Victoria Mackenzie’s astonishing debut novel, For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy On My Little Pain, has already been garnering praise from writers and reviewers, and it is a novel that heralds an exciting new voice here in Scotland. Here, at BooksfromScotland, Victoria tells us about some of her favourite books.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy On My Little Pain

By Victoria Mackenzie

Published by Bloomsbury

The book as . . . memory. What is your first memory of books and reading?

At primary school I loved a book called Flossie Teacake’s Fur Coat by Hunter Davies. When Flossie puts on her sister’s coat she is magically transformed from gawky child into a glamorous 18 year old. The book spoke to my frustrations of being a child, with no autonomy, no choice about anything, and yearning for a grown up life which I thought would be full of excitement and adventure. Ha!

The book as . . . your work. Tell us about your debut novel For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy On My Little Pain. What did you want to explore in writing this book?

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy On My Little Pain is based on the lives of two medieval mystics, Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, who lived in Norfolk in the early fifteenth century. They both claimed to have visions of Christ, at a time when such claims risked accusations of heresy – and when the punishment for heresy was to be burnt at the stake.

I wanted to show the very different ways that these two women coped with their visions, and also to explore what life was like for a woman in the medieval period. Julian’s experience of being an anchoress particularly intrigued me – I wanted to imagine how it would really feel to be in a single room for so many years. What was it like physically? The cold, the boredom, the inability to stretch your legs and get fresh air. And how would it change your personality, your ideas about the world, your sense of self?

The book also explores motherhood, the impact of grief, and the very human need to be loved and accepted by others.

The book as . . . inspiration. What is your favourite book that has informed how you see yourself?

Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts. She writes so honestly and frankly about the body, sex, parenthood, love, relationships, but her writing is also informed by her deep engagement with literary ideas. The way she brought together the bodily and the intellectual was a revelation.

The book as . . . an object. What is your favourite beautiful book?

The graphic novel The Dancing Plague by Gareth Brookes. It’s a sort of graphic novel, though it tells the true story of a dancing plague that afflicted a town in Strasbourg in 1518, when many inhabitants were seized by a demonic compulsion to dance. Brookes uses a blend of his own ‘pyrographic’ techniques and embroidery to create incredibly unusual and beautiful images. And it’s all offset with a wonderful medieval sense of humour – earthy insults and exclamations, like ‘By the balls of St Bartholomew!’

The book as . . . a relationship. What is your favourite book that bonded you to someone else?

A lot of my friendships are based on a love of books and I met two of my closest friends when we worked together in the same library. Recommending and sharing books has become part of our twenty-year conversation so it’s hard to narrow it down to a single book. Recently I recommended Leonard and Hungry Paul by Rónán Hession and that was a big success, it’s such a gentle, lovely book.

The book as . . . rebellion. What is your favourite book that felt like it revealed a secret truth to you?

There’s no single truth that a book has revealed to me about myself, but there are many books that have resonated in their approach to life and art. During lockdown I read Samantha Clark’s memoir, The Clearing, which contained many truths about family relations, art as a discipline, and the pain that can be caused when you need to carve your own path in life. It’s such a thoughtful meditation, full of clear-eyed observations – and her writing style is exquisite.

The book as . . . a destination. What is your favourite book set in a place unknown to you?

I’ve never been to Paris and would love to be a fly on the wall (or perhaps that should be a barfly) at the 1950s Paris bars and cafes in James Baldwin’s novel, Giovanni’s Room, hanging out with the artists and misfits. I’m a big fan of short books that pack a punch, and this one is just stunning.

The book as . . . the future. What are you looking forward to reading next?

I’ve recently been given The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave, which I’m really looking forward to. Like For Thy Great Pain it’s an historical novel based on a true story and explores the way society tries to constrain women and punish them for independence. Hargrave’s novel is set in Norway in 1617 and I’ve a feeling the writing will be absolutely gorgeous.

For Thy Great Pain Have Mercy On My Little Pain by Victoria Mackenzie is published by Bloomsbury, priced £14.99.

For most of us the word ‘palaeontology’ is likely to conjure images of dinosaurs and flying reptiles, but what of that other evolutionary branch to which we belong, the mammals? In Beasts Before Us, palaeontologist Dr Elsa Panciroli expands our understanding of evolutionary history to reposition mammals as central protagonists throughout the pre-historic era. We spoke to Elsa about her remarkable work and the impact she hopes it might have.

Beasts Before Us: The Untold Story of Mammal Origins and Evolution

By Elsa Panciroli

Published by Bloomsbury

Can you tell us a little bit about Beasts Before Us?

Mammals are animals that feed their young on milk, and have fur. They include most of the large charismatic creatures on Earth today, including humans. Most books about the origin of mammals start when the non-bird dinosaurs became extinct after an asteroid impact about 66 million years ago, but this is far from the true beginning. Beasts Before Us tells you the part of the mammal story you’ve never heard before, it is the untold story. It stretches back over 300 million years to our first egg-laying predecessors, which share a common ancestor with reptiles. The book then takes you through time following the incredible evolution of our lineage, which flourished long before the dinosaurs appeared.

In Beasts I also seek to reframe a few narratives: for example we need to challenge what evolutionary ‘success’ looks like – tiny rodents are arguably the most successful mammals on earth! I don’t shy away from addressing the dubious practices associated with fossil extraction, which has traditionally been tied to the exploitation of indigenous people and lands. I also tell the stories of some less well-known scientists, such as the indefatigable Polish researcher Zofia Keilan-Jaworowska, who defied the Nazis to learn palaeontology, and led expeditions to the heart of Mongolia in search of fossils.

The book is not what one might expect when they imagine a book on paleontology – it is witty, engaging like a page-turner, and anchored by a clear storytelling style that seamlessly drifts into reflections on your own past. What made you write this book in this way?

Very few people enjoy reading dusty, dry scientific text, not even scientists! When I write I always think: if I wasn’t a scientist, would I want to read this? By challenging myself in this way constantly, I remember to keep the reader at the heart of what I write. I hope to connect with readers by sharing non-scientific details too: the soggy atmosphere at a field site, or the thrill a fossil gives you when you touch it. Extinct animals and places can be hard to picture in the minds’ eye, so adding elements of creative storytelling helps you imagine them and engage with the science.

What connections do you see between storytelling and our understanding of evolutionary history? How has storytelling shaped popular understanding of our origins over the past centuries?

Palaeontology is a lucky science, because fossils lend themselves so naturally to storytelling. The very best science communicators have always used narrative methods to talk about discoveries. A good example is Hugh Miller (1802–1856), a Scottish writer and self-taught geologist. His books were like the David Attenborough documentaries of his day. He was widely read around the world, and much admired by great thinkers and writers, including John Ruskin and Charles Dickens. Miller’s books were enjoyed not just for the knowledge they contained, but his amazing way with words; he presented evolution like a theatre, with stage sets and actors entering and exiting the scene, something his readers would have connected with easily. Another example is the brilliant Arabella Buckley (1840–1929): she wrote popular science books for people of all ages that championed evolution, and did so in a way that avoided a lot of the masculine-dominated narratives of the time. Great figures in science at the time credited her with setting them on their scientific career path.

Storytelling is a powerful thing, it can shape the way we think about the present as well as the past. And of course, the way we interpret the scientific evidence and tell those stories reflects current society almost as much as it does the state of knowledge itself.

You wrote Beasts Before Us relatively early into your research career. Has it always been an ambition of yours to write a book?

Certainly, I’ve been writing since I was six years old! All through childhood I would scribble excessively long stories and draw illustrations to accompany them. I composed silly poems too, inspired particularly by Roald Dahl. Over the years I’ve kept writing, most of it fiction, including writing almost a complete book – a story steeped in nature and Scottish folklore. But unfortunately I never had the confidence to try and publish anything more than a handful of poems. It wasn’t until I began my academic training in my late twenties that I gained the skills and confidence to send work to editors and publishers. Although my articles and books are non-fiction, I try and allow some of my creative side to creep in wherever I can.

While most people associate paleontology with the study of dinosaurs, you use this book to champion the evolutionary history of mammals as just as, if not more, worthy of study. What can we gain as human beings by studying our animal ancestors?

Evolutionary history gives us a kind of perspective that’s hard to gain any other way. Robert MacFarlane called it gaining ‘deep time spectacles’; the ability to see beyond the miniscule scope of the human lifetime. I find that very humbling. I think looking at the path of evolution can also challenge our interpretation of ourselves and the natural world. We see that the traits we associate with being humans – like large brains, replacing our baby teeth with adult ones, feeding our babies on milk – can all be traced to our ancestors, countless millions of years ago. The more you look, the more clear it is that every organism is connected through common ancestry, which gives us a sense of kinship with all life on earth. We can also see how intimately organisms are linked to the world around them, responding to changes in habitat and climate. It’s really quite beautiful. This interconnectedness is something I explored in my second book, Earth: A Biography of Life.

The book ends with a relatively grim forecast of our future, with the Anthropocene incurring a current mass extinction event that is set to see all but the smallest and most adaptable mammals going extinct. What changes can we as individuals make to help stave off the destructive impact of human activity on the world’s biodiversity?

I understand people might find it a bit grim, but there are seeds of hope in there too. Looking over hundreds of millions of years, life has withstood some pretty brutal extinction events – times when our seas were hotter than a bubble bath, and the rain was acidic enough to melt snail shells. I find comfort in knowing that, eventually, life recovers. But it only does so because the major perturbations that cause extinctions (whether they are from asteroid strikes or gases from volcanic eruptions) have always been temporary. This teaches us a really simple lesson: if we can stop poisoning our atmosphere and destroying habitats, life will spring back. But the longer we leave it, the more we will lose – extinction is forever, after all. So this isn’t an excuse for complacency.

There are many ways we can curb our impact on the planet as individuals, and we should do as many of them as possible. From small things like avoiding plastics, to the single biggest thing you can do, which is eat vegetarian and vegan. Meanwhile, we need to campaign to reshape our society away from the destructive consumerist patterns we’ve got ourselves stuck in. There is definitely scope for us to live happier lives with a much lighter footprint on the planet. If we lay off nature and give it a chance, it can spring back. The sooner we do this the better.

If you could choose one thing you hope readers take from Beasts Before Us, what would it be?

That’s a difficult question! I’d hope I can persuade people away from some of the old-fashioned ways of thinking about evolution. A lot of empirical language dominates how we discuss nature, there are ‘winners’ and ‘losers’, and we talk about life as if it is a series of oppressive empires that rise and fall. I think it’s time to step away from that militaristic framework and see that everything that ever lived, whether it’s big and small, charismatic or niche, hunter or prey – is successful and well adapted for its time and place. Whether it became extinct or not is really just a matter of luck.

Beasts Before Us: The Untold Story of Mammal Origins and Evolution by Elsa Panciroli is published by Bloomsbury, priced £12.99.

This month sees the 100th birthday of the legendary Ivor Cutler. Bruce Lindsay has just released a biography of this unique artist and performer, and here, for BooksfromScotland, he chooses ten of his favourite Ivor Cutler moments. Enjoy!

Ivor Cutler: A Life Outside a Sitting Room

By Bruce Lindsay

Published by Equinox Publishing

-

‘I’m Going in a Field’ – on Ludo

-

‘Yellow Fly’ – on Velvet Donkey

-

‘Cockadoodledon’t’ – on Ludo

-

‘Pass the Ball, Jim’ – on Privilege

-

‘Life in a Scotch Sitting Room Vol 2 Episode 2’ – Velvet Donkey

-

‘I Ate a Lady’s Bun’ – A Flat Man

-

‘Barabadabada’ – Jammy Smears

-

‘Phonic Poem’ – Velvet Donkey

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qfnfhseuncM

-

‘Whale Badge’ – Privilege

-

‘I Believe in Bugs’ – Dandruff

And for a little bit of a cheat, Bruce also recommends watching:

Shoplifters

Ivor Cutler by Ivor Cutler

Ivor Cutler: A Life Outside a Sitting Room by Bruce Lindsay is published by Equinox Publishing, priced £25.

A man has broken into Zoe’s flat, someone she thought she’d never see again. A man they call the Hand of God. Now that he’s found her, she knows she must return to a past she thought she’d left far behind, to the cult of the Children and their isolated compound Home – to rescue the sister who saved her all those years before. Read an exclusive extract from this heart-racing thriller about coming of age under the indoctrination of a cult – and the extraordinary lengths it takes to break free.

Home

By Cailean Steed

Published by Raven Books

I’ve been thinking about the red entries that the Hand of God had me read from the book. They both had the same letters – F and S, for Father and Seed – but different numbers.

Different women. But Father only has one wife.

I consider asking about this, but it doesn’t seem right. I look out of the window instead.

We’ve only been in the car a couple of hours so far. Our usual trips last hours and hours, take us far away, but this doesn’t feel like a usual trip.

We start to pass more and more houses, until there’s no fields or trees to be seen at all and we’re in the middle of innumerable tall grey buildings. It’s raining, and Sullied people scurry past on the streets with their faces hidden under hoods or umbrellas. Some buildings are all windows in the front, and have bright signs on top. These are ‘shops’, the Hand of God has told me. Sullied people use their money to get things in them, mostly things that they don’t need. It’s called ‘shopping’. When there’s so many buildings around you that you feel swallowed up in them, that’s called a ‘city’.

The Hand of God pulls to a stop at a red light. Sullied people can’t be trusted to know when to stop and go while driving, so they need lights to tell them. The Hand of God scratches his cheek and his nails make a rasping sound against the stubble there.

‘You will likely find the place we visit tonight strange, little Acolyte,’ he says. ‘It’s not something I’ve shown you before.’

‘Not the woods?’ I say. He smiles a little.

‘Not the woods, no. It’s… well, you could think of it as a kind of outpost.’

‘An outpost,’ I repeat. I haven’t heard the term before.

‘In a manner of speaking. You know that we draw new Children from among the Sullied, when they are worthy enough.’ The light turns to green and the car begins to move forward again.

‘They give us money,’ I remember.

‘That’s right. But some also complete spiritual tasks for us, depending on their abilities and station. Tasks that are … useful for us. For the Children. Some Sullied people have positions that make them important in their society, for various reasons. We draw those people to us. And some very lucky Sullied people, if they are enough use to us, become truly Unsullied, and join the rest of the Children at Home.’

‘Alright,’ I say. I think about the Awakened people I know at Home, which makes me think about Teneil, which makes me think about her arm flopping as the man carried her out of the hall, which makes me think about what I heard last night. I still haven’t told the Hand of God any of it. But he knows what I know. Of course.

Doesn’t he?

‘So there are places in the world Outside, places where those Sullied who are working to become Unsullied gather and do good work. Outposts of the Children. We call those places “churches”.’

‘Churches,’ I say, tasting the strange word. ‘So today we are visiting churches?’

‘A church. And yes, we are. First. Then our work will take us elsewhere.’

‘Are we getting rid of a demon tonight?’ I say, feeling a little thrill deep in the pit of my belly. It’s a bit like excitement, but it’s also a bit like feeling ill.

‘Oh, yes. We will rid the world of a great evil tonight,’ says the Hand of God. ‘An evil that comes from the heart of the Children itself. And your actions tonight will prepare you for the greatest task of all, little Acolyte.

‘I won’t let you down,’ I say.

The Hand of God touches my shoulder. ‘I know you won’t,’ he says.

*

I stare down at my fingers, twisting together in my lap. I should feel happy. Proud. He’s trusting me with more of our important work. But I don’t feel right. I can’t stop thinking about how I haven’t told him everything, and how that shouldn’t matter – how he should know it, anyway. The Elders and the Hand of God can read minds. It’s what we were always taught. They can tell when you’re lying. The Hand of God knew I was lying that time in the Atonement Room, when I told him that Amy hadn’t said anything important to me before she left. Of course he did. Because he knows everything I know.

The only possibility is that he knows I was listening that night – the fact that he came into my room and tucked me into bed suggests he knew I’d been up, anyway – and doesn’t feel the need to talk about it. And it must be the same with what I saw in the Worship Hall last night. He’d bring it up if he wanted to know more.

That’s it. That’s got to be it.

Why, says a little voice in my head that sounds a lot like Catherine, would he ever need you to open your mouth, if it was really true he could read minds? Why would he ever ask you to speak? He wouldn’t. He wouldn’t need you to ever talk, or answer his questions.

I think shut up as hard as I can, but the voice keeps going, relentless.

He’d know you were thinking this, it says. He’d know that you were doubting him, right now.

I look over at the Hand of God, panicked. But he’s just looking ahead and navigating the car through more grey city streets. He doesn’t look like he’s noticed anything at all.

It’s not true, the voice says. And if that’s not true …

What else isn’t true?

Home by Cailean Steed is published by Raven Books, priced £14.99.

Heather Darwent’s The Things We Do To Our Friends, is a psychological thriller set in Edinburgh. It tells the story of Clare, a misfit who arrives in the city hoping to reinvent herself. She aspires to make new friends, friends who will help her become the person she believes she can be. Soon she meets an ambitious, monied group of students who have big plans for her, but their plans are potentially dangerous, their intentions shrewd yet unscrupulous. Clare must reckon with how far she’ll go for the group, and what she’ll do to hide her own terrible secrets…

We asked Heather to recommend seven deadly friendship novels that partner perfectly with her debut.

The Things We Do To Our Friends

By Heather Darwent

Published by Viking

The inspiration around the book was friendship in all its glory, the negatives, and the positives. I wanted to write something that placed these connections at the heart of the plot as I’m endlessly fascinated by the platonic relationships we make through our lives, and how these can sour and become toxic.

The challenge was to create friendship on the page: the chemistry, the shared history, and indeed the idea of ‘banter’ that can be hard to express. If the group is too big, it’s hard to form distinct characters, but then a certain amount of characters are needed to create a delicious tension. It’s tricky, and some authors nail these logistical challenges. These are seven of my favourite novels with intriguing, and sometimes deadly, friendship groups. All of these books give such a focus to friendship and make for fascinating reads.

The Truth Will Out by Rosemary Hennigan

In The Truth Will Out, Hennigan uses the backdrop of the theatre, and it leads to a claustrophobic narrative. The group convenes to put on a play, recreating a tragic event from the past, and the complex friendships and tensions set around the rehearsals are cleverly crafted.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

It would be remiss not to mention The Secret History by Donna Tartt. Here, the friendships are flawlessly constructed, an elite group who feel so incredibly real. The way the group falls apart as the book descends into a dark thriller means it’s impossible to look away.

The Secret Place by Tana French

School friendships have a certain allure to them. The characters are not yet fully formed: the insecurities heightened; alliances uncertain. This is a crime novel that also serves as a brilliant character study.

The Lessons by Naomi Alderman

I loved this atmospheric book that begins in an Oxford College. The friendships here are charged with rippling tension, and the story follows the characters into their adult life as the friendships morph into co-dependency.

Social Creature by Tara Isabella Burton

The ruthless narrator, Louise, makes for a compelling voice in Burton’s debut. I found the Ripleyesque plot to be truly gripping, and it’s beautifully written with plenty of twists and turns.

We Were Liars by E. Lockhart

A YA novel that explores the charms and pitfalls of a gilded upbringing. Here, the relationships between the teenagers are expertly pitched against the adult ties. There’s bucket loads of toxic behaviour, plus a gasp-inducing twist ending.

The Girls Are All So Nice Here by Laurie Elizabeth Flynn

The girls in my final pick are truly horrible. Each time you think they couldn’t get more malevolent; they surprise you in this twisty thriller. The dual timeframe works really well, and a college reunion is an enticing setting for a final showdown.

The Things We Do To Our Friends by Heather Darwent is published by Viking, priced £14.99.

In Abi Elphistone’s re-imagining of the classic Peter Pan story, Martha Pennydrop is ten, and desperate to grow up. Eagerly awaiting the Moment Life Begins, she busies herself with taking care of her little brother Scruff. But when Martha and Scruff discover a drawer full of mysterious gold dust in the bedroom of their new house so begins an incredible adventure to the magical world of Neverland which forces her to rediscover the imagination she thought she had to turn her back on to keep her brother safe. Meet the Pennydrop family in this exclusive extract below.

Saving Neverland

By Abi Elphinstone

Published by Puffin

Number 14 Darlington Road in Bloomsbury, London, looks like a perfectly ordinary townhouse – at first glance, anyway.

It is tall and thin, with three rows of windows and a blue door with a brass knocker. Almost an exact copy of the terraced houses either side of it. And yet, if you were to linger a while outside Number 14, you would notice that one of the top-floor windows – the one with the white cotton curtains billowing in the breeze – is never shut. Even on the coldest winter nights, when frost clings to the rooftops and the air swirls with snow, you will find this particular window wide open.

Had ten-year-old Martha Pennydrop known there was something strange about this window when her family moved into the house a few weeks ago, I very much doubt she would have chosen the room beyond it as her bedroom. But it had been at the start of the summer holidays, when nights are warm and bedroom windows are often left open, so she wasn’t aware that this one was impossible to shut, and that it had been that way for over a hundred years.

And she certainly wasn’t aware that magic was involved because, until the mischief kicks in, magic looks remarkably innocent.

✩

Martha was sitting on her bed the evening it all began. Sunlight spilled in through the open window, and, if Martha had not been concentrating so hard on the notepad in her lap, she might have noticed that her whole bedroom was lit gold in the setting sun. But Martha didn’t have time for noticing things anymore. She was ten now, and ten – as everyone knows – is the beginning of the end. It’s when your age jumps to double digits.

It’s when you enter your last year of primary school. It’s when you’re expected to eat all the vegetables on your plate without complaining.

Ten was, as far as Martha could tell, the age at which you either grew up or got left behind. And getting left behind wasn’t an option because Martha had discovered it came with dangerous consequences – consequences that were always there, lingering at the back of her mind.

Growing up while sharing a bedroom with your seven-year-old brother, however, was like trying to complete a complicated puzzle in the same room as a rhinoceros.

‘WHOOPEE!’ Scruff shrieked as he bounced on his bed in his pyjamas, knocking over a lamp and sending a photo frame clattering to the floor. He leaped still higher.

‘These beds are so much springier than our old ones, don’t you think?’

Martha didn’t answer, but she looked up briefly because a secret part of her wanted to leap on to her bed and bounce with Scruff. She pressed her notepad into her lap to stop her legs getting any ideas because charging into childish games could, and most probably would, lead to disaster. It certainly had done six months ago . . . Martha shuddered at the memory of the Terrible Day and turned back to her notepad.

‘If the roof wasn’t in the way,’ Scruff said, panting, ‘I could probably bounce out of the house and over half of London.’

Martha tried her best to focus on the list in her notepad. It was a checklist for the day just gone, detailing all the jobs she had done about the house to make sure things didn’t get out of control. She ran her finger down the list of evening duties to make sure she’d ticked each one off:

- Have bath (make sure Scruff washes between his toes and behind his ears)

- Brush teeth (give Scruff a star on his Star Chart if he does it without shouting and kicking – ask Dad if Scruff can sponsor a sloth or a penguin or whatever his favourite animal is when he gets ten stars)

- Lay out clothes for the next day (search Scruff’s pockets for sweets as kitchen supply suspiciously low)

- Brush hair (if feeling strong, wrestle Scruff to ground and brush his too)

- Check Scruff’s inhaler is in our bedroom (VERY IMPORTANT)

Martha flicked over the page and scribbled out the same checklist for tomorrow. Then she turned to the back of her notepad and lifted out a photo. It showed her doing a backflip in their old town hall while the rest of her gymnastics club cheered her on.

She smiled. Her dad had taken her to that club every Saturday: she’d learned to do the splits while performing a handstand and do a backflip from standing. And just as good as all that was her dad being around so much more then, driving her to and from the club, and spending the hours in between with Scruff, who loved animals so much that the keepers at the local animal sanctuary let him muck out the llamas at weekends.

But then Mr Pennydrop had been asked to head up the removal company he worked for. Rather than working nearby, he’d had to take the train to and from the company’s head office in London, a two-hour journey twice a day, every weekday for a year.

With each passing day, Martha noticed him becoming more and more stressed, so she and Scruff had tried to do nice things to help him relax. They’d decorated Mr Pennydrop’s briefcase with unicorn stickers, but on seeing them he hadn’t looked very pleased. They’d baked a cake for his birthday, but misread the recipe and stirred in washing powder instead of baking powder. The cake had tasted of soap. And they’d painted Father’s Day cards at the childminder’s house one evening after school, but in their rush to give them to their dad they hadn’t waited for the paint to dry, and the important documents Mr Pennydrop was holding had been ruined.

Then the last day of the summer term had come, just over a month ago, and Mr Pennydrop announced he’d found a fully furnished flat to rent, on the top two floors of a house in London, and they were moving there because it would make life easier. Only life didn’t seem easier. Martha’s dad was trying his best with her and Scruff, but he was still just as stressed. Perhaps even more so given that he’d started locking himself up in his study after school pick-ups to chase up removal vans and organize paperwork.

Martha thought of her mum briefly, hundreds of miles away from Number 14 Darlington Road in some new place or other. A Free Spirit was what Mr Pennydrop called his ex-wife (so free, it turned out, that she had checked out of the family when Martha and Scruff were very little and checked into a backpackers’ shack on a beach in Thailand and never returned).

She sent postcards now and again, but Martha didn’t bother reading them. It wasn’t as if she missed her mum; she’d barely even known her. And, quite frankly, Martha had enough on her plate keeping the family going and preventing another Terrible Day.

Saving Neverland by Abi Elphinstone is published by Puffin, priced £14.99.

In a powerful mix of memoir, travelogue and history, Allyson Shaw takes the reader around Scotland with the stories behind a handful of women who were convicted and executed as witches. In this extract from Ashes and Stones, we learn more about Lillias Adie, who faced trial in Torryburn in 1704.

Ashes and Stones: A Scottish Journey in Search of Witches and Witness

By Allyson Shaw

Published by Sceptre

Lillias’s accuser was a woman named Jean Bizet. Neighbours could come forward with accusations during a kirk session. In the session minutes, Jean Bizet describes going from house to house in the village one night, drinking. Near the end of the evening, she was seized with terror, convinced that Lillias was coming for her. Other witnesses heard Jean Bizet cry out, ‘O Lilly with her blew doublet! O Mary, Mary Wilson! Christ keep me,’ while wringing her hands and then passing out. According to the minutes, Jean Bizet was at a friend’s house late into the evening and was in a state of drunken distemper. She accused Lillias Adie of acting with Janet Whyte and Mary Wilson in a conspiracy. When Jean Bizet’s husband, James Tanochie, heard of this business, he said he would ‘ding the devil out’ of his wife.

Lillias was perhaps vulnerable as an elderly, single woman. The victims of the Scottish witch-hunts were overwhelmingly poor, older women. Lillias had an unusual appearance that perhaps marked her out from her neighbours. We know from the dimensions of Lillias’s coffin before it was destroyed that she was uncommonly tall. Her teeth were very prominent. Jean Bizet fixates on Lillias’s blue doublet, and from the scant statements at the trial, it’s impossible to know why this troubled Bizet. Was Lillias’s doublet brighter or finer than most? While this detail is seemingly inconsequential, it forms a fragment of Lillias as an individual woman, part of a time, a place and a people, and it helps us picture her. A blue doublet would have been a common garment at the time. The clothing of the poor was often dyed with woad, a yellow-flowered plant with tall stems and pale leaves. Woad blue is the blue of the sky reflected in the sea on a sunny day. That blue was the colour of much modest clothing, and had been for a millennia, and it was the blue Lillias wore.

Following the accusations of Jean Bizet, Lillias Adie was arrested by Bailie Williamson at 10 p.m. on 28 July 1704. Modern readers marvel at the confessions wrung from the accused during the witch-hunts, perhaps imagining women on a witness stand, confessing bizarre, sordid behaviour. This is often the way witch trials are portrayed in fiction. The reality is that, after arrest, the church needed evidence to take to the Privy Council in Edinburgh. The bulk of the evidence was the confession, extracted over months, during which the accused was often tortured, starved and sleep-deprived. There was no limit on how long the Kirk could hold someone before producing this ‘evidence’. The interrogators would ask leading questions: ‘When did you sleep with the devil?’ ‘Where did you meet other witches?’ and, crucially, ‘What are their names?’ These interrogations would have been intense. A room of powerful men questioning a terrified, tortured woman.

During Lillias’s initial interrogation, she swore, ‘What I am to say shall be as true as the sun is in the firmament.’ She confessed to a flurry of demonic meetings. Between interrogations, she was possibly held in the garret of the Townhouse of Culross – the seat of government and also a prison, where women accused as witches were confined and ‘watched’. The loft space where she was held had no fire for warmth, and what little light there was came up through the slats of the floor. A man would have been paid to watch her and keep her awake. Sleep deprivation was the most common form of torture used to extract confessions from the accused. It was effective. Lack of sleep for one or two nights created a docile suggestibility in the prisoner’s mindset. Longer periods of sleep deprivation resulted in hallucinations and deeper confusion.

Between Lillias’s trial record and everything that went unsaid and unrecorded, we must read her sufferings. The interrogators only wrote down what they thought they needed to convict her.

Perhaps she was led, in her exhaustion, to believe what was being asked of her. The crime of witchcraft involved merry-making with the devil, renunciation of Christian baptism, and the sex crime of ‘meeting with the devil carnally’. The ministers pointedly asked accused women if they’d had sex with Satan, and the churchmen wanted details.

Lillias was interrogated by the minister and church elders four times during the course of her month-long incarceration, which ended only because she died, perhaps of suicide or the effects of imprisonment on her aged body. The trial record states that Lillias had been meeting the devil since the previous witch-hunt in Torryburn in 1666. She would have seen these earlier public executions as a young woman. Over the course of their lives, almost everyone in early modern Scotland would have witnessed the spectacle of women strangled and burned at the stake. It was an event, and often ale was given to the spectators. The bonfire would have been seen for miles and the smoke would have lingered for days, a signal to other women. No one was safe; none were immune to accusation. This is how terror works.

Lillias’s interrogation went on; she met with a coven of ‘twenty or thirty’ witches, all now dead. She stated that she could not name the others, as they were ‘masked like gentlewomen’. As with all confessions extracted under torture, one must read beyond what is written. In this detail of others being dead or masked, we glimpse Lillias’s courage. Her interrogators wanted names, and she initially provided none. In her further confessions, she said that the devil had come to her hundreds of times and ‘lay with her carnally’. When he first trysted with her, it was at the hour just before sunset on Lammas, or the first of August, a transitional hour on the cross-quarter day in the harvest calendar. Lammas, or ‘Loaf Mass’, marked the midpoint between the summer solstice and the autumn equinox. At this pivotal moment, at an hour that was not quite night nor day, Lillias said she met the devil behind a stook, or bundled sheaf, set up in the field to dry. He was both pale and black, and his flesh was cold. Lillias added details: the devil wore a hat and arrived at their dances on a pony. Though he promised her much, she said he gave her only poverty and misery.

Ashes and Stones: A Scottish Journey in Search of Witches and Witness by Allyson Shaw is published by Sceptre, priced £18.99.

When Hanni Winter shows her new husband the heartbreaking photos she captured during the war, he recognises one of the girls as his sister he thought was lost in the concentration camps. They decide to find her, and travel back to where Hanni took the picture. But there is more to Hanni’s past that her husband doesn’t know. In this extract, Hanni worries about the consequences of their journey.

The Girl in the Photo

By Catherine Hokin

Published by Bookoutre

Once the euphoria of recognising Renny in the photograph had worn off and all the arrangements for the journey were in place – once there was nothing else to do but set out on it – Freddy’s faith in the search had started to crack. He was too proud to admit that he was wavering; Hanni was too careful of his emotional state to comment. The visit to Elias, and more specifically the way Freddy had looked at her in the bar and the night that had followed, had made her remember the basis of their bond.

His happiness matters more to me than mine; mine matters more to him than his.

So when Freddy’s hopes started to fly, she didn’t pull them down again: she encouraged them to soar. And when they crashed, she didn’t beg him to listen to the voice of reason in his head, or in hers, and stop. It was a change he was grateful for, a shift in mood that pulled them back together. It didn’t mean Hanni was blind. She saw the doubts clouding his eyes when he thought she wasn’t looking. And she had seen the tremor in his hand when they were finally travelling through the German Democratic Republic and the GDR train guard spent too long scrutinising their papers.

‘It’s unusual to see a police inspector from the West venturing into the East. This conference in Dresden must be an important one.’

Freddy had agreed, very seriously, that it was. Then he had launched into a speech about shared investigative processes still being a focus despite Germany’s political divisions, which was horribly flimsy but bored the train guard away.

The instant the man was gone, Freddy’s façade collapsed. He crumpled back into his seat and immediately started to fret over Hanni’s safety.

‘That was rough. That was harder than I expected and those are our legitimate papers. If the Czech ones are subjected to the same level of interest…’ Freddy left ‘which they will be’ unsaid, but it still hung there between them. ‘Well, you heard what Elias warned us could happen. I won’t blame you if you want to call it quits, Hanni. And I won’t hold it against you, no matter how hard I came down on you before.’

It wasn’t exactly an apology, and Hanni wasn’t looking for one of those – she understood why he had felt let down – but it was good enough, it came from the heart. They had always had a language of their own. They had learned to say ‘I love you’ and ‘I need you’ in a myriad different ways while they navigated who they were going to be to each other. They might forget how to use it at times, but, so far, that language had always come back.

Hanni slipped her hand into his, grateful beyond anything for that. ‘And since when did I give up on things, or sit waiting at home like a good little wife? It’s not your responsibility to find her, my love – it’s ours.’

Ours sounded good; it sounded as certain as us. Hanni wanted to believe it; she wanted Freddy to believe it. She had filled her voice with all the confidence Freddy had been trying to pour into her for the last three weeks. They had learned how to wrap that – or the imitation of that – around each other as well.

He smiled and pulled her closer. Hanni nestled into his side and took refuge in a silence she hoped Freddy would decide was a companionable one. The last thing her nerves needed was questions. Unfortunately, his senses were still on alert.

‘I really needed to hear you say that. You’ve been so on edge since we left Berlin, I thought you were regretting coming with me.’

Hanni shifted away from him before her stiffening body betrayed her. She thought he had been too busy to notice her fears, or that she had been successfully hiding them.

Tell him who you saw on the platform at Berlin. Tell him why that scared you. Don’t hide the truth again, or lie like you did with the Theresienstadt photographs.

It was the right impulse, but Hanni couldn’t act on it. The truth – ‘there was a man I recognised at the station. He was at my exhibition, behaving oddly, and I think he might be following us’ – opened up a minefield. They were about to illegally enter a country where – or so rumour had it – Soviet-backed secret agents were as completely embedded as they were in the GDR. Hanni didn’t need Freddy to have even the slightest suspicion that there were eyes already on them. That would only convince him that he was right to be cautious, that he should go on without her.

Which might be the best thing; it would at least get me out of this.

As much as Hanni wanted to support Freddy, she also desperately wanted to turn round and go home. She wanted Theresienstadt to disappear back into history and for Freddy to give up. Except he would never do that, so she couldn’t either. Never mind that he might discover secrets in the town which she wouldn’t be there to explain, his quest could very easily end in heartache. How could she abandon him to face that pain alone? So she couldn’t turn back and she couldn’t tell him that they might be being followed, either by a secret agent or by her father. Admitting the possibility of that was unthinkable. It would involve spilling the whole story of Reiner and his web of spies, and it wasn’t the time for that yet. Besides, she could be wrong. Hanni wasn’t certain that the man she had seen boarding the Dresden train at Berlin’s Ostbahnhof was the one who had thrown her off balance at the gallery. His height was similar, and so was the dark hair combed neatly under his hat. But it had been a moment’s glimpse in a crowded station. He hadn’t turned; she hadn’t seen his face.

And why would Reiner set a tail on me when I am so clearly not following him?

Freddy had noticed her nerves but that was all he had noticed, and telling him the truth was too dangerous. So, despite what she had promised herself, it had to be another lie. But a small one; a deflection.

‘Of course I’m not regretting it. And yes, I’ve been a little on edge but it’s nothing to worry about.’

Hanni kissed Freddy’s cheek and smiled into his eyes, hating how easy it was for her to convince him she was never anything but honest.

‘I’m nervous about my language skills, that’s all. If I’ve been quiet it’s because I’ve been running all the phrases and grammar I learned years ago back through my head and testing my fluency. I’m not sure it’s as good as it could be.’

That too was a minefield. Hanni had told Freddy that she had learned Czech but she hadn’t told him why, and he had been too caught up with Elias’s complicated chain of arrangements to ask her. Now that his detective’s brain was re-engaged and he was weighing up the journey’s dangers, she could see the questions forming. She kissed him again, on the mouth this time, offering a silent thanks for the luxury of an empty carriage.

‘So maybe we should take the time now to practise. Run over our cover stories in Czech rather than German and quiz each other about them.’

It was a good suggestion, it did what was required and diverted him. They spent the rest of the journey turning their identity papers into fully fledged characters and helping each other iron out their accents. By the time the train pulled into the tiny suburban station on the edges of the city, which was as close as the rail line still went, Freddy’s nerves had vanished and his enthusiasm was racing.

He helped her down the steep step and onto the platform, holding on to her hand as they weaved their way through the press of people and bags. Hanni knew how they appeared to the world, there were enough admiring glances to tell her: like a couple perfectly in step and in tune with each other. It was what she wanted them to be, and she knew Freddy would have agreed with that assessment if anybody had asked him.

What would he do if he knew the truth? If he knew what a good actress I’ve become? How devastated would he be then?

The thought of that was as bad as the lying.

The Girl in the Photo by Catherine Hokin is published by Bookoutre, priced £8.99.

Tanya Landman continues her retellings of classic literature for Barrington Stoke with Frankenstein. We spoke to her to find out more about her latest book.

Frankenstein: A Retelling

By Tanya Landman

Published by Barrington Stoke

This is the latest in a series of retellings for 13+ readers you have written and published with Barrington Stoke, which includes Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights. What is it about approaching such well-known and respected texts in this way that you enjoy, and how did your experience of retelling Frankenstein differ from those that had come before?

With retellings I get all the pleasure of crafting words and sentences into satisfying, tasty prose without having to suffer the anguished self-doubt involved in creating convincing plots and characters of my own.

I’d read and loved both Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights as a teenager and used to spend hours imagining myself into Jane and Kathy’s heads. It was a real joy to be able to put myself back in time and be inside their minds again. Retelling both books was a labour of love.

Frankenstein was different. I confess I hadn’t actually read the book before I accepted the commission from Barrington Stoke and when I did pick up a copy I found it a struggle to wade through! I thought a lot of the prose was difficult and dated and yet I was fascinated by the character of Victor Frankenstein and his truly monstrous ego.

I discovered a really good audio book and listened to it several times (often with my eyes shut) to imagine the scenes unfolding and catch the feel and the sense of the story. And then I noted down all the scenes and ideas that had made my heart race or my skin prickle or made me want to cry and those were the ones I concentrated on. Passages and characters I found dull and uninteresting mostly got the chop. It was a different challenge to retelling Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights but I absolutely loved crafting Mary Shelley’s electrifying masterpiece into what I hope is a version that will grip a modern reader.

Frankenstein is considered by many to be the first science fiction novel, and indeed one of the first major horror novels as well. Many sections are still chilling to read today. What about the story did you think would resonate with a younger audience, and how did you bring those elements to the surface for this edition?

Yes – it’s a pioneering work in both genres and an extraordinary achievement, especially for such a young woman. I am in awe of Mary Shelley.

But for me what resonates (and I think will resonate with younger readers) are the very human horrors and human failings that lie at the heart of the story. When I was in my teens I felt so confused about who I was and where my place was in the world. I wanted to fade into the background and pass unnoticed. But I also wanted to do something notable with my life – like save the planet.

I completely understand Frankenstein’s burning ambition to achieve the extraordinary – to make his life matter, to be famous for something – anything! I think the idea of that one fatal flaw – and all the horrors that result from it – is as relevant now as it ever was.

Frankenstein is a story many young people these days will feel they know, but do you think some elements may be surprising when they read it for the first time?

I think its contemporary relevance will be surprising to some. Most people have images in their head of the Hammer House of Horror monster with the bolt through his neck. They imagine it will be a schlock! horror! screeching violins and nails-on-blackboards kind of a read. Instead (I hope) they will find it’s a fascinating tale about the nature of Man and his position in the natural world – and what makes a monster.

Frankenstein is in many ways a cautionary tale about the obsession with dominating life and the fatal pursuit of progress. Do you think these themes have particular relevance today?

Oh yes – absolutely. Man’s desire to subdue and conquer Nature has led us to the edge of an abyss.

Throughout human history there have always been made dictators and despots. But in these days of mass communication we are more aware than ever of how fragile our world is. And the future becomes more perilous ever day because of a few very rich, very powerful people with colossal egos and bottomless pits of ambition.

Are there any other classic novels you’d be particularly interested in retelling?

Yes – plenty. Bring it on!

Frankenstein: A Retelling by Tanya Landman is published by Barrington Stoke, priced £7.99.

Across 2022, Publishing Scotland will be curating a series of online content to tie in with Visit Scotland’s Year of Stories. Each month we will share the features, profiles and interviews that you can find over on their website.

You can visit Publishing Scotland’s Year of Stories homepage here.

During the winter, Publishing Scotland’s #YS2022 themes were LANGUAGE and CELEBRATION.

Each month Publishing Scotland will be offering Publisher Spotlights, so you can get to know some of Scotland’s publishers. Catch up with the latest profiles.

Publishing Scotland spotlight Gaelic Books Council

Publishing Scotland spotlight Vagabond Voices

Publishing Scotland spotlight Acair Books

Publishing Scotland spotlight Scottish Text Society

Publishing Scotland spotlight Hallewell Publications

Publishing Scotland spotlight Arkbound Publishing

Publishing Scotland spotlight Scottish Book Trust

Publishing Scotland spotlight Swan & Horn

Publishing Scotland spotlight Ailsapress

Publishing Scotland spotlight Charco Press

Each month Publishing Scotland hosted features too, including book recommendation lists and author interviews.

Click here to read an interview with Marcas Mac an Tuairneir about his poetry collection Polaris.

To read an interview with Ely Percy about their novel Vicky Romeo Plus Joolz, click here.

To read recommendations on books celebrating a sense of place, click here.

Click here for book recommendations for music lovers.

Click here for book recommendations on friendship.

For recommendations on books that explore big ideas, click here.

For recommendations on Scottish love stories, click here.

For book recommendations that look to the future, click here.

If you want to take part in the Year of Stories, follow the hashtags #YS2022 and #TalesofScotland, or visit the VisitScotland website.

Naomi Mitchison is one of the most fascinating and prolific writers of the 20th century. David Robinson finds her wartime diaries, re-issued by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, as relevant reading as ever.

Among You Taking Notes: The Wartime Diary of Naomi Mitchison 1939-1945

Edited by Dorothy Sheridan

Published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Christmas 1941, and Naomi Mitchison is attending (somewhat reluctantly, no doubt) the United Free Church carol service in Campbeltown. ‘They sang “Stille Nacht”,’ she writes in her diary, ‘and I sang it in German, but of course inaudibly, so that was alright.’

To read Mitchison’s Among You Taking Notes, a selection of entries from her wartime diaries that has just been republished (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £14.99) is to be transported into a world that is only half recognisable. That year’s war news had been unremittingly grim, especially if, like Mitchison, you hated Churchill, scorned Pathé newsreel propaganda, and thought Glaswegians had been completely demoralised by the Clydebank Blitz. That Christmas, in the wake of the sinking of the battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse by Japanese bombers on 10 December, victory was so far out of sight that it was hard to imagine what it would look like. Mitchison herself was clearly uncertain: visiting Edinburgh the previous month, she dreamed of ‘being a member of the first Scottish Parliament under the New Order or maybe the Supreme Soviet of Scotland, working with the others all over Europe.’

She wrote her diaries not for publication but in response to a 1939 request for daily accounts of wartime life by the social research organisation Mass Observation. Nella Last, the Barrow housewife whose 12 million-word diary was turned into the 2006 TV film Housewife, 49 by Victoria Wood (in which she also starred) was another such diarist. The two women could hardly have been more different. While Last was married to a shopfitter and lived in a 1930s semi, Mitchison had an open marriage with a man who was a key player in working out what the postwar welfare state would look like, and with whom she bought Carradale House, on the Mull of Kintyre, in 1937. By 1941, she had published 23 books, including 11 novels, and diary entries in that year alone mention eating sausage rolls with Stevie Smith, accidentally bumping into EM Forster (‘he was kind and woolly as usual’) and receiving both a request to give a BBC talk from George Orwell and a letter from Leonard Woolf explaining that Virginia had killed herself because she feared she was going mad (‘I do sympathise,’ Mitchison wrote. ‘One so often feels like that.’)

As well as being a writer, she was a Haldane, which is another way of saying she came from the most precociously gifted family in Scotland. My favourite example of this (not mentioned in the diaries) involves her scientist brother Jack who, when he was four, fell and had a bloody cut on his head. When the doctor was summoned, Jack asked him ‘Is this oxyhaemoglobin or carboxyhemoglobin?’

Mitchison’s branch of the family owned Cloan country house near Auchterarder (another branch owned Gleneagles), and as she and her husband Dick already had a house in London with a staff of five servants and a nurse, money was hardly in short supply. At Carradale, her household included her six children, their friends, numerous evacuees, refugees, Free French soldiers as well as gardeners and estate staff.

This, then, is one of the least typical wartime diaries you will ever read. Because Mitchison is a fiercely individualistic Haldane – as well as being a feminist, a socialist and a Scottish nationalist – all the traditional markers of British wartime defiance (Churchill’s rhetoric, the Battle of Britain, the Blitz spirit, Low’s cartoons, the ‘miracle’ of Dunkirk etc) don’t register with her – indeed, it’s only when Hitler invades her beloved USSR that she loses her ambivalence about the necessity of war in the first place. To swim against the tide so strongly, you need a strong sense of intellectual self-confidence. For Mitchison, that’s no problem. Here she is, for example, reflecting on sculptor Eric Gill’s posthumous autobiography and taking him to task for his condescending attitudes to women: ‘I am more intelligent than he was, more intellectual, a better IQ, a hell of an intellectual heredity. I can think past him.’

So of course, she goes on to argue, women have sexual fantasies just like men and ‘have an eye for the beauty of their lovers’ bodies’. Of course art should reflect that. Of course women should be able to buy erotic art – just as she herself had been tempted to buy Gill’s wood carving of Mellors in Lady Chatterly’s Lover (‘with all the Gill emphasis on the penis’). And of course there should be love across the chasms of class.

At such moments, we see ourselves in her so clearly. ‘It is always a bore,’ she writes, ‘being ahead of one’s time.’ It’s no idle boast. She was.

But she was also – and this is why the diaries fascinate – the Big House chatelaine. She could and did organise her local Labour Party branch meetings, but realised that if they held them at Carradale, her views would have an unfair advantage in any debate. She was similarly honest enough to admit to herself that although Carradale meant an escape from the threat of being bombed in London, it also meant an escape from the more intellectually stimulating company of her friends there. When she wanted to set up a regular Sunday evening debating society for young locals at Carradale village hall – which she and Dick had gifted to the village – the committee running it turned her down. She stormed out in tears. ‘I was half inclined to say why should anyone like me with a world reputation have to submit to being bullied by a lot of villagers,’ she moaned to her diary.

At moments like that, she wondered what she was doing in Carradale in the first place, as ‘coming up here I move back 50 years from say London or Birmingham’. There were, she noted, ‘plenty of people who are waiting to catch me out’, and if they caught her having an affair with a local man ‘they would condemn me, say I was a whore and leave it at that’. Sometimes, she wondered if locals are taking advantage of her, laughing at her farm management skills and ‘wondering if my various boyfriends are really double crossing me’.

Yet Christmas at Carradale in 1941 told a different story. There were about 30 people for the party on December 21 – fishermen, gardeners, nurses, teachers and foresters as well as farmers and family – and when they switched off all the house lights to play Sardines and Murder, ‘there was a good deal of hand-holding’ as Naomi and Ian the plumber hunted down the murderer. Looking back 80 years, these moments of carefree classlessness shine out. Halloween – when everyone wore masks – was another such time, but even at that 1941 Christmas Day dinner, she’d invited a local fisherman friend and his wife to join the family celebrations (‘Neither of them had ever had turkey before and they were very excited about it’). Doing research into night fishing for her extended narrative poem ‘The Alban Goes Out’, Mitchison had already befriended a number of the local fishermen and had been delighted to be invited into their homes. ‘I would never have thought to be so much at ease across so thick a class barrier,’ she told her diary.

Yet if that class barrier was starting to wear thin, it was as much because of her husband’s work as her own. To explain how, let’s jump forward to Christmas 1942. While Naomi was in Carradale, Dick Mitchison had remained in London, working first with his fellow socialist, the economist (and prolific detective fiction writer) GDH Cole on postwar reconstruction plans and then with William Beveridge, whose seminal report was published in November 1942. The five giants to be overcome on the road to a new and fairer Britain, Beveridge famously pointed outing what became a foundation stone of the British Welfare State, were ‘Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness’.

That Christmas, the tide of war was turning. In October, El Alamein ended a string of British defeats, and monumental battles at Midway and Stalingrad halted the Japanese and Nazi advances. At Carradale, the servants got £2 instead of £1 in their Christmas stockings and there was goose instead of turkey for Christmas Day lunch. There were 18 children at an afternoon party, and when they left at 6.30, all the grown-ups trooped down to the village hall, where Dick Mitchison was to give a talk.

There were 35 locals in the audience, and if you or I had been there, we mightn’t have been too intrigued by its subject – Social Insurance and Allied Services, the formal title of what became known as the Beveridge Report. We might also have found it hard to sit still for the 90 minutes (!) Dick Mitchison spoke, though if we realised its significance we might well have done. Because that Christmas Day 80 years ago, the world we live in – frayed around the edges but still just about recognisable – was slowly being born.

Among You Taking Notes: The Wartime Diary of Naomi Mitchison 1939-1945 edited by Dorothy Sheridan and with a new introduction by Tessa Dunlop, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, price £14.99

Silver Unicorns and Golden Birds is a beautiful new collection of classic Scottish Traveller tales, as told by the late great Duncan Williamson (1928–2007), who is widely regarded as one of Scotland’s greatest storytellers. Recently nominated for the Carnegie Medal, it is both a demonstration of Williamson’s storytelling prowess, and a celebration of the magic and true value of stories themselves.

Silver Unicorns and Golden Birds

By Duncan Williamson

Published by Floris Books

As we approach the height of the festive buying season, it’s easy to lose sight of the real worth of what we gift to each other. Whilst plastic (be it in the form of toys, clothes, games consoles or mobile phones) is guaranteed to end up on most Christmas shopping lists, here are some wise words from Duncan Williamson’s introduction to Silver Unicorns and Golden Birds, as he recalls Christmases from his own childhood.

Around Christmas time my father would say, “Well, thank God, this is Christmas Eve. Come doon beside me and I’ll tell you a story. Now remember, children, any toy I could buy – what’s the sense of buying you a toy when you’ll only break it – it’ll be destroyed in a couple of days. Even if I had the money to afford it. But, this story will last you the entire time of your life.”

My father told me a story when I was only five years old. Now that was seventy years ago! And I can remember that tale the way he told it to me, just the very way. I can visualise him sitting there by the fireside, a young man putting coals in his pipe, you know, smoking his pipe, and all the little kids gathered round the fire; he sitting there telling them a beautiful Christmas tale. Which was far better to us now when I look back than anything he could have bought for us.

Duncan’s father’s words are just as relevant in 2022 as they were when first spoken in the 1930s, and they provide a wonderful reminder that the impact of books and stories can endure for a lifetime. So, in the spirit of gifting, we hope you enjoy this seasonal story, taken from the newly published Silver Unicorns and Golden Birds.

The Hare and the Scarecrow

Once upon a time there was this scarecrow and he’d stood in the field all summer scaring off the birds. After all the harvest was cut and it came near Christmas time, the farmer forgot about the scarecrow and left him in the field. Poor little scarecrow was so sad! No one ever came along and said hello. He just stood there in the field, no one to speak to, just a lonely old scarecrow. Then one morning, just before Christmas, along came a large brown hare, and he stopped beside the scarecrow.

He said, ‘Good morning, Mister Scarecrow!’

And the scarecrow was so glad to have someone to talk to, he said, ‘Oh, good morning, Mister Hare!’

The hare said, ‘Why are you so sad and lonely standing all by yourself in the field when everyone around the world is so happy because it’s Christmas time?’

‘What can I do?’ he said. ‘I’m just an old scarecrow. All the birds are gone because it’s wintertime and no one seems to want to bother with me any more.’

‘Look, Mister Scarecrow, it is not right that you should stand in the field in the cold winter months after spending all summer scaring off the birds for the farmer!’

‘There’s nothing really I can do about it. The farmer has forgotten me.’

The hare said, ‘I know why he has forgotten about you – because he is busy up in his house decorating a nice Christmas tree for his children. He bought his children all these lovely presents for Christmas and tonight they’re going to have a great party. And you, poor scarecrow, are left in the field all alone by yourself after working so hard all summer; so that the farmer could have nice crops of grain and sell these crops of grain for money to buy all these present for his children – and have a nice Christmas party! It is not fair.’

‘There’s nothing really I can do, because I’m just a scarecrow!’

Then along comes a woodland fairy. She hears what the scarecrow has said. She stops aside him, and she too is sorry for the scarecrow.

She says to him, ‘I too am not very happy about this.’

The scarecrow says, ‘Look, there’s nothing I can do… I cannot walk.’

And the fairy says, ‘Yes, you can! Because I am going to put a magic spell on you for two hours tonight and you can do anything you like. You can walk and go wherever you want to go! But remember, you must not talk – or the spell will be broken.’

‘I would love to go to the farmhouse and join the children’s Christmas party.’

The fairy says, ‘You have got two hours to yourself to do what you like!’ And the scarecrow was happy.

The hare said, ‘It’s just right that he should have these things because he’s worked so hard!’ The hare went on his journey and the woodland fairy flew off, left the scarecrow all by himself.

Now the scarecrow stood in the field and rubbed his hands together, said, ‘I don’t want to go too early. I don’t want to go too late; I will just wait till the children begin their Christmas party. Then I will go and join them!’

Back in the farmhouse the farmer was busy putting up the Christmas tree, putting all the presents under and lighting it up for his three children. Then, the scarecrow thought it was time – now it was quite dark, about six o’clock – and the children had begun their party.

So, the scarecrow got down from the stake he was tied to. And when he started to walk, he felt so light and free. ‘Oh, dear,’ he said, ‘at last I’m free from this field!’

He walked and walked till he came to the farmer’s door. He looked through the window and saw the great big Christmas tree. All the children were happy. They had party hats on, they were singing and dancing and having great fun. But the poor scarecrow he didn’t know how to open the door! So, he just sat all alone and wished he could join the children.

But the farmer was so busy with his children helping them, having party games and all the fun, he felt it so warm in the house he said, ‘I think I’ll go outside for a few minutes and get a breath of fresh air.’

The farmer walked to the door, opened it and walked out on the steps. And lo and behold who should be sitting there but the scarecrow! The farmer scratched his head and said to himself, ‘I wonder where in the world did you come from? The last time I saw you, you were down in my ten-acre field scaring the crows. But, you’ve been a good scarecrow to me; you scared all the birds away all summer and you worked really hard. I think it’s about time you should come and join our Christmas party!’ So, the farmer lifted up the scarecrow and carried it inside.

And the children said, ‘Daddy, Daddy! What have you brought?’

He said, ‘Children, gather round, because I have a little friend who comes to visit you!’

And the children said, ‘Daddy, it’s the scarecrow!’

‘I know, children, it’s the scarecrow. But you must remember… come up here till I tell you a wee story. I built this scarecrow myself and I made him nice. I gave him a hat and I gave him a turnip for a head. I gave him hands and legs made of straw and I put him in my field to scare away the birds. If I didn’t do that then the birds would eat all the grain, and the grain would never grow up – I wouldn’t have any harvest. And if I didn’t have any harvest then I wouldn’t get any money, and if I didn’t get any money then I couldn’t buy you children all these wonderful presents and make this lovely Christmas tree. It’s all because of the scarecrow. So, I think it’s about time he should come and join the Christmas party!’

And the children said, ‘Yes, Daddy, we understand. Please, put him beside the Christmas tree!’

So, the farmer carried the scarecrow and put him beside the tree. And the scarecrow was happy to be there. Then the children started to dance and sing, carry on and have their party games. But lo and behold the scarecrow got so excited he couldn’t help himself; he got up and walked on the floor. He started to sing, and he started to dance. And he danced and sang, danced and sang and clapped his hands. The farmer and his children were so taken away with this scarecrow they thought it was magic. They couldn’t believe a scarecrow would do this. Then, forgetting what the fairy had told him, he was just going to tell stories about all the birds in the field that he’s seen… when the clock struck eight and the scarecrow fell on the floor.

The farmer was amazed. He picked him up and said, ‘I’ve never seen anything like this before.’

The children said, ‘Daddy, please, put him beside the Christmas tree again… he must be a magic scarecrow!’

And the farmer said, ‘No, he is not a magic scarecrow; he is just an old scarecrow. But he will never again stand in a cold field in the winter months. When all the harvest is off the field and all the birds have flown away for the winter, our scarecrow will join our Christmas party – every year!’

The children were so happy and excited they said, ‘Yes, Daddy, please, let’s have the scarecrow for next Christmas!’

‘Right, children,’ he said, ‘have your party!’

The farmer carried the scarecrow and put him in the shed, shut him up for the rest of the winter till the next summer came along. Then he placed him back in the field again. And the scarecrow was happy, for he knew he’d heard the farmer saying that he would join the children at their Christmas party next year. The scarecrow looked forward to it.

And that is the end of my wee story.

Silver Unicorns and Golden Birds by Duncan Williamson is published by Floris Books, priced £12.99.

Teenager Max’s life changes forever when he loses his hearing in a boating accident on a remote Scottish island. As he looks to make sense of his new life, and adapting in school, he begins to notice something strange and sinister happening to the islanders around him – a secret government test programme utilising the wind turbines, and it must be stopped. Victoria Williamson dives deeper into the inspiration of her book with Books from Scotland.

War of the Wind

By Victoria Williamson

Published by Neem Tree Press

When I was growing up, I always found the sight of man-made structures slightly creepy.

Until the age of five, I lived in Anniesland in Glasgow, and from the hill at Dawsholm Park, there was a view across the city which was dominated by the two towering gasometers of the old Temple gasworks. I don’t know why the sight of these two looming metal structures made me shiver uneasily as I was playing in the sandpit or on the swings, but I think I associated them with something other-worldly, something not quite human. They seemed somehow beyond my understanding, and therefore sinister.

I had the same feeling about other man-made structures I came across around Glasgow as I grew up: the rickety old Spider Bridge connecting Kirkintilloch and Lenzie, the humming pylons that crisscrossed the fields south of the Campsie Hills, the extra-terrestrial form of the Bearyards water tower in Bishopbriggs. An avid reader from an early age, I began to associate those structures with the science-fiction books that I loved to read, particularly with the alien-spaceships from War of the Worlds and The Tripods series, and with human experiments with technology that went wrong. When wind turbines started appearing across the landscape, I knew that they’d one day make an appearance in one of my novels. Even though I support green energy initiatives, I never quite managed to conquer my early misgivings at the sight of the imposing metal structures that loomed ominously through the mist on foggy days, and glinted eerily in the sunlight on bright mornings. I knew that when they made an appearance in one of my books, the turbines would serve a malevolent purpose.

The seeds of War of the Wind were sown early in my childhood by these misgivings around artificial structures of concrete and steel, but the characters who appeared in the final novel took much longer to develop. Growing up, I had little direct experience of children with disabilities, either in school or in novels. It wasn’t until I was already at university in the late nineties that the debate about inclusive education really got underway – up until that point, children with additional support needs had been excluded from mainstream education, missing out on opportunities to learn alongside non-disabled peers in inclusive environments that would have been beneficial for all children. Fortunately, by the time I returned to university and trained as a primary school teacher myself, inclusive education had become the norm, and specialising in teaching children with additional support needs within mainstream settings, I had lots of opportunities to help children engage with each other. It wasn’t always a straightforward experience, as children without disabilities or a disabled family member themselves could sometimes bring prejudiced opinions to the classroom from outside.

One thing I found that really helped overcome these misconceptions about what disabled people were able to achieve, was positive role models in children’s books. When I was young, disabled characters rarely appeared in books or on TV, and when they did, it was usually in a token or ‘sidekick’ role. The last fifteen years has seen a much greater understanding from the publishing industry of the need for inclusive books where all children get the chance to see themselves in heroic starring roles, which has been immensely helpful for teachers trying to promote inclusivity in their classrooms. It was seeing this need for visible representation in fiction, coupled with my own experiences of teaching children with additional support needs, which led to the development of the four main characters in War of the Wind – Max, who loses his hearing in a boating accident, Erin, who has been deaf since birth, Beanie, who has Down’s syndrome, and David, who has cerebral palsy. Like a number of similar mainstream children in real life, Max has some misconceptions about disability he needs to overcome, and readers go on a journey with him through the book as he learns to accept his own disability. Through his eyes, they see the assumptions that other islanders make about Max due to his hearing loss, as well as the assumptions Max himself makes about the other children in his additional support needs class.

These journeys of understanding are ones we all need to embark on to help create a more inclusive world, confronting our prejudices and preconceived ideas. In War of the Wind, this journey of understanding is coupled with the sinister tale of a wind turbine experiment gone wrong, giving the main characters the opportunity to showcase their abilities as they attempt to stop the malevolent scientist, Doctor Ashwood, before his secret weapons trial has tragic consequences. This book has been the culmination of my life experiences so far, but like my readers, I hope I never stop learning from the experiences of others and developing my capacity for empathy. And who knows, if I try really hard, then perhaps one day I might even conquer my mistrust of the sinister structures that watch us silently from every hilltop as we go about our daily lives, heedless of their gaze and the messages they whisper on the wind…

War of the Wind by Victoria Williamson is published by Neem Tree Press, priced £8.99.

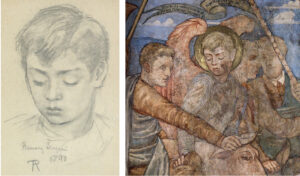

Creative genius, war artist, adventurer: these are just some of the descriptors attributed to Aberdeenshire-born painter and printmaker James McBey. Alasdair Soussi, author of the biography Shadows and Light, tells Books from Scotland about McBey how the creator’s work has come to mean so much to him.

Shadows and Light, The Extraordinary Life of James McBey

By Alasdair Soussi

Published by Scotland Street Press

As I stood over James McBey’s gravestone in Tangier, Morocco, during one parched afternoon earlier this year, I couldn’t help but think of the words the Scottish artist-adventurer had written to his American wife, Marguerite, some ten years before his death in 1959: