Following tremendous success in 2013 with The Ancient Pinewoods of Scotland, Clifton Bain now turns his attention to the mixed oak, birch and other woodlands that line the west coasts of north to south Scotland, Northern England, Wales and Ireland. Correctly described as a rainforest, these trees take a higher rainfall than some areas of the Brazilian rainforest, and since the Ice Age they have have provided resources for the human population, habitat for animals and birds, and acted as a lung for the planet.

Extract from The Rainforests of Britain and Ireland

By Clifton Bain

Published by Sandstone Press

North West Highlands

The ancient crofting counties of Sutherland and Ross embody the concept of wilderness. Expanses of peatland and heath are interrupted only by huge mountain peaks that rise out of the moorland in a landscape that is framed by an intricately carved coastline of rocky peninsulas, islets and magnificent sandy beaches. This is one of the least inhabited regions of Britain with much of the population living along the coast in villages accessed by narrow single track roads.

Depleted but still impressive oakwoods occur on the Kyle of Lochalsh above Balmacara and on the northern slopes of Loch Maree. Further north, at the natural limit of oak distribution around Loch a Mhuilinn, birch becomes the dominant tree, with large swathes of ancient birch woodland in Assynt and in Strath Coille na Fearna, south of Loch Eriboll, on the Sutherland coast.

Depleted but still impressive oakwoods occur on the Kyle of Lochalsh above Balmacara and on the northern slopes of Loch Maree. Further north, at the natural limit of oak distribution around Loch a Mhuilinn, birch becomes the dominant tree, with large swathes of ancient birch woodland in Assynt and in Strath Coille na Fearna, south of Loch Eriboll, on the Sutherland coast.

One of the great geological features of Scotland is the Moine Thrust where two of the earth’s great plates collide along a line that runs north east from the Sleat Peninsula on the Isle of Skye up to Loch Eriboll. Unimaginable forces have created complex upheavals that form great mountain ranges and later glacial erosion has exposed some of Britain’s oldest rocks, the Lewisian gneiss. In recognition of its importance as a landscape of geological interest, the North West Highlands has been designated as Scotland’s first European Geopark, with work underway to conserve the area and provide interpretation for visitors.

Remains of stone circles, ancient hill forts and later croft houses provide evidence of people having lived throughout the area for thousands of years. This was Norse country for many centuries then became part of the Scottish Clan system before the social upheaval of the 19th century Clearances where tenants were displaced to the coast or to the Americas, by landowners seeking profit from sheep farming.

In our modern, frantic world, the natural beauty and seclusion of the area provides an escape that attracts visitors from all over the world while being sufficiently remote and large to accommodate these travellers without losing its tranquility. The winding narrow roads here provide some of the most incredible and exhilarating views in Scotland and for the even braver there is the long distance mountain trail from Fort William to Cape Wrath.

- The Kyle of Lochalsh – Inverness railway line skirts the southern edge of the region. There are buses available from Inverness and Lairg railway stations on the east coast to most of the villages in the North West Highlands.

- Hotels Guest Houses and B&Bs are available around Kyle of Lochalsh, Kinlochbervie, Durness and many of the larger villages. Woods with major visitor facilities:

Loch Maree, Beinn Eighe – Scottish Natural Heritage

Balmacara – National Trust for Scotland

Scotland’s mountains and glens retain the secrets of the long and frequently violent geological history that has gone into their making. Volcanoes have played a major role in the creation of Scotland and the youngest, at sixty million years old, are responsible for much of the scenic splendour of the Inner Hebrides. The rocks composing many famous Scottish landforms, for example those found in Glencoe and in the Edinburgh district, are also the direct result of volcanism.

Extract from Volcanoes and the Making of Scotland

By Brian Upton

Published by Dunedin Press

Two million years ago, Scotland had arrived at its present northerly latitude. Simultaneously, there was a marked cooling of the world’s climate, especially in the North Atlantic region: Scotland had entered the Ice Age. This global cooling that started in the middle of the Miocene (about 14 million years ago) intensified after 3.4 million years ago. The most recent period of Earth history is the Quaternary (Latin: fourth; a reference to a previous subdivision of geological time into four units). The boundary between the Quaternary and the preceding Neogene Period is put at 2.6 million years ago; the Quaternary is further subdivided into the Pleistocene, which includes the glaciations, and the Holocene, from 11 700 years ago, when the last ice finally melted from Scotland, up to and including the present. Investigations of past climates in the Quaternary clearly indicate that the present warm stage is merely the most recent of relatively shortlived interglacials between glacial stages (or full ice ages) and that, if the pattern continues, we could be heading for another ice age within the next few thousand years. In other words, the Holocene can be seen as really just another interglacial. The present global warming is related to burning of fossil fuels (wood, peat, coal, oil and gas) and intensive agricultural practices: much carbon dioxide and methane are produced, which enhance the natural greenhouse effect, and this may delay the onset of the next ice age. On the other hand, we may be in for a surprise, since it is not yet fully understood how all the components of the climatic system interact, and disturbing the system may well produce quite unforeseen effects that cannot be predicted.

For human beings, the Quaternary is the most significant period in Earth history, since that is when modern humans first emerged. The most recent ice sheets put the finishing touches to the landscape of Scotland, and the soils developed only after the ice melted. It is also the best-understood period, since more of the evidence is still preserved and nearly all the animals and plants found as fossils in the Quaternary exist today. Thus, geological events in the Quaternary can be dated with remarkable accuracy.

In the annals of geology, Scotland is well known as being one of the first places where the existence of former glaciers was deduced, following on the observations of the Swiss geologist Louis Agassiz (1807–73), who visited Scotland in 1840 and studied various localities, notably Edinburgh, where he observed scratch marks on rocks in the valley of the Braid Burn, and the Spean valley and Glen Roy, where he interpreted the Parallel Roads as the signs of water levels in a former ice-dammed lake. Although these ideas were initially met with skepticism, James Croll championed the work of Agassiz and he himself went on to conduct important research on glaciation in Scotland. (Incidentally, Agassiz was a paleontologist who specialized in studying fossil fish, and he was influenced by Hugh Miller’s collection from the Black Isle.) Many of the landforms produced during and after the most recent ice age are important internationally, including in particular the suite of landforms in the Cairngorms. Here we find remnants of the pre-Quaternary landscape still preserved, as well as superb examples of glacial-erosion features (such as corries and glacial troughs), glacial deposits (moraines and meltwater features), and evidence of more recent changes associated with permafrost and the establishment of plant communities and environmental changes over the past 11 700 years.

In 1952 Linda Cracknell’s father embarked on a hike through the Swiss Alps. Fifty years later Linda retraces that fateful journey, following the trail of the man she barely knew. This collection of walking tales takes its theme from that pilgrimage. The walks trace the contours of history following writers, relations, and retreading ways across mountains, valleys, and coasts formerly trodden by drovers, saints, and adventurers. Each walk reaffirms memories, beliefs and emotions, and the connection that one can have with the past through particular places. This book celebrates life, family, friendship, and walking through landscapes richly textured with stories.

Extract from Doubling Back

By Linda Cracknell

Published by Freight Books

A hillside near Abriachan,

Loch Ness

Spring there is more than colour; it is music and scent. The burns literally

hum down the hillside, the trees have rhythm in their shaking.

Ness MacDonald, ‘Country Dweller’s Year’, Scots Magazine, April 1946

Despite late April sunshine, spring was still holding its breath when I arrived on ‘her’ hillside. I was a thousand feet up at Abriachan, where a dormer-windowed house straddles lush pastureland below and the scratch of heather on the open moor above. This is Achbuie where at the age of nineteen, writer Jessie Kesson (1916-1994) came after a year of virtual imprisonment in a mental hospital. She was ‘boarded out’, as the practice was known, living with and helping an elderly woman on her croft. Amongst the smell of bracken-mould and primroses, on a hill so high and steep that, as she said, ‘you feel any moment you might topple into Loch Ness below’, she rambled freely for the six months or so that she stayed. The visceral thrill of the place in springtime pulses through her writing in different genres ever after.

It was curiosity about this powerful influence that took me there in early spring. I wanted to share her exuberance and find the Red Rock she wrote about. And there, high on the moor to the northeast of Achbuie, seen through my wind-tugged hair – a slash of steep gully sliced inland from the Loch into a south-facing cliff. Red and crumbly, fissured in long downward strikes, a superb visual play was created by the orange-red of newly exposed rock against the petrolglazed blue of age. I knew from Isobel Murray’s biography Writing her Life that as Jessie ran and rambled across the hillside here she was followed by a stream of younger girls intrigued by her supposed ‘experience’. With its precipitous pathways of loose rock, I could see the lure for a gaggle of youngsters. This was at the far reaches of Abriachan, at the door to another world, edgy and dangerous and out of sight of the cottage and a watching old lady. Rites of passage were played out here according to Jessie’s writing – a childish game came close to an early sexual adventure. Later, her courtship with her future husband, John Kesson, who quarried the red sand rock, involved meetings on Sunday afternoons. Lying in the shadow of the red rock, they used ‘The Book’, which she was required to carry on the Sabbath, as a pillow.

That day in late April I climbed above the red rock to where the open moor levels. The wind carved down the lochside, and the bare birches rang maroon against a clear sky. Deer poured uphill on winter-dusky heather whose wiry stems snapped at my bootlaces. I kept turning, wondering whose step it was that caught at the back of mine, half expecting to find a line of children in a giggling retreat. Before dropping towards Caiplich I savoured the long views that Jessie wrote of in I to the Hills through the eyes of a character called Chris: ‘High up in the shadow of the Red Rock, she would lie, knowing that never in a lifetime could she absorb the changing moods and varying beauty of the vista unfolded below her.’ I gazed southwards towards Fort Augustus and the steep-sided finale of the Loch. On its east side, beyond water-pocketed escarpments, the Cairngorms displayed long low-reaching fingers of late snow. To the north-east, the Moray Firth and the sea’s horizon sparkled, the lure that perhaps took the young Jessie away to Inverness, next returning to Abriachan for her honeymoon, and repeatedly afterwards in

words.

Up on the open moor, the curlew burbled its high lilt. Peewits crashed within a whisper of the earth as they performed their jitterbug aerobatic displays. The notes they beat in the air with their broad wings seemed reassuring heralds of the spring. ‘Soon, soon’, they soothed.

Eagles, perhaps more than any other bird, spark our imaginations. These magnificent creatures encapsulate the majesty and wildness of Scottish nature. But change is afoot for the eagles of Scotland: golden eagles now share the skies with sea eagles after a successful reintroduction programme. In The Eagle’s Way, Jim Crumley draws upon his years of observing these spectacular birds to paint an intimate portrait of their lives and illustrate how they interact with each other and the Scottish landscape.

Extract from The Eagle’s Way

By Jim Crumley

Published by Saraband Books

THE GOLDEN EAGLE GLEN ends abruptly in a wide headwall, lightly wooded with mostly birch, craggy, bouldery, and bisected by a white-knuckled burn whose procession of ragged waterfalls echoes far down the relative tranquillity of the glen. The best way from the watcher’s rock to the watershed is to keep the burn’s company. It was here one late June evening, with breeze enough to deter the worst of the midges and the glen softened by shadow after a long day of sunshine, that I toyed with the idea of spending the brief hours of pale darkness up on the watershed to watch the sunrise on the eyrie crag and see what unfolded.

Then the ring ouzel started singing. The song is full of jazzy rhythms and a tendency to belt out one haunting note again and again, like Sweets Edison used to do (if you know your jazz, Sweets is best known for his muted trumpet wiles filling in the spaces on the best albums of Sinatra, Ella, Tony Bennett). On and on, mellifluous and fluent, chorus after chorus, the song flowed like mountain burns, and then I had the notion that I would like to sit where I could see the singer, but without the singer seeing me. So I crawled away from the rock, my chin in the heather, one slow yard at a time.

The ouzel was in a low, scrubby birch tree by the burn and mercifully with his back to me. I crawled into the lee of a smaller rock, put my back to it and simply sat there. If he turned round I would be in full view, but I was dressed in something like the shades of the rock and the land, and I was silent and still and these things always help. Then the fox showed up. It was trotting along its accustomed path, one-fox-wide, but as it neared the ouzel’s tree it slowed its pace then stopped. Then it sat. Then it put its head on one side. And if you were to ask me what I think it was doing, and if I thought you were not the kind of person easily given to ridicule, I would tell you that I think it was listening to the music, as I was myself. But now I was listening to the music while also watching the fox listening to the music while both of us were also watching the musician, who seemed to be oblivious to both of us. For three, perhaps four minutes, this situation prevailed, and a moment of my life was attended by the most enduring magic.

It all ended abruptly. The ouzel simply stopped singing of its own accord, and flew off into the deepening shadows of the burn. The fox scratched its nose with a forepaw, stood up, and wandered off. I sighed out loud, still under sorcery’s spell. The truth is that I don’t really know what the fox was doing, only that it seemed to be fascinated by the bird and the only fascinating thing the bird was doing was singing. Nothing in the fox’s behaviour suggested it was stalking the bird. And as far as I could see, it was doing exactly what I was doing, nothing more, nothing less.

I know this though. If you spend a lot of time in one place with one overriding purpose centred on one particular species (in this case, the eagle glen and the eagles), you also acquire an onlooker’s knowledge of at least some of the eagles’ neighbours and fellow-travellers, just because you are out there and for long periods you are quite still and the neighbours and the fellow-travellers go about their workaday business and you see at first hand how they get on with each other and how they treat you like a bit of the landscape.

In this masterpiece of nature writing, Nan Shepherd describes her journeys into the Cairngorm mountains of Scotland. There she encounters a world that can be breathtakingly beautiful at times and shockingly harsh at others. Her intense, poetic prose explores and records the rocks, rivers, creatures and hidden aspects of this remarkable landscape. Shepherd spent a lifetime in search of the ‘essential nature’ of the Cairngorms; her quest led her to write this classic meditation on the magnificence of mountains, and on our imaginative relationship with the wild world around us. Composed during the Second World War, the manuscript of The Living Mountain lay untouched for more than thirty years before it was finally published.

Extract from The Living Mountain

By Nan Shepherd

Published by Canongate Books

Summer on the high plateau can be delectable as honey; it can also be a roaring scourge. To those who love the place, both are good, since both are part of its essential nature. And it is to know its essential nature that I am seeking here. To know, that is, with the knowledge that is a process of living. This is not done easily nor in an hour. It is a tale too slow for the impatience of our age, not of immediate enough import for its desperate problems. Yet it has its own rare value. It is, for one thing, a corrective of glib assessment: one never quite knows the mountain, nor oneself in relation to it. However often I walk on them, these hills hold astonishment for me. There is no getting accustomed to them.

The Cairngorm Mountains are a mass of granite thrust up through the schists and gneiss that form the lower surrounding hills, planed down by the ice cap, and split, shattered and scooped by frost, glaciers and the strength of running water. Their physiognomy is in the geography books – so many square miles of area, so many lochs, so many summits of over 4000 feet – but this is a pallid simulacrum of their reality, which, like every reality that matters ultimately to human beings, is a reality of the mind.

The plateau is the true summit of these mountains; they must be seen as a single mountain, and the individual tops, Ben MacDhui, Braeriach and the rest, though sundered from one another by fissures and deep descents, are no more than eddies on the plateau surface. One does not look upwards to spectacular peaks but downwards from the peaks to spectacular chasms. The plateau itself is not spectacular. It is bare and very stony, and since there is nothing higher than itself (except for the tip of Ben Nevis) nearer than Norway, it is savaged by the wind. Snow covers it for half the year and sometimes, for as long as a month at a time, it is in cloud. Its growth is moss and lichen and sedge, and in June the clumps of Silence – moss campion – flower in brilliant pink. Dotterel and ptarmigan nest upon it, and springs ooze from its rock. By continental measurement its height is nothing much – around 4000 feet – but for an island it is well enough, and if the winds have unhindered range, so has the eye. It is island weather too, with no continent to steady it, and the place has as many aspects as there are gradations in the light.

Light in Scotland has a quality I have not met elsewhere. It is luminous without being fierce, penetrating to immense distances with an effortless intensity. So on a clear day one looks without any sense of strain from Morven in Caithness to the Lammermuirs, and out past Ben Nevis to Morar. At midsummer, I have had to be persuaded I was not seeing further even than that. I could have sworn I saw a shape, distinct and blue, very clear and small, further off than any hill the chart recorded. The chart was against me, my companions were against me, I never saw it again. On a day like that, height goes to one’s head. Perhaps it was the lost Atlantis focused for a moment out of time.

J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) was perhaps the most prolific and innovative of all British artists. His outstanding watercolours in the collection of the National Gallery of Scotland are one of the most popular features of its collection. Bequeathed to the Gallery in 1899 by the distinguished collector Henry Vaughan, they have been exhibited, as he requested, every January for over 100 years. Renowned for their excellent state of preservation, they provide a remarkable overview of many of the most important aspects of Turner’s career.

This new richly illustrated book provides authoritative commentary on the watercolours, taking account of recent research to address questions of technique and function, as well as considering some of the numerous contacts Turner had with other artists, collectors and dealers.

Extract from J.M.W. Turner: The Vaughan Bequest

By Christopher Baker

Published National Galleries Scotland

Turner left the Borders on his 1831 tour of Scotland and then embarked on a journey to the Highlands, travelling alone. He discussed with the publisher Cadell a list of suitable subjects he might work up to illustrate Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake and The Lord of the Isles, and decided to travel as far as Fingal’s Cave on Staffa and the remote Loch Coriskin (Coruisk) amid the Cuillins on the Isle of Skye.

On reaching the loch, Turner made a number of brief pencil sketches from the precipitous slopes surrounding it, but none of them precisely relates to this spectacular watercolour, which must have been composed slightly later. It was engraved in 1834 by Henry Le Keux, as the frontispiece to volume ten of Robert Cadell’s edition of Scott’s Poetical Works, which contained the author’s The Lord of the Isles.

Turner conceived the scene as two vortices in which the rocks and turbulent weather appear to fuse; similar compositional ideas can be seen, although less fully developed, in the artist’s 1819 depiction of Ben Arthur which formed part of his Liber Studiorum series of prints (fig.32). It has been suggested that Turner may also have drawn at least part of his inspiration for Loch Coruisk from the work of the Scottish descriptive geologist John MacCulloch (1773–1835). Turner could have met MacCulloch as early as 1814, and acquired from him volumes of The Transactions of The Geological Society. MacCulloch, who was reported to be ‘delighted with [Turner’s] acute mind’, published his Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland in four volumes in 1824. It took the form of a series of letters to Sir Walter Scott, whom he had known since the 1790s, and included very powerful, evocative descriptions of sites that Turner was to visit. According to MacCulloch, when he saw the loch:

Turner conceived the scene as two vortices in which the rocks and turbulent weather appear to fuse; similar compositional ideas can be seen, although less fully developed, in the artist’s 1819 depiction of Ben Arthur which formed part of his Liber Studiorum series of prints (fig.32). It has been suggested that Turner may also have drawn at least part of his inspiration for Loch Coruisk from the work of the Scottish descriptive geologist John MacCulloch (1773–1835). Turner could have met MacCulloch as early as 1814, and acquired from him volumes of The Transactions of The Geological Society. MacCulloch, who was reported to be ‘delighted with [Turner’s] acute mind’, published his Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland in four volumes in 1824. It took the form of a series of letters to Sir Walter Scott, whom he had known since the 1790s, and included very powerful, evocative descriptions of sites that Turner was to visit. According to MacCulloch, when he saw the loch:

I felt as if transported by some magician into the enchanted wilds of an Arabian tale, carried to the habitation of the Genii… I felt like an insect amidst the gigantic scenery, and the whole magnitude of the place became at once sensible.

Turner has placed tiny insect-like figures, perhaps including himself, in the foreground, so establishing a sense of scale and awe.

For centuries pilgrims have travelled to the isle of Iona in search of the sacred, inspired by the example of St Columba, a sixth-century Irish monk who founded a monastery there, and whose influence is felt to the present day. Many modern-day pilgrims and seekers are also drawn to the island.

This book is a rich collection of readings, prayers, poems, photographs, songs, stories and reflections. Island visitors and armchair pilgrims alike are invited to take a prayerful, perhaps life-changing, journey around what George MacLeod, the Founder of the Iona Community, described as a “thin place”, where only a tissue paper separates the material from the spiritual.

Extract from Around a Thin Place

By Jane Bentley and Neil Paynter

Published by Wild Goose Publications

To Get to Iona

By Ruth Burgess

To get to Iona

it takes me

the Underground

three trains

a coach

two ferries

and a fair bit of walking.

To get to Iona

it takes me

sandwiches

coffee

sweets

a bottle of water

and sometimes

on the boat

an egg-and-bacon butty.

To get to Iona

it takes me

timetables

The Guardian quick crossword

a book

a pen and some paper

and whatever magazines

people leave behind them

on the trains.

To get to Iona

it takes me

smiles

conversations

laughter

listening

memories

and often tears.

To get to Iona

it takes me

risks

prayers

work

wonder

minutes and days

and the passing of years.

That’s what it takes me

to get to Iona.

What will it take you?

Scotland’s Still Light explores the relationship between photographic imagery and the words of some of Scotland’s most highly respected writers. It is not an attempt to illustrate the texts but to give a sense of place through the combination of words and images. Sometimes it is a whole piece, sometimes a paragraph or verse, a few lines, or occasionally a single line that encapsulates the experience of trying to capture ‘the moment’ with a camera.

All of the photographic images evolve from a study of the unique quality of light that prevails in the exquisite diversity of Scotland’s landscapes and cities.

Extract from Scotland’s Still Light

By Andy Hall

Published by Luath Press

Assynt, Sutherland

Who possesses this landscape? –

The man who bought it or

I who am possessed by it?

False questions, for

the landscape is

masterless

and intractable in any terms

that are human.

from ‘A Man in Assynt’ by Norman MacCaig (1910-1996)

The Ayrshire Coast

A county shaped like an amphitheatre. Bent like the crescent moon. The only Scottish shire with a face towards Ireland. My mind ran to the tops of the hills as the train moved on. Up go the eyes of the rabbits and owls. They peer from the uplands of Kyle and Cunninghame, and so do the eyes of the people in their high farms, who are mad for the sea, and who applaud the roar from their rocky seats, their island view from the upper tier. I felt them near to me. I felt their breaths at the window.

from Our Fathers by Andrew O’ Hagan

The time came when, thrilling as a pipe lament across the water, daylight announced it must go: there was a last blaze of light, an uncanny clarity, a splendour and a puissance; and then abdication began. Single stars appeared, glittering in a sky pale and austere. Dusk like a breathing drifted in among the trees and crept over the loch. Slowly the mottled yellow of the chestnuts, the bronze of beech, the saffron of birches, all the magnificent sombre harmonies of decay became indistinguishable. Owls hooted. A fox barked.

The time came when, thrilling as a pipe lament across the water, daylight announced it must go: there was a last blaze of light, an uncanny clarity, a splendour and a puissance; and then abdication began. Single stars appeared, glittering in a sky pale and austere. Dusk like a breathing drifted in among the trees and crept over the loch. Slowly the mottled yellow of the chestnuts, the bronze of beech, the saffron of birches, all the magnificent sombre harmonies of decay became indistinguishable. Owls hooted. A fox barked.

from The Cone Gatherers by Robin Jenkins (1912-2005)

Glasgow

After a moment the voice said in a dry academic voice “The river Clyde enters the Irish Sea low down among Britain’s back hair of islands and peninsula. Before widening to a firth it flows through Glasgow, the sort of industrial city where most people live nowadays but nobody imagines living. Apart from the cathedral, the university gatehouse and a gawky medieval clocktower it was almost all put up in this and the last century” – “I’m sorry to interrupt again”, said Lanark, “but how do you know this? Who are you anyway?”

“A voice to help you see yourself.”

from Lanark by Alasdair Gray

The Mearns, Kincardineshire

The folk who wrote and fought and were learned, teaching and saying and praying, they lasted but as a breath, a mist of fog in the hills, but the land was forever, it moved and changed below you, but was forever.

from Sunset Song by James Leslie Mitchell (Lewis Grassic Gibbon) 1901 – 1935

Inspired by the Oscar-nominated Netflix documentary, this is the story of the real Miss Simone.

What Happened, Miss Simone? tells the story of incandescent soul singer and Black Power icon Nina Simone, one of the most influential, provocative, and least-understood artists of our time. Drawn from a trove of rare archival footage, audio recordings and interviews (including Simone’s remarkable private diaries), this nuanced examination of Nina Simone’s life highlights her musical inventiveness and unwavering quest for equality, while laying bare the personal demons that plagued her from the time of her Jim Crow childhood in North Carolina to her self-imposed exile in Liberia and Paris.

Extract from What Happened, Miss Simone?

By Alan Light

Published by Canongate Books

In 1966, Simone made a dramatic, public change, one that would prove pivotal in redefining her image and her role as a cultural leader.

“The first time I wore my hair African was after Pastel Blues,” she said. “It reflected black pride, and that’s when I changed it. I identified a lot with Africa, and learned what they did, and started wearing my hair in an Afro.”

Her archivist and friend Roger Nupie tracked this revolutionary new look with a more regal bearing on- and offstage. Early on, he pointed out, she was wearing a wig in her photo shoots and on her album covers, as most black singers and actresses did in an effort to conform to white conventions. But Nina was the first celebrity to wear an Afro and dress in African styles. “The ‘black beauty’ thing started around those days,” he said, “and it was very important that somebody like Nina Simone came onstage and was there in a very proud African way. And from that moment, her attitude changed completely, because when she comes on it’s like ‘Here I am. Who am I? I’m an African queen’—or, as she sometimes said, the reincarnation of an Egyptian queen.”

This decisive change represented a rejection of standards of white beauty—standards that Simone had been acutely aware of her whole life. In her diaries, she complains about the photographs chosen for her album covers, and her husband-manager Andrew “Andy” Stroud noted that Simone had long struggled with her self-image. “She would get very depressed at times staring into the mirror,” he said. “Even though she was so committed to the black cause and preached it and everything, most of her friends were white. So she’s crying about her hair and her other features. Before she got her teeth capped, they weren’t that nice. It came from deep inside—she was just unhappy to be black, and what she termed ugly.”

In her private writings, Nina revealed this agony regarding her appearance. In one undated note, she wrote: “I can’t be white and I’m the kind of coloured girl who looks like everything white people despise or have been taught to despise—if I were a boy, it wouldn’t matter so much, but I’m a girl and in front of the public all the time wide open for them to jeer and approve of or disapprove of.” She went on to describe herself as “some- one who has been brainwashed to think everything they do is wrong . . . someone who’s been robbed of their self respect their self esteem some one’s who’s been convinced they have no right to be happy. But then why haven’t I killed myself?”

The change in her outward appearance, then, was obviously about more than just style—to use a phrase becoming popular around this time, she was realising that the personal is political. The new hair coincided with her increasing interest in black pride and a growing engagement in activism. In a diary entry written in February 1966 in South Bend, Indiana, there’s a short but critical sentence scrawled at the end: “I decided today that I wanted to be more Active in civil rights.”

Since Mississippi Goddam, she had been closely associated with the movement, performing at benefits and speaking out onstage. She later said, though, that she had initially been propelled into activism by raw emotion but had been slower to engage with its arguments and ideas. “The civil rights movement was something that I got into before I became fiercely political,” she said. “I was just doing it because—well, I loved it. I approved of what they were doing, but I didn’t talk about it a lot. I was just composing songs to spur them on.”

To Nina, “politics” was rooted more in her work and her example than in organising and legislating; what resonated was an idea, the model of independence and pride she practiced—as she told Vernon Jordan, “I am civil rights!”— rather than strategic action. “I didn’t educate myself very well,” she said. “I was so busy working that there wasn’t time to reflect on what I was doing.”

Later, she would even claim that she was moving at such great speed that she had no real recollection of such historic events as her trip to Selma. “My mind during this time was on automatic,” she said. “I don’t remember most of this job because all I did was work, work, work. At times people’s faces are not even clear in my mind. I’m sure that stacked somewhere in the back of me when I’m not so tired is all this memory. I don’t remember doing all this.”

In some ways, it was as if she was providing a soundtrack for a community that she wasn’t entirely able to connect with. “One of the things she said to me was that she really felt bad that she was not more active in marching and protesting and things like that,” said civil-rights activist Andrew Young. “And I thought how very strange and odd for her to say that. One of my friends who was there commented to me later, ‘God, she was so present—she was everywhere, in all our projects, in all our work.’ What she was doing, going around the country spreading the word of the movement—nothing was as cogent of the frailty and the humiliation and the sadness and the joy of what we did than her music.

“More than any other artist, I think that her music depicted and reflected the time. It just seemed to be so very current, so very fluid, and expressed so completely the aspirations, the anxiety, the fear, the love, the rejection, the hurt, the horror, the anger of what we were feeling at the time. Her music always seemed to be so on top of our situation.”

Mongol [mong-gohl], noun, 1. a member of a pastoral people now living chiefly in Mongolia. 2. (offensive) a person affected with Down’s Syndrome. Uuganaa is a Mongol living in Britain, far from the world she grew up in: as a nomadic herder she lived in a yurt, eating marmot meat, distilling vodka from goat’s yoghurt and learning about Comrade Lenin. When her new-born son Billy is diagnosed with Down’s Syndrome, she finds herself facing bigotry and taboo as well as heartbreak. In this powerful memoir, Uuganaa skilfully interweaves the extraordinary story of her own childhood in Mongolia with the sadly short life of Billy, who becomes a symbol of union and disunion, cultures and complexity, stigma and superstition – and inspires Uuganaa to challenge prejudice.

Extract from Mongol

By Uuganaa Ramsay

Published by Saraband Books

‘Kiss me again,’ I said to my father, who was about to go through the Departure gate at Glasgow Airport. ‘Why aren’t you kissing me on my forehead like you used to?’ I was looking for the comfort his kisses had been bringing me ever since I was a child. But he had thought the loose and awkward hug he’d given me earlier was ‘what you do here’.

It was only March and already it was the second time he’d left Scotland this year. The middle of March in Glasgow is still winter – dark, wet and windy. We were both desperately trying hard not to sob. It is considered bad luck to cry when you say goodbye in Mongolia. I can hold on to my emotions when I say my goodbyes, even if it is to my parents, my sister or my husband. This time it was different. I was fragile and feeling vulnerable, ready to shed tears in gallons. I knew my dad was feeling the same when he quickly kissed my forehead then turned away before our tears started rolling down. As he walked away I saw him drying his eyes before turning round for a final wave.

***

Three months earlier, after Billy had been born, I had said to Dad over the phone, ‘You have to come here. I will never forgive you if you don’t.’ So he had dropped everything and come from the other side of the world, from one of the remotest places on Earth – Outer Mongolia, the country where I had been raised and had lived for the first twenty-odd years of my life. My sister told me later that he had said, ‘My girl doesn’t cry that easily, but she sobbed on the phone. I need to go.’

At that point I’d been on my own in a room at the maternity hospital. I had asked for a single room while they were deciding where to move me from the Labour ward. I couldn’t bear to look at other happy mums with their newborns, showing off their ‘perfect’ babies.

When I had gone routinely to see the midwife on Friday 13th November, I had been checked by a student who suggested the baby was in a breech position. Lynne, the midwife, had looked surprised and had checked my bump herself. ‘Yes, it is a breech. As soon as you feel any contractions, phone the hospital immediately and go there.’ The baby was due two weeks later and I didn’t really think it was a big issue, knowing that I had been breech myself at birth, stuck with one leg out and giving my mum a hard time. That was in rural Mongolia in the 1970s. Now, here in Britain in 2009, I obviously had nothing to fear. They have all that they need – medical equipment and experts in this field. This should be routine, I thought.

Later that night, after having a Chinese takeaway, the contractions started to come. My husband Richard picked up the car key. ‘Come on, we’ll go to the hospital. You give them a call; I’ll get the car ready.’ We rushed to the maternity hospital leaving our other children Sara and Simon with my mum, who had arrived on her own from Mongolia just the week before. My mum was holding some milk in a bowl; she drizzled some of it on the car wheels and sprinkled some in the air after wishing us all the best, and hoping all would go well. That was her way, the Mongolian way, of wishing you the best for the future. My dear little mum in her green deel (the traditional Mongolian tunic, similar in length to a coat), looking worried, was trying not to offend anyone in a strange new culture, making an awful lot of effort to learn English, feeling vulnerable and powerless. Yet she is a smart, educated woman who works in a secondary school in Uliastai, a small rural town in the western part of Mongolia.

After waiting for eight hours, at about 2am the next morning it was my turn to have a C-section. I was excited; the operation was going to be nothing compared to seeing my baby. Oh, the sensation was so good when the spinal anaesthetic kicked in. Pain-free, I was ready to see my baby with my husband beside me holding my hand, both of us excited, although I could tell that he was worried, seeing me on an operating table surrounded by surgeons, nurses and an anaesthetist.

Soon after that, Billy was born, my tiny little boy, 2.5 kilos, a kilo smaller than his brother and sister had been at birth. The doctors started to check Billy immediately just like any other baby. Richard tried to look at him from where he was sitting and gasped, ‘He is blonde!’ with disbelief. ‘Does he have the Mongolian blue spots?’ I smiled. Mongolians are proud of this birthmark. Usually these blue spots appear on Asian babies when they are born and then disappear after a few months. They were still stitching me up. I then noticed a worried look on Richard’s face. They seemed to be just too busy checking if Billy was all right. Then they decided to take him to the Neonatal unit. I asked, ‘Please, can I see my baby before he goes?’ They showed him to me from a distance as if they were hiding something and rushed him out of the room.

A meticulously researched, semi-fictionalised account of the Mauricewood pit disaster near Edinburgh of 1889, related by seven year-old Martha and her step-mother Jess. Their accounts are given in the aftermath of the death of Martha’s father and 62 others in the accident. With many of the miners’ families left destitute, the women of Mauricewood undertake a campaign for compensation and justice against the criminally negligent pit owners with key figures of the day, such as Keir Hardie and William Gladstone, playing roles in the cause célèbre. Alexander mixes historical fact and compelling fiction to create a gripping historical drama with a strong political resonance.

Extract from The Mauricewood Devils

By Dorothy Alexander

Published by Freight Books

I don’t think you ever get over something like Mauricewood. I suppose I was lucky in that the whole town suffered and I had my mother and father and my sister to help me. I wouldn’t have coped half as well if I hadn’t had them – and Sadie.

Sadie was my best friend from when we were children. We’d stayed in the same street and our mothers were friends. Her father was killed when he was just a young man. He fell off a roof and they brought him home on an old door. After that, my mother would often make an extra lot of soup and I’d be sent over with it in a bowl with a tea towel over the top. I didn’t dare trip. Or if she was baking – my mother was a lovely baker – something always went across the road. Sadie was as often as not at our house. She was a right character, full of fun and cheery. She had the bonniest black hair and big brown eyes. She was always small, and I was always bigger than her. And she loved singing. Her father had been a singer; he’d known all the old songs, the bothy ballads, and she was a quick learner, too quick her father said. She shouldn’t have been singing some of those songs. We didn’t know the half of what they were about. We just giggled because we knew they were about courting and how you got babies and that we didn’t dare sing them at Sunday School.

From the writer of one of the most famous Gaelic songs of the 20th century comes a collection of remarkable, and previously unpublished, poems. Maraiche nan Cuantan is one of the most well-known songs in the contemporary Gaelic culture of Scotland, and was composed by Flòraidh NicPhàil. Now, for the first time in print, readers have the opportunity to read for themselves the full extent of Flòraidh’s poetic talents in this exquisite poetry collection, including translations by the poet. The ‘bàrd baile’ tradition that Flòraidh writes in was once very popular in Highland and Island communities. It is now quite rare, which is what makes Flòraidh’s poems particularly unique.

Extract from Maraiche nan Cuantan

By Flòraidh NicPhàil

Published by Acair Books

“Gròc, Gròc,” Ars am Fitheach

’N d’ rinn thu cron an-diugh?

Rinn tòrr.

Dè rinn thu?

Ghoid mi bròg.

Cò bu leis i?

Oighrig òg.

An robh i snasail?

Cuaran òir.

Càit a bheil i?

Starsnaich Dheòrs’.

Deòrsa Foirbheach?

Abair spòrs!

Am faca duin’ i?

Ciorstaidh chòir.

A’ chabag bheag ud?

An dearbh òigh!

Is thog i naidheachd?

Mar bu nòs.

An tug e omhail?

Ruaidh à ghruaidhean

Mar an ròs!

“Caw! Caw!” Said the Raven

(English Translation)

Have you been up to mischief today?

I have indeed.

What were you up to?

I stole a shoe.

To whom did it belong?

Young Effie.

Was it fancy?

A gold sandal.

Where is it?

In George’s doorway.

George the Elder?

What a joke!

Did anyone see it?

‘Kindly’ Kirsty.

That wee gossip?

The very one!

And she spread the story?

As usual.

Was he aware of it?

His cheeks reddened

Like the rose!

It’s August 1947, the night before India’s independence. It is also the night before Pakistan’s creation and the brutal Partition of the two countries. Asha, a Hindu in a newly Muslim land, must flee to safety. She carries with her a secret she has kept even from Firoze, her Muslim lover, but Firoze must remain in Pakistan, and increasing tensions between the two countries mean the couple can never reunite. Fifty years later in New York, Asha’s Indian granddaughter falls in love with a Pakistani, and Asha and Firoze, meeting again at last, are faced with one more – final – choice.

Extract from Where the River Parts

By Radhika Swarup

Published by Sandstone Press

‘I told you,’ Asha said to the retainer. ‘I said I knew Om-ji.’

Om had left her in the hallway of his house, beyond the echoing clamour of the crowd. ‘I’ll get Ma,’ he had nervously said to her. ‘I want her to meet you.’

It was over, her dream, her childhood. She had to forget about Firoze. She had to smile at Om now, and to let her dupatta slip.

‘I’ll just be back,’ he had said, smiling his toothy smile, and she had nodded.

‘Yes,’ she had replied. ‘Yes, take your time.’

‘Well,’ the retainer said uncertainly. He indicated the divan in the hall. He surveyed her unhurriedly, and she grew conscious of how long it had been since she had last bathed. Of how long it had been since she had last seen her mother-of-pearl brush, of how long it had been since she had last eaten. The retainer bowed his head, staring at her mud-splattered slippers, and she found herself muttering about the rain in Punjab. ‘If you say so,’ huffed the man. He indicated the divan again, but as Asha moved towards it, he winced. ‘The upholstery is new. Maybe I’ll fetch you a cloth to sit on.’

So Asha perched on a kitchen cloth in Om’s house. ‘I’m just waiting,’ she said with more confidence than she felt. ‘I’m going to meet Om-ji’s mother.’ Her hand rose as she spoke, and she nearly knocked a priceless vase off its perch. The man rushed forward to protect the precious heirloom. ‘You’re sure,’ he glared at her, ‘you’re sure you’re to wait indoors?’

‘Yes,’ Asha replied meekly, and the man sighed. He picked up the vase, moved it to a table away from her and marched wordlessly off inside the house.

*******

Even where she sat, in the dimly lit hall, she saw signs of careless prosperity. There was the tall screen inlaid with semi-precious stones, there were the twin elephant tusks that guarded the door to the principal rooms. An enormous brass chandelier hung low; an ancient, faded carpet lined one of the walls. And in the distance, the table with its precious vase.

‘Partition,’ Asha observed, ‘has been good to this family.’

She rose, fingered the soft velvet of the carpet, and moved towards the vase. It called to her like the inspector’s contraband and she slowly reached a hand out to touch it. Then she heard a noise, a rustle of a sari, and she hurried back to her seat.

A woman entered. This appeared to be Om’s mother, and the girl rose. She put her hands together and muttered her greetings. The woman nodded. ‘You belong to the Prakash family?’

‘Yes.’

The woman shuffled slowly forward, staring hard. ‘You’re Shiela’s daughter?’

‘Yes,’ said Asha. She saw the woman cast a critical eye over her clothes, and she knew the old sepoy retainer had been describing her. ‘That scamp,’ she thought, but she took care to appear pleasant. ‘I’ve been travelling,’ she explained. ‘I’ve just come in from Pakistan.’

There was no response. ‘My parents,’ began Asha.

‘They didn’t make it,’ said the woman simply.

‘No.’

The woman nodded. She stared at her newly upholstered divan with some concern, and Asha steeled herself to say, ‘Om ji had been given some jewellery by my mother for safekeeping, and so I came…’

‘Oh,’ said the woman with a hard smile. ‘Is that right?’

‘Yes,’ said Asha firmly, but as the woman continued her scrutiny, she felt herself colour.

‘Of course,’ the woman finally said. ‘Of course.’

She shuffled off without another word, and Asha sat miserably down. There was no mention of Om. ‘Horrible woman,’ she fumed. There was to be no marriage, the old witch would make sure of that. She would find the milk-skinned beauty, force her on her son, just as something similar would soon be done in Suhanpur. The almond-eyed Lahori would be brought into the house overlooking the uprooted banyan tree, and another woman’s children would play on her cricket pitch.

Asha set her jaw. Om’s image flashed in her mind, a broad nose over an endless, smiling mouth. ‘No,’ she thought firmly. ‘No, I don’t accept.’

*******

She heard raised voices in the next room. ‘Beta,’ she heard the woman plead. ‘Son, listen to me. You can have your pick now. Why settle for her?’

‘Ma,’ said a soft, patient voice. ‘I like her. I’d even asked for her hand in Suhanpur.’

‘But Beta,’ said his mother. ‘Things were different then. Her father was a respected lawyer. She would have brought a decent dowry. And you hadn’t risen as much as you have over the past few months.’ Om’s mother began cajoling now, ‘How well my son has done. You have blossomed in the midst of all this devastation.’ There was silence for a moment, then she began again. ‘What is she worth now? Nothing.’

Asha’s heart sank. He would let her go.

Om spoke softly, and Asha strained to listen. ‘…have enough…’

‘And she’s nothing to look at.’

‘Ma…’

‘She has nothing, Beta.’

She couldn’t hear his reply, but knew Om’s mother was thinking of the lines of eager girls who waited outside.

‘Her nose isn’t straight …’

‘Bus …’

‘She’s short.’

‘So am I,’ replied an exasperated Om.

‘Chup,’ scolded Ma. ‘You’re my prince.’

His next words escaped Asha. She stood no chance.

‘She has a nice smile, I suppose,’ said Ma reluctantly.

‘I like her,’ said Om plainly, audibly, and Asha’s heart lifted. ‘I like her smile.’

‘Her smile,’ sniffed his mother. ‘Her smile? You could have any girl in Delhi, and you choose a common orphan because of her smile?’ Asha shifted in her seat. The cloth moved under her, and she heard Ma speak again, but she couldn’t stop smiling. She brought her hand up to her mouth and touched the corners of her lips. He liked her smile. ‘Friendship,’ she thought. ‘Kindness, a bit of luck.’

She heard Om rise. A chair was scraped back, she heard footsteps move deeper into the house. She didn’t hear him speak again, but Ma’s voice rose loud in complaint for a long while afterwards. Her drawbacks were listed again, as if Ma was evaluating a vegetable for the evening meal. ‘I wouldn’t mind, Mahesh,’ she said, ‘but she looks so common.’

Mahesh, whom Asha recognised as the retainer, provided a ready echo to all of Ma’s concerns. ‘Yes, Maji,’ she heard. ‘So common,’ but Asha’s hand remained by her smile.

She was in Delhi. She would be safe, and with a bit of luck, she would be happy.

Natalya Filippovna may be a middle-aged, single mother and member of the Russian minority in Estonia, but she is content with her simple life. She has a flat, a job at an electronics factory and, most importantly, she has her bright and ambitious teenaged daughter, Sofia. Money is tight, but they make do – that is, until Sofia requires a lengthy, expensive procedure and Natalya loses her job. With bills piling up, Natalya reluctantly accepts an undesirable mode of income.

‘Mari Saat’s empathic book marks an important turn in Estonian literature to serious moral issues after decades of postmodernist experimentation. The plight of the Estonian Russians can’t be a more topical issue right now in Estonia. But Mari Saat’s treatment is far from unequivocal journalistic cliches. This small lyrical book achieves a subtle synthesis of natural and supernatural, quotidian and quietist.’

– Märt Väljataga

Extract from The Saviour of Lasnamäe

By Mari Saat

Translated by Susan Wilson

Published by Vagabond Voices

Sofia had never come home from school to find Mum, already back from the morning shift or just leaving for the late shift, staring so fixedly at the window, completely oblivious to her. Was she in a world of her own? That had to be it, otherwise she would have done what she always did; she would have come over to give her a hug, or if she were busy with something she would at least have called out and asked a question or explained what she was doing. Sometimes it felt like she was a bit of a nag.

‘Mum, what’s up?’ she asked.

***********

Natalya Filippovna cried. She cried during the day and she cried during the night, even in her sleep. She wasn’t even sure whether she slept at all or just cried. If she were suddenly called back to work now it was more likely than not that she wouldn’t be able to do anything because her eyes were so red and sore from crying, and her head was thumping, and she had a pain in her chest, and her fingers were trembling – there was no way she’d be able to do anything with her fingers in that state. And now there was nothing for them to do anyway.

She had of course heard that things weren’t going so well at the factory. There was talk of a crisis engulfing the global electronics industry, of things not going well with their two main clients, and that there might even be lay-offs. That’s what the gossip was – not that she really paid much attention to it, perhaps because she was, after all, above average. No doubt her age was significant but what did that matter? She was above average for accuracy and speed, had never been off sick and her daughter wasn’t so young that she’d have to stay at home on the odd occasion that Sofia happened to be ill. She was a very good, effective worker. As a result she didn’t immediately understand when they called her in for a chat and said that with regret they could not extend her contract. Later it transpired – as the women had already guessed – that only people whose temporary contracts were coming to an end were being let go. This meant that they would not be laid off – only that their contracts would not be extended any longer. Then it emerged that they were not real workers, unlike workers with permanent contracts who could not simply be discarded in this fashion because they had to be paid redundancy money. Temporary workers could merely be tossed overboard. Natalya Filippovna found it particularly insulting that everyone was treated alike; their speed and accuracy and how much supervision they required counted for nothing. They’d always been happy with her, she’d never missed a shift and now they were suddenly letting her go while the slower, careless workers were kept on just because it cost the factory more to get rid of them… She understood of course that the factory had problems. Even if they actually got rid of the less capable workers on permanent contracts, the factory might not survive, but whatever way she looked at it it felt so unfair. Why bother to monitor and congratulate and praise workers, if it counted for nothing? As she stared at the window, she wanted to hammer her fist against the glass until it bled but instead she merely wrung her hands. It didn’t matter if she broke her fingers, but a broken window would have to be paid for… And how could Sofia live here then, in a kitchen with the wind whistling through… There was no money for new glass… How much would they charge for glazing these days anyhow?

An inspiring look at the remarkable women who fought so tirelessly for equality. Using new material, this study moves away from the ardent activists in London and focuses on the campaign for the vote for women in Scotland. Non-militant ‘suffragist’ groups were found countrywide — from Ayrshire to Orkney — and involved thousands of Scottish women of all ages and from all backgrounds. Unlike their attention-grabbing counterparts the Suffragettes, these women laboured not only for the right to vote, but also for the right to higher education, to separate legal existence from their husbands, and to be actively involved in local government. This is the story of individual Scottish suffragists, resolute and passionate women whose lives have been ‘hidden from history’, but who now receive the recognition they deserve.

Extract from The Scottish Suffragettes

By Leah Leneman

Published by National Museums Scotland

By the end of the nineteenth century the ‘New Woman’ might be satirised, but she existed and had far wider horizons open to her than her mother or aunts. She could be a teacher or a doctor, she could own property or even her own business, in which case she would pay taxes just as a man did – but still she could not vote for her own MP. The Edinburgh society was still going strong, and in 1902 the Glasgow and West of Scotland Association for Women’s Suffrage was formed.

A ‘fine Scottish welcome’ to Mary Phillips

However the tactics they employed, like petitions to parliament, were those which had proved unsuccessful since 1867. What was needed was a whole new approach, and this came from an English widow, Emmeline Pankhurst, and her daughter, Christabel.

Mrs Pankhurst and Christabel formed the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in Manchester in 1903. Initially it was closely linked with the emerging Labour movement. In 1905 the first act of militancy was carried out by Christabel, who interrupted a large Liberal meeting with the shout ‘Votes for Women’, and then spat in the eye of a policeman in order to be arrested and gain publicity. At the beginning of 1906 the United Kingdom had a new government with a large Liberal majority. The existing suffrage societies supported parliamentary candidates of any party who favoured women’s enfranchisement.

Window smashing London Illustrated News

The WSPU initiated a new policy whereby all Liberal candidates, whatever their views on women’s suffrage, were to be opposed until the Prime Minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, formally committed his government to support such a measure. As Scotland was a Liberal stronghold, and by-elections were frequent, it was bound to receive plenty of attention.

Heckling speakers at political meetings was considered a perfectly acceptable thing to do – by men. Heckling by women was unheard of and caused shock, anger … and publicity. Many women, who had never before even considered the matter, suddenly realised how absurd and unjust it was that they could not vote for MPs. To the older suffragists such behaviour seemed undignified and unladylike, and they dissociated themselves from it. However in Autumn 1906, when the WSPU sent Teresa Billington to Scotland to gather members and form branches, she found many ready converts. (In 1907 she married Frederick Greig and settled in Scotland; the couple adopted the name Billington-Greig.) Helen Fraser, a young woman who had never before taken an interest, was swept up into the movement and became the first WSPU organiser for Scotland. The Glasgow and West of Scotland Association refused to have any dealings with the new, militant society, but some of its most stalwart members left to join the WSPU.

Men’s banner in support of women’s suffrage

In 1907 some members of the WSPU broke away to form a new society. They believed in a democratic organisation, whereas Christabel Pankhurst insisted that the WSPU was fighting a ‘war’ that demanded blind loyalty and obedience from its followers.

The breakaway group at first called itself the National Women’s Social and Political Union but later became the Women’s Freedom League (WFL). Its president, Charlotte Despard, was born in Scotland in 1847, and Teresa Billington-Greig was responsible for the work in Scotland. Whether it was because so many Scottish women had been recruited by Teresa in the beginning, or because the Scots were by nature more resistant to autocracy, is unknown, but the WFL always had a very strong base in Scotland. It was smaller than the WSPU and the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), but held a balanced position as a ‘militant’ society that eschewed the later violence of the WSPU.

Phoebe Anna Traquair was a unique figure in British culture. The first significant professional woman artist in modern Scotland, she was also a key figure in the Arts and Crafts movement. A free spirit, Traquair celebrated life through image, colour and texture, taking her inspiration from Renaissance painting, the art and poetry of Blake and the music of Wagner. She produced a huge body of work, from vast, breathtaking mural decorations and sensual embroideries to exquisite illuminated manuscripts and enamels. Using her own words and those of friends and contemporaries, this beautifully illustrated book sheds new light on the ambitions of late Victorian and Edwardian culture.

Extract from Phoebe Anna Traquair: 1852-1936

By Elizabeth Cumming

Published by National Galleries of Scotland

In January 1904 a quartet of remarkable embroideries left the Edinburgh home of their designer and maker Phoebe Anna Traquair (1852–1936) for America, to be shown in the Louisiana Purchase Exposition that summer. Called The Progress of a Soul and created between 1893 and 1902, these two-metre high textiles, in four panels, illustrated the epic journey of the human spirit through life. A narrative sequence inspired by a tale by the aesthete Walter Pater (1839–1894), the embroideries were intended as an expression of personal experience. They drew on a wealth of ideas from literature, music and the visual arts. A century on they still dazzle in their imagination, colour and sheer technical bravura.

The Progress of a Soul

Phoebe Anna Traquair occupies a unique position within British art. On the one hand, she was Scotland’s first significant professional woman artist of the modern age. On the other, she was a valued contributor to the British Arts and Crafts movement. Believing in the indivisibility of the arts, this petite woman worked in fields as various as embroidery, manuscript illumination, bookbinding, enamelwork, furniture decoration, easel painting and, not least, mural decoration. Committed equally to public art and studio crafts, her career spanned four decades from the 1880s. She painted the interiors of no fewer than six public buildings, one of which has walls some twenty metres in height. The stained glass artist Louis Davis, having seen her at work perched high on her scaffolding, referred to her as ‘a woman the size of a fly’. For the poet (and fellow Dubliner) W.B. Yeats (1865–1939), she was ‘a little singing bird’.

This is the story of a confident woman who wanted to make her mark in the art world. In the 1890s and 1900s her studio crafts were exhibited and reviewed, her painted buildings written up in the press and regarded as showplaces to be visited. But her work, so intellectually and emotionally inspired by poetry and music, fell completely out of fashion during the Great War. In the 1980s her craftwork quietly began to resurface in British exhibitions, including The Last Romantics (1989) at London’s Barbican Art Gallery. These, together with the gradual opening of ‘her’ buildings on ‘doors open’ days and, above all, a large exhibition of her work mounted at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery in 1993, put her back on the cultural map. In this, the public has worked collectively with historians, curators and conservators to reclaim her for the art world. As a direct result her buildings are now treasured by their communities and her craft is in demand amongst collectors.

The Red Cross Knight

Seen against the background of her own age, Traquair shines out as a true professional. Driven by a need for creative fulfilment, she networked, negotiated commissions and participated in exhibitions in Britain, Europe and America. Her work may be classified as artistic craft: she was never a modern ‘designer’ but rather always brought an artist’s mind and eye to whichever medium she was currently engaged. However, to call her a ‘decorative artist’ might be to limit her aspirations. Like many other decorative artists she delighted in nature, seeking to ‘match the beauty of red-tipped buds, sunlight through green leaves, the yellow gorse on the hill, the song of wild birds’. The Edinburgh-based Arts and Crafts architect Robert Lorimer (1864–1929), a friend and associate, emphasised her common-sense attitude to life, commenting that she was ‘so sane, such a lover of simplicity, and the things that give real lasting pleasure are the simplest things of nature’. Yet, while often immersed in the minutiae of the natural world, Traquair saw these, like the writer John Ruskin (1819–1900), as part of one vast grand plan. Her ideas, underpinned by Christian faith, were intended above all to reflect the immensity of spiritual life and culture.

In her art Traquair wished to celebrate the potential of the human mind. The poetry and art of William Blake (1757–1827) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) were valued for their exploration of the spirit. In addition, the epic romance was a literary form enjoyed for its rich and traditional narrative of journey and resolution. To realise her work Traquair responded to past arts, uniting ideas in order, perhaps paradoxically, to understand and engage fully with modernity.

Southwall of the Song School, St. Mary’s Cathedral

Traquair’s concerns were with both personal values and universality, and with the role of art within society. Whilst never a follower of fashion, her approach to art was, nonetheless, linked to the enlightened humanism of her age and specifically to Arts and Crafts ideals. The scale of her ideas and her synthesising romanticism were also in line with modern thinking across the creative arts. The Progress of a Soul, in its textures, finely-tuned colours and rich imagery, was intended to assimilate nature, man and God to ‘mirror the whole world’, to use words applied by composer Gustav Mahler to his cosmic third symphony, a work composed in parallel.

With a focus and resolve as keen as those of many of her contemporaries, Traquair may be called a modernist. In particular, in seeking to imagine and illustrate an account of life’s journey, she shared ideals with a range of modern artists, poets and composers. John Duncan’s Celtic murals in Edinburgh’s Ramsay Garden, even Edvard Munch’s great Frieze of Life, and, in music a few years later, Frederick Delius’s A Mass of Life and Ralph Vaughan Williams’s setting of Walt Whitman’s poem Toward the Unknown Region were among works which also explored the range of human experience.

Chapel of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children

The Progress of a Soul, a narrative worked out across four movements or verses, was directly and intuitively inspired by both music and literature. A visual tone poem, it is a heartfelt, mature reflection on ‘life’s rich tapestry’.

This book, also in four parts, sets out to place these embroideries within the context of her life and work. Different chapters look at her early involvement in widening the role of art in society, her development of poetic ideas and creative synergy, and her desire to participate in the shared, professional world of art and craft. Threaded thematically through the book is her principal theme, identified by Yeats as ‘the drama of the soul’. Using her own words and those of friends and contemporaries, this study sheds new light on the ambitions of late Victorian and Edwardian culture.

In 1885 Sir William Fettes Douglas, President of the Royal Scottish Academy, declared that the work of a woman artist was ‘like a man’s only weaker and poorer’. Yet between 1885, when Fra Newbery was appointed Director of Glasgow School of Art and did much in terms of gender equality amongst his staff and students, and 1965, when Anne Redpath, the doyenne of post-Second World War Scottish painting died, an unprecedented number of Scottish women trained and worked as artists. This book focuses on forty-five Scottish female painters and sculptors and explores the conditions that they negotiated as students and practitioners due to their gender.

Extract from Modern Scottish Women: Painters & Sculptors 1885-1965

Edited by Alice Strang

Published by National Galleries of Scotland

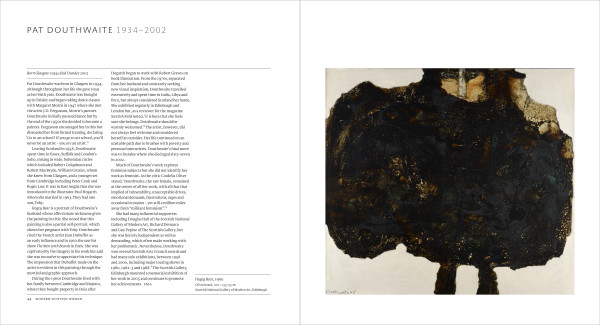

PAT DOUTHWAITE 1934–2002

Born Glasgow 1934; died Dundee 2002

Pat Douthwaite was born in Glasgow in 1934, although throughout her life she gave 1939 as her birth year. Douthwaite was brought up in Paisley and began taking dance classes with Margaret Morris in 1947 where she met the artist J.D. Fergusson, Morris’s partner. Douthwaite initially pursued dance but by the end of the 1950s she decided to become a painter. Fergusson encouraged her in this but dissuaded her from formal training, declaring ‘Go to art school? If you go to art school, you’ll never be an artist – you are an artist.’

Leaving Scotland in 1958, Douthwaite spent time in Essex, Suffolk and London’s Soho, mixing in wide, bohemian circles which included Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde, William Crozier, whom she knew from Glasgow, and a younger set from Cambridge including Peter Cook and Roger Law. It was in East Anglia that she was introduced to the illustrator Paul Hogarth whom she married in 1963. They had one son, Toby.

Hogey Bear is a portrait of Douthwaite’s husband whose affectionate nickname gives the painting its title. She noted that this painting is also a partial self-portrait, which shows her pregnant with Toby. Douthwaite cited the French artist Jean Dubuffet as an early influence and in 1960 she saw his show The Men with Beards in Paris. She was captivated by the imagery in his work but said she was too naïve to appreciate his technique. The impression that Dubuffet made on the artist is evident in this painting through the mottled and graphic approach.

Hogey Bear, 1960 Oil on board, 120 x 133.75 cm Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

During the 1960s Douthwaite lived with her family between Cambridge and Majorca, where they bought property in Deia after Hogarth began to work with Robert Graves on book illustration. From the 1970s, separated from her husband and constantly seeking

new visual inspiration, Douthwaite travelled extensively and spent time in India, Libya and Peru, but always considered Scotland her home. She exhibited regularly in Edinburgh and London but, as a reviewer for the magazine Scottish Field noted, ‘it is here that she feels sure she belongs. Douthwaite should be warmly welcomed.’ The artist, however, did not always feel welcome and considered herself an outsider. Her life continued on an unstable path due to brushes with poverty and personal insecurities. Douthwaite’s final move was to Dundee where she died aged sixty-seven in 2002.

Much of Douthwaite’s work explores feminine subjects but she did not identify her work as feminist. As the critic Cordelia Oliver stated, ‘Douthwaite, the raw female, remained at the centre of all her work, with all that that implied of vulnerability, unacceptable drives, emotional demands, frustrations, rages and occasional ecstasies – yet still a million miles away from “militant feminism”.’

She had many influential supporters including Douglas Hall of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Richard Demarco and Guy Peploe of The Scottish Gallery, but she was fiercely independent as well as demanding, which often made working with her problematic. Nevertheless, Douthwaite won several Scottish Arts Council awards and had many solo exhibitions, between 1958 and 2000, including major touring shows in 1980, 1982–3 and 1988. The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh mounted a memorial exhibition of her work in 2005 and continues to promote her achievements.

Angus Dunn is a poet whose work examines and portrays the natural world with delicacy and careful observation.

‘Angus Dunn’s magical poetry lures us into a world where crows are fruit, the wind is a wire, the moon has a voice and weather holds memory. In effect all these poems are poems of love and each one serves to remind us that precisely because we have been granted everything, we can take nothing for granted’ – John Glenday

Extract from High Country

By Angus Dunn

Published by Sandstone Press

Stealing Away

Out on the moors,

where I had not walked for thirty years,

I found a skeleton

and thought of you.

I took its horns

I took its ears

I brought away the snails

that sat upon its skull.

From the wastes

of sphagnum,

peat and heather

I stole away

with cochleas, seashells

curling ferns

and piggy snouts.

And, though abstractions do not travel well,

I carried off

the logarithmic spirals –

the shapes that form

the galaxies,

tornadoes,

and the precious wenteltrap.

Then, last of all,

(though there were only two)

I plucked the trumpet-lilies

from the fragile bones

and brought them back, for you.

Source

My friend Will tells me

that water has a memory –

the angle of the molecule

holds information.

So he says.

But I remember the light on the river –

river we called it.

The black peat water from the hills

is a dark burn flowing

through many years into the sea.

A drunk man gave us a bottle

and we drank the Sweetheart Stout,

fishing from the undercut bank.

The ancient eels in the black pool

tangled lines and stole hooks.

We’re mostly made of water, Will says.

Which of us, he asks,

has not felt a yearning passion

for a river, for a loch,

for a waterfall. I don’t reply.

Following the burn

on day-long explorations

looking for the source,

we came down from the hill

when the light was gone from the sky.

Years later, not looking for anything,

but resting high on a mountain,

I see a silver trickle running down

the face of the rock,

sinking into the damp black ground.

Our tongues taste shapes and angles,

Will says.

And when we drink

we taste the memories of the water.

I lick the wet rock. It just might be true.

The Glasgow poet Marion Bernstein (1846–1906) recognised little distinction between gender equality and social equality. She valued her fellow poets, many of whom were from the working classes, and she populated her poems with an array of ordinary citizens: postmen, riveters, fishermen, street musicians, even a victim of intemperance.

A Song of Glasgow Town contains all of Bernstein’s 198 published poems, along with a detailed introduction to her life and work.

Extract from A Song of Glasgow Town

By Marion Bernstein

Published by ASLS

A Song of Glasgow Town

I’ll sing a song of Glasgow town,

That stands on either side

The river that was once so fair,

The much insulted Clyde.

That stream, once pure, but now so foul,

Was never made to be

A sewer, just to bear away

The refuse to the sea.

Oh, when will Glasgow’s factories

Cease to pollute its tide,

And let the Glasgow people see

The beauty of the Clyde!

I’ll sing a song of Glasgow town:

On every side I see

A crowd of giant chimney stalks

As grim as grim can be.

There’s always smoke from some of them—

Some black, some brown, some grey.

Yet genius has invented means

To burn the smoke away.

Oh, when will Glasgow factories

Cease to pollute the air;

To spread dull clouds o’er sunny skies

That should be bright and fair!

I’ll sing a song of Glasgow town,

Where wealth and want abound;

Where the high seat of learning dwells

’Mid ignorance profound.

Oh, when will Glasgow make a rule

To do just what she ought—

Let starving bairns in every school

Be fed as well as taught!

And when will Glasgow city be

Fair Caledonia’s pride,

And boast her clear unclouded skies,

And crystal-flowing Clyde?

Human Rights

Man holds so exquisitively tight

To everything he deems his right;

If woman wants a share, to fight

She has, and strive with all her might.

But we are nothing like so jealous

As any of you surly fellows;

Give us our rights and we’ll not care

To cheat our brothers of their share.

Above such selfish, man-like fright,

We’d give fair play, let come what might,

To he or she folk, black or white,

And haste the reign of Human Right.

After the success of his first novel, the much-lauded A Book of Death & Fish, Ian Stephen returns to poetry and his passion for all things marine with a collection that evokes the dramatic waterscapes, rocky shores and wind-blasted textures of his native Hebrides.

‘Absorbing and riveting… dense, compelling and wildly idiosyncratic… splits the form open like a fresh catch, glistening and raw and singing with the sea’

– Kirsty Gunn, Guardian

Extract from Maritime

By Ian Stephen

Published by Saraband Books

At Plockton

In the ebb of pleasure here,

embedded in pebbles,