‘Do something, Ned Wickham, or I shall think you a Godless man and hard-hearted.’

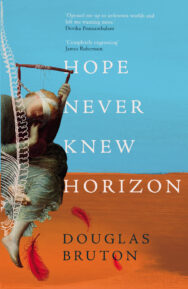

Douglas Bruton weaves three narratives of cultural objects associated with hope, their stories told from the perspective of those marginalised from history: the model, the maid, and the coxswain’s girlfriend, in his new novel, Hope Never Knew Horizon.

Hope Never Knew Horizon

By Douglas Bruton

Published by Taproot Press

Ned Wickham and I don’t ever believe a word that comes out of his mouth. He said I was pretty as sunrises once but then the next day I saw him kissing Brid by the shore and he had a posy of flowers that he presented to her. He said one day we’d be joined together in the church and in front of God and that was a year ago and maybe Brid has changed his mind for he has said nothing of it since. And sometimes Ned has a drink in him, which is not but what all men do, and then he talks pretty and all his whisky-words slopping like water in a full-to-the-brim bucket when it’s carried up steps. And he says also that he has more than twenty pounds in the bank but he still lives with his mam.

Then on this March morning, when he’s back from his shift at the lifeboat, he comes a knocking at my door and he says when I open it that now we are made and he scoops me up in his arms and dances me across the road, me in my slippers and housecoat and my hair not brushed so that anyone watching must think me a poor and common slattern.

‘Made is it?’ I say. ‘When you haven’t two pennies to rub together, Ned Wickham.’

‘Ah but now,’ he says and taps one finger along the bridge of his nose and by that I am to believe he has something up his sleeve, like a rabbit that’s pulled out of a hat or doves that suddenly appear from the folds of a handkerchief.

‘Put me down, Ned Wickham. I am not yours to be carrying around like a pebble you picked up off the beach.’

Then he tells me he’s found a whale, as though a whale might be as easily lost as a penny ha’penny. And like I said, he is just not to be believed, not a single word.

‘Oh, but a great hill of a whale and it’s just lying there kicking its tail in the shallows beyond the harbour. And it has my name on it now, Kitty, which makes it mine. We have been out to see it, me and Blake and Saunders. Rowed out to introduce us-selves and to look into the wet of its great staring eye.’

Maybe I rolled my eyes or sighed or made a sound in the back of my throat, something that told Ned Wickham that I did not believe him, any more than I believed him when he said he once ate a whole roast pig and he could not move from his bed for three days and was why he’d missed our date to go dancing; or when he said he had floated off the ground, all with the power of his mind, and he was light as a feather then and the wind carried him from Rosslare Point to Raven Point in the blink of an eye.

‘Hand on my heart, Kitty, I speak no word of a lie.’

‘A whale is it now. And what good is a whale with the name of Ned Wickham on it, except that the story might get you a drink in the Wexford Arms of a Saturday night when the men there are a wee bittie deeper in their cups and for that a little looser with their wits and their money?’

He sets me on my feet, crooks his arm and offers his elbow for me to slip my hand into, like we’re a couple at a fancy do.

‘There’s money in a whale,’ he says then.

‘Just like there’s money in a bank?’

‘Not just twenty-pounds,’ says Ned. ‘Maybe a hundred, or we can hope for a hundred and twenty.’

And like that he’s floating off the ground again.

‘Get your coat and your boots and we’ll go see,’ he says, and he won’t take no for an answer and he says if I don’t come see, he’ll ask Brid by the shore to come in my place.

Ah, but Ned Wickham knows which cards to play, and so I put my boots on and my coat and I go with him down towards the harbour, but I don’t take his arm, not though he offers me it again and he’s grinning like the cat that’s got the best of the milk and he’s breathing fast as steam trains. And well enough there’s a whale, just where he said it’d be, lying on its side, and it’s in some distress and thrashing the water to foam with its tail and I says to Ned how it’s a crying shame to see any animal so in pain. Ned nods and he says there’s nothing he can do for it and all that beating of the tail will only make the whale stick faster on the mudbank and it won’t ever be swimming in the open sea again and so it might as well fill up his pockets as any other’s.

‘If it was a horse and it was in such distress, you’d take a gun to its head and shoot it, Ned Wickham. The same for a dog or a mauled rabbit. Or a mole that the cat has been at and it has ripped the mole open, head to toe, so all its innards are spilling out and the cat has brought it as a gift for you and there’s only mercy in killing that squealing mole, quick as a lick.’

Ned Wickham recalls hitting that mole with the flat blade of his spade, hitting it so hard it was quiet and dead in an instant and all because I asked him to.

‘Do something, Ned Wickham, or I shall think you a Godless man and hard-hearted.’

All through the night the whale fought for its life. You could hear it moaning, like the wind in a night-gale, and it gasped for breath and slapped its tail down on the muddied water and shifted not a jot from its place out of the sea and on the cruel land.

Then in the full-moon early morning Ned Wickham and several men rowed out to the tired and weakened whale armed with metal rods and knives and wood-chopping axes. When they reached the whale, they clambered out of the boat and scaled the hill of blubber and set about beating the animal to death. The whale let out a cry of anguish and maybe it wept for a tear did seem to fall from its glassy eye – in Ned Wickham’s retelling at least. And maybe Ned Wickham found God again in that moment, for he quickly fashioned a crude harpoon from a long blade and a metal bar and he plunged this makeshift spear under the whale’s pectoral flipper and into its heart and so dispatched it at once. The blood turned the waters red and the cries of the gulls filled the air with such a screaming grief.

Hope Never Knew Horizon by Douglas Bruton is published by Taproot Press in April, priced £11.99

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

The Paris Peacemakers: Q & A with Flora Johnston

The Paris Peacemakers: Q & A with Flora Johnston

‘It’s important to me to get the history as correct as possible, and then I let my characters inhabi …

Fragile Animals by Genevieve Jagger

Fragile Animals by Genevieve Jagger

‘That sound… Big He is at his watching post again today. Overseeing through the haze of His clouds.’