When three people suffer strokes after seeing dazzling lights over Edinburgh, then awake completely recovered, they’re convinced their ordeal is connected to the alien creature discovered on a nearby beach. In The Space Between Us, Doug Johnstone, one of Scotland’s finest crime novelists, moves into new territory with a life-affirming first-contact novel reminiscent of the great science-fiction stories of the past. Meet Ava, one of the three characters connected to the beached alien, in this exclusive extract.

The Space Between Us

By Doug Johnstone

Published by Orenda Books

Ava

She lay in bed and held her breath so she could listen better. Michael lay next to her, his breathing ragged and slow. She wondered about the dosage she’d put in his food. Really, she had no idea. She’d been stealing pills from Rowan’s handbag in the staffroom at work, storing them up. She’d experimented with half a pill in his food for the last couple of nights, then crushed up three in tonight’s casserole, putting in too much garlic to cover it. He berated her about the food, but that was nothing new.

She stared at the swirling pattern on the ceiling, strands intertwined like the arms of some creature. His breathing slowed even more and she felt the baby kick in her belly. Ava was eight months gone, and the baby was letting her know she couldn’t wait much longer. It was one thing for Ava to be controlled and dominated by this monster, another to bring a new-born daughter into this home. That’s why she had to do this now.

Michael turned towards her, face slack in sleep. She flinched. How had it come to this, the sight of him making her cower? She was ashamed of who she’d become, coerced and bullied. No more.

She smelled stale garlic on his breath and stomach acid rose up her throat. If she puked now, he would surely wake up. He was normally such a light sleeper, aware of movement in the room even when he was dreaming. Some primal state of alertness, watching for anything that could threaten his world order.

She lifted her side of the covers, pulse beating in her neck. She listened to his breath as the baby pressed against her kidneys and bladder. There would be time to pee when this was over.

She moved her legs, feet onto the floor, rolled her body in a smooth motion until she was standing. Michael was snoring, hands above his head like he was fighting off birds. She stepped to the door, waited, opened it, heard it creak and froze.

Michael snuffled and wrinkled his nose like he was disagreeing with something. He muttered under his breath and fire flowed from her heart through her body. She imagined herself a marble statue, here in the bedroom doorway for hundreds of years, ignored by everyone. She heard a car in the distance, faint rumble of the boiler downstairs. He snuffled again, moved his arm to the empty side of the bed. His hand moved across the bare covers and she was sure it was all over. She began to think of excuses, needing to pee or she had to take another antacid.

He scratched his nose then shifted his weight and went back to snoring.

She watched him for a long time then crept out of the room and downstairs, feet on the outer edges of the steps because some creaked in the middle. She reached the bottom and walked across the hall to the cupboard full of raincoats and boots. She shifted a pile of old jumpers she’d placed there weeks ago, lifted out a small suitcase full of all the things she would need. Change of clothes, money she’d been siphoning from the shopping, toiletries, the passport she’d taken from the locked drawer without him knowing. She could sort everything else once she was free.

She wore loose pyjama trousers and an old St Andrews Uni sweatshirt of Michael’s, warmer than she would usually wear in bed this time of year, but she would be outside soon. Her feet were bare. She had trainers in the suitcase, there would be time to put them on once she was out.

She went to his jacket hanging near the door and rifled through the pockets. Keys for his New Town office, ID, wallet. She’d read about human-trafficking cases where women were locked in cages or basements, brought there as sex slaves. She wasn’t in that situation but she was still imprisoned by him, by his fucking gaslighting, demeaning her, always making her more reliant on him.

Everyone at the school thought she lived a happy life. Her mum thought she was in love with a wonderful husband. Everything looked good from outside this expensive Longniddry house. How could she be in a prison with a handsome, rich husband and a baby on the way? But that’s what had changed, the realisation that it wasn’t just her anymore. She’d become used to her situation, excused it and normalised it. But a daughter made everything different and she needed to get out.

She found the car key and took the cash from his wallet. She lifted her case and went to the front door. The alarm was on, he always set it before bed. He changed the combination regularly but she’d found the note on his phone with the most recent number. She just hoped it was up to date. She punched in the numbers, cringing at each beep, holding her breath. Waited a moment, expecting the loud wail. But silence. She glanced upstairs, waited for him to shout out or appear.

Nothing.

She opened the door and walked across the driveway to the Mercedes. She unlocked it and cringed again at the blip of the lock, the flashing lights. She placed the case in the passenger seat then took off the handbrake. She didn’t want to start it here with the engine noise, so she heaved at the car, door open, hand on the steering wheel. Eventually the car wheels nudged forward. She leaned her shoulder into the doorframe, felt the baby squirm, did a little pee into her pyjama trousers but kept pushing. She turned the wheel to angle the car through the driveway and climbed in, closing the door as quietly as she could. The car had some momentum on the road and she waited until it was another thirty yards down the street then put her foot on the clutch and pressed ignition. It kicked into life, a ping warning her she didn’t have her seatbelt on.

She pulled it on and drove away, expecting something to happen – Michael to run down the street, the police to turn up, lights flashing. She drove past the big stucco houses, everyone safe and warm inside. She looked in the mirror. The street was dark and she laughed, feeling the release, then the baby kicked.

She turned left then left again, looping round to Links Road. She didn’t want to take the A1, if he woke and found her gone, it was the first place the police would look for the car. She drove along the coast, Firth of Forth to her right. She saw clear skies, stars bulleting the blackness, the full moon. She thought about the distance to that rock, how far she might need to run to really escape.

She reached the Port Seton caravans, beach alongside, moonlight shimmering across the water. She glanced in the mirror again, nervous, still waiting for him to somehow appear.

A bright light appeared in the sky, blazing an eerie blue-green, streaking overhead in front of her. There was a hiss and a roar, a trail of sparks behind. It seemed to be descending, heading for the sea to the east. She couldn’t take her eyes off it. The sound penetrated her skin, the car shuddered and rocked, then she smelled something sweet and salty at the same time, tasted it in the back of her throat. The road in front of her rose up and spun round and she felt dizzy, unable to get her bearings. Bile rose in her throat then she puked down her sweatshirt. She pissed herself as the car drifted and she couldn’t control it, didn’t know which way was up. The car mounted the pavement and went over the grass verge to the rocky beach where it thumped into the sand and she passed out.

The Space Between Us by Doug Johnstone is published by Orenda Books, priced £9.99.

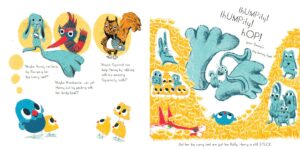

Henny is a baby chick, sweet and fluffy just like her friends. But unlike her friends, Henny has one tiny problem – she’s stuck in her shell! In this gorgeous debut by author and illustrator Aileen Crossley, follow Henny on her journey as she and her friends try to solve her problem – and save the day along the way.

Henny is Stuck

By Aileen Crossley

Published by Little Door Books

Henny is Stuck by Aileen Crossley is published by Little Door Books, priced £7.99.

When carwash employee Davey Burnet takes the wrong customer’s motor for a ride, he sets off a series of events that leads him and his carwash into Glasgow’s criminal underworld. Will he make it out with his kneecaps intact? And will the unpopular DCI Alison “Ally” McCoist be able to help? Squeaky Clean, the debut novel by Callum McSorley, is a pitch-black crime fiction comedy in the mould of Christopher Brookmyre and Frankie Boyle’s Meanwhile. In this exclusive extract, an early morning customer arrives at the carwash with a service request that will change the lives of everyone involved.

Squeaky Clean

By Callum McSorley

Published by Pushkin Press

He was waiting outside the closed shutter at 7 a.m., a Mr Big type: shirt open down to his freezing nips revealing a heavy gold chain nestled in greying chest hair, fag resting between the sovvy rings on his thick fingers, tailored jeans and pointed black shoes, both expensive and dated, the dress of the middle-aged working class gone wealthy. Behind him, a gunmetal Range Rover, engine idling, exhaust smoke fogging the early morning air. Its vanity plate read: V1P MCG.

“We’re no open yet,” Sean said, taking the padlock keys out of his pocket as he arrived at the car wash. Sean was the owner, a wiry and shrivelling forty-year-old with skin like tanned cow-hide, who spent most of his time during winter in the office chaining joints and watching Russia Today. In summer, he took a folding chair out front and sunbathed while the boys worked.

“A know,” the man said. “Sorry fir turnin up so early, pal, it’s just am in a bit ae trouble here.” He took a fast, hard draw on his cigarette.

Sean snuck a look past the guy’s shoulder. The headlights were blinding but Sean couldn’t make out any damage on the four-by-four’s bumper, and it didn’t look particularly mockit either. “It’s a big motor, it’ll cost ye twenty just fir a wash.” Overpricing was a method Sean often used when he wanted a customer to get to fuck.

“Actually am lookin fir a valet an aw. The full hing. Seats shampooed and windies polished. The lot.”

“Ye want the seats cleaned?”

“Aye, how much will that cost?”

Sean laughed, a broken-throated, cackling honk. “At seven in the mornin? Fifty quid, easy.”

The guy sucked the fag down to the filter and tossed it onto the road. “Sure hing, pal.”

Fucksake. Sean wasn’t one to hide his thoughts from his facial expressions. His hard-living eyes, sunk deep in their sockets, rolled in disgust. “Look, the boays will be in at half past, can ye wait that lang?”

“Ye goat a kettle in there?” He pointed at the shutter.

Fuck. “Aye, moan in.”

The guy’s name was Paul McGuinn and you might have heard of him. At least, that’s what he seemed to think. “Call me Paulo. Am fae Brigton, originally,” he said, meaning that although he didn’t live there any more his roots were still in the east end, meaning he was one of the lads, not some posh cunt like his car might indicate. He was rich the way a footballer was rich, not rich the way a Tory was rich. That’s the impression he wanted to give anyway. “Yersel?”

“Possilpark.”

“At least ye didnae say Easterhoose. Fuckin blacknecks!” He laughed and Sean returned a grimace. Up close in the cramped, gyprock office Sean had built at the back of the unit—it had no desk or filing cabinet but did have a couch, television, fridge, kettle, microwave and George Foreman grill—Sean could smell Paulo’s aftershave and a hint of BO underneath. In the harsh light of a bare lightbulb, he could see sweat stains on Paulo’s white shirt, seeping from under his arms and spreading out from the small of his back. Hair gel was slowly being washed down his forehead and onto his red face. “Here, can a smell grass?”

Of course he could: Sean puffed through five or six joints a shift. The earthy stink of weed had soaked into the couch cushions and the carpet (a patchwork of car mats) and seeped into the plasterboard walls like damp.

“Mind if ye roll wan up while we wait? Been oan the gear aw night an I could dae wae chillin oot a bit.” He tapped his nose when he said “gear” and winked.

Sean sighed. “Let us put the kettle oan first.”

Squeaky Clean by Callum McSorley is published by Pushkin Press, priced £16.99.

A Woman of the Sword is an epic fantasy seen through the eyes of an ordinary woman. Lidae is a daughter, a wife, a mother — and a great warrior born to fight. This latest book by Anna Smith Spark, author of the acclaimed Empires of Dust series, delves deep into the complex relationship between warfare, gender and motherhood. In this pulse-racing extract, Lidae protects her family from a frightening home invasion.

A Woman of the Sword

By Anna Smith Spark

Published by Luna Press Publishing

And Lidae was dreaming of a city falling the next night, when it came. The red fires, but in the dream they’re not fires but walls of red, columns of red coming down all over the city crushing things. And then they’re people or huge trees, it’s her own city, Raena, in the country of Cen Elora that is certainly not at the edge of the world and is certainly not a desert, and it’s a city she’s dreamed about before, since she was a child, or the idea that she’s dreamed it before is part of the dream. And sometimes she’s sacking the city and sometimes she’s a victim of the sack and the army attacking her don’t look like people, but she can’t see what they look like.

And she woke, confused, and it came.

From off in the distance, very far off, a dog barked. A sharp angry warning. A noise, outside the house, the click of metal on something. The cow in the byre moved suddenly, a thud of its body, and it lowed. It was afraid for its calf.

Something is wrong, Lidae thought. Something—A memory out of the dream, the dark in their camp one night, out on the flank in the mountains ahead of the rest of the army, too much silence, a sound of metal catching, very distant, enemy swords coming suddenly down on them out of the dark, they couldn’t see, they died, and they couldn’t see. Maerc had died that night, the wound had been in his back, he had been sleeping.

The same silence. The same feeling.

Wake the boys get them up get them up.

‘I hope he was dreaming of good things, a woman, something,’ Acol had said of Maerc, and Acol had been weeping. They burned Maerc’s body as if he’d died gloriously in battle. It had broken Acol’s heart to think of Maerc dead without knowing, sweaty and foetid.

Get the boys up. Get away. Something terrible is coming. I cannot bear to think of them dying in their sleep. A sound of metal. The cow in the byer lowed and stamped. Something terrible is here now. I feel it.

Thieves, she thought. Thieves.

‘Ryn. Samei.’ She clamped her hands over their mouths, tried to wake them but keep them silent, the terror in their faces at her hands over them, her face pressed down to them. Lidae thought: they think I am killing them.

‘Ryn. Samei. Keep silent. Get down under the bed.’ She’d have thought it was Samei who’d have shouted, refused, flailed about. So young, too little to understand anything, but the fear in her voice made him dumb, he did as she ordered him mutely, too frightened of his mother’s voice and her hands that he must think were trying to kill him. Ryn, older, understanding things were wrong, trying to fight her off, ask questions, protest that he had been sleeping. Noise: him pushing her away, speaking.

‘Ryn! Samei! Get under the bed! Get under the bed!’

She opened the chest, there was no time to put on the helmet, she stood in her nightshift and drew her sword.

The blade gleamed in the dark. Hunger stirred and flickered in the metal. Bronze, the colour of the boys’ skin. Polished rich bronze, burning.

In the hilt of the sword there was a red stone. Red glass. In the dark the red seemed to gleam. Ryn cried out. The sword felt so good in her hands. Samei whimpered like a beast. She thought: he thinks I will kill him.

She shifted her grip on the sword hilt. Stood still one pace back from the doorcurtain that divided the sleeping place off from the living place. All the last years falling away. She felt the sword whispering. Light seemed to run in rainbows up the blade. She could remember very clearly the first time she had used a sword to kill someone.

The sound of someone fumbling with the door, trying to shove it open. A voice said, ‘It’ll be barred. Just burn it.’

‘Stay there,’ she hissed to the children. ‘Just stay there, don’t move. Stay.’

The village was too far for help to come. A hill between the house and the village, Emmas had wanted that, because he’d wanted to be apart in silence, after years piled together in the army four to a tent. The dog barked again, furious. She thought: if there is anyone left alive in the village to come. She thought: but that’s madness. This is thieves prowling around.

‘Stay and be utterly silent. Ryn, keep Samei silent. You must.’

The dog barked, far off, and then the barking stopped.

‘He said there was coin here. A widow, he said, with gold hoarded away.’ The door was kicked open. They were going to burn us alive in here, Lidae thought. Cold night air through the door, making the doorcurtain tremble. Footsteps coming inside. On the other side of the wall the cow lowed suddenly and loudly and frantically. Cattle thieves. See? See?

The doorcurtain was ripped aside and a man stood before her, staring at her through a helmet. Dead cold blank eyes, the cold set of his teeth. The sword in his hand trembled. It knew, the bronze sword that he carried, it knew what she was. Lidae’s sword came up took him. His throat, just at the point where the collarbones almost meet together, the red glass in the hilt of her sword smiling at her as the sword went in. The site of the soul, she had heard it said of that place in the throat. He made a noise as the sword took him. She had forgotten the sound of a man dying like this. The sword leapt and her heart leapt.

A Woman of the Sword by Anna Smith Spark is published by Luna Press Publishing, priced £13.99.

Rymour Books have published two books recently that showcase Glaswegian Scots . The following extracts are from two new books both supported by a Scots Language Publication Grant from The Scottish Book Trust. Liberties is a new novel by emerging Glasgow writer, Peter Bennett. Set in the east end of Glasgow during the 1990s, it deals with issues of poverty, crime and family loyalty. The Glasgow Effect is a collection of short stories entirely in the Glaswegian dialect by Ian Spring, author of two books on Glasgow and a volume of short stories in English, The Stone Mirror. Laced with black humour, it nevertheless engages with social issues such as alcoholism, violence and mental illness.

Liberties

By Peter Bennett

Published by Rymour Books

The Glasgow Effect

By Ian Spring

Published by Rymour Books

We approach the Portland Arms, Tam an I. It’s just past hauf past wan. The facade ay the buildin husnae changed a bit since it was built in nineteen thirty-eight. Fae the pavement up tae the bottom ay the windae sills an surroundin the door, the waw is comprised ay black an grey granite. Above the doorway is the sign ‘Portland Arms’ in stainless steel letterin, backlit by red neon light. The remainder ay the waw at the front ay the buildin is constructed wae red facin brick wae stane copin.

Enterin the main door, we immediately arrive in a small vestibule where there ur two doors—wan tae the left and wan tae the right. These two doors were originally, ah wid surmise, put in place fur ease ay access tae either end ay the circular bar held within.

Part ay Tindal’s vision, ye see? Naw well, ah don’t suppose ye dae. Jonathan Tindal wis the proprietor back when he built this incarnation ay the pub in nineteen thirty-eight. It wis tae replace the auld pub ay the same name that stood next door. Bit ay a visionary ye see, auld Tindal. He decided that a pub should be expansive wae loads ay room for patrons tae be seated rather than crowded roon a bar as wis the case in many ay the surroundin pubs ay the time. Accordingly, he promptly acquired the tenement block next door tae the auld pub, demolished it and built wan mare attuned to his philosophy.

Where wis ah then? Aw aye, the two doors. As ah said, there ur two doors as ye arrive, wan at either side. We take the wan tae the right. This takes us intae the Celtic end. The other door as ye may or may no have gathered, takes ye intae the Rangers end.

Hardly in keepin wae Tindal’s vision fur the modern publican then. He obviously never accounted fur the entrenched sectarian divisions ay this city at the time ay inception.

Ah personally, care not a jot fur such segregation. Ma ain faither wis spat oan in the street as he searched fur work when he came oer fae County Donegal in nineteen twinty-three. Ah’ve witnessed countless acts ay violence borne fae the ignorance ay bloody eejits oan baith sides ay the fence. They kin bloody keep it! It is however, a segregation ay choice, ah should point oot. Ah mean, there’s nae doormen staunin there directin folk tae their delegated section an there’s nae real risk involved in croassin tae the other side, as it were. Rather, it’s an arrangement that’s evolved naturally an organically. It should be applauded in a city wae countless pubs affiliated tae either ay the Auld Firm. Everyone is seemingly happy wae the continued modus vivendi an there’s nae mare trouble in the Portland than any other pub. Still though, we’re creatures ay habit, Tam and I, and wae names like Coyle and O’Henry there wis only wan door we were gaun tae use.

Through the door, the customary aroma ay tobacco smoke an insipid, stale beer greets us like an auld friend. A strangely comfortin sensation that comes wae familiarity. Horizontal layers ay grey smoke hing in the air like ghostly apparitions, hoverin seemingly indefinitely as each layer is renewed cyclically by the relentless puffin ay the patrons throughout the bar. Tam goes tae the bar tae order oor drinks. A hauf pint ay heavy an a hauf ay Glenfiddich wae watter fur me. Tam’s usual is a hauf pint ay Tennents lager an a measure ay varyin whiskies dependin oan baith his mood, an his finances.

Lookin aroon the surroundin tables, ah kin observe aw ay the usual faces. At this time ay the day, it’s largely pensioners an unemployed people in fur a couple ay drinks tae while away the ooirs an drudgery ay their day. The sad thing is, occasionally wan ay the faces disappear. People die, life goes oan. Some ay the mare popular characters may even get a commemorative plaque, mounted, in memoriam, at their favoured seat or stool at the bar.

Ah acknowledge the friendly faces ah see; ah nod ay the heid or a cursory wink. Maist offer some sort ay recognition; a raised gless or smile in response. Some however, just stare blankly, unwillin tae enter intae any type ay social interaction. Ah’ve largely gied up tryin tae talk tae the young yins that come in. Maist feign the slightest ay interest in any subject matter ye try tae ignite conversation wae afore buggerin aff as soon as possible. They’re no aw as polite as that though. Some ay the youngsters prefer tae blatantly ignore the opinions held by masel an other elderly people, preferrin insteid tae shun ye entirely. The erosion ay common courtesy an respect fur yer elders in this country ah put it doon tae. It just didnae happen in ma day but there ye go, times change. Mibbe it’s me though; ah mean who’d want tae listen tae an auld bugger like me rabbitin oan. It’s just hard tae accept ah suppose. Ah mean, it wisnae always like this, ye just get aulder an it seems ye become less relevant tae people.

There’s wan shinin light though, ma young grandson. Twinty years auld he is, a strappin big lad. Ma only grandchild an the only real faimily ah’ve goat left. His faither—ma son, died ye see. He goat in wae the wrang crowd an started messin aboot wae the drugs. Died because ay that bloody shite when the boay wis just eleven year auld. Daniel wulnae go doon that road though, ah’m certain ay it. He’s a bright lad, that yin an nae mistake; sais he might drap in an see me the day, in fact.

Wan ay the aforementioned ignorant wee bastarts is oan ma seat when ah get tae it. Tam an I ayeways sit here when we’re in, ‘Dae ye mind shiftin son, yer oan ma seat.’ ah sais tae him.

‘Aye? Ah don’t see yer name oan it.’ he sais, ‘ …ye might huv soon enough when ye croak it though ya auld cunt.’ he sais, laughin wae his pal an pointin tae the plaque at the next table.

‘You’ll huv an embossed imprint ay ma boot oan the cheek ay yer erse if ye don’t sling yer hook ya cheeky wee bastart!’ ah sais tae him. Nae respect these swines! He stauns up lookin as if he’s goat somethin else tae say fur himsel afore pickin up his pint an noddin tae his mate, afore the two ay them bugger aff, movin alang a few tables. Bloody swines.

Ah’m hoachin fur a bloody drink noo efter that kerry oan. Where’s Tam went tae fur them, the Wellpark Brewery?

He’s staunin at the bar talkin tae some big brute ay a fella, bletherin away. Ah’m ready fur gien him a shout but he starts makin his waiy taewards me kerryin the drinks oan wan ay they wee circular trays ye get in pubs, stoappin tae blether tae mare people sittin at the tables he passes oan the waiy. ‘Will you stoap natterin tae every bugger in the bloody place an get oer here wae they drinks.’ ah sais tae him oer the hum ay the many voices in the room.

Efter whit seems like an inordinate amount ay time he eventually gets here, puttin the tray oan the table an sittin doon.

‘Whit took ye?’ ah sais. ‘Ah’m bloody parched.’

‘Stoap yer moanin Coyle! Ah’m entitled tae say hello tae a few people. That’s whit the pub’s fur—socialisin.’ he sais. Ah take ma drinks an decide against pursuin it any further. He’s right, ah suppose. Cannae really argue wae that.

‘Who wis the big fella ye were talkin tae at the bar?’ ah sais.

‘Aw aye, him. Nice big fella, never caught his name.’ he sais.

***

That’s the place, amigo, Scooby Doo hid sed. Ye cannae whack it fur an away day, Imber. Goat the castle an aw that an some stoatin boozers.

JIST THE TICKET

Sae ah wis in Sammy Dows waiting oan him wi a pint o heavy an a wee nippy sweetie wan Setterday efternoon.

Then Cuddy Mackay cams in the door. Ye fur anither hauf, he ses.

Naw, ah ses, ah’m waitin fur a train.

Whaur are ye aff tae? he ses.

Naewhir in particular, ah ses. Ah didnae want tae say Imber. Jist me an Scooby Doo thought we’d git oot o toon.

Weel, no big Scobie, he ses. Ah jist caught him in the Corn Exchange. Sed he’s gaun tae

Paisley fur the

GEMME AT LOVE STREET

An, efter another hauf, Cuddy wis aff tae the Buchanan Galleries fur the Christmas shopping fur the weans.

Ah thoat, whit wid ah dae? Love Street fur the Buddies agin the Jags?

Naw! Nae danger a that, nae danger at aw! Ah’m aff tae Imber, ah thoat. It’s goat the castle an aw that and some stoatin boozers.

Sae ah went across the road but the platform gate wis closin and the train wis puffing away fae the platform.

Nae bother, ah thoat, ah’ll get the next yin.

The Vale wis across the road an it wisnae a bad wee shoap. They hid a big list o whiskies oan a blackboard. Ah’ll check out wan o those, ah thoat. Sae ah hid a Glenmorangie an a hauf o heavy an ah watched the scores coming in oan the telly. Then ah hid a Macallan and it wis time fur the results, Sae ah jist decided tae haud oan an hae anither.

BUDDIES 0 JAGS 0

Sae efter that ah goat oan the train. Thir wis a lass wi a trolley. This is grand, ah thoat. Ah’ll hiv a can o McEwan’s Export. Ah liked the train. It made a sort of clicking sound oan the rails as it pulled past the sheds at Springburn. Sae ah jist shut ma eyes an listened tae it gaein oan.

A minit later thir wis a guy shakin me by the shodder. The train wis stopped deid still.

Is this the six thirty tae Imber? ah asked him.

Weel, this wis the six thirty tae Imber, then it wis the seven forty five back tae Glesca. Noo it’s gonna be the ten thirty five tae Imber agin.

But if ye hiv tae get back tae Imber, pal, ye can get the nine fifty at platform seven.

Weel, thir wis nae chance o that. Ma away day wis banjaxed. May as weel hiv stayed at hame wi a boatle o ginger an a

CHICKEN TIKKA MASALA

Mind ye, Imber’s the place, goat a castle an some stoatin boozers. Never been thir but.

Liberties by Peter Bennett and The Glasgow Effect by Ian Spring are published by Rymour Books, priced £10.99 and £9.99.

Set in the days leading up to a future referendum on Scottish independence, The Darker the Night sees friends David Bryant and Fulton Mackenzie conscripted as unlikely detectives when a Senior Civil Servant is found dead in an alleyway in central Glasgow. Wrestling with their own demons, the men set about trying to discover the truth, and in doing so show that some things are more important in life than politics. In this extract, peer into the mind of Fulton Mackenzie, a reporter on fictional Glasgow newspaper The Siren:

The Darker the Night

By Martin Patience

Published by Polygon

You never know when it’s going to hit you. It’s not like you see it off in the distance slowly approaching and you can prepare yourself. It’s more like a car bomb going off on the street you’ve walked down every day of your life. Everything you held true is going and you’re plunged into a world from which you suddenly fear you cannot escape.

Fulton was returning home after buying eggs from the local shop. A tall, lanky teenager was approaching him on the pavement. His black hoodie was pulled up, his earphones were in, and his head was down, bobbing along to the music. He was staring at the ground so intently it was as if he was tracing ants. If it had stayed that way, nothing would have happened. But a few steps away from Fulton the teenager looked up from the pavement and stared directly at him. It was barely a second but in that moment Fulton’s world was shattered by the furious, rushing return of the past. In that face he saw his beautiful young son, Daniel – the boy who would never grow old. He’d be a teenager now; he would have the same blithe limbs, the same light stubble, and the same smattering of spots on his face. The boy passed by, completely oblivious, as Fulton felt the box of eggs slip from his hand, its lid springing open and the eggs smashing on the pavement, their yellow yolks streaking the tarmac.

It had been seven years since that night. They were on the road to Kilmarnock that rises out of Glasgow onto the bleak, soggy, unforgiving moors. A place where a misstep means you can be up to your neck in a peaty bog. That was Fulton’s recurring nightmare. That was what we he woke up from more nights than he cared to count – the collar of sweat on his neck like a cordon of water that he was about to slip under. The waking up Fulton took as a sign that, deep down, he never wanted to put an end to it all. He’d even recce’d a bridge where he could quickly finish it. One small step and it would be over. But Fulton would be jolted by thoughts of his daughter. He would see the dimples that appeared on either side of Alana’s mouth whenever she smiled. The way she said ‘Dad’ like no other word. It came from the heart rather than the lips. And Fulton knew then he would never do it. Instead he was left living, wrestling with the truth of what had happened that night. Throughout the years only a few shards of memory had revealed themselves.

He remembered his son kicking the back of his seat. It was in three-kick bursts and Dan would laugh and shout, ‘Too slow, you can’t catch me.’ Fulton remembered taking his hand off the wheel and awkwardly reaching back and tickling under his son’s knee. Dan started squealing and twisting in his car seat. And then he would promise he wouldn’t kick any more, only to repeat it a couple of minutes later. But that wasn’t what caused the crash.

Fulton remembered Clare’s stony expression. They had had a massive argument. But what was the cause of the fight? Money? Family? Or something else? No matter how many times Fulton cast his mind back he could never find the truth. It was like a bleeding sore that he constantly picked at and that never healed.

The Darker the Night by Martin Patience is published by Polygon, priced £9.99.

Award-winning Sita Brahmachari has written a beautiful tale for children that explores loss and discovery, legend and reality, settling into a new place, and the coming to terms with sadness. In Corey’s Rock, a grieving family move to Orkney, and ten-year-old Isla finds solace in the nature and folklore, particularly the story of the Selkie. Endorsed by Amnesty International for illuminating the human rights values of family, friends, home, safety and refuge, and beautifully illustrated by Jane Ray, this a book that will stay with readers young and old. Enjoy the extract below.

Corey’s Rock

By Sita Brahmachari

Published by Otter Barry Books

We stand on the grey rock

of our new home.

The four of us.

At sunset.

Four is an even number,

Mum, Dad, me and Sultan.

But everything feels odd.

Stroking Sultan’s head

and watching the surface

where nothing breaks

but waves.

‘Time to say goodbye,’ Mum says.

She hands me petals, and more to Dad.

We raise our hands to scatter them across the sea.

The rose that’s supposed to mean we say goodbye

to Corey.

My brother.

We watch him float away.

A petal for every birthday.

One by one by one by one by one.

Five red petals blur the fire horizon.

‘We’ll call this Corey’s rock,’ Dad says.

I follow the red dots far out to the world’s end,

calling for Corey.

My voice,

the wind’s voice,

the sea’s sway,

all melt away and the petals grow heavy and sink

into the inky depths.

‘Corey,’ I call.

I hit my head against the bedpost.

Through bleary eyes I search for the reason I am here,

where nothing is where it should be,

not even the door.

The windows have shrunk into

painted brick walls.

I lift my head from my pillow.

And now I remember the

half-unpacked trunk in the corner,

below the window with the curtain of yellow daffodils

that only make me feel sadder.

Corey loved daffodils.

I creak down the rickety stairs

where Mum and Dad sit close in the fire’s glow,

steam rising from their cups,

Sultan warming their feet.

Mum reading, Dad sleeping.

The TV is turned to silent.

These are the things we did in our old flat with Corey,

but now they seem strange,

as if we’re pretending he never was.

My eyes are caught by a rolling wave.

Am I still dreaming?

On the screen

seals wash in, swash in, from the sea.

Fishermen rush to the shore,

not with nets but with blankets.

Dad stirs and watches the passing pictures,

searching for the remote. He mutters,

‘Shipwreck…here I am digging up the ancient boats

and now new ones washing in…’

The seals wash up one by one by one by one.

An old man reaches down and pulls back a skin

and underneath,

my breath flies out of me,

there is a boy’s face.

‘Corey!’ I say his name out loud.

Corey’s Rock by Sita Brahmachari is published by Otter Barry Books, priced £8.99.

Scottish Poetry 1730 – 1830 is the new essential anthology of Scottish poetry produced during the Enlightenment and Romantic periods. As well as covering well-known work by the era’s most famous names, the book’s crowning achievement is its detailed and considerate recovery of women poets who have otherwise been written out of the canon, such as working-class poet Christian Milne and Mary Edgar, author of just one slim collection. Read a few of our favourites from the book below:

Scottish Poetry 1730 – 1830

Edited by Daniel Cook

Published by Oxford University Press

‘Bonny Christy’

Allan Ramsay (1684-1758)

How sweetly smells the simmer green!

Sweet taste the peach and cherry;

Painting and order please our een,

And claret makes us merry:

But finest colours, fruits and flowers,

And wine, tho’ I be thirsty,

Lose a’ their charms and weaker powers,

Compar’d with those of Chirsty.

When wand’ring o’er the flow’ry park,

No nat’ral beauty wanting,

How lightsome is ‘t to hear the lark,

And birds in concert chanting!

But if my Chirsty tunes her voice,

I ‘m wrapt in admiration,

My thoughts with extasies rejoice,

And drap the hale creation.

Whene’er she smiles a kindly glance,

I take the happy omen,

And aften mint to make advance,

Hoping she ‘ll prove a woman;

But dubious of my ain desert,

My sentiments I smother,

With secret sighs I vex my heart,

For fear she love another.

Thus sang blate Edie by a burn,

His Chirsty did o’erhear him;

She doughtna-let her lover mourn,

But, ere he wist, drew near him.

She spake her favour with a look,

Which left nae room to doubt her:

He wisely this white minute took,

And flang his arms about her.

My Chirsty! — witness, bonny stream,

Sic joys frae tears arising!

I wish this may not be a dream;

O love the maist surprising!

Time was too precious now for tauk;

This point of a’ his wishes

He wad na with set speeches bauk,

But wair’d it a’ on kisses.

‘To a Gentelman Desirous of Seeing My Manuscript’

Christian Milne (1773-1816)

I’m gratify’d to think that you

Should wish to see my Songs,

As few would read my Book, who knew

To whom this Book belongs.

My mean estate, and birth obscure,

The ignorant will scorn;

Respect, tho’ distant, from the good,

Makes that more lightly borne.

Tho’ I could write with Seraph pen–

Tho’ Angels did inspire,

None but the candid and humane

My writings would admire.

The proud wou’d cry, ‘Such paltry works

‘We will not deign to read;

‘The Author’s but a Shipwright’s Wife,

‘And was a serving Maid.’

Inur’d to hardships in my youth,

If want my age should crown,

I’ll never beg the haughty’s bread;

Death’s milder than their frown.

You’ll think but little of my Songs,

When you have read them o’er;

But say, ‘They’re well enough from her’–

And I expect no more.

‘Melrose Abbey’

John Wilson (1785 – 1854)

It was not when the sun through the glittering sky,

In summer’s joyful majesty,

Looked from his cloudless height;—

It was not when the sun was sinking down,

And tinging the ruin’s mossy brown

With gleams of ruddy light;—

Nor yet when the moon, like a pilgrim fair,

‘Mid star and planet journeyed slow,

And, mellowing the stillness of the air,

Smiled on the world below;—

That, Melrose! ‘mid thy mouldering pride,

All breathless and alone,

I grasped the dreams to day denied,

High dreams of ages gone!—

Had unshrieved guilt for one moment been there,

His heart had turned to stone!

For oft, though felt no moving gale,

Like restless ghost in glimmering shroud,

Through lofty Oriel opening pale

Was seen the hurrying cloud;

And, at doubtful distance, each broken wall

Frowned black as bier’s mysterious pall

From mountain-cave beheld by ghastly seer;

It seemed as if sound had ceased to be;

Nor dust from arch, nor leaf from tree,

Relieved the noiseless ear.

The owl had sailed from her silent tower,

Tweed hushed his weary wave,

The time was midnight’s moonless hour,

My seat a dreaded Douglas’ grave!

My being was sublimed by joy,

My heart was big, yet I could not weep;

I felt that God would ne’er destroy

The mighty in their trancèd sleep.

Within the pile no common dead

Lay blended with their kindred mould;

Theirs were the hearts that prayed, or bled,

In cloister dim, on death-plain red,

The pious and the bold.

There slept the saint whose holy strains

Brought seraphs round the dying bed;

And there the warrior, who to chains

Ne’er stooped his crested head.

I felt my spirit sink or swell

With patriot rage or lowly fear,

As battle-trump, or convent-bell,

Rung in my trancèd ear.

But dreams prevailed of loftier mood,

When stern beneath the chancel high

My country’s spectre-monarch stood,

All sheathed in glittering panoply;

Then I thought with pride what noble blood

Had flowed for the hills of liberty.

High the resolves that fill the brain

With transports trembling upon pain,

When the veil of time is rent in twain,

That hides the glory past!

The scene may fade that gave them birth,

But they perish not with the perishing earth;

For ever shall they last.

And higher, I ween, is that mystic might

That comes to the soul from the silent night,

When she walks, like a disembodied spirit,

Through realms her sister shades inherit,

And soft as the breath of those blessèd flowers

That smile in Heaven’s unfading bowers,

With love and awe, a voice she hears

Murmuring assurance of immortal years.

In hours of loneliness and woe

Which even the best and wisest know,

How leaps the lightened heart to seize

On the bliss that comes with dreams like these!

As fair before the mental eye

The pomp and beauty of the dream return,

Dejected virtue calms her sigh,

And leans resigned on memory’s urn.

She feels how weak is mortal pain,

When each thought that starts to life again,

Tells that she hath not lived in vain.

For Solitude, by Wisdom wooed,

Is ever mistress of delight,

And even in gloom or tumult viewed,

She sanctifies their living blood

Who learn her lore aright.

The dreams her awful face imparts,

Unhallowed mirth destroy;

Her griefs bestow on noble hearts

A nobler power of joy.

While hope and faith the soul thus fill,

We smile at chance distress,

And drink the cup of human ill

In stately happiness.

Thus even where death his empire keeps

Life holds the pageant vain,

And where the lofty spirit sleeps,

There lofty visions reign.

Yea, often to night-wandering man

A power fate’s dim decrees to scan,

In lonely trance by bliss is given;

And midnight’s starless silence rolls

A giant vigour through our souls,

That stamps us sons of Heaven.

Then, MELROSE! Tomb of heroes old!

Blest be the hour I dwelt with thee;

The visions that can ne’er be told

That only poets in their joy can see,

The glory born above the sky

The deep-felt weight of sanctity!

Thy massy towers I view no more

Through brooding darkness rising hoar,

Like a broad line of light dim seen

Some sable mountain-cleft between!

Since that dread hour, hath human thought

A thousand gay creations brought

Before my earthly eye;

I to the world have lent an ear,

Delighted all the while to hear

The voice of poor mortality.

Yet, not the less doth there abide

Deep in my soul a holy pride,

That knows by whom it was bestowed,

Lofty to man, but low to God;

Such pride as hymning angels cherish,

Blest in the blaze where man would perish.

‘To the River North Esk’

Mary Edgar (FL. 1810 – 1824)

In museful mood, how frequent here I stray,

When summer smiles illume the lovely scene!

Sweet river! On thy margin soft and green,

I turn, and oft retrace my winding way;

And often on thy changeful surface gaze,

Where the smooth stream reflects an azure sky,

Red rock, green moss, and shrubs of darker dye,—

Or gayly gleams with bright meridian rays.

Here, scarce a zephyr curves the glassy plain,

And scarce a murmur meets the listening ear:

There, white foam swells the wave, and still we hear

The rushing waters tumblind down amain,

Till, softening in their course, the noiseless tide

Within the enchanting mirror gently glide.

Scottish Poetry 1730 – 1830 edited by Daniel Cook is published by Oxford University Press, priced £12.99.

Karen McCombie’s latest book for children follows Tyra as she moves school and has to make new friends. BooksfromScotland spoke to the author to find out more about her book and her advice for kids in a similar situation to Tyra.

The Broken Dragon

By Karen McCombie

Published by Barrington Stoke

Well done on another book under your belt with the release of The Broken Dragon. Can you tell the readers what to expect from the book?

Readers can expect a short and sweet tale of a dragon-obsessed ten-year-old, plus they’ll learn about Kintsugi – the Japanese art of mending things with gold! It’s all wrapped up in a story of kinship care, where children live with a member of their extended family, when staying with their parents isn’t an option. In this case, Tyra has just moved in with her beloved nan.

Your book explores the challenges of starting a new school. Do you think back to your own childhood and school days when you write your books? What are your go to tips for making new friends?

Due to my family moving around – including a spell in Australia – I ended up going to five primary schools in total. I was already a shy kid and trying to fit in and find my feet at each new school really dented my already fragile self-confidence! What I’d love my younger self to have known are these two short-cuts to getting to know people…

1) Smile, even if you’re feeling wibbly as half-set jelly inside! Not everyone will smile back, but the nice ones – the potential future friends – might!

2) Ask questions or give compliments. Shyness can tie your tongue in knots and make your head feel echoingly empty of anything to say about yourself. But you can always find questions to ask or nice things to say. Something as simple as “where did you get your pencil case?” or “I like your trainers” could be a quick-fix route to bonding with someone.

You also feature the Japanese art of Kintsugi in your book. Why do you think the theme of embracing imperfection is useful for young readers?

Small children operate in their own wee world, but there’s a tipping point of self-awareness at a certain stage of development, where children can start comparing themselves to other people and their achievements. And that can sadly chip away at your confidence if you think you’re falling short! I just wanted to write a story that might help make children think about the fact that quirks and differences can be pretty interesting. A lot more interesting than perfection!

You have now published over 100 books, and before you wrote your books you were a journalist for a variety of children’s’ magazines. Although tech may change, do you think young people’s preoccupations remain the same? How have your readers changed over the years?

Tech aside, the fundamental things that mattered to children and teenagers I wrote for at the beginning of my career 20+ year ago are the same as they are today; friendship joys and woes and family dynamics. Luckily, that’s always at the core of what I write! And my biggest thrill these days is that readers of my best-selling ‘Ally’s World’ series back in the early 2000s are now becoming parents and are emailing me to say they’re starting to read my books to their children. That’s pretty mind-blowing!

How to keep inspired? Are there days when stories will just not come? What do you do then?

Writing is a full-time job, but yep, some days my brain feels more like it’s full of sludge than intricate storylines and zippy dialogue. When that happens, I don’t force it, and turn my attention to sorting out the admin around my job. That’s so dull that I’m soon itching to get back to writing! Oh, and taking my dog out for a walk always helps clear my mind. There’s nothing quite like chasing a frantic Westie who’s chasing a squirrel to get the adrenalin pumping!

What books are you enjoying reading at the moment? What are you looking forward to reading?

I’m a huge fan of short books… as a former magazine journalist and sub-editor, I often spot where longer novels are sagging and how they could’ve been edited to tighten the story up and keep things pacey! So I do enjoy reading quick-read Barrington Stoke children’s books. Recent favourites have been The Journey Back To Freedom by Catherine Johnson (the true story of former slave Olaudah Equiano) and Victorian gothic tale The Mermaid in the Millpond by Lucy Strange.

And I’m also really looking forward to reading Glitter Boy by former teacher Ian Eagleton, after I saw him talk on the ITV news about the book and the importance of having diverse stories in schools . It looks like a really joyous read, and a great addition to classrooms!

The Broken Dragon by Karen McCombie is published by Barrington Stoke, priced £7.99.

An ageing artist, struggling with an unnamed degenerative illness, is inspired by a fresco in Venice to create one last great work. A meditation on love and creation, With or Without Angels is a fictional response to an artwork created by the late Scottish artist Adam Smith, itself inspired by the work of Giandomenico Tiepolo. Read ‘the old artist’s first encounter with the fresco in the extract below.

With or Without Angels

By Douglas Bruton

Published by Fairlight Books

The first afternoon the old artist spent at the Ca’ Rezzonico museum in Venice he saw only one picture – Giandomenico Tiepolo’s fresco of Il Mondo Nuovo, ‘The New World’. He wanted to climb up into the picture, to be a part of that crowd – and I am sure that ordinarily and for his own reasons he did not like crowds. He wanted to be pigment and paint and laid down for all time on a piece of wall. His eyes moved through the work, taking in each individual gathered together on Tiepolo’s fresco. He imagined himself young, a child running excitedly between the legs of the men in breeches and clutching at the long skirts of the women and stopping to stroke the arched neck of the dog – it was a yellow-brown whippet or a greyhoud and a little skittish from his petted attentions. A masked clown glared at him, growled, showing his teeth below a papier-maché hooked nose with wide nostrils and high roughed cheekbones. The old artist stared so hard at the picture that his eyes stung and began to water.

It was quiet in the gallery room – not that he was entirely alone, but there was a church-hush all about him and the people there talked in hot whispers. He lay down on the floor in front of the picture, closed his eyes and slept.

And the light in the gallery shifted, shadows crawling across the floor towards the far wall.

Suddenly there was noise. Music playing somewhere. Maybe the man on the wooden stool with his arms in the air and holding a long wand, maybe he was conducting some street musicians. He would later pass round his three-cornered hat for the crowd to drop pennies into. And cheering there was, and laughter – though the laughter was far off.

He could smell the perfume of the ladies – something with musk in it and flowers, mint perhaps and the sweetened wet earth mint grows in. And the well-dressed men smelled of rosewater, or those wearing the hats of common men smelled of fish and something sour, too, like meat that has hung too long in the sun or like milk when it has turned and the smell of it when the bottle is raised to the nose makes you jerk back as though stung.

And there were dancers somewhere, dressed in carnival masks, or maybe they were juggling coloured wooden balls and the crowd was held, wanting the balls to clumsily drop and at the same time to stay spinning in the air, birling.

The afternoon sun was high in the sky, and the air sweated and itched.

Then he felt something tugging at his pockets – hadn’t they told him that he must be careful of pickpockets? ‘They are quick as mice and slippery as eels. You must keep your wallet close and your hand always guarding it.’

‘Signore, signore, it is done.’

He woke then.

The young gallery attendant was leaning over him, shaking him. There was something gentle in his voice, even tender. Speaking like a lover, almost, and not with any note of censure at this man sleeping at the feet of Tiepolo’s Il Mondo Nuovo.

‘It is time for the gallery to close,’ the young man said, smiling.

With or Without Angels by Douglas Bruton is published by Fairlight Books, priced £9.99.

In Kapka Kassabova’s Elixir, her latest book on her native Bulgaria, David Robinson finds an imaginative history and a fantastic landscape.

Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time

By Kapka Kassabova

Published by Jonathan Cape

THERE is a double-page map at the start of Kapka Kassabova’s Elixir which, with its uncial script, drawn mountains, and places with names like The Dark, The Village of Storks, The Birches, and Valley at the End of Time, will remind Tolkien fans of Pauline Baynes’s map of Middle Earth in Lord of the Rings. An inset map in the same faux-archaic style makes clear that we are in the southern Balkans, not Middle Earth, the Rhodope Mountains not Rivendell. Just over the border to the south is Greece, to the west is North Macedonia. We are in Bulgaria’s Deep South, which to me is a faraway land about which I know almost nothing other than what I have read in the two other books in Kassabova’s Balkan Quartet (this is the third) about her homeland.

So let’s start, as she does, in Empty Village, two kilometres south of Dogwood and five north of Thunder. Like almost everywhere else on the Elixir map, she has named these villages herself. Sixteen pages in, she tells us that Empty Village is really called Leshten, meaning hazel, and light research with Dr Google tells you that Dogwood is really Gorno Dravano and Thunder is really Garmen. This renaming persists throughout the book, but it has a purpose: nothing to do with Tolkien, but everything to do with the imagination, and the repeated overlaying of the past on the present. Strip away some of those layers, Kassabova is suggesting, and you might be able to glimpse a different land altogether, one more closely linked to nature. One where the valleys she is exploring – specifically the Valley at the End of Time, which the very real Mesta River flows through – do indeed offer the elixir of hope.

What kind of hope? Well, look again at some of those chosen double names: Dogwood, The Birches, Chestnut River. Then look at how the book itself begins. For the last ten years, Kassabova has lived near Beauly. An idyllic part of the Highlands, you’d have thought, and maybe it was until the first spring of the pandemic, when swathes of the nearby forest were razed. The local quarry was already expanding and mega-pylons had started marching out of Scotland’s largest power substation. The landscape, which had once enchanted her, had now become so noisy and mechanised that she found it hard to work (‘My blood sloshed like a river jumping its banks’). She needed to get away, to go somewhere the natural world didn’t feel quite as broken.

Southern Bulgaria is, apparently, such a place. A herbalist’s heaven, not only is it one of Europe’s leading exporters of medicinal and culinary plants, but every village seems to have its own expert plant-gatherers, healers and mystics with elaborate spells and recipes for their use. In The Empty Village – once home to 500 people year-round but now to only three – she finds herself living next door to a poet who has spent decades roaming the hills, collecting stories and recording songs. Kassabova sets off from there with the aim of doing something similar for the region’s foragers, healers and herbalists.

It’s not paradise: she’s clear about that. If it was, villages wouldn’t be empty, house prices wouldn’t have shot up a hundredfold in a generation (no, I don’t understand how those two things go together either), there’d be no gangsterism, Roma slums, or high unemployment. The scenery may be spectacular, but personally I’d rather visit the villages around Lake Ohrid, the double world heritage site (both natural and cultural) some 160 miles to the east that Kassabova wrote about in her 2020 book To The Lake. Then again, maybe that’s just me: I’ve always been more interested in history than herbs.

That said, there’s still plenty of history here too, going at least as far back as the Borgomils, those tenth century neo-Gnostics who were mocked for going around carrying two bags, one for books and one for healing herbs. And few groups of people have been quite as tangled up in history’s blues as the Pomak population of south Bulgaria – non-Turkish Muslims who converted to Islam under the Ottoman Empire – whose folk traditions Kassabova explores here.

It’s the Pomaks – persecuted by Communists for trying to cling onto their own customs and before that by their Orthodox neighbours for not being Christian – who know how to ‘bring down the moon’ (naked women at a crossroads at midnight summoning the moon’s power), how to use cuckoo-pint to fight off cancer, and how to conceive (an odd one for Muslims, this, but spending the night in a Christian church named after St George on St George’s Day apparently does the trick). Got a face rash, venereal disease or eye problems? The Pomaks have the very herbs you’ll need, but you’ll also need to know how the spell works, how the bread has to be left for the spirits, why you have to cut the plants from west to east, and what to do with the wheat and salt as you chant the magic words.

I’m a sceptic. Kassabova isn’t. Even in Scotland, where local knowledge of where to find specific herbs has often disappeared, she is a firm believer in the efficacy of herbal cures (and also, she admits, a hypochondriac). In southern Bulgaria, though, knowledge of herbs is deeper-rooted. If you want to meet the Pomak healers, work with the herb dealers, or find out the folklore behind the plants, it seems relatively easy to do so. Kassabova is also a good listener, even to women who tell her they get their secrets from ‘healers from the stars’.

So why, in the village of The Birches, does she admit that ‘all the women I met were taking tranquillisers or anti-depressants’? She would doubtless argue that this is because Communism broke the link between the land and the people, because the Pomaks’ forests have been cut down, because they were made to work on collective tobacco farms and stripped of their Muslim names and forbidden to wear their traditional dress. Yet if Kassabova can find a healer there to wave an egg in front of her face and cast out negative energy, so could the rest of the villagers. Why don’t they do just that instead of going to the doctor for tranquillisers? Come to think of it, why did those medieval Borgomils, for all their knowledge of how to use plants for healing, have a life expectancy less than half of our own?

Yet, when you’ve finished the book, look again at that double-page map. Its place-names may have been changed from those on any atlas, but nothing has been lost and much gained. Somehow, in an alchemical process that involves stirring together vast knowledge of plants, history, spirituality, magic and local folklore, Kassabova has mastered the art of tying together the inner and outer landscapes of southern Bulgaria. Elixir may well suffer the fate of being filed under ‘travel’ in your local bookshop, but it is far more than that – indeed, it makes those books whose maps use places’ actual names appear positively anaemic by comparison.

Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time, by Kapka Kassabova is published by Jonathan Cape, priced £20.

For her first book, The Ethical Carnivore, Louise Gray wrote about only eating animals she killed herself in order to explore the impact of meat on climate change. For her second book Avocado Anxiety And Other Stories About Where Your Food Comes From, the author explores the role of fruit and vegetables in shaping our environment. She tells BooksfromScotland why our diets are key to saving the planet.

Avocado Anxiety And Other Stories About Where Your Food Comes From

By Louise Gray

Published by Bloomsbury

Why we are all suffering from Avocado Anxiety

When we come back to look at the early decades of the 21st Century, the dish that will surely sum up our age is avocado on toast? The fruit (it is in fact a berry) is one of the most popular photos posted on Instagram, you can buy burgers made almost entirely of avocado, the pop star Miley Cyrus had one tattooed on her bicep. It is hugely popular, but then again it is the subject of derision. Avocados are connected to drug cartels in Mexico and water scarcity in Chile. In one meme it was claimed eating avocado on toast rather than saving money for a house, was preventing young people getting on the property ladder.

Is it any wonder that many of us claim to be suffering from ‘avocado anxiety’. We love to eat this most instagrammable of fruit, but they make us feel confused and anxious.

As an author I want to help people negotiate this ethical minefield. Firstly, what is the carbon footprint of avocados? According to the University of Lancaster it is about 1.6kg of carbon dioxide equivalent per kg. This is a lot less than Scottish beef (18kg CO2e per kg) but a lot more than a Scottish potato (0.3kg CO2e per kg). Generally, fruit and vegetables have a lower carbon footprint because it takes a lot less energy to grow a plant than to raise an animal. However, if the vegetables have been flown in by air freight, such as asparagus from Peru (18kg CO2e per kg), it can be up there with steak. A vegan diet generally has a lower carbon footprint, unless you are living off exotic fruits and vegetables flown in from abroad.

But it is not all about carbon. There are other issues to worry about, such as water. Avocados may not have a heavy carbon footprint but they use up a lot of water, around 85 litres to grow an avocado from Peru. When the water is coming from places suffering water shortages such as parts of Spain and South America this can cause droughts, harming local populations and wildlife. The UK government is so worried about the problem, it has ordered Cranfield University to come up with ideas on how to re-balance our exports and imports so we rely less on imported fruit and veg (we currently import 44% of our vegetables and 84% of our fruit), and begin to build back our own horticultural industry. We will also have to learn to put different home-grown ingredients on toast. (In my book there is a recipe for smashed broad beans on toast).

Then there are the issues of human rights. Avocados have been connected to abuse of workers in Kenya and kidnapping of farmers in Mexico. Bananas perhaps have the most shocking history when it comes to human rights. The UK’s most popular fruit is so cheap because it relies on a monoculture built on cheap labour and the clearing of rainforests.

Oh dear, am I making you anxious? I did not mean to. My book actually found as many positive stories about fruit and veg as negative. Fairtrade bananas are just a little bit more expensive than other bananas (it would cost you just £3 extra per year to switch to Fairtrade). Potato farmers are learning how to look after the soil better, largely from watching the organic movement. Horticulturalists are learning how to make space for nature by growing crops such as lettuce on vertical farms indoors, and leaving wild land for birds and other wildlife. As consumers we can cut food waste by eating our leftovers and embracing the wonky carrot, we can eat plant proteins like broad beans and grow our own courgettes.

One answer is simply not being too anxious. When it comes to food, anxiety does not make people behave better in the long run. It tends to make people freeze and later binge on what they wanted to eat anyway. In the most extreme cases it leads to eating disorders. I think instead we could be educating ourselves about the delicious alternatives and the small ways we can make the food system better. We can shop at our local independent greengrocer or order an organic veg box. As a nation we do not eat enough fruit and veg (only a third of adults eat the recommended five-a-day), we need to start filling our plates with vegetables from farmers and growers we trust.

Ultimately it is about government policy. I believe that by making the consumer aware we can drive those in power to take seriously the role of food in making our population healthier and our environment more resilient. School meals could be procured from Scottish farmers, subsidies could be directed at nature-friendly farming and retailers could be encouraged to stock more affordable seasonal fruit and vegetables.

I can’t completely take away avocado anxiety – I’m not sure I want to, it is a product of living in our age. But through my book I hope I can help you worry a wee bit less.

Avocado Anxiety And Other Stories About Where Your Food Comes From by Louise Gray is published by Bloomsbury, priced £17.99.

When 12-year-old John Nicol gets a job at the Forth Bridge construction site, he knows it’s dangerous. But John has no choice—with his father gone, he must provide an income for his family—even if he is terrified of heights. John meanwhile finds comfort in the new Carnegie library, his friend Cora and his squirrel companion, Rusty. Read an excerpt the morning of John’s twelfth birthday and his first encounter with the life-changing power of books.

Rivet Boy

By Barbara Henderson

Published by Cranachan Publishing

13th September 1888

I wake in a pool of sweat. Seagulls screech, clouds roll and lightning flashes in my dream-darkness. I bite my lip so hard that I taste blood and open my eyes.

A wedge of moonlight shines onto the floor through the gap in the curtain, and the sky is already lightening a little. Dey snores in his little bedroom off the hall, the only bedroom in our flat. Mother shuffles on her mattress in the kitchen alcove and I pull my blanket tight around my shoulders where I lie on the floor. What little light and warmth the range offered has disappeared, and now our flat is shrouded in a ghostly gloom. The second I close my eyes again, I am falling, falling, falling…

‘John!’ Mother’s whisper is directed right into my ear, and I wince away with the fright. ‘What in heaven’s name is wrong with you? Can we get a wink of sleep around here if you please? You of all people will need it, with starting as a brigger on Monday.’

I can’t describe what I am seeing in my mind’s eye, so I don’t try.

‘Sorry, Mother.’

‘If you cry out like that again, the wee one will wake, I’m sure of it, and then none of us are going to get any sleep at all—wheesht now!’ she whispers.

Her wagging finger is right in front of my nose. I answer by rolling my eyes. She clips me round the head—I didn’t think it was that obvious! Gosh, I need to keep my temper in better check.

Turning towards the range and facing the kitchen wall, the sounds of the night envelop me again. Footsteps from the tavern, the hoot of an owl, the faraway rush of the Firth. The rustling.

My eyes ping open. I fear the rats almost as much as I fear heights, but there is no need to worry—it’s only a mouse, still a little fluffy. It has emerged from the crack beside the cooker, looking bewildered and disorientated just like me. Scrambling and snuffling, it makes its way along the edge of the wall. Can it tell that I am watching? Lying on the floor, we are the same: too young and too fluffy for the big world around us. On impulse, I sit up and the mouse shoots back into the crack from whence it came. Mother is breathing deeply again. Moving slowly, I raise myself up and tiptoe to the larder. The door doesn’t creak much if you lift it a little, and I reach in for a crust of bread. Just a little will do the job. I crouch in front of the crack and place the crumbs on the floor in the shadow of the range. This way it looks like we missed this corner in the sweeping.

Crawling back under the cover, I stretch out and stare at the ceiling, but sleep will not come. Thoughts do though, and worries. Today is my birthday. No one should be sad on their birthday. Besides, I am now the proud owner of a book with empty pages.

I doze until Mother begins to stir in the kitchen.

Thursday, the 13th of September 1888. I am twelve.

I can’t help feeling excited. After all, I am going to the new Carnegie Library as a birthday treat. With Dey’s bad leg and Mother so busy with the wee one, I am usually needed for chores and errands, but today is different. By late morning, Mother says the words I have been waiting for.

‘Right! Now don’t say Mrs Nicol does not keep a birthday promise to her only son. You’re a man now, John, and you’ll be a working man all too soon. I wish it was different, but that can’t be helped. Today is your day. You may go to the library; I know you want to. Take out your membership as a birthday treat. Now, I’ve been in to see the librarian and he assures me there will be no problem. Remember to look after anything you borrow though—we’ve no money to pay for replacements, mind.’

‘I will, Mother.’

I walk up along Priory Lane and St Margaret Street before turning the corner to reach the Abbot Street entrance to the library. I have often walked past and wondered what a proper library may look like inside. The well-to-do gentlemen who step so confidently up the stone stairs to its imposing door belong to another world. How could I join them? I feel awe, but also peace as I narrow my eyes against the sun, high in the noon sky, and read the words. Carnegie Public Library. The letters are chiselled into the pointed arch above the door, rounded, swirling and simply perfect. The carved stone sun beneath the arch seems to be turning a blind eye to me, the boy sneaking into a man’s world. Taking the three steps in one giant leap, I am through the door and into the muted light inside. For a moment, it takes my breath away.

How silent it is in here, like a church. I am reminded of the deafening noise of the bridge site. Here one can breathe and think. Dust motes dance in the sunlight from each window. The tiles ooze a comfortable cool, and in the distance, posh shoes tap up and down the polished staircase with its wrought-iron banister. I tiptoe into the lending room and suddenly, stories soar all around me.

Rivet Boy by Barbara Henderson is published by Cranachan Publishing, priced £7.99.

In the much-anticipated second novel from Ayòbámi Adébáyò, we follow the lives of Ẹniọlá and Wuraola, two people from different backgrounds whose lives come together as they are impacted by the political changes in Nigeria at the turn of the millenium. We introduce you to Ẹniọlá in this extract.

A Spell of Good Things

By Ayòbámi Adébáyò

Published by Canongate Books

It did not make a difference if Ẹniọlá reminded her that their classrooms were not even in the same building. His mother would still make him wait for Bùsọ́lá before leaving home. She wanted them to walk to and from Glorious Destiny Comprehensive Secondary School together every single day when possible and had even forced Ẹniọlá to promise that he would always follow his younger sister to her desk before going to his classroom.

On most mornings, as they approached the first school building, their white socks already coated with red dust from what was not even a ten-minute walk, Ẹniọlá often thought about the secondary school his father had promised Ẹniọlá would attend. He was sure there was no red dust on the way to that school. It probably had pavements, walkways and grassy lanes leading from its hostels to its laboratories and classrooms.

Ẹniọlá was nine when his father made that promise. He could not imagine then that anything would cause him to end up in this stupid Glorious Destiny school. He had been in primary five at the time, and all his classmates were preparing to write common entrance examinations. Meanwhile, his father insisted that, since the primary school system was designed to go all the way up to primary six, Ẹniọlá must move on to that class instead of secondary school like most of his classmates.

Ẹniọlá had spent weeks thinking about how he could convince his parents that he was ready for secondary school. He was taller than most of the JSS1 students he ran into on his way to and from his primary school, and he always scored higher than at least half of his classmates in tests and exams. He had memorised all the conversions and tables on the back of his Olympic Exercise Book and could recite the times table from one times one, which equalled one, through twelve times twelve, which equalled one hundred and forty-four, all the way to fourteen times fourteen, which was one hundred and ninety-six. During the weeks that led up to his ninth birthday, Ẹniọlá swept the living room before his mother got to it in the mornings, stopped complaining about not being allowed to go outside and play football with their neighbour’s children when he was asked to watch Bùsọ́ lá, and since he wasn’t tall enough to wash the whole car, spent his Saturday mornings scrubbing the tires of his father’s blue Volkswagen Beetle. Worried that all his goodness would go unnoticed by his parents, even as he suspected that he might be close to qualifying for sainthood, one Sunday on the way to Mass, Ẹniọlá announced that he wanted to become an altar boy. He was relieved when his mother said she would not allow it because it might distract him from his studies. Throughout that week, he lied often about how much he wanted to be an altar boy, making a good impression on his father, who thought such intense desire showed he was growing up in the fear of the Lord.

…

After his father’s promise, it was easier for him to listen as his classmates bragged about secondary school. He could also tell them about how he would attend a Federal Unity school. A year after they all went off to secondary school, yes. But was any of them even going to a boarding school? A Unity school? Ẹniọlá found a way to bring up the Unity school almost every day, retelling the stories Collins had shared with him until he could see that some of his friends had become jealous. Their envy was a comfort as they wrote their common entrance exams and went away to different schools, while he was left behind to complete primary six with two boys who had failed every common entrance exam they wrote. He was going to be like Collins soon. He too would return home thrice a year, and other boys in the neighbourhood would gather around him as he told stories of all he had been up to without his parents monitoring him. He thought about this every day as he walked to and from school alone. The friends he used to make the trip with were no longer his schoolmates, and though he missed them, it did not matter. He was going to be like Collins soon. That would make up for everything; all he had to do was wait.

And then, at the end of his first term in primary six, just a couple of weeks before Christmas, his father and over four thousand teachers in the state were sacked. At first, everything at home went on as usual. His father continued to leave the house at seven in the morning on weekdays, tie knotted, hair shining where globs of Morgan’s Pomade had not been combed in thoroughly, side parting still in place. Ẹniọlá went on believing he would still proceed to the Unity school in Ìkìrun as planned. After all, it was only a matter of time before the governor realised that he was destroying public schools and all the teachers would be reinstated with a personal apology from him. At the very least, some teachers had to be reinstated, and Ẹniọlá’s father, with his experience and qualifications, would definitely be one of those who would be called back because they were needed. It had to happen soon. How would the school run its syllabus without history? How? Night after night, Ẹniọlá fell asleep next to Bùsọ́lá on the sofa while their parents continued this conversation instead of saying the bedtime prayers.

On the radio, one of the governor’s aides explained that most of the teachers who had been retrenched taught subjects—fine arts, Yorùbá, food and nutrition, Islamic and Christian religious studies—that would do nothing for the nation’s development.

What will our children do with Yorùbá in this modern age? What? You see, what we need now is technology, science and technology. And how will watercolours be useful to them? Isn’t that what the fine arts teachers teach them about? Watercolour.

The man on the radio laughed.

Christmas had come and gone. It was the first day of the new year, and some of his parents’ friends, many of whom had also lost their jobs, had come over for dinner. As the man continued to laugh, Ẹniọlá found that although the bowl in front of him was filled with pepper soup, he could no longer feel the sting from the peppers or taste the meat. He felt as though he was drinking water with a spoon. When he returned to school after the holidays, he listed retrenchment and reinstatement among the new words he had learnt during the Christmas break.

A Spell of Good Things by Ayòbámi Adébáyò is published by Canongate Books, priced £18.99.

Darkly comic but full of heart, Justin Davies (Help! I Smell a Monster and Whoa! I Spy a Werewolf – Orchard Books – ) and Floris Books bring us this quirky middle-grade mystery, and it is perfect for fans of Malamander and A Series of Unfortunate Events. Below, the author introduces us to the world of Haarville.

Haarville

By Justin Davies

Published by Floris Books