If you’ve not yet been lucky enough to sample the delicious food at The Seafood Shack in Ullapool, then, with their new book, you can try your hand at recreating their recipes yourself. What a treat! And if you’re looking to cook something a little different for this year’s Christmas dinner, then the recipes below are a fabulous place to start. Our mouths are watering already!

The Seafood Shack

By Kirsty Scobie and Fenella Renwick

Published by Kitchen Press

Pan-fried Half Lobster with Parsley and Chive Butter

Once you have cooked the lobsters this is actually a pretty simple recipe, but don’t underestimate it. Keeping it simple can be key to making something delicious.

Serves 4

Ingredients

2 cooked lobsters, submerged into cold water straight after cooking

150g butter, chopped into chunks

a small handful of chives, chopped

a small handful of parsley, chopped

juice of 1⁄2 lemon

salt and pepper

Halve your lobsters and break off the legs and claws. Crack the claws, but don’t take the meat out of them. Place your butter and herbs in a large frying pan (don’t use a non-stick one as the shells can scratch it and ruin the surface) and put on a high heat. Once your butter starts to foam, put in your lobsters, claws and legs – if you don’t have a big pan you may have to do this in two batches.

Fry your lobsters for around five minutes, constantly turning them in the herby butter as you go, then add the lemon juice and season. Take off the heat and serve. Be extra careful you don’t overcook your lobsters as they become rubbery very quickly.

TIP: You can tell when a lobster is overcooking if the meat of the body starts to curl out of the shell.

Dauphinoise Potatoes

Creamy, cheesy and garlicky potatoes – what more do you want? This is the dirtiest dauphinoise recipe we know.

Serves 4

Ingredients

1kg white potatoes (or you can use a mixture of sweet potatoes and white)

knob of butter

2 white onions, sliced

3 garlic cloves, chopped

1 vegetable stock cube, crumbled

sprinkle of nutmeg

300–500ml double cream

100g Parmesan, grated

salt and pepper

Preheat the oven to 180°C. Peel and slice your potatoes very thin and dry them with a clean tea towel or kitchen roll. Melt your butter in a pan and add your onions and garlic, then sweat for 10 to 15 minutes until they are soft. Crumble in your vegetable stock and the nutmeg and season, then fry off for another five minutes. Stir in the potatoes and pour over enough cream to just cover, then season with salt and pepper. Bring up to just before the boil – you don’t want your cream to boil as it will curdle – then lower the heat and simmer until the potatoes are just tender.

Pour everything into an ovenproof dish (we use the same pan that we cooked the potatoes in to save washing up but make sure it’s ovenproof). Give it a shake so the potatoes are reasonably level on top, sprinkle over the Parmesan and pop in the oven. Cook for around 20 minutes or until the parmesan is crispy and golden. Right at the end, you can whack the heat up to 220°C to brown the top.

TIP: You can use ground nutmeg but you get so much more flavour by grating a whole one (and they keep forever).

Sweet Roasted Root Veg

This is a great recipe to do when you’ve got a fridge full of vegetables that need used up. You can substitute the veg for anything you want, just make sure to adjust your cooking times – for example, if you’re using broccoli, put it in near the end as it cooks a lot quicker than carrots. Sometimes we add a handful of toasted flaked almonds at the end for a bit of extra crunch.

Serves 4

Ingredients

2 raw beetroot, peeled

1 butternut squash, skin left on, seeds discarded

1 red pepper, deseeded

2 red onions

1 carrot, scrubbed

2 garlic cloves, skin left on and crushed

good glug of olive oil

2 tbsp balsamic vinegar

2 tbsp honey

4 handfuls of baby spinach

100g feta, crumbled

salt and pepper

Preheat the oven to 200°C. Cut your beetroot, squash, red pepper, red onions and carrot into roughly the same sized chunks so they cook in the same time. Put them all on a large baking tray in a single layer and toss with the garlic and a good glug of olive oil. Season well.

Roast in the oven for around 20–30 minutes until the veg is just starting to soften but still has a good crunch. Take out of the oven and drizzle over the balsamic vinegar and honey, tossing

to make sure all the vegetables are well coated. Then whack up the heat to 220°C and pop the tray back in for another 15 minutes until everything is tender and caramelised but not soggy.

Take your veg out, mix through the spinach and feta, and serve immediately.

The Seafood Shack by Kirsty Scobie and Fenella Renwick is published by Kitchen Press, priced £20.00.

The dark, winter nights are the perfect time to curl up with a thriller, and BooksfromScotland highly recommend C. J. Cooke’s latest book, The Nesting. It’s a domestic noir that sees a vulnerable young woman start a job as a nanny with a grieving family as they set up in their new home in the Norwegian countryside. In this extract Lexi meets the family for the first time . . .

Extract taken from The Nesting

By C. J. Cooke

Published by HarperCollins

The room was suddenly charged with emotion, and I felt my lies pressing down on me like lead weights. But just then, Coco reached out to me, both her hands open wide. Tom passed her to me and I took her, feeling the lovely warmth of her in my arms. I swear, I’ve never been remotely maternal or gooey over other people’s kids – quite the opposite, especially during the drool stage – but there was something different about Coco and Gaia. Or maybe I just related to their loss.

*

‘Shall I let you spend some time with the girls?’ Tom asked me. ‘Ellen can fill you in on their routines.’

The urge to run out of there screaming was starting to wane. I was on surer territory, now, especially since I felt so comfortable around Gaia and Coco. It almost felt like I’d known them much longer than three minutes.

Serendipity. That’s what it felt like.

Tom left me and Ellen to chat while Gaia and Coco Cooke played in the nursery. Ellen told me she’d worked for Tom for just two and a half months, but she was getting married and couldn’t go to Norway. I could see she’d been torn about this and it was clear she loved the girls.

‘So you didn’t know their mother?’ I said, calculating the length of time Ellen said she’d been in the post and the length of time it had been since Aurelia died.

Ellen shook her head. ‘No. It’s clear that they were devastated, though they’re so young that it takes a long time to process something like that, losing your mother . . .’ She paused briefly. ‘It was one of the reasons Tom wanted me to nanny for him, while he tried to keep his business going and get his head around it all. I’ve had child counselling training, you see.’ She glanced over at Gaia who was playing with an enormous dolls’ house. ‘They’re doing much, much better now, though Gaia still asks questions. Just so you know, if she asks what happened, the party line is: Mummy had an accident and is in heaven.’

I nodded, though the phrasing made me unsettled. ‘An accident?’ I said cautiously.

Ellen dropped her gaze to the floor. ‘Suicide,’ she said in a low voice. ‘Terrible, isn’t it? What would drive someone to do something like that?’

The scabs on my arms began to itch beneath my sleeves. ‘Yes,’ I said after a long pause. ‘Terrible.’

I left an hour later, both exhilarated and disgusted with myself. There was no way I could take the job, absolutely no freaking way. I’d be lying to a family who had been utterly devastated by an unthinkable tragedy.

But on the other hand, I wanted to be a part of their lives.

I wanted to go to Norway, yes, and I wanted a home and a chance to write my book and turn my life around. But Gaia and Coco were sweet, precious girls who had lost their mother to something I knew better than I knew myself, and beneath the usual thrumming cacophony of self-hatred in my head was a quiet but insistent whisper that maybe – just maybe – I could actually make a difference.

The Nesting by C. J. Cooke is published by HarperCollins, priced £12.99.

The National Galleries of Scotland’s current exhibition pays tribute to one of cinema’s greatest pioneers, Ray Harryhausen. But if you can’t make it to Edinburgh while the exhibition is on (though it runs until September 2021), you can bask in his life and iconic work in the exhibition’s companion book, Ray Harryhausen: Titan of Cinema. We have a sneaky peek here to share with you, which we’re sure will bring back memories!

Extracts taken from Ray Harrhausen: Titan of Cinema

By Vanessa Harryhausen

Published by National Galleries of Scotland Publishing

Dad’s centenary

My dad, Ray Harryhausen, was known to his fans and moviegoers as a creator of magical creatures, and as the man behind the stop-motion animation technique Dynamation. He astonished and terrified his audiences with swordwielding skeletons, bronze giants and the iconic Kraken from Clash of the Titans. The 100th anniversary of his birth has given me the motivation to record the stories that reveal the kind, funny, fascinating family man behind these creations. With this book, I want to celebrate the fantastic collection of creatures and artworks which sprang from his incredible imagination. These are my own personal memories of this famous man’s life at home, as well as on set. Often, some of the people who knew him as a friend, colleague or mentor add their own revealing memories.

I so admire all of Dad’s achievements, and am proud to see what a legacy he has left. It’s exciting to see that people are still fascinated by Dad’s work, more than seventy years after he first animated for a major film. I still feel that what he created on screen was magical – from the initial seed of an idea in a drawing that sprang from his huge imagination to building a model which he then brought to life through animation. I had the opportunity of watching him create concept sketches and then construct the model at home. The creatures all had very strong personalities – Dad was always able to create such distinctive characters.

There are sixteen classic films that Dad worked on throughout his career; I was around for five of these, from One Million Years BC (1966) until his final movie, Clash of the Titans (1981). I was fortunate to be present on many of Dad’s film sets as a child, and mingled with the famous actors and crew who worked with him.

Once animation on the films had been completed, Dad would allow me to play, from an early age, with the very models that had been seen on screen. Our house was filled with items from Dad’s films, and so alongside my regular childhood toys, I was able to have fun with dinosaurs and other creatures – this was the norm for me. We also had some interesting reading material – Dad’s good friend Forrest J. Ackerman, the science-fiction writer and publisher, would send over copies of Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine, which we would read over breakfast, much to Mum’s disapproval. She just didn’t think it was right to have such gruesome reading material at the breakfast table!

Skeleton model from The 7th Voyage of Sinbad

Of all Dad’s creations, it is the skeletons which are most frequently remembered by film fans.

Even though The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) was before my time, the fight scene between Sinbad and the skeleton on a spiral staircase is particularly special to me.

The choreography for this sequence was incredible. I have been lucky enough to practise some basic swordplay with Scottish battle re-enactors in the past, and so appreciate the level of concentration and timing required by the actor Kerwin Mathews in this scene. Mathews would spend hours and hours rehearsing his movements with the stuntman Enzo Musumeci Greco; then, when it came to shooting the live-action sequences, Mathews would be alone, fighting his invisible foe. Of course, Dad then animated the skeleton model to match with Mathews’ movements, and the end sequence was brought to life by Bernard Herrmann’s score.

This sequence was so successful that Dad decided to use skeletons in his 1963 film Jason and the Argonauts. This original skeleton was reused, as well as six additional models. For many years, Dad claimed that he had forgotten which of his skeletons the original from 1958 was. However, as we prepared for our exhibition at the Oklahoma Science Museum, our conservator Alan Friswell realised that this particular model was the original, after some close examination. We decided that he should be reunited with his 1958 sword and shield, just in time for the film’s sixtieth anniversary.

Director John Landis on The 7th Voyage of Sinbad

A Hollywood producer once said: ‘Those who make movies are in the transportation business.’ That exactly describes my first encounter with the work of Ray Harryhausen – I was transported!

The eight-year-old me was no longer sitting in my seat at the Crest Theater in Westwood, LA: I was on the beach of the island of Colossa, and as awe-struck and fearful as Sinbad and his crew when the first Cyclops made his appearance. I was spellbound by Sinbad’s adventures, and marvelled at the Cyclops, the two-headed Roc, the fire-breathing dragon and the skeleton brought to life by the evil magician Sokurah. Only later did I learn that these extraordinary beasts were really brought to life by the magician Ray Harryhausen.

The 7th Voyage of Sinbad was a truly life-changing experience for me. Thrilled by the movie, I went home and asked my mother: ‘Who does that? Who makes the movie?’ She replied: ‘Well, a lot of people, honey, but I guess the right answer is the director.’

And that was that: I would be a director when I grew up. All of my energy went into that goal, and I read everything about film that I could get my hands on.

Minaton model from Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger

The character of Minaton saw one of the rare occasions that Dad alternated between a stop-motion model and an actor in a resin suit. In this case, the actor was the 7-foot 3-inch hospital porter Peter Mayhew, who would go on to appear as Chewbacca in the Star Wars movies. This was his first film role, after Charles Schneer saw an article in a local paper about a particularly tall man with large feet. Everybody who worked with him said that he was a very gentle, kind man. When I met with his co-star, Kurt Christian, he said that he rarely complained during filming, despite the fact that he was in such an uncomfortable suit in the baking sun.

I thought that Minaton was a tremendous character – he looked as though he had been constructed from bronze, and I love the dramatic scene where Margaret Whiting’s character Zenobia brings the creature to life. I remember meeting Margaret on set – I thought she was lovely, and fantastic as the female villain in Dad’s third Sinbad film.

Dad asked me to take care of the Minaton’s head that Peter Mayhew had worn for the role, many years after the film had been released. I lived in Scotland by this time, and our estate had a little more wall space than Dad’s house in London. He suggested that I mount the head like a hunting trophy, and display it alongside the stag heads, swords and targes that were up on the wall already. The head is made of fibreglass, and so is not particularly heavy – however, there are no holes for air or sight, and so I can’t imagine what it would have been like to wear on location. Thankfully, I don’t think Peter had to wear it for long.

Medusa model from Clash of the Titans

This is one of Dad’s most complicated stop-motion models. I remember him creating a key drawing of Medusa on his easel in his workshop at home – I returned home from boarding school just in time to see the artwork being finished. At the time, Dad was debating whether to include a ‘boob-tube’; he was concerned about American censors raising objections to a topless Medusa, regardless of the fact that she was a reptilian creature. In the end, it was decided that the garment should be removed; Dad felt that this allowed for a more authentic and effective Medusa.

I was on set during the filming of the live action for Medusa at Pinewood Studios near London, and remember the sequence where Medusa’s arrows were taking out Perseus’ companions, one by one. The scene where a supporting actor receives an arrow to the back and falls face down into a pool of water in Medusa’s temple required multiple reshoots, and I recall feeling very sorry for the actor, who was repeatedly dunked into the somewhat murky water!

Photographing Medusa, by Andy Johnson

I was captivated by the model of Medusa, which I vividly remembered from Clash of the Titans (1981). It was quite scary as I recall, but here I was carrying the piece to set up for photography. We were going to ask Ray to stand behind Medusa and move her as if he was working on a film sequence. I was so concerned that this fragile model would come apart or be damaged, but Ray began to move the various articulated joints through their sequences, and all seemed fine. We wanted to create a small sequence of movements to emulate the way it was photographed for the film, twenty-four images in a second. It was at this time that I fully realised how difficult it must have been; there were a dozen or so snakes on her head to manipulate, the arms, facial expressions, tail; and all the while, keeping them all moving in the correct direction – quite unbelievable.

Colin Arthur on Clash of the Titans

Ray and I worked together on Clash of the Titans. Again, he produced a waterfall of inspired drawings and visited my studio while I sculpted the Kraken and made some full-sized two-headed wolves. With the Kraken completed and in store, and an assistant finishing the wolves, I went off to shoot a Burt Lancaster film. But soon, calls came in looking for the Kraken for shooting in Rome. I loaded all Ray’s monsters, the Kraken and my tools into my Winnebago and drove to Rome. A mammoth trip in a very short time, leaving on Saturday and arriving in Rome on the Monday – Ray had summoned me!

As shooting drew to an end, we began to plan the make-up for the character Calibos, with his goat’s legs. I was keen to do the whole sequence for real with an actor and prosthetic goat’s legs, but in the end Ray decided to stay with stop-motion, and I did the close-ups. We were working on a very tight timescale, and we had little time to do the finishing work. Thank goodness for the wonderful Ted Moore, our lighting cameraman – Ted would say ‘no problem’ and, with subtle shadows and clever lighting, make things better than I had dreamed possible.

Ray was always there too and was concerned about the mix of techniques that were involved, but in the end we had a relaxed shoot. When the film was released, Ray came to me and admitted that the goat’s legs would have been more interesting with prosthetics and not stop-motion – but that was the way of our work, constantly breaking new ground, using unknown and unconventional materials, trying new ideas.

Alas, Ray’s next project never came to pass, and the technology changed into real-time special effects, then CGI and Star Wars, and the world changed for us. It was time to bow out graciously.

It also meant that I could then be in the UK, spend time with Ray, and indirectly give a small amount of support to the Harryhausen Foundation – what a pleasure to spend time with him, an old comrade and so much more than just a friend.

Ray Harrhausen: Titan of Cinema by Vanessa Harryhausen is published by National Galleries of Scotland Publishing, priced £27.95.

October is Black History Month and BooksfromScotland would like to take the opportunity to highlight books from Scotland’s publishers and writers that teach us of important people, places and stories as well as celebrate the writing talent working today. We’ve chosen a mixture of history, novels, biography and graphic novels to recommend to you, something for every reading appetite.

If I Survive: Frederick Douglass and Family in the Walter O. Evans Collection

If I Survive: Frederick Douglass and Family in the Walter O. Evans Collection

Edited by Celeste-Marie Bernier, Andrew Taylor

Published by Edinburgh University Press

Frederick Douglass – autobiographer, orator, abolitionist, reformer, philosopher and statesman – is a giant of world history. This collection of previously unpublished speeches, letters, autobiographies and photographs sheds light on the private life of Douglass as a family man. All of life can be found within these pages: romance, hope, despair, love, life, death, war, protest, politics, art, and friendship. Working together and against a changing backdrop of US slavery, Civil War and Reconstruction, the Douglass family fought for a new ‘dawn of freedom’.

Freedom Bound

By Warren Pleece and Shazleen Kha

Published by BHP Comics

Warren Pleece’s graphic novel, Freedom Bound, follows the interconnected stories of three enslaved people living in Scotland before Scots Law proved slavery illegal. From mountainous countryside to the inner city, Freedom Bound explores Scotland’s unsettling history of slavery and the injustices perpetrated through the decades.

Recovering Scotland’s Slavery Past: The Caribbean Connection

Recovering Scotland’s Slavery Past: The Caribbean Connection

Edited by Tom M. Devine

Published by Edinburgh University Press

For more than a century the real story of Scotland’s connections to transatlantic slavery has been lost to history and shrouded in myth. The essays in this book are a major contribution to understanding Scotland’s history with the transatlantic slave trade, and cover topics as wide-ranging as national amnesia and slavery, the impact of profits from slavery on Scotland, Scots in the Caribbean sugar islands, compensation paid to Scottish owners when slavery was abolished, domestic controversies on the slave trade, the role of Scots in slave trading from English ports and much more.

The Lamplighter

The Lamplighter

By Jackie Kay

Published by Picador

In The Lamplighter award-winning poet and Scottish Makar Jackie Kay takes us on a journey into the dark heart of Britain’s legacy in the slave trade.

Constance has witnessed the sale of her own child; Mary has been beaten to an inch of her life; Black Harriot has been forced to sell her body; and our lead, the Lamplighter, was sold twice into slavery from the ports in Bristol.

Stirring, impassioned and deeply affecting, The Lamplighter remains as essential today as the day it was first performed. This is an essential work by one of our most beloved writers.

The Shadow King

The Shadow King

By Maaga Mengiste

Published by Canongate

SHORTLISTED FOR THE BOOKER PRIZE FOR FICTION 2020

ETHIOPIA. 1935.

As Mussolini’s army marches into the country and Emperor Haile Selassie goes into exile, recently orphaned Hirut struggles to adapt to her new life as a maid. She helps disguise a gentle peasant as the emperor and soon becomes his guard, inspiring other women to take up arms. But how could she have predicted her own personal war, still to come, as a prisoner of one of Italy’s most vicious officers?

The Shadow King is a gripping, gorgeously crafted novel exploring female power, and what it means to be a woman at war.

Louis Armstrong

Louis Armstrong

By Stéphane Ollivier, Illustrated by Illustrated by Rémi Courgeon

Published by Moonlight Publishing

This beautifully illustrated biography for children tells the life of Louis Armstrong, the greatest jazz musician and singer of his age, and gives an introduction to his music. On the accompanying CD, the narrative of the book is interwoven with 14 of Armstrong’s most famous recordings.

Also in this First Discovery Music series is Ella Fitzgerald and Ray Charles.

Stay With Me

Stay With Me

By Ayobami Adebayo

Published by Canongate

SHORTLISTED FOR THE BAILEYS PRIZE FOR FICTION 2017

Yejide is hoping for a miracle, for a child. It is all her husband wants, all her mother-in-law wants, and she has tried everything. But when her relatives insist upon a new wife, it is too much for Yejide to bear.

Unravelling against the social and political turbulence of 1980s Nigeria, Stay With Me is a story of the fragility of married love, the undoing of family, the power of grief, and the all-consuming bonds of motherhood. It is a tale about the desperate attempts we make to save ourselves, and those we love, from heartbreak.

Bad Ass Raindrop

Bad Ass Raindrop

By Kokumo Rocks

Published by Luath Press

Kokumo Rocks is one of Scotland’s greatest performance poets, and her work on the page sings too, alive with love, passion, humour, wisdom and brutal honesty. Kokumo’s poetry explores the themes of love, race, freedom and imprisonment, and she does so with a sense of the importance of fun and humour. In Bad Ass Raindrop, you can hear the monsoon rains of Africa, taste the mangoes of India, touch the compassion and spirit of the child and feel the pain of burning flesh as race riots rage in Scotland.

LOTE

LOTE

By Shola Von Reinhold

Published by Jacaranda Press

With a sharp eye and great wit, Shola Von Reinhold’s decadent queer literary debut immerses readers in the pursuit of aesthetics and beauty, while interrogating the removal and obscurement of Black figures from history.

We follow Mathilda, an art lover and aesthete, long enamoured with the Bright Young Things of the 20s. When she uncovers a forgotten Black Scottish modernist poet, Hermia Drumm, she endeavours to unearth everything she can about her. At the same time, she enrols in an artist residency with a more austere philosophy than hers which leads Mathilda to extravagant, uncovering systems of erasure and realising her own sense of self and beauty.

The Black Flamingo

The Black Flamingo

Dean Atta

Published by Hodder Childrens’ Books

WINNER OF THE STONEWALL BOOK AWARD

SHORTLISTED FOR THE CILIP CARNEGIE MEDAL

SHORTLISTED FOR THE JHALAK BOOK PRIZE

In this brilliant YA novel in verse, a boy comes to terms with his identity as a mixed-race gay teen – then at university he finds his wings as a drag artist, The Black Flamingo. A bold story about the power of embracing your uniqueness. Sometimes, we need to take charge, to stand up wearing pink feathers – to show ourselves to the world in bold colour.

For Every One

For Every One

By Jason Reynolds

Published by 404 Ink, partnered with Knights Of

Originally performed at the Kennedy Center for the unveiling of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, this stirring and inspirational poem is New York Times bestselling author Jason Reynolds’ rallying cry to the dreamers of the world, illustrated by Yinka Ilori.

This book is a challenge to think beyond the expected and go for what you want, when going for it is the scariest part. It’s a one-of-a-kind inspirational book, an ideal gift for anyone from a school leaver to a retiree, for the creative, ambitious or those going on an adventure.

Hadithi and the State of Black Speculative Fiction

Hadithi and the State of Black Speculative Fiction

Edited by Eugen Bacon and Milton Davis

Published by Luna Press Publishing

Hadithi is a book of two parts, first a scholarly dialogue on the global state of black speculative fiction, then a short story collection. It features seven short stories – three original – of ancestry, soul, continuity, discontinuity as well as steampunk, cyberfunk and a dieselfunk superhero story set in the ‘20s. It’s an enticing, illuminating celebration of afrofuturistic diversity, full of adventure, curiosity and brilliant, bold writing.

Maud Sulter

Maud Sulter

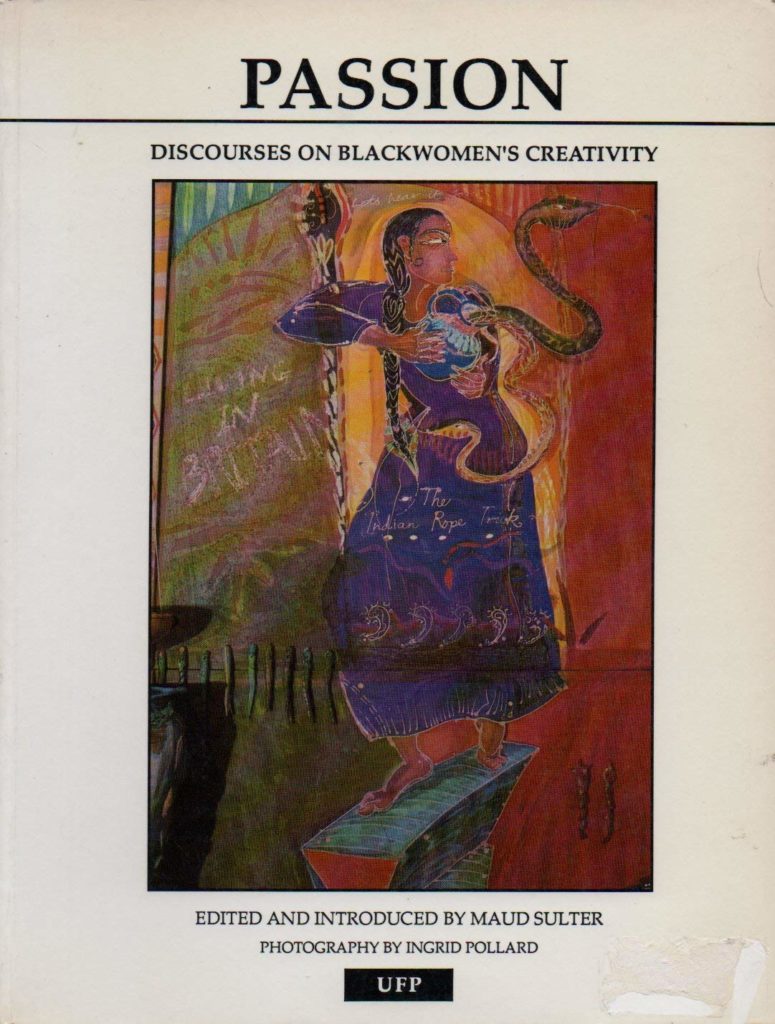

Lastly, we urge you to investigate Maud Sulter (1960–2008). She was an award-winning artist and writer, cultural historian, curator and gallerist of Ghanaian and Scottish heritage who lived and worked in Britain.

Her poem ‘As A Blackwoman’ won the Vera Bell Prize for poetry in 1985. She wrote several collections of poetry, including As A Blackwoman (1985), Zabat: Poetics of A Family Tree (1989) and Sekhmet (2005), and was widely anthologised. She edited and contributed to a pioneering collection of writings and images, Passion: Discourses on Blackwomen’s Creativity (1990). Her books, though they may be hard to find now, are well worth hunting down.

Carrying on our new ‘Introducing . . .’ series, where BooksfromScotland highlight the work of up-and-coming writers, we bring you the poetry of Nasim Rebecca Asl.

Nasim Rebecca Asl is a Geordie-Persian poet and journalist based in Glasgow. Her work has been featured in Skin Deep, Young Poet’s Network and Now Then Magazine, as well as Tapsalteerie’s anthology pamphlet Ceremony. She’s performed her work in cities across Scotland and was featured in Sorry I Was On Mute, part of the inaugural Fringe of Colour Films. She’s an alumna of The Writing Squad and is participating in 2020’s Traverse Young Writers Programme.

A resurrection in north-west Iran (imagined)

Mamanbozorg splits threads in the Caspian sun. We hear again

her rusted tongue speak, weave, paint carpets Persian. Here again,

the lambs she lambed raise their heads at the sound of her song.

Her roosari dances. She calls to a God who answers, and cheers again:

Golgaz. Sweet flowers shed thorns and burst through dry soil to

carpet her feet. Sunlight holds her. She won’t disappear again.

Under a pall of flour she kneads. Births noon and cherry wine.

Saffron, rose and thyme crescendo in her mouth. She feels again,

moves to the city where her children grew with the mountains.

Dusk breaks. She toddles the ninis to the park. Happy tears again.

She crosses the world and wonders if it’s faith keeping the plane

adrift. A runway of stars lead her to us. The skies clear again.

Baba gets a chance to say goodbye but won’t. Not again. She makes

Space for me beside her and says “Nasim, bia inja” -Come here, again.

Glossary

Mamanbozorg Grandma

Roosari headscarf

Golgaz My grandmother’s name

Noon bread

Ninis nini = baby, plus English plural

Baba dad

Bia inja come here

(This poem first appeared in Ceremony, published by Tapsalteerie)

On trying tattie scones for the first time

- Cook the sausages.

You’ll need the scissors for this. Grab them from the cutlery drawer (top left); the ones with the blue handles. Separate the sausages. Say sorry as you split skin from skin. Do not imagine the pain they must be feeling, the sadness of being pressed so close and suddenly torn apart. Be glad you cannot hear them cry as you rip them from their friends.

Close the oven. Forget them, for now.

- Cook the tattie scones.

Bring the hob to life. Savour the lick and the woosh as the fire bursts into being and kisses the back of the pan. Add a generous helping of butter. Tilt. Let it paint the black in liquid gold. Think of holding a buttercup in your once tiny hands and offering it to the smiling face of your mam. Feel the catch in your four-year-old throat when the glow lit her skin.

Liberate potato from packet. Lay down the scone into your pool of sunlight. Use your now grown hands to massage. Paint. Give peace. Wait for the butter to bubble in excitement, and flip – admire the newfound melanin, the honey flower dew of its skin. Wait for the fat to crescendo, to fade. Rescue from the embers.

- Combine the ingredients on the plate.

Bring the sausages into the cold. Ignore their frightened hiss: instead, admire the split in their seams. Build a meal with their bricks. Steal a bite and travel to your first festival, the first-love of your life. Remember the hungover sandwich you paid dearly for; how tomato sauce stained the corner of his lips while the afternoon flushed his cheeks and your makeshift fire danced in his eyes. How he offered you the last bite; how you kissed the ketchup from his skin.

His bloody smile.

- Try your first tattie scone.

Take a photo first, to prove you took your friend’s advice – they’re golden brown. He said this was best. Savour your first bite. Feel the butter seep into your tongue, let the soft starch fill your soul. Enjoy your taste of his childhood. Think unbidden now of his mother, looking out towards the west-coast sea. The islands waving at her through the kitchen window, three boys waiting at the table, a chocolate spaniel circling their feet, and between them all; endless tattie scones.

(This poem was first published in Staying Home, a response to Covid-19 by The Writing Squad)

Becoming

a book spine poem

Touching from a distance

the left hand of God.

The beating of his wings

the forbidden echo burning

a thousand splendid suns.

Tender is the night,

sincerity the noonday demon,

the testaments geography

for the lost. I’d die for you

if they come for us.

Brave new girl, girl, woman,

other: this is going to hurt.

Origami

Imagine dragons and freelance whales,

spiralling past shadow realms and

tumbling into our heavens.

Under the beat of wings and enormity

we’re folding desperate stars with desperate

fingers, bleeding dust through broken skin.

My shaking hands found worlds. Blue cut

crease, turn, twist, repeat. I fill tiny globes

with my own oxygen, breathe sharp edges soft.

Your right eye squints through an eyelash forest.

Checkered sleeves watch from your elbows.

Your hands stroke, coax the paper birds into being,

cracked lips kissing life into the creases of their necks.

Creation blossoms in the corner of your mouth.

Hurtling, we birth an army of cranes.

We release them as oblivion rests

on the horizon. Floating on the edge of our breath

they pass into nebulas and we’re rewarded

with the whisper of a wish.

You can find out more about Nasim’s work by following her on Twitter and Instagram @nasimrasl

Tiger by Polly Clark was one of last year’s most bold novel releases, telling the story from the perspective of both its human and animal characters. Ahead of it’s paperback release, Polly has written a piece on the work she does in the name of research, which is just as bold as her writing!

Tiger

By Polly Clark

Published by riverrun

For my first novel, Larchfield, I spent a lot of time immersed in WH Auden’s work and papers, and wandering his haunts in Helensburgh. I did everything I could to get inside that young poet’s skin, and I thought I had a handle on what research is – a tool, for me, the writer. It was hard work but I was in control of it. It was labour that was in service to the bigger picture of my story.

When I began my second novel, Tiger, about a last dynasty of Siberian tigers, and the people who live alongside them, I knew the research would involve some fairly extreme travel into harsh conditions (11 time zones, -35C, and deep snow) but I didn’t anticipate how it would come to transform the very structure of the book and change my way of understanding the world and my place in it – as both writer and human being.

My expedition was to the remote forests of the Russian Far East where the last 500 Amur (Siberian) tigers roam wild. It might be expected that the aim of the trip was to see one in the wild, but they are so vanishingly rare this is nigh on impossible. A major selling point of the eye-wateringly expensive trip was that you will not see a tiger. We tracked the tigers with expert guides and set camera traps at their favourite spots and collected the footage later. Some in our party secretly believed we would beat the odds and see a tiger. And when the tiger proved just as elusive as we had been told, were very disappointed.

Years ago I was a zoo keeper and I have seen tigers fairly close-up. In an enclosure, away from the forest a tiger seems outlandish and exotic – its stripes, for instance, seem almost anti-camouflage in their vibrancy. The Amur tiger, the largest cat in the world, is more precisely and fully encountered by experiencing its lethally hostile environment, where is camouflage is so perfect that it can be ten metres away and you will never know. Studying its tracks, discovering its recent kill sites, all the time knowing it is watching – this is how you really ‘see’ this creature, the apex predator of an entire continent. The indigenous people of the region, the Udeghe, call the tiger the ‘Lord of the Forest’ and this came to make perfect sense. The trip was a pilgrimage: a journey to encounter a creature you will never see in the flesh.

The transformational experience was therefore not seeing a tiger in the wild – it was something else, completely unexpected, that went on to create the fundamental structure of the novel. It was The White Book. Like most people I had read about the pattern of tracks in the snow, but I did not fully appreciate how meaningful it is until I was in the taiga, with nothing around me except blank snow marked with the ‘narratives’ of animal tracks. These were sometimes intertwined, sometimes parallel, sometimes alone, the totality revealing the incredible variety of life in the winter forest – and how each creature is affected by the decisions of the one before it. A weasel, for instance coming across a mouse’s tracks, will change its direction. Similarly, the tiger, discovering boar tracks, will set off in pursuit, leaving its own trail. The tracks are alongside in space, but not time and in this way the forest floor becomes a vast web of narratives, all interconnected – until a new page of snow makes the ground blank again.

Another astonishing facet of the White Book is that following tracks away from the direction of travel (as you must do with tiger tracks – if the tiger senses you, it will loop round behind you…) is effectively travelling back in time. You can discover the beginning of a creature’s story, follow it through to the end. These two things together – the interconnection of narratives in the snow, along with how tracks bring all times into the present — became the basis for the structure of Tiger, which has four connected storylines which gradually converge. The tiger, which is tracking a bear, links them all. The forest of this novel is not a backdrop, but is the very essence of the book. Tracks in the snow, are quite simply, the most thrilling and profound encounter with nature I have ever experienced. And it taught me that the best research is the kind that takes the writer over, refuses to give its answers in advance, and transforms the work beyond what the writer could have ever imagined.

Visit Polly Clark’s website www.pollyclark.co.uk

Follow Polly Clark on Twitter: @mspollyclark

Watch the book trailer for Tiger:

Tiger by Polly Clark is published by riverrun, priced £8.99

Chris Dolan made his first trip across Spain when he was a teenager, in the footsteps of Laurie Lee. A little bit older and a little bit wiser, he made the same trip, writing of returning, of memories, of art, travel and history. In this extract of his book Everything Passes, Everything Remains, he reminisces about busking the streets and making friends with his fellow musicians.

Extract taken from Everything Passes, Everything Remains

By Chris Dolan

Published by Saraband

When exactly I left Brendan in La Coruña – or he left me to go north to his in-laws in El Ferrol – and I took my violin to begin the vagabond trail in the wake of Laurie Lee, neither of us are sure. I simply remember heading off. First to some of the villages I had already visited with Brian, or Tere, or others. I had never in my life busked before. I was terrified. I also wasn’t very good, which didn’t help. On the other hand, busking wasn’t a thing back then. Now, in Spain as in the UK or anywhere, there are buskers at every corner, the entrance to every tube station. Back then I was a one-off. People stood in astonishment rather than appreciation.

The loneliness of the busker. No one has asked you to play. You’re getting in the way in a public space, a beggar essentially. Aware of your limitations, trying to catch strangers’ attention but not their eye. Hoping for payment but unsure you deserve any. Part of me wanted to be ignored, another craved their approval – and needed their loose change. I had never busked in Scotland, had never met anyone who had. I stood as close to the wall as possible, kept my eye on my fiddle. I felt like a shadow, a smudge on the pavement.

Then passers-by began to throw pesetas into my opened violin case (eventually I learned to put in the first few – silver – ones myself, pour encourager les autres) out of sympathy and concern rather than for having been whisked momentarily to a haven of glorious music. I would usually make just enough to afford the cheapest menú del día in the village, and a night in the most basic pensión.

I didn’t have the adventures, neither the highs nor the lows that Lee had in 1935. Inns in his day sound nineteenth-century in comparison. Bedding down with animals in straw, or in shared barns with entire families. His descriptions of single-room cabins and outhouses, or cheap dormitories in cities, run by drunks and crones and children – it all reads like Dickens. Or Stevenson. David Balfour, lost in the Highlands, taking refuge in black houses and crofts and among the heather. Stevenson wrote Kidnapped in 1886, and set it in 1751, after the turmoil of the Jacobite Rising. So Lee’s accounts sound, in fact, eighteenth-century. Perhaps because he likes to tell a good story and his ‘facts’ are elsewhere dubious, it’s hard not to suspect that he exaggerates his living conditions. But not by much. Spain was poor enough in ‘74, much more so in ‘35. Cut off from Europe by the Pyrenees, exhausted from a century of civil wars (the one in 1936 was far from the first), and another century of thrawn Church and landowners’ conservatism, Lee’s Spain had hardly changed in over a century.

The pensiones I stayed in – and would over the next few years on return journeys – were lugubrious, heavy old furniture, blinds down. There was usually a landlady, usually in her seventies – which back then was shockingly old to me. Almost without exception she’d narrow her eyes, look suspicious, demand payment, or part of it, up front. In every bedroom, hall, and bathroom there were crucifixes, dripping with blood and howling in pain. Stepping inside my room reminded me of going to confession as a child. Closed space, an air of pious anxiety, left alone with sins and penance.

But, just as usually, the old landlady would soon turn out to be kindly, offering you soup a la casera, seldom included in the final bill. If you stayed more than a night she’d even smile, ask you about yourself. You’d open your blinds, let in the light and the noise of the street, meet family and, what appeared initially as some murky house that held terrible secrets, became a family home, into which you were often, temporarily, accepted.

A few times, bar owners who had heard me in the street invited me to play inside, at lunchtime, or in the evening. Reimbursement was a few beers or glasses of wine and a thick, hot caldo gallego – a stew of a few bits of whatever meat was available but mainly cabbage and beans, garlic, onion.

Life was easier now that my Spanish was improving. I could ask for food, beer, accommodation, join in on very basic conversations, explain a little of the background to my songs and tunes. But in Vigo someone from elsewhere in Spain informed me I was talking Gallego. Or rather, the mix of Galician, Spanish and street-talk Brendan I had been unwittingly learning in bars and on Riazor beach. To be absolutely accurate, I was speaking a mix of Gallego, Spanish, street jive, and west coast Scots. (A later version of which a student of mine in Pamplona dubbed escoñol.)

Maybe that’s why I was destined to be The Man Who, unwittingly, Invented Fusion Music. Or at least one half of the duo that invented it. I was in Pontevedra playing my violin on one corner of the main square and some very noisy bongo player was attracting audiences at the other. I can’t remember his name. A young black Brazilian guy. Twice my height, he moved slowly but played fast. After an hour or two he ambled – which implies far too much urgency – up to my pitch. Through his Brazilian-Portuguese-Spanish and my Gallego-Scots we managed to negotiate.

‘Oi, Branquinho. Vamos a play juntos, yeah?’

Hoy, wee white man. Let’s play together.

I’ve since gotten to know the music of Milton Nascimento and now, in my head, that bongo player is called Milton. Milton’s thinking was right. We more than doubled our individual audiences. No wonder. The sound we made drew people from streets away. I’m playing the Irish Washerwoman and Milton is pulsing out a spliff-saturated slow samba. I switch to ‘My Love Is Like A Red Red Rose’, bowing with all the soul and misty romance I could muster, and Milton whacks hell out of his drums in some complex war cry.

Everything Passes, Everything Remains by Chris Dolan is published by Saraband, priced £9.99.

Gavin Francis is an adventurer and has written of his travels in his excellent Empire Antarctica and True North. His new book, Island Dreams explores our fascination with islands, and we caught up with him to chat about another fascination – books.

Island Dreams: Mapping an Obsession

By Gavin Francis

Published by Canongate

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

Where The Wild Things Are, with my mum – doesn’t everyone dream of being able to sail off to an island world, have dramas and high risk adventures, but be home in time for supper?

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest book Island Dreams. Is there something in particular you’re setting out to explore?

The allure of isolated places – from Greenland to Antarctica, from the Galapagos to the Andaman Islands, has long animated my travels and my choices in life. But so has the city and all of its possibilities for connection and cross-fertilisation of ideas. My profession for the last twenty years has been medicine and there’s no better work for someone fascinated by what connects people in all their diversity. But I’ve also worked as an expedition doctor in some of the most remote parts of the planet, and as a nature warden on island bird reserves in Scotland. And so I wanted to write a book that mapped the tension, the creative tension, between those extremes: island and city, isolation and connection. And along the way exploring the rich history of island literature.

The book as . . . object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

The Renaissance anatomist Andreas Vesalius’s On the Fabric of the Human Body (1543) is a phenomenal work, seven volumes of beautiful engravings that revealed the elegance and beauty of the human body, just under the skin, for the first time.

And of course the Times Atlas of the World. In times of pandemic lockdown it’s a consolation to be able to go atlas-travelling until the real thing once again becomes possible.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

Which aspect of the self? Every book I’ve ever read has had that power. Like everyone else, different books have all inspired aspects of the many roles I inhabit, whether it’s as a doctor, a writer, a traveller, a scientist, or even as a father.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

John Berger and Jean Mohr’s A Fortunate Man, about a country GP in 1960s Gloucestershire, has offered deepening friendships with others who also love that book, and those with whom I’ve shared it. But I’m also grateful to it for igniting my own friendship with Berger. I wrote to him about another of his books, Cataract, we struck up a correspondence, and he invited me to stay with him in Paris. Our conversations led to me writing the introduction to the new edition of the book (Canongate, 2015), through which I hope many other readers will come to know it.

The book as . . . entertainment. What is your favourite rattling good read?

Elena Ferrante! The world she created is utterly immersive and compelling. Also Hilary Mantel’s Cromwell books. Ursula le Guin’s Earthsea books. Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials. I could go on…

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

I love Anne Michaels’ Fugitive Pieces, a novel set between Eastern Europe, the Aegean islands and Canada. Canada I don’t know at all, and the Aegean and Eastern Europe I have visited only briefly. But the ‘destination’ is less important as a set of geographical coordinates than feeling at home in an author’s writing. I have read WG Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn ‘about’ Norfolk numerous times, but know that in the future I’ll go on visiting it through his eyes, not my own. Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost is good on this – the writing as an exploration of an idea rather than the exploration of a place.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

So many… Like all your bibliophile readers my bedside table is always stacked high. It’s a pleasure to know that beautiful, inspirational books that I’ll come to love are being written right now and I don’t even know yet how much I’ll need them in my life!

Visit Gavin Francis’s website www.gavinfrancis.com

Island Dreams: Mapping an Obsession by Gavin Francis is published by Canongate, priced £20.00.

Cameron McNeish is one of Scotland’s most popular broadcasters on hillwalking. He follows up his popular memoir, There’s Always the Hills with his new book, Come by the Hills, which celebrates Scotland’s hills and his memories of walking them. In this extract, he walks to Glen Lyon in the Highlands and appreciates its majesty and mystery.

Extract taken from Come by the Hills

By Cameron McNeish

Published Sandstone Press

The Longest, the Loveliest and the Loneliest

Sir Walter Scott first described Glen Lyon in the above terms, and my mentor Tom Weir was fond of using the same alliteration to describe this thirty-four-mile-long glen of Highland Perthshire. He often told me Glen Lyon was his favourite, and for a man who knew Scotland like few others that was a high recommendation.

It is indeed a magnificent place, from its heavily wooded lower glen near Fortingall, where the River Lyon crashes and tumbles through its deep, shadowed gorge, all the way to the bare upper slopes of the glen, a place of desolation and remote mountain grandeur despite the hydro works that have dammed the loch, created a stony tideline around the shores and laced the upper glen with power lines. Notwithstanding the hand of man, Glen Lyon is famed for something else. It is also Scotland’s most mysterious glen, a place of myth and legend and, according to some, home to the creator goddess of the ancient Celtic world.

Years ago, I met an old friend of mine here. Lawrence Main lives in Mid Wales and has a penchant for New Age thinking. Lawrence describes himself as a Druid and has a long-standing fascination with the earth-mysteries and legends of our wild places. He had come north to Glen Lyon to visit Fortingall, a place he believed may have been the birthplace of Pontius Pilate, the Roman judge of Christ. Two thousand years ago, the legend suggests that Emperor Caesar Augustus sent an emissary to Scotland, to Dun Geal, near modern Fortingall. The emissary’s wife gave birth to a baby, and they called him Pilate. He went on to become the fifth procurator of Judea and ordered the crucifixion of Christ.

Lawrence was also searching for the Praying Hands of Mary, a large split rock that stands in Gleinn Dà-Eigg, an offshoot of Glen Lyon close to Bridge of Balgie. He also believed that Glen Lyon was the home of the Celtic creator goddess, and was itself a sacred place. Although megalithic remains are found just outside the glen, in Fortingall and near Loch Tay, Glen Lyon is curiously devoid of megalithic monuments. As the home of the creator goddess the glen was sacred by nature and such special sites were normally left untouched by the ancient Celts.

Lawrence’s revelations aroused my own long-standing interest in such mysterious matters. Just as North American outdoors folk have learned much from the native North American tribes, so I believe we can learn much from our Celtic ancestors, particularly about living in harmony with the land. Lawrence’s various speculations reminded me of a story I had been told some forty years ago by an old pal of mine, the late Harry McShane, a former warden of Crianlarich Youth Hostel and an erstwhile hillwalking buddy.

Harry told me a story about small stone figures that were apparently taken to a lonely spot near the head of Glen Lyon every spring, and removed again every autumn. He couldn’t verify the story and had no idea who moved the stones, but the tale has lodged in the scree slopes of my memory and my conversations with Lawrence Main encouraged me to carry out further research. What I discovered surprised and astonished me. This is the story of a pagan shrine dedicated to the Cailleach, in the tradition of the Celtic mother goddess, who once blessed the cattle and their pastures and ensured good weather.

The Cailleach, often translated as the ‘old woman’ or in this case the ‘divine goddess’, is a potent force in Celtic mythology, commonly associated with wild nature and landscape. The Celtic creator goddess is encountered throughout the length and breadth of Scotland, an entity taking many forms and represented in a variety of different shapes. Believers would see her essential nature in the harmony and balance of the natural order, the ebb and flow of growth and decay, of life and death itself.

Nearby, in Rannoch, legend names her as the Cailleach Bheur, the blue hag. According to A. D. Cunningham’s excellent book Tales of Rannoch this old witch was once a familiar sight on Schiehallion: ‘Her face was blue with cold, her hair white with frost and the plaid that wrapped her bony shoulders was grey as the winter fields.’

Other ancient forces have been at work in Glen Lyon. Years ago, just before I climbed the Corbett of Cam Chreag, high above the glen, I visited the little church at Innerwick. There’s a car park with interpretative signs beside the start of the right-of-way that runs over the hills to Rannoch and the little church is well worth a visit, just to see the ancient bell of St Adamnan.

St Adamnan, also called Adomnan or Eonan, was Irish-born and is famed for his biography of St Columba, whom he studied and worked under at Iona. Adamnan lived mostly in the seventh century and died around AD 704. His bell has been dated to AD 800 and apparently lay in the churchyard of St Brandon’s Chapel in Glen Lyon for centuries before being rescued. St Adamnan travelled here from Iona, setting up Christian cells on ancient pagan sites of worship. Another of his churches lies on the shores of Loch Insh, by Kincraig in Badenoch and, curiously, that church also has a bell that apparently belonged to the well-travelled saint. At Loch Insh, according to the legend, St Adamnan used to ring the bell to summon the Swan Children of Lir, a brother and sister who were half child, half swan, to worship. Today, Loch Insh, and its adjoining meadows, is Scotland’s principal wintering place for whooper swans. Coincidence?

I recalled these old stories as I climbed towards Cam Chreag, a 2,828-foot/862-metre Corbett that neighbours the Munro of Meall Buidhe above Loch an Daimh. I wanted some photographs of the loch and the wild land beyond it and remembered Cam Chreag as a pretty good viewpoint. I was also aware that the recommended route given in the guidebooks was less than satisfactory and a better route was possible by following the hill’s south-east ridge, returning to the start via its lowly neighbour of Meall nam Maigheach, a pleasant horseshoe-shaped route of about nine miles round the glen of the Allt a’ Choire Uidhre.

This glen has a bulldozed track running up its length to a corrugated iron hut just below Cam Chreag’s eastern face – the guidebook route – but the first bonus of my horseshoe route became apparent as I topped out on Ben Meggernie, at the end of Cam Chreag’s east ridge. This little bump offers a fabulous view right down the length of Glen Lyon and is well worth climbing, if only to understand why Tom Weir, and others, have described this as Scotland’s loveliest glen. On one side the peaks of the Ben Lawers range rise high into the sky, the pointed culmination of long, steep ridges. On the other, the blunter Carn Mairg hills rise on equally steep-sided flanks. The glen itself is wooded with the River Lyon flowing through green meadows. Rob Roy’s mother was born here, and before that the ancient Kings of Scotland came here to hunt deer.

Lovely as Glen Lyon is, I was more impressed with the views from Cam Chreag itself. To the west, the big Munros stood clear: Stuchd an Lochain and Meall Buidhe, one on either side of Loch an Daimh, and the wild country beyond to the hills of Mamlorn and Orchy. To the north-west, across the Rannoch Moor, Ben Nevis was clearly visible, rising above the hills of the Mamore Deer Forest and the enormous bowl of peat hag and heather, lochs and lochans that make up the vastness of the Rannoch Moor. Only the West Highland railway line offers any sign of man’s hand until you reach the A82 Bridge of Orchy road and the A86, away beyond the narrow slit of Loch Treig.

Come by the Hills by Cameron McNeish is published Sandstone Press, priced £19.99.

David Robinson enjoys the comic capering in William Boyd’s latest novel, Trio, set against the backdrop of an ego-strewn film set and the changing social mores of the 1960s.

Trio

By William Boyd

Published by Viking

1968. Across the Channel, rioting students are taking on the government. On the other side of the planet, the Americans are mired in the Vietnam War. In Brighton, meanwhile, the Sixties are swinging by in comparative peace, and filming has just started on Emily Bracegirdle’s Extremely Useful Ladder to the Moon. There’ll be a nude scene tomorrow with its two stars, the beautiful American Anny Viklund and home-grown pop star Troy Blaze.

We’ll be on or near the filmset for almost all of Trio, William Boyd’s 16th novel, a deliciously black comedy that takes us inside the heads of three characters – Elfrida, an alcoholic novelist married to the film’s director; Anny, the film’s star, who seems to have fallen foul of the CIA; and Talbot, the film’s producer, whose job seems to consist entirely of preventing the whole enterprise from unravelling.

Although Boyd has written about film-making before in The New Confessions (1986), that novel ranged panoramically across continents and most of the 20th century. Here the focus is both tighter (in its time scale) and looser (the three-way story split). We’re not looking – as we were in the earlier novel – at the rise and fall of art forms (silent movies, B-westerns) but at the sheer grind, greed and grubby compromises involved in the shooting of a single film.

Boyd knows more about film-making than most novelists, having directed one himself (The Trench, 1999) and written more than 60 scripts for film and TV, including the BAFTA-winning adaptation of his 2002 masterpiece, Any Human Heart. Of those 60, about 20 have actually been made – a 1:3 success rate which is unusually high in the screen trade. So he knows all about why movies implode or fail at the box office, and the novel reflects his knowledge of the pitfalls, extravagances and workarounds that are all part of most film shoots.

The star of this behind-the-scenes story is producer Talbot Kydd. The pressures on him are many and varied: the director who goes behind his back to make sure his girlfriend is hired as a writer; the pop star’s gangsterish managers; or a co-producer trying to finesse valuable film rights away from him. He has grown used to coping with far more, in a job that seems to consist of cosseting his stars, dealing with drugs, divorces, punch-ups, drunkenness, scene-stealing, one-upmanship and ‘generally the sort of behaviour that a three-year-old would be ashamed of’.

Unbeknown to Talbot, Elfrida, the director’s wife, is falling apart. It’s been ten years since she wrote her third novel, her writer’s block growing ever wider as she sinks into alcoholism. Maybe the seeds of it were there right at the start of her career, when she was heralded as ‘the new Virginia Woolf’ – an epithet she is unable to shake off, even though she can’t stand Woolf’s novels. Finally, she has an epiphany: she realises the will only be able to write if she kills off Woolf in her own fiction, so she starts writing about the summer’s day in 1941 in which Woolf waded into a river weighted down by stones. That happened only about 15 miles from Beachy Head, where Elfrida’s husband sets the denouement of his film, in which his two stars prepare to do what we now know as ‘a Thelma and Louise’ over the East Sussex cliff. Suicide – both fictional and real – is in the air.

Boyd has always acknowledged the influence of Evelyn Waugh – the ‘glittering, malevolent brilliance’ of early comedies more than his later works – and there are indeed strong echoes of it in the Elfrida chapters. She drinks remorselessly, lying about it all the time, yet here at last is a way out. Why, she wonders, has it taken her so long for this recension? She looks it up. No, wrong word. Recessional? No. ‘”Transfiguration” was the word she needed. It had been a transfiguration, a transformation, something beautiful, sublime had happened – a metamorphosis.’

Boyd tells Elfrida’s story in the third person, but it is written so closely that it might just as well be first. On page one of Trio, the waking Elfrida notices the sun ‘printing a skewed rectangle of lemony gold light onto the olive green-flecked wallpaper close by her pillow’. And when Woolf wakes up on her last day on page one of Elfrida’s novel, exactly the same rectangle of sunlight and design of wallpaper reappear. This is Boyd doing what he does best: playfully crossing and recrossing the line between fact and fiction so often that it starts to blur. He shows us the opening paragraphs in Elfrida’s novel, constantly being rewritten as the vodka takes hold. We will see her stumbling about on her research, wondering, for example, whether Virginia ever used a Hoover. This is great comic writing, not least because it sometimes bring us up short, like when she spots an old man in the garden of Woolf’s house and asks if she can come in and explains why she wants to. The old man, she realises later, in a scene that is pure Waugh – hard-edged, unsentimental, shocking – was Leonard Woolf.

Something else is going on in that scene. Although this is 1968, we are made to realise how close the world of 1941 remains. Leonard Woolf is reading the newspaper in his garden now, but his wife’s tragic death is presumably still within him. Similarly, the skies above East Sussex that feature in the rather ridiculous film Talbot is shepherding to a conclusion were, only a generation before, full of men trying to kill each other. Talbot’s own brother was one of them: his Spitfire crashed into the sea just three miles off the Sussex coast.

In the war, Talbot was a major in the Army. He was gay, but never acted on his impulses and instead married a nice Home Counties gal. But now the times are a-changing, especially for those who are, as they said back then, ‘light in the loafers’. Boyd has always had a wonderful ability to place his characters very precisely in the past and that is very much the case here. The 1967 Sexual Offences Act legalising homosexual acts between consenting adults has made a difference and a new gay club has just opened down the road in Brighton. The thought of going there has already crossed Talbot’s mind.

Of the titular trio, I shall pass lightest of all over Anny. Maybe she’s the reason the film is being made – a genuine American star of head-turning beauty – but she’s not the reason this novel will be read. True, she is fundamental to the plot’s more action-packed scenes and has her own secrets, but compared with Elfrida and Talbot she is just a pretty face. Yet that is unfair too: without Anny, there’s certainly no film and there mightn’t even be a novel.

It’s been a while since Boyd gave us such an obviously comic novel, and the scenes of Elfrida’s search for the real Virginia Woolf are a hoot. No doubt some readers will be disappointed that it’s not another Boydian epic in the mould of Any Human Heart, but they’ll be missing the point: instead of showing lives changing with the great sweep of the century, he is picking a seemingly inconsequential moment in time and describing the making of a definitely inconsequential film. But because Boyd is such a capacious novelist, there’s a lot more than that to it. Part thriller (Anny), part clever literary comedy (Elfrida), part subtle portrait of Sixties change (Talbot), part knowing homage to the zaniness of movie-making, Trio burns with brio.

Trio by William Boyd is published by Viking, priced £18.99.

Despite the death of Arthur Conan Doyle, readers still cannot get enough of his most famous creation, Sherlock Holmes. Robert J. Harris is adding to the new Holmes canon with his brilliant tribute to the detective in his novel A Study in Crimson. In this extract, Sherlock leads Watson to a shocking discovery in their latest case.

Extract taken from A Study in Crimson

By Robert J. Harris

Published by Polygon

I was woken at the earliest hour of morning by an energetic rapping at the connecting door. As I struggled upright on my pillows, the door was flung open and Sherlock Holmes strode imperiously into the room. He was fully dressed, and at close quarters smelled of soap and hair oil.

‘Come along, Watson,’ he exhorted me briskly, ‘this is no time to be a slugabed. My nostrils are twitching with the scent of a breakfast being cooked.’

Even through the blackout curtain, I could tell it was still dark outside. ‘Holmes,’ I grumbled, ‘it’s surely too early for breakfast.’

‘Too early for us, but not for certain others. Come along, man. Get dressed quickly and meet me outside.’ With that he was gone. Clambering out of bed, I pulled on my clothes, ran a comb through my hair, and stumbled downstairs. Holmes was pacing up and down outside the front door in a fever of impatience.

When he spotted me, he pressed a finger to his lips. ‘Quiet now and keep to the shadows,’ he instructed, and beckoned me to follow.

We made our way round the north wing of the castle to the rear where we crouched behind a rain barrel. From this vantage point I could see Holmes’s gaze was fixed firmly on an open door in the basement level. From the scents wafting through the air I had no doubt that this was the back entrance to the kitchen. Why we should be spying on Mrs Sienkowski’s efforts was beyond me, while the smell of cooked breakfast stirred a sharp hunger in the depths of my stomach.

Holmes abruptly yanked me down deeper into hiding as a uniformed figure emerged from the doorway and made its way steadily up the small set of steps to the ground level. I recognised at once the burly outline of Sergeant Ross. He was carrying a tray which held an assortment of covered dishes. As we watched, he set off into the surrounding woods.

Holmes turned to me with a gleam in his eyes. ‘Come along, Watson, and go cannily. Sergeant Ross is our trail of bread crumbs.’

Crouching low and darting from one patch of shrubbery to the next, we followed the sergeant into the trees. There was no difficulty about keeping him in sight even at a safe distance, as he was making no effort at concealment. He clearly did not expect anyone else to be abroad at this hour and strolled casually along a narrow, winding path.

‘Holmes, where on earth can he be going?’ I murmured.

‘Can you not guess?’ Holmes sounded genuinely surprised.

In a flash it occurred to me that Ross must surely be taking this breakfast tray to the vanished Dr MacReady.

I said breathlessly, ‘Are you suggesting that the sergeant is actually an enemy agent? That he spirited Dr MacReady away and is holding her captive somewhere in these very grounds?’

Holmes clucked his tongue reprovingly. ‘I’m suggesting nothing of the sort. Surely I explained it all last night.’

‘You did everything but explain,’ I retorted with some warmth. ‘Perhaps you might begin with the loose button on the discarded blouse to which you attach such importance.’

‘It was pulled loose because the blouse was removed in haste,’ said Holmes. ‘The fact that the shoes were kicked off willy-nilly and the skirt was only partially unzipped before being pulled off tells the same story.’

‘Are you saying that Dr MacReady was in a hurry to take a bath?’

‘If she had intended to take a bath, she surely would have put the plug in before turning on the taps. No, no, the clothes in the doorway and the running water were intentional distractions. Then there were the spaces on the bathroom shelf from which a few essential toiletries had obviously been removed. On the other side of the room was the telling evidence of the wardrobe.’

The path forked ahead of us and Ross turned off to the left. As we followed, Holmes continued to discourse.

‘You saw the disordered shoes in the otherwise tidy wardrobe. They had been thrust aside to make room for a bundle. Then, of course, the clothes hanging there, and the shoes themselves, clearly indicated that Dr MacReady is quite a tall woman.’

I felt myself bewildered but pressed on. ‘And the mark on the wainscot?’

‘Made by the thick rubber sole of a boot. Someone was pressed tightly behind the door out of sight. Of course, none of this was possible without the aid of Sergeant Ross and some of his men.’

‘But why on earth would Ross connive at the doctor’s disappearance?’

‘From his choice of reading matter,’ said Holmes with a grimace of distaste, ‘which he was so annoyingly eager to share with us, we know he has a taste for adventure. It may be why he joined the army in the first place, only to find himself incarcerated here with a party of dry, bookish intellectuals. Few things incline a man towards mischief more surely than boredom.’

Still following the sergeant, we came within sight of the loch I had observed upon our arrival. Nestled among a stand of willows on the shore was a wooden building in a poor state of repair, that must once have served as a boat house. Ross ducked under a low door and disappeared from view.

‘Last night you told me that the most significant thing about Dr MacReady is that she is a Scotswoman,’ I reminded Holmes. ‘What did you mean by that?’

‘Come, Watson,’ said Holmes, leading the way to the boat house. ‘You surely noticed that her colleagues are all English and are held in various degrees of contempt by the Scotsmen who guard them. She alone has a spark of life, she alone is happy to mix socially with the soldiers and, like them, she has taken a considerable dislike to the officious Professor Smithers, particularly so as he disdains her purely on the basis of her sex.’

The full realisation of the plot now dawned upon me. ‘So when you told Professor Smithers that he was the victim in this affair, you were not simply being ironic.’

‘Indeed not,’ said Holmes, bowing his head to step indoors.

A Study in Crimson by Robert J. Harris is published by Polygon, priced £12.99.

Caroline Logan began her fantasy YA series, Four Treasures, with last year’s The Stone of Destiny. On publication of the next instalment of the series, The Cauldron of Life, BooksfromScotland got in touch to ask Caroline to tell us more about the series and her writing.

The Cauldron of Life

By Caroline Logan

Published by Cranachan

Congratulations, Caroline – you’ve just published the 2nd book in the Four Treasures series. For those people who still haven’t found themselves in the world of Eilanmor, can you tell readers what to expect from the series and from the The Cauldron of Life?

The Four Treasures series is based on Scottish mythology. Book one, The Stone of Destiny, followed Ailsa MacAra, a social outcast, who got roped into finding a magical stone by two insistent selkies. If you’ve read the book, you’ll know that there was a lot more to the story. I always have people saying: ‘but there’s 100 pages left, what’s going to happen?’ Basically Ailsa’s world was turned upside down and The Cauldron of Life is about her journey to find out who she really is. I’ve heard people say The Cauldron of Life is darker and has higher stakes than The Stone of Destiny. I guess that’s the benefit of a sequel: I’ve already introduced the characters, so now we get to go deeper into the world.

Your books are inspired by Scottish myth and legend. How did your interest there grow? Were you imagining faeries and selkies when you were young too?

Actually, I didn’t really know about Scottish mythology when I was young. I think we hear about so many English and Welsh or even Greek myths but not so much of ours. In fantasy books and movies, we tend to find dragons and mermaids, but never selkies and kelpies. So when I decided I wanted to try writing my own book, I tried to find out more about Scottish legends. I feel very grateful that I get to write about those stories as a Scottish person – they feel like my heritage.

How do you tackle writing about the past—even a fantastical past—for a modern audience?

I have a confession to make: originally I wanted to write a historical fantasy novel, but I found the research too difficult. I worried that I wouldn’t get things right since I don’t have a history degree, so I decided to just make up my own world based on Scotland. I’m really glad I did because it means I can have kilts and curry and beautiful dresses – things that wouldn’t have existed in a medieval setting. A lot of YA Fantasy is written like that, drawing on the past for inspiration but not holding itself to accuracy. It’s more entertaining, and at the end of the day that’s what a story should be.

The Four Treasure books form a series. Do you know what’s going to happen in the future books? Have you always known how the series will end? How do you tackle pacing in a series as well as a single novel?

When I first started writing The Stone of Destiny, I imagined all the things that will happen in the series in one book, but I quickly realised the story was too big for that. It grew to a duology, then a trilogy and then a four book series. Four is my lucky number anyway. From the beginning, I’ve had all four books plotted out, but I do add some things as I go. I know exactly what will happen in each of the books. That means I can drop in some little Easter eggs as I go. For example, someone walks past in Book one that you’ll eventually meet in Book three. In terms of pacing, I just try to have a number of peaks and troughs and I like to keep the pace up. No one wants to read about a return journey – the characters have already been there. So I just skip time a bit and add in some more action!

What is it about the fantasy genre that you think excites young readers?

I think everyone hopes that the world is a magical place, but sometimes we need to escape into books. Fantasy provides that fantastical escape and is so different to daily life. The stories are epic and inspiring. Personally, I love being spooked, and fantasy also has that ability. While things can be beautiful, they’re often also deadly.

What were your favourite books as a teen reader?

I really loved The Wind on Fire series by William Nicholson and The Chronicles of Narnia by C. S. Lewis, plus Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman. Towards my later teen years I became obsessed with Dan Brown’s books – I love a bit of symbology and art history. I tried to write about Angels and Demons in a Higher English essay but my teacher was having none of it. She said his writing wasn’t good. Maybe I should have listened to her as I got a C in the final exam.

As well as writing, you teach high school biology. What do your pupils think of your books? Does your teaching inspire your writing?

A surefire way to get me flustered is for one of my pupils or co-workers to tell me they’ve read my book. I definitely separate those two parts of myself so when the worlds collide it feels very strange. Thankfully, most pupils have been really complimentary. I hope it’s inspiring for some of them to know that you can do one thing for your day job and also have a creative outlet. They have asked me before if I’m going to give up teaching but, aside from it not paying well, I don’t know if I could give up seeing them everyday. I’m very proud of all of them.

Does your expertise in science find itself in your writing?

Yes, absolutely. I like to know that what I’m writing about has a little bit of science to back it up. You see it a lot more in The Cauldron of Life; there’s a character who is a healer and all of the things he says are based on fact. Also, I studied Geography during my first year of university and I definitely drew from that when I was drawing my map.

You live in the Cairngorms National Park area. How does your surroundings influence your novels?

I started writing The Stone of Destiny when I lived in Campbeltown and you can see how that environment inspired the first part of the book. There are sandy beaches, caves and the churning sea. At one point when I lived there I did part of The West Highland Way and that made it into the book too. Now that I live in the Cairngorms, I think you can really see a shift in the landscape in The Cauldron of Life. The characters journey through the woods and, if I was ever lacking inspiration, I could just take my dogs for a walk in the forest.

What books have got you through this year’s lockdown experience?