We’re in the final glorious days of summertime, and not ready to pull out our woolly jumpers quite yet. (Let’s be honest, a few of us only just put them away.) So, before the nights start drawing in and whilst we can still justifiably lose ourselves in an evening BBQ until one o’clock in the morning, it seems like the perfect time to talk about some of the best reads of the summer.

For Going Away

Want an entertaining little number for those lazy afternoons on a beach or in a European café?

Glad you asked – Graeme Macrae Burnet’s The Disappearance of Adèle Bedeau (Saraband) is set in a French bistro, where protagonist Manfred Baumann is obsessed with his alluring waitress. When she disappears, he is forced to confront his own dark past. Smart, imaginative and psychologically intriguing, this crime novel stands out from the pack.

At the other end of the spectrum, Animals (Canongate) by Emma Jane Unsworth is a filthy, funny, uproarious and refreshingly honest story about friendship and the morning after the night before. (The editor of this article laughed to the point of public embarrassment…and then gave her copy to the plane passenger next to her, upon request.)

Short story collections are perfect for dipping in and out of, and we love this one from Janice Galloway: Jellyfish (Freight) takes as its theme David Lodge’s assertion: ‘Literature is mostly about having sex and not much about having children; life’s the other way round.’ We hope you’re intrigued.

A Broken Hallelujah (Sandstone) by Leil Leibovitz is a revealing biography of music legend Leonard Cohen. Chosen as a BBC Radio 4 Book of the Week, the book traces the man from his devout Canadian Jewish origins to his passionate following which continues to span generations.

We have long adored prose master Ali Smith, and this is her moment with the publication of How To Be Both (Hamish Hamilton). With a Man Booker shortlisting, Folio Prize nomination and Costa Novel Award forming just a few of its accolades, we’re sure we don’t need to say it, but please read this book!

For Staying Close to Home

Sometimes home holidays are just the best. Here are a few titles to help make it a summer to remember.

Or not remember, as the case may be. 101 Gins to Try Before You Die (Birlinn) needn’t be fully tested this summer, but it is an excellent guide for your sunny afternoon tipple. Funny, more than a little sceptical, and highly informed, we found this book to be just plain good reading, with or without a gin.

Evocative and beautifully written, The Gracekeepers (Harvill Secker) draws on Scottish folklore and fairytale, reimagining them in such a masterful way that the book has drawn comparisons to Angela Carter. Kirsty Logan’s debut novel follows two young women in a watery future, where the sea is home and access to land is a privilege. Replete with a circus and a troupe of characters you’re sure to fall in love with, this book is truly a delight.

With recipes fancy enough for entertaining, A Girl and Her Greens (Canongate) from renowned chef April Bloomfield make vegetables a truly special affair. The wonderful thing is that it’s really a book for all seasons (Swiss Chard Cannelloni this winter, anyone?!), but no moment better for veggies than the lovely green season upon us.

The Parlour Café Cookbook (Kitchen Press) by Gillian Veal and The Three Chimneys Cookbook (Mercat Press) by Shirley Spear offer destinations in their own right. Whether you venture to Dundee or Skye to visit the restaurants from which these recipes come, or whether you decide to bring their magic to your own kitchen, both of these cookbooks are chock-full of gorgeous recipes and, visually, are a real pleasure to look through.

Finally, it would be remiss of us not to remind you how rich, varied and beautiful our own landscape is. No better book to do the job than Scotland’s Landscapes (RCAHMS). These photographs will take your breath away, and (we suspect) tempt you to go and have a look for yourself.

Award-winning and much-beloved children’s book author, Debi Gliori, is this year’s illustrator-in-residence at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. The author of such modern classics as No Matter What, What’s the Time, Mr. Wolf? and, most recently, Alfie in the Garden and Alfie in the Bath, she took a few minutes out of her busy schedule to talk to us about watercolours, dragons and the best advice she could ever give anyone.

BFS: Your work addresses the big questions of childhood, and touches on everything from the arrival of new babies to the fear of being alone, from non-conformity to environmental responsibility. How does illustration allow you to explore such complex topics, and do you adapt your style to individual themes?

DG: Illustration is an infinitely flexible gateway into exploring the big questions – it will boldly go where words cannot, or perhaps where words would express a difficult subject in too direct a fashion. In truth, when I begin to write a book, the first thing that comes to me ideas-wise is always an image. I write for and to and about the pictures in my head. The whole of my practice is about endeavouring to put those pictures down on paper without anything getting in the way. I’ve found that illustration allows me to explore some very sensitive themes in a way that doesn’t threaten the small children who the books are for. By drawing animals as my protagonists, I can tackle the big questions of childhood at one remove; children can identify with what the animals are feeling without themselves feeling in any way exposed.

I do adapt my style to whatever theme I’m working with; I’ve been using a smudgy, atmospheric charcoal style to convey the Antarctic winter in Dragon Loves Penguin but that darkness wouldn’t work for, say a book for much younger children, like Alfie in the Garden. My book about climate change required a lot of hot colours (the protagonists are flame-red dragons) and watercolour was the perfect medium. I’ve just completed artwork for a bedtime book called Goodnight World where I wanted smudgy, atmospheric darkness to slowly creep across the pages, but I also wanted the luminous quality of watercolour to portray that glorious, snug, all-tucked-in feeling of winter twilight; for that I used both watercolour and charcoal.

BFS: Artistry is a very personal endeavour. How much of your own experience finds its way into your work?

DG: Oh! Only my entire life. Suitably disguised, though. I am continually mining my past for the subject matter of my books, but usually not consciously. It tends to be only after a book is published and has been Out There for a few years that I suddenly realise where it came from. To my embarrassment, many of my characters are facets of myself at various stages of life… Who knew I was Mr Wolf? Or a grandma dragon? But there I am, gazing back at myself.

BFS: Where do you go looking for inspiration as you create new characters?

DG: Not far. I’m not very well-travelled. I do love walking as a means to dredge an idea up from the deep. There’s something about the rhythm of footsteps and the almost meditative trance I fall into as I walk that is the best way I know to access the place where ideas come from.

BFS: As the illustrator-in-residence this year at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, what kinds of conversations do you hope to have with your audiences?

DG: Hugely varied conversations from the surreal banter I enjoy with very small children to the more rigorous questions coming from an adult audience, our subject matter will range widely from issues surrounding mental health, how to survive depression, how to bath a bunny or employ him usefully in a garden, how much of our personal lives do we pour into our books, what it felt like to be nearly killed by the Taliban, what we can do about our rapidly-heating planet and can ginger cats really count to a billion? What an amazing Book Festival we’re going to have!

DG: Hugely varied conversations from the surreal banter I enjoy with very small children to the more rigorous questions coming from an adult audience, our subject matter will range widely from issues surrounding mental health, how to survive depression, how to bath a bunny or employ him usefully in a garden, how much of our personal lives do we pour into our books, what it felt like to be nearly killed by the Taliban, what we can do about our rapidly-heating planet and can ginger cats really count to a billion? What an amazing Book Festival we’re going to have!

BFS: Is there any advice you would give to aspiring writers and artists

DG: Unto your own self be true. I wrote this on an illustration for my godson, and I think it’s the best advice for anyone, regardless of their chosen profession. You are a unique human being; use that as the seedbed of all your endeavours. And read books by the thousands. Fill your head with stories.

The New Writers Award recognises serious aspiring writers and provides them with the opportunity to develop their craft. Watch this space for the new up-and-coming names in literature.

This month, we introduce you to the writing of awardees Lindsay MacGregor and Rachelle Atalla.

Extract from ‘Spine’

By Rachelle Atalla

Full short story published in Gutter, Issue 12, February 2015

I noticed a young boy approaching, carefully, through the rows of people spread out in the sun. Turning his back to me, he came to a stop in front of my lounger and sat down in the sand. He wore no t-shirt, only shorts and a baseball cap that was too big for his head. He was thin, unbearably thin; a thinness that made me feel sick. He could have only been about ten but he resembled an old man – skin and bone worn away to nothing. He gripped a backpack in his right hand that looked empty. On his wrist he wore red and yellow beads – the beads could have been made for a toddler. From my lounger, I shifted slightly, giving myself an elevated view of his movements. The boy stretched himself out, placing his backpack behind his head to create a pillow. He ran his fingers through the warm sand, clawing handfuls, letting his fingers fall flat again. He moved his body from side to side, suddenly sitting up, drawing his knees close to his chin and burying his toes under the sand. In that position, I saw the entire framework of his spine. Every bone protruded out towards me, allowing me to see how he was made. He seemed hardly a person in that moment – just an arrangement of bones. He lay back down and within minutes was sleeping soundly, his face turned away from the sun. It made me wonder what would become of my bones once I was gone. I had always disliked the idea of cremation. My parents had bought their cemetery plot when I was a child, needing to be together, one on top of the other. I’d never had their foresight.

The boy could only have been asleep for twenty or thirty minutes, but for all that time I watched over him, imagining I was protecting him from whatever harm I thought might approach. He had scars on his arms; the scars pale against his dark skin. I found myself thinking pigmentation was a strange thing. Who had given him those scars? Or had he made them himself? I thought about my butchered bowels and what was left of them. I wanted this boy to know I cared for him. We were united, this boy and I, from circumstances out of our control.

He woke, rubbing his eyes slowly, and sat up, grabbing his hollow backpack. He took a yellow football top out of the bag and pulled it over his head with the baseball cap still on. Like the cap, the shirt was also too big, drowning him. There was a price tag hanging from the back of his shirt, which didn’t seem to bother him. He got to his feet, weaving through the loungers and towels, until he was away, lost to me through the crowds of people.

Poems

By Lindsay Macgregor

The Lewis Chesswoman

She knows she’s just a dolled-up

pawn to him. Slugs more mead.

Recites the game-plan in her head,

rehearses every sideways move.

How she’d love to go berserk

with mitts like these, his bishops

putting shame to shame. Instead,

it’s constant stalemate.

(In Poetry Scotland)

Cudknot

Year upon year, she mowed the back lawn,

Backward and forward, come hell or high water.

Thirty years on, she looked past the fence

To a field of cudknot and fescues – a mess.

So she mowed down the field till she blunted the blades

Then she shoved and shunted; she started again.

Out past the pond to the lip of the river,

She striped every field from Ceres to Cupar.

In a year and a half she got out to the cliffs,

Left a strewing of purslane and sheepsbit and thrift.

The look in her eye pierced the eye of each daisy

Through Cornwall, past Roscoff and into the valleys

And hills of the Causse, she kept cutting those swards

And cutting and cutting and still there was more

To be mown, more to be mown as she mowed

And she mowed on right out of this world.

(Published in New Writing Scotland, 29, 2011)

Lugworming

Two lumps of men

on a plate-glass beach

vulcanised by their gear

like old buddy bull-seals

end-on to the horizon

slicing through the daily

slap of a low ebb

without ever

touching.

(Published in New Writing Scotland, 30, 2012 and Ink, Sweat and Tears)

Sunday Rituals

Someone sits at a window

as rain runs from gables

in unbroken lines.

At an upright piano

another sings psalms

of the Fathers.

A shepherd lies down

in the dunes. These are surely

most terrible times.

(In Ambit, 219, 2015)

Teatime in Paris! guides you to many of Paris’s best patisseries and tea salons, and introduces you to the simplest ways to make your own iconic French treats

Recipe from Teatime in Paris!

Éclairs à la fraise et fleurs de sureau

By Jill Colonna

Published by Waverley Books

Nut free

Makes 8 éclairs

Preparation time: 25 minutes

Cooking time: 35 minutes

Temperature: 160°C/320°F fan (Gas 4)

Choux dough:

75g water

50g milk

½ tsp sea salt (or fleur de sel)

1 tbsp sugar

45g butter

75g flour (plain, all-purpose)

2 eggs

24 strawberries

Pastry cream:

250g full-cream milk

1 vanilla pod (or beans)

3 egg yolks

30g caster sugar (superfine sugar)

20g cornflour (cornstarch)

1 tbsp elderflower syrup (I use Monin’s)

Serve with elderflower cordial, or Darjeeling or jasmine tea

One particular pastry chef, Christophe Adam, showcases his “genius éclairs” in Rue Pavée, between the Hôtel de Ville and Place des Vosges in the Marais. Éclairs are not only easy to make but they’re one of my favourite ways of serving up the best-tasting strawberries when they signal springtime. There’s no need to make a glaze to coat the éclairs: just dust them with icing sugar. They are generously filled with a delicious pastry cream with a hint of elderflower, which goes beautifully with strawberries due to its floral notes and a nudge of lychee.

Try to find the shiniest, sweetest red berries in season, to appreciate the delicate taste of elderflower. In the French markets, the most popular, highly flavoursome strawberry varieties are Gariguette, Mara des Bois and Charlotte. If you can’t get elderflower syrup why not use your favourite floral essence or try St Germain elderflower liqueur.

Preheat the oven to 160°C/320°F fan (Gas 4).

Make choux dough as in the recipe on page 64 (except make a half quantity).

Using a piping bag with a 12mm (½”) serrated tip, pipe out long éclairs to about 12cm (4¾”) on baking trays covered with greaseproof/baking paper (or a silicone mat). Leave a good space between each of them, as they will spread out during baking.

Bake in the oven for 25–30 minutes until golden-medium brown. Leave éclairs to cool on a wire rack then cut the tops off horizontally.

Follow the pastry cream method on page 72, adding the elderflower syrup at the end of whisking. Immediately cover the pastry cream with cling film and, when cool, chill in the fridge for at least an hour.

Pipe out a generous line of cream on the bottom half of each éclair, top with four or five strawberries (if they’re big, cut them in half). Crown with the éclair tops and powder with icing sugar. Chill until ready to serve.

See Edinburgh like you never have before. Explore the rooftops and high places of one of Europe’s most iconic cities with visually stunning photography, helpful annotations and the occasional poetic gem.

Extract from Look Up Edinburgh

By Adrian Searle and David Barbour

Published by Freight Books

Our Plea to the Balmoral Clock

Ron Butlin

Gazing down upon our all-too-human delay

of unfinished city streets and roofs,

upon a mortality that clearly

cannot be relied on,

You seem to promise us – what?

Do you feel the urgency behind our as-yet

unspoken words of love, the ache within

the gestures we lack the courage

to complete? Do you understand our need for hopes

and fears to free us from the present?

If so, what we ask of you is this:

let whatever time you choose to show

be intended as an invitation,

and a blessing on us all.

Balmoral Hotel, 1 Princes Street

Originally named the North British Hotel, after the North Bridge Railway who built it, until bought and refurbished in the late 1980s. I worked as a hotel porter here in the mid-80s and love the building. It has five floors beneath the Princes Street entrance and five above. Sadly the Waverley Station entrance is no longer in use. Famous guests include the Queen and Robert Maxwell, during the 1986 Commonwealth Games, Michael Palin, and, most famously, JK Rowling, who completed a number of the Harry Potter books in a room in the hotel, now named after her. The feature film Hallam Foe, starring Jamie Bell, was filmed in and around the hotel. Intricate details can be found across the building, including multiple oriel windows, a form of bay window that projects from a wall. Two reclining male figures greet guests from the entrance. The famous clock, visible from multiple points, is still set a few minutes fast to help people rushing for their train. And for those who look closely, there are a number of superb gargoyles just below roof level.

Melville Monument, St. Andrews Square

Controversial lawyer and Tory politician Henry Dundas 1st Viscount Melville was the namesake of this 41m high monument. Melville was the last person to be impeached from public office in the UK, for misappropriation of public funds, although he wasn’t convicted. He was nicknamed the ‘Uncrowned King of Scotland,’ such was his grip on Scottish political life. He was also a leading opponent of the abolition of slavery. The monument features a large statue of Dundas at the top, but, more interestingly, four eagles’ heads protrude from each corner of the huge plinth.

Standard Life Building, George Street

Built to replace a previously demolished building, dating back to 1839. The pediment sculpture, designed by John Steell, represents the Wise and Foolish Virgins from the Gospel of St. Matthew. A frieze of naked children with swags of flowers and fruit, as symbols of abundance, also run around the whole building. The modern annex was built in 1975, the fabulous bronze relief on the same religious subject matter being added in 1979, although at the moment the sculptor is unknown. In this instance the Five Wise Virgins are identical, in a row, bare-breasted. To their left are the Five Foolish Virgins, separate and clothed, in attitudes of despair and anguish. The frieze is read from left to right. The Foolish Virgins represent: Wistfulness, Self Absorption, Panic, Despair and Procrastination. The Wise Virgins, ‘being perfect, their transcendence has rendered them identical and equal.’ Robert Palmer would approve.

Gardens can be one of the most important elements of our cultural history, and yet they are also some of the most fragile, susceptible to change, abandonment and destruction. This book traces the fascinating stories of Scotland’s gardens of the past, as well as the history of the nation which these landscapes reveal.

Images from Scotland’s Lost Gardens: From the Garden of Eden to the Stewart Palaces

By Marilyn Brown

Published by RCAHMS

A selection of some of the most important works in Western art, from the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and the Scottish National Gallery

Images from 100 Masterpieces

Edited by John Leighton

Published by National Galleries of Scotland

- Bernardo Daddi: Triptych, 1338

- Diego Velazquez: An Old Woman Cooking Eggs, 1618

- Sir Henry Raeburn: Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch, about 1795

- Vincent Van Gogh: Olive Trees, 1889

- Sir Anthony van Dyck: Princess Elizabeth and Pricess Anne, Daughters of Charles I, 1637

- Richard Dadd: Sir Alexander Morison, 1852

Longlisted for the Guardian’s Not the Booker Prize, Tokyo takes us deep into the heart of the city and into Nicholas Hogg’s rich storytelling.

Extract from Tokyo

By Nicholas Hogg

Published by Cargo

MAZZY LOOKED DOWN onto moonlit clouds. No break in the feather bed cumulus laid out from LA to Tokyo. There had been one shining moment, when a streak of silver glittered on the surface of the sea, like a sheet of worked metal. Then again the cloudscape, the anger at being pulled from a Californian high school to Japan, her father. So she looked to the perfect moon, craters and scars from ancient collisions. Lonely in the thoughts of a lifeless rock, she turned back to the plane and the sleeping passengers. Some comfort in the other bodies.

The Japanese man beside her was in his mid-twenties. Hard to tell with skin that even toned and smooth. He was sleeping. Or his eyes were simply closed. Mazzy would have to wake him to excuse herself past to go to the bathroom. It seemed a shame to disturb his peace, the Buddha-like repose. The faint lines at the corner of his mouth were the only hints of ageing, and the more she looked the more immaculate he seemed to appear. Five hours into a transpacific flight his black shirt was barely creased, and not a strand of his thick dark hair out of place.

Still, she wasn’t holding it in across the width of the Pacific.

“Sorry,” she said. “Excuse me.”

He didn’t even seem to be breathing, let alone waking to allow her past. She had to reach over and touch his arm.

He opened his eyes and stared, as if she were some precious creature stepped from his dream.

“I need the bathroom,” said Mazzy, pointing down the plane.

Slowly, the man nodded. Though rather to approve some private thought than to acknowledge her presence. Again, she said she had to use the bathroom. This time he smiled and stood, bowing a polite apology as she squeezed out from the seats.

Mazzy walked past the slumbering passengers. Slurred faces before the glowing screens. She didn’t see how he watched her walk the darkened aisle, the way she tied back her long blonde hair. She took her time in the cubicle. Washed her hands and studied her eyes. Her father’s daughter, she knew that much. His high, stern, forehead, a serious focus to her resting features. But the wide smile breaking out across her cheeks when needed.

When she got back to her seat the Japanese man was looking out of the window. Sitting in her place. His face almost pressed to the glass. Now she noticed marks under his jaw, a bruise or graze running under his left ear.

Perhaps he saw her reflection, the change of light. He quickly turned and apologised. “Sorry.” An American accent to his broken English. “I had to look at the moon.”

He shifted over then stepped into the aisle, so Mazzy could move past.

“It’s beautiful on the clouds,” she said, sliding back to her place.

Before she began the inevitable small talk on who was going where and why, he asked her if she knew the Japanese folk tale about a moon princess.

“A moon princess? I don’t think so.”

Whether the man took this as an invitation to tell seemed unimportant. He had to tell. He sat straight and erect, spoke.

Winner of the Guardian’s Not the Booker Prize, and endorsed by Emma Jane Unsworth and Lisa O’Donnell amongst others, this meticulously-researched debut novel questions our perception of contemporary femininity. Have a look at Freight Books’ reading group guide to enhance your reading experience, and read an extract below.

Extract from Fishnet

By Kirstin Innes

Published by Freight Books

The next morning, she’s laid out there on the pillow beside you. Corn-yellow hair matted across her cheeks, crusty grains of makeup under her eyes and a sharp, feral smell rising from the duvet. You suspect maybe she’s wet herself, but she looks happy as a baby. Half a smile stuck gummily round her mouth.

It rushes through your system as you sit up, toxic pressure on sinus, stomach. Still, you’re awake, and still held together by skin. Underneath, though, that black emptiness of a comedown beginning. Pending holocaust of organ tissue.

The toilet flushes. Still here. At least he hasn’t done a runner on you. Why would he? The club’ll be paying for the room. Tooth marks on your shoulder. A towel or something on the floor near the bed. You pull it round yourself to cover up before he comes out, just observing formalities.

Water running.

Jammed stinking ashtrays and champagne bottles crowning the furniture, the cold slime of a spent condom underfoot; all that tawdry sort of carnage from other people’s money that you don’t think you’ll mind the next day. Her knickers are hanging off the doorknob, yellow-stained gusset peeking outwards, dainty.

Read the full extract below

Shortlisted for the Guardian’s Not The Booker Prize, chosen as an Amazon Rising Star and tipped by the Independent as ‘the next Gone Girl‘, this accomplished thriller explores themes of guilt, innocence, collusion and the search for belonging. Watch the book trailer and read an extract below.

Extract from Things We Have in Common

By Tasha Kavanagh

Published by Canongate Books

The first time I saw you, you were standing at the far end of the playing field near the bit of fence that’s trampled down, where the kids that come to school along the wooded path cut across.

You were looking down at your little brown straggly dog that had its face stuck in the grass, but then you looked up in the direction of the tennis court, your mouth going slack as your eyes clocked her. Even if I hadn’t followed your gaze, I’d have known you were watching Alice Taylor because she had that effect on me too. I used to catch myself gazing at the back of her head in class, at her silky fair hair swaying between her shoulder blades as she looked from her book to the teacher or said something to Katy Ellis next to her.

At that moment she was turning to walk backwards, saying something to the girls that were following her, the sketchbook she takes everywhere tucked under her arm. She looked so light and easy, it was like she created space around her: not space in the normal sense but something else I can’t explain. Even in our green school uniform it was obvious she was special.

If you’d glanced just once across the field, you’d have seen me standing in the middle on my own, looking straight at you, and you’d have gone back through the trees to the path quick, tugging your dog after you. You’d have known you’d given yourself away, even if only to me.

But you didn’t. You only had eyes for Alice.

With the second book in the series, Did I Mention I Need You?, coming in September 2015, now is the perfect time to remind yourself why this book became a YA hit this summer.

Extract from Did I Mention I Love You?

By Estelle Maskame

Published by Black & White

If movies and books have taught me anything, it’s that Los Angeles is the greatest city with the greatest people and the greatest beaches. And so, like every girl to ever walk this earth, I dreamed of visiting this Golden State. I wanted to run along the sand of Venice Beach one day, to press my hands on my favorite celebrities’ stars on the Walk of Fame, to one day stand behind the Hollywood Sign and look out over the beautiful city.

That and all the other lame tourist must-dos.

With one earphone in, my attention half on the music humming into my ear and half on the conveyor belt rotating in front of me, I try my hardest to find a spot clear enough for me to haul my luggage. While the people around me shove and chat loudly with their partners, yelling that their luggage just went past and the other yelling back that it wasn’t actually their luggage, I roll my eyes and focus on the khaki suitcase nearing me. I can tell it’s mine by the lyrics scrawled along its side, so I grab the handle and yank it off as quickly as I can.

“Over here!” a familiar voice calls. My father’s astoundingly deep voice is half drowned out by my music, but no matter how loud the volume I would probably still hear him from a mile away. His voice is too irritatingly painful to ignore.

When Mom first broke the news to me that Dad had asked me to spend the summer with him, we both found ourselves in a fit of laughter at the sheer insanity of it all. “You don’t have to go anywhere near him,” Mom reminded me daily. Three years of hearing nothing and suddenly he wanted me to spend the entire summer with him? All he had to do was maybe start calling me once in a while, ask me how I was doing, gradually ease himself back into my life, but no, he decided to bite the bullet and ask to spend eight weeks with me instead. Mom was completely against the idea. Mom didn’t think he deserved eight weeks with me. She said it would never be enough to make up for the time he’d already lost with me. But Dad only got more persistent, more desperate to convince me that I’d love it in southern California. I don’t know why he decided to get in touch out of the blue. Was he hoping he could mend the relationship with me that he broke the day he got up and left? I doubted that was even possible, but one day I caved and called up my father to tell him that I wanted to come. My decision didn’t revolve around him, though. It revolved around the idea of hot summer days and glorious beaches and the possibility of falling in love with an Abercrombie & Fitch model with tanned skin and an eight-pack. Besides, I had my own reasons for wanting to get nine hundred miles away from Portland.

So, I am not particularly thrilled to see the person approaching me.

A lot can change in three years. Three years ago, I was three inches shorter. Three years ago, my dad didn’t have noticable graying strands throughout his hair. Three years ago, this wouldn’t have been awkward.

I try my hardest to smile, to grin so that I won’t have to explain why there’s a permanent frown sketched upon my lips. It’s always so much easier just to smile.

“Look at my little girl!” Dad says, widening his eyes and shaking his head in disbelief that I no longer look the same as I did at thirteen. Oh, how shocking that, in fact, sixteen-year-olds do not look the same as they did when they were in eighth grade.

“Yep,” I say, reaching up and pulling out my earphone. The wires dangle in my hands, the faint lull of the music vibrating through the buds.

“I’ve missed you a lot, Eden,” he tells me, as though I’ll be overjoyed to know that my dad who walked out on us misses me, and perhaps I’ll throw myself into his arms and forgive him right there and then. But things don’t work like that. Forgiveness shouldn’t be expected: it has to be earned.

However, if I’m going to be living with him for eight weeks, I should probably try to put my hostility aside. “I’ve missed you too.”

Dad beams at me, his dimples boring into his cheeks the way a mole burrows into dirt. “Let me take your bag,” he says, reaching for my suitcase and propping it onto its wheels.

I follow him out of LAX. I keep my eyes peeled for any film stars or fashion models that might happen to brush past me, but I don’t spot anyone on my way out.

Warmth hits my face as I walk across the sprawling parking lot, the sun tingling my skin and the soft breeze swaying around my hair. The sky is mostly clear apart from several unsatisfying clouds.

“I thought it was going to be hotter here,” I comment, peeved that California is not actually completely free from wind and clouds and rain that stereotypes have led me to believe. Never did it occur to me that the boring city of Portland would be hotter in the summer than Los Angeles. It is such a tragic disappointment and now I’d much rather go home, despite how lame Oregon is.

“It’s still pretty hot,” says Dad, shrugging almost apologetically on behalf of the weather. When I glance sideways at him, I can see his growing exasperation as he racks his brain for something to say. There is nothing to talk about besides the uncomfortable reality of the situation.

How the Kelpies Prize built Floris Books

By Chani McBain

I think we can all agree that literacy competitions are important. It’s important for authors and would-be authors to have an outlet for their creativity: to be heard, acknowledged, encouraged and rewarded. It’s important for our society and the literature sector to showcase creativity, and awards serve as a source of inspiration to anyone hesitating about whether to put pen to paper (or, more likely now, fingers to keyboards). Without contacts or nepotism, writers can have their work read and, occasionally, published.

But the truth is that they’re great for publishers as well (and literary agents and magazines and everyone else who runs a competition). Competitions allow all of us to discover new talent and to ask for work that is tailored for us, whether it’s a winter-themed haiku for a poetry magazine or romance for a woman’s magazine. So while competitions allow new voices the chance to speak, they also allow organisers a chance to listen for the right new voice for them.

This month, Floris Books celebrates a decade of awarding its Kelpies Prize for unpublished Scottish children’s fiction. And what a decade it has been!

This month, Floris Books celebrates a decade of awarding its Kelpies Prize for unpublished Scottish children’s fiction. And what a decade it has been!

Floris took over the Kelpies imprint of Scottish children’s novels from fellow Scottish publisher Canongate in 2002 – the same year that the Kathleen Fidler Award for unpublished Scottish children’s fiction was discontinued. Two years later the Kelpies Prize was awarded for the first time, supported by the Scottish Arts Council (now Creative Scotland), hoping to fill the space left by the great work of that award.

And the debt that Floris now owes the prize, and all the talented authors who entered it, is enormous. In the last 10 years we’ve published more than 35 books (roughly a third of all the Kelpies books in print) by authors discovered through the Kelpies Prize.

And for the Kelpies Prize, as with many other literary prizes, it’s not just the prizewinners who’ve gone on to be published. Shortlisting, even longlisting, celebrates something that the judges love about the book, or the author, and gets them noticed elsewhere. On many occasions we’ve gone on to publish Kelpies Prize runners up. We’ve published 14 new authors in the 10 years of the prize, including a bumper year in 2011 when we published all three of the shortlisted authors.

Although the Prize itself originally asked for children’s fiction for 8 to 12 year olds, our authors are a talented and versatile lot. Without them, our wonderful range of Scottish picture books, the Picture Kelpies, would be missing some great titles – like Thistle Street by Mike Nicholson, winner of the first Kelpies Prize in 2005. And our young teen range, KelpiesTeen, might never have been conceived without Roy Gill (shortlisted for the 2011 Prize).

As the Kelpies imprint has grown, now with books aimed at five age ranges from tots to teens, so has the Kelpies Prize. For this 2015 Prize, we opened submissions for three different categories: 6 to 8, 8 to 11 and 11 to 14 years. As a result we recorded our most submissions ever, leaving our judges with the never-enviable task of cutting down all that potential to a shortlist of just three manuscripts.

We like to think that our judges have an eye for talent and the fact that many of our Kelpies Prize authors have gone on to be recognised by other awards, seems to confirm that.

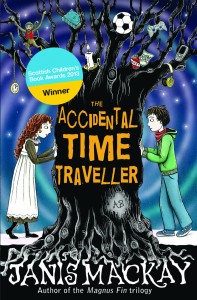

Kelpies Prize authors are the proud owners of several Scottish Children’s Book Awards (Scotland’s most prestigious children’s book prize): First Aid for Fairies and Other Fabled Beasts by Lari Don (shortlisted for the 2007 Kelpies Prize), The Accidental Time Traveller by Janis MacKay (winner of the 2009 Kelpies Prize) in a year when, incidentally, the SCBA shortlist was comprised entirely of Kelpies Prize alumni (Black Tide by Caroline Clough, winner of the 2010 Prize; and Really Weird Removals.com by Daniela Sacerdoti, shortlisted for the 2011 Prize). And just last year, Attack of the Giant Robot Chickens by Alex McCall (2014 Kelpies Prize winner) made it a hat-trick.

Kelpies Prize alumni have also been shortlisted for, and won, the Heart of Hawick Award, Solford Book Award, Hillingdon Primary Book of the Year Award and many more besides.

So while we wait anxiously for the envelope to be opened (just like the Oscars) and the giant cheque to be presented (just like the Lottery) during this year’s Kelpies Prize ceremony at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, we’ll remain hopeful for the future of our Prize and so many others like it. Hopeful and eternally grateful for the authors who take the time to submit to us, to Creative Scotland who tirelessly supports it and to the legacy that it has allowed us to create. Then we’ll take a breath and start planning for the 2016 Prize!

The 2015 Kelpies Prize will be awarded by the wonderful Debi Glori at a ceremony held at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. This year’s shortlisted books are Drowning in the Mirror by Julie Macpherson (KelpiesTeen), Monsters M.I.A. by Justin Nevil (Kelpies) and Slug Boy Saves the World by Mark Smith (Kelpies).

In Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Park, the bodies of two youths lie with bullet holes in their heads. Hungover, nicotine-starved and ill-attired, procurator fiscal Maddy Shannon attends the scene, unaware that this grim morning is about to spiral out of control. The corpses have been carefully disfigured, perhaps signs of gangland revenge or, worse, ritual slayings. Motives and suspects are hard to find. It soon becomes clear that this disturbing case will hold a mirror to the government, the church and society at large.

Extract from Potter’s Field

By Chris Dolan

Published by Vagabond Voices

The morning’s sweetness had curdled, the sky a simmering grey gruel. Maddy, heading west, waded against the flow of Sauchiehall Street shoppers. She’d worked till ten on Monday, had taken enough files home on Tuesday to bury an elephant, gone in early Wednesday and worked late last night. She could afford a little time on a Friday afternoon to tidy up her flat before the estate agent came.

Her route took her past the southern edge of Kelvingrove. There was nothing to connect the tranquil greenery, the perpetually dormant bowling greens, with the little corner of horror deep in the park’s belly. Boards outside shops blurted the deadening news. “Bodies Found in Kelvingrove”.

Glasgow spreads like a stain, weeping along the least line of resistance in every direction, between mountains, down valleys, draining into the sea. But there’s a secret geometry to it, a nervous system that makes death in the west felt and feared as keenly in Easterhouse or Giffnock. Today’s double portion was pretty much on Maddy’s doorstep. An incursion into her heartland.

At Lorraine Gardens she admired the street, as she always did, before opening the door. She’d been here for ten years, the only house she’d ever owned. The HQ of the private Maddalena Shannon, hybrid woman. A Mediterranean kitchen – terracotta tiles, colour-washed dresser, pots, pans and dried peppers hanging round the hob – that somehow looked absolutely nothing like a Mediterranean kitchen.

“White’s the problem,” Dan had said. He’d run his hand over the paint daubed straight onto the plaster, to give that Mexican adobe look. “Blue-based white doesn’t work in the north. Looks great in Andalusia, looks like dogs’ piss in Glasgow. What you need’s a yellow-based white.”

She’d salvaged from her childhood bedroom in Girvan a saccharine picture of Christ the Shepherd. Golden-locked boy in a soutane stroking a lamb. The irony hadn’t come off. The whole house was a botched blend of attempted modernity and beefy auction-house furniture. She’d considered making a move, selling up, finding somewhere new. Roddy Estate Agent looked around the flat and said: “Declutter. One little word, one big task. But worth it.”

Inspecting each room in turn, he’d propped himself up against the door jamb as if the vision before him might overpower him. He had the smile of a man consoling a bereaved but distant acquaintance. “Get rid of the books. Only leather-bound volumes sell a property.”

Unread books, in other words. Hyndland had changed. When she had arrived, she’d sneered at the dusty pretension of the place. Lecturers, doctors and dentists with clapped-out bangers rusting between Doric pillars in driveways. Art collections clustered behind unwashed windows. Patched elbows and unkempt haircuts reading on threadbare sofas. The violin and piano practices of a screech of Gails, Robinas and Leos. Maddy had shaken her head at it all, yet here she was, a decade later, mourning its passing.

It was Roddy’s area now. His soft-top silver sports car not conspicuous anymore outside her window, winking between SUVs and Beamers. At 36, Maddy was Old Hyndland while Roddy talked interactive tellies and surround-sound. Maddy blamed footballers. Once, they stayed safely out of the way in the Southside and Bothwell. Since they’d started migrating from warmer climes they preferred the liveliness of the west end. She’d spoken the thought out loud to Roddy Estate Agent, and immediately wished she hadn’t.

“Bulgarians, Hungarians, Australians.” Roddy had rapped on her theme. “I’ve sold houses to Czechs, Lats, Poles, Danes and Swedes. Organised mortgages for Spaniards, Germans, Portuguese, Uruguayans and Geordies. Makes you wonder why our teams aren’t doing better than they do.”

“Cause they’re all too busy poncing up their west end flats?” suggested Maddy. And putting them out of her price range. Still, they looked nice, the thick-locked and dark-curled foreign footballers, outside the cafes.

Roddy scanned his eyes over her bedroom like a client making up his mind in a Bangkok brothel, his gaze resting for a moment on the open-topped Moroccan laundry basket, tastefully bedecked with a pair of yesterday’s knickers.

“Roddy,” she’d said pleasantly. “Could you do me a favour? Could you get yourself to fuck out my house? Thanks.”

She had been the Procurator Fiscal in charge of a murder last year. A woman a little older than herself who had taken a knife in the stomach from a husband who had been kind and faithful for fifteen years. Moving house, apparently, had pressed the hitherto unknown button in his brain.

Maddy was walking the house with a cardboard box and a bin bag. Roddy had put her off the idea of moving in the near future but, bless him, he was right about the decluttering. Ornaments, pictures and old CDs that might fetch some charity shop a tenner were going in the box. Old letters and junk mail, general crap from ten years of living alone, in the bag.

She sat at her favourite window, the bay looking out onto a copse of trees heavy with themselves. She remembered one of her first cases. A twelve-year-old girl, snatched on a street between home and school and left all but eviscerated in a wood forty miles into the Lomond Hills. Maddy had spent nights then in this very seat at the window, weeping violently. But no tears would come now for these boys. Their hands reaching out for each other. Boys like that never reach out for one another, do they?

Walk twenty minutes in any direction from this house and you’d be in their world – Wyndford, Yoker, Ruchill. Twenty minutes to the next galaxy. Young feral males addicted to destruction, the sons of earlier feral, destructive males. They were hard to cry for. That in itself should have made her cry.