Alistair Braidwood has been a fan of Edwin Morgan and his work since he was a teenager, here he tells us why Edwin Morgan means so much to him and why we should investigate his brilliant work.

Feature portrait taken by Jessie Ann Matthew and belongs to the National Galleries of Scotland.

James Kelman, Liz Lochhead, Alasdair Gray, Tom Leonard, Janice Galloway, Iain Banks – these are just a few writers who made me realise at a formative age that people like me, mine, and those around me, belonged on the pages of books, and that our culture and language was legitimate. This is hopefully beyond any reasonable argument today, but even in the dying embers of the 20th century it was much less certain. Those named above did as much as any to challenge and change the situation, but before them all there was Edwin Morgan.

The first poem of his I read was ‘In The Snack-bar’. Not many lessons from my less than comprehensive education have stayed with me, but just thinking about it transports me to that snack-bar with the sights, sounds, and smells that Morgan evoked so powerfully. The desperate plight of the blind man with his ‘dismal hump’ and face hidden, the voyeuristic nature of the onlookers, and the decidedly uncomfortable relationship between young and old, contrasting hope for the future with resignation approaching defeat – Morgan captured the picture perfectly with the keen eye of someone invested in the lives of others however, and wherever, he finds them. It takes something special to grab the attention of a 14-year-old for whom poetry till that point was little more than a song lyric or amusing graffiti on a toilet wall, but here it was and Morgan and his poetry would never leave me.

Charming, challenging, intellectual yet intimate, humorous and humble, his work is all of those things and more, inspiring widespread adoration and devotion for a poet that is rare. I have found him to be revered by people who claim not to read, or even like, poetry, and many who admire his work talk about it in hushed awe as they might a favourite band who they want to keep secret – he belongs to them, he is their poet. When enough of the population claim you as “their own” before long the inescapable conclusion is that you have come to belong to the nation, and there is no doubt that applied to Edwin Morgan. Despite life-long links to his home town of Glasgow he was undoubtedly a poet of national, and international, importance and it was no surprise when, in 2004, he was named Scotland’s first National Makar. Arguably there was no other choice.

Part of the reason for this was not only the quality of his work, but also for a literary longevity that is quite astonishing. Morgan’s peer group consisted of writers at work throughout the 20th century, and beyond. He is one of the subjects of Sandy Moffat’s famous painting ‘Poet’s Pub’ (1), alongside Norman MacCaig, Hugh MacDiarmid, Sorley Maclean, Iain Crichton Smith, George Mackay Brown, Sydney Goodsir Smith, and Robert Garioch, a collection of writers often referred to as the forefathers of the Scottish Literary Renaissance, and whose influence on Scottish culture endures.

At the age of 82, Morgan worked with Scottish indie darlings Idlewild on their seminal 2002 album The Remote Part (2). Being involved in this sort of collaboration again seems a result of his innate interest in others, and particularly the work of fellow artists. He was constantly seeking out the new, and was only too pleased to support those who were up-and-coming. As a result he remained relevant with subsequent generations discovering him anew, believing that he spoke to and for them. Morgan retained a youthfulness and vitality even in later life that few could hope to match.

As late as 2007 he was involved with the album Ballads of the Book (3) alongside writers such as A.L. Kennedy, Laura Hird, Alan Bissett, Rodge Glass, Louise Welsh, and others who came to prominence in the 90s or later, their work adapted by a variety of musicians. Morgan’s nearest contemporary on the project, at least age-wise, would be Alasdair Gray, (14 years his junior), someone who shared this ability to appeal across the ages.

Over the years I have continued to read and return to Edwin Morgan’s poetry with a mixture of affection and reverence – the scope and breadth of his work never failing to impress, from the early collections such as The Vision of Cathkin Braes and Other Poems, through experimental concrete poetry of the 60s, the sonnets, numerous translations into Scots (Cyrano de Bergerac a personal favourite), and so much more. However, for all his variety, and mastery of form and subject, it is his reflections on the subject of love where he truly excelled, with poems such as ‘One Cigarette’, Strawberries’ or ‘Absence’. Poignant, insightful, and often heart-breaking, few have managed it better. Edwin Morgan’s legacy is one of peace, love, and understanding and it’s one we would do well to heed.

1: ‘Poets’ Pub’ is on display now at The Modern Portrait exhibition at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery.

2: Idlewild’s The Remote Part was released on Parlophone.

3: Ballads of the Book was released on Chemical Underground

Scotland was a subject that inspired much Edwin Morgan’s work, and this year Val McDermid and Jo Sharp used Scotland as their muse when putting together Imagine a Country: Ideas for a Better Future, a brilliant collection of essays, published by Canongate Books, from writers from all walks of life pondering on the possibilities of life, work, love, and a whole lot more, in a future Scotland. Here we share an essay on climate change and collaboration, and you can also catch the digital launch of the book starring Val, Jo and other contributors.

Extract by Lyndsay Croal, Cameron Mackay and Eilidh Watson taken from Imagine a Country: Ideas for a Better Future

Edited by Val McDermid and Jo Sharp

Published by Canongate Books

No one is too small to make a difference. This is the key message from the burgeoning youth-climate movement that first began in 2018 and has since swept across the world. Nobody would have guessed that a teenager from Sweden would be the catalyst for a global political movement that intends to hold the polluting neoliberal system accountable for the damage it has caused for generations. A system left unchecked and unanswered for decades. Whilst Greta Thunberg is just one voice amongst many climate activists from across the world, together these voices are united. We would like to imagine that this is just the beginning. The beginning for Scotland and for the world.

As part of a contingent of young geographers with the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, we had the pleasure and privilege to travel to Sweden to present Greta with the Geddes Environmental Medal in the summer of 2019. We travelled across land and sea, brought together with other environmental activists by our shared goal of addressing the climate emergency and our passion for telling stories. Over the course of the journey, we discovered the diversity of our ideologies, faiths, identities, but that together, this diversity made our approach stronger. Similarly, the process of writing this piece collaboratively is exactly the sort of collaboration we imagine and hope a future Scotland would adopt: we want to be part of a country that takes into account every voice and is therefore able to make a greater impact than the sum of its parts.

When we met Greta, Scotland had been hailed as a world leader in climate-change action, even before passing the responsible and ambitious climate legislation it adopted later in 2019. However, the measure of leadership is changing and so Greta’s message to Scotland was clear: every country must act, and every government must do more. Many argue that as a small country, Scotland’s emissions are insignificant in comparison to other nations. But we believe that climate change is everyone’s responsibility and it is irresponsible to accept no blame for a problem to which we, as a nation, have contributed. Currently the impacts of climate change are disproportionately borne by poorer countries and communities. Often the people most vulnerable are those who have contributed least to the human causes of climate change. This injustice is just one of many reasons to make a change.

Today there are glimmers of what a positive future could look like in Scotland. From community energy and a flourishing renewables sector, from shared allotment space for local food production to circular resource- and tool-sharing networks, we have the knowledge we need to move forward. Scotland has the potential to continue on this path, to invest in a better future and to become an example of what sustainability that works for everyone looks like. It is not too much to imagine a future where inclusive, welcoming and sustainable communities lie at the heart of our culture.

So, we imagine a country that has embraced the shared message from Greta Thunberg, global activists and our own home-grown Scottish climate campaigners.

We imagine a future Scotland that prioritises climate justice; a Scotland that is not afraid to stand up for those that are voiceless.

We imagine Scotland leading the world by example: empowered by an inclusive, innovative and sustainable society whilst at the forefront of challenging some of the biggest problems facing the world today.

We imagine Scotland’s land delivering benefits for nature, biodiversity, climate and society. A Scotland with a clean and affordable energy and infrastructure system that is just and provides benefits for all.

In that future, we will have listened for solutions not only from politicians or businesses, but from the younger generations, minority groups and others who have traditionally been separated from decision-making.

The way we structure our economy will be tied to a global green agenda, and Scotland will continue to be at the forefront of forging that path internationally. Just as no one person is too small to make a difference, no single country is too small to make an impact and bring forward change.

Lyndsey Croal, Cameron Mackay and Eilidh Watson are the current editors of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society’s Young Geographer magazine. Eilidh is a PhD researcher focusing on climate, energy and gender justice issues, based at the Centre for Climate Justice, Glasgow Caledonian University, Cameron is a documentary filmmaker with a focus on environmental stories and also works in the Scottish sustainability sector, and Lyndsey works for WWF Scotland in Edinburgh on environmental and climate-change policy and writes in her spare time.

Imagine a Country: Ideas for a Better Future is edited by Val McDermid and Jo Sharp and published by Canongate Books.

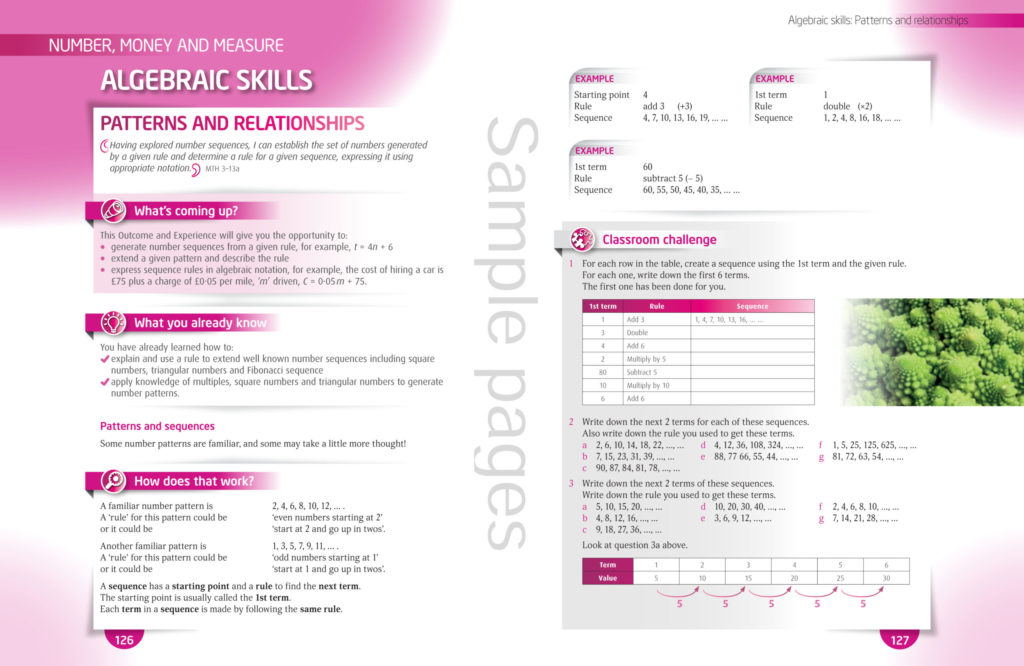

BooksfromScotland are sharing Scottish publishers’ online resources for parents and teachers homeschooling their children. Here, we shine a spotlight on the excellent educational publishers Hodder Gibson and Leckie & Leckie.

Leckie & Leckie

Leckie, and parent company Collins publish books and online learning resources for ages 3-18. To help families continue learning at home during school closures, we have made hundreds of free books and resources available on collins.co.uk/learnathome. These include more than 300 ebooks from the Big Cat primary reading programme, activity sheets, a times tables practice tool, a primary music programme, and free resources for National 4 and 5, Higher and Advanced Higher students.

Leckie are known for their resources for the Scottish curriculum, from Early Level to Advanced Higher – student and pupil books; teacher handbooks; and revision and practice for a range of subjects, to be used in class and at home. These include the bestselling Success Guides for National 5 plus new Student Books and Complete Revision & Practice revision resources for Higher.

The Leckie Primary Practice Workbooks for Maths and English are ideal for learning at home – topic-based practice for each year that reinforces your child’s learning and supports the Scottish curriculum.

Have a peek at some of their Primary School Maths and English Practice books.

Visit their website to access FREE learning resources for children ages 3 – 16 years old! There’s reading guides, times table practice, a song bank and much, much more!

Hodder Gibson

Hodder Gibson publishes the widest and largest range of textbooks and revision guides in Scotland – including the award-winning How to Pass series – and is the home of TeeJay Maths, Scotland’s No. 1 Maths publisher. They have won the Times Educational Supplement Scotland/Saltire Society Award for Educational Book of the Year eight times! They publish books focussing on the Scottish Curriculum for Excellence, providing resources for primary schools, secondary schools and FE colleges as well as continuing professional development for Scottish teachers. We also publish a growing number of electronic support materials for interactive learning.

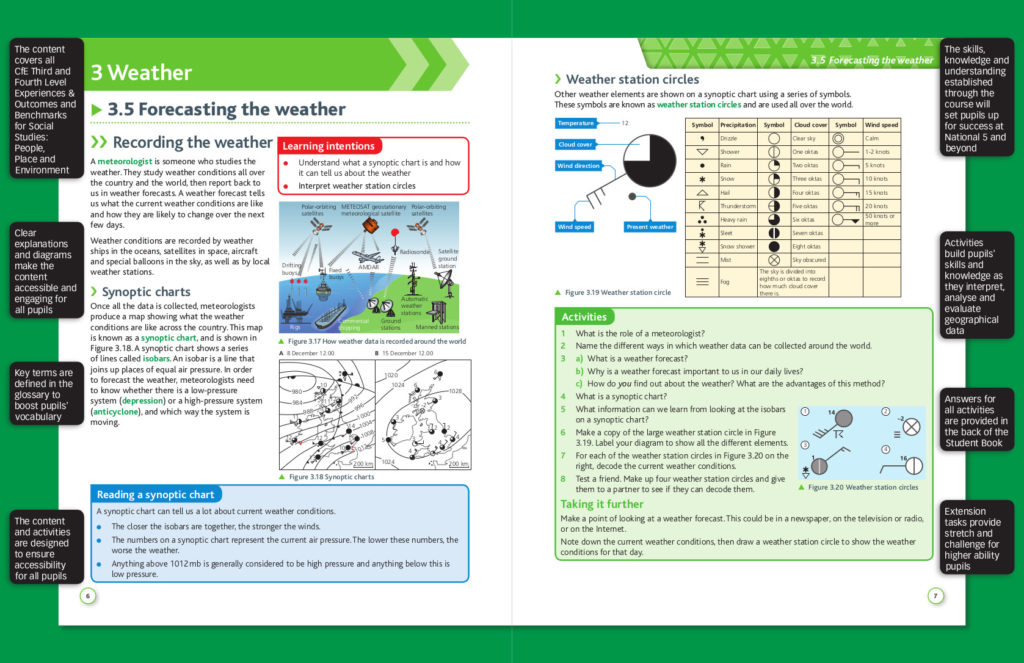

Here’s a sample of their book BGE S1 – S3 Geography

Want more? Here are sample pages of:

Essential SQA Practice Exams

Need to Know: Higher Modern Studies Revision Guide

Visit Hodder Gibson’s website here.

For more information on free online resources, follow the #UnitedByBooks hashtag. This marvellous #UnitedByBooks project is coordinated between Scottish Book Trust, BookTrust, Authorfy and Coram Beanstalk.

We highlighted Martin MacInnes’s Gathering Evidence at the start of the year in our Who we’re Watching in 2020 feature. Alistair Braidwood discovers that the novel has never been so timely.

Gathering Evidence

By Martin MacInnes

Published by Atlantic Books

There is little doubt that the time and times in which you first encounter a book will have no small influence on what you read into it and its effect on you. Re-reading William Golding’s Lord of the Flies and J.D. Salinger’s Catcher In The Rye as an adult was a world away from the impact they made to my teenage self. Similarly, when I read Sunset Song at the same young age I hated it, or more likely didn’t understand it. Reading Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s classic again as a 28-year-old first-year university student, it hit me like a hammer. Because of how they made me feel at the most impactful time of reading all three remain among my favourite books.

Reading Martin MacInnes’ Gathering Evidence as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold across Europe was an unsettling experience – one which I doubt will ever leave me. This is a novel that would pack a punch no matter when read, but to say it seems prescient in its timing and content is to seriously undersell it. The world is in a state of high anxiety – the atmosphere foggy, unclear, the earth noxious, potentially virulent, and its inhabitants have to deal with information and mis-information overload, struggling to work out what is real and what is imagined. Paranoia and mistrust are inevitable.

Divided into three parts, it opens with ‘NEST’ a short chapter that concentrates on a mobile computer app that monitors patterns in individual behaviour in a manner not dissimilar to those found on many modern smartphones, and just as addictive. However, what we see is a future when such technology is taken to its extreme conclusion. It’s a short story in its own right but also works as an overarching and contextual prelude as to what is to unfold.

In a conservation area known as ‘Westenra Park’, primatologist Shel Murray and a team of analysts and observers arrive to investigate two mysterious deaths in the last known troop of Bonobo chimpanzees. From the beginning the project appears cursed as they lose a key member before even entering the unnamed country, are given strict rules and regulations by shady corporation WEBG, struggle with the realities of life in dense jungle, and are made to feel less than welcome by both people and place. As the survey begins in earnest you begin to ask who is studying who, and why.

Meanwhile, Shel’s partner John, a computer programmer and coder, is left at home and looking forward to getting their new house ready for her return. After a brutal attack he is left disorientated and damaged in ways he can’t quite comprehend. His memory is badly impaired, his wounds refuse to heal, and his only contact is a doctor who doubles as his warder as he is kept under house arrest. His confusion during this time is keenly felt, and, as with Shel, it appears that he is being observed and examined, part of an experiment the reasons for which are never clear.

The two stories are linked beyond the relationship of the main protagonists. Despite being a considerable distance apart they both find they are being changed and challenged physically and mentally. Shel takes ill, clearly affected by the extreme environment, particularly the surrounding plant life that seems to have infected her, but also the stress of being stalked by an unseen predator. At the same time she is trying to understand and explain the patterns of behaviour of her simian subjects, something which in turn reflects back on her. John is also forced to cope with nature gone wild as a strange fungus spreads throughout their house creating an environment that can only hinder his recovery. In both cases you are asked to comprehend not only what is happening, but also who or what could be behind it. The evidence builds but to what end?

Reunited in part three ‘Place Beyond The Forest’ (‘stay away from the trees’, might be sage advice for the couple) Shel and John try to deal with the fallout from their recent experiences, as well as coming to terms with a brand new one. It is pointed that their stories remain mostly separate despite there being good reason for them to unite, and it feels like trust and faith, in each other and possibly themselves, has been lost. There are mysteries at all levels, from the global to the individual, with no easy answers and only further questions.

Gathering Evidence is impossible to truly pin down – part sci-fi, part paranoid thriller, part body horror, where Michael Faber’s Under The Skin meets Alan Trotter’s Muscle with a dash of David Cronenberg. More than any other novel I can bring to mind it is as much about sensation as it is story, and its success is all down to Martin MacInnes’ writing which is nothing less than breathtaking. Describing an alien environment in all but name, at times the imagery is so rich, even fetid, that you can almost taste it. As if viewed through a high-powered microscope, insects, fungus, disease, and decay, are rendered beautifully, and that results in an appreciation of MacInnes’ writing that encourages empathy where there could have been revulsion or nausea. It would be fascinating to re-read the book in future, but right here and now it’ll shake you, and your world, to the core.

Gathering Evidence by Martin MacInnes is published by Atlantic Books, priced £12.99

As we spend our days indoors during the COVID-19 measures, BooksfromScotland will be sharing online resources from our brilliant educational and childrens’ publishers. Here, we shine a spotlight on the brilliant Bright Red and Barrington Stoke.

Bright Red Publishing

Bright Red publish the brightest, freshest study guides and course books for Scottish Qualifications Authority exams. Easy-to-use and with plenty of exam hints and tips, their books offer the best study and revision support for BGE, National 4 & 5, CfE Higher & Advanced Higher courses.

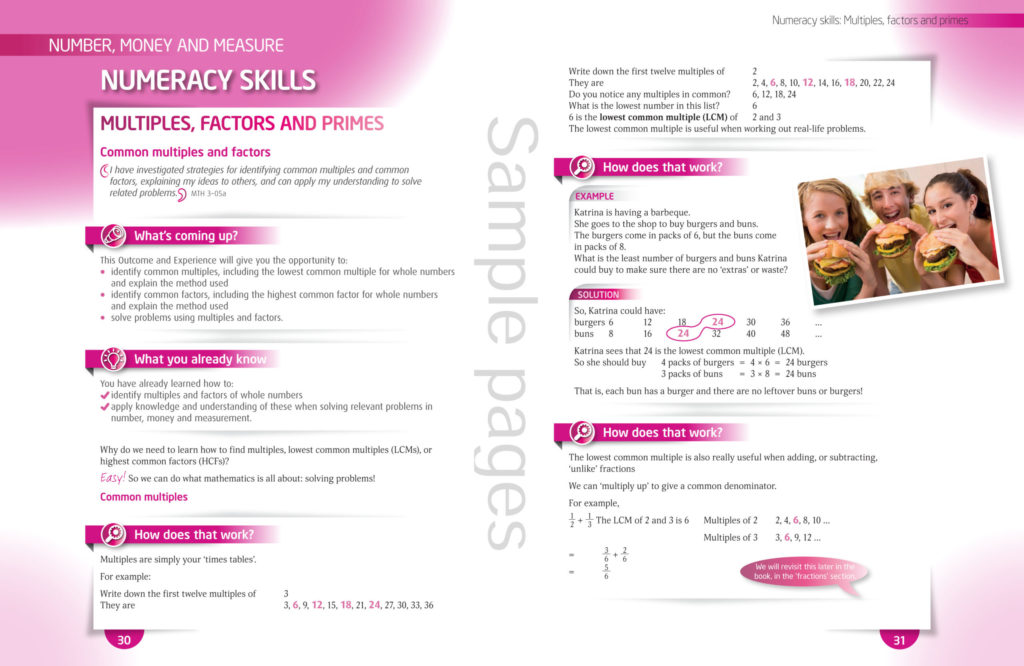

They’ve just released a BGE Level 3 Mathematics Course Book, and you can see below for a colourful sample.

There are more samples of all of their guides on their website. As well as samples, BrightRed host the Bright Red Digital Zone, a fully interactive online resource for teachers and pupils. All Digital Zone material is completely free to use and works well on its own or in conjunction with their study guides. With over 100, 000 active users and 1.5 million tests taken, it uses the very latest technology to help students learn in the most rewarding way possible.

Visit Bright Red’s website here.

Barrington Stoke

The multi-award-winning Barrington Stoke is a small, independent and award-winning children’s publisher. For over 20 years we’ve been pioneering super-readable, dyslexia-friendly fiction to help every child become a reader. Their books are written by some of our biggest bestselling, award-winning authors, including Michael Murpurgo, Malorie Blackman, Andy Staton, Julia Donaldson and many more. One of their latest books is Tanya Landmann’s brilliant retelling of Jane Eyre. The author tells BooksfromScotland about this project here.

And here’s an extract.

I was not loved.

I was not wanted.

I did not belong.

I lived with my aunt and cousins, but I was not welcome in their house. My parents had died when I was a baby, and my uncle took me in. He didn’t live much longer than they had. I don’t remember any of them.

My strange story starts on a wet winter’s day.

There was no chance of taking a walk, and I was glad of it. I never liked being out with my cousins. They had rosy cheeks, golden hair, and brimmed with the kind of confidence only money can buy. They would stride ahead as we walked, and I’d be stomping along in their shadows. I was small, shabby, and the nursemaid nagged me at every step. The chilly air bit deep into my bones, but what bit even deeper was knowing I was disliked.

That clamped its teeth right down into my soul.

The wind blew so hard that wet winter’s day the rain fell sideways. No one dared set foot outdoors. My cousins were in the drawing room, clustered around their dear mama. She lay on the sofa, basking in the fire’s warmth like a well‑fed pig.

I’d been told to go away. I was banished from their company for some sin or other, I don’t know what. I asked my aunt what I’d done wrong, but that just made things worse. Children were not meant to question their elders, my aunt said. It was unnatural. Odd. Children were meant to be cheerful and charming. And if they could not be cheerful and charming, they should at least be silent.

Very well, I thought. I walked into the next room and shut the door behind me. I took a book from the shelf, climbed on to the window seat and pulled the curtains across so I was hidden from sight.

I was all right until my cousin John came looking for me.

John was fourteen years old. He’d been kept home from school these last few weeks because his mother feared he’d been exhausting himself. My aunt adored her son John: he was an angel fallen to earth in her eyes. A genius with the soul of a poet and the heart of a saint. Never has a mother been so mistaken.

John was a selfish bully who cared little for his mother and less for his sisters. I was his one passion. He hated me. John attacked me not two or three times a week, or once or twice a day, but continually. I was four years younger and half his size. Every nerve in my body feared him. Every inch of my flesh shrank whenever he came near.

I heard the door open and I froze. John was not intelligent or observant. He wouldn’t have seen me at all if one of his sisters hadn’t pointed out my hiding place. He came in, ordered me from the window seat and demanded, ‘What were you doing?’

‘Reading,’ I replied.

‘Show me the book.’

I placed it in his hands.

‘You’ve no right to take our books!’ John said. ‘You’re an orphan, a beggar! You’ve no money. You should be on the streets, not living here at Gateshead, eating our food, wearing clothes my mother has paid for. I’ll teach you your place. Go and stand over there, by the door.

Barrington Stoke have a learning resource to match Tanya Landmann’s Jane Eyre here.

The Barrington Stoke website is also chockful of free online resources for teachers, parents and pupils. Find out more here.

Visit Barrington Stoke’s website here.

For more information on free online resources, follow the #UnitedByBooks hashtag. This marvellous #UnitedByBooks project is coordinated between Scottish Book Trust, BookTrust, Authorfy and Coram Beanstalk.

Britain’s nuclear deterrent has always been a hot topic, and in W. J. Nuttal’s thought-provoking history, Britain and the Bomb, he gives a great overview on the government’s strategy during the Cold War. Here he tells us what to expect from his book.

Britain and the Bomb: Technology, Culture and The Cold War

By WJ Nuttal

Published by Whittles Publishing

This book tells a historical story centred on the mid-1960s, a point in history when the UK made its important decisions about the Bomb. The UK has made crucial decisions about nuclear weapons at four points in its history. There was the late 1940s decision to develop plutonium-based atom bombs similar to the Fat Man weapon dropped by the Americans on Nagasaki, Japan, which helped bring the Second World War to a close a bit sooner than might otherwise have been the case. The next decision came in the 1960s. It was to transition the British nuclear deterrent from primarily a Royal Air Force-delivered capability to a Royal Navy submarine-based approach, deploying US Polaris missile technology. The third decision concerned the upgrading of that system through the 1970s with the Chevaline upgrade – a uniquely British idea.

A fourth decision came in the early 1980s with the shift to the Trident submarine-launched nuclear weapons system. A fifth major decision is at the time of writing being implemented – via the construction of a successor system to the original Trident capability. We consider stories from the 1950s and 1960s in order to understand the present better. One observation from those years is how for Britain the threat-space moved from a global set of confrontation points, particularly including the Middle East and the Far East, to become a more narrowly European, North Atlantic and Arctic story.

Since the end of the Cold War, however, Britain’s areas of defence emphasis have broadened once again, particularly to the Middle East and central Asia, but also to include West Africa. The global reach of British power is an area where ambition and obligation collide with the realities of tight budgets.

This book describes Britain during a period of perceived international decline, retreating from Empire and losing independence of action in defence and security. It was also a time of renewed prosperity at home, social change and post-war optimism. It provides an insight into a Britain of the past, one that is many ways so very different from the Britain of today, but one which can give us insights into, and perspectives on, contemporary choices. The issues surrounding Trident replacement are often presented in the British press as a choice concerning Britain’s ‘independent nuclear deterrent’ – and indeed it is. Arguably, however, that is not its raison d’etre. It is also a contribution to NATO strategic security and, perhaps most importantly of all, a British investment sustaining and strengthening security guarantees from the United States. Would the United States really risk its very existence to defend interests on the other side of the Atlantic? The existence of British nuclear weapons arguably affects that calculus, to the benefit of Britain. Such connections and linkages emerged during the Cold War, and in particular the years described in the pages that follow.

This book is a story from the past, one that has resonances for the present and focuses on a different, earlier, period. Yes, it was a dangerous time – but it was also a fun, exciting time for many people. It is the story of a generation emerging from the dismal rigours of the Second World War into a new and optimistic high-technology future. But while this book concerns itself with nuclear weapons, their ethics and destructive potential are not our focus. Rather the intention is to evoke a lost Britain and to reflect on what we might learn from it. Much of my story pivots on a single military project: the TSR2 aircraft. The label ‘TSR2’ stood for ‘Tactical Strike and Reconnaissance 2’, and this was the most ambitious military aviation project ever conceived by the British. It was wonderfully, and recklessly, ambitious. It represented national aspiration verging on hubris, and in early 1965 it was cancelled. Only one aircraft ever flew – and that aircraft, XR219, went supersonic only once.

My analytical opinion is that the TSR2 cancellation was a wise and carefully handled step. It was a sensible decision in Cold War defence policy. It was a correct and timely move in the Cold War game. This book will help explain the choices made, and perhaps reassure those that see error and even conspiracy. The defence decision makers, however, did not fully realise that the choices they were making would start a redefinition of Britain in the spring of 1965, and in those terms it was a very sad decision indeed. The emotion of the story is important. The TSR2 cancellation was a decision that becomes sadder as time passes. It appears to affirm national weakness and a retreat from ambition. It suggests that Great Britain has become Britain. Looking at the story in such terms, it appears to represent a mistake of long-term significance made for narrow, short-term motives.

On such matters, however, the author leaves the reader to judge.

Britain and the Bomb: Technology, Culture and The Cold War by W. J. Nuttal is published by Whittles Publishing, priced £18.99.

Cathy Golke uses history and world events to write novels that seek to offer inspirational lessons, and her latest, The Medallion, is no different. Set against the backdrop of the Polish ghettos during the Second World War, it’s a novel that looks at the heartbreaking decision of a family to send their daughter into hiding to keep her safe.

Extract taken from The Medallion

By Cathy Golke

Published by Muddy Pearl

Summer waned and the first crisp days of autumn bit the air, but still Itzhak had not returned. Rosa had risked going to the house of the man arranged to pose in Itzhak’s stead, to beg for news. But there was none. Pani Leja sent slim packages of food that the man brought back to Rosa through the ghetto gate, tied to his leg beneath his trousers, but nothing had been heard or seen of Itzhak since he’d left.

By the end of September, Rosa was frantic. The money Itzhak had saved was gone, despite her careful rationing of every penny. Her ration book was allowed only because of the hand sewing she took in – the repair of German uniforms.

Late one afternoon, Rosa pulled the latest cheese packet from beneath her coat and unfolded its edges. The note, written inside the paper, came as a death sentence.

- looking for I.

That was all, but Rosa knew what it meant. The Sturmbannführer had come looking or sent someone looking for Itzhak. It was a wonder it hadn’t happened before now. What it meant for her, for her mother, for her daughter, didn’t bear imagining. A pounding could come at their door any moment. There was no way to know.

Matka’s shadow crossed the table. She still had the strength to carry Ania in her arms – Ania, who weighed almost nothing. ‘What is it?’

‘They’ve gone to the Lejas, looking for Itzhak.’

‘What will they do?’

‘What do you think? They will come here next. One day.’

Rosa wanted to tear out her hair. She couldn’t think that, couldn’t imagine Ania being torn from her arms, her head smashed in the street. ‘Give me my daughter.’ She pulled the little girl from her mother’s arms and cradled her, roughly, beneath her chin. Ania whimpered.

‘That woman, Jolanta, came again today.’

‘Did she bring medicine? Ania’s cough is better, but with winter coming –’

‘She’s taking children out of the ghetto. She wants to take Ania.’

Rosa closed her eyes. She’d heard that the nurse – the Polish social worker – smuggled children from the ghetto and found them homes, safe houses, on the Aryan side. She’d met her once or twice when she brought food. That seemed a lifetime ago.

I would never have considered it before … but now, what if they come for me? What will happen to Ania, to Matka? Rosa swallowed, doing her best to keep her voice steady. ‘This is the last food Pani Leja will send. Even now she may be in Pawiak, or dead, because she helped Jews …’

‘We will manage. We have always managed.’

‘We won’t manage if the Gestapo comes. They will take me away at the very least. You and Ania would be left alone – with nothing. I can’t let that happen to my daughter.’

‘We can only wait and see. Perhaps they won’t come. If they do, we’ll make them understand – say that Itzhak deserted us. We don’t know where he is.’

‘We are playing Russian roulette, Matka! They will come for us. In their eyes we are useless mouths, feeders off their society.’

‘Rosa, Rosa.’ Her mother sat heavily at the table beside her. ‘What can I say to you? What can I do?’

‘Nothing. That is it, there is nothing you can do … but I beg you, do not try to stop me from doing what I must.’

Her mother grimaced but turned away, saying nothing. Rosa didn’t have the strength to try to convince her. She would need every ounce to give up her child.

*

In the morning, Rosa slipped the medallion Itzhak had given her on their wedding day from her neck. Using a chisel and hammer left in Itzhak’s toolbox, she carefully cut the medallion in half. Filing the cut filigreed edges smooth, she wound a short length of gold chain from her mother’s necklace through the split branches of the Tree of Life. The medallion and gold chains were the only things of value the women had not sold – gifts meant for the generations to come. Rosa crimped the chain closed and placed the half medallion over Ania’s head, around her small neck. Let this remind you you are not alone, my love. One day, we will be together again, mother and daughter, whole.

When Jolanta appeared at Rosa’s door, Rosa was there and ready.

‘I keep a list,’ Jolanta began, ‘of all the children’s Jewish names and the Aryan names they’re given. I keep a list of all the addresses, so after the war we will be able to reunite families.’

Jolanta was speaking, saying words that Rosa would only dissect later. She knew the young woman meant well, that she and her friends risked their lives to save the children of the ghetto, but Rosa had no idea if the woman believed her own speech. Reunited after the war. As much as she wanted to believe that, Rosa could not. Still, to save her daughter’s life was all that mattered now…

The Medallion by Cathy Golke is published by Muddy Pearl, priced £14.99.

William Mitchell was a sculptor, artist and designer, known best for his large scale murals and public art pieces in the 1960s and 1970s. Whittles Publishing have released a fully-illustrated autobiographcal study of his life and work, excellent reading for those interested in mid-century architecture and design.

Self-Portrait: The Eyes Within

By William Mitchell

Published by Whittles Publishing

In Bill’s own words, ‘This book describes a few events in my early life and then concentrates on my attempts to produce art over the past 50 years’. It actually contains a vast array of illustrations of Bill’s work and in so doing reveals the man – a true creative genius, who invariably had a smile or comic story to offer, and whose energy carried projects to completion despite the many challenges. It’s a brilliant and inspiring story.

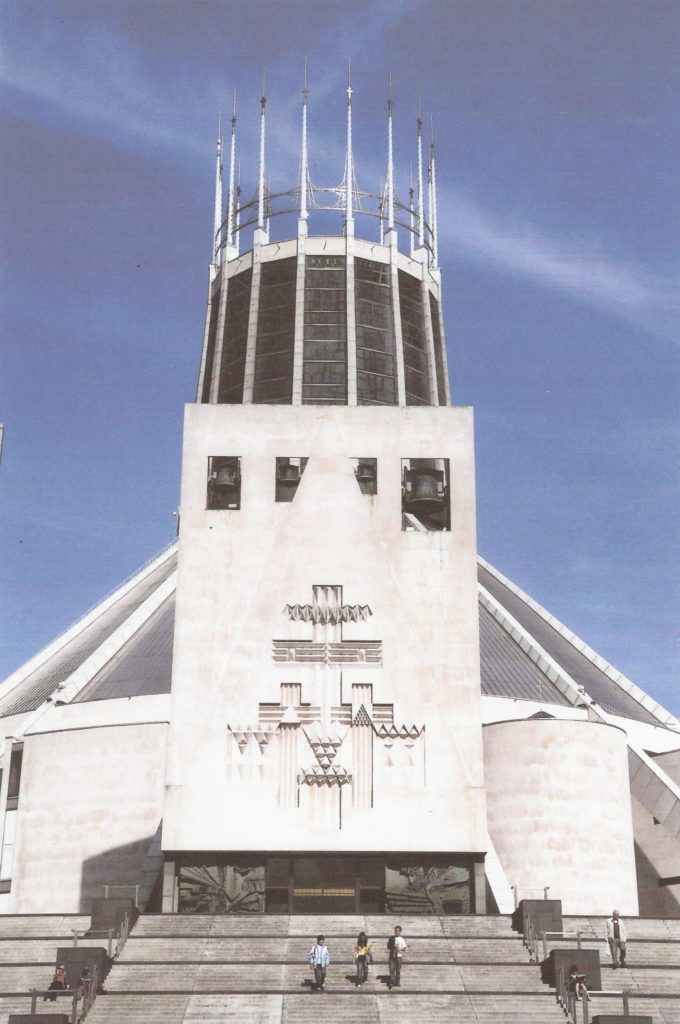

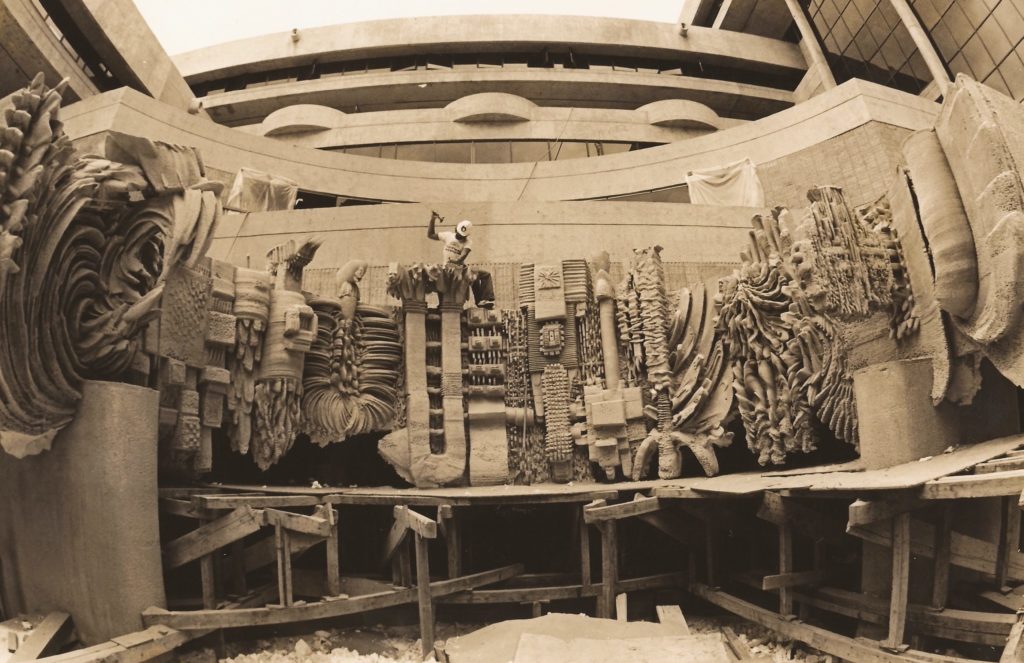

He worked with famous architects of the day such as Basil Spence and Sir Freddie Gibberd who designed the Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King where Bill created the famous bronze sculpted doors and designed the Portland Stone frontispiece.

The façade of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King showing Bill’s design carved in stone, a symbolic representation of the crucifixion, three crowns and three crosses. The largest represents Christ and the smaller ones on either side the thieves. Beneath are the doors created by Bill, 12 feet square, and made of bronze-finished glass fibre. Huge cranes were required to lift all these components into place. Below is the left-hand door, with winged lion and eagle detail. The image from the front cover is part of the right-hand door.

He also produced the Stations of the Cross at Clifton Cathedral, Bristol and the Grade II listed Corn King and Spring Queen figures at Wexham, which are ‘pieces of powerful and bizarre imagination’.

The Corn King and Spring Queen – fertility ceremony in concrete. Daring works of art for their time, even in the 1960s. The figures were made in stages and different finishes applied, including the incorporation of mosaics, tiles and coloured glass.

He has had a total of nine works of art listed Grade II by English Heritage including the Corn King – more than any other artist.

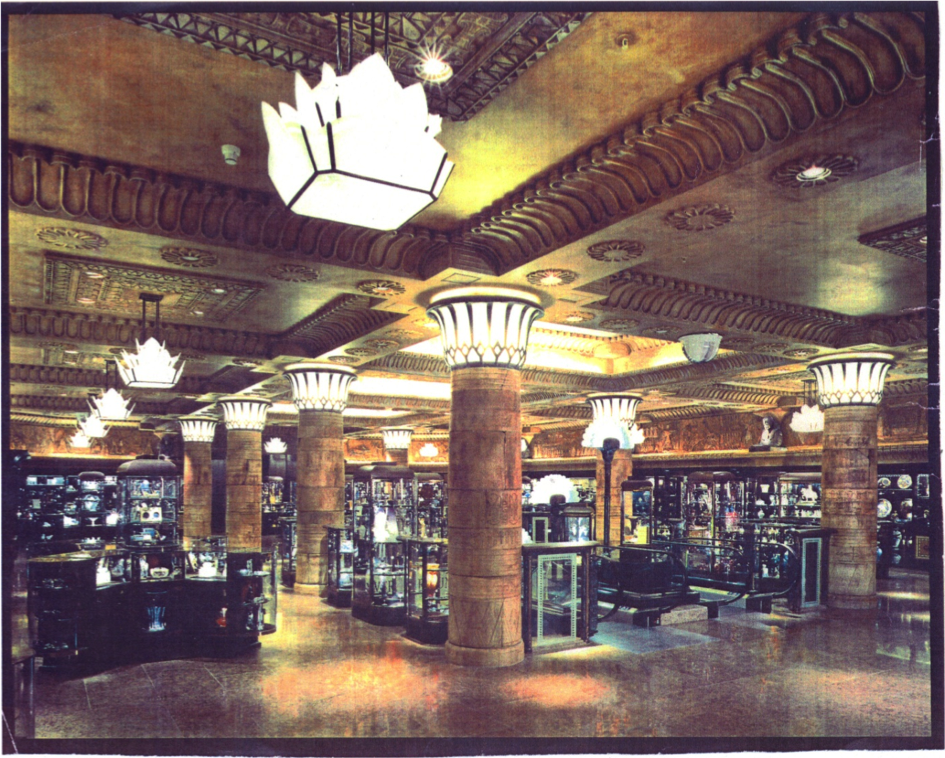

He worked internationally, from a zoo in Qatar that was visited by the Queen, to the Egyptian hall and Staircase at Harrods in London – a truly remarkable piece of design when Bill was 75!

The Egyptian Hall at Harrods, also a listed building, which was created for the visit of the former president of Egypt, Hosni Mubarak. For this and the Egyptian Staircase Bill drew inspiration from the British Museum and he designed lights in the style of ancient Egyptian fans.

In Honolulu he was invited to design and construct a façade in the downtown civic square. He involved local schools and it was all brought to life by Bill’s boundless imagination and technical skill and experimentation.

‘…the life of William George Mitchell has been a richly lived and full affair. …it offers not only an insight into the workings of one of this country’s least known, yet most prolific and gifted of sculptors, but also allows for a timely and welcome opportunity to reassess his astonishing body of work. …this absorbing book… The range of materials, styles, processes and techniques that he developed (and in many cases invented) to enable him to give expression to his vision, combined with a keen eye for pattern and form, resulted in some of the most distinctive works of the period. …this excellent book can only add to the growing clamour for his much deserved and belated recognition’. The Modernist

Self-Portrait: The Eyes Within by William Mitchell is published by Whittles Publishing, priced £25.99.

Catherine Carswell was an author, biographer and journalist of the early 20th century best-known for her controversial biography on Robert Burns. Before her writing career took off, she married Boer War veteran Herbert Jackson after a very quick courtship and their separation led to a landmark divorce case. Ajay Close has written a stunning novel, What We Did in the Dark, based around the events of this first marriage, and in this extract, we witness one of their first outings together.

Extract taken from What We Did in the Dark

By Ajay Close

Published by Sandstone Press

A school of arms!

You are amused by my surprise. Did I think you would belong to the sort of club that charges its members to sit in button-backed armchairs and read the newspapers? You had your fill of that in Liverpool. A nest of bullies and gossips, just like school. After a day at the easel, a physical contest, man to man, is just the thing for your aching muscles. They are all vigorous, good-natured fellows here. Anyone with a nasty streak would soon be drummed out.

The ladies’ sitting room overlooks the fencing hall. A smell of powdered rosin and sweat rises from the men below. Some are stretching, awaiting their turn with the foils. Others watch from benches. The wooden floor is marked with broad red stripes, allowing four separate contests to proceed simultaneously. The swordsmen dance up and down their allotted ground, left arms raised in a courtly flourish. Then, all at once, an interval of effortful grunting, the deft flurry of foils, and the hit, after which they separate. I would like to select a favourite and silently cheer him on, but how to choose when all look so alike in their white suits and padded breastplates, faceless behind their masks. It is a little like dreaming, watching so many ghostly antagonists fighting without motive or passion or the possibility of blood.

And yet my eye finds one of these grunting phantoms more sympathetic than the rest. I make him my champion. My ear picks out his stertorous breath, the thump of his soft-soled boots on the wooden floor. He and his opponent seem evenly matched, moving forward and back, neither gaining much ground. Attack, feint, lunge, parry, counter-attack, circle parry, disengage. No hits. For a long time it could go either way, but eventually my man’s movements grow sluggish, his foil less exact. Under the arms, his white jacket is wet. I watch the ebbing of his stamina, the effort to draw breath. The other’s eye is a fraction sharper, his hand a split-second faster. My champion knows it, and the prospect of defeat lends his swordplay a new fury. The thrilling pace is almost too quick for my unpractised eye to follow. It cannot last. My man begins to flail and stumble, lunging too violently, exposing himself to the counter-thrust.

A hit.

The men step back, lowering their foils. My champion rests a hand on his heaving chest and pulls off his mask to reveal a violent flush. The victor, too, unmasks. You! In my astonishment I laugh out loud. You look up, catching my eye.

In Glasgow there is an unbridgeable gulf between the burly coalmen shouldering their hundredweight sacks, the draymen hefting casks of ale, and virile intellects like Walter, pale from long hours indoors, eyes red-rimmed from straining to read fine print by lamplight. I never dreamed of meeting a man with an artist’s soul and the ruthless physicality of a soldier.

The restaurant is hardly bigger than a shop. The dim interior with its densely patterned wallpaper encourages conversation in lowered tones. To me the place feels delectably illicit. We take a table in the corner furthest from the window. Three prosperous-looking men sit over snifters of brandy. A pair of elderly widows despatch plates of breaded plaice. In the other shadowy corner, an exquisitely pretty woman is whispering with an older man too ugly to be her father. When you turn to see what I am looking at, your face shows such disapproval that I am moved to defend her. We can’t know she is a paid companion. Yes, he is old and fat and balding, but then so is the king and, if rumour is to be believed, he has broken his share of hearts.

‘Because he was Prince of Wales.’

‘Partly,’ I concede. ‘But don’t you think grossness can be attractive – at least, when it’s in tension with other, finer qualities?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘Perhaps women are more susceptible to it.’

‘And perhaps you’re in a contrary mood, and you’d argue with me whatever I said.’

‘I would not!’

Your heavy-lidded eyes fix on mine. ‘Then those maidenly blushes hide a streak of depravity.’

There is a delicious edge to this teasing. I think your foil is safely blunted, but how can I be sure?

‘Never lie to me, Catherine. I shall always know.’

‘Is there no end to your talents – portraiture, swordsmanship and mind-reading too?’

You smile. ‘You have an unusually candid face. It shows every thought, like a pool rippled by the wind, never quite at rest.’

I am too pleased to know what to say.

‘Has no one ever told you?’

I shake my head.

‘Your eyes darken, or lighten. Your colour changes, flushing or paling—’ your hand stops just short of my cheek ‘—here. And here.’

You find me beautiful. It is as if I have been teetering across a rickety bridge, refusing to look down, my whole life. And now that you have handed me across to firm ground, I know I was never in danger of falling.

‘When a woman looks in the glass,’ I say, ‘that is, when I look, I refuse the face I find in that first instant, composing my features, almost without thinking, to achieve a more alluring reflection. I’ve had so many years of practice, it’s the work of a moment.’

‘So you’ve no idea how you appear to others?’

‘How can I know?’

‘I could paint you.’

And of course this is what I hoped you would say.

You ask what I did before studying at Glasgow University. I tell you about the Frankfurt Conservatory, how I went there in love with my own talents and, within a fortnight, knew myself quite ordinary. Even as I persevered, making the most of the opportunity I had been given, a spark in me had been snuffed out. Walter blew it into life again. He gave me an ear for the music of words. Not just Shakespeare and Donne, but the cadences of everyday conversation, the scope for playfulness and virtuosity over the breakfast table. His praise, quite unlooked for, resurrected my old brilliant self. Two blissful years as his student. If I had forgone Frankfurt, I might have had four and taken my degree, but the end would have come just the same. Brilliance might be charming in a girl, but it is no use to a grown woman, unless I marry well, like Mary, and can afford to host a salon. All my education has only rendered me less suited to living with a widowed mother who is good-hearted, but exasperatingly slow: a muddle-brained, trusting innocent. How can I leave her defenceless in the world? But how can I bear it, if I do not?

You listen without judging me, having your own forbidden thoughts about the futility of teaching. You have given up your position in Liverpool and plan to earn your living as a civilian engineer.

‘But you’ll still paint?’

You look down at the tablecloth. ‘It’s no great loss to the world.’

‘Even if that were true, it’d be a loss to you.’

It is so long before you reply, I wonder if you have taken offence.

‘I’m not sure it’s healthy to define oneself by a talent no one else believes in.’

‘I believe in it.’

The feeling in your eyes makes me think of a dog on a chain. Leaping up, to be yanked back down again.

‘Jackson! I thought it was you.’

A ruddy-faced man looms over our table. One of the brandy drinkers. There is a smear of custard in his half-handlebar moustache.

Your glance flickers, as if calling on all your reserves of patience. ‘Scotty,’ you say flatly.

‘What a turn-up, bumping into you down here.’

Scotty turns to me. You do not introduce us.

‘Just the other day, Gordon Duff was saying “I wonder what’s become of Jackson.” The club’s all at sixes and sevens, what with moving down the hill and all. No end of new blood about the place. That chap Muirhead they got in to fill your shoes seems very popular. Amusing fellow but solid, y’know. Not like whatsisname. Had to count the spoons every time he got up from the table. Dowdall says he’s a genius, but everything he painted looked sloppy to me. He’d do better swearing off the gin and getting fewer parlour maids in the family way. Still, rather them than Mrs D, if you catch my drift. What was his name… Julius, was it? Something of that sort. We miss those boxing classes of yours, y’know. Are you still fighting? In the ring, I mean.’ He prods your arm. ‘In the ring, eh, what? Never mind, old chap, just a joke. So, how are you making a living these days? I suppose studio work don’t put much jam on the table.’

He reminds me of a clockwork mouse I had as a child. It kept going, even when it met the skirting board, until the mechanism ran down.

One of his companions pays the bill. Scotty glances over his shoulder.

‘Well, I should really get back to, ah… Things to do, y’know. I’ll give the chaps your best.’

‘I’d rather you didn’t,’ you reply in the same flattened voice as before.

‘Oh, ah, as you wish.’ He sneaks another look at me. I make sure not to meet his eye. ‘Good luck, old chap.’ With a nod in my direction, he moves off to re-join his friends, who rise from the table and follow him out to the street.

‘I’m sorry about that,’ you say.

‘Who is he?’

Raising a hand, you get up to peer through the window. Satisfied, you sit down again. ‘He had the room across from mine at the University Club in Liverpool. For years I counted him as a friend.’

‘But not now, I gather.’

‘Many false friends have shown their true faces over the past two years.’

‘He seemed harmless enough.’

How cool you are suddenly. I curse this habit of commenting on things I do not understand.

The waiter passes our table bearing plates of empress pudding for the widows.

‘What’s the matter, Catherine?’

‘I hope you never despise me.’

You search my face. A blush rises up my throat and across my cheeks. I feel as if my skin were glass, as if you read my thoughts almost before I think them. Your gaze locks on mine, transmitting a beam of smoky light.

‘I hope so too,’ you say.

What We Did in the Dark by Ajay Close is published by Sandstone Press, priced £8.99.

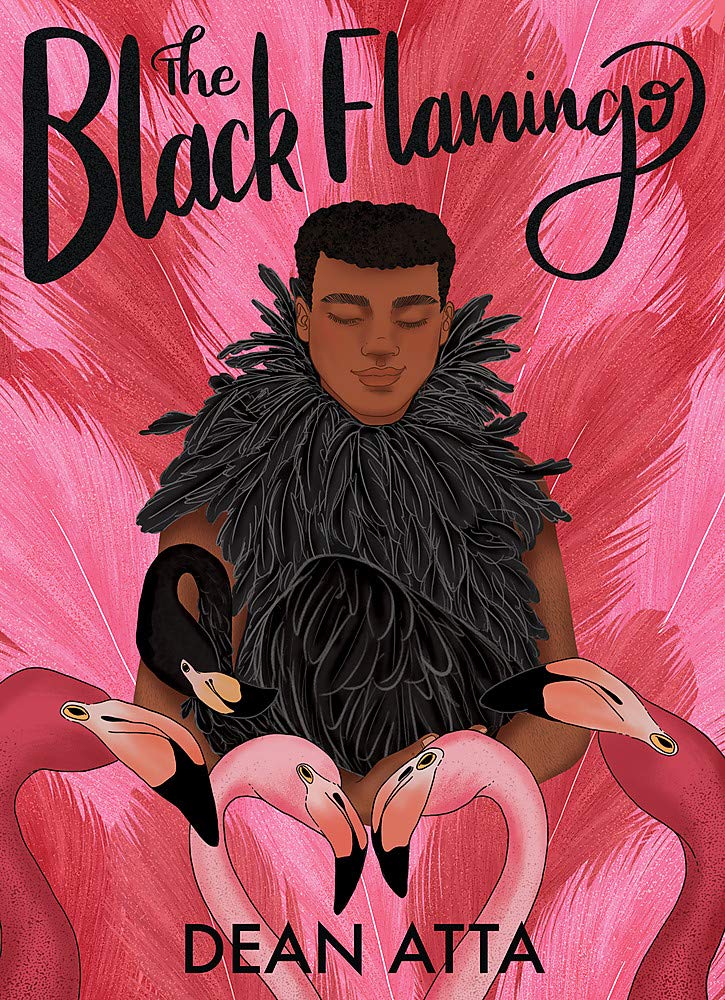

Dean Atta is an exciting poet and performer, based in Glasgow, named one of the most influential LGBT people in the UK by the Independent on Sunday. The Black Flamingo – longlisted for the Jhalak Prize and the Carnegie Medal, and winner of the Stonewall Book Award – is a young adult novel in verse that follows a mixed-race gay teenager as he heads off to university and discovers his place in the world as a drag performer. We’re thrilled to offer this audio taster of the novel, just released in paperback.

The Black Flamingo

By Dean Atta

Published by Hodder Children’s Books

The Black Flamingo by Dean Atta is published by Hodder Children’s Books, priced £7.99

The award-winning and Granta Best Young British Novelist (2013) Evie Wyld has set her latest novel, The Bass Rock, in East Lothian, in the shadow of the coastal landmark. Kristian Kerr finds it an ambitious, thought-provoking novel with memorable, resonant characters.

The Bass Rock

By Evie Wyld

Published by Jonathan Cape

The Bass Rock, a guano-frosted carbuncle-landmark off Scotland’s East Coast, plays the same part in Evie Wyld’s new, third novel as the titular lighthouse in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. It lies offshore, a background presence, a place that looms occasionally into characters’ consciousness; busy with the smaller dramas of human affairs, however, no one journeys there. It stands sentinel in the sea, a gargantuan witness to the lives playing out on the windswept East Lothian littoral. Onto this landscape of beach, sea, sky, and wood, Wyld weaves a fabric of stories, layering century-spanning timeframes over the geography and pulling connecting threads into the light. Three women’s lives unfold here on the edge of the land, and this novel captures how elemental forces act both on them and within them.

There is a distinctly Woolfian vibe to The Bass Rock. While this is no summer holiday, the novel’s two leading women find themselves mistresses of the ‘big house’, charged with domestic responsibility for all under its roof. They also knock around in it – between the public and private zones of bedroom, kitchen, attic or study – questioning themselves and their authority, and Wyld’s depiction of the difficulty of balancing responsibility for others with personal anxiety is spot on. Her characters’ internal monologues are mordant with self-criticism and a wry, low-key observation of others’ peccadillos.

In the present, Viviane has been given the half-job of minding the house while it is on the market. She is mourning her father’s death and recovering from a breakdown, and the gig has come her way as much to help her out as it is to keep the house lived in. Her antagonist in this is the sprightly Deborah, an estate agent who prescribes a litany of ersatz remedies to present the house to appeal to the modern buyer. Damp is the enemy; precious-but-hideous family heirlooms should be hidden from sight, as should the traces of genteel alcoholism; patchy mobile signal may, in the end, prove the house’s Achilles heel. Viviane rebels against this kind of sterility by inviting local free spirit and self-identifying witch Maggie to avail herself of the house’s facilities as and when she needs to. Deborah would certainly not approve. Significantly, Viviane also repopulates the house with memories of her childhood visits. These are often incomplete, or foreclosed by grief for her father – she cannot quite, for example, bring herself to sleep in his childhood bed under the eaves – but they are the fragile threads that connect the two main narratives of the novel.

Ruth arrives in the house in the 1950s, newly married to a widower and consequently stepmother to Michael and Christopher, his pre-adolescent sons. Grief is here too, for a wife and mother who died of a respiratory illness and a brother killed in WW2, and Ruth is wading through it, under the burden of expectation that she make the best of things for both the boys and her husband Peter. One of the joys of Wyld’s depiction of both Ruth and Vivian is how she depicts them experiencing alienation and connection as equally powerful modes. Reading this novel, you feel that you know these characters minds intimately, but that you also cannot know them at all.

Ruth’s support comes from Betty, the housekeeper whose bland, gelatinous food serves initially as a rallying joke for Peter and Ruth. Betty guides Ruth through the rhythms of life in the house and the community and they find an accommodation that lasts for the rest of their lives. In both narratives the house becomes a shelter for women of different backgrounds whose lives have not conformed to a traditional narrative of domestic happiness, though the novel insistently questions whether that narrative exists at all. Individual stories are gnarled and family trees don’t grow straight.

The interlocking narratives of Viviane and Ruth, whom she knows grandly and distantly as ‘Mrs Hamilton’, would suffice to make a compelling family saga, told in a spare, modernist mode. Wyld goes a step further, however, perhaps inspired by the timeless presence of the Bass, perhaps by the story of the late-sixteenth-century North Berwick witch trials, and weaves in the story of Sarah, persecuted as a witch and on the run in the woods with a family of religious dissenters.

Here is a story of survival and violence, of hounding and pursuit, of living outside the margins. It connects powerfully with Maggie’s story, with earthy and unfettered sexuality at once enticing and empowered, feared or disapproved of. This thread of the story places a premium on instinct: sensing wolves, foxes and existential dread are survival tools here, when closer to the present they are dismissed as hysteria, the preserve of women and children. In its depiction of domestic horrors and succours through the ages, this novel quietly advocates for the prizing of instinct and intuition amidst the inescapable violence of human interactions. Bluff fresh-air, cold-water school masculinity certainly does not fare well, though this beautifully constructed novel offers no easy resolutions.

The Bass Rock by Evie Wyld is published by Jonathan Cape, priced £16.99.

Though starting out her writing career as a food writer, Sue Lawrence has been gathering many fans over the last few years with her historical fiction. Her latest novel, The Unreliable Death of Lady Grange, sees her tackle one of Scotland’s most intriguing true crime stories – the faked death, kidnapping, and incarceration of Rachel Chiesley, wife of James Erskine, Lord Grange, a suspected Jacobite sympathiser. Here we publish a scene from the novel’s prologue, where Lady Grange’s daughter, Mary, is unconvinced of her father’s official story.

Extract taken from The Unreliable Death of Lady Grange

By Sue Lawrence

Published by Saraband

1732

‘Mother is not in that coffin, you know.’

‘Don’t be foolish, Mary; it’s your mother’s funeral. Of course she’s in there. And a rather fine polished oak your father chose for the cask, too, I must say.’

‘Aunt Jean, Mama is not dead. She can’t be. She wasn’t ill; she never was.’

‘Keep your voice down, child.’

‘I am not a child,’ Mary hissed. ‘I am…’

There was a loud bang as the door flew open and four pallbearers entered the room, heading for the coffin. They took up their places at each corner and turned towards the minister, who approached and rested a bony hand upon the wood, rubbing his long fingers up and down it, as if enhancing the sheen. He raised his head and surveyed the room.

There was Lord Grange, whose wife’s burial was about to take place. Beside him stood Aunt Jean’s husband, Lord Paterson, and the five surviving Grange children, all dressed in black, arrayed in descending order of age. Mary, the eldest daughter, stood beside her father’s sister.

‘I repeat, Aunt Jean, she was not ill. I can’t remember a single time when she was ailing; she was always as strong as an ox. Besides, how is it possible that her waiting woman has also disappeared, vanished into the night?’

‘She never was a reliable servant.’

‘Fannie and Aunt Margaret agree with me; Mother is not dead.’

‘Fannie is but a child. And really, Mary, as if your mother’s sister would say otherwise,’ Lady Paterson harrumphed.

‘Hush now, the minister is about to speak.’

The Reverend Elibank began, in his reedy, high-pitched voice, speaking to the family and the assembled great and good of Edinburgh, including several from the bench. There must have been some thirty people packed into Aunt Jean’s parlour and they all turned to hear something of the remarkable life of Rachel, Lady Grange, who had sadly passed away so unexpectedly three days earlier. In a solemn tone, he told them how she was mourned by her beloved husband and her seven children, two of them from beyond the grave.

Lord Grange’s face remained still, unfathomable. Yet as his eldest daughter peered under her bonnet at him, she thought she saw a flicker of something, a twitching around the lips on the otherwise impassive features.

The minister droned on about Rachel Grange’s journey to heaven, guided by the angels and archangels on her ascent. His voice became louder as he described her arrival at the crystal clear river of the water of life and how she then came before the throne of God. The crescendo continued as he intoned the lines from scriptures: ‘I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end.’

Mary nudged her sister, who had put her hands over her ears as the minister’s voice peaked. He was exclaiming to the mourners – but particularly to the women and children, who of course would not be attending the burial at Greyfriars Kirk – ‘I am the first and the last’. There was a sudden hush in the room as, finally, he closed his eyes as though in silent prayer to end his homily. Slowly, as if for dramatic effect, he opened his eyes and bent over in a deep bow towards Lord Grange. He then nodded to the pall-bearers, who raised the coffin upon their shoulders, as he squeezed his willowy body through the throng of people, heading for the door.

Everyone watched the coffin shudder a little as it settled on the four pairs of shoulders; it tilted over at the head end, where the shortest bearer raised one shoulder high to try to regain his balance. He turned and nodded to the assembled men and they trudged towards the door.

Lord Grange lifted the hat that he had been holding at his side and leant over to his sister. ‘We shall return within the hour, Jean. Be sure the table is laden – and be especially generous with the wine and brandy.’

‘We’ve discussed this, James. Cook has excelled herself. As well as the roast meats, there are plum cakes and sweetmeats in abundance. The stoups are already filled to the brim with claret, brandy and ale; there’s also tobacco aplenty. Now, be off and don’t upset yourself further, dear brother.’

The man kissed his sister’s cheek, patted his youngest children on their heads then glanced over at his friend Simon, whose ruddy cheeks and bulbous nose were already flushed with claret.

Mary stared at her father as the two men exchanged glances, hoping for some token of sympathy from the bereaved man to her, his eldest daughter; but she saw only the glimmer of a smile around his lips as he acknowledged his fellow mourners then turned away, striding towards the door, where he placed his hat firmly on his head as he prepared to face the January chill.

The Unreliable Death of Lady Grange by Sue Lawrence is published by Saraband, priced £8.99.

Alan Parks has quietly become a writer to watch in Scotland’s crime writing community, building his name with each of his visceral, pageturning thrillers. He has just released his 3rd novel starring his troubled detective, Harry McCoy, and BooksfromScotland caught up with him to find out more about his series.

Bobby March Will Live Forever

By Alan Parks

Published by Canongate Books

With your new book, Bobby March Will Live Forever, you’re now on your 3rd Harry McCoy thriller. Tell us about the novel, and how it fits in with the series you’re building?

The book starts with the overdose of Bobby March, a Glaswegian guitarist back in the city for a concert. What initially seems like an ordinary overdose becomes more complex as McCoy investigates. He is also dealing with the promotion of Bernie Raeburn, a rival who is determined to make his life misery. He keeps him off the big case of the moment, the disappearance of a twelve year old girl. Murray, his ex boss asks him to find his missing niece and to keep it off the books. McCoy soon discovers why…

The book takes all the familiar characters – McCoy, Wattie, Murray and Cooper and falls what has happened them in the six months or so since the last book. Big changes for everyone.

A troubled detective and the Glasgow underworld of the 1970s. What made you decide to take on such sacred cows in the Tartan Noir firmament in your own writing? You must be very brave!

Not really, just stupid! I like all the cliches of Scottish crime writing. The mean streets, the sidekick, the razor wielding thugs, the grumpy Boss. I wanted to write books that had them all and try and look at them in a slightly different way.

The whydunit takes precedence in your books rather than the whodunit. Tell us about the inspiration behind the characters of McCoy and Cooper.

The idea was to have two characters on the different sides of the law who were tied to one another. They met growing up in care and Cooper looked after McCoy so McCoy feels a huge debt to him, keeps being friends with him even though it’s not the best thing for his career. They are very different though. Cooper is like a shark, he moves forward doing what has to be done with no regrets or looking back while McCoy is more of a victim of his past, it still affects him and what he does. The challenge for both of them is to remain friends as both their respective careers move forward.

You’re taking on two genres—historical fiction and crime fiction—how much research goes into creating Harry’s world?

Quite a lot! There is the library stuff – what was going on at the time, what pubs were open then, what was happening in the city at the time, what day to day life was like. Yo can do some of that at The Mitchell Library. I’ve spent a lot of time on The Glasgow Floor these past couple of years.

Then there is the other stuff, the more mood research. That means watching films from the time, old TV programmes and listening to music from the era. That helps you just get a general idea about what was in the air at the time, what people were thinking and talking about.

There’s some interesting rewriting of some rock n’ roll history in Bobby March. Having worked in the music business yourself, did you always want to bring your knowledge there into the series?

No! Everyone kept asking me why there was no music stuff in the books but I wanted to avoid it until the characters and the atmosphere in the books was established. Book three seemed about the right time. Bobby March is a kind of Zelig character. On the edges of a lot of big events and around big stars but never quite the star….

The titles of your books so far suggest at least twelve books in the series. Do you have an idea of how the series will pan out?

I could lie and say yes….

Can you give us any hints on what April might bring?

Just starting it now. A few clues – The Holy Loch. Peterhead. Mau Mau. Brothers. A house by the sea…..

What other books are you looking forward to reading in 2020?

I read The Young Team by Graeme Armstrong which was great. Reading Long Bright River by Liz Moore, also really good. Looking forward to Liam McIlvanney’s new one. Death in her Hands by Otessa Moshfegh. The F*uck it List by John Niven and the new Phil Klay, Missionaries.

Bobby March Will Live Forever by Alan Parks is published by Canongate Books, priced £14.99.

Returning to brilliant historical fiction, BooksfromScotland were delighted to hear that Lesley Glaister was releasing a new novel. Now, that it out in the wild, we hope that Blasted Things finds its way on many a bookshelf. In this extract, Clementine has just given birth to her first child, but she can’t forget her first love, and her life’s potential during her time as a nurse in the First World War trenches.

Extract taken from Blasted Things

By Lesley Glaister

Published by Sandstone Press

1920

The infant’s eyes were as black as if night were trapped behind his lids, and when he opened them she feared she’d be consumed. She focused instead on Dennis, his face infused with love, voice thickened by it, as he gazed at her and the baby in her arms.

‘He’s perfect, darling. Sterling job. Well done.’ He kissed her brow, and her lips lifted at the corners as if on strings. Together they regarded the tiny pink face, dark wispy hair, smooth lids shut tight now, pale blinds against the night.

An innocent newborn.

But he was the wrong baby.

She wanted to ask them to take him away and give her the right one. But she could not say it; of course she could not. Instead she pressed a kiss against the queer soft pulsing of his fontanelle.

The wrong baby.

After the Clearing Station had been hit, she, Gwen and Sister Fitch had been transported to a hospital in Boulogne to recover. In the bathroom there, a few days later, Powell’s child, small enough to curl into a walnut shell, had slid away from her onto the white floor. On her knees, she’d watched blood ooze into a gaudy chequered grid between the tiles until Gwen had found her and come to her aid, asking no questions, withholding all judgement, and afterwards, recognising that Clem was fit for nothing, had her packed off home.

And home meant Dennis, innocent of everything, his ring back on her finger, flashing sapphires and diamonds, once his mother’s, once his grandmother’s. Too numb to object, she’d gone along with it, allowed the wedding, allowed this other child to come.

This black-haired boy.

The wrong baby.

From the window of her room in the convalescent home, you could see the empty branches of trees, the colourless sky and the mudbrown flow of the river. Barges sailed across the window during the day. From her pillow she watched the sails, and when the nurses opened the windows to air the room, she could hear clanking and the mew of gulls, and the smell of the river, like a wet animal, padded in to shake its fur.

Dennis brought roses – extortionate in January – stiff, red, scentless. He brought chocolates, hothouse grapes with tight green shiny skins. He was proud, exuberant, normal. He’d slipped paternal love on as easily as an overcoat, and she envied him.

Old Dr Everett had tears in his eyes as he held the baby, his full grey beard spread bib-like over his chest. ‘Violet should be here to see him,’ he murmured. ‘Your image, Dennis, your dead spitting image.’

Harri, red-faced and slapdash, paint in her hair and a twin on each arm, had come and enthused, bestowed wet kisses and a strange green matinee jacket she’d crocheted out of twine.

Once visiting hour was over and a nurse had removed the infant from her arms and drawn the curtains for her afternoon nap, Clem lay startlingly awake, trying not to think but thinking, thinking.

This was a mistake, like having got on the wrong bus and arrived at the wrong destination, only, of course, a million times worse.

She should be in Canada with Powell and the little girl. When she shut her eyes she was there, on a sunlit prairie, watching the child, Aida – marvellous name – toddling, pale-haired, silver eyes so like her father’s. Powell was crouching and holding his hands out to her as she took those first wobbly steps, such a glow of pride on his face!

But no, here she was in a convalescent home on a dank English January afternoon, the wrong baby sleeping in his crib, the wrong man feeling proud. She should be glad, she should be grateful, yes, she was. How lucky to have landed, as Harri put it, on her feet.

After all, her life was perfect now, enviable: married to robust Dennis, not a scar on him – the war seemed barely even to have dented his optimism. He hadn’t volunteered – medicine a reserved occupation, of course – and he had done wonders here, everyone said so, and it was true. He’d supervised the conversion of Middlesham Hall into a military hospital and worked there, while still keeping up the family practice. He was marvellous. She was lucky. And now a healthy son. Lucky. Lucky.

A seagull glided past in a ray of orange, its shadow on the wall. She turned over in bed, feeling the empty fold of belly flesh where the baby had been, and she thought of Powell about whom no one – except Gwen – even knew. What would have been the point of telling them? She’d wondered if, being a doctor, Dennis might have been able to tell what her body had been through: but no.

On the prairie the wind blows and the palominos toss their manes, kick up their heels.

*

Clem fed the baby when he was presented, gazing down at his stern working face. The chin moved up and down, the cheeks pulsed as he suckled, pulling threads of milk that curled her toes. His eyebrows were rows of invisible stitching, eyelids bruisy, irises gradually resolving from black to smoky damson to chestnut, a little clearer every day. She held her palm beneath his marching feet.

But most of the time she kept her eyes on the book she made a pretence of reading.

‘Mother!’ She jumped. ‘Mother! Whatever do you think you’re doing?’

This nurse was younger than she; only the uniform lent the authority for such impertinence. ‘We should concentrate on baby as we feed him!’ She plucked the book from Clem’s hand, slapping it shut, losing her place. That scarcely mattered, the page had only been a place to rest her eyes. The nurse’s face was pertly cross, complexion smooth under her starched cap. She would have been a child in the war – the few years that separated her from Clem a filthy great gulf of understanding.

‘First baby too!’ she went on, clucking her tongue. ‘Whatever next!’ She lifted the infant from Clem’s arms and held him against her shoulder. ‘Now then, little chap, is your mummy a naughty girl? We’ll have to give her what for!’

Clem’s face twisted in a kind of smile as anger rose in her and fell again like a wave unbroken. This girl did not know. Why should she? To her generation the war was nothing but a bore. Old hat. And that’s the world Clem wanted for her son after all. His greatest challenges would be in sport, examinations, commerce, romance. So she forgave the nurse, but somehow Dennis she could not forgive.

Stop it, stop it, that’s not fair.

Not forgive him for what?

Not being Powell.

Not divining what she’d been through.

Trampling so cheerfully on her grief.

Ramming his great red thing in where it wasn’t wanted.

Not having been to the Front.

Not that he was a coward – was not, was not, was not, was not, was not. He had done wonders.

But still . . . but still.

Blasted Things by Lesley Glaister is published by Sandstone Press, priced £14.99

Time now, for another debutante, another fresh, new voice in Scottish fiction. Shola Von Reinhold’s first novel, LOTE, promises to be packed full of provocative, exciting writing and ideas. We caught up with them to chat about their journey in writing so far.

LOTE

By Shola Von Reinhold

Published by Jacaranda Books

Congratulatons on the publication of your debut novel, LOTE. What can we expect within its pages?

Thank you! LOTE charts its narrator Mathilda’s rediscovery of the Afro-Scottish interwar modernist poet, Hermia Druitt. It is partly about the blanching of pre-Windrush Black artists and writers in Britain and Europe, and is partly about a contemporary pursuit of beauty, excess and the politics therein from a queer Black perspective. It also features hotels scams, champagne theft, puritanical art saboteurs and a modernist angel cult whose members believe the mythological lotus-eaters were a proto-luxury-communist society based in West Africa.

Can you remember when you realised you wanted to write?

No, but I remember posting a draft of a novel to Bloomsbury and some other publishers when I was eleven thinking, ‘What a shock they’re going to be in for when they discover I’m eleven!’ What a grim and mercenary approach to writing to have as a child. I suppose my generation were bombarded with rags to riches stories about books and writers and I scented a material escape alongside an immaterial one.

You also studied Fine Art in Central Saint Martins. How do the visual arts inspire your writings? How do you approach each discipline?

I don’t paint anymore but arguably a lot has crossed over – textually I’m just as interested in excess, stylisation and ornament. Either depicting these things or depicting with/through these things. My writing also often features fictional paintings, something I only noticed recently.

Your publisher, Jacaranda, are publishing LOTE as part of their Twentyin2020 initiative. Tell us more about that.

Last year it was announced that Jacaranda Books would be publishing twenty Black British writers in 2020. Jacaranda is a Black-founded, Black-owned publisher run by a small team of Black and Brown women. They have always focused on centring marginal writing. This initiative specifically focuses on Black British writing which I think is important. BAME initiatives can often be all AME and no B. There’s been a tendency in publishing when celebrating Black writing to bring in writers from outside of Britain which goes hand in hand with a denial that Black British writers even exist. In 2016, out of 165,000 new titles only 100 were by writers of colour (with 33 being self-published.) That same year only one Black man published a debut novel. 2019 figures showed that, in spite of a lot of talk, not enough had changed and all the worthwhile material improvement that was happening was coming largely from Black women like Sharmaine Lovegrove, Bibi Bakare-Yusuf, and my own publisher Valerie Brandes. Jacaranda’s initiative rather than spending lots of time and money on panels and events that manifest very few actual publications is using their resources to simply just publish 20 Black British writers in a year. A number which is rare for a mainstream house let alone a small press.

Which writers do you look to for inspiration?

LOTE is the by-product of various books. Writing by the likes of Gemma Romaine and Caroline Bressey is always inspiring, particularly the meticulous research they conducted at the Slade and elsewhere which uncovered various figures who expand our knowledge regarding the presence of Black and Asian artists and students in Britain during the interwar period. I’m currently reading Romaine’s vital biography of Patrick Nelson. He’s not mentioned directly in LOTE but like the novel’s Hermia Druitt, Nelson was a Black queer person living in Britain between the wars and like Hermia he encountered the Bloomsbury Group and was an artists’ model.

I came across another sparking point for Hermia Druitt in Philip Hoare’s Serious Pleasures in which a certain anecdote is given. The books’ subject, the queer aesthete Stephen Tennant and his friend Rex Whistler were studying at the Slade in the early ’20s and one day burst into the Life Room to present a bouquet of white roses to another student. The woman was mixed race. I began to wonder who she was, if any of her work survives, and what it was like for a Black woman studying at a prestigious institute in London at that time.

Other writers I’ve recently read and found excitement in include Nisha Ramayya, Isabel Waidner. . . Oh, I’m currently two chapters into Irenosen’s Nudibranch and OMG how exciting to encounter such an example of Black experimental fiction in Britain actually being published and receiving recognition. I’m v thrilled for her next book with Dialogue. Irenosen’s debut was published by Jacaranda so it makes me quite delirious to be published within this vein. What else? There’s the Harlem Renaissance writers Richard Bruce Nugent and Jessie Redmon Fauset. There are also Leonora Carrington, Muriel Spark, Hope Mirrlees, Denton Welch, Darryl Pinckney and Andrea Lawlor.

If you have one piece of advice for new writers that you would’ve found useful to know at the start of your writing career, what would it be?