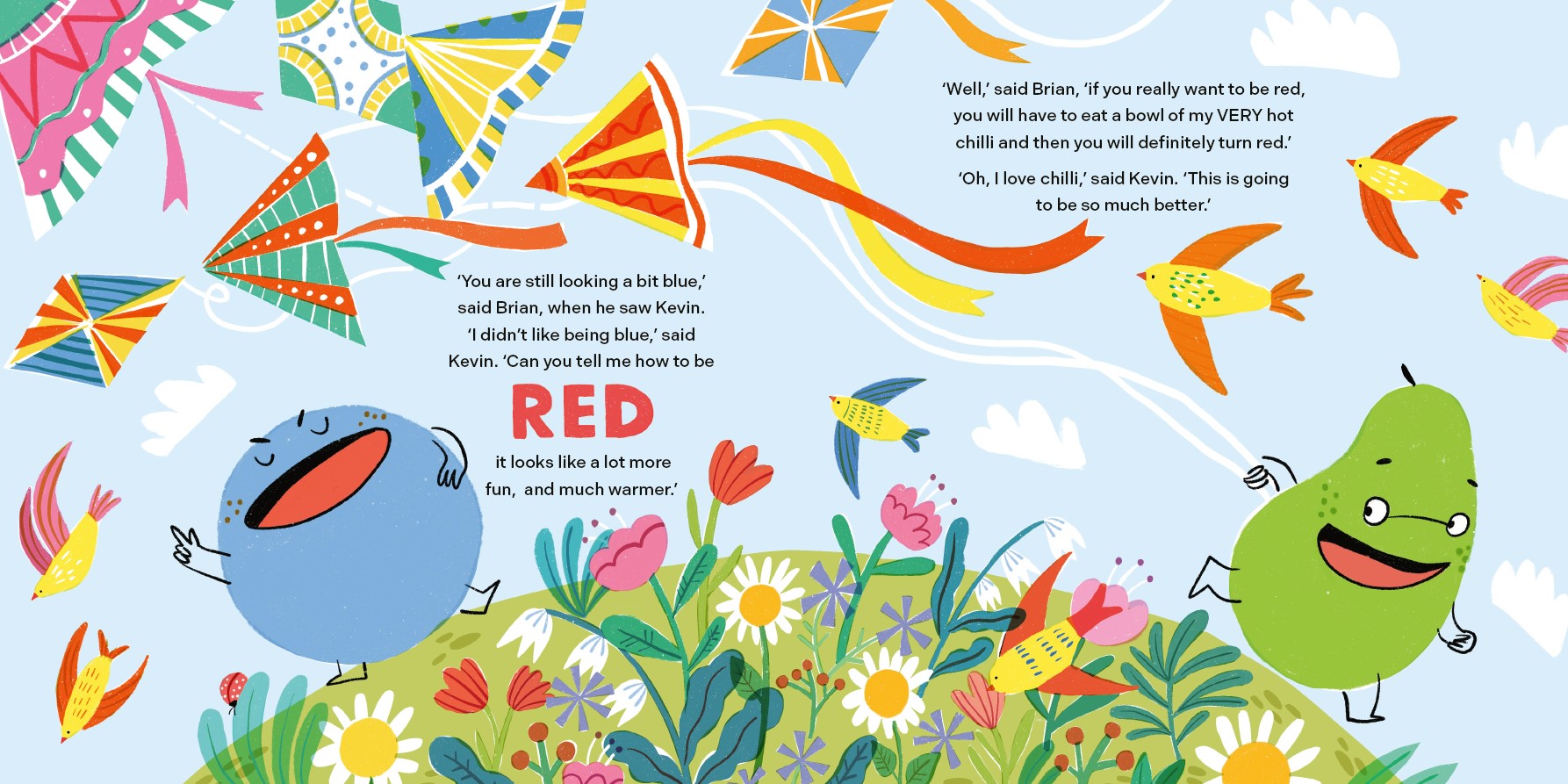

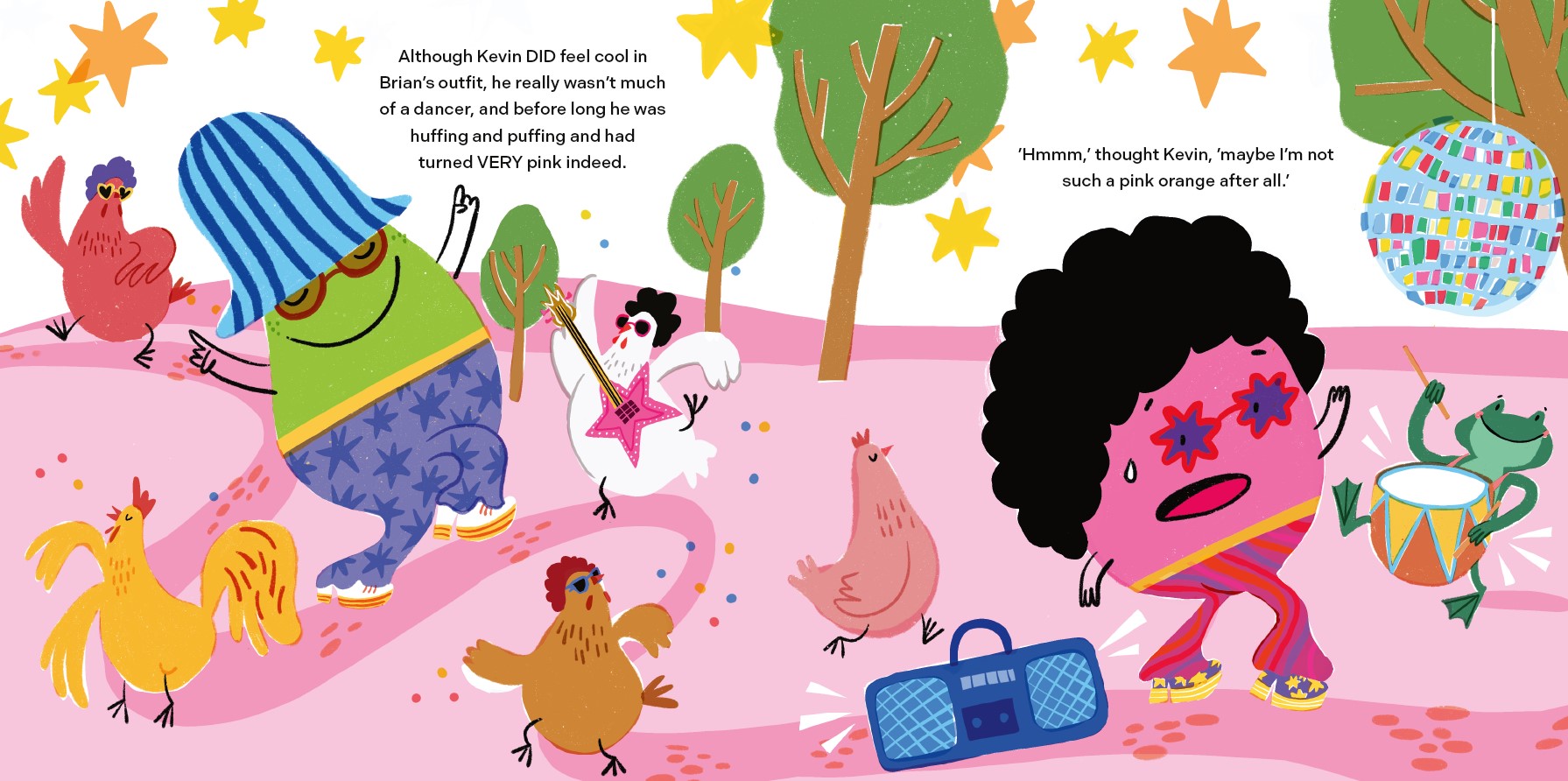

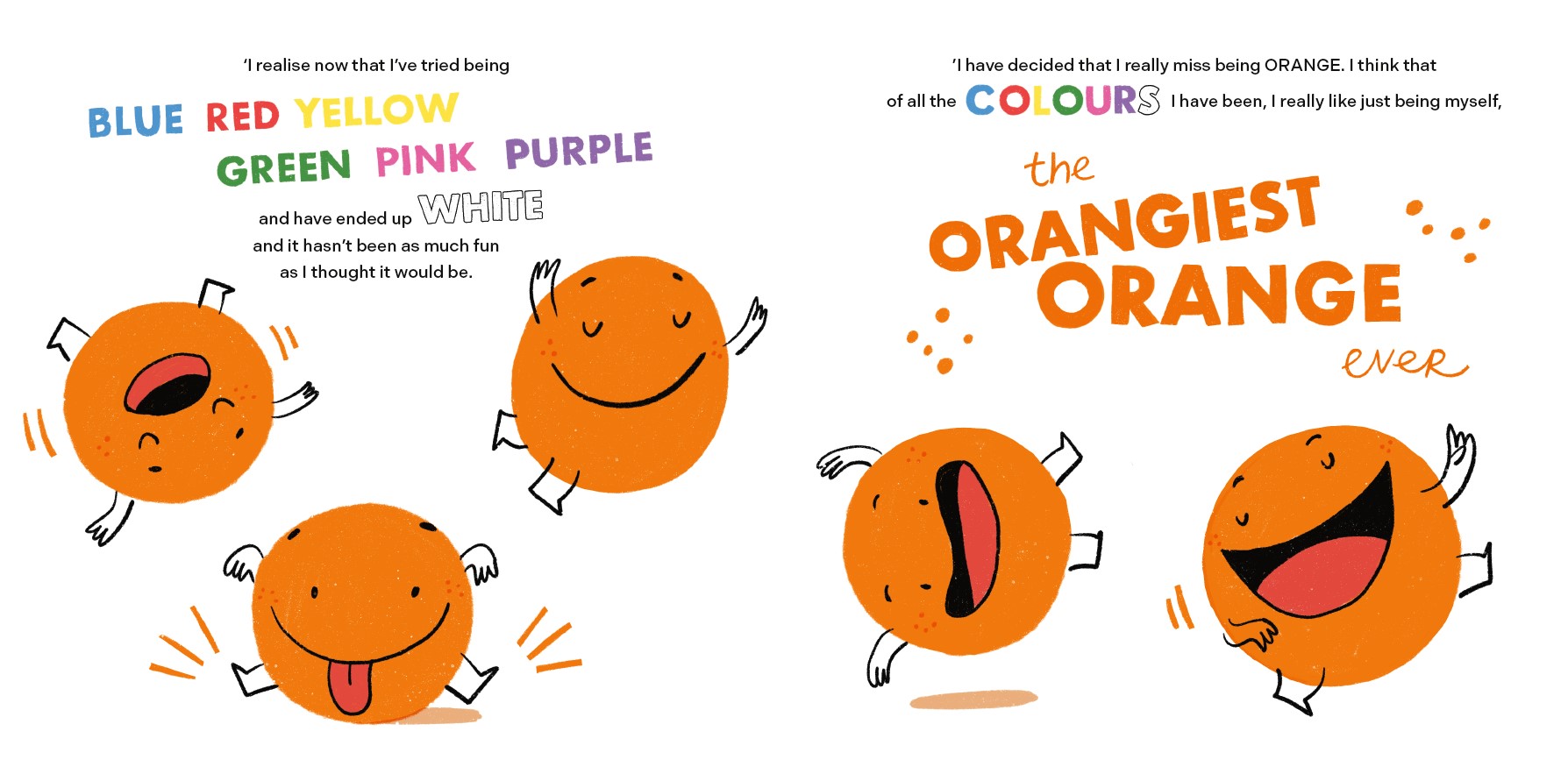

Little Door Books always publish delightfully delicious picture books, and Kevin the Orange continues this tradition.

Kevin the Orange

By Alan Windram, illustrated by Olla Meyzinger

Published by Little Door Books

Kevin the Orange by Alan Windram and illustrated by Olla Meyzinger is published by Little Door Books, priced £7.99.

Readers of Colin Burnett’s A Working Class State of Mind will be happy to hear that he has just published a follow up novel, Who’s Aldo? Catch up with him here in this extract before heading to the bookshop!

Who’s Aldo?

By Colin Burnett

Published by Tippermuir Books

Inside Out

ALDO

The mere sight ae the Royal Edinburgh Psychiatric Hoaspital is almost enough tae make me brek oot in a cauld sweat. Mean, tae the average punter, likes, this institution represents itself as a marvel ae twinty-first century engineerin. A fuckin grand monument tae picturesque mental health. Even though it is Edinburgh’s answer tae Arkham Asylum, it doesnae half gie oaff the impression ae a warm and welcomin environment. Unfortunately though, fur the cooncil that is, ah’ve watched films like Shutter Island, and they’ve helped in gaitherin enough information tae ken the only hing these places sell are nightmares.

Ah stand ootside the entrance wae ma nerves aw frayed, fumblin aboot in ma poackets tryin tae locate ma lighter tae spark up a soothin ciggie. Yince baith boaxes are eventually ticked oaff, ah take a deep drag and exhale, efter which ma eyes start tae wander as ah’m confined in a daze watchin the smoke swirl in the air. Ah then focus oan the inmates’ loved yins arrivin, each yin ae thum equipped wae what ah judge tae be hame comforts fur the respective patients. Insteed ae smoothin oor ma concerns the sight ae thum only accelerates ma anxiety levels cos ah kin see the trail ae terror and worry creepin in behind thum, like masel, ah mean. They appear hesitant tae step oan the set ae the live action version ae the Looney Tunes. Wae the shape ae their eyes they probably possess between thum mair bags than Heathrow Airport. Efter ah’m finished taken twinty years oaff ma life ah flick the fag tae the groond before crushin the butt under ma fit. Only then dae ah decide tae bow tae fate by steppin through the automated double doors.

Fae the very first second ah kin seethe interior hus under-went somewhat ae a transformation. It’s now become a relaxin and therapeutic settin, yin that wid even send that Charlie Sheen oan the road tae recovery. Soft lightnin, vivid seaside colours and some greenery in the form ae plants create this illusion. They’ve probably even forked oot some dough oan providin the inmates wae a new chew toy and a bed frame tae go wae their mattress. Still, ah remain hilehertedly unconvinced cos cunts wae nae respect fur laws or human life very likely roam these corridors unchecked. And ah’m no talkin aboot they fuds who flow through the Hooses ae Parliament. Which is why ah’ve decided tae investigate whether the décor is matched by the customer service…a thoat that spurs me oan tae advance taewards the reception desk.

Ma first introduction tae the death eaters who keep every-boady in line compels ma boady temperature tae plummet as this tall boay wae hollow eyes greets me. The mere sight ae him leaves me wonderin whether ah should hae garlic aroond ma beefy neck. It’s no a stretch tae confess this boay wid keep the Brothers Grimm awake at night. Ah pass him ma visitin order which he takes withoot declarin a word. Demostratin the people skills ae Osama Bin Laden at a fourth ae July firework display, his grubby finger points tae the large deserted seated area and ah recognise this is where ah’m meant tae wait. Ah oblige his command by trottin oor there and plantin ma erse doon. Restin up ah decide that they kin pin as many abstract paintings tae the wahs that they want, nuttin kin sway the vibes ah’m gittin that bein under loack and key in this facility is worse than any illness.

Ah sit patiently, observin a diverse range ae members ae society arrive and exit the buildin. The telltale sign that they’re here oan their ain accord lies wae the fact that nane ae thum happen tae hae a leash attached tae their collar, which is why ah estimate that they’re either visitors or cunts employed by the hoaspital itsel. It’s no long before ah spoat a muscular wuman in a nice plum print blouse appear ootae thin air. She starts chattin tae Harold Shipman’s protégé at reception. Truth is, and yae might no believe me when ah tell yae this, but ah’m no ashamed tae admit this, likes, ah honestly reckon that she could bench press mair than me.

Ah soon lift a mag oaff the small orange side table, quickly pressin it up against ma puss, hopin and prayin tae fuck that she’s no bein sent ma wey. Jist then ah kin hear the soond ae weighty fitsteps drawin in closer, threatnin noises that tell me ma future hus never looked bleaker.

‘You’re Aldo?’ asserts the wuman in her deep strong voice. ‘I cannot believe you’re an actual person.’

Ah lower this pishy magazine and it’s official, ah’ve been paired up wae Miss Trunchbull fae Matilda.

Who’s Aldo? by Colin Burnett is published by Tippermuir Books, priced £11.99.

In Green New Worlds, we are invited to tap into Science Fiction and Fantasy to find out more about how sustainability plays a huge part in everyday life. The time is now to gather your information wherever you may find it!

Green New Worlds: A Quick Guide to Sustainability Through Science Fiction and Fantasy

By Ricardo Victoria-Uribe & Martha Elba González-Alcaraz

Published by Luna Press

The Only Constant in Life Is Change: Climate Change

If you think about it, the Long Night as described in A Song of Ice and Fire (Martin et al., 2014) should be an ecological nightmare within the story. But from the point of view of ecosystems and life on the planet, a decades-long winter coupled with constant darkness shouldn’t have left much in terms of living beings. Under the conditions of the Long Night, the margin for life to continue as we know it would be minimal, if not non-existent. In total darkness, there would be no photosynthesis, which means no plants and no crops, so a farmer already struggling to grow food in cold weather would be in serious trouble. And without vegetation, the food chain would break, as animal species that feed on plants would starve, followed by their predators, the bacteria that decompose the leftovers, and so on. Also, no insects. Really, if you think about it, it was a miracle that some hero survived long enough to stop the Long Night.

Those conditions are what Earth would experience if it was suddenly sent to Pluto’s orbit.

Now, this is an extreme example, using the exaggeration in magnitude that fantasy allows to drive a point. But the idea of seasons being thrown out of balance is not something far-fetched. It is something real, something that could and is happening right now, and something that, while it has been a part of Earth’s cycles, we as a civilisation have made worse. Yes, we are talking about climate change (also known as global warming, although we prefer the former term).

Climate change is real, there is no denying that. Despite what some ‘news’ outlets might have led you to think, 99% of the scientific community agrees that there is a problem with the global climate (Lynas et al., 2021).

Yes, we can hear the climate deniers from the back rows. There is always one in each semester of the Sustainability lectures. They either deny that there is a problem or deny that it is the fault of humans, and that the planet has always had climate change. But if you have paid attention to how much warmer or rainier your city has been in the last few years, how birds arrive at different times than before, or how some trees and flowers bloom in the off-season, you can see the effects of climate change in action.

While it is true that Earth has undergone cyclical climatic changes—the last one recorded being the Little Ice Age which was a series of harsh winters with mild summers between them, affecting mostly Europe and North America between the 14th and 19th centuries (Barbuzano, 2019), and the more memorable being the actual Ice Age from 115,000 years ago that lasted until 11,500 years ago—human activity has made it worse and more extreme in the last one hundred and twenty years.

Think of it like this: climate is a finely-tuned engine, like the warp core of the Enterprise. Like this core, the climate is regulated by a series of variables that create the weather system as we know it. Some variables are solar activity, the amount of salt or sweet water in the oceans at a given time, and the thickness of the atmosphere (a result of both the gases and the particles that compose it and/or are thrown into it by volcanoes or our transportation systems). And this finely-tuned engine work in cycles. Sometimes the planet gets warm, sometimes it gets cold. When it gets to an extreme of either option, it is because of an unexpected event, like a volcanic eruption, or a particularly active period of solar activity. And it is usually a regional thing, rather than global.

This is not a new scenario; this kind of side effect of climate change has happened before. There is something called the ‘Medieval Warm Period’, a period of unusual temperature increases between 750 and 1350 A.D. (Fagan, 2010). While in Northern Europe, the warmer temperatures allowed for increased food production (and in the long run allowed for the Renaissance), a widely accepted theory indicated that the Mayan civilisation of the Classic Mayan period collapsed due to intense droughts that disrupted their food supply lines at the same time. These droughts affected North America as well, impacting Native American settlements, forcing cultural changes, creating health problems, disrupting trade, and forcing migration. And in China and parts of Southeast Asia, monsoons of increased potency unleashed floods. These are just a few examples of what a natural cycle of climate variation can cause on human civilisations. But what if something was to alter climate patterns in such a way that could cause greater devastation, such as the Long Night does in Westeros? Not something magical, like the Others, but something closer to home.

Then, there is us. That’s where we enter the picture.

Green New Worlds: A Quick Guide to Sustainability Through Science Fiction and Fantasy by Ricardo Victoria-Uribe & Martha Elba González-Alcaraz is published by Luna Press, priced £6.99.

When a young woman is found drowned in Yokohama Harbour under suspicious circumstances, downtrodden Korean eel salesboy Han compels the eccentric Glaswegian artist Archie Nith to seek the truth. Discover more in this extract from the thrilling The Hotel Hokusai.

The Hotel Hokusai

By T. Y. Garner

Published by Ringwood Publishing

My sister, Yoona, used to have an old doll made of straw that our mother had made with bindings to separate the various body parts. The straw was noosed tight into a tiny neck, and after a long, thin face with watermelon seeds sewn on for eyes, it was bound again near the top, leaving an inch or two of straw bunching out so the hairstyle resembled the fruit of the gardenia. Because we called that fruit chija, this became the doll’s name, and like a plant she managed without a nose, mouth or any clothes. Soon after the Reverend Hare came among us, he found Chija lying on the floor of the room where we all three then slept.

Through the doorway I watched him ‒ it was a fascination for me, watching him when he didn’t know he was being watched ‒ as he picked her up and examined her. He turned her over and even smoothed the strands of straw that passed for her hair. He was smiling to himself, and I proudly thought it was at the care and skill with which the doll had been fashioned by my mother. Years later ‒ perhaps a year before I was put on the ship – another incident made me remember this first one and see it in a new light.

We were playing. Or I was not playing, I was too old for that. But it was a wet afternoon and I was keeping Yoona entertained by the elementary game of hiding Chija, who had long since been surpassed by a proper doll which the Reverend had brought back from a rare trip to the capital. This was a smooth-cheeked, glass-eyed creature in a lace dress, human enough to be baptised with the Reverend’s approval. Susan reigned supreme at my sister’s bedside, but Chija, who could be stuffed anywhere and contorted into various positions, still had her uses. Having exhausted the hiding places in the house, I decided to take her outside and place her at a corner of the window, hiding ‘in plain sight’. While Yoona closed her eyes and counted, I opened the front door silently and ran round the side of our wooden dwelling ‒ straight into our Protector and Benefactor. I backed away, clutching the doll tight to my chest, and began stumbling out some explanation as to why I had not been studying.

‘Ah-ah,’ the Reverend held up his hand. ‘Excuses do not excuse.’ This was one of his favourite admonitions in the classroom, but when he said it he was never truly angry, and I could see from his faint smile that this was the case now.

‘You are off to perform some voodoo, I suppose?’

I must have looked confused, because he bared his teeth and plucked Chija out of my hands. ‘This,’ he said, holding her up by the ragged bunch of stalks on her scalp, ‘reminds me of the brrranch of witchcraft known as voodoo.’

I knew something of witches and witchcraft ‒ he had told us before how in his country, many years ago, people used to believe that certain women worked with the devil, they were accused of being witches and burned at the stake. The accusations were false, he said, there was no such thing as witchcraft, although there were undoubtedly women who believed in it.

‘Voodoo, Sir?’

‘It is a practice of certain Caribbean islands, on the other side of the world from here.’

‘How does it work?’

‘One makes a model of one’s enemy ‒ usually a crude doll such as this,’ he waggled Chija in my face. ‘Then … Let me see …’ He dug in the pocket of his blue waistcoat and extracted one of the sharp little wooden sticks he was always fashioning to poke food out from between the wreckage of his teeth. ‘But anything sharp will do. Now, you have to focus on the face of your enemy, and say what is it that you want to happen to them … perhaps warts on the face or a rash on the stomach, or braining by coconut. Then, jab in the requisite place.’ He stabbed his toothpick into Chija’s stomach. I flinched and he laughed.

‘Don’t look so alarmed, boy, it’s all prrrimitive superstition and nonsense!’

I lay awake in the dark that night, a few feet from my sister’s sleeping form, remembering the first time I had seen him looking at Chija. So, it had nothing to do with love and admiration, I thought – only amusement at our primitive state. He was our minister and teacher and, as mother always reminded us, the father we never had before. The thought that there was something about him I did not like was dangerous. I knew this, but in spite of it I found myself fantasising about making a Reverend Hare doll, and sticking sharp sticks into it, especially the thing that dangled between his legs. I wanted this appendage to burst into flaming warts, dry into a hard crust, and then break into flakes like a piece of wood on the fire. It was to punish him for the noises he and my mother made at night, on the other side of the thin wall when they thought I was asleep.

The Hotel Hokusai by T. Y. Garner is published by Ringwood Publishing, priced £9.99.

Perched on a beautiful Scottish island measuring just two miles across, Café Canna is one of the remotest restaurants in Britain. But it is worth the travel time where it is justly famous for its sensational seafood. And now you can recreate their culinary magic in your own home!

Cafe Canna: Recipes from a Hebridean Island

By Gareth Cole

Published by Birlinn Ltd

Langoustine and smoked haddock pie

Everybody loves a fish pie! This is our version.

We pared it down to our favourite parts of the filling – the smoked haddock and the prawns (and replaced these with plump local langoustine). We have a smokery nearby that does incredible peat-smoked fish – their haddock is gorgeous.

It’s optional, but if you’ve read the rest of this book you’ll know that we believe in a pie that has pastry sides and bottom. And we see no reason why fish pies shouldn’t either. You can make the pastry and the stock the day before.

Makes 5–6 pies

(our tins measure 11.5 x 3.5cm)

For the pastry

290g soft butter

650g plain flour

½ tsp salt

130ml water

For the mash

1kg floury potatoes

(e.g. Maris Piper or

King Edward)

50g butter

25ml milk

For the stock

langoustine shells

(left from the filling)

½ onion (leave skin on and

no need to chop)

1 celery stick, roughly

chopped

1 carrot, roughly chopped

(no need to peel)

1 tbsp tomato puree

1 bay leaf

For the filling

50g butter

50g plain flour

500ml langoustine stock

100ml white wine

small bunch of parsley

200ml double cream

2 anchovies, finely chopped

250g fresh haddock in large

bite-size chunks

250g smoked haddock in

large bite-size chunks

salt and freshly ground black

pepper

1–1.2kg whole langoustine

To make the pastry, in a food mixer (or with your hands) combine the butter, flour and salt. If the butter is not easily malleable, microwave for 20 seconds at a time until it is. If it melts completely, the recipe will work just fine. Mix until very rough breadcrumbs have formed – if using your hands, rub the flour into the butter between thumb and fingers.

Pour in half the water and continue to mix, then add the rest. At this point it should have come together into a robust dough that would hold its shape if cut in half. If too wet, add more flour and mix; if too dry, a touch more water.

Remove from the bowl/machine and knead for a minute or two on a clean surface. Once it has come together into a smooth ball, you can use it directly, but it is preferable to wrap it in cling film and place it in the fridge for 30 minutes to an hour (or up to two days). If the dough becomes too hard when cold, microwave it quickly before use.

Next, create the mash. Peel and cut the potatoes into chunks, then boil them until soft but not falling apart. Whilst cooking, heat the butter and milk. Drain the potatoes and either pass them through a ricer (this is best) or mash them – then add the heated butter/milk and mix thoroughly.

Cook the langoustine in boiling water and peel (see p. 94, for step-by-step instructions), reserving one whole for each pie for garnish.

Use the water they were cooked in, as well as the shells, to make the stock. Place the langoustine shells in a pan and just covering with the reserved water. Add the other stock ingredients and simmer for an hour, then strain.

To make the filling, melt the butter in a large pan, then stir in the flour and continue to cook for 2–3 minutes. Gradually stir in the stock, then add the wine and finely chopped stalks of the parsley. Simmer for 20 minutes. Remove from the heat and add the cream, chopped parsley leaves, anchovies, haddock and seasoning. Reserve the langoustine for the next step.

To assemble the pie, line the pie tins with greaseproof paper and pastry in exactly the same way as the beef pie (see p. 178). As these pies will have a mash rather than a pastry top, neatly cut around the top of the tin for a smooth, circular top.

Half fill each with the fish mixture, then divide the langoustine between the pies, laying more fish sauce on top.

Heap a pile of mash on top of each pie, going right to the edge. Optionally, create a hole down through the middle of the pie and place a reserved langoustine in it, so that it appears to be bursting out of the top.

Bake for 30–40 minutes until the mash is starting to go golden. Serve with a simple side of veg.

Cafe Canna: Recipes from a Hebridean Island by Gareth Cole is published by Birlinn Ltd, priced £25.00.

What goes on behind closed doors? Well, writer Leslie Hills has given us a glimpse of the lives behind one door in particular in Scotland Street in Edinburgh. With so many fascinating life stories to discover, BfS spoke to Leslie to find out more.

10 Scotland Street

By Leslie Hills

Published by Scotland Street Press

Hi Leslie, congratulations on the publication of 10 Scotland Street. Can you tell us a little bit about what can readers expect from the book?

10 Scotland Street is the story of one Edinburgh home and its inhabitants and widespread connections over two centuries, tracing this city and the nation’s history and its global connections – to the Caribbean, Irkutsk, Calcutta, Sydney through the people who have lived in and passed through the doors of 10 Scotland Street. There are booksellers, missionaries, silk merchants, sailors, preachers, politicians, cholera – and, sometimes bizarre, coincidence. It’s in places personal and I am told fast-paced and funny.

This book is a true labour of love decades in the making, one which, in your introduction, you rightly note ‘won’t ever be finished’. What made you want to turn it into a book now?

My research started really by chance, and became an ongoing pleasure, not to say, obsession. One morning, looking over the North Sea, I told by my old friend Val McDermid about the stories I had unearthed, and she said I should write a book. This was a long time ago. I have a life, work and family. But then came the Covid19 lockdown. There were a series of blank afternoons in my diary, and so I approached the boxes of papers and the innumerable computer files marked Whytt. With some trepidation.

By studying the lives of those who previously lived at 10 Scotland Street, you are taken from Edinburgh to the Caribbean to India and beyond, even into the world of publishing. If you could meet one former owner today, who would it be and why?

As you say, there are many fascinating characters – Admirals, missionaries, a notorious beauty, politicians and men of affairs to name a few, who take us into sundry backrooms and across the globe. Their lives are recorded through their professions and trades and in the official records. In newspapers, petitions, proclamations etc they are named and praised or excoriated. In the case of most women, they appear only in the birth, marriage, death and census records. I discovered so much about the men of the family Whytt who owned the house, from its first occupation, for one hundred years. I know much less of the women and their lives. I should like to meet Ann Henderson, wife to David Kedie Whytt, who was the first woman to measure with her eyes my windows for curtains and to hold the key I use to close my cupboard door. I should like to hear her tell of her concerns as she steered her family through war, economic depression, the death of children, civil disruption in her town – and all the other, no doubt surprising, events and preoccupations she would undoubtedly reveal to me.

The domestic world as a microcosm of a society in transition is an idea with a rich tradition in English literature, stretching back to Jane Austen, whose work was published around the time the Edinburgh New Town was first built. Did you draw influence from any particular authors during the writing process?

Jane Austen of course. I read Medieval People by Eileen Power a long time ago and several times since. It’s extraordinary, as is Hilary Mantel’s A Place of Greater Safety. I read it on publication and immediately went out and bought copies for my offspring. I have a grandson named Camille. And of course, Virginia Woolf. I have always admired Cecil Woodham Smith’s The Reason Why which follows two officers into the charge of the Light Brigade to eviscerate the Victorian Class system. It’s flawed and biased and brilliant. I recently read Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos which uses the personal to explore the momentous events in Berlin, in the years spanning the end of the German Democratic Republic. I lived in West Berlin for much of that time and her perspective from the East was fascinating.

Your book comes at a time when people are taking a keen interest in the human histories of houses, with Diarmid Mogg’s Tenement Town project especially coming to mind. Do we as a country take a particular fascination in older buildings, and if so, why do you think that is?

I think it’s more about the people than the buildings. There has been a decided shift from history as royalty, generals and ‘heroes’, towards the lives of the people who lived below the radar. Perhaps this is because so many of the former have been found to have at least one foot of clay. I’d also cite the greater ease with which we may now discover, through resources such as newspaper and other archives, the lives of ‘ordinary‘ people. So many were anything but. And then of course there is the enormous ubiquitous interest in family history – which has the potential of aiding receptive professional historians in many ways.

Were there any discoveries during your research that shocked you?

Yes. There is a whole chapter about David’s brother, William Whyte, born 1772, who lived a long, philanthropic, generous, sometimes surprising life. He was personally involved in the care of the poor and destitute, and active in various anti-slavery organisations. I had decided, after being in his company for several decades, that he was a good man. And then I found him on the lists of owners who had received compensation when people who had been enslaved were emancipated. Yes, I was shocked. And then I discovered that it was in fact as a result of his care for family. His sister, Grace and her husband, Admiral Gourley, had five daughters, three of whom married perhaps unwisely. William helped them and their families financially. Two sisters married plantation owners on the island of Nevis. They struck hard times when the price of sugar plummeted. William took over their debts and in so doing became a mortgagee of their plantation. But, despite his reasons, I’m still shocked. The story of 10 Scotland Street, Edinburgh and Scotland stretches round the world and is sewn through with such tales and the spirit of Empire.

Lastly, if you ever did have to move, where would you go and why?

Glasgow. I grew up there and came to Edinburgh when I was twenty-one for two years which have stretched to more than five decades. Glasgow has changed enormously but is such a lively, complicated city where I am immediately at home. And access is considerably easier to the western Highlands and Islands, and in particular to the island of Bute, with which I have had ties since before I was born.

10 Scotland Street by Leslie Hills is published by Scotland Street Press, priced £24.99.

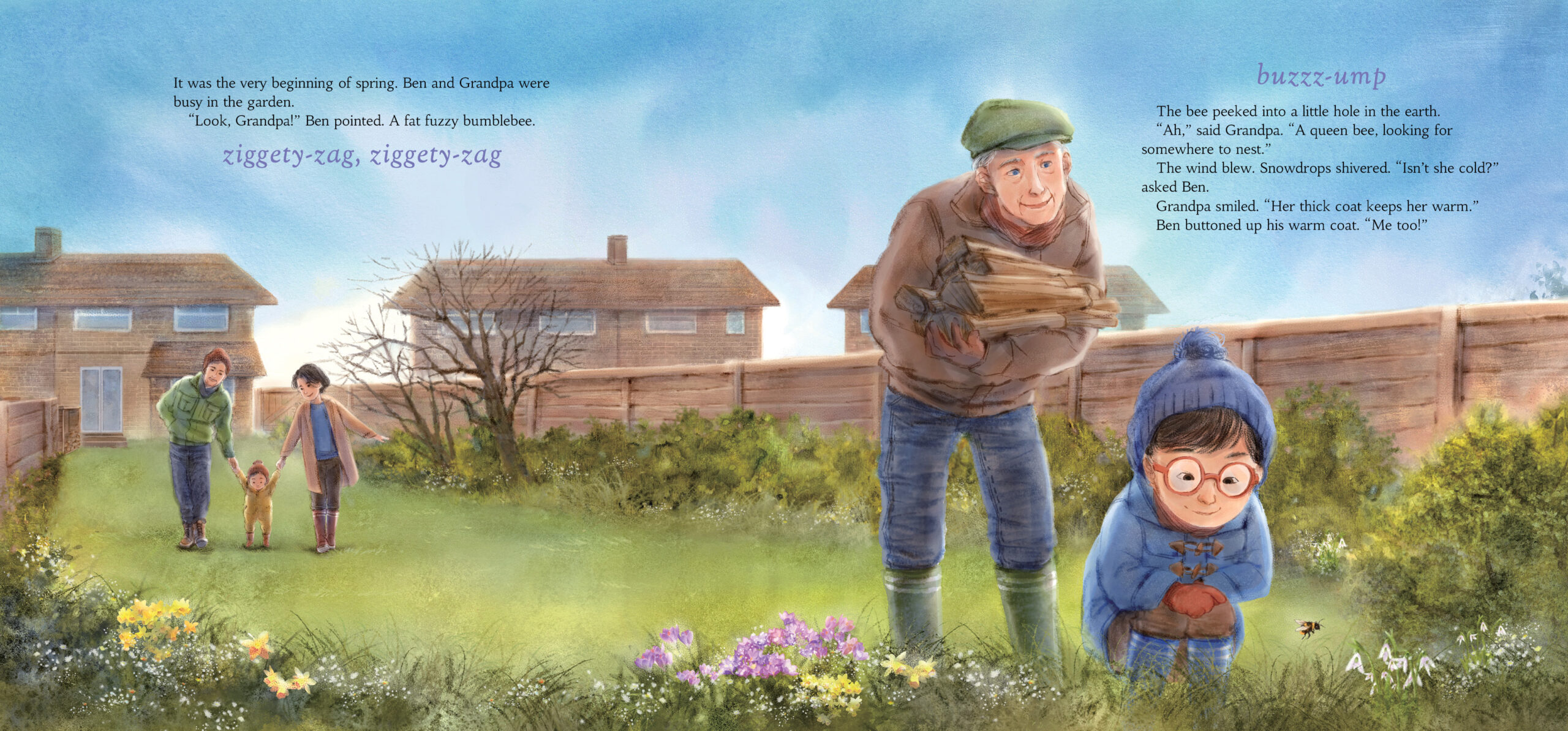

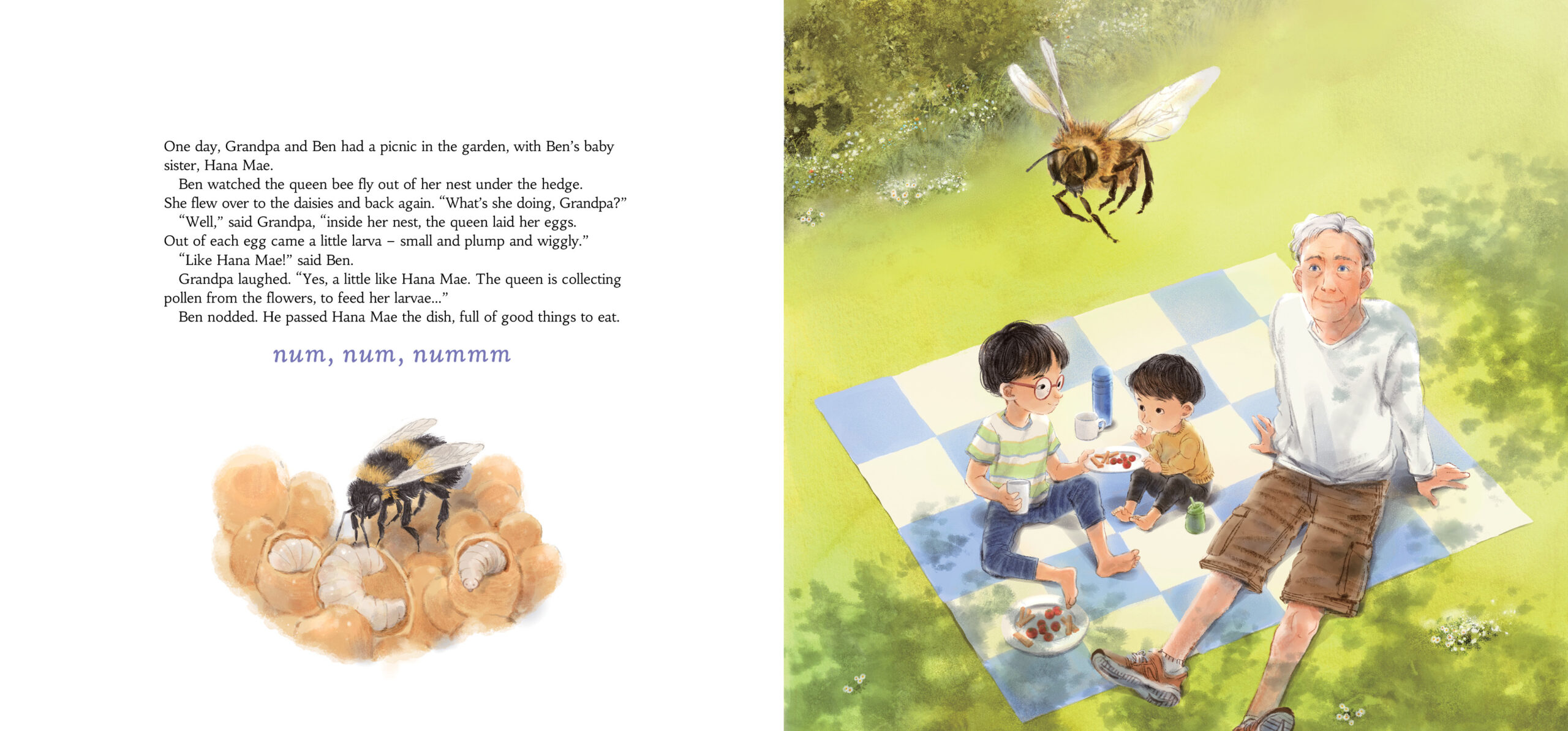

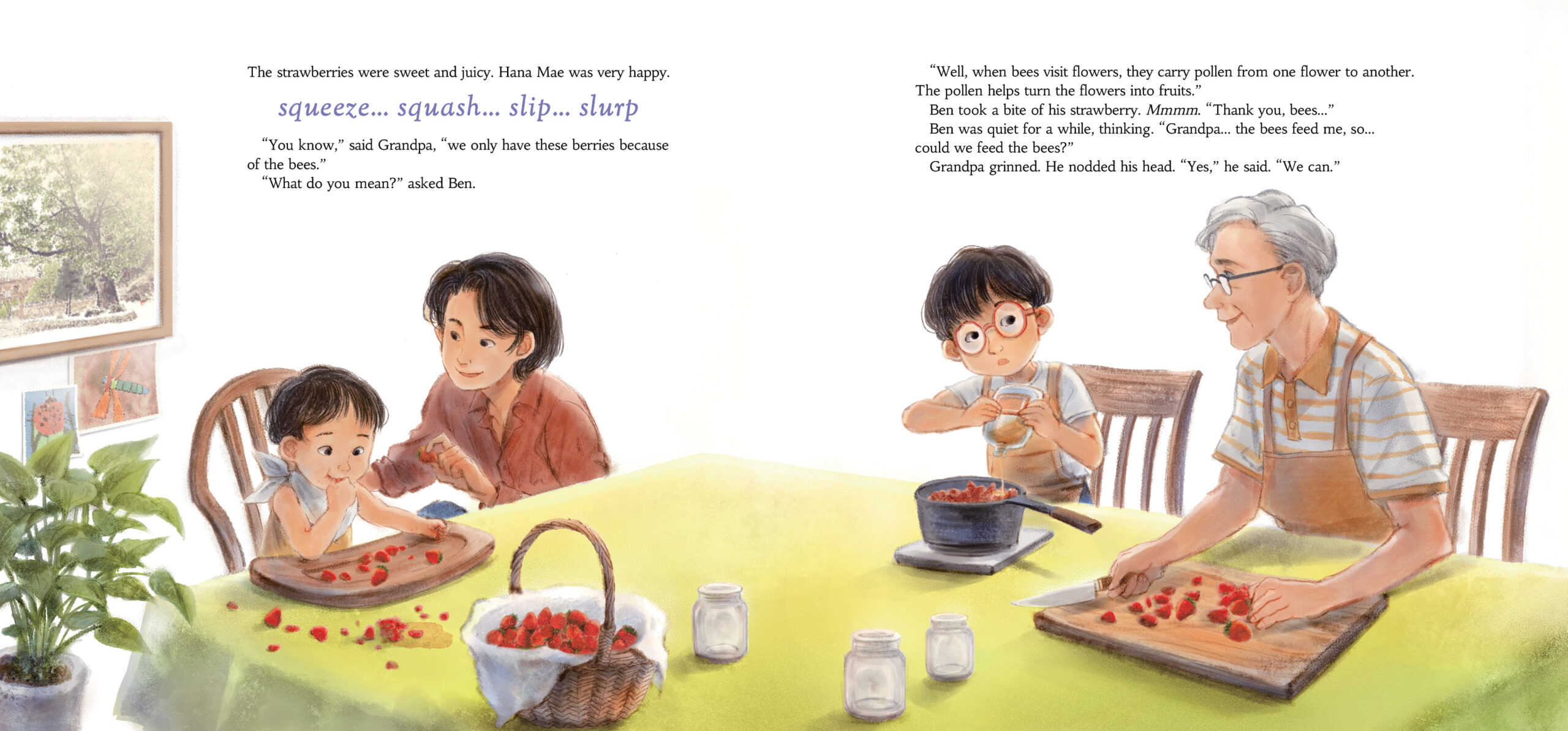

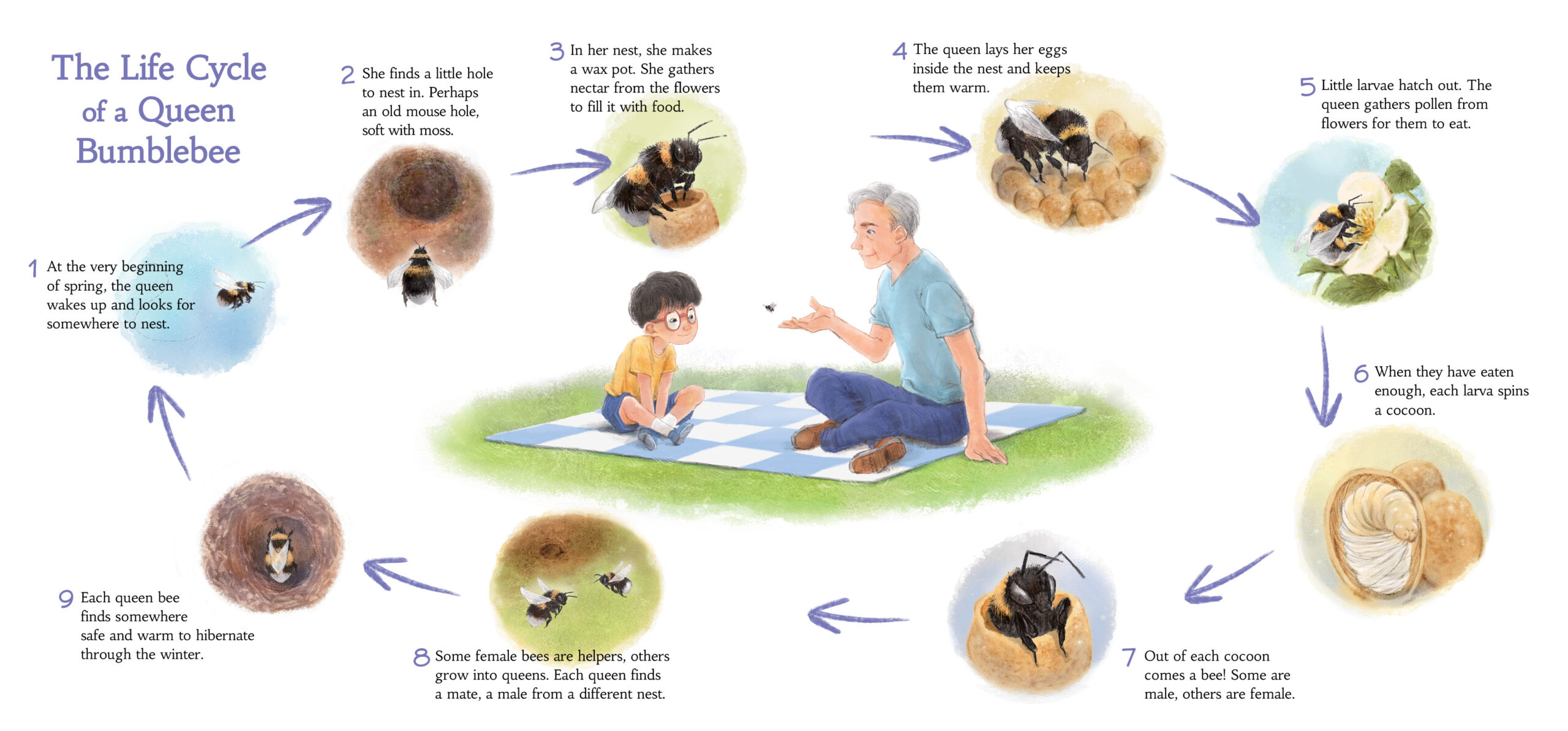

The Bumblebee Garden is a charming new picture book from award-winning British author Dawn Casey and renowned Korean illustrator Stella Lim which follows young Ben as he helps in Grandpa’s garden through the year, learning all about the life cycle of bumblebees in the process. The lyrical story and luminous illustrations come together to highlight the importance of bee conservation and open the world of the bumblebee to young children. We spoke to Dawn and Stella about inspiration, their creative processes and the challenges of telling an appealing yet accurate bee story. They were even kind enough to offer a little advice for anyone looking to make a new beginning in writing or illustrating in 2024!

The Bumblebee Garden

By Dawn Casey, illustrated by Stella Lim

Published by Floris Books

Dawn Casey, Author

What inspired you to write The Bumblebee Garden?

Years ago, my enjoyment of the gifts of the honeybee (gloopy honey and golden candlelight!) first fostered my gratitude for bees. Later, I realised what a vital role bees of many kinds play in creating the food we eat. Wild bees need help right now, and there are things we can do to help that are simple and easy.

I chose to write about the bumblebee in particular because it’s a bee we all know – a familiar friend. I wonder if, perhaps, humans (as mammals) naturally feel a special sense of affection for small furry creatures, like the chubby fuzzy bumblebee.

Why is it important to open a dialogue with young children about bees?

Actually, I see it the other way around! In my experience, young children are instinctively connected with the natural world. Being small themselves, they especially relate to other small beings – they greet snails and befriend bugs. I remember when I was a girl, lying under my garden hedge, talking to a woolly caterpillar. And when my daughter was little, if she ever found a dead bumblebee, she created a resting place for it, circling it with flowers. No one told her to honour the bee, she just knew it felt the right thing to do. So, perhaps, being with children can help us adults to remember that innate wisdom, to inspire our own actions.

Were you already familiar with the world of bees or did the book represent a journey of learning and discovery for you too?

I very much enjoyed learning about the life of the bumblebee! I’m especially grateful to Alan Stewart, Professor of Ecology at the University of Sussex and convenor of the Royal Entomological Society’s Insect Conservation Special Interest Group, who generously gave his time and shared his expertise to double-check my own findings.

The book does very well at presenting factual information without feeling ‘educational’ in tone. Was it challenging to strike this balance?

In some instances, yes. I value clarity and my intention was to keep it simple. And I also value truth and authenticity, and enjoy the treasure-hunt of researching, exploring, discovering…

One thing I found helpful in integrating these different elements in the story was speaking the words aloud. I often tell my tales orally, without the written text. It helps me hear and feel how the words roll off the tongue, to keep the language clear.

I was aware too of the unconscious paradigms that can be perpetuated in the language we use. For example, though ‘worker bees’ is the ‘correct’ scientific term, it uses the language of economic systems as a frame for understanding the natural world. I chose to use the word ‘sisters’ instead, which is still true, yet expresses the idea that nature is a family – an idea I believe better serves us, and all life.

What advice would you give budding authors looking to write their own picture books?

- Write what’s true for you – the things you care deeply about.

- Hone your skills – there are many wonderful ways to learn from more experienced authors, for example at a writing retreat.

- Learn the standard form of the picture book – typical wordcount, number of pages etc. Consider how words and pictures work together – sometimes, pictures can tell the story better than words.

- Look at rejections as stepping stones upon your journey onwards and upwards.

- Believe in yourself!

Stella Lim, Illustrator

Why did illustrating this story appeal to you?

I always look for a story in which I can explore a new world or a different life to mine! I love bumblebees, but I didn’t know much about them, so I thought it would be a great chance to get to know their hidden life and unique ecosystem. Also, the story is written by Dawn Casey, who I worked with on Spin a Scarf of Sunshine! I always hoped to be able to work with Dawn again, and when the chance arose, I was delighted.

What’s your favourite illustration from the book and why?

I love all of them! One of my favourites is the illustration where Grandpa, Ben and Hana Mae are relaxing in the back garden. I enjoyed drawing all the details of a bumblebee flying above them in this illustration. The illustration of the kitchen with Grandpa, Ben, Hana Mae and mum is another favourite. This illustration is full of warmth and it always makes me smile seeing Hana Mae messily enjoying the strawberries.

Was the visual setting of the book inspired by any real gardens, or is it totally imagined?

Both! I used to visit a neighbour’s house when I was in the UK, and there were many beautiful plants and flowers in their garden in the summer. Remembering their garden helped me to draw the outline of Grandpa’s garden. I also researched a lot of images of British gardens and mixed my experiences and these images together in the illustrations I created.

Was it challenging to depict all the various stages of a bumblebee’s life cycle?

It was! It was necessary to research their various appearances and life stages to depict them precisely in this book. I bookmarked many videos which showed each of the bee growth phases and the life cycle of queen bees. I was not an expert on insects, but I tried to do my best to depict them accurately.

What advice would you give new illustrators looking to work on picture books?

First, go to the library and read a lot of books which were released recently! You can get a lot of inspiration and information about how much variety there is in picture books. You can learn about creating characters and a story, and about the book formats which publishers use. Then select the illustrations you are most proud of for your portfolio. Art directors are very busy and have limited time, so it’s great to highlight 4-10 pieces of art in your portfolio when you contact them.

You expressed joy at being asked to illustrate mixed-heritage families, how much did this help draw you into the project?

It helped a lot! I was so delighted that I could draw families from different multicultural backgrounds, especially Korea! I’ve illustrated five picture books to date, and I drew them all from my heart. However, having the chance to draw a Korean family was very special! It helped me to immerse myself in the characters much more vividly as if they were alive, and I have a great deal of affection for the book. I’m sure you will love The Bumblebee Garden too!

The Bumblebee Garden by Dawn Casey and Stella Lim publishes on 22 February 2024 in both paperback and hardback from Floris Books, priced £7.99 and £12.99. Available from all good bookshops, Bookshop.org or directly from the publisher here.

We at BooksfromScotland have been excited about the Poor Things film ever since we heard of its release, and it doesn’t disappoint. But, as ever, the novel from which it is adapted is a richer, warmer and braver experience. The fine folk at the Alasdair Gray Archive have put together a fantastic interactive guide to the novel on their website, which we urge you to visit. In the meantime, here’s an extract from this guide, written by Grace Richardson, taking a closer look at Bella Baxter.

Poor Things

By Alasdair Gray

Published by Bloomsbury

Extract by Grace Richardson

Bella Baxter: Gorgeous Monster Part One

Poor Things is overflowing with political debate, ethical negotiations, and discussions of social issues, all of which are overarched by the novel’s focus on gender politics. One of the poor things who is most often affected by these concerns is Bella Baxter. The novel, a satire on the politics and social dynamics of the Victorian era, foregrounds male desire that is in contention with the social and sexual liberation of women in the 19th century. It is a conflict embodied in ‘the woman question’, a debate which scrutinised the changing political and economic status of Victorian women and responded to their increasing demand for social and sexual autonomy. The novel’s multiple narratives mean that there is no singular truth presented, instead it is more important the reader understands the world of Poor Things as being filled with discourses and ideas that all claim to be right. Once we understand this, the reader is offered a fascinating insight into how patriarchal power seeks to undermine female autonomy, as well as how one woman (Bella Baxter) works against this. What will become increasingly clear is that despite the various male characters’ attempts to control and confine Bella, she censors neither her behaviour nor her actions.

One way to explore the gender politics that shape Bella’s experience is to focus on two key concepts of the novel –‘making’ and ‘scarring’ – which present themselves in different ways throughout the heroine’s narrative. Both concepts help us understand how Bella imprints herself on others and is, herself, imprinted on by those she encounters.

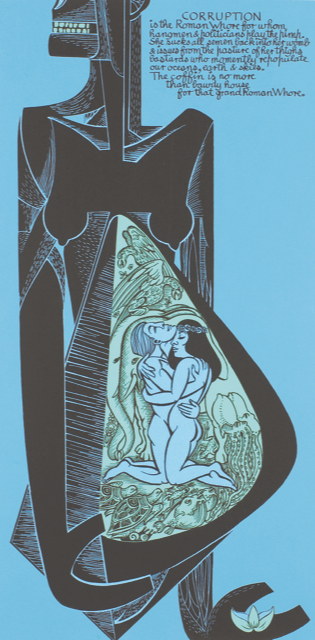

Poor Things (1992), courtesy AGA

Poor Things is a novel about making, more specifically, the making of a woman. In McCandless’ Episodes, we are introduced to the novel’s key protagonists through chapters entitled ‘Making Me’, ‘Making Godwin Baxter’ and ‘Making Bella Baxter’. And since we are taking a gendered look at the novel, a question arises: what does “Making Bella Baxter” look like in relation to the society of 19th century Britain?

‘It seems that women who have not been wed by wedders like my Wedder all possess a slip of skin across the loving groove where Wedderburns poke their peninsula. The slip of a skin he never found on me. “And how do you explain the scar?” he asked, referring to a thin white line which starts among the curls above my loving groove and, like the Greenwich line of longitude, divides in two the belly of Solomon has somewhere likened to a heap of wheat. “Surely all women’s stomachs have that line.” “No, no!” says Wedder. “Only pregnant ones who’ve been cut open to let babies out”. “That must’ve been B.C.B.K”, I said, “the time Before they Cracked poor Bella’s Knob”. I let him feel that crack which rings my skull just underneath the hair’ (p107).

Through reading the quote above, it becomes evident that ‘Making Bella Baxter’ is inextricably linked with constructing her female body. McCandless’ narrative presents Bella Baxter as a surgical creation of Godwin Baxter. As McCandless’ story goes, after pulling an unknown female body from the River Clyde, Baxter revives the woman from her death by suicide and implants the brain of her unborn foetus into her skull. In a gender-inversion of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bella, the 25-year-old woman, is rebirthed through Baxter’s experiment. It becomes clear that ‘Making Bella Baxter’ into a proper Victorian woman was an impossibility as her bodily make up defies these norms. Bella is considered abnormal because despite her mental age, she is not a virgin, and her hymen is broken. She also makes childlike references in her letters to her hymen as ‘a slip of skin’ and her vulva as a ‘loving groove’, showing that although she has never been given the right vocabulary to describe her body, it has been unfairly treated and harmed at the hands of men.

Bella’s head and stomach are literally scarred by her ‘re-birth’. Bella’s scarring is not just literal, however. If we take the word ‘scar’ to mean ‘a lasting impression’ as well as a ‘wound’ or ‘mark’, then we can begin to take a closer look at how Bella imprints her mark, that is to say, her influence, on others.

Poor Things (1992), courtesy AGA

One way of achieving this is by examining Bella’s sexuality. Bella’s sexual autonomy leads the men of the novel to harbour emotive reactions toward her. If we are to believe McCandless’ version of events, her sexual needs and obsession with ‘wedding’ (sexual intercourse) in her past-life as Lady Victoria Blessington led her husband General Aubrey Blessington De La Pole to have her institutionalised. In an inversion of this plot point, the man she elopes with, Duncan Wedderburn, is committed to a Glasgow mental asylum after realising Bella views him chiefly as a sexual object. Although this is exactly how he has treated Bella and prior conquests in the past, Wedderburn is shocked that a woman has the capacity to dehumanize men in the pursuit of sexual pleasure: ‘I had never before heard of a man-loving middle class woman in her twenties who did NOT want marriage, especially to the man she eloped with’ (p81). The unorthodox sexual outlook of Bella (previously Victoria Blessington nee Hattersley) equally unsettles Blessington. For the General, the abuse of socially non-resistant women like his mistress, Dolly Perkins (whom he abandons pregnant), is a social norm. In contrast to Dolly, Bella is an example of the ‘New Woman’ (Buzwell, 2014). The 19th century term for an economically independent and spirited woman who exercises control over her life was popularised by Henry James (among others) in novels Daisy Miller (1978) and Portrait of a Lady (1881).

The portrait Gray paints of his leading lady in Poor Things is conflicting. Bella’s scar, for example, creates multiple different explanations. McCandless states that it is a result of the incision Godwin made while switching Bella’s brain, whilst Victoria states in her letter to posterity that it is the result of a beating by her father which left her unconscious at the age of five. Wedderburn labels it a “witch mark” or “the female equivalent of the mark of Cain, branding its owner as a lemur, vampire, succubus and thing unclean” (2002, p.89). For Wedderburn, Bella’s scar makes her a monster, marking her as a threat and something to be feared. It was not uncommon for witch hunts to take place in Scotland throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. Under the supervision of James VI’s royal commissions, at least 400 people were put on trial for witchcraft and diabolism during a 6 month campaign later known as The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1597. Of all the individuals accused of witchcraft in Scotland’s history, 85% were women (Toil and Trouble: Witchcraft in Scotland, The University of Aberdeen). To accuse Bella of having a ‘witch mark’ Wedderburn is stating his belief that Bella is a threat to the order of the state and needs to be persecuted. After all, as evidenced by The University of Aberdeen data, a witch hunt is essentially a women hunt; a means for the powerful to persecute the powerless.

Corruption is the Roman Whore (1965), courtesy AGA

Another form of gendered persecution evident in Poor Things can be explored through the male characters’ various attempts to assert their dominance over Bella. Near the beginning of the novel when Baxter and McCandless quarrel over the matter. McCandless states: ‘You think you are about to possess what men have hopelessly yearned for throughout the ages: the soul of an innocent, trusting, dependent child inside the opulent body of a radiantly lovely woman’ (p36). The sexualisation of Bella’s female body constitutes another form of persecution. McCandless admits that throughout time men have sought women for their bodies, even admitting that men would prefer a less developed child’s brain, rather than a fully developed adult’s brain. Although not admitted explicitly by either McCandless or Baxter, we can assume this preference is owing to the man’s greater ability to manipulate such women into fulfilling their sexual needs without question. This implication somewhat sullies Gray-the-Editor’s account of Baxter (explored in the ‘Godwin Baxter’ section of this guide) as an ‘astonishingly good, stout, intelligent, eccentric man’.

Despite the male characters’ attempts to control and censor Bella, her resistance to gendered persecution is shown in her refusal to conform to their demands. This often results in accusations of madness and female ‘monstrosity’, where Bella is defined as a ‘monster’ or ‘aberration’ (p89) for her refusal to abide by societal rules. To be a monstrous woman does not always mean that the woman is literally a monster or a creature. Nor does it necessarily correlate with physical unattractiveness. Bella’s appearance is presented in a wholly positive light. To McCandless, she is a ‘glorious dream’ who ‘shone before’ him ‘solid, tall, elegant’, like ‘a rainbow’s end’ (p44). Though a ‘monster’ to Wedderburn, she is still ‘gorgeous’ in his eyes (p91). Bella’s monstrosity denotes her transgressive, deviant nature as it appears to men through her behaviour. To be considered monstrous, the female must refuse or be unable to conform to the prescribed social conventions of her given time and culture. Her behaviour will thus be perceived as monstrous or unnatural (a condition Kirsten Stirling explores in Bella Caledonia: Scotland Deformed). By rejecting what is considered ‘normal’ and ‘natural’, the female monster questions the ideological and patriarchal constructions of what the female body and feminine behaviour should look like, whilst also revealing the underlying anxieties of a given society or historical period.

Poor Things by Alasdair Gray is published by Bloomsbury, priced £9.99.

This extract was written by Grace Richardson. Visit the Poor Things Guide at the Alasdair Gray Archive here.

Donald S Murray is fast becoming one of Scotland’s most interesting historical novelists. His latest, The Salt and the Flame, which explores the island diaspora, has already gained plaudits, and was named The Times Historical Fiction Book of the Month.

The Salt and the Flame

By Donald S Murray

Published by Saraband

Mairead looked down the length of Francis Street again, seeing some of the people there. One man, who was clearly not travelling on the Metagama, had a coil of rope looped around his shoulder; long enough, perhaps, to fasten and tie the vessel in the harbour from which it was due to sail. A woman was near the town hall. Trembling and tearful, she was being consoled by others, their fingers clasped around her back, tapping her shoulders again and again. It was the kind of scene she did not want her own family to indulge in, fearing that if they did, she might want to turn back to a village in which she could see no glimpse of the future, locked away in the past. ‘Tsk, tsk,’ she heard one of her comforters say. ‘He’ll be back some day. I’m sure of that.’ And the woman responding by saying, ‘My son! My son! There’s no chance of that ever happening. No chance at all.’

Mairead pretended not to hear her, not wanting to think of returning to South Dell, not even to see the cairn some of her fellow emigrants had added stones to on the shoreline of Loch Sgriachabhat the night before. This had been first created by people who’d left the island before, heading to the Eastern Townships in Quebec near the end of the previous century. She had been told, too, that a few of the men had also built a bon-fire high upon the shoreline, a long way from the beach at the mouth of the river on the northern edge of the community; doing this in the hope that those leaving would catch a small reminder of their homeland when the Metagama sailed past.

‘If the weather’s good, you’ll probably see it when the ship sails round the Butt of Lewis. A faint memory of home.’

Again, Mairead shook her head when she heard this. She had decided that the moment she stepped on board, she would not look back at the island again, avoiding even glimpsing its coastline if she could. Even if her head did turn accidentally, she was certain the sights she had mentioned would be clouded in a thousand different ways. The glow and flame of a bonfire would be obscured by rain or mist or the salt of tears that would always be in danger of blurring her vision. The cairn of stones rendered invisible by the wings and plumage of the seabirds that had discovered it beside the loch, perching there as if each ledge was a bough or branch. Gulls would sit perched on its crest; small birds – like spar-rows and starlings – landing on its layers. Perhaps, too, the terns nesting round nearby Loch Drollabhat would rise up, obscuring the coast with the swiftness of their flight.

It didn’t matter. She tried to shake all thought of the place from her head. MacQueen had been right that day in the pulpit. It wasn’t healthy to look back.

She kept all this tight within her head as she looked towards her parents one last time, taking in their every gesture and feature as if she feared it might slip from her in a short time. There was her father’s gaunt face, his skin ravaged by so many years working on moor and shore, the spit of rain that so often lashed his features when he laboured on his croft. Her mother was different, her hair still dark with only a glimmer or two of grey, her face soft and well-rounded, quivering as she sought to suppress the sadness that she felt. Mairead hugged them both, trying not to draw too close to them but keep a little distance away, to prevent herself from succumbing to the sadness she felt all around Stornoway that day.

And then there was her brother Murdo, his face as round as his mother’s, fair head the same shade as her own, bottom lip trembling. He had spoken more to her in the last week than he had done at any time since he came back from the war, babbling for ages about the family croft.

‘If you marry and have children, I’ll make sure your family gets the croft,’ he would say. ‘They can always come back here to live if things don’t work out for them away.’

‘And what about you? Won’t you have a family?’

He shivered the one occasion he answered that. ‘No chance of that.’

‘Why not?’

‘The war put me off all notion of that.’

She tried to question him about this, but he never responded, shrugging and walking away from her side.

He didn’t do that today. Instead, he held onto her tightly, ignoring her attempts to keep them apart. He could feel a sob ripple through his body, one that she immediately tried to stifle and suppress in her own.

‘Bye,’ he said. ‘Just remember the croft is waiting for your children. It’s theirs if they want.’

‘Yes … Yes … Yes … I’ll remember that.’

But she was already trying her best not to recall it, bringing all that she disliked about it to the forefront of her mind. The stink of peat within the house. The manure heap behind it. The smell of cow-dung she could frequently smell within it.

Bye,’ she said. ‘Bye … Bye.’

And then she was away, straight down to Number One Quay, where the Metagama was waiting a short distance out of the harbour, not looking in any direction but in front of her, passing the town hall, the criss-cross of roads and streets that were barely familiar to her, since she had rarely gone to Stornoway before. A short time later, she joined the queue for the filling of forms, her medical inspection; her eyes clamped, too, on the back of the head of Finlay, a Ness man a few years older than her sixteen years of age. He stood just before her. She noted his wave of black hair, the slimness of his frame, ignoring the words of other Lewismen who stood behind and in front of her, aware that, with the advent of nerves and fears at the prospect of the voyage, she might be unable to speak to them, her knowledge of both Gaelic and English slipping from mind and tongue.

The Salt and the Flame by Donald S Murray published by Saraband, priced £9.99.

Time to celebrate Robert Burns! And what better way than with Sleekit, a brilliant poetry collection from many of our best contemporary poets writing in the Burns stanza. We’ve picked a few highlights for you to enjoy.

Sleekit: Contemporary Poems in the Burns Stanza

Edited by Lou Selfridge

Published by Tapsalteerie

Ode tae a Tunnock’s Teacake – Gill Shaw

ah eye up thon wee gildit temptress

ken soon she’ll let me help her undress –

peel aff her skirt wi practiced finesse

while ah birl her roon

they chocolate curves call oot fur caress

let ma fingers scoon

ah’ll cradle her sae she’s suspendit

then flip her ower sae she’s upendit

an dae whit ah ken she indendit

bite her biscuit aff

ah’ll dip ma tongue in – she’ll taste splendit

sweet an sticky, saft

ah’ll gulp the rest doon in a wunner.

gie up silent prayers tae Tunnock’s

but wi her gone ah’ll nae be scunnered

caucht up in ma thochts

while it’s true that she wis a stunner

ir’s five mair in the box

Ma Scotland Is – Jeda Pearl

whorls o snowdrops refusin tae mope

bluebells convenin unner th oak

a glimmer o fawns wi thair kinfolk

fine legs o birch

sleekit smirr that gies ye a guid soak

willow, like church

low sky gatherin clouds in thair flocks

sparrows squabblin, a cauldron o hawks

starlings swell granite in paradox

larynxes strum

goldhammers – prophets o equinox

wingfuls o sun

bladderlocks n deid man’s bootlaces

microcosmic rock pool embraces

coastal melodies – shoreline graces

ripe mussels thieft

gulls screekin, swaddlin wind displaces

salted grief

aye

auld coal cellars wi daddy-long-legs

clamberin tenements, skylight webs

duckin washin lines, hide in hedges

backgreen escapes

skitin doon th hillside oan yer sledge

hail bites, high stakes

tim’rous recitals o cherished Burns

does this poetry deserve ma tongue

sweetened wi cane sugar companion

how we enlighten

imagine oor Rabbie campaignin

for reparations

Scottish surnames across Jamaica

both bonnie lands o wood n water

inherited by twin isles’ daughter

witches, mystics

when wi gaun mak equalisation?

optimistic

plenty still reek monies, palms bluid greased

excessive atrocities bequeathed

say yer frae here – thay dinnae believe

brave Caledonia

isnae racist so hud yer truth – wheesht

fearless nation

aye, aw that

but it’s

sweepin hills o mauve-turnin heather

gilt-tongued gorse hostin May Day blethers

candied clovers in leesome weather

nettle sent’nels

purple thistles burstin wi feathers

at summer’s close

thick cloaks o haar tae hush dour mornin’s

lang yairns n fowktales tae courie-in

wry maids o mist, dirges for yearnin

feisty insults

skimmerin wirds soundin oot meanin

land o poets

taps aff for a fleetin wing o sun

endless ceilidhin while th night’s young

myndin oor histrae tae mend, atone

skouth, aye enough

reclaimin courage – fearless nation

heavin wi love

Robert Burns in Scottish Stanza – Janette Ayachi

A diet of women, wine & song

What could possibly go so wrong

This is the place where I belong

& I love it

It bulks me up & makes me strong

Fuels me with grit.

I speak in stardust, incantations

I dress in silk & selkie skins

& I confess all my near sins

To the whole world

Where I end & where I begin

Is one big swirl.

Baritone of my bones sing heavy

Beneath the belly of my bevvy

I reach for life that feels fleshy

So I can sleep

Legend & myth just like Nessie

Into the deep.

With romance, friendship, food & drink

One is always allowed to think

Most things to music we can link

Words to lyric

This is how we stop the near sink

It’s generic.

From couch to ceilidh, up you get!

No rest from the workers sore head

It won’t be long before we’re dead

Let’s celebrate

With throats open wide to be fed

If that’s our fate.

My role, I speak for my people

Escape societal shackle

Make folk laugh, bellow & cackle

Like the stars say

I’m Aquarius, I mingle

In lots of ways.

Most mornings I work the farmland

It’s my duty to give a hand

But my health is taken like quicksand

The elements

Rake their toll against all I planned

In settlement.

I am restrained from who I love

So breed as wide as a turtle dove

Migrating to fields from above

I know these roads

Journeys that give the words a shove

Like breath, they flow.

Hemlock, porcelain & then smash

I weary myself back from crash

Marry my love under lightning flash

Father unleashed

Allowed now to follow my stash

For all such peace.

Kids & animals catch my heart

I’ve always known this from the start

Losing my daughter, the worst mark

Death has ingrained

After this stopped the morning lark

I live in pain.

Seasons come fierce, I watch from my room

Try not to let myself hug gloom

My tooth is removed more ache looms

So much is lost

I crawl to my horse left ungroomed

Dip into frost.

I trust my friend, dear physician

Wide cabinet of medicines

Each one a trick from the magician

Ripe sorcery

To sip with my broth of venison

Soon I’ll be free.

I drink from the well, dip in the sea

But want to stay in bed with whisky

The delirium knocks my family

All to the still

Too late now for my recovery

I’ve had my fill.

Chronic illness & infection

My heart’s walls go up in correction

The water too cold to section

Any more time here

Live fast, die young; a quick reflection

Nothing to fear.

I’ve left my brood my legacy

Many women mourning after me

It’s no wonder I’m not left in peace

Long after rot

To unravel any mystery

Least not forgot.

I live on, I play on the souls

Of many from where heather grows

& beyond as life does unfold

Each year I’m sung

On my birthday I rise & roll

Kiss winter sun.

Sleekit: Contemporary Poems in the Burns Stanza edited by Lou Selfridge is published by Tapsalteerie, priced £10.00.

David Robinson is, as ever, thoroughly impressed by Louise Welsh as she confounds genre expectations in her latest novel, To The Dogs.

To The Dogs

By Louise Welsh

Published by Canongate

‘It’s only January, but the bar for this year’s McIlvanney Prize is intimidatingly high already.’ That’s how I signed off my review of Louise Welsh’s The Second Cut two years ago, and as long as she keeps writing classy novels that can be vaguely categorised as crime and as long as Canongate keep bringing them out in January, there’s always going to be a danger of me repeating myself.

That’s something Welsh herself seldom does. Not for her the well-trodden ways of so much crime fiction: body found, coroner called, clues discovered, and case solved by a troubled detective who is ultimately proven wise. Indeed, her new novel, To the Dogs, doesn’t have a single one of those ingredients, even though it does manage to include a very suspicious death and a no shortage of crimes.

Just to prove how Welsh can’t see a crime novel cliché without wanting to dismember it, look at who she chooses for her main protagonist. Professor James Brennan FRSE FRSS is a university vice-principal who has stood in twice for his boss on trips to the Far East in the past month alone, and is hot favourite for the top job. If you know anything about what that would entail, you’ll realise that running an organisation with 8,000 staff and 30,000 students from 140 countries doesn’t leave much time for spare-time crime-solving. (Those figures are from Glasgow University, where Professor Louise Welsh teaches creative writing, and even though Glasgow is never mentioned in To the Dogs, the Gilmorehill campus’s iconic Gilbert Scott Building is on its cover).

Of course, there’s absolutely no reason why a top-flight academic can’t find himself enmeshed in a web of criminality, particularly when he is drawn into it not through his own misdeeds but those of his family. Brennan’s son Eliot is to blame. He is 23, and has been up to no good since he was a teenager: first bullying, then drug possession, then dealing. But now he has finally run out of road: in jail after breaking bail, he is a marked man. Unless his father can help him by a criminal act, he’ll most likely soon be dead.

That, at least, is the exoskeleton of the plot, though it is also overlaid with a story about possible corruption in a major rebuilding project on the campus. Yet even as I type these words I am conscious of how scantily they do justice, not only to the quality of Welsh’s characterisation, but to the complexity of her novel’s themes.

Jim Brennan is, we are told, not only the son of a violent criminal but has a professorship in criminology. If having a vice-principal as your main protagonist in a crime novel is already stretching credibility, those two things stretch it even further. My own guess is that Welsh knows this, which is why she fleshes out Jim’s own back story so well, not only showing his break with and resentment of his violent father, but how hard he had to struggle to leave his past behind, and correspondingly, how much the stability of his middle-class married life with his architect wife Maggie means as a result.

Welsh doesn’t tell us this; she shows it. When Eliot is arrested, in all the ‘Where did we all go wrong?’ conversations Jim has with his Maggie, he is just that fraction more ambivalent about what to do about his son. Yes, he worries about Eliot and yes, he loves him, but he can’t help thinking that prison might actually be good for him. He would, you suspect, trot out the ‘You’ve made your bed, now lie in it’ lecture quite easily; Maggie never could. But to Jim – at least at the start – the law has to take its course. He doesn’t want to break it to help his son, not least because to do so would prove all those naysayers from the schemes right when they said he’d never make anything of himself. On top of which, now he has so much further to fall, all the way from near the top of society to total disgrace at the bottom. All the same, if his son really is going to be murdered, won’t his principles go out of the window?

Welsh has a knack for breathing life into unlikely protagonists, and if gay Glaswegian auctioneer Rilke was one (in The Cutting Room and The Second Cut), Brennan is most definitely another. Both read people well, in Brennan’s case whether in his dad’s old pub in the scheme on which he was brought up, or chairing a meeting of the university’s building procurement committee. ‘Sometimes,’ he muses, ‘the truth lay in what people did not say, the tilt of a head, the squint of an eye.’ Picking up on such things gives him the ability to push his agenda through a meeting – even a committee bristling with articulate independent-minded academics – so well that no one can even detect he had an agenda in the first place. For a would-be university principal, there’s no more useful skill.

In truth, this is at least as much of a campus novel as a crime one, and although a few satirical darts are fired, here we have moved on a long way from the comedy of Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim and David Lodge’s The Campus Trilogy. In To the Dogs, the university is firmly and sometimes worryingly locked into the wider world. One Chinese alumnus, just presented with his degree by Brennan on his China trip, has been arrested as a dissident. Bearing in mind the university’s massive financial reliance on its Chinese students, what is to be done? If these students have been taught to think for themselves, does the university have any responsibility when they are thrown into jail for doing just that? Another former student, this time a Saudi prince, is wondering whether a donation to the university could have his name attached to it: given that the students are already talking about this as an example of ‘blood money’, should his offer be taken up? Meanwhile, Brennan’s inbox is filling up with all kinds of other demands on his time. Funding applications have to be read and decided on, references have to be written: getting one of them wrong might not be a crime but, as we are shown here, could easily be a tragedy.

Both about the contents of Jim Brennan’s email inbox and in his personal life, in other words, Welsh implicitly asks one question above all others: What Would You Do? And because her characters are complex and not cardboard; because Brennan, for example, realises that Eliot’s delinquency might owe at least something to the way in which his all-consuming job meant they spent too little time together, we take that question seriously. Suppose we could only save our son’s life by committing an act which could ruin our own, would we do it? Suppose we discovered the name of the Chinese dissident and our comms team claimed not to know anything about it, would we leave it like that for the sake of a quiet life? What would you do?

Whether it appears on the bookshop shelves as a campus novel or a crime one, Welsh’s latest novel is more thought-provoking than most in either genre. From its dynamic opening to its unpredictable ending, it also holds the reader’s attention throughout. Find yourself a comfy chair in front of the fire and give it a go.

To the Dogs by Louise Welsh is published by Canongate, priced £16.99.

James Clerk Maxwell is regarded as the greatest Western scientist between Newton and Einstein. In his latest book, Bruce Ritchie outlines the importance of faith to this legendary scientist.

James Clerk Maxwell: Faith, Church and Physics

By Bruce Ritchie

Published by Handsel Press

When I was thirteen one of my Christmas presents that year was The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Science, published by Purnell and Sons. I had spotted it on the shelves of a newsagent’s shop in Jedburgh, and my cousin Graham and his wife Elsie gave it to me as a gift. The book was a treasure trove for a teenager interested in science, and it still has a place in my bookcase. As the years passed, its sections on the history of science, which highlighted prominent figures through the centuries, interested me more and more. Each scientist was given an artist’s illustration plus a concise pen-portrait, and the list included great names: Archimedes, Bohr, Curie, Dalton, Darwin, Davy, Edison, Einstein, Galileo, Hertz, Mendeleev, Newton, Planck, Röntgen, Rutherford, Simpson, etc.

Tucked away in a secondary list, and without the prestige of an illustration, was a brief, twenty-six-word reference to James Clerk Maxwell: Physicist. Studied heat properties of gases. Predicted existence of radio waves before they were discovered, and completely changed chemical theory with his electromagnetic theory of light. Despite this fleeting mention, Maxwell was of such stature that the American physicist Richard Feynman predicted that, in the long view of history, the most significant event of the nineteenth century would be Maxwell’s discovery of the laws of electrodynamics. Similarly, Steven Weinberg argued that without Maxwell’s famous equations contemporary physics would be unimaginable. Concerning the same formulae, Ludwig Boltzmann exclaimed: ‘Was it a God who wrote these signs!’ The equations are carved into the wall of Warsaw’s University Library. Albert Einstein said that the four men who laid the foundations of physics on which he constructed his theories were Galileo, Newton, Maxwell, and Lorentz. He also stated that one scientific epoch ended and another began with James Clerk Maxwell. When Einstein made his first visit to the United Kingdom, he was asked if he stood on the shoulders of Newton. He replied: ‘That statement is not quite right; I stood on Maxwell’s shoulders.’ Einstein esteemed Maxwell so highly that an image of the Scottish scientist adorned the wall of his study at Princeton. Commenting on Maxwell’s influence, Einstein stated in 1931 that people used to conceive physical reality as material points, whereas after Maxwell they conceived physical reality as represented by continuous fields, which were not explicable mechanically but which were subject to partial differential equations. Einstein regarded this transformation in the conception of reality as the most profound and fruitful change for physics since Newton. For Einstein, the special theory of relativity owed its origin to Maxwell’s equations of the electromagnetic field; he also held that Maxwell’s notion of the electromagnetic field could only be grasped properly through his theory of relativity.

In fairness, Purnell’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Science did have another reference to Maxwell. Near the end, in a section dealing with historic events in science, it identified 1873 as the year when Maxwell put forward his electromagnetic theory of light. The Encyclopaedia was a young person’s volume with no pretensions to being a comprehensive almagest of science, and the very fact that it mentioned Maxwell at all is to its credit. Moreover, its statement that Maxwell completely changed chemical theory with his electromagnetic theory of light, should have been enough to alert any careful reader to science of immense consequence in his work. But at the time, and with my limited knowledge, the information on Maxwell failed to spark a ‘Wow!’ moment. He seemed less important than the familiar big names. Since then, Maxwell’s significance has increased in the consciousness of society, with a stream of books and the occasional television programme highlighting his critical contribution to understanding the fundamentals of reality.

I read mathematics at university, and although we looked at equations associated with Einstein’s relativity theory we did so as an exercise in mathematics rather than as a reflection on the nature of the universe. Nonetheless, like other students of the time, I purchased James Coleman’s Relativity for the Layman and Banesh Hoffman’s The Strange Story of the Quantum, read them, and tried to get my head round the concepts involved.

Unexpectedly, it was when I studied theology that Maxwell became more significant. Our professor, Thomas F. Torrance, was working on the relationship between methodology in the natural sciences and methodology in theology. This involved reflecting on how to think objectively in each discipline, plus consideration of the disruption imposed on human thought by the type of concepts which our minds attempt to comprehend. Our ability or inability to ‘picture’ an idea can profoundly affect how we understand it. Torrance focussed on what he termed ‘the deep level conceptual interface’ between theology and science, rather than on the old questions of science and religion such as whether science proved or disproved God. Important to him was how Maxwell enabled physics to move beyond Newton, and how Maxwell explored the source of the rationality embedded in the created order. Torrance pointed out to us how Maxwell envisioned fields of force, instead of picturing individual objects acting on one another. He also stressed that our visual imagination is so accustomed to thinking in terms of objects hitting objects—since that is what we see around us—that we limit what we consider to be possible. Maxwell himself eventually moved beyond a visual representation of reality to a mathematical one. Though his deep-rooted instinct was to start with the empirical and the geometrical and to source everything in these, he came to realise that he needed to work differently, by-passing constraints imposed by the visual imagination. This radical new way of thinking inhibited early acceptance of his ideas. It was only after his death that Heinrich Hertz (1857–1894) and Oliver Lodge (1851–1940) validated his theories empirically.

Torrance taught us that theology needed to break away from similar limitations. He insisted that theology had to reconceptualise how things are: not from a visual construct, but from an auditory construct (analogous to Maxwell’s mathematical modelling) and proceed from there. As students we found this massively stimulating. And Torrance went further. He argued that Maxwell was able to exchange a Newtonian view of reality for a more relational understanding—as required in Field Theory—precisely because of his Christian faith and because of the relational way of thinking which the doctrines of the Trinity and Incarnation required. That did bring a ‘Wow!’ moment!

James Clerk Maxwell: Faith, Church and Physics by Bruce Ritchie is published by Handsel Press, priced £15.00.

Extract taken from Thirteen Ways to Kill Lulabelle Rock

By Maud Woolf

Published by Angry Robot

CHAPTER ZERO

The Fool

The sun is shining as the fool sets out on his journey. Everything he owns in the world is slung over one shoulder and in one hand he clutches a white rose. A carefree vagabond, his eyes are fixed on the horizon, unaware that he is about to walk off the edge of a precipice…

Lulabelle Rock takes another swig from her Pepto-Bismol pink smoothie. A single pastel raindrop escapes onto the front of her white bathrobe, where it is immediately absorbed by the terry cloth. She doesn’t notice or, if she does, she gives no indication.

Instead she smacks her lips, and levels a frank and serious gaze in my general direction.

“Can I tell you about my new movie? It’s a total flop. A disaster.”

I’m not sure if I should nod. I don’t get the impression that she’s actually asking for my permission. She doesn’t go on, her head tipping slightly to one side as she waits.

We watch each other for a moment, and then I relent. “Please do.”

Lulabelle preens, patting the white silk scarf around her head more firmly into place. A solitary blonde curl escapes and dangles perilously by the big wet strawberry of her mouth.

“Well,” she starts, leaning across the table. “When I signed up, I thought it seemed a sure thing. Spencer, my agent Spencer, he called it a hit and run idea. Hit and run. Isn’t that clever?”

I murmur in agreement.

“Well, it’s an adaptation. Of some art house thing. Swedish or Polish or Italian or something. Black and white. Subtitles. The whole shebang. The director, and he’s a good guy you understand, one of the best… Well, he’s always loved it, ever since he was a starving film school student. Medea, it’s called. It’s about a mother.”

“Your part?” I ask.

We’re sitting outside on the balcony and between us is a large glass table. When the sun comes out from behind the clouds it becomes a blinding disk of light. In those brief moments I feel as though we could be talking to each other over the surface of the moon.

“Of course,” she says, clearly a tad offended. “Anyway, this mother, she has children.”

“Naturally.”

“Two children. Two little boys. And a father, of course… Anyway, they all live in this big old house out in the countryside. It’s very damp and misty. England probably – it’s soggy.”

“Are they happy?” I ask.

“Oh, I suppose so,” Lulabelle says, slurping her drink. “The must be. But then a war starts. Or it’s been going on for a long time… I don’t think it’s clear. Anyway, the father has to leave. He’s a soldier you see. So, he leaves and then the mother is alone.”

“With the children?”

“Obviously. And years pass in that spooky house and all the time they’re hearing more and more news of the war through the radio, in those old-timey broadcasts, you know the ones… And this mother she’s so frightened and paranoid and she’s all alone in this big old house–”

“With the children,” I remind her, and she waves her shiny lacquered nails impatiently.

“Yeah, yeah, obviously. But she’s scared. She’s jumping at shadows. She keeps thinking, what happens if there’s an invasion? If the enemy finds us? What will they do? And then after years and years and years she hears a knock at the door.”

She pauses and looks at me significantly.

After a moment I realise I’m expected to jump in.

“Is it the husband?” I venture.

“Well,” she says and deflates a little. “Yes. But you aren’t supposed to know that. It could be anyone. Anyway, she thinks it’s the enemy, here to slaughter her and do unspeakable things to her babies. So, she kills them.”

“Who?” I ask. “The enemy?”

“No… the children,” she says, letting the horror drip from every syllable. “She murders her own children before the enemy can hurt them. And then, when they’re both dead, she goes to open the door with a kitchen knife. But who’s on the other side?”

She arches a single pale eyebrow over the hard rim of her dark glasses. For a moment we stare blankly at one another. “The husband?” I say.

“The husband!” She claps her hands in delight. “And that’s the end.”

I think about it.

“Hmm,” I say. “And this was black and white?”

“The original was,” she says with a shrug. “But our version isn’t. Our version has the most beautiful lighting. Red and blue and so on. Have you ever seen Suspiria?”

“No.”

“Neither have I, but I’m told it’s a dead-ringer. We weren’t going to make one of those trashy big studio remakes you see, where everything is pastel and toned down and safe. We wanted – well the director wanted – to go all in on the blood. Raw. That was the word he used. Unflinching.”

“The original wasn’t bloody enough for him?” I ask. I’m starting to get a headache from the sun. I’m not used to headaches. I don’t like them.

Lulabelle Rock has big dark sunglasses on. She can look at me all she wants, but I have to squint to make out the pink blot on her white swaddled body and the manicured gardens that stretch out behind her, the distant azure swimming pool and immaculate topiary hedges. It’s nice out here in the countryside. It could be a film set or a painted background, it’s so perfect. There must be fences at the perimeter to keep it so untouched but from here I can’t see them.

“The original was…” She pauses, tapping an electric blue nail against her canine tooth. “It was mostly implied. The violence. Reaction shots, tasteful splashes of blood on a wall. A child’s hand dropping a toy truck in slow motion. Yadda yadda. We didn’t want to do that. We wanted to go all in. We wanted to create something so horrible that the audience would want to look away. But they couldn’t. You see?”

“You showed the murders?”

“In excruciating detail. It was disgusting really. And inventive. It took twenty minutes for each child to die. Buckets of blood. Which of course was annoying because first of all, it stains and secondly, it was edible, so of course the kids kept licking it off their lips when they were supposed to be dead.”

A dark shadow passes over her face.

“Never work with children,” she advises me gravely. “They think it’s all just make-believe. They take away all the dignity of acting.”

“I won’t,” I promise her.

“But anyway,” she says, with a sigh. “It was supposed to be a masterpiece. My shot at recognition. No more playing the wife or the timid secretary or the party girl. No more big budget motion capture green screen CGI bullshit or voiceover cameos as Snicklesnork the troll.”

“I’m sure you were magnificent in that role.”