We are certainly living through an era of great change, stress and strife,with a news cycle that can often seem overwhelming. In News and How to Use It, former journalist Alan Rusbridger helps readers make sense of our news media landscape. In this extract of his book, he introduces our current dilemma.

Extract taken from News and How to Use It: What to Believe in a Fake News World

By Alan Rusbridger

Published by Canongate

Who on earth can you believe any more?

I am writing this at the peak – or so I hope – of the most vicious pandemic to have gripped the world in a century or more. The question of what information you can trust is, all of a sudden, a matter of life and death.

As an average citizen you have four choices about where to find information on this new plague.

You can believe the politicians. That might work if you live in, say, New Zealand or Germany – less so if you are in Brazil, Russia, China, Hungary or the United States. And maybe not so much in Britain.

What about the scientists? As politicians have struggled for authority – or even understanding – some leaders thrust scientists and doctors into the limelight. We began to absorb many lessons in epidemiology, immunology, exponential curves, antibody tests, vaccines and the modelling of viral infections. And we learned that scientists disagree with each other. They harbour – and value – doubts. They even change their minds. To some this is reassuring; to others, confusing.

Or we can turn to our peers. As always, there is good and bad on social media; expertise and madness; inspiration and malicious nonsense. New words have been coined – infodemic and infotagion are just two – to describe an environment of viral information chaos which nevertheless has proved massively addictive as people the world over stumble in search of light.

And then there is journalism. There has been much to admire here: some brave reporting from inside hospitals and on the streets; some clear and honest analysis; some tough investigations into governmental advice and inaction; some brilliant visualisation of data and some admirably simple explanations of complex concepts. The best news organisations have performed a real, vital public service.

But – as with social media – there is bad to counter the good. Some were slow to grasp the immensity of what was happening. There will be a special place in journalistic hell for Fox News and its initial torrent of Trump-echoing propaganda. That coverage will have helped contribute to numberless deaths. There was lamentable confusion about how to cover the nightly parade of presidential lies, sulks, boasts and vainglorious irrelevance that flagged itself as public information. There was uncertainty about how to communicate risk.

Some news outlets – initially, at least – seemed unable to imagine the scale of what was happening: it was easier to report on what videos Boris Johnson was watching in his hospital bed than on the hundreds dying every day all around. The newsrooms that had jettisoned their health or science correspondents struggled. The idiots who suggested that 5G phone masts could be spreading the disease encouraged arson and trashed their own brand. So, it was a mixed picture.

Covid-19 could not have announced itself at a worse time in terms of the question about whom to believe. Survey after survey has shown unprecedented confusion over where to place trust. Nearly two-thirds of adults polled by Edelman in 2018 said they could no longer tell a responsible source of news from the opposite.

This was not how it was supposed to be.

The official script for journalism was that once people woke up to the ocean of rubbish and lies all around them they’d come back to the safe harbour of professionally-produced news. You couldn’t leave this stuff to amateurs or give it away for free. Sooner or later people would flood back to the haven of proper journalism.

This official narrative was not completely wrong – but nor was it right in the way the optimists hoped it would be. There was a surge of eyeballs to mainstream media sites, but it was too soon to judge if the increased traffic would remotely compensate for the drastic loss of revenues as copy sales plummeted and advertising disappeared. It normally didn’t.

At the very moment when the UK government recognised journalists as essential workers, the industry itself looked more fragile than ever.

Surveys of trust showed the public (especially the older public) relying on journalists, but not trusting them. Another Edelman special report in early March 2020 found journalists at the bottom of the trust pile, with only 43 per cent of those surveyed holding the view that you could believe them ‘to tell the truth about the virus’. That compared with 63 per cent for ‘a person like yourself’.

As the pandemic wore on, so trust in both UK politicians and news organisations slumped. Between April and May 2020, according to Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ), trust in the government plunged a full 19 points – partly, it was thought, as a result of newspaper investigations which appeared to show double standards between what the government was saying and what its top advisers were actually doing. But if reporters expected gratitude for their efforts they were disappointed: the same period saw an 11-point fall in trust in news organisations.

I spent most of my working life in journalism: I would like people to believe the best of it. I like the company of journalists and, as an editor, was frequently lost in admiration for colleagues – on the Guardian and beyond – who were clever, brave, resourceful, quick, honest, perceptive, knowledgeable and humane.

But it was impossible to be blind to so much journalism that was none of those things: editorial content that was stupid, corrupt, ignorant, aggressive, bullying, lazy and malign. But it all sailed under the flag of something we called ‘journalism’. Somehow we expected the public to be able to distinguish the good from the bad and to recognise it’s not all the same, even if we give it the same name.

The official story paints journalists as people who tell ‘truth to power’. But ‘truth’ is a big word, and we seldom like to reflect on our own power.

Now, four years on from being full-time in the newsroom, I want to bring an insider’s perspective to the business of journalism, but also look at it from the outside. How can we explain ‘journalism’ to people who are by and large sceptical – which is broadly what most of us would want our fellow citizens to be? This book aims to touch on some of the things about journalism that might help a reader decide whether it deserves their trust, and offer a glimpse to working journalists of how they are viewed by the world outside.

News and How to Use It: What to Believe in a Fake News World by Alan Rusbridger is published by Canongate, priced £18.99.

The long-awaited third novel by Jenni Fagan has just been published, and BooksfromScotland know that it’s already going to be one of the literary highlights of the year. We caught up with Jenni to ask her about her favourite books.

Luckenbooth

By Jenni Fagan

Published by William Heinemann

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

First memory of a book would probably be reading fairy tales and taking it really seriously, I didn’t want to be the girl who had toads fall from her mouth (rather than pearls) because she said horrible things about people, I knew if I didn’t help an old lady at the well then I’d grow a scaly tail (I am elaborating) and much, much later when I discovered Baba Yaga and her house on chicken legs that turns in circles and sits to rest and it all made perfect sense to me.

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest book Luckenbooth. What did you want to explore in writing it?

Luckenbooth is a love letter to Edinburgh. I moved here when I was three years old and it’s a city of extremes, dark and light, wealth and poverty, mercurial, moody, pretty, exasperating, it’s a big village with iconic aspirations and the history is always on show in our architecture and pubs and lots of other things, I wanted to explore the unseen, the strange, occult, brilliant, unnerving, the guttural howl and institutional malaise, all kinds of things. The novel travels through nine decades of different characters lives in an Edinburgh tenement but their stories are all tied together by a curse, placed on Luckenbooth, when the devil’s daughter moved in to the building in 1910. Jessie MacRae reappears all the way through in one way or another and we finally find out the buildings oldest secret right at the end.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

I’m not sure any one book has informed how I see myself, there have been books that gave me a real ‘ah’, moment. The Color Purple by Alice Walker is about a young girl growing into a woman, in the American South in between wars. Celie is a young black girl born into poverty and her book takes the form of letters to God, and later her sister. Her life really called to me, her voicelessness and the journey she took all throughout her life was so inspiring, I read it first when I was a teenager and it meant a lot to me.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

I liked reading Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak to my wee boy years ago, also The Hobbit, The Gruffalo’s Child was pretty good too. I am bonded by a love of certain stories to anyone who also has an affinity with them, The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery (among others), Breece D’J Pancake’s Trilobites, lots of Scottish female writers I discovered when I was younger, Laura Hird, A.L. Kennedy, Ali Smith, Sandie Craigie, this could go on endlessly actually.

The book as . . . object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

My favourite beautiful book is a very elaborate hardback edition of The Tibetan Book of the Dead. It’s really pretty. I am a sucker for a good looking book. I read a lot of religious texts and books over the years and sometimes I revisit them, this one looks great on any book shelf though.

The book as . . . entertainment. What is your favourite rattling good read?

I would struggle to pin down one single book that is a ‘rattling’ good read, I’ll choose Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison for a book that hooks you in on the first line and returns you back to the world a day or so later, a much better person for it. Bone is such an amazing protagonist and I adore Dorothy Allison, I think she is one of America’s greatest living writers.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

This is hard to pin down to one book but I’ll choose The Yacoubian Building by Alaa Al Aswaany. I read it when I was staying in a no stars pension in Downtown Cairo for a wee while, it tells the stories that are unseen and it made my time in Egypt so much richer for reading it.

The book as. . .education. What is your favourite book that made you look at the world differently?

A book that made me look at the world differently is Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka. I return to it often. The story seems perfectly told. Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning as an ‘ungezeifer,’ we don’t have a translation for the original German word but it means some kind of monstrous vermin. He has tiny wriggly legs and a big shell for a body and he can no longer speak in a way that humans understand, he just screeches. It is the story of how the individual no longer exists if they are not serving the structures that surround them, family, workplace, government, firstly financially but secondly by not being ‘other,’ or a burden in any kind of a way. I love this book.

The book as. . .technology. What has been your favourite reading experience off the page?

I do not read off the page. I have never even held a kindle. However, I love seeing flashes of poetry out in the world like Tracy Emin’s neon signs, or more recently I thought the projection of Kayus Bankole’s A Sugar For Your Tea, projected onto City Chambers in Edinburgh. The piece explored Scotland’s role in the slave trade and was so beautifully written, powerful and humane, it was a piece that greatly impressed me.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

The book as the future, I am looking forward to reading a few things next, Helen McClory has a novel Bitterhall coming out in 2021, also Salena Godden has a novel out in January Mrs Death Misses Death, also Deep Wheel Orcadia by Harry Josie Giles, a science fiction verse novel written in Orcadian, they are all on my list!

Luckenbooth by Jenni Fagan is published by William Heinemann, priced £16.99.

Author Richard Hallewell, known primarily for his walking guides, has used his extensive knowledge of nature to create this wonderful childrens’ story, which tells the tale of Ka, a jackdaw who discovers a special talent for communicating with other birds and animals. When he is banished from his family, he embarks on a journey to seek out the mythical figure of the Old Raven. On his travels he meets many creatures including, in this extract, two crows.

Extract taken from Ka, the Ring and the Raven

By Richard Hallewell

Published by Hallewell Publications

SO Ka flew north once more, now hugging the coast. At first, he didn’t stop to ask the way, but on the afternoon of the second day he began to spot strange crows, a piebald black and grey, and recognised the hooded crows described by Swartfeather. After that, whenever he needed to feed or rest he would always look for a hoodie, introduce himself, and ask about Riach and the Old Raven. Both were always known, but both were always simply ‘north’. On he flew, past hills and then mountains, crossing deep arms of the sea and offshore islands. The weather was mixed, but never warm: days of sharp winds and rain, and others of grey, bone-chilling gloom.

A week after he had started, the cloud lifted and the sun shone brightly, bringing an unseasonable warmth. Ka was flying through a landscape he could never have imagined a few weeks before: a line of huge, undulating cliffs, falling sheer into the sea, occasionally broken by shallow bays with wide sand beaches backed by low dunes and sandy grassland cropped by sheep. He began to feel a deep tiredness, and remembered one of Swartfeather’s lessons.

‘Fatigue will sneak up on you on a trip like this,’ he had said. ‘Watch out for it. It makes you slow and stupid. If you can’t rest then you can’t, but if you can, do it!’

Ka peered down at the land, looking for somewhere safe to roost. There were no trees and no buildings, but looking closely at the cliff top he spotted something else: two crows – or something like crows – a male and a female, striding across the short grass behind the cliff edge. They looked a little larger than a jackdaw, but smaller than Swartfeather, and, though their feathers were a glossy black, they had bright red legs and narrow, curving red bills. They were choughs. Ka drifted down and landed beside them.

‘Hello,’ he said, in a mewing cat-like voice which turned out to be perfect conversational chough. ‘My name is Ka.’

The choughs stared at him with astonishment for a moment, then glanced at each other, before the male bird said:

‘Hello. I’m Branek, and this is Eseld. I’m sorry . . . I do apologise for staring – it must seem terribly rude – but we have never seen a bird like you before . . .’

‘. . . And we certainly haven’t met any bird which could speak to us,’ said Eseld. ‘Unless it was another chough.’

‘I’m a jackdaw,’ said Ka. ‘From the south. And I haven’t seen any others like me on this coast, so I may be the only one. And I’m fairly sure I’m the only one which would be able to speak to you, anyway.’

‘How extraordinary,’ said Eseld, with enthusiasm. ‘We are new here ourselves, you see . . .’

‘. . . So, for all we knew, it might be absolutely typical of birds here . . .’ said Branek.

‘. . . We just couldn’t be sure,’ concluded Eseld.

Ka found himself whipping his head from side to side as the birds completed each other’s sentences. After the austere discourse of the crows and hoodies, he found the conversation charming, but he was so tired that he was barely able understand what the birds were saying.

‘I have to apologise again,’ said Branek. ‘We are here on our own . . .’

‘No other choughs, that is,’ said Eseld. ‘When we got paired up we decided to head off by ourselves and find somewhere of our own to live . . .’

‘. . . So it’s rather nice to find someone else we can actually talk to,’ said Branek. ‘We are not usually quite so talkative . . . I say, are you quite all right?’

‘Oh . . . just a little faint,’ said Ka, who was shocked to find that he was on the very edge of collapse. ‘I don’t suppose you know of anywhere I could rest up, do you? I seem to have flown a very long way and I need a sleep more than I have ever needed anything.’

The two choughs looked at each other for a moment, then Branek said: ‘Well, if you can fly just a short way further, we have found a terrific cave in the cliffs . . .’

‘. . . The views are wonderful, and it isn’t a bit draughty,’ said Eseld. ‘Except when the wind is in the north west . . .’

‘. . . And there will be plenty of room for you to rest there,’ said Branek.

So the three birds took off, folded their wings to dip over the edge of the cliffs, then swooped in a low arc across the face of the rocks, with the calm water lapping idly against the edge of the cliff below. Ka was struck by the elegance of the choughs’ flight, and slightly embarrassed by the efforts he needed to make just to keep up. Fortunately, if was not a long flight, and in a few moments they landed on a little ledge jutting out from the cliff. At one end was a large rock, behind which was the entrance to a dry, shallow cave. Ka entered and looked around, then turned to the choughs to thank them – he may even have opened his beak to do so – but before he could utter a single word he had fallen into a deep sleep.

Ka, the Ring and the Raven by Richard Hallewell is published by Hallewell Publications, priced £10.00.

Heading into the new year, BooksfromScotland asked various Scottish publishers what they were looking forward to publishing and reading this year. Here we share their recommendations.

Allan Cameron, Vagabond Voices

For a start I should catch up on Gabriela Cabezón Cámara’s The Adventures of China Iron (Charco Press) which was shortlisted for the Booker. I like the sound of Tania Skarynkina’s collection of essays from Byelorussia, A Large Czeslaw Milosz with a Dash of Elvis Presley (Scotland Street Press) and the new edition of Douglas Watt’s The Price of Scotland (Luath Press), which takes another look at the Darien Scheme. Perhaps most compelling for me is Kerri ní Dochartaigh’s Thin Places (Canongate), this ‘mixture of memoir, history and nature’ examines ‘how violence and poverty are never more than a stone’s throw from beauty and hope’. Having grown up in Northern Ireland during the troubles with one parent from one community and one from the other community, Ní Dochartaigh found some solace in natural landscapes.

For a start I should catch up on Gabriela Cabezón Cámara’s The Adventures of China Iron (Charco Press) which was shortlisted for the Booker. I like the sound of Tania Skarynkina’s collection of essays from Byelorussia, A Large Czeslaw Milosz with a Dash of Elvis Presley (Scotland Street Press) and the new edition of Douglas Watt’s The Price of Scotland (Luath Press), which takes another look at the Darien Scheme. Perhaps most compelling for me is Kerri ní Dochartaigh’s Thin Places (Canongate), this ‘mixture of memoir, history and nature’ examines ‘how violence and poverty are never more than a stone’s throw from beauty and hope’. Having grown up in Northern Ireland during the troubles with one parent from one community and one from the other community, Ní Dochartaigh found some solace in natural landscapes.

At Vagabond Voices, in September 2021 will bring Volume II of our Estonian pentalogy by A.H. Tammsaare, Truth and Justice, which has had more success in North America, even though the rural world of late nineteenth-century Estonia has many parallels with the Highlands in the same period. The pentalogy, which is similar in construction to A Scots Quair, shifts to the cities in this volume and then pass through the Revolutions of 1905 and 1917 in the next volume. Volume IV takes us into the interwar period independence, and finally in the last volume, the protagonist returns to the countryside for a reflective summary of those eventful years.

Before that, we will be bringing out three books in March and April: Siblings is a short novel by Magnus Florin, whose pared-down prose narrates more through what is suggested and through what is written down on the page. Mither Tongue is a collection of poems by Jidi Majia in Chinese and Nuosu (a minority language in China) and translated into English and Scots. How about that for perfect symmetry! Anne Pia’s The Sweetness of Demons is an evocative series of responses to fourteen of Baudelaire’s poems, which emphasises the range and originality of the great French poet who embodied the fin de siècle. An ambitious and thankfully very successful project.

Jean Findlay, Scotland Street

I have just read Shuggie Bain (Picador) and loved every minute of it. It is a painful read, but the pain is all redeemed by love. It is also a good Covid read, because it makes you realise that there is always someone worse off than yourself, and no matter how much we suffer with restrictions, there are still children out there who suffer more simply because of poverty. Also that this suffering can be transmuted into wisdom. Yes there is a great deal in that book.

I am looking forward to Scotland Street’s first themed publication year. ‘International Women 2021’ will publish women from Canada, South Africa, India, the US and Scotland. The Christmas novel 2021 will be my own, The Hat Jewel, started in 2014 and winner of Hawthornden Fellowship 2018, and Lavigny Fellowship 2019. It has certainly been a long time in coming. My former editor, Jenny Uglow, advised me to publish it under SSP. So here goes.

The Floris Books Team

Suzanne Kennedy, Sales and Marketing Director

My son will be getting Alex Wheatle’s The Humiliations of Welton Blake (Barrington Stoke) for his forthcoming January birthday — sure to be a great introduction to his teen years!

Home of the Wild by Louise Grieg and Julia Moscardo is a stunner from us for this coming season. A perfect lockdown picture book about a young boy with a real connection to nature and the natural world who finds an orphaned fawn. He nurtures her to independence and then must learn to let go. Culminating with a gentle turn of events this is luminous, gorgeous and heartwarming.

Kirsten Graham, Marketing Campaigns Executive

The Spellbinding Secret of Avery Buckle is exactly the type of book I loved to read as a child – full of wonder and adventure, with characters you want to be best friends with. Featuring a magical library and portals that can transport you around the world, it’s the perfect world to escape to!

Elaine Reid, Community Marketing Manager

In our gorgeous forthcoming picture book Olwen Finds Her Wings, co-created by mother and daughter team Nora and Pirkko-Liisa Surojegin, Olwen the baby owl longs to roar like a bear or hop like a hare, but finds she can’t. What can little owls do? Set in a beautiful woodland landscape, you’ll find yourself encouraging Olwen on as she continues her search to find out what makes her special.

Ali Begg, Sales and Marketing Assistant

A new David MacPhail book is the comic relief we all need this Spring, and Velda is the hero that we deserve. Fearsome, swashbuckling and hilarious in equal measure, with cracking zany illustrations from Richard Morgan, I can’t wait to see Velda the Awesomest Viking in print and start recommending it to parents. Particularly ideal for reluctant readers or kids that are making their first forays into chapter books, join the fun as Velda proves she’s the roughest toughest Viking around!

A new David MacPhail book is the comic relief we all need this Spring, and Velda is the hero that we deserve. Fearsome, swashbuckling and hilarious in equal measure, with cracking zany illustrations from Richard Morgan, I can’t wait to see Velda the Awesomest Viking in print and start recommending it to parents. Particularly ideal for reluctant readers or kids that are making their first forays into chapter books, join the fun as Velda proves she’s the roughest toughest Viking around!

As we plummet into another lockdown, I find myself in search of journeying narratives, and Randa Jarrar’s upcoming Love is an Ex-Country (Sandstone) looks to be an incredible and powerful story. Told as a road trip across the USA, it charts her extremely personal experiences as a Palestinian daughter shamed for who she is, and a teenage mother rebelling against an abusive family. And. Look. At. That. Cover. Beautiful stuff.

The Kitchen Press Team

Nasim Mawji

One book by a Scottish publisher that I’m really looking forward to reading is The Unusual Suspect by Ben Machell (Canongate). I can’t resist a good crime thriller and this one is all the better for being true. It tells the story of Stephen Jackley, a British geography student who at the start of the global financial crisis in 2007 reinvented himself as a modern day Robin Hood and began robbing banks to redistribute wealth from the rich to the poor. He used disguises and fake weapons and robbed several banks before he was eventually apprehended and it was discovered that he also had Asperger’s. It sounds thrilling and promises to be ‘dark’. Perfect.

I’m so excited to be publishing Jeni Iannetta’s Bad Girl Bakery Cookbook in October. Jeni was a passionate home baker before moving to the Highlands and opening the Bad Girl Bakery. Quite soon customers were traveling from miles around to visit her cafe and she was producing tens of thousands of portions of cake a month and supplying high-profile clients like the National Trust for Scotland and the Caledonian Sleeper, to name just two. She takes pride in creating cakes that celebrate flavour and texture and look impressive but don’t take ages to prepare. With no-fuss recipes that utilise home-baking techniques, this book unlocks the secrets to many of her most popular bakes and is sure to inspire joy, not only in the eating but in the process of baking too.

Emily Dewhurst

One thing that got me through the last year was getting out of the house and going out on my bike so I’m thrilled that the first title in our new Food for Sport series is a cycling book. It’s by Kitty Pemberton Platt and Fi Buchanan, and shares how female cyclists fuel their rides. I first saw Kitty’s illustrated food diaries on instagram, and loved how she celebrated the reality of life on the bike: yes, you might start the day with granola and a protein shake, but it turns out a handful of Haribos and an espresso is what is going to get you through the last 25km of a hard days ride. The book brings together diaries from a whole range of cyclists from enthusiastic amateurs to professionals across a range of distances, with tips and hacks for what works for them. Fi Buchanan (of the greatly missed Heart Buchanan deli in Glasgow’s West End) has created corresponding recipes to charge you up pre-ride, keep you going while you’re on the road and share with friends once you’ve hit the finish line. As well as providing inspiration on easy and tasty ways to fuel up, it’s a celebration of the female cycling community. Out in June.

One thing that got me through the last year was getting out of the house and going out on my bike so I’m thrilled that the first title in our new Food for Sport series is a cycling book. It’s by Kitty Pemberton Platt and Fi Buchanan, and shares how female cyclists fuel their rides. I first saw Kitty’s illustrated food diaries on instagram, and loved how she celebrated the reality of life on the bike: yes, you might start the day with granola and a protein shake, but it turns out a handful of Haribos and an espresso is what is going to get you through the last 25km of a hard days ride. The book brings together diaries from a whole range of cyclists from enthusiastic amateurs to professionals across a range of distances, with tips and hacks for what works for them. Fi Buchanan (of the greatly missed Heart Buchanan deli in Glasgow’s West End) has created corresponding recipes to charge you up pre-ride, keep you going while you’re on the road and share with friends once you’ve hit the finish line. As well as providing inspiration on easy and tasty ways to fuel up, it’s a celebration of the female cycling community. Out in June.

A new Alan Warner book is always a treat, so I’m very much looking forward to reading Kitchenly 434 (White Rabbit) – it sounds like classic Warner territory: male delusion, romantic misadventure and the resentments of the class divide in a rock star’s Sussex Mansion at the tail end of the 70s. I can’t wait.

Ailsa Bathgate, Barrington Stoke

Onjali Q. Raúf is one of the most exciting authors at work in children’s publishing today, able to address pressing social issues in a way that makes them accessible to younger readers and encourages discussion, so we’re thrilled to be publishing The Great (Food) Bank Heist with her in July 2021. In this story Onjali gives a heart-rending child’s-eye view of the growing problem of food poverty and as with all her stories, she provides relief through her unique ability to combine empathy with humour in a madcap adventure that sees a group of enterprising friends use their ingenuity to expose a shameful heist targeting the local food bank. We can’t wait to share it!

Francesca Barbini, Luna Press Publishing

As an Italian, I really cherish the opportunity to access Speculative and SFF fiction in other languages. Translating from other languages and into other languages is a big part of what I set out to do with Luna Press. So this Spring we have two releases which cross that language barrier. The first is an SF collection by Brazilian author Fabio Fernandez, Love: An Archaeology. The second is an anthology of Greek SF, Nova Hellas: Stories from Future Greece. This particular book will be released in English, Italian and Japanese.

Another important aspect of Luna Press is going beyond fiction, through the projects of Academia Lunare, where papers and essays are explored further through the use of short stories. In June, we’ll be publishing Jane Alexander’s The Flicker Against the Light and ‘Writing the Contemporary Uncanny’. The insightful essay is enriched by clever storytelling to bring us all into the world of the uncanny.

Finally, as a speculative Scottish Press, we are always on the lookout for amazing and entertaining Scottish authors. This is how we met Barbara Stevenson, from Orkney. Barbara’s fabulous sense of humour, paired to her surreal imagination, will be brought to life in The Dalliances of Monsieur D’Haricot. And I am also thrilled that it will be released in Italian as well.

Because of my passion for translated works, I always look at Charco Press’s releases with anticipation. Whether is a new author or an established one, I get a chance to read fabulous South American literature. I’m also interested in Radical Acts of Love, by Janie Brown (Canongate). It’s about an oncology’s nurse conversation with the dying. I actually find these books very comforting, as they remind me of how much good is done every day in the world. I also want to read Love is an ex-country by Randa Jarrar (Sandstone). Randa is from Palestine, a land where I have spent a bit of time. Her personal account sounds intriguing and I’m really looking forward to hear it.

Aisling Holling, Saraband Books

We’re bringing out great books in 2021. Three that I want to particularly highlight are In a Veil of Mist by Donald S Murray, How to Survive Everything by Ewan Morrison and Case Study by Graeme Macrae Burnet.

We’re bringing out great books in 2021. Three that I want to particularly highlight are In a Veil of Mist by Donald S Murray, How to Survive Everything by Ewan Morrison and Case Study by Graeme Macrae Burnet.

After the wonderful reception for As the Women Lay Dreaming, both from readers in the Western Isles and an audience far beyond, we are thrilled to publish another deeply poignant novel from Donald based on a little-known piece of Hebridean history. Evocative literary fiction exploring the human cost of war and the Cold War arms race: the perfect follow-up to Murray’s Paul Torday Prize-winning first novel.

How to Survive Everything is a biting satire wrapped in an electrifying thriller confronting the huge global issues of our time – from disease, fake news, consumerism and denial of science all the way to family dysfunction and mental health in crisis. Ewan is one of the most inventive, provocative and acclaimed writers of his generation, and once again he’s created a powerful and unforgettable voice in a young protagonist. On top of this, it’s extremely fast-paced and often funny.

It is a real honour to be publishing Graeme Macrae Burnet’s highly anticipated fourth novel; and dare we say – his best yet! Case Study extends Burnet’s playful ‘metafictional’ approach, and this time presents an enthralling, layered and profound novel exploring 1960s psychiatry and society. Drawing the reader so effortlessly into the mind and world of the protagonist, Burnet has created yet another set of unforgettable characters that feel deceptively real.

Ann Crawford, National Galleries of Scotland

The team at NGS Publishing have found that there is one silver lining to the lockdown life – the opportunity to spend even more time reading books. On our combined reading lists, you will find The Wind That Lays Waste (Charco Press), Scabby Queen (HarperCollins), Duck Feet (Monstrous Regiment) and Wheesht (KDD).

We were thrilled to be working in the autumn on Ray Harryhausen: Titan of Cinema by Vanessa Harryhausen, his daughter. The pioneer of stop-motion cinema is famous for films such as Jason & the Argonauts and he counts many Hollywood giants among his fans – but he was also a great Dad, husband and friend. This book, which is filled with personal images as well as many of Harryhausen’s famous and not-so-famous creatures, tells us the uplifting story of the real Ray Harryhausen from the point of view of his daughter and people who worked with him. Perhaps it is the sheer joy in the book that has resulted in the need to order a reprint just days after the first stock arrived.

We were thrilled to be working in the autumn on Ray Harryhausen: Titan of Cinema by Vanessa Harryhausen, his daughter. The pioneer of stop-motion cinema is famous for films such as Jason & the Argonauts and he counts many Hollywood giants among his fans – but he was also a great Dad, husband and friend. This book, which is filled with personal images as well as many of Harryhausen’s famous and not-so-famous creatures, tells us the uplifting story of the real Ray Harryhausen from the point of view of his daughter and people who worked with him. Perhaps it is the sheer joy in the book that has resulted in the need to order a reprint just days after the first stock arrived.

Looking ahead, we are finalising a publishing programme for 2021 that we know will be an offer of real colour and fascination into the months ahead. Among the titles coming is a new, highly illustrated book about the incredibly popular Scottish artist, Joan Eardley. In exploring how she portrays land and sea, Patrick Elliott uncovers brand new findings and brings new insight into the artist’s work and her love of the coastal village of Catterline.

Michele Smith, Jasami Publishing

We have a lot of exciting books coming out this year. I’m particularly looking forward to publishing Joy Dakers’ and Catherine Grace’s Journeys With Joy: Scotland, a photography book with short stories, as it will not only display the varied beauty of Scotland, but there will be a captivating short story to kindle the imagination of the reader giving a new and diverse perspectives. We are also looking forward to publishing the poetry book, Reflections of a Scotsman by Gordon McGowan. The poems are funny, tragic, intriguing, and absorbing as he encounters all aspects of the world we live in. For children we’ll have Bernie the Bear by written by Catherine Grace and illustrated by Holly Richards about the antics of a bear lost in the city and how those antics relate in his natural home. Bernie really entertains and educates children about what happens when urban life encounters nature. I am also looking forward to reading Precious and Grace (Abacus) by Alexander McCall Smith. I have read most in this series No, 1 Ladies Detective Agency, as they are always heart-warming and absorbing read.

Alan Windram, Little Door Books

In looking forward to 2021 it’s hard not to feel the ever present shadow of Covid and Brexit looming over us. But this is also a year that is very exciting for us at Little Door Books. We have three different types of debuts publishing this year within our list spanning age ranges from zero to nine year-olds. Alongside our picture books we are thrilled to be publishing a board book for 0-3 year olds which is a TV tie in with the popular Cbeebies animated series, Hushabye Lullabye. We follow cuddly little alien Dillie Dally as he flies to planet dream in the a unique lullaby jukebox Hushabye Rocket. Written and created for TV by Sacha Kyle, we’ll be publishing in June.

For the 3 – 6 age range, in July we are publishing a Little Door Debut picture book by brand new illustrating talent Madeline Pinkerton and her book A Dragon Story. Her warm, classical-looking illustrations perfectly combine with a wonderful story about bravery, following your own path, and friendship. A story loving dragon and a feisty young girl who loves to tell stories develop an unlikely friendship.

Also on the debut front, in April, we venture into another age range as we publish our first chapter book for 6 – 9 year-olds, a magical, fantasy adventure written by award-winning writer and journalist David C Flanagan, Uncle Pete and the Boy Who Couldn’t Sleep. This is Dave’s first book for children and is a hilarious adventure of the imagination involving the remarkable journey undertaken by Uncle Pete and his fearless female sidekick, with themes of determination, collaboration, ingenuity, kindness and acceptance. It’s also got fabulously quirky chapter illustrations by Will Hughes.

With all this excitement and more coming up this year I hardly have time to read myself but I must say I am really looking forward to getting into some crime fiction with Chris Brookmyre’s new novel, The Cut, coming out in March and the next book in Elaine Thomson’s Jem Flockhart series, Nightshade (Constable) which is out in April. Spending every day running a children’s publisher I do like to escape with a bit of crime fiction.

With all this excitement and more coming up this year I hardly have time to read myself but I must say I am really looking forward to getting into some crime fiction with Chris Brookmyre’s new novel, The Cut, coming out in March and the next book in Elaine Thomson’s Jem Flockhart series, Nightshade (Constable) which is out in April. Spending every day running a children’s publisher I do like to escape with a bit of crime fiction.

Here’s to a 2021 of fabulous books for all ages, and I hope you will join us as we step out into this year with something new and different for our little readers.

David F Ross is a brilliant novelist, growing his fanbase with every release. When he is not writing, he is an architect – director of Keppie Design – and a facilitator of projects for design students at the City of Glasgow College. Last year, he oversaw the the students designing what book festival spaces might look like in the future, and here, we present the students ideas. Exciting food for thought!

There’s Only One Danny Garvey

By David F. Ross

Published by Orenda Books

The Outliers Book Festival: A Design for the Future

In the latter part of2020, this most unusual of years, I was invited to mentor design students from City of Glasgow College for an interesting project. Through collaborative practice, the BA Design Practice Degree -4th year (hon) students were to explore the possibilities for the creation of a new literary festival for 2021, planned to celebrate literature, and inspired by the ideas of togetherness, connections, relationships, physicality, meetings and rendezvous.

The students were free to decide whether the festival would feature a specific site, several variable locations, or even a digital ‘virtual’ space. This decision would depend on their findings when researching the target group, the project’s context and the possible interpretations of “meeting place”.

This process culminated in the form of a client presentation to the festival ‘organiser’, Karen Sullivan; the award-winning publisher of Orenda Books.

Designers are encouraged to understand how things have been and to analyse how they are now, to explore how they might be. This is the essence of design process. The global pandemic has turned our traditional analytical approaches upside down. Where the commerce of collaboration and connection once drove the type of spaces we wanted to be in, fear of contamination now controls them.

Book Festivals are facing hugely complex challenges as an unsurprising consequence. Paradoxically, there has been a rise in the sales of books and a dramatic resurgence in the popularity of reading. Taking cognisance of this, the City of Glasgow College design students responded imaginatively.

Fresh Horizons

The Fresh Horizons pavilion is a pop up venue that can be placed in any kind of location, from warehouses, school and university campuses and outdoor parks.

‘Our ‘Fresh Horizons’ pavilion is inspired by the Paisley pattern, which was in turn, inspired by the ‘Boteh’ of Persian origin, first incorporated into fabric designs in India. The Boteh is emblematic of the influence of other cultures and represents the aim of our project: a place to celebrate translated works of fiction from across the world.’

(Lynn and Martin)

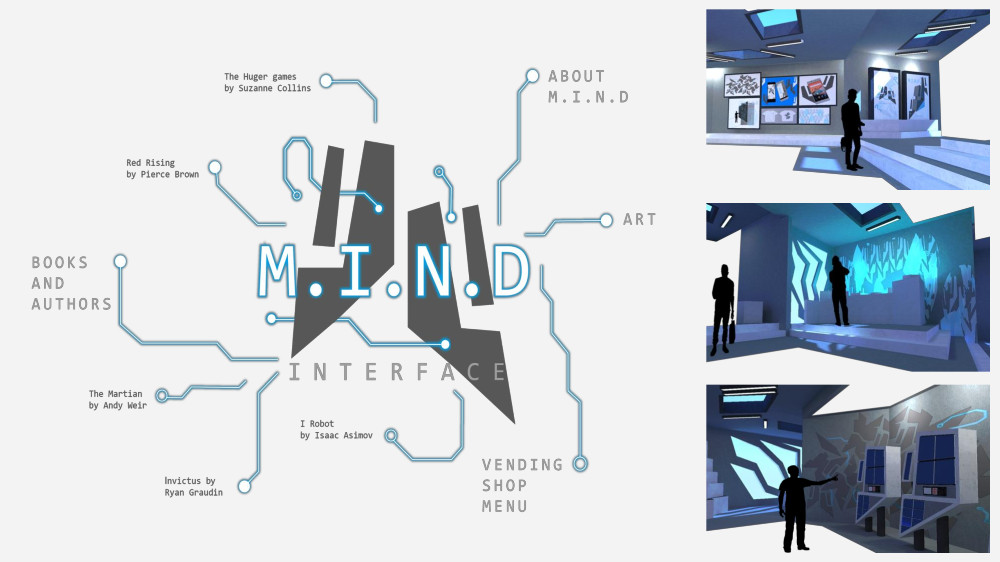

MIND

MIND celebrates science-fiction by offering a daring authorless space with immersive, interactive exhibits using apps and AI technology.

Our Modular Interactive Novel Design (M.I.N.D) offers a unique experience in which festival users can immerse themselves in not only the structure but the atmosphere of the ongoing festival. Those with the passion for reading can discuss, share, listen, purchase, and even participate in a multitude of activities and events that encapsulate the genre of Sci-Fi. As a group, we believe that the project we have created offers a realistic direction for the future of book festivals. With the use of modern design techniques and innovative thought processes, we believe we have created an effective, forward thinking design solution to the Outliers Book Festival brief.

(Jade, Lewis, Becca and Beth)

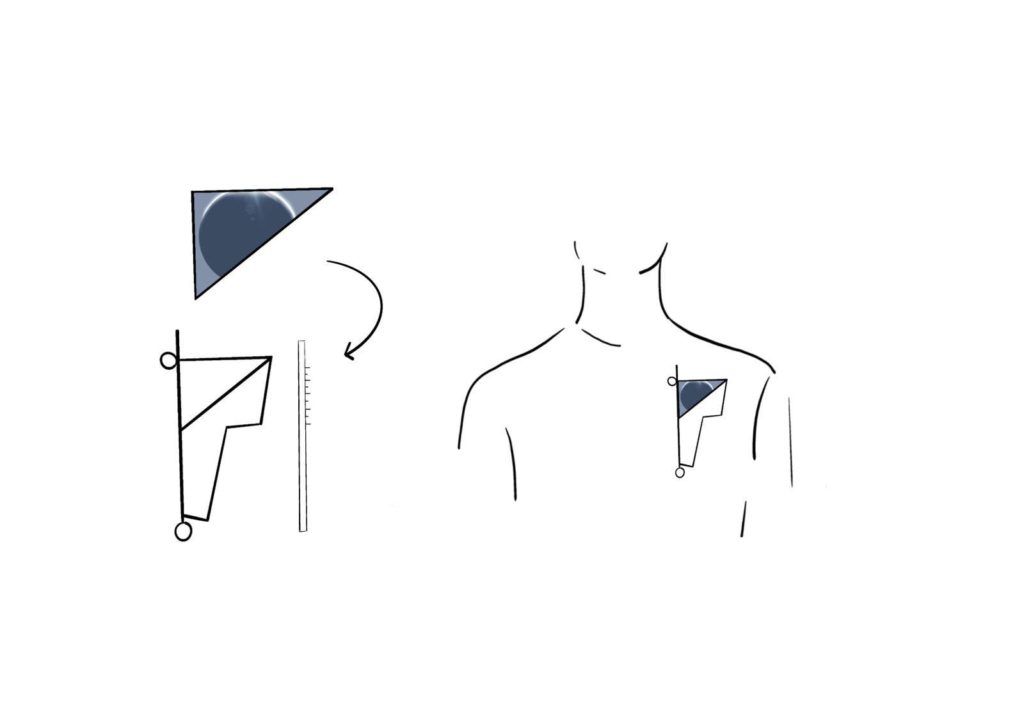

The group behind MIND have even designed their own merchandise too.

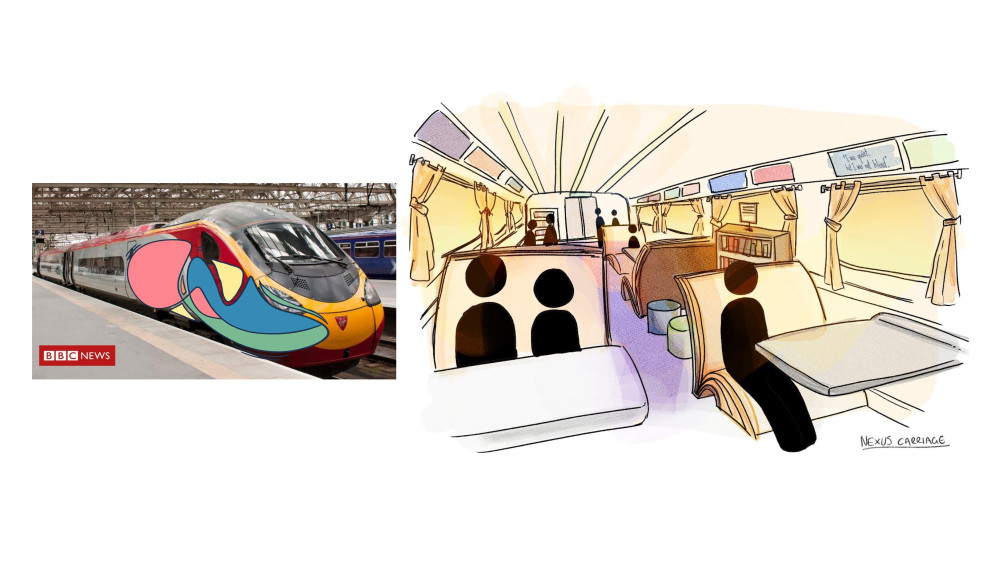

Nexus Train

Alice and Stephanie’s ‘Nexus Train’ proposal features a moving festival with events taking place on a series of trains. Individual carriages are dedicated to individual authors or specific genres of literature depending on theme. Reading and events can be given from the trains to socially distanced audiences on the platforms. A brilliant graphic design advertising campaign promotes author readings and visual experiences from the outside of the carriages and on the platforms of the towns and cities on six different routes.

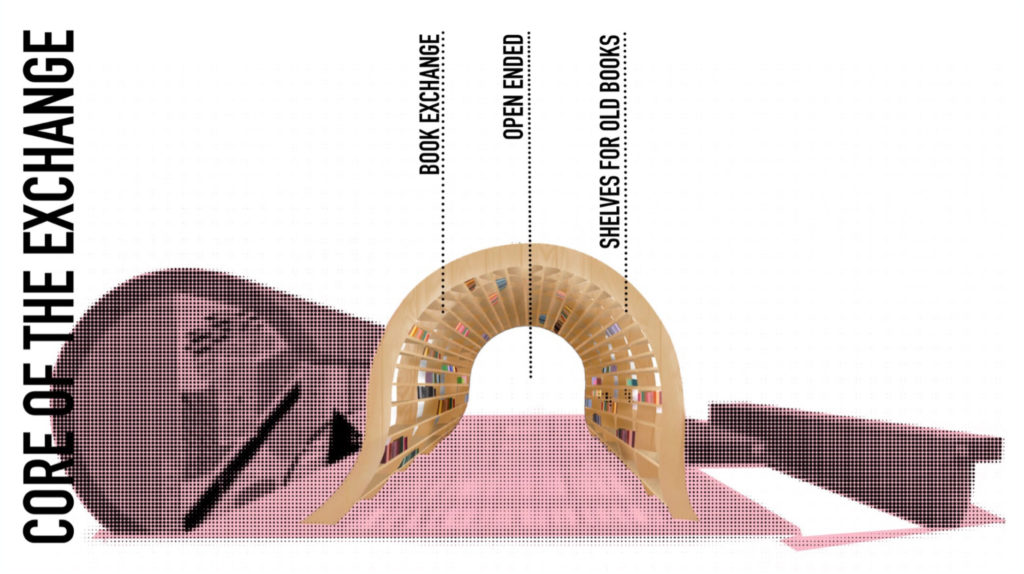

The Pheonix

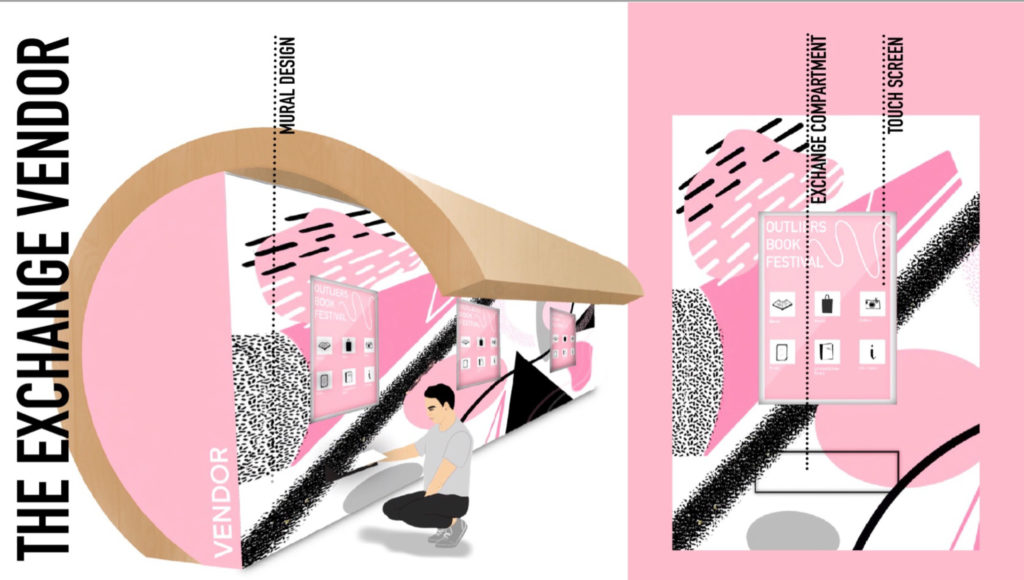

Meanwhile, ‘The Phoenix’ – by Calum, Caitlin, Jordan and Nichola – is based at the Barras Art and Design (BAaD); an already established creative hub which is part of Glasgow’s East End transformation. This design centres on sustainability and personal interaction with opportunities for book lovers to design and print new book covers for their favourite titles. Other components include the interactive Exchange Vendor; a curving timber structure which encourages the exchanging of books as way of ‘recycling’ literature.

The Pheonix is a walk-through pop up venue that incorporates interactive exhibits celebrating book design’

The City of Glasgow College design courses are fantastic explorations of real-world projects. They require the students to analyse and understand complex design considerations before developing creatively pragmatic solutions. The ‘Outliers Book Festival’ project is a perfect example of this. The publishing industry is grappling with how to promote writers and books in a post-pandemic world, and the solutions reached by the students are not only impressively creative but hugely practical and deliverable.

The engagement of ‘live clients’ in the education process is vital for all practice-based learning development but none more so than in the creative industries where successful solutions are often subjective. Understanding the brief from the perspective of the client, and then communicating responsive ideas clearly and confidently is the basis of our profession and these students have demonstrated how much they understand this already. It wouldn’t surprise me if many of these ideas feature in the book events of the future.

‘The presentations were engaging, enlightening and thought-provoking, and really do represent viable options for book festivals of the future. I loved the creativity … the potential for pop-up venues, vending machines for books and merchandise (essential in a post-Covid world?), moving a festival around the country via train to engage readers everywhere, themes of literacy and regeneration (sustainable literacy!) that have been placed at the heart of so much of what we, as publishers, hope to do. There were new forms of delivery, from 3D printing onsite and apps to enhance the festival experience through to AI technology and QR codes for ebooks, celebrations of international literature with the emphasis on oneness rather than being ‘foreign’, and original, artistic interpretations of familiar backdrops and even seating.

Our lives have changed dramatically in the last ten months or so, and we need to rethink the way we present books and authors, the way we engage readers, the way we embrace the newest technologies. With online events taking precedence, readers will undoubtedly demand to see more of this in the future, and creative ways to provide access will become integral to any festival planning. The students offered explosive food for thought … and the freshness, vibrancy, immediacy of their visions and ideas are really worth contemplating – and incorporating.’

(Karen Sullivan, Publisher, Orenda Books)

Perhaps more than other professions, designers crave contact with others; to be creative, to be stimulated, to be inspired and, yes, sometimes to disagree. All are essential and necessary means of the trial and error design process. An educational environment in which these things can return as before is a universally shared ambition, even if currently difficult to imagine. As a profession we evaluate problems in the wide context where we find them and explore solutions that overcome not only those known problems, but anticipated ones that may emerge out of new phenomena. This experience of this project will stand these students in very good stead for their own future careers as designers.

“The ‘Outliers Literary Festival’ Project brought together individuals in a multi-disciplinary student project. Each team demonstrated innovation and sophisticated interpretations to the brief. Their research demonstrated insights into key issues such as sustainability, community engagement, user experience and above all the needs of the client. There was a significant amount of research underpinning each proposal. I was most impressed with the final presentations which demonstrated a confident and articulate delivery to the panel. The students were all able to present a compelling narrative with supporting visuals clearly addressing the key points in the brief and taking cognisance of earlier client feedback discussed at the interim review.”

(John Baird. Curriculum Head, Faculty of Creative Industries, City of Glasgow College)

The students:

Jade Frame, Lewis McKechnie, Becca Collins, Beth Cowan, Alice Brown, Stephanie Boyd, Lynn Crew, Martin Poli, Calum Lockerbie, Caitlin Smith, Jordan Russell and Nichola McArthur.

Now, let’s concentrate on David’s talents as a novelist. He has just released his latest, There’s Only One Danny Garvey, set against the backdrop of lower league football. Here he is giving a wee taster reading.

There’s Only One Danny Garvey by David F. Ross is published by Orenda Books, priced £8.99.

The beautiful book: the perfect Christmas present. David Robinson finds, in Lachlan Goudie’s The Story of Scottish Art, that not only is the book beautiful, but an inspiration for travel.

The Story of Scottish Art

By Lachlan Goudie

Published by Thames & Hudson

IV36 3WX. DD2 5SG. PA1 1DG. I’ve never reviewed a book through the medium of postcodes, but there’s a first time for everything, and in the case of Lachlan Goudie’s The Story of Scottish Art, it seems appropriate. A book like this, packed as it is with fine reproductions of paintings and sculptures, usually inspires its readers to go back to the galleries where they can see the originals, but with me, that wasn’t the case: none of those postcodes contain galleries. Yet in 2021, after I’ve had my jags and when the world is back to normal, Goudie’s book made me want to travel to all three of them.

What works of art will I be looking for? I’ll give you three clues. Before I read Goudie’s book I hadn’t heard of any of them, so while they may be well known to some, they’re not mega-famous or established stop-offs on the tourist trail. They’re also to do with Death and Christianity, yet none of them are graves. Any help?

IV36 is Forres and 3WX narrows that down to a solidly suburban street that used to be the old road to Findhorn. A hundred yards to the north is a huge white-painted tubular bridge for pedestrians over the main Inverness-Aberdeen road which runs beneath it. Why the bridge is there I have no idea because according to Google Maps, there’s nothing much on the other side apart from flat, featureless fields. Trust me, I won’t be going there for the view.

No: the reason to visit my first postcode is to check out the contents of what looks like an enormous glass box on the east side of Findhorn Road.The carvings on the red sandstone pillar are probably too weather-worn to make out as clearly as I’d like. Even without going there, I suspect that I’ll feel a bit let down when I finally do.

And yet I really will go there in 2021. Why? Because Lachlan Goudie had sold me on it. He’d already taken me, without a hint of artspeak, on an east coast trail of Pictish carved stones, ending up in front of what you have probably already correctly worked out is Sueno’s Stone. On one side of it there’s an enormous cross, but it’s the other side that is really interesting. Carved into this 21-foot pillar are incredibly detailed battle scenes, like a Pictish graphic novel. Goudie describes them from top to bottom: first, the cavalrymen marshalling before battle, then the bloody fight itself and, at what looks like knee height, the triumphant victory parade afterwards. Like a latter-day Rosemary Sutcliff, he gives us the sounds of battle and highlights some of its more gruesome sights, all in a particularly vivid present tense.

Goudie’s book isn’t like any art history book I’ve read. For one thing, he’s neither an academic or an art historian, but a painter trying to uncover what’s particularly Scottish about Scottish art. So he’ll commit all kinds of sins against academia, like calling artists by their first names once he’s introduced them, stringing together superlatives to emphasise why we should be interested in them, and making a series of often unsubstantiated subjective judgments. His is a very broad-brush approach, and given that he has five millennia to work through, and that he’s throwing architecture and sculpture into the mix too, perhaps it has to be. His book won’t dethrone Duncan Macmillan’s magisterial Scottish Art 1460-2000 as the essential book on (most of) his subject but then again, it isn’t trying to.

Essentially, the book is everything you’d expect from the 2015 four-part TV series on which it was based – well structured, informal and informative. His page on Sueno’s Stone is a case in point. This is one of those artworks when we don’t need the footnoted caution of academia, not least because academia hasn’t got a clue about it. We don’t know who they were, these people who hacked each other to death on the edge of what is now suburban Forres. We don’t even know where the battle was, when it was, what the war was about, who commissioned the stone, or who worked on it. “A final creative yell left to echo down the ages,” Goudie calls it. Me, I’d call it a massive sandstone question mark. Think you know your ninth-century ancestors? Think again.

What about our 15th century ones? For that, I’ll be heading to DD2 5SG – in other words to St Marnock’s church, Fowlis Easter, about half a dozen miles outside Dundee. Again, it doesn’t look much from the outside, but this is one of Scotland’s finest surviving medieval parish churches (built in 1180). Inside, it has one of only two painted rood screens to have survived the Reformation.

If you’re thinking ‘So what?’, let me put it another way. About a century before Knox kickstarted the Reformation up the road in Perth, here is rare primitive religious painting from old Catholic Scotland. Again, we don’t know the artist, but as Goudie points out, the people painted around 1480 at the foot of the Cross in this 5ft x12ft wooden panel certainly look like locals. They’re there, along with an unidealised Christ and even a jester, in a painting of charming naivety which itself was almost crucified during the Reformation, with angels’ faces scratched out and the rest of it damaged by hammered nails. It only survived, Goudie points out, because the green paint with which it was painted over in 1612 gradually flaked away.

The final stop on this vaguely mystical tour – PA1 1DG – is, as you have probably guessed, right in the heart of Paisley. Having just finished reading Pat Barker’s Life Class trilogy, I knew a small bit about the artists of the First World War, but I’d never heard of Alice Meredith Williams, who sculpted what looks like a spectacularly imposing memorial to the conflict. In our multicultural age, no-one would dream of commissioning a statue of the enormous Crusader knight who stands atop Sir Robert Lorimer’s equally gigantic (too high?) plinth. But it’s the four flanking stone infantrymen that intrigue me more because even though they are idealised to some extent, they still look as though they were drawn from life. And so they should, because Alice’s husband Morris – though not an official war artist – provided her with whole albums full of unflinchingly realistic sketches of life and death in the Flanders trenches. Over a century on, there’s still something incredibly moving about those four soldiers, their greatcoat collars up, striding purposefully forward alongside a mounted warrior from a different, but still faith-soaked, era.

This is already, I must admit, already a death-obsessed journey into Scottish art, so I’m almost afraid to mention Allan Ramsay’s 1741 portrait of his dead son, though I must because it is one of the most moving images I have seen: click on https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/5348/infant-son-artist and tell me I’m wrong. Like all the other three, it is something I had never seen before I read Goudie’s book. I’m not convinced by his conclusion that there is “a character to Scottish art, a strand of creative DNA that originates in this place” – apart from Sueno’s Stone, all the artworks I’ve mentioned could easily have originated in other places too. But if there’s still anyone out there who thinks that Scottish art is provincial, obscure and unimportant, there is a verve, beauty and breadth of imagination about the artworks in this book that will make them change their minds. And if you’re still looking for good ideas for Christmas presents, it’s definitely worth adding to the list.

The Story of Scottish Art by Lachlan Goudie is published by Thames & Hudson, priced £25.

As the latest volume in Alexander McCall Smith’s serial novel comes to an end in The Scotsman newspaper, David Robinson looks back at working on the series on the release of A Promise of Ankles.

A Promise of Ankles

By Alexander McCall Smith

Published by Polygon

For many years, there has been one editing job that I have looked forward to more than all others. Ever since 2004, when the first volume of Alexander McCall Smith’s 44 Scotland Street ‘daily novel’ first appeared in The Scotsman, I’ve been in charge of making sure that it did so without any mis-spellings or grammatical howlers before it went on to be published by Polygon. As Sandy has somehow acquired the knack of writing at speed (1000 words an hour), to length, and with minimal mistakes, this is one of the easier jobs in journalism. Because those words are also loaded with a fair dollop of wit and wisdom, it is also one of the more enjoyable.

Last week the 14th volume – a world record for a serialised novel, no less – ended its run in The Scotsman, ahead of publication this week by Polygon as The Promise of Ankles. Time perhaps for an insider’s guide to the crafting of a serial novel.

Though ubiquitous in the nineteenth century, these days the serial novel is a rarity. One of the few recent examples is American writer Armistead Maupin’s Tales from the City series. When Sandy met him in California in 2003, he made that very point. Why weren’t more writers following his example, he asked him. When Sandy mentioned this in an article in the Herald, I wondered the same thing. Would he himself be interested in writing a series novel? I asked. Yes, he replied.

Over lunch at The Witchery in Edinburgh, the Editor of The Scotsman expressed delight at the news. ‘But would you be able to write it daily?’ he asked as we rose from the table. Sandy hadn’t been expecting that. After all, Dickens, Flaubert, Tolstoy, Zola, Hardy and all the other star serial novelists of the 19th century usually had at least a month between instalments. Even readers of Maupin’s serial fiction in the San Francisco Chronicle had to wait for a week for the next episode. A successful daily novel would be a world first.

The true serial novel isn’t just one that has already been written and chopped up into equal-length chapters. Instead, it is created on the hoof: once made, mistakes can’t be corrected, characters changed, or dialogue rewritten. If all novels are tightrope walks, this is one without a safety net. Typically, McCall Smith starts off with about 20 episodes of each Scotland Street novel already written, but with 50 or so still to write. In pre-pandemic days, he filed these from all over the world, and although he never missed a deadline, there were times – like when his email link went down on a cruise round Cape Horn – when I wondered whether I would have to step into the breach and write an episode of my own. Fortunately for his readers, it never came to that.

Sandy hadn’t arrived at that Witchery meeting with a firm idea of what characters he wanted to write about, but he knew exactly where they lived. He himself had once stayed near Scotland Street, so he knew the New Town well, loved its charm, variety, and realised he could have fun with its occasional pretensions.

Let’s pause here and imagine that you or I had to choose the characters for a series novel set in Edinburgh’s New Town. My guess is that we’d aim for a rough sociological mirroring for our fiction. And why not?

Yet look again at the dramatic personae in The Promise of Ankles. For a start it’s called that because a small part of it takes place inside the mind of a dog tempted to nip the ankles of his master’s friend. The main character? Bertie, a seven-year-old boy breaking away from his hothousing mother. His gran? A Glasgow pie shop owner. His neighbour? A socialite Italian nun who speaks almost entirely in aphorisms. Hardly New Town stereotypes, any of them.

Yet at the same time, the Scotland Street novels aren’t just untethered comic whirligigs either. McCall Smith might write about absurd situations – infighting within the Moray Place-based Association of Scottish Nudists, for example – but there is never anything cruel about his comedy. Instead, he is a celebrant of the good things in life – friendship, art, wit, kindness, comedy and above all a profound love of both Edinburgh and Scotland, an emotion which also finds expression in his just-published debut poetry collection, In a Time of Distance (Polygon, £12.99).

What kind of story would we tell in our own putative Edinburgh serial novel? Again, I fear we’d get that wrong and, seduced by tartan noir, contemplate a thriller or a crime novel, failing to realise that the serial novel can’t really handle anything with a particularly complicated or convoluted plot. McCall Smith, whose own tastes run to the shrewd, slow-building comedies of Barbara Pym, intuitively realised that something similar could easily be adopted to serial fiction. Just as Armistead Maupin centred his tales on 28 Barbary Lane, on San Francisco’s Russian Hill, so he himself could base an enjoyable Edinburgh comedy of manners around a New Town stairwell, and that if the characters were sufficiently interesting or different, we would happily follow their interactions in subsequent volumes.

So now we’re onto book 14 in a series that that has already won the hearts of readers throughout the world. In McCall Smith’s new novel, they’ll discover that seven-year-old Bertie finally gets to live in the Promised Land (Glasgow), just as his father’s budding romance is stymied by the narcissistic Bruce Anderson (not a real villain but the nearest we get to one here). But though we read on to find out what happens to the characters, the real charm of 44 Scotland Street lies in the sometimes surreal unpredictability of the other stories McCall Smith will add to the mix. The chapter headings hint at their range. ‘Rhododendrons and Missionaries’. ‘Bruchan Lom’. ‘Akratic Action’. ‘A Speluncean Entrance.’ I’ll explain one of them and you’ll see what I mean.

Speluncean means ‘like a cave’, and when two characters go exploring by the Water of Leith near Stockbridge with Cyril (the titular ankle-tempted dog), the latter roots around in a shallow cave and comes up with what looks suspiciously like a human skull. Except it’s shaped differently, like a Neanderthal one. This discovery could rewrite archaeology, because Neanderthals hadn’t hitherto been known to venture this far north. Could Cyril have inadvertently proved that the New Town was Neanderthal before it was either new or a town?

I’ll leave you to find that out for yourself. But here’s the odd thing. A couple of weeks after I edited that chapter, I read a story in a newspaper about the discovery of 120,000-year-old stones thought to be Neanderthal tools on an island off Denmark. Because the earliest human remains in Denmark – as in Scotland – only go back 14,000 years and there was no evidence of Neanderthals so far north, this is thought to be a potentially significant find. So if, in the future, anyone ever does find proof that Neanderthals did make it as far as Edinburgh’s New Town – a couple of hundred miles further north than their remains have ever been recorded, but on the same line of latitude as that Danish island – it will be only fair to point out that McCall Smith got there first. And if Homo McCall Smithiensis turns out to have had an exceptionally large brain and well-developed smile muscles, I won’t be at all surprised.

A Promise of Ankles, by Alexander McCall Smith is published by Polygon, priced £17.99.

The Common Breath are an exciting new publisher releasing excellent books and creating a wonderful literary community. Their latest publication is The Middle of a Sentence, short stories from a wide-ranging collection of up-and-coming and established writers. Here we share two stories from Ruskin Smith and Jenni Fagan.

Stories taken from The Middle of a Sentence

Edited and published by The Common Breath

‘Outside’

By Ruskin Smith

She came towards me all in white—white jeans, a thin-looking white top—hugging herself as if the air was cold although it wasn’t, it was warm, it had been warm all day and even now the birds were chirping in the trees around the wasteground as she walked beneath them veering side-to-side a bit. Her shoes were deep white platform soles but big for her—one foot kept slipping off and she was crying now, or sort of crying, words I couldn’t understand, or whether they were words or groans and as she went to turn—the wall curves round, a slope towards a path behind the baths—she doubled over, stumbled to one side and whacked her temple on the wall. She went down slowly to her knees and made a noise and curled up with her forehead on the pavement. I had no phone on me, and no-one else was in the street. I looked around at all the flats, the windows, hundreds of them—glass, reflected glass, reflected sky. Nothing. She made a noise as if something had struck her in the gut. If anyone turned up they might think I was here involved, my bag of beer and ice-cream dangling, when I was only walking back from Co-op. If I left her she might not be safe—the things you heard about from time to time that happened on the wasteground, in the news. I squatted down beside her—Do you need a taxi home or anything?

She crawled sideways into the wall and all the broken bottles there, scraping her face. I stepped away to breathe and turn my back. She turned her face to yell at me—Jamie’s gone, I think it was. Her rows of teeth were very straight and white and too wide for her mouth, and as she shouted it her face had seemed to shrink around them. Then she curled up in a ball again, her hands in front of her now like a yoga pose. Her handbag, plastic and transparent, like a child’s toy, was on the concrete there in front of her, a fiver and some coins and lipstick I could see.

Jamie’s gone, she yelled into the ground, as if realising it for the first time. A woman walked by on the other side but in a rush, and talking on her phone, not noticing.

The ice-cream would be going soft. My beer was probably getting warm. She had gone quiet again. If I turned my back and stood for a few seconds I could almost think she wasn’t there at all—it was so still, the evening, a perfect night for walking outside in your tshirt, all the birdsong going on and on.

‘Ida Keeps Falling’

By Jenni Fagan

She is to be awake throughout the entire procedure. They’ll slice the top of her head open, saw through the bone (make it like an attic hatch — so they can peer in) and she was told to bring a friend.

– It’s important you chat to someone through the procedure, so we can see which areas of the brain light up.

– This will help you diagnose why I’m falling over all the time?

– Yes, we hope so.

All they know so far is that it is not a cancer, nor a tumour, she’s had a CAT scan, been to oncology, it is not Meniere’s disease, nor is it benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, no acoustic neroma, no vestibular neuritis, no herpes zoster oticus. Inner ear fine.

– This will be worth it, Ida, if it means you stop falling over.

It’s not possible to nod in agreement so Ida blinks. Her friend blinks back and they are smiling then. It will be. It’s so awkward, falling over in front of everyone, in the office, the water cooler shaking, bruises, arnica, staying home more and more. There is a tugging above her, then the surgeons fall momentarily silent.

– Well, Ida, we appear to have found the problem — the reason, for your balance issues.

– What is it?

– It’s a little man, bout as big as your pinky nail.

– What?

– Yup, tiny little thing he is, and he’s drunk, on a bicycle, cycling round and around.

– Okay — so, what do we do with him?

-Well, with your permission, Ida, we’d like to cut him out.

Signing a form then, a disclaimer, a dizziness and the surgeons working quickly so the anaesthesia does not wear off and wondering what he’ll look like, if they’ll let her take him home in a jar.

The Middle of a Sentence, edited and published by The Common Breath, priced £8.00

London, the third in the Adventures of Captain Bobo children’s picture book series is published early next year. Set on a famous paddle steamer the series has also recently been made into a Fun Kids radio series, narrated by the late, great, John Sessions. Author, Richard Dikstra tells BooksfromScotland more about the magical world of paddler steamers, missing elephants, crafty seagulls, mysterious tigers, shipwrecks and a quirky comic crew always ready to help save the day.

The Adventures of Captain Bobo

By R. D. Dikstra & Kay Hutchison

Illustrated by Matt Rowe

Published by Belle Kids

Somewhat unbelievably the series is inspired by real-life. A few years ago, we helped one of the Clyde’s best-known captains, Capt Robin L Hutchison, publish a memoir of his many years at sea. Hurricane Hutch’s Top 10 Ships of the Clyde was as much a social history, as it was about his story and the ships he sailed. Forget tonnages, timetables and cylinder capacities, his book was full of stories about the characters he worked with and the passengers that travelled on board – animals, as well as people! Funny stories, unusual incidents and many references to the ways things were done in an analogue age.

Kate and I always thought that some of the stories might also make the basis for a great children’s series – Ivor the Engine meets Para Handy, with perhaps a wee touch of Katie Morag thrown in. It’s no coincidence that Red Gauntlet, the paddle steamer in the series, bears a remarkable resemblance to the Waverley – the world’s last ‘ocean-going’ paddle steamer. It was a ship that Captain ‘Hurricane Hutch’ knew well.

Bananas! – the first book in the series opens with Captain Bobo and the crew facing an uncertain future. The big car ferries have taken over and no one seems to want a wonderful old paddle steamer anymore! But fate, and a lost elephant, prove otherwise. The books are beautifully illustrated by Matt Rowe, whose style brings a real charm and warmth to the series. The stories are about inter-generational friendship, teamwork and a celebration of our unique coastal communities. In London, Captain Bobo and the crew find their annual ‘Round Britain’ trip disrupted when Tower Bridge fails to open. It’s left to Emma, the Apprentice Engineer to come up with an idea to ‘save the day’.

This autumn the series was adapted for radio. A 10-part series, narrated by John Sessions, initially premiered on Fun Kids Radio – the UK’s only national children’s radio station. It’s also available in Gaelic, narrated by Gillebride MacMillan, thanks to support from the Gaelic Books Council, and the English and Gaelic versions are being carried on numerous local and community stations across Scotland. It’s also being broadcast in Nova Scotia in both English and Gaelic.

The series is set in the modern world, but its slower pace reflects a brighter, more optimistic time. It’s a world of brass bands, lost teddy bears, shy puffins, fluffy sheep, missing dinosaurs, cream buns, mountain railways and Welsh teas.

John Sessions

John loved Captain Bobo. We were so lucky he wanted to do the series. We were recording the audiobook of Hurricane Hutch with Bill Paterson, when he suggested John as ‘storyteller’ for Captain Bobo. He knew John would be just right – with a lightness of touch and a talent for character voices like no other. John was also a real enthusiast for the Clyde. He was born in Largs and, although he moved to England at an earlier age, was a frequent visitor to the Clyde and was often a passenger on the ‘steamers’. His favourite ship was the Duchess of Hamilton, but he’d also been on the Waverley many times.

Most well-known for his impressions, and his work on ground-breaking shows such as Whose Line is it Anyway, Spitting Image and Stellar Street, John also appeared in a great number of films and television dramas, playing a range of roles, including two Prime Ministers, Harold Wilson (Made in Dagenham) and Edward Heath (The Iron Lady).

John was great to work with and very keen to help us promote the radio series, telling Radio Scotland’s The Afternoon Show recently they were ‘Lovely, lovely, sweet wee stories.’

With illustrations from the book, here is the first episode of the series Bananas! with John storytelling.

We have just completed the final episode. Captain Bobo was the last project John worked on and he died the day before he was due in the studio with Kay to record a podcast about his career and his love of the Clyde. When they were setting up the date he said to Kay, “If only life could be more like Captain Bobo.”

He will be sorely missed.

The Adventures of Captain Bobo: London by R. D. Dikstra & Kay Hutchison, and illustrated by Matt Rowe is published by Belle Kids, priced £7.99

When the Independent says ‘call off the search – we’ve found the new Terry Pratchett’, then we’re talking about a comic writer worth your attention. And in a year where humour has been much needed then – if you haven’t already – we suggest you should make your acquaintance with Barry Hutchison and his Space Team series. Luckily, we have an extract from the first in the series right here, right now . . .

Extract taken from Space Team

By Barry Hutchison

Published by Zertex Media

Cal Carver’s last day on Earth started badly, improved momentarily, then rapidly went downhill. It began with him being sentenced to two years in prison, and ended with the annihilation of two thirds of the human race. Somewhere in between, there was a somewhat enjoyable moment when he ate a lemon drop, but otherwise it was a pretty grim twenty-four hours all round.

The sentencing was harsh, but not particularly surprising. It wasn’t Cal’s first offense and, if he were honest, almost certainly wouldn’t be his last.

It was far from his first prison sentence, either, although usually they were dished out in terms of days, rather than years. Still, two years – half, once his impeccable behavior was accounted for – in a cozy open prison would be an opportunity to recharge. A holiday, almost. In some ways, Cal was even looking forward to it. There was just one problem.

‘What do you mean, “the wrong prison”?’

Cal flashed the warden one of his most winning smiles.

He had a number of them at his disposal, and this one was up there with the best, while still holding enough back in reserve to step it up to the next level, if required.

‘I literally do not know another way of saying it,’ Cal said. ‘This is the wrong prison. I’m supposed to be in Highvue – you know, upstate? With the gardens? They’ve got this training kitchen. The chefs there, they do these amazing little sort of pastry whirl things that—’

‘I know of it,’ the warden said, drumming his fingers on one of the few uncluttered patches of desk he had available.

‘Good. Right. Of course you do,’ said Cal. He waited, cranking his smile up a notch to be on the safe side. It was a smile so dazzling, you could practically hear the ding as the light reflected off his teeth. The warden, however, appeared unmoved.

He shrugged. ‘And? What’s your point?’

‘Well, Warden… Grant, was it?’

The warden didn’t do anything to confirm or deny his name, so Cal continued. ‘I’m supposed to be at Highvue. That’s what the judge said. Someone even wrote it down on that document this guard here was kind enough to look out for me.’

He gave the female guard an appreciative nod and a flash of that smile. A blush flushed upwards from the neck of the woman’s shirt, but she managed, to her immense relief, not to giggle.

‘He’s right, sir. Must’ve been a mix-up during transit.’

‘She’s really very good,’ said Cal, gesturing to the guard.

‘I don’t know how it works here, if you take recommendations for promotion or whatever, but if you do I’d be happy – no, I’d be more than happy to—’

‘We don’t,’ said the warden.

‘Oh. Well maybe you should,’ Cal suggested. The warden held his gaze for several excruciating seconds. Cal cleared his throat. ‘I’m going to just let you read that.’

The warden’s stare lingered for a while longer, then he lowered his eyes to the document in front of him. A single crooked finger tapped the desktop as he read, the nicotine-stained nail tic-tic-ticking against the wood.

‘As you can see, my crime – while obviously wrong – wasn’t really all that serious.’

The warden didn’t look up. ‘Identity theft is very serious, Mr Carver.’

‘I didn’t steal it, not really. I borrowed it. Just for a while.’

The warden raised his eyes just long enough to make Cal shut up, then went back to reading.

Cal rocked on his heels and studied the office. It must once have been pretty grand, with its wood-paneled walls, high ceiling and lush carpet, but time and a distinct lack of storage space had taken their toll.

The walls were almost completely concealed by mismatched metal shelving. The shelves themselves groaned under the weight of ramshackle ring binders and bulging box files that looked fit to explode and shower the room with their contents at any moment.

Around half of the carpet was as good as new, but a number of paths had been worn into it. The thinnest, most threadbare of them all terminated right on the spot where Cal now stood. He met the guard’s eye and smiled at her. Despite herself, she smiled back, then fought to straighten her face before the warden looked up again.