Nasim Asl is both impressed and disturbed by Heather Parry’s debut, Orpheus Builds a Girl.

Orpheus Builds a Girl

By Heather Parry

Published by Gallic Books

For millennia, women’s bodies have been objectified, commodified and politicised. We can see the battle for women to have the right to make decisions about their own bodies still playing out around the world. In Iran, women are protesting for the right to show their hair in public. In the US this year, the overturning of Roe vs Wade means some women are limited when it comes to making choices about their own bodies.

In her debut novel, Orpheus Builds a Girl, Heather Parry explores how even in death women can lose agency of their bodies to the absolute extreme. She’s crafted a novel that is mesmerising, grotesque, sympathetic and gripping in equal measure. Parry’s work is simultaneously both of our time but could have been written during the original gothic period of literature, so strong is her storytelling voice.

Loosely based on a story featured in the Our American Life podcast, in which a German man working in a hospital became obsessed with a young Cuban-American patient before digging up her body and keeping it in his home, Orpheus Builds a Girl follows a similar plot. The Nazi scientist Dr Wilhelm von Tore – the Orpheus in this tale – flees Germany and moves to the US. Living under a false identity, he works in a hospital. At the same time, we follow the life of Luciana, the titular ‘Girl’, as told through the eyes of her sister Gabriela as the two grow up in Cuba, leave during Castro’s regime, and enter womanhood as immigrants in Florida.

The story is told via alternating chapters, covering different historical periods and the two storylines merge around a third of the way through the novel, when Luciana, suffering from uncurable tuberculosis, meets Wilhelm. Cue his obsession with her, his eventual control of both her dying and dead body and her sister Gabriela’s years long fight for justice and peace. Sounds simple enough, but Wilhelm has been long consumed with dreams of undoing death, and the novel takes a dark and grisly turn; squeamish readers may find themselves skimming certain paragraphs.

While the time jumping between chapters can take a little while to register and adjust to, the two voices are powerful and the characterisation is distinct. It’s obvious which narrator is speaking when, and the use of contrasting language and voice is fascinating. Wilhelm’s chapters are filled with pseudo-scientific vocabulary, and there’s a gruesome viscerality in his descriptions of the body that contrast sharply with his more emotive ramblings. Both characters are consciously narrating and speak directly to the reader – Wilhelm believes he has written a ground-breaking memoir and scientific paper that challenges everything medicine knows about death, while Gabriela is writing emotively to expose Wilhelm’s obvious moral deficiencies and regain some control of her family’s narrative. The domesticity and familial focus of her sections contrast unnervingly with the at-times uncomfortable experience of reading Wilhelm’s interior monologue, which serves to further the moral chasm between the two.

The two characters are worlds and generations apart, but both their geopolitical contexts are fascinating. Parry is successful in constructing believable and fascinating characters, and some of the horror of the novel comes from how firmly established in historical reality the characters are – they feel unnervingly real.

As the story progresses, the characters’ mental states become more and more exposed and the lines between truth and fantasy become blurred, exposed, and blurred again. So persuasive is the voice of Wilhelm that at times I questioned the veracity of the possibility of his experiments, before rapidly reprimanding myself. Credit to Parry’s pen. Though the pacing of the narrative felt slightly imbalanced and the expositionary childhood passages at the start of the novel could feel a little long – especially before the two character’s lives intersect and the narrative thrust really takes shape – the research that went into the historical and political context can’t be underestimated and undeniably contributed to the authenticity of the novel.

Women and power lie at the heart of Parry’s book. The domination and control Wilhelm displays throughout the narrative is best encapsulated as the deranged doctor screams Luciana is his ‘object’ and ‘personal property’. Throughout, Parry explores the ownership of the body in death as well as in life. Some of the most moving scenes in the novel are expressions of sisterhood and love between Gabriela and Luciana, and the gentleness that exists between them even through some harrowing moments is a perfect foil to the grossness of Wilhelm’s narrative. Through the Madrigal family, large themes and topics are exposed – Parry weaves stories of immigration, racism, the American dream, the medical and social treatment of women as well as their sexual liberation, the spectre of fascism, authoritarian regimes and the failure of authorities through the plot.

It’s a novel that feels incredibly timely. Society’s fascination with the macabre is as noticeable as its ever been, if the endless ream of murder documentaries and podcasts available to stream are any indication. At the time of writing, the series Dahmer is topping the Netflix chart. We still have a morbid fascination with humans who represent the worst of us. Taboo subjects are compelling and the theatre of the grotesque is clearly addictive – despite the wishes of victims and their families. Parry makes us question our role as voyeurs in this tradition, and exposes our complicity as violence, death and desecrated bodies are used as entertainment – and more often than not, it’s women and minorities who suffer the most dehumanisation. Luciana is the perfect example of this.

Indeed, it was only as Orpheus Builds a Girl drew to its close, that I realised that in a novel focused so intensely and explicitly on the life, death, body and corpse of a woman, we did not hear Luciana’s voice directly. There’s no justice, no remorse. That in itself, is its own tragedy, and it’s one that Parry exposes with haunting subtlety.

Orpheus Builds a Girl by Heather Parry is published by Gallic Books, priced £12.99.

Fifteen-year-old Cathy O’Kelly lives in an insular world – she’s been bullied, home schooled, and is now going to high school, dreaming of getting the marks she needs to be a proper Scots writer. This time, her bully isn’t in a tracksuit, but an aspiring poet. Emma speaks to Books from Scotland about her new book, and the importance of fostering the Scots language, both on the page and beyond.

The Tongue She Speaks

By Emma Grae

Published by Luath Press

Can you tell us a little bit of what we can expect from The Tongue She Speaks?

The Tongue She Speaks is a book about the Scots language itself, told in Scots. It’s about the barriers Scots speakers face and how this plays out across the generations. It’s also about dreams, music and very much an ode to the emo culture of the early noughties, which was thriving in Glasgow at the time. If you’ve seen Almost Famous, it’s a bit like that, but on a much more intimate stage.

What drew you to 2007 Glasgow and the emo and punk scenes as a backdrop for your story? What is it about that time / place?

During lockdown, I really started to long for a simpler time and that was when I was a teenager. I also found myself watching a lot of YouTube blogs about Y2K nostalgia and had it in my head when I was working on the Scots Warks project – designed to encourage Scots literacy. As part of that, I had to write a creative piece to inspire people to take up the lead, and it’s where the book began. With Scots and nostalgia in mind, it actually got to the point where I was watching videos of my old high school, which was knocked down well over a decade ago. Just imagining the early days of the internet, back when people lived in the real world a bit more, and online was just this dangerous, slightly bizarre new world that everyone was navigating for the first time.

Scots Warks project: https://www.scotslanguage.com/scots-warks

‘Scots is a language. It’s no jist fur poor folk and those who cannae speak English properly’ marks the start of your blurb – can you tell us a little about writing in Scots, and the attitudes touched on in this quote in regards to the legitimacy of Scots?

Despite being very much a proud Scots writer these days, there was a time when I was ashamed of being a Scots speaker – largely as I’d no idea that it was a language and it felt like everyone around me was telling me not to speak it – that it was just bad English. It was only about a decade ago, while studying English in Glasgow, that my good friend and I drunkenly started joking in Scots, and we’ve honestly never looked back. Her name is Lorna Wallace and she’s had huge success with Scots too, which began with a viral poem that was a modern rendition of To a Mouse – Tae a Selfie!

The book explores this further, with Cathy wanting to be a writer, and her bully an aspiring poet – how did you find exploring these tensions while writing about being a writer?

I guess I found it quite easy because it was very much a reflection of my own life in a lot of ways. Like Cathy, I felt the pressure to be something I wasn’t, but it took me a lot longer to find my voice. I spent years to pretending to be everyone but myself. It was only when Chris Agee, a poet who was in residence at Strathclyde University, saw value in my own stories, which came in my own voice, that I started to use it. I’ll always be grateful to him for that. It’s really been a simple case of write what you know.

Your previous book Be guid tae yer Mammy won the Scots Book of the Year for 2022 (congratulations!); continuing from the previous question, why do you feel it’s important we continue to spotlight the thriving work in Scots in its own distinct awards and support such as funding?

I think there’s a distinct lack of Scots voices out there, especially female ones. When we think of well-known Scots writers, it’s typically not women who (currently) come to mind, but I hope it changes and we hear from people of all genders and sexualities.

Fundamentally, Scots is also the mother tongue of 1.5 million people. It’s what I grew up speaking, and it comes so much more naturally to me than English. It feels authentic, and as my work is set in my home city and deals with a lot of lived experience of mental illness, I can’t think of a better way to tell my stories.

Who or what inspires your own work?

My own life – history, art, music. When I was younger, I was really drawn to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s work. He captured what it meant to live in the Jazz Age and I guess I’m trying to do similar, to capture a sense of what it’s like to live now, in my own voice. Even if my work is a total world away from the likes of The Great Gatsby.

Another huge inspiration to me is David Bowie. He said in an interview about twenty years ago that all of his work is about social isolation and rebellion and that really resonated with me.

I also take a lot of inspiration from family members who’re long gone, and all of the poetry from Cathy’s Great Grandfather in The Tongue She Speaks was actually written by my Great Grandfather. I have photograph upon photograph from that time, and I imagine there’s more stories I’ll eventually take from those heirlooms.

What do you hope readers take from The Tongue She Speaks?

I hope that readers see the nuances of PTSD, which Cathy is clearly suffering from. I want people to walk away with a realisation too that bad people don’t always look like monsters – they can be girls on trains pretending to use their God for good, when it’s really bad, and friends who tear others down, then follow it up with intermittent praise (fun fact – it’s called trauma bonding!).

I also hope that readers see the battles Scots speakers face and the courage that it takes to create in the leid. While I wish people could just freely write and use Scots, it’s not currently the case (especially online…), but I hope that changes one day.

The Tongue She Speaks by Emma Grae is published by Luath Press, priced £9.99.

The Banes o the Turas is a poetical translation of and engagement with Turas Viaggio, by the Italian poet, composer, musician, folklorist and friend of Hamish Henderson, Pino Mereu. A portrait of that friendship and Mereu’s visits to Scotland, in keeping with the traditions championed by both poets, this is a poetical owersettin in Scots, and you can read an extract below.

The Banes o the Turas

By Jim Mackintosh

Published by Tippermuir Books

Padstow

May Day in Cornwall, 2016

I

The flauchterin leaves o the aik

shrood the gliskens o sun, the tendrils

o this licht scatter

oan the brae-side, rinnin oot tae the bay.

Oan this whitelin saun ah can rest

easy, chasin the douce an lusty spring

gust aboot ma mou.

Ah’m in Padstow.

The drumtap o vyces herald

the stert o the Festival oan this

May mornin. It’s a feast, it’s a feast: abdie

up fer jiggin wi the twins, Eros an Tanatos.

Unite and unite and let us all unite for

Summer is i-come-un today

And whether we are going we all will unite

In the merry morning of May.

The tree of life is weytin while

Martin plays the Siege o Delhi,

sic a pure an simple magic, lowin wi passion

– a tune o hert-gled daeins an dremes.

It’s magic, naethin repeatit or replenished,

aa’thin bursts oot, wi nae dreid they

hae a go at Life an Daith an vyces born free

champin at the bit tae brak oot fae thay shores.

Under the earth I go declares Bardie.

Fechtin intae the nicht, oan an oan

intil the skreich o day, ilka life

ready tae be born aince mair…ah gie masel

up tae this sang an stert oan my wey.

Lunis agro

Martis frittu

Mercuris crudeles

Giobia immortale

Chenabara nudda si ottenet

E, durche si Sabadu – torture su die

e gloriosa Dominiga, repose in pache

Amen

*

Spittal o Glenshee

The Hamecomin, 2015

I

The schule o hailly wirds shuttert ticht.

Fae the windaes anely the lang-day derkens

while the corbies craw,

loupin an jiggin abuin the deid-stanes.

Fae there, atween-the-lichts he venturit

bi Ben Gulabeinn

wha’s dauchy neb cockit a snoot

yet wi open airms tae aa the carnaptious,

syne wi a blinterin stretch touched the lift

wi the mortal grains o yer saul.

The fairies o Glenshee jiggit wi glee,

liftin yer hert wi aa the sangs o oor kin

tae bring ye hame laden wi a kist o riches

oan the wings o freedom’s flicht.

Cam aa ye, gies a sang Hamish!

A joyfu sicht whaur vyces cam thegither.

Ah ken ye’re here:

the vyce o the wind

oor ain vyce

the vyce o this Earth

the vyce o seelence

the vyce o the stanes

II

Ben Gulabeinn, a braith o life

– wirds findin strenth, text

blessit wi the air yer saul

wis aye seekin.

A lichtsome speerit wyves destinies

wi meestery, mindins o freedom fer

aa the days o life – the hailly age:

renouncin, faur aback yet aye the wey forrit.

Sheddins o keppins, chyces, tellins,

graftins: a lanely life oan

the wark-road wi his wirds sauf

unner his airm, a daily darg chasin licht

at reflecks an inspires.

Wi aa its lowse verse, its forms,

its spaces fer new creations, freedom

wi a cost measurt bi its limits.

And wi luve, respeck, forgieness,

ilka horizon a kythin o kennin

lik a guid craftsman embraces

his kist o craft or the tylor

his fine claith.

Lichts turn tae waves o derkness,

sheddas in the muinlicht

– a triumph o the lown.

The seelence is the derk innocence.

There’s nae sorra in the unco

buryin o the banes.

Here, the stoor o the turas

settles aince mair.

An wi yon beamin

glow ayont wirds, Hamish

fer aye oor lad o pairts

bides eternal.

The Banes o the Turas by Jim Mackintosh is published by Tippermuir Books, priced £9.99.

Across 2022, Publishing Scotland will be curating a series of online content to tie in with Visit Scotland’s Year of Stories. Each month we will share the features, profiles and interviews that you can find over on their website.

You can visit Publishing Scotland’s Year of Stories homepage here.

During September, Publishing Scotland’s #YS2022 theme was REFRESH.

Each month Publishing Scotland will be offering Publisher Spotlights, so you can get to know some of Scotland’s publishers. Catch up with the latest profiles.

Publishing Scotland spotlight Scotland Street Press

Publishing Scotland spotlight Association for Scottish Literature

Each month Publishing Scotland will have features too, including book recommendation lists and author interviews.

Click here to read an interview with Katharine Hill about her book A Mind of Their Own.

To read an interview with Joe Donnelly about his book Checkpoint, click here.

To read an interview with the Hebridean Baker, Coinneach MacLeod, click here.

If you want to take part in the Year of Stories, follow the hashtags #YS2022 and #TalesofScotland, or visit the VisitScotland website.

Singer-Songwriter James Yorkston has followed up his first novel, 3 Craws, with this latest release, The Book of the Gaels, a tender, raw, and funny tale of two young boys travelling to Dublin with their father while they battle poverty and grief. We’re delighted to share this extract with you.

The Book of the Gaels

By James Yorkston

Published by Oldcastle Books

1

Creagh, West Cork, 1975

Due to the proximity of the house to the lough, or perhaps more accurately, the proximity of the house to the cess pit, there was always an army of flies around, and they were more often in the house than out. I’d say the constant rain was an irritation for them, and here inside they’d find enough scraps and scrapes of food to get by. We’d watch them squadron around the house, up and down the staircase, in and out of rooms, groups of twenty or so, sometimes interacting with smaller groups, buzzing, conversing. We’d be sitting there, my wee brother Paul and me, commentating on their battle manoeuvres, the flies from upstairs being the rotten Jerrys, and our brave Scottish brigade gallantly guarding the foot, the exit to outside. What helped our fantastic little game was that on occasion a fly would all of a sudden drop out of the air, dead. It’d lie beside us, give us a last shimmy, a shake of the legs and be still.

We discussed when it had last been to Confession. Would its soul be clean? Bless me, fly-father, for I have sinned. It has been two long minutes since my last confession. In that time, I have landed on an apple and wandered around a bit before taking off again for the big light, you know, the one in the kitchen…

Once, a fly death-valleyed in Paul’s hair, and sensing it wasn’t on the hallowed ground of the window sill or the staircase, or the sink or the fruit bowl, or a shoe or drink, it fuzzled for a good minute longer than we were used to. Paul was screaming Get it off ! Get it off ! And I was dancing around him like a puppet master, invisible strings to Paul’s head, scared to touch him, scared to see the fly. When the buzzing stopped, Paul sat on the stairs weeping and I, bravely, looked through his hair and removed most of the fly.

Is it all gone? It is.

It wasn’t, but the most of it was. I think maybe I lost a leg with the combing, and maybe a wing, but nothing one wouldn’t get riding down the path outside on a pony or a bicycle.

Once the bodies were dead for sure, safe, still, we’d pick them up by shuffling them on to pieces of paper using one of our father’s old books, until we had a bunch, twenty or so, then we’d carefully carry them to the top of the stair. We’d position ourselves and wait, waiting for the next battalion of flies to emerge from below. When they arrived, or when we had become bored, we’d throw the entire lot of carcasses into the air and down the stairwell, shouting Attack! Attack! And Hiawatha!

I have no idea what the other flies thought, if anything. Seeing their dead cousins springing briefly back into life then falling like a stone once more on to the ribbed stair carpet below.

Next time we scooped them up, they’d be missing legs, half their bodies, wings… Where did it go, all this excess?

Come supper, I’d stir my soup with caution.

4

The rain came that evening, and it brought us outside. Father appeared, grinning – Come on! – Paul and me looked at each other and prepared for the onslaught that awaited. As father pulled on his boots, we added layer upon layer, all our jumpers and shirts, followed by the big woollen beany hats that Mrs Cronin from up the lane had knitted us, our scarves, and finally our coats. We knew what’d be up and sure enough, within moments father had us leaving the house and walking outside, him striding quickly ahead, then returning and grabbing my own hand, Paul holding my other and – off we went, in procession, down to the lough. We’d learnt not to grumble, for this would be a happy time for us all. Father couldn’t complain about the weather, after all it was him who was dragging us now right into the heart of it. We began the slow freeze and curse the lack of second trousers or be grateful we remembered all our socks. Past the farms, sensible dogs pricking up their ears and seeing us approach, but them being keen on being dry and barking only, not charging towards us. Father picked up a long stick anyway, just to wave, beckon with. We continued on, father’s speed, us slipping behind him on the once-tarmacked road, long now defeated by grasses and wildflowers. We slipped into the forest, offering a small degree of cover but nothing really, almost bigger raindrops now, collecting on the canopy and falling far down on to us.

Whack! Right on the nose.

Look down, watch my step, avoid the sticks, the slips, passing occasional ruined buildings, ancient tracks, heavily mossed walls…

…and finally out, out of the forest and by the lough, the rain now tipping upon us and us – well, my father – hysterical with the noise – at least, I’ve always thought it was the noise, the beating of the rain upon the lough, the lough surrounded by forests and mountains on each side and the roar of the falling weather reverberating all around. There was a car there too, parked a good few stones’ throw away, but they had a motor running and father looked to them anxiously, slipping his face from them to the lough, them to the lough, until they turned their motor off and he relaxed There you go and concentrated on the lough.

He was hypnotised, staring out there. There was nothing else to hear, nothing else to think about, just the enormity of the body of water itself and the huge, vacuumed swell of the rainfall. The incessant downpour, constantly slapping our backs, felt like a massage, more distraction from real life, more putting us firmly here in the now.

The wet began to trickle through my defences and down my neck. One tiny river, then another. Reach my tightened waistband and circle around, tickling. I’d ignore it, best I could.

Looking up at father, his eyes were wide, occasionally wiped by a naked hand, he was inviting the weather, challenging, revelling, swimming in it. His jaw was slammed shut, slightly shaking, steam piling out of his nostrils like a bull, blinking his eyes as if this dwam was delivering some magical, powerful charm. Shaking himself from a momentary slumber then back, staring once more, eyes darting left and right but always, always returning straight down the line, forwards, as far as the eye could see, a mile or so across into the inlet where this giant, deep lough met the Irish Sea.

The Book of the Gaels by James Yorkston is published by Oldcastle Books, priced £9.99.

David Robinson is thrilled to be taken to 1920s London by master storyteller, Kate Atkinson.

Shrines of Gaiety

By Kate Atkinson

Published by Doubleday

‘“Is it a hanging?” an eager newspaper delivery boy asked no-one in particular.’ That’s the first sentence of Kate Atkinson’s new novel Shrines of Gaiety, and already the hook is in. (Do you want to read on? Of course you do.) No, it isn’t a hanging, but that’s a reasonable question all the same, what with the crowd of drunken toffs outside Holloway so early in the morning, the press photographers waiting expectantly, demonstrators already there with their placards, and the police keeping an eye on everything in the background. And of course, what with it also being 1926, when the gallows in England’s only female-only prison were still in occasional use.

If you want to know why Atkinson is such readable writer, you could do worse than look in depth at that opening scene. In just five pages, she not only introduces its central character – notorious Soho nightclub owner Nellie ‘Ma’ Coker, who is being released from prison that day – but five of her six grown-up children. On top of that, the novel sets up a secret mission: a police chief inspector has summoned an undercover agent to the scene who’ll be able to recognise Coker and her children in the future. That’s eight key characters we’ve met for the first time, each differentiated with either dialogue or description, and yet – and this is Atkinson’s real skill – so subtly that you hardly notice it.

Think about it. If you (I presume) or I attempted such a thing, by character No 3, the reader might already be tiring of so many introductions. Instead, we see the scene through the newspaper boy’s eyes as he shoves his way through the crowd towards the gates. They’re quite imposing. How high are they? ‘If there had been three of the boy, each standing on the shoulders of the one below, like the Chinese acrobats he had seen at the Hippodrome, then the one at the peak might have just reached the arched apex of the doors.’ Exactly. And right there you have one of the reasons I love reading Kate Atkinson: her prose is so rich that a description of one thing invariably becomes a description of two or three others.

So when Holloway’s gates open and a woman comes out and the crowd cheers, the newspaper boy can’t understand why some of them are shouting ‘Jezebel!’ at her. This woman is dwarfed by bouquets but is so old that she doesn’t look like anything that the boy has heard of Jezebels. The girls surrounding Ma Coker – daughters, we’ll soon find out – remind him of the dancers he’s seen at matinees in a nearby theatre, where the doorman, ‘a cheerful veteran of the Somme’ let him in for free. All the time, details roll into Atkinson’s prose at just the right moment, the focus becoming clearer with each one, the vignette moving from two dimensions to a solid, load-bearing three. We won’t need the newspaper boy again, apart from a sentence right at the end, but he’s served his purpose. He can go.

Introductions over, we are soon in the middle of what is, in the words of the title of the novel being written by Ma Coker’s youngest son Ramsay (think Roman Roy in Succession), The Age of Glitter. This is the frenetic world Evelyn Waugh would conjure up in Vile Bodies, where the Bright Young Things pursued a frenetic round of heavy drinking, party-going and promiscuity. If you didn’t think Baldwin’s Britain did Bohemia, look again at the clubs Ma Coker ran – at The Pixie, where you might come across Tallulah Bankhead or the King of Denmark; or The Amethyst, where the Aga Khan was a regular, where dance hostesses could earn £80 in a good week and where profits, piling up at more than £1000 a week, were ‘better than a goldmine’.

For all that, Ma Coker – modelled, apparently, on Kate Meyrick, the Irish queen of Soho clubland in the 1920s – has to contend with the attentions of the police. The good cops, led by Chief Inspector Frobisher, want to close her down and ask a York librarian, in town to check on the whereabouts of two local girls, to help them infiltrate The Amethyst and report on any racketeering and prostitution she finds there. The bad cops don’t mind turning a blind eye in exchange for backhanders, and some of them even have club management ambitions of their own. So, too, do the London crime syndicates.

All I need to say about the plot is that at some stage almost all of these characters will either rub each other up the right way (romance) or the wrong way (violence) and very occasionally both. Those two girls from York seeking their fortune on the paved-with-gold streets of London crash through the intricate plot like fairground workers on the waltzers, giving it a spin as they go. Will they end up on the mortuary slab like so many girls down from the provinces seem to be doing that year? Or will they become demimondaines or drug-dealers, private dancers or police informers, lovers or losers? Atkinson’s plot is so entertainingly baroque most of these possibilities remain wide open for most of the novel.

Frankly, I don’t read Kate Atkinson for plot. It’s there all right, and it’s thought-out and full of enough twists to keep the reader turning the pages. But most of us KA fans would probably keep turning those pages anyway. Or at least I would.

Why? I think it boils down how effectively she sets her scenes. Her descriptions are both concentrated and loose. Let’s start out with concentrated. Here’s how she describes Ma Coker’s second-eldest daughter: ‘Betty was hard-nosed and occasionally mawkishly sentimental, a combination shared with her mother and many dictators both before and since’. See what I mean? It’s what I was trying to say about that opening chapter: she invariably illuminates more than merely the subject supposedly in focus.

What about loose? I like this about Atkinson’s writing even more. Here’s Gwendolen, the York librarian, out shopping in Regent Street. She passes a blind cornettist playing ‘What a Friend We Have in Jesus’ (‘Do we, Gwendolen wondered. She had lost any religion she might have once had’) and she starts remembering how the soldiers used to sing ‘when this bloody war is over’ to the hymn’s tune and how she’d hear them singing it when she was a nurse on the Western Front, and how they’d apologise and say ‘Sorry Sister’ and how embarrassed they were when, in extremis, they’d swear in front of her.

What I’ve described in a paragraph takes up over a page in the text (Page 85), and it absolutely deserves to. But you can see how clearly one thought flows from the next, and also note how the whole thing starts: those parentheses in which a character thinks out loud are an Atkinson trademark, and there’s one on most pages. Gwendolen’s musings in Regent Street spiral, quite naturally and completely credibly, down towards death and loss, but Atkinson has a wonderful ability to follow her character’s thoughts in the opposite direction. The scene in which Ramsay, having just finished The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, decides to write a crime novel of his own is a typically hilarious example.

There’s a lot happening in this novel – cliffhangers and comedy, drugs, dancers, double-crosses, maybe murderers too – and it happens at a frenzied pace. The plot is like the dance floor of The Amethyst, crowded and showy and sparkling, and, at the same time, edged with darkness and crime. Bringing all of that to life would be beyond most writers, but the way Atkinson handles her material is not only entertaining but shimmers and shimmies with style.

Shrines of Gaiety by Kate Atkinson is by Doubleday, priced £20.

Scotland Street Press will be publishing a collection of poems from Alan Spence from his time as Edinburgh Makar. Enjoy these two poems from the collection, and then get yourself the whole book – it’s a marvellous celebration of the city.

Edinburgh Come All Ye

By Alan Spence

Published by Scotland Street Press

EDINBURGH COME ALL YE

From the Mediterranean to the Baltic,

from the Caspian Sea to the Atlantic,

folk have foregathered here in Edinburgh

on this bright autumn day they’ve come together.

In a world turned tapsalteerie, upside down

they’ve come from a the airts to this old town.

Let’s sing a great Come All Ye, let it ring,

a song of peace and oneness, gathering

in strength from everyone who gives it voice,

sung clear and pure and from the heart. Rejoice

to hear it rise and swell, anthemic, free.

Our oneness is our true humanity –

this city every city, this nation

the world. Beyond all separation,

division, sing einheit, l’unita

unidad, aonachd jednosc, jednota…

and every other way of saying it.

Oneness. Come All Ye. Celebrate. Sing it.

THE OLD TOWN

In a poem, in a dream, I turn and find myself

walking through the Old Town. Is it Edinburgh?

Krakow? In the poem, in the dream, it’s both,

somehow, it’s both at the same time.

I walk on down the Canongate to Market Square.

It’s Festival time, there’s jazz in the streets, poetry

in the air. I turn and find myself in a poem

in a dream. Where? Here in this bright room.

Stevenson and Conrad trade stories, tell their tales,

travellers come home at last to this place.

Milosz and MacCaig flyte, take flight, a zen calvinist,

a catholic atheist – their ideas fizz and flare.

Language is the only homeland, says Milosz.

MacCaig responds, My only country is six foot high…

Beyond the poem, the dream, the world

is turning mad, hellbent on self-destruct.

So praise them, these sister-cities of literature,

as one, Edinburgh-Krakow, Krakow-Edinburgh,

as one, holding to the dream, the poem,

to language, our homeland, our hope.

Edinburgh Come All Ye by Alan Spence is published by Scotland Street Press, priced

In Arun Sood’s tender New Skin for the Old Ceremony, four old friends embark on a road trip around the Isle of Skye. They reminisce on a similar motorcycle journey they once made in India and reflect on how their lives have changed as they’ve grown. Nasim Asl spoke to Arun ahead of his novel’s publication.

New Skin for Old Ceremony

By Arun Sood

Published by 404 Ink

How are you feeling about the release of New Skin for the Old Ceremony – your debut novel?

There is a sense of nervous anticipation that does come with the excitement. If you put a little part of yourself out into a public space, there’s a bit of nervousness that comes with it. It’s fiction, but as fiction does, it draws on experience and themes that can be personal or important to you. There’s so much attention on authorial intention that there’s a bit of apprehension that comes with themes that come close to your own personal life and how they might be taken.

I know you’re a poet too, and I was struck by the poetic nature of your prose style in the book. Why did you want to write this story?

A friend once said to me, if you’re thinking of writing a book, write the book you would want to pick up and would be excited by. I’ve always been excited by the idea of an Easy Rider-esque road narrative, but transposed to Scotland. This idea of friends, not a lot happens aside from the unfurling or coming together of the relationships, but interwoven with themes of nationalism, populism, race, and fragmentary friendships. A simple road narrative allows for these bigger themes to be explored. It was liberating to use language in a new way and to be playful. I enjoyed writing it, but I had to treat it like work to get the novel finished.

It does feel like a cinematic novel, especially at the beginning when we’re introduced to each character in turn, then dip in and out of the past and present.

In terms of the writing process, it was as inspired by cinema as it was by other fiction. I was thinking of cinema with the character introductions, like flashing and cutting between them. And the jumps in time between north India and Skye…The relationship between road movie and travel writing is interesting. Road movies are derivative of epic travels, journeys like Homer.

Let’s talk about the title – why did you go for that Leonard Cohen album as the title for the book?

I always listen to music when I’m writing. That album was definitely played a lot! I did listen to other albums while writing other parts of the book, but these four characters form a collective bond through listening to this album in the early stage of the book. The album congeals their special friendship – even as their friendships disintegrate, the art and the album stay. We all have that music or album or song that takes us back to a place. I also quite like the formal fact of having chapters based on and named for the 12 tracks of the album. When I was thinking about the chapters, I’d think about song lyrics in a particular track, and how they might relate to what happened in that chapter.

And the book’s subtitle – a kirtan – what does that mean?

It’s an Indian classical musical form, which usually derives from or is centred on spiritual or Vedic texts. I did it in this bashful, non-traditional way, where the music that is being derived is the Leonard Cohen album, rather than this spiritual Vedic text. I love that album. I listened to it a lot when I was travelling in India when I was 19.

One thing that weaves through the experience of two of the characters and the story is the experience of being mixed-race and trying to find belonging in two different cultures.

It felt natural to write that into the characters because it’s something I’ve experienced and thought about, that type of journeying, or ‘roots tourism’. It does crop up in the first section of the book, especially with Raj. He feels he should connect to India, but he gets there and feels dislocated from it, which is difficult for him to come to terms with, whereas Viddy realises and accepts more easily the dualities in her identity. In terms of the form of the novel, that’s why I’ve got the Kirtan and smashed it with Leonard Cohen because being mixed or growing up between cultures or in diasporic cultures, it can be difficult to know what belongs to you or what doesn’t. Some of the frictions or conversations Raj and Viddy have are derived from some of my own musings on what it is to be between cultures, including growing up in a nation like Scotland with a very strong national identity.

A large part of the book does indeed take place in Scotland. What was it like writing the landscape and trying to capture Scottish identity?

Even regionally in Scotland there are very strong identities and there can be sometimes abrasive attitudes towards east or west. It was interesting to capture Liam being very rooted in his Glaswegian identity, which was very different to Bobby, who’s from Aberdeenshire. Then you had Raj moving from the east to the west, then they all end up in the Northern Highlands and Islands. I wanted to explore how these regional identities are bound under notions of nationalism, of Scottishness. As much as Bobby and Liam have jibes to each other, there’s a resolute notion of them being rooted in being Scottish. And the timeframe of the novel goes from Blair’s Britain to post-independence referendum. So, a lot happens in Scotland during those years.

There’s a real contrast between that world and the earlier trip to India.

Both locations, Skye and North India, are prone to being romanticised in ways that can sometimes be problematic or far removed from the reality of actually knowing these places or living in these places. Liam’s romanticisation of Northern India as this place of spirituality, full of yoga and gurus and enlightenment is exposed as ridiculous in the face of the socio-political reality, but it remains an alluring place for him. Similarly, Bobby wants to have this romantic notion of Skye but is conscious that it’s problematic to think of Skye as a wild, untouched place when it’s been exposed so much in recent years. It’s not actually somewhere people can go to live a wild, free existence. These are complex places in themselves.

New Skin for Old Ceremony by Arun Sood is published by 404 Ink, priced £9.99.

As part of the Year of Scotland’s Stories, we are running a series of Responses on BooksfromScotland, commissioning writers to respond to books from the publishing membership, engaging with work in different ways. For September, and to celebrate the recent Booker-longlisting of Graeme Macrae Burnet’s latest book Case Study, fellow crime writer Tariq Ashkanani revisits his earlier work His Bloody Project.

His Bloody Project

By Graeme Macrae Burnet

Published by Saraband

To mis-quote Shrek: His Bloody Project has layers.

Its outermost is also its simplest. At its heart, this is a crime novel. It has a homicide, it has a villain. But unlike most of his peers, Graeme Macrae Burnet begins his story at the end – with the reveal of the murderous acts and their perpetrator’s admission of guilt.

Peel that layer away. Reveal the narrative structure beneath.

His Bloody Project is presented as something akin to a ‘found footage’ movie. Burnet opens with a brief in-person explanation for having pulled together various pieces of documentation during his own historical research, before providing them to the reader to work through. This cracking of the fourth wall is something which makes for a refreshing twist on the reader’s own role in the story (other excellent examples of this style include Joseph Knox’s True Crime Story and the works of Janice Hallett).

But go on, peel that layer away too. Who is the main character of this story?

That would be young Roderick Macrae. The son of a crofter in the small village of Culduie in the north of Scotland, he lives a fairly pitiful existence scraping a living from the soil along with his family and neighbours. We learn of his character early on: His Bloody Project opens with a selection of statements from Roderick’s contemporaries. Some say he is wicked, others say he is not; some say he is stupid, others that he is highly intelligent. Right from the start we are presented with these contrasting views, with these uncertainties. Right from the start we are presented with the ongoing question which will linger over the entire sorry tale: who is Roderick Macrae?

Well, keep on peeling. We’re not there yet.

Most of the book itself is made up of Roderick’s memoirs. Written after the fact, in an Inverness prison awaiting trial. In eloquent style, he tells us the sad tale of his life in Culduie and of the hardships that everyone faced. He also tells us of Lachlan Mackenzie – the local constable, eventual murder victim and a most horrible person, obnoxious and leery. Mackenzie wages a war-of-sorts against Roderick’s family, and knowing his fate in advance only serves to drape proceedings in a melancholy dread.

Mackenzie is described as a brute who has made difficult many of the villagers’ lives – none more so than Roderick’s father, whose futile attempts to get out from under Mackenzie’s thumb have backfired repeatedly. Further, Roderick’s sister has fallen pregnant with Mackenzie’s child; a relationship in which his sister likely had little choice in.

It is testament to Burnet’s writing that when Roderick finally embarks upon his journey to murder Lachlan Mackenzie, the young man has the reader’s understanding, if not their sympathy.

Everything in this section is told from Roderick Macrae’s point of view. The reader is given no cause to doubt him, the boy’s soul seemingly laid bare: his fears for his family’s future, his despair at his father’s feud with Lachlan Mackenzie, his shame in being utterly unable to successfully pursue Mackenzie’s daughter, Flora. Indeed, Roderick has already admitted his murderous deeds, what reason does he have now to conceal anything?

And then, of course, the final layer is peeled back.

Because this found footage style of writing isn’t just an entertaining way to tell a story, it’s also an incredibly effective method of constructing unreliable narration. In focusing the reader’s attention on Roderick’s version of events – and doing so in a believable way – the impact is all the more keenly felt when presented with the medical examiner’s reports into Roderick’s victims. Plural, of course, because along with Lachlan Mackenzie, Roderick has also killed his daughter, Flora, and his infant son. Worse, Flora’s genitals have been brutally mutilated.

It’s a shocking reveal. One that works all the better for the cold, emotionless way it is handled. In contrast to Roderick’s emotional journey of self-destruction, the medical report is detached and impassive, almost chilling. Suddenly the reader is forced to question the entirety of Roderick’s story. That opening proposition, first asked as a result of the conflicting statements from the Culduie residents, rears its head once more: who is Roderick Macrae?

From there, the novel dives into this issue with aplomb. Interrogation and musings by experts in psychology and ‘mental science’ follow, before both versions of Roderick are presented to the reader by way of that classic twofold proposition: the courtroom drama. Here, the disparity is on full display between those of working class and those who would view themselves as educated (and if not high society, then at least higher than those living in Culduie).

Experts surmise that criminals must be deformed in some way – there is mention of webbed fingers or prominent cheekbones. They consider women who die in childbirth to suffer from congenital weakness, and that an entire class of people exist who are incapable of experiencing boredom, who are suited mainly for repetitive and undemanding labour. Time and time again, the status of Roderick’s mind is called into question. Can a boy who commits these crimes be in full control of his faculties? Can the performing of such brutal acts be proof itself of insanity?

Finally, the reader is asked to be the jury of the story they have just finished, and although Burnet provides a firm narrative ending, it is not necessarily a conclusive one.

With the final layer removed, the core of His Bloody Project is at last exposed. At its widest, it is many things. It is a contemplation on free will and the mental intent required to commit a crime. It is a commentary on social inequality and the prejudices of those with supposed evolved sensibilities. It is a con – albeit a wonderful one – that passively invites the reader to pull the wool over their own eyes before letting it fall away.

But it is also simply a collection of documents, gathered together and presented without any overt attempt to trick or fool. Indeed, as Burnet states in his introductory remarks, it is left to the reader to reach their own conclusions, and to solve the question that has hovered over them this entire time, lingering on their shoulder, watching them turn every page.

Who is Roderick Macrae?

His Bloody Project by Graeme Macrae Burnet is published by Saraband, priced £8.99.

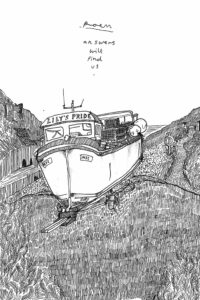

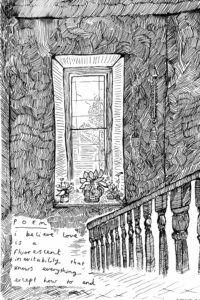

In 2019, Gommie began walking the coastline with nothing but a backpack, tent and collection of pens, in search of hope during increasingly hard times. i am ill with hope captures this – the ongoing journey, poems, illustrations, offering bitesize snapshots of hope to enjoy. You can read some poems and see some of the illustrations below.

i am ill with hope

By Gommie

Published by Salamander Street

POEM

I woke up

With nothing

And I still

Felt

Love.

I KNOW YOU ARE LONELY

I know you are lonely.

And hurt.

Your heart has been broken

And you stand in front of the dry leaves

And say you match them.

You don’t.

You are the pink and the blue and the red

All living next to each other

With no one dominant colour.

You are what makes my pen move.

You hug puppies

The same way I wish I could write poetry.

You champion those without a voice.

You hide my face with your kindness.

I know you are lonely.

And hurt.

You are just like me.

I am the left foot of Philip Guston.

You are the right foot of Agnes Martin.

You are Judy Chicago’s purple plate.

Your thoughts wrap around words as snug as Christo

and Jeanne-Claude.

Believe me, equilibrium doesn’t exist without the U-Turns.

So I celebrate you.

In Procida.

Under Branch Hill Pond.

In the Louvre

Drawing pictures of tourists.

Stripped bare with Giacobetti

And using the humble perspective of time

As an interior decorator that

Hangs all good things to come.

I know you are lonely.

And hurt.

You are just like me.

But I also know you love dolphins

And believe that every romance is an essential journey.

You pick Renoir’s flowers

And I know you would never, never, take any of the

moments that hurt back.

No matter how much you miss them,

You’re still here.

So sleep with the ravens.

Be lost in illumination.

Art is our phenomenon.

And remember it is falling down these disguised pits

That makes life

So

Damn

Magnificent.

You uplift me.

You make me want to build a ship,

Sit on a long table with you and

Eat pancakes on your birthday.

Understand Italian Baroque more.

Walk down the catwalk with Kimono.

Go on a tree adventure with Hockney.

Let him whip me.

I know exactly what it is you make me want to be.

You make me want to be.

I know you are lonely.

And hurt.

You are just like me.

POEM

If I do

The right thing

Today maybe

Tomorrow my life

Will

Be better.

i am ill with hope by Gommie is published by Salamander Street, priced £12.99.

In the latest work from Jim Crumley, dubbed “the pre-eminent Scottish nature writer”, Seasons of Storm and Wonder considers the natural life of the Scottish Highlands, bearing witness to the toll climate change is already taking on our wildlife, biodiversity and more. Read an extract from the beginning of the book below.

Seasons of Storm and Wonder

By Jim Crumley

Published by Saraband Books

I was born in midsummer, but I am a child of autumn. One September day in the fourth or fifth autumn of my life there occurred the event that provided my earliest memory, and – it is not too extravagant a claim – set my life on a path that it follows still. I was standing in the garden of my parents’ prefab in what was then the last street in town on the western edge of Dundee. An undulating wave of farmland that sprawled southwards towards Dundee from the Sidlaw Hills was turned aside when it washed up against the far side of the road from the prefab, whence it slithered away south-west on a steepening downhill course until it was finally stopped in its tracks by the two-miles-wide, sun-silvered girth of the Firth of Tay at Invergowrie Bay. Then as now, the bay was an autumn-and-winter roost for migrating pink-footed geese from Iceland; then as now, one of their routes to and from the feeding grounds amid the fields of Angus lay directly over the prefab roof.

I can remember what I was wearing: a grey coat with a dark blue collar and buttons and a dark blue cap. So we were probably going out somewhere.

Why am I so sure it was September and not any other month of autumn or winter or early spring? Because it was the first time, and because for the rest of that autumn and winter and early spring, and ever since, the sound of geese over the house – any house – has sent me running to the window or the garden. So was established my first and most enduring ritual of obeisance in thrall to nature’s cause. And so I am as sure as I can be that the very first time was also the first flight of geese over the house after their return from Iceland that September; that September when I looked up at the sound of wild geese overhead and – also for the first time – made sense of the orderly vee-shapes of their flight as they rose above the slope of the fields, the slope of our street, up into the morning sunshine; vee-shapes that evolved subtly into new vee-shapes, wider or longer and narrower, or splintered into smaller vee-shapes or miraculously reassembled their casual choreography into one huge vee-shape the whole width of childhood’s sky.

But then there were other voices behind me and I turned towards them to discover that all the way back down the sky towards the river and as far as I could see, there were more and more and more geese, and they kept on coming and coming and coming. The sound of them grew and grew and grew and became tidal, waves of birds like a sea, but a sea where the sky should be, and some geese came so low overhead that their wingbeats were as a rhythmic undertow to their waves of voices, and that too was like the sea.

When they had gone, when the last of them had arrowed away north-east and left the dying embers of the their voices trailing behind them on the air, a wavering diminuendo that fell into an eerie quiet, I felt the first tug of a life-force that I now know to be the pull of the northern places of the earth. And in that silence I stepped beyond the reach of my first few summers and I became a child of autumn.

And ever since, every overhead skein of wild geese – every one – harks me back to that old September, and I effortlessly reinhabit the body and mindset of that moment of childhood wonder. Nothing else, nothing at all, has that effect. I had a blessed childhood, the legacy of which is replete with good memories, but not one of them can still reach so deep within me as the first of all of them, and now, its potency only strengthens.

It would have been about thirty years ago that I first became aware of the Angus poet Violet Jacob, and in particular of her poem, The Wild Geese. It acquired a wider audience through the singing of folksinger Jim Reid, who set it to music, retitled it Norlan’ Wind, and included it on an album called I Saw the Wild Geese Flee. I used to do a bit of folk singing and I thought that if ever a song was made for someone like me to sing it was that one, but I had trouble with it from the start. My voice would crack by the time I was in the third verse, and the lyrics of the last verse would prick my eyes from the inside. The last time I sang it was the time I couldn’t finish it.

Years later, I heard the godfather of Scottish folk singing, Archie Fisher, talking about a song he often sang called The Wounded Whale, and how he had to teach himself to sing it “on automatic pilot”, otherwise it got the better of him, but I never learned that trick. Even copying out the words now with Violet Jacob’s own idiosyncratic spelling, I took a deep breath before the start of the last verse, which is the point where the North Wind turns the tables on the Poet in their two-way conversation:

The Wild Geese

“Oh tell me what was on your road, ye roarin’ norlan’ Wind,

As ye cam’ blawin’ frae the land that’s niver frae my mind?

My feet they traivel England, but I’m deein’ for the north.”

“My man, I heard the siller tides rin up the Firth o’ Forth.”

“Aye, Wind, I ken them weel eneuch, and fine they fa’ and rise,

And fain I’d feel the creepin’ mist on yonder shore that lies,

But tell me, as ye passed them by, what saw ye on the way?”

“My man, I rocked the rovin’ gulls that sail abune the Tay.”

“But saw ye naethin’, leein’ Wind, afore ye cam’ to Fife?

There’s muckle lyin’ ’yont the Tay that’s dear to me nor life.”

“My man, I swept the Angus braes ye hae’na trod for years.”

“O Wind, forgi’e a hameless loon that canna see for tears!”

“And far abune the Angus straths, I saw the wild geese flee,

A lang, lang skein o’ beatin’ wings wi’ their heids towards the sea,

And aye their cryin’ voices trailed ahint them on the air –”

“O Wind, hae maircy, hud yer whisht, for I daurna listen mair!”

Seasons of Storm and Wonder by Jim Crumley is published by Saraband Books, priced £25.

Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape from Scotland with the help of Flora Macdonald is one of Scotland’s most iconic stories. Flora Fraser, in her biography of the young heroine, finds a woman that experienced so much more in her life. We speak to her about her latest book.

Pretty Young Rebel: The Life of Flora Macdonald

By Flora Fraser

Published by Bloomsbury

Can you tell us a little bit of what we can expect from Pretty Young Rebel?

Flora’s story could well be told as a historical novel. Her life is so packed with romantic and dramatic incident. But I am a historical biographer, and so the book is based on documents in the Royal Archives, in the National Library of Scotland, in the British and National Libraries, in the US Library of Congress, and in other repositories.

For those unfamiliar, who is Flora Macdonald, and why is her story so significant?

Flora belonged to the Macdonalds of Clanranald, and grew up on a tack, or farm, adjacent to the residence of the head of the clan and his wife, ‘Lady Clan’ on Benbecula in the Western Isles. While the Clanranalds were Catholic, Flora’s maternal grandfather was known as ‘the Strong Minister’, and Flora was all her life a staunch Presbyterian.

As a young gentlewoman on the Long Island, as the Western Isles were then known, Flora was a key player in the 1746 escape of Bonnie Prince Charlie from Redcoats, or Hanoverian army officers and men, from the Uists to Skye. Following which, she is taken prisoner and sent to London for trial.

Returning to Skye as a Jacobite heroine, she lives quietly with her husband and seven children for a time. But economic distress impels them in the 1770s to emigrate to the British colony of North Carolina, where she is immediately swept up in the American Revolution.

The family takes the fatal decision to stay loyal to the Crown, and Flora’s husband is taken prisoner. Flora, in her early fifties and in poor health, spends years at the plantation they bought, destitute and in fear of her life from robbers, before her son-in-law, another loyalist officer, rescues her.

A period in Nova Scotia with her husband., discharged from prison and now in a loyalist Highland Emigrant regiment, is succeeded by final years back in Skye. Astonishingly Flora manages to secure a Royal pension from the future Hanoverian King, George IV which, with financial aid from a successful officer son in Sumatra, eases her distress.

Her funeral on Skye, when she dies in 1790 at the age of 68, is attended by thousands and is a sign of the respect which she elicited all her life.

Flora’s story resonates to this day in Scotland and further afield, because she was no keen Jacobite rebel, unlike other Scotswomen, who urged on their clans into battle. She was reluctant to be involved in the 1746 escape plan and have the Prince accompany her, dressed as her ‘Irish maid’, over the Minch to Skye. She rightly feared for her ‘character’ or virginal reputation, all important then for a young woman contemplating future matrimony. She yielded, because, as she told a Hanoverian captor, ‘I would have done the same for you, had you been in distress.’ This remark circulates in the highest circles in London. Her courage in accompanying ‘Betty Burke’, alias Prince Charles Edward, on the stormy midnight voyage is commemorating in the son, ‘Speed, bonny boat, like a bird on the wing/O’er the sea to Skye’.

Flora’s character and strong moral sense attracted too the interest of Dr Johnson and his companion, James Boswell, when they were on their 1773 Highland Tour. Johnson paid a famous tribute to Flora in his account of his travels which is inscribed on her grave in Skye. Boswell later published a lengthy narrative of the Prince’s escape taken from Flora as well as from other 1746 conspirators. As she told the Edinburgh lawyer, however, she had already given a full account of the escape in the later 1740s to an enterprising Jacobite cleric in Leith. This was later to be published, with the accounts of other conspirators, in the late nineteenth century as ‘The Lyon in Mourning’.

Flora’s adherence, with the other members of her family, to the Crown in the American Revolution , when they were living in North Carolina, was a function of their recent arrival in the colonies and also of their earlier experience of the Crown’s power in crushing the 1745 Rising. They could not believe that the ramshackle patriot militia they saw could defeat the British forces. Those Scots who had been in residence in America for decades, knew better the political fire that animated these patriots and were more likely to support the revolutionaries.

What drew you to tell her story?

I grew up between London and Inverness-shire and was named after Flora Macdonald, then very much a local heroine in the latter place. Her statue stands outside Inverness Castle, and as a child I was always interested in her story as the ‘Prince’s Protector’. But I never thought of writing her biography, until I was searching for illustrations for my last book, The Washingtons: George & Martha. And I came across her portrait by Allan Ramsay from the 1740s among a sheaf of images s of American revolutionaries from the 1770s. Then I remembered that in 1773 she effectively told Dr Johnson that he was lucky to catch her as she was off to America.

The process of researching someone’s life and condensing it into the key moments feels a vast task. How do you approach this? What are the most enjoyable or interesting parts of this process for you?

I have always loved doing primary research especially in archives and uniting all the papers from multiple archives in one chronological stream. But I used to dread taking all my research and weaving the salient facts into a narrative. I’ve finally – after forty-odd years of writing historical biography! – learnt to embrace a period of constructive chaos, as I term it. And I swim or go for walks or go and read – fiction unrelated related to the book in question – in a library. Or even go to the cinema alone in the daytime – wicked pleasure! – or do any activity where I’m sure not to have the company or conversation of others. And thoughts arise … And after a time, the arc of the book is clear. And I can start writing. Which I love, even though it can be like being at the coalface sometimes for weeks or even months. I think it helps enormously to know that I have been in every one of these stages of anguish and even torture before. And a book has always emerged.

Though many would likely be most familiar with Flora’s part in Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape, what are some of your favourite lesser-known anecdotes or stories from her life?

My favourite anecdote? When Bonnie Prince Charlie was dressing on the shore on the Long Island as ‘Betty Burke’, Flora’s Irish maid, for the midnight voyage to Skye, he wanted to carry his pistols under his petticoats. Flora refused to allow it.

‘Indeed, Miss,’ the prince replied, ‘if we shall happen to meet with any that will go so narrowly to work in searching as what you mean, they will certainly discover me [his male sex] at any rate.’ For all the jocularity, Flora prevailed, and Charles Edward boarded the boat without the firearm under his skirts.

You’ve written multiple books on women from history; do you find yourself consciously drawn to women in history whose wider stories are perhaps lesser known compared to others’?

I come across the voices – in letters or in diaries etc -of certain women in the eighteenth century and to me they stick up like stalagmites from the ordinary run of eighteenth-century women. This was true of Emma , Lady Hamilton, of George IV’s Queen Caroline, of the six daughters of George III, of Pauline Bonaparte, Prince Borghese, and of Martha Washington. |And I want to worry away at them like a dog a bone until I have their story to share with others. I suppose I am interested in lesser-known women because there are generally excellent biographies already of better-known women. But in all my biographies there have been major male figures in the book too. Nelson; George IV; George III; Napoleon; George Washington. Flora is the first historical character whom I have considered who is without a male counterpart on whom to lean. As you will see in the book neither the Prince not her husband was – what shall we say – reliable?

Are there any people from history you’ve yet to write about who you think have fascinating stories and you’d perhaps like to do a project on some day? What is it about them that interests you?

I have been fascinated by Horatio Nelson since I was a child. He was our greatest ever naval commander and sure of himself at sea from an early age. On shore he was loved as no other officer was by the public, and won a unique place too, in the hearts of many far superior to him in education and rank. His insecurities were understood and calmed by his lover, Emma, and by his family, if not by the wife he mis-treated. So, my next project, on which I am just embarking, for Bloomsbury, my publishers, is Nelson: At Shore and At Sea.

What do you hope readers take from Flora’s story and Pretty Young Rebel?

I do hope readers will enjoy Pretty Young Rebel. I hope they will also come away with the sense, that this was a woman who was admired and respected by all but at the same time was scrambling to negotiate the dangers and vagaries of life on two continents with few resources as best as she could.

Pretty Young Rebel: The Life of Flora Macdonald by Flora Fraser is published by Bloomsbury, priced £25.

Following Irish and Scottish giants Finn McCool and Benandonner, who want to know who is the best giant, but first must cross the Irish sea, we asked author Lari Don to tell Books from Scotland just why folk tales still matter, and what inspiration we take from these variations of tried and tested tales as we venture with them into the Giant’s Causeway.

The Tall Tale of the Giant’s Causeway

By Lari Don, illustrated by Emilie Gill

Published by Floris Books

Folklore is the fertile ground in which my own stories grow. Almost all of the children’s books I’ve written are retellings of traditional tales – folktales, fairy tales, myths, legends – or have been inspired by them.

Why is folklore so inspiring, and are traditional tales still relevant today?

Traditional tales are reliable building blocks for much of our culture, including many forms of storytelling – books, films, computer games – which didn’t exist when these tales were first told. We are fascinated by these old stories because they still give us, as individuals and as communities, something we want and need. Traditional tales continue to be relevant because they’re not static. Folklore evolves, to fit tellers, audiences, circumstances. The stories which last are the stories which are flexible, the ones which can change to fit new worlds.

How do folktales evolve? Here’s an example.

My new book, The Tall Tale of the Giant’s Causeway, retells the story of the Irish giant Finn McCool and the Scottish giant Benandonner arguing across the sea, then building a causeway so they can meet and fight. Their rivalry is resolved without an actual fight because Finn’s wife Oona comes up with a clever trick involving Finn dressed up as a baby. It’s a well-known tale, with dramatic and funny imagery, beautifully brought to life in our book by Emilie Gill’s fantastic illustrations. My retelling aims to balance respect for the original story and consideration for my modern audience. So I tweaked the story a wee bit. This is an Irish folktale with one Scottish character, and it usually ends with the daft Scottish giant running away, leaving the Irish giants victorious. Bearing in mind that the likely audience contains a fair few Scottish picture book fans, I wanted to retell it in a more even-handed way. So I didn’t end the story at the traditional endpoint, I took another couple of steps to allow the Scottish and Irish giants to reach a friendly accommodation over the sea and to give everyone their happy ending.

That’s how folklore evolves. Each teller makes minor changes to fit the audience, the occasion, their own agenda and the changing world around them, so at each telling the story moves on slightly. The story evolves. It’s that ease of evolution which means folklore stays relevant, because those telling it constantly remake it to be relevant. Nowadays tellers and writers can retell stories that are inclusive, diverse and respectful, in a way that might have shocked and challenged the Victorians who wrote down many of the tales we use as building blocks.

Folklore inspires creators in many different ways. It’s always possible to retell old tales in new and interesting forms, either sticking fairly close to the original, like I do in picture books and collections of traditional tales, or in complex reworkings, like the wonderful in-depth retellings of Greek myths by Natalie Haynes and Madeline Miller.

Or you can create entirely new stories by taking characters and elements out of the old tales and putting them in fresh contexts. That’s what I do with my novels, taking kelpies, selkies, centaurs and sphinxes on new adventures in the Scottish landscape. Many fantasy novels are based on characters and magic from traditional tales, from all over the world, like Sophie Anderson’s The House with Chicken Legs and Julie Kagawa’s Shadow of the Fox.

It’s possible to model both these forms of inspiration to young writers. When I visit schools, I aim to free up children to rework stories they’re familiar with, or prompt them to imagine new stories about mythical creatures and magical ideas they’re comfortable with, like unicorns, dragons, golden eggs, enchanted doors. They always come up with wonderful ideas, because making something new with magic that’s already tried and tested in old tales can be a powerful form of creativity.

There are many other areas of life where folklore matters, like tourism, for example. The Giant’s Causeway would be just as geologically spectacular if it wasn’t linked to the Finn McCool folktale, but would it be quite as popular if it was called ‘Mosaic of Basalt Columns’ with no story behind it?

We have lots of folklore tourism in Scotland too. Nessie draws tourists to Loch Ness; the Kelpies statues are named to connect to Scotland’s folktale past; Skye is filled with photogenic ‘fairy’ locations: the fairy flag at Dunvegan, the fairy pools and fairy bridge. A folklore link is probably not enough to draw tourists on its own, but certainly adds an additional layer of magic and interest to a potential tourist attraction.

Folklore is constantly evolving, and I hope that evolution will keep these wonderful flexible stories relevant all the way from ‘once upon a time’ to a far-distant ‘happy ever after’…

The Tall Tale of the Giant’s Causeway: Finn McCool, Benandonner and the road between Ireland and Scotland by Lari Don, illustrated by Emilie Gill, is published by Floris Books, priced £7.99.

In 1720, the young William Nelson leaves Edinburgh to make his fortune in Europe, where his story begins to unfold. To celebrate the release of this entertaining historical tale, author James Buchan tells us a bit more about his newest release, as well as recommending a fair few books along the way.

A Street Shaken by Light

By James Buchan

Published by Mountain Leopard Press

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

I was the youngest of a numerous family, and books often came down to me in more than one piece. Our copy of Stuart Little, by the American author E. B. White, printed in 1945, was missing some pages. Our copy ended with a full-page drawing of a tiny motor-car, driven by a mouse, on an undulating back road in America. I long ago lost the book but retain the mental picture. Years later, in a gallery at the upper end of Madison Avenue in New York, I came on a small drawing by Edward Hopper: a ribbon of road, a couple of circles to show the tops of gasoline pumps, and power lines loping away into infinity; and had the same feeling of immensity.

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest book A Street Shaken by Light. What did you want to explore in writing this book?

I had written a biography of the Scottish adventurer, John Law of Lauriston, who in the eighteenth century was briefly finance minister of France. It was published in 2018. I had spent five year following Law’s traces in Europe and North America and, what with lockdowns and all, found it hard to surface from the eighteenth century into the twenty-first. I thought I might cast up my impressions of Law’s age into a novel, and then a suite of novels, which would have more battles and ship-wrecks than are generally found in a realistic work of fiction set in present times.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

The visit of Joe Gargery to Pip in Chapter XXVII of Great Expectations stopped my twenty-year-old self in his tracks. If Pip had become obnoxious, he was nothing to what I had become. I suppose Dickens was also thinking of himself.

The book as . . . an object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

Nothing prepared me for the sight, in a glass case in the library of a millionaire’s country-house, of James Audubon’s Birds of America, engraved on double-elephant paper in Edinburgh and London in the 1820s and 1830s. The memory is tinged with regret for the birds shot or stabbed for the drawings and for the extinct races.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

My parents lived apart. One summer holidays, at the age of about thirteen or fourteen, having exhausted Alistair McLean, Ian Fleming and Hammond Innes, I asked my mother to suggest something different. She took from a set in her book-case, Decline and Fall by Evelyn Waugh. I read that, and then Scoop and then Vile Bodies, and so on to to her least favourite, Put Out More Flags. My father was much in Paris. On a visit to him, the same year or the next, he suggested I read a pet novel of his, Le grand Meaulnes, by Alain-Fournier, who was killed in the First World War. I did so, with difficulty, but French was never so hard again.

The book as . . . rebellion. What is your favourite book that felt like it revealed a secret truth to you?

I dreamed one night that I was reading the quatrains of Attar and found the secret of existence in four short lines. I stumbled downstairs, took down Attar’s Mokhtarnameh and read Persian quatrains till my eyes ached and light was coming in through the window. I did not find the secret of existence.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

Like all my schoolfriends, I read Basho’s A Narrow Road to the Deep North when it was translated in the Penguin Classics. Recently, my son lent my a translation of the poems of Saigyo, Basho’s model and predecessor. I would like to walk the roads of old Japan, composing dreadful verses.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

Buchanan’s Travels in the Western Hebrides, printed in 1793, a most generous present from my brother. I feel I should wear white gloves to hold it, like a snooker referee.

A Street Shaken by Light by James Buchan is published by Mountain Leopard Press, priced £16.99.

Kevin P. Gilday’s new collection explores the fragmented nature of our modern lives, alongside the need for real connection in an era of rampant individuality. You can treat yourself to an exclusive look at some of his new poems below.

Anxiety Music

By Kevin P. Gilday

Published by Verve Poetry Press

Anxiety Music

Wherever I go

I hear it

The anxiety music

The unfinished symphony

The merciless drone

The atonal attack

The incessant pop chorus

The anxiety music

My neurological dials, tilted

Tuned in

To the rhythm of a raised heartbeat

A weary waltz of what-ifs

Can you hear it?

It’s there in the supermarket queue

Rehearsing your only line

Like a third-rate actor

Translating a bus ticket

To inky pulp

It’s there in the pre-flight announcement

Tracing the pilot’s voice for a hint of doubt

A polygraph of panic

Angered by your blatant disregard

For the wonders of gravity

Lately, the anxiety music has grown louder

Heralded by fascistic trumpets

Amplified by the unrelenting buzz of the internet

I hear it in the dark cubicle of my subconscious

Composing a lopsided poem to ego

A 4am, 130BPM

Techno trauma, jangling

My nervous sound system

On a Sunday evening

Just as the sun sets

The anxiety music seems to seep

From every wall

And I am a child again

It’s the ice level from Mario Brothers 3

And my dad singing Deacon Blue

And an ashtray of fags

Burning themselves out of existence

The anxiety music sometimes sounds

Like a symphony of misfiring bus engines

Backed by a choir

Of well-meaning

Constructive criticism

The brass phasing an apocalyptic scale

Scoring a thousand painful deaths

All the ways the music will end

And when it does

When the record scratches and skips

Will we wonder if we conceived all that disquiet

As a smokescreen to mask our failure

Against all that perceived danger

Robbing us of our chance to live fully

To enjoy our footloose three chords

And marvel at our glorious middle eight

Before everything we know

Turns to static

Will there at least be time for a retrospective?

I need the world to exist

Just long enough

To declare me, a genius

Revisit those overlooked masterpieces

Pamper me with posthumous validation

A serious re-evaluation

I need a scholar to find the thematic link

Between my second collection

And my fourth album

Provide what I was never afforded in life

I want:

Goths to scratch my lines into notebooks

Teenagers to fuck on my gravestone