2021 looks to be another year of fantastic releases from the wonderful Charco Press. Their first publication of the year, Havana Year Zero follows Julia and her former lover Euclid as they set out to prove that the telephone was invented by Antonio Meucci in Havana, convinced it is will turn both their lives around and give Cuba a purpose once more. We hope you enjoy this opening extract.

Extract taken from Havana Year Zero

By Karla Suárez

Published by Charco Press

It all happened in 1993, year zero in Cuba. The year of interminable power cuts, when bicycles filled the streets of Havana and the shops were empty. There was nothing of anything. Zero transport. Zero meat. Zero hope. I was thirty and had thousands of problems. That’s why I got involved, although in the beginning I didn’t even suspect that for the others things had started much earlier, in April 1989, when the newspaper Granma published an article about an Italian man called Antonio Meucci under the headline ‘The Telephone Was Invented in Cuba’. That story had gradually faded from most people’s minds; they, however, had cut out the piece and kept it. I didn’t read it at the time, which is why, in 1993, I knew nothing of the whole affair until I somehow became one of them. It was inevitable. I’m a mathematician; method and logical reasoning are part and parcel of my profession. I know that certain phenomena can only manifest themselves when a given number of factors come into play, and we were so fucked in 1993 that we were converging on a single point. We were variables in the same equation. An equation that wouldn’t be solved for many years, without our help, naturally.

For me, it all began in a friend’s apartment. Let’s call him… Euclid. Yes, if it’s all right with you, I’d prefer not to use the real names of the people involved. I don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings. So Euclid is the first variable in that damned equation.

When we reached his place in the afternoon, his mom greeted us with the news that the pump had broken down again and we’d have to fill the storage drums using buckets of water. My friend scowled, I offered to help. So that’s what we were doing when I recalled a conversation that had taken place during a dinner a few days before, and I asked him if he’d ever heard of someone called Meucci. Euclid put down his bucket, looked at me and asked if I meant Antonio Meucci. Yes, of course he knew the name. He grabbed my bucket, poured the water into the drum and informed his mother that he was tired and would finish the task later. She protested, but Euclid turned a deaf ear. He took my arm, led me to his room, switched on the radio – his usual practice when he didn’t want to be overheard – and tuned in to CMBF, the classical music station. Then he asked for the full story. I told him what little I knew, and added that it had all started because the author was writing a book about Meucci. An author? What author? he asked gravely, and that irritated me because I didn’t see the need for so many questions. Euclid got to his feet, went over to the wardrobe and returned with a folder. He sat down next to me on the bed and said: I’ve been interested in this story for years.

And then he began to explain. I learned that Antonio Meucci was an Italian, born in Florence in the nineteenth century, who had sailed to Havana in 1835 to work as the chief engineer in the Teatro Tacón, the largest and most beautiful theatre in the Americas at the time. Meucci was a scientist with a passion for invention who, among other things, had become interested in the study of electrical phenomena – it was known as galvanism in those days – and their application in a variety of fields, particularly medicine. He’d already invented a number of devices and was in the middle of one of his experiments in electrotherapy when he claimed to have heard the voice of another person through an apparatus he’d created. That’s the telephone, right? Transmitting a voice by means of electricity.

Well, he took this thing he called the ‘talking telegraph’ to New York, where he continued to perfect his invention. Some time later he managed to get a kind of provisional patent that had to be renewed annually. But Meucci had no money, he was flat broke, so the years passed and one fine day in 1876 Alexander Graham Bell, who did have cash, turned up to register the full patent for the telephone. In the end it was Bell who went down in the history books as the great inventor, and Meucci died in poverty, his name forgotten everywhere except in his native land, where his work was always recognised.

But they lie, the history books lie, said Euclid, opening the folder to show me its contents. There was a photocopy of an article, published in 1941 by the Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz, which mentioned Meucci and the possibility that the telephone had been invented in Havana. In addition, there were several sheets of paper covered in notes, a few old articles from Bohemia and Juventud Rebelde, plus a copy of Granma from 1989 with that article I just mentioned.

I was fascinated. In spite of the fact that, so long after the events recounted in the documents, I was still unable to enjoy the advantages of a functioning telephone at home, I felt proud just knowing that there was a remote possibility that it had been invented in Cuba. Incredible, right? The telephone, invented in this city where telephones hardly ever work! It’s as if someone had come up with the idea of the electric light, satellite dishes or the Internet here. The ironies of science and circumstance. A dirty trick, like the one played on Meucci, who, over a century after his death, was still a forgotten figure because no one had managed to prove that his invention had preceded Bell’s.

A dreadful historical injustice, or something like that, was what I exclaimed the moment Euclid finished his exposition. That was when I learned the other thing. Euclid rose, stepped back a few paces, looked me in the eyes and said: Yes, an injustice, but one that can be righted. I didn’t understand. He sat down again, clasped my hands and, lowering his voice, added: What can’t be demonstrated doesn’t exist, but the proof of Meucci’s precedence and, ergo, its demonstration, does exist, and I know because I’ve seen it. I can’t even imagine the expression on my face; I only remember that I made no reply. He freed my hands, never taking his eyes from mine. I guess he was expecting a different reaction, waiting for me to jump up, perhaps, cry out in surprise or something, but my only feeling was curiosity, and that’s why, in the end, I simply asked: The proof?

Havana Year Zero by Karla Suárez is published by Charco Press, priced £9.99.

Each year the Association for Scottish Literary Studies publishes their New Writing Scotland anthology. Here, we share two poems from the anthology, which includes work from from forty authors – some award-winning and internationally renowned, and some just beginning their careers.

Poems taken from The Last Good Year: New Writing Scotland 38

Edited by Rachelle Atalla, Samuel Tongue and Maggie Rabatski

Published by the ASLS

GARDENER

Susan Mansfield

That’s how I see my father, looking back,

always stooped with a spade in his hand

slicing square sections from the rich, dark earth,

the rhythm of it, the heft of each cut,

leaving it furrowed and fresh, full of promise,

the mica gleam of it, ready for growing,

ready for roots. For the magic of growing

happens deep down where the land gives back

the lifeblood to the seedling, promising

fragile new things which need tended by hand,

and some will wither, such is the cut

and thrust, the mixed blessings of the earth.

My father claimed as his this patch of earth,

set aside plenty of ground for growing,

how he paced it out, how the sod was cut

without ceremony, how he bent his back

to building a home with his own hands,

with enough room in case the promise

in her eyes became more than a promise

and tending his seedlings in the dark earth

was just the beginning. How one small hand

changes all you know about growing,

the unflinching force of it, no looking back,

eyes on the wide horizon ready to cut

and run, but all so soon, the toughest cut

for man or gardener, seeing a promise

fulfilled by leaving you, then going back

to lay down next year’s crop in the mulched earth

and wait for the consolation of growing

while the furrows deepen on your gnarled hands.

I wasn’t even there to take his hand

at the last, which is the strangest cut,

holding the phone in the half-light, the growing

sense that the things we think are promises

are only good intentions, and the earth

receives everything but gives nothing back.

Now, the weeds grow thicker and in my hand

no spade to cut them. I made no promises,

feeling the turn of the earth at my back.

BLAST ZONE

Lotte Mitchell Reford

I want to write about meaningful things

but everything coming out is about fucking

or sometimes about churches. Often about how

I’m worried about drinking myself stupid

or to death. There is a story I’ve been wanting to tell

about the time I broke my leg and the morphine barely

worked,

how a man who loved me held my calf for an hour and felt

the split bones

pressing into his palms, and also a scene stuck bouncing

round my brain,

something I heard in an interview on NPR about nuclear

tests

in the ’50s and how they made young men bear witness to

the devastation

and gave them questionnaires afterwards to gauge its effect

on their mental health. Was it like a psychiatric intake form?

‘In the last week, on a scale of 1–7, how often have you

thought

about death’ – this one is always a 7 – or more like the

pain charts

they give you in an ambulance. Those ones have faces

to represent 0, 1–3, 4–6, 7–10. The only time I have pointed

at one of those little faces I had to ask what I was comparing

my current pain to. I’ve never felt anything worse than this

I said, my left tibia and fibula smashed into several pieces,

But someone must hurt more? Like, where are those men

now,

who after they watched the blast from a trench at a distance,

walked out in a line,

a search party, and combed the desert for what was left.

Those bombs are used now to measure everything

temporally. There is a before and an after; for bones, for

wine.

And in the middle of that hard dark line across time

were animals penned in the blast zone. The furthest out

lost limbs

and survived a while. Most of the animals were pigs

because pigs die like humans, and the guy I heard

on NPR, he said the worst part was how delicious

the whole desert smelled, a giant barbecue,

and that as they are dying like humans, pigs scream like

us too,

and yet, still, he thought of food. While we waited

for the ambulance Thom and I talked about pizza to

distract me,

pretending I’d be home in time for dinner.

In the hospital they pulled on my foot to reset the bones

above.

They told me not to worry because pain

is something we never really remember and anyway

I’d had all the morphine they could give me. I didn’t want

to point out

there are many kinds of pain, and some are hard to forget

some remain etched into you, your body and bones

or become a new kind of glass, Trinitite, superheated sand

which registers as radioactive. I didn’t want to tell them

that I had a hefty tolerance for opioids.

I never want to tell people who fix bodies

about the things I do to mine. Most of those men,

young as they were, must be dead now. Our bones hold

the nuclear tests in New Mexico, and so do wine cellars,

trees

and soil, but how do we hold those boys

with us too, how do we keep bearing witness,

how do we remember to remember?

The Last Good Year: New Writing Scotland 38, edited by Rachelle Atalla, Samuel Tongue and Maggie Rabatski is published by the ASLS, priced £9.95.

Thanks to Leela Soma, there’s a new detective in town: Glasgow’s DI Alok Patel. Cauvery Madhaven finds this new detective a welcome addition to Scotland’s fictional crime fighting cohort.

Murder at the Mela

By Leela Soma

Published by Ringwood Publishing

The word mela originates in Sanskrit means a gathering or assembly of people. Since its conception in 1990, the Glasgow Mela has taken this many steps further, evolving into an outdoor multicultural spectacular, one of the largest in the country. The Mela instantly conjures up images of music, dance, arts and food from Glasgow’s varied communities, celebrating their shared diversity.

Into this heady mix, Leela Soma throws in a murder at the mela. A young Asian woman, Nadia, is found dead on the closing night of the famous event, in Kelvingrove Park. Detective Inspector Alok Patel is not just newly appointed, but is also Glasgow’s first Asian DI. A rising star in the force, he is now under pressure to solve this murder quickly. Was the homicide a crime of passion, or was it racially motivated? There is talk of it being an honour killing. There are multiple suspects and very little to go on.

The investigation begins to uproot the barely buried tensions within Glasgow’s Asian communities and Patel must navigate all of it while coping with the professional jealousy of an overtly racist colleague. Adding to his problems is a deception of his own making – DI Patel is in a relationship with his colleague, Usma, a Muslim policewoman and all evidence must be kept from his disapproving Hindu parents.

Yes, Leela Soma’s third novel is a welcome addition to Tartan Noir. However, this book is far more than a police procedural crime novel. Sitting in the passenger seat of the police car alongside Patel, you get to read the very heart and soul of what divides and unites the Asian community in Scotland: the Hindu-Muslim rift that goes back decades, its roots in the partition of the subcontinent, the anxiety in the Muslim community about their young people getting radicalised, the personal angst of those drawn to strict religious tenets having to square up with what a youthful modern society has to offer. Soma’s characters, including the murder victim, confront the challenge of being Scot Asian today, charting their own destinies while trying to conform – to parental expectations and dreams, to norms laid down by gossiping aunties and interfering uncles. Soma is skillful in her revelations, carefully drawing back the many veils that shroud family life and religious pride and prejudice, so that her characters are utterly believable.

Soma moved from India to Glasgow in 1969. She was a Principal Teacher in Modern Studies and has made a name for herself as an award-winning poet and novelist, appointed Scriever 2021 for the Federation of Writers Scotland. Soma’s teacher’s touch is evident in her meticulous research of police procedures which keeps the investigative narrative moving briskly. DI Patel’s unit reflects life itself – police officers are no different from the citizens they are meant to keep safe – bitter, self-pitying DS Alan Brown, DI Joe grieving his young wife Lucy and Usma trying to reorganise her career so so she can ‘settle down’.

Soma’s love for Glasgow really shines through, her dual Indo-Scot heritage giving her a unique perspective into the lives of the Asian Scot community, as well as the urgent social issues that face Glaswegians of every colour. Interspersed with this well plotted whodunnit is a very truthful account of poverty in the post-war social housing schemes. Poverty that spawned Big Mo and Gazza in Drumchapel, who have no chance of escaping the ‘living aff the burro, man lifestyle’ and who are portrayed with the same wonderful compassion with which Soma details the life and loves of Hanif, a young medical student teetering on the precipice of being radicalised.

There are several suspects and Soma keeps the reader guessing – and when a second murder takes place DI Patel is give a rollicking by his superior. And with the uncanny bad timing that desi mothers are wont to have, DI Patel’s mother gives him a earful too – Usma, being Muslim, has to go!

Soma’s Murder at the Mela is a breakthrough book – the first Tartan Noir with an Asian DI, written in a very cinematic style with made-for-TV characters and a cliffhanger of a twist at the end – perfect for a season finale! Watch the listings as DI Patel is here to stay.

Murder at the Mela by Leela Soma is published by Ringwood Publishing, priced £8.99.

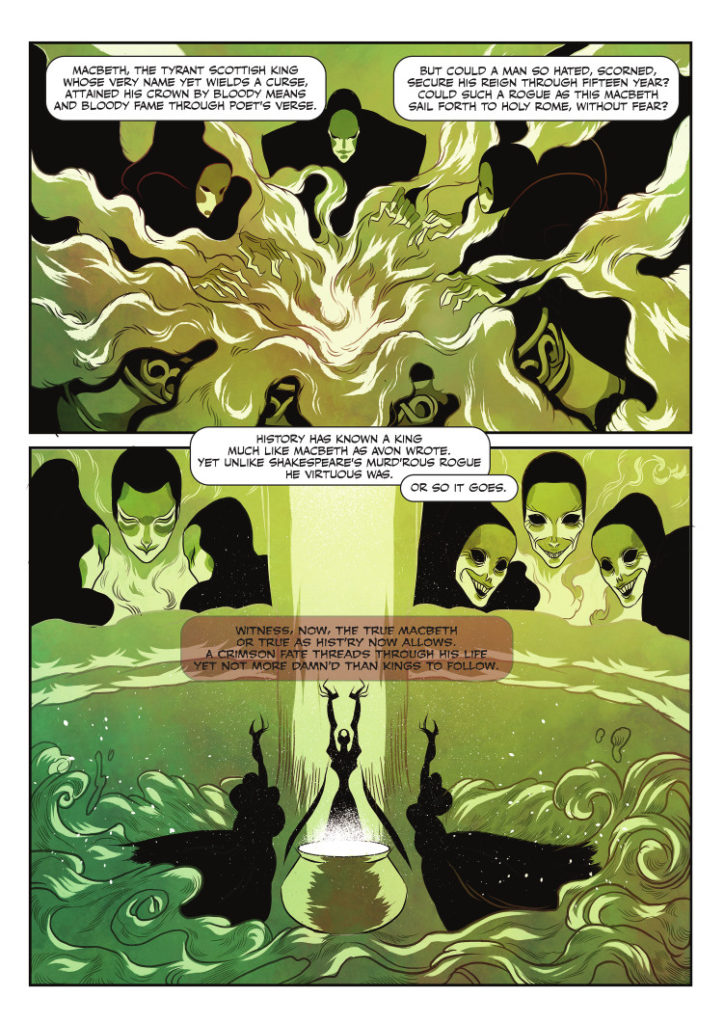

‘The Scottish Play’, one of Shakespeare’s most famous works. Though the play might have played a little with history, writer Shaun Manning and illustrator Anna Wieszczyk have decided to go back to historical sources for their graphic novel to tell us the real story of the Scottish monarch. Here we share some of the amazing storytelling and artwork to be found in Macbeth: The Red King.

Macbeth: The Red King

By Shaun Manning and Anna Wieszczyk

Published by Blue Fox Publishing

Macbeth: The Red King by Shaun Manning and Anna Wieszczyk is published by Blue Fox Publishing, priced £12.99.

Duck Feet, Ely Percy’s second novel, follows 12-year-old Kirsty Campbell as she and her friends go through high school together. Taking in teen rites of passage as well as the troubles of bullying, drugs and pregnancy, each chapter is told with poignancy and humour. In this extract, Kirsty contemplates the pitfalls of teenage fashion.

Extract taken from Duck Feet

By Ely Percy

Published by Monstrous Regiment

Nearly evrubdy in school wears stuff that says Tregijo. Yi can even get school shirts that’ve got it writ on them. This boy in ma class cawd David Donald, his family are pure poor cause thiv got aboot ten million weans, he come in wan day wi a Tregijo shirt an he got the slaggin ae his life. Ah didnae even notice anythin cause ah thought it looked identical tae evrubdy else’s but Charlene said, Naw yi can well tell that’s a fake, she said, Cause the stitchin on the cuffs is different.

Charlene wants tae get a pair ae Tregijo jeans as well as a top noo. Ah said, Ah didnae even know yi could get Tregijo jeans. Charlene said, Where’ve you been planet Uranus, an then she sniggert. Ah tolt her ah didnae get it an she jist said, Never mind, then she said, Ah take it ah’ll need tae gie you lessons oan how tae huv a sense ae humour as well as fashion.

*

Ma ma went an knittet me an Arran jumper tae wear ower ma school shirt. Ah said, Ah cannae wear that. How no, ma ma said, Yiv wore Arran jumpers tae school before. Ah says, Aye when ah wis aboot eight-yir-auld or somethin. Ma ma’s face wis pure trippin her. Actually the last Arran jumper yi had ah knittet a year past in October, she said, If yi remember right aw the wans in yir class wur jealous an ah endet up daein aboot six ae the bliddy things fur other folk.

Ah wantet tae say tae her that that wis primary school; that naebdy in high school wore an Arran jumper, no even David Donald an he wis the pure reject ae the class. Ma ma said when she wis at high school she’d tae wear hand me doons fae her big sister an she didnae go cribbin aboot it. She said, Ah remember bein no much aulder than you Kirsty, she said, An The Who had jist split up an fur months afterwards ah wis made tae wear yir Auntie Jackie’s auld denim jacket wi their logo on it.

Your ma musta been a pure reject anaw, said Charlene. This wis cause ah tolt her aboot The Who jacket. Ah wish ah hadnae tolt her noo but she kept askin me when ah wis gaun intae Glasgow an whit jumper did ah think ah wis gaunnae get. She kept on an on an on at me an ah had tae tell her somethin; ah never thought she’d hit me wi a comment lik that though.

*

Ma ma used tae be a sewin machinist. She used tae work in a factory that made aw the clothes fur Marks an Sparks. See aw yir Tregijo jumpers an yir shirts, she said, Thir no worth a chew. Widyi mean, ah said. She said, Thir no worth the money hen. She said, Ah’ve looked at some ae the stuff an the hems are aw squint an everythin an thiv jist been papt oot intae the shops an naebdy’s botherin as long’s it’s got a designer label on it thir’s folk that’ll buy it. Dae yi never think aboot gaun back tae it, ah asked her. Back tae whit, she said. Sewin machinin. Ma ma jist sighed. Wid yi no go back tae it then. Ah gave it up tae huv you an Karen, she said. Aye ah know. Don’t get me wrang it wis a great environment ah loved ma job, she said, But that wis thirteen year ago an it’s aw changed. Aye but yi could still go back. Aye Kirsty, she said, Ah can jist see it noo … ma designer Arran cardigans wid be aw the rage.

*

Ma ma gave me the thirty pound fur gaun intae Glasgow wi Charlene. Ah felt dead excitet cause ah’d only ever walked past Trendy Tribe, but then ah also felt bad cause ma ma an da had a big argument cause ma da jist got made redundant fae his work, an he says we cannae afford tae be spendin money willy nilly.

Charlene’s ma’s boyfriend disnae work either but he’s never oot the pub an he’s always wearin the best ae gear. Charlene’s ma works IN the pub an she’s whit ma da calls aw fur coat an nae knickers, an she gies Charlene thirty pound a week jist tae gie her peace. An they wonder how that wee lassie’s the way she is, said ma ma. Aye, ma da said, Ah’d rather dress lik a tramp than live the way that they live.

*

Ah wisnae that keen on Trendy Tribe. Ah thought thir sizes wur dead weird, an the folk that wur servin kept comin up an sayin, Can ah help yi dae yi need a hand can ah get yi anythin else there. Ah couldnae even get peace tae look but they wur up ma back every two minutes.

Charlene must’ve tried on every jumper in the shop in every different colour. She took that long in the changin rooms that ah actually shoutet through tae her, You better no be knockin anythin, an that soon made her move. She spent seventy two pound aw in: she bought a jumper that said

TREGIJO + PARTNER

that had a picture ae a cowboy haudin a smokin gun. She also got her jeans that she wis wantin, an a belt tae haud them up cause the smallest size wis too big fur her.

Ah endet up jist gettin a plain white T-shirt that had a T on the sleeve; it only cost fifteen pound an the lassie in the shop wis gaunnae gie me a twenty percent reduction because it had a black mark on it. Ah said tae her ah’d jist leave it though cause ah wisnae sure if it’d come aff, so she had tae go an get me another new t-shirt the same. Charlene wis pure hummin an hawin cause she said it wis takin ages an she wantet tae go fur somethin tae eat. Then she said, Is that it is that aw yir buyin, an when ah said Aye she said, Kirsty that’s pure miserable.

*

Charlene’s in a bad mood. She managed tae lose her purse wi twenty eight pound in it in the toilets in McDonalds, an by the time we realised an went back sumdy wis away wi it. Her return ticket wis in it anaw so ah had tae pay her bus fare back up the road.

When ah got in the hoose ah opent the carrier bag tae show ma ma whit ah’d bought an ah noticed the lassie had gied me a black Tregijo T-shirt by accident; then ah noticed that the white wan ah’d picked wis in there anaw. Sake, ah said, Ah’ll need tae go aw the way back intae Glasgow tae take it back noo. Don’t be daft, said ma ma, Sumdy’d need tae go wi yi an wur no wastin aw that money on bus fares. But it’s stealin is it no. Naw, said ma da. It’s whit yi caw an error in your favour – Anyway, it’s bad luck tae look a gift horse in the mooth. This is true, said ma ma. Ah wisnae convinced, but ah let it go cause ma ma did huv a point aboot the bus fares cause it widda cost another seven pound fifty an that’s only if we got a child an an adult day ticket.

Ma da had his ain good fortune the day. He’d applied fur a job packin balls a wool in a warehouse ower in Hillington an he got asked tae go fur an interview. Ah’ve got a right good feelin aboot this, he said. Me tae, said ma ma, An if yi get it they might gie yi some freebies.

Duck Feet by Ely Percy is published by Monstrous Regiment, priced £8.99.

David Bishop has just released his debut novel, City of Vengeance, introducing us to a new investigator, Cesare Aldo, in the sensational and dangerous underbelly of Renaissance Florence. We spoke to David about his book, and his favourite historical fiction.

City of Vengeance

By D. V Bishop

Published by Pan Macmillan

Congratulations David on the publication of City of Vengeance! It’s been quite the journey getting your book into print, but an encouraging one too for budding writers. Could you tell us more about your road to publication?

City of Vengeance was inspired by an academic monograph I chanced upon in a bookshop near the British Museum, which argued the criminal justice system in late Renaissance Florence was roughly similar to a modern police force. That set off a big lightbulb in my head, but I spent years researching and not writing the novel. The more I learned about the period, the more I realised how little I knew. I wanted to do the story justice, so I did other things instead – writing episodes of Doctors for BBC 1, audio dramas featuring Doctor Who, graphic novels and award-winning short film scripts that never quite got made.

To force myself into writing the novel, I started a Creative Writing PhD part-time via distance learning at Lancaster University in 2017. That gave me deadlines and a supervisor to offer feedback. The following year I entered the Pitch Perfect competition at the Bloody Scotland international crime fiction festival at Stirling. To my surprise I won, which galvanised me to hurry up and finish my first draft. More drafts followed and in Spring 2019 I started querying agents. Happily the wonderful Jenny Brown offered to represent me, and the book went on submission to publishers. Several made offers, but I chose Pan Macmillan – the home of Colin Dexter, Ann Cleeves, Ian Fleming, Lin Anderson and many others.

With historical fiction, a writer has to undertake a lot of research to bring authenticity to the world you’re creating. Did you enjoy this process?

Yes, too much at times. Research is utterly addictive because you discover so many fascinating things you never knew, facts that challenge your perception of history. My biggest problem is knowing when to stop researching and start writing, because it’s such a useful work displacement activity. My book shelves are groaning beneath the weight of books I have read, and those still waiting for my attention.

Your book is set in 16th century Florence. Did you already have a relationship to the city?

I grew up in New Zealand but had always wanted to see Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance. My first visit was in 2001, and I return every few years. Now I’m writing about the city, I have even more reason to go back – once the pandemic is over.

Your novel is a thriller as well as historical fiction. When writing, how did you strike the balance between your world-building and your pacy plotting?

My writing naturally tends toward pace, thanks to a background in journalism where lean writing is essential and a career in comics, where concision is crucial. I have to make a conscious effort to describe environments and characters, perhaps because I tend to send the story as a film playing in my head. I have to remember the readers can’t see what a tavern or a convent or a stabbing looks like unless I write it down.

You have quite the protagonist in your investigator Cesare Aldo. Can you tell us about his creation?

The fact I spent so long not writing City of Vengeance was to Aldo’s advantage. Instead of writing, I thought about his character. Who he was, how he was able to move between all parts and layers of life in Renaissance Florence. I knew he would be an outsider of sorts, but his sexuality means Aldo’s life is always at risk. Being what we now call a gay man at that time and in that place made you a criminal. So Aldo is both law enforcer and law breaker. When I realised that about him, a lot of his characterisation fell into place. He has a code he follows, things he will and won’t do. He’s a former solider, able to fight for his life when required, and he will kill if he deems that necessary. That makes him dangerous if cornered.

Who do you see playing him in a TV or film adaptation?

Twenty years ago the answer would have been Viggo Mortensen as Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings films. Now I think Shaun Evans who plays the young Morse in the TV drama Endeavour would make a wonderful Cesare Aldo. He’s a great actor, able to convey so much without saying a word – perfect for the often taciturn Aldo!

You’re currently working on a sequel. How far along do you see Aldo’s fortunes unfolding? Do you have a series arc in mind, or are you taking it on a book by book basis?

I have plans for the first four novels, which follow the seasons – winter 1536 in City of Vengeance, spring 1537 for the next book, and on into summer and autumn. There is a clear arc across those individual stories, which I hope readers will want to follow with me and the characters.

What historical fiction and thrillers have influenced you in your writing?

Abir Mukherjee’s novels set in early 20th Century India were a touchstone, the story of a good man working for a bad system of justice. The Leo Stanhope mysteries by Alex Reeve set in Victorian London showed that historical thrillers could have unexpected detectives. Books by Antonia Hodgson and Laura Shepherd-Robinson were also influential, as was the master of historical crime C. J. Sansom – we’re all following in his footsteps, one way or another.

What are you looking forward to reading next?

I’ve just finished an advance copy of Robbie Morrison’s Edge of the Grave, a cracking police procedural set in 1930s Glasgow which is coming out next month (March 2021). That really lives up to the ‘no mean city’ adage, and has all the deadpan humour you would expect of a great Glasgow novel. And I’m eager to read the next book by Liam McIlvanney, which is a sequel to his prize-winner The Quaker.

City of Vengeance by D. V Bishop is published by Pan Macmillan, priced £14.99.

Salena Godden’s debut novel has been deservedly garnering much praise from critics and early readers. Her lyrical, mesmeric story sees her personifying death as a black woman ready to tell her story and experiences. Here, in this extract, we are introduced to Wolf Willeford, who will go on to tell death’s story.

Extract taken from Mrs Death Misses Death

By Salena Godden

Published by Canongate

She came ten-pin bowling into my life, smashing over all that was good and all that made sense. I clung to the memories of my life before, as the weather turned bad and dark storm clouds gathered. It was a horror, a swirling ugly mess of feelings of loss and betrayal and abandonment. The room in my head was cold with the shadow of all that was absent and broken. The silence was screaming and I tipped my head back and screamed into it.

I cried. Of course I cried, I was just a kid and I was alone in the world. I lost a tooth one minute and everything the next. I remember I put the tooth under my pillow, but that night it was not the tooth fairy that came to visit, it was Mrs Death herself. This was my first time watching her at work. It is masterful, the way Mrs Death works. So deliberate. So merciless. There is a system: I’m not sure how it works, but I believe she must have a system and know what she is doing. There has to be a method for who lives and who dies, and when and where, but I cannot work it out. How does she choose? How does she know what’s best? What is supper for the spider is hell for the fly, or some-thing? I forget how that saying goes. Mrs Death is always too too too much. Too soon. Too sudden. Too cruel. Too early. Too young. Too final.

Mrs Death took my mother in one greedy gulp of flame and I watched. I still don’t know why I survived. That last night is in fragments. I can remember the last dinner we had together was a chicken curry. My mum made the best coconut chicken curry. Jamaican cooking is the best. I still miss my mum’s cooking so much. If I had known then that that was the last meal my mother would cook for me, I would have kneeled down and kissed it. I would have only eaten half and saved the rest to eat when I miss her. I would have distilled it, frozen it, locked it in a capsule, kept it in a safe. Or you know, I would have at least said thank you. Instead I just scoffed it down watching telly. I don’t remember what we watched on telly that night, I wish I could. We were being ordinary. We were being normal. Me and Mum on the sofa, we ate chicken curry and rice, we watched some telly and then when we went to bed, she said goodnight.

Goodnight, Wolfie, love you! she said. Night, Mum, love you too. She said the tooth fairy would be coming and remember to put the tooth under my pillow. Stop reading! Switch the light off! she probably said. Mum, what does the tooth fairy look like? Wait and see!

I never found out though. Next thing I knew everyone in the building was shouting and there was panic and smoke and then I was shivering and standing barefoot in my pyjamas in the road. They said there was nothing that could be done. I stood alone, frozen to the spot, cold feet on the wet pavement. Someone wrapped me in an itchy green that smelled sterile. I stared up at our building, the heat, the roaring fire, guffs of black smoke. And all around me was a chaos of blue lights, flashing lights, a scream of sirens, whilst the hungry flames grew higher and higher, scorching tree tops, tongues of flame, licking the heavens. Black pages, black ash, debris drifted, a black ash snow fell around me as our entire building burned. No sprinklers. No alarms. No warning.

I threw my head back and I howled into the charred and blackened sky. My home, my whole world was burning. I let her have it. I tipped my head back and roared and I hoped someone would hear it, perhaps that Death would hear it, hear me crying my heart out. Fat tears rolled down my dirty brown face.

Through the blur I saw a face in the smoke above me, a woman’s face: the face of Mrs Death. A kind black lady’s face was smiling down at me, and her smile, it was gentle, but that made me furious. I screamed at her. I was crying and crying and crying, raining tears to the river to the sea, from salt to salt, from root to root and blood to blood. And the wind swirled and echoed my pains. There was heat, a great heat within my pain, a searing heat in my heart and soul, a pain in my chest and guts and my cries were howls carried in the wind through time and space.

Mrs Death Misses Death by Salena Godden is published by Canongate, priced £14.99.

The 25th February 2021 will be the first Gray Day, a celebration of the writer and artist Alasdair Gray, on the 40th anniversary of his masterpiece Lanark. Canongate will be publishing a new hardback edition of Gray’s seminal debut, as well as new editions of Unlikely Stories, Mostly, McGrotty and Ludmilla and The Fall of Kelvin Walker. BooksfromScotland pays tribute to one of Scotland’s most iconic works by sharing one of its most iconic passages.

Extract taken from Lanark

By Alasdair Gray

Published by Canongate

One morning Thaw and McAlpin went into the Cowcaddens, a poor district behind the ridge where the art school stood.They sketched in an asphalt playpark till small persistent boys (‘Whit are ye writing, mister? Are ye writing a photo of that building, mister? Will ye write my photo, mister?’) drove them up a cobbled street to the canal. They crossed the shallow arch of a wooden bridge and climbed past some warehouses to the top of a threadbare green hill. They stood under an electric pylon and looked across the city centre. The wind which stirred the skirts of their coats was shifting mounds of grey cloud eastward along the valley. Travelling patches of sunlight went from ridge to ridge, making a hump of tenements gleam against the dark towers of the city chambers, silhouetting the cupolas of the Royal infirmary against the tombglittering spine of the Necropolis. ‘Glasgow is a magnificent city,’ said McAlpin. ‘Why do we hardly ever notice that?’ ‘Because nobody imagines living here,’ said Thaw. McAlpin lit a cigarette and said, ‘If you want to explain that I’ll certainly listen.’

‘Then think of Florence, Paris, London, New York. Nobody visiting them for the first time is a stranger because he’s already visited them in paintings, novels, history books and films. But if a city hasn’t been used by an artist not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively. What is Glasgow to most of us? A house, the place we work, a football park or golf course, some pubs and connecting streets. That’s all. No, I’m wrong, there’s also the cinema and library. And when our imagination needs exercise we use these to visit London, Paris, Rome under the Caesars, the American West at the turn of the century, anywhere but here and now. Imaginatively Glasgow exists as a musichall song and a few bad novels. That’s all we’ve given to the world outside. It’s all we’ve given to ourselves.’

‘I thought we had exported other things—ships and machinery, for instance.’

‘Oh, yes, we were once the world’s foremost makers of several useful things. When this century began we had the best organized labour force in the United States of Britain. And we had John McLean, the only Scottish schoolteacher to tell his students what was being done to them. He organized the housewives’ rent strike, here, on Clydeside, which made the government stop the landlords getting extra money for the duration of World War One. That’s more than most prime ministers have managed to do. Lenin thought the British revolution would start in Glasgow. It didn’t. During the general strike a red flag flew on the city chambers over there, a crowd derailed a tramcar, the army sent tanks into George Square; but nobody was hurt much. Nobody was killed, except by bad pay, bad housing, bad feeding. McLean was killed by bad housing and feeding, in Barlinnie Jail. So in the thirties, with a quarter of the male workforce unemployed here, the only violent men were Protestant and Catholic gangs who slashed each other with razors. Well, it is easier to fight your neighbours than fight a bad government. And it gave excitement to hopeless lives, before World War Two started. So Glasgow never got into the history books, except as a statistic, and if it vanished tomorrow our output of ships and carpets and lavatory pans would be replaced in months by grateful men working overtime in England, Germany and Japan. Of course our industries still keep nearly half of Scotland living round here. They let us exist. But who, nowadays, is glad just to exist?’

‘I am. At the moment,’ said McAlpin, watching the sunlight move among rooftops.

‘So am I,’ said Thaw, wondering what had happened to his argument. After a moment McAlpin said, ‘So you paint to give Glasgow a more imaginative life.’

‘No. That’s my excuse. I paint because I feel cheap and purposeless when I don’t.’

‘I envy your purpose.’

‘I envy your self-confidence.’

‘Why?’

‘It makes you welcome at parties. It lets you kiss the host’s daughter behind the sofa when you’re drunk.’

‘That means nothing, Duncan.’

‘Only if you can do it.’

Lanark by Alasdair Gray is published by Canongate, priced £20.00.

To find out more about Gray Day, please visit the Gray Day website.

Craig Russell is an internationally-bestselling writer of gothic, psychological thrillers. Next month, his new novel, Hyde, will be published, and in it, he explores one of Scottish literature’s most famous characters. We caught up with with Craig to chat about his favourite books.

Hyde

By Craig Russell

Published by Constable

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

Honestly? I can’t remember. Books, reading, the written word were always there as part of my conscious environment. My parents always claimed that I could read well before I went to school, and I remember that I always had books around me. I have the oddest, clearest memory—almost a flashbulb memory—from when I was at primary school: they had the alphabet up on the walls, large black letters against white backgrounds. I can still see, very clearly, the lowercase letter ‘a’ in a sans-serif typeface. I know it sounds bizarre, but I knew instinctively that the letter and the word were part of what defined me. Much in the way I suppose a natural mathematician engages with the number.

When I was very young, I read a story about boy, a Pacific Islander, and his conquest of his fear of the sea. I think it was at that point that I realized that reading was a magical device that allowed you to travel to any place or any time. That, I think, is very much what I try to do now that I’m a novelist. If I can transport myself completely to another time, place and experience, hopefully I can bring along my readers.

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest book Hyde. What did you want to explore in writing it?

Hyde is set in Victorian Edinburgh and combines all the elements that excite me personally: conflicting senses of identity, psychology, history, myth and legend. I think every writer explores the complexities, paradoxes and contradictions of their own cultural and historical background.

Hyde isn’t a retelling of Stevenson’s tale. If anything, it’s more of an origin story. Just as Robert Louis Stevenson based the character of Long John Silver on his one-legged friend William Henley, I have suggested that the combined character of Jekyll and Hyde were based on a real acquaintance of Stevenson. My Hyde—Captain Edward Henry Hyde—is superintendent of detective officers of the City of Edinburgh Police. He keeps secret from all but his physician that he suffers from ‘lost time’—periods during which he cannot account for his actions—and is plagued with dark dreams that emerge him in a fantastical landscape populated with figures and monsters from Celtic mythology. With no memory of how he got there, Hyde finds himself at the murder scene of an unknown man, found hanging upside-down above the Water of Leith, a victim of the ancient Celtic three-fold death ritual. He starts to investigate the murder, worried that he himself should be a suspect.

Hyde is heart and soul a dark, gothic thriller, but it is woven through with dualities of all sorts, including Edinburgh’s split-personality (which was the true inspiration of Stevenson’s tale, even if he did set it in London). Hyde also allowed me to interrogate the Scottish sense of self at the zenith of the British Empire. It’s a very different book from The Devil Aspect, but it allowed me to delve back into some of the same Jungian concepts of the role of myth in our sense of identity, and the archetypes that haunt both our dreams and our legends. All of which allowed me to ratchet up the psychological horror.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

God, that’s difficult! I would find it difficult to single out a single book. But, if I had to, I think it would be Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

My first novel, Blood Eagle. My wife and I already had a successful freelance writing business and I rather timidly suggested I wanted to devote time to writing a novel. Her enthusiasm and support was total and I honestly don’t know if I would have stuck with it without her encouragement.

The book as . . . object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

I love beautifully crafted books and I have a collection of Folio Society editions. My favourite, however, would be an heirloom: my copy of Gulliver’s Travels from 1898. My grandmother was awarded it as a school prize, and she gave it to me when I was a child. It’s filled with wonderful illustrations by A.M. Sargent.

The book as . . . rebellion. What is your favourite book that felt like it revealed a secret truth to you?

A combination, in totally contradictory ways, of Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell and The Roads to Freedom trilogy by Jean-Paul Sartre. I read them both when still young and they helped form my political consciousness. I think outsider fiction influenced me greatly and all my protagonists tend to be outsiders, to varying degrees.

The book as . . . entertainment. What is your favourite rattling good read?

Again, this is a tie. The Thirty-Nine Steps by John Buchan and Figures in a Landscape by Barry England. Both pursuit thrillers where the landscape is as much character as setting.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

When I was a teenager, I read all the Russians. And, of course, at that time, Russia was behind the Iron Curtain, and a land and culture in shadow. I read Dostoyevsky, some Tolstoy, all the short stories of Anton Chekhov, and graduated to the social realism of Mikhail Sholokhov—but, above them all, was Nikolai Gogol, whose work I loved. Unable at that time to visit Russia, I built an image of the land and its people. I think my favourite book would have to be The Diary of a Madman and Other Stories.

The book as. . .education. What is your favourite book that made you look at the world differently?

I honestly think that if a book doesn’t challenge one’s view of the world, of oneself, then it isn’t worth reading. There have been so, so many. One of my main literary influences and favourite reads is Heinrich Böll. His style was very simple and direct, yet so powerful. It would have to be a toss-up between his Collected Short Stories and The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum.

The book as. . .technology. What has been your favourite reading experience off the page?

Oh. I’m very last century. Or maybe even century-before-last. Everything I read tends to be physical books. Although I do love audiobooks … I recently listened to the late Anthony Valentine’s narration of Dracula … great stuff.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

The Bridge at Andau by (a very young) James Mitchener. It was recommended to me by Frank Darabont (the writer/director of The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile), whose parents fled the 1956 Soviet crackdown in Hungary. Frank knows I wrote Dead Men and Broken Hearts against the background of the Hungarian Uprising and highly recommended Mitchener’s nonfiction book. I’m really looking forward to it.

Hyde by Craig Russell is published by Constable, priced £16.99.

The future of the union is a subject that will continue to dominate British political discourse throughout the year. David Robinson finds that Gavin Esler’s new book, How Britain Ends, sheds light on how we arrived at our current circumstances and what it may mean in the months and years ahead.

How Britain Ends: English Nationalism and the Rebirth of Four Nations

By Gavin Esler

Published by Head of Zeus

The best bit of Gavin Esler’s latest book is when he gets to grips with Shakespeare. The thesis of How Britain Ends is that it’s Brexit-fuelled English nationalism, rather than the SNP, that will consign what Gordon Brown last month called ‘the world’s most successful experiment in multinational living’ to the rubbish bin of history. You can’t talk about English nationalism without at some stage coming across that speech from Richard II, Act II – you know, the one about ‘this happy breed of men’, ‘this sceptred isle’, ‘this fortress built by Nature for herself against infection’ (ouch), ‘this blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England’ – and Esler’s analysis of it is one of the highlights of his book.

The speech by John of Gaunt is, he says, is ‘one of the most beautifully patriotic found anywhere in literature’, capable of sending shivers up even a Scottish spine. But if you read it right to the end – and I must admit, I never have – its meaning changes. This once-happy land, it concludes, ‘is now leased out … like to a tenement or a pelting farm…’ and ‘This England that was wont to conquer others/Hath made a shameful conquest of itself.’

What else, Remainers like Esler argue, was Brexit? And even if you don’t accept that, look at the speech’s tone. John of Gaunt is emphatically not looking forward to new and exciting developments in the sceptred isle: just the opposite, he is looking back to a time when England was a far more contented place. This ‘nostalgic pessimism’ is, Esler suggests, inherent in almost all writing about Englishness and probably played its part in the 2016 Brexit referendum too. The EU didn’t really matter to most voters – in a survey the previous year only 6 per cent rated it as a touchstone issue – and the complexities of trade tariffs engaged even fewer. But given the chance to have their say, nostalgic pessimism kicked in, and English nationalists kicked the UK out of Europe. And, argues Esler, unless they are ready to accept root-and-branch constitutional reform, they’ve made the break-up of Britain inevitable too.

It’s the English not the Scots, who are swinging the sledgehammer here – or, in Fintan O’Toole’s phrase, ‘practising a form of silent secession from the UK’. Of course, they wouldn’t see it like that: Prime Minister Johnson furtively headed north last month to ‘save the Union’ not destroy it. But ‘getting Brexit done’, the one clear demand of the English nationalists, made this impossible. Taking away Scots’ European identity against their will in the Brexit referendum has made Scottishness more important, not less. To the true Brexiter, this was a price worth paying. In October 2019, Tory pollster Lord Ashcroft found that 76 per cent of Tory Leave voters wanted to push for Brexit even if it meant Scotland gaining independence. Slightly fewer – 74 per cent – thought that Brexit would be worth the sacrifice of Northern Ireland.

To anyone who thinks of themselves as British, those figures are hideous. If Unionists no longer care about the Union, says Esler, ‘the end of Britain is only a matter of time’.

But let’s drill down a bit deeper into Ashcroft’s polling sample. Surely the whole point about those people who didn’t set much store the Union is that they didn’t think of themselves as British in the first place. Nominally, of course, they were: and they wanted the dark blue passport to prove it. But in their heads they weren’t really Brits at all. They were English.

Esler calls these people English nationalists, and so far in this piece I have too. His thesis is that the Conservative party, which has now remodelled itself in the image of UKIP, has taken the UK to the point where it faces three possible futures. The first option, to reinvent Britishness, is unlikely to succeed because the things that made Britain work in the past now no longer do. The second is a form of federalism with a written constitution – basically, a reworking of the ‘Home Rule All Round’ plans from the 1890s that would incorporate much of Salmond’s 2014 independence plan. The final option – doing nothing – may well be the most likely, given the incompetence of the current British government, but would lead to an even more divisive break-up of the UK. Already, he notes, ‘Johnson has done more in a few months to bring about a United Ireland than the IRA managed in three decades of bombings and shootings’. If denied indyref2, Scots will become ‘even more scunnered, thrawn and determined to seek a more extreme form of independence’. The Great Paradox of Brexit – that a mainly English whim to assert independence from the EU could lead to Scotland and Northern Ireland demanding independence from England itself – could soon be complete.

This is a consistently thought-provoking and well-argued book, and yet the more I read it, the more I wondered about English nationalism. Maybe that’s because though I was born in England myself, I’ve never felt its pull. Britishness, yes; Scottishness too. Like everyone else, I’ve noticed how the cross of St George has gradually replaced the Union Jack south of the Border, but if this is a rising tide of millions, a force strong enough to fragment a country, where is its cultural expression? Where are the films clips from the Noughties onwards that you’d use to illustrate the thesis? Where are the books?

Esler is, however, right about one aspect of English nationalism: it is comparatively unexplored. If it does exist, it’s hidden away in the statistics, in the rising number of people who identify as English rather than British in recent censuses. According to the Institute of Public Policy Research, there’s a discernible sense of resentment among their English – especially in the North, home to all of the UK’s fastest declining towns with populations bigger than 100,000 – that Scots have greater political clout and get comparatively more money from the public purse. But that IPPR report was written in 2012, and if there have been any mass demos in favour of an England-only parliament since then, I must have missed them.

So was Brexit proof of rising English nationalism or just a loopy protest vote? I’ll leave that for you to decide, but first I’ll take you back to Shakespeare. What I love most of all about the John of Gaunt speech, that classic statement of English exceptionalism, is the man making it. For John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster, is really Jean de Ghent. Or, as we would say these days, now that his own country has come into being, a Belgian.

How Britain Ends: English Nationalism and the Rebirth of Four Nations by Gavin Esler is published by Head of Zeus, priced £14.99.

This month sees the welcome republication of Jackie Kay’s Bessie Smith. Now including a new introduction, Kay’s book celebrates the life and art of the blues legend through biography, memoir, and fictional exploration. It’s a thrilling read, full of a fan’s love and will make you want to explore Bessie’s music more deeply. BooksfromScotland is on hand to start that ball rolling. We hope you enjoy these clips of an unforgettable talent.

Bessie Smith

By Jackie Kay

Published by Faber

Bessie Smith performs ‘St. Louis Blues’ in the film St. Louis Blues. The only existing footage of Bessie Smith singing. Jackie Kay writes: ‘I remember the shock of the grainy monochrome image of my heroine appearing in this sad tale of woe. There she was, a tall, beautiful woman, driven to drink by her feckless lover.’

One of Bessie’s most iconic songs, ‘Nobody Knows When You’re Down and Out’, recorded as her first marriage was breaking down, and just months before the Wall Street Crash in 1929 that saw her career decline.

One of Jackie Kay’s favourites, ‘Dirty No-Gooder’s Blues’. Jackie Kay writes of first hearing it: ‘It sounded so bad. The very name made you think things you weren’t supposed to be thinking at that age.’

Another one of Jackie Kay’s favourites, ‘Kitchen Man’. Jackie Kay writes: ‘I was a bit nonplussed when I discovered that all those jelly rolls and sugar rolls in those songs had nothing to do with food.’

Bessie’s first hit record, ‘Downhearted Blues’, released in 1923. It sold 750, 000 copies in six months, making her a star.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=go6TiLIeVZA

The brilliant and audacious (and a favourite of BfS – the first Bessie Smith song we heard) ‘Send Me to the ‘Lectric Chair’. Jackie Kay writes ‘The combination of the extraordinary plea with the graphically violent descriptions of the murder makes the song wildly funny. I can imagine women hearing it in 1927 and splitting their sides laughing.’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TZ6w5IlqhSk

Let’s end our Bessie Smith playlist with one of her best party songs, ‘Gimme a Pigfoot and a Bottle of Beer’. Jackie Kay writes ‘The gutsy way she sings that “yeah” is like nobody else. She drags that yeah out of herself. She knew how to let herself go; didn’t give a damn what anyone thought of her.’

Bessie Smith by Jackie Kay is published by Faber, priced £9.99.

Ahead of the Valentine weekend, BooksfromScotland wanted to share an extract from Duncan Mackenzie’s memoir, Cappucino and Porridge, which pays warm tribute to the author’s father, from Harris, stepfather, from Skye, and father-in-law, from Tuscany. Here, though, in this extract, we learn of the romance that brought the two families together.

Cappucino and Porridge

By Duncan Mackenzie

Published by Acair Books

ALE AND I MEET AGAIN.

~.~ My Positive Premonition ~.~

At this juncture, I recall two points from my formative years. Firstly, at primary school age, I had an appetite for the stories of the Greeks and Trojans and of Scotland’s William Wallace. What the Greeks did to Hector was bad enough, but what the English did to William Wallace had me, aged not very much at all, making a solemn vow that I would never marry an English girl. Secondly, I had a distinct and recurring premonition that a tall, blonde girl was going to appear in my life and that would then be that.

Back in the eighties and I cannot explain why, it appears that I was guilty of having in my mind an ignorantly held stereotypical image of Italian girls as being short, dark haired and deeply tanned in appearance. There is no more validity in this than there is in believing that Scottish men all resemble the bearded, kilted piper of cartoon caricature, keen on whisky and on observing what a lovely, bright, moonlit night he was enjoying. To my eternal shame, this did not prevent me from picturing a short, dark bob-cut, deeply tanned, apprentice ‘mamma Italiana’ figure, with arms akimbo when, in 1983, I was invited to take a week off work to accompany my mother and John F to Garden Cottage, Balavil with a young Gori daughter in tow. The idea was sold to me by the offer of the use of my mother’s car (new, reliable, petrol paid by her) to get to a few golf courses and perhaps to Loch Ness and Skye to show them to the imagined ‘short, dark schoolgirl’ Italian guest. She was not English, obviously, but otherwise she was still most unlikely to fit the premonition description, according to my subconscious.

It nearly didn’t happen at all. Alessandra’s letter to Margaret, written at the suggestion of Cipriana, looked for help in finding a job as an au pair/babysitter/nanny for the summer holidays with the practice of English in mind. Ale was at university, majoring in German coupled with English as her secondary subject.

Margaret and her friends were all beyond the stage of needing the kind of help Ale was offering, but she responded with the offer of a two week visit with plenty of English practice available. Ale very nearly graciously declined, as she doubted that the length of stay would provide her with the volume of practice in conversational English that she thought she needed that summer. Fortunately, she decided to accept and booked her flight.

By this stage, both my brother and I had left home, had bought our own flats and my brother was engaged. Dinner was arranged chez Margaret and John F, with my brother and his fiancée forming the reception party at the airport, in the company of Margaret. I would arrive in time for the evening meal once I had played for the Court of Session football team against one of the big law firms in Edinburgh. It was an enjoyable time of the year for me with plenty daylight for evening golf; the rugby season was over, so click into football mode. Some of the opponents didn’t seem to have a switch to click nor anything other than long, metal studs. So, for me, it was a case of, ‘Hello. Welcome to Scotland. Excuse me while I patch up this gouge out of my leg.’

There was no ice to be broken by the time I reached my mother’s house. The ‘short, dark schoolgirl’ of my caricature turned out to be twenty years of age, tall, cascading blonde waves, brown eyes often widened in animated conversation, tanned only to the shade of honey and all hand gestures, loads of hand gestures. She would struggle for an English word, but only for an instant before her hand would be raised as if directing traffic to come to an immediate halt, then, ‘Wait!’ in a distinctly north German accent, followed by the furious turning of pages in a tiny dictionary. She was quite something, but it was Scottish eyes which met Scottish eyes across the dinner table and almost imperceptibly widened at the sight of Ale reaching confidently out to the wine bottle in the centre of the table and helping herself. It didn’t register with the MacKenzie boys that the wine was from Nazareno’s vineyard, sent over with his daughter in gift. Wine at our mother’s table was novel enough for the brothers without the sight of a young guest diving in and helping herself – utterly unthinkable for either son.

The teasing must have started almost immediately, as my brother has been quoted often since as having assured Alessandra that Scots only tease people they like. No doubt Rev and Mrs Fletcher’s eyes met and perceptibly widened when I was found to be helping to dry the dishes after dinner. I am sure that within three hours of our meeting my brother nudged me in the ribs and urged me to befriend the young Italian lady or, at least, something along those lines.

In the days that followed, I am told that I suddenly found time to drive from my office to my mother’s house for lunch and then to reappear for dinner in the evening. Mother, apparently, told family later that Ale would not eat until I arrived, no matter if work, football or golf kept me very late.

On one of my journeys in for dinner, I was nearly delayed on a long-term basis. I had been cruising along quite happily in my old mini, when a black car came right out in front of me from a side road on my left. It felt like the wee mini’s nearside wheels left the ground as it got itself round the black car before making it back on to its own side of the road – no anti-lock braking systems in those days, at least not in old minis. Looking back to see if the other car was ok, I saw it had stopped so I did the same. The driver came forward to thank me and congratulate me, in colourful terms, for my evasive action. We parted as new best buddies. Alessandra’s reaction, on hearing of the incident after dinner, was (wide-eyed of course) to take my hand in both of hers – nice. I was really getting to like this very foreign girl.

As to the week which followed, there is an unusual source of information. On 14th December 1996 Ale, John, Seumas and I were surprised to find ourselves in colour on the cover of the weekend section of one of Scotland’s national newspapers with the words ‘The Europeans’ emblazoned below. The four of us, pre-Finlay, were surrounded by cartoon Santas in the traditional styles of half a dozen European countries. The Glasgow Herald was running a feature on how Europeans had made Scotland their own. What had the Europeans found in Scotland? What did they miss? What part did they see Scotland playing in Europe?

In addition to the group photo on the front, inside there was a close-up of Ale, taken at her desk, the caption reading, ‘The Gaelic Dolce Vita.

Ale had clearly spoken freely to the writer of the article, Jane Scott. There are one or two quotes which, on re-reading the piece for the first time in many years, I found touching. In addition, there was a paragraph on Ale which remains pertinent, namely, ‘Her first foreign language was German. When she first came here, she had a German accent, but she has a superb ear. When she speaks now it is pure Edinburgh. After holidays on Harris, the island of Duncan’s father, her accent is often mistaken for Hebridean. She is proud of that.’ Ale still comes back from Harris sounding like Auntie Mary Ann in Quidinish.

The article did carry one serious error slap bang in the middle of the headline which read, ‘A first kiss upon the moor.’

No.

On the absolute authority of one of the parties to that first kiss, it is confirmed that it did not occur up on the moor. It happened a good two or three hundred yards below the edge of the Balavil moor, on the track, in the woods. Alessandra leaned forward, she still insists, to brush away a beastie which had landed on my collar. I misinterpreted the approach and there we had ‘the first kiss upon the track, two or three hundred yards down from the moor and thanks, in part at least, to a visiting insect.’

The suggested trip to Loch Ness did not happen, but the two of us did take off for a day trip to the Isle of Skye which is only about two hours away from Balavil.

Scotland, it must be admitted, had a very good summer in 1983, good enough to amount to a clear case of innocent misrepresentation to a visiting Italian. We stopped off at Invergarry where Ale took a photo from the riverbank. An enlarged version of that photo has hung above our open fireplace for over thirty years and it shows that the day must have been quite hot.

While we were walking in single file along a narrow path in the glen, I realised that things had gone quiet. There was no sound at all from the enthusiastic conversationalist behind me. I turned around to find Ale looking like a feeding duck, head in the river, both cooling off and controlling the former cascading waves, which had first become slightly unruly curls and which then became, instead, cascading ringlets; so, cooled and controlled, the operation worked on both counts. The feeding duck reference is perhaps best consigned to history; she probably didn’t find it funny, even then.

Over on Skye, on Broadford pier to be precise, I heard a burst of Italian (no German accent) which rang a few bells from early Latin classes, Amo, amas, amat and all that. By the time the week was nearing its end, we had talked about Protestant/Catholic and Scottish/Italian marriage and even the raising of children. Discounting the 1974 discovery of bivouacked children in my home, I had known Alessandra for all of two weeks.

Cappucino and Porridge by Duncan Mackenzie is published by Acair Books, priced £15.95.

The annual Burns celebrations are always a welcome moment in the dark January month. This year, Black and White Publishing have released a sumptious celebration of the bard, Burns for Every Day of the Year. Author Pauline Mackay gives us poems and commentary for each day, a perfect way to introduce yourself or rediscover his brilliant work. Here, we share entries for late January to accompany your Burns suppers.

Burns for Every Day of the Year

By Pauline Mackay

Published by Black and White Publishing

25th January

Robert Burns was born on the 25th of January 1759 in Alloway, Ayrshire. It is commonly believed that the first Burns Supper was held in Alloway in July 1801 to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the bard’s death. A gathering of contemporaries and admirers paid tribute to Burns by reading from his works, raising a toast to his memory and dining on haggis, a dish traditionally regarded as peasant food. They agreed to meet again in January of the following year to celebrate the bard’s birth and the tradition developed from there. Burns Night is now a truly global phenomenon: the biggest annual celebration of any author worldwide.

‘To a Haggis’ is the bard’s ode to the dish that has since become the culinary centrepiece of any Burns Supper. Haggis is comprised of those parts of a sheep that would not fetch a good price at sale: heart, lungs and liver combined with oats and seasoning, and boiled in the sheep’s stomach. In a performative piece, abundant with imagery, Burns presents the haggis as nutritious, hamely fare, unpretentious and truly worthy of celebration.

Why not try performing the poem at your own Burns Supper? By the end of this ‘warm-reekin, rich’ address, your company will be ravenous!

To a Haggis

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great Chieftain o’ the Puddin-race!

Aboon them a’ ye tak your place,

Painch, tripe, or thairm:

Weel are ye wordy o’a grace

As lang’s my arm.

The groaning trencher there ye fill,

Your hurdies like a distant hill,

Your pin wad help to mend a mill

In time o’need,

While thro’ your pores the dews distil

Like amber bead.

His knife see Rustic-labour dight,

An’ cut you up wi’ ready slight,

Trenching your gushing entrails bright,

Like onie ditch;

And then, O what a glorious sight,

Warm-reekin, rich!

Then, horn for horn they stretch an’ strive:

Deil tak the hindmost, on they drive,

Till a’ their weel-swall’d kytes believe

Are bent like drums;

Then auld Guidman, maist like to rive,

Bethankit hums.

Is there that owre his French ragout,

Or olio that wad staw a sow,

Or fricassee wad mak her spew

Wi’ perfect sconner,

Looks down wi’ sneering, scornfu’ view

On sic a dinner?

Poor devil! see him owre his trash,

As feckless as a’ wither’d rash,

His spindle shank a guid whip-lash,

His nieve a nit;

Thro’ bluidy flood or field to dash,

O how unfit!

But mark the Rustic, haggis-fed,

The trembling earth resounds his tread,

Clap in his walie nieve a blade,

He’ll mak it whissle;

An’ legs, an’ arms, an’ heads will sned,

Like taps o’ thrissle.

Ye Pow’rs, wha mak mankind your care,

And dish them out their bill o’ fare,

Auld Scotland wants nae skinking ware

That jaups in luggies;

But, if ye wish her gratefu’ pray’r,

Gie her a haggis!

26th January

Even in the absence of manuscript evidence, ‘The Selkirk Grace’ has long been attributed to Burns. Another Burns Supper favourite, it represents an important part of the almost ritualistic running order of the festivities.

The Selkirk Grace

Some hae meat and canna eat,

And some wad eat that want it:

But we hae meat and we can eat,

Sae let the Lord be thankit.

27th January

If haggis is the culinary centrepiece of the Burns Supper, then whisky is its most popular accompaniment. ‘Scotch Drink’ is Burns’s most explicit celebration of the Scottish national tipple and one of the country’s most successful exports (alongside the bard himself). In the following extract, Burns wittily extols the inspirational and illuminating ‘benefits’ of a dram.

Scotch Drink

Let other Poets raise a fracas

’Bout vines, an’ wines, an’ drucken Bacchus,

An’ crabbed names an’ stories wrack us,

An’ grate our lug:

I sing the juice Scotch bear can mak us,

In glass or jug.

O thou, my MUSE! guid, auld SCOTCH DRINK!

Whether thro’ wimplin worms thou jink,

Or, richly brown, ream owre the brink,

In glorious faem,

Inspire me, till I lisp an’ wink,

To sing thy name!

Let husky Wheat the haughs adorn,

And Aits set up their awnie horn,

An’ Pease and Beans, at een or morn,

Perfume the plain,

Leeze me on thee, John Barleycorn,

Thou king o’ grain!

On thee aft Scotland chows her cood,

In souple scones, the wale o’ food!

Or tumbling in the boiling flood

Wi’ kail an’ beef;

But when thou pours thy strong heart’s blood,

There thou shines chief.

Food fills the wame, an’ keeps us livin;

Tho’ life’s a gift no worth receivin,

When heavy-dragg’d wi’ pine an’ grievin;

But oil’d by thee,

The wheels o’ life gae down-hill, scrievin,

Wi’ rattlin glee.

Thou clears the head o’ doited Lear;

Thou chears the heart o’ drooping Care;

Thou strings the nerves o’ Labor-sair,

At’s weary toil;

Though ev’n brightens dark Despair,

Wi’ gloomy smile

28th January

We draw towards the close of this month with another of Burns’s Bacchanalian productions. Famous for its representation of conviviality and revelry in male friendship, ‘Willie Brew’d a Peck o’ Maut’ was inspired by a meeting between Burns, William Nicol (1744–1797) and Allan Masterton (c.1750–1799). Burns recalled that, ‘We had such a joyous meeting that Masterton and I agreed, each in our own way, to celebrate the business.’ And so, Masterton composed the air to which Burns’s song is set.

Willie Brew’d a Peck o’ Maut

(to the tune of Willie Brew’d a Peck o’ MautO Willie brew’d a peck o’ maut,)

O Willie brew’d a peck o’ maut,

And Rob and Allan cam to see;

Three blyther hearts, that lee-lang night,

Ye wadna found in Christendie.

Chorus: We are na fou, We’re nae that fou,

But just a drappie in our e’e;

The cock may craw, the day may daw,

And aye we’ll taste the barley bree.

Here are we met, three merry boys,

Three merry boys I trow are we;

And mony a night we’ve merry been,

And mony mae we hope to be!

Chorus: We are na fou, &c.

It is the moon, I ken her horn,

That’s blinkin’ in the lift sae hie;

She shines sae bright to wyle us hame,

But by my sooth, she’ll wait a wee!

Chorus: We are na fou, &c.

Wha first shall rise to gang awa,

A cuckold, coward loun is he!

Wha first beside his chair shall fa’,

He is the King amang us three!

Chorus: We are na fou, &c.

Every Day of the Year by Pauline Mackay is published by Black and White Publishing, priced £20.00.

Looking for more books to celebrate Burns Night? Check out . . .

The Canongate Burns, edited by Andrew Noble and Patrick Scott Hogg

The Canongate Burns, edited by Andrew Noble and Patrick Scott Hogg

The Edinburgh Companion to Robert Burns, edited by Gerard Carruthers

My Luve’s Like a Red, Red Rose, illustrated by Ruchi Mhasane

Tam o’ Shanter, adapted by Richmond Clements and illustrated by Inko

The Life of Robert Burns, by Catherine Carswell

The Jewel, by Catherine Czerkawska

On the Trail of Robert Burns, by John Cairney

A Night Out With Robert Burns, edited by Andrew O’ Hagan

The Wee Book Book o’ Burns, by The Wee Book Company

With the rise and rise of Gaelic learners on Duolingo, there is no shortage of people interested in finding out more about Gaelic language and culture. Luath Press have just released a brilliant anthology of new and classic Gaelic poetry, from writers representing the past, present and future of Gaelic writing. Here, we share a few poems from the anthology – we hope it will spur you to investigate further.

100 Favourite Gaelic Poems

Edited by Peter Mackay and Jo Macdonald

Published by Luath Press

’s i ghàidhlig

Donnchadh MacGuaire

’S i Ghàidhlig leam cruas na spiorad

’S i Ghàidhlig leam cruas na h-èiginn

’S i Ghàidhlig leam mo thoil inntinn

’S i Ghàidhlig leam mo thoil gàire

’S i Ghàidhlig leam mo theaghlach àlainn

’S i Ghàidhlig leam mo shliabh beatha

’S i Ghàidhlig leam luaidh mo chridhe

’S i Ghàidhlig leam gach nì rim bheò

Mur a b’ e i cha bu mhì

gaelic is

Duncan MacQuarrie

Gaelic to me is the hardness of spirit

Gaelic to me is the grit of distress

Gaelic to me is my mind’s satisfaction

Gaelic to me is the pleasure of laughing

Gaelic to me is my beautiful family

Gaelic to me is my life’s mountain

Gaelic to me is the love of my heart

Gaelic to me is everything in my life

If it didn’t exist I wouldn’t be me

*

faclan, eich mara

Caomhin MacNèill

nam bhruadar bha mi nam ghrunnd na mara

agus thu fhèin nad chuan trom

a’ leigeil do chudruim orm

agus d’ fhaclan gaoil socair nam chluasan

an-dràsta ’s a-rithist

òrach grinn ainneamh

man eich-mhara, man notaichean-maise

sacsafonaichean beaga fleòdradh

words, seahorses

Kevin MacNeil

i dreamt i was the seafloor and you were the weight of ocean pressing down on me, your quiet words of love in my ears now and again, golden, elegant and strange, like seahorses, like grace-notes, tiny floating saxophones

Trans. the author

*

màiri iain mhurch’ chaluim

Anna C. Frater

Mo sheanmhair, a chaill a h-athair air an “Iolaire”,

oidhche na bliadhn’ ùir, 1919

Tha mi nam shuidhe ag èisteachd ribh

agus tha mo chridh’ a’ tuigsinn

barrachd na mo chlaisneachd;

’s mo shùilean a’ toirt a-steach

barrachd na mo chluasan.

Ur guth sèimh, ur cainnt

ag èirigh ’s a’ tuiteam mar thonn

air aghaidh fhuar a’ chuain

’s an dràst’ ’s a-rithist a’ briseadh

air creag bhiorach cuimhne;

’s an sàl a’ tighinn gu bàrr

ann an glas-chuan ur sùilean.

“Bha e air an ròp

an uair a bhris e…”

Agus bhris ur cridhe cuideachd

le call an ròpa chalma

air an robh grèim gràidheil agaibh

fhad ’s a bha sibh a’ sreap suas

nur leanabh.

Agus, aig aois deich bliadhna,cha robh agaibh ach cuimhne air a’ chreig

a bhiodh gur cumail còmhnard;

’s gach dòchas a bha nur sùilean

air a bhàthadh tron oidhch’ ud,

’s tro gach bliadhn’ ùr a lean.

Chàirich iad a’ chreag

agus dh’fhàg sin toll.

Chruadhaich an sàl ur beatha

agus chùm e am pian ùr;

agus dh’fhuirich e nur sùilean

cho goirt ’s a bha e riamh;

agus tha pian na caillich

cho geur ri pian na nighinn agus tha ur cridhe

a’ briseadh às ùr

a’ cuimhneachadh ur h-athar.

“… oir bha athair agam …”

màiri iain mhurch’ chaluim

Anne C. Frater

My grandmother who lost her father on the “Iolaire”,

New Year’s Night, 1919

I sit listening to you

and my heart understands

more than my hearing;

and my eyes absorb

more than my ears.

Your soft voice, your speech

rising and falling like waves

on the cold surface of the sea.

and now and again breaking

on the sharp rock of memory;

and the brine rises up

in the grey seas of your eyes.

“He was on the rope

When it broke. . .”

And your heart also broke

with the loss of the sturdy rope

which you had clung to lovingly

while you were growing

as a child.

And, at ten years of age,

you had only a memory of the rock

that used to keep you straight;

and every hope that was in your eyes

was drowned on that night