Nate Yu’s Blast from the Past is a bighearted tale of family, forgotten stories and the search for belonging, from award-winning author Maisie Chan. BooksfromScotland caught up with Maisie to talk about the inspirations behind her book.

Nate Yu’s Blast from the Past

By Maisie Chan

Published by Piccadilly Press

Hello Maisie; it’s fantastic to see another book of yours out in the wild! What can you tell us about Nate Yu’s Blast from the Past?

Yes, I’d love to tell you all about my latest novel Nate Yu’s Blast from the Past! The book is about Nate who’s a myrmecologist which means he studies ants. His mums are kind, but Nate thinks they don’t understand him because they’re not Chinese. He makes a couple of new friends, and everything changes when he gets his hands on a shell casing from the First World War that is engraved with a Chinese dragon. He meets a ghost from the Chinese Labour Corp who doesn’t remember why he’s appeared. It’s a book about identity, untold histories and it has ant facts, karaoke and more surprises.

The book starts with Nate coming to terms with moving with his family from the country to the city of Liverpool, and to a new school. What did you want to explore with that ‘fish out of water’ dynamic

Many kids move schools, houses, or to different areas and I think often it’s underestimated how much that upheaval affects them. It’s a big thing but then throw in the mix the fact that someone has moved to a big city from a small village, and you have even more tension and things to get used to. I really like the ‘fish out of water’ dynamic and have used it a few times in my other novels. Nai Nai moved from China to Birmingham in Danny Chung Does Not Do Maths, Lizzie Chu from Keep Dancing, Lizzie Chu needs to take Wai Gong from Glasgow to Blackpool but she’s only twelve – it allows for different encounters with new and sometimes challenging things. I guess, you could say I am exploring resilience and what happens when the familiar becomes the not-so-familiar.

You work in such lovely details into your books (we’re big Beatles fans at BfS, so we appreciated the school’s House names); we loved too Nate’s passion for his ant farm. Where did you come up with that part of Nate’s character?

The ant fact part of the book was pure serendipity. I was walking my youngest child to school, and they told me an ant fact (very much out of the blue). It was – if you squash an ant, it releases pheromones so the other ants will come and find the dead body to take it away. I knew there and then that I had to use it in my book, and I asked if it was okay. I like to give my main characters interests. It worked out perfectly because there was a link between ants and the men who worked in the Chinese Labour Corp. Each chapter of the book begins with an ant fact, and I tried to make each fact link to what was happening in that particular chapter. I like my readers to learn something new, which is an idea I got when reading Frank Cottrell Boyce’s books because I realised that I was learning a new fact about something in each of his novels.

You’ve introduced a supernatural element to Nate Yu’s Blast from the Past with the character of Jirou. Why did you want to move into this imaginative territory?

I always like to challenge myself. Writing contemporary books is within my comfort zone, so I wanted to see if I could write a contemporary book about history but also have a ghost in it. I need to keep the writing process interesting for myself and I wanted to have fun, plus young readers love ghosts in their stories. I found it hard to think about what the rules of the ghost appearing were because there are lots of different kinds of ghost stories – some are scary, some dark, some funny. I wanted my ghost to be in the funny camp – so it’s a bit like BBC’s Ghosts where only Nate can see him, and he’s got a mission. I want to continue to write for a long time if I can, so I am always looking for ways to write things that make it fun.

You’ve also shone a light on a moment in history that often doesn’t get talked about, the Chinese Labour Corp and their experiences in World War One. Can you tell us more about this? Do you remember when you first learned of them?

As far as I can tell there are very few books for children in the UK that mention any British Chinese history. I can’t actually think of one and I wonder if your readers can think of any. I remember studying history at school but finding it quite irrelevant for me. I think it’s that idea of not being seen as part of history and in Britain there is a constant feeling that we can’t forget the world wars we’ve been involved in. However, when I found out there were around 140,000 Chinese people in France who were helping with the war effort I wanted to tell others about it. I think I found out about the Chinese Labour Corp about ten years ago. I was surprised and had never heard about them as a child or even a young adult. I know in recent years there has been a play called Forgotten made about them and numerous documentaries. I read a few books about them by historians, and I read one book which was a fictionalised version which I found disturbing as it kept using a racial slur the whole way through. I felt that moving across the world also mirrored Nate’s move to a different place and I thought it would be brilliant for a Chinese ghost to help Nate with his issues about being Chinese.

Nate Yu and your previous books have often had your characters grapple with their heritage, and we loved how Nate and Missy responded to each other (even if their first encounter at the assembly gave us anxiety dream flashbacks!). How have readers responded to these explorations?

I do explore what it feels like to be an outsider or to not belong. It’s a common theme in my book and that’s because I am exploring my own feelings of not belonging. I am a transracial adoptee just like Nate and like Nate I didn’t feel Chinese enough and even pushed away ‘Chinese stuff’ as a child. This is why I feel it’s important for me to write about the themes that I do and to include things that are related to Chinese culture because it goes back to the idea of mirrors and windows. I am trying to write for multiple readers – ones who may have a connection to Chinese culture or who look Chinese but feel marginalised, and also those who know little about Chinese culture. I think readers have responded well, especially in Britain as my writing is very British and there is a lot of empathy in my books. I’ve had lots of lovely reviews from fellow authors and a few of them said how relatable it is for diasporic kids who might have heritage from different countries but who are also British.

Although you’ve probably spent the last few months focussing on your writing, what are your favourite books you’ve read this year so far?

I enjoyed The Shrapnel Boys by Jenny Pearson which is a Second World War book about boys in London who have to endure time in bomb shelters, but it also explores big subjects like fascism and male role models. I thought it was very clever. I also admire how Jenny has gone from writing very funny books to this fairly serious historical novel, although it also has lots of moments of humour. I’m reading The Doughnut Club right now by Kristina Rahmin and it’s about a girl who finds out she has sixteen donor siblings, and she wonders if any of them are like her.

Nate Yu’s Blast from the Past by Maisie Chan is published by Piccadilly Press, priced £7.99.

Ideal for readers of The Last Witch in Scotland, The Witches of Vardo, Bram Stoker or for those with an interest in witchcraft lore, Scott O’ Neill’s novel tells the tale of a curse in 19th century Edinburgh. In this extract, we find out the origins of the curse.

The Witch, the Seed and the Scalpel

By Scott O’ Neill

Published by McNidder and Grace

‘What did she do?’ The question issued from the back of my throat in a dry, nervous rasp.

‘She did what all witches do when their monstrous intentions are thwarted. She prayed. But she prayed not to our one true Lord God in Heaven, for her heart did not flow with the love and truth of Christian blood. No, her heart was a coal-black stone of hate and spite. So at midnight on All Hallows’ Eve she climbed to the top of Calton Hill, sat herself upon the grass and lit a small fire made from the bones of her most recent victim. With eyes closed and the flames warming her cruel, hideous face, she pushed her hands into the dirt and prayed for her master to appear before her. When at last she stopped her incantations, she opened her eyes and with immense joy she saw the Devil himself standing before her. He smiled, ran a hand through the hair of his adoring disciple and asked why he had been summoned. The Witch McKay begged him to grant her the power to enter the dreams of all Edinburgh’s children so that she might fill their sleep with nightmares of such terror and horror that they would die in their beds of fright.’

As Father said this, a little pile of rust-coloured leaves became entangled in a spiralling breeze and were scattered across the hollow.

‘And did he?’ I swallowed, anxiously. ‘Did the Devil grant her the power?’

‘Satan said not a word. He simply kissed the witch on the cheek and was gone. The very next night, from the Castle to the Tolbooth and all the way to the Palace of Holyrood, the air was filled with a terrible noise. A noise so awful it chilled every last soul in the city to their very core. Can you imagine it? The screams of all those infants echoing through the alleys and streets. Can you imagine the sheer terror of all those sleeping children? Their nightmares filled with visions of the Witch McKay, her eyes as red as fire, her teeth sharper than broken glass? Can you imagine them in their beds so terrified that their poor hearts simply burst with fear? That is no way for any Christian child to die. But die they did. In their scores. Eventually the screams faded and were replaced by the sobs of countless mothers and fathers mourning their dear departed children. It was undoubtedly, the bleakest night in all of Edinburgh’s long and cruel history.’

My gullible young mind had no difficulty at all imagining in stark, unhurried detail all the macabre horrors Father described. I retreated from the twisted, malformed tree with a shiver.

‘But the witch was caught, wasn’t she? You said she was executed. That means she was caught, yes?’

‘She was discovered hiding in a cave near the summit of Arthur’s Seat by a group of boys not much older than you are now. Margaret McKay tried to scare the boys away, but they were a cocksure and insolent bunch and not easily frightened.

They had no inkling as to who this strange hermit woman was, living in a grubby hole full of animal bones and foul-smelling potions. It was not until they came upon a horde of strange little boxes piled one atop the other at the back of the cave that they began to understand her true nature. The oldest boy opened one of the boxes and found inside a tiny doll, its eyes closed and little arms folded across its chest, looking for all the world like a tiny body at rest inside a coffin. It was then they realised they were in the presence of a witch and the miniature coffins were in fact the tools of her devilish trade; the very tools used to cast spells on those innocent children who went to bed with their heads full of pleasant dreams until the witch’s curse turned them into the terrible nightmares from which they would never awake. But thanks to those foolhardy lads, Margaret McKay was apprehended before she was able to lay waste to another soul.’

Father reached down to gather a handful of the rich, mouldering earth. He brought the little heap close to his keen eyes, studying it minutely.

‘It was here that the witch was hanged, her body burned to ash and the ashes buried where no one should ever find them.’

‘Good. I’m glad. It was no more than she deserved,’ I said, heartily relieved to hear the story had a happy ending.

‘And yet, the old legend persists…’ he mused in a worrying undertone as he allowed the soil to crumble through his fingers.

‘Legend? What legend?’ Father brushed the last granules of dirt from his hands.

‘Perhaps I have said too much already. Your mother will have my hide if she learns I’ve been scaring you with these things.’

I tugged insistently at my father’s cuff as he turned to stride for home. ‘I’m not scared. And I promise I won’t tell mother.’

‘Very well,’ he sighed, then patting a slab of bulging root, he encouraged me to sit with him beneath the Witch Tree.

‘Have you ever heard the legend concerning the last chestnut.’

‘No. Never. Tell me.’

‘Up there. Do you see it?’ said Father, pointing to the top of the Witch Tree.

Try as I might, I could see nothing out of the ordinary amongst the curling brown fronds and the healthy crop of chestnuts hanging from its branches. I shrugged in defeat.

‘There, just beneath that jay. See it? The big one?’

And there it was. The highest in the tree. A monster of a chestnut. As large as the bird perched immediately above.

‘I see it!’

‘You’ll find it growing there every year without fail on that very same branch. Despite being substantially larger than all the others, it is always the last to fall. There is a legend that says this strange chestnut is imbued with a dark magic.’

‘What kind of dark magic?’

‘Witchcraft,’ said Father. ‘It is said that should any person catch the falling chestnut before it touches the ground, the ghost of Margaret McKay will appear and bestow the catcher with abnormal strength and longevity and grant their every wish and desire.’

‘Like money and gold. Or endless cake?’ I said, excitedly.

‘All the cake you could ever eat!’ he laughed. I stared unblinkingly at the tempting bauble, willing it to fall.

‘Have you ever tried to catch it?’

Father lowered his rueful gaze and idly swept a boot back and forth, brushing aside the carpet of leaves and twigs.

‘Oh, I have spent many a day sitting under this tree waiting for it to drop,’ he said. ‘As have many others over the centuries. Alas, no one has ever managed to catch it.’

‘Why don’t we climb up and pick it from the branch?’

My suggestion, which I thought a perfectly reasonable one, was received with a sour twist of Father’s lips.

‘Ah! Firstly, the legend insists the chestnut must fall of its own accord and not be plucked by an unworthy hand. Secondly, it is far too dangerous. To fall from that height is to fall to your death. I fancy the chestnut is like Excalibur waiting to deliver itself into the hands of one possessed of true virtue. And as your mother will readily attest, I am no King Arthur,’ he smiled. ‘Speaking of your mother, it is time we returned home before we risk a fate far graver than any witch’s curse.’

The Witch, the Seed and the Scalpel by Scott O’ Neill is published by McNidder and Grace, priced £9.99.

When a dilapidated distillery comes up for sale in rural Kintyre, Eilidh and her wife Morag jump at the chance. But their ambition to run the first women-owned whisky distillery in Scotland seems to be scuppered when a grisly, decades-old secret is revealed: two dead bodies have been stuffed into barrels, perfectly preserved in single malt. Enjoy this extract from The Malt Whisky Murders.

The Malt Whisky Murders

By Natalie Jayne Clark

Published by Polygon

Now, here I was, dressed in a beige sweater that wasn’t mine, in Campbeltown, nearly two decades later, with a beautiful wife, proudly bisexual, my very own whisky distillery, replete with a pair of decades-old corpses, with someone asking me questions on camera for the BBC.

‘You’re well known in Scottish whisky circles for your long-running, successful blog “Wisdom in Whisky” and the subsequent prize-nominated book of the same name. Can you tell us more about how that began? Please remember to mention the question in your answer this time.’

‘Yes. Well–’

‘And to look into the camera.’

‘Haha, this is why I have a blog, not a vlog.’ Heather didn’t laugh. I pulled the sleeves of the jumper over my hands and stretched my arms outwards, looking over to the purply water’s edge, as if taking it all in before I tried again.

‘I began my blog “Wisdom in Whisky” while I was still at uni, in Stirling, because it was my obsession at the time. I’d had a few before – just ask my old flatmates about my torrents of tangles of threads during my cross-stitching phase or the period where I didn’t leave my room because I was watching every single Jonestown documentary.’

Heather looked blank. Maybe she didn’t want to hear about that. I hate people who don’t show their thoughts on their faces. I can’t help but do it myself, so it doesn’t seem fair.

‘I tried my first whisky in a new pub that opened up in 2005, in Stirling. I was led through a tasting – a private tasting, essentially – and then I saw it in a whole new light. It was like magic, how something that before simply seemed to all be the same brown liquid now came to me as layers and layers of sensory experience and care. I think it was when I first learned about maturation that I was hooked. ‘The casks, the barrels, add so much depth to the liquid. I love that whatever they held before – sherry, bourbon, port, even whisky – influences the new-make whisky we put inside to mature. Not only that, the casks are toasted to break down the structure of the oak and sugars, and how lightly or heavily you toast the wood creates different flavours again. Some even say the type of soil in which the trees are grown affects the flavours. Distillers might take into account the rainfall of the area of provenance and how the wood was originally dried. That’s all without taking into consideration the size of cask you use, how many times it’s been used before, how long you leave your whisky in there, how many casks you move the whisky between, the weather as it matures and the geography of the area where it lies – even the way the logs were originally cut can affect the final product because of how the wood grain contacts the alcohol. And that’s just one element of the process of whisky creation.’

I was still getting zilch from Heather.

‘My blog though . . . you asked me about that. Essentially, I wasn’t going to my lectures, for a variety of reasons, and I started writing the posts for fun, instead of doing my essays. I was meant to be studying English, because that’s all I was really good at, except after one of the first seminars, your classic “death of the author” one, I became more interested in philosophy. If I’d been more proactive, maybe I might have changed subject and actually finished with a decent grade, but . . .’

I’d forgotten the question. Heather prompted me: ‘Yes, and tell us about the book and blog, please. How did that happen? How did you get noticed?’

‘I had thought it was funny to compare a whisky to a certain philosopher or their, like, policies? No – schools of thought. So, like, an Auchentoshan to Noam Chomsky, or a Glen Livet to Hannah Arendt. It sort of caught on – it was a different way of viewing both the whisky and the philosopher, I think. It grew from there, but the real growth was when I branched out from philosophers to writers and thinkers of any kind and when the comments sections in themselves began containing essays. That was a bit of a wild ride – I started getting invited to things. I got an offer from a publisher too. I had a year to write the book, but really most of it was written in the last month. Anyway, it was, I suppose, semi-successful, as successful as a book can be these days without being Richard Osman or whoever. I moved beyond the pub in Stirling and went to tastings and festivals elsewhere. Most of my student grant went on that, actually. That’s how I met Morag too.’ I looked about for Morag, for some assistance, a nod that confirmed I wasn’t wittering and I was making sense. But she was still dealing with the roofers, who had decided to start charging god knows how much just to survey the buildings before they even began work. I paused and glanced at my interviewer.

Heather was a few years younger than us, someone who seemed to have skipped the awkward, unsure years of her youth and zipped straight to the self-assured I-don’tsmile- for-anyone phase. Morag knew her quite well from her reporting days and told me multiple times how lovely she was and not to read anything into her dour facial expressions.

‘Thanks for that, Eilidh. I think we’ve got all we can outside for today. It’s bloody miserable.’

Like she could talk.

‘So how about we do some inside shots? All those barrels in the warehouse? You’ve not got much else to show for the cameras yet. Maybe find one with a historically significant year on it? How does that sound?’

Yesterday morning, when the roofer arrived early, very conscientious and aware of the awful windy and winding road down from Tarbet, we hadn’t yet put the bodies away. It was Bruno that saved us. Big dopey lovely Bruno. He basically took a running jump onto the man and crashed into him with such force he ended up on his back. Our dog is mostly well-trained, but sometimes he gets excited, and he hadn’t slept much. Neither had we. Morag had taken the roofer, Rodney, to recover with a cup of tea, far away from the warehouse. It had been up to me, alone, to cram these bodies back into their cask coffins, replace the fetid liquid and roll the barrels away.

The Malt Whisky Murders by Natalie Jayne Clark is published by Polygon, priced £9.99.

Water has always been a constant theme in Gordon Meade’s poetry, from his earliest memories of the West Sands at St Andrews, through the Northumberland coastline, via County Cork and the canals of Venice, to the beaches and harbours of the East Neuk of Fife. Here is a sample of poems from this beautiful collection.

Beyond the Ninth Wave

By Gordon Meade

Published by Into Books

Beyond the Ninth Wave

What are you given

to start with? A boat –

no oars, no sails, no rudder,

a knife, a flask of water.

Beyond the ninth wave

this is all you need.

Oars are useless;

your strength soon wanes.

Sails are useless;

there is no wind.

And a rudder is useless;

the horizon shows no land.

The water is useful;

all around you is salt.

And the knife is useful

to cut out useless thought.

Hooked

On fishing trips with my father,

I would stand behind him as he cast,

imagining the hook, on the back swing,

embed itself in my cheek and, with a flick

of my father’s wrist, burrow itself

even deeper in through folds of skin

into a bloodied mouth. I would

imagine the pain and the panic that

ensued, both of us fighting to get

the barb free, out through my flesh

and into the fresh river air. Of course,

none of this ever happened. I stood

well back, outside my father’s

reach, underneath a canopy of trees.

Like them, I stood there motionless,

never saying a word, the angler’s perfect

companion. And if I ever developed

into a serious thinker, which I doubt,

that is where it all began,

watching my father fishing in

the River Earn. Him, catching what

he had come for, salmon and trout,

and me, imagining the pain of being

caught, already hooked on thought.

A Sort of Homecoming

The sea is in

one of its strange moods,

forever threatening

to turn brown.

I would like to say

it is gun-metal grey but

it is more the colour

of a faded saddle-bag

like the ones I used

to see in Westerns. The tops

of the waves still manage

to keep their heads

above the water

from which they are

made. Pure white, the only

way they can escape

the general drabness

is by dashing themselves

against the rocks. Further out

there is no such luck.

They have to wait

until they have been

carried to the shore. Like so

many ships before

them, they will come

to realise that the biggest

danger lies when you are

closest to home.

Earthworms

for Geoff Wood

Earthworms, it seems, are made of tongues,

and are able to taste with every inch of their writhing

bodies. What a life of joy they must have,

and a life of horror, to not be able to turn off

life’s every passing flavour. I remember the ones

my father and I used to dig up in the back

garden as bait for our fishing trips. Could they,

I wonder, taste the cold steel of the spade, the shock

of the autumnal air, the heat of our fingers

as we lifted them from the earth, the plastic

of the bag in which we carried them to the river’s edge,

and then, their own blood as we impaled them

on the hooks, the chill of the fresh water, the mouth

of the fish as they were swallowed? What a life, and what

a death – all taste and savour – until the end.

Beyond the Ninth Wave by Gordon Meade is published by Into Books, priced £9.99.

Step back to the summer of 1978, where young Colin Quinn finds himself on South Uist with his charismatic uncle, Ruairidh Gillies in A Summer Like No Other by Martin MacIntyre, the English translation of his acclaimed Gaelic novel Samhradh ’78. Enjoy this extract with lovely nostalgic detail!

A Summer Like No Other

By Martin MacIntyre

Published by Luath Press

The moon suddenly broke through the murky sky and spilled through my back window. I had a look out, wondering too whether to have a last cup of tea and slice of toast – both from newish appliances – but the illumined fields held my attention. Their sepia wash conjured daytime vigour gone-by rather than today’s empty waiting evening.

Then a thud against the loose wooden frame threw me back a few feet. ‘What the…?’ My first thought was of a dead body unloaded and allowed to fall under my very nose, but the preceding silence pointed against this. A gormless, toothless, goat-grin pushed my humour more than it should have.

‘Thalla!’1 I screeched, lifting the windowpane. The billy darted backwards then forwards again, as if mimicking a dog. It wanted me to play – perhaps throw a ball like that poor woman’s collies. Unusual for Ruairidh to leave the gate open. My cool enquiries outside confirmed he hadn’t. The wily beast had slipped through a barbed gap in the fence. It did though exit through the gate. I made sure of that. But who kept goats in Eòrasdail?

While 1971, the year of my thirteenth birthday, will forever be linked to Creamola Foam – mostly orange – 1978 was the summer of lemon curd. I had tasted the stuff before, but it wasn’t something my mother ever purchased. Ruairidh had got it in for me on Ealasaid’s recommendation. This surprised me a little, as the homemade jams at Duns had been so varied and plentiful; but, of course, while much lauded by Ruairidh, these really had been the ‘preserve’ of Aunt Emily.

I remember laughing at this unexpected, unintentional, pun and wondered if I might slip it casually into conversation with my uncle. Given our earlier encounter with Jane MacDonald, perhaps it was better I didn’t prod memories of his late wife’s prowess, or risk offending him, when I was greatly enjoying lathering my toast with Co-op bought goo.

A bit strange, I thought back in the sitting room, that someone as able as Emily never returned to work after she’d had Iona, the elder of my cousins. Had running everything connected to hearth and home provided as much satisfaction as a busy hospital job? Neither daughter had chosen medicine. I wondered whether this was a consequence of their mother’s decision or more from having lived with Ruairidh.

In the living room, I’d stretched up to turn on the radio for the headlines when the front porch door opened. While swivelling the aerial, I learnt that a previous despot’s life had just been ‘ended’ in Comoros. Where exactly was this troubled country, I wondered, as muffled sounds slunk through Taigh Eòrasdail’s passageway?

And what might be the impact of the other news: that Labour, and not the SNP, would now represent Hamilton in Parliament – even though the bi-election was brought forward to accommodate the World Cup? No, none of my uncle’s usual brisk movements or a hummed or whistled tune were in evidence.

The programme finished, the pips played out in full signalling 11.00pm, and we were well beyond Rockall in the Shipping Forecast, before I heard a hand on the opposite side of the door. At first it failed to open – that worn brass handle could slide a little, even without the help of errant butter or lemon curd.

‘Ruairidh?’ I shouted, leaping to release the latch from my side. My uncle half-stumbled, half-fell, through, still in his coat and hat. Tears filled his normally lively, now-dulled, eyes.

‘He was almost gone, Colin.’

‘Alasdair mac Sheumais Bhig? O dear…’

‘No! Stuff him and his poisoned-dwarf minder. The wee fellow. Anna Morrison’s new baby.’

Ruairidh suspected a near cot death, the child being blue when his frantic father ran into Daliburgh Hospital at 9.00pm. He had fed well, exclusively on the breast – despite the pressures – and had shown no change in character all that day. Plenty wet nappies. No unusual or prolonged crying. No signs of a cold or fever. Nothing. Anna had placed him on his tummy like all his brothers and he’d slept contentedly without a fight.

‘They’ll have to do further tests in Glasgow’s Yorkhill, look for some sort of underlying condition. Having a child die on you is horrible, a Chailein!’ My uncle’s last sentence in Gaelic: mìchiatach, the descriptor. ‘By the grace of God, or some sixth sense, I popped in on my way home from an old dear in Kenneth Drive. Of course, Eric Adams rushed down and stayed. His wife arrived later with soup and a new shawl, a lovely gesture. The family were in total shock. You still on the lemon curd? Well done, a laochain.’2

How might it have been for Uncle Ruairidh, I considered, while tossing and turning on the pillow, to have come back to an empty house after such an incident, especially if the baby had died? To sit there where I had been sitting – a widower alone with his mortality and the bleak unyielding rhythm of the Shipping Forecast? Ruairidh needed me now, no matter what happened with the bold Jane. He might though ban me from trying.

My late dream that night contained the image of a young footballer in a blue top, ceaselessly scoring the same goal, but on turning to receive adulation from his fellow players is reminded that he is dead. ‘Tha sibh michiatach!’3 he screams and tries again.

- Scram!

- lad

- 3. You’re all horrible!

A Summer Like No Other by Martin MacIntyre is published by Luath Press, priced £10.99.

Scotland is known for its three languages, and though most of our books are published in Standard English, we have a rich list of books written in Scots and in Gaelic. As we like to highlight the best in new releases, here are some Scots and Gaelic books published in the first half of this year.

The Moggie Thit Meowed Too Much

The Moggie Thit Meowed Too Much

by Emma Grae

The Moggie Thit Meowed Too Much by Emma Grae, illustrated by Bob Dewar, is a beautifully written Scottish children’s book that sensitively tackles the theme of loss. Set in the vibrant world of the Scots language, this story follows young Skye as she cares for her granny’s beloved cat, Puffin, after her granny passes away.

This book is perfect for children aged 4-8 who are coping with loss, as well as for families wanting to introduce Scots language in an accessible, heartfelt way.

The Lass & The Quine

The Lass & The Quine

By Ashley Douglas

The Lass & The Quine is the first original LGBT+ inclusive children’s book published in the Scots language. An illustrated storybook for children of primary school age based on the poem ‘The Lass and The Quine’ by Ashley Douglas. It is a new Scots fairy tale that challenges those you know in a clever and enjoyable way. The story concerns ‘a lass and a quine whae are awfie different in ivery wey, but whae faw heid ower heels in luve – meetin a wheen animals o the forest alang the wey!’ It has a timeless feel, but what makes it so special is that the love story is one between a girl and a princess, not a girl and a prince.

‘An absolutely smashin story frae an absolutely stoatin scriever’ – Thomas Clark award-winning children’s author, Peppa’s Bonnie Unicorn and Diary o a Wimpy Wean

Tongue Stramash: Poems in Scots

Tongue Stramash: Poems in Scots

By David Bleiman

David Bleiman, a regular of the Edinburgh Stanza Group, is bringing out his first collection, Tongue Stramash, a book of poems in Scots. He lives in Edinburgh, writing poetry in English, Scots and a little Spanish and Yiddish. He particularly enjoys writing multilingual poetry, including a part-excavated, largely reimagined dialect of Scots-Yiddish.

‘Sich a braw wheen o poyums, David Bleiman’s Tongue Stramash left me a little bit breathless and giddy, heart-wrung and laughing out loud. His sheer delight in the Scots language is evident in every brilliant verse. He explores loss, language, history, place and is not afraid to take on the greats such as Burns and Fergusson. The mixter maxter of Scots and Yiddish in some of his poems further adds to the richness of the collection. This is a book to be relished – a welcome addition to contemporary Scots poetry.’ – Lynn Valentine, poet

An Tìgear a Thàinig Gu Dinneir

By Judith Kerr; translated by Gillebrìde Mac ’IlleMhaoil

The doorbell rang just as Sophie and her mummy were sitting down to tea…

A beloved magical story of tigers, tea and ice cream.

A multi-million selling picture book no childhood should be without.

New Gaelic translation of Judith Kerr’s children’s classic The Tiger Who Came to Tea

‘Beloved by millions. And rightly so.’ – Daily Express

Paddington agus Iongantas na Nollaige

Paddington agus Iongantas na Nollaige

By Michael Bond; translated by Gillebrìde Mac ’IlleMhaoil

When the Browns take Paddington to the Christmas Grotto in a grand London department store, his journey

through the Winter Wonderland is full of surprises.

But the best surprise is from Santa. After all, who else could find the perfect present for a bear like Paddington.

‘I’ve always had great respect for Paddington… He’s a British Institution.’ – Stephen Fry

‘It’s always great when a book is translated into Gaelic that the children would be familiar with.’ – Head Teacher, Gaelic Medium Primary, Highland Council

A’ Hobat (The Hobbit)

A’ Hobat (The Hobbit)

By J. R. R. Tokien; translated by Moray Watson

The beloved fantasy classic for readers of all ages, about a hobbit called Bilbo Baggins who is whisked off on an unexpected journey by Gandalf the wizard and a company of thirteen dwarves. The Hobbit is a tale of high adventure, undertaken by a company of dwarves in search of dragon-guarded gold. A reluctant partner in this perilous quest is Bilbo Baggins, a comfort-loving unambitious hobbit, who surprises even himself by his resourcefulness and skill as a burglar. Encounters with trolls, goblins, dwarves, elves and giant spiders, conversations with the dragon, Smaug, and a rather unwilling presence at the Battle of Five Armies are just some of the adventures that befall Bilbo. Bilbo Baggins has taken his place among the ranks of the immortals of children’s fiction.

Written by Professor Tolkien for his own children, The Hobbit met with instant critical acclaim when published. Now the book is available for the first time in Gaelic, in a superb translation by Professor Moray Watson. The book includes all the drawings and maps by the author.

Draoidh Drùidhteach Oz (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz)

Draoidh Drùidhteach Oz (The Wonderful Wizard of Oz)

By L. Frank Baum; translated by Sgàire Uallas

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is L. Frank Baum’s story of a little girl named Dorothy, who with her dog Toto is carried by a tornado from Kansas to the strange and beautiful land of Oz. Here she decides to visit the Emerald City to ask its ruler, a wizard called Oz, to send her back home again. On the way she meets a Scarecrow, who is in search of brains; a Tin Woodman, who wishes to have a heart; and a Cowardly Lion, whose one desire is to possess courage. The little party encounter many dangers and marvelous adventures on the way, but reach the Emerald City in safety, their success being due to the thoughtfulness of the Scarecrow, the tender care of the Tin Woodman, and the fearlessness of the Cowardly Lion. This is the book that inspired the famous 1939 film — which differs from the original book in quite a few ways!

Bha Siud ann Reimhid

Bha Siud ann Reimhid

Edited by Lisa Storey

Newly updated, 21st Century edition of classic 1975 Scottish Gaelic folklore collection. Aimed at both adults and children. Nine Scottish Gaelic tales compiled and presented by Lisa Storey. Acclaimed broadcaster Angela MacEachen (author of new introduction to the 2025 publication) says:

‘Bringing up a Gaelic-speaking family in Edinburgh, if there is one book which ensured intergenerational transmission – passing Gaelic on to my children, and now my grandchildren – I can confidently say that it is, most certainly, this one. Never tiring of these marvellous traditional tales – for all ages – and their natural idiom and turn of phrase, publishing an updated version of this collection means that we can continue to enjoy these stories for years to come.’

Ailig agus an Dalek Gàidhlig

Ailig agus an Dalek Gàidhlig

By Shelagh Chaimbeul

Ailig is an 8-year-old boy who loves Dr Who. When his teacher arranges a Halloween party in school, Ailig knows that he wants to dress up as a Dalek. There’s only one problem though – his teacher says that the children must dress up as characters who speak Gaelic. Ailig’s mum offers to make him a Spàgan costume (Spàgan is the Gaelic translation of the ‘Monster’ books) but he is determined to go as a Dalek. They reach a compromise – if Ailig can find a Gaelic word for ‘Exterminate’ his mum will let him go to the party as a Dalek.

Moilidh agus Doilidh

Moilidh agus Doilidh

By Maoilios Caimbeul

Join Moilidh, an orphan lamb, and Doilidh, a wise sheep and keeper of ancient tales, as they journey through a landscape interwoven with the heavy history of the Highland Clearances. As the sheep travel through Sutherland, the Isle of Skye and the Hebrides, Doilidh tells the stories passed on to her by her ancestors.

Iomall

Iomall

By Alistair Paul

Iomall is a collection of science-fiction short stories. With tales of other wordly creatures and people trapped in time, these stories dwell on the peculiar, taking readers on a journey out of time and space.

An Staran: Rosg Gàidhlig le Ruaraidh MacThòmais

An Staran: Rosg Gàidhlig le Ruaraidh MacThòmais

Edited by Dr Petra Poncarová

This book comprises a selection of the Gaelic prose writings of Prof Derick Thomson (1921 – 2012). As well as being one of the most important Gaelic poets of the 20th century, Thomson, as the publisher and editor of the quarterly ‘Gairm’, shaped the development of Gaelic writing in the post-war period.

As an anthology of short stories, essays, reviews, travelogues and other genres of writing, the book aims to showcase lesser known aspects of Thomson as a writer – for example his skilful use of language, sharp intellect, his commitment to Gaelic and to Scotland and his incisive wit. There is also a short biographical introduction to Thomson.

The compiler and editor of the collection, Dr Petra Johana Poncarová, is an academic writer and researcher whose focus is on Scottish Literature and Culture, including modern writing in Gaelic.

Arnol Blackhouse: Official Souvenir Guide

Arnol Blackhouse: Official Souvenir Guide

By Historic Scotland

This dual-language guide explores the rich history of the atmospheric Arnol Blackhouse and township on the Isle of Lewis – a history which reaches back over 2,000 years. The houses that we see today tell the story of life in the Western Isles over the last few centuries.

With side-by-side text in Gaelic and English, this new book allows people to explore this remarkable place, the importance of Gaelic culture and language, and to find out what we can learn from the traditions of the past in shaping a sustainable future.

We’re very much looking forward to visiting the National Galleries of Scotland’s exhibition on James VI & I at the Portrait Gallery opening in late April. And we’re here to give you a wee preview not only of the exhibition, but of the excellent book that accompanies it.

Art & Court of James VI & I

By Kate Anderson, with Catriona Murray, Jemma Field, Anna Groundwater, Karen Hearn and Liz Louis

Published by National Galleries Scotland

History has not been kind to james vi of Scotland and I of England and Ireland. For many, he has fallen between the cracks of the reigns of his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, and his son Charles I, overshadowed by their contentious and heavily romanticised legacies. Both James’s reign and character were heavily criticised in the seventeenth century by writers, notably Sir Anthony Weldon. Published posthumously in 1650, the pejorative account of James’s physical appearance claimed that the king’s tongue was too big for his mouth, that he possessed weak legs and constantly fidgeted with his codpiece.1 Weldon was a former English courtier who had been dismissed from his position, and the memoir was anti-Scottish in sentiment and full of scandal and unfounded rumour. However, its legacy continued to impact on subsequent histories of the king for centuries. While recent scholarship has revised some of these inaccuracies and prejudices, misconceptions about James and his reign still exist. One of the aims of this book, and the exhibition it accompanies, is to reframe James and consider his life and reign in a wider context; they also seek to explore the extraordinary art, objects and culture that were produced during this period, and demonstrate how James, his family and members of the court used them to promote messages of status, power and allegiance.

This is not a detailed biography of James. His reign and character are incredibly complex, and while the narrative here is multi-layered, it does not set out to comprehensively examine the historical context of Scotland, England and Europe during this time. Instead, an object-based approach has been taken, with the visual and material culture of the Jacobean period being placed at the centre of this study, alongside an overview of some of the key individuals and events that shaped the king. In an attempt to address the imbalance of scholarly attention that the Scottish and English courts have received over the years, a concerted effort has been made to highlight James’s Scottish period. However, it is too simplistic to directly compare the artistic quality and output of the two courts, as the political, religious and economic climate in Scotland during James’s early life had a major impact on the development of the country’s cultural productivity.

This book has been published to accompany the exhibition The World of King James VI and I. It is hoped, however, that the essays and catalogue will have a legacy beyond the exhibition. Many of the artworks and objects in the exhibition are published here for the first time.

Spread from Art & Court of James VI & I showing: Left: Unknown artist Double Portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots and James VI, 1580s Collection at Blair Castle, Perthshire Right: Unknown artist Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587), 1610–15, after an original of 1578 National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh (PG 1073)

Attributed to John de Critz the Elder (c.1550–1642) James VI & I, 1604 National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh (PG 561)

John de Critz the Elder or workshop of John de Critz the Elder (c.1550–1642) Anna of Denmark, c.1605 National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh (PG 3800)

Art & Court of James VI & I by Kate Anderson, with Catriona Murray, Jemma Field, Anna Groundwater, Karen Hearn and Liz Louis, is published by National Galleries Scotland, priced £24.99.

Karen Campbell continues to write fantastic novels full of heart, of people and places that deserve their stories told. David Robinson is impressed by This Bright Life‘s humanity and insightfulness.

This Bright Life

By Karen Campbell

Published by Canongate

Nearly 40 years ago, the Guardian newspaper ran a TV ad that impressed me so much that I can still remember it. A skinhead is shown running towards a businessman with a briefcase. From one angle, it looks as though he is about to mug him. A wider angle shows a hoisted palette of bricks about to spill on top of the businessman’s head. Far from being a mugger, in other words, the skinhead is a potential lifesaver. ‘It’s only when you get the whole picture,’ the voiceover concludes, ‘that you can see what’s going on.’

I couldn’t help thinking of this while reading Karen Campbell’s new novel, This Bright Life. It too has a mugging at its heart – a real one this time – and two central characters even more different than a skinhead and a businessman. It too demands that we see the whole picture, and it too adds to our comprehension.

The novel begins inside the head of Gerard, a 12-year-old boy. He’s on his bike, freewheeling down Whitehill Street in Glasgow’s Dennistoun. His brain is freewheeling too. It’s not even the summer holidays, but already he’s thinking about his senior school, which of his friends will be going there and which won’t, wondering which nicknames he’ll shed and which he’ll probably get stuck with. His bantering mates in the Broncos (‘a gang named after a horse will get your head panned in at secondary’) are off up to Celtic Park but Gerard heads home because it’s lunchtime, so his mum will probably be up by now.

Those two opening pages are a mini-masterclass in writing character. Drenched with empathy they may be, but there’s a precision about them too. Those nicknames, that matey banter, those drifting thoughts about the future – each carefully triangulates what kind of person Gerard is. That’s a hard enough challenge, but Campbell adds to it. Because despite all his mates’ teasing, she also makes us realise that there is something seriously wrong with him. As he heads downhill to his home in a squalid flat in Duke Street, Gerard wonders what it would be like to pedal downhill as fast as he can into the traffic, keeping his eyes firmly shut all the time.

But Campbell hasn’t finished getting inside people’s heads, and straight away she takes us behind the eyes of an 82-year-old widow. Margaret lives in a ground floor flat opposite the Buffalo Bill statue (Gerard and the Broncos have just visited it) in the home she shared with her husband Bert for six decades before his death the previous year. Within another half a dozen pages her unobtrusive, secluded life is just as firmly delineated as young Gerard’s vibrant, ragged, edgy one.

Now for the bigger picture. The home Gerard returns to is hellish. His junkie mother is out for the count, his screaming baby sister has a dirty nappy, and his seven-year-old brother is desperate for food. There’s none in the flat, and nothing to buy it with in his mother’s purse. There’s only one thing he can think of to do, and so goes out onto the street, and is wondering how he’ll be able to rob the local greengrocer’s till when he spots an old lady – Margaret of course – with a purse sticking out of her handbag. As he grabs it, Margaret turns and falls badly on the pavement. She is seriously injured. Gerard runs off home.

At this point, Campbell introduces her third main character. Claire is a solicitor in her thirties going through the double traumas of divorce and moving house when she witnesses the mugging and rushes over to help the pensioner, who seems to be choking. She removes the old lady’s dentures, and puts them in her pocket. An ambulance arrives and rushes the pensioner off to hospital. Five minutes later, Claire spots the young mugger in the street and phones the police. They arrest him. The pensioner, he is told, has been very badly hurt indeed. If she dies, the police warn him, he could be facing a charge of culpable homicide. Meanwhile Claire puts her hand in her pocket and finds the dentures she forgot to hand over to the ambulance crew.

Three characters, three completely different stories, and yet Campbell manages to bring each fully to life. They also change in entirely credible ways: returning from hospital, Margaret’s infirmity nudges her towards depression and resentment at having to rely on her neighbours. Claire begins to overcome her habit of overthinking and gradually becomes more at peace with herself. Both also have their own secrets which are gradually revealed. But the novel’s focus remains firmly on Gerard. When we see the whole picture – the junkie mum, the drugs, the crime, the unremitting poverty, all on top of the fact that he cannot read or write – is there any realistic chance of redemption? And just suppose there is, how can you write that story without it sounding, er, like an ad for the Guardian?

Discussing homelessness – the main theme of her last novel, Paper Cup – Campbell recalled how ‘profoundly disturbing’ she found it in the five years in her twenties in which she served as a Glasgow policewoman to encounter ‘a netherworld of people with nothing and nowhere to go’ in the middle of a bustling city. I can’t help wondering whether she met young lads like Gerard too; certainly the Child Protection Hearing feels perfectly authentic (‘Remember, this is about conversation, not confrontation’), not least in the befuddlement they create in Gerard’s mind. Here he is, unable to read but in a world of acronyms, an ACE child (Adverse Childhood Experience) on an ICSO (Interim Compulsory Supervision Order) before his first session with the CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Team) psychologist.

Try as all these adults might, they can’t untangle the confusion Gerard feels. When the psychologist asks him to look at where his feelings come from, he knows he is lost. ‘Normal folk don’t need to pull feelings out their heads and ask them what they’re doing there’ he thinks to himself. But even in a (mercifully, for once, unsatirised) middle-class foster home, that feeling of lostness doesn’t go away: how can it when he is separated from his siblings, unsure when he’ll see them next or when he’ll be told he’ll have to move on. No wonder he longs for his mother – the one fixed point in his life, no matter how much he knows he can’t rely on her – even when it looks like she might be asking him to break the law…

With so many things against him, the outlook for Gerard might appear to be grim. But this is a novel of hope. There is, it reminds us, such a thing as society, and it’s there in the quiet humanity of the volunteers who take kids like him guerrilla gardening or on trips to city farms, or in the kindness of a Glasgow waitress who puts a cake next to a crying woman customer (‘There you go hen, it’s on the house’) or foster parents who homeschool their charges and pick up on what they’ve not understood about reading and writing. This Bright Life is written with empathy, humour and precision and reminds us just what an enjoyable, thought-provoking, whole-picture novelist Karen Campbell can be.

This Bright Life by Karen Campbell is published by Canongate, priced £16.99.

Art Deco Scotland by Bruce Peter is the latest release from Historic Environment Scotland showcasing Scotland’s place within this artistic moment in building, transport and interior design. It’s a fascinating book full of fantastic images, and we’d like to share some with your now.

Art Deco Scotland

By Bruce Peter

Published by Historic Environment Scotland

Russell Institute, Paisley

James Steel Maitland of Abercrombie and Maitland, 1927

Bruce Peter

Dick Place, Edinburgh

William Kininmonth, 1933

Courtesy of Thelma Ewing (top); Bruce Peter (bottom left); Bruce Peter Collection (bottom right)

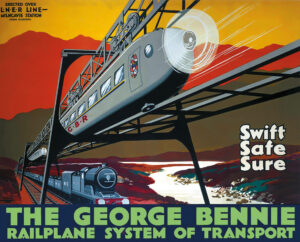

Bennie Railplane Poster

WCN, McCorquodale & Co, 1930

Bruce Peter Collection

Fountainbridge Library, Edinburgh

John Alexander William Grant, 1940

Bruce Peter

Top image

South Cascade, Tower of Empire & Garden Club, Empire Exhibition

Thomas S Tait of Sir John Burnet Tait & Lorne and Launcelot Ross, 1938

Bottom image

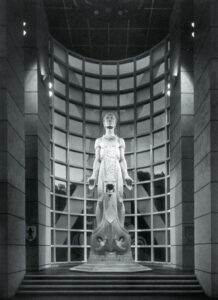

Statue of St Andrew in the Scotland (South) Pavilion, Empire Exhibition

Archibald Dawson, 1938

Courtesy of Ian Johnston

The Regal, Bathgate

Andrew D Haxton, 1938

Bruce Peter

Former Bereseford Hotel, Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow

William Beresford Inglis of Weddell & Inglis, 1938

Bruce Peter

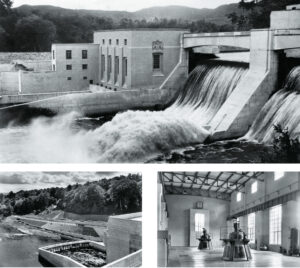

Pitlochry Dam and Power Station, Pitlochry

James Williamson & Partners and Harold Ogle Tarbolton, 1950

Bruce Peter Collection (top); HES SC914038 (bottom left); HES SC914023 (bottom right)

Top image

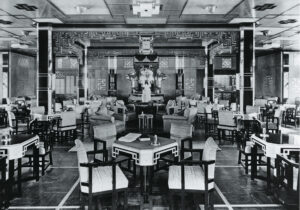

First Class Mall, Empress of Britain

Percy Angelo Staynes, Albert Henry Jones and Maurice Grieffenhagen, 1931

Bottom image

Cathay Lounge, Empress of Britain

Edmund Dulac, 1931

Bruce Peter Collection

Nardini’s, Greenock Road, Largs

Charles James Davidson and George Veitch Davidson, 1935 (renovated in 2008)

Bruce Peter

Art Deco Scotland by Bruce Peter is published by Historic Environment Scotland, priced £30.00

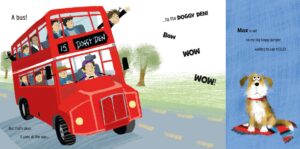

Little Door’s picture books are always charming and colourful with heartwarming stories and brilliant illustrations. Their latest release, My Dog Max, celebrates all things canine and we hope you love these sample spreads as much as we do!

My Dog Max

By Alan Dapré, illustrated by Alex Ayliffe

Published by Little Door Books

My Dog Max, by Alan Dapré, and illustrated by Alex Ayliffe, is published by Little Door Books, priced £7.99.

David Robinson is impressed with Richard Strachan’s debut novel, The Unrecovered, a gothic literary thriller that keeps readers guessing.

The Unrecovered

By Richard Strachan

Published by Raven Books

It’s March 1918, and in Flanders, the Germans are breaking through British lines. Within a week or so, the casualties will arrive at Ruttinglaw House, a mansion near South Queensferry converted into a military hospital. Volunteer nurse Esther Worrell, widowed at the start of the war, will be among those taking care of them.

One of the patients is a local man, Captain McQuarrie. ‘Our first from the Palestinian front,’ the Medical Officer tells Esther as she follows him on his rounds. Bayonet wound, says the note on the bedstead, though the bandaged hole in his chest seems a bit too wide for that. She fills the glass of water by his bedside and they move on.

Already, though, I’ve cheated, the way all reviewers cheat. It’s in the nature of the job: we’re looking back, re-viewing, and inevitably concentrating on the characters who will figure later on. But at the start of The Unrecovered, Richard Strachan tells us so much more: not just about Esther, but the hopes and fears of her nursing colleagues; not just about Captain McQuarrie but gossipy case notes on all the other wounded soldiers on the morning round; not just about the makeshift hospital but also about the half-ruined castle across the fields the medical officer wants to requisition to cope with imminent flood of casualties. Comprehensively imagined and carefully described, this is a convincing piece of stage-setting.

Gallondean, the gothic pile across the fields from the hospital, is the kind of place you might expect to find in a supernatural horror novel, all crumbling masonry, rotting carpets, damp wooden floors, and secret chambers with their own grim mythologies. Its grounds are similarly cursed, not least the rocky outcrop on the nearby coast called Hound Point. Centuries ago, at the exact moment when the laird of Gallondean died, his faithful dog was said to have howled in mourning – even though his master was many miles away at the time, and this happens whenever any subsequent laird dies. Preposterous, you might think – except that you’ll find a version of this story in every guide book you’ll ever read about Hound Point, the very real headland on the Dalmeny Estate a mile east of the Forth Bridge.

Jacob Beresford is the new laird of Gallondean, and he has just arrived from India to take ownership. The nurses at neighbouring Ruttinglaw can’t work out whether he reminds them more of Dracula or Heathcliff, but the medical officer knows a tubercular patient when he sees one. More than his health, though, Jacob is obsessed with getting to the bottom of that centuries-old legend about a tyrannical owner of the castle whose son went on a Crusade to the Holy Land after his death. There’s a statue of this knight – and his faithful dog – in the hospital grounds, though when one of the nurses sleepwalks past it, it doesn’t seem to be there any more.

Sorry: I’ve done it again. Because that was just a silly dream one of Esther’s colleagues mentioned to her, wasn’t it? Just a bit of chitchat between the nurses as they went about the far more important task of looking after their patients, feeding the man who had come back from the front without any hands, talking about the production of Peter Pan that the wounded troops are planning to put on to raise their morale, or about the snared animals whose mutilated bodies the gamekeepers (presumably) have left in the nearby woods. Yet as readers, we’re always trying to guess the path the novelist is taking us on, and the dream-disappeared statue makes us suspicious. A red flag, surely?

Except that in The Unrecovered these coincidences, false trails, and people who remind the main characters of others who know secrets about them, positively abound. So many, in fact, that they’re not red flags at all. Yet if a red flag is something that stops you reading, what we have here is the opposite: an encouragement to read on, if only to find out which clues turn out to be true and which ones false.

I can’t say much more without spoilers, but I will mention a key fact – one I’d completely forgotten – that is grounded in history just as surely as the novel’s Hound Point (and come to that, Mons Hill) are grounded in West Lothian’s geography. When Jerusalem fell to General Allenby’s British-led troops in December 1917, he became the first Christian for centuries to control the city. Does that help you join any plot dots? Can you work out what was likely to have caused that wound in Captain McQuarrie’s chest?

(Don’t worry: neither could I.)

But I’ve kept the most important thing about Richard Strachan’s writing to the end. There are plenty of writers who write competently about horror and the supernatural but who lack the descriptive skill to animate everyday reality or handle their characters’ psychological complexity. Strachan can do both.

I’ll give you an example. When we are first introduced to Esther, we know that she is married, but little more. Carefully, Strachan drip-feeds key facts about her: we learn, for example, that she is a would-be poet and is passionate about Browning, whom she defends against McQuarrie’s accusations that he is both old-fashioned and obscure. ‘It’s just that he lets his information unfold more gradually,’ she says, but that’s true of Strachan’s portrait of her too: she’s not just married, but widowed; not just recently, but early in the war, when his ship was sunk. Her honeymoon was in Florence in July 1914, and naturally she wanted to see Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s tomb in the English Cemetery there, but her husband wasn’t bothered and didn’t even attempt to hide his boredom and frustration. It was a hot summer’s day and he was forever complaining about how far away the cemetery was, and insisted on having a glass of wine at each cafe they passed. There were a lot of cafes….

You’d expect to find a scene like this – pivotal to the heavily literary and somewhat over-ornate plot, as it happens – in, say, a short story by William Trevor or Bernard MacLaverty rather than genre fiction. But Strachan’s talents for descriptive writing are equally evident even when – as in a superlative scene set in the hills of Judea at the end of the book – he is handling an all-out action sequence. Like Iain Sinclair, who calls this ‘a formidable and deeply crafted nightmare,’ I was hugely impressed.

I live in the same city (Edinburgh) as Strachan but hadn’t heard of him before, though a quick internet search reveals that he is a former bookseller and has already penned several novels for Games Workshop’s Black Library imprint. For none of these, though, has he had a book launch although he has just had one for this, his literary debut. And as debuts go, it’s a very assured one indeed.

The Unrecovered by Richard Strachan is published by Raven Books, priced £16.99

David F. Ross’s new novel, The Weekenders, takes us to the underbelly of 1960s West of Scotland where who you know determines how much you can get away with, including murder. With his trademark black humour and sharp dialogue, it’s another brilliant slice of Glasgow life that delves deeper and darker into the city and its past. In this extract, we are introduced to Stevie ‘Minto’ Milloy, footballer turned journalist.

The Weekenders

By David F. Ross

Published by Orenda Books

Nervous initially, Stevie Milloy relaxes a little when he smells the newsroom. He has missed the dressing-room stench of alpha-male body odour. But it’s present here, and it’s comforting to him. He sniffs it all in, the stinking socks and putrid farts. The hair tonic and Brut 55. The cigarette smoke and alcohol stench. And, bizarrely, the Algipan. For the lumbago, most likely.

Introductions over. The odd handshake. Nods from some. A squad of fifteen here. Almost obscured by the fog of fag smoke. Everyone stooped and out of shape, and looking a decade older than they probably are. He sees monochrome tones. Frayed, off-white shirts. Trussed-up ties. Regulation short back and sides. Cheapside Street formality. In comparison he’s a peacock.

For half an hour there is an impromptu press conference with his new teammates:

‘Ye ever kick a baw these days, Stevie?’

‘Wis it sair when the leg went, Stevie?’

‘Did that cunt Geordie McCracken ever say sorry, Stevie?’

‘How much wid ye have been on at Stamford Bridge, Stevie?’

‘Who d’ye think’ll win the World Cup, Stevie?’

‘How the fuck did ye end up here, Minto?’

The last one was a question he has been asking himself since waking up in the Victoria, left leg in plaster from ankle to thigh.

He should have moved to England the previous season. Everybody said so. But he stayed. Because Denice didn’t want to go. London was so far away, she’d said. He stayed at Thistle. Turned down Chelsea. Turned down the chance to play with Ron Harris, John Hollis, Eddie McCreadie. Buying his clothes from King’s Road boutiques. Drinking in Soho pubs alongside The Beatles and The Stones. He decided to wait until Denice was ready. And while he waited, she was warming the bed of two of his international teammates.

After the injury, the Chelsea deal was off, naturally. Thistle stood by him. But he knew it was over the minute he looked down at his snapped leg. You don’t come back from a compound fracture like that. A rapid descent. No fans standing him a drink anymore. No handshakes at the players’ entrance. No requests for autographs. Not even the baiting from rival supporters. Just pitied looks and weary shakes of the head. Nowhere to go except the boozer. And the bookies.

Then the money ran out.

Luckily, he pulled out of the tailspin just in time. Took old Alf’s advice and joined a local library. Found the days disappearing. But in a good way. Time spent in the stimulating company of George Orwell. D.H. Lawrence. Barry Hines. Colin MacInnes. Time spent being inspired by words. Sentences. Paragraphs. Chapters. Fiction. Non-fiction. Values. Ideology. Social justice. Reconnecting with an education he had left behind. Spirits lifted instead of lifting spirits.

His was a life of two halves.

The whistle sounds.

The second half begins.

‘Milloy!’ A howitzer voice. A six-letter shell. Cascading off the walls. Even though its owner isn’t in the room. It puts a stop to the questions from the assembled hacks.

Stevie follows the reverberation to its source: a small office off the press room.

‘Jesus Christ, whit the blazes are you wearin’?’ asks Gerry Keegan as Stevie enters. Keegan runs the press room.

‘Casual, boss,’ says Stevie.

They size each other up. Both wondering if the other will be too much trouble for the wages.

Keegan shakes his head. ‘Ye done much writin’ before?’

‘No’ really, Mr Keegan. Notes in the Thistle programmes, that sorta thing. But ah’m a quick learner.’

‘That right?’

‘Ah’ve still got the contacts, an’ obviously ah’ve played the game.’

‘Mibbe so. Playin’ fitba an’ writin’ aboot it, they’re worlds apart.’

‘Did ye see me play, Mr Keegan? Mibbe the Scotland games?’

‘Look, Milloy, ye’re here cos some high heid yin oan the top floor vouched for ye. No’ ma idea, obviously, but ah’m nothin’ if no’ fair-minded.’

‘Ah understand that, Mr Keegan.’

‘That’s ma squad oot there. They might no’ be up for a Nobel Prize for Literature but they put a decent shift in. They know how tae get the job done. Tae cut corners. Tae file copy oan time. Tae work tae The Man’s plan. Ah trust every single yin ae them.’

‘They look like a decent bunch, Mr Keegan.’

‘Trust has tae be earned, Milloy.’

‘Totally agree, Mr Keegan.’

‘Havin’ an ability tae kick a baw willnae make ye a sportswriter.’

‘Aye, ye said.’

‘Aye. Ah did.’

‘Well, proof’s in the puddin’, Mr Keegan.’

‘The proof’s in the eatin’, son. If yer gonnae use expressions, use them right.’

‘Appreciate the tip, Mr Keegan.’

‘Aye. Right. Well. Then.’ Gerry Keegan sits. ‘Noo’ that we’ve got that oot the way, ye’re goin’ tae Ayrshire on Thursday. The Brazilians are there. Get some exclusives. How’s Pele feelin’ about their chances? Who’s starting against Bulgaria. Who’s injured? That sorta thing. Elsie’s got yer pass, an’ ye can take one ae the motors.’

‘Great,’ says Stevie.

‘An’ then, if ye dinnae fuck that up, ye’re shadowin’ Meikle for the rest ae the month. Got it?’

‘Aw’right, Mr Kee — ’

‘An’ drap aw that “Mr Keegan” stuff, right? It’s “boss”, or “gaffer”.’

‘Got ye, gaffer!’ says Stevie. ‘Oh an’, gaffer … ’

‘Whit?’

‘You can call me “Minto”.’

Gerry Keegan’s hardman exterior crumples. He rubs his chin. He sniggers. ‘Aye. Right.’

Stevie Milloy smiles. He winks at his new manager.

He is back in the first team.

Inside left.

Socks rolled down.

The baw at his feet.

Goal gaping.

The Weekenders by David F. Ross is published by Orenda Books, priced £9.99.

This is What You Get is the story of a group of young men who enlist in the army in the 1980s as their only escape from Thatcher’s Britain. We follow them on tours of Germany and the first Gulf War, and explore themes of duty, loyalty, betrayal and shifting morals. We hope you enjoy this extract.

This is What You Get

By Iain McLachlain

Published by Rymour Books

Ye had tae learn tae anticipate fit wis expected o ye. Some boys were ready for it straight awa. Livin in poverty, bein brought up by strict parents or haein tae work fae a young age helped ye. Maist o the boys that were recruited in the eighties grew up in Thatcher’s wasteland so they were nae strangers tae hardship or lack o opportunity.

If ye could get along an keep yer mooth shut an manage tae bide oot the line o fire ye could remain unnoticed. If yer were slow tae adjust tae yer new life ye were noticed for the wrong reasons an ye’d get punished. Some boys thought they knew the script, but it wisna initiative they were lookin for, they were lookin for obedience. They did look for leadership qualities though, but jumpin the gun got ye noticed for the wrong reasons an aa. Some boys could tread the line in atween. Some boys were born leaders.

Get up, the duty recruit clicked the switch an the strip light buzzed an pinged intae life.

Zander draped his towel ower his shooder an headed for the ablutions. He put his stuff on the shelf abeen the sink an looked intae the mirror. Tae his left Sharpe applied shavin foam tae his face. Zander looked inside his bag at his shavin brush an shavin soap. The brush, wi its smooth widden handle, had been left ahin by his faither. He looked in the mirror at Sharpe an Sharpe dragged his razor along the line o his jaw. Along the line o sinks, aa the ither recruits were usin shavin foam.

Zander brushed his teeth an filled the sink wi warm water an began tae wash, conscious o the boys aroon im. He patted his face wi his towel an began tae put his stuff back in the bag.

Are ye no shavin? Sharpe waved his razor.

Zander shook his heed.

Ye huv tae shave evry day if ye need tae or no, but, Sharpe’s voice echoed off the ablution waas.

Zander put his bag back on the shelf an filled the sink again. He took his time an hoped that maist o the boys widve gone afore he got his shavin brush oot. He took oot his brush an soap an dipped the brush in the sink an swirled it aboot a bit.

Check im oot wi iz ancient shavin brush, man, Sharpe wis in the mirror abeen Zander’s shooder. Boys turned tae look.

Zander rubbed the brush aroon the soap.

Is it yer granda’s, een o the boys elbowed Sharpe.

Naw, it’s his granny’s, Sharpe elbowed the boy back.

Ye done wi this sink, Miller shoodered Sharpe tae een side.

Settle, man, Sharpe stood aside.

Miller took Sharpe’s wash bag off the shelf an pushed it intae his chest an placed his ain bag on the shelf. He took oot his stuff, extractin it slowly. Toothbrush, toothpaste. Shavin stick an brush. Aul single blade razor.

He nodded at Zander’s brush.

Is that horsehair?

Zander telt im he wisna sure.

Ye get a much better lather wi a shavin brush, eh?

Zander nodded.

The boys went back tae their ain sinks an oot o the corner o his eye Zander watched Miller an mirrored the actions o Miller shavin. Carefully, deliberately, like it wis a ritual.

Corporal Munro marched them tae the clothin stores an he telt the boy at the front tae lead in an the recruits started anither process that wid flush mair o the civilian oot o them. They’d had their civvies locked awa, the hair clipped fae their heeds an the freedom tae walk an talk as they liked had been greatly diminished. In the stores they wid be issued wi the uniform an equipment that wid further transform them intae soldiers.

Zander edged forward an craned his neck tae try an see inside the storeroom. He could see boots that dangled fae kitbags an at the far side o the buildin a Tam O’Shanter sat on the top o a boy’s bag. Zander wis eager tae pull on his ain TOS an tae go fae bein naebdy tae bein a soldier an tae look smart an feel proud. Tae be like his faither.

Then he wis in through the door an immersed in the storeroom an the storeroom wis heavy wi the smell o a century an mair o leather an canvas an the trappins o conflicts an world wars. The kit stored here had absorbed the men who had come afore. Their sweat, through fear an labour alike. Their blood an tears were ingrained intae the kit an the soil an mud an rivers that they had crawled an fought through were ingrained intae the kit. Aa this had soaked intae the brick an timber o the storeroom an swirled aroon the recruits an seeped intae their skin so that they were not only bein issued wi a uniform, but they were also bein infused wi the spirits o aa those who’d gone afore. Aa those who’d been equipped in this buildin an had been sent awa tae break their kit in. Tae be torn, cut an chaffed by it. Tae clean it, an press it, an polish it. Tae lose it an tae beg borrow an steal it. Tae be kept warm an dry by it an tae be protected an saved by it. Tae die in it.

This is What You Get by Iain McLachlain is published by Rymour Books, priced £11.99.

The River is a life-spanning epic novel about death and new beginnings. It’s also about love, Scotland, happiness and acceptance. Here is author, Craig A. Smith, reading from the beginning.

The River

By Craig A. Smith

Published by Into Books

The River by Craig A. Smith is published by Into Books, priced £11.99.

I Don’t Do Mountains is an adventure story for children that explores the fears and beauty of getting out into nature. We spoke to author Barbara Henderson about her relationship to the book and The Great Outdoors.

I Don’t Do Mountains

By Barbara Henderson

Published by Scottish Mountaineering Press

Hello Barbara; it’s brilliant to see you publish another fantastic children’s book. What can you tell us about I Don’t Do Mountains?

It was so much fun to write. Most of my children’s book so far are historical fiction, so it was very freeing to write a contemporary adventure set in the great outdoors! It’s an adventure story about a hillwalking expedition which goes spectacularly wrong: the adult leader goes missing and the four youngsters must form unlikely alliances to navigate the dangers and challenge they face. Ultimately, though, I hope that the book inspires curiosity and enthusiasm rather than fear. The Scottish hills are an unfamiliar environment for many young people, so it was a great opportunity to feed in some information about what to do in an emergency, for example, or feature some of the region’s spectacular wildlife.

How much time do you spend in nature and why is it important to you as a writer?

Haha, I’m a dog owner, so I am outside four times a day. I live in Inverness, so some of the most spectacular landscape in Scotland is right on my doorstep. It’s one of the best ways to clear your head and get a bit of distance from day-to-day life. Nothing gives you perspective like a great view, right? And that doesn’t mean you have to head into the loneliest of places for days at a time. I am not particularly lithe or muscly outdoor material, but the hills are for everyone! Whatever your fitness or experience, there is a walk for you. One of my current favourites is a short circular wander into the hills above Loch Ness called the Change House Walk.

This book is set in The Cairngorms in particular. What do you love about them?

There is so much to love about the Cairngorms. As an avid birdwatcher, I particularly appreciate the wildlife there, but also the crystal-clear waters, often so still that they double the mountains in gorgeous reflections. The snow-topped distant peaks which have inspired countless myths and legends, too. My favourite time is just before sunrise when the undulating horizon takes on otherworldly pinks and orange hues – ‘the hidden fires’ as Nan Shepherd called them. If you want to get a feel for the place, you can do no better than Merry Glover’s book of the same title.

Your books are always packed with adventure. How do you keep coming up with troublesome scenarios to put your characters through?

I ask the ‘what if’ question, all of the time. Reading is a bit like a rollercoaster – if we are absorbed in the story, we have the illusion of danger, while being safe all the time. But even those feelings build resilience, and kids like the stakes to be high – they can handle the tension. I took to heart the advice from children’s author Helen Peters: ‘You can NEVER have enough jeopardy’.

Your main character Kenzie is a bit reluctant to leave her home comforts at first. How would you encourage young people to get outdoors and explore?

Kenzie doesn’t do mountains. She doesn’t do strangers either. In fact, Kenzie would happily stick to the library and other places where she feels safe – and who would blame her? I think people are reluctant to head out because they worry that they will meet challenges, but these environments are nothing to be scared of! Begin small – a gentle circular walk, or a smaller hill with a good path. There are loads of options on https://www.walkhighlands.co.uk/, and you can search by region, length and difficulty. I myself am far from a hardcore outdoorsy person – we just need to explore, give things a try and find out what works for us! As adults, I think we have a responsibility to facilitate this for young people too. If they know and appreciate the wild places, they are more likely to protect them.

What are you looking forward to reading in 2025?

I have already begun my 2025 in books with Susan Brownrigg’s historical children’s adventure Wrong Tracks, about the famous Rainhill Trials which was great. I also can’t wait for Ally Sherrick’s Rebel Heart – I have loved every single one of her adventures for children. In terms of Scottish books, I am absolutely buzzing for Michelle Sloan’s Mrs Burke and Mrs Hare. It’s not out till the summer, but I adored The Edinburgh Skating Club so much that I’m desperate to delve in!

I Don’t Do Mountains by Barbara Henderson is published by Scottish Mountaineering Press, priced £7.99.

Heather Parry’s new novel, Carrion Crow, is a gloriously gothic tale of an extraordinary relationship between a mother, Cécile Périgord, and her daughter, Marguerite Périgord. Cécile keeps Marguerite locked in the attic of their family home – for her own safety she says – with nothing but a sewing machine, a copy of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, and a carrion crow who has come to nest in the rafters, for company.

BooksfromScotland asked Heather to recommend five more stories of unforgettable mother-daughter relationships.

Carrion Crow

By Heather Parry

Published by Doubleday

Concerning My Daughter – Kim Hye-jin (trans. Jamie Chang)