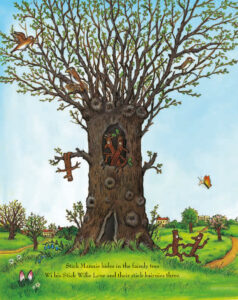

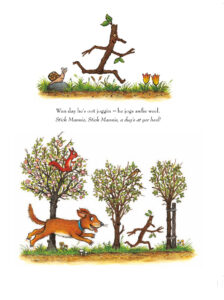

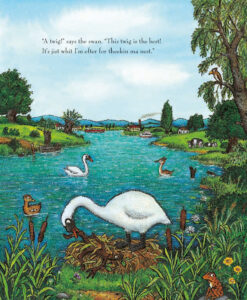

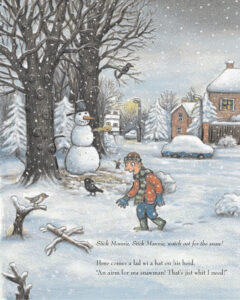

After his morning jog goes awry, the Stick Man’s epic journey begins to unfold, through the wilderness and the seasons of the year. Another children’s classic from Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler, you can preview some of the Scots version, translated by James Robertson, below.

Stick Mannie: Stick Man in Scots

By Julia Donaldson, illustrated by Axel Scheffler, and translated by James Robertson

Published by Itchy Coo

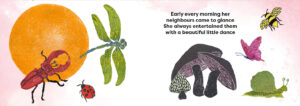

[Images 1-5] Stick Man © Julia Donaldson, Axel Scheffler, 2008 Scholastic Children’s Books. All rights reserved

Stick Mannie: Stick Man in Scots by Julia Donaldson, illustrated by Axel Scheffler, and translated by James Robertson is published by Itchy Coo, priced £6.99.

In Ever Dundas’ new novel, HellSans is a typeface that is enforced by the government as the ultimate control device. Those allergic to it find themselves not only unsupported, but actively persecuted, forced into the outskirts of the city. Having created this dystopian tale that will stay with you long after the last page, Ever Dundas talks to BooksfromScotland about her favourite books.

HellSans

By Ever Dundas

Published by Angry Robot Books

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

My first memory of reading is struggling to read. In Sunday school we all had to read a passage from the Bible and I couldn’t. The other kids were horrible to me (how very Christian of them). I was never formally diagnosed with dyslexia but all the things I struggled with point to that. Eventually I got some extra help, and when I finally learned to read I devoured books as if they were life-giving sustenance.

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest book HellSans. What did you want to explore in writing this book?

HellSans is set in an alternative dystopian UK, where the Inex, a cyborg doll-like personal assistant, has replaced the smartphone and the population is controlled by its ‘bliss’ reaction to HellSans, the enforced, ubiquitous typeface. But there’s a minority who are allergic to the typeface: so-called ‘deviants’ who are forced to live in ghettos or on the streets.

The story follows two protagonists, Jane Ward and Dr Ichorel Smith. Jane is a queer woman, and she’s CEO of the company that develops the Inex. She’s powerful and in league with the government until she falls ill with the allergy. Losing her charmed life, she languishes in the ghetto until her story collides with Icho.

Icho is a queer woman who has a HellSans allergy cure and is on the run from the government and the Seraphs who all have their own agenda for the cure (the Seraphs run the ghetto and are ‘terrorists’ or ‘freedom fighters’ depending on your viewpoint).

The book is in three parts, and the first two parts, ‘Jane’ and ‘Icho’, can be read in an order of the reader’s choosing.

HellSans was influenced by my experience as a disabled person living under a Tory government that was investigated by the UN for human rights violations against disabled people. I experienced how quickly and easily you can fall through the cracks of capitalism, and I got a taste of the dehumanising punitive benefits system. Even with all the support I had, it almost broke me. There’s also little in the way of medical or social support and it’s a fight to access what little there is. Ableism and health supremacy permeates society and no one cares if disabled people suffer and die.

I funnelled all that into HellSans, but I didn’t want it to be worthy and preachy; it’s first and foremost a sci-fi thriller. I want readers to be swept up in the story, so I hope I’ve achieved that.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography by Julian Young. I read it every morning as I had breakfast and it was such a soothing way to start the day. I loved travelling with Nietzsche each morning, and I loved the challenge of the thought experiment that is the eternal return. But more than informing how I see myself, it’s informed the core of my third novel.

The book as . . . an object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

We have so many beautiful books, it’s hard to choose. But I think I’ll go with Emil Ferris’ My Favourite Thing Is Monsters, as the art is so entrancing.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

The Catcher In The Rye. When I was a young teen, my sister Rachel gave me her tatty copy which had all her scribbles in the margins, passages underlined.

I don’t get all the recent social media hatred of it, just because Holden isn’t a particularly likeable character. Why do characters have to be ‘likeable’? Or even relatable? I loved it as a teen and reread it as an adult and still love it; even now, I find the passage where he talks about being the catcher in the rye very moving.

My sister also introduced me to 1984, Brave New World, American Psycho, and Equus; you wouldn’t judge any of these books on the likeability of the characters.

Rach died a few years ago. I wish I’d had the chance to tell her what an impact she had on me as a person and a writer.

The book as . . . rebellion. What is your favourite book that felt like it revealed a secret truth to you?

Groosham Grange by Anthony Horowitz. It blew my nine-year-old mind because the bad guys won – but were they the bad guys?

What I’d been taught was bad wasn’t necessarily bad. The people I thought were bad – were they really? The things I was told to be afraid of – were they really the things to fear? As the Groosham Grange headmasters explain to the protagonist: ‘All right, I admit it. We are, frankly, evil. But what’s so bad about being evil? We’ve never dropped an atom bomb on anyone. We’ve never polluted the environment or experimented on animals or cut back on National Health spending.’ Beware the bankers, beware the politicians – don’t get distracted by those they call monstrous, don’t get distracted by their scapegoats.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi. I’d love to visit the House.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

I’m not sure what I’m reading next from my ridiculous ‘to read’ tower, but I’m very much looking forward to Mat Osman’s The Ghost Theatre which is out May 2023. I had the pleasure of reading an early draft during a miserable lockdown January when I was dealing with a friendship imploding; it brought escape and cheer. I’m looking forward to holding it in my hands in book form and immersing myself in that world again.

HellSans by Ever Dundas is published by Angry Robot Books, priced £9.99.

Richard Holloway is one of the country’s most beloved thinkers, and he has turned to poets and writers for guidance and solace as life has gone on. David Robinson dives into The Heart of Things, this book created to offer lessons – in Richard’s words – who ‘know best how to listen, and teach us to listen’.

The Heart of Things

By Richard Holloway

Published by Canongate Books

Sixty years ago, when I was eight, I travelled from one end of the country to the other to meet the man my mother’s sister had married. Uncle Jack was everything our family wasn’t – upper-class, rich, received pronunciation, effortless manners. An elderly judge, he’d lost an eye in the Irish War of Independence (he was on the wrong side) and the left lens of his glasses was an opaque grey. My aunt – who was much younger than him and beautiful – warned us that he thought children should be seen and not heard and gave me emergency lessons in cutlery etiquette before introducing me to him.

They were only married for a short while before he died, so I never really knew him. He left almost everything to his daughter from a long-ago marriage, but my aunt inherited his books. The year after he died, I came across something he’d written on the flyleaf of a poetry collection. ‘How cruel it is,’ I read, ‘that the old can still appreciate beauty.’ I don’t remember a single thing he said to me, but those words have stuck in my mind ever since.

I was still a child, so I didn’t understand them as completely as I do now that I am nearly Uncle Jack’s age. But I understood enough. My one-eyed uncle was no doubt frightening if you were a prisoner before him or a child at his table who wasn’t sure how to use a fish-knife, but this poetry book – I can’t remember its title – had clearly unlocked something else within him. He was hurt, this small but apparently impervious pillar of the Establishment; hurt by looking back in old age at the tormentingly evanescent beauty of life.

That particular sentiment is at the heart of Richard Holloway’s The Heart of Things too – his thirty-third and, he keeps threatening, final book, out in paperback this month, just ahead of its author’s 89th birthday. There is, though, far more to it than just an old man’s howl of regret. While most poetry anthologies just give you the poems, this one gives you the later chapters of a spiritual autobiography too.

The earliest ones – about faith, obedience, and the surrendered life of monk and subsequent minister – were well covered in his wonderful autobiography, Leaving Alexandria. Even there, though, poetry had its place. When I first read it, I skipped past the epigraphs and assumed that the title was entirely straightforward; Alexandria in the Vale of Leven was where Holloway grew up, where Christianity first enchanted his teenage mind, and from where he left to be a novice monk in England. Only now, reading his anthology, do I realise that it also came from C. F Cavafy’s poem ‘The God Abandons Antony’, an extract from which was one of the epigraphs I’d overlooked and which is also included here:

At midnight, when you suddenly hear

an invisible procession going by

with exquisite music, voices,

don’t mourn your luck that’s failing now,

work gone wrong, your plans

all proving deceptive – don’t mourn them uselessly:

as one long prepared, and graced with courage,

say goodbye to her, the Alexandria that is leaving.

Mark Antony’s plans have all gone wrong: he has been abandoned by Bacchus, is about to lose Alexandria and, by implication, Cleopatra, and faces defeat at the hands of Octavius. Holloway discovered the poem, he says, at just the right time – ‘when God was abandoning me or I was abandoning God’ – and it gave him courage.

Mostly, though, the poetry and writing he chooses have other messages. Because he no longer looks forward to the ‘sure and certain hope of the resurrection to eternal life’ (as he points out, ‘certain hope’ is a bit of a contradiction), he often finds himself looking backwards at his life, as from the stern of a ship at its ever-widening wake. In such circumstances, melancholy is inevitable, so no wonder it afflicts so many writers. Yet, as he says, maybe he’s got that the wrong way round and it is melancholy that makes them writers in the first place. But if it is, and if everything (including all poetry) will be lost to death, why bother writing at all? Why not just be melancholic? The answer – the bravery, elan, wisdom, regret and defiant celebration of life to be found in poetry – is precisely why Holloway finds it so necessary.

His book’s subtitle is ‘An Anthology of Memory and Lament’, but although Holloway claims all he is doing is following Montaigne in ‘making up a bunch of other men’s flowers’, he is actually doing quite a lot more. Not only does each chapter end with a few lines of his own unpublished poetry, but the anthologised pieces aren’t just lumped together under loose themes but brought together in a persuasive line of thought. I nearly wrote ‘thesis’, but that would be wrong, because there’s nothing narrowly dogmatic about the book, so you’ll find for example John Betjeman writing about meeting death with hope, just as readily as Edna St Vincent Millay on facing it with defiance.

For all that, there is a tide of ideas running through this book, and they do generally run in the same direction – towards the last things, death itself, and what we might miss most about life. Yet anyone who has ever heard Holloway talk about such matters, whether from the pulpit or book festival stage, knows that he does so with a wisdom and eloquence that can be strangely uplifting. It’s the same here. At the end of an extract, Holloway will often seize on a particular phrase and underline it by repetition (‘every poem, in time, becomes an elegy’ – Borges), or bring the whole poem back as part of another argument altogether, as he does with Mark Doty’s poem ‘Migratory’. This is an effective technique, constantly drawing the reader into a deeper understanding. It also helps that there’s not a whiff of waffle or a drop of ‘poetry-speak’, just crystal-clear exposition. I wish there could be more books like this, more personal, well thought-out and beautifully written anthologies, though that may well be another way of saying I wish there could be more people like Richard Holloway.

There is, as I have mentioned, a lot of regret in this book: indeed Holloway admits that he loves the word itself (‘Like a good poem, it is its own meaning. Just say it softly: REGRET’). That much my Uncle Jack might have known all about. But towards the end, after the Cavafy poem, the book’s tone subtly changes. Writing about forgiveness (‘Jesus thought the unforgiven and unforgiving life were not worth living’), he points out how it can bring about ‘a certain lightness of being in spite of all that crushing weight of all that history pushing into and through us. Transcendence is the word.’

He concludes with a poem of his own that makes this very point. After tracking the formative memories of his life, it ends like this:

Now as my own life

spools its last reel,

I’m still not sure

if Someone was behind it,

like the projectionist

In the old picture houses

I went to and loved

as a boy.

Maybe at The End,

somehow,

I’ll know.

But wasn’t it great,

the show, I tell myself,

as the lights come up

and the curtains

start to close?

It was, it WAS!

AMEN.

The Heart of Things by Richard Holloway is published by Canongate Books, priced £10.99.

Tom Morton has travelled the world in search of the finest drams that the world has to offer; Holy Waters is his journey to the spiritual heart of whisky, sake, rum, and many more drinks to list. Revelling in the lore and mysteries, the relationships between human and landscape and beyond, it’s a celebration of cultures and artisan craft. Read an extract from the book below.

Holy Waters: Searching for the sacred in a glass

By Tom Morton

Published by Watkins Publishing

Largs is a small holiday town on the Firth of Clyde, about 30 miles from Glasgow, and it has been one of my favourite places since I first tasted home-made Italian ice cream and smelled the tang of salt, vinegar and fishy chip fat on the evening air.

I have never consumed an alcoholic drink in Largs, but I have worshipped in the local Gospel Hall, sung choruses at open-air meetings and eaten large quantities of Nardini’s ice cream and fish and chips, washed down with Barr’s Irn Bru. I have gazed at The Pencil, the monument to Scottish King Alexander III’s defeat of King Haakon of Norway’s forces in 1263, the battle that brought to an end Viking harassment of Scotland’s mainland, though not Norse influence over the islands.

Vikings are still part of Largs’s lore and street geography, pub names and touristic mythology. But long gone is the item that planted the romance of the Vikings in my head and heart as a youngster – the gigantic facsimile of a Norse war galley that used to jut from an Art Deco building that was once the 1300- seat Viking cinema. We kids would shriek with excitement each time we passed that fake boat’s ferocious-looking dragon’s head prow, but before long the building was the headquarters and bottling plant of J H Wham and Son, who produced a truly horrible blend of sweet South African wine and Scotch Whisky called Scotsmac. It was a favourite of schoolboys and girls on an illicit bender as it was cheap and effective; alcoholics liked it too. In fact, it was not unlike the much mentioned Buckfast Tonic Wine or other electric soups of Scottish industrial culture. It was affectionately known as Wham’s Dram or sometimes Bam’s Dram.

Scotsmac is no longer available for sale. It had gone through several owners by the time it vanished from the cheaper British supermarkets’ shelves in 2018, and it’s 15 per cent alcohol, viciously hangover-inducing axe-blow to head and heart, thankfully, became a thing of the past. I once conducted a tongue-very-much-in-cheek ‘guided tasting’ that involved Scotsmac, Buckfast Tonic Wine, Irn Bru and English St George’s Whisky. It’s fair to say that the audience left discombobulated and desperately seeking a proper drink.

And that was it for me and Vikings really, once childhood has departed. Or so I thought. Then, for reasons spelled out in two other books, I ended up living in the Shetland Islands, that northernmost of British archipelagos halfway to Scandinavia, and Vikings came rampaging back into my life.

Holy Flight – Tasting Notes

Lerwick Brewery Blindside Stout

Founded in 2012, the Lerwick Brewery is fairly new, and has been the most northerly brewery in the UK since the closure of Valhalla in Unst, Shetland’s northernmost island. This is my favourite of all their beers; it’s a highly successful dark IPA that conjures up for me memories of the night in Cork when I encountered Murphy’s Stout for the first time.

Colour: Dark ruby brown

Nose: Malty and dark with lots of wedding-cake fruitiness.

Palate: Lighter than you’d expect from that blackness, roasted nuts and burned toast. It has a great deal of character.

Finish: Small bubbles, so doesn’t ransack your tastebuds; leaves a fairly smoothe aftertaste.

Scapa Skiren Single Malt

Skiren is Old Norse for the sparkling summer light you get in Orkney, where this whisky comes from. The Scapa distillery is right next to the sea, not too far from its competitor Highland Park in Kirkwall, and its products have often been dismissed as less characterful than its better-known local cousin. Notably by myself. Recently, I bought a bottle in the community shop that sits right in front of the St Rognvald Hotel, and I have to say I was very impressed.

This has been aged only in ‘first fill’ American oak (that would be barrels bought in kit form from the USA, where it is illegal to re-use barrels that have had whiskey in them previously) and it has a delightful, supple smoothness, lacking the sweet sherry oak notes of Highland Park but with a gloriously assured fruitiness and a charcoal tang from the treatment the American oak casks would have had across the Atlantic – all are charred internally to add character to the whiskey made there.

Colour: Sandy, light gold

Nose: Salt and sweetness, a walk along a storm-tossed beach on a cloudy day. Firm leathery notes with a hint of seaweed.

Palate: This is a really assured whisky, with the merest hint of heathery island influence. There is a salt shoreline aspect, but you could be forgiven for thinking this was a Speyside malt. The American oak makes it creamy and smooth.

Finish: Burn-free and long lasting, vanilla pods and gorse bushes in the snow. Very nice indeed.

Lindisfarne Original Mead

Lindisfarne, or Holy Island, is reached by tidal causeway from the Northumberland coast in the north of England. The island is steeped in the Celtic, Roman and Viking traditions, and it’s 238 thought it was first settled by monks who arrived with St Aidan, via Iona. The monks brought their expertise in both beekeeping and the uses of honey to make mead, and this mead was seen by the locals, understandably, as holy – an elixir that could be used to heal the sick, promote long life and provide a little bit of comfort from the ferocious North Sea weather.

Lindisfarne Mead as sold today from the winery on the island comes in three varieties – original, dark, pink and spiced – and includes more than just fermented honey. It uses what’s thought to be a Roman, rather than Viking or Celtic recipe. So in addition to honey, ingredients include water, wine and raw alcohol, as well as various herbs and spices. The taste is described by the makers as ‘light, smooth, with a sharp aftertaste – reminiscent of a sweet-wine.’ The label is based on the artwork of the Lindisfarne Gospels, which were created at Lindisfarne Priory on the island in the 7th century.

Put it this way: it’s better than Buckfast Tonic.

Colour: Yellow-oaky gold

Nose: A smell of honeysuckle in the sunshine.

Palate: Slightly tart with honey coming in.

Finish: Cinnamon and ginger with a substantial, sweet punch.

Holy Waters: Searching for the sacred in a glass by Tom Morton is published by Watkins Publishing, priced £12.99.

Local Hero: Making a Scottish Classic celebrates the 40th anniversary of Bill Forsyth’s much-loved film, offering a scene-by-scene breakdown with commentary from cast and crew. Here, author Jonathan Melville selects five of his favourite scenes, including some newly-unearthed secrets from the production.

Local Hero: Making a Scottish Classic

By Jonathan Melville

Published by Polaris Publishing

Mac says “No” to Gordon

Sometimes it takes multiple viewings of a film to spot things you’d previously missed. Watching the scene that takes place in the hotel dining room soon after Mac (Peter Riegert) realises Ben (Fulton Mackay) owns the beach and tries to negotiate with him, Mac asks Gordon (Denis Lawson) to turn down the music. ‘Don’t you like this?’ asks Gordon, to which Mac replies ‘No’, going on to say the word a few more times. Discussing the scene with Denis Lawson, he confirmed that it was improvised to reflect the earlier scene of Mac asking Gideon (Peter Mowat) to add a dollar sign to his boat, the old man repeatedly saying ‘No’ to him. By the time we’ve reached the dining room scene Mac is now the old man and as much a part of the town as Gideon.

Whose Baby?

Bill Forsyth may have spent months of his life trying to perfect the Local Hero script, but one of the most memorable scenes was improvised on the day by star Peter Riegert. Originally Mac was meant to finish a conversation with Happer (Burt Lancaster) in the phone box and exit it, only for Roddy the barman (Tam Dean Burn) to tell him it was about to get another coat of paint. On the day Riegert spotted that a baby was in the pram beside the other actors and suggested to Forsyth that he ask the other characters ‘Whose baby?’ The look of confusion on the actors’ faces is because none of them had any lines, making the moment work perfectly.

Danny meets Gideon (or The Scene you Haven’t Seen)

This one’s a bit of a cheat as it’s a scene that’s not actually in Local Hero, but it was in Bill Forsyth’s script and it was filmed, so it sort-of counts. If you’ve watched the film then you’ll know that it’s hinted that Marina (Jenny Seagrove) might be a mermaid, though the actress herself won’t confirm or deny this. During my research I discovered that a scene had been shot between Danny and Gideon in which the latter tells a tale of mermaids being either homemakers or homebreakers, a story based on something that happened to Bill Forsyth years before on a Highland beach. For me it gives even more credence to the theory that Marina is indeed more than meets the eye, but it’s likely Forsyth removed it to ensure the film felt more grounded.

The Ceilidh

Technically this is more than just a scene, but I couldn’t resist dwelling on the full ceilidh sequence that lasts 16 minutes in the film. As well as being one of the few times that virtually the entire cast is gathered together at the same time (the church interior being the other), it’s one that’s packed with lovely little moments that allow both the film’s stars and those with smaller roles to shine. As Gordon tries to nudge Mac into agreeing a price for the village, Mac is slowly getting drunk, leading to the moments when he offers to swap places with Gordon and be “a good Gordon, Gordon.” In between this there’s Andrew (Ray Jeffries) doing his Jimmy Stewart impression, Victor (Christopher Rozycki) singing his song on stage, Peter (Charlie Kearney) wondering “what the poor people are doing tonight” and Pauline (Caroline Guthrie) chasing Danny around the room. There’s also Mac dancing with Stella (Jennifer Black) and Ben stealing pork pies. Perfection.

The final scene

Like much of Local Hero, the final moments of the film aren’t exactly what Bill Forsyth had in mind when he finished the script and began the shoot. Originally, after leaving Scotland, Mac returns to his Houston apartment, takes out his shells and photos, and phones his mechanic to discuss his Porsche, before standing outside on the balcony and watching the city. After studio executives watched the film they decided the ending was too depressing and pushed Forsyth to shoot something happier, perhaps with Mac jumping out of the helicopter and staying in Ferness with his new friends. Unwilling to compromise too much but aware he had to do something, Forsyth decided to use a short piece of footage he’d already shot, placing it at the end of the film and adding the sound of a ringing phone. Is it Mac phoning Ferness? Is it a wrong number? No matter your view, the executives were happy and Forsyth was able to release his film in 1983. The rest is cinema history.

Local Hero: Making a Scottish Classic by Jonathan Melville is published by Polaris Publishing, priced £16.99.

Throughout the history of golf, there are numerous myths and misconceptions – Neil Millar challenges these by revisiting the evidence supporting the sport’s earliest history, showcasing how the game blossomed in Scotland and its spread across subsequent centuries. We talk to Neil to learn a bit more about the history of golf, and the truth behind some of these most enduring myths.

Early Golf: Royal Myths and Ancient Histories

By Neil S Millar

Published by Edinburgh University Press

Can you tell us more about what we can expect from Early Golf?

Early Golf (which is subtitled ‘Royal Myths and Ancient Histories’) is a book that aims to dispel some of the widespread and popular myths associated with the early history of the game. The book’s primary focus is the period from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries, when golf flourished in Scotland and was subsequently exported from Scotland to other parts of the world.

What drew you to this topic? Have you always had an interest in golf?

By profession, I’m a scientist (a Professor of Molecular Pharmacology) but I’ve had a long-standing interest in the history of golf and I’ve read numerous accounts of the game’s early history. I became increasingly frustrated by the frequent repetition by many golf writers of anecdotes that were rarely, if ever, accompanied by the citation of supporting documentary evidence. This book re-examines and reassess the evidence, with the aim of providing a reliable account of early golf history.

You say yourself that fact-checking the early history of a sport can be laborious but can also reveal fascinating new information – what do you enjoy about the process of diving deep into these histories? How do you approach a topic so vast?

Trawling through early written documents in libraries and archives can certainly be time consuming. However, finding long-forgotten historical evidence is exhilarating and is also very rewarding. Recent advances in the digitisation of historical records and the better cataloguing of historical archives have meant that undertaking the research for this book was considerably less daunting than it might otherwise have been. The starting point for topics discussed in the book was, typically, prompted by unsubstantiated claims that had been made by previous writers and then repeated in numerous subsequent publications.

The book challenges myths and misconceptions about golf, including Mary Queen of Scots’ supposed love of the sport – what are some notions people have had about golf and its history that aren’t quite true? How did they come to be believed?

With Mary Queen of Scots, it’s more of a case of writers making unsubstantiated and increasingly exaggerated claims. It’s true that there is a single contemporary historical document claiming that Mary acted inappropriately by playing golf shortly after the murder of her husband. However, this is a document that was drawn up by Mary’s enemies, with the aim of discrediting her prior to her trial and execution in England. It’s a document that is now seen as providing an unreliable account of Mary’s activities. But, despite this, there have been claims that Mary played golf in some twenty different locations in Scotland. The claims concerning Mary’s enthusiasm for golf have become increasingly exaggerated and, at times, almost absurd. It has even been claimed that she designed the Old Course in St Andrews. This is a good example of the romanticisation of golf history.

Your research is underpinned by historical documents, many of which are included throughout; are there any documents or historical artefacts that you found particularly interesting or pertinent to the topic that stand out, or that you enjoyed learning more about?

Of particular significance is a letter that was written in 1513 by Catherine of Aragon, the first wife of King Henry VIII. This letter, which still survives in the British Library, has long been seen as providing evidence that golf was played in England (as opposed to Scotland) about a hundred years earlier than might otherwise have been thought. It is a claim that has been repeated endlessly but it is a story that arose as a consequence of a transcriptional error that was made in the nineteenth century when attempting to decipher the letter’s sixteenth-century handwriting. The letter was assumed to contain a reference to Catherine of Aragon being ‘busy with the golf’ but, on re-examination, it’s clear that she wrote ‘busy with the Scots’ (Catherine was writing about preparations for a forthcoming battle between England and Scotland). Whereas there are written references to ‘golf’ in Scotland in the 1400s, there is no evidence of golf being played in England before the union of the Scottish and English crowns in the early 1600s.

The book, naturally, focuses on the early days of golf and its origins – how do you think the sport has evolved over the centuries? What roots of the game can you see in these earliest records?

Although the first part of Early Golf takes a chronological approach and focusses primarily on the re-examination of myths that are associated with early golf history, the second part of the book is more thematic and addresses issues relevant to how the game has evolved. This includes a discussion of the origins of golf societies (and their claimed foundation dates), the development of women’s golf and the evolution of golf balls and clubs. The final couple of chapters address two particularly contentious topics: whether golf has its origins in Scotland and the extent to which early golf in Scotland may have been influenced by early stick-and-ball game played in other countries.

What do you hope readers take from Early Golf?

I hope that readers of Early Golf will discover that golf is a game with a long and a fascinating history, but that much of what has been written about early golf in popular histories is incorrect.

Early Golf: Royal Myths and Ancient Histories by Neil S Millar is published by Edinburgh University Press, priced £24.99.

New Writing Scotland collects the best new poetry and short fiction in Scotland today, from both emerging and established writers. This latest edition – nobody remembers the birdman – is no different, bringing together over forty pieces of new writing to dive into. You can read Ellen Forkin’s story ‘Hare, Bee, Witch’ below.

‘Hare, Bee, Witch’

By Ellen Forkin

Taken from nobody remembers the birdman: New Writing Scotland 40

Edited by Rachelle Atalla, Marjorie Lotfi & Maggie Rabatski

Published by Association for Scottish Literature

I never profited the neighbours’ milk, my familiars sneaking in the moonlight, with cream on their snouts. I have no poppets, dirty wax, torn linen and stolen hair, moulded with swift fingers to the likeness of my enemies. There are no spare pins to prick agony into them. I did not curse the village cat, plump and thick-furred, until it vomited up blood and lay on its side, all a-twitching. It was unwelcome upon my table, but I meant it no harm. I have lived many a year; I fear the rumours about me will live longer. But it is not true. I, Isobel, am good.

It has started to rain, a fine drizzle made ice by the wind. My body is tied to a stake with peat, and what little wood they can spare, all stacked up about my bare feet and legs. It will burn slow. I am in a shift, grubby and torn, my exposed body shivering violently. A crowd stares; surely the whole of Orkney has come to Gallow Ha’ to watch. They take in my matted hair, unwashed skin, blooms of bruises, red, festering cuts and sores. My nose is broken, crooked. I am one of four women, all equally ragged and bleeding and staring into nothingness. We have known horrors. The executioner stands by, legs apart, breathing deeply. He, with a twist of rope in his meaty hands, promises of more horrors to come.

‘Witch!’

‘Hag!’

‘Crone!’ All shouted into the wind. Am I a witch as they say I am? I certainly didn’t curse Old Rob who ate and drank too a-plenty, until the great redness of his nose and cheeks finally poisoned him. Now he is confined to his bed with only weak ale to wet his trembling lips. I am not homeless, dirty, and simple like Margaret who begged constantly for alms and bread and sometimes the sweet oblivion of honey. She slept in byres and barns, unseemly on folks’ doorsteps. And neither am I like Ingrid, with her one, wandering eye, who has lived through many a bad crop. She was foolish enough to comment her wisdom on dying grain before the young folk even thought of the word ‘famine’.

Oh yes, people are hungry.

I feel their eyes eating us up.

My throat feels prickly, exposed to the icy rain. Soon the rope will curl around my neck. A kindness, some say. A kindness before the flames. It is but little comfort. The meaty hands fidget, making the rope twitch.

After the strangling, our bodies will be burnt to nothing. We will not crawl out of our graves, groaning and undead, to torment the isles with our evil. On Judgement Day, we will not rise with every other soul, facing east into the holy light. That’s what burning is: a precaution for the living; a punishment for the dead.

We will be unmarked ash, filth in the breeze, and nothing more.

I hear Margaret keening.

I try to twist to catch Agnes’s eye. Agnes who is pious and good and churchly. Agnes who I, in my agony under ‘the boots’, named as a fellow witch because she was so devout. Who could ever suspect her of devilry? But then, it was Agnes who dared to scold the bishop for misquoting the Bible. Agnes who shamed her husband for not compensating young Jamie, his future uncertain with a mangled hand. Agnes who stood tall in church, singing loudly, unflinchingly. Untouchable.

The husband stands apart but does not look sorry. The bishop, I’m sure, is word-perfect now. The sermon and its prayers flow over us and few pay attention. Certainly not I.

My neighbours say I cannot recite the Lord’s Prayer without mistakes peppering my speech. It’s a tricky thing to learn for a simple woman such as myself. They say, in breathless whispers, that I slip out into the darkness as a midnight hare. To gaze at the moon and read the stars. They say I eavesdrop at their doorways as a bumblebee, then fly away home heavy with their secrets. It is common knowledge I killed the plump and thick-furred cat because she was a rival witch.

Shapeshifting. But not quite. I swallow, my throat raw, and think of my mother. Her murmured words. Her tricks. I gaze at the crowd, waiting, waiting. Anne, kind but slow, meets my eye. I strike.

Our souls – they swap. I snap into her plump and doughy body, taking my thoughts and feelings and knowledge and memories with me. Her blood feels warm and sluggish. Her fingers thick and shorter than I am used to. And my body, the one I have just abandoned, starts screaming.

‘You’ve got the wrong woman! I’m not Isobel! I’m not Isobel! It is not I.’ The crowd titters, delighted. Anne, trapped in my old body, sobs. Hysterical, ugly tears. The executioner wraps the rope around his hands. He is ready.

I step away. My new body has small, spongey feet. I cannot be Anne for long. I do not want her husband. Her children. Her skills of midwifery. Anne will be found lifeless, crumpled in a ditch, before the sun has set. The shock of the burnings, many will say. No one will notice the froth of hemlock upon her tongue.

And I will crouch in the heather, heart skittering, a midnight hare. My long ears twitching in the wind, as a flea bites my shank. I will hide and know that I, Isobel, am good no longer.

Ellen Forkin is a chronically ill writer living in windswept Orkney. She has a love for all things folklore, myth and magic. Find her published and upcoming work in The Haar, Paragraph Planet, Crow & Cross Keys and in Ghostlore on the Alternative Stories podcast.

nobody remembers the birdman: New Writing Scotland 40 edited by Rachelle Atalla, Marjorie Lotfi and Maggie Rabatski is published by the Association for Scottish Literature, priced £9.95.

Paul Strachan has written a history of the rivers of Burma and the paddle steamers run by Scottish companies in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Below is an extract and some photos from this book which is illustrated throughout.

The Fabulous Flotilla: Scotland’s Adventure on the Rivers of Burma

By Paul Strachan

Published by Whittles Publishing

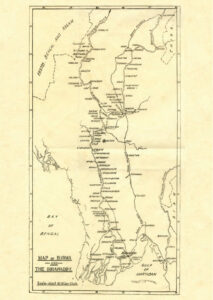

Standing anywhere along the bank of the Irrawaddy, or Ayeyarwady, river, you will see an average of at least 500,000 cubic feet of water flowing past you every second. In the monsoon it it would be just over 2,000,000 cubic feet per second. Such a flow represents one of the greatest challenges to navigation, and as the channels and sands shift daily the river cannot be charted. It is buoyed – haphazardly – only in the low water season. Officially the river begins at a confluence of streams from the Himalayas near Myitkyina in Kachin state, from where it flows 1,370 miles into the Indian Ocean. It is navigable by larger vessels for just over 1,000 miles. Its main tributary is the Chindwin, which runs for 750 miles, of which 600 are navigable by lighter vessels.

These are not of course the only rivers in Burma. The Irrawaddy has several other tributaries, which extend into a vast area, and altogether the Irrawaddy basin covers over 150,000 square miles. Then there is the Salween which, at 1,749 miles, is the longest river in Burma, though navigable for only its lowest 50 miles or so, such is the strength of its flow. From the south-eastern port of Moulmein1 there is a whole network of rivers, mainly navigable for some distance, and in the western coastal region of the Arakan there is a river system of dazzling complexity, the main form of communication in a land with few roads. Finally, the several thousand square miles of the Irrawaddy Delta have an uncounted number of creeks and channels. To say that Burma is a land of rivers is an understatement.

In the distant past peoples migrated from deep inland down these river valleys; first came the Pyu, the proto-Burmans, ethnically Tibeto-Burmese, then the Mien, or Myan, the Burmans themselves. They lived in city-states that were like oases in jungles full of wild animals. Upriver came trade from India, bringing Indian religious cults, Hindu and Buddhist – the latter in a mix of what was later to be defined as Mahayana and Theravada, but until the ‘purification’ by the 11th-century kings of Pagan2 these two divisions would have been seen as one and the same.

All movement – of goods, cultures, religions, armies – in this country was by river, and this remained so till the late 20th century. Back in the 12th century the King of Ceylon mounted a naval raid and, having crossed the Indian Ocean, sailed upriver to seize valued elephants to take back home. In the 13th century the Mongols under Genghis Khan were to sail down the river and take Pagan. There followed several centuries of Mon–Burmese3 conflict in which armies were shipped up and down the Irrawaddy in great barges. Then the British arrived, and in three short, sharp river wars annexed the country in stages. Thereafter the British colonisation and economic development (or exploitation, depending on your viewpoint) all took place along the rivers, assisted by the development of the Irrawaddy Flotilla, which after 1864 became a Scottish concern.

Map of Burma and the Irwaddy River.

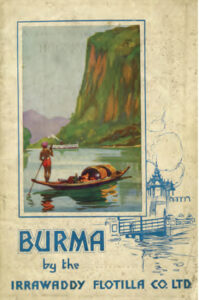

Handbook: a guide book for tourists produced by the IFC in 1935. Burma’s most famous artist, U Ba Nyan, was commissioned to illustrate the cover.

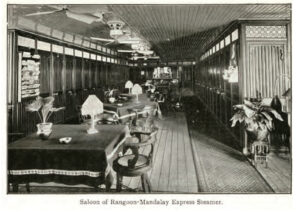

The saloon of a typical express steamer, with the tiny cabins off to the sides. The saloon would be ventilated by air blowing through from a forward opening when the ship was in motion. Note also the electric fans.

The Fabulous Flotilla: Scotland’s Adventure on the Rivers of Burma by Paul Strachan is published by Whittles Publishing, priced £18.99.

Born in 2089, Theo finds himself reliving lives that span prehistoric times to those modern – he’s been a King, a fisherman; a man, a woman; a hunter, famer; a soldier, a priest. He’s lived more lives than we can comprehend, each shining a light on his own disintegrating world. Read an extract from this mind-bending novel below.

Labyrinth

By Oliver Thomson

Published by Sparsile Books

Let’s play the music and dance

I. Berlin

New York, Jan 17th, 2118

I’m facing a crisis, probably of my own making. My career is extremely dull, but I need the money, so I put up with it. My love life is a contradiction in terms, disaster. Yesterday I zoomed Dr Jane, the shrink at my old college, and she instantly diagnosed early-onset metempsychosis.

‘What’s that?’ I asked. ‘It sounds nasty.’

‘Well, it’s still quite rare,’ she replied. ‘Nothing to worry about. It was recognised quite recently by a group of research psychiatrists based at the Bronx University. They identified a kind of non-functional DNA, buried under the more recent functional DNA, which means that some people have memories about their ancestors, usually as dreams. Often they are quite detailed, as if the people actually inherit a mental picture from long-dead relatives. The ancient Greeks understood it perfectly well, Pythagoras in particular.’

‘In other words I dream too much,’ I said. It’s mostly about my ancestors who were much brighter than me and make me feel inadequate. I feel boringly average with a third-class degree in social media, reduced from a second because I failed the hacking practical.

I asked Dr Jane what I should do about it all.

‘I have several patients who practice yoga and they are quite good at controlling these dreams. So are some Australian aborigines. But the Bronx research group are looking for more guinea pigs to back up their research using a new bio implant, so they’re offering money to anyone like you who will report your dream memories. Why not give it a go? You could download the memories yourself and play them back; it might be therapeutic as well as financially useful. And find a good woman while you’re at it. Was there not a suitable woman in one of your dreams?’

I thought there was. It might even have been Dr Jane herself, for she was very attractive in some ways. Then she added, ‘From bits you mentioned earlier I gather there are a few mysteries in your past. Why not get those dreams in the right order, so that you have a proper family history, maybe even going back to the Stone Age?’

Brooklyn, New York, Jan 2nd, 2119

I fear that I made no immediate effort to follow the doctor’s advice. After signing up for the program and receiving the implant, I set the recordings to download onto my comp, but never seemed to get the time to replay them. Apart from my work, the news had become my main obsession, but it has been more and more depressing.

New York is once more the worst city for overdose deaths per thousand people. All the international space stations have been abandoned due the huge halo of satellite debris scattered round the globe. And today is the 400th anniversary of the first ever financial crash in the USA, when the banks dished out too much paper money, then suddenly panicked and stopped, causing all-round disaster and misery. It still keeps happening. The one bit of good news is that this year the average summer temperature has dropped to 47 degrees, so perhaps global warming has stopped at last. Yet there has been a spate of violent hurricanes including Hurricane Harry VII which left half of Texas under water And of course famine and wars continue in dozens of places all round the globe. To cheer us up the massive new cruise liner, the thorium-powered QE4, came up the Hudson to a rousing welcome from the fire tugs.

But I realise that I haven’t introduced myself yet, so here goes.

My name is Theo A. Thens. I was born in the year 2089 on floor 203 of the north condominium, where the lifts frequently broke down and most people just went up or down a few floors except on special occasions. Of those in employment most worked on e-pods, so they didn’t need to move around much. There was a frozen food shop on floor 198 which catered for most of our needs and an open exercise area on the floor above where we could also plant vegetables in tubs.

Until I was fifteen I never went above floor 220, but when I did, it was to visit a poor cousin of my mother’s and I was shocked by the conditions up there. People had to go either up or down five floors to the shops and these offered a very limited choice. The ceilings in the rooms were even lower than in ours, and many of the apartments had no external window. For some this was a blessing, for the average summer temperature was then 48 degrees and the less sunlight the better. All coal and gas-burning heaters had been illegal for the last seventy years, but it had been too late to stop many of the effects of global warming. Several countries close to the equator had been reduced to empty desert and the children of redundant oil-workers had formed maniac gangs which roamed the country causing mischief. In our own building groups of youngsters wandered along the corridors spraying the walls with obscene pictures and unintelligible slogans from long-forgotten tribes.

Eventually my father, Mino, developed quite an expertise in real meat trading on his e-pod and we were able to move to a three-storey block with a real lawn off Brooklyn, while I attended the Multi-media College.

New York by this time had so many cable ducts and so few vehicles apart from roboids that most of the streets were left permanently dug up. Thus the cable repair people could spend all day fiddling with the tangle of disconnected drains, leaking water pipes, telecom tubes, redundant wires and satellite connectors until they found each fault, by which time they needed to start all over again.

When I was eighteen my father announced that there was little future in real meat, as cattle breeding had been discontinued in most countries due to methane emissions, so I chose to go into timber trading instead. Not that I see or feel any actual wood. I just shift various types of plank around the world using my e-pod. Very occasionally I go to a dealers’ conference, which means three changes of roboid to the other end of the state. I now control three out-workers, so I have to put myself about a bit.

To sum up I do now feel slightly important. I get a little bit of respect, but I haven’t fought in a war or invented anything. I’m still underachieving, so if my soul has transmigrated from someone else’s dead body, like Orpheus said, then it’s unlikely that I’m much of an improvement on the last owner. Unless of course its owner was a cockroach. As Dr Jane suggested, I think I will replay my dreams, at least the exciting ones. There was a shrink in Switzerland called Jung who said that you can remember things in dreams which you could never remember when you are awake. But I can, if I replay my recordings.

I am a good hunter, one of the best in the tribe. We have always brought in enough meat and hides for the women and children. But the animals seem to be moving away. We have to run a long distance to find any. And the berries hardly ever seem to ripen. My legs are beginning to hurt. I need more to eat. I’m tired. There is a constant trickle of ice-cold water coming from the cave above my head and I cannot be bothered moving.

Labyrinth by Oliver Thomson is published by Sparsile Books.

The Wee Kirkcudbright Centipede is an amazing dancer but when her neighbour asks her to explain how she does it, they end up in quite the fankle. Based on the song by Matt McGinn, the story is now captured in this bright, fun picture book. You can see a sample of the story below.

The Wee Kirkcudbright Centipede

By Matt McGinn, illustrated by Fran Raw

Published by Foggie Toddle Books

The Wee Kirkcudbright Centipede by Matt McGinn, illustrated by Fran Raw is published by Foggie Toddle Books, priced £6.99.

In her debut collection, Leyla Josephine dances between her private and public lives, with her poetry navigating secrets, faith, shame, lust, death and more. You can read an exclusive extract of a few poems from the collection below.

In Public/In Private

By Leyla Josephine

Published by Burning Eye Books

In Public / In Private

Definition of in public:

in a place where one can be seen (by many people or one other person): there is no specification of how they are seen, if they are aware they are being seen or if there is any value/ truth in what is observed.

Sentence examples: The former actress is now rarely seen in public. They were seen kissing in public. The drunk pissed in public, a breeze on her pebbledash bum.

Definition of in private:

Not in public: secret, confidential, without others seeing. Sentence examples: The hearings will be conducted in private. May I speak to you in private? The poet cried in private and she didn’t like that no one knew; it made her question whether the crying

happened at all.

Sub Club

The sky has caved in

and we can finally touch it.

We are abyss

dancing. Sucked into

the vacuum, side by side.

Geckos with wide eyes.

Even the light has a pulse tonight.

Stars spiral down the drains.

The bathroom has flooded

again. One-eyed gods

thud above us,

and we sacrifice

our limbs willingly.

Charging ourselves

to oblivion, swallowing

batteries. We are so high

if we died like this

it would feel right.

Taxis wait above

our submarine

on the soaked street

ready to take us

to worried parents,

but we’re not finished yet.

The floor thumps

into our legs,

travels up our spines

until it feels like the music

is coming out

from our insides.

We are bleached

by strobe light.

The girls

i’ve got the girls / forever / they’ve been with me / staggering down streets / laughing / dancing / on tables / girls / with our tales that we keep / for takeaway meals / girls / hold your hand / make you tea / come to bed with me girl / seas separate

us sometimes / but somehow we come home / to melt / into each other / always / the girls / mac counter warriors / belts of lipstick weapons / contouring is witchcraft / fuck him / fuck that / taking our bodies back / bring the girls out of the dark / into highlighter herstory / the girls / just try to call us / hysterical girls / fire in our cheeks girls / keys between our knuckles girls / the betrayed again girls / when we are alone / you underestimate us / but together we take up the pavement / cemented / and you feel threatened / my girls / our love stories are the greatest never told / we are the bold girls / the too much girls / we laugh as loud as our mothers / feel the moon in our waters / we don’t chew when we eat / forget to breathe when we speak / we are the don’t interrupt us girls / the angry girls / the silenced girls / the dangerous girls / the we’re coming for you / girls /

In Public/In Private by Leyla Josephine is published by Burning Eye Books, priced £9.99.

As part of the Year of Scotland’s Stories, we are running a series of Responses on BooksfromScotland, commissioning writers to respond to books from the publishing membership, engaging with work in different ways. For November, and to close the series, Edwin Morgan Poetry Award-winner Titilayo Farukuoye considers The Golden Treasury of Scottish Verse, on the past, present and future of Scottish poetry.

The Golden Treasury of Scottish Verse

By Edited by Kathleen Jamie, Don Paterson & Peter Mackay

Published by Canongate Books

Confession: l have only been claiming the title poet for a season now. I maybe toyed with it, and definitely aspired to it before, but there is something about claiming an official label to one’s name that sometimes requires the force of Edwin Morgan, and a nod from an entire selection committee of well admired writers, to claw back layers upon layers of rejection, imposter syndrome, self-doubt and ‘don’t take yourself so seriously-s’, that encourage us to step into our truths.

And frankly, as a Black (dyslexic) poet of a different birth tongue, excelling in the literary world, in a foreign language, was not, shall we say, anticipated of me.

To think, that I would even put the word poet into my mouth just as I am getting ready to mention so many of our national icons featured in the collection – The Golden Treasury of Scottish Verse: Robert Burns, Peter Mackay, Liz Lochhead, Jackie Kay, Alastair Mackie, Veronica Forrest-Thomson, Vahni Capildeo, Edwin Morgan,… and many more, is truly something.

Looking at The Golden Treasury of Scottish Verse, I had to practice a little bit of self-care, and personal bolstering to remind myself to claim space in this literary landscape of Scottish poetics. (If not for my own sake, then for all of the writers marginalised and rendered invisible in a sector in which queer, BPOC, disabled, working class poets and poets with asylum and migration experience continue to face barriers in. I allowed myself to ask, What is Scottish poetry actually? What is the legacy we inherit as Scottish poets today? And who can claim the craft for themselves?

Editors Kathleen Jamie, Don Peterson and Peter Mackay invite answers to this in the collection. As I -open the book anywhere – appreciative of their instruction, I cannot help myself but romanticise far away times, imagine wild stormy landscapes, green plains, a tempestuous sea,..

This initial image is a visitors’ illusion, a pretty smile Scotland holds up to the sky – a face that, tourists, from across the sea (Atlantic and otherwise) and folk we bump into on the Royal Mile, or, on the off chance of us nipping out early onto Princes Street, see, in this home of ours. It’s a part, at least, of the whole story.

Quickly, the collection transforms and shapes into something that poetry inevitably does. It becomes societal commentary, a history lesson, a reflection and negotiation of the poet’s realities…

In six o’clock news, Tom Leonard writes, ‘yooz doant no thi trooth’, and continues, ‘yirsellz cawz’ ‘yi canny talk right.’ ‘This is the six a clock nyooz. belt up’. Leonard’s poem is gorgeously attributed to the powerplay embodied by dominant language and the culture of the disenfranchisement Scotland experiences from mainstream cultural institutions in the UK. What does it mean for a people if the news is not reported in their tongue? What are the repercussions of intellectualising one regional language over another?

I quickly find my own linguistic limits in the collection, and soon also start thinking about gate keeping, and the power that lies with commanding Scots and Gaelic among other languages. They serve as markers of belonging and justify a ‘claim’ to Scotland and Scottishness. Stretching for my own voice to read out loud and discover meanings my eyes alone don’t grasp, as well as dictionaries and translations online, google searches, and friends, all come to my aid: I become painfully aware of my lack of (Scottishness) exposure to Scots and Gaelic.

I enjoy this challenge though (especially since I have never seriously claimed Scottish identity for myself) and can’t help but wonder if this could be an invitation to all of us to explore our own relationships with Scotland’s languages, and to indulge in them a little bit more. Excitingly, Du Fu (712–770) a prominent Chinese poet of the Tang Dynasty is represented in the collection. I can’t wait to see poems in Urdu, Punjabi, Farsi, Twi, Yoruba, Arabic, Amharic, Polish, Cantonese and more in future collections commemorating Scottish Verse.

There is a lot that is striking in the collection, Ian Crichton Smith’s Clearances almost next to Marion Bernstein’s The Highland Laird’s Song are a good shock to a reader’s system. Bernstein’s lines all for me all for me echo in my head long after the fact of reading the poem, The dirty creatures now complain; Blaming me, Blaming me; leave one shivering, contrasting the pain, devastation and fury the poem Clearances offered insight to.

To me this speaks to the reckoning we still need to do as a nation. How do we negotiate our violent past? Is there a way to make good past evils? How can we move beyond narratives of victimhood and pity and actually learn from the past to change the systems and elevate communities, elevate peoples who have been mistreated and violated for generations?

Scotland’s legacy of colonialism and Empire also finds traces in the book, Jackie Kay’s In my Country answers the question Where are you from? with ‘Here’ I said. ‘Here. These parts’.

Scottish Ghanian visual artist, educator, and poet Maud Sulter’s (1960-2008) work is a crucial voice in Scotland that should be commemorated to acknowledge this history. Among some of her most influential works must be Blackwomen’s Creativity Project, through which Sulter sought to document artistic practices of Black women creatives in the 1980s, which led to the publication Passion: Discourses on Blackwomen’s Creativity.

Sulter writes in Passion (2002) ‘See me, I’m a heroic poet and I don’t care who knows it. And I chose my own kind and in doing so apparently consigned myself to a footnote in history.’

Even today, the beckoning to see violence and injustice addressed, still remains with those who endured and survived it. A way of sharing this responsibility can be to actively seek out and elevate the poets who are doing this work. Future Scottish Verse should ensure that we bring trailblazers like Sulter to the forefront. We urgently need to acknowledge the countless poets who are continuing her inspiring work.

A project this year led by independent arts collective Rhubaba brought together Black Scottish women and non-binary people creatives today, to commemorate Sulter’s work. Alongside documentary film maud., the zine PASSIONS (2022) was dedicated to Maud Sulter and serves to archive and spotlight Black women and non-binary creatives in the Scotland.

Jeda Pearl is an incredible voice in poetry and science fiction writing in Scotland today, in her poem Inheritance Reverb published in PASSIONS (2022), the Scottish-Jamaican poet writes, ‘yuh still lost in yuh maze of post-colonial consumption’ directly addressing Scotland’s colonial legacy. The poem continues ‘mi double-dar yuh give our lush little islands a mention’.

Renowned creative non-fiction writer Amanda Thomson describes that public awareness and willingness to engage in the issue is only temporary, in TWA Black WIMMIN, Revisited. (PASSIONS, 2022) she writes, ‘I can’t help but think that there’s a cyclical nature to the world and our position in it, we ebb and flow; we come into view and recede again (though we are always visible to those like us and those who choose to see us, or who seek us out).’

It is impossible not to mention Edinburgh Makar Hannah Lavery’s debut collection Blood Salt Spring. In her poem The anti-racist working group, Lavery writes, ‘Wonder if they are starting to realise, that they don’t want to give anything away.’ ‘Hush Now (Shitty Brown) and Thirty laughing emojis, brilliantly testify to the reality of race on an everyday basis.’

Award-winning poet Roshni Gallagher is an important new voice in the scene. She describes her poem The Whitby as ‘a sonnet about reckoning with the colonial ties of a place that I love (…) The poem follows the journey first boats that transported indentured labourers from India to Guyana in the 1800s.’

To me poetry is a way to digest and articulate stories and struggles that affect communities. The Golden Treasury of Scottish Verse is a brilliant collection, that through its vastness touches on and verbalises so much of Scottish culture, history, and aspiration.

As a new poet, and as Black poet, I see my work as an opportunity to reconcile, give voice and contemplate issues that pertain our lives today, so that we might better communicate them, and might even come up with solutions, or how wonderful poet Andrés N. Ordorica would put it, to contemplate ‘what it means to be from ni de aquí, ni de allá (neither here, nor there)’.

For the occasion, I would like to offer you my most recent Scottish poem.

Glasgow, King Street.

By Titilayo Farukuoye

Their hair: clouds, flowers

in the sky.

dancing in knots

in braids, in weaves

in twists

Reflections of the sun

(brown, black, green, red, blond, purple)

Their bodies: slick, taking space

wide, laughing, chatting

round, stiff and flexible.

Fingers licking:

Caramelised plantain

(Dodo!)

Dripping chicken

Jollof!

Happy cheers and bouncin:

bumps

arms smiles

breasts all of it.

hair

All pigments, colouring fabrics

compelling

contrasting dancing with

each other.

Raging for attention.

‘Should I help you adjust your headscarf?’

The Golden Treasury of Scottish Verse, edited by Kathleen Jamie, Don Paterson & Peter Mackay is published by Canongate Books, priced £30.

The Year of Stories x Books from Scotland response strand was inspired by Fringe of Colour’s series, which you can read more of at fringeofcolour.co.uk.

JD Kirk has become a bestselling sensation with his self-published crime novels. Better known as Barry Hutchison, BooksfromScotland caught up with him to talk about his latest novel and about his career as an author.

Eastgate

By JD Kirk

Published by Xertex Media

Eastgate is the fourth in a new crime series centred around a character called Bob Hoon. After such a varied writing career including multiple children’s books, what brought you to crime, and how has the experience of writing Bob Hoon differed from your hugely successful DCI Jack Logan series?

So the Bob Hoon books are a spinoff from the Logan series. There’s a character in the Logan series, Robert Hoon, who was Detective Superintendent. He was basically created to be like a Scottish psychotic version of the boss in Cagney and Lacey who was always giving them grief. He was supposed to be quite a two-dimensional character who just popped up in a few scenes to cause trouble, but then I started getting lots of emails about him. They were quite mixed, it was half going, ‘I absolutely hate this character and skip over all his scenes’, and the other half going, ‘I love him, he’s the greatest character I’ve ever read’. So I was quite tempted to see if I could redeem him a bit in the eyes of the people who hate him, if I could still stay true to his character but turn him into a three-dimensional character that people identified with.

It was originally going to be a trilogy. The first one is called Northwind, the second Southpaw, and the third Westward, and it was my son who said I had to do four. I had no idea what East was going to be, but then up in Inverness there’s the Eastgate Shopping Centre, and I thought that could work. At least it fits in with the naming pattern! Eastgate is basically an action movie in book form. It’s a terrorist takeover of the shopping centre which Bob Hoon finds himself at the centre of. It’s like a sweary, psychotic, Scottish Die Hard. It was almost like a Christmas Special this one, because the cast of the Logan series are in it, it rounds off the Hoon series, it’s kind of a big explosive action-packed ending with all the characters the readers have come to love over the course of the series, with a bit of social commentary on male entitlement in there too through the villains.

This conscious framing of the book as a Die Hard set in the Highlands is complemented by Bob Hoon, who’s written very much in the hard-boiled mode with a number of genre winks and familiar characterisations. Do you enjoy working within the tropes of different genres?

Yeah, very much so. The Hoon books were always meant to be fun, I mean they go dark at points, but it’s always been me having an absolute blast writing them. I suppose it’s been like a tour of all my writing inspirations as well, so it goes through books I’ve read, films I’ve seen, and there’s little winks and nods to those, down all the way to things like how my daughter’s really into anime and there’s little nods to that in there. So yeah, it’s been a celebration of all the fiction I’ve loved really. With it being the last one in the series as well I’d say it’s probably not as dark as some of the earlier ones, despite it being an Incel terrorist takeover! It’s more a celebration of Bob Hoon.

So you were born in Fort William and are settled there now with your family. All the Jack Logan books are set in the Highlands and of course Eastgate is set in the Inverness shopping centre of the same name. How important is setting to your work and to the crime form in general?

Well I’d say it’s very important for a couple of reasons. Firstly, I’m a very lazy person and I know the Highlands quite well, so in terms of having to do very little research, it was really important! But what I’ve found is, it does really well in the Highlands, my series, because people really like reading about where they live, but internationally it also does really well too. Certainly during lockdown, people would feel like they were able to travel to the Highlands, so internationally that’s a big pull of the books, the romance of it all.

What’s also interesting is I have something called aphantasia, which means I have no mental pictures, I think in words. But the number of people who say, ‘Oh, wow, it was just like being there’, and I always found that fascinating just how that works, because when I read a book, quite often when there are paragraphs and paragraphs describing a scene, I’ll almost gloss over that because it’s doing me no favours. It’s like, I get it, you’re in a room! I want the dialogue and the action and the story. But a lot of people like that lingering in a place and establishing the scene, so it fascinates me how different readers respond to different ways of writing.

So for those who may not know, you self-publish your crime fiction through Zertex Media, and to massive success. What was it that took you down that path of publishing, and what kind of benefits do you think it grants you as the author?

Well I worked with publishers for about ten years writing kids’ books, but ultimately it was by accident that I got into self-publishing. Like most kids’ authors, most of my income came from doing school events, and I got asked to go to a school in Elgin and talk about how kids can publish their own books. But I had no idea how kids could publish their own books! As far as I was concerned, you wrote something and sent it to London, and 6 months to a year later a book arrived in the post. But they were offering to pay me to do four different sessions, so I thought okay, I’ll learn. I quickly rattled off this comedy/science fiction book called Space Team and I stuck that on Kindle. Then we went away on holiday, and Space Team started outselling all my kids’ books, but I’d done no marketing for it. I didn’t think anyone was going to buy it. I designed the cover myself, it was all self-edited, it was an experiment to learn.

By the time we were back from holiday, it was making something like £50 or £60 per day, and I thought I’m going to try and write a second one. When I wrote a second one then the sales of the first book skyrocketed, and by the time I wrote the third one I was earning more in one day on these three books than I was in six months on all my traditionally published books combined. I ended up writing twelve books in that series, we did three spin-off book series and the audiobooks, but it all felt a bit ad-hoc. It was still just me uploading to Kindle. So when I had the idea for the crime series, I wanted to do it properly. We set up a limited company, contacted foreign rights sales agents, TV rights agents, we’ve now got a PR company involved. We wanted to get into bookshops, so we got tied up with Booksource and then CPI to do print runs, and we’ve got Martin Palmer Publishing Services who are kind of acting as sales agents.

In terms of the advantages, what I was getting a bit sick of with traditional publishing, was that I’d pitch an idea and say, ‘Right I want to do this book’, and they’d say, ‘Great, now can you put a unicorn in it? Unicorns are massive at the moment!’ So you’re always compromising. Which is part of the whole industry, of course, but then when I was doing the Space Team books, I was just writing it for myself. Then when people were asking about merchandise, I had all the rights, so I did T-shirts, mugs, and we were able to exploit audio fully, because a lot of my books the audio rights were with the publishers but they never did anything with them. Hanging on to all the rights was massive, but creatively it was just really freeing.

On the flip side, suddenly all the responsibility was mine as well. Luckily we were in a position where it wasn’t just me doing everything, we had cover designers, editors, working with us freelance. We’ve actually just started doing some Logan and Hoon series merchandise, exclusive merchandise whose proceeds are going to local charities based here in the Highlands. There’s a different charity every 3 months – the first one was set up by an old school friend whose son died of cancer when he was a year old, so they’ve set up a charity for raising awareness for children with cancer. Again this was led by people just asking for merchandise, so I thought since I’ve been so well supported in the area, we could use this as a way of giving a bit back into the local area.

So what do you think it was about your books that made them such a huge success? You mention how you didn’t do any marketing for the Space Team titles, and I’m sure there are a lot of writers considering self-publishing but who are unsure of how to go about it. Do you have a magic tip?

I genuinely wish I knew. I think a big part of it is just being nice to people. When I was learning about self-publishing I joined a couple of Facebook groups, and I got involved in those. And when my first Space Team book came out, a couple of people in that group who I’d not necessarily helped but who had seen me help others out, shared it, said check this new book out, and it just built from there. With Amazon especially, I think if you can get that momentum early, if you get a flurry of readers who review it positively, then Amazon will start to show it around. That’s why I changed my name for the crime fiction series. Well two reasons: firstly I didn’t want the kids who’d read my other books to suddenly read books about death and murder and lots and lots of swearing, but also, if I put out books under my sci-fi name then I know lots of sci-fi readers would’ve picked up those books because Amazon would have registered the name and displayed it as of interest to science fiction readers. So I kept the name a secret until it had established itself as a crime series in its own right, and Amazon knew that JD Kirk writes crime and to show those books to crime readers. But these are all things that I’d learned by trial and error over the course of the Space Team books.

So involving yourself in the community and learning the system…

Yeah, and I think the word ‘community’ there is really important. Around both the Space Team books and JD Kirk books, I don’t do much marketing, but I look at building a community. For example, with the JD Kirk group, a lot of the readers are older and are on Facebook and some were alone at Christmas, so we did a kind of Christmas get-together. I put on some quizzes, I’d recorded videos with a wee Santa hat, and loads of them got together on the Facebook group to chat and spend Christmas together. I just love that kind of thing happening regardless of any knock-on effect, but people then become more than readers of the book, they become invested in the community as well, so that when a new book comes out they’re straight on it and chatting about it. So for me it’s always been about communities of readers.

We had a readers’ newsletter a couple of years ago, which we’ve recently rebranded to the JD Kirk VIP Club, and there are about 20,000 people on that, so I’ll email them every couple of weeks, and I’m guaranteed to get something like 500-600 emails back from people just telling me what they’ve been up to and how their day’s going. I love that.

Eastgate by JD Kirk is published by Xertex Media, priced £2.99.

Sophia Gravia is Scotland’s rising star in romance fiction. Nasim Asl talks to her about her rise to literary fame.

Glasgow Kiss

By Sophia Gravia

Published by Orion

What Happens in Dubai

By Sophia Gravia

Published by Orion

Sophie Gravia is certainly impressive – she works as a nurse (as does her protagonist Zara), writes around her shifts, self-published her debut novel and now has bestselling books A Glasgow Kiss and What Happens in Dubai to her name. We met in a Glasgow café, Sophie fresh from a research trip abroad for her next book, and I was blown away by how warm, open, and genuinely grateful she is for the well-deserved success she’s experienced.

A Glasgow Kiss and What Happens in Dubai are the first books you’ve written – and they’ve both done so well. How did they come about?

It was all so random. I was on holiday with my friends, and the night before I’d had a really dodgy date – the panty sniffer one! I put it in the first chapter of A Glasgow Kiss! That was my first online date ever. I told my friends, and they were killing themselves laughing. One of my friends told me to blog it – I’d never blogged anything in my life. Soon after I ended up off work for a while, so thought I’d start blogging anonymously as Sex in the Glasgow City. It got thousands of hits.

Your first online date! That’s really bad luck. Had you written much before writing about your dates?

No. I’d really enjoyed writing in school, but I didn’t feel like my grammar or stuff like that was good enough. I’m a nurse, and my work was really intense during Covid. We had a wellness session one day, where we had to stand up in front of a group and say one thing that we’d done for ourselves during the pandemic. There were doctors standing up saying they’d started playing violin, or abstract painting…when they came to me I just cried and was like ‘I don’t do anything’. I started writing my book that night when I got home. It was really easy to write. The next book was harder because there were expectations!

How was it then, entering the publishing industry, finding an agent, getting signed to Orion as someone who didn’t have any experience with it?

I watched a YouTube tutorial and self-published on Amazon! I couldn’t afford to print it myself or get copies printed to sell. It was mental, it ended up selling thousands. Normally, they sell 200 copies a year that way, but before I got signed, I’d sold over 20,000 in a couple of months. I designed the cover myself, did it myself, but I’m so pleased to have been picked up and have it published with Orion.

One thing I really enjoyed was the dialogue – it felt so real to read, as though I was just sitting in the pub with pals listening to them chat.

A lot of the characters are based on real people – my best friend is totally Zara’s best friend, Ashley. So I was just thinking ‘what would she say?’.

What’s the reaction been to your books from other people you know? How have they reacted to the sex scenes and explicit parts of the novels?

I really worried about it. My family is Catholic, my mum is the holiest person. I told them I’d written a book but that I didn’t want them to read it because it was like 50 Shades of Grey! They were all so proud and really supportive.

Aw, that’s great to hear. Do you tell normally tell the people you date that you write romance books?

I usually put a picture of me holding a picture of my book on my profile so they know straight up, but 95% of the messages I get are from people asking to be in the third one…I often get told bad stories from random people I meet though. I was in a taxi and the driver had read my book and knew who I was, and he gave me the most horrific story you’ve ever heard in your life. I don’t think people would believe me if I put it in the next book!

That must have been awful, because there are some quite graphic things in there already! Let’s talk about that though – because your books are unusual a little in the genre, by being so honest when talking about bodies, and bodily functions, and how things all work. Your writing on sex feels frank and refreshing because you’re not romanticising it.