It’s always a delight to take part in the end of year round up podcast with Alistair Braidwood of Scots Whay Hae!, one of the best websites and podcasts celebrating Scottish culture. If you’re still looking for recommendations Christmas gifts, then let us give you a whistle stop tour round the books that caught our eye over the year.

Check out the Scots Whay Hae! website for more excellent Scottish culture.

Rosemary Hector has re-imagined the Nativity story through a series of poems offering different voices and perspectives. If you’re looking to see this story anew, this beautifully-illustrated book is a perfect gift for Advent. We’ve selected here a few of the poems from the collection to kick start your Christmas reflections.

Poems taken from A Quickening

By Rosemary Hector

Published by Muddy Pearl

Matter of Belief

The guide from National Geographic suggested

it could have been a trough, rather than a manger,

where Mary laid her baby, since Bethlehem,

banked by olive and almond trees, is on an aquifer

and was built to defend water. He pontificated that

water and height, the soil and its fertility, defence,

boundaries and access remain political issues.

Trough or manger; a problem? The mystery is

in contested territory, in politically charged times

God became matter, and tiny, contained.

Star of Bethlehem

A conjunction of planets:

a comet; a nova (birth of

a new star), or a miracle

(without explanation)?

Oblivious, the quilters

sense the need for joy

in their choice of colours, know

effort should focus more

on effect than on perfect points;

a burst of visual delight.

They choose this pattern,

cut cloth, stitch and patch

this many-sided star,

and sense its significance,

the ancient story.

Learned men. Interpreters

of skies. The decision

to trust their knowledge,

traverse deserts, hopeful,

follow what they could see,

follow the foretold.

Art

Did he come down to be mocked up

in plaster of Paris, or pale wood

painted with vermilion wounds,

paraded through streets each fiesta?

Did he come down to be a statue

handled by men in white gloves,

gently winched onto a plinth?

Did he come down to model

for Raphael or Leonardo;

on a beatific Mary’s lap?

Yes, he came down, for all our poor

attempts to represent what we sense,

or consider beautiful and in good taste;

he came down and has compassion

on our worst art, and on our best.

Lament

… oh i cry for our country a bank with no money

a shop with nothing to sell a sandpit not safe for play

because of litter and needles and dog shit

oh i weep bitter tears for our country …

Isaiah’s metaphors were for different times; he wrote

of neglected vineyards, deserts, burning straw, as he wept

for Israel, God’s lovely nation. It was the same observation

as today; a failure of justice. Rightness offended.

A prophet’s lament is not personal, but mirrors

things as they are. It speaks to those in power,

nor does it offer an answer, provide a neat narrative

with a rhyming conclusion. The call is to consider, return.

Say ‘sorry’ and attempt to restore all that is broken.

Yet within his descriptions of darkness and woe a small voice

slips in; light. There will be a child. Named ‘God with us’.

With us, in all our metaphors. In all our times.

A Quickening by Rosemary Hector is published by Muddy Pearl, priced £9.99

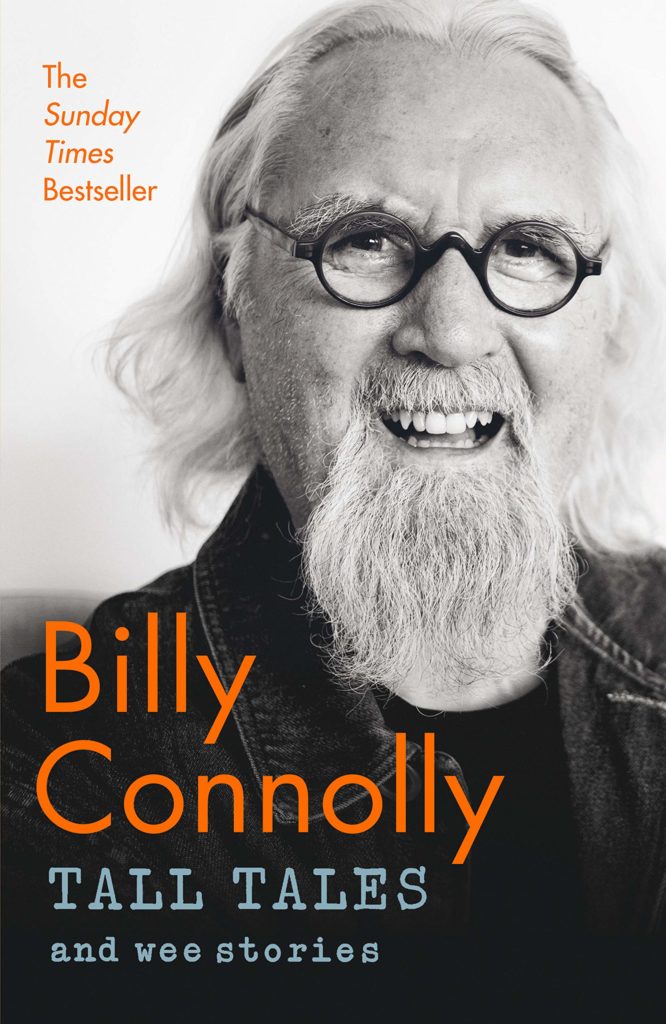

It’s fair to say that Billy Connolly is both National Treasure and absolute legend. His earthy, surreal and utterly hilarious outlook on life has been gracing stages across the world for decades, and can now be found in print in his latest book, Tall Tales and Wee Stories. To celebrate publication, BooksfromScotland was delighted to look back at some of Billy Connolly’s most famous routines. Enjoy!

Tall Tales and Wee Stories: The Best of Billy Connolly

By Billy Connolly

Published by Two Roads

The Crucifixion

Incontinence Pants

The Welly Boot Song

Tall Tales and Wee Stories: The Best of Billy Connolly by Billy Connolly is published by Two Roads, priced £20.00

When Stephen Rutt moved to Dumfries-shire, noting the daily lives of the birds in the area connected him to his new home. Wintering: A Season with Geese is his memoir of those first winter months, and we’re delighted to present this extract here.

Extract taken from Wintering: A Season with Geese

By Stephen Rutt

Published by Elliott & Thompson

I am falling more deeply for geese on a daily basis. Although I am told the winter won’t always be like this – they are wild geese after all, predictably unpredictable – the regular skeins flying over are captivating me. Sinking deep inside me. It is new for me. In a new place they are making me feel, tentatively, at home. Connected to the world, while it just happens around me, daily and unadorned. It is not a famous spectacle, these passing skeins of geese, not the top billing on wildlife TV. These geese just quietly go about their daily movements, as I go about mine. I am one insignificant human to them but they are reminding me that I am a part of the world that stretches as far away as Iceland, part of the running rhythm of winter.

*

These pink-footed geese know Dumfries better than we do. The skeins we see scoring the sky are following regular routes. Well-travelled sky paths. Geese can be long-lived, if they avoid foxes, polar bears, powerlines and men with guns: the average life expectancy is eight years, but the oldest recorded bird was thirty-eight when it died. The Solway has seen pink-feet live through to their twenties. These are just the ringed birds that we know about, that have been found again. In the thousand-strong flocks there could be some that are older. I wonder at the generations of geese contained in each skein.

*

A morning, a week later. The first skein comes, shaped like the nib of a fountain pen, drawing a northbound line through the sky. I am walking northeast through the town, to the station, on an early golden morning. The third skein skips across, between the roofs of the shops, just off the high street. The fifth veers off eastward, into the sun. The sixth is the vanguard of the two-coach rattling train to Glasgow, ploughing its slow way through the hills to the city. I look up the word ‘skein’ on slow mobile internet from the train. It’s from the old, obscure French word ‘escaigne’, meaning an amount of yarn. The word makes a sort of sense. Although it is the only use of the word ‘skein’ that does not have a textile meaning, I like the way it suggests threads. Threads of geese in the sky, sometimes unravelling, sometimes like a ball of string, trailing a loose end. The skeins we see are stringy strands of the geese. It is only roughly, only occasionally, the precise V-shape of the classic imagined geese skein. Each flock is social. It seems mildly ironic that we should move to a place where I know nobody, and for the birds to be obviously together, benefiting each other. These skeins are social forms of flying. Each goose reduces drag for the one behind it. Each goose helps another.

It is possible to think these skeins ancient, that they have been scoring the sky since time beyond memory. It’s not true. British pink-footed geese come almost entirely from Iceland and Greenland. The rest of Europe’s come from Svalbard, the archipelago halfway between Norway and the North Pole. The Icelandic population increased spectacularly during the twentieth century. I start reading. The Birds of Dumfriesshire, compiled in 1910 by Hugh S. Gladstone, suggests that the bean goose was more common but was being displaced by the pink-footed goose.2 But all grey goose species look similar to some degree and even now, with modern knowledge and modern optics, identification is not easy. Early accounts are mired in confusion and misidentification. What is clear is that over the twentieth century the pink-footed goose became exceptionally common on the Solway Firth, where once it had been either irregular or unknown. The bean goose is now so rare in Dumfries and Galloway that if you see one you have to write a description of it for a panel of four men to adjudicate on whether you are correct.

I was dimly aware that pink-footed geese were supposed to be here in Dumfries, in the way that one is dimly aware of gravity or local politics: I know of the existence of these things and vaguely how they work and affect me, but that is it. Although I can’t imagine a time when I become obsessed with the machinations of councils or the essentials of physics, as necessary as they may be. I was not anticipating how frequently my thoughts would return to the geese, how my eye would be scanning the horizon for the smudge that betrays a skein on the horizon. I was not anticipating how much I would become obsessed with the geese. I was not aware how much they were becoming part of my life.

This is not unique to me.

Wintering: A Season with Geese by Stephen Rutt is published by Elliott & Thompson, priced £12.99

David Ouimet’s I Go Quiet is beautiful, special book celebrating the wonder of books and the imagination. It’s an ideal gift for those you know who prefer to be found in a quiet corner rather than in the thick of the Christmas crowds. We hope this taster of some of the stunning illustrations will get you rushing to the bookshops!

Illustrations taken from I Go Quiet

By David Ouimet

Published by Canongate

I Go Quiet by David Ouimet is published by Canongate, priced £12.99

The end of the year is often a time of reflection, particularly on those who are no longer with us. David Robinson is moved by the bravery and honesty of Kenneth Roy’s memoir on his terminal illness, In Case of Any News.

In Case of Any News

By Kenneth Roy

Published by ICS Books

Try as I might, there is no way in which I can give this month’s column a seasonally jolly topspin. It’s not about Christmas, carols, cracker jokes, stupid sweaters, office parties, balloons or stuffed turkeys. It’s about saying goodbye to all of that, about the empty chair at the feast. It’s about dying.

Most of us have read books by people who know they are dying and want to put into words what their life meant, to describe their experience of love and friendship before it all goes away. I’ve ghost-written such a book myself, on behalf of a man dying of a brain tumour, and in terms of how much it meant to its subject, it is probably the best thing I have written. But in the vast literature of death, I have never come across anything quite as moving or brave as the late Kenneth Roy’s In Case of Any News.

I didn’t, I hasten to add, know him: I never met him, saw him on television, or heard him speak. I haven’t read any of his other books, heard of the charities he founded, or written for Scottish Review, the magazine he founded and edited, in either its printed quarterly (since 1995) or (since 2008) online weekly iterations. My admiration of his book isn’t tainted by friendship or professional courtesy: in short, it’s not personal.

I had, though, read his journalism for years. From it, I had constructed a mental picture of him: a bit crabbit, perhaps, not the sort to throw himself into the mad social whirl but commenting on it from a laconic distance. A cynic, possibly; definitely not a joiner-in or a booming extrovert. One thing for sure: his byline was a byword for clarity of thought and expression, usually with a dollop of wit on the side – ‘writing worth reading’, in the words of the Scotsman advert from the days when he was writing for it or Scotland on Sunday.

Magnus Linklater begins his excellent introduction to In Case of Any News by saying that he always saw Kenneth Roy as ‘the conscience of Scotland – a writer who gave it a wee nudge when he thought it had strayed off course’. I’d put it slightly differently: that he had a knack for asking awkward questions. If he were reviewing his own book, for example, he’d probably ask what on earth the living could possibly hope to learn from a book written by someone who is dying. He might even have been sceptical about the whole project: that would, after all, be the contrarian position, and Roy never shied away from taking the minority view. What, he might ask, can a writer teach us about Death when it is already in the hospital room, scythe raised?

This drastically foreshortened focus is the truly remarkable thing about Roy’s ‘diary of living and dying’. He began writing it on 4 October 2018, just after being told that his cancer was terminal and ended it on 1 November, four days before his death, and yet for all his caveats about not having had time to edit it properly, it is complete in its own right. A rare and ultra-lucid despatch from very edge of life, it is a last testament of will from a writer who ‘wonders how near the finishing line I can get and still file a line or two of copy’. And that’s the key: these are the final pages of a reporter’s notebook, and he will struggle through sleeplessness and embarrassment (vomiting, soiling the bed) and pain to fulfil that oh-so-simple-sounding journalistic instruction to ‘tell it like it is’.

But that, he says, is the easy bit. Recording what is life like in Room 303, Station 9, at Ayr Hospital is straightforward reportage of the kind that writes itself (yeah, right). The really worrying bit, he adds, is that if he suddenly runs out of any added insights into the business of dying, any last words of wisdom, the whole project will be doomed to failure.

Now this, remember, is what Kenneth Roy has decided he will do with what remains of his life. Finishing this book is his one remaining ambition. Not reading poetry, because the words float away, unabsorbed. Not watching films, because or reading histories because, well, what’s the point? Even music palls. Religion doesn’t help, because he’s not a believer. The news no longer matters and will happen without him. Philosophy doesn’t console, not even Seneca. Pastimes are pointless when there is so little time to pass. But 3,000 words a day: that counts for something, doesn’t it, even if only a fragment to shore up against ruin? Spurred on by his estimable consultant Dr Gillen, he carries on.

Of course, he has his visitors, and they have their place in the reporter’s notebook, although – and again, this is another way in which this book differs from most other examples of this curious sub-genre – they are not its primary focus. As family and friends take turns by his bedside, one is never quite sure who is who. Perhaps he didn’t want to embarrass them, but my own guess is that he didn’t want to dwell on the love and friendship he was leaving behind him lest it undermine his own purpose. Wallowing in self-pity isn’t his style. Nor does he bore us with the details of his treatment, because that’s what they are, just details.

He tells us something of his life, and it’s not remotely what I expected. A bleak background in Bonnybridge, driven to truanting aged 12 by a bullying maths teacher and leaving school three years later without a single qualification. An embarrassing, alcoholic father (‘no good purpose. would be served by a celestial reunion’) and reserved mother. Wondering why he and his sister never talked much about either of them, he notes that ‘dying doesn’t necessarily release inhibition; it can actually reinforce it.’

And if belatedly confronting the past is a strange experience, so too is life on Station 9. ‘Overwhelming love. Overwhelming love. Overwhelming love. I am surrounded by it, wrapped in it, and I am trying to learn at the end of my life to learn how to deal with it and respond to it. It isn’t easy. It’s the most difficult thing I have ever done.’

Read that paragraph again, you can see just how far it is from my initial mental image of Roy (crabbit, cynical, witty etc). Yet his affection for the NHS staff who look after him (and to whom the book is dedicated) is clear enough. If there has indeed been a change in him, it has happened in front of our eyes as we are introduced to them – the assistant nurse who helps him to shave, the nurse who makes time for a kind word before she goes off shift, everyone who cleans up after him or cares for him, or who quietly understands what it’s like to be afraid to go to sleep when you’re not sure if you’ll wake up in the morning. The palliative care expert who quietly asks him if he wants to carry on.

Maybe, if he had time, he would have edited that paragraph about overwhelming love. But that’s the point. He hasn’t. He notices how his whole style is shifting, becoming less energetic, less elaborate and more direct. He has things to say, but it’s getting harder. He is fighting against tiredness, interrupting his own narrative even more than the most po-mo novelist (has that first chapter been lost for good? Has he gone over the top in the heartfelt tributes to Station 9 at the end of his self-penned obit in Scottish Review? Should he have written it straighter, maybe with a joke in the first par?). But he hasn’t time to change anything. It’s there, 49,000 words, at one and the same time raw and thoughtful, and delivered, somewhat miraculously, just in time for that final, and sadly unalterable, deadline.

I wrote earlier on that I had never met Kenneth Roy, and that’s true. But In the course of writing this, I remembered that I had received an email from him. Three years ago, compiling one of those Books of the Year round-ups, I had asked him to pick a couple of books that had impressed him. He replied courteously and in time for my own deadline. So I’d like to repay the compliment. If anyone asks me for my own book of the year, this is it.

In Case of Any News by Kenneth Roy is published by ICS Books, priced £14.99.

The Secret Life of Tartan is a gorgeous and fascinating book on our nation’s cloth, ideal for the fashionista or history buff in your life. Within its pages, Vixy Rae speaks to many people involved in the tartan industry, and in this extract she speaks to Peter Macdonald, a tartan historian.

Extract taken from The Secret Life of Tartan: How a Cloth Shaped a Nation

By Vixy Rae

Published by Black and White Publishing

Peter MacDonald is a man who quite possibly has forgotten more than I will ever begin to know about tartan. Peter is Scotland’s foremost tartan historian; his main area of interest is the Jacobite era and the early commercial production of tartan. And so, in my quest to weave together the whole historical pattern that is tartan, I turned to him as surely the world’s leading authority on its history and its design. I posed a few questions to help ease myself into this new, intricate world of structure and colour, hoping to broaden my knowledge by absorbing some of his. I came away from our meeting convinced that if you were to cut him in half, he would be tartan all the way through – like a stick of rock, only more stylish.

Vixy Rae: How would you define tartan? What is its defining quality?

Peter MacDonald: Historically, the term tartan was used to describe a type of cloth, irrespective of pattern. More commonly, it describes the multi-coloured, cross-barred pattern woven from solid coloured yarns, which distinguishes it from tweed. As a design, tartan is not unique to Scotland but only here did it develop the cultural significance that is inextricably linked to the Highland clans and which later became perhaps the unifying symbol of Scottishness. It is the Fabric of the Nation.

For you, which tartan represents the pinnacle of design in colour and complexity of sett?

There are a number of contenders for the title but perhaps the finest example is the tartan designed in 1713 for the Royal Company of Archers’ first uniform. The tartan was replaced by the Black Watch tartan in the late 18th century but not before it had been used as the basis for Ogilvie and Drummond of Strathallan tartans.

And which is your least favourite?

I’m not a fan of a lot of modern fashion tartans, principally because they often use colours and colour combinations that are non-traditional; for example: pink, yellow, purple and light blue, which I just don’t find pleasing. I also find the current trend for dull and bland colours, such as those of the Outlander range of tartan, visually unsatisfying and historically misleading. In the 18th century, red was the colour of choice for those that could afford it, the gentry were invariably painted in red-based tartans and the majority of surviving specimens reflect this.

What is the earliest surviving garment made from the cloth?

The nature of our climate and soils, together with the need to reuse garments and cloth in the past, means that few old examples of tartan survive. We have nothing that was created before the mid-18th century and only a number of examples associated with the Jacobites.

When was tartan’s defining moment? When did it become noteworthy in historical terms?

If there’s one date that is significant above all others it is 1822, the date of Sir Walter Scott’s Royal Pageant and the tartan jamboree associated with George IV’s visit to Scotland.

There appears to be a revival in the wearing of trews. Do you think this takes away from the Scottishness of tartan use?

No, why should it? Trews (triubhas) have been part of Highland dress since at least the 17th century, long before the development of the modern kilt.

When Sir Walter Scott was planning the Royal Pageant, many clan chieftains apparently had no idea what their tartan was. Or is this a myth?

In 1815 the Highland Society of London set about collecting ‘traditional clan tartans’ in order to preserve them. They wrote to the clan chiefs asking them to submit a specimen of their clan tartan. The trouble was that the idea that there had been such a thing as clan tartans was a recent invention.

The Society’s correspondence reveals that most of the chiefs had no idea what their ‘true clan’ tartan was. The chief of MacPherson supplied a tartan that only a few years before had been a Wilsons’ fancy pattern which they called No.43, Kidd or Caledonia. So many chiefs submitted a piece of Government (Black Watch) tartan, probably because they’d served in the army, that the Society’s officers had to restrict the number that they would accept.

The world is becoming a global village. Is it important for tartan to be celebrated and held in high esteem around the world?

For me, it’s more important to preserve an understanding of the historical use and traditions of tartans for future generations. I was fortunate to have met and learned from some of the significant tartan researchers of the past – now there’s just me. Where is the next generation and how do we collate and preserve our history? The work of the Scottish Tartans Authority is important in helping to preserve knowledge but there’s always more to do.

What is the most obscure tartan that you know of?

Goodness, where to start? The Scottish Tartans Authority has over 9,000 tartans on its database; fewer than one hundred pre-date 1800, so my answer would have to be one of the early 18th century cloths.

Undoubtedly the most obscure tartan, in terms of rarity and uniqueness, is that from the only known surviving coat of the Ancient Caledonian Society (ACS). The coat, which is in the collection of the Scottish Tartans Authority, dates to c1786 when the ACS was formed. The previously unknown tartan was almost certainly designed for the Society and is unusual in having a decorative silk motif woven into it. On each of the red squares there is a white rose and two buds representing King James VIII/III and the Princes Charles and Henry. The use of such obvious Jacobite iconography only thirty-three years after the last execution of a Jacobite leader is extraordinary and shows just how safe it had become to make such references without fear of reprisal. Tartan, with a secondary design such as the rose motif, would have been woven on an early Jacquard-type loom, probably outside of Scotland, possibly in Norwich which was famous for this type of weaving.

Do you have a favourite, little known story about the cloth you could share?

I wove the material for Prince William and Prince Harry’s first kilts. The tartan was the Prince Charles Edward, an early variation of the Royal Stewart tartan, which is said to have been worn as ribbons on the wedding coat of Charles II.

Thirty-odd years later, I was privileged to work on a version of the Prince Charles Edward Stewart tartan that the Scottish Tartans Authority gifted to HRH Prince Charles; a tartan which he often wears when in Scotland.

The Secret Life of Tartan: How a Cloth Shaped a Nation by Vixy Rae is published by Black and White Publishing, priced £25.00

Towards the end of his life Charles Rennie Mackintosh gave up his principal career as an architect and moved to the south of France where he devoted himself to painting in watercolour. This book published by the National Galleries of Scotland explores his career as a landscape painter there, placing his work in the context of the modern movement. The paintings inside are vibrant and colourful, and here we share a few of them.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh in France

By Pamela Robertson

Published by The National Galleries of Scotland

Port Vendres, La Ville Glasgow Museums: Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum

The Lighthouse, Private collection, courtesy of The Fine Art Society, London

The Rock, Private collection

Fetges, Tate: Presented by Walter W. Blackie 1929

Mixed Flowers, Mont Louis The British Museum, London

Charles Rennie Mackintosh in France by Pamela Robertson is published by The National Galleries of Scotland, priced £17.95

Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a few Bond films on the telly. One Bond superfan, John Rain, cannot get enough of 007, turning his fandom into a podcast and now a book. We asked John about his favourite Bond moments.

Thunderbook: The World According to Smershpod

By John Rain

Published by Polaris Publishing

First Bond film you saw

Live and Let Die – saw it on TV as a little kid and loved the snake in the bathroom.

Jane Seymour, Roger Moore,Yaphet Kotto, Julius W.Harry, Geoffrey Holder and Earl Jolly Brown on the set of Live and Let Die. (Photo by Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images)

Last Bond film you saw (this can be a rewatch)

Spectre – for the book!

Favourite Bond film

Heart says Licence to Kill, head says The Spy Who Loved Me.

Favourite Bond girl

Pam Bouvier – Licence to Kill. She can handle herself, and isn’t afraid of Q’s hands.

Favourite Bond gadget

The Lotus Submarine – it’s a beautiful thing.

Favourite Bond double-entendre

“I am now aiming precisely at your groin. So speak or forever hold your piece.”

Favourite Bond villain

Hugo Drax: face like Dracula’s accountant, dialogue like Shakespeare.

Favourite Bond death scene

Bond shooting Elektra in The World is Not Enough. Cold and hard.

Favourite Bond theme song

‘Live and Let Die’ – it’s a masterpiece, and a beautiful combination of McCartney and Martin.

Favourite Bond

Head says Roger Moore, heart says Timothy Dalton. Love them both so much. Daniel Craig probably the best, though, just hasn’t had the best films.

Timothy Dalton, Maryam D’Abo, THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS, 1987 (Photo by Sportsphoto/Alamy)

Thunderbook: The World According to Smershpod by John Rain is published by Polaris Publishing, priced £16.99

Following in the footsteps of Jonathan Meades’ documentary, Off Kilter, Alex Boyd travelled to Lewis and Harris to document his own journey around the islands. Armed with his camera, Boyd took many pictures, capturing the rugged, austere spirit of a special place.

Extract from Isle of Rust: A Portrait of Lewis & Harris

By Alex Boyd

Published by Luath Press

There are many names for the island known as Lewis and Harris (Leòdhas agus na Hearadh), from the poetic the Heather Isle (Eilean an Fhraoich) to the more prosaic the Long Island (an t-Eilean Fada). A few islanders – no doubt affectionately – refer to the third largest island in the British Isles as The Rock. It is a name that does this most diverse of landscapes and habitats something of a disservice, as it so much more than just an outcrop of metamorphic gneiss, granite, basalt and sandstone on the Atlantic edge of Europe.

To my mind, no sobriquet is more apt than that given over a decade ago by Jonathan Meades, who provided us with the title Isle of Rust in his landmark BBC film of the same name. This name, of course, not only refers to the countless corroding tractors, weaving sheds and other visible signs of human settlement but also to the colours of the land: the reds of deergrass and the purple moor grass which make up so much of the moorland. It is a place of great contrast in both light and land, from the largely flat peatlands of Lewis, where the majority of islanders make their home, to the mountains of Harris that rise abruptly in the south, marking out the rocky landscapes so different to the north of the island. It is in settlements nestled in bays and natural harbours or stretched out along seemingly endless coastal roads that Scotland’s largest concentration of Gaelic speakers can be found. It is a place where old traditions such as peat cutting, weaving and crofting sit alongside the modern demands of island life.

I grew up in the Lowlands of Scotland and until I went there, I thought of the Outer Hebrides as being on the edge of the periphery, a place of barren windswept landscapes, of fishing fleets riding high seas, of croft houses and pristine white beaches – a place which had very little in common with the ordered and picturesque farmlands of my native Ayrshire and the once thriving but now rapidly declining coastal towns of the west of Scotland. The opportunity to visit the islands of the northwest would largely elude me until 2013, when I was offered the role of Artist-in-Residence with the Royal Scottish Academy on the Isle of Skye. Based in a studio at the University of the Highlands and Islands at Sabhal Mór Ostaig, I got my first glimpses of the Outer Hebrides while climbing along the Trotternish Ridge in the north of the island, looking west and observing a long archipelago skirting the horizon.

It was a commission to make artwork about the peatlands of Lewis that summer which finally provided me with the chance to experience first-hand the islands I had come to know largely through the eyes of photographers such as Werner Kissling, Margaret Fay Shaw, Gus Wylie and Paul Strand. I had also recently seen Jonathan Meades’ beautiful and bleak Isle of Rust. His vision of Lewis and Harris provided the inspiration for a new series of work which would combine an antique camera, chemicals and rust collected from the land. Leaving Skye to cross the calm waters of the Minch, that great sense of the unknown was further enhanced by Leaving Skye to cross the calm waters of the Minch, that great sense of the unknown was further enhanced by the play of the light – crepuscular rays of light breaking through black clouds and illuminating the Shiant islands to the north. Home to dramatic volcanic columns which bring to mind Staffa or the Giant’s Causeway, they rose from the depths like broken teeth.

Arriving in the harbour at Tarbert on Harris, I drove south, gaining my first impressions of the island as I climbed high over the pass dominated by the Clisham, the highest mountain in the archipelago and part of the range which separates Harris from Lewis. Before the introduction of the road which winds its way over hills and around boulders and lochs, this was once a journey made by sea, explaining why this single landmass has two separate and distinct communities. As I passed Loch Seaforth and the communities of South Lochs, and onward through the village of Ballalan, the rocky terrain gradually gave way to the wider moorland expanses of Lewis and it wasn’t long before I arrived in the harbour town of Stornoway where I would stay for the night.

The next morning began with an early start. I made my way across the winding moorland road to the village of Bragar, where I met local artist and archeologist Anne Campbell. We drove on together to Ness and my first introduction to the Lewis peatlands. We were joined by Anne’s enthusiastic border collie, Bran, who ran ahead of us, stopping only to dig in the mud and occasionally bark at his own reflection in the many pools of water which made up this unfamiliar landscape. In the distance, we observed only a few lonely figures out gathering peat. As we made our way deeper into the moor, with the clouds low and dark above and a featureless horizon beyond, I started to feel a slight sense of oppression, peculiar in such an open landscape. Perhaps it was partly to do with being disorientated, the damp and humid conditions or my first encounter with Lewis’s many insects that flew curiously around us, occasionally biting.

Lining the sides of the road I noticed the many peat banks stretching out towards the water’s edge, the marks of the shovels still apparent. Above them, small stacks of peat awaited collection, laid out in herringbone patterns or scattered around the landscape in rows. Further up the track, we examined peat cut by machine, which, instead of having a pleasing briquette form, was heaped up in piles of cracked and broken cylinders due to being bored from the land. Having seen the industrial-scale destruction that such machines have wrought on the moors of Ireland, Anne and I remarked that they should be banned entirely from the moor. As we began to gain height, we could see the peat road dropping below to reveal a small valley dotted with an eclectic range of buildings: the shieling village of Cuidhsiadar, our destination.

Cuidhsiadar is the site of a practice once integral to island life: transhumance. Islanders would take animals out to graze on the moorland in summer, living there and collecting produce such as milk and butter, which would then help sustain them through the harsh winter months. Structures used to house people here over hundreds of years are now reduced to piles of stones. Around them are scattered a selection of much more contemporary huts, several constructed from tin and some simple wooden dwellings in various states of disrepair. In the far distance, we could see a much older turf-covered structure on the moor, but it was a modern shieling in front of us which drew the most attention. From beneath wooden panels, the vague form of one of the tour buses which used to cross the island could be discerned, gutted and then converted into a makeshift home on the moor. Open to the elements, we headed inside it for shelter and between the upholstery we noticed beds, as well as bags of peat still to be processed. The ingenuity of islanders to re-use and re-purpose items which would long since have been consigned to the scrapheap elsewhere is something I would see again and again.

Following a few days of exploring the island, visiting familiar tourist landmarks such as the standing stones of Callanish, the Broch at Dun Carloway and many journeys back and forward over the Pentland moor road, I started to get a better idea of the landscape that I was working within. Staying in a small post-war croft house in Anne’s home village of Bragar, I began to appreciate the vastness of the moor, the complete absence of trees. Visible from my kitchen window, the North Atlantic stretching uninterrupted to the west. It is an environment where individuals are quietly reminded of their place; of their own smallness in comparison to the sheer vastness of the natural world around them. It is a feeling often lost in towns and cities.

My own experience of moorland had previously been limited to my own wanderings around the south-west of Scotland and my work as a photographer on the vastness of Rannoch Moor, an area claimed to be one of the last true wild places by writers such as Robert Macfarlane, who Anne had guided across the moors of Lewis. Anne had recently published a beautiful collection called Rathad an Isein (The Bird’s Road), a moorland glossary which she had collected along with her sister Catriona, Finlay Macleod and Donald Morrisson. It gives a unique insight into how the moorland is viewed in the Gaelic imagination and experience and includes terms used by those who have worked and cut peat on the moors for many generations. Her offer to accompany me on a walk across the Lewis peatland and to spend a night in her family shieling at the heart of the island was one I immediately agreed to. In the days leading up to the walk, the weather shifted from sunny and pleasant to increasingly cloudy conditions. A change was in the air. As is not unusual on these islands, weather and storm warnings became the main topic of conversation but we decided that we would make the trip out onto the moor regardless. We could only hope that the wind and rain would stay away long enough for us to reach the shieling on the slopes of Beinn a’ Chanaich Mhoir, by the waters of Loch nan Leac.

Looking at an os map our destination seemed remarkably close – only five or six miles away – but with the ground waterlogged and marshy, every step promised to be a torturous effort. The next morning, with a heavy rucksack laden with a camera, food and camping equipment and the prospect of terrible weather and harsh terrain, I still felt energised and enthusiastic about the challenge to come. Leaving the car at the end of the track, I joined Anne and Bran, and we began to make our way along the drowned peat road towards the moor. Our path would follow along the course of the Abhainn Arnol, a shallow river which runs the length of Glen Bragar. To our right loomed Beinn Choinnich (the Hill of Kenneth) while in the distance, the distinctive pyramid form of Stacashal kept my eyes fixed on the horizon.

Passing men loading dry peat into the back of tractors, my eye was caught by something small, box-like and metallic at the edge of the riverbank. On closer inspection, Anne informed me that it was a trap for mink, which, along with hedgehogs, were introduced to the island in the 1950s and ’60s. The mink caused widespread damage to the birds of the moorland and it is only now that many of them are beginning to return in number to the moor. The story emphasises the fragile balance which often exists in such places. Our next pause on the moor was signalled by an excited bark from Bran, who started digging furiously into the peat. Anne explained that we had arrived at her own peat field and that Bran was simply imitating the actions of Anne and her sister, who still dig peat to warm their homes. It was on this site that Anne, whilst digging into a peat bank, found a wooden bowl, the earth giving it up after holding on to it for over a millennium. It was one of undoubtedly many thousands of objects that the moor has held onto, waiting for an archaeologist such as Anne to uncover it and learn something of the people who once made their home there.

It is unfortunate that, unlike the well-excavated and fascinating Céide Fields in the north-west of the Republic of Ireland, little archaeological research has gone into the north of Lewis, an area obviously rich in potential finds. It was this frustration which led Anne to return to university to study archaeology. As part of her Masters dissertation, she walked the land and recorded finds. What she uncovered added hugely to existing knowledge, yet there is still more work to be done. Whatever lies beneath the many levels of sphagnum moss is no doubt well-preserved from the elements, dating from a time when the island was warmer and more densely populated. The villages of the west side suffered worst during the Clearances, a legacy that rings in the phrase ‘Mìorun Mór nan Gall’ – ‘the great ill will of the Lowlander’ – and one I came to understand more deeply in the years to come, as I returned to Lewis to explore township after abandoned township. On a bend in the river, Anne showed me the remains of Thulachan, five grass-covered mounds which were once part of a settlement. Slowly, the river had changed course and begun to erode the site, causing one of the mounds to collapse, spilling its contents into the fast-flowing water. Anne and I explored what was left, finding only charred wood, and then continued on our way, fording the brown, peat-coloured water.

Once across, the landscape stretched out with small undulations to the far hills, with every step across the peat made carefully. I was reminded by Anne that what appears as solid ground on the moor is often treacherous terrain. At one point, my walking pole slid effortlessly down into the bog, disappearing almost completely. The fear of a misplaced step into earth which could swallow me whole helped focus my mind and I followed Anne’s barefoot steps intently. Other dangers included hidden river courses, holes and, of course, being exposed to the elements. Anne told me that on her last trip out, a lightning storm had made its way over the moor and, having known a good friend to have been struck while undertaking a similar expedition (the photographer Finn Ó Súilleabháin), my mind became intent on reaching shelter. We had been walking and exploring now for the best part of an hour. With the weather closing in, wind and rain moving visibly toward us across the open moor, we took shelter and ate a quick snack in the ruins of a shieling with no roof. Sheltering against the high walls and waiting for the rain to pass, Anne commented that this type of easterly weather is known as a ‘Red Wind’ (Gaoth an ear-dheas – Dhearg) in Gaelic. As we listened to the low wind howling around us, I occupied myself by exploring the walls of the shieling, finding rusted pots and an old kettle amongst the long grass. With a break in the rain, we pushed on, at times following the footprints left by Anne from a previous journey made a week before, her tracks still perfectly preserved in the peat.

Passing a picturesque loch ringed by sundews, we stopped by the shieling once used by Anne’s father before making our way onto the final hurdle, going over the top of Beinn Thùlagabhal. Having made it up the muddy flanks, we sat exhausted on the grassy top. Observing the wind and clouds moving quickly over the scene, I saw her family shieling for the first time. Thankfully, it was now close by and I couldn’t wait to get there and find some shelter from the elements. It wasn’t long before we had skirted the edges of Loch nan Leac and were finally sitting inside the shieling, the wind howling relentlessly around us. Having come this far, we decided to erect an improvised roof over the shieling, something Anne had done many times before. Using nothing but plastic piping it wasn’t long before she had created a rigid, skeleton-like frame, which we moved into position on the top of the structure. Standing a few metres above the ground, we teetered on the edge of the building as the wind blew us around, trying to anchor the ribs of the frame using rocks and the heaviest stones we could find. After several failed efforts we finally secured it, something which proved much easier than attaching the roof covering!

The wind caught the canvas roof like a sail, the material whipping around violently as we tried to anchor it. We both danced around the edge of the shieling trying to keep it down, the wind billowing up from the open doors below. After a long struggle – and collecting a few additional rocks – it was finally in place, yet threatened to blow off any time. The rain was now driving hard and the wind getting stronger. Bran refused to come inside the shieling, as he was terrified by the horrendous noise made by the sheets flapping and cracking violently in the wind. It sounded as if a freight train was passing overhead and, although there was only a few feet between us, Anne and I had to shout our conversation to each other. Amidst the chaos of the storm, Anne lit a fire using dried peat and boiled water that she had collected from the loch. After two cups of warm Darjeeling tea, we reached the decision that staying out on the moor in this weather was probably not advisable.

While a quick meal cooked over the peat fire, filling the shieling with smoke, I examined the walls and noticed the carvings for the first time. The oldest – from 1821 – marked the date that the shieling was rebuilt from an earlier structure and another from 1921 commemorated this date. Anne was hopeful that she might add 2021 to the walls of the shieling, which were otherwise bare, save for a carving of a deer and the initials of those who had come before, including the much-loved Gaelic poet, Peter Campbell. Looking out through the open door facing out of the wind, I gazed out onto the moor while slowly starting to warm up. Time seemed briefly to have stopped. With our meal over, we knew that there were only a few hours of light left and that if we didn’t leave soon, we would be forced to walk across the land in darkness, a prospect that could prove dangerous. Still exhausted from our exertions, we packed the roofing materials away and began our long journey back. In my tiredness, I fell into a hollow, my body sinking into a hidden river, a caochan, up to my waist. Completely unexpected, it forced me to focus. Recovering quickly, we forded a succession of rivers and made our way towards the coastline and the village of Bragar beyond. In our tired state, we still managed to make good time.

The light turned from blue to grey to black and as we finally left the moor I had to make use of a torch to see the path in front of me, very thankful that I had Anne as a guide over the unfamiliar terrain. For days after I would be reminded of the journey, as the smell of peat smoke rose again from my belongings; but the memory of experiencing the moor in all weathers I will carry with me for years to come. A few years would pass before I returned to Lewis and Harris, this time with my wife, Jessica. We were on the island to visit friends, to travel out to St Kilda where I was making images for a book, and to spend some time in Stornoway where I’d been offered an interview for a new role at An Lanntair Arts Centre as a curator and help/mentor working with artists from across the Outer Hebrides.

To my great shock, I was offered the job and it wasn’t long before we’d moved our possessions to the village of Bragar, setting up our home in that same croft house from my first visit. We would spend two years on the island, experiencing its stunning summer mornings, with mist hanging above the mirror lochs, through to its harsh winters, where wind and driving rain force you round the fire and keep you indoors for months on end. We slowly began to meet friends, mostly ‘incomers’ like ourselves who had moved to the Hebrides to experience a different way of living. We spent our time with people who had come from across the world to set up homes on Lewis and Harris and received such warmth and kindness during times of both happiness and hardship.

It is the collision of both old and new that makes the Isle of Rust so fascinating to outsiders such as myself and also provides many of the tensions for its inhabitants. It is undeniable that life on the island is changing. The gradual erosion of the influence of the Free Church of Scotland (and Free Church of Scotland Continuing) is accompanied by problems with an ever-ageing population and the greatest issue facing the Outer Hebrides today: that of depopulation, which is far above the uk average. Tourism helps to revitalise island life during the summer months but brings with it many problems, from overcrowded single track roads, to the shortage of housing brought on by second homes and holiday lets, depriving local people of places in which to raise their families. While large parts of Lewis and Harris remain in private hands as sprawling sporting estates, thankfully communities are now taking back control, most notably in Galson in Lewis and the North and West Harris Trusts.

This book then is a collection of photographic sketches I made while living on Lewis, not as a touristic guide, more as a diary made over several years and seasons. It is a visual response to Jonathan’s essay of the same name, which I often had in mind as I explored the themes of ‘Isle of Rust’ in mountains, moors and lochs. Jonathan’s writing has been highly influential on me throughout my life; his essay ‘Death to the Picturesque’ having been a particularly formative influence on my early photographic approach. I’m greatly honoured by the opportunity to include his work within this book and I have tried my best not to deviate from his direction to ‘Emphasise the contrast between natural grandeur and scrap squalor’.

The Outer Hebrides have of course long attracted photographers. However, I have chosen not to follow in the footsteps of Paul Strand, Werner Kissling, Fay Godwin, Gus Wylie and Robert Moyes Adams, who captured the island in stark monochrome, opting instead for colour. I took a truly Calvinistic approach to making images and limited myself to minimal equipment, in this case a camera and two lenses which I could carry across moors or up mountainsides. I photographed things as I found them. There are no attempts to create postcard images, no specialist filters, no long exposures of the incoming tide at Luskentyre, no misguided attempts to create anthropological studies of the islanders. There is only the available light, and the colours as my eyes experienced them. The beauty of the Hebridean landscape and light speak clearly enough without my interventions. This approach does come with its own limitations, the most challenging of which is to communicate the endless changeability of light, the sheer variety of landscape and the complex, multifaceted nature of the place.

It would, as poet Norman MacCaig once said in ‘By the Graveyard, Luskentyre’, take a volume ‘thick as the height of the Clisham’ and ‘big as the whole of Harris’ to even begin to scratch the surface of gneiss, peat and lochan.

Isle of Rust: A Portrait of Lewis & Harris by Alex Boyd is published by Luath Press, priced £20.00.

A few of the books we’ve been showcasing this issue celebrate the beauty of Scotland’s landscape. Scotland’s Mountain Landscapes by Colin K Ballantyne is a brilliant guide to how our landscapes were formed through time, perfect reading for hillwalkers everywhere who want to understand more about the ground beneath their feet.

Extract taken from Scotland’s Mountain Landscapes: A Geomorphological Perspective

By Colin K Ballantyne

Published by Dunedin Academic Press

Mountains represent the essence of Scotland’s scenery. Postcards, calendars, shortbread tins and dishtowels seeking to capture ‘Scotland’ in a single image almost invariably depict a mountainous Highland landscape, sometimes with a loch or castle in the middle distance and a kilted bagpiper artfully (and sometimes digitally) inserted in the foreground. They are a fundamental part of Scottish identity, for though most Scots live in the towns and cities of the lowlands, the mountains are close by on the horizon, a line of purple or snow-covered peaks that reminds us of another Scotland where the interplay of sunshine and cloud over rocky crags, deep lochs, windswept plateaux and lonely moorlands creates a sense of wilderness and an opportunity to escape from our urban hinterland.

And escape we do. When the weather is favourable, thousands of hillwalkers visit the summits of Scotland’s mountains every week, many with the aim of completing the ascent of the 282 Munros (summits over 3000 feet or 914 m). Rock climbers are drawn to the crags and corries of Skye and Glen Coe, skiers to the snowy slopes of Glen Shee and the Cairngorms, and others come to the mountains for fell running, mountain biking and even hang gliding. Outnumbering all of these, however, are the visitors who come simply to marvel at the most wonderful scenery in the British Isles.

Nobody who has explored the mountains of Scotland can fail to have been impressed by their sheer diversity. The isolated sandstone peaks of the far northwest, the serrated gabbro ridges of Skye, the granite high plateaux of the Cairngorms, and the rolling uplands of southern Scotland represent a variety of mountain landscapes that rivals any on Earth. Such diversity

reflects not only Scotland’s tumultuous geological evolution, which has created a mosaic of contrasting rock types, but also the operation of a wide range of erosional processes that have sculpted the underlying rocks into the wonderful topographic variety of Scotland’s mountain landscapes. Some of these processes operated in deep time, many millions of years ago, others throughout the

Ice Age, and many, such as frost action, rockfall and river erosion, have continued to modify mountain landscapes since the disappearance of the last glaciers.

In this book we shall take a journey through time, beginning with the formation of the oldest rocks and ending with the manifold processes that are still operating on high ground. We shall visit past eras when Scotland lay near the Equator, when alpine-scale mountains towered over the landscape, when volcanoes spewed out copious lava flows, when ice covered the land, and when earthquakes triggered major landslides. Mountain scenery is always inspirational; but understanding how mountain landscapes have evolved deepens our perspectives of time and space, and the transience of human existence. Just 12,500 years ago, for example, Scotland looked like high-arctic Svalbard today: a great icefield occupied the western Highlands, a valley glacier was advancing to the southern end of Loch Lomond, permafrost underlay the ground beyond the glaciers and mean July temperatures were no higher than those in November at present. Understanding such events and their effects on the landscape can make a day in the Scottish mountains a thrilling excursion that spans millions of years.

The images here are examples of the diversity of Scotland’s mountain landscapes. (a) Suilven (731 m) in NW Scotland, a sandstone mountain rising above glacially scoured gneiss (photograph by John Gordon). (b) Sgùrr Dubh Mór (944 m) and Sgùrr Dubh an Da Bheinn (938 m), Cuillin Hills, Skye. (c) The eastern Grampians, with the Cairngorms on the skyline. (d) The Southern Uplands: White Coomb (821 m) from Hart Fell.

Scotland’s Mountain Landscapes: A Geomorphological Perspective by Colin K Ballantyne is published by Dunedin Academic Press, priced £28.00

Eating vegan is becoming increasingly common, but it doesn’t necessarily follow that this healthy diet means no indulgences are allowed. Stefanie Moir, has written an excellent book on vegan eating and fitness, but hasn’t forgotten to put in the treats! Here are two of her very delicious recipes . . .

Recipes taken from Naturally Stefanie: Recipes, Workouts and Daily Rituals for a Stronger, Happier You

By Stefanie Moir

Published by Black and White Publishing

Tofu Chocolate Mousse

I know, tofu and chocolate do not sound like a winning combination but, trust me, this mousse is utterly delicious. Served in cocktail glasses or ramekins, it’s a perfect pudding for dinner parties.

Ingredients

300g silken tofu

100g vegan-friendly chocolate

80g maple syrup

1 tsp vanilla extract

pinch of sea salt

- First melt the chocolate in a bowl over a pan of boiling water or in the microwave.

- Drain and remove excess moisture from the tofu.

- Add the tofu, maple syrup, vanilla and salt to a food processor and combine until smooth.

- Then add in the melted chocolate and pulse until well combined.

- Pour the mixture into ramekin-style dishes, filling up around a quarter of the dish and place in the fridge to set.

- To serve, top with vegan whipped cream and chocolate – optional!

Blueberry and Lemon Pancakes

Ingredients

200ml almond milk

100g oats

35g vegan vanilla protein powder or

substitute with 35g of oats

1 ripe banana

1 tsp baking powder

150g blueberries (plus extra for topping)

juice and zest of 1 lemon

- First, juice and zest the lemon. Set the zest to one side – you’ll use it as a topping for the pancakes later

- Lightly grease and preheat a non-stick pan over a medium heat.

- Using a blender or whisk, mix together the oats, protein powder, banana, baking powder, lemon juice and almond milk to form a smooth batter. Then add the blueberries.

- Once the pan is hot, pour the batter into the pan until desired pancake size is reached.

- Cook the pancakes until the surface begins to bubble and the edges turn brown then flip and cook on the other side. This should take between 4 and 6 minutes.

- Remove from the heat and transfer to your plate or into the oven to stay warm.

- Top with the extra blueberries and lemon zest.

Naturally Stefanie: Recipes, Workouts and Daily Rituals for a Stronger, Happier You by Stefanie Moir is published by Black and White Publishing, priced £16.99

Following your local football team, it’s often the hope that kills, but not if you’re Mat Guy. He has travelled the world cheering on the small teams, the teams without the million pound sponsorship deals but with a loyal, loving following. BooksfromScotland spoke to Mat about his travels and his love of the game.

Barcelona to Buckie Thistle: Exploring Football’s Roads Less Travelled

By Mat Guy

Published by Luath Press

Your new book Barcelona to Buckie Thistle: Exploring Football’s Roads Less Travelled has just been published. What is it about the ‘minnow’ football teams playing out of the limelight that keeps you coming back?

For me they are the very essence of the beautiful game, these smaller teams. Shorn of crowds in the tens of thousands, there is time and space to see the small acts of love and devotion that any given supporter performs on a match day. From passing through a ‘lucky’ turnstile that they first used as a child, hand in hand with a parent or grandparent, to meeting up with old friends on the same scrap of terrace – a spot made sacrosanct by the generations before, who assembled there in days long gone.

The smaller the team, the greater the connection between club and community, who rely on each other to survive and thrive. Meaning, belonging, identity fuels any supporter’s passion for their club or national team. At a club attracting crowds in the hundreds, or low thousands, it is easier to see just how important these sporting institutions really are. How much they really mean. It chimes with my first trips to see my grandfather’s team, Salisbury, as a young boy.

The book visits teams from the Scottish Highlands right across to places like the Faroe Islands, Azerbaijan and Liechtenstein. How did you find out about the teams included in the book?

I have always held a fascination for the unknown, fuelled by a box of old National Geographic maps at my Grandfather’s house. We would pour over them and imagine what far away places looked like. When I fell in love with football, I began to do the same to far away national teams, or obscure sounding club sides. They fascinated me far more than the bigger teams. So, in that respect, I have been training all my life to seek out those teams on football’s road less travelled!

In researching for Barcelona To Buckie Thistle, I went back to that tried and tested method, albeit aided by modern cheats such as google maps and Wikipedia! Being the most northerly senior football league in Britain, the Highland League really did stand out to me as a league I needed in my life. I was proved right!

So many football teams, whether playing in league teams or not, exist around the world. Have you found many differences in the game being played by teams in different countries?

No matter the cultural or religious differences from country to country, the language barriers in place, as soon as players cross that white line and the whistle is blown, we all speak the same language: football. No matter where I have been in the world in the name of football, I have had immersive, enthralling experiences with people whom I couldn’t understand a word of, and they couldn’t me! Cheers, sighs, gesticulations, smiles, shakes of the head and raised eyebrows – we all understand the passions the beautiful game instils in us. It is a universal, wordless language just like mathematics. It is joyous.

Is there a moment from your travels researching the book that stands out for you?

There are so many moments! But one that stands out came from a UEFA Nations League match between Liechtenstein and Armenia. As the turnstiles opened and the 1,000 or souls brave enough to face down a bitterly cold Alpine night in late November began to file in, two boys stood handing out match programmes. One, so eager to make sure everyone got a copy, had overloaded himself, his arms stuffed. As he tried to hand them out, they began to cascade to the floor. Mortified, he bent down to try and collect them, only for more to tumble! Thankfully a few locals helped him corral them back up – though his colleague didn’t, bent double as he was in fits of laughter!

But it served to highlight to me, this boys desire to do his job well, the pride he had in serving his national team in this menial task. It meant something. Possibly the world to him. Doing it right mattered. Just as fixtures down among the small print in newspapers matter, to the passionate few whose teams and communities live there.

This is your third book on the beautiful game – is there anything new that you’ve learned about the sport or from the teams that you’ve met?

I’ve learnt humility from the Bhutanese and Tibetan teams I have met, who bring a unique, Buddhist perspective to the sport. Meeting a Palestinian player whose career was cut short by detention in an Israeli prison certainly opened my eyes to a world I had never seen before. But, ultimately, it is the same precious lessons that I have re-affirmed on almost every trip I take, that football is about community, people, friendship, belonging. It is purpose, pride and identity. Whether at Victoria Park, Buckie, or the Camp-Nou, Barcelona, the meaning is the same. The only difference are the numbers in attendance.

Barcelona to Buckie Thistle: Exploring Football’s Roads Less Travelled by Mat Guy is published by Luath Press, priced £12.99.

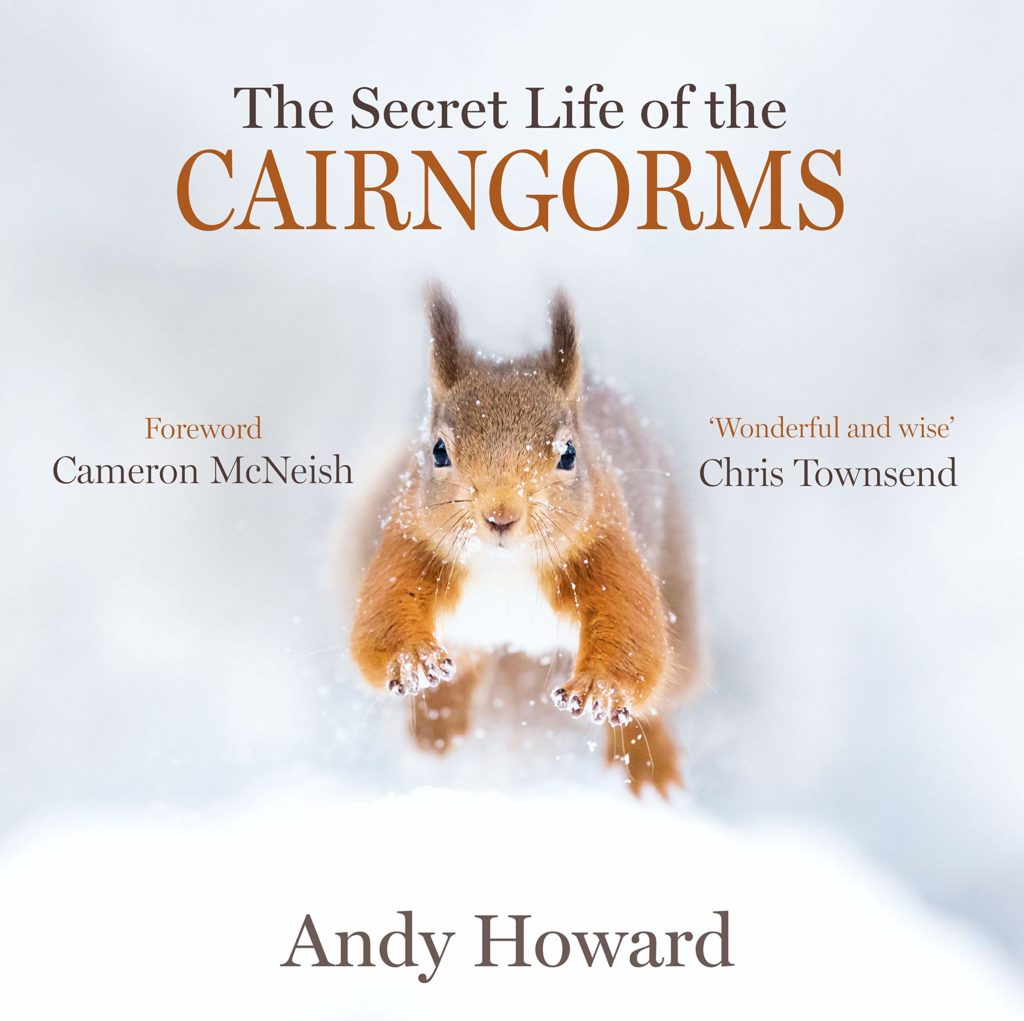

Andy Howard’s photography books are becoming very popular on people’s Christmas lists, his obvious love for nature shining through in every picture. BooksfromScotland caught up with him to chat to him about his photography career so far.

The Secret Life of the Cairngorms

By Andy Howard

Published by Sandstone Press

What came first, your love of nature or photography?

What came first, your love of nature or photography?

My love for nature started at about the age of five when my parents gave me the AA Book of British Birds. It has the edition with a tawny owl on the cover, which I remember vividly. I spent hour upon hour soaking up the images of birds.

Do you remember when you first picked up a camera? Did your ‘eye’ come naturally?

My early attempts were with a Kodak box brownie. The results were not special, but the experience gave birth to my present passion for photography. On my sixteenth birthday I progressed to a Minolta SLR, and my first wildlife camera, a Canon, on my eighteenth.

How and when did you make your hobby into a profession?

With a leap of faith! I’d been working in Retail and catering for twenty eight years and, by that time, had enough. It was time for a major change in my working life. I formulated a business plan, ran it by some friends, who were also business advisors, and off Lindsay and I went. In the first year I had to combine my new profession with consultancy work and even worked as a’ mystery shopper’ to make ends meet. Luckily, things took off in year two.

Do you have any easy tips for capturing perfect moments?

The first and most important is follow your heart. No one succeeds without a passion for the subject. Secondly, my best images are pre-planned, sometimes months, even years, in advance. Thirdly, know your subject, the more you work with a species the more predictable its behaviour will become. Utilise this knowledge! Lastly, master the technical aspects of digital photography. Do all this and your creative juices will start to flow. Remember that photography is an art form.

Your first book The Secret Life of the Mountain Hare had a great reception. How long did it take to put that book together?

The images took approximately seven years to capture, and the process of getting the book onto the shelves took ten months from the first meeting with Sandstone Press.

Your latest book widens out to include more Highland wildlife. How often are you roaming the Cairngorms with your camera?

It seems that the busier I get both in my roles as a guide and author, the less time I have to capture new images. It’s now six months since I was in the Cairngorms. Another good reason for my attention being elsewhere is that I am now working on my third book, which takes me to the beautiful islands of Mull and Shetland.

The Cairngorms feel like an endless subject for a photographer. How did you whittle your images down?

I’ve learned to take fewer photographs, and be more frugal with my shutter release button. This helps. I find that after a day in the field there is likely to be only one or two images that make the cut. All others get filed on a hard drive, often never to see the light-of-day again.

Do you have any ‘bucket list’ places you’d like to take your camera?

Lindsay and I fell in love with Canada a few years ago and have so far returned twice. I’d love to go to Antarctica, St. Georgia and Svalbard, but would prefer not to be surrounded by hundreds of other wildlife watchers and photographers. That’s one of the many reasons I love Shetland. Through three weeks there in September I didn’t see another photographer. I love the solitude; just me, the wildlife and my camera.

What are you looking forward to this festive season?

Time with my family. For the first time in many years we’re making the journey south of the border to be with my mother in the Cotswolds, where a few mince pies may be consumed.

The Secret Life of the Cairngorms by Andy Howard is published by Sandstone Press, priced £24.99

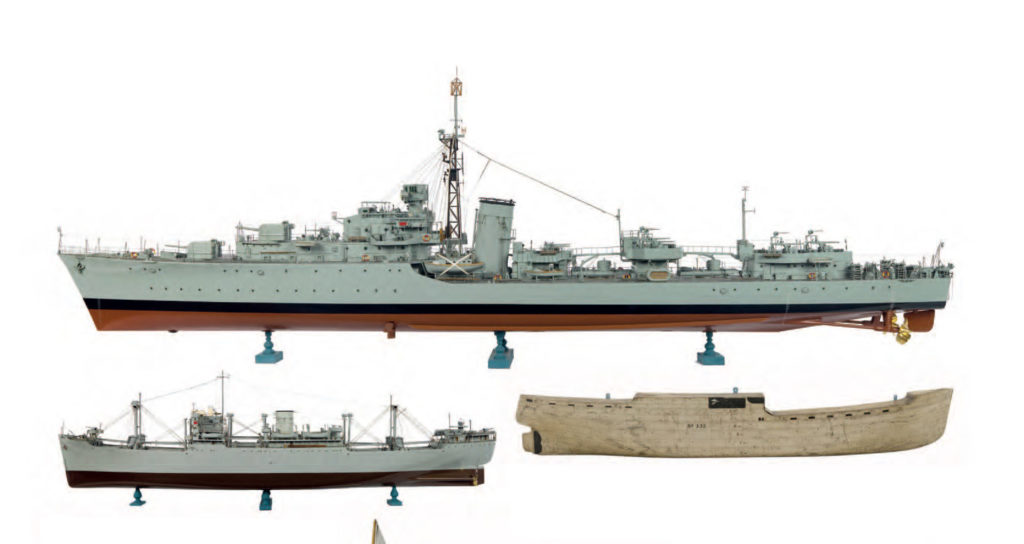

Glasgow Museums have an impressive array of ship models in their collections and have gathered them together in a lovely volume that’s an ideal gift for model enthusiasts. We hope you can appreciate the intricacy of the craft in these images, even inspire a trip to their museums in the Christmas holidays!

Images taken from Glasgow Museums: The Ship Models

By Culture and Sport Glasgow

Published by Glasgow Museums

Both of these ships are prisoner-of-war models made by French sailors held in Britain during the Napoleonic Wars, early 19th century; bequeathed by Col CL Spencer.

This prisoner-of-war model is shown at more than twice its actual size in this picture.

The top ship, Finisterre, is a shipbuilder’s display model given by Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Co. Ltd.

The bottom left hand ship, City of Chester, is a shipbuilder’s display model given by Barclay, Curle & Co.

The bottom right hand ship, Kaimanawa, is a shipbuilder’s plating model by Henry Robb Ltd, Leith, for the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand Ltd.

Glasgow Museums: The Ship Models by Culture and Sport Glasgow is published by Glasgow Museums, priced £35.00

Scotland Street Press have just published a beautiful history of Edinburgh told through the lives of those who have lived and worked in 66 Queen Street. It’s an excellent social history, full of brilliant insights to the little known stories that influenced the city’s great moments. In this extract, we find Robert Louis Stevenson attending the trial of an acquaintance, charged with multiple brutalities despite his respectable appearance. . .

66: The House That Viewed the World

By John D. O. Fulton

Published by Scotland Street Press

Enter Hyde

Chantrelle was an acquaintance of Stevenson. His continuous presence for the trial’s duration suggests that Stevenson was keen to gain an insight into the complex alter ego of an educated and talented man who had murdered his wife. Another figure of notoriety, who had fascinated Stevenson as a boy was Deacon Brodie, a locksmith and respected town councillor, who had committed his crimes ninety years earlier. Brodie had confined his activities to armed robbery and more particularly burglary. These were committed at night by him gaining entry to houses through using copy keys he had cut for the new locks he had fitted for his trusting clients. Like Chantrelle, the scaffold awaited Brodie but the nature of their crimes was quite different. A far greater darkness lay within the soul of Chantrelle. He had abused his wife and other women whilst expressing no empathy or pity for those whose lives he had ruined or, in the case of his wife, taken.

To try to understand what may have been the fascination which drew in Stevenson, one needs to look at his early life. He was brought up as an only child in the New Town of Edinburgh by parents who were devout and serious Presbyterians: a situation fortified by his faithful nurse who held strong Calvinistic and folklore beliefs. For her the theatre was the ‘mouth of hell’ and she filled the head of young Louis with, amongst other terrifying images, the blood-drenched religious fundamentalism of the two previous centuries. Her remedy for her charge’s frequent bouts of insomnia was a cup of strong coffee in the middle of the night which, with the ill-health he suffered through a weak chest, induced powerful dreams and nightmares in which reality was bent between the conscious and the unconscious. Even as a student his dreams were so real he felt that he was leading a double life making him fear for his sanity.

. . .

The Chantrelles, Henry Littlejohn Collection

He had gained some insight to Chantrelle’s ‘quite remarkable powers’ during a chance meeting one evening in the street. Chantrelle asked Stevenson if he had seen a mutual French friend’s translation of Molière. Stevenson said that he had but did not rate it. ‘His eyes blazed with hope, had me to a public house; and bidding me name any passage of Molière with which I was well acquainted, offered to improvise without the book a better version than their mutual friend.’ The challenge was accepted and, as far as Stevenson could judge, he did well what he professed. Stevenson said he was in no position to judge fairly and he must be given a written copy before he could, as desired, approach a publisher on Chantrelle’s behalf. Nothing more was heard from him and ‘the spark of hope … must have died out’. The next occasion Stevenson found himself observing Chantrelle was in the High Court of Justiciary when the latter was listening ‘with singular and painful changes of countenance, the evidence of his own trial for murder.’

Chantrelle had been born into privilege in Nantes in 1834. His father, who was a shipowner of some repute, provided his son with an excellent education which led to his son’s attendance at Nantes Medical School where his ability earned him a commendation. For reasons that are not clear but may be associated with his father suffering commercial hardship due to the French Revolution of 1848 Chantrelle was no longer able to continue his studies at Nantes but managed to continue them by attending classes in both Paris and Strasburg. These events unsettled him and his aspirations for a career in medicine faded. Instead, by seventeen, he had become a Republican. In 1851 he manned the barricades in Paris where he was wounded in the arm by a sabre. The success of Louis-Napoleon no longer made France a country he could identify with. America beckoned and he spent several years there although what he did there remains unknown. In 1862 he arrived in England where in different regional cities he worked as a French language teacher. By 1866 he was teaching in Edinburgh and was proving himself an excellent linguist in French and German with a proficient knowledge of Latin and Greek. He had further enhanced his reputation by compiling several textbooks which had been adopted by many of the local schools. It was in one of these schools, Newington Academy, that the thirty-four-year-old Chantrelle, replete with a cultured and polished manner, met the fifteen-year-old Elizabeth Dyer.

Seduced by him Elizabeth fell pregnant and her parents forced Chantrelle into marriage on 11 August 1868. The first of their four children was born two months later. The marriage was not a happy one with Elizabeth regularly being subjected to abuse, both mental and physical, in the knowledge that her husband was systematically unfaithful to her. She fled to her parents repeatedly and, on at least two occasions, the police were called in for her protection. Chantrelle threatened to shoot Elizabeth with a loaded pistol and frequently said he would poison her whilst taunting her that he had the knowledge to do so without medical detection. Poor Elizabeth was caught in a bind. Her parents were not prepared to intercede; and having taken legal advice, although she knew she could sue for divorce on the grounds of adultery, the public shame of doing so and the risk of forfeiting the care of her much-loved children prevented her from taking action.

Chantrelle’s unacceptable behaviour, amplified by drunkenness, took its toll at work. His classes dwindled and financial difficulties and debt set in. It was perhaps an increasing sense of desperation in a man who had lost his self-control that led him to make enquiry of two insurance companies about taking out life insurance policies on the life of his wife and himself for the sum of £1,000 each, and on the life of the maid for £100, all payable in the event of an accident. With the first policy he asked if the company, Accidental Assurance Association of Scotland, were in the habit of insuring women (which they were not) and mentioned that his son had accidentally shot him with a loaded gun which had been sitting on the table injuring his hand. It was this event he said that persuaded him to insure himself and his wife against the risk. With the second company, Star Accidental Insurance Assurance Company, he wanted to know what constituted an accident. Amongst scenarios he mentioned the case of a friend who had eaten Welsh rarebit in a hotel and was found dead in his bed the next day. Would that be covered by the policy? In the circumstances of the case the insurer’s answer was firmly ‘No, certainly not’. The policies were taken out with Accidental Assurance on 22 October 1877. This was done very much against the wishes of Elizabeth who informed her mother that she feared for her life pointing out that her husband had more than once threatened to take it.

At the trial witnesses testified to Chantrelle’s abusive behaviour towards his wife and of her opinion that he visited brothels. It was then that the witness Barbara Kay was called: a person whose presence in the witness box Stevenson would observe with acute interest. For Barbara Kay was the keeper of the brothel in Clyde Street frequented by Chantrelle and only a short distance from the Stevensons’ house. The brothel would have been a destination shared by other respectable gentlemen in town. A heave of collective relief may have been heard from within their number when the Lord Justice Clerk announced that what had already been proved of Chantrelle’s behaviour was quite sufficient for the Crown’s purposes. The gossamer layer between the public perception of good and evil remained unbreached.

Evidence was given that up to New Year’s Day of 1878 Elizabeth had been in good health but that evening, because she was feeling slightly unwell, she retired to bed early in their home at 81a George Street, Edinburgh, where the family lived on the two upper floors. Her servant had been given the day off leaving Elizabeth at home with her children and her husband. On the servant’s return at 10pm she found her mistress in the back bedroom with her baby beside her ‘looking very heavy’ and not well. There was a tumbler of lemonade three-quarters full beside her bed and Elizabeth asked her servant to peel an orange for her. The servant gave her mistress a quarter and left the remaining three segments on the plate. Retiring to bed Chantrelle slept in the front bedroom with his two older children. The next morning, on rising, the servant heard moaning from Elizabeth’s bedroom. The door usually closed was partly open. She found her mistress lying unconscious on the bed with stains of vomiting upon the pillow. She called her master who was in his own bedroom with the three children. He returned with her and tried to rouse his wife; the servant suggested he call for a doctor.

Chantrelle claimed he heard the baby crying and told the servant to attend to it. The servant found the baby still asleep and returned at once to the bedroom where she found Chantrelle moving away from the window. He said, ‘Don’t you smell gas?’ She did not immediately smell it but after a slight delay did whereupon she turned off the gas at the meter. Dr Carmichael was called and when he arrived the room had a pervading odour of gas. Chantrelle explained there had been an escape. The doctor called for Dr Littlejohn, the city medical officer, ‘to see a case of coal gas poisoning’. Upon Littlejohn’s arrival both doctors because of Chantrelle’s assertions and the smell believed Elizabeth to be suffering from gas inhalation. Remaining comatose Elizabeth was admitted to the Royal Infirmary where the ward doctor diagnosed the case as not one of gas but of narcotics poisoning, probably opium, and he treated the patient accordingly. At 4pm, Elizabeth died without regaining consciousness. The post-mortem examinations ruled out gas as the cause of death but failed to detect the narcotic poisoning indicated by the symptoms. Analysis of the stains of vomit on the bedclothes and the pillow, however, proved the presence of opium together with the orange pulp.