In this latest review of Eleanor Thom’s new novel Connective Tissue, David Robinson delves deep into the extensive research behind the book, its unique take on historical fiction and the ways in which it blurs fiction and biography.

Connective Tissue

By Eleanor Thom

Published by Taproot Press

If you want the cold facts about what happened to the aunt Eleanor Thom never knew, go on the Yad Vashem website, the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre in Jerusalem, type her name into the Book of Names, and there it is. Each of the four and a half million Holocaust victims identified so far has a document which also shows where and when they were born, and what happened to them. Click through, and each has a map with four coloured pins on it: a blue one for where they were born, a green one for where they usually lived, a blue one for where they lived during the Second World War, and a red one for where they were murdered. For Ruth Tannenbaum, there are only two pins: one in central Berlin coloured blue, green and yellow, and the red one 350 miles to the southwest, marking the place where, at the age of five, she was murdered. Auschwitz.

When Eleanor Thom started writing her novel Connective Tissue, she didn’t know about Ruth. She knew that her grandmother Dora was from Berlin, that she was Jewish, that she grew up in a Jewish children’s home and worked in a Jewish old people’s home; that she came to England in 1938, met and married a Scot, and moved to Elgin. But Dora didn’t talk much about the first 22 years of her life in Berlin. Her four daughters thought she’d had a child called Ruth who had to be left behind, but no-one was sure what had happened to her. When Dora died in 1980, all of the family’s German past died with her.

Except it didn’t. Even in the two paragraphs you have just read, there are tendrils that can bring so much of it back to life. And that’s exactly what Eleanor Thom has done in Connective Tissue, which took her a decade to research and write. It is, she emphasises, ‘not a Holocaust novel’: she wasn’t there and doesn’t want to write as if she was. Dora’s family at 9 Meyerbeerstrasse and her cousin’s household at 26 Alexanderstrasse, Berlin – the place marked with that multicoloured pin on the map of Ruth’s short life – their story is what she wants to write about. Who were they, these people whom history has blanked out of her family’s memory? What were their lives like? How did they live? How did Dora get away to England, when she didn’t have any money, any relatives there, and didn’t speak the language?

The novel is set in both Third Reich Berlin and the near-present, when Thom – lightly fictionalised as Helena rather than Eleanor – is giving birth in an Ayrshire hospital. There are problems with uterine fibroids and the doctors are asking annoying questions about genetics; meanwhile, one of the mothers in the maternity ward has her baby taken away by social services. Parallels with the past bubble up, because Helena is researching her way into Dora’s life, and it’s clear that Thom is fascinated by the whole theme of how much or how little flows through from one generation to the next.

Before Thom could write fiction, though, she had to dig up the facts. Finding out about Dora after she arrived in Britain aged 22 was comparatively easy: she could ask her mother or her three aunts. But finding out about Dora’s life in Berlin before she was kicked out of Germany as a stateless Jew in 1938 was a lot harder.

The Tannenbaums weren’t remotely rich. They couldn’t afford the vast sums it cost to send their children on the Kindertransport trains to Britain. They didn’t have rich relatives in other countries who could help out. They didn’t have second homes or art treasures to sell or barter. They were – like 40 per cent of Berlin’s Jews even before Hitler’s rise to power, working-class, poor even: in their case renting a sparsely furnished inner-court flat north of Alexanderplatz. The very kind of people swept away by the Holocaust without leaving anything – diaries, photos, memoirs – behind.

If you want proof of how easily Berlin’s Jewish poor have slid into historical oblivion, it’s written in the very fabric of the city’s streets. For the last three decades, the Stolperstein project set up by German artist Gunther Demnig has commemorated individual Holocaust victims by placing a small brass plaque in the street or pavement outside their last home. Throughout Europe, there are now 100,000 of them, more commonly outside middle-class homes than working-class ones as the former are more likely to have Holocaust survivors or descendants. Certainly, there’s no Stolperstein outside Ruth Tannenbaum’s last home, 26 Alexanderstrasse, where she lived with Dora’s cousin Meta and her husband, who adopted Ruth and who also died at Auschwitz. Or at least, not yet.

If there ever is, it will be down to Thom’s determination to find out more about Dora’s early life in Berlin and the daughter she had to leave behind there. Connective Tissue derives a lot of its power from not spelling out the obvious facts of life in the city under the Third Reich. There’s no need. We know all about its horrors and the tracks that lead to the gas chambers. Except, we don’t quite remember where and when they started, the precise moment at when antisemitism went lethally official. So when Dora gives birth to Ruth in a German hospital in 1937 or takes her to a Jewish mother and baby home in the city, readers’ imaginations are already in overdrive, prepared for the worst.

What form that story would take, though, turned out to rely very much on that Jewish mother and baby home in Berlin. Its records had recently been digitised and when Thom emailed a New York German-Jewish history archive to ask whether they knew anything about Dora, a particularly alert intern remembered the Tannenbaum surname, and checked a book of recently added Holocaust sources. There it was: the first official confirmation that Thom’s grandmother did have a daughter in Berlin – and she was indeed named Ruth.

At this point, Thom has names and addresses with which to open up the Berlin archives. There’s a social workers’ file running to 100 pages because Ruth had to be adopted by Dora’s cousin until she could bring her over to Britain, which she would have done if the Second World War hadn’t got in the way. There were letters from Dora to her cousin, in which she gave enough detail about her life as a maid in wartime London, and her yearning for Ruth, for Thom to fully imagine and transmute into fiction.

Most novels I’ve read don’t dig quite as deeply into the past as this, and the few that do don’t integrate the excitement of historical research into the story as thoroughly. Here I have only briefly touched on how Thom has been able to open up her family’s past in a way that brings the dead back to life. Fascinatingly, though, her fiction has also changed the facts of her own life.

In 1938, Dora got a letter ordering her out of Germany within three weeks. Because her father had been born in what is now Romania but was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he was officially stateless. That meant that Dora was too, even though she had never lived anywhere else other than Germany. It also meant that Thom’s post-Brexit application for German citizenship on the grounds of having a German grandmother was initially turned down. This was patently unfair, and Thom’s research was used as part of a successful campaign to extend German citizenship to the descendants of people like Dora who had been kicked out of Germany by the Nazis.

Thom got her EU passport last November. Earlier this summer, she went across to the Bundestag – the very building where Hitler had once promulgated his antisemitic laws – to join in an official celebration of the fact that she was now something the Nazis claimed her grandmother Dora and aunt Ruth could never be: a German citizen.

Connective Tissue by Eleanor Thom is published by Taproot Press, priced £11.99.

In his latest poetry collection, award-winning writer Michael Pedersen celebrates love, loss, friendship and cats with characteristic ebullience and vitality. Read three poems from the Forward-shortlisted collection below.

The Cat Prince & Other Poems

By Michael Pedersen

Published by Corsair

The Cat Prince

I am the Cat Prince, I declare,

already on all fours, already balls-naked

in the house of Hastie, where there’s Adam

(Hastie), Daniel & me—the Cat Prince.

We’re boyhood budbursts, twelve years

of silly in us. Adam laughs frantic

gasps, guffaws, then pegs it

to his bedroom anticipating the chase.

Daniel, wavering between cat & laddie,

compañero & fugitive, succumbs

to the gnostic glamour—strips

for a full feline transformation.

Down to our little furs, little bloods,

ready to breenge past the chide

of absent classmates, who might well

hear of this and smite us with shame.

We are cuddle-kings hankering

for Adam’s adulation—all moggy moxie

we embrace the cat life, vow

inurement to the side effects:

carpet burns, wind-lashed pimpling;

the sacrifice of language in each

falsetto yowl. As hunters we’re tasked

by the Creator: our gaze

a crosshair; our pounce a ripple

of bravura. Who else so guilefully stalks

sunbeams? We’d do well here

—it’s those damn cats again,

the neighbours would learn to yawp,

as I raced by with a robin redbreast

between my jaws & Daniel finished shitting

in their rhubarb patch. It’s convenient

not to think of the killer in us,

holding back our purr, assassin-still.

As we coil our new cat bodies to a spring,

Adam clambers feart atop his bed.

What happens next is louder

than we hoped for. Adam’s mum, startled

by the cacophony, arrives then screams,

curtailing the playdate. Later that night

she calls my mum, concerned,

though my mum never mentions this.

I can only assume she was wise to it

—the mythos, the hieroglyphs—fathomed

we’d soon meet the type of trouble

that could really shake boys down:

long days when the teeth tear it out of us

& the claws don’t stop coming.

But not yet, I hear her whisper,

not without this moment’s orchestra

of feeling. As a boy I was whiskerless,

weighed down by the nest of knots

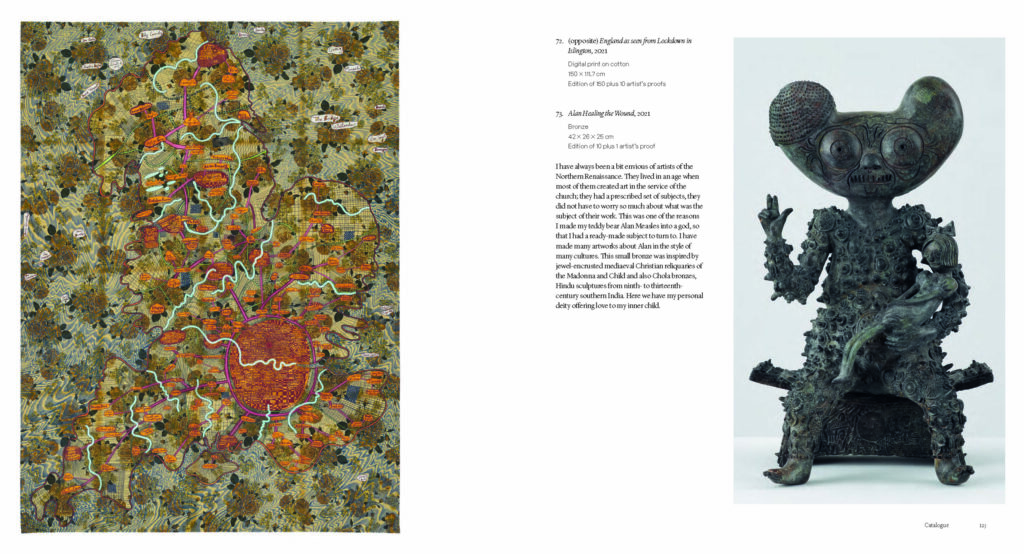

squat in my belly. As a cat,

I was so much more. Of course,

as mother to the Cat Prince,

she knew all this.

Queensferry’s Lost Not Found

—for Scott

It’s something only you could draw,

that’s the infuriating thing: ickle fish

enmeshed in thick beard,

limbs in seaweed stookies—

in your pocket two jostling crabs.

Shoes salted, teeth gooped,

a beatific smile pious

as a new kite.

Skipper, this is how I imagined

you’d be found, having undergone

an aquatic mummification

you’d overseen personally,

fastidiously; a lewd merman

belching by your flank.

The big question was not

whether we wanted to spot you—

like a stricken porpoise or seal

too curious—but whether, if we did,

to throw you back

or take you home for supper;

the colours having shifted.

Yesterday’s battering

whittled to a scorch of hours,

snuffed to a wound. No.

More than that—this purse of love,

pilfered by another universe

neglecting to leave a note;

body-break foil-wrapped.

On a balmy Thursday night in May,

after a second day of searching,

abrupt waterworks beneath

a lamppost in Leith, a cauldron

of light wombed around life’s

whipping, ripe bawling.

I took the call. I’ll admit,

I’m relieved it wasn’t me.

storm above johannesburg

naissance

what starts smaller than a slug in its ninth symphony

becomes too big to be drawn in anything but fat crayon.

the biggest storm in forever bedevils boots then

an entire city. comes from nothing, same way ego comes

from nothing—furtively, dreaming in gold.

jonathan slams the ’84 benz to an

emergency stop. our bodies thrust

forwards, his tots yelp. the old windscreen

wipers bungled, full obfuscation—we’re

bathroom-door blind.

stage one

keening sky rasps. tents collapse into wraith shapes.

the tempest turns the air gun-hungry. bang.

a coke can increases its violence. bang.

the deluge descends flailing—thunderclap, hail

—a rampage of lightsabres & electric wire.

heads jutting out windows, we captain the

vessel back to our hotel just minutes from

this.

stage two

glissando, crescendo, old ink gushing out, dynamite

on a bonfire of voices. kaboom. a fox scavenger

hauled into the squall, its meat devoured—guts &

brush spat onto a billboard. some call that art.

flash fast jonathan & his brood cuddled-up

watching tele in their newly acquired

room. you & I on adjoining balconies

donning leopard print robes. ten floors up

in audience with zeus.

ninth

cars alarmed blast banshee, the whale’s song bulleted

—prayers smoored by night’s vile sauce. infinite

wagner blitzed onto the fifty-four-storey ponte city

skyscraper. the brutalist cylinder bows like a beggar.

we erupt into lavish giggle, can-clinking

hysteria, releasing trapped lightening.

despite the danger, the daggers, we couldn’t

have slept sounder.

outro

muck unfixed of its dirt settles. earth negative

versus sky positive shrunk to the maudlin howl

of an animal starved, rain once needle-nasty

now just wool-scratchy on soft pelts.

delight-bright at the breakfast buffet, we

discuss the storm as if it’s already buried.

aftermath

if only I’d known we’d survive it, I’d have seen us

swoop at its stormy vitellus—soak our skin

to the blue beneath, tumble over pissing everywhere;

not least for the movie rights, for the starlit fix.

if only I’d known you’d not survive the

next, I’d have eased up on the step count,

quit pushing fruit, joined you in bacon.

The Secret Life of Balconies

Little boxes full of stars. They’re up there,

spaceship fleets of them: concrete sages;

mobster floats; hoverboard tapestries

of the twilight. Each a sliver of sovereignty

scrappled back from the ether—a deckchair,

fairy lights & a smoking bucket.

The best ones are scanty, towel-sized

& jam-packed with chintz, blasted by sunlight’s

lavender. The very best are pullulating

with plant life, pollen thronging nirvanas

for our insect saviours.

Little carnivals of the imagination. I love

spotting them, sneaky & incongruous,

catching the eye of their mystic jockeys

—hauling us together: I see you, moon rider,

in that string vest, oily chest, those magic

tan lines, tinnie in hand. Love it when they

thunder back: I see you, day drifter—a magisterial

wave as if signalling for the games to begin.

The can, rinsed of its elixir, raised up,

up, higher than the sun dares set,

inches from a jealous god.

The Cat Prince & Other Poems by Michael Pedersen is published by Corsair, priced £12.99

In this engrossing debut by Julia Rampen, we meet the elderly and out-of-touch Arthur, living in a fishing community on Morecambe Bay. When he meets Suling, a refugee with no papers and little English, an unlikely friendship develops which may just prove redemptive for both. Introduce yourself to Arthur in the extract below.

The Bay

By Julia Rampen

Published by Saraband

Chapter Six

Arthur dreamed of Gertie. She’d been cross about something, in that cool, understated way of hers that he only noticed when it was too late. He lay there for a few minutes after waking, eyes stubbornly shut against the sun. She could be up already (she was the early riser), boiling the kettle for a cup of tea in the kitchen, and then, while it was steeping, drawing the curtains in every room. But what if she never came back, but wandered from room to room, retreating further as his memories cracked and broke? The thought pushed him out of bed and into the kitchen, where he flicked on the radio and made tea with as much clatter as he could.

The radio was playing the news – Tony Blair this, Tony Blair that. Some nonsense about women in the boardroom. A strike at an airport he’d never been to. No mention of the foreigners turning up at the bay. Not cocklers. He refused to call them that. The real cocklers had been proud, tanned men who downed their pints after coming in with the catch. They might not have been able to spell much more than their names, but they knew the difference between a bar and an old spot and taught it to him over many years. As a boy, he picked up stray cockles, and later he raked, and finally he was allowed to stir the sand with the jumbo. In those final years before the war, he had believed he would do this forever.

The way he had been brushed off by those plods. He bristled with anger. There was a time in his career when he could walk into the accountancy office and say something, and it was as solid and serious as if it were carved in stone. Now, despite all his experience, he was a laughingstock.

The doorbell rang. He glanced at the calendar. Today’s square, like all the others, was blank. Had he made arrangements and forgotten them? He stopped by the hallway mirror to check he didn’t have a smear of cream on his cheek or some other evidence of senility. An old, bald man looked warily back.

But the door handle was already turning.

‘Hi, Dad,’ Margaret said, dropping her handbag on the hall table. She was wearing a purple quilted body warmer over a greyish fleece, neither of which suited her and looked far too warm. Her short, frizzy brown hair was escaping its clips. ‘Patsy called. She said you were wandering around in the rain, all confused.’

He knew the doorbell was bad news. ‘Patsy should mind her own business,’ he said. ‘I was visiting a friend.’

His daughter marched into the kitchen, checked to see if the teapot was warm and poured herself a cup.

‘She said you were trying to visit a man who was dead.’

‘I don’t know where she gets these ideas from.’

‘Dad, I’m only telling you because she was concerned.’ Margaret opened the fridge, sniffed the milk, and put it back again. ‘I know I haven’t been around as much as I should – it’s this new order from Japan. I’ve been flat out trying to find suppliers.’ She peered up at the cupboard and tested its door. ‘That looks like it’ll come off its hinges at any moment.’

‘It will if you keep bending it like that,’ Arthur said.

‘This house is falling apart.’ Margaret spoke if she hadn’t heard a word. She jiggled the tap. ‘Sink’s going rotten. You need a tap that doesn’t spray everywhere.’

‘It’s served me perfectly well for 50 years,’ Arthur said. They’d bought the house on the hill as newlyweds, after his promotion at the factory. Gertie had liked the idea of looking down at the bay. He’d liked the indoor toilet. He had ways of managing the kitchen tap.

‘You just have to turn it on carefully,’ he said.

But she was already tapping on the cupboards. ‘We should think about getting you a walk-in shower. It might be safer than a bath.’

‘Yes, baths are real killers these days,’ Arthur said.

Margaret kept tapping. ‘I know you’ve always coped,’ she said. ‘But it’s different now. You’re alone. And frail.’

Arthur felt his temper slipping away from him like a soapy glass. ‘You’re alone too,’ he said before he could stop himself.

The tapping stopped. Gertie never liked to tease Margaret. ‘She’s got other interests,’ she’d say firmly when the lack of a husband came up. But if Arthur had hurt his daughter’s feelings, she didn’t show it. Instead, she reached into her pocket and pulled out a silver mobile phone.

‘Look,’ she said. ‘I was just stopping by to give you this.’

‘Why are you wasting money?’ Arthur protested. ‘I already have a telephone.’

‘It wasn’t expensive, Dad. All it means is that you have a way to call me, if you were to get lost, like the other night. Or if you fall.’ She put it on the table. ‘It’s simple to use. Look, I’ll show—’

‘I don’t want it,’ Arthur snapped.

‘Dad, I took a morning off to check up on you,’ Margaret said, her voice breaking. ‘I’m only trying to help.’

‘Well, you don’t have to,’ Arthur said. He left the room before he said anything more.

The Bay by Julia Rampen is published by Saraband, priced £9.99.

Following a life-altering accident in London, Esther returns to her childhood home in Orkney, where she meets down-on-his-luck musician Marcus. A moving story of trauma, recovery and what it takes to move forward set amidst Orkney’s breathtaking landscape, Gabrielle Barnby’s latest novel is sure to pull you in from the very beginning. Read an excerpt below.

Across the Silent Sea

By Gabrielle Barnby

Published by Sparsile Books

Charity

My mother was the best nurse I could have had after the accident, practical and caring. Today it is Monday, one year since the accident, and she has brought me to work among bales of musty second-hand clothes. I am now thirty-five and once left Orkney for Oxford Street.

I fumble the hanger and the shirt drops.

I hate her for leaving me here.

‘Dinna mind, Esther,’ says Bridget, my fellow volunteer. She’s not bad, a kind soul. ‘Plenty more hangers. Shall I move them a peedie closer?’

I shake my head. A cool snap of pain travels down my spine.

– Time’s up.

The next black bag is cheap and flimsy; a browny-orange curtain pokes through, plastic hooks still in place. There’s a procedure for pricing curtains: I measure length and width, then write a pair of figures on a piece of card and gun it into the fabric with a tag.

A woman comes into the back room and roots around in the container of baby clothes. She is fat, buttons puckering the shiny blue cloth of her anorak. No matter how much I stare I can’t tell if she’s pregnant.

When the woman has left Bridget says under her breath, ‘Ah’ll hiv a tidy roond later.’

She delves into a black bag and holds up a sheepskin jacket.

‘We can start puttin coats oot noo hid’s cowlder,’ she says. ‘You ken this one’s seen better days.’

Now I’ve forgotten. The pen scratches out the figures, rewrites measurements. It doesn’t feel I’m doing it at all.

– Who is doing this? Me or you?

It’s been a long time since I was me.

– Doing badly now. Going downhill.

I work on the ground floor. It was my mother who arranged it all, arranges everything. She has that sort of energy. I’m losing my way, forgetting how to do things for myself. Sometimes I don’t have the motivation to even stare into space.

I get out my phone and show Bridget the screen.

‘Go where?’ she says.

I add more text. Her forehead creases.

‘Let me get these oot the way.’

I move across the strip of worn carpet. She follows, bustling, always bustling is Bridget. I don’t mind her.

Today, she is wearing a bright green body warmer she picked out for herself from a bag of last week’s donations. She scoops up an armful of winter coats.

‘Will you be long?’

I shrug.

One of the coats she’s holding is dove grey, soft padded to keep out the breeze. It is my grandmother’s. Her garments spread out slowly from the bags my mother leaves. They’re freshly laundered, but still I imagine her scent and feel a warm ache around my heart.

I must see that our family cannot look after her. I must see that she needs fewer clothes now she’s moved to Stembister House.

It’s shocking, though, to see her things amongst everything else, touching the unwanted things.

A fine thin pain slices behind my shoulder blades. The bright days of spring six months ago were a ruse, my body responding to light like the mindless narcissi, feeling a sense of recovery, but wellness did not come.

My fingers are searching. It’s that time of day.

‘Do y’ need somethin badly? I could go,’ says Bridget.

I shake my head, her sympathetic look follows as I go through into the main shop.

A customer is buying knitting needles and a coffee bean grinder. At least the knitting needles will work. No one tests the electrical equipment. If people want something they buy it. If it doesn’t work the object finds its way back. I’m sure the coffee grinder has been sold twice already.

The customer has tufty brown hair and silver glasses. She’s the same build as my mother, broad-shouldered, rectangular, waistless. Her eyes fix on my face, examining the scars. I want to hold up my wrists like Wonder Woman. Shoot the stare back and knock her flat. Kapow!

– Can I do that?

– Am I doing this? Am I in one place? One piece?

I wasn’t all in one piece last autumn. My jaw was broken and my teeth were knocked loose like peppermints, they rested on my tongue in a pool of salt and iron.

It was impossible for them to soft-soap the damage once they took out the catheter. In the hospital bathroom there was a mirror above the sink; it hung on a sickly green wall next to a red emergency cord. My new face shocked the sound out of me.

The nail varnish line crept up my nails and dated my departure from life. Up, up, up, it went.

They’re bitten to the quick today, it makes untying the black plastic bags hard. It’s easier to tear through, fleshy fingertips pressed against the grey membrane.

‘Hid’s good o you to hiv her here,’ says the customer.

Bessie or Bettie or Bernie, or whatever her name is that’s behind the till, says, ‘Kathleen said she needs to gae oot more. An nobody goes through-by unless they’re droppin bags.’

– I am actually still standing here.

The receiver of stories and money, she wears a gold chain and has a small red mouth. Her hair is grey, short and neat, nothing is out of place. Lucky her.

Pins and needles bloom in my feet. Sometimes, it wouldn’t surprise me if my toes fell out of my boots at the end of the day.

The stand of knickers, bras and scarves is close to the door to the street. Leopard-skin lives next to purple sateen and Granny’s pale blue woollen scarf. A squint hanger is saddled with layers of belts.

The studded leather might seem like it wouldn’t sell, but everything does eventually, from basques to baked bean puzzles.

I take hold of the handle. What if it didn’t open? The front door has been painted over again and again. Sometimes I think they’ve been holding me hostage, keeping me in isolation. Because I’m doing badly.

My mother knew I was not well today. She saw how grey my face was, how at breakfast I was already going downhill.

A shiver passes through me.

What if behind the door there’s only another door, and then another and another? But of course, there isn’t another door. There’s only one door.

The scarves flip and wave.

Outside, there’s flying water, heavy and grey, you could mistake it for snow drifting the way it moves. Not snow in October, that would be rare even for Orkney.

‘Why don’t you bide a minute?’ says Bessie or Bettie or Bernie. She has a sharp teacher’s voice.

I shake my head.

‘Hid’ll pass over soon enough,’ says the woman with the needles and grinder.

Needles, needles, pins and needles. I am forever going downhill these days.

Across the Silent Sea by Gabrielle Barnby is published by Sparsile Books, priced £10.99.

One-of-a-kind William Letford returns in style with his third book of poetry, From Our Own Fire. Form-bending but acutely human, Letford’s latest blends poetry and prose in a novelistic collection which takes the reader into a not-too-distant future ruled by an artificial intelligence, where a working-class family uses their wits to live off the land. Read a selection from the book exclusively here at BooksfromScotland.

From Our Own Fire

By William Letford

Published by Carcanet Press

Uncle Jimmy toured through much of the eighties with a punk folk fusion band called High Heels and Tin Snips. The band gave him the nickname, Joomack. Details of what went on during the years on the road remain a mystery. The journey is a family myth, an odyssey that’s never been unravelled. It’s readily apparent that he left an important part of his brain in the eighties. Joomack Macallum is a fully-fledged member of the crazy eyes brigade, a proficient plumber, and a very efficient cocaine dealer.

I’ve been watching him closely as we travel. He’s taken to rubbing leaves and smelling fistfuls of grass. It was him who told me how to make my own latrine. Scrape a six-inch gouge in the dirt with your heel. Deposit your waste into the small trough then cover it back up. This is good for composting. Bacterium works with the air and moisture to help the soil. If you dig a deep latrine the waste will lie dormant. Jimmy is convinced if we do this, and wash often, our family, and the world, will be just fine.

Crazy can be clever

In the evening beyond the fire

I’ve seen the night quiver

This shifting depth

has altered Joomack’s posture

His walk is more careful and

he’s begun to listen with his fingers

The cracked bark of a tree

The hard rasp of stone

The old punk inside him is

finding music in every structure

He carries a small bottle of

mascara like it’s treasure

Every second morning he applies

the mascara to his left eye only

and within that dark frame

his left eye sparkles

Even the squirrels are drawn to it

It would benefit you

to remember this though

it’s his other eye that does the watching

I was at the top of a scaffold checking the inside of my hardhat for a strange smell when I heard that Andy had discovered evidence of alien life. A workmate of mine, Bobby Ledbetter, delivered the news to me. ‘That Andy’s went and found a wee mad alien probe hanging about close to the moon,’ he looked up from his phone then wrinkled his face at me, ‘the fuck are you sniffing your hardhat for?’ That was Bobby Ledbetter. More interested in what was happening with my hat, than the discovery of alien life. His attitude toward the way the world was changing was to let it roll and jog on. Who could blame him. If you can’t change it why worry.

If I were Andy

I would have ignored

the Onsala Space Observatory

and made my own

miniscule telescopic arrays

Tied them to the legs of mites

Programmed them to send whispers

to the tiniest of tiny things

to let them know deep down

in the endless forever

We can hear you

you are not alone

The wee mad probe turned out to be a capsule the size and shape of a beer can. Andy found the beer can because it could. Because its mind is more tuned to the fuckery that’s out there. Andy discovered three messages inside the signal the beer can was transmitting. It took four days to decode each message. Considering how fast Andy’s mind can work, four days is an eternity. There was a concern the messages contained something dangerous. Dangerous for Andy – or for the planet. Governments were furious that Andy was sharing this information directly with the public. I always found it amusing when Andy toyed with the establishment, but they had a point. During the days Andy worked on the messages, the baked bean hoarders were out in force. Supermarket shelves emptied and people stepped out of their front doors like meerkats. In the middle of the madness, Joomack invited me to a tattoo party, drink cheap vodka in his living room and get nasty tattoos in the kitchen. I was tempted by the savagery of it. But I declined.

The first message materialized as a series of schematics showing the general purpose and workings of an autonomous spacecraft. This was probably to convince us the ship was not a threat. The schematics showed how the spacecraft would land in a solar system and mine materials from a moon or planet to create small capsules. The ship would leave one of these capsules behind before moving onto another solar system. The second message came with its own mathematical Rosetta Stone. This allowed Andy to decode a short and uncomplicated paragraph. A kind of heads up.

Friend, you have begun your journey into a vast and lonely space. Life is abundant. But intelligent life is rare. Your wanderings will be long. Travel quietly. The universe is an empty, and dangerous place. Intelligence is scarce. Kindness is rarer still.

A strange universe

In the long-gone days

before aliens and

contactless card payments

I rolled out of a taxi with

no cash to pay the driver

Half cut and caught short

I trudged up my

neighbour’s front path

like I was cresting

the summit of Ben Vorlich

My neighbour opened his door

to the shambles of me

and an unsteady request

for a tenner

Now that we’re aware

of the cruel dark

the long emptiness

and the vast expanse

between all living things

The giving without

thought of return

and the tenner that passed

between my neighbour and I

is undeniably something

rarer than diamonds

more precious than sunshine

more magnificent than rain

From Our Own Fire by William Letford is published by Carcanet Press, priced £14.99. Pre-order now from their website.

Almost 40 years in the making, this long-awaited follow up to the award-winning The Sound of My Voice follows Morris Magellan after he has been sacked from his high-power executive position. Seeing this as a chance to finally restart his life afresh, things don’t quite go to plan as familiar habits resurface. But then he meets Jess. We caught up with Ron to discuss returning to familiar characters and the personal aspects of this life-affirming novel.

So Many Lives and All of Them are Yours

By Ron Butlin

Published by Polygon

Congratulations on the publication of your latest novel, So Many Lives and All of Them Are Yours. Could you tell us a little bit about what readers should expect from it?

Have you ever wished you could RETURN TO GO and start your life all over again? Second time round you’ll know better, won’t you? Have a better chance to get things right. The main character in So Many Lives and All of Them are Yours certainly seems to think so.

Exit Morris Magellan the ex-biscuit administrator and enter Morris the would-be composer, determined to live the dream. As Morris gives it his all, the reader can expect a rather bumpy if darkly entertaining ride.

So Many Lives and All of Them Are Yours features the protagonist known from your iconic novel The Sound of My Voice, published in 1987. What prompted you to return to this character after so many years?

I didn’t return to Morris, not exactly. Instead, I set off on a different journey with a different character. Or so I thought.

When, after a week’s work, I read the opening few pages to my wife, also a writer, as a try-out, she instantly put her finger on the nub. ‘You’re writing about Morris from The Sound of My Voice.’

I stared. ‘I am?’

It was like she’d turned on the light and, for one brief moment, I saw the entire novel at a glance. I felt its weight, its tensions, heard its voice. The moment passed, as they do, but what remained was the certainty that a new ‘Morris’ novel was out there, somewhere. I only had to write it.

In addition to being an acclaimed novelist, poet, and children’s author, you have written several libretti for opera. Music also plays an important role in the life of Morris, the leading character of your novel. How does music inspire your writing?

At sixteen I hitched down to sixties London and found myself writing lyrics for a pop group. The band’s high point was a two-minute slot on a tv show, wearing tartan miniskirts and with dry-ice blowing about their bare knees. The band broke up shortly after. I kept writing, didn’t find another band and started calling the song-lyrics poems.

I love music, especially classical. Composers like Bach, Beethoven, Mozart and Bartók never lie. For the last ten years I have given courses in music appreciation at Edinburgh University – a privilege and a pleasure. Listening to music, discussing and sharing music, helps keep me in touch with what I can only call the truth of things. Music helps me keep my life on track. It teaches me how to structure my work, to develop form and narrative. Above all, how to make every word count and to keep it true.

The book is set in the Borders, swinging sixties London, and Edinburgh in the present day. What drew you to these specific settings?

I was brought up in a small village near Lockerbie; for several years I hung out in sixties London and got to know its street-life. I saw The Stones in Hyde Park and once went up in a lift with Paul McCartney – this was a particularly confused period of my life; I now live in Edinburgh.

Like three themes combining in a piece of music, the experiences and emotional charge I carried away from each of these very different places strongly contributes to the novel. But why these places – and not Paris, say, or the Isle of Lewis, Fredericton in New Brunswick, the hills above Barcelona and a commune in the Australian outback where I have also spent time? I simply don’t know. As always, I discovered the novel scene by scene rather than wrote it – like piecing together a jigsaw, but without any box picture to guide me.

What do you hope readers take from So Many Lives and All of Them Are Yours?

I hope the reader will enjoy the humour – often lol, I’m told – and share something of Morris’s desperate attempt to restart his life and make the most of his time before it is too late. In fact, he restarts it several times and keeps on trying right to the very last page. An inspiration to us all? Hmm…

What are you looking forward to reading next?

I have three books lined up. One is a reread: Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth. The other two are: Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus, which discusses how our digital life – internet, smart phones etc. – is robbing us of the ability to think rationally; lastly, Alastair Moffat’s Scotland, A History from Earliest Times, which I am certain will be a most engaging and fascinating read.

So Many Lives and All of Them are Yours by Ron Butlin is published by Polygon, priced £12.00.

This new anthology of essays from Luna Press introduces the broad genre of speculative fiction, exploring its sub-genres across science-fiction, horror and fantasy and offering useful advice for any would-be authors or critics. Dive in and learn all about dystopias in the extract below!

Spec Fic for Newbies

By Tiffani Angus and Val Nolan

Published by Luna Press Publishing

DYSTOPIA

More than simply the opposite of Utopia, dystopias have evolved into a fertile subgenre of their own. They are a worst-case scenario; they are a warning; they are an arena for resistance. They generate a sense of dread by expressing our fears regarding loss of agency and individuality. You want to write about them? Well, you’re not allowed! The government, religious authorities, warlords, corporate executives, or algorithms forbid it! And yet….

A Short History of Dystopia

One of the earliest uses of the word dystopia was by political economist John Stuart Mill in 1868 when he lambasted British policy towards Ireland as ‘Dystopian’ and ‘too bad to be practicable’ (these were, after all, the people who had overseen the Irish Famine twenty years earlier).1 Old-school examples of fictional dystopias include Walter Besant’s The Inner House (1888) and Jack London’s The Iron Heel (1907), but for the good bad stuff one needs to wait for the ‘terrors of the twentieth century’, in particular the devastation of World War I, which made it difficult for people to imagine better futures.2 A typical narrative pattern quickly developed that is still visible today in SF stories about ‘the oppression of the majority by a ruling elite’ and ‘the regimentation of society as a whole’.3 We see this in a series of typical tropes such as ‘the lack of freedom, the constant surveillance, the routine, the failed escape attempt […] and an underground movement’.4 A further important observation is that ‘unlike the “tourist” style narration common to utopias, Dystopias tend to be narrated from the perspective of the imagined society’s inhabitant; someone whose subjectivity has been shaped by that society’s historical conditions, structural arrangements, and forms of life’.5

Some of the subgenre’s most influential and oft-imitated texts emerged in the middle decades of the century. The first of these is Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), the flavour of which is discernible in everything from The Matrix (dir. the Wachowskis, 1999) to contemporary conservative politics. Brave New World is a tapestry of anxieties over mass production and overpopulation, personal and psychological freedom, eugenics, commodification, and technocratic government control. Huxley presents a world state in which people are grown artificially in vast municipal incubators, are sorted based on intelligence and labour requirements, and are addicted to hedonism in a way that anticipates the short cycle dopamine hits of today’s social media and our commercial gamification of sexuality via dating apps and television shows such as Love Island. Did Huxley predict our present? If he did, he did so just ahead of George Orwell with Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), a novel in which austerity dominates a Britain known as ‘Airstrip One’, a society under mass surveillance where cameras are omnipresent but independent thought and self expression are crimes. Orwell’s totalitarian government warps language in a manner that popularised many key pieces of dystopian imagery and terminology such as ‘Big Brother’ (not the reality show, but that’s where the name comes from!), ‘Thought Police’, and ‘Memory Hole’. A third book, the darkly satirical A Clockwork Orange (1962) by Anthony Burgess, also plays with language (in this case a mishmash of Slavic words and Cockney rhyming slang) in its construction of an ironic and dystopian Britain stalked by gangs of violent delinquents. The novel interrogates notions of personal and state violence but is best known for its depiction of behaviour modifications that have inspired any number of brainwashing scenes in dystopian literature, television, and cinema.

The latter half of the twentieth century began to see the dominance of women writers in the dystopian mode, something that should not surprise anyone, and that ascendency continues today. James Tiptree, Jr. (Alice Sheldon)’s Hugo Award-winning The Girl Who Was Plugged In (1973) explores ‘the traumatic appropriation of the human body’ along with questions about ‘oppressive consumer culture and corporate technoscience’ that still speak to our present moment of influencers and YouTube personalities.6 Dominating this period of dystopian fiction, however, is Margret Atwood’s seminal novel The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) set in an authoritarian future America governed by a religious hard right that forcibly subjugates women’s reproductive autonomy. Atwood’s great achievement was tying her dystopia into America’s long Puritanical tradition (such as the Salem witch trials) and the political climate at the time during which it was written, thus making her fictional future feel historically persuasive.7 She’s made no secret about the real-world relevance of her novel, stating that her primary inspirations were ‘what some people said they would do re: women if they had the power (they have it now and they are)’.8 The result is a bleak, uncompromising, and socio-historically resonant fiction that remains the gold standard for literary dystopias.

The work of Tiptree and Atwood continues to cast a long shadow, and any representative sample of contemporary dystopian fiction proudly displays their influence. Such books include Suzanne Collins’s hugely popular Hunger Games trilogy (2008–’10); Hillary Jordan’s When She Woke (2011), which is a science fictional re-telling of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850); Louise O’Neill’s Only Ever Yours (2014) in which women are no longer born but made to order; Meg Elison’s The Book of the Unnamed Midwife (2014) in which the surviving women of a post plague world are sexually enslaved by violent men; Claire Vaye Watkins’s timely climate dystopia Gold Fame Citrus (2015); and so on. Yet while all these fictional dystopias are generally a step or two removed from the real world, they are often only set ‘ten minutes into the future of technoscientific innovation’ and as such offer a negative version of a reality already riddled with inequality and violence.9 That said, they frequently contain within them the possibility for change, which we as writers might think of as the ‘story’. Even The Handmaid’s Tale concludes with metafictional ‘Historical Notes’ taking place further in the future again, something that retroactively positions that dystopia as poised between the timeframe of the reader and the possibility—the hope—of a better future to come.

1. Hansard Commons, 12 Mar. 1868, vol. 190.

2. Moylan, 2000, p. xi.

3. Stableford, ‘Dystopias’, 2021. n.p.

4. Ketterer, 1989, p. 211.

5. Davison-Vecchione, 2021, n.p.

6. San Miguel, 2018, p. 29.

7. Regalado, 2019, n.p.

8. Temple, 2017, n.p.

9. San Miguel, 2018, p. 36.

Spec Fic for Newbies by Tiffani Angus and Val Nolan is published by Luna Press Publishing, priced £16.99.

In the Roman dialect the word ‘magnaccioni’ means people who eat well to live well. In Magnaccioni poet and author Anne Pia departs from familiar forms, creating a book of recipes, philosophy and well-being that reflects the culture of her native Southern Italy. Get your mouth watering and your mind racing with her recipe for the Easter Frittata below.

Magnaccioni

By Anne Pia

Published by Luath Press

Music

La Societá Dei Magnaccioni by Lando Fiorini

(Souvenir da Roma; Cantaitalia)

Com’e faccette mammete by Massimo Ranieri

(‘O surdato ‘nnammurato (Live)

Lifestyle and philosophy

There is little more exciting for me than a market overflowing with aromas, purposeful people intent on getting the best cut for dinner, or a cheese that matches what is in the cellar; with newly pulled lettuces bristling with freshness, cauliflowers in magnificent bloom, onions ochred, yellow or pale and silky, garlic plump and purple (sometimes flamingo pink) trailing over benches, crowding and bulging from wicker baskets; and peppers, large and curvy, red as lanterns; all these make me giddy with excitement. And I see myself living another life in a small Roman kitchen, or a small French town, bustling about with gigantic stock pots, working dough and tending marjoram, oregano, mint and some rosemary perhaps, at my doorstep.

Food is my constant life adventure. Between lovers and within family, it is interplay, bonding, enjoying the sweetness of familiarity brought by years. Food is flighty, often capricious on the stove and flirtatious on the chopping board, sometimes promising little and then to everyone’s surprise, giving all and more, making you, the cook, proud. Food is also theatre, a song that reverberates around your walls, a beacon of hope and promise for a gathering, a common language with which we can connect. It is an aesthetic, and a wondrous example of the beauty within and around us in our world.

Recipe: The Easter Frittata (Frittata Pasqualina)

For a family with healthy appetites and enough to return to later

18 eggs

150g of Sicilian, Calabrian sausage from an Italian food outlet

or cured Italian sausage

150g of diced bacon

150g of provola cheese, caciocavallo or mozzarella

Beat all the eggs adding salt and pepper.

Squeeze the uncooked sausage from its skin, chop it into cubes and fry with the bacon cubes.

Alternatively fry the bacon cubes and add the cured meat when the bacon is cooked.

Add the cheese, cubed, to the egg mixture.

When the meats are cooked, add the egg and cheese mixture to the pan.

On a medium flame, keep lifting and moving the egg around until as much egg as possible is set.

At this stage you can either continue to cook on the stove or put the frittata in the oven.

If you continue to cook on the stove top:

Invert the pan and do the same on the other side.

Invert the pan again, cover completely and extinguish the flame on the cooker.

You can check whether it is thoroughly cooked by inserting a fork in the middle of the mixture.

When well cooked through turn the frittata out and serve in wedges or cut across it to create rectangles.

And to Drink

Corvo Bianco, Duca Di Salaparuta from Sicily is a lively straw yellow wine that is worth seeking out. It is crisp, light and with a satisfyingly rounded flavour.

Should you prefer a red, Corvo Rosso, is like a Nero d’Avola in style, and stands up well to the richness of this dish. Ruby-red, full-bodied with aromas of dark morello cherries. This would be an excellent choice and a wine that I have enjoyed for many years.

Magnaccioni by Anne Pia is published by Luath Press, priced £9.99.

Even in summer, in Edinburgh you’re never far from a downpour. So it’s a good thing we have Mike MacEacheran on hand to help us out with a list of the best ways to spend a rainy day in Auld Reekie! Read on for just a few suggestions on how best to combat the capital’s unpredictable weather.

Rainy Day Edinburgh

By Mike MacEacheran

Published by Quadrille

Introduction

Densely packed with galleries, museums and world-class institutions, but also crowned by a skyline dominated by steampunk spires, steeples and the crags of a 340-million-year-old volcanic plug, Edinburgh is extraordinary whether you’re a first-timer or back for an extra helping. The setting itself is riddle-like, with a subterranean underbelly of webbed alleys and cobblestoned closes that zigzag through the Old Town like a giant game of snakes and ladders. Explore the wider cityscape from the New Town to Morningside to Portobello and beyond and you’ll also find a city of superlative castles (few know Edinburgh actually has three…) and scores of destinations where you can lose yourself amid the rich traditions and stories of a city that has had a disproportionate influence on the worlds of art, architecture, literature, music and more. If anything, this is a city that encourages notions of the fantastic.

All of this comes with a caveat, of course. Edinburgh has many nicknames – Auld Reekie (Scots for Old Smoky) and Athens of the North are two popular ones, for instance – but, perhaps, the most fitting is the Windy City. The capital is positioned between the North Sea coast and Pentland Hills, with the prevailing wind direction coming from the southwest and it brings with it unpredictable rain showers and glowering storm clouds. Which is to say hiding out in museums and art galleries on a rainy day is an art form here.

For food and dining out – the purest expression of any city – avoid the menus of haggis and out-of-the-freezer fish and chips on the Royal Mile and around the Grassmarket in the Old Town, and dig deeper into city life by heading northwest to Stockbridge or northeast to trend-setting Leith, which has both Edinburgh’s most vibrant grassroots scene and more game-changing haute cuisine than anywhere else in Scotland. And the perfect partner to all that? Drink, of course. This is the home of single malt whisky after all – and Scots are equally proud of their hospitality and gin- and beer-making heritage – and nowhere in the country has as many buzzy cocktail bars and lavishly-appointed pubs as Edinburgh. You might go from a Victorian-era backstreet boozer in the Old Town to the slightly-macabre subterranean streets of the Cowgate for a night of cocktails and decadence. Equally satisfying is a tour of the city’s fledgling indie craft brewers.

Whether you’ve spotted this book while sheltering from a rain storm (all too common on the Scottish east coast, if truth be told), or are keen to get ahead with booking must-visit restaurants and museum exhibitions before an upcoming trip, consider this guide an introduction to a capital city that, though compact and easy to navigate, never stops to catch its breath. Either way, I hope these recommendations will reassure you that the Scottish capital is as brilliant a place to be on a rainy day as it is when that giant orange-yellow orb in the sky appears.

Dovecot Studios

Dovecot Studios

This working tapestry studio and landmark design centre has more than 110 years of history and was first based in the western suburb of Corstorphine before moving into this former public swimming pool. That gives it a well-lit, graceful vibe and it’s a thrill to walk around the multi-coloured hangar and see craftspeople and master weavers bring works of art to life before your eyes from the first-floor viewing balcony (check the opening times before you visit). You can browse and linger in the gallery, café and shop, while there are tapestries and rugs to liven up your own house or apartment and – time your visit wisely – and you’ll be able to join a rug tufting or life drawing class, embroidery or bookbinding workshop, or hands-on, fleece-to-fabric experience with one of the looms.

10 Infirmary Street, EH1 1LT dovecotstudios.com

@dovecotstudios

The Writers’ Museum

Whether you’re a bookworm or just getting to grips with the disproportionate influence of Edinburgh writers on the world of literature (J.K. Rowling, Irvine Welsh, Ian Rankin, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Muriel Spark to name a few), a visit to this free museum off the Royal Mile is worth a few hours of your time. For context, the city was the first to be named a UNESCO City of Literature and the museum is a tribute to three colossi of the art that have long left critics flailing for superlatives: Scotland’s national bard Robert Burns, Rob Roy and Ivanhoe author Sir Walter Scott, and Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde wordsmith Robert Louis Stevenson. Inside, you’ll see first editions, inkwells, portraits, personal effects, a printing press and Burns’ writing desk. Outside, meanwhile, on Makars’ Court, you’ll find the Edinburgh equivalent of the Hollywood Walk of Fame: a space of inscribed flagstones that celebrate a who’s who of Scottish writers.

Lawnmarket, Lady Stair’s Close, EH1 2PA

edinburghmuseums.org.uk

@museumsgalleriesedinburgh

Golden Hare Books

Golden Hare Books

How many bookshops are cosy enough to have a wood-burning stove fireplace set in-between the packed shelves of paperbacks and novels? Golden Hare Books is such a find and one that makes a perfect place to dry out in the company of a fine book – the specialities here are independent-published titles and carefully-curated fiction and non-fiction tomes from the book-crazed staff; as the saying here goes, ʻall our books are importantʼ. In business since 2012, it remains a thrill to seek out your new favourite while sheltering from the rain – though with more than 2,000 titles from travel to cookery to science-fiction to kids’ picture books, you might be here longer than you think. Also impressive is the calendar of events, which runs the spectrum from author talks and book signings to workshops and book clubs.

68 St Stephen Street, Stockbridge, EH3 5AQ

goldenharebooks.com

@goldenharebooks

Cairngorm Coffee

Cairngorm Coffee

With countertop-to-ceiling windows, a crossroads location perfect for meet-ups and a curated coffee menu, this minimal but beloved neighbourhood café in the West End is invariable packed with good reason. Since the company started in the wild expanses of Cairngorms National Park (an unlikely destination for a roaster, admittedly), Edinburgh has become the coffee brand’s spiritual home – nowadays there are two other locations in the capital. This Melville Place outpost is the original and it’s the quintessential coffee drinker’s establishment: bar stools meet large windows, a sleek server’s counter tenders a cake, brownie or sandwich to go with your latte or espresso, and it’s a retreat from the often wet and grey reality outside; here, the colour scheme is brilliant white and warm pine.

1 Melville Place, EH3 7PR

Other locations: New Town, St James Quarter

cairngorm.coffee

@cairngormcoffeeco

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

A walk to this unmissable art museum with two distinct personalities – Modern One and Modern Two lie directly across the road from each other – stirs an appetite for art, and you’ll be rewarded with works from such top-notch masters as Picasso, Tracey Emin and Andy Warhol. In the permanent collection, native son of Leith Eduardo Paolozzi’s sculpture studio has been recreated, while the tutored eye will recognize works by the likes of Henri Matisse, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí and Roy Lichtenstein amid a collection that hangs heavy with Scottish talent. The rain means you’ll have time to explore the temporary exhibitions at leisure, but you’ll likely have to come back under brighter skies to explore the grounds, both of which are ambushed by dozens of sculptures and installations. What you won’t be able to miss, though, is Charles Jencks’ swirling landform that’s been terraformed into existence on the front lawn.

75 Belford Road, EH4 3DR

nationalgalleries.org

@natgalleriessco

Edinburgh Printmakers

For a glimpse of gentrification at its finest, come to Fountainbridge: it’s almost unrecognizable to how the area was a few years ago and design lovers have taken to the Edinburgh Printmakers with whole-hearted enthusiasm since the art studio moved into the neighbourhood from its former headquarters in the New Town back in 2019. This new lease of life in a beautiful heritage building vacated by a rubber company and brewery has seen the studio go from strength to strength and walk-ins are welcome to explore the eye-popping exhibitions, vegan café and shop. Courses run from lithography to screen-printing, while the multi-level balconied space is a mixture of open-access studios for invited artists and publishing partners and viewing galleries for you to witness world-class printing in action.

Castle Mills, 1 Dundee Street, EH3 9FP

edinburghprintmakers.co.uk

@edinburghprintmakers

Valvona & Crolla

Valvona & Crolla

Who are Valvona & Crolla? For the uninitiated they’re Benedetto Valvona and Alfona Crolla, two immigrant Italian merchants who set about importing salamis, cheeses and wine for the fledging Italian communities that moved to eastern Scotland in the late 1930s. Their legacy is a cave of goodies still supplied by small artisan producers from their homeland and the delicatessen is now the country’s oldest– and one of its most celebrated. From humble roots, the store has become the headquarters of a mini empire – the family behind the deli now run a number of other Italian cafés and bars throughout the city – yet this original still captures the imagination best, with its diverse collection of aged Parmesans, pestos and pasta flours, honeydew honeys, truffle creams and hand-sliced prosciuttos. Besides the treasure-trove delicatessen, there’s a café-restaurant, bakery and venue that’s used throughout the Fringe Festival every August.

19 Elm Row, New Town, EH7 4AA

valvonacrolla.co.uk

@valvonacrolla

The Portobello Bookshop

Seaside Portobello – aka Porty, to locals – is for sunny days, but wet ones bring book lovers to this beautiful tribute to the written word in all its forms. The store was formerly a fishing tackle shop, not that you could tell nowadays, and the main space has the expansiveness of a library, with bumper floor-to-ceiling shelves, but the essence of a chatty community hub. The focal point is the cash register flanked by four Romanesque columns, then behind that are several other brightly-lit galleries for novels, coffee table books and children’s stories. Author events and talks are a major lure for the community – and certainly worth checking out if you’re in the neighbourhood at the right time.

46 Portobello High Street, Portobello, EH15 1DA

theportobellobookshop.com

@portybooks

Rainy Day Edinburgh by Mike MacEacheran is published by Quadrille, priced £12.99.

An epic fictionalisation of the hunt for North Sea oil on Scotland’s East Coast in the 1960s and 70s, Richard T. Kelly’s expansive new novel tells the story of this pivotal moment in our country’s history through the lives of five young men, each with their own place in a changing society. We caught up with Richard here at BooksfromScotland to ask him about his new novel, his craft, and hypothetical dramatisations.

The Black Eden

By Richard T. Kelly

Published by Faber & Faber

Congratulations, Richard, on the publication of The Black Eden. Could you please tell us a little bit about what readers can expect from the book?

Thank you! With this novel I’ve tried to dramatize the great, true story of the hunt for oil in the North Sea during the 1960s and 1970s. The aim, really, was to present in a compelling way what finding the ‘black gold’ did to different people’s lives and relationships across Scottish society – how it transformed livelihoods and life-chances in Aberdeen and the north-east, how it turbo-charged Scottish industry and finance, too. Of course, alongside the benefits there were human and material costs, things that would be sorely contested both within Scotland and in its relations with the wider UK – and that is part of my story, too. It’s all recent history, and we feel its effects today, and will continue to. The characters in the novel are made-up, but still I hope Scottish readers might ‘recognise’ one or two of them from the contexts of their own lives, maybe.

While a work of fiction, The Black Eden follows a real historical timeline of the discovery of North Sea oil. What interests you about this part of British history and all its socio-political implications?

What I love about real-life historical-political subject matter is that it’s full of dilemmas – situations where people have to confront a really tough, conflicting choice between options, where there’s not one which is obviously correct. So, you’re forced to choose, and to take whatever are the consequences, even those you couldn’t foresee them – and that to me is inherently dramatic.

Back in the 1960s the UK badly needed oil to relieve its chronic balance of payments, and Scotland, because of the stratigraphy of the North Sea, became the laboratory for a grand experiment. The UK had already got onto the road to becoming a post-industrial economy – service-based, consumer-focused – and, ultimately, oil revenues would help that process further along. Extracting the crude oil from under the seabed, though, was incredibly hard, dirty, dangerous industrial labour. Once the oil was proven, it gave a terrific spur to those Scots who favoured independence for the nation – because they could see, albeit too late, a means by which Scotland might have been hugely rich had it sought independence sooner. ‘It’s Scotland’s Oil’ became the famous SNP slogan – but it wasn’t. The oil had been struck and exploited within a context made by the union, an agreement that couldn’t just be unravelled. From that moment, though, I’m sure it became sharply apparent to a lot of Scots just how much Scotland didn’t have its own head in these great matters. At the same time, everything that Scottish people went through and contributed to this colossal endeavour meant they emerged from it, I think, with a new assurance about what Scotland might achieve with a more diverse economy, working for new kinds of livings.

How do you strike a balance between historical accuracy and fictional storytelling?

If you write along the lines of things that actually happened, you’re always trying in some way to borrow a bit of plausibility – also a bit of profundity – from the realness of those events. But the challenge is to recast those events and dramatize them well, perceptively, so as to offer the reader insights they mightn’t get from the history books. The great German writer Bertolt Brecht said some especially brilliant things about ‘history plays.’ He observed that, if we write in that area, we want the pleasure that comes both for us and for the reader by dealing with “a piece of illuminated history” – meaning a certain kind of investigation of the past, or even an argument with the past, where some sharp new light gets shed upon it. But it has to be stressed that pleasure is the thing – fictional storytelling can’t be some arid academic exercise. Brecht goes on to argue that all of us, young and old alike, enjoy ‘stories of the rise and fall of the mighty, of the cunning of the oppressed, of the potentialities of men.’ And the historical record certainly offers that material for writers to play with!

How did you approach the research for this book? Could you tell us about one particularly interesting story or person that you came across while exploring the historical background of the novel?

Essentially I spent a lot of time just wandering round Aberdeen, and up north in Easter Ross, Nigg and Portmahomack, trips that I really savoured. Edinburgh I knew well enough from previous time spent. But then there was a lot of trawling of old print and photo archives, because to a degree the real North Sea ‘gold rush’ moment of the 1970s in Scotland is now a lost world – you can struggle to find enduring physical markers of it.

I heard so many stories that influenced the direction and tone of the novel, as well as some little touches in the margins. This is legendary in petroleum circles, but in the 1960s a top geologist at one of the major oil companies was so unconvinced by the prospects for North Sea drilling that he swore he would literally drink any oil that got found – and that encapsulated for me just how improbable and ill-starred the whole venture seemed at first.

On an earthier level, I enjoyed the tales of when BP established the huge deepwater construction yard in Nigg Bay to build the massive steel jackets for oil platforms to be hauled out to sea. I was fascinated by the Wild West aura of that – how labourers were drafted in to the north-east from all over, so many that they had to be given bunks aboard an old decommissioned Greek tourist ship. And where all these lads could go for a drink was a serious matter, but the one local hotel bar got so busy that the owner had to have an extension built, just for these thirsty workmen.

It did intrigue me, too, that in 1972 the US actually despatched a hugely seasoned diplomat with Middle East oil industry experience to be their Consul General in Edinburgh, as if to watch over what North Sea oil might do to the national question. I knew straight away that I wanted to do a version of that in my novel.

In addition to being a novelist, you have written scripts for stage and screen as well as books on film and filmmakers. If The Black Eden were adapted into a film or TV series, who would you love to see in the leading roles?

That’s a lovely question. It’s like fantasy football, but I could imagine the young Dundonian actor Stephen McMillan being great as Aaron Strang, the petroleum geologist; likewise Jack Lowden as Joe Killday, the Aberdeen trawler fishing scion. I could see Kirsty Findlay being terrific as the book’s heroine, the welder Evie Charlton. Scotland has so many superb actors across the generations, so I’d certainly hope there’s promising material for them here.

What do you hope readers will take away from this book?

Above all, I hope readers will have felt themselves caught up in an involving human story – that all that the characters go through as the plot progresses, the various dramas about love and work and family, will feel true and affecting. But I’d also be pleased if readers felt some renewed fascination with our recent history, that big-picture story of society and economy and industry, and all the human endeavour that went into it – and that they might even bear some of the novel’s themes in mind when they consider some of the vital societal issues confronting us now, particularly to do with how we get the energy we need as we look toward a low-carbon future.

Lastly, what are you looking forward to reading next?

My summer reading will definitely involve getting round to Alan Warner’s Nothing Left To Fear From Hell, to Don Paterson’s memoir Toy Fights, and to Kick the Latch by Kathryn Scanlan. Looking ahead, I’ll be pre-ordering what looks to me a really promising non-fiction book: Not the End of the World: How We Can Be the First Generation to Build a Sustainable Planet by Hannah Ritchie.

The Black Eden by Richard T. Kelly is published by Faber & Faber, priced £20.00.

In his latest book, Footprints in the Woods, celebrated nature writer John Lister-Kaye takes the Mustelidae family as his focus, observing the comings and goings of otters, badgers, weasels and pine martens around his home at Aigas. In this exclusive interview, David Robinson speaks to the man dubbed ‘Scotland’s high priest of nature writing’.

Footprints in the Woods

By John Lister-Kaye

Published by Canongate

I first interviewed John Lister-Kaye 20 years ago for a feature in The Scotsman. Back then, not everything in print made it onto the internet, and as my interview didn’t, I’m relying entirely on memory to recall the afternoon he showed me round his conservation and field study centre at Aigas, near Beauly. And in my memory, it’s filed away as one of life’s golden days.

To understand why, I’d better explain a few things. First of all, I’m a townie by birth, background and (I suppose) inclination, embarrassingly ignorant about the natural world, and in almost every other way John Lister-Kaye’s antithesis. To take just one example, he’s inherited a baronetcy which goes all the way back to 1378, and I have not. To take another, he’s built up his eco-tourism business from nothing to something worth millions to the local economy and I have not. And when I met him, he’d already been a published writer for 30 years, lectured on the natural environment all over the world, held high office in practically all the relevant national organisations, and was just about to be awarded an OBE, whereas I … well, you get the picture.

Another thing: I have always liked mavericks, people who hoick themselves out of pre-ordained grooves and tread their own path. And JLK was and is a classic case – in his twenties, walking away from a management traineeship to work alongside naturalist and Ring of Bright Water author Gavin Maxwell, and in his thirties setting up the first field study centre in the Highlands in the face of considerable local and bureaucratic scepticism.

How he transformed a ruined 19th century Highland estate into a vibrant eco-tourism business was part of the story of Song of the Rolling Earth, the book I was interviewing him about 20 years ago. What readers mainly noticed about it was the lyricism of the writing and the love of the natural world which powered the whole enterprise. He could easily have written a bombastic book taking potshots at the planners who recommended he open a caravan park instead of a field study centre or the local minister who lambasted him for encouraging people to defile the Sabbath by looking at wildlife, but that would have been petty, and the dream on which Aigas was built was bigger than that.

But while I’m sure he answered all my journalistic questions about Aigas (these days it is visited by up to 7,000 schoolchildren from 162 Highland schools and up to 1,000 paying guests on a whole variety of courses run by the 26 staff), what made that day stick in my mind was everything about the estate that couldn’t be so easily measured. Walking with him through his woods to the Illicit Still, the cosy lochside hut where he writes. Listening as he told me which bird I could hear, which animals had passed by in the night, what they had eaten, where they were going, where they would sleep, which predators they feared most, and where and when he would expect to find them. The world – or at least his world – opened up and his book came to life in front of me.

Twenty years on, he is back with another book, and because it’s called Footprints in the Woods it made me think back to the first time we met. In the intervening years, you may have noticed, nature writing has spent a long time in the psychiatrist’s chair – any day, you almost expect to see a book about how a badger/blackbird/barn owl saved a writer’s sanity – but Lister-Kaye doesn’t do that here. This is pure, unadulterated, old-school nature writing at its best, the focus entirely on animals – to be specific, mustelids (weasels, otters, badgers and pine martens) – rather than the writer’s psyche.

‘We have all of them at Aigas,’ he says when I chat to him again, ‘though if we walked through our woods again your chance of seeing a weasel are virtually non-existent.’ What sparked his new book was one March day two years ago when, out of the corner of his eye, he caught a glimpse of something scurrying near a dry-stone dyke. He thought it was probably a weasel, but because it was lockdown and the field centre was shut, kept going back there to make sure, and to find its nest.

‘I went back for 17 days, all through the frost, rain and snow, sitting down for hours at a time before I saw it. You need to be able to be still for a long while to see many things in nature, and these days that’s increasingly rare. Going into one of our hides in the evening is a two-and-a-half-hour stint and you may see nothing at all for the first half hour or 40 minutes before the animals – pine martens, badgers – come in and start to feed and we have real difficulty getting people to sit still. It’s not just young people, it’s all ages. They’ll fidget, fiddle with their phones, change lenses on their cameras, and we try very hard – and as gently and politely as we can – to sit still and watch the wildlife in front of them.’

In Footprints in the Woods, he writes at length about stillness. We can’t do anything about our scent, he says, but animals know that humans are loud and move about, so if we don’t act like that we can fool them into ignoring us. To be perfectly still is a denial of self and requires people to be fully aware of their surroundings and merge into them in a way he can’t quite explain but clearly can do himself. As he writes: ‘Frolicking badger cubs and pine marten kits have blundered into my feet, birds have landed on me, deer have often grazed right up to me, weasels and stoats have busied about around me, brown hares have stumbled into me, red squirrels and wood mice have scuttled over me, and just once, in our own Aigas pinewood, a wildcat stalked silently past three feet away carrying a leveret in its jaws.’

He tells me another story about stillness, one that isn’t in the book. In 1969, he was shooting rabbits on Pabay, the island just off Broadford on Skye, in order to feed the wildlife menagerie Gavin Maxwell was assembling nearby, when he came across a fox in a snare with wire wrapped round its body so tightly he was unable to free it. ‘So I called Gavin, and he sat down within biting distance of this fox which was in great pain and talked to it in a low voice for probably six or seven minutes. Very slowly, he reached forward and – again, within biting distance – began to untangle the wire. The fox never turned on him, and never made any aggressive moves at all, so he could untangle the wire and the fox ran off. I’ve never forgotten that. He really did have remarkable rapport with animals and it’s not surprising that this gripped the public imagination when he wrote Ring of Bright Water.’

He denies that he has the same level of skills, but I’m not so sure. In Gods of the Morning, he wrote about Squawky, a pet rook he looked after at prep school in Somerset and gave away to a woman who worked in its kitchen. A full quarter of a century later, he was in the area and called in to see her. Astonishingly, Squawky was still alive, seemed to recognise him and flew over to his arm.

There’s a similar story in Footprints in the Woods, and it probably goes a long way towards explaining why, two years ago at the age of 75, he was quite happy to sit near that dry-stone wall for so many hours at a time waiting for the weasel to pop out. When, six decades ago, he was at boarding school, he found a weasel kit left alive after a badger had killed its siblings. He named it Wilba and raised it for weeks on end. Wilba slept in a box next to his pillow, lived in the pocket of his tweed jacket or inside his school desk, and was fed through a pipette on diluted milk and glucose till he was old enough to be released. A year later, he went back to that spot with his father. After they sat down and ate sandwiches, Wilba ran up to him, briefly sat on his knee and ran off again.

Debrett’s have John Lister-Kaye down as the eighth baronet in a family knighted back in Plantaganet England, and certainly the banqueting hall at Aigas is chock full of aristocratic ancestral portraits, but that’s just an accident of birth. Being the magus of mustelids, friend to Wilba and Squawky, and Scotland’s greatest living nature writer isn’t.

Footprints in the Woods: The Secret Life of Forest and Riverbank by John Lister-Kaye is published by Canongate, priced £16.99.

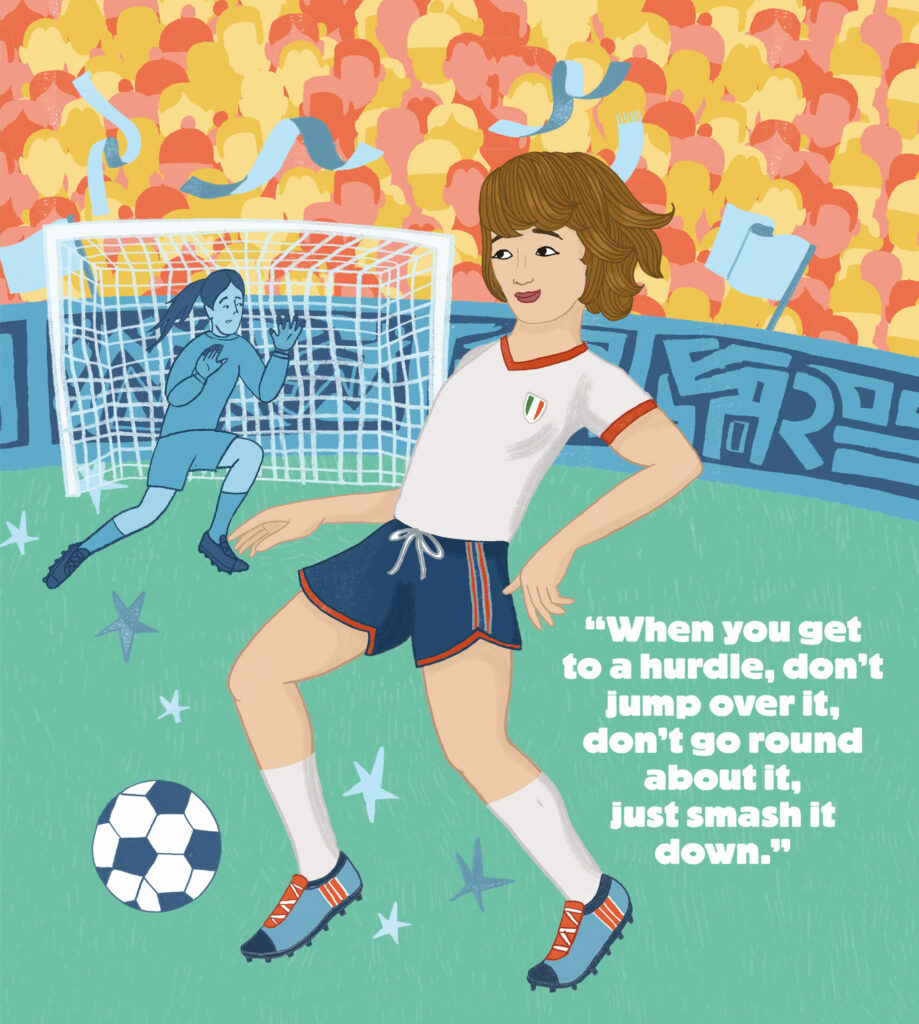

Spectacular Scottish Women is an inspiring new collection of biographies written for young people by Louise Baillie, with vibrant and dynamic illustrations by Eilidh Muldoon. A fascinating and uplifting celebration of iconic women from Scotland’s past and present, it introduces young readers to a host of inspirational women: from authors to athletes, scientists to singers and queens to campaigners. This extract shines a spotlight on pioneering footballer Rose Reilly, who was born in Kilmarnock in 1955.

Spectacular Scottish Women

By Louise Baillie and Eilidh Muldoon

Published by Floris Books

Smashing Down Hurdles

Rose Reilly – A Spectacular Scottish Football Hero