based Acair.

In this exclusive article Leah McDowell, Design & Production Manager of current Scottish Publisher of the Year Floris Books, takes us behind the scenes of her job to show how working with top international illustrations brings about beautiful new artistic interpretations of traditional Scottish tales for children. While the cross-cultural exchange between publisher and illustrator is mostly straightforward, on occasion Leah has been tasked with explaining what clootie dumplings, stooshie, and other Scots words are in her illustration briefs!

Illustration has a language of its own. No matter your cultural background or native tongue, human emotions are the same the world over. An illustrator’s job is to evoke that common emotion. Significantly for my job, an illustrator’s work isn’t limited by geographical borders.

Leah McDowell (left) showcasing some book covers from Floris Books with author Theresa Breslin (right)

As Design Manager of award-winning children’s publisher Floris Books, I spend a lot of time searching out new illustration talent. The UK has a wealth of emerging illustrators, many of whom can be found at art college degree shows and through conferences and exhibitions run by organisations like Picture Hooks. We also discover new talent through our own Kelpies Design and Illustration Prize, established in 2014 as a creative platform for emerging and established artists in Scotland to have their work recognised and celebrated.

Although Floris Books is Scotland’s largest children’s publisher, we are location-agnostic when commissioning illustrators. This is, of course, much easier in the digital age where the internet enables artwork to be easily showcased and has dramatically increased the discoverability of illustrators around the world.

Around half of Floris Books’ children’s books are in translation, and it’s particularly rewarding to be able to work with talented and often well-established illustrators from non-English language countries – such as Eva Eriksson, Daniela Drescher, Maja Dusikova, Pirkko-Lisa Surojegin and Sanne Dufft – bringing their work to the English-speaking world sometimes for the first time.

Additionally, people are often surprised by how many non-UK-based illustrators we work with for our Scottish children’s books, the Kelpies. Ruchi Mhasane, who lives and works in Mumbai, has illustrated two quintessentially Scottish books: folklore tale The Selkie Girl and My Luve’s Like a Red, Red Rose, a re-imagining of Robert Burns’ famous poem. Ruchi’s artwork is both lyrical and emotive, and her unfamiliarity with Burns’ poetry actually worked to our advantage as she was able to beautifully reframe the romantic poem as an expression of love between a mother and daughter.

It’s true that there’s often more that unites than divides us and our international illustrators have commented how they often see their own culture reflected back at them in our Scottish books. Vanya Nastanlieva’s soft but arresting portrayal of a bear in The Island and the Bear captures the muted, heathery tones of the Scottish Hebrides whilst also evoking her native Bulgaria. Likewise, Italian illustrator Alfredo Belli connected with the themes of war, courage and rebellion when he worked on the Bonnie Prince Charlie story, Speed Bonnie Boat.

It’s true that there’s often more that unites than divides us and our international illustrators have commented how they often see their own culture reflected back at them in our Scottish books. Vanya Nastanlieva’s soft but arresting portrayal of a bear in The Island and the Bear captures the muted, heathery tones of the Scottish Hebrides whilst also evoking her native Bulgaria. Likewise, Italian illustrator Alfredo Belli connected with the themes of war, courage and rebellion when he worked on the Bonnie Prince Charlie story, Speed Bonnie Boat.

That said, some of our international illustrators occasionally need a bit of guidance on the more obscure cultural references in our illustration briefs! I’ve had to send reference photos of clootie dumplings, Lewis chessmen and a tartan cat, as well as explain Scots words like stooshie, numpty and bahookie – often to the illustrator’s great amusement.

At a time when print sales are buoyant and we’re arguably experiencing a golden age of illustration, more than ever people desire beautiful books to discover, love and treasure – no matter where in the world the illustrations come from. It’s a privilege to be part of that discovery.

Leah McDowell is Design & Production Manager at Floris Books and recipient of the inaugural Saltire Society Emerging Publisher Award. She is passionate about bold typography, good kerning, and championing the work of illustrators. If you enjoyed this article then you might like this, When Is An Author Not An Author? When She’s An Illustrator, also by Leah on Books from Scotland.

Leah McDowell is Design & Production Manager at Floris Books and recipient of the inaugural Saltire Society Emerging Publisher Award. She is passionate about bold typography, good kerning, and championing the work of illustrators. If you enjoyed this article then you might like this, When Is An Author Not An Author? When She’s An Illustrator, also by Leah on Books from Scotland.

Floris Books is an independent Edinburgh publisher best known for its Scottish and international children’s books. Floris Books is the current Saltire Society Scottish Publisher of the Year.

Ahead of the new term Bright Red, based in Edinburgh, give insight into the fast-paced field of education publishing in Scotland and reveal how they work to support students and teachers throughout the year with dynamic activities and initiatives delivered across print and digital.

What has happened to the summer? The last round of SQA exams and end of term sports days seem like only moments ago and yet here we are in August again, with back to school just around the corner. And let’s not talk about the weather!