‘These are the shifting sands of storytelling…’

It’s Edinburgh’s 900th birthday this year, so BooksfromScotland will be bringing you books that celebrate the history of the city in the coming months. Firstly, we bring you storyteller’s Donald Smith’s lovely gift book that looks at Edinburgh’s history through its stories, poems and philosophies.

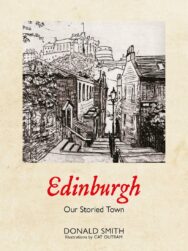

Edinburgh: Our Storied Town

By Donald Smith and Cath Outram

Published by Luath Press

Long before Edinburgh was accredited as a royal burgh, there was a fortress and settlement on the Castle Rock. The first name that has come down to us for this place is Din Eidyn, the fort of Eidyn. Who was Eidyn? God, king, hero, giant? We do not know, but the language is Cymric – what might now be called Old Welsh. Eidyn’s fort was in the Celtic kingdom of Gododdin, which had come to terms with the Roman Province of Britannia, whose shifting northern frontier eventually settled at Hadrian’s Wall.

Above Din Eidyn was what we now call Arthur’s Seat. Again we are in a realm of gods and heroes, not medieval knights or holy grails. Like Benarty in Fife or Ben Arthur in Argyll, the rocky summit was literally a seat where the god could touch the heavens, especially, in Arthur’s case, the Bear star, Arcturus. Like a hibernating bear, Arthur still sleeps below his mountains, waiting on the call to rescue his people.

So, remarkably, a sacred landscape sits in the centre of Edinburgh, with its hilltop seat and ascending terraces still visible. Beneath them is the holy water of Duddingston Loch – Trefyr Lin in Cymric – the settlement by the loch. Weapons and other metal offerings were cast in to the water as sacrifices, foreshadowing the myth of Arthur’s sword Excalibur. The medieval Duddingston Kirk still looks over the loch from what is likely an ancient religious site.

In general, our oldest folklore is about how the landscape was formed. The forces of volcanic fire and then grinding ice which shaped Edinburgh are represented in this lore by a mother goddess or Cailleach (Carlin in Scots) and her rock-chucking giant children. Tradition tells us that this formidable giantess ‘let fart Berwick Law’!

Later theories became more refined, but the core drama re-mains as land and sea, islands and hills, meet in a unique terrain. Arthur’s Seat, the Castle Crag and Calton Hill are remnants of one huge volcano worn down by the ice. To the east, Traprain Law, formerly Dunpelder, and North Berwick Law stand proud on the coastal plain below the long, low range of the Moorfoot and Lammermuir hills. Seawards, Inchkeith, the Bass Rock and May Isle, which sits in the mouth of what was called the Scottish Sea, are prominent. To the north, the Lomonds’ twin peaks – the Paps o Fife – complete the ensemble. From another angle, Edinburgh juts into the sea with Leith at its head, as if continuing the eastward run of the Pentlands which also extend westwards like a recumbent dragon.

The old stories, like later history and literature, are also formed by that interaction of sea and land. The legends of Edinburgh’s ‘Castle of the Maidens’ nod across to the Isle of May or Maidens, blending Celtic priestesses with early Christian saints. It was the sea which brought the Romans to Edinburgh, establishing a major port and fortress at Caer Amon – now Cramond. Though the Romans remained an occupying power, never absorbing Scotland into their empire, they had great influence on the tributary kingdoms like Gododdin. Their most lasting legacy was the spread of Christianity, and the fort by the River Almond later housed a church.

A dramatic story from this period is best viewed from Arthur’s Seat. Tennoch or Thenew (later known as the biblical Enoch) was the daughter of Loth, king of Gododdin, who gave his name to the Lothians. He decreed that Tennoch should marry her cousin Owen, Prince of Strathclyde, sealing a royal alliance between the Cymric kingdoms. But she refused, having come under the influence of women missionaries from Ireland. They offered a radically different path for women in a patriarchal culture. Enraged by her disobedience, Loth sent Tennoch into the Lammermuirs to labour as a swineherd. But her resolve was unbroken.

Owen, the story relates, came to claim his rights as a betrothed Prince. Later hagiography piously beat about the bush, but rape ensued and Tennoch fell pregnant. But still she resisted marriage. She was brought back to Traprain Law and sentenced by Loth to death by stoning. But, in biblical mode, the people refused to carry out the cruel sentence. Next, Loth ordered her thrown from the cliff in a ritual chariot. But the axle did not break, and Tennoch reached the ground bruised but alive. Lastly, stubborn old Loth had her cast off into the Forth in a coracle without sail, oar, food or water – an especially cruel, slow death in Celtic culture.

But as the coracle drifted seawards out of Aberlady Bay, it was followed in procession by seals, fish and porpoises, so that no sea harvest was ever landed at Aberlady again. The coracle went out with the tide, but beached on the May Isle, where there was the freshwater Maidens Well. In this way, Tennoch survived until her little craft could be borne upriver by the tide, landing eventually in the darkness at Culross. She gave birth to her son on the beach, stirring the embers of a fish-smoking fire that had been smoored by the monks of St Serf’s community. They found mother and baby alive in the morning. The child became Kentigern, nicknamed Mungo, the founder of Glasgow. As for Tennoch, her wish to become a leader in the Celtic Church was fulfilled, and she founded a community of women on Inchcailloch in Loch Lomond. Her sacred well was in Glasgow Cathedral, and she was buried below what is still known as St Enoch’s Square.

The same themes of sexual resistance and independence feature in the legend of St Triduana, a woman saint whose principal shrine and burial place was at Restalrig in Edinburgh. Triduana was remorselessly pursued by a Prince, till finally she demanded to know what part of her inflamed his desire. Her eyes, he re-plied, on which she pricked them out with a twig of thorns and handed them over. Subsequently, Triduana’s healing work and her shrines were associated with diseases of the eye.

Triduana had chapels at Traprain, Rescobie in Angus and Papa Westray in Orkney. She may have been the same person as St Medana or Monenna in the Mull of Galloway, and this Saint is connected to the Chapel of the Maidens in Edinburgh Castle. Yet another legend in this cluster has Medanna accompanying St Rule when he brought the relics of St Andrew from Greece to Kilrymont, later St Andrews. These are the shifting sands of storytelling, yet the consequences were real in memory and devotion. Even in the 16th century, pilgrims came to Restalrig in significant numbers, while St Margaret’s Chapel in Edinburgh Castle, successor to the Maidens Chapel, is the city’s oldest surviving church building.

Edinburgh: Our Storied Town by Donald Smith and Cath Outram is published by Luath Press, priced £14.99.

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

Nocturne by Christopher Rush

Nocturne by Christopher Rush

‘It was no lie. We were all sorry. The whole world had lost him. And the whole world had come to mou …

Edinburgh: Our Storied Town by Donald Smith and Cath Outram

Edinburgh: Our Storied Town by Donald Smith and Cath Outram

‘These are the shifting sands of storytelling…’