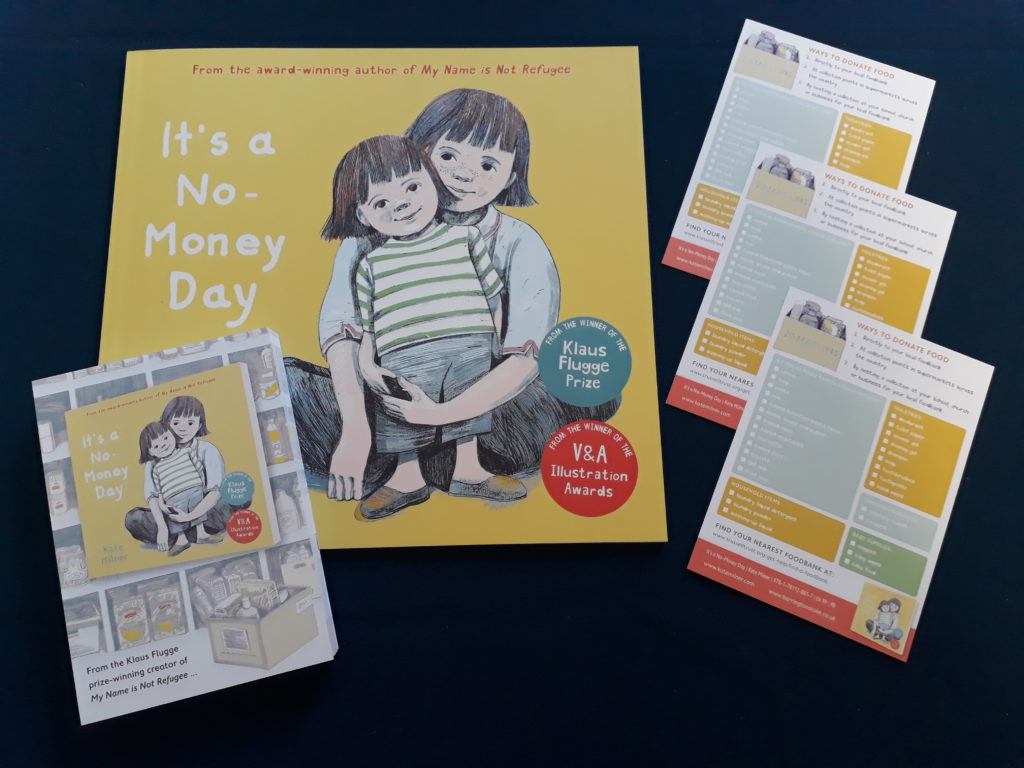

Author and illustrator – and campaigner – Kate Milner is garnering great praise and prizes for her beautifully-illustrated and empathetic picture books. It’s a No-Money Day follows her award-winning My Name is Not Refugee and explores life below the poverty line with sensitivity and stunning artwork. With more than one in four children in the UK growing up in poverty and many dependent on foodbanks to survive, Kate Milner has given us an excellent starting point for parents to discuss a difficult issue with young children.

It’s a No-Money Day

By Kate Milner

Published by Barrington Stoke

To mark publication of It’s a No-Money Day, publishers Barrington Stoke are encouraging readers of all ages to donate to their local foodbank. They’ve produced postcards with information on where to find your local branch and what items are most needed, so to request a bundle for your classroom, library, bookshop or just for home, please email kirstin.lamb@barringtonstoke.co.uk

It’s a No-Money Day by Kate Milner is published by Barrington Stoke, priced £6.99

Today is National Poetry Day, and to celebrate BooksfromScotland are glad to share these extracts from Stephen Watt’s Fairy Rock, a crime novel written in verse. Set in Glasgow at the turn of the millenium it roams around the worlds of organised crime and sectarianism while exploring the disaffection and alienation from those left behind by poverty.

Extracts taken from Fairy Rock

By Stephen Watt

Published by Red Squirrel Press

DYNAMATION

Paying tribute to the savage giant cyclopes

in Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, army friends had informally

named him Phemus after an explosive mine

accidentally discharged on a military training exercise.

One scorched doll’s eye shunted towards his nasal bridge

and like a Harryhausen creation,

he twitched, shifted damaged bones frame by frame

like a stop-motion picture being filmed in the Gallowgate.

Past the vinegary taxi ranks and weed-perfumed council vans,

Phemus’ bald, ugly structure lumbered between shady Irish bars

which cops relished to monitor.

Rumour whispered like Tolbooth traitors

that he had partaken in Satanic rituals

and that unfortunate homeless individuals

had meat sucked from their bones like crabs

inside their stopgap squats;

their metacarpals suited for dental floss.

Such nightmarish skinder hindered an ability to ever get close.

Abusing any bar’s breakfast license,

Phemus seemingly turned his blind eye

to the bigotry and violence,

squandering his dole money on coffin nails and stout.

As clouds of his soul slithered from his nostrils,

not a single patron had suspected

that he was a snout, a covert informant

for the filth, someone’s animated model

given new life to brief; Argonaut in training.

OLD FIRM DAY

is tense flowers

of blue and green, blossoming inside boozers

where a thick air of language and stale sweatoverflows on to the street.

It is a day to think twice about the colour

of your footwear, nail varnish, contact lens.

In the home, the unwalked dog meditates pavements,

daren’t make eye contact if they lose.

The church is well-stocked ciborium’s and empty pews.

Is it true priests get free seats at Parkheid?

On trains, no-one wants the day-shift

as the city spins grave colours on the faces of the neutrals.

Trouble is not prejudiced, welcomes all-comers

into its morning-after papers with blades incising faces

and into ribs in the dangerous places

your parents once warned you about.

Southern India, child-labour stitched-flags

stir hatred and poison and for many, this is an enjoyment –

a reason for existing. A sense of belonging.

Keep your head down

if you don’t like what you see. Glasgow’s about to kick off.

SHIPMENT

Loose lips sink shipments. House whisky cackling aside,

the two old, flat capped boys inside the Tolbooth Bar

had lowered their voices to hide their schemes.

Semi-automatic ArmaLite AR-15’s and detachable magazines

were easy to break into parts.

These had proven popular with Provo farmers

overpowered by British troops during the early scraps

of what became known as The Troubles.

The weapons would be smuggled in crates

laden with white sports socks.

A pickup point had been arranged

at Cairnryan Port, wherein a messenger would transport the box

up the A77 to an agreed drop-off spot

on the outskirts of Glasgow.

The job was worth two thousand notes

and word was that there was a boy just released

from a short-term prison stint identified to carry out the errand.

Below the television in the corner of the pub,

Phemus was using his military-acquired skills

to lip-read, squinting his remaining eye

to take heed of every detail.

The police would pay him well for such information

but now new priorities were leading his reasoning.

TABLOID HAIKU

TOLBOOTH REGULAR

SLAIN AT CLOSED ICE RINK CENTRE.

REPUBLICAN LINKS.

Fairy Rock by Stephen Watt is published by Red Squirrel Press, priced £10.00

Our final piece in our Translation as Conversation strand comes in the week where we celebrated International Translation Day. Here, translator Fionn Petch tells us how travelling and living abroad contributed to his skills in his chosen field.

Turning Together

“as a translator you need to be a chameleon in life as on the page”

Bear with me. I’ll get to the conversation bit. Though it’s already happening, here, now.

I grew up in Scotland but took off quite early, travelling in Latin America, and found myself living in Mexico City, where I stayed for over a decade. My first years there were a period of trying out different lives, trying them on for size. Partly out of necessity and partly out of a desire to challenge my fears and disinclinations, I invented or accepted jobs that took me beyond my own sense of who I was. So, I followed the example of seemingly half the city and set up a street stall to sell my wares: my own home-baked bread. I learned how to lay bricks and render a wall with cement. I presented movies to crowded theatres at film festivals. I modelled clothes on a catwalk. I burrowed into corporate towers to teach English to bored executives, buffing up their language skills with the same affected good humour as the shoeshine guy who did their shoes.

In short, I translated myself into different worlds, worlds I could move between with a facility that felt impossible at home. I’d been freed from the trammels of accent, of upbringing and of expectations that can so constrict you in the country in which you’re born. At some point things coalesced, and I found that I had become a translator. And it turned out that all these meanderings had been good preparation for that task. The image I often turn to is that of the chameleon: as a translator you need to be a chameleon in life as on the page, to have a malleability that enables you to adapt to different registers of dialogue, to class and cultural contexts.

I’m not just talking about literary translation, of course. Having the agility to swiftly grasp a context and place yourself in it is just as important to so-called ‘commercial’ translation. Often disparaged as the poor relation, it is in fact an important foil to working on fiction or poetry. (Apart from anything else, it’s rare to be able to make a living solely as a literary translator, without any other source of income.) Such texts – whether magazine articles, product websites, tourist brochures, or whatever – make up the stuff of the language-world that an author is immersed in and draws on. Translating that world is the best way to become conversational with it and – assuming you’re not only doing home appliance manuals – of getting to know its outer reaches.

During this time I also embarked on a PhD at the National University of Mexico, not because I wanted to pursue an academic career but because many years earlier a work of translated fiction pulled from my dad’s bookshelf, A Different Sea by Claudio Magris, had led to an obsession with the little-known thinker Carlo Michelstaedter and his book Persuasion and Rhetoric. As I wrote my thesis, which focused on the shift between poetic and rational persuasion that took place in early Greek thought, the notion of ‘turning’ emerged as key. Turning in the sense of words, from within or without, altering your course or bearing. And I came to see translation as exemplary of this dilemma of persuasion, as a twisting and turning between choices. Translation is about turning over alternatives, about countless tiny decisions that must be taken without there being an absolute basis for determining if they are the right ones or not. All you have to go on are the myriad decisions previously taken by the author, decisions which you must track closely, but not simply imitate.

And so, a kind of conversation is established, even if it’s one where the author doesn’t exactly answer back. Perhaps surprisingly, the etymology of the word ‘conversation’ refers not to ‘speaking together’ but rather ‘turning together’ and originally had a sense of ‘dwelling, keeping company with’. When you walk alongside someone in conversation you do not march parade-style at a fixed distance, rather there is a constant back-and-forth of brushed shoulders, touched arms, glances of complicity, frowns of misunderstanding, while the accidents of the path itself throw you momentarily closer together or further apart.

As with the feet, so with the mind: a good conversation should not just involve repeating facts or opinions at each other, but engaging in a deeper kind of listening. It is not simply about trying to convince, to win somebody over with your arguments, but about making space for the other, letting in the possibility of being changed by the other. It is a turning-towards the other, one that invokes the affirmation of the gaze, and an attentiveness that now seems almost irretrievably lost amidst the catastrophe of social media.

Depictions of St. Jerome, patron saint of translators, whose feast day on September 30 has become International Translation Day, almost always show him working alone in his study, with only a lion and a skull for company. Nevertheless, despite the solitary character of the translator’s work, there is always someone else there. When done with care, translation embodies all the attributes of a good conversation, because it requires you to go beyond single-mindedness, beyond singularity of thought, and to open yourself up to a text, to another person’s experience and perspective on the world. As a translator, you are constantly practising this art of conversation by not imposing your own thoughts, not adapting the author’s words to your preconceived ideas, but rather turning towards the author, hosting them, allowing in that newness, all that strangeness, that multiplicity. It is an act of radical empathy.

In her wonderful book Translation as Transhumance (translated by Ros Schwartz), Mireille Gansel expresses this idea more simply and beautifully than I can:

I remember clearly how, one morning as the snows were melting, as I sat at the ancient table beneath the blackened beams, it suddenly dawned on me that the stranger was not the other, it was me. I was the one who had everything to learn, everything to understand, from the other. That was probably my most essential lesson in translation.

So, when I think about the conversation that is translation, whether I am working on a novel or on a very ordinary kind of text, I do so in the light of my own many-turning path into the profession. All those glimpsed potential other lives, those times I felt like a stranger to myself, inform me, just as every new book continues to change me. Translation, in the end, is a conversation with ourselves, with our many human selves.

Fionn Petch is a Scottish-born translator working from Spanish and French into English. He lived in Mexico City for 12 years, where he completed a PhD in Philosophy at the UNAM, and now lives in Berlin. Since 2017 he has been translating and editing Latin American fiction for Edinburgh-based Charco Press, including translations of Fireflies by Luis Sagasti (shortlisted for the Translators’ Association First Translation Award 2018) and The Distance Between Us by Renato Cisneros (winner of an English PEN Award, 2018).

Twitter: @elusiveword

Emily Ilett, winner of the 2017 Kelpies Prize, has written a story of bravery and kindness that celebrates the power of friendship and will have you holding your breath at each twist and turn. We hope you enjoy this extract.

Extract taken from The Girl Who Lost Her Shadow

By Emily Ilett

Published by Floris Books

Gail’s stomach twisted as she heard the bed creak upstairs. Kay’s shadow hadn’t just run away. It was Gail’s fault. If she hadn’t kicked it… The hurt in Kay’s brown eyes bubbled in front of her. “I chased her shadow away,” Gail said to the empty kitchen. She grabbed a photo of Kay from the fridge, stuffing it into her bag. “And now I’ll get it back.”

When she opened the door, the wind tugged at her hair. Gail squeezed her eyes against the rain, peering forward. Behind her house, the ground rose steeply towards Ben Fiadhaich, the wild hill. There it was: she could just make out the dark blur of Kay’s shadow pouring over the damp grass at the end of their garden. Gail saw it flow over the wall towards the river, which tumbled icy-cold and fierce down the hillside. “Wait,” she cried out, but the word was tugged from her lips by the wind and undone.

Rain soaked through her leggings as she ran down the garden and clambered over the wall. Here, a footpath curled along the river and out of the village for a mile, before forking into two: one beginning long-legged zigzags up the hillside, the other dipping to wind along the jagged cliff edge towards the south of the island. The shadow was metres in front of her, its shape shifting and swirling as it rolled over pebbles and through puddles.

Gail’s legs burned as she tried to keep up, blinking rain out of her eyes. At least now she was out of the house she could breathe again. Her head didn’t feel so squashed. And once she brought Kay’s shadow home, maybe everything would go back to how it was before. Before their dad walked out. Before Kay got sick. Before she stopped swimming.

Gail swallowed.

It had to.

She was out of the village now. Ben Fiadhaich loomed on her left, its slope scattered with straggles of trees and ledges of rock where shallow caves pitted the hillside like eyes. Gail crossed her fingers, hoping that Kay’s shadow would turn right towards the cliffs where kittiwakes wheeled and cried. But the dark shape slipped left at the fork, and Gail groaned and pressed her hands against her legs to push against the rise. No one climbed this side of Ben Fiadhaich. The slope was jagged and crumbling and there were too many whispered stories about the caves. Lynx Cave, Oyster Cave, Cave of Thieves.

The shadow slid in and out of her sight, slippery as a fish. It was moving further away. Now it left the path, darting over rocks and between tall pines.

Gail plunged through the grass, hands lurching to steady herself against the uneven ground. As she slalomed between trees, the rain petered to a fine drizzle. Here, the ground felt alive with shadows, stretching and reaching towards her. Which one was Kay’s? How would she know? But as she saw a dark shape sweeping over the grass, her mouth twitched in relief. Of course she’d know Kay’s shadow. It was like recognising her sister’s handwriting, or hearing the sound of her footsteps on the stairs.

Gail fought to make her legs move faster but the shadow was always ahead of her. Her chest heaving in waves, she tried to sprint but a stitch pierced her side and she folded over, clutching her stomach. “I can’t,” she gasped, and she crumpled to the ground. And she lay, panting for breath, her legs stuck out in front of her, as the shadow moved steadily up the hillside, closer and closer to the caves.

Gail had short legs, big feet and seal-dark eyes that were fond of staring. Her brown cheeks were dotted with so many freckles it looked like a bowl of Coco Pops had been tipped onto them. Beneath her coat and jumper, she wore a tawny-orange T-shirt which almost reached her knees, and her sodden leggings were zigzagged blue and green. When she talked, her whole face moved, and when she ran she jumped high in the air so as not to trip over her feet. But she tried not to run if she could help it. She was a swimmer, not a runner. Gail winced. And not much of a swimmer either, without Kay.

Gail was higher and further from the village than she’d thought. Below, the island rolled down from Ben Fiadhaich, speckled with villages and towns and silver beaches. She could see the harbour to her right, reaching out towards the mainland, where her mum worked at the hospital. Fishing boats and ferries dotted the sea. Fiorport, the harbour town, was where Gail went to her new high school. She’d been looking forward to starting for months, looking forward to Kay showing her around. But then Kay hadn’t started back after summer and Gail caught the bus alone each morning, her mouth a thin silent line. Her friends had tried to understand, for a bit. But now they’d given up. Even Rin had stopped sitting next to her at lunch.

“You don’t seem like you any more,” she’d said. “You’ve changed, Gail.”

Gail grimaced. She had changed. Just like Kay had. It began when they stopped swimming together. Her edges felt wobbly and uncertain. No wonder her shadow had run away.

As a bubble of anger grew inside her, the stitch in Gail’s side prickled and she pushed her hands against it, below her ribs. It felt like a pufferfish. The spikes made her fists tighten and a flood of scarlet blotched her throat and ears. Gail took a deep breath. It had been two weeks after their dad left that she’d first felt the pufferfish inside her stomach.

On that evening, when the light had already begun to seep from her sister’s eyes, she’d found a crab shell speckled like a starry night sky and had taken it to show Kay. It was beautiful, covered in hundreds of tiny galaxies, and inside it was the purple of blackberry stains and twilight. Kay wouldn’t even look at it, her back curved against Gail, eyes half-closed. So Gail had pressed it into Kay’s hand, but she’d pressed too hard and the shell had crumbled like dust between their fingers. Kay had turned around then, flicking at the broken pieces of shell on her duvet, her eyes cold. She’d said that real marine biologists didn’t break stuff.

It was then that Gail had first felt a sharp blossom of spikes in her stomach and a flare of anger that made her crush the last of the starry shell in her own fist. Since then, the pufferfish inside her stomach kept her awake at night. Anger bubbled through her all the time and she couldn’t make it stop.

Gail took a deep gulp of air. Kay would make it stop. Once Gail got her shadow back, everything would return to normal.

The Girl Who Lost Her Shadow by Emily Ilett is published by Floris Books, priced £6.99

Cracking the Enigma code has long been considered one of the key events in the Allied victory over Nazi Germany. In Enigma: The Untold Story of the Secret Capture, we discover the story of David Balme, the soldier who went aboard a German U-boat and brought back the Enigma machine.

Extract taken from Enigma: The Untold Story of the Secret Capture

By Peter Hore

Published by Whittles Publishing

Neither Balme nor telegraphist Alan Long knew anything about Enigma, but they were both intrigued by this strange looking typewriter.

‘And we both thought it looked very interesting, probably some sort of decoding machine, so I said: “Can you unscrew it?” And he [Long] had a little set of tools, very well equipped, and he unscrewed all the screws and this thing, about 2 feet by 1 foot, I suppose, was the famous Enigma machine. The Morse code on their Enigma machine would come in from Berlin on to their machine and would be immediately transposed into another code, and by pressing a button you got a different message. This was the famous Enigma coding machine, which we, the Navy, had never managed to capture before. Anyway we unscrewed it and sent it up. Quite difficult, about 2 feet by 1 foot and quite heavy, and one only had one arm for the machine and one arm for going up the ladder. Quite difficult. Anyway we got it up. Got it into one of the boats and back to HMS Bulldog. This was the first time that the British had ever got a German Enigma machine and it was worth untold gold.’

It not was, strictly, the first time that the British had ever got a German Enigma machine. Enigma had been invented in the 1920s, when it was used commercially, and it had only later been adapted by several countries to military use. Starting in 1932, Polish military intelligence had ‘broken’ German Enigma machines using reverse engineering, mathematics and material supplied by the French.

The Enigma machine consisted of a set of rotors that were driven electrically. Coding was achieving by the setting of the rotors, and each rotor had twenty-six positions, one for each letter of the alphabet. There was a choice of rotors to install (at this stage of the war the German navy used three rotors from a choice of eight). The order of the rotors could be changed, and the initial position for each could be varied. There was also a plug board, and all of this equipment was changed and set differently each day. In addition, each individual message was encrypted using an additional, three-letter key modification. The Poles devised mechanical devices for breaking Enigma ciphers, but as the Germans introduced more complexity to their Enigma machines, decryption became more and more difficult, requiring resources that the Poles did not have.

In 1939 the Poles shared their knowledge with the British and French, and, after the fall of France, Britain exploited this knowledge alone. Through German procedural flaws, operator mistakes, and capture of key tables and hardware, British codebreakers gradually mastered Enigma. At first the intelligence gained from read Enigma and other sources was known as Boniface, but from 1941 onwards it was designated as Ultra. Ultra was particularly important in the Battle of Atlantic because of the way in which the U-boats were operated.

*

The war at sea and in particular the Battle of the Atlantic was profoundly changed by the secret capture Balme had made. Bletchley began to read continuously and with little or no delay the wireless traffic in the ‘home’ or Heimisch settings of German naval Enigma, which were common to most of the German surface navy and to U-boats in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. The combined effect of these captures was to enable Bletchley to read all German naval signal traffic for June and July, including ‘officer only’ signals, concurrently with the intended German recipients.

It also gave Bletchley such an insight into the workings of Enigma that by the beginning of August ‘it had finally established its mastery over the home waters settings, a mastery which enabled it to read the whole of the traffic for the rest of the war except for occasional days in the second half of 1941 with little delay. The maximum delay was 72 hours and the normal delay was much less, often only a few hours.’

Balme’s pinch saved countless Allied ships and lives, and brought about the end of numerous U-boats and their crews. Ultimately, in the opinion of one naval historian, it led two years later to a German retreat from the North Atlantic, which was a strategic victory as important as the Battle of Midway in the Pacific and the Battle of Stalingrad in Europe.

Enigma: The Untold Story of the Secret Capture by Peter Hore is published by Whittles Publishing, priced £16.99

The Jacobite Rebellion looms large in Scotland’s historical memory, though in Desmond Seward’s new complete history of the movement, and in this extract, he shows the restoration of the House of Stewart to the throne of the United Kingdom was not only fought on fields in Scotland.

Extract taken from The King Over The Water: A Complete History of the Jacobites

By Desmond Seward

Published by Birlinn Ltd

Too long he’s been excluded,

Too long we’ve been deluded.

Anon, ‘Let our Great James come over’

The Bell Tavern in King Street was within strolling distance of the Palace of Westminster and from the early years of Anne’s reign High Tory MPs who belonged to the Country Party – the landed interest – had met there to drink vast quantities of October ale (so called from being brewed in that month). Although a portrait of the Queen hung in the room where they gathered, many toasts were drunk to ‘The King over the Water’, a name now used by Jacobites when drinking James III’s health as they passed their tankards over a decanter, a finger bowl or a glass filled with water.

Backwoodsmen of the sort caricatured by Joseph Addison in The Tory Foxhunter, they were High Churchmen who detested the ‘Rump’ (the Whig party), ‘Low Churchmen’ (Latitudinarians) and Dissenters. They wanted to purge Parliament by impeaching half a dozen Whig MPs – ‘get off five or six heads’, as Jonathan Swift put it – and opposed not only taxes for wars abroad but a standing army in time of peace. In 1709 the political wind began to blow their way.

On Guy Fawkes Day, Dr Henry Sacheverell of Magdalen College, Oxford, gave a sermon at St Paul’s Cathedral on ‘The Perils of False Brethren’ which attacked the Toleration Act, Low Churchmen and Dissenters, claiming the Church of England was in mortal danger. Although he ranted, he had a point. Since the Toleration Act of 1691 over 2,500 Dissenting chapels had been licensed and everywhere parsons were dismayed by the numbers who attended them instead of worshipping at the parish church.

Printed as a pamphlet, the sermon sold 100,000 copies. In a second sermon, Sacheverell belittled the Revolution, extolling passive obedience and referring to the Whig leader Godolphin as ‘Volpone’ – the sly villain of Ben Jonson’s comedy. Every High Churchman applauded him. There were roars of approval at the Bell Tavern, his health drunk in bumper after bumper.

The doctor was impeached for criticising ‘her Majesty and her government’ and tried at Westminster Hall, with General Stanhope insisting that the sermons favoured ‘a prince on the other side of the water’. Although she disapproved of him, the Queen attended his trial, her sedan chair greeted by a pro-Sacheverell crowd with shouts of ‘God bless your Majesty and the Church’. Mobs destroyed Dissenter meeting houses and did their best to set fire to the London residence of the Low Church Bishop of Salisbury, the aged Gilbert Burnet.

Found guilty, the doctor was forbidden to preach for three years, his sermons being burned by the common hangman, but it was a Pyrrhic victory for the government. Rewarded by an admirer with a rich living on the Welsh Border, Sacheverell’s coach was cheered all the way to Shropshire. What upset the Whigs was his attack on the Revolution, which they saw as a message of support for the Restoration. They were quite right – soon after, he wrote to King James, offering his services.

Dr Sacheverell’s friends were not confined to the Bell Tavern or the Country Party, but to be found in large numbers among the London mob and in the applauding crowds along the Great West Road – especially at Bath and Bristol.

*

James III’s baptism of fire 1709–10

In November 1709 Archbishop Fenelon of Cambray, a cleric of a very different sort from Rance or the Jansenists, met King James and was struck by his good sense and amiability. Soon a close friend, Fenelon gave him his own conviction that every man has an overriding duty to care for his neighbour. He may also have instilled Quietism – abandonment to God’s will to the point of never asking his help – which encouraged a mood akin to fatalism.

Notwithstanding Quietism, to gain combat experience the king served with the French army as the Chevalier de St George in the Maison du Roy (Louis XIV’s household brigade) and fought against Marlborough. He saw action at Oudenarde in 1708, admirably cool under fire, according to Berwick – he laughed when he saw Georg August of Hanover, the Elector’s son, have his horse shot under him. Afterwards, Marlborough openly expressed pleasure at hearing such a good account of James. But it was in September 1709 during the murderous bloodbath at Malplaquet, Marlborough’s last great victory over the French, that he really distinguished himself, charging twelve times with the Maison du Roy and being wounded. At one point he fought on foot at the head of the French grenadiers. Afterwards, English soldiers drank his health, Marlborough warmly praising his gallantry.

The war became unpopular in England, despite the Duke of Marlborough’s victories and Whig attempts to turn him into a national hero. Many resented his rewards, such as Blenheim Palace, and his thriftiness – at Bath he went on foot in the worst weather rather than pay 6d for a sedan chair. People wanted an end to spiralling war taxation, besides being shocked by the casualties. Queen Anne wailed, ‘Will this bloodshed never stop?’

She had transferred her affections from the Duchess of Marlborough to the ingratiating Abigail Masham, a distressed gentlewoman who had joined the royal household as a ‘dresser’ – a lady’s maid. The duchess responded to the takeover by hinting at lesbianism. Unruffled, Mrs Masham, a Tory (and secret Jacobite) undermined Anne’s confidence in Godolphin, securing his dismissal in August 1710.

At a general election in October the Tories won a big majority, partly because of Sacheverell’s trial but mainly from anger at never ending war and heavy taxes. They immediately formed a government. The Bell Tavern circle increased to over 150 MPs, naming itself the October Club in honour of the new ministry and its favourite beverage. It included a hundred known Jacobites, the most extreme of whom were nicknamed ‘Tantivies’.

The King Over The Water: A Complete History of the Jacobites by Desmond Seward is published by Birlinn Ltd, priced £25.00

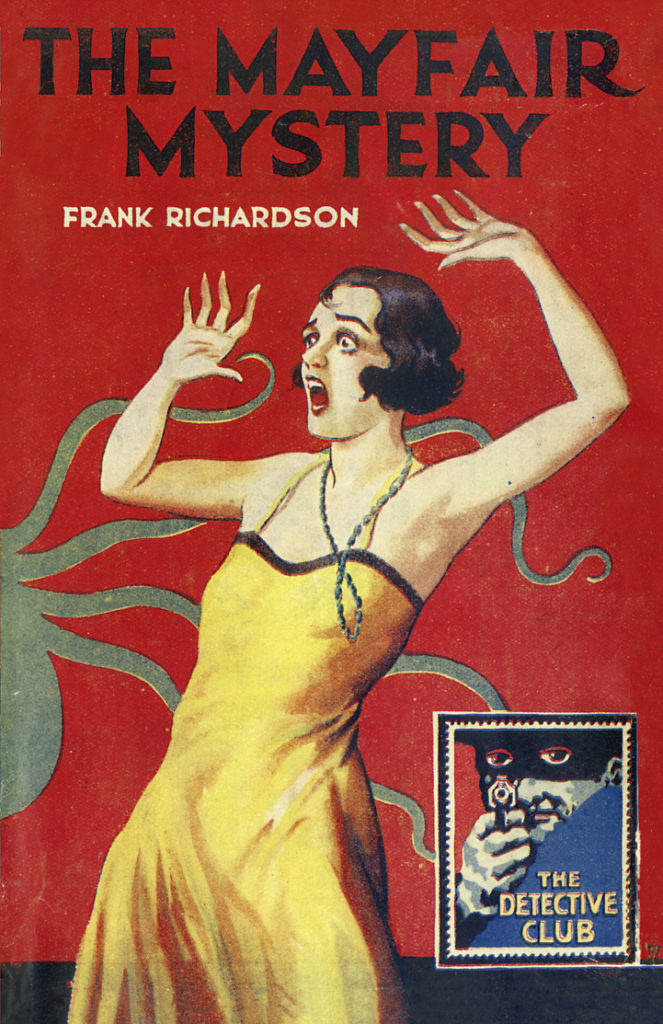

Publishing archives are full of wonder, and HarperCollins’s archive is bursting with treats. Here, archivist Dawn Sinclair tells us a little about how crime fiction transformed over the years.

The archive of HarperCollins Publishers is full of stories of all kinds – romance, western, thriller and of course, crime. This genre has rarely been out of fashion over the decades. William Collins and now HarperCollins have ensured they have published some of the most well-known names in crime from the early days. The archive holds books, artwork, correspondence, editorial material and all sorts of ephemera. Our collections give us the chance to understand our history as a company, celebrate it and all its requisite parts.

At the beginning of the 1900s, there was an obvious trend for the murder mystery novel and people had become interested in the workings of the police and moreover detectives due to writers such as Wilkie Collins, Edgar Allan Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle. At this time, William Collins and Sons was led by William Collins IV, his brother Godfrey and their cousin William Collins Dickson. All three were astute business men and each had an area of the business to look after. Godfrey, who oversaw the publishing side of the business, was also a Liberal MP and became the Secretary of State for Scotland in 1932. Despite juggling his many roles, it was he who recognised the popularity of crime books.

At the beginning of the 1900s, there was an obvious trend for the murder mystery novel and people had become interested in the workings of the police and moreover detectives due to writers such as Wilkie Collins, Edgar Allan Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle. At this time, William Collins and Sons was led by William Collins IV, his brother Godfrey and their cousin William Collins Dickson. All three were astute business men and each had an area of the business to look after. Godfrey, who oversaw the publishing side of the business, was also a Liberal MP and became the Secretary of State for Scotland in 1932. Despite juggling his many roles, it was he who recognised the popularity of crime books.

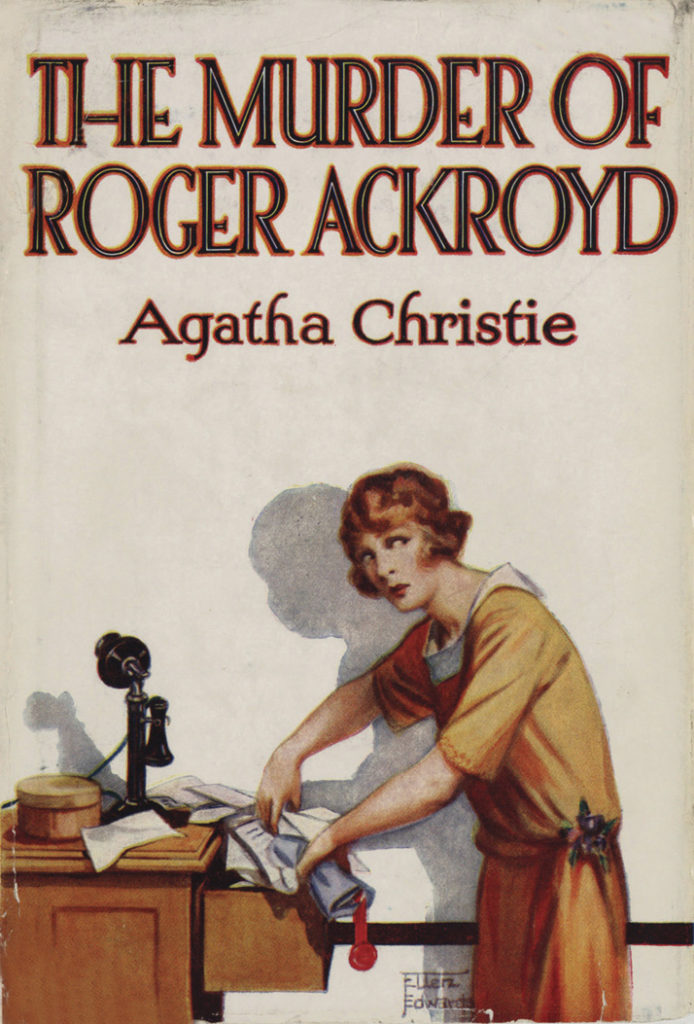

Therefore, in 1919, the first Collins Detective story was published – ‘The Skeleton Key’ by Bernard Capes. This book started a long tradition of Collins publishing crime stories for decades to come. Next, Freeman Wills Crofts’ book ‘The Cask’, chosen from the many crime story manuscripts which had been sent to Collins, was published. Wills Crofts went on to write another 16 books for Collins which included his ‘Inspector French’ series. The momentum had taken over and the number of crime authors multiplied. In 1926, Collins hit the crown jewels and published Agatha’s Christie first book with the company – ‘The Murder of Roger Ackroyd’. Agatha’s talent was clear and 93 years later, we still publish her books.

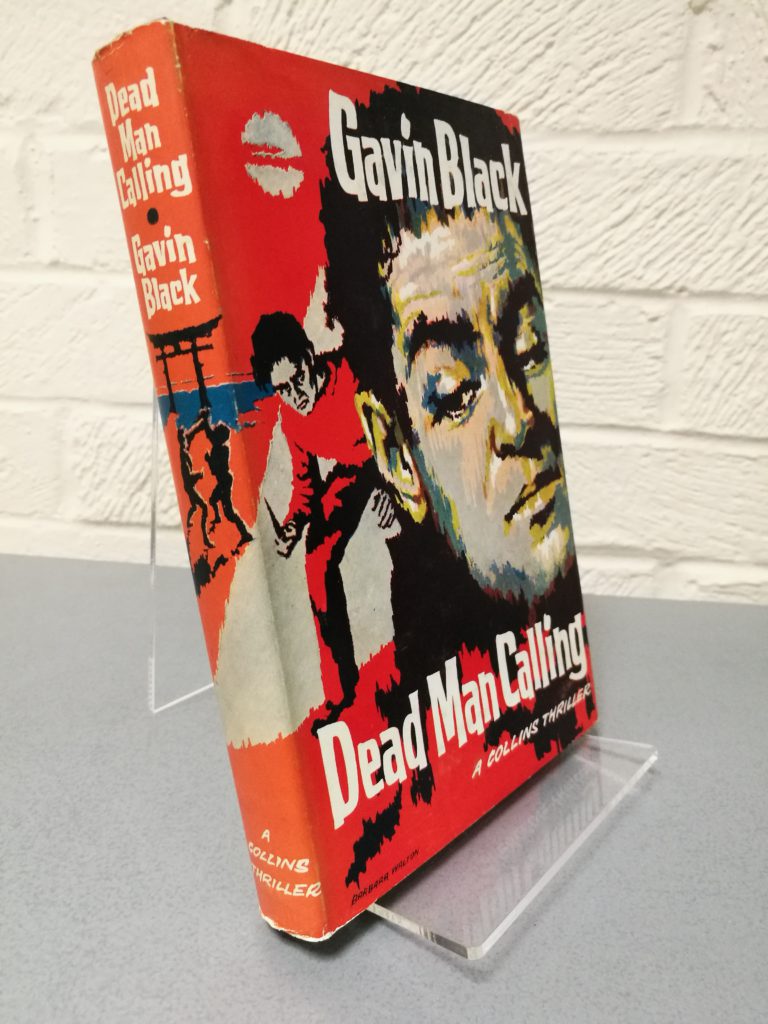

Around 260 authors were published under the imprint of the Crime Club, some with only one or two books or some like Agatha Christie with 80 books. Authors came from all over the world from New Zealand to the UK. There was also a small contingent of Scottish authors who were published under the Crime Club. One such author is Gavin Black. However, his story is a bit more complex than you expect. Gavin Black was the pseudonym of Oswald Wynd. He was born in Tokyo to Scottish parents, who were originally from Perth. They had moved to Japan to run a mission. Oswald was raised in Japan and spoke both Japanese and English. Despite this, he was and is considered a Scottish author. After studying at the University of Edinburgh, he joined the war effort and travelled many places. However, he was captured as a prisoner of war for three years in Malaya.

After his time in the army and as a prisoner, he returned to Scotland and began a long career in writing. His first book with Collins, Suddenly at Singapore, was published in 1961 and was well received. His knowledge of South East Asia and military experience gave his books extra flair and gave both crime and thriller fans a view into the exotic. Most of his subsequent books were set in Asia and were full of twists and turns. However, in A Big Wind for Summer, Black’s protagonist visits the Isle of Arran. The covers for his books were equally interesting. Mostly of them were illustrated by Barbara Walton, who was a prolific dustjacket illustrator for many years with Collins and other publishers.

Wynd died in Scotland in 1998, at the age of 85. While he was never a worldwide phenomenon, he is considered a writer of immensely intriguing books but also someone who had an equally interesting life.

Although the Crime Club stopped in 1994, HarperCollins continued to publish many important crime writers. The perennial writers like Agatha Christie were obviously still on our crime list but many new authors were appearing on the scene including Val McDermid, Camilla Lackberg and Stuart MacBride. In 2005, HarperCollins published Cold Granite by Stuart MacBride and from that first book, there has been 12 more Logan McRae novels, two standalone novels, short stories and the Oldcastle novels. However, with such a plethora of titles going back to the Golden Age of Crime, in August 2015, the first Detective Club Crime Classic novels were published. Using original covers from the early 1920s plus the classic Detective Club logo, each book has an introduction from a crime writer or expert about what the book originally brought to the genre. The Perfect Crime by Israel Zangwill, Called Back by Hugh Conway and The Mayfair Mystery by Frank Richardson were the first three titles to be republished. As the end of 2018, 50 books have been made available to new modern audience of crime fans.

As with all their books, Collins wanted crime books to be accessible to everyone. Our crime novels were published in all different forms and prices from the Crime Club hardbacks, the White Circle paperbacks and the cheap 6d editions. Due to the unwavering popularity of crime stories, Collins have amassed a collection of some of the greatest writers in history. Telling the story of crime in the Archive at HarperCollins Publishers is one that is easy to tell.

In this latest book from National Galleries Scotland, coinciding with the exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Modern Two), Patrick Elliott shows us that collage as an art form has been with us for hundreds of years. Here he tells us why he put the book and exhibition together, and tells us a little about how the Cubists ‘invented’ the form.

Extract from Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage

By Patrick Elliott

Published by National Galleries Scotland

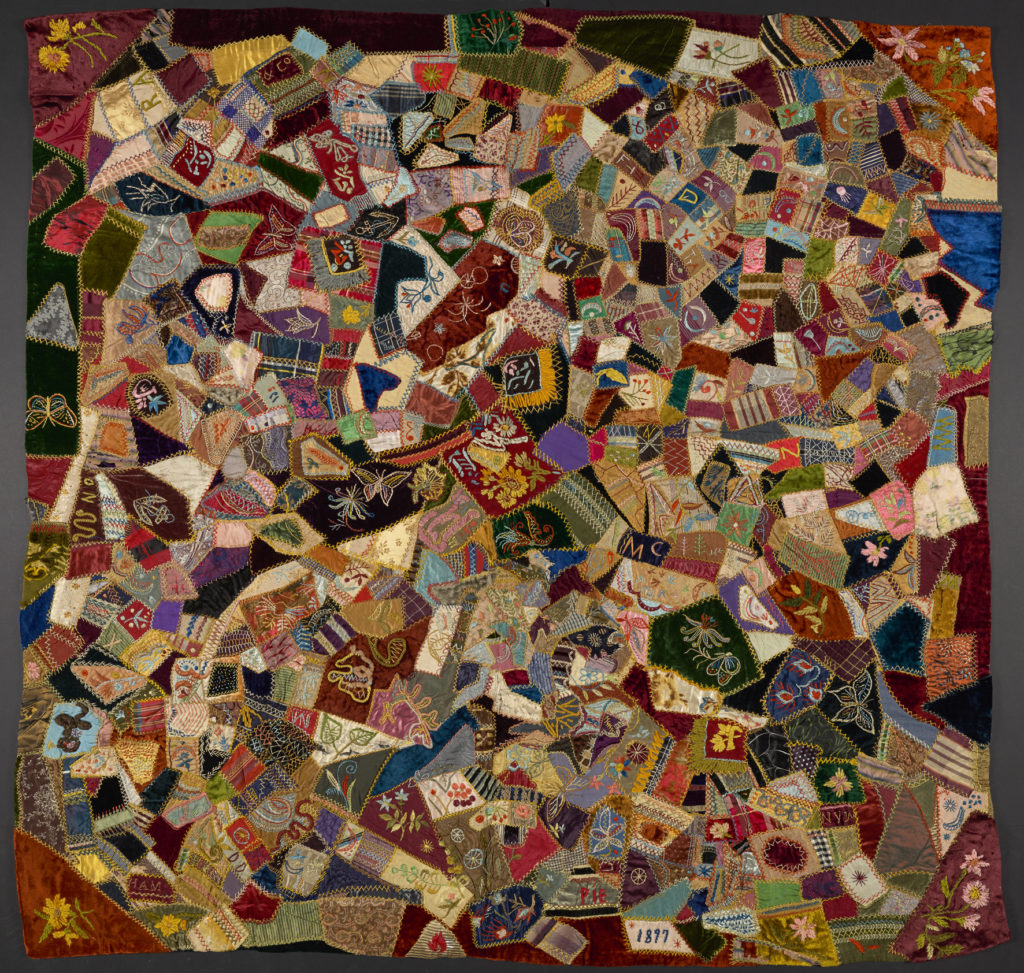

The idea of collage is so brilliant, so simple, so rich and imaginative in every way, that you might wonder why nobody had thought of it before. Well in fact they had, but historians of modern art have tended to ignore anything before 1912. Collage has a history stretching back hundreds of years, but at the time it was not called collage. That term, deriving from the French verb coller, meaning ‘to stick’, evolved as late as the 1920s. Before that it was called ‘scrap work’, ‘découpage’, ‘mosaick’ work and ‘adornment’. (In nineteenth-century dictionaries, the word ‘collage’ means bill posting and wallpaper hanging.) And the people who were cutting and pasting were not seen as artists. They were amateurs having fun, being creative and passing time. Many of the early collagists were women and children, and people with no formal training, such as tailors, writers and quilt-makers. Occasionally professionals used ‘cut-and-paste’ methods to save time and money, and early photographers used collage techniques such as photomontage and composite printing to get around the technical limitations of their art. Modern collage emerges from this amateur, craft activity.

In the 1910s collage – or papier collé as it was then known – was embraced by the Cubists, Futurists, Dada and Russian Constructivists as a way of attacking convention and mirroring the dynamic, modern machine age. In the 1920s collage became the favoured technique of the Surrealists. The French word ‘Surrealism’ means ‘beyond realism’ and that is where collage could take them. Collage allowed the Surrealists to fight academic traditions on the one hand, and on the other to create seamless, credible worlds suggestive of dreams and nightmares. The Pop Artists took to collage as a direct way of incorporating popular culture of magazines and posters into their work. In the 1960s and 1970s collage became a favourite tool of the Counter-Culture: it was cheap, quick and was, by its nature, disruptive. It was the technique of choice for the anti-Vietnam generation, and for Feminists, Punks and for anyone making photocopied Fanzines. Today, photoshop cut-and-paste techniques are used by millions of us, daily. Embracing the work of amateurs and professionals, men and women, children and photographers, film-makers and performance artists, collage is the most democratic, varied and inclusive of art forms.

We are in Paris and it is 1912: Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and Georges Braque (1882–1963) have rebelled against the Renaissance ideal of trying to ‘copy’ nature and present a picture as if it were a fixed view seen through a window. Photography has taken over that job; a child with a Box Brownie can do better. Instead, they want to recreate the experience of looking at their subjects from a multitude of different angles and then build those different views into a single picture. It is an active approach, geared to the modern world of cars, planes, films and rapid change. They are wrestling with the paradox that the world is three-dimensional, and you can move about in it and it exists in time, while their pictures are flat and fixed. They are doing all sorts of innovative things: they introduce stencilled lettering which apes the flatness of newsprint; they add joke shadows to make it look as if nails have been driven into their canvases; they mix sand and grit into their paint. They want a new kind of realism, not illustration. Then in 1912 there is an epiphany. Instead of painting, say, a newspaper, or a wine label, or a chair, it occurs to them to glue a page of a real newspaper, or a real wine label or a facsimile reproduction of a chair seat, onto their pictures. All of a sudden, the age-old relationship between the subject and the artist’s representation of it has been turned upside down and inside out. Instead of trying to imitate something with paint or pencil, you stick it on the picture.

The ‘invention’ of collage by the Cubists is one of the most scrupulously analysed moments in the history of art. The story usually begins with Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning, which was made in May 1912 and includes a printed reproduction of a caned chair seat, stuck onto a Cubist still-life painting. It is often described as Picasso’s first collage. The baton then passes to Braque, who pasted pieces of paper bearing a printed wood-grain design onto a still-life drawing to make the first papier collé (‘stuck paper’), Fruit Dish and Glass, in the autumn of 1912. Picasso embarked upon a series of his own papiers collés in December 1912. Other Cubist artists, such as Juan Gris (1887–1927), followed their lead and added their own individual twists to the process: Gris stuck a mirror onto one painting and an engraving onto another but invited the buyer to swap it with a photograph of himself if he preferred. The Italian Futurists, the Russian Cubo-Futurists and Suprematists, and later the Dada artists, observed these developments with keen attention and took them in different directions. Braque and Picasso also made three-dimensional assemblages, which had a profound effect upon the development of twentieth-century sculpture. Even pure painters, particularly the Cubists, made paintings that looked like collages. Poets, writers and musicians also adopted the cut-up approach.

There is much literature on this watershed moment in art, largely focused on which one made which step, Picasso or Braque, and exactly when. In his celebrated essay ‘The Pasted Paper Revolution’ (1959), Clement Greenberg stated ‘Who invented collage – Braque or Picasso – and when is still not settled’. In his landmark study of Cubism, John Golding noted that Picasso ‘invented collage’ while Christine Poggi, in her detailed account of Cubist, Futurist and Dada collage, tells us that Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning ‘has acquired legendary status in the history of art as the first deliberately executed collage’. Another exhaustive account of Cubist collage and its aftermath, Brandon Taylor’s Collage: The Making of Modern Art (2004), begins with the chapter ‘Inventing Collage’.”

Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage by Patrick Elliott is published by National Galleries Scotland, priced £25.00

Victoria Williamson follows up her critically-acclaimed debut novel The Fox and the White Gazelle with The Boy with the Butterfly Mind. BooksfromScotland caught up with her to hear more about her writing journey.

The Boy with the Butterfly Mind

By Victoria Williamson

Published by Floris Books

Hi Victoria, thanks for speaking with us today. Could you tell us a bit about yourself and your career so far?

I’ve wanted to be a writer ever since I can remember – that’s definitely my parents’ fault for reading me so many stories and taking me to the library every week before I was even old enough to walk! I started writing my first novel – an animal story – in my late teens, which turned into a very long trilogy that I didn’t complete until I was well into my twenties. It wasn’t bad for a first attempt, but it certainly wasn’t publishable.

My teaching work ate up a lot of my writing time for a good few years after that, but as I had plenty of adventures in Africa and China, as well as here in the UK, I’m certainly not complaining. It was very good experience, and I now base a lot of my characters’ voices on the children that I’ve taught over the years.

I’ve been working as an author full time since The Fox Girl and the White Gazelle was released, dividing my time between writing, editing, visiting schools, and running creative writing classes. There’s always lots to keep me busy!

Were there any authors that really inspired you when you were starting out?

I read widely as a child and as a teenager, so my work was influenced by a huge range of writers of different genres. I particularly enjoyed fantasy stories such as The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R Tolkein, horror stories by James Herbert, science fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin, animal stories by Richards Adams, humorous books by Terry Pratchett and Douglas Adams, and the classics by Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte. That’s a rather confusing collection of influences, so it took me quite a while to decide what kind of stories I wanted to write. Like many authors, I was drawn back into the world of children’s fiction by J.K Rowling’s Harry Potter series, so if I had to cite one defining inspiration, it would definitely be hers.

Could you walk us through the method you use for writing your books?

I used to spend a lot of my time plotting out everything that was to happen in a book in minute detail, but these days I’m a bit more relaxed about letting the story unfold naturally as I’m writing it. Now I tend to loosely follow the five-point narrative structure of exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and resolution, which helps give shape to a plot, without being too prescriptive. I’ve found that the most important thing is character voice, so as long as I’m clear about who the characters are and what they want before I start, they generally drive the plot forward naturally themselves without every detail needing to be planned in advance.

What’s your favourite thing about being a writer?

Writing books! I know that might seem obvious, but a huge amount of an authors’ time is spent visiting schools, talking at festivals, running writing workshops and promoting their work. Although these are also an enjoyable part of the job, they all require a lot of time-consuming admin to organise, and that’s before editorial work to novels waiting for publication is even added in! All of this other work means that finding uninterrupted time to sit down and actually write can be difficult, so when I do get a block of time to work solely on a new book, I really appreciate it.

Tell us about your new book – The Boy with the Butterfly Mind.

The action centres around two main characters. The first is eleven-year-old Elin, whose parents are divorced, and who is trying to be as perfect as possible as she thinks that will convince her dad to leave his new family and come and live with her and her mum again. The second is Jamie, whose parents are also divorced, and who is just trying to be normal despite his ADHD making things difficult for him.

When Jamie’s mum moves to America with her new partner, Jamie is sent to live with his dad. But Jamie’s dad now lives with Elin’s mum, which ruins Elin’s fairytale ending of getting her own father back. Jamie and Elin’s polar opposite personalities create conflict, and when things spiral out of control, they come to realize the only way they can save their blended family is to admit they’re more alike than they first thought.

It’s a story about divorce, blended families, and ultimately, accepting that happy-ever-afters come in all shapes and sizes.

Can you tell us a bit about your research for The Boy with the Butterfly Mind?

A lot of the inspiration for my stories comes from the real-life experiences of children I have taught in primary schools. Many children are members of blended families, and some of them initially struggle with the changes and transitions that a changing home lifer can bring about. Some of these children share how they’re feeling with their class teacher, so I’ve heard a number of real-life stories from them over the years of jealousies, power struggles, arguments, and ultimately acceptance, although nothing as extreme as Elin and Jamie’s story! I’ve also taught a number of children with additional support needs, including ADHD, so I felt it was really important for them to see a child with ADHD portrayed positively in a story that they could relate to.

Is there any advice you would give to aspiring writers?

Don’t write in a vacuum – that’s a mistake I made, and one of the main reasons why it took me so long after writing my first novels to get published. I was re-inventing the writing wheel myself, and making the same mistakes over and over again. If possible, join a writing community to support you on your journey. I’m very lucky that my younger brother has always acted as my beta reader, but it’s also important to be part of a community that includes professionals who can give you up-to-date industry advice, as well as editorial feedback. There are lots of great organisations that support writers, from writing groups, local SCBWI groups, The Book Trust/The Scottish Book Trust, to literary festivals such as Bath and Winchester, where you can not only meet other writers and attend workshops, but you can get one-to-one feedback on your work-in-progress. Writing can at times be a very solitary pursuit, and being part of a supportive community – whether in person or even online on Twitter or Facebook – can make all the difference when the going gets tough.

Lastly, what’s next?

My next work’s still hush-hush at the moment, but what I can say is that it’s Scottish historical middle grade, featuring a famous real-life person. More to follow – watch this space!

The Boy with the Butterfly Mind by Victoria Williamson is published by Floris Books, priced £9.99

Scotland’s visual artists were at the forefront of the cultural changes throughout the 20th century, and Bill Hare has captured their stories in his brilliant new book Scottish Artists in an Era of Radical Change. In this extract, Bill interviews The Boyle Family, the artist collective founded by Mark Boyle and Joan Hills in the 1950s who went on to become central to the counterculture scene in 1960s London.

Extract taken from Scottish Artists in an Age of Radical Change: 1945 to the 21st Century

By Bill Hare

Published by Luath Press

The particular occasion for this interview is the acquisition and display of your Tidal Series at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (currently on display in New Acquisitions at the SNGMA). Maybe we could begin by you giving an account of the making of this important work?

Sebastian Boyle: We all first went to Camber Sands in 1966, which is a very important trip in our work as that was when Mark and Joan made the first resin and fibreglass studies of the surface of the Earth. They had already moved on from making their assemblages to making the first Earth pieces using a grid system to transfer real material onto boards covered with resin. In the demolition sites in west London they were working in, they would find a board, cover it in resin and then transfer the real material from the site – whether that was bricks, stones, twigs, bottles, newspaper, dust, etc – to the appropriate place on the board.

But these transfer pieces were very heavy and had to be flat and Mark and Joan wanted to make larger pieces that presented the details and shape of the surface of the Earth, not just the detritus lying on top. They’d heard about resins and fibreglass and they wanted to experiment with these new materials. They needed somewhere where they would be relatively undisturbed and so a beach close to London seemed a good idea.

So we went there around Easter 1966 and the first Beach Studies were made. We then went back in 1969 when Mark and Joan wanted to make a series of works that included time as being an element in the work. Questions of time and change had been present in the 1960s projection works but the Earth Studies seemed fixed and permanent and they wanted to show this isn’t the case. So Tidal Series is a critical series for us. It introduces time into the Earth Studies and provides a link to the wider Boyle Family project. The series comprises 14 studies made on the same square of the beach after each tide, two tides a day, for a week, showing the constantly changing tide and ripple patterns created by the sand, the wind and the tide.

I would now like to turn to the broader aspect of Boyle Family as an artistic phenomenon. Unlike other artists, you have operated under a number of different names, such as Mark Boyle, Boyle and Hills, the Institute of Contemporary Archaeology, the Sensual Laboratory, through to Boyle Family. What were the reasons for all these name changes?

sb: Initially works were exhibited under Mark’s name, which was partly because when Mark and Joan started out, they didn’t expect to be making a living as artists. They and all their artist friends were sure they would always have to have second jobs to get by. When they started to exhibit in the early ’60s, most art dealers thought it was easier to sell work by a single male artist and, for Mark and Joan, the possibility they could actually make a living out of making art seemed so amazing that it was a battle which they felt they didn’t need to fight. All their friends knew that Mark and Joan were working together as a team. Mark’s name was almost a nom de plume for the two of them. Later in the 1960s, they created the Institute of Contemporary Archaeology and the Sensual Laboratory almost as front organisations to interact with ‘officialdom’ in some way, whether that was to help get permission to work at a site or deal with the police, a film lab or a hire company. Companies didn’t like dealing with scruffy looking artists. So the Institute of Contemporary Archaeology sounded appropriately official for doing the Earth Studies, and Sensual Laboratory was their production company for the projection pieces and later for their interactions with the music business. Then, over time, we shed those cover names and it just came down to the four of us working together and to give a public face to that fact we adopted the name ‘Boyle Family’.

Can I now go back to the beginnings of what eventually would become Boyle Family? Although both of you were originally from Scotland – Joan, Edinburgh, and Mark, Glasgow – you met by chance, or fate, in Harrogate in 1957. Neither of you had much, if any, formal art training, yet you wanted to make art together. What was it that made you feel you could form a creative partnership?

Joan Hills: Passion. I think it was just a sum total of wanting to be together, and working together, and bashing ideas around in the same space for a number of years and this is what came out of it. From the very first meeting we knew that we would be creating something together. He was writing poetry, I was painting, and we were interested in music, jazz, theatre and performance.

sb: You thought you were going to do something creative together but you weren’t thinking that would be necessarily as visual artists. It was a whole spectrum of possibility. Over the next few years you experimented with different art forms and techniques, such as happenings, projections, film, photography and sculpture because you were not sure which techniques and abilities you might need.

jh: Exactly. We wanted to experiment, try things out and see where they might lead. We still don’t know if what we do is art. That issue seems superfluous.

Joan, you and Mark moved to London at the beginning of what would later be known as the ‘swinging ’60s’. What was it like for you trying to break into the London art scene then and how did you establish your credentials as radical and innovative artists so quickly?

jh: When you were in it, how did you know when it was starting to swing? You didn’t. You were just leading an everyday life and still interested in the things that you were interested in, like going to galleries, listening to plays on the radio. If anything like the Theatre of the Absurd plays came to the Royal Court, we would go and try to see them. We were extremely interested in Beckett and seeing everything that was possible. There weren’t hierarchies that you had to get through. The old ICA on Dover Street was a place that people went to and hung around in because they were interested in pictures or writing or communication. We went to some of the shows and talks and met a few people.

sb: It was a small scene – I remember that you and Mark would say that when you were putting on an event, slightly later, in 1963–4, that you would call up 20 or 30 contacts and friends who were interested in what you were doing and who would come and support you – and vice versa. Whether it was at Better Books bookshop, the ICA, Signals, or, what did you say, Gallery One or Gustav Metzger’s event with the acid at the South Bank?

jh: That’s right.

sb: You weren’t really looking to establish yourselves as radical and innovative artists, were you? You were just trying to make work?

jh: No, we were just trying to get on with our lives.

sb: I think 1963 was really quite a turning point. Somehow you got the show at Woodstock Gallery under Mark’s name. You also went up to Edinburgh to visit your parents, taking slides of the assemblages with you and went round to see Jim Haynes who had started his paperback bookshop. He had a gallery in the basement, didn’t he?

jh: He wanted very much to get the things down into the basement gallery but some of them were just too large to go down the staircase. It was his suggestion that I take the slides round to the Traverse Theatre, which was in a tenement on the Royal Mile and when I got there, they were preparing for their first production at the festival. That’s when I first met Ricky Demarco. They didn’t have a gallery but he was very enthusiastic about what they were going to be doing and thought it would be great to put on our show at the same time in a room upstairs. So that was the beginning of the Traverse Gallery.

sb: It was in doing the exhibition during the festival that you met the artist Ken Dewey who’d been asked by John Calder to put on a ‘happening’ as one of the events at the international drama conference at the McEwan Hall.

jh: Yes. It was a very conflicting period for drama because many people thought that British theatre and drama in London were pretty superb but we felt that more exciting things could happen. Ken Dewey brought that out in all of us.

sb: Calder had asked two American artists, Alan Kaprow and Ken Dewey, to come over and do events to mark the end of the conference. Dewey worked collaboratively, particularly with local artists, and he must have thought that you and Mark were good people to get involved with his ‘happening’ or event. The event they put on, In Memory of Big Ed, was really the first British performance art event that went out into the wider public consciousness. It caused a huge furore because it had involved a nude model being taken across the balcony and was on the front page of most of the national papers. Questions were asked in Parliament and the police prosecuted Calder and the model. It caused a major scandal, but one unexpected consequence was that you were then the artists who’d put on ‘that’ event in Edinburgh. It wasn’t planned but it gave you a bit of a name and meant you were able to put on more events in London and get more people to come and see them.

jh: It didn’t feel as rapid as that at the time, but I’m sure these things counted. That’s absolutely true.

During that period of great social and cultural upheaval in post-war Britain, you were regarded as a vital force within the British Counterculture movement. How did you see what you were doing in relation to all the other changes that were taking place at the time?

sb: I have the sense that Mark and Joan were beginning to find a kind of identity among a group of people at the ICA who were trying to do something different, whether in music, theatre, film or art. It was a group of people who believed in experimentation, aware that they were part of a new generation trying to do something alternative to abstract expressionism or Pop art. They wanted to be grounded in the real world and real experience. Joan had done a bit of work with her film colleagues, working for the Labour party of Harold Wilson.

jh: Inserts for the election of 1964. We never saw Pop art as our thing, we saw it as fantasy somehow.

sb: You felt, though, that it was an exciting time, with Kennedy as President and Wilson talking about the white heat of technological change – the world was changing and Britain was changing.

jh: There’s no doubt that we were aware things were developing in different directions. Society was just breaking down a bit, as far as new ideas were concerned. It was a stimulating time.

Your wide-ranging activities during the 1960s such as your initiatives in the area of happenings and light projections have had a profound impact on the development of both British art and popular musical entertainment. Looking back, are you surprised that this aspect of your work has been so influential?

jh: No, because in the days of going to dances and things in the 1950s and early ’60s, ballrooms had glitter balls, music, perhaps a colour wash on a wall and that was it. Suddenly, we were able to create something that came from another background altogether, slightly scientific. In our projection events we were setting up little scientific experiments, which we watched as they developed and then we’d start another one and that would go on top of the first, then we’d fade one out, start another and so on. When we went to the States with Hendrix and Soft Machine, we found the big New York and Californian light show teams were doing something very different. In some ways more commercial.

sb: You weren’t thinking of it as being popular entertainment but an art event. You did some experiments with the projections on your own terms at home, for us, and for friends, then you started doing it on a wider scale, developing projection events such as Son et Lumière for Earth, Air, Fire and Water in art spaces, before you were asked to do a projection event, at the first night of the London underground club, UFO. I think it is important to say that UFO wasn’t only a great club and it wasn’t just about the music. It was a great art club. It was a place where theatre and dance groups performed, poets came and read and avant-garde films were shown. It was a meeting place for all sorts of alternative artists from all over the world and, while it became famous for the music and the projections that Mark and Joan were doing, I think that it was also very important as a creative hub. Their projections became the main visual element of the club and the bands who played there wanted these kinds of visuals for their gigs. The psychedelic light show has been credited with being the beginning of the big rock gig stage show with amazing projections and special effects – and Mark and Joan were there at the beginning.

Throughout the 1960s, in your monumental ambition to include ‘everything’ in your work, you took a multimedia, collaborative approach involving theatre, film, sound, music, archaeology and scientific research. Yet, by the beginning of the next decade you were cutting back on this highly varied approach and focusing mainly on what was to become the epic World Series. What brought about this change in artistic strategy?

sb: It wasn’t so much a change in artistic strategy as a change of scale. Up until 1971, Mark and Joan hoped that it might be possible to put on quite large-scale multimedia performances using projections, film and sound and at the same time make progress with the World Series and other Earth Studies projects. Indeed, the idea was that these events could be put on at museums to coincide with our exhibitions and that it would be an interesting way of showing the range of our interests, combining exhibitions maybe with our concerts with Soft Machine and contemporary theatre or dancers such as Graziella Martinez.

So the exhibition that launched World Series at the ica in 1969 was billed as being by Mark Boyle, the Sensual Laboratory and the Institute of Contemporary Archaeology, bringing together the Earth Studies, projections, events, body works and sound pieces. And Soft Machine did a gig with Boyle Family projections during the show and during the following exhibitions at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague and the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter near Oslo. The combination of the exhibitions and the concerts was great for us, the museums and I think for Soft Machine, whose members liked playing in venues that weren’t the usual rock venues and festivals. It would have been great to have kept it going. Unfortunately, we then had a bad experience in Berlin in 1971 at an alternative culture festival, where we were putting on an exhibition, Soft Machine gig and a performance piece Mark and Joan had been developing called Requiem for an Unknown Citizen. This was an event piece studying society at large using theatre, random films, sounds and projections. The festival turned out to be a bit of a fiasco and we hastily performed Requiem instead at the De Lantaren Theatre in Rotterdam. This experience, coupled with the problems of having a theatre group and the financial problems it posed, led to the realisation that it wasn’t going to be possible to have a large team without major funding. Mark and Joan were still interested in making multimedia, multi-sensual work but the team was limited to us as a family and the presentations were kept on a smaller scale within the exhibitions, showing film installations before video became widely available to artists. There was a shift to the Earth Studies and the World Series in particular but we have always thought that the projections, films, sound works and happenings are part of our continuing overall body of work.

Maybe we should now concentrate on the work with which Boyle Family is most identified, the World Series. Could you tell us something about the circumstances that brought this mammoth project into being?

sb: After making the first Earth Studies in Camber Sands and then working on sites in the area around our flat in Holland Park, Mark and Joan wanted to do a London Series but, as they couldn’t drive, this was approximately a two square mile area of west London, which we could all walk to. Then we had to leave that flat as it was being knocked down to clear space for Shepherd’s Bush roundabout and Mark and Joan realised they couldn’t start a new London Series each time we moved and that, rather than do a British or European Series, they could expand the Earth Studies project to be a survey of the whole of planet Earth. The Americans and Russians might have been racing to get man to the moon but we could undertake our own study of the Earth. For the World Series, it was decided that 1,000 sites should be selected by using the biggest map of the world that we could find, blindfolding people, and then asking them to throw or fire darts at this map. We would then go to these sites and study them.

You must have realised that 1,000 sites randomly scattered far and wide across ‘the surface of the Earth’ would never be completed in any of your lifetimes. Thus you would have to be selective as to what you could accomplish. On what basis is the selection of sites made?

sb: No, Mark and Joan really did think that they were going to be able to do it in their lifetimes! They wrote in the catalogue for the ICA show that it was a 25-year project and that they could do 40 sites a year. We realised pretty quickly that it wasn’t going to be possible, probably when we went to The Hague in 1970 to do the first site and realised how much work was going to be involved. I think we’ve undertaken and completed approximately 20 of the 1,000 sites. Each one is a bit like making a short film – it’s a major undertaking. Of course, all the other works we’ve done have in a sense been helping us fund and make the World Series project. Quite often, the selection of which site we will do ties in with an exhibition. For example, while we were having a show in Oslo we went and made works in Norway and we made the Sardinian one for the Venice Biennale in 1978.

Your aim is to replicate these various sites as accurately as possible with80 out ‘any hint of originality, style, superimposed design, wit or significance’. When you’re in the process of making a World Series piece, what are the factors that allow you all to feel that you have fulfilled this demanding aim of absolute exactitude and objectivity?

jh: We use larger and larger maps to ‘zoom’ in to a site. Eventually, we throw a metal right angle in the air and where that falls is the first corner of the piece. We extend that six feet and work on that, and there’s never any question of saying, ‘it would be better over here or over there’. You couldn’t improve on what you get in a random selection.

sb: We know that it’s not possible to be absolutely exact and objective but we’re trying to be as objective as we can. The main thing is to take ourselves out of the site selection process. We then try and figure out how we are going to do it, whether it’s going to be one of our resin Earth Studies, or a film or video work that we’re going to make, or if there is some other way of doing it. I am not sure we ever feel we have fulfilled the aim of absolute exactitude and objectivity. Mark and Joan made a list of possible studies we were going to make at each site. We try to complete as many things on this list as possible, which includes making the actual study of the six-foot square, studying examples of animal and plant life on the site, the weather and what we call ‘elemental studies’ of the major types of rock and earth in the area. We include studies of ourselves in the project because we have to acknowledge that we are not neutral observers – just by being there we are having an effect on the site, so we include ourselves as active agents. We’ve never managed to complete the whole list.

Boyle Family had a major retrospective exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in 2003. That must have given you the opportunity to see the body of your work as an organic unity. From your point of view, what holds such highly complex and varied work together under the name of Boyle Family?

sb: That was a very important exhibition for us as it gave the British art world a chance to see the range and variety of the work and how it works together. There are all sorts of ideas and concepts that underpin our work. One of the key questions for us is how to look at anything objectively, to see it for itself. Not to look at it to tell a story or fit an agenda or even to make an artwork but simply to see, bear witness, record and maybe begin to understand. Mark and Joan came up with a number of frameworks for how to do this. One is ‘contemporary archaeology’ that we would study the contemporary world as if one were an archaeologist looking at evidence of a past society. Another key to understanding our work is the idea you have to ‘isolate in order to examine’. The question is how are you going to choose what to examine? Are you going to impose your value system, your value judgements, on that process? And how did you come by those values? Our random selection techniques are a way of trying to open up that process. They are far from ideal but they help. It’s not just the surface of the Earth we’re interested in, but everything – human beings, plants, animals, societies, physical and chemical reactions, bodily fluids and so on. We use random selection techniques to try and take ourselves out of the equation, to help us choose and focus on just a minute selection of the infinite number of possible subjects for study.

As artists who, although London based have their roots in Scotland, and over a long career have frequently exhibited north of the border, do you think of yourselves in any way as Scottish artists?

jh: You bet. This sounds parochial but because we have a World Series, that interest takes us everywhere.

sb: We certainly think of ourselves as Scottish artists and if there’s one trait which we see holding Scottish artists together – and maybe all Scottish people – it’s a certain bloody-minded determination to actually just get on with things. Maybe we needed that bloody determination in order to keep on going for 50 years.

This interview was conducted by Bill Hare in 2014 for Scottish Art News, issue 21

Scottish Artists in an Age of Radical Change: 1945 to the 21st Century by Bill Hare is published by Luath Press, priced £30.00

Extraordinary times demand extraordinary novels, and Kristian Kerr finds that James Meek has given us just that in his latest, To Calais, In Ordinary Time.

To Calais, In Ordinary Time

By James Meek

Published by Canongate

It’s hard to begin James Meek’s new novel, To Calais, In Ordinary Time, without suspecting it is an allegory for Brexit. The medieval setting, the cutting of a crimson rose in a young Lady’s garden in the opening scene, the defamiliarised, mannered English all heap on top of that channel port and its centuries of baggage. Calais, pace our current Foreign Secretary, has always been Britain’s crucial pinchpoint-gateway to the continent. It is also this novel’s City on the Hill, the destination of its travellers. It is even, in this summer of 1348, an English port, a recently acquired and still precarious toehold in mainland Europe. Were this work purely a Brexit allegory, Calais could be a symbol of a perpetually bellicose attitude towards our continental neighbours, or a kind of common ground, a site of exchange and beacon of confraternity to which the enlightened are flocking. Or it could be both at the same time, because the best allegories work that way.

However, as Meek told his audience at an excellent event at the Edinburgh International Book Festival on publication eve, this isn’t a book about Brexit per se. It was begun in 2013, as a novel about climate change. Meek found his analogy for universal human catastrophe in the Black Death and, in the six years during which he immersed himself in the fourteenth century, he also chronicled a 21st century distracting itself from global crisis by fervent, tribal, identity crises, matters of great import to individuals and nations but of comparatively small difference.

It has become somewhat of a cliché to say that we live in extraordinary times, and this novel shows that, indeed, other times may be similarly extraordinary. I hope that the ‘Ordinary Time’ of the title is a sly joke on this hackneyed phrase, for, taken literally, it refers to the journey taking place in July, a fallow period in the liturgical calendar between Pentecost and advent and so designated as merely ordinary. Still, a time ordinary in its extraordinariness can tend to help historical fiction bridge the gulf of centuries.

While writing To Calais, Meek also published the Orwell-winning Private Island (2014) about the privatisation of our public services and Dreams of Leaving and Remaining (2019) a collection of essays about Brexit drawn from his writing in the London Review of Books. Both Meek’s journalism and this novel exhibit the same knack for portraiture in the true painterly sense. They present people and characters not only as individuals with particular virtues, faults, beliefs or desires, but they also relate their behaviour to broader paradigms, such as myth or social theory. One of the achievements in the complexity of this novel is to depict people getting on with their own short, challenging lives, wrestling betimes with the “big questions” of national and personal identity, freedom, faith and desire, while all-at-once a cataclysm fundamentally alters the foundations of society. So even if this is an allegory of climate change and barely about Brexit at all, as a novel it also does a whole heck of a lot more.

A score of archers is travelling towards Melcombe harbour in Dorset to take ship for Calais. In the Cotswolds they pick up a number of official and unofficial hangers-on: Lady Bernadine, fleeing an arranged marriage and seeking a reunion with the courtly Laurence Haket, also the archers’ captain; Thomas Pitkerro, a Scottish proctor returning to the papal court at Avignon; Will Quate, a bondsman intending to earn his freedom in service as a bowman; and the elusive trio of Hab, Madlen, and Enker, respectively the swineherd, his sister, and a road-going clip-clopping shod boar. The archers, rejoicing in names such as Longfreke, Sweetmouth, and the misnomer Softly, saw action together in France. Their skill secured the English triumph at Crécy but their service has also bonded them in shared knowledge of dark secrets, which will gradually unfurl and shape their destiny.

The unmissable, most ambitious, and most challenging aspect of To Calais is its language. The novel is narrated in three distinct idiolects, each corresponding to a different social class and a distinct way of seeing, feeling, and being in the world. Berna, the daughter of the manor, speaks a French-influenced aristocratic English, the language of power. Thomas writes (letters, mostly) in the Latinate language of the clergy, a language rich in abstractions that could be quite straightforwardly construed. Everyone else speaks a sort of quasi-Chaucerian English peppered with archaisms. It is a conceit designed to show the social divisions that will be erased by the characters’ journey and, across society, by the Black Death itself.

Comedy and pathos arise from early misunderstandings between people who don’t really speak the same language, but the proximity of the journey brings them to an understanding and empathy, as this conversation between Berna and the maid Madlen about fear shows: