Kim Hawes is a pioneer, blazing a trail in the very masculine world of music tour management. Her memoir, Lipstick and Leather, is released this month, and she has kindly put together this playing list of music that has meant a lot to her over her career.

Lipstick and Leather: On the Road with the World’s Most Notorious Rock Stars

By Kim Hawes

Published by Sandstone Press

Oliver’s Army by Elvis Costello & The Attractions

From their Armed Forces album, the tour I blagged my way onto and where it all started for me back in 1979!

Lost in Music by Sister Sledge

The lyrics of this one really captured how I felt on my first few jobs: ‘I quit my nine to five, we’re lost in music.’ This song helped me feel connected to other people who felt the same way I did about life.

(We are) The Roadcrew by Motörhead

Says so much about life on the road for all of us. And I couldn’t possibly make a playlist like this without including something from the guys I worked with for so long and learned so much!

p: Machinery by Propaganda

This one’s maybe a bit more obscure, but we always played it when leaving a Motörhead gig in Germany. ‘Motor power, force, motion, drive!’ It just captures that sense of being part of a massive show and consequently a massive convoy on the roads.

Tiny Dancer by Elton John

This one reminds me of being on the road in America. It was on heavy rotation on the radio years after its release – still is on some channels! The scene in Almost Famous is pretty in line with what would happen on the tour buses.

Tubthumping by Chumbawamba

Because it was everywhere and for such a long time, it’s become the band’s signature song. Still relevant today as everyone gets knocked down from time to time and might need encouragement to get back up.

Nirvana’s Come As You Are by The King

I’ve always loved this song but Jim’s version, singing it as Elvis, just adds an extra dimension of melancholy and meaning.

Lipstick and Leather: On the Road with the World’s Most Notorious Rock Stars by Kim Hawes is published by Sandstone Press, priced £19.99.

The Museum Mystery Squad has a brand new case to solve when a a blackmail letter and a gravity defying thief find their way to the Space Zone exhibit. Join Edinburgh author Mike Nicholson for an exclusive sneak peek at the latest addition to this cracking series of illustrated chapter books for younger readers.

Museum of Mystery Squad and the Case from Outer Space

By Mike Nicholson

Published by Floris Books

About the Book:

Someone’s sent the museum a blackmail letter threatening to steal a prized exhibit from the brand-new Space Zone. Can the Squad make one giant leap in their investigation, and stop the gravity-defying thief before an out-of-this-world artefact 3,2,1… takes off?

In the Case from Outer Space, the Squad investigate puzzling planets, amazing astronauts and marvellous moon rocks to try to solve their latest mystery.

About the Series:

Some people think that museums are boring places full of glass cases, dust and stuff no one cares about: wrong! In a hidden headquarters below the exhibits there’s a gang ready to handle dangerous, spooky or just plain weird problems: the Museum Mystery Squad.

Techie-genius Nabster, mile-a-minute Kennedy and sharp-eyed Laurie (along with Colin the hamster!) tackle the surprising conundrums happening at the museum. From prehistoric creatures that move and secret Egyptian codes to missing treasure and strange messages from the past, there’s no brain-twisting, totally improbable puzzle the Squad can’t solve.

Young readers aged 6 to 9 will love the riddles, red herrings and big reveals jam-packed into this fun-filled series of mystery stories by Mike Nicholson. The enjoyable extras like wacky facts and activities, as well as zany illustrations by Mike Phillips, will keep amateur detectives entertained for hours.

Museum of Mystery Squad and the Case from Outer Space by Mike Nicholson is published by Floris Books, priced £6.99.

Delores Mackenzie is a troubled, but gifted child, and her gift means she has to take on the biggest adventure of her life. Below is an extract from this magical tale.

The Dark and Dangerous Gifts of Delores Mackenzie

By Yvonne Banham

Published by Firefly Press

Delores always left her escape from the island until the last possible minute. She loved the race along the causeway, competing against the rapidly rising tide, daring the waves to push her off her feet as she dashed through the first slithers of incoming seawater.

This particular afternoon was sharp and blustery, with March winds sending storm clouds scudding along the Firth. Even by her usual standards Delores had left it late, huddled against the wall of the old lookout as she fi nished one more chapter. She stuffed the book in her pack as fat, cold drops of rain burst on the back of her neck. As she turned towards the causeway that linked Cramond Island to the mainland, she saw a dark smudge at the edge of her vision.

‘Can’t be,’ she whispered.

The prickling on her arms told her different. A suggestion of a shadow, an echo of a person long dead, a Bòcan.

‘What are you doing here?’ she shouted. ‘You never come out here!’

The Bòcan darted to the side, almost impossible to track in the storm-soaked light.

Delores swung her pack over her shoulders, pulled up her hood and ran down the steep bank onto the shale. The water was already lapping the causeway. She walked quickly, shoulders hunched, hands thrust deep in her pockets. Faster. Then running. There was a disturbance in the space behind her. Her hood was yanked back, and the neck of her coat was pulled tight around her throat. Something grabbed at her hair, dragging her back but she kept her balance – just.

Delores tried to scream but what little voice she had left was drowned by the cries of the sea birds that hovered on the updraft. Her hood slackened and a dark figure, more solid now, slid behind one of the stone pylons that lined the causeway. A man once, she thought, from its shape, its movements. She waited, watching for the Bòcan to show itself again.

Nothing.

Delores turned again towards the shore, towards home. If she ran hard, she’d make it in a couple of minutes, but her feet were skittering along the stones that were slick with new seawater and the remnants of dead weed. She felt periwinkles crunching under her boots and the corvids that had been feeding on them rose in front of her, making nothing of the violent wind.

Delores sensed something reaching out for her as she raced towards the foreshore. Just a few more metres. She slipped as she hit the turn in the path and slammed down onto her right hip. There was no time to register the pain. Something tugged on her backpack and dragged her a few inches across the rough surface towards the water, scuffing her jeans and the skin beneath. The shock froze her for a moment.

‘What are you doing?’ she screamed into the wind.

‘Let me go!’

Delores flung her weight forward and scrambled back to her feet. The sky had darkened to an inky midnight-blue and the row of white cottages ahead became vivid against it. She took a deep breath and powered up the slipway, her feet sliding back on the sand that was blowing across its hard surface, her legs shaking with effort. She reached the foreshore and raced towards home, the sound of her own boots barely disguising the footsteps gaining on her with every metre. She prayed that her sister would be home, that the door wouldn’t be locked. The handle twisted and she fell in through the door. She reached back to catch it and slammed it shut behind her.

Delores slid down onto the cold stone floor.

‘Could do with some help here!’ she shouted.

Delilah rushed through from the kitchen and threw herself down next to Delores, adding her weight to the door as something pounded and rattled from the other side of the wood.

‘Bòcan?’ grunted Delilah, as the door banged the air out of her lungs.

Delores nodded. ‘Chased me from the island.’ The door thudded into their backs again.

‘Thought you said they never go out there?’ said Delilah, ‘“All that salt”, you said. Wow, Delores, this one’s strong!’ A single violent bang on the door, then silence for a few moments.

Delores put her hand on the back of her neck. When she pulled it away, there was blood on her fingers. ‘It grabbed me,’ she whispered.

‘Grabbed? Where?’ Delilah leaned in to check for damage.

Delores swerved away from her sister and wiped her hand on the underside of her jeans. ‘Probably just wanting to play. Like when I was little.’

‘Play?’ The door thudded into their backs again.

‘This one feels pretty substantial,’ said Delilah. ‘Not like your old imaginary friends.’

‘They were never imaginary… You had them too; I know you did.’ Delores pressed her back into the door, already feeling the bruises in the knobbly bones of her spine.

‘I did,’ said Delilah, ‘but I left mine behind when I grew up, and they never tried to hurt me. This is a bit different from your dolls’ tea parties. You must be sending out some powerful signals to attract this strength of manifestation.’ She took a breath. ‘You know it’s time, don’t you? For you to go to the Uncles?’

Delores felt her stomach fold in on itself. The threat of the Uncles had been looming dark on the horizon for some time, ever since their parents disappeared. Delilah had dropped hints here and there, the odd mention, but she’d known better than to broach the subject full on. Delores knew what was coming. ‘No way I’m going to those creeps,’ she said. ‘Forget it.’

The Dark and Dangerous Gifts of Delores Mackenzie by Yvonne Banham is published by Firefly Press, priced £7.99.

Lindsay Littleson is knocking it out of the park at the moment with her adventure stories for children, and her latest book, Euro Spies, continues that trend. She writes here of why she wanted to write a story that celebrates Europe.

Euro Spies

By Lindsay Littleson

Published by Cranachan Books

My latest children’s novel, Euro Spies, comes out on April 20th and publication day is both an exciting and scary prospect, as this book is a bit of a departure for me. Euro Spies is a spy caper, packed with clues to solve and puzzles to crack. The story’s set in Paris, Bern, Rome, Venice, Vienna, Brussels and Amsterdam, and the first draft was written when we were all stuck at home during the second lockdown. Tired of gardening and struggling to focus on reading, I starting leafing through some old holiday photo albums. Memories of enjoying glorious sunshine, fabulous sights and delicious food in various European locations flooded back, making me feel simultaneously happy and sad. Although I completely appreciated the importance of staying safely at home, I missed travelling hugely and wondered if there was a way to fill the gap.

When I heard from a friend that some European tour guides had begun doing virtual guided walks around various cities and landmarks, I decided to give those a try.

After I’d been on several virtual tours to some gorgeous European cities , I flicked through the notebook I’d filled with fascinating facts about famous landmarks, and wondered if I could make use of them in a story for children.

An idea began to emerge for a spy novel set in several European cities. A spy has vanished, leaving behind a trail of cryptic clues on various landmarks. His colleague, Emmeline Watson, tricks three children into accompanying her to Europe. She is using the kids as cover for her dangerous mission, but the children soon get involved in attempting to solve the fiendish clues hidden by the missing spy.

Once I had a rough plot-sketch, I started to plan the route around Europe my characters would take on their quest. I wanted the route to be practical, time-and-distance-wise, and ended up borrowing the frankly exhausting itinerary that a young backpacker had blogged about online. But I REALLY didn’t want my characters spending hours waiting for buses or having to stand in enormous border control and security queues at airports, so I came up with an alternative means of travel: the Euro Metro, which leaves Glasgow from a halt hidden under St Enoch’s Subway station and whisks my characters around Europe.

Although the inspiration for the clue-solving aspect of Euro Spies came from novels like Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, I was keen for the emphasis in Euro Spies to be on characters and their relationships. Hopefully, the three children come across as relatable, rounded characters. Samia is friendly and chatty, but suffers from fear of failure and has to learn to relax and accept that mistakes are not the end of the world. Frankie is smart and cheeky, but he’s also a young carer and is enjoying the break from his challenging home-life. Ava sees herself as a loner, and pretends she doesn’t want or need friends, until she meets Samia and Frankie!

For my spy story to be truly satisfying, puzzles weren’t enough. I needed readers to care about what’s happened to Ava when she disappears in Rome

When the waiter pointed down the alley, back the way they’d came, the boy turned to Samia and Miss Watson, his forehead creased with worry. “Apparently she left, just after we did.”

Miss Watson’s hand flew to her mouth. “What on earth was she thinking?”

Anger and fear churned in Samia’s stomach.

What were YOU thinking?? You were meant to be looking after us. You left Ava all by herself!!

And I wanted readers to worry about Samia and Ava when they meet a scary stranger in Venice.

But when Samia whirled round, she saw Ava, face pale and strained, walking along the balcony towards her. A few steps behind, floated an eerie cloaked figure in a glittery carnival mask. For a moment, Samia thought she was seeing a ghost, and blinked desperately, hoping the apparition would dissolve into mist.

But the spooky creature didn’t vanish, just kept moving slowly, its red velvet cloak swishing on the tiles, piercing eyes staring through the eye-slits in the mask.

When I sent the first draft to my publisher, Anne Glennie of Cranachan Books, she was full of enthusiasm, and suggested that I should write A Spy’s Guide to Europe to accompany the novel. A Spy’s Guide is a free to download booklet containing lots of IDL activities exploring European countries and their art, languages, food and landmarks. I’ve made a full set of Reflective Reading Task Maps for Euro Spies too, if classes wish to study the novel in more depth.

My big hope for this book is that Euro Spies will inspire young readers to discover more about all the wonderful things Europe has to offer. Post-Brexit, it’s more crucial than ever that young people in Scotland are encouraged to learn other languages and to make connections with our neighbours in Europe, despite all the travel and work barriers that have been erected.

Euro Spies was a joy to write and I’m hopeful that it will be an exciting and inspiring read.

Euro Spies by Lindsay Littleson is published by Cranachan Books, priced £7.99.

David Cameron’s latest novel, Femke, is both an immersive psychological study and literary mystery. Here he writes for BooksfromScotland on the the journey of writing this compelling novel.

Femke

By David Cameron

Published by Taproot Press

When my late friend, the writer Robert Nye, told me he had a hunch I should write a novel about a Dutch poet diagnosed as a sexually deviant psychopath, I might have taken it the wrong way. But I didn’t. I liked the poems of Gerrit Achterberg (1905–1962), and had even attempted – heavily reliant on a Dutch-English dictionary – to translate a couple of them. I did object, however.

‘Robert, I know next to nothing about Achterberg, except that he shot dead his landlady and wounded her daughter and then was committed to a psychiatric institution.’

‘The less you know, the better,’ he mischievously replied, only half-joking. Nye had written a number of successful novels, mostly focused on a character from history such as Sir Walter Raleigh or Joan of Arc’s murderous sidekick, Gilles de Rais, or those about whom history hasn’t all that much to say, such as ‘Mrs Shakespeare’, or characters from literature, such as Falstaff and Faust.

Unlike Nye, I had only one book under my belt at this point – an odd mix of autobiography and fiction called Rousseau Moon, published in 2000 just before I set off for The Netherlands. When I left Scotland, my book was in the window of Waterstone’s and I had just completed a book tour of the Highlands. I thought my destiny as a full-time writer was assured.

But it was another 14 years until my next book appeared. And this was a different work to the one begun in late 2001, partly egged on by Nye. In the end, I went with my own gut instinct and avoided writing directly about the killer poet, Achterberg, but I did create a character, Michiel de Koning, who was a disaffected disciple of Achterberg’s. De Koning didn’t come into the story until after I’d made the move from Amsterdam to rural Ireland. By then I had ditched the novel, which was called Femke from the off, believing that my distance from the book’s location would make it too hard to continue writing. But I was wrong. The insistent voice of the book’s female narrator wouldn’t go away: I had to let her have her full say.

‘Femke’ is a Fresian name that means ‘girl’ – or, in some accounts, ‘peace’, which would be an ironic name for so troubled a character. The odd origin of her story was this… In late 2001, near the entrance of Amsterdam’s Oosterpark and just across the road from the building where I taught English, I glimpsed the face of a young woman walking past with her dog. It was a face that, under the hood of her parka, seemed either darkly alluring or ravaged by life. At that moment I wanted to see the world through her eyes. Shortly afterwards, her imagined voice, speaking about her dog, came into my head: ‘Bibi has what I need.’

Femke is taken up – or chewed up and spat out – as a Muse by an English filmmaker in the first part of the novel, before she becomes acquainted in the second part with the elderly and now rather neglected Dutch poet, De Koning. Theirs is a complex relationship, seemingly of the father-daughter sort but with an edge that suggests she might be the Muse to reignite his poetic career. Perhaps sensing and fearing this, Femke assumes the role of detective and tries to hunt down De Koning’s ‘last – and only – great love’, the enigmatic Madeleine celebrated by De Koning in his sonnet sequence, ‘M’.

Where is Gerrit Achterberg in all this? Achterberg was always obsessed with the search for the lost loved one, and Femke in the novel literally carries out the search for De Koning’s lost love. Achterberg, who was described by the poet-critic Martin Seymour-Smith as the most gifted of the Dutch modernist poets, is a touchstone of poetic seriousness, a reminder of the poetic giants of the past. He took that seriousness to a murderous extreme, which shouldn’t be glamourised – and isn’t, in Femke. His once-disciple, De Koning, couldn’t in the end stomach the extremism of the master-poet. Achterberg’s most famous work is a sequence of fourteen sonnets on the subject of the death of the beloved, given the ominous-sounding title, ‘The Ballad of the Gasfitter’. De Koning’s most famous, and last, work is the twelve-sonnet sequence ‘M’, which charts the story of his tragic love affair through its passionate beginnings, the turmoil of exile, and its ending in madness.

Even writing this, I have to remind myself that Achterberg was a historical figure and De Koning a fictitious one. Never having been a fan of poetry in fiction, I followed Pasternak’s example from Dr Zhivago and placed De Koning’s poems at the end of the novel, for any readers who might be interested. In his highly entertaining poetry readings, Norman MacCaig used to make sly fun of an audience member who had asked him if he ever cried when writing a poem. This would seem to be a risible notion. Yet I did cry writing a poem, and it was one of these De Koning sonnets. Convinced I was playing a clever game, I was caught off guard. Only then did I realise how much of myself I had poured into this character and his Achterberg-inspired poetry – how much of myself I had poured into this book.

Begun in 2001, put aside for a number of years, picked up again and completed, then revised and now due to be published by Edinburgh’s Taproot Press, Femke charts the journey of a young woman who thinks her dog has what she needs, only to realise that she has needs which only other people can fulfil. A modern woman in an ancient role, she isn’t fool enough to be Muse to an exploitative man for long, but nor is she fool enough to disbelieve in romantic love. She is unlikely to have consented to play the part of Achterberg’s, or De Koning’s, lost beloved, but she is (I hope) a character worthy of their words – and mine.

Femke by David Cameron, is published by Taproot Press, priced £14.99.

Janet McGiffin has written an epic historical tetralogy for young adult readers with all four books coming out in a single year. She tells us about her journey to publication and answers the question, why did Scotland Street Press decide to bring out my four books of the Irini of Athens series in one year?

Betrothal and Betrayal (Book 1)

By Janet McGiffin

Published by Scotland Street Press

Poison is a Woman’s Weapon (Book 2)

By Janet McGiffin

Published by Scotland Street Press

Because people binge read. I binge read. Books are so readily available—I order them overnight or download them onto my electronic devices. Especially people who read books on their phones or on electronic devices binge read. I see them on the subway in New York glued to their phones or tablets or actual books. I have no patience for waiting a year for a sequel to come out; I want it now! Then I read the next and the next until there aren’t any more and anyway by that time, I need a rest.

But mostly, these four are coming out in one year because they are one book. It got long because there was so much to say about this amazing, gorgeous Byzantine empress and her world. I sent it off to Scotland Street Press as two books and Jean, Head of Publishing, said, it’s four books. But to me, it was still one book, divided into four parts. The very end of Book 4 (The Price of Eyes) circles back around to the beginning of Book 1 (Betrothal and Betrayal), just like the end of each book circles back to the beginning of that book. It’s Irini’s life. We all live lives that, looking back, we can see how they are divided into separate books, but it’s still one life.

I realized that for me to be true to my vision, that I was writing one story of Irini of Athens, all four parts had to be edited by the same editor and the covers and chapter illustrations had to be done by the same artist. Why? Because in many series that I have read, the later books feel different from the first ones—there’s a different editor or publisher with different ideas for the series so the characters don’t feel the same, or the plots go limp or fizzle out as the author runs out of ideas. I didn’t want that to happen. I wanted the final episode of this fascinating woman’s life to be even stronger than the previous episodes—a hard-told story of how she faces the consequences of her choices with her same determination and courage. I wanted all four parts to refer back to her previous decisions and previous consequences. Happily, Jean went along with this mad obsession and so did Paddy, my so-intuitive editor, and Harry the amazingly talented artist. Jean, with her enthusiasm and impressive ability, set a production schedule, and Harry produced four book covers in about same time as one, as well as wonderful chapter illustrations that would fit all four parts.

But really, how did this book get so long? Because, as I did the research at the Bodleian libraries in Oxford and later at the New York Reference library on Fifth Avenue, I was reading with the eyes of a crime novelist. I’ve always loved crime novels and years ago, I wrote a series of three for Fawcett paperback and then I went on to other work. But I always look for the real reason behind why my friends and colleagues do the odd things that they do, so I looked at the very sparce information about Irini of Athens and thought, why did she make those particular choices? She is accused of murdering her son. I decided that she didn’t do it. But let’s look at the sudden deaths four years apart of her reasonably healthy father-in-law and her husband, putting her on the throne as Regent for her nine-year-old son, the new emperor. Seriously? And then there were the two patriarchs who died a few years apart, letting her install her favourite power-broker as head of the church. Well, good on her, I say! Well done! She did exactly what emperors before and after her did, but they used swords and she used poison. At least, that’s what I say happened. And in these four parts, I spell out why she did it, and how. Ah, the joys of being a fiction writer and not limited to hard facts!

Of course, the real reason that the book got so long was because so much was going on during that century. Irini betrothed her son to the daughter of Charlemagne, broke that off and betrothed herself to the great man himself! What courage. And then she broke it off for obvious reasons which any woman would know, but I spell that out too. She fought Caliph Harun al-Rashid over the long border between their two empires—he who was called a military genius at the age of ten. And then there was Pope Adrian who wanted the Byzantine territory in Calabria and Sicily and had the temerity to instigate a change in dating, from year one being Creation to our present dating. She spotted that as a ploy to control time itself. But what she is most known for is that she brought icons back into churches and homes after they had been banned for sixty-odd years.

My biggest hurdle, and what made the book long, was that I had to populate Irini’s world. Any Scots child who hears ‘King James’ could tell you who else was at his courts. But I knew nothing of who Irini lived among in the Great Palace of Constantinople. Happily, I came upon an online reference cited in many footnotes, the ‘Prosopography of the Byzantine Empire’. It was compiled at King’s College London, and it lists every bit of information about people of that period. I spent one year reading every single listing and figuring out who might have lived when Irini did, and if she could have known them. I found lots of people, and two were very important in her life.

And then there were my three dear colleagues in Greece, whom I have known for over twenty years, who took on scholarly research in Greek that was beyond me, and found swear words, blessings, medicines – and food – of the Byzantines. Over the two years of COVID we skyped every two weeks and they filled my pages with details. After COVID was over, we met again in Athens and ate all the Byzantine food that they had tracked down in the fabulous restaurants of Athens – where Irini was born and where Byzantium is very much alive and well.

Betrothal and Betrayal and Poison is a Woman’s Weapon by Janet McGiffin are published by Scotland Street Press, priced £9.99.

Seizing Power and The Price of Eyes will be released in October 2023.

Though the clocks have gone forward, and Spring is in the air, Wintersong, a poetry collection by Joy Mead is a relevant read at any time. Here she tells us of the inspiration behind the collection and shares poems.

Wintersong

By Joy Mead

Published by Wild Goose Publications

These poems were written in a disturbing and troubling context – an emotional time of absence and loss which also proved to be an opportunity to search and remember. Out of the shadows, the darkness, and often the injustice, the need to lament and mourn goes hand in hand with the special significance of small moments and ordinary occasions.

So the poems attempt to express the poet’s calling and the value of poetry and creativity as they contemplate moments of loss and joy, both in my own life and in the lives of others near and far. And above all else Wintersong is a book with a longing to keep hope alive.

More than human wisdom,

looking is the poet’s charge:

to mark and mourn

death and loss;

to not let things go by

unnoticed; to respond

to the daily miracles, the music

of wind in the trees,

across stones, in the grass,

the shimmer of the willow –

how I see your face

in the darkness of absence.

(‘From within the dark times’)

Awake!

Be gentle as you walk

on the good Earth,

our home and life-giver.

Touch with kindness

all that has being

and shares with you

this sacred space.

Be still and connect

in the silence

what you are

with what you value.

Give attention to life’s littleness.

Contemplate what it means

to honour the small things –

the seeds and sunlight –

that sustain our wider being.

Listen, feel, touch and smell;

think and imagine –

these are sacred acts.

Real life is what it is,

not what you might be told it is.

Watch and never turn away.

Discern what is needful.

We can no longer sleep unaware

nor be silent while others sleep.

May the sound of our own voices

disturb our foolish slumber.

Awake and see!

Awake and tell what you see!

Awake and seek

a beautiful future

for all the Earth

and its creatures.

Winter Song by Joy Mead is published by Wild Goose Publications, priced £9.99.

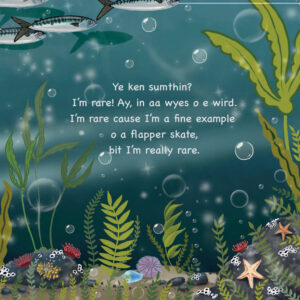

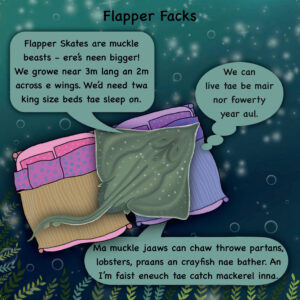

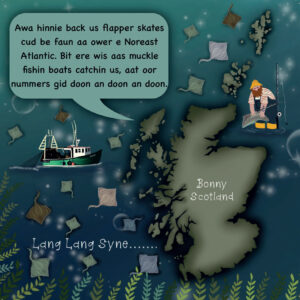

Doric Books are a wonderful publisher celebrating the language of the North-East of Scotland. Here we share their latest children’s picture book on a local legend, Cedric the flapper skate.

Cedric e Flapper Skate

By Jackie Ross

Published by Doric Books

Cedric e Flapper Skate by Jackie Ross is published by Doric Books, priced £7.99.

Patrick Jamieson finds a wonderful and powerful memoir of connection and community in Sally Huband’s debut, Sea Bean.

Sea Bean

By Sally Huband

Published by Cornerstone

These days it’s verging on cliché to interpret women’s nature writing as a cypher for trauma or a means of understanding the human body. Yet it is impossible to ignore an ever-growing genre of Scottish nature ‘memoir’ that uses a re-encounter with the natural world for this very purpose. Equally, it is impossible to deny that this emerging form of nature writing is some of the most exciting work to be produced in Scotland today. Now, we can add Sally Huband’s Sea Bean to that list. Familiar in its form, like the best books of its kind, Huband’s debut works within these parameters to create something unique, weaving together mythology, community and ecology in a profoundly moving story of overcoming disability and rediscovering your place in the world.

Like so many of its type, it begins with a move from the city to somewhere remote. Sally, her infant son and husband move from Aberdeen to Shetland when he’s offered a job flying helicopters to and from the Mainland. They’re swept away by the romantic dream of island life: the freedom, wilderness, community and – most importantly – the house prices. It is a ‘shiny lure of nature’. ‘Lure’, here, is auspicious, and it doesn’t take long for the illusion to be shattered. Biblical winds, electricity shortages and a freedom which soon reveals itself as isolation mean their first few years are a torture. For Sally, especially so. Already ‘unmoored’ by motherhood before their arrival, she quits her job in conservation in the belief she’ll find part-time work on the Isles. She doesn’t. The struggle of caring for a baby on an unforgiving, unfamiliar island surrounded by a ‘hostile’ sea is exacerbated when she suffers two miscarriages. When she manages full term at the third time of trying, the strain put upon her body is so severe that it triggers the onset of inflammatory arthritis, ending forever her dream of walking all along the island’s shoreline. She is bereft, unable to work and unsure of herself or her place.

However, as is so often the case, what seems unforgiving and hostile soon becomes a remedy. Intrigued by the discovery of dead birds on a visit to the beach with her family, Sally takes her first steps into the world of ‘beachcombing’, the search for curiosities or useful objects washed ashore. This proves an able distraction from her struggles, and before long provides purpose: ‘Beachcombing returned me to myself’, she writes in one of many gorgeous turns of phrase. This proves true in more ways than one. Huband continually synonymises the sea with her body, most notably in the image of the eponymous sea bean, the search for which drives Sally as she continues her recovery. The sea bean, she notes, is also known by the names ‘sea-kidney’ and ‘sea heart’ due to its shape. In searching for this drift-seed washed ashore an unnatural environment, Sally is searching for a piece of herself.

After four years on the island they move to a new house in a small community near the shore. Contrary to stereotypes of closed island life, they are welcomed, even by the seasoned beachcomber Tex who paroles the beach each morning in his battered boiler suit. Beachcombing teaches Sally the ‘language of the sea’, both literally and figuratively, as she learns local Shaetlan words such as shoormal – meaning high-tide – or mareel – a type of bioluminescent plankton. She becomes integrated, accepted, a part of something after so many years adrift. As the book progresses this community takes her from the Faroe Islands to Orkney and the Netherlands. Across these journeys Sally learns of the extreme impact the fishing industry has had upon both the marine life and human population around the Atlantic, and when she arrives back on Shetland she does so with renewed purpose. Her return is a homecoming.

On the surface, so far, so familiar. However, Huband’s debut stands out in several ways. The most immediate is its acute focus on the art of beachcombing. Huband’s passion flows through the prose as she breathes life into this lesser-known pastime, revealing its purpose and significance in careful detail, placing it in the historical context of the North Atlantic, and showing what the study of coastlines can teach us about marine pollution. This is no simple ‘cypher’; for Huband the landscape of Shetland – rendered in beautiful description aided by use of the Shaetlan language – is as much a thing to study and conserve as it is a mirror by which to better understand ourselves. Her writing is frank, learned and lyrical, bending effortlessly between hard science and allegory. Neither does the book ever threaten towards navel gazing. Huband is as interested in the peopled landscape as the natural one, providing sympathetic, memorable descriptions of beachcombers she meets along her way, while the rich local histories she weaves into her journeys provide an essential context to the ecological crises she encounters.

Which leads well into the use of the myth. Throughout the book, found objects are placed within stories told and retold across generations. Catshark eggcases figure in a Shetland folktale about Death and grief, while the sea bean, we are told, has been used as a protective charm all along the north-east Atlantic, and an aid during childbirth. However, in the book’s unexpected final chapter, the discovery of a story of Shetland women accused of witchcraft reveals the sea bean to have once been linked to the devil. When Sally further discovers its modern use as a gift for survivors of domestic abuse, the message is clear. This is not simply one person’s story of recovery, but a story about all people, past and present injustices, and what we can learn about this from the shoreline and its gifts. As Sally writes, ‘in these islands it is not unusual for the weather, the body and magic to coalesce’.

In the final moments of the book’s opening chapter, Sally reflects on the remarkable journey beachcombing has led her on. ‘I could never have imagined’, she writes, ‘becoming a dedicated sender of messages in bottles, or the comfort that this would bring’. Equally, she did not foresee that she would become a writer. By the end of Sea Bean it struck me that these two things might not be so different. To write a message in a bottle, or a story for an imagined reader, both are labours of love, sent out without guarantee in the hope they might one day be found and read. I do hope Sally’s message is found and read by many – I’ve no doubt they’ll be better off for it.

Sea Bean by Sally Huband is published by Cornerstone, priced £18.99.

Alexander Hamilton’s cyanotype photography is stunning, and In Search of the Blue Flower celebrates its beauty and technique. Here, he shares with us his first influences and first steps into his practice.

In Search of the Blue Flower: Alexander Hamilton and The Art of Cyanotype

By Alexander Hamilton

Published by Studies in Photography

Leaving a mark; seeking to leave a trace. My earliest serious attempts at art were to observe an object, and to place it onto a prepared surface and to use chemicals and light to reveal and to leave a mark, a trace of its unique existence.

Photography as the artform of the 20th century; in its beginning, the early practitioners used chemical processes to reveal glimpses of the world they saw around them. The early British pioneers John Herschel (1792-1871) and Fox Talbot (1800-1877) called it “photogenic drawing”, using writing paper coated in chemicals to allow them to fix and to hold an image. As a young artist this was what fascinated me. I wanted this direct engagement with the object and the surface I was working with. As an artist it was the action of light on the surface of an object that held my fascination, the excitement of revealing an image.

Where did this all begin? Nothing in my early childhood seems connected to this awakening. I was born of Scottish parents in Chapel Brampton in England. My early years were spent in a simple hut-like building, surrounded by fields and a vegetable garden, until we moved to the urban environment of Northampton. My strongest memories were of yearning to get back to the countryside, making cycle trips back to my childhood home, until one day it disappeared, possibly a consequence of the farmer seeking more land to grow his crops. It was the move to the very north of Scotland, to Caithness in 1962, that that this sense of an artistic awakening began. At the age of twelve, I suddenly felt I was in my correct skin. I was born at last. My life could begin. The world around me appeared familiar and natural. I loved to feel as though I was held between the land and the sky. Anyone who has experienced the Caithness landscape, known as the Flow Country, will recognise the sense of a sublime feeling, of enormous skies and the endless flat land.

The landscape of Caithness became my source of inspiration, and led me to use my Sixth Year art studies to take long walks along the course of Thurso river, to hunt out plants near Dunnet Head and to spend hours in the disused flagstone quarries at Achanarras, a perfect place to seek out good examples of fossilised fishes. The joy of finding a fossil which had laid undiscovered for thousands, if not millions of years had a profound impact on me. This emotional connection to the past and the feeling of seeing something suspended intime and space was at the core of what I would hope to convey in my own creative practice.

I was already certain that this was my path, namely, to enter art college. When I reached my final school year, I applied to various art colleges and was accepted by Edinburgh College of Art (ECA).

My arrival in Edinburgh before starting art college involved a few part-time jobs all to pay the rent on a flat at the top of Leith Walk. Through lack of funds, I discovered a new cheap food, a dessert called Angel Delight. The strawberry flavour was the best one and that became my new diet. This continued until through lack of nutrition, and the detrimental health risks of living in a damp flat, I quickly went down with pleurisy. My choice if I was to be ready for art college was to return home to recover and then start again.

Having recovered, I was back in Edinburgh at the beginning of October 1968, to meet my new fellow travellers on the journey into the world of art. During my first year at ECA a student sit-in started before Christmas 1969, in which classes were disrupted and parts of buildings occupied. The main push was to shift the very outdated curriculum to embrace more experimental artforms. The challenge was a teaching staff that had predominately been selected from past students, thereby perpetuating what you might call the ‘Edinburgh style’, or more broadly, the style of the Scottish Colourists. The idea that you could mix photography on your canvas with paint was viewed with deep suspicion. Out of this flurry of unrest, some minor concessions were made, but generally ECA settled back into its well-trodden ways. The art of Paris had made some gains within the Scottish establishment, but the world of American art, and especially the international Fluxus, was held firmly at bay.

In my second year at ECA, I moved into a flat on Howard Place, opposite the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE). With this move, the botanic gardens were to become my second home. At RBGE I became acquainted with the world of plants, the glasshouses, and the staff. I found a library on the site, one which was unexpectedly open to the public. The librarian suggested I investigate the work of Anna Atkins (1799- 1871), a Victorian woman who recorded seaweed via the medium of cyanotype. This was like a window into a world I had been seeking. I stumbled, with her help, into the world of early photographic processes. Up until the moment of discovering the work of Atkins, I understood all photography as camera-based images, but these were created without a camera. They were rather like the fossils I had found, images somehow conveying the spirit of the object they recorded. These small A4 size images with the deepest blue I had ever seen, the seaweed forms, in white against the blue background, brought memories of the Caithness walks of my childhood flooding back.

This discovery of the work of Atkins did not immediately push me in a new direction, but the window that had opened made me reflect that it might be a potential pathway. Throughout my second year at ECA I was racing around trying to work out what medium to use. As I came to the end of my second year at ECA in 1970, a vital event was to occur, a total work of art experience, an exhibition known as Strategy: Get Arts(SGA). At the time, I did not fully realise that this event would shape my future engagement with the world of art.

In Search of the Blue Flower: Alexander Hamilton and The Art of Cyanotype by Alexander Hamilton is published by Studies in Photography, priced £30.

River Spirit is the latest novel by award-winning author Leila Aboulela. A coming-of-age tale set during the Mahdist War in 19th century Sudan, it marks another success in a glittering career for one of Scotland’s most beloved contemporary writers. Here, Leila sits down with BooksfromScotland to tell us about some of her favourite books.

River Spirit

By Leila Aboulela

Published by Saqi Books

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

I remember my mother teaching me how to read the Qur’an. It was the beautiful script and the rhythms that captured me; I could only understand about half of the words. I mixed up many meanings. ‘Malik’ which means ‘Master of the Day of Judgement’ sounded like the colloquial ‘What’s wrong? Are you alright?’ when addressing a woman, and for a long time this is what I thought it meant. Reading the Qur’an was a step towards memorising it and so both reading and retaining merged. The words and their effects were intended to stay within and not just pass through. It was wonderful to learn that words could have the power to heal, to protect and to sustain.

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your latest novel River Spirit. What did you want to explore in writing this book?

I wanted to explore the historical links between Sudan and Scotland. The Victorian hero, Charles Gordon, who was killed in Khartoum, was Scottish. The story of the siege of Khartoum in the 1880s is thrilling especially as the British relief expedition, Gordon was impatiently waiting for, arrived the day after he was killed! I grew up a walk away from the palace where he would stand on the roof, pointing his telescope north over the Blue Nile. After researching the history, I found it more compelling to tell the story from a Sudanese point of view and especially that of women, who appeared if ever only in the footnotes. I did not find a single first-person account from a woman’s point of view. So, I used my imagination to fill in the gaps. The result is a love story between a woman from South Sudan and a merchant from the North; they repeatedly come together and separate due to the wars, the intervention of others and sometimes their own decisions.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

Tayeb Salih is known for his classic Season of Migration to the North but it’s his earlier, quieter novella The Wedding of Zein which is my favourite. As a student in London, homesick for Sudan, I used to read it on the bus going back and forth to LSE. Even though it was set in a village, and I was from urban Khartoum, it was full of all that I was missing. Zein is the village idiot, abused and derided until a wandering ascetic comforts him with the prophesy that he will marry the most beautiful girl in the village. There is so much harshness and gritty descriptions, that the novella never tips into being a fairy tale. I did not think that leaving Sudan would affect me so much and The Wedding of Zein made me aware of all that was quintessentially Sudanese about myself.

The book as . . . an object. What is your favourite beautiful book? David Roberts was a nineteenth century Scottish artist renowned for his Orientalist paintings. I have a coffee table book entitled Egypt-Yesterday and Today, with page after page of his gorgeous paintings of the Nile Valley, all in his distinctive style inspired by his travels. Bulky temples in the desert with a few tiny people next to them. The sunny, sandy pyramids of Giza. Romantic visions of boats sailing on the Nile at sunset. Roberts did not only paint archaeological sites, there are also lavish crowded street scenes, majestic mosques, souqs and slave girls. The ‘today’ of the title refers to moder day photos of the same locations in smaller frames and it’s fascinating to compare between them and how Roberts depicted the same scene.

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

When I first met my mother-in-law, she gave me a copy of The Far Pavilions by M.M Kaye. I had never read a novel set in India before, and I was enthralled by the romance and the setting. My mother-in-law was English and so, from my family’s point of view, everything about her was unusual and unconventional including the gift of a book! She was the one who introduced me to the Virago Modern Classic and to writers that became important to me like Anita Desai and Doris Lessing.

The book as . . . rebellion. What is your favourite book that felt like it revealed a secret truth to you?

I’ve had a protected Muslim upbringing, married young and never actually lived alone, yet I identified strongly with the vulnerable, lost heroine in Jean Rhys’s Voyage in the Dark. This is such a beautiful novel about loneliness and feeling bewildered in a new place. Reading it in my mid-twenties, it revealed the secret truth to me that even though I was a seemingly settled mum of two, I was floating in the inside.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

I grew up in Sudan reading a range of British writers, Daphne du Maurier, Dickens, Charlotte Bronte, Somerset Maugham. I read them at a time when Britain was unknown to me. Then in my twenties, Britain did indeed become my destination and I had the wonderful experience of living and visiting all the places I had read about. Jane Eyre especially was a favourite as I was growing up. Also, Stan Barstow’s A Kind of Loving made a big impression on me, introducing me to another side of Britain that was rough and somehow more relatable that the drawing rooms and ballgowns of Jane Austen.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

I have been a fan of James Robertson ever since I read Joseph Knight. I love how he connects Scotland to the wider world. He looks inwards but with a deep awareness of the complex links and history. And the Land Lay Still was his brilliant novel of modern Scotland. I will now be going further back in time to ancient Scotland in News of the Dead.

River Spirit by Leila Aboulela is published by Saqi Books, priced £16.99.

The world is running out of water. With supply in the Scottish cities drying up, Aida is forced back home to live with her mum at their rural farm. For now, they are safe with just enough to get by, but when suspicious strangers begin turning up and the water is turned off, Aida and her family are forced to make a terrible decision. The thrilling follow-up to Rachelle Atalla’s debut The Pharmacist, Thirsty Animals establishes her place among Scotland’s most exciting writers working today. Read an exclusive extract from the novel below.

Thirsty Animals

By Rachelle Atalla

Published by Hodder & Stoughton

Do you think they will close the border? I finally asked.

He paused. Maybe . . . I mean, if the government decide too many folk are crossing over, then why wouldn’t they?

Out in the corridor I could see a boy eyeing up the doughnut stand. Lewis, the manager, had fitted a lock to the cabinet a few weeks ago because doughnut-looting had become a problem. But now we were never very sure who was meant to have the key. It was awkward more than anything, especially in the middle of the night, when a customer asked for a doughnut and you had to do the rounds, locating a key from someone who was usually on a break, while acting as if it was the

most natural thing in the world to want a doughnut at 4 a.m. And I was never here when the doughnuts got delivered so I half-suspected that it was the same stale ones that sat in the

cabinet day after day, saved from decay only by their obscene sugar content.

If they do close the border, Aaron said, then they’ll likely close this place too. And the outlet shops.

A laugh snorted out of me. Not exactly a tragedy, though, is it?

My mum and sister are both working at the Mountain Warehouse.

I fell silent then. Sorry, yeah, it’s just, you know . . .

No, I know. They’re awful. Total shit.

*

Are you just passing through? I said, surprising myself for even asking.

The man looked up, holding my eye for longer than seemed natural. My wife has relatives near Fife, and they sponsored our visas.

Have you visited before?

He shook his head, perhaps embarrassed, his eyes shifting momentarily to the floor. And I wanted to laugh: the number of people making it across the border who had never thought to venture into Scotland before.

Are you a golf fan? Aaron asked.

The man stared at us blankly. Sorry?

Golf, Aaron pressed, completely straight-faced. St Andrews, in Fife, is the home of golf.

Oh, the man replied, I never thought to bring my clubs . . . It was as if he was in a fog, disorientated not only by us but by the environment we inhabited. He stared at me, his lips parted. You still have running water, yes?

I nodded.

He licked his lips. I was told that Loch Ness . . . it has more water than all the lakes in England and Wales combined. Is that true?

This wasn’t the first time I’d been asked this. It was like some rumour, an urban legend spreading between those making their way north – maybe it gave people hope. But it was weird. And always Loch Ness. I had seen a piece of art somewhere that highlighted the loch’s depth – deep crevices making their way to the centre of the earth. I tried to visualise the empty and exposed space; it all seemed so unnatural and disturbing. But, if Loch Ness was to be everyone’s saviour, then I was yet to see it come to fruition. The treatment of water, logistics and distribution – those were the terms thrown at us in the government briefings. It had barely rained here in over a year, but this man was looking at me so earnestly, and it felt as if he really needed this, so I nodded and said, Yeah, it’s true. It actually has nearly double the volume of water of all the lakes in England and Wales combined.

We watched them walk away, the boy once again gulping at the water. Slow down, Jamie, the man said. Save some for the rest of us.

Aaron came round to where I was standing and placed his elbows on the counter, cupping his chin in his hands. How long until he realises we’re charging double the going rate for a bottle of spring water?

I laughed but it was half-hearted.

Aaron straightened, something solidifying in his voice. Every time I go into the stock room there seems to be less and less. If they close the land border, how will they get goods in? Will they still let things come by boat, even if they won’t let people?

How the fuck should I know? I said. I’m not the border police. I’ve no idea how these things work.

Have you been seeing all the stuff on social media about what it’s like south of the border? Proper Third World shit . . .

I’m trying not to look, I said. My socials are already a mix of the horrific versus perfectly poised selfies.

How can you not look? he said. I can’t seem to switch it off.

The internet on the farm is chronic, I said. And anyway, terrible things have always been happening to people. We just never really wanted to look at them until now.

It was never so close to home until now, he said.

Thirsty Animals by Rachelle Atalla is published by Hodder & Stoughton, priced £18.99.

Lady Macbethad reimagines the early life of Gruoch, wife of Macbeth, and inspiration for one of Shakespeare’s most memorable heroines. A novel that consciously shifts the dial on male-dominated history, Isabelle Schuler reclaims and celebrates the life of this remarkable woman in an impressive debut sure to delight readers of historical fiction and others alike. We spoke to her to find out more.

Lady Macbethad

By Isabelle Schuler

Published by Raven Books

Congratulations, Isabelle, on the publication of Lady Macbethad. How does it feel having the book reach readers and can you tell us a little bit about what readers should expect from the book?

This is perhaps one of the more surreal experiences I’ve ever had! I come from a performing background as an actress, so it feels so strange to create something and put it out into the ether, knowing people will be interacting with it but not necessarily having the same relationship with the audience that I did as a performer. Weird and wonderful!

Readers can expect a story full of passion, desire, ambition, destiny, betrayal, lust, and a respectable body count.

What is it about the character of Lady Macbeth that you felt deserved further exploration?

I’ve always struggled with the gendered language around ambition in Shakespeare’s play especially in his handling of Lady MacBeth, but when I discovered Gruoch – the real Lady MacBeth – and the incredible life that she had led, all before marrying MacBeth, I knew I had to give this character an origin story. While there is much allusion to Shakespeare’s play (and I did root much of my understanding of Shakespeare’s character in my approach to Gruoch) this is very much an origin story. More than a retelling, I wanted it to be a reclamation of a life that was far more expansive than the depiction Shakespeare gave her.

Lady Macbeth is both a very famous fictional character and a real historical figure. How did you marry those two things in the creation of your character?

I used Shakespeare’s play as a blueprint for filling out the events of Gruoch’s life. I used his characterisation of her as a base, something to work towards and grow into: I think we only just begin to see the seeds of Shakespeare’s Lady MacBeth towards the end of Gruoch’s story. The events of the book end long before the events of the play and map more closely onto a historical account of her life and of the lives of those around her. There are also quite a lot of Easter eggs in the book – nods to Shakespeare’s play – which were enormous fun to put in.

The novel first started life as a film. How was the process in adapting between forms?

It actually began as a TV show, the pilot episode specifically, which meant that though I had the whole series plotted out, I’d only written thoroughly about a tenth of my plot which in turn only covers a third of the events of the book.

When I turned to writing the novel, I found far more freedom in being able to expand her life, meeting her at the age of five and following her right through to her early twenties, which a TV show would not have allowed in such depth. However, I also had to confront the fact that all the research I’d put off in writing the TV show (‘the production designer can sort out historically-accurate sets, the costume designer can sort out the wardrobe’) was suddenly very much my responsibility. I remember sitting down to write the first few paragraphs of the book and wrote ‘she walked across….’ then had to google ‘floors in 11th century Scotland.’ Needless to say, I delayed beginning the novel to fill in my knowledge of the material world of 11th century Scotland. Given that I had already thoroughly researched the events and characters, this final stage did not take as long, thankfully!

You would regularly attend a Shakespeare festival throughout childhood. What do you love about his work? Are there any other Shakespearean characters that you think deserve the novelisation treatment?

I could write entire books about why I love Shakespeare’s plays – his characters, his stories, his poetry – but other more educated, more academic people have done just that far better than I ever could. The closest I can come to a concise articulation is that in all of his plays, Shakespeare so perfectly captures the things that make us beautifully, messily, delightfully, problematically human. He speaks right into the heart of human nature and in so doing has created stories that will survive the test of time, even if the settings become controversial. Society progresses, yes, and technological advances are made, but at the end of the day, Shakespeare’s characters fall and fight for love exactly as we do. They rage against those who wrong them as we do, and plot their petty revenges as we do. They look and sound and move so exactly like us, that I cannot help but be mesmerised by how much I see of myself and my friends and the world around us in scripts that were written 400 years ago.

As for Shakespearean secondary characters that deserve their own story – undoubtedly there are some, but I’ll keep those to myself for now!

You are a bookseller too. Do you think that’s an advantage for a writer in any way?

Being a bookseller comes with the delightful perk of getting to snoop on what other people are reading, which is both informative but can also be a hindrance. I believe that as a writer you have to write what you are authentically inspired by and passionate about, and it can be very easy to see a trend in book buying and want to jump on it. So in a way, I do tend to keep my bookselling and writing hat separate. That being said, being a bookseller is the most delightful career I can imagine having. There are few things I love more than getting excited with people about the stories they are reading.

What are you reading now? What books are you looking forward to reading this year?

I am currently reading Clytemnestra by Constanza Casati with whom I share a publishing birthday! I’m also reading Fair Rosaline by Natasha Solomons which comes out later this year. I have an impossibly long list of books to read but I am looking forward to The Revels by Stacey Thomas which comes out in July, and I am desperate to read Super-Infinite by Katherine Rundell.

Lady Macbethad by Isabelle Schuler is published by Raven Books, priced £14.99.

Born in Minsk in 1981, international lawyer Maxim Znak was arrested in autumn 2020 and sentenced to ten years in prison in 2021. While imprisoned, Znak wrote 100 stories charting 100 days in prison in Belarus today, compiled as The Zekameron. The stories bear witness to resistance and self-assertion and the genuine warmth and appreciation of fellow prisoners. They were sent directly to Jim Dingley, who has worked with Scotland Street Press to bring them to an English audience. In this exclusive essay, Jean Findlay from Scotland Street Press explains why they published The Zekameron.

The Zekameron: One Hundred Tales From Behind Bars and Eyelashes

By Maxim Znak, translated by Jim and Ella Dingley

Published by Scotland Street Press

In early February 2022 I was talking to a friend, a poet, and telling him why we could not publish a manuscript that had come to us direct from a jail in Belarus. Two of our directors had advised against the risk of publishing such politically dangerous stuff. The poet said ‘Well, that is exactly why you must publish.’ Two weeks later the entire world turned against the official Russian and Belarusian state apparatus, so we wouldn’t stick out in our implicit criticism. It was safe to publish – for us, yes, but for the author would this just endanger his life further?

Arguments raged in the office, I maintained that this was a second ‘One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich’, (except that it is 100 days) and our designer said that she had heard that Methuen did not want to publish Solzhenitsyn in the West until he was safely out of Russia. But as is often the case in publishing, someone else did, it was published in New York and then the UK followed suit. Much later the Ukrainian writer, Vitaly Korotich, declared: “The Soviet Union was destroyed by information – and this wave started from Solzhenitsyn’s One Day“.

Maxim Znak is an international lawyer from Belarus – the country which borders Ukraine and which is run by dictator Alexander Lukashenka, one of President Vladimir Putin’s most loyal allies. After Lukashenka’s disputed re-election in August 2020, Znak was gathering evidence of violations of the electoral process when he was arrested and sent to Remand Prison no.1 in Minsk. He was held there from September 2020 until December 2021. This prison has the chilling reputation of being the only one in Europe where the death penalty is still being carried out. It was here that Znak wrote his stories.

These were sent directly to Jim Dingley who had previously translated two books (both Pen Award winners) from Belarus for Scotland Street Press. Both books were written in the Belarusian language, a language banned in Belarus. If caught reading, writing, speaking or singing in the language, people were liable to arrest, detention and punishment. The official language is Russian; it is the language of government, media and education. Znak has written his book in Russian.

The manuscript’s arrival provoked the question: would its publication endanger Znak’s life, or help agitate for his release? But as the brilliant lawyer had by then been sentenced to ten years in a penal colony in the North of Belarus, his wife and sister urged Scotland Street Press to proceed with publication.

As for the book itself, it important to emphasise that it is not memoir, not fact, it is fiction – literature, based on experience. Zek means prisoner in Russian and the title is also a wordplay on Boccaccio’s Decameron, which was a collection of 100 stories from different people escaping the Plague in 14th century Florence. However, Znak’s writing style is closer to Beckett than to Boccaccio. Banality and brutality vie with the human ability to overcome oppression. The tone is laconic, ironic, the humour dry. The stories bear witness to resistance and self-assertion and the genuine warmth and appreciation of fellow prisoners., Znak applies different writing styles in each of his stories and the translation aims to reflect that as closely as possible. The German translation, recently published by Suhrkamp in Berlin, translates it as one narrator in different states of being, more Kafkaesque. It has been well received.

Our first review on the Tweet sphere by Anna Vaught catches it well: ‘It’s a terse account of painful experience, prison, bewilderment; hugely atmospheric and extremely funny – full of dry wit and small biting observations. And what the book says about how we must write because speaking is too painful is so brilliantly drawn.’

As I write, I am told that Maxim has heard news of the publication and he has written.

‘About Scotland [Street] Press (previously I knew only about Scotland Yard) – I am really happy at the thought that the translation is successful. It’s great! Especially in English, the most widespread language of books. Wonderful. Thanks to those who made this miracle possible. I am very grateful. In his Legends of the Arbat Veller has a story about a poet from the mountains who became famous because a free translation was made of his poems by two Russian-speaking lads of Jewish nationality. I’ve forgotten who it was, perhaps Rasul Gamzatov … But the point is that the translations were better than the original – perhaps it’s like that here. That would be good. I’m keeping an eye on the fate of the publication, fingers crossed. Well, how can I keep my eye on anything? The view from my room is limited.’

Well thanks here are due to Creative Scotland and to Pen Translates for funding and to the hard-working team at Scotland Street Press. Above all thanks to the courageous writer, recognised by Amnesty as a prisoner of conscience.

The Zekameron by Maxim Znak, translated by Jim and Ella Dingley, is published by Scotland Street Press, priced at £12.99.

In October 1978, a day that started like any other for Ali Mirsepassi – full of anti-Shah protests – ended in near death. He was stabbed and dumped in a ditch on the outskirts of Tehran for having spoken against Khomeini. In The Loneliest Revolution, sociologist and activist Mirsepassi digs up this and other painful memories to ask: How did the Iranian revolutionary movement come to this? How did a people united in solidarity and struggle end up so divided? In this extract, read Mirsepassi’s first-hand account of his remarkable near-death encounter.

The Loneliest Revolution

By Ali Mirsepassi

Published by Edinburgh University Press

Tehran, 1978

A fall day in 1978 forever altered my life. A day that started like any other tore asunder the life I had worked years to build for myself and my country. For the past forty years, the ghost of that fateful day has trailed my shadow. Today, March 5 2020, as I write these words in the early morning light, sitting in a café on Bleecker Street in Manhattan, the shock of that day still thrums in my mind like a buzzing broken record, while the corresponding images, dark and painful to behold, flash uncontrollably before my eyes.

I have only recently disclosed the details of that day to my family and friends, the people who know me best. It has taken me decades to expose the nefarious underbelly of my political biography to them. Spurring me on has been the realization that burying the ugly face of politics smothers with it hope for change. Neither goodness nor peace can dwell in my mind so long as this darkness remainsundisturbed by the light of revelation. It is time to let the ‘unthought’—those memories I have tried so long to cast into oblivion—speak.

I never intended to hide what happened that day, but the fear that it would overtake and distort memories of my precious, if turbulent, youth led me to push it out of my mind. After all, this event transpired just as I and countless other Iranians were on the cusp of realizing the impossible: toppling a police state indifferent to our wills, hopes, and ambitions. I could see the freedom we had so long been denied materializing as protestors poured daily into Tehran’s city streets. Everything I had hoped for, social change on an unimaginable scale directed by and for Iranians, lay within our reach, and all that remained was for us to seize it. Only as we were turning the corner into a future free of the Pahlavi state’s modern autocracy did I learn, tragically and violently, that our hopes were fodder for a power struggle that would once again sideline and silence us. When people nurture dreams manipulated by the powerful, any one of them might fall victim to their political caprices.

It was late October 1978 when I almost became such a casualty. I had just pulled off what was perhaps my greatest stunt as a student activist. In front of hundreds of my classmates at the National University in northern Tehran, I delivered a speech arguing for the continuation of an ongoing university strike, a direct challenge to a demand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had issued just the prior day. University students all over Iran had had been striking for six to eight weeks by this time, refusing to attend classes and occupying university grounds and buildings, bringing whole campuses to a standstill. Khomeini’s sudden decree that students and faculty should cease the strikes and immediately allow for the resumption of normal university operations confused most of us, and it was only his supporters gathered among us who left his command unchallenged. The crowd settled on the idea of a debate to keep tensions from growing, and I was elected by the pro-strike faction to make the case for keeping university operations halted. I accepted the assignment with a sense of solemn responsibility and considerable anxiety. My speech stressed the need to maintain unity and a common purpose by making political decisions ourselves. We, as students, should think for ourselves, and do what we think is reasonable. I concluded that if we listened to our hearts and minds, we would vote for the continuation of the strikes. My arguments proved a success, and I left the campus relieved the crowd had voted to continue the strike.

As the last spectators trickled out of the campus, a vast and powerful silence settled over the land. I walked toward the vacant lot where I had parked my old red Paykan. Once the car entered my field of vision, a speck dissolving into the horizon, I hurried toward it, guided by an intuition that arrived seconds too late. Before I could even pull the car keys from my pocket, the world came crashing down on me. When I opened my eyes hours later, there was nothing but the darkness of the ditch I found myself in. Several unfamiliar faces peered down at me. Seeing my eyes flutter open, they yelled: ‘He’s not dead!’ It seemed my ability to hear had alone survived the fall. I was completely weak, unable to stand or move, let alone understand what had just happened.

When I next woke, night had fallen, and I was resting in a hospital. The nurse and later a doctor joked that it was divine providence or else extreme luck that had saved me. I had been stabbed twenty-one times and yet survived. A few children playing in a village outside of Tehran, they explained, had noticed a car stop at a local garbage dump. Out from the car climbed a man. He opened the trunk, pulled a body from it, and dumped it into a ditch before quickly driving away. The children informed their parents of this, who immediately called for an ambulance. At the hospital, doctors surveyed the damage done. Some wounds were superficial, others more serious, and a great deal of blood had been lost. But none had been fatal. After being bandaged and recovering from the initial shock, I was released from the hospital that same night. I did not feel mentally prepared to go home and explain the bruises and bandages on my body to my parents. Frail and in poor physical shape, I took a taxi instead to my friend Mozafar’s apartment in central Tehran, where I stayed for several days. And with that, the revolution ended for me two or three months earlier that it did for most others.

The Loneliest Revolution by Ali Mirsepassi is published by Edinburgh University Press, priced £14.99.

Elemental, fierce and full of wonder, the Cairngorm mountains are the high and rocky heart of Scotland. To know them would take forever, to love them demands a kind of courageous surrender. In The Hidden Fires, Merryn Glover undertakes that challenge with Nan Shepherd as companion and guiding light. Following in the footsteps and contours of The Living Mountain, she explores the same landscapes and themes as Shepherd’s seminal work. In this special essay written exclusively for BooksfromScotland, Merryn reflects on her relationship to Shepherd and what it meant to follow in her footsteps.

The Hidden Fires

By Merryn Glover

Published by Polygon

“I set out on my journey in pure love.” So said Aberdeenshire author, Nan Shepherd, in The Living Mountain, her now-celebrated account of exploring the Cairngorm mountains of Scotland. It is also the opening sentence of my book in response, The Hidden Fires. Like her, the journey began in childhood, gazing up at snowy peaks with longing and devotion. Unlike her, my first mountains were the Himalayas of Nepal and North India. So our journeys are different in origins and time, but they meet in the Cairngorms and in mind.

Though she ‘had run from childhood’ in both the Deeside hills to the south-east of them and the Monadhliath range to the north-west, she was in her early twenties before she made her first fateful walk up to their western hem, climbing Creag Dubh. I also was in my early twenties when I first ventured into the Cairngorms, walking over the plateau and down to the Shelter Stone. But I was a fleeting visitor at the time, on a round-the-world trip after six months back in South Asia, discovering Scotland with my new love. He became my lasting love and we made home together here, first in Stirling and then in the Cairngorms area for the past 17 years. And like Shepherd, I was in my early 50s when I began to write about them.

Or, more specifically, it is the time when we both wrote our non-fiction accounts. They loom as a distant horizon in her three modernist novels set in rural Aberdeenshire and published between 1928 and 1933, when she was in her 30s. They come into sharp focus in her 1934 poetry collection titled In the Cairngorms, where her images are as clear and ringing as the light, water and hills she describes. For me, there was also early poetry, and then this landscape became a potent element in my 2021 novel Of Stone and Sky, that reaches its emotional high point in a peak far up in the Cairngorms. So, by the time Shepherd set down her ‘traffic of love’ with the mountains, and I wove mine around hers, we had both been contending with them in walking and words for some time.

But to follow her is no mean feat. It is perhaps presumptous. Dangerous even. As John Lister-Kaye said, “You have to be brave to meddle with a beloved classic such as Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain.” Or foolish. I don’t feel very brave and I do feel the fool quite often, in my writing and my mountain-going, as The Hidden Fires makes eminently clear. I am not an expert on mountaineering in general or the Cairngorms in particular; nor on Shepherd or her extraordinary literature. Others have got those patches well covered and I explore their work with enthusiasm and cite them in my bibliography. But what I have set out to do is tell a new story about both this range and Shepherd’s relationship with it through the lens of my own. And I’ll tell you what gave me the courage to ‘dare the exploit’, to borrow a Shepherd phrase. It was her.

Throughout her life she championed others and cheered them on, both in their walking and their writing. Although there was a long pause in her own publication between her poetry collection and The Living Mountain, she was not ‘silent’. Rather, she edited the Aberdeen University Review for many years, wrote reviews, contributed to literary organisations and supported and maintained a lively correspondence with several fellow authors. As a walker, she regularly took friends, students and children up to the Cairngorms, delighting in their discovery of her beloved mountains as much as in her own. Though she treasured hill-going by herself, she spoke of the pleasure of ‘the perfect hill companion’. Such a person, she wrote ‘is the one whose identity is for the time being merged in that of the mountains, as you feel your own to be’.

I think it would have pleased her to know that she became such a companion for me. Writing my own book felt like a quiet, expansive conversation across time with a kindred spirit and I believe she would have felt joy at another person falling in love with the Cairngorms, at being moved by her work and wanting to share the journey with her – and with others. As I follow her in recounting the ‘grace accorded from the mountain’, I sense her blessing.

Extract from The Hidden Fires: A Cairngorms Journey with Nan Shepherd, Chapter 3: The Plateau