Peter Ross has been writing, with great empathy and care, of lives great and small throughout his journalistic career. David Robinson finds he brings the same skill and sensibilities to his new book on death and burial, A Tomb With a View.

A Tomb with a View: The Stories and Glories of Graveyards

By Peter Ross

Published by Headline

Whether with a ton of earth above us or an hour and a half at 900C in the incinerator, all our stories come to an end sometime. Opt for the former, though, and there is at least a sliver of hope of an afterlife. One day over the rainbow, Peter Ross might wander into your graveyard, notebook in hand.

It helps if you have had an interesting life or death. The first barmaid in England to have been eaten by a tiger (Hannah Twynoy, 23 October 1703, Malmesbury) makes it into his pages. So does the first woman to be bayoneted while fighting as a soldier in the British Army and then live until 108 (Phoebe Hessel, 12 December, 1821). But let’s face it, once you’ve stood in front of their lichened graves and read the inscriptions, unless you’re writing a biography, what else is there to say? Fascinating these lives may have been – and Ross is right, Hessel’s is a BBC drama series waiting to happen – but they have all reached a full stop. What can a writer add?

Quite a lot, as it happens, because there is always a lot more to say about death, especially in an age like ours which tries to block it out with an ocean of trivia. In 1859, when Jules Verne visited Edinburgh, he noted that, among the city’s haute bourgeoisie, one of the most popular destinations for a Sunday afternoon stroll was around the well-maintained paths and gardens of Warriston Cemetery. The Royal Botanic Garden had opened nearby just 40 years earlier, but to the promenading mid-Victorians, taking a gentle stroll around a garden of death was a comparable attraction. I know Warriston Cemetery reasonably well, and even though it is no longer the vandalised junkie playground it was in the Eighties, it is hidden away from the rest of the city, half overgrown, well off the tourist trail, and with nothing neat, tidy or haut bourgeois about it at all.

In our culture, Death has made exactly the same transition, from central to fringe, visible to obscured. These days, it’s the people who hang around graveyards, who openly talk about death, who are intrigued by our attitudes to it, who are the real oddities. Ross is one of them. Even as a child, growing up in Stirling, he haunted the nearby cemetery; in lockdown, he has found himself walking most days in the cemetery behind his house ‘as a vaccination against gloom’. And why not? It’s always consoling to find someone worse off than yourself, after all.

Taphophiles – people who are interested in cemeteries, funerals and gravestones – are an interesting bunch. What makes them go against the cultural current? What made Bob Reinhardt – who lives in the US – set up Friends of Warriston Cemetery and become so obsessed with the place that he has taken around 60,000 photos of it and other Edinburgh burial grounds? Why did John Constable (aka ‘urban magician’ John Crow) set up the Crossbones annual vigil for London’s medieval outcast dead outside the place where they were buried in unmarked graves? What made Nick Reynolds, Alabama 3’s harmonica player, start a new career as a death mask artist, taking casts from the freshly dead faces of the likes of Malcolm Maclaren and his own father, the Great Train Robber Bruce Reynolds?

In some ways, these people are the Thanatotic equivalents of the glorious eccentrics Ross has interviewed as a journalist. But he didn’t win all his many awards just for writing about colourful characters. He can also handle harder stories that blend history and culture too, sometimes ones you might never have thought of. What, for example, happens to urban graveyards when they are full up and no-one has any money to look after them? Should cemeteries with famous dead market themselves as tourist attractions? How do Muslims manage to bury their dead within 24 hours? Will we ever finish burying the dead of the First World War? (Answer: probably not). And are cillini – unmarked graves near churches for the unbaptised – doomed to be forgotten?

In his last book, The Passion of Harry Bingo, Ross wrote about how close journalistic observation is a form of compassion, and how while working on a story, all of his senses are engaged as he tries to understand, without any preconceived ideas, what is going on around him. Here, that seems particularly true of the chapters set in Dublin and – particularly – Belfast, where the ‘dark romance’ of the paramilitary dead colours the city ‘like some hidden pigment just outside the visible spectrum’.

Good feature writing demands having an eye for detail, an ability to ask tough questions and a certain humility too: the journalist is just a fly on the wall, not omniscient. Walking with the Easter Sunday parade to the Republican plot at Belfast’s Milltown Cemetery, Ross spots a little girl outside the Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children, banging gleefully on her dialysis machine as the marchers pass by, honouring the dead of the 1916 Easter Rising with flutes, drums and replica uniforms and rifles. He is accompanying former Sinn Fein spokesman Danny Morrison, who points out each place someone was killed by the British Army as they pass by. Could, he asks, the British soldiers who also died on these streets ever be commemorated too? Morrison’s answer takes him by surprise. The families of British soldiers know what to expect when their sons sign up, Morrison replies, so if they die on active service, that’s an end to it. ‘Well, that’s not the end of it for us,’ he adds. ‘Our dead are precious.’ Yet it’s surely blinkered to think that the other side’s dead aren’t precious too.

There’s a lot of history in these pages, as there has to be: the story of London’s ‘Magnificent Seven cemeteries’, from the ‘Victorian Valhalla’ of Kensal Green to Marx’s Highgate haven, demands it. But this is more than a book about the historical changes in the British and Irish way of death. Other writers could do that, and they’d all probably also finish by describing natural burial – sometimes called green or woodland burial. But I bet they wouldn’t end up, as Ross does, at one such natural cemetery overlooking the River Dart in Devon on a blustery All Souls’ Day. If they did, they probably wouldn’t find themselves talking to a woman whose husband had committed suicide while being mentally ill. And even if they did all that, I don’t imagine they would get to hear about how she broke off in the middle of putting the earth around his body with her bare hands to have a cigarette. How she took off his shroud just before he was put in the ground and how it now hangs above her fireplace. How they fell in love, and how it was a love story right to the end, even though in hindsight she realises he should have been sectioned.

Research gets you so far. But empathy gets you the whole story, the kind of story Ross heard from that woman in Devon and which is echoed throughout this engaging book, filled as it is with life, and loss, and love.

A Tomb With A View by Peter Ross is published by Headline, priced £20.

Andrew O’ Hagan is one of Scotland’s most talented and interesting writers and his latest novel, Mayflies, is garnering praise across the board. BooksfromScotland caught up with him to talk about his favourite books.

Mayflies

By Andrew O’ Hagan

Published by Faber

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

In our house, you had more chance of spotting a mountain gazelle than a book. My parents didn’t read, and life, for them, seemed to carry enough distractions and entertainment to keep them going. But for me reading was a kind of religion. It raised you to the higher ground. In school, I pored over my first reading books as if they were Wisdom Itself. I’m talking about books called things like Dick, Dora, Nip, and Fluff. It was a steady, exhilarating climb from there. I remember, when still small, reading Wuthering Heights, and feeling that I saw human beings on the page for first time — romantic, unreasonable, beautiful, despairing. Just like life, only better. I was hooked.

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest book Mayflies. What did you want to explore in writing it?

I wanted to write a funny, true, and heartbreaking book that showed a friendship in its entirety. From beginning to end, the book relates to my own life, and I wanted that autobiographical urgency to perfume the story. We meet two Scottish boys in Mayflies, two funny kids growing up in Ayrshire, and they are full of attitude, music, politics, plans, and hurts — they rush into the world in the hope of making it better. And what do they find? How does their childhood closeness affect their adulthood? These are questions for everybody, and when, in the book, one of the boys telephones the other one, 30 years later, with terrible news, loyalty and love are tested. As I say, it’s my most personal book, and I felt in writing it that I was telling a story everybody really interested in human experience could relate to.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

My favourite book changes every day. Today it is The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Robert Louis Stevenson had such a wonderful imagination — so bizarre, yet so human, so universal, yet so particular — and you just can’t improve on his sentences. He designs each book perfectly to suit his material. No two books are the same, or even similar: they are discrete works of art with their own architecture and their own colours. Dr Jekyll makes me see that I am a disunited person, as all people are. We are a disunited kingdom, as all kingdoms are. The lesson is that life is nicer if we use our intelligence to confront our opposites, though, unfortunately, the lesson comes too late for the good Doctor. Tolerance of difference should be our hallmark. Stevenson’s story (so handsomely Scottish in its bones) manages to suggest a whole philosophy of life in its allegory. With great economy, it paints existence.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning by Alan Sillitoe. It’s not a masterpiece of any sort, but it does its work perfectly. It’s a story of a working class lad in Nottingham who resists the forces that would keep him down. One of my friends, Keith Martin, who inspired Mayflies, was driven forward by that book. We both were. And it became a kind of bonding text for us and many of our gang at that time — a vivid, bright book of life.

The book as . . . object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

Old Glasgow by Thomas Annan. This is a book of carbon-print photographs published in 1878. It is the real beginning of urban documentary photography, based on life on the street, and the book, in green Morocco leather, is so rare and so expensive that I know is shall never own it. But they have it in the Mitchell Library. It is a wonderful object and alters your sense of what beautiful means, when it comes to a book.

The book as . . . entertainment. What is your favourite rattling good read?

It would have to be a biography. They are my beach reads — I am just riveted by all the stuff that can happen in real life. At the moment I’m reading an early proof copy of Tom Stoppard by Hermione Lee. I’m also looking out for two new Dickens books, by A.N. Wilson and John Mullan. In fiction, you can’t beat Zola for suspense and gripping-ness.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

It would have to be Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s The Worst Journey in the World. The author was part of Scott’s team when he attempted to reach the South Pole, and it’s a masterpiece of witnessing and reporting. You are there, with them. A new book along those lines that I admired, a vivid account of one man’s bizarre journey to reach Everest, is Ed Caesar’s The Moth and the Mountain. When people say they can’t put a book down, they must be holding a book like Ceasar’s.

The book as. . .education. What is your favourite book that made you look at the world differently?

Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man. It never gets old. Once you’ve read it, you want to fix the world, or fix yourself, which is the same thing.

The book as. . .technology. What has been your favourite reading experience off the page?

I am having a torrid affair with my Kindle. I go home to my books every night, and sit down to dinner, and we go to bed, but in the afternoons I am often to be found in flea-bitten places, somewhere at the edge of the city, looking lovingly at my Kindle.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

Edinburgh University Press are in the process of publishing a series of beautiful, new, fully edited and annotated editions of John Galt’s work. One of the first two in this glittering series came out in June and is Annals of the Parish. Edited by Robert P. Irvine, the book is masterstroke of scholarly diligence and imaginative publishing. Every respectable home in Scotland should have a copy. Born in Ayrshire, John Galt is the first great novelist off the industrial revolution, and I can’t wait to reacquaint myself with Annals, his greatest work, a hilarious and far-seeing masterpiece of Scottish literature, which will be 200 years old in 2021.

Mayflies by Andrew O’ Hagan is published by Faber, priced £14.99

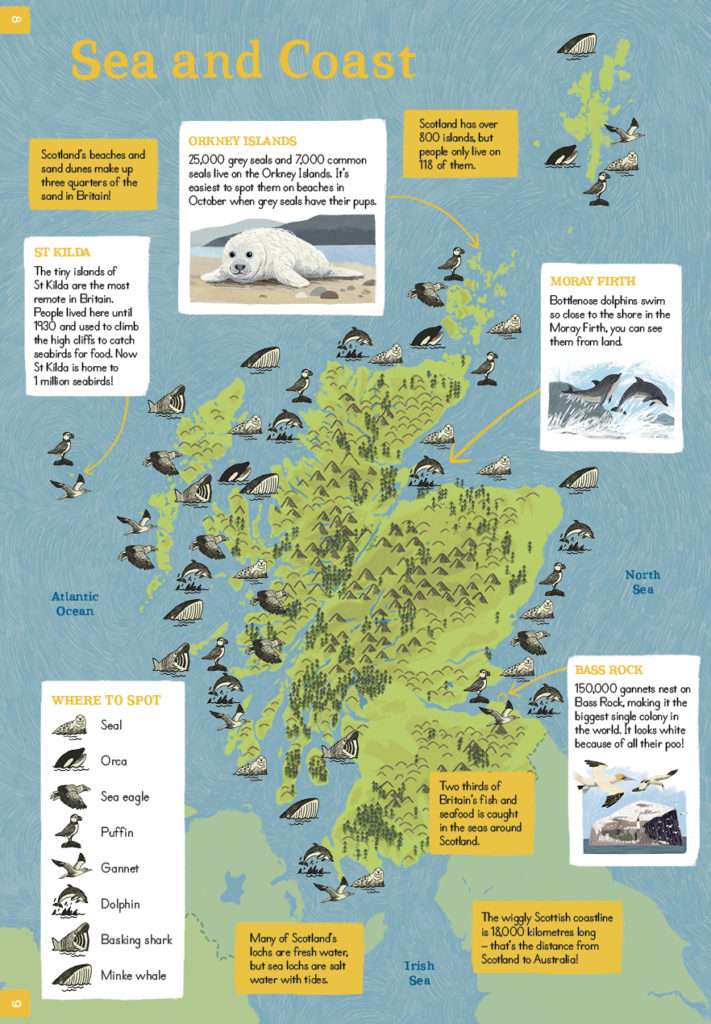

Floris Books publish many brilliant, colourful books for children celebrating Scottish history, culture and nature – they are always a bit of a treat! The latest release, The Amazing Animal Atlas of Scotland, takes you around the country and is packed with information on our wildlife.

The Amazing Animal Atlas of Scotland

Illustrated by Anders Frang

Published by Floris Books

Find out more about The Amazing Animal Atlas of Scotland over on the Floris Books YouTube channel:

The Amazing Animal Atlas of Scotland, illustrated by Anders Frang is published by Floris Books, priced £12.99

Bloomsbury’s Object Lessons series are short, beautifully designed books about the hidden lives of ordinary things. Laura Waddell has written a book in the series on exits, and what they mean on subjects such as architecture, transport, ancestry, garbage, death, Sesame Street and Brexit. In this extract she tackles language, and Scots in exile.

Extract taken from Exit

By Laura Waddell

Published by Bloomsbury

What are exits, if not turning away from the colour and clutter of one situation into another whose possibility and potential is yet to come? A blank canvas; the space to create. Although sometimes that’s frightening, too.

Helen Adam was a Glasgow-born poet who reported that, not until she left Scotland and moved to America in the late 1930s, was she able to find her poetic voice. She found her groove in performing traditional Scots ballads, an oral rather than written tradition and so by its nature tenuously recorded in history, mixing with the San Francisco Beats scene as it flourished in the 1950s. Fellow poet Edwin Morgan described the effect of her move as a jolt bringing to the surface what was already there:

‘Although she had grown up in a literary household and been in college when Hugh MacDiarmid was asserting the political necessity of claiming Scottish literature and dialect as distinctly separate from English, all the poems Adam had written while she lived in the UK followed English rules and dictionaries It was not until she got to America that she began investigating her own native Scots language and incorporating Lallan dialect into her ballads. Similarly, Ginsberg encouraged his students at Naropa Institute, on a day when they were studying Helen Adam and the ballad tradition, to remain true to their own regional American dialects.’

I can imagine Adam testing her sense of self. Leaning into the differences between her voice and others, as well as bringing something new and different to the linguistic scene. Her ballads were hearty songs full of mythmaking, and her lyrical voice was pulled along by their bounding beat. They were lustful and intemperate, eerie and portentous, and sometimes humorous. She was inspired by an ‘extraordinary unearthly quality in the lonely places, in the moors and glens’ of her home country, and also the Romantics which came before her, telling stories of wildness and women.

The bonds of being dissolved and broke.

Her body she dropped like a cast off cloak.

Her shackled soul to its kindred sped.

In devouring lust with the wolves she fled.

—The Fair Young Wife

In the words of Prevallet,

‘Adam’s subversion of traditional forms […] revises traditional content with regard to gender. In most ballads, women, no matter how strong, are rarely positioned outside of domestic space. Even if they are travelling, they are still traversing a passage between one form of bond to another. In Adams’ ballads […] women are active protagonists. They are the ones who seek out their rights of passage, even if they are aided by supernatural powers.’

It took exiting Scotland for Adam to feel able to engage with the Scots language, experimenting and self-reflecting, and most of all rummaging through language in its varying forms, with the belief there was truth to find in words.

Let words be naked

As Yeats said, walking

The streets unashamed.

Let the boast and chatter

Of shop and office

Somehow disclose,

Through some poet throwing

Forked lightning

The essential secret

All language hides.

What have I exited, in order to write? What have I removed myself from in order to feed the impulse to spend time tucked away with books and thoughts and what I might make with them?

Places, spaces, people, stretching back always.

Exit by Laura Waddell is published by Bloomsbury, priced £9.99.

Through a lifetime’s experience of award-winning work in community gardens and in mental health care and training, Jan Cameron shows us how tending green spaces can bring tremendous benefits to mental health. In this extract, we look at the benefits of taking part in community gardening.

Extract taken from The Garden Cure: Cultivating Our Wellbeing and Growth

By Jan Cameron

Published by Saraband

COMMUNITY GARDENING

Community gardens come in all sorts of different shapes and sizes. Some can be several acres, others can be the size of a typical council house back garden. Some are managed as a part of a much bigger mental health, environmental or social organisation; some are national, some are small, individual and local. They can also vary in management styles. As part of a big organisation, some gardens have a paid staff team and have to adhere to company rules and guidelines, while others are managed by boards of trustees or committee and may have a very small staff team or a single worker. Then there are those that have no structure at all and are run democratically or even anarchically by a small group of unpaid individuals with no budget. They all involve volunteers and as such share a great deal of common experience. I have worked in all kinds of these settings and it is this commonality I would like to describe.

In these pages, I have distilled some of what I have observed and learnt along the way about the close interaction between horticulture and better mental health.

The garden itself is a wonderful metaphor for health. Organics in horticulture is all about creating the conditions for health rather than treating the symptoms of disease. It is easy to see the parallels with the human condition. In horticultural terms when we try to create a healthy growing environment, we look at good nutrition and regular watering specific to each plant’s needs. We need good hygiene routines, to prune out unproductive growth and concentrate energy on the healthy branches, to keep on top of the weeds, to encourage fresh air, with time to rest and room to grow and unfold safely. Does this ring any bells?

Here is just one story that illustrates how powerfully this can work. We will explore many such examples throughout the course of the book. (As mentioned before, every story and example in this book is drawn from the real experiences of different people, but I have distilled common elements of these into a single story – and I have always anonymised them.)

One morning Josh came into the garden and his body language was the picture of dejection. He wore a baseball hat firmly pulled over his face. His shoulders were slumped, his back was rounded and his eyes were downcast. He was carefully trying to avoid catching anyone’s eye or engaging with anyone. His body language was saying very clearly: ‘I am feeling very fragile and afraid. Please don’t come near me.’ When I watched him put his boots on I could see he was trembling. We knew from experience that this was not a good time to try and talk to him about why he was feeling low, so we assigned him a task in the garden as usual. His job for the day was to tie back the branches of the apple trees on the south-facing wall. Luckily, it was a warm sunny day.

Two hours later when I went to check on him he was fully engaged in the task. He was standing with the sun on his back, which was easing all his muscles, he had his arms outstretched on either side in order to reach the bits of the tree he had to tie up. His back had straightened, his chest had opened, his head had come up, he was breathing deeply and he was talking to the person standing next to him – because he had to, so that they could put the ties up together. It was like a lesson in several alternative therapies – yoga, Alexander Technique, tai chi, mindfulness, massage and talking therapies all rolled into one – AND the tree got supported and we got apples!

It’s that subtle combination of things that opens people up and helps them to talk and feel more at ease.

I refer frequently to four gardens that were also mental health services. The lessons learnt there apply just as readily to community gardens, allotment groups and indeed creative groups of many different kinds. I worked in these gardens for more than thirty-five years, and they are dear to my heart. Together, we cultivated them into healthy, thriving organic havens for people recovering from mental health problems – and indeed, as the adult ones were open to the public, they provided an oasis for anyone who came into contact with them. My hope is that these accumulated experiences may be of interest and use to you and those whom you may meet or work with, just as all gardens and all people can grow and flourish with a little attention and shared knowledge.

Throughout the book, I will refer to people attending these gardens as volunteers (with the exception of the children’s unit), and the gardens as therapeutic gardens as opposed to community gardens. By volunteers, I mean people who have made a personal choice to come to work in the garden without payment, with the hope of finding a safe space, some peace from their distress, and inspiration: places that neither look nor feel like a medical setting, but a place of work.

The gardens and the work that happened within them were the result of very dedicated and skilled teams of people who were willing to give their best. They were creative, curious, honest, and a privilege to know and work with.

I loved going to work and looked forward to every day. Even the difficult parts, like when someone was telling me about something awful that had happened to them, gave me the privilege of being trusted with something very special – despite it being about stressful and often deeply sad situations. I was always inspired by the courage that people showed. The world feels a better place to me with the knowledge that there are places where people feel safe enough to open up and share and support each other and believe in a future for themselves.

The beauty of working with people in a garden is that it is most definitely a place of work with a clear ‘firmly rooted’ agenda of ‘creating growth’ for the future. (As you may have realised by now, it is also a place that yields metaphors!) We, and others, benefit from it, but it is not about us. It’s a chance to have a break from our own problems and dilemmas and to get involved, immersed, absorbed in a completely different universe: the world of plants, the weather, nature and its many creatures. It’s both hard work and restful at the same time. After a day in the garden you feel pleasantly tired, rather than worn out. Gradually, your body becomes fitter and your mind begins to relax.

WHAT KIND OF PEOPLE COME HERE?

If I had a pound for every member of the public who came to visit a therapeutic garden and asked me this question in the last twenty-five years, I would be dining out every week. What kind of people come here? Their implication seemed to be that it couldn’t possibly be the kind of people they knew, and certainly not themselves. My usual response would be, ‘People like you and me. There is no special kind of person who comes here. We have professional people, craftsmen, teachers, doctors, plumbers, chefs, artists, manual workers, and some people who have never had paid work. We have visitors from a whole range of educational achievements, all ethnicities, religious backgrounds, and physical abilities’.

As one person in the garden noted, she had never worked with such a diverse group of people in her life. Usually we spend most of our lives with people in the same profession – whether engineers, architects, teachers, social workers or other occupations – or their client group, customers and suppliers. The mix in the garden makes for a different kind of learning experience in itself.

While out walking recently, I was thinking about this and suddenly realised that there was in fact a common denominator. People come to a therapeutic garden because they want their lives to be different. They have that very particular kind of courage that it takes to walk through the gates of a strange place and meet someone like me – someone they don’t know. Moreover, they have the courage to admit that their lives are not going the way they want them to, and that perhaps they need help to change things. I still don’t know after all these years whether I would have the courage to do that myself. The people I worked with taught me a language to describe their emotional inner journey and their recovery experience, especially when it followed a lifetime of abuse or trauma. They laid an easier path for someone who would come after them, and this helped me to work more effectively with the next person. Although we never go down the same recovery path twice, the person before often provided a gate or a stepping stone into the next person’s story, aiding a better understanding. Indeed, as everyone wore the same clothing – steel toe-capped boots and work jeans – people visiting the garden were often not aware of whether they were talking to a member of staff or a volunteer.

This book is a tribute to all those brave people and everything they were able to teach, however painful that process was for them. Hopefully many of them feel that by sharing their stories they’ve opened up possibilities for others to be helped, and that some good will have come out of their distress.

I have seen over and over how people’s lives can be transformed – put back together and changed for the better – by the richly healing rhythms of growing together in a garden.

If I contributed in any way to make the gardens I worked in better places for anyone to be in, then I feel grateful to have had that opportunity.

The Garden Cure by Jan Cameron is published by Saraband, priced £9.99

Neu Reekie is one of the best spoken word-cabaret-avant garde nights out in Edinburgh, who have taken their unique brand of entertainment across the world. Their latest volume of poetry, featuring artists who have appeared on the Neu Reekie stage, has poems and music for every mood. Here, we share poems that will tell us a little something about life, love and memory.

Neu Reekie Untitled Three

Edited by Michael Pedersen and Kevin Williamson

Published by Polygon

Ciara MacLaverty

Keeping Up with the Kids

My girl has her mission:

flour, eggs and milk, placed on the table top.

She’s donned an oversized apron; a chef’s hat.

My boy? A druid in a dressing gown, hood up,

listing 20th century icons:

Ann Frank! She wrote a diary, to make the bad stuff good.

Bill Gates? I think he invented YouTube?

She’s only half listening to her brother,

their elbows knock in the full-length mirror.

She swishes her hair, sticks out a hip

by the strip of fairy-lights. I flip the crepes:

portions equal. Or it’s goodnight.

He kicks invisible balls high into the air,

and lists footballers now:

Ronaldinho, Maradona. Kevin de Bruyne.

Try-outs on the tongue. Poetry for wee boys.

Dad’s been gone 7 weeks.

Hong Kong to New York and everywhere in between.

Our kitchen clock sneaks. Drums keep the beat.

Each of us moves about the room,

each to their own tune. Whatever it takes

to mark these patient, keepie-uppie days;

waiting for him to come home again.

Gratiagusti Chananya Rompas

new galaxy

at the dining table i think perhaps it is now time to look for another galaxy. a

bowl of kidney bean soup looks like stardust. the dim kitchen makes me long to

be engulfed in a cosmic stream of lights. we speak about a motel named after a

bird and about the local optometrist. about respect and milkshakes. and finally

about the house renovation that’s taken ages to start. a ghost clings around my

ankles like an invisible ball and chain, so hard to shake off. where will your

adventures take you. a freshly decorated living room right out of a magazine,

where your friends and family quietly have their tea and cakes, or a distant

planet where the air is fresh, filled with promises of victory for humankind, or

simply another place for you to die. anywhere but here. a more meaningful

death, but a death nevertheless. once the last cockroach flips over on its back

and stops moving, no one will ever eat a bowl of kidney bean soup again. and

stardust will stay afloat in space, as if no one from this earth has ever made it

out alive.

Ian Macartney

The Bookshop I Burned Down

Here was Uncle George’s shelf.

Magnus in ashes. Here was

Alasdair Gray’s Lanark,

illustrations like black leaf.

Here was a stroke of genius

(useless dancing dust).

Here was another ur-text,

fire as its summary.

Here was Tony Kushner’s stuff,

the origin of a course

I could never take.

Now all of Scottish culture

is stained with your lack of tears,

anti-blots that block writing

progress. Walking through spaces

safe from money (museums, etc.)

become funeral marches

to the peace I felt when, leaning

slightly in Rose Street’s record-shop,

our shoulders brushed. Pecked.

You tolerated it. You awwed.

I still try to capture that birdsong.

Kevin Williamson

Roddy Lumsden is Somewhere

And here we are, reading his thoughts.

Arranged like purple orchids in a vase

on a boutique wooden crate coffee table.

Leaves reaching out, petals unfurled.

He was a crossword with missing clues.

Sonic the Hedgehog eyebrows. Disdain.

My favourite stanza was the Oyster Bar

where we entered a midweek pub quiz.

There is no collective noun for a Lumsden,

a Reekie & a me. He winced when Paul

or myself chipped in with a plausible guesstimate

which inevitably proved wrong.

He wasn’t always patient, with other men.

We came third. Won a bottle of citric wine

whose origin & age he surely despised.

But fair play to him. We prised it open on

the spot & clinked two glasses per poet.

I raise mine high to an omnium-gatherum,

an olla podrida, a gallimaufry, of good ole

bars that never change, to poets who

wear button down shirts of khaki. Prost!

Leyla Josephine

the good stuff

the smell of garlic, grass, petrol, pals, poems that make you weep, tits, you

filling your arms with me, the way town looks at christmas, the moon and how

it always comes back, expensive pens and red swimsuits, diving in, hair long

enough finally to tie in a pony, plaits, armpits, elbows, pubic hair, collar bones

and bellybuttons, all in and all out, all bodies of water, all bodies of sky, the

sound of cereal hitting the bowl, freckles, constellations, scalding hot hot water

bottles, the smell of the rubber reminds me of my mother, someone to take

your temperature, sweat in summer, dew, snow, fruit pastel ice lollies, things

that fizz, child’s pose, happy baby, learning how to say no, finding your glasses,

your keys, your phone, your vibrator, pictures of you when you were a child, the

mosh pit, the war ending, people saying sorry and meaning it, singing together,

how easy forgiveness comes, patterned wallpaper, flamingos, penguins, whales,

kissing strangers on dance floors, the cha cha slide, your friend’s bed, laughing

with their loves, bookshops, libraries, printers that are working, postcards,

handwritten letters, hotel rooms and the orgasm on the freshly made bed,

blackheads, cliffs, the edge, the chain, fleetwood mac, islands, horizons, eating

fish and chips, skin, your period finally coming, waking from deep long sleeps,

blood coming out of the sheets, satisfying sentences, the tongue of your home

town, windows, oh i am grateful for windows and grandmothers and family and

finishing books, a film that sticks on you like a stamp, finding a painting that

is more like a mirror, backpacks, bikes, wheels, circles, bats, birds, weddings,

stretching, reality tv, the top of mountains, contact lenses, the right shoes, all

dogs and their ears, oranges, easy bowel movements and drivers waiting for

passengers running for the bus.

Watch the Neu Reekie online launch video on the Neu Reekie YouTube channel:

Neu Reekie Untitled Three, edited by Michael Pedersen and Kevin Williamson is published by Polygon, priced £12.99

Monstrous Regiment are a new micro-press worth paying attention to, releasing books that shine a light on ideas and start conversations that are needed. Their latest release is a collection of essays that explore the many issues surrounding hormones, and here, we share one of those essays, which looks at period poverty.

‘blood is back’ by Rachel Grocott is taken from So Hormonal

Edited by Emily Horgan and Zachary Dickson

Published by Monstrous Regiment

blood is back

how my knowledge and experience of periods were revolutionised while i wasn’t having them

by Rachel Grocott

I started freelancing for Bloody Good Period (BGP), the charity which provides period products to refugees, asylum seekers, and those who can’t afford them, when I was six months pregnant – so I had already been period-free for half a year. My periods returned when my son was just over a year old, meaning that for a good 18 months, while I was busily scheduling menstrual-themed art, writing period-related captions and reading every bleeding-related news piece around, I wasn’t actually having them myself. And when they did come back, they found me a rather different person to the one who had tentatively started writing about all things bloody, all those months before.

Like many people, I used to see periods as a complete pain, practically and literally. I certainly never thought much about the products I used, only whether I had enough (and how much chocolate to buy alongside my ‘feminine hygiene’ supplies – more on that naming convention later). I only had a vague concept of the problem of period poverty. Now I understand more of its reality, its prevalence, and its impact, particularly on refugees and asylum seekers – people who’ve already suffered indescribable trauma. It affects others too, of course: schoolgirls, the homeless, people affected by austerity – basically, anyone who can’t afford or access period supplies in this crazy world which allows big companies to make big money out of a biological function. Now I understand that to not have to worry about my period means that I have a very particular kind of privilege.

Research by Plan UK has shown that one in ten girls in the UK have been unable to afford period supplies. The issue of affordability is amplified for people living in any kind of vulnerable situation, including asylum seekers, who receive just £37.75 per week to live on, and (contrary to what many mainstream media outlets would have you believe) are generally not allowed to work. A heavy period can cost a quarter of that allowance, and the trauma of displacement (and possibly far more) means that this group is even more likely to suffer from irregular and heavy bleeding. As Marie, an asylum-seeking woman based in Birmingham, told BGP: ‘The stress of destitution changed my menstruation cycle. I was so worried about where we would eat, what would happen, I began bleeding more often’.

Gabby Edlin, BGP’s founder and CEO, started Bloody Good Period when she realised that drop-in centres (organisations offering a safe, welcoming, and supportive environment for refugees and asylum seekers, and practical support including food and other supplies) had simply not factored in menstruation. Most were not routinely giving out supplies, either at the frequency required or at all – that is, every single bloody month. So she set about collecting pads, and the rest is history. We are now partnered with 50 drop-ins across the country, giving out over 1,500 products per month. We estimate to have taken care of 60,000 periods.

This is a bittersweet set of figures. Whilst it is amazing that we can offer this support to people who would otherwise be unlikely to access these most basic of products, we shouldn’t have to. We shouldn’t have to rely on an act of charity for people to be able to manage their bleeding. We shouldn’t have to encourage people to donate products by describing how other humans would otherwise have to use socks, newspaper, loo roll, or nothing at all.

We also passionately believe that this isn’t just about giving out free products. For the past year, we have been piloting our education programme, getting vital menstrual and reproductive health information to the people we work with who, again, would otherwise be unlikely to access it. This is the kind of information we should all have access to, but most people have never had a comprehensive education about periods. Instead, we’ve had advertising campaigns aimed at making bleeding feel dirty. ‘Freshen up with our pads’, says this big corporation, ‘use our rustle-free wrapper’, shouts another. No wonder most societies have an impressive number of euphemisms for periods, everything from ‘shark week’ to ‘Aunt Flo’, and probably a load more you’ve never heard of. Many people struggle to say the word itself.

At BGP we set out to tackle this head on as well. We call the pads we collect ‘period products’, or ‘period supplies’. Or how about just ‘pads’? They are not, and never will be in our book, ‘sanitary’ or ‘feminine hygiene’ products. These delightful terms co-opted by those classic marketing campaigns are just another of the many layers of shame and embarrassment over periods. As Jane Garvey brilliantly put it on the Woman’s Hour podcast recently, you don’t find a ‘masculine hygiene’ aisle in Boots, do you? I’ve now started to understand how these layers have been present in my life and nearly everyone else’s, whether they have periods or not. Whether it’s the boys being sent out of the room for ‘the talk’ at school, or comments on social media about why women can’t just ‘hold it in’ (yes, really). The level of ignorance and stigma surrounding periods is astounding. But I just hadn’t thought about it before. I was, albeit unwillingly, complicit in it before.

Now I display my BGP sticker-adorned laptop on the train with pride, and talk to my friends about it – it turns out they’re quite happy to chat periods, too, because periods are actually pretty normal, and a widely shared experience. Having a baby, as I have recently done, is another shared experience: celebrated and rewarded, the details discussed over coffee or wine (okay, often wine), chatted about with other people in the playground, yet having periods is hushed up, seen as something disgusting, cloaked in euphemism. But the more we talk about it, the weaker the taboo becomes (to paraphrase Sally King’s ‘weak taboo’ description of menstruation). It’s my hope and intention that my five-year-old daughter is never embarrassed by her body functioning healthily, yet I also know that it’s easier said than done. Years of conditioning (i.e. a lifetime, and on top of that a few more generations’ influence through older relatives) don’t disappear overnight, and I recently had to challenge myself not to brush away my daughter’s questions about why I was bleeding. She didn’t overly care, as she wanted to get back to playing – always her priority – but I know my answers now will add up to important feelings about this later on.

My awareness has changed in other ways too. Whilst I knew the biological basics of what a period was before, now I realise my knowledge was pretty one-dimensional: it didn’t include any understanding or questioning of how it might affect my skills, sociability, energy levels, mood, and, well, my whole life each month. Or that it’s not just about the blood bit, but what happens during the rest of a menstrual cycle too. Thanks to learning about writers such as Maisie Hill through BGP, I now have a far better knowledge of what the hell is actually going on each month. I was even excited to start tracking my periods and symptoms and for once, it didn’t come as one of those ‘ohhhh’ moments when my period started. I understood how to listen to my body. Moreover, I understand that periods are a reflection of your health – indeed, many writers (including Chris Bobel and Maisie Hill) now describe how the menstrual cycle should be considered our fifth vital sign, an indicator of an individual’s health and wellbeing as much as temperature, pulse, breathing rate, and blood pressure. Understanding all of this can help you live a more informed and empowered life – something which is both fundamental and powerful. I will still be buying loads of chocolate (always), but I’ll be doing other things too, like supplementing with magnesium (for cramps – it seemed to help for the first one back, which can be notoriously tricky post-baby) and actually giving myself permission to rest (shocking).

But why isn’t this knowledge more readily available to everyone? Why aren’t we all taught about this at school? Everyone who has periods should be able to understand what is happening, and how to work with it each month. Everyone who cares about anyone who has a period should be able to do the same, so they can understand, empathise and support. Instead, we have a society that brushes periods under our collective and metaphorical rug and worse, marginalises people who have them, and then makes money out of them on top. It’s time to turn that craziness on its bloody head. My personal experience also shows that it’s not just period knowledge we need. Like many people who experience pregnancy, I rode a complete hormonal rollercoaster when my baby started reducing the amount he was breastfeeding, and my periods returned. Also, like many, I experienced anxiety and low mood, yet found that this topic is little talked about, under-researched, and too often dismissed. And that, of course, is all part and parcel of the much bigger problem of ‘women’s issues’ being side-lined, ignored, only seen as outliers. I was just as horrified to learn that some (not all, but some) doctors still dismiss sickness in pregnancy – yet pregnancy and having children is so revered and celebrated (it’s just all the messy stuff that comes with it that needs to be hidden away). Our society uses the term ‘hormonal’ as an apology and often as an insult too, and that’s another heap of craziness that needs to be turned around.

I fully recognise, of course, that I write all of this from a place of incredible privilege. I’ve been fortunate enough to have access to a whole load of inspiring and empowering information through my work; but before that, despite having a privileged upbringing, I had nowhere near enough information or support, something which is true of a vast majority of menstruating people in the UK. After all, nearly half of people in the UK don’t know what’s happening to them when they get their first period.3 That issue is writ large for the people with whom BGP works, and for anyone vulnerable in a society which has marginalised menstruation and the people who experience it. That urgently needs to change. The panic-buying of period products during the COVID-19 outbreak only underlines how essential period products are – but vulnerable people, including asylum seekers receiving £37.75 per week, can’t bulk buy anything. Neither can they routinely access the kind of information I’ve described here.

That’s why Bloody Good Period is not just about ending period poverty, and not just about giving out pads (as vital as that service is). We are for menstrual equity: a society in which the simple biological fact of bleeding doesn’t hold anyone back from participating fully in society, or in life. Or, more simply, a society where everyone has a bloody good period.

What next?

- Bloody Good Period (bloodygoodperiod.com) – Bloody Good Period gives period products to those who can’t afford them, and provides menstrual education to those less likely to be able to access it.

- Periods Gone Public by Jennifer Weiss-Wolf

So Hormonal, edited by Emily Horgan and Zachary Dickson is published by Monstrous Regiment, priced £11.99

Sue Black’s first book, All That Remains, won the Saltire Literary Award for Non-Fiction and made its readers think about death in a new way. She carries on this most necessary task in her new book too, and BooksfromScotland caught up with her to find out more.

Written on the Bone: Hidden Stories in What We Leave Behind

By Sue Black

Published by Doubleday

Congratulations on the publication of Written on the Bone. Reading your work, you clearly relish your experiences as an expert forensic anthropologist. Do you remember when you first started to be fascinated by the stories our bodies tell us?

I was always interested in biology from school days and in school found the lessons on human anatomy particularly interesting as they related to me and the others around me. At university, it was always the human element of study that appealed the most and when in my third year of undergraduate studies I was given the opportunity to dissect a human cadaver from the top of the head to the bottom of the toes – I was hooked for life. My research project in my fourth year looked at identification from the human skeleton and so the dye was set.

And has this fascination deepened with time? Is that what drew you to writing about your life’s work?

The honesty about my writing is that I wanted to leave a legacy in my own words about my life so that my girls might understand me better when I am no longer here. Somebody asked me which book I would like to read the most and I realised that it was one that would never be written. It would be about my grandmother’s life but she never wrote it down and now there is nobody left to tell it. I wanted to leave something for my children and their children and beyond. I was truly astounded by how much the public took to my writing and that has been an incredibly humbling process. I love my job now as much as I ever have and feel blessed that I have been able to do something so interesting. been reasonably good at it, and got paid for the privilege.

Your job has taken you to many interesting places. What has been the most unexpected aspect to your job?

It would seem terribly trite to say that everything in the job is unexpected and much of the time it is. No two cases are ever the same and no two disasters are ever the same. I am always astounded by how much kindness there is and how willing people usually are to help you do your job.

What story can you get from someone who, luckily like BooksfromScotland, has never broken a bone?

This is an essay question and in fact I wrote a whole book about it 🙂 The minimum you hope to recover is: Are the remains human? Who were they? How long have they been dead? Are there clues about the way they lived and the way they died. Then within each of these sections there are different subsets such as: Were they male or female? How old were they when they died? Always lots and lots of questions and you don’t know which ones will have answers until you start the investigation of the remains.

Your experiences are a gift to a novelist! Are you constantly battling off requests from crime writers for help?

There are a few. Of those I help it is either because they are new to the field and are desperate for realistic help or they are friends who I have assisted for a number of years.

What do you hope readers will take away from your books, especially during a year where health and death have been so present?

Health and death are always present and we don’t talk about death anywhere near enough. It is an inevitability but we postpone discussions often until it is too late. I would feel I have succeeded if people can become more comfortable to talk about their own death and that of others. Also I am aware that many of us know very little about our own anatomy and so I wanted to be able to start that conversation. It is one that we have at the GP or in the hospital, but much of the time people have limited anatomical language or understanding of their own bodies.

What do you like to do when you’re not studying bodies and bones?

I am the Pro Vice Chancellor for Engagement at Lancaster University and so with my research, my forensic case work, senior management responsibilities and writing – there isn’t a lot of spare time.

Which writers inspire you?

I like all sorts of authors. I am a Ken Follett fan but I also love Rachel Joyce and have just finished her latest. I love the way Sarah Langford write with her honesty and I am a huge Tolkein fan.

What books have you particularly enjoyed reading recently?

I have just finished Rachel’s Miss Benson’s Beetle and my next one is about the history of the sugarhouses in Lancashire.

Written on the Bone: Hidden Stories in What We Leave Behind, by Sue Black is published by Doubleday, priced £18.99.

As the founder and CEO of Mary’s Meals, Magnus helps feed and educate millions of children in 18 different countries across the world every year. In his new book, Give, he explores what charity means, and how it works, for both individuals and organisations.

Extract taken from Give: Charity and the Art if Living Generously

By Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow

Published by William Collins

‘… when all violence subsides in the human heart, the state which remains is love. It is not something we have to acquire; it is always present and needs only to be uncovered. This is our real nature, not merely to love one person here, another there, but to be love itself.’

MAHATMA GANDHI

When we feel bruised and battered by events – like the scandalous things that took place in Haiti or other mistakes of our own making – we need, first of all, to remind ourselves why: why are we doing this? Why is our charity so precious and so needed? We need to convince ourselves once again that the risk is worth taking. Because, make no mistake, every authentic act of charity – whether we make it as individuals or as an organisation – involves an element of risk: the risk of our gift being misused by the homeless person or the charity we donate to; the risk that the project we support does not, in the end, manage to solve the problems it set out to solve; the risk that our charity’s reputation is torn to shreds by the misdemeanours of a member of our staff ; the risk that one day we will not be able to raise the funds required to keep our precious project afloat and end up breaking our promises to vulnerable people. Such risks, along with our own mistakes and the criticisms we receive – both constructive and destructive – will require us to remind ourselves why. At times of crisis and disenchantment – and at many other times too, even before we attempt to learn from our mistakes and chart a way forward – we need to remind ourselves why. Why did we set out on this journey? Why should we keep going? We cannot ask these questions too often in our pursuit of charity.

*

Sometimes, even when we have thought we were leading the way with a new project, we have discovered that spontaneous charity has beaten us to it. And that has been good – a reminder that our role is only to steward that charity in a way that lets it fl ourish and grow and bear all sorts of fruit.

In the late 1990s, towards the end of one of Liberia’s civil wars, we began to accompany some of the Gola people, returning from years of exile in displaced camps, back to their villages in Bomi County. There they discovered that their homes were now overgrown ruins and that there was a new forest growing where their fi elds used to be. We tried to help them in various ways by providing machetes for them to clear the encroaching bush, tools to start rebuilding homes and food supplies until they could start growing and harvesting their own crops once again. In addition, we supported a mobile health clinic which began to serve remote villages with a team of local nurses and cases of medicines. Each Tuesday we visited Massetin, a leper colony where the people had been suffering terribly without any healthcare for many years during the war. Unlike the surrounding villages, Massetin had largely been left alone by the warring soldiers, whose terror of contracting leprosy led to them giving the place a wide berth, and therefore the people here had stayed while other villages emptied.

In Massetin we came to know a young man called Massaquoi and learnt his story. He had had to flee for his life from his own home village during the war. Eventually, as he stole in terror through the thick forest, he came by chance upon Massetin. He decided to stay there and began to tend to the lepers, who were at that time living in desperation. When the war ended he never left, continuing to help them as best he could. He was overjoyed when our clinic began to visit, and in time we provided him with training so that he could become a key member of our team.

We thought our little clinic was a particularly intrepid initiative, helping people in places far beyond the reach of other organised help. But of course, we discovered in Massetin that long before we arrived, charity was already at work and that, in the form of Massaquoi, heroic goodness was alive and well and ready to become part of something more organised. Experiences like that have left me feeling that it is a little odd that an organisation like ours is called ‘a charity’. We are a body established with the purpose of encouraging and making effective the acts of charity performed by individual people. We are not charity itself. Organisations do not perform acts of charity – individual human beings do. It is certainly possible, and expected, that the individuals who comprise an organisation like ours carry out acts of charity, but it is equally possible to work for a charity and not practise it. I can certainly be guilty of that. I do not want to get stuck here on semantics, nor am I proposing a change to a long-established terminology which I use myself, I raise it only because I feel it might correspond to certain wrong attitudes we can adopt when working for a charity. There can be a tendency to think we are ‘in charge’ in the wrong way, or even that we are the prime movers, when – certainly in the case of a grassroots movement like Mary’s Meals – we are the servants of people’s goodness rather than the leaders of it: we are enablers rather than key actors; we are joiners of dots rather than creative geniuses; and we are stewards rather than owners.

Give by Magnus MacFarlane-Barrow is published by William Collins, priced £16.99.

The Case of the Catalans lays out the historical, legal, political and economic aspects behind the present conflict between Catalonia and Spain, exploring why so many Catalans are no longer happy to be part of Spain. This extract presents a summary of the growing popularity of the independence movement, and a timeline of events that shows how the relationship between Catalonia and Spain has changed over the years.

Extract taken from The Case of the Catalans: Why So Many Catalans No Longer Want to be Part of Spain

Edited by Clara Ponsati

Published by Luath Press

The reasons behind the surge in support for independence

While for many in the international arena the Catalan pro-independence demands are new, secessionist groups have existed in Catalonia for at least the last 100 years. However, for the larger part of that period, explicitly pro-independence positions were never dominant within Catalan nationalism.

This is especially true for the post-Francoist period. Ever since the restoration of democracy in 1978, mainstream Catalan nationalism has sought compromise with Spain in order to achieve a gradual increase in devolved powers, rather than full separation. Even the parties that had self-determination and independence in their manifestos took part in the compromise strategy, and sought negotiations for increased autonomy.

This was congruent with the preferences of the population. When asked by the CEO, the Catalan Centre for Opinions, about their preferred constitutional arrangement in 2006, only 14 per cent of respondents chose secession as their first preference among four options – centralisation, status quo, federalism or secession. However, when the same poll repeated the question in 2013, the number had skyrocketed to 48.5 per cent, stabilising later on around 40 per cent. When asked directly about their vote in a potential referendum, around 50 per cent declared that they would favour independence.

However, this abrupt change obscures a more stable feature of Catalan public opinion: even if often falling short of demanding full independence, a majority of Catalan citizens have favoured full decentralisation ever since autonomous institutions were restored. This widespread demand for more autonomy was already over 60 per cent in 2002, according to a survey fielded by the Spanish governments’ Sociological Research Institute (CIS). Since then, those that believe that Catalonia has an insufficient level of autonomy have stood at around around 65 per cent of the population, according to the CEO surveys.

This is crucial, because it sets the preconditions for the shift towards secessionism. In 2005, the Catalan Parliament had passed the proposed reform of the Statute of Autonomy, and as we have discussed in Chapter 3 the response of both the PSOE and PP to this caused great frustration for Catalan voters. President José Luís Rodríguez Zapatero reneged on his promise to support it, imposing major amendments for its approval in the Spanish Congress. Rajoy, then leading the PP, challenged the Statute before the Spanish Constitutional Court, which four years later ruled against key parts of the text, thus further limiting autonomy.

That ruling of the Constitutional Court is often regarded as a key tipping point for the evolution of demands for independence in Catalonia. Moreover, it was further aggravated by the recentralisation strategy that the Popular Party implemented after it formed a government in 2011. Taking advantage of the Great Recession, the Rajoy government imposed a tight financial control on the autonomous communities that, in practice, suppressed any remaining financial autonomy.

These episodes – from the amendments and later ruling against the Statute of Autonomy passed by the Catalan Parliament, to the recentralisation policies set up by the PP government between 2011 and 2018 – illustrate a core concern for those that support Catalan self-government: the lack of guarantees in the Spanish constitutional framework. The state institutions, from the executive to the legislature and the judiciary, have ample margin to limit and water down the powers of the Catalan government and parliament. One of the goals of the 2005 statute passed by the Catalan Parliament was to set a system of guarantees to protect their autonomy from central interference, but that was rejected by the central power.

In the wake of the Constitutional Court decision and the Popular Party policies, the segment of the population that wanted further decentralisation faced a stark dilemma: either accept the status quo of limited, decreasing and insecure autonomy, or shift to a more radical demand for self-determination and full independence from Spain. This explains why a growing number of federalists started to support the idea of separation.

If we order the constitutional preferences in a continuum between full centralisation and full independence, the bulk of the electorate has for a long time been located somewhere in between the status quo and full independence. However, as the status quo moved backwards, towards recentralisation, these voters found themselves gradually moving closer to independence than to the status quo. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that a substantial proportion shifted towards independence.

How can we explain this realignment in such a short period of time? Alternative explanations have been put forward. The first one links the pro-independence movement to the general reaction to the financial crisis that was especially acute in Southern Europe. During the period of 2008 to 2014, the rate of unemployment in Catalonia and support for independence were strikingly parallel.

In a general sense, one could argue that the crisis did indeed play a role. First, it provided the Spanish government with the opportunity to pursue a recentralisation of financial powers. Second, we have some evidence that some of the new supporters of independence were motivated by instrumental concerns related to the negative net fiscal flows between Catalonia and Spain, and infrastructure under-investments of the Spanish government in Catalonia. The idea that the Spanish government’s fiscal and economic policies had a negative impact that probably amplified the effects of the crisis in Catalonia became relatively widespread.

However, under closer scrutiny, the empirical facts do not support the idea that the crisis was the primary or key driver of the movement. There are at least two reasons. First, because once the crisis ended around 2014 and both Spain and Catalonia recovered the path of economic growth, the movement did not fade away as one would have expected if the crisis were its driving force. On the contrary, the movement intensified, organised the referendum in October 2017 and reached its record-high number of absolute votes at the December 2017 Catalan elections, with 2.1 million. Second, there is no correlation at the local level between the growth of the pro-independence vote and increases in unemployment.

A second explanation, very widespread in Spain, attributes the surge in support for independence to nationalistic indoctrination through the Catalan schooling system. However, the empirical evidence does not support this idea either. The shift towards independence support was not the result of generational replacement, but happened in a relatively homogeneous way across generations. The magnitude, speed and generational composition of the shift is not compatible with the idea of school indoctrination. Indeed, there is no clear empirical relationship between age and independence support, except those over 65 – the only group in which those with pro-union views consistently outnumber pro-independence supporters by about 8 percentage points.

There are also reasons to think that the surge was not primarily driven by changes in national identity, as suggested by the indoctrination hypothesis. National identification is usually measured in Catalonia through a scale in which respondents express their self-identification as ‘Only Catalan’, ‘more Catalan than Spanish’, ‘More Spanish’ or ‘Only Spanish’. The proportion of those with exclusive Catalan identities was relatively stable around 20 per cent, and increased up to 30 per cent in an abrupt way by the end of 2012. This was not a progressive change that preceded the surge in support for independence, but rather a quick increase that, if anything, followed the shifts in constitutional preferences. Moreover, the share of those that support independence is consistently over 10 percentage points higher than those that self-identify as only Catalans.

Therefore, we can regard the surge in independence support among Catalan citizens as a reaction to the political context. The perception that further autonomy was not possible within Spain, and the trend towards recentralisation by Spanish central authorities led a large number of Catalan voters to shift towards demanding full independence.

Timeline of Catalonian history

From 878 – The Counts of Barcelona begin to distance themselves from the Carolingian Empire.

1137 – The Count of Barcelona marries the heir to the Aragonese Crown. It is the start of Catalonia’s history within the Aragon Crown, but with a Catalan lineage (‘Casa de Barcelona’ – the House of Barcelona). The first mentions of the term Catalonia appear during this period.

1359 – The Generalitat de Catalunya is established, with a president and one of Europe earliest parliaments.

1410 – Martí l’Humà, the last king of the House of Barcelona, dies with no heir.

1412 – In the Casp compromise representatives of Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia meet to vote in a new royal house. They decide, by majority, to appoint Ferdinand of Antequera, a member of the Trastamara house, the family that holds the Castilian crown.

1469 – Ferdinand of Trastamara, heir of Aragon, marries Isabella, the heir of Castile. He becomes king of Aragon in 1479.

1474 – First printed book in Catalan appears.

1516–7 – Ferdinand is succeeded as King of Aragon by his grandson Charles, from the Habsburg dynasty.

1517–1700 – The Habsburg monarchs rule as kings of the separate Aragonese and Castilian Crowns. Within Aragon, they swear to separate Catalan constitutions.

1640 – Catalan Revolt against the Spanish monarchy.

1641 – Pau Claris, 94th President of the Generalitat, proclaims the brief Catalan Republic under the protection of France.

1650 – War ends when Spain and France sign the Treaty of the Pyrénées, in which Catalonia loses its northern territories.

1700 – Charles II, the last Habsburg king, dies without heirs. Philip V, grandson of Louis XIV of France, is crowned king.

1705 – War of the Spanish Succession, that pitched the Bourbon Kings of France and Spain against all of Europe’s other major powers, supporting Archduke Charles, a Habsburg claimant to the Spanish throne. The Catalans side with Habsburg in defence of their traditional autonomy.

1713 – As Archduke Charles becomes Holy Roman Emperor, he loses much of his support. The British resolve to end the war and sign the Treaty of Utrecht that settles the new distribution of powers in Europe and the colonial world. Abandoned, Catalonia keeps fighting.

1714 – Barcelona falls to the Bourbons after a 14-month siege on 11 Sept – thereafter celebrated as Catalonia’s National Day.

1716 – ‘Nova Planta’ decree issued. Catalonia loses its constitutions and is administered from Madrid and in Barcelona through Captain Generals. The Catalan language is suppressed. From then on, Catalonia is ruled as a Spanish region rather than a distinctive entity.

1808–14 – Following Napoleon’s invasions of Spain, Catalonia is governed as a province of the French Empire between 1812 and 1814.

1810–27 – Spanish American Wars of Independence. Spain loses most of its colonial Empire as its colonies in Central and South America gain independence.

1868–73 – Spain seeks a new monarch, and invites King Amadeo, from the Italian Savoy dynasty, to take the throne. He rules Spain from 1871 to 1873.

1873 – The First Spanish Republic is proclaimed, but is overthrown by the army just a few months later in 1874.

1898 – Spain is defeated by the United States in the Spanish-American War. This results in Cuba gaining independence, and Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines being annexed by the United States.

1901 – Formation of the bourgeois Catalan Regionalist League, supporting autonomy, not independence.

1914 – Limited self-government returned to Catalonia under the leadership of Enric Prat de la Riba.

1923 – Miguel Primo de Rivera imposes a military dictatorship in Spain. Catalan self-government and language suppressed once again.

1931 – With the collapse of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, the second Spanish Republic is proclaimed. In Barcelona, Francesc Macià briefly proclaims a Catalan Republic, but renounces it in order to lead the autonomous Catalan government.

1934 – Following the election of a right wing Spanish government new Catalan president, Lluís Companys, declares independence. However, this regime is suppressed by the army and Companys is jailed.

1936 – The left-wing Popular Front government elected in Spain. Catalan autonomy is restored.

1936–9 – The Spanish Civil War rages between the Nationalists and Republicans, supported by Catalonia. The Nationalists are victorious, allowing General Franco to establish a dictatorship.

1939–75 – Francisco Franco rules over Spain. Democracy, Catalan culture and autonomy are suppressed.

1975 – Francisco Franco dies and Juan Carlos I is declared King of Spain.

1976–7 – Adolfo Suárez is appointed Prime Minister and Spain begins its transition to democracy. In 1977 it holds its first democratic elections since the Second Republic.

1978 – Spain’s new democratic constitution is approved by a referendum. Catalonia’s autonomous institutions are restored.

1980 – Catalonia holds its first elections to the re-established Catalan Parliament. Jordi Pujol’s CiU win and remain in power until 2003.

2003 – The CiU loses power to a left-wing coalition of the socialist PSC (led by Pasqual Maragall) the ERC and ICV.

2005–6 – A new Catalan Statute of Autonomy is passed through the Catalan Parliament in 2005, and approved by a referendum in Catalonia in 2006. The Spanish Constitutional Court begins deliberations on the new Statute. The Popular Party organises a Spain-wide campaign against any changes to the Constitution.

2010 – Spain’s Constitutional Court rules the proposed new Catalan Statute of Autonomy unconstitutional. Large demonstrations against this decision are held in Barcelona. The CiU return to power in the Catalan government under the leadership of Artur Mas.

2012 – Catalan government makes plans for a ‘consultation’ on Catalan independence.

2014 – The Spanish Parliament and Constitutional Court both reject plans for an independence referendum. A consultative referendum is held regardless – drawing over 2.3 million votes, 1.9 of which support independence in the midst of a boycott by anti-independence groups.

2015 – The CiU and ERC form an alliance, ‘Junts pel Sí ’, to contest a snap Catalan election, which they hope to use as a plebiscite on independence. This alliance, alongside other pro-independence groups, gains 47.8 per cent of the vote and an absolute majority of seats in the Catalan Parliament. The new government declares that start of a ‘process’ towards independence.

2016 – Artur Mas steps down as President of the Catalan Generalitat in favour of Carles Puigdemont, with the support of Junts pel Sí and the far-left CUP.

2017 – Catalan referendum on independence held. 2.3 million votes are cast out of a total electoral roll of 5.3 million – anti-independence groups again boycotted the vote, with 2 million favouring independence. The Catalan government declares independence. The Spanish government suspends the Catalan government and either arrests or forces into exile a number of pro-independence leaders. New Catalan elections are called, yet pro-independence groups secure another majority.

2018 – Three attempts to elect a new Catalan President fail over the course of several months as the candidates are either in exile or prison. Joaquim Torra is eventually elected as Catalan President and a new government formed. PP loses motion of no confidence and PSOE takes Spanish government.

2019 – Trial against independence leaders at Spanish Supreme Court. Spanish snap election called in April and repeated in November. Both deliver a blocked Congress.

The Case of the Catalans, edited by Clara Ponsati is published by Luath Press, priced £7.99.

Michael J. Malone has carved out a successful niche in dark domestic thrillers that delve beneath the veneer of supposedly happy families. His new novel, A Song of Isolation, throws the underbelly of celebrity into the mix, to give us a story full of his signature twists and turns. He tells BooksfromScotland more in the video below.

A Song of Isolation

By Michael J. Malone

Published by Orenda Books

A Song of Isolation by Michael J. Malone is published by Orenda Books, priced £8.99.

This autumn we have more books being released than ever before. As ever, BooksfromScotland is here to highlight the best new releases and brilliant independent publishing in Scotland. Our publishers have much to offer, including fiction, childrens’ books and non-fiction that will make you see Scotland anew, to stories and ideas from around the world, showcasing our publishers’ international outlook. We’re sure you’ll find something here to delight, inspire, provoke and entertain!

Click through the covers and titles to purchase or find out more on each book.

If you’re looking for . . . FANTASTIC FICTION

Whirligig, Andrew James Greig

Published by Fledgling Press, £9.99

Shortlisted for 2020 William McIllvanney Prize for Crime Fiction

Longlisted for the 2020 CWA John Creasey New Blood Dagger Award

Whirligig is a tartan noir like no other; an exposé of the corruption pervading a small Highland community and the damage this inflicts on society’s most vulnerable.

The Shadow King, Maaza Mengiste

The Shadow King, Maaza Mengiste

Published by Canongate Books, £16.99

Longlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize for Fiction

This is an utterly captivating novel about female strength. Set during Mussolini’s 1935 invasion of Ethiopia, The Shadow King casts a light on the women soldiers written out of African history.

‘UNFORGETTABLE’ The Times

‘A MASTERPIECE’Washington Post

Dead Girls, Selva Almada

Dead Girls, Selva Almada

Published by Charco Press, £9.99

Almada narrates the case of three small-town teenage girls murdered in Argentina in the 1980’s. This is not a police chronicle, although there is an investigation. This is not a thriller, although there is mystery and suspense. The real noir element of Dead Girls lies in the heart of the women described here and of the men that have abused them. With her unique style of prose that captures the invisible, and with lyrical brutality, Almada manages to blaze new trails in this kind of journalistic fiction.

Marriage, Susan Ferrier

Published by ASLS, £14.95

Susan Ferrier has been described as the ‘Scottish Jane Austen’, and Marriage is her best-known novel, a witty and satirical examination of female lives in the Regency era.

This edition, edited and introduced by Dorothy McMillan captures the humour, sensitivity and elegance of the original bestselling novel, and gives Ferrier her proper place among Scotland’s notable writers.

Bloody Scotland, Various Authors

Published by Historic Environment Scotland, £8.99

In Bloody Scotland, twelve of Scotland’s best crime writers use the sinister side of the country’s historical landmarks in stories that are by turns gripping, chilling and redemptive.

Stellar contributors Val McDermid, Chris Brookmyre, Denise Mina, Ann Cleeves, Louise Welsh, Lin Anderson, Gordon Brown, Doug Johnstone, Craig Robertson, E S Thomson, Sara Sheridan and Stuart MacBride explore the thrilling potential of Scotland’s iconic buildings, statues and locations.

Diverted Traffic, Avril Duncan

Diverted Traffic, Avril Duncan

Published by Tippermuir, £8.99

Set in Amsterdam, India, and Edinburgh, Diverted Traffic tells the story of Suman, a nine-year-old girl who is stolen from her village in India, trafficked and taken to work in the sex industry in Amsterdam.

The author uses her own experience of working with the victims of human trafficking and sexual slavery in Pune, Maharashtra to give us a novel packed with emotion, excitement and detailed knowledge of poverty in rural India and counterfeit Scotch whisky – strange and uncomfortable bedfellows until the story’s triumphal end.

Vargamäe, A H Tammsaare

Vargamäe, A H Tammsaare

Published by Vagabond Voices

Translated by Inna Feldbach and Alan Peter Trei

This monumental work by Estonia’s greatest writer is a European classic which has for too long been neglected in the English-speaking world, and tells the story of how Tsarist Estonia developed into the First Republic through the experiences of one family who struggle through poverty first in the country and then the city.

Alindarka’s Children, Alhierd Bacharevevič

Published by Scotland Street Press, £11.99