Cynthia Miller is a Malaysian-American poet, festival producer and innovation consultant living in Edinburgh. Her poetry collection, Honorifics, is an astonishing, adventurous, and innovative exploration of family, Malaysian-Chinese cultural identity, and immigration, and its invention and emotional heft will surely result in an army of fans.

Honorifics

By Cynthia Miller

Published by Nine Arches Press

SAYANG / SAYANG

n. / love

I have lived with this word

for 28 years and only now

is it taking root in my mouth.

See also: beloved, sweetheart

n. / waste

The thought of throwing food away.

The last bite of beef noodles,

gone rubbery and cold. Go on,

don’t make me save it.

See also: regretful loss

n. / pity

All this fruit left on the branch,

steeping in its own rot.

Who knows how long we have

before a plastic bag

of windfall rambutans

turns into sweet slop.

See also:

We’ll eat it anyway / yes darling /

my dearest / love is always dear /

love / is never a waste / love is

eating scraps for fear of waste /

love is / chiding you to finish

your plate / love, eat up / eat up

love / what a pity / such a

shame to waste love / love, how

much we’ve wasted

SOCIAL DISTANCING

after Charles Simic

It was the epoch of transmutation. Some evenings the neighbours turned into jaguars and

dragged their dinner up into the trees. You could touch anything you wanted and watch it

change. A bench became a hammerhead shark. Confetti became slices of wet ham. A postbox:

a baby grand piano. Where Town Hall once stood, now was a giant baklava oozing honey.

Someone turned their arm into long tentacles of squirming fingers and went trawling,

terrorising the streets by grasping everything in reach. We were afraid to venture out of our

homes.

Everything became a record of what we touched, or hadn’t – where our hands lingered, or

didn’t – how much distance we could afford to put between ourselves and others – what it cost

us, what it didn’t.

CYNTHIA MILLER is a Malaysian-American poet, festival producer and innovation consultant living in Edinburgh. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Ambit, The Rialto, Butcher’s Dog, Poetry Birmingham Literary Journal, harana poetry, The Best New British and Irish Poets and Primers Volume Two. She is also Co-Founder of the Verve Poetry Festival.

Honorifics by Cynthia Miller is published by Nine Arches Press, June 2021, priced £9.99.

The Scottish BPOC Writers Network (SBWN) provides advocacy, literary events and professional development opportunities for BPOC writers based in or from Scotland. SBWN aims to connect Scottish BPOC writers with the wider literary sector in Scotland. The network seeks to partner with literary organisations to facilitate necessary conversations around inclusive programming in an effort to address and overcome systemic barriers. SBWN prioritises BPOC-led opportunities and is keen to bring focus to diverse literary voices while remaining as accessible as possible to marginalised groups.

Web links: Website | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Newsletter

The Library of the Dead is the first novel in T. L Huchu’s Edinburgh Nights series, and will show you the city in an entirely new and fantastical way. Here, Jeda Pearl discovers the influences that fed into T. L Huchu’s writing.

The Library of the Dead

By T.L. Huchu

Published by Tor

Content warning: death

With a bevy of entertaining and disturbing supernatural characters; a dystopian near-future Auld Reekie; and a plucky, young, ghost-talking detective named Ropa at the centre, The Library of the Dead by T. L. Huchu is an unflinching rollercoaster ride of a novel.

Ropa Moyo is a decisive and cynical teenager, who dropped out of high school so she could contribute to the household bills. Walking the outskirts of Edinburgh and educating herself with pirate podcasts, she plies her trade relaying messages from the dearly departed to their living descendants, occasionally performing exorcisms and helping spirits move on to ‘the land of the tall grass.’

We follow Ropa as she traverses the spectral everyThere, gains access to an elite occult library and sleuths through the stinking streets of Edinburgh trying to find missing children. Although she drops quotes from Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, Ropa has to evade and deal with some pretty terrifying beings. I spoke with Huchu to delve into Ropa’s Edinburgh and her extraordinary world.

Set in an eerily familiar Edinburgh, the effects of climate change and difficulties faced by much of the population – severe economic inequality, police brutality, corruption, exploitation – are simply facts of life and our protagonist Ropa’s environment. Did you originally plan to set the book in this near-future Edinburgh or did the setting and the related themes of inequality happen organically?

Every book has numerous moving parts that serve the whole and the setting is a critical component of that. It serves a greater purpose than is often paid attention to. A story that works excellently in twentieth century Harare may not necessarily play out to the same effect in twenty-first century Edinburgh. What you see in The Library of the Dead is a ‘third world’ Edinburgh, which doesn’t make much sense until you realise that prior to the Union of 1707, before Scotland benefited from the global plundering of the British Empire, it was the poorest nation in Western Europe. Therefore, this setting is designed to be jarring for the reader and to make them realise that in this universe the advances Scotland has made over the last 300 years are in the process of reversal. The chickens have come home to roost, in a sense. The book’s opening scene is in a house the historian Thomas Carlyle honeymooned in. This serves as an overt signal to the reader that we are telling a history of the future — the honeymoon is over.

With Ropa, her family and her friends Jomo and Priya, you’ve turned the idea of who gets to claim Scottish identity on its head. This is subtly and beautifully done – the streets of Edinburgh feel inseparable from Ropa and there are no ‘Where are you really from?’ moments. Her Shona heritage, culture and language are also woven with Gaelic, Scots and local slang. How deliberate was exploding the current assumptions around Scottishness and did your experience as a Black person living and working in Scotland influence these aspects of the culture in the book?

In a book like this, I suspect people would expect the characters to question their identity. Identity quests are, after all, an entire genre in their own right, and you’d be hard pressed to find a contemporary novel with a brown character in the west where the identity game isn’t playing out. But when I wake up in the morning, I don’t look in the mirror and think, ‘Oh my God, I’m Black. How did that happen?’ This is my default position, my factory settings, as it were. I choose to express my characters in terms of their core characteristics. Ropa is a strategist and a leader, Priya is an adrenaline junkie, Jomo is a beta male and insecure. The book is character driven and the characters take their heritage for granted, which I think is the way it should be when you’re a teenager. Because of this, what, I hope, you end up finding is that there are so many layers to their personhood, which I think is ultimately that which is universal about human beings.

Ropa knows Edinburgh better than any taxi driver! Did you regularly walk the neighbourhoods and landmarks featured in the book?

Edinburgh is such a small city and I’ve tramped through it for over fifteen years now, but each time she surprises me with something new. Most people think the historic centre of Edinburgh is all there is – that and a few touristy spots like Cramond or Portobello. You don’t really know this place unless you’ve been out to Wester Hailes, or Niddrie, or wound up at a random party in Liberton, or took the wrong bus and ended up in Trinity. If you wander with your eyes open you will see the city change with the seasons, old buildings torn down, new housing developments going up, businesses shut down and new ones taking their place. Edinburgh undergoes constant evolution – she is never the same city two days in a row. In fact, I would argue a single, unitary Edinburgh doesn’t exist. What you have are multiple Edinburghs, grosstopically linked (to use a China Mieville formulation), different cities existing within the same space but out of sync spatially and even temporally.

The cast of ‘deado’ ghost characters were really entertaining. Did you spend a lot of time in Edinburgh’s graveyards?

There’s a lot of fascinating history to be unearthed in those old graveyards. Reading the headstones will teach you things you never knew about life, love and loss. These are peaceful places with interesting flora and fauna. But, ultimately, when you visit the graveyards of Edinburgh, you’re confronted with your own mortality, which is what all great literature is really about.

Ropa can communicate with deados through playing her mbira and there are references to Shona and Zimbabwean music throughout the book. Do you play the mbira and is it part of your spiritual practice? Who are your top five mbira musicians to listen to?

I peaked at playing the triangle in nursery school and my sense of timing and rhythm is rather poor, so I don’t play any instruments. I’m a cultural Catholic hovering between agnosticism and atheism, but I have an interest in spirituality because of how central it is to the vast majority of people I share the planet with, including my own family. I believe it exists as an attempt to answer the really important questions about the nature of existence which plague us all, and so one cannot dismiss it outright. The mbira plays a central role in traditional Shona religion and there are many fine musicians who employ it in their craft. If I want to listen to a more traditional sound that draws deep from the culture, I turn to Mbuya Stella Chiweshe, Sekuru Gora, and the outstanding folk ensemble Mbira DzeNharira. If I feel like listening to a more contemporary sound, then I turn to the late Chiwoniso Maraire and the dazzling Hope Masike – they make it fresh and cool.

With nods to disturbing elements, such as women and girls being permitted to carry knives up to six inches long for self-defence, plus references to the scrap metal rush and times before and during the cataclysm, Ropa doesn’t hold back on the realities of living in her world. How important was it to you that these aspects weren’t glossed over and that Ropa would just get on with living her life (while investigating why kids are going missing)?

Ropa is your archetypal reluctant hero. She’d rather be getting on with her life than chasing villains around Edinburgh. And so, she is immersed in the day-to-day problems of the world she lives in. This is not Bruce Wayne going out to kick arse and then retreating to his comfortable mansion after the deed is done. For Ropa Moyo, heroism comes at great personal cost because her life is precarious, she lives from hand to mouth. And because she is from the underclass, bearing the brunt of the reality she lives in, these problems are an unavoidable part of her quotidian experience. For her there is nothing special about these things. That is why her tone is very matter of fact.

As well as funny and poignant moments, there are some chilling supernatural experiences in the book. Does this come from a personal tradition of folklore or storytelling and what folklore traditions inspire you?

I draw from so many sources, it is hard to even keep track of it all. If you know the history of Edinburgh, you will know there’s a lot of spooky shit that’s gone down through the ages. But because of Ropa’s heritage she is able to fuse this stuff with things she’s learned from her nan who is Zimbabwean. Some of the stuff I made up for myself, e.g., the Midnight Milkman. . . or did I? RIP Sean Connery. The spooky house in the novel came from a strangemare I had a few years ago. Greek mythology, which I’ve been interested in since primary school, also plays a very important role in all of this. And so, when you play around with all these things you, insha Allah, come up with something fresh, maybe even original.

Maternal bonds run deep throughout the book and, The Library of the Dead is dedicated to your mother, Josephine Huchu. Would you be open to sharing how your mother inspired and still inspires you?

Everything I am today is because of her. I work with words, but they are inadequate as a medium to convey anything truer than that.

Can you share any information about book two in the series?

Book two is currently on the hob. It’s titled Our Lady of Mysterious Ailments and you can expect even more thrills, unearthed histories, villains, and changes in Ropa’s life! Anything else about this manuscript is currently only accessible to high level security cleared spooks at GCHQ and, begrudgingly, the NSA — what can you do, hey?

Which Scotland-based Black writers and writers of colour are you excited about right now?

You’ve got very established authors like Zoe Wicomb and Leila Aboulela working in literary fiction. Or if you thinking of tartan noir then you want to read Leela Soma, author of the brilliant Murder at the Mela. But I also feel that beyond the writers of colour already working here, publishers like Canongate who have great editors like Ellah Wakatama Allfrey are going beyond that to publish exciting diverse authors from around the globe. From that catalogue alone I’ve already read Taduno’s Song by Odafe Atogun, A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki, Stay With Me by Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀, and I’ve got Courttia Newland’s A River Called Time on my bedside table. It’s this sort of mix that fills me with hope for the future of literature in Scotland.

Jeda Pearl Lewis is a disabled Scottish-Jamaican writer and poet. She’s performed at StAnza, Event Horizon, Inky Fingers and Hidden Door and was awarded Cove Park’s Scottish Emerging Writer Residency in 2019. Her writing is published by Black Lives Matter Mural Trail, New Writing Scotland, Not Going Back to Normal, Tapsalteerie and Shoreline of Infinity. @jedapearl jedapearl.com.

T. L. Huchu is a writer whose short-fiction has appeared in publications such as Lightspeed, Interzone, AfroSF and elsewhere. He is the winner of a Nommo Award for African SF/F, and has been shortlisted for the Caine Prize and the Grand Prix de L’Imaginaire. Between projects, he translates fiction from Shona into English and the reverse. @TendaiHuchu

The Library of the Dead by TL Huchu is the first book of the Edinburgh Nights series, and is published by Tor, priced £14.99.

The Scottish BPOC Writers Network (SBWN) provides advocacy, literary events and professional development opportunities for BPOC writers based in or from Scotland. SBWN aims to connect Scottish BPOC writers with the wider literary sector in Scotland. The network seeks to partner with literary organisations to facilitate necessary conversations around inclusive programming in an effort to address and overcome systemic barriers. SBWN prioritises BPOC-led opportunities and is keen to bring focus to diverse literary voices while remaining as accessible as possible to marginalised groups.

Web links: Website | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Newsletter

Clementine E. Burnley is a migrant mother, writer and community organiser. During a writing workshop she was introduced to the poet and playwright Jay Wright, who lived in Dundee in the 1970s as a poet-in-residence. In this piece, Burnley explores how creative people can connect across space, time and communities.

The Workshop

I so very much want to be a poet in communion with other poets. I want to attend workshops held in distant physical locations. I have a fourteen year old, and no-one to provide childcare. The internet makes it all possible. I find out about the Obsidian Foundation on the facebook page of the Scottish Black and Minority Ethnic Network. In a matter of weeks I become an Obsidian Foundation student. The Obsidian Foundation organises a brand-new, weeklong Black Poets’ Workshop, online.

I first hear about Jay Wright from Dante Micheaux, a much anthologised, prize-winning poet, and most relevant at this moment, my workshop tutor. It’s Wednesday. We are in the hump day. ‘We’ are the ten poets in Group ‘C’. I say ‘we’ a lot since moving to Scotland. Mostly I mean poets. We sit in front of our screens, blear-eyed. We are at home, alone with others, but somehow we live and breathe poetry together. We do Home school, Pandemic, and Poetry together.

I am distracted by pandemic homeschooling. But the reason I am here is the pandemic. Organisers cancelled events. Some moved events online. Rather than be upset, I savour this novelty, which means hardship for many who are not able to work from home, or who fall on the wrong side of the digital divide. I have access to a decent internet connection and to a computer. I do not have to pay the fare to London, — workshops are always in London. I don’t have to pay for expensive accommodation or grovel for childcare support.

‘Jay Wright is, unequivocally, the greatest living American poet,’ Dante Micheaux says. Wright is a poet, jazz bassist and playwright. The poem Dante has chosen is from Wright’s first collection; The Homecoming Singer. ‘Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting’ takes me back to a Protestant childhood, where I spent almost every day in church.

Back to the workshop.

Dante Micheaux is still staring into the camera. I hear something about ‘poetry as a marginal art form’, how he’s ‘vexed’ at Jay Wright’s being hyphenated, reduced to African-American poet, made into a marginal figure in American poetry.

Dante Micheaux rivets us. He reads us ‘Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting’. We read it ourselves. He asks us what we notice about it. We puzzle at the text. At first, we miss the point, and then we work it out. Christ comes, but no one in church realises the shabbily dressed unobtrusive stranger is the answer to their shouted, performed prayers. I take the scene as a kind of sacred offering, from Dante to us.

Back to the workshop. Dante Micheaux is staring into the camera. The words fall into my ear. I write down: Wright, Jay. Transfigurations. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

‘Redemptive’, ‘difficult poet’, ‘like Walcott’, ‘refuses the saga of Europe as the centre’.

‘Pick a poet,’ Dante says, ‘read everything by that poet.’

Everything by Jay Wright is ten collections between 1971 and 2008. Lots of reading aloud, ahead.

We’re writing till late, or early depending on your point of view, if that matters in Black poetry boot camp.

For me, it is midnight til three in the morning. Late nights are not my thing. I am a lark, awake and active from about five in the morning. Early rising is a holdover from childhood. Every morning my mother, or grandmother woke us up before first light for devotions.

For this workshop, late nights have become my thing.

When the workshop is over, my ears ring with instructions from all the different tutors.

Dante Micheaux only says, ‘If you like a poet, then study what they do.’

The poetry

When I look for The Homeward Singer – it is out of print. My order gets stuck in customs. When the strong brown paper envelope arrives two months later, I blink, surprised, at the battered secondhand book. The poems in The Homeward Singer must have been in Wright’s mind in Dundee. It was published the year after he left. I look for Scotland in Jay Wright’s poetry, but I don’t find it in his words.

The Poet

Weeks after the workshop, I discover Jay and Lois Wright were based in Dundee for two years at the beginning of the ’70s. I imagine a tall, light skinned man. He’s athletic. Jay Wright played college baseball. He has a paper map of Eastern Scotland in his hand. His eyes narrow as he contemplates the Firth of Tay. I try to relate to this brilliant, learned man. Few fixed points exist on our shared landscape. The city itself, people, the university, the local culture. The internet doesn’t exist in 1970. I discover the Kingsway, a ring road completed in 1919. The Kingsway passes through Dundee on its way from Perth to Aberdeen. The photograph I see from 1962 shows only three cars on the entire stretch over green verges to the horizon. Now there are at least twelve roundabouts on the Kingsway to cope with the city’s rapid growth.

I speculate on the experience of a black poet-in-residence. While living in Dundee, Wright must be quite visible. He’s seen as not being from ‘here.’ I wonder if a visiting Fellow interacts with the ‘institutions,’ in a very different way to a Black Scot, who makes their art here and is not going anywhere else. I wonder which communities open up for the racialised artist in the 1970’s. His stay is time-limited. There might be little point in setting root.

Jay Wright is a poet in habitual movement from one place of residence to another. Dundee is a single stop in his migrancies. Born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, he moves to San Jose, California and then to Germany, eventually travelling all over Europe.

The Poetry of Movement

A blurb on the back cover of Transfigurations highlights Wright’s talent as a ‘synthesiser of cultures’. His poems move between African, European, Native American, Latin American cosmologies. Wright combines rituals, rhythms, cadences, from different continents and cultures. The same blurb mentions the ‘sense of exclusion’ in his work.

Wright, a keen observer of culture, must know that Dundee is famous for it’s jam, golden jute and jubejubes. Within a few clicks I know the British East India Company sent shipments of golden jute thread from Kolkata to the flax spinners of Dundee. Wright’s work is fully conscious of the histories of capital and his place within it.

After two years in Dundee, Jay Wright travels to Mexico where he writes ‘Boleros’. His writing in this collection is influenced by Indian faith, world religions, Asian Indian and Catholic European ideas.

In his work, Wright claims a place in the centre for his own cultural identity. He reasserts connections between African religions, ancient cultural rites and modern American life. In that way his work reinscribes those made marginal, into the centre. His poetry carries the rhythms of West Africa but also the cadences of Native American cultures. Different histories confront each other in his words.

‘Twenty-two tremblings of the Postulant’ from Improvisations Surrounding the Body:

‘You understand the danger of being strippped

of totem and amulet, the bliss of being cold

to a god’s stroke and being set, untangled

darkened in wisdom, in the direction of a self

you may never reach.

A migratory man…

We own no land,

no love, no art, no death.’

I look up transfigurations and find when something changes radically into a more beautiful shape, it has been transfigured.

Poets of Colour in Scotland now

Plenty has changed between Wright’s time and now. The Black poets who I make work with, or alongside in 2021, are post-Brexit. We are a year into the pandemic. Afro Diasporic, Caribbean, Asian and Latinx people in Britain continue to get sick and to die at higher rates than white Britons. Despite physical isolation we’re actually hyper connected to each other through online spaces. I have a theory that despite the lockdowns, many creatives of colour are more connected than would have been possible in the ‘70s. When I meet with the creatives of SBWN at a Black Writers group, they are delighted about the diversity of events online.

‘A year ago, I couldn’t have dreamed this up.’

Jade Mutyira says the SBWN network is, ‘One of the best things in my whole life.’

‘I can’t believe the stuff I’m doing, the people I have access to!’

We talk about what impact digital spaces have on whether and how we make art.

‘A year ago, I couldn’t have dreamed this up.’

I talk with Jeda Lewis about looking after children, making work at home, and living with a chronic pain condition, about access to a greater audience, expanded access to community, and to mentors. It’s been ‘Wild, making work at home, trying to earn money and making art and trying to show it to the public as well.’

‘Yeah, so that it’s not just a private activity.’

For writers like Sharon Croome and Jeda Lewis with health problems and mobility issues, being online, is ‘Transformational.’

Online art spaces allow them to maintain connections to distant networks, come together safely, plan, organise, and think of ways to support each other.

‘There are so many more opportunities.’

‘Joy, pain, inspiration. Anger,– because disabled people have been fighting for better access to arts employment, but this was possible all along.’

We talk about not going back to normal, what normal was, and what a new normal could look like. Sharon and Jeda worry about access for people who haven’t had access before. Jeda mentions Not Going Back to Normal, a collective disabled artists’ manifesto created in Scotland last year.

‘That access has to be maintained for people as the lockdown eases.’

‘We can’t go back to making things inaccessible. I hope it stays hybrid.’

Sources Quoted:

Dante Micheaux has won the Four Quartets Prize, has received fellowships from Cave Canem Foundation and The New York Times Foundation, has been shortlisted for the Benjamin Zephaniah Poetry Prize, and the Bridport Prize.

Blog Entry. A Different Center by Dante Micheaux

https://blog.bestamericanpoetry.com/the_best_american_poetry/2010/09/a-different-center-by-dante-micheaux.html

Griffith, J. (2015). Mingus in the Workshop: Leading the Improvisation From New Orleans to Pentecostal Trance. Black Music Research Journal, 35(1), 71-95. doi:10.5406/blacmusiresej.35.1.0071

Not Going Back to Normal Website www.notgoingbacktonormal.com

Wright, Jay. Transfigurations. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000.

Clementine E. Burnley is a migrant mother, writer and community organiser. She loves to walk in the Scottish Highlands. Her work has been shortlisted in various short story competitions and most recently, nominated for a Pushcart Prize. At the moment she’s a Reader in Residence at Smokelong Magazine, and a contributing editor at Barren Magazine.

The Scottish BPOC Writers Network (SBWN) provides advocacy, literary events and professional development opportunities for BPOC writers based in or from Scotland. SBWN aims to connect Scottish BPOC writers with the wider literary sector in Scotland. The network seeks to partner with literary organisations to facilitate necessary conversations around inclusive programming in an effort to address and overcome systemic barriers. SBWN prioritises BPOC-led opportunities and is keen to bring focus to diverse literary voices while remaining as accessible as possible to marginalised groups.

Web links: Website | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Newsletter

We continue our ‘Introducing . . .’ series, where BooksfromScotland highlight the work of up-and-coming writers, with the poetry of Clementine E. Burley.

Clementine E. Burnley is a writer, poet and community organiser based in Edinburgh. Her work has been featured in Ink, Sweat and Tears, and Barren Magazine, as well as the Bath Flash Fiction Anthology anthology One for the Cows. She’s been in the final selection for various flash and short story prizes. In 2021 she made a video for the Edwin Morgan Trust. In 2020 her work featured in Sorry I Was On Mute, part of the Fringe of Colour Films. She’s an alumna of The Obsidian Foundation and the Purple Hibiscus Trust.

On Luing

The scent of early, ripe soft fruit

is unfamiliar among last night’s wreckage

of bottled chilli sauces on the fridge top

He has brought the groceries in before

the slow trudge back into a world

I now imagine

While I work from home

as if work had not gone on at home

all the while

The thing I do at home is called love

the thing he does outside is called work

He has left the fire banked and porage oats in a bowl

He has left the creamy white milk ready to be poured

And later I will point to the strawberries grey with rot

and no more English than the pickers were Spanish

or I, Scottish but here we all are

And later his eye will find

the few good fruit I overlook

The lone citizen must save himself

On the first night, the warden flashes a thumbs-up sign. His face is tidy.

His fingers are onion-pale.

We stay cool.

We boil coffee from the Inter store; play music, mock, dance, tease. We knead flour and water, press the aseeda flat with empty beer bottles, clap sticky hands and watch the tiny white plumes spin from our fingers. We count hard currency. We reach too hard for our beautiful, unreachable futures.

Citizens pass back and forth under our single glazed window. She low sings. Époupa é ngéa, a little, perfect tune I will remember in fragments through the months of physical therapy. Head snuggled into her neck crook I draw in the unbaked bread smell. Her warmth penetrates my skin. I know époupa, is rain in energetic motion. Months later, it hurts to see rainclouds.

The second night, eager fists beat a tattoo on the entrance.

‘Tonight’ they chant.

The sour taste is fear. I want to ask; does she snatch at dreams and wake with her jaw clenched.

We pretend. On the other side of the city, open runways await us. We drape our coats over our faces. We escape over the rooftops. The old brightness shines from her eyes, then with a howl, the night ruptures. A thorn bush twines dark tendrils around us. The police stand back, pistols holstered. The warden’s trim figure fades.

This could be our country too; our rage, our inner void, our glut of flesh.

Towards morning, silence mounts like hate. Our medicine as Molotov cocktails rattle the first-floor windows is to make aseeda, gather in the basement kitchen and knead the loose shreds of us, bodies in search of places which no longer exist, coordinates on a map gone missing. We clap.

‘Outside,’ they chant.

For Caster Semenya

(After Gwendolyn Brooks)

We stand tall. We

love soft. We

Boss tough. We

Chase dreams. We

Stay strong. We

Shoot straight, We

Dig deep. We

Don‘t quit. We

Zone in. We

Train first. We

Move fast. We

Kick ass. We

Win gold. We

Die hard.

‘On Luing’ was performed as part of the 2020 Edinburgh Fringe of Colour film series Sorry I Was On Mute, directed by Hannah Lavery.

‘The lone citizen’ was published in the 2020 Ad Hoc Fiction Anthology, With One Eye on the Cows: Bath Flash Fiction Volume Four.

You can find out more about Clementine’s work by following her on Twitter @decolonialheart and Instagram @ewokila

A new novel from Alan Warner is always something to celebrate, and we’re thrilled to share this extract from Kitchenly 434 with you ahead of its publication later on in the month. A tale of the Golden Age of Rock n’ Roll told from an insider and outsider, it explores self-awareness and self-delusion in a time when great change is around the corner. Here, we are introduced to Crofton Park, butler to world famous guitarist Marko Morrell.

Extract taken from Kitchenly 434

By Alan Warner

Published by White Rabbit

No one behind, so I slowed the Volvo hatchback even more to gaze across, a single hand on the steering wheel. I was one of the few inhabitants of the vicinity who knew the concealed topographies beyond that calculated assemblage of trees ; a frieze of multi-coloured leaves – just like those dark Chinese Coromandel screens with their decorative lacquer in the master bedroom, behind which Marko’s unbearable lady – Auralie – changes into and out of her latest international fashions, two or sometimes three times daily.

Within those perimeter walls, I knew the tristesse of every weeping willow along those crawling waters’ edges. Overlooked by the precipitous manor house, I knew the laburnum slope with its stepped rill in ornamental brick, its rivulets channelled down from the moat to the twin culverts at the riverbank, cascading the acoustic steps. I knew the double mill buildings now connected by their two modern, triple-glazed air bridges.

Every time I approached Kitchenly Mill Race, I began to anticipate the paradisal compound of dolorous laburnum and lavender banks which scent the decorated interiors when the summer manor windows are fixed open on their ornate securing-arms. All of these enchantments which were hidden from common view.

Without fail, when advancing on Kitchenly from east or west, or down the farm track to the north, I would feel the same occult conviction, the same magic of its acreage. I fully believed in the abstract energies of its frequently-absent young owner. His aura, which to my mind, reached from the soil of his extensive grounds to beyond the very tips of his trees.

Even the lands around the house : solitary elms mid-field, encircled by cultivator markings, or the semi-transparent beech hedgerows split by unpainted tubular metal gates ; the roadside walls, the ditches, the pasture corners trodden bare by jostling livestock gathering at their troughs ; surely these hinterlands must be alive to the aura of that dwelling close by ? Could meandering Sunday motorists not sense world fame on their approach ? I was crazily convinced that every part of this landscape around Kitchenly Mill Race vibrated with an overpowering presence. Like a leaking nuclear power station, the radiation of Marko’s vast talent, his mystique, settled and shimmered like dust on the tops of telephone wires, on the flowers and leaves, nettles and bitter dock, lanes, fields and sunken tracks for at least several thousand yards about. I was dumbly certain everything was infected by his main residence and its glamorous pollution.

For six years in the smaller mill house – with its clamped but still-functional water wheel – I had held my staff flat of two small rooms and a kitchenette beneath. Sometimes, stepping through the gravelled car park from some chore in the big house, moving towards the white, fretworked wood of the footbridge across the headrace, I would spot a wood pigeon launching itself with a slap from one of the far pine trees on the other side of the boundary wall. That grey bird would slide across the public road, clear the orange brick and ivy, cross the driveway lawns and make upward ascent onto the corner guttering of the larger mill house. There it would resume its coo-cooing loop of song and I would feel a sense of outraged sacrilege. The feathered ones alone did not acknowledge the demarcated boundaries of this private Shangri-La. The impunity of the birds’ trespassing from public land into Marko’s haven was still somehow astonishing to me. Birds may fly free, but the very airspace above the renovated manor, the mills, the river gardens and outhouses was, as far as I was concerned, privileged and private too.

Kitchenly 434 by Alan Warner is published by White Rabbit, priced £18.99.

Author Elle McNicoll was one of last year’s huge success stories with the publication of her debut A Kind of Spark, which recently won the Blue Peter Award for Best Story. This month she has released her second middle grade adventure, Show Us Who You Are, which sees her protagonist Cora take on tech conglomerate Pomegranate on their troubling plans with AI. Here, Elle tells us more about her book and gives us a taster.

Show Us Who You Are

By Elle McNicoll

Published by Knights Of

Show Us Who You Are by Elle McNicoll is published by Knights Of, priced £6.99.

Helen McClory’s much anticipated second novel, Bitterhall, is released in early April, and we couldn’t wait to give you a glimpse of it, and to introduce you to Daniel, Órla and Tom, three characters thrown together by a grimy flatshare and drawn into a web of desire, obsession and secrets that leads to a shattering conclusion.

Extract taken from Bitterhall

By Helen McClory

Published by Polygon

Autumn Soft

I am on the swing in the garden, under the oak bough, late August night, a couple of beers tipped over beside me in the short mossy grass and my heart is a neat bundle of sticks in love with the dead and the unreachable. Up in the house a single light shines; first floor, the bedroom, my bedroom, so it looks like there’s somebody up there. And I, hazy, imagine them looking down on me, and at the same time down on the whole of this city, with some dispassionate warmth, like a God.

My head lies against the swing chain, the fabric of my scarf at my throat grey in this light, blue indoors, I’d grabbed it on leaving the new housemate and his girlfriend at a strange moment all together in the kitchen. I think how he, Tom, is legendarily good looking. Only later will I see Tom unravel and almost fall, and I will catch him.

Work is just beginning to launch itself to its full purpose, and I think of the objects I will handle, which I have seen in the catalogue or taken out of packaging and put into the safe, so frail in my careful hands; I think of the monumental paperwork, the email chains to and from absent bosses mostly floors above my soundproofed basement room.

I feel for the metal chain of the swing and kick off again, a gentle sway, a little more, wind in the face, cold, and the ground makes a good sound when I kick it. I don’t think about the thing I am trying not to think about. Shhhh. I think for a while about this ground, leafy, dirt in footprints, old scuff-mark furrows from swing-riders, and of the tensile strength of the chains, and of the cold of the seat. All I can think, just for a moment, is: Just be calm. Bed soon. Back up to the diary I am reading and I do not yet know of everything wild that waits above us to kick off, with my housemate, his girlfriend and me.

I want you to love me, if I’m being honest. That’s why I start so gently, in the garden, in the present tense. A good story begins tipsily in a garden, and carries on through well-proportioned rooms in the past tense in which blood is being spilled and was spilled, is measured out already, and the possessors of that blood were embarrassed at its spilling, and hold their hands over the wounds, pretending everything was fine. When exactly is this happening, and to whom is it happening, and who is making it happen? We begin to become tricky, don’t we, when I write in the first person. What tense do my intrusive thoughts manifest in? Somewhere between the first and second, like a harsh note in a piano recital, a piece so often played it should be clean of errors, yet here and here again the wrong note spikes in the same predictable, always jarring way, repeating itself, a bad inorganic refrain.

Intent is the issue, too. It’s a holiday to take up a different tense, a different perspective. But I’ll let you decide who is who, who is not who, who is real (real enough, then?). For a clue (as much as I’ve got), there is a centre to this whole thing. It’s up to you to mark it.

Aside – everything is an aside. Except the centre. That is the centre. Find it. Come along and around me. Us. Fill the edges of this thing.

Bitterhall by Helen McClory is published by Polygon, priced £8.99.

It has been said that readers are not ready to read pandemic novels yet, but when they are as thrilling as Ewan Morrison’s latest novel, How to Survive Everything, we think it’s safe to ignore that opinion! We caught up with him to talk about some of his favourite books.

How to Survive Everything

By Ewan Morrison

Published by Saraband

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

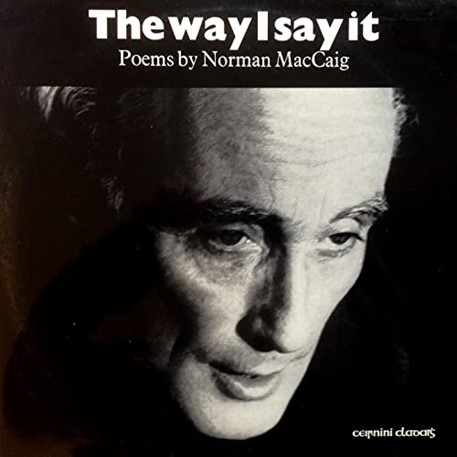

As a child, I used to tear through The Adventures of Tintin and Asterix the Gaul, but my first real experience of the power of the word was actually an audio recording of poetry. It was my parents’ copy of the album The Way I Say It – Poems by Norman MaCaig, read by Norman himself. There are so many inspired poems on that record, all read with such force and occasionally with MacCaig’s gently smiling wit: Man in Assynt, The Root of it, Truth of Comfort. I must have been about ten years old and I listened to the crackly LP, once every few weeks, with my headphones on, in between bouts of AC/DC and Black Sabbath. It struck me then that this old man was very wise, and that his wisdom was all tied up in this game he played with language. As MacCaig wrote ‘Ideas can perch on an idea, and sing’.

Forty years later, I find myself quoting his line from the poem Sparrow: ‘To glide solitary over grey Atlantics, not for him; he’d rather a punch up in a gutter.’ I only recently realised he was talking about a certain kind of people. Wonderful, wise Norman with his dry wit, introduced so many kids of my generation in Scotland to the wonder of words.

Album cover. The Way I Say it. (1973)

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest book How to Survive Everything. What did you want to explore in writing it?

How do we survive things that seem too much to bear and that challenge the daily story we tell ourselves about reality? That’s what I really wanted to explore in How to Survive Everything. It’s written from the perspective of a teenage girl, Haley, who, along with her little brother is abducted by her father, Ed. Ed is a divorcee and a ‘prepper’ who’s been secretly preparing for the end of civilisation for years with a group of survivalists in an armed hideaway in the wilderness. The book is Haley’s own survival guide as she adapts to severe survivalist lockdown and as she uncovers her father’s obsessive faith in a world-ending pandemic. Haley’s mother ends up trying to snatch her kids back, and so Haley is caught in the middle, having to decide whose worldview to believe in – her Dad’s global apocalypse or her Mother’s belief that the pandemic isn’t even real and that Haley’s father is criminally insane.

There’s dark comedy in the novel as Haley explores questions of ‘Who can I believe and trust?’ in this era of fake news and conspiracy theories. The question ‘What life-story can we live by? ’lurks beneath How to Survive Everything, and probably behind every book I’ve written.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

I think The Road by Cormac McCarthy had a huge impact upon me – probably from about 2012 onwards. It’s an Apocalypse narrative but it is permeated by such a profound sense of love between a parent and a child. Care, compassion, intimacy in the face of such horror. It’s impossible not to cry when reading The Road, and also to be amazed by the simplicity and beauty of its prose. It shook me on a number of levels. Personal it told me that being a father is incredibly important, and in terms of writing it made me want to take on the big themes we face as confront mortality. McCarthy has stripped away all that’s superficial in our civilisation and our language to ask ‘What really matters?’ It’s devastating book, a real life-changer.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

Back in the 90s I was blown away by Revolutionary Road by Richard Yates. I just couldn’t believe that this forgotten classic from 1961 could have such relevance to my generation. It’s all about a couple of beatniks who’ve sold out, who struggle against their stereotypical life roles and who plan to escape. It’s painfully psychologically honest. I loved that book so much that I kept loaning it to people, and then I’d have to buy another copy because I never got the loaned copy back, because it in turn was, without fail, always loaned to someone else. It spread, virally, because I would soon discover, I was not the only person doing this. I recall, meeting a friend in London who worked in film (he died of cancer in 2014) and we both got raving about how much we loved Revolutionary Road, and how we’d each bought about five copies over the years, all of which we’d ended up sharing or giving away. We realised that we’d been part of this strange underground sharing circle of devotees that spread across countries and borders. It was like we were dissidents sharing forbidden Samizdat books in the Soviet era. That was my first sense that a book can create a devoted secret society and make new friends. Oddly enough the huge underground friend-circle around this book led to the Hollywood movie being made in 2009.

The book as . . . object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

Ah, now, perhaps this is unfair because Dante’s Divine Comedy with the illustrations by Gustave Doré (1861) is as sublime as the illuminated manuscripts of the medieval era, but unlike those museum pieces it can be owned and taken home.

There is a lovely story about Doré’s edition of Dante that I like to call ‘The ass and the angels’. Originally Doré was supposed to create twenty illustrations for Dante’s epic poem with its three sections of Inferno, Purgatory and Paradise, but he became obsessed and couldn’t stop. Dore ended up making 135 illustrations and, in a panic, his publisher decided he no longer wanted to take a risk on publishing something so vast. So, Doré self-published the book. It sold out in a mere two weeks. His publisher then sent Doré the famous telegram that read: “Success! Come quickly! I am an ass!”

The illustrations are spell-binding and oddly uplifting, which is surprising given that they depict the nine circles of Hell.

This book was my constant companion in a time in which I was suffering from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. It’s just possible the sense of wonder within the imagery, had some curative effect.

Illustration from Gustave Dore’s 1861, edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy

The book as . . . rebellion. What is your favourite book that felt like it revealed a secret truth to you?

The True Believer – Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, by Eric Hoffer. First published in 1951, this is a brilliant study by a self-taught writer on what draws people to extremism. Hoffer has the courage to explore why people are drawn to totalitarian ideals, and some pretty devastating insights. Beware failed artists and idealists, he warns us. Beware of any group, whether political or religious, who claim that they have a single panacea solution to all of humankind’s problems; beware of people who are selflessly devoted to a cause – it is likely that they are motivated by resentment, there is a ‘venom and ruthlessness born of selflessness.’ As someone who came from three generations of fanatics, this book came as a necessary shock to my system; it convinced me to try to get rid of all the fanaticism and extremist thinking that was still lurking within me.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

If I can travel through space and time then I’d have to say it’s the labyrinth library at the centre of The Name of the Rose (1980) by Umberto Eco. It’s a page-turning murder mystery set in an Italian Benedictine monastery with the largest library in Christendom in the early 14th century. The labyrinth holds the key to the murders, which are all connected to one lost and forbidden book. I wouldn’t be so keen to go back to the era of the black death, the inquisition, heresies and witch hunts, as no doubt I’d be one of the ones burned at the stake, but I’d like to find my own way in that labyrinth library, with its many thousands of ancient books that have now vanished from history.

The film adaptation of Name of the Rose (1986). In the Labyrinth Library.

The book as. . .technology. What has been your favourite reading experience off the page?

I’m a terrible scribbler in the margins of all my books. In any book that I love you will find my scrawled handwriting every few pages or so, with asterisks, underlinings and arrows connecting passages. A real mess, and impossible for anyone else to read after me. I can’t do this in the same way with ebooks or PDFs, so I’m very much stuck ‘on the page’.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

I’m a compulsive re-reader, and my next novel will be about an ‘outsider’ character who is potentially dangerous, so I have a stack here of brilliant ‘outsider classics’ to re-read next. They are Hunger by Knut Hamsun, Notes from the Underground and Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky, The Trick is to Keep Breathing by Janice Galloway, Steppenwolf by Herman Hesse, The Mare and Veronica by Mary Gaitskill and of course The Outsider by Albert Camus. If anyone has any other Outsider suggestions, please get in touch with me on twitter: @mrewanmorrison

How to Survive Everything by Ewan Morrison is published by Saraband, priced £9.99.

Shrabani Basu is an author and a journalist whose latest book tells the fascinating story of how Arthur Conan Doyle became a detective and champion for justice in the campaign to pardon George Edalji, accused of mutilating horses in the English village of Great Wyrley. It’s an eye-opening look at race and an unexpected friendship in the early days of the twentieth century, and the perils of being foreign in a country built on empire. Here, in this extract, Shrabani Basu tells us of why she pursued this story.

Extract from The Mystery of the Parsee Lawyer

By Shrabani Basu

Published by Bloomsbury

I had always been fascinated by the case of George Edalji, and Arthur Conan Doyle’s involvement in it. I had read about George briefly in books about Asians in Britain, but always wanted to know more. I wanted to know how Shapurji arrived in Britain, what made him convert to Christianity and how he became the first Asian vicar of a small village in the coal-mining area of Staffordshire. As they were the only mixed-race family in the area, I wanted to know about the racism the Edaljis suffered and how it had all impacted on George’s trial. Conan Doyle had compared it to the Dreyfus affair, but unlike that famous case, captured in history and literature by Emile Zola’s letter titled ‘J’Accuse’, and the subject of books and films, few today have heard of the Edalji affair. The story of the Indian man targeted for his race and religion in England was soon buried and forgotten, just another casualty of Empire.

I often thought about the family at the vicarage even as I worked on another book set in Victorian Britain. 3 It was the true story of Queen Victoria and her Indian servant, Abdul Karim, who quickly became a firm favourite and caused a storm in the royal court. She gave him land and titles. He introduced her to curries and taught her Urdu. The lonely widowed queen lived the last years of her life in an Indian dream with the handsome turbaned youth by her side. It was more than the establishment could take. Victoria’s household and family closed ranks against Karim and conspired to defame him. Unable to destroy him while the Queen was alive, they swooped on him within hours of her funeral, and burnt all the letters that Victoria had written to him (often several in a single day). He was unceremoniously asked to return to India, and every attempt was made to erase him from history. Though their circumstances were completely different (Abdul worked in the royal palaces, and George lived in a mining village), and their personalities were a world apart, there was one parallel between George and Abdul. Both were victims of racism in a society that was ready to believe the worst of a foreigner.

At the time I was writing, Julian Barnes published Arthur & George , a fictional account of the Edalji story. It was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize and I felt there was no point in trying to write anything more on the subject. Yet, every time I watched a repeat of a Sherlock Holmes drama on television, I would think of George Edalji and Arthur Conan Doyle. There is nothing quite like the calling of an unsolved mystery, a dark crime set in the English countryside over a hundred years ago.

In 2015 a small article in The Times newspaper caught my attention. It said that a collection of letters written by Arthur Conan Doyle dealing with the George Edalji case were to be auctioned. These were letters written by Conan Doyle to Chief Constable G. A. Anson, head of the Staffordshire police. The correspondence had never been published. It was a sign. There was hope of new material. I called up Bonhams auctioneers to look at the letters and made my way to their offices in Kensington. As I held the letters written in Conan Doyle’s neat handwriting from Undershaw, his house in Surrey, and from hotels across Europe, I could feel the obsession he had had with the case. Here was Conan Doyle wearing the deerstalker of his fictional detective, trying to solve the only mystery that he ever investigated himself. It coincided with a period in his life when he was coping with grief and emotional turmoil. His wife, Louise, had passed away and he was going to marry the love of his life, Jean Leckie. There was guilt about having loved Jean for nine years while his wife was ill and dying. In a way, the case of George Edalji lifted Conan Doyle from his melancholy.

‘In 1906 my wife passed away after the long illness which she had borne with such exemplary patience,’ he wrote later. ‘… For some time after these days of darkness I was unable to settle to work, until the Edalji case came suddenly to turn my energies into an entirely unexpected channel.’

Conan Doyle threw himself into the investigation, travelling to Staffordshire to meet the Edaljis and revisit the scene of the crime. His correspondence with Anson was combative. The chief constable was scornful of the famous crime writer trying to do the work of the police. Conan Doyle was convinced that the police evidence had been shoddy and that Anson was a racist. Anson’s personal notes revealed his character. . . .

Within the boxes lay a story, not just of the trial of George Edalji and the investigation by Arthur Conan Doyle; it was a story that went back to when George was just a young schoolboy in Great Wyrley, targeted for being the son of an Indian. Page after page of hate-filled anonymous letters lay in the boxes, directed at the family in the vicarage.

*

The events of over a hundred years ago in Great Wyrley could have been taking place in the present. Miscarriages of justice in Britain have happened before – the Guildford Four, the Birmingham Six – to name a couple. Prejudice, doctored evidence and decisions made on circumstantial evidence have also occurred in the recent past. In 1998, the Macpherson Report into the murder of black teenager Stephen Lawrence revealed there was institutional racism in the police force. In 1903, George Edalji was virtually sentenced before he had even walked into the dock.

The Mystery of the Parsee Lawyer by Shrabani Basu is published by Bloomsbury, priced £20.00.

Donald S Murray shed light on the Iolaire disaster in his award-winning novel As the Women Lay Dreaming. David Robinson finds that Murray’s sense of place and its people is there once again in his new novel In a Veil of Mist and is just as beautifully drawn.

In a Veil of Mist

By Donald S Murray

Published by Saraband

Go to enough book festivals and there’s one question you’ll hear so often that it’s hard to stop your eyes rolling. ‘How important to your writing,’ the writer is asked, ‘is a sense of place?’ And the writer will nod furiously and say that yes, it’s so vital that it’s almost another character, when all they’ve really done is to sketch in a real-life location or scout Google Maps for a dash of background colour.

Donald S Murray’s new novel, In a Veil of Mist, set in his native Lewis as firmly as the stones at Callanish, is the opposite of this. Not only is the setting at least as important as the plot, but it is so credibly drawn that the book is almost a ticket to the island – and not only that, but to the Lewis of 1952 and to a secret it has largely kept to itself ever since. As I read the book, I found myself pondering the whole business of place. How do you actually go about creating such solidly believable settings for fiction? Can outsiders ever do it? Suppose they took precisely the same subject, what might they miss?

First of all, the background. It’s 1952, and a team of biological warfare specialists are conducting experiments on monkeys and guinea pigs on a converted tank landing ship off the north-east coast of Lewis. The Russians are streets ahead in testing killer gases, so this is us trying to catch up. Bomblets releasing the gases are exploded in the air a mile or so offshore, and the effects on animals placed on a pontoon underneath are studied. There are warning flags everywhere and nearby ships have been instructed to stay clear of the area. Yet word hasn’t reached the crew of an approaching trawler, or if it has, they’ve disregarded it. So on they sail, through the titular veil of mist, making their potentially deadly way through the Minch. Breathe in, and the crew could be inhaling brucellosis or tularaemia or seeding the bubonic plague in the populace the next time they step ashore.

For many novelists, one way of telling this story would be to go the full Tom Clancy, immersing themselves in military technology and Cold War politics and using every last detail of the real-life Operation Cauldron that forms the basis of this story. But this is the antithesis of Murray’s style: his award-winning debut novel As the Women Lay Dreaming was so powerful not because it retold the story of the Iolaire tragedy with extra descriptive adjectives – the actual 1919 shipwreck was hardly mentioned – but because it showed how grief pulsed through subsequent generations of islanders too.

Another approach – and one that tempts him more – is to place the germ warfare experiments at the centre of a moral dilemma. For this, he introduces a Liverpudlian lab technician aboard the converted tank carrier whose wife finds his work abhorrent and wants him to quit. But even though most novelists would probably also create such a character, and furnish him with the necessary self-justifying arguments, those are just as obvious as the details of Operation Cauldron itself. Sense of place requires far more – and perhaps as with his previous novel, it only emerges obliquely: you only find it when you’re not directly looking for it.

For me, this is what makes Murray’s two other main characters – Jessie, a spinster in her fifties, or Duncan, a bus driver in his late twenties – so important. These two find the bodies of the monkeys and guinea pigs washed up on the beach, the Tràigh Mhòr, near North Tolsta, although Jessie has never seen animals like them. They wonder about these mysterious washed-up bodies, and word spreads out – slowly – about the odd goings-on on the north-eastern tip of the island and the strange men in white boiler suits clearing the beach of debris. But they don’t ask direct questions about what they’ve witnessed. Whatever is happening, it is hardly the most important thing in either of their lives. For Jessie, that happened in 1923, when George, the only man she had ever loved, took the emigrants’ boat from Stornoway after promising her that one day they’d be together again. But that was almost 30 years ago and everyone on the islands knew that it would never happen, just like everyone knew that he had been unhinged by the death of his brother in the Iolaire, and everyone knew that George had probably killed himself somewhere, somehow, in the New World.

Everyone knew: again, Murray doesn’t tell us directly. We just see a friend praying, decades after that leave-taking, that Jessie be given the strength to accept the possibility of disappointment. We see her writing letters that she never sends to her lost love, in which she tells him how the people he knew back home are getting on, because that’s the key fact about island life: it would be remiss for an islander not to keep up to date. We see her remembering that 1923 leave-taking, when she’d never gone to the pier because if she had she wouldn’t have been able to stop the tears, and ‘that’s not the kind of thing you do if you come from Tolsta. We’re not like Stornoway folk, are we?’

So it builds up, this sense of place. Jessie will carry on her daily round, as lonely and self-contained as a bachelor hill farmer in a William Trevor story, searching the shore for carageen for dessert or seaweed to fertilise her potatoes, making her own cures rather than bothering the doctors, her mind teeming with tales from folklore. And Duncan will carry on driving his bus round the island, reading the papers at Stornoway library and telling the news from the wider world to his passengers, nodding at their own stories even though he’s heard them before, and all the time looking forward to meeting the woman he’s set his heart on at the Lido cafe.

We wouldn’t do that, you or I. We wouldn’t have him daydreaming about the future, wondering how he could possibly ask his girl to marry him, knowing it would mean sharing the house with his mother, just as we wouldn’t have Jessie living so immutably in the past. If we’d written this, we wouldn’t have left time drift so freely either forwards or back, but concentrated on the potential terrors of the here and now. We would have missed the wider stories about the island because we would have concentrated on fleshing out the thinner, secret one. In the process, we would have also missed out on this book’s extravagantly realised sense of place – which comes not just from description, but from Gaelic song, poetry, hymns, sermons, folklore, and prayer too.

Fortunately, we didn’t write this novel and Donald S Murray did. And in this time of lockdown, when we can’t change the background to our lives as readily as we would wish, when we can hardly travel anywhere and certainly not to north-east Lewis, it seems an even more impressive achievement than ever.

In a Veil of Mist by Donald S Murray, is published by Saraband, priced £9.99.

Ryan Vance’s collection of short stories, One Man’s Trash, offers fictional gems that are a little bit weird and wonderful, a little bit sensual and spiky, and a whole lot enticing and entertaining. Here, we share one of his stories, ‘Mouthfeel’, where a dreaded evening out becomes something else, something entirely unexpected.

One Man’s Trash

By Ryan Vance

Published by Lethe Press

Mouthfeel

Nathan located the restaurant on the corner of Kent Road and Berkeley Street: another hasty pop-up in the race to gentrify Finnieston, it bore no signage, no menu board. The only guarantee of a hot dinner was Lizzie, standing by a blank door in her favourite red polka dot dress. She waved at him across the street, and pointed to her watch. As Nathan waited for a gap in the traffic, a sharp sensation of chives appeared unbidden in his mouth—serving as an early warning of the Stilton, which arrived more blue than cheese. He slipped a bottle of mouthwash from his coat pocket, swilled a quick mouthful and spat into the gutter.

‘I saw that,’ Lizzie said as he approached. He kissed her on the cheek as a greeting. ‘Minty fresh, as always.’ She looked him over, touching her pearl earring to make sure he hadn’t dislodged it. ‘Oh Nate, trainers? What did I tell you about looking smart?’

‘This isn’t smart?’ he said, tucking his wrinkled shirt into his jeans.

‘Surprised you asked me along, to be honest. Not my sort of thing.’

‘I wasn’t about to show up to a tasting night solo, was I? Anyway, I’ve been worried about you. Man cannot live on Soylent alone.’

‘Actually,’ said Nathan, ‘I think that’s the point.’

‘Humour me, will you?’ She squeezed his shoulder. ‘Just for tonight, leave your curious condition at the door?’

This was Nathan’s condition: his mouth had forever been haunted by the ghosts of meals he hadn’t eaten. Foods he didn’t even like—liquorice, coffee, anything with strawberry flavouring—made frequent appearances, despite attempts to avoid them in person. Some flavours went through phases. A week of high-grade sushi. A month of hospital food, aggressively beige. His twenties had been characterised by the bubbled saltiness of caviar manifesting each Hogmanay, though it wasn’t until his thirtieth birthday Nathan got the chance to connect the taste to its real-world counterpart, at a restaurant not unlike this one. Other times, the phantom flavours interrupted meals he was already eating, muddying the entire experience. Christmas in particular was unpleasant, like sucking on a chocolate-covered stock cube.

He had a theory. His mouth, somehow, was connected to another. Telepathy of the tongue. He’d shared this theory once with Lizzie, who’d called him organic, free-range bonkers and refused to entertain the idea any further. Yet other sensations could not originate from food. A frequent probing warm wetness, for example, begun at sixteen, bloomed at night into a sticky, salty suddenness. He knew what that was. Unmistakable. Personally, Nathan preferred to spit, but to each their own.

Going down, stairs led to a basement, the decor sitting somewhere between a New York speakeasy and a half-finished public restroom. Typical for the area. A young man showed them to their table. Once seated, Nathan was hit by another imaginary wave of Stilton, this time accompanied by a light mouthfeel of something melting on his tongue.

Mouthwash was one of his coping methods, the intensity of peppermint enough to banish even the most stubborn spirits. The invention of Soylent—a lab-brewed dust-flavoured meal-in-a-sachet— had been something of a blessing, as it cut out all interference. But as their waitress provided a small wooden board laid with four canapes: blue stilton and chives on a buttermilk wafer, Nathan realised, there would be no interference tonight.

By the bar, a wine glass and teaspoon commanded attention. A large man in a three piece suit beamed at his guests, paired with a round-shouldered chef, her height almost matching his, if you included her toque. Together they delivered some guff about pushing boundaries and contributing to the neighbourhood’s legacy for experimental dining. Nathan didn’t hear a word. He was too dumbfounded by the serendipity of canapes.

‘He’s here,’ breathed Nathan.

‘Who?’

‘My other taster.’

‘I don’t want to talk about it, Nathan. Look, here comes our food.’

Matched with a slim glass of Chardonnay boasting notes of pineapple over buttered toast, the first course was a bisque of langoustine with white chocolate and garlic. Nathan pushed it around with his spoon.

‘They know what they’re doing,’ said Lizzie. Nathan pinched his nose in preparation. Lizzie reached across the table and slapped his hand. ‘Stop embarassing me. Just try it. Please.’

So he did. The crustacean wash gave way to a sweet cream on the way down, at once seaside and farmyard, sending his brain into a strange pinching pleasure.

‘See?’ Lizzie said, as his eyes grew wide. ‘You’re missing out.’

The sensation of hot, smooth bisque filled Nathan’s mouth again. Not an after-taste. First contact, twice. Then came the wine. At least, he assumed it was the wine, though his palate wasn’t refined enough to identify anything as exact as pineapple. But he’d not touched his Chardonnay, the fine glass as yet unsmudged by fingerprints.

As they ate and chatted about their days, he couldn’t shake the feeling that someone he’d never been sure existed, but had known intimately throughout his life, was now here with them, hidden among strangers.

‘Recognise anyone?’ he asked Lizzie.

‘Oh, the usual crowd. Press and foodies.’ She looked at him with a sigh. ‘Can’t we play Guess Who later? I’m right here, Nate. I haven’t seen you in months. Since you started on that liquid goop you don’t eat like normal people.’

‘You’ve got it the wrong way round. I don’t eat like normal people, that’s why I’m on that liquid goop in the first place—you know that.’

Their second course arrived. The venison haunch was obvious enough, sitting medium-rare at one end of the bamboo board, but the sweet potato puree, caramelised chestnuts, gingerbread crumble and spiced roast plum were abstracted in dots and blobs, closer to modern art than food. Nathan hovered his fork first over one element, then the other, unsure of where to start. Lizzie rolled her eyes. As they ate, Nathan peered at the other diners. Was anyone shocked when he took a fluffy mouthful of crumble, or a rich cut of venison? Every flavour on the board blended with its neighbours. The puree gifted the plum a constancy of texture, its sweetness taking centre-stage when paired with the woody chestnuts. The crumble stole the venison’s juice, the plums returned the moistness. Nathan found if he alternated medleyed mouthfuls with his invisible dining companion, he could create a constant, shifting gradient of tastes and textures, as if he’d bitten out a chunk out of the Northern Lights.

‘I have to meet them,’ he said, half-standing to look around the dim-lit restaurant. Was there a flicker of interest from the thin, eagle-faced man alone in the corner by the door? Or the two elderly women sitting near the bar? What about the table of young party animals whose shiny helium birthday balloon bobbed against the ceiling? Did any of them seem curious?

‘Good grief.’ Lizzie downed her wine. ‘You should’ve stood me up, at least then I’d get double portions.’

Nathan slumped back into his seat. Double portions. Triple portions. Centuple portions. His telepathic tongue could be linked to every mouth in the room and he’d never know Eve from Adam, all of them eating the same apple.

Unless he went off-menu.

‘Don’t judge, okay?’ He lifted Lizzie’s empty wine glass. ‘This is a test.’

‘This whole night is a fucking test, if you ask me.’

Under the table, Nathan took his bottle of mouthwash and sloshed some into the glass. The chemical scent was alarming, out of place.

‘Nate. I told you, put it away.’

He tipped the whole lot into his mouth—

‘Nathan!’

—and held it there. Two round cheekfuls of dental cleaning fluid. Their waitress approached, concerned. ‘Sir, are you okay?’

Nathan nodded, and tried to smile without dribbling. Lizzie, less courteous, waved the waitress away, mortified. His eyes watered, his sinuses flamed, the menthol tingle flayed his taste buds in waves. But he didn’t desist.

‘Augh!’

The eagle-faced man in the corner leapt to his feet, knocking his chair to the wooden floor. He pushed his way to the bathroom, a hand over his mouth. Nathan spat the mouthwash back into Lizzie’s glass and took a strong gulp of white wine from his own. Under the soothing grape twisted sour by the mint, he felt tap water bubbling against the back of his throat, a cleansing gargle.

‘Give me that.’ Lizzie snatched her glass away and marched to the ladies’ room, returning to the table empty-handed. Nathan began to apologise, but stopped. Lizzie was looking at him funny.

‘That’s Eugene Richmond,’ she said. ‘You know Margot Richmond? Three Star Michelin Matriarch of Paris? I guess not. Rumour has it, she’s written him out of her will. He’s incompetent, she’s tried to teach him everything she knows, but it just won’t stick. She doesn’t want him near her empire. So of course he became a critic. But he couldn’t even get that right. His reviews were unusual, sometimes perfect but sometimes flat out wrong. Nobody took him seriously until…’ Lizzie leaned back in her chair and covered her mouth. ‘When did you start using Soylent?’

‘About two years ago? Two and a half?’

‘And it tastes of…?’

‘Nothing, really.’

‘Aye. That’s when Eugene got his book deal. Everyone assumed he’d hired a ghost-writer.’

Chatter rose around them as Eugene Richmond exited the men’s room and began collecting his belongings.

‘Don’t just sit there,’ hissed Lizzie. ‘Go talk to him! Butter him up! Get us an invitation to his mum’s flagship!’

She didn’t have to tell Nathan twice. He dodged his way to the stairwell through a flurry of servers carrying plates of star fruit coconut cheesecake, its layers de-constructed into poetry. He brushed past the doorman. Eugene was almost out on the street, almost gone.

Words came to Nathan in a rush:

‘What do you taste like?’

Eugene Richmond paused on the top stair, facing out into the night, one step from disconnection.

‘Excuse me?’

‘That came out wrong. I mean…’

Nathan wondered if at this moment Eugene’s mouth was also dry.

‘What is taste like, for you?’

Nathan tasted vomit. Eugene braced himself against the door frame.

‘It’s you, isn’t it?’

One hallucinogenic dessert later, the kitchen was closed, but Eugene had bribed the round-shouldered chef to knock up a feast of small plates, promising his first ever five-star review. Lizzie stayed behind also, to make amends to the staff with some very expensive champagne, which she had for no good reason started calling ‘bubbly’, something she’d never done before.

Over this private banquet, Eugene and Nathan came to understand some of their more unusual, unexplained experiences. A soggy scuttling sensation in Eugene’s childhood, the memory of which gave him nightmares to this day, had come from when Nathan, under a dare, had placed a beetle inside his mouth, panicked, and bit down. Meanwhile, a year of burnt pepperoni had, in fact, been the taste of Eugene’s chainsmoking ex-boyfriend, kissing.

‘Allow me to try something?’ said Eugene. He was quite handsome when he smiled, the severity of his birdlike nose softened by a lopsided pair of dimples. ‘Close your eyes.’

Nathan did so, and felt a cool lightness on his tongue, a woodsy caramel flavour that melted down the sides, tart and savoury and sweet at once.

‘Parsnip?’ Nathan guessed. ‘But charred and runny. The frothy stuff.’

‘The mousse, exactement!’

When Nathan opened his eyes, Eugene had lifted his glass of champagne, and motioned for Nathan to do the same. They both sipped, then smiled. It was impossible to tell where one man’s experience came to a close, and the other began anew.

‘Not once did I ever enjoy a meal the way I knew I was meant to,’ said Eugene, ‘Until tonight. It feels less… lonely, no?’

Decades running parallel to each other, but connected, two paths meeting in an impossible space. Now here they were, feeling altogether more-ish, umami for the soul. Nathan laughed. Eugene was right.

Exactement.

He scooped up the last remaining mouthful of cheesecake, and shared it with him.

One Man’s Trash by Ryan Vance is published by Lethe Press, priced £12.00.

Glasgow is no stranger to fictional detectives, but we are particularly excited about the latest addition to the gang. We know you’re going to love DI Jimmy Dreghorn and his sergeant Archie McDaid and their criminal investigations in 1930s Glasgow. We spoke to author Robbie Morrison to find out more about his debut novel, Edge of the Grave.

Edge of the Grave

By Robbie Morrison

Published Pan Macmillan

Congratulations Robbie on the publication of your first novel, Edge of the Grave. Could you tell our readers what to expect?

Thanks. Edge of the Grave is the first book in a new historical crime series set in 1930s Glasgow, which Peter James has described as ‘a mesmerizing debut,’ and Mark Billingham as a ‘magnificent and enthralling portrait of a dark and dangerous city and the men and women who live and die in it, chilling and brutal, but also deeply moving.’ Far be it from me to argue with them!

It’s a gritty story that takes Detective Inspector Jimmy Dreghorn and his sergeant ‘Bonnie’ Archie McDaid from the flying fists and slashing blades of Glasgow’s gangland underworld to the backstabbing upper echelons of government and big business in the hunt for a twisted killer. Beyond the first book, the series will focus on the lives, loves and investigations of Dreghorn and McDaid, in what is planned to be a sweeping mix of crime thriller and family saga.

You’re an experienced writer of graphic novels. How did you bring your previous writing experiences to Edge of the Grave?

Well, it’s always good to challenge yourself and try something different but writing a crime novel is actually something I’ve wanted to do for longer than I’ve been writing comics and graphic novels. As much I like comics as a medium for storytelling, crime fiction has always been my real passion.

Obviously, there are more words – LOTS more words – in a novel. In comics, you have the artwork to help generate mood, but when you’re writing a comics script – even though the style of writing might be more conversational – you’re still intent on firing the artist’s imagination with your descriptions of place, character and action. That hopefully inspires them to bring something of themselves to the story.

When writing a novel, you’re also aiming to get readers’ imaginations working, so that they visualise characters, places, etc, and become immersed in the story. As a writer, the reader’s imagination is one of the most powerful tools you have. If you can spark that, then you can go anywhere.

While I’d say the writing in a novel has to be tighter in some ways, the basic principles of good storytelling are exactly the same. When the reader of a novel reaches the end of a chapter, you want them to immediately turn the page because they’re so engrossed they can’t stop themselves – just like a comics reader reaching the cliff-hanger end of an episode and being desperate to buy the following issue to find out what happens next. The mediums might be different, but it’s all about telling a good story ultimately.

You open the novel with a quote from William McIllvanney. How have you been influenced by Glasgow crime writers who have come before you?

The work of the late William McIlvanney, a writer capable of achieving greater insight in a single sentence than most of us could in an entire novel is probably the biggest influence – especially the Docherty and the Laidlaw novels. In fact, the title derives from one of those sentences in The Papers of Tony Veitch: ‘It was as if Glasgow couldn’t shut the wryness of its mouth even at the edge of the grave.’