A tale of two times. It’s 2019 – Hannah Greenshields has her first day at Memory Lane, a memory clinic in Edinburgh’s centre, which houses advanced technology which allows clients to relive their favourite memories for a substantial fee. Fly back to 1975 and John Valentine, another client, is reliving his wedding day over and over, hoping to change one key event he can’t forget. John soon realises his memory isn’t such a safe place after all. The pair must work together to get John back to the real world before it’s too late.

Ross Sayers had a quick chat with Books From Scotland to celebrate his latest release.

The Everliving Memory of John Valentine

By Ross Sayers

Published by Fledgling Press

Another publication day for you – congratulations! Could you tell us about your latest book The Everliving Memory of John Valentine?

Thank you so much! Of course, the book is about a mysterious memory facility in the middle of Edinburgh, Memory Lane, which allows wealthy clients to pay to relive 12 hour segments from their memory. The narrative is mainly split between Hannah, who is a new employee of Memory Lane, and John, who is reliving his wedding day over and over again. Hannah discovers that clients can’t be automatically removed from their memories when the 12 hour period is up, and it’s her job to go into client’s memories if they refuse to leave after their allotted time. I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler to say that Hannah ends up going into John’s memory at some point…

You’re a bit of a writing machine! This is your second book in the space of a year, and a year, let’s face it, that has been quite challenging. How have you stayed motivated to write?

I definitely think I had a bit more motivation at the start of lockdown, when the novelty of being at home all the time hadn’t worn off. I had the idea for the book a couple of months in and was fortunate enough to have the time to get going with it. As more and more opens up, I’m finding it harder to sit down at the laptop!

You’re normally better known for writing Young Adult fiction, what made you decide to write your first novel for adults?

I think I just wanted to try something different. YA is great but you’re a little restricted in that your main characters have to be quite young, whereas I knew for this story I needed one of the main characters to be an older gent. Personally I don’t think there’s a huge difference in the writing/ tone etc, and certainly there’s just as much swearing in my YA books as in this one! I’m aware that even the phrase ‘YA’ will put certain readers off, so I wonder if I’ll get anyone reading this book that wouldn’t have read my previous ones.

Both your latest novels feature time travel, though The Everliving Memory of John Valentine is more internal time travel than physical time travel, which brings its own problems! What did you want to explore in writing this novel?

So I wanted to explore this technology, the tech that allows the clients to relive their memories. I wanted to explore the limits of it, eg what you can and can’t do within memories. For the character of John, he’s trying to change something in his memory, trying to do something differently, and is finding that, well, it’s a struggle. But also, it’s not impossible? Just as memories in your head can change over time, the technology begins to change. I also wanted to explore the relationship between John and his dad, and fathers and sons as a whole. And then with Hannah’s storyline, that’s more about the relationship young people have with both their workplaces and workmates. I’ve found that no matter the workplace, there are always the same kind of dynamics. So it doesn’t matter that this Memory Lane place is hugely wealthy clinic with incredible technology…the vending machine in the canteen still doesn’t work properly.

Do you enjoy reading sci-fi or speculative fiction yourself? Which writers, books and films have influenced your work here?

I loved Red Dwarf growing up (both the show and the books: Infinity Welcomes Careful Drivers and Better Than Life), and then the Back to the Future films are some of my favourites. The Discworld books too. And then more recently, I really loved Trackman by Catriona Child, which did that great thing that the best speculative fiction does, of introducing an unreal concept (an MP3 player which independently plays the perfect song at the perfect moment) into the real world.

Are there any favourite memories of yours that you would like to visit again, that you can share?

When I was in my early twenties, I got really lucky that I was able to visit some really cool places (Rio, Tokyo, San Diego), but I only got a day or two in each. I think I was too young to properly appreciate these trips to be honest, I wouldn’t mind doing them again. Wouldn’t mind spending longer than 48 in each place as well mind you …

Your novels always have great humour in them. Do you have any tricks or tips for writers who would like to write comedy?

Thank you! I think taking notes is a good thing to do, and it’s a lot easier these days when you can note it down on your phone rather than having to be that weirdo who’s scribbling on a notepad at the football. But yeah, if you hear someone say something funny, just take a note of it and then when you’re writing, and you think, this character would make a funny comment here, you can look through your notes and see if you can slide anything in. Just steal from others, basically.

Do you know what you’ll be working on next, or are you ready for a rest now?

I’m working on a new YA book but I’m keeping all details under wraps for now. I think I am anyway. I find I forget what I’ve said publicly. But as far as I know, I haven’t said anything about it!

What’s been your favourite books of the year so far?

Ok the main ones which spring to mind: Happiness Is Wasted On Me by Kirkland Ciccone, Luckenbooth by Jenni Fagan, and Duck Feet by Ely Percy. Can’t go wrong with those three.

The Everliving Memory of John Valentine by Ross Sayers is published by Fledgling Press, priced £9.99.

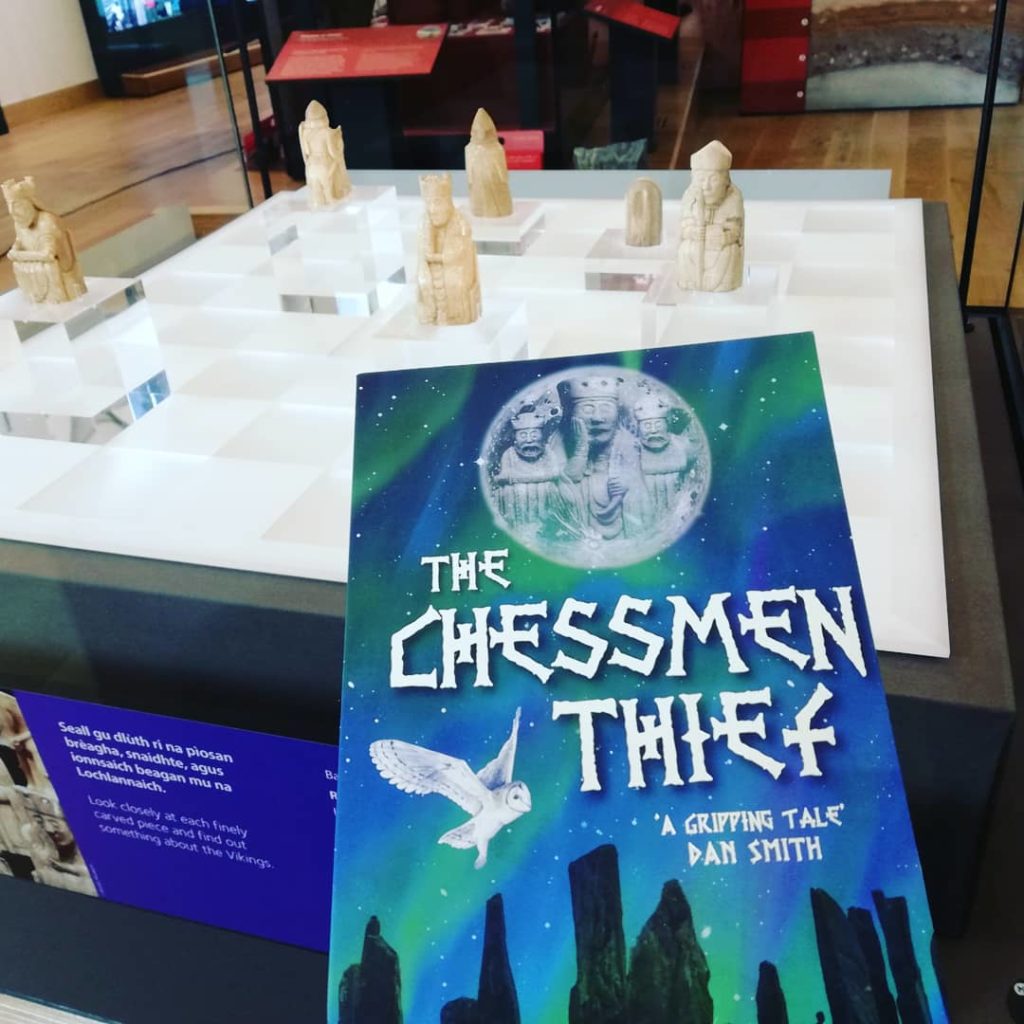

Author Barbara Henderson’s new novel for children, The Chessmen Thief, takes its inspiration from the beautiful and mysterious Lewis Chessmen. Here, she tells BooksfromScotland the full story behind her latest creation.

The Chessmen Thief

By Barbara Henderson

Published by Cranachan Publishing

Inspiration across the board

Can you play chess?

I suspect many of us know some moves or can hold our own on the chequered board, up to a point.

After the success of The Queen’s Gambit on Netflix, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the game of chess is ‘of the moment’, hip and cool. Many people, including myself, are therefore surprised to discover that the game of chess was popular in Norse-held Scotland almost a thousand years ago. Vikings were not only warriors, pillagers, slavers, adventurers, looters and explorers – no, these Norsemen were the original gamers – and skilful crafters too!

I vividly remember the first time I came face to face with the Lewis Chessmen, iconic relics of our Viking past. Dated to the second half of the 12th century and carved of walrus ivory, they were discovered on a remote beach in the Uig region on the Isle of Lewis. Now they can be seen by museum visitors in the National Museum of Scotland, in the British Museum in London and, fittingly, in the Museum nan Eilean in Stornoway. Dad would have loved these figures, I remember thinking. My father was a competitive chess player.

I had seen the Chessmen in London and Edinburgh, but the impact of visiting the figures on the Isle of Lewis was particularly profound. The exhibition room is airy and bright, the display is transparent on all sides and roughly at the level that a gaming table. For the first time, these figures struck me powerfully as objects, to be made, carved, polished, purchased and played with. Instead of artefacts of abstract significance, they felt real, despite the mysteries surrounding them. Who had crafted them, and why? Who did they belong to? Who placed them where they were found? What could have made that person part with such priceless treasure? Some research was in order, because the story sprites of my imagination were off, and I needed to keep up.

I find it helpful to read around a subject for a while, until some quirky detail or other jumps out at me. I don’t overthink it: if it is interesting enough to lodge itself in my brain, chances are it will be interesting enough to hold the attention of a young reader too. The figures are most likely to have been produced in Trondheim in Norway. A perilous sea journey to the Hebrides beckoned for my book, probably with a stopover in the Northern Isles.

Of course, I needed a young protagonist – easy! Many youngsters were abducted from Scotland and Ireland in Viking raids. And with that came the central motivation too: my young hero Kylan would hail from the Isle of Lewis and long to return. Alongside this, he dreams of freedom: to be more than a pawn in someone else’s game. The handy chess phrases were springing to mind alongside the plotting. My story was beginning to come together!

I was particularly fascinated by the carving process behind the Lewis Chessmen. The idea of shining a light on Norse culture – skilled craftsmanship, sophisticated strategy games and storytelling – really appealed to me. It would be a fresh new angle on the Norsemen, a society where prayers and pillaging went hand in hand. I was hooked, and the writing began in earnest. In the early stages of the manuscript, and just before Covid came along, I managed to get across to Orkney to research the lie of the land and to learn more about the famous 12th century Orkneyinga Saga which was to provide many of the adult characters in the book, including my most terrifying villain.

In the weeks that followed, The Chessmen Thief became much, much more than a story or a conventional work-in-progress. Writing this book was my lockdown routine, my coping mechanism, my escape when I couldn’t go anywhere – and yes, a tribute to my much-missed father.

My hope is that this Viking adventure will provide the same escape, the same flight of the imagination, for youngsters around the country – and perhaps recruit a handful of new chess players too.

My father would have approved.

The Chessmen Thief by Barbara Henderson is published by Cranachan Publishing, priced £7.99

We love the picture books Floris Books publish, and their latest, Home of Wild by Louise Greig is just as beautiful as the rest. We caught up with her to ask her more about her gorgeous book.

Home of the Wild

By Louise Greig, illustrated by Júlia Moscardó

Published by Floris Books

Where did the story of this book begin for you? Where did the idea come from?

I have three great loves; nature, animals and the beauty of Scotland. I think this book has lived inside me all my life. The fawn is probably a metaphor for everything I feel about animals; their need for our understanding and protection whether they are wild or tame. It all seemed to bubble up to the surface and once I had the first line it took wings.

Were there any special places that inspired the story?

Some years ago we had a cottage in Strathdon and my neighbours in a remote glen rescued an orphan fawn. They called him Scooter and although he ultimately lived out in the glen he used to come in now and again and lie by the kitchen range with their family dogs. I cannot say Home of the Wild is based on this but it is an enchanting memory I have and may have influenced the story on some level.

The book feels like a real celebration of the natural world. Is it important to you to feel connected to nature?

A deep connection to nature is at the absolute centre of my life. I could not function without it. There are places that mean so much to me where the rivers, the woods and the fields have become my friends. It is a fundamental need in my life. I am eternally grateful for the endless nourishment, comfort and inspiration nature has given me.

How important do you think it is for children to have access to nature?

I think it’s crucial for today’s children to connect with nature when so much of their lives today are screen based and screen stimulated and their freedoms are restricted. As humans we are of nature, our ancestors were hunter gatherers living to the pulse of nature. The seasons defined what we ate and when we slept. There is a song of nature deep within all of us. Thank goodness for the wonderful initiatives that exist to get children connecting with nature.

Do you have a favourite Scottish spot you’re looking forward to visiting post-lockdown?

I would love to visit the Outer Hebrides some day and see the wild Eriskay ponies.

I am also one for a bit of a pilgrimage so I would love to visit Sandaig Bay where Gavin Maxwell , the writer, lived with his otters. Ring of Brightwater is one of my favourite nature books.

Have you ever had an animal companion you’ve connected in the way that the wee boy and Alba the deer connect in the story?

I have had many animal companions in my life and all of them have touched me greatly, but the one that stands out was my rescue Greyhound, Smoky. I had him from 2007 to 2018 and from the first day we were inseparable friends. He was with me all the time. He had lived a rough life and was picked up stray in terrible condition before he came to me. The connection I had with him was profoundly special.

How did it feel to see the story realised visually with Julia’s illustrations for the first time?

It was incredible. I had been shown samples of Julia’s work which were beautiful but nothing could have prepared me for the finished artwork. She has captured the wild and wistful beauty of the Scottish landscape perfectly but most of all she has absolutely nailed the relationship between the boy and Alba. I am captivated, utterly, by what Julia has done.

Do you have a favourite illustrated spread from the book?

I am one for small telling details and there is a spread of the boy’s bedroom which is full of glorious clues which give the reader a real insight into the little boy’s interior world. He is a child of nature and the details are gorgeous. But the spread that carries the most emotional resonance for me is the very last one where there is now a deep understanding between the boy and Alba. Alba belongs to the wild but they are always together in spirit. The wind is blowing and will carry their bond forever. It actually brings a tear to my eye every time I look at it. That is the power of Julia’s work.

https://youtu.be/5R3wa1qiqzw

Home of the Wild by Louise Greig, illustrated by Júlia Moscardó is published by Floris Books, priced £12.99.

This is a book about abandoned places: ghost towns and exclusion zones, no man’s lands and fortress islands – and what happens when nature is allowed to reclaim its place.

This book explores the extraordinary places where humans no longer live – or survive in tiny, precarious numbers – to give us a possible glimpse of what happens when mankind’s impact on nature is forced to stop. From Tanzanian mountains to the volcanic Caribbean, the forbidden areas of France to the mining regions of Scotland, Flyn brings together some of the most desolate, eerie, ravaged and polluted areas in the world – and shows how, against all odds, they offer our best opportunities for environmental recovery. This extract is about nature reclaiming what was thought to be ruined land – the shale bings of West Lothian.

Extract taken from Islands of Abandonment

By Cal Flynn

Published by William Collins

Fifteen miles south west of Edinburgh, a knuckled red fist rises from a soft green landscape: five peaks of rose-gold gravel stand bound together by grass and moss, like a Martian mountain range or earthworks on the grandest of scales. They are spoil heaps..

Each peak rises along a sharp ridge from the same point on the ground, fanning outwards, in geometric simplicity. Along these ridges, tracks once bore carriages aloft, bearing tons of steaming, shattered rock: discards from the early days of the modern oil industry.

For around six decades from the 1860s, Scotland was the world’s leading oil producer, thanks to an innovative new method of distillation which transformed oil shale into fuel. These strange peaks stand in monument to those years, when 120 works belched and roared, wrestling 600,000 barrels of oil a year from the ground in what had been, shortly before, a sleepy, agricultural region. The process was costly and effortful, however. To extract the oil, the shale had to be shattered and superheated. And it produced huge quantities of waste: for every ten barrels of oil, 7 tons of spent shale would be produced. In all, more than a hundred million tons of the stuff – and it had to go somewhere. Hence these enormous slag heaps. Twenty-seven of them in all, of which nineteen survive.

But to call them slag heaps is to understate their size, their stature, their constant presence in the landscape; unnatural both in form and scale. Locally, they are called ‘bings’ – from the Gaelic, binnean, a high and conical hill.

This particular formation, the five-pronged pyramid, is known as the Five Sisters. Each of the sisters slopes gradually to its highest point, then falls steeply away. They rise from a flat and otherwise rather unremarkable landscape – muddy fields, pylons, hay bales, cattle – to become the most significant landmarks of the region: some pyramidal or square; some organic and lumpen; others still rising raw-flanked and red to plateaus like Uluru.

Mere tips at first, they grew into heaps that shifted and reformed like dunes. Then hillocks. Then, finally, mountains made from small chips of stone – each the size of a fingernail or a coin, with the brittle texture of broken terracotta. These mountains grew and spread, as barrow after barrow was dumped upon the heap. They rose from the land like loaves, swallowing all they came into contact with: thatched cottages, farmyards, trees. Under the northernmost arm of the Five Sisters an entire Victorian country house – stone-built and grand, with wide bay windows and a central cupola – lies entombed beneath the shale. Oil production continued on a massive scale here until the Middle East’s vast reserves of liquid oil came into ascendancy. In Scotland, the last shale mine closed in 1962, bringing to an end a local culture and way of life, leaving mining villages without the mines to employ them, and only the massive, brick-red bings as souvenirs. For a long time the bings were disliked: barren wastes that dominated the skyline, fit only to remind the region’s inhabitants of an industry gone bust and an environment pillaged. No one wants to be defined by their spoil heaps.

But what to do about them? That wasn’t clear.

A few were levelled. A few later quarried afresh, as the red stone flakes – ‘blaes’ as they are technically known –found a second life as a construction material. For a time blaes turned up everywhere: fashioned into pinkish building blocks, used as motorway infill, and – for a time –surfacing every all-weather pitch in Scotland, including the one at my high school. Blaes stuck in grazed knees, collected in our gym shoes, left a tell-tale dust across the jumpers used as goal posts – and generally formed the brick-red backdrop to our communal coming of age. But mainly the bings lay abandoned and ignored. After a while, the villages in their shadows grew used to their silent presence. To enjoy them, even.

It’s easy to find the bings. You can see them from miles off. Just drive until you can’t get any closer, and hop the fence. There’s no fanfare. They are spoil heaps the size of cathedrals or hangars or office blocks, rising from the fields in artificial formations.

* * *

My aunt and uncle live in West Lothian, not far from the Five Sisters and even closer to their even larger cousin at Greendykes. Last time we went to visit my relatives, my partner and I took a detour to climb the sleeping giant. The light was flat and silver, the sky grey and cottoned over with cloud. We parked in a semi-derelict industrial estate, between rust-streaked Nissen huts and faded signposts, and wandered out into a landscape of almost unbelievable strangeness, like the first colonists on a new planet. Sculpted by wind and rain, there were outcrops and boulders comprised of a conglomerate of compressed blaes, a rock form all its own, in Martian red and violet-grey where the outer blaes had chipped away to reveal fresher stones – with that smooth, almost greasy look of chipped flint, olive-tinged – not yet discoloured by oxidation.

Deep ponds of bottle green had gathered in hollows at the base of the slope, at the foot of each dell and gully formed by the tip’s puckered edges, their outlines picked out in the acid green of the pond weed and hair-thin grasses that intermingled in the shallows. Water lilies poked their noses through the surface, where tiny insects skated by. Whip-thin birches sprung with unlikely fervour from their gravel beds, silk-skinned and shining and bearing tiny buds of sweet new leaves. We pressed between the birches, along a narrow footpath, to emerge at the base of the bing proper, and found its vast red flanks rising ahead of us, contours and crannies picked out dramatically in vegetation, and striated with tracks.

We began to climb, but the going was difficult. The blaes had solidified into a dense conglomerate to form rock faces in places, in others scree. Elsewhere, the outer- most layer was grassed over but crumpled, like laundry, where the skin had slipped down, and when we put our weight on it we post-holed as if through rotten snow. Grit collected in our shoes. We had to stop to empty them out, and I felt a flush of something like nostalgia.

After a fashion, we reached the top – a wind-battered upland that offered panoramic views across clean-swept fields to Niddry Castle, a sixteenth-century tower, behind which yet another bing – a sheer cliff of spent blaes, ruddy-faced but streaked with green and grey – stood breathing down its neck. And beyond, yet more, rising proud from the flats.

The flora here was a strange mix; it was hard to get a fix on the sort of climate we found ourselves in. Russet shoots of willowherb were coming up across the tops, as it might along any roadside in the country. But other than that, the vegetation had a sparse, sub-arctic feel: a close crop of soft-furred leaves and starred flowers and short, blonde grass. But there was red clover too, with their sweet heads full of nectar just beginning to open, and spotted orchids. The year’s first bumblebees blundered by, revving their engines. Buds and shoots were snaking up, out of the gravel. The land basking, warming, ready to bloom. It was the end of April. Impossible not to think of T. S. Eliot:

breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

Back in 2004, the ecologist Barbra Harvie made a survey of the bings’ flora and fauna and found to almost everyone’s surprise that, while no one had been looking, they had transformed into unlikely hotspots for wildlife. ‘Island refugia’ she termed them: little islands of wildness in a landscape dominated by agriculture and urban development. Hares and badgers, red grouse, skylarks, ringlet butterflies and elephant hawkmoths, ten-spotted ladybirds. Among the flora were a diverse array of orchids – the endangered Young’s helleborine, a delicate, many-headed flower in pale greens and pinks, found in only ten locations in Britain (all post-industrial, two of them bings); the early purple orchid in ragged mauve; the greater butterfly orchid, with its winged petals – and a genetically distinct birch woodland that had established naturally at the base of the tiny bing at Mid Breich.

Overall, Harvie recorded more than 350 plant species on the bings – more than can be found on Ben Nevis – including eight nationally rare species of moss and lichen, among them the exquisite brown shield-moss, whose thin tendrils loft targes to the sky like an army in miniature. Over the space of a half-century, these once-bare wastelands had somehow, magically, shivered into life.

Eliot’s wastelanders – or some of them – transpire to be his contemporaries: modern commuters flooding across London Bridge at dawn, lonely typists whiling away evenings in bedsits. In a sense, we are all residents of the Waste Land still – and I felt it keenly then, standing at the prow of this great memorial to ecological degradation.

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish?

Eliot’s Waste Land drew from the ‘perilous forest’ of Celtic mythology, a land ‘barren beyond description’ through which a hero must pass to find the Otherworld, or the holy grail. The bings, too, already offer a glimpse of what we might find on the other side: recuperation, reclamation. A self-willed ecosystem is in the process of building new life, of pulling itself bodily from the wreckage. In starting again from scratch, and creating something beautiful.

Blasted to 700ºC before they were dumped, still roasting, on the tip, the blaes would initially have formed a vast sterile desert devoid of seeds or spores. The regrowth we see now, then, began from absolute zero – no soil, no nothing – as part of a process known as ‘primary succession’.

First came the pioneers: lacy foliose lichens, curling at the edges and growing in coral-like reefs; Stereocaulon, the snow lichens, forming up in crusts. Green mosses laid over the gravel like a picnic blanket, soft and welcoming. Then, the ruderal plants – from the Latin, rudera: of the rubble – the wildflowers and deep-rooted grasses that colonised the loose chutes of scree, stabilising them like marram grass on sand dunes. Kidney vetch and toadflax, bluebells and plantain, yellow rattle, pearlwort, speedwell, sweet clovers. In the damp clefts, seeds of the hawthorn and the rosehip and the birch caught purchase, took root.

All these materialised as if by magic: blown in on the winds, or spread by birds, or dropped in the droppings of animals (what ecologists call, poetically, ‘seed rain’). They are the few survivors of a much greater experimental programme, the hardy few who found a toehold in the spoil heaps and made it work for them. The more there are, the easier it becomes for others, as organic matter builds up as leaf mould and deadwood and algae, and acts as a compost for the next generation. To begin with, the bings would have been species poor, and then a fluctuating assemblage of species would have played across their faces as each tried out new forms of what they might become. Montane species, common weeds, escaped ornamentals. But over time, species accrue, bed down. And now, the bings come to act almost as an archive of biodiversity for the local area.

And though the bings are a remarkable example of the process in action, they are not unprecedented. In nature, primary succession takes places only rarely – on newly formed dunes, or volcanic islands bubbling into the open from underwater vents. But humans have a bad habit of stripping the land bare of all its life, and starting the process all over again.

In the wake of the London Blitz, the then-director of Kew Gardens noted a similar process taking place in the charred and ruinous bombsites that pitted the capital. In a 1943 pamphlet, ‘The Flora of Bombed Areas’, E. J. Salisbury described ‘the rapid clothing of the blackened scars of war by the green mantle of vegetation’. These plants grew up spontaneously, he noted, upon the bare rubble and in the ruins of the houses. The ‘dust-like spores’ of mosses, ferns and fungi drifted in through the broken windows; the soft, silken seeds of the willowherb para- chuted in from site to site (each young plant, he added, might produce 80,000 seeds a season). So too did the pennant-yellow flags of ragwort and groundsel and colts- foot, and the wispy, wand-like fleabane, and the sow-thistle and the dandelion, and the tiny, star-flowered chickweed. All the time, these seeds and spores – the potential for wildflowers, of wild life – is drifting by us on the air, waiting for their chance. As a petri dish left out will soon grow cultures of its own, a sterilised bombsite or lava flow or bing will do the same, but on a grander scale. All they need is a place to land.

Islands of Abandonment by Cal Flynn is published by William Collins, priced £16.99.

Jim Crumley’s Nature quartet of books are some of the finest nature books in print. Here we celebrate the seasons of Spring and Summer. Firstly with St Kilda in the summer, then with a recollection of birds in spring.

Extracts taken from The Nature of Summer and The Nature of Spring

By Jim Crumley

Published by Saraband

St Kilda Summer 1988

Behind Boreray

It is black behind Boreray and small. All suns dance darkly here,

throw no shadows on rock this black.

Stac Lee is a black berg

its sunk seven-eighths beyond the scope of suns and me.

We who sail our puny daring under Stac an Armin

creep tinily by.

It all started in the early summer of 1988. I handed in my notice at the Edinburgh Evening News, where I had been working for eight years on the features desk, and at the invitation of publisher and landscape photographer Colin Baxter, I went to St Kilda, forty miles west of the Outer Hebrides, to write what would become my first book. Ian Nimmo, the editor of the Evening News at that time, and who had done much to encourage me to flex my writing muscles in his newspaper, gave me his blessing with the words “you must follow your star”. So began an adventure that changed my life utterly. I had been a journalist from the age of sixteen. At the age of forty, I became a full-time nature writer literally overnight (and halved my income at a stroke). It was a fast transition: the book was published three months later, on the day after I left the paper. The only copy of it I still possess is the one I gave to my mother, and which I had inscribed:

For Mum with much love from the author!

Jim

October 1988

She had been very critical of my decision to leave the Evening News (she was not the only one among my family and friends and ex-colleagues). But seeing that book and holding it in her hands and reading the inscription…all that changed everything: her opinion of the enterprise swung through 180 degrees from a headwind to a tailwind, and for the last five years of her life until her death in 1993, she became the champion of my cause.

My first book? I can no longer remember how it felt. Probably I walked on air for a few days, then I looked around, thought, “What’s next?” and started writing my second book. I thought that was how it was supposed to happen, and as no one has advised me differently, I have just kept on doing it ever since: forty books in thirty-two years. Still following my star, Ian. And thanks.

This book concludes a tetralogy of the seasons, and that life-redefining summer of 1988 seemed like a natural place to begin, the first of all my nature-writing summers, for all that it had been temporarily thwarted at the very first hurdle. On the day I was supposed to travel to Oban to join Colin Baxter for the sail to St Kilda aboard a two-masted schooner, I was floored by a violent gastric bug. So I went alone three weeks later by the rather less glamorous route of a flight to Benbecula, in the Outer Hebrides, and then the Army’s flat-bottomed landing-craft (the Army maintained a small base there at the time to service a cliff-top radar station). As one seasoned St Kilda veteran had counselled me: “She wallows like a drunken pig, that bitch.”

As it happened, she declined to wallow. The evening ocean was as benign as the Crinan Canal. HMS The Drunken Pig was sober and demure. I stared at the ocean, at its raft of islands astern and its absence of islands ahead. I slept. Then a voice gate-crashed a dream: “Anybody want to see St Kilda? It’s worth a look.”

Oh, yes please. I wanted to see St Kilda very much indeed, for was it not to be the passport to the rest of my life? My watch said 5a.m. I went up on deck and the Atlantic was barely astir and the sky was pink and St Kilda was purple. And the voice was right: it was worth a look.

It is that first look that I remember, the one utterly indelible souvenir that has survived those thirty-two intervening years intact. It was a cardboard cut-out, as two-dimensional as a stage set, and it floated upright among leisurely waves. And it was purple. Or rather it was purples. The nearest island, a dour little tea-cosy-shaped rock lump called Levenish, was the darkest purple. My particular sightline set it against the much larger island of Boreray, and Boreray not only stood more than 1,200 feet straight up out of the ocean, it was the silhouette of a sea monster, and it was paler purple, borderline lilac. Over the next two weeks of camping alone, I would see Borerary from many angles in many weathers and every hour of the day and the dusk and dawn, and including the view through a gauze of gannets from the un-horizontal deck of a yacht at very close quarters indeed; but not once did that extravagant portfolio I would amass ever threaten to dislodge from my mind’s eye that first of all my St Kildas on that first morning of all my nature-writing summers.

And Stac Lee was there too, a mere 600 feet high, but quite high enough for a lopsided parallelogram with no visible means of support, and that too was the paler shade of Boreray purple.

Then the boat dipped and I realised that parts of the superstructure were concealing parts of St Kilda, so I ran to the bow where wider oceanic miles lay unobscured. And there was Hirta, the main island, and there was the untidy sprawl of Dùn, Village Bay’s eccentric, wafer-thin breakwater, looking like a bar of Toblerone that had gone horribly wrong in the baking.

These set pieces of the St Kilda archipelago, so familiar to me (in outline, at least) from a few books, from other people’s photographs, from maps and film and drawings and paintings and word-of-mouth (it is astounding how many St Kilda veterans emerged like woodlice from under stones once the word of what I was doing leaked out) now made smithereens of my every preconception. While I stared and tried to respond in what I thought might be a suitably nature-writerly way to where I was and what I was seeing and what-the-hell-did-I-think-I-was-doing, by the way, something utterly new stole over me in the face of so much incomprehensible, volcanically tarnished age, and it was this: Though I turned very slowly through 360 degrees, I could not see any other land, in any direction, none at all. And these first moments became my all-purpose visual definition of St Kilda, the one I have carried in my mind ever since. And so primitive was the encounter, so elementally simple – one sea, one sky, one scatter of improbable rocks – that I might have been the first of all St Kilda voyagers, one of a tribe of nomadic herdsmen coming curiously up the margins of Europe, exchanging bemused glances and agreeing among themselves that surely here was nature’s last limit. For they would be accustomed to sailing where land was in sight, and on St Kilda, the only land very occasionally in sight (I would have one glimpse of a white-sanded Hebridean beach – Harris – in two weeks) is the land that you left forty miles behind to get here.

Time filters out the scents, the sounds, the touch and the taste of St Kilda on the air, and leaves only the sights (or the memory of some of them, at least), for every one of my fourteen days there was crammed with them. The freedom I was permitted to wander at will and alone meant that I crowded the days and some of the nights with everything all the time, occasionally retreating to my tent and my small portable typewriter to spill out the chaos of St Kilda into the manuscript of my first book. There was no time between the two, and no distance. And now, so much time has intervened, and so much distance; although I have returned often in my mind I have never returned in person. When I consider those first days of that first nature-writing summer (what a place and what astounding good fortune in which to begin), how could I ever improve on all that or add to or embellish it by going back? The simple passage of time, aided by memory’s tendency to edit selectively so that only the essential remnants stand forward in any kind of clarity from such a head-on collision with natural forces: all that has distilled down to a single time and place, the indispensable pure gold that sustains one traveller’s idea of that time, that place, my own personal St Kilda.

From The Nature of Spring:

Then, from the shore at Port Ramsay, just as sun-light began to enliven the visible world, a familiar shape emerged from a cursory scan of a wood across the water, an erect grey-brown slab that looked too big and too heavy for the comfort of the tree where it appeared to have been hung, like a sheet left out to dry. More careful consideration revealed that it was not hung but perched. Then it raised its head from its breast where it had been rearranging its feathers with an implement that looked like a cross between a sickle and a banana, and instantly became a sea eagle. And there it stood and there it stared and there it settled into prolonged stillness, looking as if it might spend the entire afternoon in that attitude. It was a telling example of one of the bird’s character traits that distinguishes it from the golden eagle: it has no fear of humankind and its works, humankind’s settlements and humankind’s noise. This one was in full view of Port Ramsay’s street of houses in the middle of the afternoon while the residents went about their business. The nearest house to the tree where the bird perched was about 200 yards. A collie barked. Two people worked on a boat. Three more chatted in a garden between house and shore, their voices carrying far over the quiet water. Two cars appeared from opposite directions at the one road junction, stopped there while the drivers conversed through open windows, engines running. The sea eagle feigned disinterest, but it is a safe bet that it took in everything.

Not one of the people I could see appeared to know that it was there; either that or its appearance in that tree was so familiar that it had become part of the furniture.

I mulled over the bird’s changing fortunes. One hundred years ago, almost to the day, the last of its kind in Scotland, in all Britain, was shot, and it was not as if no one knew that it was the last of its kind. Its extinction had been achieved deliberately. Now this, where a small island community appeared to be quite indifferent to the presence of one of the most astonishing birds in the northern hemisphere, casually perched on its doorstep. Mull across the water has even turned it into a tourist symbol.

A flashback barged into my mind. Twenty years before, I was in a small open boat motoring out from Hoonah, Alaska, a one-horse town in the Tongass National Forest. These were strange, eerie waters, lagoonishly glassy, lap-ping almost silently against shores of rock and mud, above which spruce and hemlock forest reached improbably far up mountains with no names, and extended for miles and miles. It takes the sudden appearance of a humpback whale a hundred yards off the port bow to inform a dislocated stranger that these waters are outposts of the Pacific Ocean too. As that dark-green shore glided past, tree by giant tree, we kept passing the erect, blond-headed totems of that country that are nesting bald eagles; they were as regular as milestones. My host, a part-Tlingit hunter and fishing guide called Floyd Petersen, cut the engine for a while so that we could talk more comfortably, with just the quiet accompaniment of the idling ocean. Suddenly a shrill, giddy voice poured a stream of molten silver down out of the trees, so that it bounced up at me off the water and hit me squarely between the eyes.

‘What the…?!’

‘Oh, that’s the eagle.’

Oh, that’s the eagle.

I found him with the binoculars, just as he was poised to let fly again. He threw his head back, opened his throat to the sky, and out poured the silver-tongued deluge again, and up it bounced again, and a chill rippled across my shoul-der blades. I thought of the opening bars of a concerto for wilderness. That image of an American bald eagle, head back and skirling is the one I carry in my head forever. Sea eagle and bald eagle are close biological kin, sharing the white tail if not the white head and the musicality. And the bald eagle is also unfazed by the proximity of humanity’s habitat. The first one I saw was flying across a hotel car park in downtown Juneau, Alaska’s state capital. But what the two tribes have in common most obviously is to stand erect in a conifer tree, sometimes for an entire afternoon. So what I saw when I scoured the woodland across the bay from Port Ramsay was a shape I remembered from a three-week expedition to Alaska for the BBC’s Natural History Unit, twenty years before.

The Nature of Summer and The Nature of Spring by Jim Crumley are published by Saraband, priced £9.99.

A professional biologist with wide experience of working both in the UK and overseas, Rory Putman takes us with him on working trips to Iceland, East Africa, Nigeria and Indonesia, introducing us to the countries and their people, their natural history, and explaining some of the wildlife issues which have prompted himself and his colleagues to travel there in the first place. The stories cover episodes from more than four decades of working as a jobbing biologist overseas. Here, he visits the other worldly landscapes of Iceland.

Extract taken from A Biologist Abroad

By Rory Putman

Published by Whittles

We had hired a big, four-wheel-drive bus to haul us out along the tourist road to Gullfoss and on up into the central highlands. We were to be working in the Þjórsárver, a big water meadow some 20 miles across, tucked neatly beneath the Hofsjökull (High Glacier) on the central massif. The vast meadow of sphagnum and sedge, crisscrossed with streams springing from the glacier, is the main breeding site of the Icelandic pinkfoot – it was here, too, that earlier expeditions, such as that run by Sir Peter Scott and James Fisher in 1952, had come to work on the birds. But now it looked as if we might not make it. The phlegmatic Jonasson was not prepared to take us in. The thaw, it seemed, had been late this year, and although the roads were now clear of snow the route was still in the grip of permafrost. That is to say that the gravel or moraines beneath the track were still frozen solid, but pressure from the weight of a vehicle would cause it to melt and mire the vehicle concerned. The most Jonasson could offer was to take us up part way, to another site, and then come out again later to collect us and take us on into the Þjórsárver. And it would cost us the double trip. Seething with frustration, we had little choice but to agree. Time was short, for the Icelandic summer is a brief one and the snows would be in again by mid-September. So we accepted the inevitable and settled to the task of sorting through all our supplies to break them into two lots: sorting out sufficient food and essential equipment to last us the first few weeks before we could press on to the Þjórsárver itself. A night in the excellent campsite in Reykjavík – and an early start. Our change of schedule meant that we would head for a little place called Fossrófulækur: a ford across a stream some 30 miles short of the Þjórsárver, and safe on the eastern side of the Kerlingarfjöll mountains. Although the place is graced with a name, there is no permanent settlement; indeed, it is little more than a name on a map. A solitary hut stands on the stream bank and marks it as a posting point. A short way further down the stream, the water plunges into a steep and narrow gorge. Along the top of this gorge, on the basalt stacks which tower above the water, a small group of pinkfeet nest – outliers to the main population in the Þjórsárver. It would be worth a look and if nothing else, would serve for us to start to get the feel of things. At all events it would be better than kicking our heels in Reykjavík, despite the hospitable reputation of the Icelandic girls.

Jonasson drove the big four-wheel-drive bus himself. Perhaps feeling slightly sorry for us, he’d brought along one of his tourist ‘guides’ for the trip. A pity that neither of them spoke much English, but the trip itself was compensation enough. We rolled out of Reykjavík and off the tarmac. Past Geysir – perhaps the best-known of Iceland’s attractions for tourists, yet in reality, something of an anticlimax: a few desultory steam spouts hissing away behind a barbed-wire fence. The Great Geysir, which used to erupt every so often with a jet of steam hundreds of feet high, was dead now: throttled with the tons of detergent poured into it over the years to make it oblige. Houses thinned; we had left the last major township behind at Hveragerði of the heated greenhouses. For the most part now, the bus wound over bare rock or hard-packed soil surrounded by desolate bog-meadows or deserts of dry lava. Redshanks and whimbrel called from the lonely landscape; blacktailed godwits, ringed plovers and ptarmigan scattered from in front of our wheels until we pulled off the road mid-morning at the head of the Gullfoss, Iceland’s Golden Waterfall.

Gullfoss is justly reputed to be one of the most beautiful waterfalls in the world. The waters of the Hvítá, gathered together from a myriad of little glacial meltstreams from under the Hofsjökull glacier – from the very meadows in which we were to be working – plunge steeply through a narrow gorge, crashing 160 feet in a double span. The top ‘flight’ of the fall is impressive enough as one stands above it gazing nervously down, but its lower leap into a deep chasm is spectacular in the extreme – throwing rainbows into its spray which reaches up 100 feet or more. It is remarkable that one could then approach right up to it: to stand just above or right below. No written description can really do it justice: the noise, the power and the spray of it.

Jonasson had clearly been disturbed that we had come to Iceland merely to work. Satisfied now that he had shown us at least something of the island’s stark beauty, he started the bus and prepared to move on. The tourist route stops at Gullfoss. Even the hard-packed soil which in those days made pretence of a road this far went no further. From here on across the central plateau to Varmahlið and Akureyri in the north, the trail is marked clearly only on the map.

Jonasson pulled out his two-way radio and kept in constant touch with other vehicles along the route, checking on the weather and road conditions ahead. Every few miles we would lurch to a halt and, despite the language barrier, we soon cottoned on to the routine as we dug out the bogged wheels or threw heavy lava boulders into the ruts ahead so that the bus could crawl forward once more. These road-making stops became a regular feature of the next 60 miles, and we soon became used to piling out of the bus to reduce its weight as we teetered over flimsy suspension bridges. We didn’t mind at all: we were revelling in the desolation and the birdlife.

We crawled steadily onwards; now even the bridges failed: the cost of throwing bridges across the many rivers had dictated to a country with little money that they were to be built only on routes with regular or heavy traffic. On roads in the interior, a span was bridged only for passing a very deep gorge or an impassable torrent. The remainder were forded. But even these were not fords as we knew them: there was no concrete base, and a vehicle had to pick its way across the shifting boulders of the natural stream bed. Further, the Icelanders’ definition of a torrent is not the same as ours, and many of the ‘fords’ crossed raging waters so deep and so fast that we occasionally spied family saloons literally afloat in the race and only disgorged on the opposite bank some considerable distance downstream. Indeed this was apparently the norm, the expected; so much so that the roads on either side of such a stream are deliberately set askew from each other to allow for this same drift.

More birds: harlequin ducks now, golden plovers wheeling above the meadows, ptarmigan – Iceland’s only gamebird – and merlins. Still, everywhere, whimbrel and the little red-necked phalaropes. And our first view ashore of a glacier: one of the outfalls of the Langjökull, brooding, distant and terribly grey, at the far end of Hvítavatn. The whole landscape, grey and desolate: a true desert of volcanic sputum, wild and incredibly vast. And then, as we straightened our backs after another road-mending stop, the sun caught the glistening top of a perfect sugarloaf icecap: the Hofsjökull and the end of our journey. Although Iceland is of sufficiently high latitude that in the summer the sun never truly sets, there is nonetheless an extended twilight period as the sun dips towards the horizon and lifts again. In this red twilight the Hofsjökull looked almost unreal. The last dozen miles seemed to pass in a trance as we dropped down to the ford at Fossrófulækur. This Hofsjökull was to dominate our landscape and our lives for the next 13 weeks as we camped and worked in the meadows at its feet. No matter where we worked or moved, still it was there, watching over us, implacable. But somehow it was more impressive now, at a distance, than when we were close under its shadow or high up on its ice. After we’d pitched the tents, we stood and gazed at it in the dwindling light, poured a solemn libation of good malt whisky to its guardian spirits – and crawled to bed.

A Biologist Abroad by Rory Putman is published by Whittles, priced £16.99.

After shepherd Colvin Munro disappears, a mysterious trail of his twelve possessions leads into the Cairngorm mountains. His foster sister Mo and prodigal brother Sorley are driven to discover the forces that led to his disappearance.

As a former church minister and current owner of the local pub, Mo thinks she knows everyone’s story: Colvin’s Traveller mother, alcoholic war-vet father, Bolivian wife, musician daughter, bird-obsessed son, his friends and foes. Sorley, returning home from his life in the City, brings unsettling revelations.

Extract taken from Of Stone and Sky

By Merryn Glover

Published by Polygon

An uncertain April. By turns fragile and fierce, days shifting between mizzle and sun, nights curled up in cloud or naked to frost. The land is only half awake. Still a little crushed by that hard husband winter and not yet dreaming of summer, it heals slowly to the touch of spring.

Colvin was first up, dragged by a jangling alarm from his bed of unwashed sheets to the heap of unwashed clothes and down to the unwashed kitchen. Since Mo had left last summer, dust had settled on every surface, grime built up in crevices, mould spread. He had never known where to start or finish and Gid was no help and Sorley – so young and bewildered – little better. Eventually, Colvin had just given up the fight.

But he couldn’t give up on the farm. The sheep. They pulled him out in all weathers to be fed or gathered or lambed or rescued. Some days he cursed and wrangled with them like demons. Other times he felt protective, fond, even proud. A mix of Cheviot and Blackface with strains of Texel, Border Leicester and Swaledale, some of the ewes had bloodlines going back to the beginning of Rowancraig sheep walk two hundred years before, and in his grandfather’s time they’d been the prize flock of the strath. But that was history.

As Colvin stepped outside, the air was cool, the sky laden. Snow clung to the higher hills, but the ground on the farm was trodden mud. Last year’s lambs were pushed together in the fank, butting and bleating. On the far side of the pens, Gid was lighting a coal fire in a rusty 5 gallon drum. Bent over in his stained jacket and cap, with spidery red cheeks and lined face, he looked older than his 53 years and weary. Smoke rose in stinging plumes around him, making him cough and swear as he poked four irons into holes at the sides. Nearby, Sorley swung on a gate. His clothes were grubby, wellies split, his upper lip raw from constant colds, and he wiped it on the sleeve of his sweatshirt. No one put clean hankies in his pockets any more.

Colvin pushed through the sheep on the inside of the pen, the smells of damp wool and droppings rising to him on the waves of noise. Everything smelled of sheep: the house, his clothes, his hair and hands. He hauled the nearest hogg up against the fence, clamping it with his body and laying its right horn over a rung.

‘Here we go!’ Sorley yelped. He was like that. Bringing voice to the day’s work while Gid and Colvin said little. It was not companionable silence, but avoidance; a skirting around of the painful, unacknowledged things at the centre of their lives. The women. They did not speak their names or venture the reasons for their departures for fear of what that might reveal. They just carried on. And Colvin – now nineteen – carried his anger and grief like concrete in his lungs.

As for Sorley? Colvin saw that he was fed and clothed and sent to school each day, with something for lunch. A clumsy piece with jam, or a margarine tub of leftovers. At bedtime, he knelt beside him to hear the prayers that Agnes had taught and Mo had upheld.

I lie down this night

With the nine angels,

From the crown of my head

To the soles of my feet;

From the crown of my head

To the soles of my feet.

The head was a tangle of unwashed curls, the feet filthy, the angels nowhere to be seen. Colvin would hug him – feeling every rib under the flannelette pyjamas and the twiggy arms – and wait for the questions he could not answer. Till eventually they dried up and there was nothing in the hug but heartbreak.

Gid – who got up each day and went through the motions of the farm like a man on a chain gang – drew an iron out of the fire and pressed it into the hogg’s horn. There was a sizzling moment and then the same again with a second iron. R4. Rowancraig, 1974. Branded now, they belonged and would stay on these hills to breed for five years. Unless they died, or got barren, or difficult, or broke their teeth, when they would get marks in the horn and be sold for slaughter.

Sorley jumped off his gate and herded the branded hoggs into the next pen. ‘Whaw! Whoosh, whoosh!’ He clapped and glanced up at his brother and father. Nobody smiled. When the branding was done, Gid left his post at the fire drum and moved round to the side of the dipping trough, full of a stinking swill of chemicals to ward off scab, lice and tics. As Sorley released them down a run, Colvin ushered them through metal gates and one by one, shoved each hogg into the dip. Though it wasn’t necessary, he kicked them in. Gid then pushed them under with a long-handled broom and they surfaced a moment later, scrambling out of the trough, wet-brown and bleating.

Baptism by full immersion.

Of Stone and Sky by Merryn Glover is published by Polygon, priced £16.99.

In reading Roy Dennis’s latest book, David Robinson discovers hope, inspiration, and a lot of hard work needed for the future of our wild spaces.

Restoring The Wild

By Roy Dennis

Published by William Collins

Most of the nature books on my shelves are really about people. In them, depression, divorce, alcoholism and grief all find a cure in nature, wildernesses are traversed with poetic purpose, rivers walked as psycho-geographical pilgrimage. They might tell me quite a bit about nature, but usually a lot more about their authors’ psyches: if I met them in the pub, I’d know what to expect.

Roy Dennis’s Restoring the Wild is different. It tells you so little about the man himself that no sooner had I finished its 430 pages than I wanted to find out more. Internet interviews reveal a kind-faced man who looks two decades younger than his 81 years, who still talks with the soft burr of his native Hampshire even though he has lived and worked in the Highlands and Islands since 1959. But here too, it’s the work that counts, not his personal feelings or emotive responses to nature: if you want raptures about raptors, you’ll have to look elsewhere. However, if you want to find out how to help wildlife survive, thrive, and expand their own horizons, Roy Dennis is the very man: according to the RSPB, no-one else has done more for nature conservation in Scotland in the last 100 years. Informed by sixty years of fieldwork, his new book is a comprehensive guide to how well – or poorly – we are placed to rewild our skies, woods and waterways.

The work he is most famous for – reintroducing birds of prey to their former habitats – began in 1967 when, as director of the Fair Isle Bird Observatory, he was asked to help re-establish the white-tailed sea eagle on these shores. Once, there would have been around 1200 breeding pairs in Britain. Poisoned by famers, shot by fishermen, they were last seen in Scotland on Skye in 1916.

Reintroducing lost species isn’t a new idea – the capercaillie had been hunted to extinction in the eighteenth century before it was brought back by Lord Breadalbane at Taymouth in 1837 – but there were plenty of potential obstacles to overcome before the Norwegian sea eagles could be brought across to Fair Isle. Crofters had to be won over (what if the birds preyed on lambs or sheepdogs?), collection and transportation arrangements made, hacking cages designed and built, and a host of decisions made about the amount of human contact the birds should have, how long they should be kept in their cages, the best place to release them, and how much food should be provided afterwards without them becoming dependent on it. On the plus side, the island’s 3,000 rabbits, with over a century to forget all about the danger of predation by sea eagles, didn’t bother to hide when they saw one – even though it looked, in the words of one crofter, ‘like a barn door flying across the sky’.

That first project failed, but lessons were learnt. The four birds brought over from arctic Norway were clearly not enough, and subsequent releases in Scotland were made nearer sheltered cliffs where the young eagles wouldn’t be mobbed by gulls. These days, there are 140 pairs of white-tailed sea eagles ranging from Mull (where their value in ecotourism has been estimated at £5m a year) to Orkney. A 2007 attempt to establish them on the marshy Suffolk coast failed in the wake of a series of sensationalist stories about their potential threats to piglets, Christmas turkeys and bitterns, but a recent project to reintroduce them on the Isle of Wight appears to be succeeding.

Aren’t Suffolk and the Isle of Wight too er, douce for our wildest avian predators? Not at all, says Dennis. Nearly all of this land was their land once. The Isle of Wight-reared white-tailed sea eagle flying he tracked flying above the House of Commons might have had ancestors who fed on its land long before there was a parliament there, never mind a city. And not just raptors: storks used to nest (they did in 1680 anyway) on St Giles’ cathedral in Edinburgh, so why not again? Cranes give their name to more places in Scotland than any other bird (Cranloch, Cranstoun, Cranbeg Moss), and it would be good to welcome them back. Wolves howled in woods near our villages only three centuries ago – and should, Dennis insists, do so again, brought back along with lynx, elk and wild boar, so that our forests are no longer ‘ecologically dead’. Bears, too, belong here: according to the Roman poet Martial, the brown bears in the Colosseum in 80AD came from Scotland. Certainly beavers should again dam our streams, and not just in the remoter parts of the country either. Reintroducing the beaver is, says Dennis, a no-brainer: at a time of climate breakdown, we desperately need the ecosystems they provide, just as we need them to ameliorate floods and purify polluted waters. Farmers might complain at the damage beavers cause to riverbank crops, but they shouldn’t be growing them there anyway, what with the dangers of chemical run-off, and riverine trees the beavers could get their teeth into would be better for them and humans alike.

Projects to bring back all of these species to Scotland have at least been talked about in the last 60 years, although in most cases talk is all it has amounted to. But Restoring The Wild can point out some successes too: the defence of the red squirrel and the return of overwintering goldeneye ducks in the Highlands, the reintroduction of the red kite in both Scotland (the Black Isle) and England (the Chilterns), and of course, the recovery of the osprey from a single pair in the 1950s to close on 200 breeding pairs today, a programme further boosted by their 2001 reintroduction to Rutland Water. Dennis has played a key role in all of these projects, along with the reintroduction of the golden eagle to Ireland and of the white-tailed sea eagle to the Isle of Wight, but is modest about his role and is unfailngly generous about crediting other participants.

Perhaps, in fact, he is too modest to offer a specific manifesto for rewilding, although his book suggests the outline of one. We shouldn’t, he says, have to go to nature reserves to see nature: instead, we should give over half of our land to wildlife, and not just the impoverished uplands. It will take time to restore a fully functioning ecosystem with larger carnivores – it was, he points out, a full 60 years before the 1930s plans for Yellowstone National Park were implemented – but as our degraded land recovers from overgrazing by sheep and deer, and more extinct native species are reintroduced, ecotourism will flourish. If, in his hero Aldo Leopold’s famous phrase, we ‘think like a mountain’, and realise the interconnectedness of all living things, restoring nature’s balance will become feasible again.

It won’t be easy. If Dennis’s experience is anything to go by, the greatest opposition often comes from people one might expect to be on the same side. They’ll be too attached to their own projects to spare young birds for rewilding projects elsewhere, they’ll insist on lengthy feasibility studies or guidelines that don’t make sense, suggest alternative sites for translocation or prioritise plans to save another species. Meanwhile, choices narrow, priorities change, funding dries up, supporters move on. Not for nothing does Dennis title one of his chapters Endurance and another Bureaucracy.

Against that, the rewilders have their own networks too, often usefully international: bringing back the goldeneye depended on Swedish expertise, reintroducing the white-tailed sea eagles on the generosity of the Norwegians (although not so much at the start, when they still regarded the bird as a pest). Nothing makes this interconnectedness clearer than satellite tracking. Dennis was involved in this back in 1999, when he caught the first osprey for satellite tagging, expecting to find it overwintering in west Africa only to discover that it had settled on Spain instead.

I began with the white-tailed sea eagle, so I’ll end with one too – not from Dennis’s first, failed Fair Isle project but his latest one on the Isle of Wight. It’s a story about two young birds, G463 (a male) and G405 (a female), and their mapped early spring wanderings over England, Belgium and Germany and England and Scotland respectively. By the time you read this, they will have flown elsewhere, but at the end of April, you could have followed them on Dennis’s website (www.roydennis.org/category/latest-news), watching G463 become the first of the Isle of Wight ospreys to venture across the English Channel and discover the joys of Schleswig-Holstein (a great place for sea eagles, apparently), and G405 fly up to the Lammermuirs before heading back south.

On the website map, we can watch as they fly across borders. We know where they roost each night, whether they are flying with or against the wind, their height, speed, the landscape they’d see beneath them, even some of their prey. But we don’t yet know how strong their grasp on our world will turn out to be – whether G463 will return with a mate and help link up the European and English sea eagles, whether G405 would ever consider flying even further north next time, or whether they will further strengthen Roy Dennis’s hopes for a rewilded future. Yet oddly – especially oddly for a townie who can’t tell the difference between a sea eagle, a buzzard and a great bustard – I’m hooked by the challenge his book sets out.

Restoring The Wild by Roy Dennis is published by William Collins, priced £18.99

In Wild Winter, John D. Burns sets out to rediscover Scotland’s mountains, remote places and wildlife in the darkest and stormiest months. In this extract, he encounters deer in the glen of Strathconon.

Extract taken from Wild Winter: in search of nature in Scotland’s mountain landscape

John D Burns

Published by Vertebrate Publishing

Below, the Highland glen of Strathconon weaves its way into the horizon. To the east, the mouth of the glen opens out towards the market town of Dingwall. To the west, the fingers of the glen reach out to the outlying hills. Beyond the ridge lies Achnasheen, from where this chain of mountains rolls out to the sea loch at Lochcarron, and further still into the wild Atlantic. I know this place well. In my imagination I take an eagle’s ride over the sweeping ridges, across the dark lochs and down the wide glen to where the lights of houses twinkle at the roadside. The journey is filled with memories of days spent wandering in the rain, days on sunlit rock climbs, days on snow-crusted hills – some with friends and others alone with the landscape. These valleys and hills keep drawing me back. Here I am once more in this familiar glen, waiting for another day.

A glow begins to form in the V of the mouth of Strathconon. The light of the new day is creeping across the horizon and the features of the glen are slowly emerging. In the pale dawn, I struggle to make sense of light and shadow as colour gradually seeps out of the darkness, like a photograph developing. Soon I see a rocky crag above me; below, the dark wound of a stream bed winds across the floor of the shallow corrie. The shape of the landscape is no longer obscured as the reluctant night leaves the valley.

I miss too many dawns. I spend them idly in bed, or waste them buttering toast and bumbling about the internet. I am too concerned with the gibbering press or reading my mail, bleary-eyed. I never notice that outside a miracle is occurring. A new day is slowly coalescing into life. Every time I see a dawn, I vow that I will watch more of them, and yet somehow life distracts me and I forget to make space to wonder. At least I am here for this dawn. Now it will not tiptoe past unseen. The darkness is yielding, letting the burning colours of autumn slip through its fingers. Still I wait, listening to the forest breathing in the early morning breeze. I have been sitting amongst the trees for over an hour and it is difficult to keep warm. I shiver as icy fingers find their way inside my jacket. I try to ignore the cold, forcing myself to remain motionless, knowing that the slightest movement could mean that my nocturnal vigil has been wasted.

At last it comes, drifting through the trees: a deep, guttural, primeval roar. A grunting yell that has echoed through these trees and across these hills since the ice retreated thousands of years ago. A shape moves in the semi-dark, only to shift back into blackness as my brain tries to make sense of the gloom. Again the roar sounds across the glen, closer this time. After the echoes die, silence returns and the valley falls into a soft stillness. Minutes pass, until I think I may have given away my presence. The roar comes again, but still I see nothing. This time, the sound is followed by the rasping of great lungs filling with air. I can hear hooves picking their way through the boggy grass.

Out of the gloom swaggers a powerful creature, the master of this glen. He is so close that I feel the sound of his call vibrating the air as much as I hear it. He shakes his antlers, his breath clouding in the morning air. Seconds later, his challenge is answered by another male anxious to stake his claim. The stag turns his great antlered head and trots away towards his challenger. Now stags come from all directions, bellowing and roaring, each staking his claim on the rutting ground. As the morning grows brighter, the shape of the landscape reveals itself. Below me, the ground slopes away to a small ravine; beyond that, closed in by the hills above, there is a level area the size of half a dozen football pitches. This is where the drama I have come to see will unfold, where the battle of the rut is to take place. Now more and more stags are coming into view. Some beasts are huge and powerful, twice the weight of a man or more. Others are less impressive and will take another year to reach their full strength. These younger animals have no chance of winning the competition to mate with the females. Though they cannot win, the surge of hormones released as the autumn rut arrives compels them to be there.

Soon the amphitheatre echoes with challenges and answering calls from over thirty stags. Many are alone, but others have miniature harems of four or five hinds. The stags that have managed to collect a bevy of admirers have to fight off constant challenges from other males. The rut is an exhausting process for them, and by the end of the season, lasting from the end of September to the third week of October, many stags will have lost a fifth of their body weight.

Deer have acutely sensitive hearing and will flee if I so much as zip up a jacket. From the years of hunting by early man, they have learnt to detect humans by their outline. By staying close to the trees, I disguise the outline of my shape so they cannot see me. The stag that was close to me is challenging an older stag with four or five hinds in tow. He is roaring and shaking his antlers to show how big and strong he is. The old stag turns and faces him, responding to the challenge; if anything, he is larger than the animal I first saw. The pair walk parallel to each other for about ten minutes, each hoping that this display of bravado will intimidate the other into backing down and avoid a fight which could injure or even kill one of them. Although fights are common, stags try to avoid physical confrontations. Such battles are dangerous. A stag that gets an antler in his eye or whose internal organs are pierced will have a long, lingering death. Both the animals I am watching refuse to give way. On some secret cue, they turn and lock antlers. The sound of clashing bone echoes across the hillside. The stags grunt and snort with the effort of combat, their hooves sending grass and sods of earth into the air as they both struggle to keep their footing. They wrestle for almost ten minutes. At first the larger stag pushes the challenger back, his extra weight giving him the advantage. Then he stumbles on the broken ground and almost falls. The smaller animal chooses his moment and hurls himself forward, driving his antlers into his opponent’s side. The larger beast staggers back, blood dripping. He tries to mount another attack but his strength has left him, and he turns slowly and walks away. Perhaps his age was against him. It may be that he will never again hold sway over his own family of hinds. Defeat on the rutting ground has left him with a solitary life; he has lost his harem. The smaller stag strolls casually across to the hinds to make their acquaintance.

There are fights and roaring contests breaking out all over the rutting ground as males battle for dominance. Oddly, those not involved in the duels graze peacefully as if all this mayhem has nothing to do with them and they are just enjoying a light breakfast. This spectacle is being repeated all across the Highlands, in remote corries and glens, as it has been for thousands of years. I am watching an ancient ritual.

Wild Winter: in search of nature in Scotland’s mountain landscape by John D Burns is published by Vertebrate Publishing, priced £9.99.

Amongst all the loss of habitat and the animals and plants in spiralling decline, it’s easy to forget that there are a huge number of positive stories too: animals threatened with extinction having their fortunes reversed and their futures secured. In Back from the Brink, Malcolm Smith tells the stories of the Humpback Whale, The Black Rhino, The Iberian Lynx, the Mountain Gorilla and many others – and here in this extract, recounts the revival of the Florida Manatee.

Extract taken from Back from the Brink

By Malcolm Smith

Published by Whittles Publishing

The Mermaid That’s No Longer a Myth

The Florida Manatee

Hunted and killed over centuries for their meat, hides and oil, by the 1950s perhaps only 600 Florida Manatees remained. Now fully protected and with a huge public following, these gentle, plant-eating giants of the inshore coastal waters of Florida attract thousands of people who come to watch them in the warm river waters they seek out in winter. Boats kill or injure many; others die from cold stress or are poisoned by red algal tides at sea. Nevertheless, their numbers have slowly increased and today there are more than 5,000 in and around the state. Further population growth is by no means guaranteed as these endearing animals still face several problems. But they are back from the brink and the people of Florida are not going to allow their manatees to slip away.

Canoeing slowly along the tree-shaded Blue Spring, it was the sound of frequent noseblowing on the water’s surface that made the experience particularly surreal. These loud exhalations and intakes of air were a reminder that the aquatic creatures lolling away their winter months on the bed of this naturally warm, spring-fed waterway were mammals – and they needed occasional gulps of air to keep body and soul together. The stream, no more than a metre or two deep, was full of grey-brown, leathery skinned Florida Manatees, the adults three metres long, their youngsters smaller.

I was with Wayne Hartley – a Florida Manatee expert with the NGO, Save the Manatee Club – canoeing the 600 metres of Blue Spring stream from its confluence with the wide, slowly meandering St John’s River to its underground source. And in this short stretch of naturally warmed water Hartley counted no less than 102 manatees basking in its warmth. Sometimes he counts over 300; that wouldn’t leave much space here even for a small canoe! Blue Spring is one of Florida’s manatee public viewing sites and attracts tens of thousands of people each winter who come to admire these remarkable and endearing animals. The manatees share the crystal clear water with a motley collection of fish – Tarpon, spotted Florida Gar and Pinocchio-like Long-nosed Gar – as well as with the occasional American Alligator. Blue Spring is one of four warm-water springs discharging into the St John’s, a river that begins its slow-flow life over an almost pancake-flat landscape in a huge, unnavigable marsh and enters the sea on Florida’s northeast coast. A vital communication route for thousands of years in a part of the US in which much of the dense forest and swamp was impenetrable, today 3.5 million people live within its catchment. Manatees have used it in winter for evenlonger. To Blue Spring from the St John’s River estuary, it’s a 240 km manatee swim each way, a swim that, in the past, would have made them vulnerable to hunters. Avidly sought after for their meat, hides and bones, they were easy to catch and kill, especially in these shallow rivers during winter. By the 1950s or 1960s, they had been reduced to maybe 600. A concerted effort to protect and nurture their population since then brought their numbers up to around 3,300 by 2001 and to over 5,000 by 2014.

The Florida Manatee looks something like a grey-coloured, chubby dolphin with a flattened, wide tail that it uses for propulsion. Manatees lack the blubber layer that allows whales to tolerate cold; in water below 16°C they weaken and die. Through the summerthey are found all round the Florida coast in waters close to shore, in winter; when sea temperatures drop, they congregate inland at natural springs and other sources of warm water, including that discharged at electricity generating power stations around the coast. Florida-wide, there are ten significant natural warm water springs manatees can retreat to in winter plus around 13 warm water discharges from power stations, although they regularly use just six of these.

Before we start canoeing along Blue Spring, Wayne Hartley measures its temperature. ‘The spring temperature never varies,’ he comments. ‘Every time it’s a constant 22.5°C. That’s how it is.’ And that’s the way the manatees like it, many of the adult females with a youngster at their side and most of them just lounging away the winter months in these clear warm waters; the adults spending a good proportion of their time sleeping while smaller youngsters occasionally suckle.

As Hartley paddles us upstream, not only is he counting the numbers of adult manatees and their calves we pass alongside as they surface for air – or those we glide silently over as they sleep beneath us on the stream bed – incredibly he is also able to almost instantly identify each adult. His database of these animals is the longest running on any group of manatees in the world; over three decades of study. ‘Jacques Cousteau [film-maker and conservationist] heard about the Blue Spring manatees and came to film them in 1970. He filmed 11 animals, the only ones here then; six we kept track of and two, Merlin and Brutus, are alive today,’ says Hartley. ‘Judith came in to Blue Spring in 1998. She had calves over the years; they were Julie, Easter, Jip, Jim, Jemal, Jinx and an unnamed calf. Judith died in 2008 of unknown but natural causes. Julie, Easter and Jim are still with us. Julie had calves over several years; they’re Jolly, Mon, Jake, Jerry, Josh, Jaco and two unnamed ones.’ He points to those he spots by name as we pootle this way and that in the canoe to check them out.