This is a book of poems from the edge. They belong to particular places: a village by the side of a single-track road in the West of Scotland; the Separation Barrier between the West Bank and Israel; the crowded, lonely streets of London, during a protest about world poverty; the huge empty shores of the Isle of Mull. With down-to-earth detail, they celebrate the beauty, uniqueness, mystery of this world which we share and the courage of people who, confronted by injustice, hold on to their humanity.

Extract from Between High and Low Water

By Jan Sutch Pickard

Published by Wild Goose Publications

Abbey library

(October 2002)

The shelves are eating the books –

said the librarian,

who is trained in these things.

Static shelving, grained and gracious oak

seeming set for all time,

is in fact in flux:

dead vegetable matter, breaking down,

releasing gases, to make the old books

more brittle still, till they crumble

like leaves on the forest floor.

They would be far safer –

she said –

in steel stacks.

Meanwhile, I stand

as though in an enchanted wood,

breathing the books’ autumnal fragrance:

having proof now

that, through all its perils,

this library is alive.

Packing up the library

To lose one library

is a misfortune; to lose two

looks like carelessness.

So, before the Abbey is rewired,

the books are on the move –

going into the ark two by two:

into the archive boxes.

Lying down meekly –

the lion with the lamb,

polemic with peace studies,

poetry with politics,

Celtic studies with eschatology;

gathered in from the open shelves

where saint and sinner

were free to browse.

Now safe and unread under hatches

while the rain falls on a wordless world

till the dove sounds the all-clear.

Collection of poetry on the themes of motherhood, empowerment, love and loss by acclaimed poet Bashabi Fraser. Drawing on her Indian and British life experience, Fraser engages with hard-hitting current issues such as climate change, war and the prevalence of violence against women in India.

Extract from Letters to My Mother and other mothers

By Bashabi Fraser

Published by Luath Press

I saw you last night

I saw you as you were, last night

I had brought a friend home

I hadn’t warned you

You opened the door

Your face was soft as it always was

Suffused by the magic of twilight

The open door let in.

I said, Ma, this is my colleague

You smiled, your eyes a melting caress

You stepped back to let us in

Your dining table was laid, expectant

Behind you. You walked effortlessly

To the kitchen to bring in an extra plate

Your quiet acceptance flowed

From your inherent generosity

Before unannounced strokes

Froze sections of your once discerning brain

And you altered to the unquestioning presence

That wasn’t and yet was you,

But I saw you last night

Not as you had become in the post-twilight years

But as you always were

And will be for me, my mother.

Darkling I listen

It was in the stillness of midnight when the goslings

Had retired with mothers from their springtime dance

That my friend called me to step outside

While villages slept in the south of France.

Under the stars that lit a magnificent chapel

I could hear the deafening chorus of frogs, delirious

With song, who, my friend said, were tiny denizens

Of the world with voices ambitiously searching the stars.

But these were not the vocalists

She wished me to hear. She told me to walk round

To the other side of her home, and there I heard

A heavenly choir that drowned the sound

Of the throaty clamour that had surprised me earlier.

‘Listen to the nightingales’ my friend urged

And I did, hearing the trilling and twitter,

The chirping and whistling, the harmony that surged

Through the branches above me. I was bewildered.

I asked, ‘but which one is the nightingale?’

I could hear the smile in her voice as she said

‘Only nightingales sing at night.’ And in the pale

Starlight, a line I had carried with me

All my life was suddenly suffused with illumination.

Of course, Keats could not have heard the bird

Singing in full-throated ease seeking its twilight destination.

He heard it in the stillness of the night

And I heard a full choir Ma, with a whole language

Of harmony, calling and answering

Improvising in ecstasy with freedom and courage

That comes with the knowledge of dominance

And excellence as all other songsters slumber.

So Ma, I heard the nightingales singing

Their full repertoire just as Keats had done one summer.

Gerry Loose’s sixth collection maps the fault line dividing man from his environment. His territory is the Gare Loch in Argyll and Bute, its outstanding beauty at odds with the Faslane submarine base on its eastern shore, home of the UK’s nuclear arsenal. The beauty of the area coexists uneasily with the knowledge that it also harbours weapons that can reduce their target to radioactive ash. This tension has inspired a book-length poem that probes the delusions of the political and military classes, as well as the beauty and fragility of the landscape.

Extract from Fault Line

By Gerry Loose

Published by Vagabond Voices

I

about right for these parts

mostly birch

some oak

my living room

where the white hind has

scented me

though I’m glassed in

standard class

on the halted train

through Glen Douglas

she follows my gaze

over her shoulder

to hillside bunkers

trots downwind

in the direction of

the sea’s drifting

foam specks

~

while an owl

edits my sleep

an object

II

consider these lilies

what you talk about

when you talk aesthetics

& these sweet coils

woodbine razorwire

~

my fixed point of the hills

grasping peerless sunlight

III

states of matter

halogen lights

safely do away

with night & day

abolish the moon

barn owl

snatches song

all twenty four hours now

a siren

rock to my hard place

these men talk

to their lapels

~

meniscus

mergansers dive

see

the bridge

see the water

see the bow wave

turning

IV

the streets are lined

today I found a penny

yesterday a pound coin

it’s on my shopping list

tea wine gold

that everyday hero

Midas

warned me

~

inadvertently

making the sign

of the cross

on that train

no other

he offers me wine

V

more than one sun

in the sky now

the heron’s auguries

no longer to be trusted

she too stands

on the street corner

hand to mouth

hand to ear

I still worry

about the apple trees

~

dawn

here if

it’s rosy fingered

it’s brambles

or blood

‘An imaginative and innovative poet in Gaelic and English with the sensibility of a native speaker and an astute reader of poetry. This is an intelligent, measured and powerfully resonant collection.’ – Rody Gorman

Extract from Gu Leòr (Galore)

By Pàdraig MacAoidh

Published by Acair Books

Bàta Taigh Bàta

Rinn i seòmar-cèilidh

à sparran tràlair a h-athair:

sin neo am fàgail nam malcadh

an àiteigin air cladach cèin.

Nan cuireadh tu do bhas air an darach

bha e eadar sàl agus gainmheach;

nan gnogadh tu air,

dhèanadh e scut.

Chrom sailthean an tobhta-bhràghad

ris a’ mhuir, dà mhile air falbh;

Gach oidhche ghluais an taigh

ann am bòchain, a’ tarraing air acair.

Dh’fhuaimneadh mic-talla tron fhiodh

mar ghlaoidhean uilebheistean-mara,

dh’fhàs polaip agus grom fo sgeilp an TBh,

Rinn an uinneag dùrdan drabasta,

fhuair a’ ghaoth an similear mun amhaich

a’ feuchain ri tharraing o mharachadh.

Fon bhòrd-chofaidh bha stòbhan-air-bòrd

a’ cagar gu gnù, ann an ceannairc.

Chumadh cas-cheum seann mharaiche a’ chamhanaich,

thairngreadh ròpanan an latha. Ri tìde

fuasglaidh i na snaidhmean, ga giùlan tron t-sìl.

Thèid a bristeadh air an t-slighe.

Boat House Boat

(English Translation)

She made her living room

from the spars of her father’s trawler;

it was either that or leave it to rot

on some distant shore.

If you smoothed your palm on the oak

it was between sand and salt:

if you chapped it,

It gave out a scut.

The beams of the bow curved out

towards the sea, two miles away.

Each night the walls would catch

in the tide and pull on anchor,

echoes would sound through the wood,

like the calls of sea-monsters.

Polyps and coral started to form under the TV shelf,

The bay-window murmured bawdily,

the wind caught the chimney by the scruff

and tried to lift it from its moorings,

under the coffee table stowaways gathered

whispering in sullen mutiny.

A sailor’s boot taps keep the small hours;

the pulling of ropes fills the day.

over time, she will work open the knots,

force herself to the sea. Be broken on the way.

Gutter Magazine is the outstanding independent literary magazine from Freight Books, publishing fiction and poetry from writers born and living in Scotland. The work you’ll find here is in turns diverse, delicate and dangerous. Issue 14 will focus on poetry, and will be released in March, alongside a digital soundtrack. We have a sneak preview of two included poems, from renowned poet and musician, Aidan Moffat.

Extract from Gutter Magazine (Issue 14) Soundtrack

Poems by Aidan Moffat

Published by Freight Books

On November 27, 1786 Robert Burns, on a borrowed pony, set off on the two-day journey to Edinburgh. He would stay 14 months.

It was at the peak of the Scottish Enlightenment. Edinburgh at the time was home to great philosophers, world-renowned economists, engineers, scientists, writers and poets. Enterprise and industry were flourishing. Robert Burns was to find himself thrust into the midst of that social and academic whirlpool, establishing him as a vital part of the Scottish Enlightenment.

This book chronicles the places he visited and the brilliant, eccentric, but always fascinating people he met during his stay in Edinburgh. Places include Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2, The Kirk of the Canongate, Old Calton Burial Ground, St. Cecilia’s Hall, Pear Tree House, The Luckenbooths and many more.

Extract from Robert Burns in Edinburgh

By Jerry Brannigan and John McShane

Published by Waverley Books

Robert Burns was born on 25th January 1759 in Alloway, two miles from the town of Ayr in the west of Scotland. He was born in the family home, a small clay and thatched-roof cottage built by his father, William Burnes.

William Burnes’ early years are a little vague. His father Robert, the poet’s grandfather, rented Clochnahill Farm on the Dunnottar estate of George Keith, 10th Earl Marischal. The role of the Marischal was to serve as custodian of the Royal Regalia of Scotland and to protect the king when he attended parliament. A Jacobite sympathiser, Keith was charged with treason for his part in the 1715 and 1719 risings forcing him to flee to the Continent where he continued to serve the Jacobite cause. His lands were confiscated by the Crown in 1720. Robert continued to work the farm but bad weather, low prices and the economic aftermath of the ’45 rising forced him to give up the lease.

Many families were forced out of the Highlands and into the Lowlands in search of work and William Burnes eventually found himself in Edinburgh working on the newly formed Hope Park, now known as the Meadows, on the south side of the City. He worked there for two years as a landscape gardener before moving to the west coast of the country, to Fairlie in Ayrshire, where he had the offer of a job.

William settled in Alloway and married Agnes Broun (Scots spelling of Brown) on 15th December 1757. Robert was born on 25th January 1759 and Gilbert in 1760. There followed another two boys and three girls.

William, a very independently minded man, was deeply religious and believed that in order to make progress in the world his children should be able to read and write and have at least a basic education, so Robert (at age 6) and Gilbert (at age 5) were enrolled in Alloway School. When the school was forced to close due to financial pressures, William persuaded neighbours to hire John Murdoch from Ayr to teach the children.

Murdoch was 18 years old and had been educated in Edinburgh. Murdoch gave the boys the foundation of a classical education, teaching them the Bible, and exposing them to the works of Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden and the finest writers of the day.

When Murdoch left to take up another paying post in Dumfries, William continued to teach the boys himself and enrolled them in Dalrymple School, which they had to attend week about, because both could not be spared from farm work at the same time.

In 1773 John Murdoch returned to Ayr and Robert spent three weeks with him, studying English, French and Latin.

Robert was an avid reader from this time, and for the rest of his life. As a family they could be found in the evenings reading to their father, or each other. Robert, in one of his letters, remarked that he was inspired by the tales of Hannibal and of Sir William Wallace, “who poured a Scottish prejudice into my veins which has boiled there in each and every one of my waking moments.”, so much so that as a boy he would imagine he was Wallace and marched alongside soldiers as they passed through the town.

In his later years Robert would have books delivered from France, regularly reading the original French versions. A partly read book, in French, was on his bedside table on the day he died.

Robert started writing verse when he was 15 years old. The reason? He had fallen in love with Nelly Kilpatrick. For the rest of his short life he was to fall in love regularly, expressing his thoughts and emotions in poems and songs.

Robert’s early life was hard – very hard. It was a constant struggle to farm on poor soil and despite moving from farm to farm there was never any money to invest in more modern farming equipment resulting in the family continuing to live in near poverty. Despite this, Robert worked long hours and developed a slight stoop due to the time spent on the plough.

It was these long hours, and a poor diet from a very young age, which did lasting damage to Burns’ health. Damage that meant that, despite his reputation, he would never be a heavy drinker as alcohol upset his already delicate stomach.

On the 4th July 1782, when he was 22 years old, Robert joined the Freemasons. This membership not only cemented friendships and relationships with people he already knew in his local area, but was an invaluable source of contact and introduction when he found himself in Edinburgh.

On 13th February 1784 his father William died at the age of 63. Robert was 25 years old and now found himself the head of a large family. His father had been fighting a legal battle over the farm and after several years he won the court case, but the years of toil and hardship had taken its toll on William. Robert simply had to work harder to keep the farm going since he was now the provider for his siblings and his mother.

It was around this time that the family name was changed from Burnes to Burns. There may have been a variety of reasons for this, one of them being that Burnes was a Kincardineshire name and Robert and Gilbert may have decided to change it to the Ayrshire form. It may also have been an attempt to avoid some of the people who had been pursuing them for money.

On 22nd May 1785, Elizabeth Paton (his mother’s servant) gave birth to Robert’s first child, also Elizabeth. Robert’s mother took the child in and raised her as one of her own.

Jean Armour, whom he had first met at a dance in April of 1785, became pregnant. They did intend to marry but Jean’s father, knowing of Robert’s reputation, wanted his daughter to have nothing to do with him, sending Jean off to Paisley.

Robert had reached a turning point in his life. The farm was not going well, the Kirk was pursuing him as a fornicator and Robert felt that the world was conspiring against him.

Through his various contacts he was offered a job as a Plantation Manager in the West Indies, and decided to go to Jamaica. It was a drastic step but how could he raise the money for the trip?

Some friends suggested that he publish some of his work to raise the money. Burns was well known in the area as a ‘maker of rhymes’ (in Scots the word for poet is ‘makar’) regularly writing out copies of his poems and giving them to friends and acquaintances; a practice he maintained all of his life, regularly enclosing new poems and songs along with letters to friends. It was common in those days for books to be published by subscription, so Burns began planning his book.

The only printing press in Ayrshire was located nearby in Kilmarnock. Its owner, John Wilson, an exact contemporary of Robert Burns, had already published an edition of Burns’ beloved poet Milton in 1785. In April 1786 the subscription sheets were printed by Wilson, and Robert’s fund-raising was complete when 13 fellow members of the Masonic Lodge pledged to take 350 of the 650 volumes to be printed.

The only printing press in Ayrshire was located nearby in Kilmarnock. Its owner, John Wilson, an exact contemporary of Robert Burns, had already published an edition of Burns’ beloved poet Milton in 1785. In April 1786 the subscription sheets were printed by Wilson, and Robert’s fund-raising was complete when 13 fellow members of the Masonic Lodge pledged to take 350 of the 650 volumes to be printed.

His fare to Jamaica was 9 guineas and publication of the book would surely raise that amount, but in the meantime Robert’s troubles were building as he was making plans. On 23rd April, James Armour repudiated Robert as a son-in-law and Robert was also forced to repudiate Jean. On 13th June, Jean went before the Kirk and advised them that she was with child and Robert was the father. This started a furore against Robert yet again in the Kirk and he was ordered to make 3 public appearances as a fornicator, the first of which was on 25th June.

On 22nd July, Robert had a Deed of Assignment drawn up and lodged with the Sheriff-Clerk at Ayr. This basically transferred all of Robert’s assets to Gilbert, his share of the farm, all profits from the book and it also made Gilbert responsible for the upbringing of Robert’s illegitimate daughter, Elizabeth.

However, on 30th July, James Armour took a writ out against Robert and, terrified of being arrested and thrown into prison, he went into hiding at his uncle’s home near Kilmarnock.

As providence would have it, on the following day, 31st July 1786, his book, Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, went on sale and was an immediate success, selling over 600 copies and earning Robert more than enough for his trip to Jamaica.

Robert Burns was suddenly a successful writer who was being spoken of the length and breadth of Scotland.

Even when Jean gave birth to twins, Robert and Jean, (the Kirk stated that children born out of wedlock be named after the parents) on 3rd September, he still planned to go to Jamaica, but all that was to change with one message from Edinburgh.

A copy of the book had made its way into the hands of Dr Thomas Blacklock, known as The Blind Poet. Blacklock’s poetry was much respected and he was acquainted with such famous figures as Dr Samuel Johnson and his biographer James Boswell, as well as the philosopher David Hume and one of the most famous Americans, Benjamin Franklin.

Indeed Blacklock was so full of praise for Burns’ work that he advised him to come to Edinburgh immediately where a second, larger, edition could be published. He was sure it would have a more universal circulation than “anything else that had been published within his memory”.

Burns had naturally been thinking of a second edition as the first had sold out so quickly, and being a prolific writer, he already had new material. John Ballantyne, an Ayrshire banker, offered to lend him money for the second edition; he also advised Burns to look for a publisher in Edinburgh.

So it was that on 27th November 1786 Robert Burns, on a pony borrowed from his friend George Reid, set off on the two-day trip to Edinburgh.

Reid had arranged for Burns to break his trip at Covington Mains Farm, by Biggar, and rest overnight before travelling on. Reid had also arranged for the farmers of the area to call and meet their new hero in person. The signal of Burns’ arrival was a white sheet tied to a pitchfork placed on a cornstack and on Burns’ arrival the house was soon filled. The evening became part of the morning and, after his farewells, Burns breakfasted at the next farm with another large party.

Following lunch at the Bank in Carnwath and, after saying his goodbyes to the assembled well wishers, he rode on to Edinburgh in the evening.

Songs, poems and artist interviews in this behind-the-scenes story of the making of the Robert Burns Night app‘s exclusive audio recordings, from Saraband Books. Featuring Karine Polwart, Aly Macrae, Annie Grace, Corrina Hewat, Kirsty Grace and Drew Harris.

(Design: Scott Smyth / app developed with Spot Specific — special thanks to Graeme West / studio production Stephanie Harris and Stephen Paul)

Kirsty Grace sings the traditional melody of Auld Lang Syne, including several of the less familiar verses. Kirsty sang at the State Opening of the Scottish Parliament in 2011. (Originally recorded for the Robert Burns Night app from Saraband Books, available on iTunes.)

National Theatre Scotland actor Aly Macrae reads the opening section of one of Robert Burns’ best-loved poems, ‘Tam O’Shanter’. It is traditionally read at Burns Suppers each year to celebrate the bard’s birthday, January 25th. (Originally recorded for the Robert Burns Night app from Saraband Books, available on iTunes.)

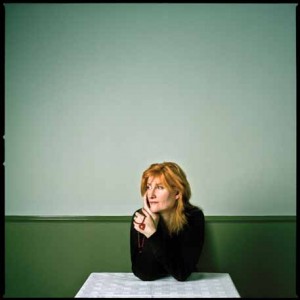

As Others See Us is based on a photographic exhibition from Tricia Malley and Ross Gillespie, who together form the renowned partnership broad daylight. The exhibition was part of the celebrations for the 250th anniversary of Robert Burns’ birth. The portraits capture a unique insight into the sitter, enhanced by the accompanying text, as each was asked to contribute their favourite poem from Robert Burns, and to explain why it is special to them and what they think it means to Scots today.

Extract from As Others See Us

Contribution from Eddi Reader

Published by Luath Press

Lovely Polly Stewart

The flower it blaws, it fades, it fa’s,

And art can ne’er renew it;

But Worth and Truth eternal youth

Will gie to Polly Stewart.

May he whase arms shall fauld thy charms,

Possess a leal and true heart!

To him be given, to ken the Heaven

He holds in Polly Stewart!

While making an album of Robert Burns’ music and words, I travelled millions of miles in his company. I searched gravestones for his friends and his companions; I stood in the rain outside doorways he had stood in; I drank in bars he had drunk in; I marvelled at the beauty he saw from the hills of Galloway and the Heads of Ayr and I am convinced that I was directed by him in my choices for the album. The book of his work that I was collecting from continually opened, Harry Potter-like, at the page that contained the words of the poem ‘Willie Stewart’ until the day it magically fell open at a poem called ‘Polly Stewart’. Polly was Willie’s daughter and I decided to insert it into my version of Willie Stewart. After getting loads of praise for my album, I went back to Dumfries to visit Burns’ last home and found the lines to half the verses engraved on a back window in a hidden room. I felt his company once more.

Thank you, Robert. I love you x

As Others See Us is based on a photographic exhibition from Tricia Malley and Ross Gillespie, who together form the renowned partnership broad daylight. The exhibition was part of the celebrations for the 250th anniversary of Robert Burns’ birth. The portraits capture a unique insight into the sitter, enhanced by the accompanying text, as each was asked to contribute their favourite poem from Robert Burns, and to explain why it is special to them and what they think it means to Scots today.

Extract from As Others See Us

Contribution from Edwin Morgan

Published by Luath Press

The Address of Beelzebub (The Devil) to;

The Rt. Hon. John, Earl of Breadalbane;

1786 A.D (5790 A.M)

Go on, my Lord! I lang to meet you

An’ in my house at hame to greet you:

Wi’ common lords ye shanna mingle

The benmost newk, beside the ingle

At my right hand, assign’d your seat

’Tween herod’s hip and polycrate

A seat, I’m sure ye’re weel deservin’t;

An’ till ye come – your humble servant,

BEELZEBUB

Hell, 1st June, Anno Mundi 5790.

This poem offers a very interesting, unusual slant on the Highland Clearances, as it deals with early attempts to prevent the Highlanders from emigrating to the New World. It made a strong impression on me as a poem, but it is particularly interesting that someone renowned as a lyric poet should also write such a powerful satirical work. It almost needs a key and notes to get the full meaning from it. Some commentators did not like this contrast with Burns’s lyricism, but it is all to the good that a poet can write both satirical and love poetry.

Burns is the great example of a thinking man, gradually learning how many things he could do well, looking round the society of his own time and responding to it in his poetry. Here he mentions both his contemporaries, such as George Washington, and historical figures from the past that match the unscrupulous landowners of his day, and who are promised a similar reward in hell. This range of reference is all to the good. At the time, it was unusual to possess such a poetic range, but in Shakespeare’s and Milton’s time it was accepted that a poet should cast his mind widely. Burns had a sharp eye, a sharp ear, a sharp tongue – and enjoyed riling his contemporaries. It was excellent that he was able to do this as skillfully and energetically as he does here.

As Others See Us is based on a photographic exhibition from Tricia Malley and Ross Gillespie, who together form the renowned partnership broad daylight. The exhibition was part of the celebrations for the 250th anniversary of Robert Burns’ birth. The portraits capture a unique insight into the sitter, enhanced by the accompanying text, as each was asked to contribute their favourite poem from Robert Burns, and to explain why it is special to them and what they think it means to Scots today.

Extract from As Others See Us

Contribution from Janice Galloway

Published by Luath Press

Ca’ the yowes to the knowes

Ca’ the yowes to the knowes

Ca’ them whare the heather grows

Ca’ them whare the burnie rowes,

My bonnie Dearie.

As I gaed down the water-side,

There I met my Shepherd-lad:

He row’d me sweetly in his plaid,

And he ca’d me his Dearie.

I’m from Ayrshire, so Burns has always loomed large – school competitions and the like did not put me off. I sang ‘Ca’ the Yowes’ at Burns suppers as a teenager, sometimes as the only woman present, and loved the eerie quiet of the words before I really knew what it meant. Songs to country girls are a stock in trade in folk song circles, but Burns’ are special. That she is ‘fair and lovely’ is an unlikely thing, given the arduousness of minding yowes – out in all weathers from the age of ten, sleeping on the hillside, zero to meagre pay – but Burns imagines her as heroic, calling the sheep to the swollen waters of the burn in the evening to keep them safe, being his ‘Bonnie Dearie’. And the melody, an almost modal minor tune, is completely haunting.

Sing it yourself, unaccompanied – it’s the only way.

A Boy Called Christmas is a tale of adventure, snow, kidnapping, elves, more snow, and a boy called Nikolas, who isn’t afraid to believe in magic.

Extract from A Boy Called Christmas

By Matt Haig, Illustrated by Chris Mould

Published by Canongate Books

You are about to read the true story of Father Christmas.

Yes. Father Christmas.

You may wonder how I know the true story of Father Christmas, and I will tell you that you shouldn’t really question such things. Not right at the start of a book. It’s rude, for one thing. All you need to understand is that I do know the story of Father Christmas, or else why would I be writing it?

Maybe you don’t call him Father Christmas.

Maybe you call him something else.

Santa or Saint Nick or Santa Claus or Sinterklaas or Kris Kringle or Pelznickel or Papa Noël or Strange Man With A Big Belly Who Talks To Reindeer And Gives Me Presents. Or maybe you have a name you’ve come up with yourself, just for fun. If you were an elf, though, you would always call him Father Christmas. It was the pixies who started calling him Santa Claus, and spread the word, just to confuse things, in their mischievous way.

But whatever you happen to call him, you know about him, and that’s the main thing.

Can you believe there was a time when no one knew about him? A time when he was just an ordinary boy called Nikolas, living in the middle of nowhere, or the middle of Finland, doing nothing with magic except believing in it? A boy who knew very little about the world except the taste of mushroom soup, the feel of a cold north wind, and the stories he was told. And who only had a doll made out of a turnip to play with.

But life was going to change for Nikolas, in ways he could never have imagined. Things were going to happen to him.

Good things.

Bad things.

Impossible things.

But if you are one of those people who believe that some things are impossible, you should put this book down right away. It is most certainly not for you.

Because this book is full of impossible things.

Kirsty Logan talks to BFS editor Lindsay Terrell about myths, fairytales and her debut novel The Gracekeepers

(published by Harvill Secker, an imprint of Vintage Books).

Bright night, May light, milk moon. They ran. Their paws were damp with blood…Inside her, I was so close to being happy. So close to being outside her…Already my fingers were separate, the buds of my incisors formed, the fists of my lungs getting ready to open….But in the end, we can only be one person. (From A Portable Shelter by Kirsty Logan)

‘Liminality’ is the word that comes to mind as I settle into a conversation with Kirsty Logan, one of the newest, most original voices on Scotland’s literary scene and winner of this year’s Polari Prize. Her work inhabits a landscape of both mythology and mundanity, is situated between land and sea and is populated by selkies, werewolves, witches and other beings in a state of flux.

‘I’m fascinated by boundaries and places of change,’ she tells me.

With two short story collections and now a widely acclaimed debut novel, The Gracekeepers, under her belt, Logan has already drawn comparisons to such genre-defining heavyweights as Angela Carter. But if Carter was interested in dismantling the tropes of the fairytale, Logan exploits them for their internal logic and inherent dualities to create a uniquely 21st century mythology, encompassing sexuality, gender identity, loss, love and landscape.

Her stories are a combination of tradition and invention. ‘I don’t want the reader to feel the ground they’re on is too steady’, Logan says. ‘I want them to think, I know what kind of story this is, and then to play with that. I like that about fairytales. You get settled in the story and all of a sudden a golden dart comes down.’

Perhaps Logan’s most notable golden dart is her Gracekeeper, Callanish, a marginalised character with a conflicted identity, tasked with carrying out the death rituals of her society. That society is itself located on the margins, in a watery world where land is disappearing beneath the rising sea. Land equates with power, and the sea-dwellers in this new world order are relegated as second-class citizens. It is to one of these sea-dwellers – a circus performer named North – that Callanish is drawn, and they must overcome the tides of prejudice, stigma and fear, which, even as they throw the two together, would keep them apart.

This world feels at once a plausible dystopia and also the stuff of lands far, far away. And that’s exactly the kind of world that attracts Logan. She recalls a childhood of Scottish holidays, where visits to the sea, walks through the forests and day trips to castles blended with bedtime stories of princesses and enchanted castles. ‘Those worlds felt magical and distant, but also real: here and tangible,’ she says.

Whilst she admires the purely fantastical worlds of, say, Lord of the Rings, it’s the prosaic she finds truly enchanting. ‘The real stakes – the real emotional stakes – are mundane, but much more powerful.’

She points to some of the classic fairytales like Hansel and Gretel, or Rumpelstiltskin. ‘On the one hand you might have a dress made of gold or hair made of the moon, but on the other you have questions like, I don’t have enough food, or my parents can’t support me, or my mum has promised I can do this thing, and I can’t do it. It might not end the whole world, but your world will end. That’s where the real horror and beauty of the world lies, in the mundane.’

One encounters similar problems in her stories: How can I build a future with insufficient resources? Will my mother accept me even if I’m not like her? It’s just that, in Logan’s stories, sometimes that difference lies somewhere between woman and seal, or baby and wolf.

Which takes me back to her selkies and werewolves. When I ask her about this, about the otherness lying just beneath the skin, she says she’s conscious of the pressure to ‘choose one way to be, conscious that you can be two things at once.’ She points to her own sexuality, her upbringing between England and Scotland, the way the tide blurs the boundaries between water and earth. She’s drawn to ‘places and people who reverse those boundaries.’

In fact, her stories do tend to borrow from life.

The impetus behind The Gracekeepers came with the loss of Logan’s father. Still grieving that loss and searching for ‘a structure for mourning’, she was on a boat one day when she saw life buoys with lights sitting in cages on the water. They reminded her of bird cages, and so the character of Callanish was born. Even as she was creating a character who offers ritual sea burials of birds (‘graces’) to mark the passing of human beings, the act of writing came to mirror that ritual, becoming ‘a secular mourning system.’

She says it’s sometimes easier to communicate complex emotions by ‘making them into something concrete, something you can explore. If you want to say, This person is gone, and I’m not ready for them to be gone, sometimes you write a person who’s in so much darkness that he eats lightbulbs. Magical things function as a way to explore emotion.’

I ask if, in a story which touches on so many points of cultural relevance, she also meant to create a narrative around climate change? The answer is no, but Logan points again to the enduring quality of the fairytale. ‘The current political climate influences the way people read the stories. All you can hope when you write a story is that, if it has meaning for you, it will have meaning for other people.’ She’s not interested in prescribing what that meaning must be.

‘It’s so important that people feel an ownership over stories and over the way we tell them. These stories are ours. We can do anything we want to them. They belong to us.’

And so she returns to the tales that ‘speak to our fears and our hopes and our desires’, because ‘there’s a selkie in all of us, a vampire in all of us.’ And if it’s truly in the in-between places that we all exist, I, for one, am happy to have Logan taking us there.

An innovative, rich survey of images of European witchcraft, from the sixteenth century to the present day. It focuses on the representation of women and the enduring stereotypes they embody, ranging from hideous old crones to beautiful young seductresses. Such imagery has ancient precedents and has been repeatedly re-invented by artists over the centuries.

Extract from Witches and Wicked Bodies

By Deanna Petherbridge

Published by the National Galleries of Scotland

Witches carrying out evil deeds (maleficia) have traditionally been depicted in Western art, culture and religion as female figures. Such personifications range from the vicious bird-women harpies of Greek and Roman mythology, who tear at the tender bodies of infants in their cradles, to the Old Testament Witch of Endor, raising ghosts through incantations for purposes of prophecy. Winged harpies and sirens are pictured on vases or ancient sculptural reliefs, just as the beautiful sorceresses Circe and Medea are woven into the narratives of Hesiod, Homer and Ovid. These Greek and Latin epic poems have inspired artists, poets, playwrights and composers of opera throughout Europe for many centuries. In British culture they joined a rich seam of imagery derived from the Arthurian legends, Shakespeare, the Satanic figures of Milton and poetic translations from Goethe. The imagery of sorceresses readily crosses the boundaries of visual art forms but the links between visual representations of witches and literary, poetic and theatrical sources are particularly potent, as revealed in this exhibition.

- William Blake (1757–1827) The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy (formerly known as ‘The Triple Hecate’), c.1795 Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh © National Galleries of Scotland

- Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) The Four Witches, 1497 Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh © National Galleries of Scotland

- Paul Sandby (1731–1809) The Flying Machine from Edinburgh in One Day Performed by Moggy Mackenzie at the Thistle and Crown, 1762 Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh © National Galleries of Scotland

- Agostino Veneziano (Agostino de’ Musi) (c.1490–c.1540) The Witches’ Rout (The Carcass), c.1520 Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh © National Galleries of Scotland

From Adventure

‘White Christmas’

By Mark Greene

Published by Muddy Pearl

Some dreams may come true:

Chestnuts roasting on an open fire,

The soothing cool of Mediterranean blue,

The rustling shimmer of wedding white.

The old seer’s dream,

His eye scoured of fanciful self-delusion,

Saw this:

A cedar hacked to a stump,

Springing to a new shoot;

The village virgin’s impossible boy

Crowned universal king;

The innocent prince pinned

Against the protesting sky

By the dark insistent lie

Of his adulterous bride.

This dream,

Sure in its renewed proposal,

The eternal breeze whispering our name,

The desert heart fountaining with joy,

This dream,

Real in her expectant womb,

Real in the blooded planks of that severed tree

And the blast-bright fullness of his empty tomb,

This dream

Came true.

‘Tam Linn’ (or ‘Tam Lin’ or ‘Tamlane’) is one of Scotland’s most distinctive fairy tales. It may be best known as a Border ballad, but it has also been retold in many other forms over the centuries. It is mentioned in print as early as 1549, but probably significantly predates this.

Extract from The Tale of Tam Linn

By Lari Don

Published by Floris Books

Once upon a time a girl called Janet lived in the Scottish borderlands. Her father was the Laird of Carterhaugh, who owned many fields and hills, and the beautiful Carterhaugh Woods.

Janet was allowed to walk in the fields and on the hills, but she wasn’t allowed to walk into the woods.

All the children of the Borders were told the story of a boy called Tam Linn, who had been stolen by the fairies in Carterhaugh Woods. They were told the story of a fierce fairy knight who now guarded the woods for the fairy queen. And they were told never to go into the woods.

But Janet didn’t believe in fairy stories and Janet didn’t like being told what to do. So one bright October day, she crept out of the Laird’s house and strode into Carterhaugh Woods.

She walked through the tall trees. She nibbled ripe fruit and listened to tiny birds calling.

She found a stone well with a rose bush growing beside it, and reached out to pick a late flower blooming on a thorny twig.

The stem snapped.

And Janet heard a voice above her: “The fairy queen won’t like that.”

Mysterious selkies, bad-tempered giants, devious fairies and even Loch Ness’s most famous resident – these are the mythical beasts of Scottish folklore. Alternately humorous, poignant and thrilling, each story is brought to life with exquisite illustrations by Scottish fine artist Kate Leiper.

Extract from An Illustrated Treasury of Scottish Mythical Creatures

By Theresa Breslin, illustrated by Kate Leiper

Published by Floris Books

Loch Ness is an ideal place for a monster. It is so deep that it has more water in it than all the lakes of England and Wales added together – so who knows what might be lurking in a cave far below the surface?

There is a record of a massive beast terrorising the folk who lived near Loch Ness when St Columba of Iona was visiting the area. The people there, who spoke Gaelic, named it Niseag, which became ‘Nessie’ in English – the name by which our monster is now known all over the world.

McKenzie resolved not to mention the monster to anyone. Folk did gossip about seeing monsters but few believed these stories. If he told of what he had seen, people might laugh at him. Or, if they thought his tale was true, they might hunt the monster – out of fear or for food. They definitely wouldn’t be happy with what he was doing, which was dropping some fish into the water whenever he passed that spot in the loch.

Later that same winter, McKenzie was on his route to Inverness one evening when a storm blew up. The wind strengthened, and hail beat in his face. He had no passengers on board, and he was glad of that, for the boat was heaving as the heavy current dragged it along. Using all his strength McKenzie grasped the tiller to guide his boat. If he didn’t deliver his cargo of barrels and boxes to Inverness he would not be paid. The waves grew stronger and pounded against the hull as he tried to hold his boat on a steady course. Then a freakish gust struck. The boat spun out of control, and with a horrible grinding tearing noise, the rudder broke off!

Read the full extract

Drawing on universal themes of womanhood and on history, culture and lore, The Four Marys is a riveting exploration of the complexities of motherhood: edgy and engrossing, moving and at times disturbing.

Extract from The Four Marys

‘The Seal Woman’

By Jean Rafferty

Published by Saraband Books

Down, deep in the green they swam, Mhairi and her sisters, sliding through the currents like silk through a wedding ring. It was dark down there, murky, with the salt sea stippling their skin and the hissing sound of their flippers swishing through the water. All round the north they had swum, and down through the Western Isles, where the beaches were white as bone and the waters turquoise and purple and as green as seas in the warmest corners of the world.

Now they were returning to the flat island out in the middle of the ocean. Not that it was more beautiful here, or the waters clearer, or the fish more plentiful. But it was here that they had started out from and here they always came back to. They had been gone too long and Mhairi wanted to see it. Her head surfaced from the water like a chubby periscope, her brown eyes taking in the rocky bay, the scrubby slope stretching back from the beach and then the distance where she could not see. ‘The land beyond’, she thought of it, and it held a powerful lure for her. There was a world beyond this watery world of theirs, a world she glimpsed but could not reach.

Mhairi had swum many miles but this island was her home, this and the seas around it.

‘Mhairi,’ called her sister, and she followed in pursuit of a shoal of fish, dipping her head and allowing the currents to pull her down into the water’s depths. They worked fast, searing through the silvery creatures and snatching them in their mouths before swallowing them whole. But later Mhairi came back to the bay. She could not stay away.

The land was dark now. From the water, the beach and the rocks and the slick of green land beyond all merged into one indistinguishable smudge. Brown eyes slowly traversed the landscape. Looking. Longing, on this twilight evening, for the sound the woman made, the sound of human music.

There was none here when they were growing up, but since the woman had come the music had started. She would stand on the rock and coax the music from a curious wooden box for them, just for them. Mhairi’s sisters tried to shut their ears to it – they thought it sounded screechy – but Mhairi couldn’t. On nights when the woman was happy, the music was fast and gay, tripping out of the instrument the way water bubbled up sometimes across the rocks. On nights when she was sad, the music was low and sweet and plaintive and filled Mhairi with feelings that were too large for their life beneath the water.

The women of Morag’s family have been the keepers of tradition for generations, their skills and knowledge passed down from woman to woman, kept close and hidden from public view, official condemnation and religious suppression.

Richly detailed, dark and compelling, d’Corsey magically transposes the old ways of Scotland into the 20th Century and brings to life the ancient traditions and beliefs that still dance just below the surface of the modern world.

Extract from The Bonnie Road

By Suzanne d’Corsey

Published by Thunderpoint Publishing

My grandmother passed me in transit. She was leaving, I was coming into this world, our spirits meeting at the door to my mother’s womb, as she bent over the bed to close the thin crinkled lids of her own mother’s eyes. The same bed I sleep in now, where sometimes my dead Gran still visits, standing at my feet when she has a message to impart, or sometimes just for the hell of it. I’ve lost three lovers very abruptly when she’s shown up in this manner, aye, one through the window and down the old rowan tree, the same route by which access had been gained, right enough, and twice as fast.

Some lovers are excited by the idea of sharing a witch’s bed. The magical thrill draws them in, the power of the witch’s green eyes, the unabashed desire directed at them, rumors of ritual sex-magic and occult practices, a dangerous edge to the passions already ignited. All is well until they discover she really is a witch. In the heat of passion the spirits visit, the cat has a knowing wink, the sighs and whispers are joined by others unseen. A chuckle in the ear from an invisible throat, a presence at the bedside, a transformation of the witch-lover into some indefinable creature, no longer human. Then is the safe boundary of their fantasy dashed, and away they flee, leaving me to sigh or curse in my rumpled sheets.

Then there are the others, the brave few who seek the awakening of an innate wisdom, who know that those who can offer this ancient gift with skill and knowledge are rare indeed.

It’s true, time is an estuary river flowing back on itself, and we Gilbrides have only to ease a hand into the stream to see the spirals of history rippling about us.

My grandmother kissed me as she went by. There may have been enough vestige of the physical world in her yet to create a bit of heartbreak, both at leaving her own daughter, as magnificent a witch as ever traipsed over the ancient cobbles of the town streets, and at not having the opportunity to dandle this new bairn on her knee. And she gave me the gift in that interchange. Not only her Highland name, Morag, to be mine. She kissed to life a double spirit. A duality that can see the past and sense the future. And the irrepressible desire to manifest divinity in the act of lovemaking.