The Beast on the Broch, a historical fiction adventure for children, is set in North-east Scotland in 799 AD. Depicting Pictish life, the heroine, Talorca, discovers that the mythical beast, depicted on so many stones of that period, is in fact real and living in the broch above her village. But will the beast be friend or foe?

Extract from The Beast On The Broch

By John Fulton

Published by Cranachan Publishing

I wandered into the centre of the village. The peaty smell of cooking-fires hung over the roundhouses, and my stomach rumbled. I’d had only oat cakes again for my morning meal. If it was going to be a while before we had any more fish, I’d have to take a look at the vegetables growing in our plot of land and see if any were ready to harvest. Even a few crisp leaves would make the oat cakes go down a bit more easily.

We had some cows, and some geese, but slaughtering any of them too early was a recipe for starvation once winter came. That was how we lived our entire lives—in preparation for the next winter.

Maybe I’d take a trip to the shore to gather some shellfish. That would be better than nothing.

I found myself standing right in the centre of the village, in front of the clan stone. It was a massive rectangular slab, slightly taller than me and half as wide as it was tall. On one side, facing the monastery, was engraved a circled cross with detailed knot-work. I knew that the cross was old, but not as old as the design on the other side—the Old Woman had told me that the stone was put up when the monastery was built. I walked around the cross to look at the other side. This side showed a much more ancient design. The Old Woman had said that a rough boulder had stood on this site for hundreds of years before the monastery came, and it had been carved with the same design that had now been copied onto the cross-slab. At the top was a crescent, turned so that its horns faced downward, marked with curled patterns and a snapped arrow design in a V-shape. Next was a strange two-bladed sword, of a type I’d never seen, then a snake with a broken Z-shaped spear.

At the bottom was the beast.

There was no mistaking it. The stone showed the beast in profile, with its long horns stretching along its back, its long snout and huge round eye, and tight curls where its feet would be. It was a strange way to depict those curved claws that I’d seen—there was no hint on the stone of just how sharp and cruel they’d looked in reality. I rubbed my wrist where the claws had left an imprint.

Someone in our clan, in the long-distant past, had seen a beast. A monster. And had drawn this symbol, and adopted it as the sign of our clan. What did that mean? If my father’s clan used the salmon on their clan-stone to show that they were salmon-fishers, had my mother’s ancestors been beasts-hunters? Friends of beasts?

I didn’t like the idea of us being beast-hunters.

I had to find out what it meant.

There was only one person in the village who might possibly know—the Old Woman.

The Beast on the Broch by John Fulton is out now published by Cranachan Publishing priced £6.99.

Learn about the origins of Celtic history, including how the Celts used the land, in his informative extract which, through pioneering archaeological evidence, traces the emergence of the continental Celts from the fifth century BC onward.

Extract from The Celts: A History from Earliest Times to the Present

By Bernhard Maier

Translated by Kevin Windle

Published by Edinburgh University Press

Chapter 1: The Beginnings of Celtic History

Life In the Iron Age: Economy and Society in West Hallstatt Culture

The period from the Greek geographers’ and historians’ first mention of the Celts by name until the political decline of the continental Celts, as a result of the expansion of the Roman empire and Germanic pressure, spans the last six centuries BC. Within this period, we meet the Celts in an area extending from the Iberian Peninsula in the west, across present-day France and northern Italy and the Balkans into Asia Minor in the east. The writings of antiquity and archaeological evidence form the main sources of our knowledge of the Celts of that era, but written sources mostly skim lightly over long stretches of time, so archaeology often provides our only information. To archaeology we also owe the greater part of our knowledge of daily life, forms of economic activity and settlement, and the structure of society and religion in those centuries.

The first archaeological evidence of the Celts of central Europe appears in the late West Hallstatt culture, which in the sixth and fifth centuries BC extended from southern France across Switzerland into south-western Germany. The material underpinnings of this civilisation were provided mainly by agriculture and animal husbandry, but crafts and trade were also important. Evidence of these areas is seen clearly in archaeological remains, and from these we can also draw valuable conclusions concerning the organisation of society, the world-view and the religious outlook of the period. Naturally, the environment in which the early Celts lived differed in many respects from our own. Compared with modern conditions, the landscape they inhabited was largely untouched, except for larger settlements. There was no developed network of land routes, and natural watercourses provided the chief means of transporting merchandise. No streams and rivers were controlled, and vast forests harboured a great variety of animals. The mobility of the greater part of the population was limited, and most people’s lives ran on well-defined tracks and within a relatively restricted cultural area.

Map 1 Celtic sites in Europe

With regard to land use, the early Celts of central Europe belong in a tradition that can be traced, using archaeological deposits, from the Neolithic, through the Bronze and Iron Ages, and into the Middle Ages. The wooden plough was introduced into early European farming as far back as the third millennium BC, and the Celts knew a much improved version with an iron ploughshare. Crops such as barley, rye, oats, emmer, spelt and wheat, fibrous plants such as hemp and flax, and legumes such as peas, lentils and horse beans were cultivated, as well as woad for dying fabrics.

The most widespread domestic animal of the period was the ox, which could be used as a draught animal in the fields and for transporting heavy loads. The meat was eaten and the hide made into leather, while the cows provided milk and butter. Pig-rearing was most significant inland, as woodland pasture was the pig’s most important food source until the introduction of the potato in the early modern age, and herds of swine could be kept only close to large beech and oak forests. Bone remnants show that both cattle and pigs were markedly smaller than the corresponding wild species and smaller than modern breeds, a fact which is attributed to the difficulty of caring for the beasts during the winter. Goats and sheep were less widespread than cattle and pigs. Sheep were reared mainly for their wool and played only a secondary role as a source of meat. Horses served for riding and as pack animals, and probably also figured to some extent in cultic rites, as evidenced by the use of horse trappings as grave goods, as well as by representations of horses. Dogs were probably used as watch and guard animals, and to control vermin such as rats. In addition, according to later accounts by Greek and Roman authors, specially trained hunting dogs were used to track, hunt down and kill game.

Deposits of wild animals’ bones in settlements show the wide variety of animals hunted by the early Celts: in addition to big game such as aurochs, bison, bear, red deer and wild boar, smaller animals such as roe deer, badgers, beavers, hares, wolves, foxes and many kinds of birds were hunted. Hunting, however, was probably motivated by the need to protect livestock or prevent damage to crops, rather than a need for meat. In view of the small returns for the large expenditure of time, hunting must have been mainly a privilege of the upper stratum of society.

The Celts: A History From Earliest Times To The Present (Second Edition) is forthcoming in December from Edinburgh University Press priced £19.99.

Bob Whittington deftly demonstrates that, throughout history, conquests, defeats, power struggles and pride have all been orchestrated through our long-standing obsession with money. In this extract Whittington explores the Iron Age, and the dominance of the Romans in Britain, to map out how currency has evolved through the ages.

Extract from Money Talks: British Monarchy and History in Coins

By Bob Whittington

Published by Whittles

Introduction

Ever since the first coin was struck from electrum (an alloy of gold and silver), probably around 600 bc in Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), we have been obsessed with money. Coins tell us about kings and queens; they mark the transfer of power, and they trace the relationships and influences of neighbouring countries between and on each other. For collectors they are objects of beauty and value; in days gone by they would have been worn as adornments and jewellery. For our story they are the signposts along the way as ancient Britain struggled from being an island of independent warlike tribes, fighting for survival among themselves and from outside invaders bent on pillaging and conquering, to a nation which would eventually have imperial ambitions of her own. Monarchs have minted it and manipulated it, hoarded it and squandered it, but all have relied on money as they campaigned to acquire lands and establish their right to the throne. In modern times coinage has been used to mark special occasions rather than to signify and underline authority and power.

Coins are the tell-tale evidence throughout history of conquests and defeats, of power struggles and pride. They also mark changing attitudes and values – how we moved from bartering for goods to cash for everything, from buying bread to bribery. Once they were rare, rough and ready, and had to be weighed to calculate value; today they are milled, engraved, and polished. In time we may do without coins altogether in our electronic and digital world, or we may even revert to bartering once again as some do today, trading what they have or can grow in exchange for items they desperately need but cannot afford to buy with money.

Money Talks traces British history through the one thing that has come to dominate our lives – hard cash. It looks at what was happening to the country as it emerged from its early history and royal struggles with cash flow problems to modern times, and sees what the thrymsa, the penny, and the groat have to tell us about those times and the people who used them. It may now be decimalised, it may even move virtually at the swipe of an electronic card, but money has survived for more than 2,500 years, rising and falling in value, changing in shape and size, and merging into a continent-wide single unit. The coin will go on talking, telling its own unique tale about the lives we lead, the challenges we face, and the dreams we are trying to turn into reality.

Iron Age – Roman Britain

Hard as many Britons might find it as we rail against Europe and its perceived interference in our way of life, clinging proudly to our independence as an island nation while conveniently forgetting how often we have been invaded, the first coins we used were actually from what is now France. They were minted by a Celtic tribe in Belgica. The Belgae was a loose grouping of tribes with different ethnic origins – those in modern-day northern France were Celtic Gauls.

The period we refer to as the Iron Age stretches from 800 bc to as late as ad 100, well into the Romanisation of Britain; in Scotland, which the Romans tried and failed to conquer, it reaches into the fifth century ad. During this time the Celts were the dominant group in north-west Europe, eventually arriving in Britain around 100 bc. To add insult to injury as we watched Greece stumble under the burden of impossible debt in the twenty-first century, that first coin was a copy of the beautiful gold stater of Phillip II of Macedonia (382–336 bc), father of Alexander the Great. Britain, although of course it only became a united country under that name by the Act of Union in 1707, was a long way behind. Even when the first coins called potins were cast by metallurgists in Britain around 80 bc, probably by the Kentish Canti tribe, the workmanship was rudimentary by comparison with the stater.

The technology for producing the potin would have arrived with the first waves of Belgic invaders, who settled in present day Sussex, Berkshire, and Hampshire. The coin was an alloy of bronze with a high percentage of tin – there was plenty of alluvial tin to be found in south-west England. At this stage the notion of stamping a leader’s profile on a coin had not started, and typically a god like Apollo would feature on one side with a bull, a boar, or a horse on the reverse.

One of those tribes of invaders, the Atrebates (‘settlers’), stood up to Julius Caesar as he fought his way through Gaul, providing a formidable force of 15,000 men. Discretion being the better part of valour, Caesar backed off and waited until the opposing soldiers had drifted back to their farms and settlements before picking them off one by one, finally defeating the Atrebates, who had joined forces with the Nervii and the Viromandui among

Gold Stater, Phillip of Macedonia

Potin Iron Age–Roman Britain

others, at the Battle of Sabis in northern France in 57 bc. Caesar appointed Commios as ruler of the Atrebates and sent him as his envoy to Britain in 55 bc, in advance of his first expedition to try to persuade the Britons not to resist his invasion. However, Commios was promptly captured by the Britons, who hoped to dissuade Caesar from attacking. Of course, that plan failed, Commios was released, and he went on to help Caesar’s legions resist further attacks. Commios excelled again during the second Roman expedition to Britain in 54 bc, when he negotiated the surrender of Cassivellaunus, the chieftain who led an alliance of tribes against the Romans. Commios was left in charge and in due course declared himself King of Atrebates, controlling a territory comprising present-day Surrey, West Sussex, and Hampshire.

Money Talks: British Monarchs and History in Coins by Bob Whittington is out now published by Whittles priced £16.99.

The Hebridean island of Iona has a long-standing and unique spiritual history. These visual extracts give a glimpse into how the island’s iconic Abbey has been at the forefront of Christian pilgrimage from St Columba’s arrival in AD 563 to the present day.

Extract from A Pilgrim’s Guide to Iona Abbey

By Chris Polhill

Published by Wild Goose Publications

A Pilgrim’s Guide to Iona Abbey by Chris Polhill is out now published by Wild Goose priced £7.50

Experience a new history of Scotland told through its places. In Who Built Scotland authors Kathleen Jamie, Alexander McCall Smith, Alistair Moffat, James Robertson and James Crawford pick twenty-five buildings to tell the story of the nation. In this extract Kathleen Jamie embarks on a highly sensory exploration of the mysterious broch on Mousa, one of the many islands in Shetland’s archipelago.

Extract from Who Built Scotland

By Various Contributors

Published by Historic Environment Scotland

Mousa Broch: Stone Mother by Kathleen Jamie

It’s half past ten at night in mid-July, and in the far north-west the sun rides low on the horizon, sinking amid sashes of ruby and crimson-tinted cloud. In the north-east, the cliff called the Noup of Ness stands silhouetted against a sky that is not quite dark.

On the pier at Sandwick waits an earnest group of about 40 people. We’re almost all middle aged, almost all visitors to the islands judging by our accents and languages. Some carry digital cameras, and torches we are requested not to use. No flash, no bright light, please keep torches pointed downward.

But a torch is not necessary. Our eyes soon adjust to the ambivalent shifting twilight the Shetland people call the ‘simmer dim’.

It’s a good business for the local boatman and his crew, ferrying visitors to Mousa and back. It’s only a 15 minute crossing by motorboat. Mostly they sail by day, but for a few weeks in midsummer they offer midnight trips too. The boat is full, the water is sheeny, two dark-eyed seals watch our progress.

Mousa Broch © Historic Environment Scotland

The island of Mousa has been uninhabited for the last couple of centuries. A couple of miles long and a mile wide, now grazed by sheep, it’s tucked in against the east Shetland Mainland. When we reach its jetty and look back across the Sound, we see a few streetlights gleam, In the distance, southward, Sumburgh Lighthouse sends out its measured flash.

Having disembarked, we form a long straggle following the shore southward. As we climb over a stile, cross a burn, walk through a damp hollow, the sound of the waves seems louder than by day. Snipe are calling from the thick grasses inland. The night is strange, atmospheric. We follow the curve of a bay, then a half mile away, darker than the low land around, see our destination, the brooding tower of Mousa Broch. From that distance, and in the half-dark, it looks like something left over from the Industrial Revolution, a structure both squat and tall – a bottle kiln perhaps. But it’s not industrial, that at least is known for sure. It’s Iron Age, and reputed to be one of the finest prehistoric buildings in Europe. But what exactly a broch is, or was, still remains unclear. In the 21st-century, however, it’s drawing night visitors like a congregation.

* * *

Brochs are a Scottish phenomenon. Hundreds have been registered by Historic Environment Scotland, almost all in the north and north-west, mostly at the coast, but most are just mounds of overgrown rubble. Only Mousa still stands complete. It’s worryingly close to the shore, but the land has eroded since it was built. The land has eroded, 2,000 Shetlandic winters have blown over it, but it’s still there, 13 metres high, and we’re walking towards it in the middle of the midsummer night, as snipe call, and seals sing a mournful song. When we reach it, the broch seems very tall in the half-light, stolid and resolute. Its walls are beautifully made, stone on stone. Local stone, no mortar: this building is an expression of the island itself. ‘I was made here of this place,’ it says, but that’s all it admits to. Now at just a few feet away, we can see that its ancient stones are softened by whiskery lichen, just visible in the half light.

Tall, thick, inscrutable and round. No windows, of course, but on the seaward side there is a single low and irresistible entranceway.

You have to duck, and feel your way in along a dark passageway. Halfway in are holes where a bar would have slid behind a door, and after two or three metres more you can stand, finding yourself at the bottom of a great stone well. A cylinder of stone. Just a few fellow visitors have come inside, speaking in whispers, and we’re all perched on a stone bench at the edge of a central circular yard. It’s gloomy, probably even in daylight, the sky is a disc of grey high above. Again, it’s the stonework that amazes. Mousa has the classic broch features: its base is monumental but built on that solid foundation are double walls, one inside the other with a stack of ‘galleries’ running up the landward side – openings in the inner wall which lighten the structure. Up they go, eight or nine. On the ground floor are dark and eerie openings: the lower walls are so thick little rooms or cells have been built into them. There’s a hearth space, a shallow tank, a smell of stone and earth, and silence. And of course, through one of the openings let into the wall, access to a tight stone stairway between the two skins, like a secret.

Who Built Scotland: A History of the Nation in Twenty-Five Buildings, by Kathleen Jamie, Alexander McCall Smith, Alistair Moffat, James Robertson and James Crawford, is available for pre-order. It will be published on 14 September, priced £20.

Colin JM Martin investigates the complex logistics of under water archaeology in this case study of the wreck of the Swan, a Cromwellian warship that sank off Duart Point on Mull in 1653. Martin argues that such wrecks serve as time capsules and give essential insight into not just life on the high seas but, more widely, enables further understanding of how past generations of Scots lived.

Hidden Heritage: The Duart Castle Shipwreck

By Colin JM Martin

Scotland’s historic monuments and archaeological sites are prime attractions for visitors and locals alike. Careful study, preservation and presentation over the years has made them important cultural and economic assets to be cherished and enjoyed now and in the future. Recently a silent and barely noticed revolution has added a previously unsuspected dimension to this precious resource. It is taking place under water, around our coasts and in our rivers and lochs.

The recent publication of an underwater investigation off Mull illustrates the potential of discoveries under the sea. In 1653 a storm hit a Cromwellian task-force while it was attacking Duart Castle, and three ships were wrecked. One was the Swan, a small warship which once belonged to the Marquess of Argyll. Her remains were discovered off Duart Point in 1979 but left undisturbed. Twenty years later erosion began to affect the site and a project to excavate and consolidate the threatened areas was initiated by Historic Scotland. The work was conducted by archaeologists from St Andrews University over the following 13 summers.

Archaeology under water is in most respects the same as archaeology on land, though marginally wetter! Archaeological features are carefully mapped in relation to the natural environment in which they lie. The ability to hover over what is being recorded is an advantage terrestrial archaeologists might envy. In some ways underwater excavation is easier than on land, since careful hand fanning can be used to displace sediments in a controlled way; the merest waggling of a finger being all that is needed to reveal a delicate item without displacing or damaging it.

Once mapped and recorded, wrecks are analysed and interpreted in much the same way as an aircraft crash. How the disaster unfolded is revealed by the evidence, and a reconstructive process follows. In the case of a shipwreck natural factors must also be taken into consideration – the nature and topography of the sea bed, currents and storm effects, sediment movements, and the various influences of plant and animal life. Once these factors are understood archaeologists can work back through the processes, so to speak, and reach conclusions about the vessel before it became a wreck.

The Swan evidently struck Duart Point broadside on, before sliding down a rock face to settle on the bottom, heeled to one side. The keel and much of the hull’s lower structure, pinned down by stone ballast, survived in remarkably good condition. Although most of the exposed upper structure disintegrated and floated away the upper castleworks filled with silt and collapsed, forming a kind of archaeological lasagne which encapsulated parts of the captain’s panel-lined cabin and carvings from the decorated stern. Trapped among it were high-quality items including a pocket-watch, part of a top-of-the-range snaphaunce pistol, and the hilt of a sword wound with gold and silver wire. These almost certainly belonged to the ship’s captain, Edward Tarleton, whose portrait we’ve managed to track down. He survived the wreck, though at least one of his seamen did not. His bones were found scattered among the stern deposit, and forensic examination revealed him to have been a Yorkshireman of about 23 who suffered from rickets in childhood. Apart from that he had been fit and well fed. That he was a seaman was revealed by an abnormality in his hip joints which indicated that he had regularly dropped the last few feet onto the deck after working aloft.

From the ship’s remains we deduced her dimensions, general design, and how life was regulated aboard. Worn pulley blocks and other rigging items suggested the ship was poorly maintained. We learned much about her pumping system, how she was navigated, medicine on board, and how rations were apportioned. From animal bones and other evidence we could show that she provisioned herself locally – probably by forced requisition. We only raised one of her eight guns, together with its carriage, but this provided new evidence about 17th-century gunfounding and how the guns were worked. And we learned much about life on board from a wide range of items – vessels of pewter, pottery, and wood; knives and other tools; lanterns; shoes; and clay pipes. Like shipwrecks of all periods, the Swan is a time-capsule of her era. Each is unique, and all merit proper protection, preservation, and study.

A Cromwellian Warship Wrecked off Duart Castle, Mull, Scotland, in 1653 by Colin JM Martin is out now published by Society of Antiquaries of Scotland priced £25. The report can be ordered online here – if you enter Duart1653 at the checkout you can receive a £5 reduction (offer valid until 31/10/2017).

The wreck is a Historic Marine Protected Area under the Marine (Scotland) Act 2010. Diving visitors are welcome, but it is illegal to damage or remove material, or disturb the surrounding plant and animal life within the designated area. A trail map and information for visitors can be downloaded from www.nauticalarchaeologysociety.org.

Preston Watson was Scotland’s aviation trailblazer who beat the Wright Brothers into the air by at least five months in 1903. This extract places Watson within the wider context of aviation innovation in the early 21st-century and highlights his place – and his hometown of Dundee – in the story of pioneer aviation.

Extract from The Pioneer Flying Achievements of Preston Watson

By Alastair W Blair and Alistair Smith

Published by Strident

Many believe that the Dundee-born Preston Watson (1881–1915) beat the famed Wright Brothers into the air by a margin of several months in the early years of the 21st-century. Eye witnesses interviewed in the 1950s clearly recalled the flight setting off from a primitive landing strip at Errol by the banks of the Tay in the summer of 1903. Watson’s wire and wood flying machine was hoisted by means of ropes and weights into the trees, catapulted with engines running, and flew some 100–140 yards before landing. Encouraged by his success, Watson went on to build two further planes. He joined the Royal Flying Corps at the outbreak of the first World War but was killed in a training accident at Eastbourne at the age of only thirty-four. He was buried on July 5th, 1915 in Dundee’s Western Cemetery. Preston’s brother James campaigned for his brother’s feat to be acknowledged, but the authorities were sceptical. Now, however, Dundee’s first pilot is finally receiving the recognition he deserves.

Abridged Extract from the Introduction

There have emerged a considerable number of designs and actual attempts to fly by individuals in the 19th-century. Some were based on a rudimentary understanding of the physics involved and some resulted in fledgling flight. Some were doomed to failure (often spectacular) and some merely remained as plans which, by modern analysis, might have been capable of flight.

The question of who first achieved powered flight was a matter of great individual and national importance at the time, and some of the rival claiming led to heated disputes. There seems little doubt that it had been achieved in some imperfect way before December 1903, but as is often the case in such matters, authentication is difficult or impossible. In the case of flying, what constituted a ‘flight’ had yet to be defined. Although Jullien flew a clockwork driven model airship in 1850 and Langley flew his steam driven model in 1896, the interest centred on who was first to achieve manned flight, with power take-off (perhaps assisted) in a heavier-than-air machine whose direction and height could be controlled and which ended in a landing (or at least the possibility of one). Then there was the problem of what distance across and above the ground qualified for the term ‘flight’.

One could define ‘flight’ as a powered and manned aircraft lifting off from the ground and sustaining that flight through the air by means of the propulsion, before landing the aircraft in a controlled manner. The distance and height achieved are probably academic, but the important criterion is the sustaining of the flight.

A large enough body of collected experience did not exist at that stage and no independent organisation had the sapiential authority or the credibility to arbitrate any conflicting claims, so anything of that nature would have had to be done retrospectively. The Wright brothers had by far the best documented and witnessed claim to a flight which was piloted, took off under its own power and flew convincingly clear of the ground (for 852 feet in 59 seconds) on 17 December 1903. It was piloted by Wilbur who demonstrated that he had control of lateral stability and climb/descent; and was able to land without too much damage to pilot or machine. Without formal process this was generally accepted as the standard by which other claims would be judged. The speeds, altitudes and effectiveness of control all moved on from then. The Wrights themselves did not consider they had satisfactorily conquered these aspects until 1905 – the year their patent was granted. Even then, they did not demonstrate their ‘Flyer’ in public until 1908.

Subsequent claims to have flown prior to the Wright brothers have been accompanied by less convincing documentation and history has come to accept the Wright Brothers as being the first to achieve the criteria for what now might be regarded as ‘flight’ in the aviation sense. In one sense, it does not matter greatly whether one considers flight was first achieved by du Temple in 1874, Ader in 1890, Mozhaisky in 1884, Whitehead in 1901, Watson in 1903 and many others, or the Wright Brothers in 1903. Without wishing to diminish in any way the determination, genius and bravery of any of these (undoubtedly best documented in the case of the Wright Brothers), it is true to say that they were able to do so working from a foundation built up by others. That view is reinforced by the fact that these men, working largely independently, achieved their aim in some measure all within the space of twenty-eight years. Cayley, Lillienthal, Pilcher and others had brought matters to the cusp of success. But the efforts of the empiricists such as du Temple and Mozhaisky, and even some whose efforts with tie-on or mechanical flapping wings engender mirth and ridicule, made a contribution.

The object here is to attempt to set the achievements of Preston Watson into that context in the hope of giving him the place that the authors and many others feel he deserves in the story of pioneer aviation.

The Pioneer Flying Achievements of Preston Watson, by Alastair W Blair and Alistair Smith, is out now published by Strident priced £11.99. The People’s History, featuring Preston Watson, is available on STV Player here.

With a career in heritage conservation spanning over 30 years, Ian Mitchell Davidson draws on his expertise to ask ‘whose heritage is it anyway?’ in this thought-provoking article. Writing that the stories that frame Scotland’s rich history belong to everyone, Davidson believes that the challenge is to try to reflect that heritage as clearly, and as authentically, as possible.

Extract from A Heritage In Stone

By Ian Mitchell Davidson

Forthcoming from Sandstone Press

A Heritage In Stone: Whose Heritage is it Anyway?

“Let’s ask Ian Paisley. He’s the nearest thing to the Covenanters today”, in the brief and telling silence that followed I could hear the trees rustle in the gorge at Killiecrankie, just outside the window.

There was an anniversary on the horizon of the Battle there and as the National Trust for Scotland’s Conservation Manager and Deputy Director for NE Scotland I was in a meeting where the manner in which this might be marked was discussed.

The silence moved to dissent and the suggestion was passed over.

“Whose heritage is it anyway?” was what was in my mind.

Heritage influences everything. And those who have influence over how it is portrayed will be influenced by their own history or that of the community around them. The Heritage industry will often try to package and sell an emasculated story to its audience, usually with the best intentions and we know here that can take us.

As a young man I stepped away from Glasgow where I had grown. I had relished the heritage of the working people, the striving for betterment and the willingness to find humour in all things. I detested the sectarianism that blighted and still blights so many lives. Perhaps it was that personal history that brought the devastating effects of the 17th-century religious wars to mind when I drew the line from that story to the troubles in Ireland and the division that still exists.

Author Ian Davidson

In 1983 I found myself in the rural North East, a quiet backwater, though, with the influx of oil workers from around the world, a place that was adapting to change with civility and warmth. Over the next 33 years I worked with the heritage I found there, mainly in a role where I cared for the great castles of Mar. I was surrounded by people and places where heritage could be sensed in the living dialect, the Gaelic and Scots place names and the ancient stone circles sitting in fields bordered by aged dry stone dykes built by farm workers. I could drive through the county and see old men working by hand among fields of neeps. At tmes I would tumble into worn out remnants of the age of the horse that had passed within living memory.

In my years with the Trust I became more aware of the depth of time that could be found the people and the lives they lived.

Heritage is therefore not history, nor is it archaeology either. Heritage is, in one definition, “something immaterial such as a practise or custom that is passed down from one generation to another”.

The collection of stories within A Heritage in Stone are drawn from my experiences in the heritage industry. They tell tales about the people who care for these places, often in the prosaic world of the unknown craftsman and I have tried to do them honour. The heritage is theirs, perhaps more than anyone.

The unknown craftsman may create our heritage over generations but it is the legislators and the curators who shape the story for the present generation.

I have been privileged from time to time to travel and speak at conferences around the world and among the most moving was to Tallinn in both 1991 when part of the U.S.S.R. and 1993 when it had achieved independence. The history of Estonia is that of a small community squeezed between two and sometime more great power blocks. Their heritage therefore includes the history of these forces but it also includes the story of the people who live there and the means through which they define themselves. They have used that story to forge an identity as a progressive liberal democracy, experiences elsewhere are not always so benign.

Conservation is the tool that those who labour in the heritage industry use to try to manage change. Heritage is all about change and the value that we place on the stuff we inherit. I have found it interesting to watch how the custodians of heritage change and adapt to circumstance, whether on the macro scale as with Estonia or the more intimate discussions here in Scotland.

Take as a case in point the Landseer painting “The Monarch of the Glen”. Whose heritage is that? It is a remnant of high Victorian fashionable Scotland. It was painted for and celebrated the landowner who so loved his Scottish playground. This became anathema to many and when it was on loan for display in the Museum of Scotland it was relegated into a far and dark corner. Now, in 2017, it is acquired for the nation and on a ceremonial journey around the country. Why has there been a change? Who is managing this story and why are they doing what they are doing?

The cover of Davidson’s forthcoming book

Whose heritage is it in Palmyra when, hopefully soon, the present horrors are in the past? How will the devastation to the heritage be assessed, will the damage wrought be seen as a legitimate part of the story of the place or will it be hidden or covered or reinterpreted to use the jargon. We shall have to wait.

When I watched the statues being toppled and heard of the deaths of people who cared for them I could not help but reflect on our own story. Statues were toppled in the cathedrals and churches, the battles of the covenanters were fought and in my lifetime the troubles of Ireland were a continuation of those dreadful events. Killiecrankie is part of that living heritage, should the curators, interpreters and legislators shy away from the effects of those ties as they affect us today?

How do we tell that story?

Whose heritage is it anyway was my question. The stories that frame our history belong to everyone and the challenge is to try to reflect that heritage as clearly as possible. A Heritage in Stone attempts to do this through one person’s experience of those who through their labours carry the story forward.

A Heritage In Stone: Characters and Conservation in North East Scotland by Ian Mitchell Davidson is forthcoming in November from Sandstone Press priced £24.99.

Covering the history of Scotland in the period up to 900 AD, Conceiving a Nation reforms our historical perceptions of what has often been dismissed as a ‘dark age’. In this introductory extract, Gilbert Markus examines the important emergence of trade, culture, and empire which collectively circulated goods, people and ideas in the early centuries.

Extract from Conceiving a Nation: Scotland to 900 AD

By Gilbert Markus

Published by Edinburgh University Press

Chapter 1: ‘I will give you nations as your heritage’ (Psalm 2:8)

Trade, Culture and Empire in the Early Centuries

Scotland first appears over the horizon of history not in its own records, but in writings from the Mediterranean world. As early as the sixth century BC, traders from Marseilles (Massilia) were describing trade routes in a periplus, a merchant’s guide to coastal ports and trading routes. The original text of the Massilian Periplus is lost, but parts of it survive in a Latin poem written in the fourth century ad. It is the earliest surviving record of a network of trade and cultural exchange embracing the Mediterranean and north Atlantic coasts of Europe.

Archaeological evidence shows that by the time the periplus was written such networks were already a long-standing feature of life on these coasts, where goods, people and ideas moved freely. The discovery of numerous bronze weapons, as well as tools, buttons and other more mundane objects, has demonstrated trading connections between Scotland and the Continent, as well as with southern parts of Britain and Ireland. A bronze sword found in the River Clyde is a ninth-century BC import from the Continent. Along the southern shores of the Moray Firth and in Aberdeenshire, several finds of bronze goods indicate connections with northwest Germany about 700 BC. In Corrymuckloch in Perthshire, a hoard of bronze objects dated to around 800 BC includes a sword of continental type. In the same hoard a ‘ladle’ points to a tradition in which food and drink were not merely for the satisfaction of bodily needs, nor even an expression of community cohesion, but provided an opportunity for the display of status. Feasting and drinking were ceremonies of power, and bronze swords are the material remains of a social order that probably pervaded most of Europe: a warrior elite in a hierarchical society exercised power by the exploitation of the labour of peasant farmers, expressing their power by their mastery of bronze weaponry, flaunting it by conspicuous consumption and by the use of luxury goods in social rituals and symbols associated with food and dress.

The widespread use of bronze points to a society in which distant communities were connected by trade. Bronze is an alloy of two metals, copper and tin, which do not often occur close to each other in the earth. This means that mines in more or less distant locations must extract their ores and transport their produce to a single place in order to create the alloy. The very existence of bronze, therefore, requires a network of trade, exchange, transport and management. The tin used in Scottish bronze probably came from Cornwall, or perhaps from continental Europe.

Whoever acquired bronze by trade must also have had some form of wealth to give in exchange. The elite swordsmen and feasters of Perthshire must have been able to extract sufficient tribute from their underlings to pay for this metal – though words like ‘trade’ and ‘pay’ may be slightly misleading, and exchanges may have included a range of social interactions such as gift exchange, marriage gifts and symbols of political alliances. All these interactions could provide the impetus for the movement of goods around Europe.

Later Classical writers occasionally quote another Massilian called Pytheas, who wrote in the fourth century BC, referring to the island as Bretannike, though some manuscripts represent the name with initial P- suggesting that he may originally have known the island as Pretania. Pytheas seems to have recorded Orkney (Orkas) in a passage cited by Diodorus (c. 30 BC) in which this is one of the three corners of Britain, the other two being Kantion (Kent) and Belerion, which must refer to Cornwall, where he says that the inhabitants mine and smelt tin, manufacturing ingots which were then transported to the coast of Gaul and from there to the mouth of the River Rhone. These Cornish tin miners and traders were perhaps among the contacts with whom the Veneti in southern Brittany are recorded as trading in about 56 BC, when Julius Caesar dealt with these people. Caesar was impressed by their sea-faring skills and the quality of their ships, and noted that the Veneti were a maritime empire, ‘holding as tributaries almost all those who are accustomed to traffic in that sea’. Their skill and marine power could not save them from his army, however, which, after a siege, slaughtered their leaders and sold the rest of the population into slavery. In sum, long before the Roman Empire showed any interest in the island as a target for colonisation, Britain (including Scotland) was part of a European culture of trade and exchange. The ‘insular’ geographical position of Britain did not make it culturally insular. The island was not separated from the Continent by water; it was connected to it by water. Seaways and rivers were, throughout the period discussed in this book, the most efficient ways of transporting goods, people and ideas.

Conceiving a Nation: Scotland to 900 AD is out now published by Edinburgh University Press priced £19.99.

With Floris Books as our trusty guide, join us on a whistle-stop tour of 4 top reads for getting children into the spirit of exciting historical exploration during #HHA.

#HHA: Making Scottish History Fun for Children

By Floris Books

Floris Books HQ is being battered by wild winds and incessant rain, not only signalling that summer has arrived in Scotland, but that it’s also the start of the summer holidays. School’s out and wee lassies and laddies up and down the country have weeks of freedom ahead of them.

With Visit Scotland’s Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology 2017 well under way, children are being encouraged to spend some of their precious holidays visiting museums, historic attractions and other sites of archaeological interest. There’s certainly no shortage of places to visit from ruined abbeys to standing stones, towering fortresses to fascinating museums. From the Tall Ship at Glasgow’s Riverside Museum to the sweeping pastoral scenes in the Scottish National Gallery, to the shining swords and shields in Edinburgh Castle. There’s a museum to fascinate every child on a visit this summer in Scotland. We’ve even got the hotly anticipated arrival of the new V&A museum in Dundee to look forward to next year.

Now more than ever before it’s important to encourage the next generation to engage with their cultural heritage and explore the world around them. And what better way to build excitement than by reading about all the places you want to visit?

Even if the weather outside is dull, our books certainly aren’t. Popping with vibrant colour, pacy plots and witty jokes, here is a whistle stop top tour of our top four reads to get kids inspired for #HHA17.

1) Max and Zap at the Museum

The perfect picture book for introducing wee ones to the hidden magic in every museum. When Max arrives at his local museum history comes alive (literally!). Will Max, and his sidekick robot Zap, be able to complete his quest to find Mary Queen of Scots’ missing jewels? Inspired by actual museum exhibits (with a special, separate edition created exclusively for the National Museum of Scotland) this lively book whisks young readers on an exciting journey through Scotland’s fascinating past.

2) A Super Scotland Sticker Book

The ultimate road trip sticker activity book, you’ll spot many participating #HHA destinations in here, from the Forth Road Bridge to Loch Ness. Whether children are stuck in a car in busy traffic or indoors on a rainy day, this activity book will have them pondering on places they’ve visited and places they’ve yet to explore.

3) Museum Mystery Squad

Moving mammoths, hidden hieroglyphics, and curious coins – if there’s a mystery to be solved the Museum Mystery Squad are on it. Perfect for amateur sleuths, this fun series charts the many baffling and bewildering cases a junior detective squad must solve when faced with mysterious happenings at their local museum. Mike Nicholson, teamed with Mike Phillips animated illustrations, blow the (metaphorical) cobwebs and dust off of the museum glass and reveal the hidden potential for adventure, excitement and discovery that lies in every museum. Packed with fun quizzes and activities to test your knowledge between the chapters, with fun, dynamic illustrations, these books will engage from the first page to the last.

4) The Boy with the Bronze Axe

When a strange boy in a strange boat, carrying a strangely sharp axe of a type the villagers have never seen before in Skara Brae, conflict arises and as a deadly storm brews and the very survival of the village comes under threat. One of the Kelpies Classics, Kathleen Fidler’s exciting tale of Stone Age Orkney transports us back in time nearly 3,000 years ago. This fascinating and vivid reimagining of Stone Age Skara Brae, breathes life into the ancient soil and remains that have since become a major 21st Century tourist attraction. This escapist adventure will have middle grade readers seeking out their own new adventures in and around the Scottish Isles.

The following books are all available now, published by Floris Books, the current Scottish Publisher of the Year:

Museum Mystery Squad and the Case of the Moving Mammoth

Museum Mystery Squad and the Case of the Hidden Hieroglyphics

Museum Mystery Squad and the Case of the Curious Coins

This month our columnist David Robinson travels back in time to Edinburgh in the 18th-century, when Scotland’s capital was the intellectual hub of the Western world. With Shelia Szatkowski as an illuminating guide, David encounters many new facts about the city, making him look at, and appreciate, Edinburgh in a new (or perhaps more accurately old) light.

David Robinson Reviews: Enlightenment Edinburgh by Shelia Szatkowski

Published by Birlinn

She was a rebel – the “Little Sisters of No Mercy” had seen to that – so when Sheila Szatkowski left school in Northern Ireland, she didn’t want to go to university there. The Troubles were raging, the tribal divisions were deepening, and in those circumstances, a real rebel doesn’t yearn to stay too close to the farm she grew up on near Magherafelt, Co. Derry, and the fierce predictability of the province’s politics. Not when she can go somewhere like, say, Edinburgh.

She caught the airport bus into town, got off at Princes Street and looked south and east, catching her first and always-remembered sight of that “Medieval Manhattan” of Edinburgh’s Old Town ridging the skyline. Then down Dundas Street on the No 19 bus to her student digs in Inverleith Place, and she hadn’t seen anything else as sturdily, stonily refined as the New Town either because, well, who has?

That’s the moment Szatkowski’s love affair with Edinburgh and its history began, and it’s a love that infuses every page of Enlightenment Edinburgh: A Guide, published this month by Birlinn.

For those of us who have lived in the city for decades, her book is studded with the kind of facts that we should perhaps have always known but – embarrassingly – never did. I must, for example, have passed the six huge sandstone pillars at the front of Edinburgh University hundreds of times. I don’t think I ever noticed that each of them is monolithic, or if I did, I thought nothing of it. Yet just look how enormous they are – and tell me how on earth they ever got there from Craigleith Quarry in 1791, when the Dean Bridge wouldn’t even have been built, and they would presumably have had to be taken down into and hauled up from Dean Village. Of course, Robert Adam could always have compromised on his plans for his alma mater. Those columns could have been cut in, say, four-foot blocks, or compacted, as they are at the back of the courtyard not visible from the road. But what would the point of that be? Because Adam was creating this marvellous architectural statement of intent. Seen anything like this in – where was it you’ve just come from? Thought not. Welcome to Edinburgh.

Read Szatkowski’s book and you begin to get a real feel for how the city would have been back then. Those horses pulling the university’s stone columns out of Dean Village, for example, would have noticed the land levelling out as they passed near Charlotte Square. Adam had that project sewn up too, though it would have been a building site at the time. To the south of Charlotte Square, everything down to the Water of Leith – Randolph Place, Ainslie Place, Moray Place remained fields for another 30 years.

Go back 30 years to 1763, though, and you might have been able to eavesdrop on Thomas Somerville, a 22-year-old clergyman, being addressed by George Drummond, the driving force behind the creation of the New Town. They were in the Old Town looking across the Nor’ Loch at the land on the other side, where there wasn’t a house to be seen. “Look at these fields,” said Drummond. “You, Mr Somerville, are a young man, and may probably live, though I will not, to see all these fields covered with houses, forming a splendid and magnificent city.” Drain that loch, build a road across: that’s all it would take. He’d been wanting to do that, Drummond confided, ever since he was first made Lord Provost in 1725.

As Szatkowski points out, “the enlightenment didn’t happen because of buildings but the people who got together in them”, and her little guide always gets the balance right. But whereas many such guides would concentrate on the giants of Enlightenment Edinburgh – David Hume, Allan Ramsay, James Craig, the Adam brothers – Szatkowski widens the field. There’s a reason for that, and he’s a Dalkeith-born barber and artist called John Kay.

Around about 1785, Kay quit barbering to work full-time on what had until then just been a hobby – doing drawings, caricatures and engravings of eminent and infamous Edinburghers or notable visitors to the city. Szatkowski first came across Kay’s work about 200 years later, when she was asked to catalogue all the fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. It was easy enough to find illustrations of the most illustrious – they’d each have paid 55 guineas to sit in Sir Henry Raeburn’s red velvet chair at 32 York Place and have their portraits painted – but what about the rest? That was where Kay came in. “He was the paparazzo of his day, and he’d do a warts and all picture of how people actually looked. Compared to the big names like Allan Ramsay, he was a backwater artist. In just the same way, I consider myself a backwater historian.”

Szatkowski’s one-woman mission to spread the word about John Kay is impressive. Already, she has restored his grave at Greyfriars Kirk, and ten years ago produced Capital Characters, a lovely little taster of Kay’s work, for Birlinn. Now she’s working on a biography of him, but really, she says, there ought to be a museum devoted to his work. I wouldn’t put it past her.

“He has taken over the last decade of my life and I think he will continue to do so,” she says. “Ever since I first came across Kay and realised that nothing was known about him, I wanted to find out everything about him. From that point on, my friends will tell you, 1742 to 1826 (Kay’s lifetime) is all I am interested in. And right enough, if I read a street directory from say 1792, I’ll find I know more people in it than I do now: I’m just so familiar with all the Edinburgh characters of the time.”

Szatkowski is refreshingly modest about her guide to Enlightenment Edinburgh. “It’s just something about Edinburgh to fill that gap between academic history and a Lonely Planet guide,” she says. “At 20,000 words, I had to be quite ruthless in my pruning.”

All the same, for such a small book, it’s taught me a great deal. Here’s a tiny example that links up almost everything in this story. The first great public building in Edinburgh beyond the Old Town, she points out, was William Adam’s Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, begun in 1738. It lives on in the name of Infirmary Street, which was at its front, while what we now know as Drummond Street (named after that visionary Lord Provost of the previous century) was at its back. The Adam brothers would have often passed their father’s impressive four-storey, 228-bed hospital. Maybe they were even tempted to outdo it: the new university was, after all, only a couple of hundred yards away. Yet now, and since the original Royal Infirmary was demolished in 1882, the only signs that it ever existed are a couple of Grecian urns on top of the entrance pillar to High School Yards, just as Drummond Street starts sloping down towards the Pleasance.

Kay wouldn’t have known William Adam, but he would have known his two sons, Robert and John, George Drummond, and a whole host of teachers at the nearby university. He would have known a lot of those eminent Edinburghers who walked that street down to the city’s first Royal Infirmary, and in drawing their likenesses, he was producing a unique portrait of a city. Unique is, of course, a dangerous word to use. But as far as Szatkowski knows, in all of North America, in all of Britain – maybe even anywhere – at that time, there wasn’t anyone quite like Kay, drawing hundreds of his fellow citizens – including at least 30 whom even she hasn’t yet been able to identify.

So if you want a portrait of any 18th-century city in the world, you’d best start off with Edinburgh. You can look at those Grecian urns that still stand in Drummond Street and think about the missing hospital and what the past has taken away. Or you can walk around the corner, look once more at those monumental pillars fronting Edinburgh University – and whole swathes of the rest of the city – and look at what the 18th-century’s glorious dead have left for us, the living, to enjoy.

Enlightenment Edinburgh: A Guide by Sheila Szatkowski is out now published by Birlinn priced £12.99.

Coinciding with the major exhibition on currently at the National Museum of Scotland, Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites, we go behind-the-scenes to find out about how the diverse exhibits – artwork, documents, ornate objects and more – shape understanding of both the ‘Young Pretender’ and ‘the last Jacobite challenge’.

Extract from Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites

Edited by David Forsyth, Principal Curator, Medieval-Early Modern Collections, Scottish History & Archaeology Department National Museums Scotland

Published by National Museums Scotland – Publishing

Prince Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie, on the right) and his brother, Henry Benedict Stuart. © National Museums Scotland

The Last Jacobite Challenge of Charles Edward Stuart – from Chapter 1

We began this exhibition with the imagined scene from court at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in the autumn of 1745. Now the route to claim the throne is laid out in this section. However, before Charles could reap the rewards of taking the capital of his family’s ancient kingdom, he would experience at first hand the excitement of battle when faced with the full power of a Royal Navy 58-gun ship. After only two days at sea after embarking at St Nazaire, the prince found himself in the thick of the first engagement of the ‘Forty-Five’ on 9 July 1745. This was captured in a painting of 1780 by Dominic Serres the Elder entitled Action between HMS ‘Lion’ and ‘l’Elizabeth’ and the ‘Du Teillay’, 9 July 1745, now in the collections of the National Maritime Museum [Cat. no. 144]. Also featured here is a French-style cutlass reputed to have belonged to a crew member of the Du Teillay [Cat. no. 149], which was found in Coire nan Cnamha (‘the corrie of the bones’) in the Western Highlands. This has been lent to the exhibition from the collections of Clan Cameron Museum, adjacent to the seat of the Lochiel at Achnacarry, Inverness-shire.

Unsurprisingly, given the great interest in the story of Prince Charles Edward Stuart and the Forty-Five, this is the largest section of the exhibition, representing the short but crucial period of 14 months. It is also the part of the story around which a large and significant body of material evidence has been amassed; and many of these objects have an additional resonance of an imputed connection, or even a direct association, with Charles himself.

A cluster of objects around the Battle of Prestonpans in November 1745 point towards the later religious interpretation of the conflict. Colonel James Gardiner, who fought and died during the battle, was commemorated by the manufacture of a practical object, namely a snuff box [Fig. 1.10]. The narrative attached to this box is that it was made from a thorn tree that grew near to the site where he received his fatal injuries. Gardiner would later become something of a Christian hero to 19th-century evangelicals. Another, perhaps much cruder, attempt to construct a narrative around an object is a leather-bound pulpit bible alleged to have been taken from the Kirk of Prestonpans by victorious Jacobite troops after the battle [Cat. no. 159]. In an effort to sully the character of the Jacobite army, or in a blatant 19th-century attempt to rewrite history with sectarian overtones, a handwritten note was placed within the Bible as provenance to bolster claims that

… the Highland Army being largely Catholic, brought the Bible from the Presbyterian Church and threw it on a bonfire. It kept falling off and soldiers threw it up again with their broadswords, the marks of which can be seen. It was rescued by a young girl who was a servant at the manse and remained in her family until a descendant presented it to the Revd Walter Muir, then a Presbyterian minister in Edinburgh.

This is an unusual example of the deliberate construction of an anti-Jacobite relic which, given its connection to the Presbyterian Church, may be considered somewhat contradictory.

The inclusion of contemporaneous documents in the exhibition brings a more immediate sense of language and opinions of the time, copper-plate handwriting notwithstanding. Such objects bring their own set of challenges, as their material integrity must be ensured while on display for such a long period. We include documents that chart the propaganda war, such as a government proclamation offering a £30,000 reward for the capture of the prince [Cat. no. 147] and a counter proclamation [148] from Charles, forced by his supporters to place a similar price on the head of George II, payable to anyone ‘who shall seize or secure the Person of the Elector of Hanover’.

On a more personal level, among the documents borrowed courtesy of the Drambuie Collection of William Grant and Sons is a contemporary manuscript transcription of a letter from Charles to his father with news of the Jacobite victory against the forces of General John Cope at the Battle of Prestonpans. This letter has enabled Museum staff to re-examine some of the claims around objects in our own collections, including a lady’s fan [Cat. no. 184] thought to have been used at the ball at Holyroodhouse to ‘celebrate’ the victory at Prestonpans. Indeed it is unlikely that such a ball took place, for the text of the letter reveals that any displays of ‘public rejoicing’ were expressly forbidden by the prince:

They might have become your friends & duti-Full subjects when had got their eyes open’d To see the true interest of their Country which I Am come to save not to destroy; for this reason I have discharged all public rejoicing…

Glasses, medals and snuffboxes were vehicles for secret messages between Jacobite supporters. © National Museums Scotland

Glasses, medals and snuffboxes were vehicles for secret messages between Jacobite supporters. © National Museums Scotland

Bonnie Prince Charlie’s canteen of cutlery, left behind at Culloden after the battle. © National Museums Scotland

Glasses, medals and snuffboxes were vehicles for secret messages between Jacobite supporters. © National Museums Scotland

The exhibition Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites is at the National Museum of Scotland 21 June–12 November.

The accompanying book, Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites, is edited by David Forsyth, Principal Curator, Medieval-Early Modern Collections, Scottish History & Archaeology Department National Museums Scotland. The book has specially commissioned essays from historians and curators from a variety of disciplines and brings new perspectives to the history of the exiled Stuarts and their supporters. It also has a catalogue of many of the exhibition’s spectacular objects. Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites is out now published by National Museums Scotland priced £25.

If you enjoyed this feature you might like to read this article, Singing History, exploring how The Skye Boat Song shaped Speed Bonnie Boat from Floris Books which tells the story of the Bonnie Prince for children.

In Bloody Scotland, published by Historic Environment Scotland, twelve of Scotland’s best crime writers use the sinister side of the country’s built heritage in stories that are by turns gripping, chilling and redemptive. Here James Crawford explains the genesis of this unique collection whilst drawing upon his own experience of a time when exploring a ruined castle with friends turned suddenly darker…

Extract from Bloody Scotland

By Various Contributors

Forthcoming from Historic Environment Scotland

Introduction

A number of years ago, I went with a small group of friends to visit the ruins of Castle Campbell in Clackmannanshire. It was a strikingly bright June afternoon: a cloudless sky, no breeze, and the sort of humid, energy-sapping heat that very occasionally and very unexpectedly intrudes upon Scottish summers. The castle sits between two narrow glens in the Ochil Hills, above the small town of Dollar. From the car park, you still have quite a distance to walk – all part of the experience, as a steep path winds up the hillside, with the ruined walls revealed only gradually on approach. That summer the surrounding undergrowth was an uncontrolled explosion of greenery, punctuated everywhere by bright, colourful wildflowers. It was so warm that the castle was blurred in a heat haze. There were no other visitors. We climbed in and out of the ruins, enjoying the dry coolness in the shade of the old stones. The only sounds were our own footsteps, the scratching of grasshoppers, and the lazy hum of bees drunk out of their minds on nectar.

The castle nestles a little in its hillside setting, surrounded by tall trees. When you are there, you can look out and see almost no sign of the modern world. We walked down to the stepped terraces in front of the castle to sit in the sun. And that was when we heard it. A gunshot. In the stillness of the day, it echoed off the hillsides like a thunderclap. One of our group screamed at the shock of it. We all looked at each other for the tiniest instant with genuine alarm. And then we started laughing. ‘Must be a farmer’, one of us said. And we didn’t question it beyond that. A farmer doing the sorts of things farmers do; not that any of us really knew what those things might be. And, within seconds, we had relaxed again. We rested for a while, walked some more around the castle, and then descended the winding path back to our car, the gunshot forgotten.

Well, perhaps not totally forgotten. Because that moment of alarm always stayed with me. It teased with possibility. What if it hadn’t been a farmer, I wondered? What might we have stumbled upon unwittingly? Who was firing the gun? What – or indeed, who – was in its sights? Why was the trigger pulled? The setting that afternoon added immeasurably to the potential for drama: the dog day heat, the stillness, the seclusion. And looming over it all was the castle – called ‘Glume’ before it was Campbell, and set between the valleys of two portentously-named burns: ‘Care’ and ‘Sorrow’. It is a dark, implacable ruin; a survivor; a witness to so much over the half-millennium since it was first built.

So perhaps, in some imagined story, it could have been more than just a witness, perhaps it could have had a purpose too. Buildings and places have ways of getting under our skins, of provoking thoughts, memories and feelings – good and bad. If we had to recall all of the major emotional moments of our lives, all of the highs and lows, and were then asked to plot them on a map, I suspect most of us would be able to do it remarkably easily. You always remember where you were when… Buildings don’t pull triggers. But perhaps they can trigger people to pull them. Perhaps…

That day at Castle Campbell came back to me when I found myself talking to the co-founder of the Bloody Scotland Crime Writing Festival, Lin Anderson, and its director Bob McDevitt, in the Authors’ Yurt at the Edinburgh International Book Festival in August 2016. ‘What if?’ I asked them. ‘What if we asked twelve of Scotland’s top crime writers to write short stories inspired by twelve of our most iconic buildings? What would they think? What would they come up with? What could possibly go wrong?’

This book is the answer.

Prepare yourself for a lot going wrong for a lot of people in a lot of ways in a lot of buildings. Prepare yourself for crimes of passion and psychotic compulsion. Prepare yourself for a 1,000-year-old Viking cold-case, a serial killer tormented by visions of ruins old and new, and an ‘urbex’ love triangle turning fatal. Prepare yourself for structures that both threaten and protect, buildings that commit acts of poetic vengeance or act as brooding accomplices to murder.

Yes, a lot goes wrong. But, of course, a lot goes right too. Because these stories offer a perfect demonstration of the incredible wealth of creative literary talent in Scotland today. Scottish crime writing has carved out a formidable reputation. Our authors can entertain and they can shock. And they are fearless when it comes to tackling many of the issues at the heart of contemporary society, shining lights into some of the darkest corners.

Bloody Scotland, then, is a tribute to two of our nation’s greatest assets – our crime writing and our built heritage. Read these stories and, if you haven’t already, go out and visit the structures and sites that feature. Seek your own inspiration from the experiences, let your imagination wander – and, just like our writers have done, feel that electric jolt of excitement at all the myriad possibilities that Scotland’s places can offer.

But before that, it’s time to relax (not too much), settle down (if you can), and steel yourself for the stories that follow. Take a deep breath. And now read the bloody book.

James Crawford

Publisher, Historic Environment Scotland

Bloody Scotland, with stories by Lin Anderson, Chris Brookmyre, Gordon Brown, Ann Cleeves, Doug Johnstone, Stuart MacBride, Val McDermid, Denise Mina, Craig Robertson, Sara Sheridan, ES Thomson and Louise Welsh, is available for pre-order. It will be published by Historic Environment Scotland on 8 September 2017, priced at £12.99.

Bloody Scotland tickets, including the Bloody Scotland book launch at the opening gala on 8 September and the Bloody Scotland event on 10 September, are now available.

Love it or loathe it, you’ll no doubt have encountered the term ‘Millennial’. In this Q&A editor Hilary Bell talks about what a Millennial really is, and what inspired her to launch crowdfunding for No Filter, a forthcoming collection of essays about Millennials. We’ve also included an extract from No Filter on hopefulness and the Harry Potter Generation.

Introduce yourself to Books from Scotland…

I’ve been working in Edinburgh as a publisher at a small independent press for the past year – I’ve just moved to London to start a new adventure here – but my dream is to return to Scotland one day.

This book is about Millennials. What is a Millennial?

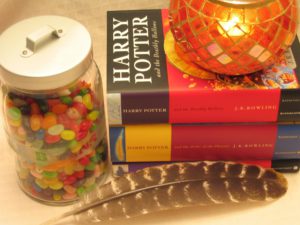

Good question! Lots of different definitions are thrown about, but we’re going with people born between 1982 and 1996. We’re a generation that came of age over the Millennium: internet, Harry Potter, and all.

No Filter editor Hilary Bell

What else is No Filter about?

It’s an essay collection about this generation, and discusses lots of issues that are being ignored by the government right now. There’s essays on bisexuality, on the position of women in Uganda, on depression, Brexit, housing benefits, being non-binary amongst many others. And, of course, there’s an essay on Harry Potter and the effect JK Rowling’s books had on Millennials (you can read an extract from this essay below).

How is this book related to Scotland?

Eight of our authors are living in Scotland and their voices are bringing really important issues to the forefront. The idea was born in Scotland, I developed it while volunteering in Uganda, and now there’s a whole host of international contributors writing for it…

The contributors are: Claire Askew, Nicola Balkind, Chiara Bullen, Cinzia DuBois, Joe France, Becca Inglis, Jonatha Kottler, Juliet Kushaba, Yasmin Lajoie, Eve Livingston, Lynsey Martenstyn, Kasim Mohammed, Christina Neuwirth, Jamie Norman, Xandra Robinson-Burns, Dominic Stevenson and Eris Young… and a few more. It’s a really diverse book covering really important topics.

So the book is an essay collection about Millennials. Why is this relevant right now?

Politically, the majority of the UK is controlled by parties who were mainly voted in by the older generations. In government, issues affecting younger people are being ignored. There’s mental health cuts, we’re undergoing a housing crisis… all of these issues are facing Millennials, and this book is a way of doing something about that. We are the first generation who will be financially worse off than the one which came before. It’s a campaign, in a way.

How did the idea for No Filter begin?

At their annual conference, The Society of Young Publishers Scotland were hosting a ‘pitch war’, with the opportunity here to come up with an idea for a book. This idea just grabbed me, and it got a really good response at the conference. I really wanted this book to be a mode of support, of genuine reflection for all people of our generation. At the time, I was feeling extremely lost – I’d hardly enough money to support myself, and my mental health was suffering. Working with older authors was frustrating as they would often think I was too young to know what I was doing. I felt very alone. I thought, if other young people are feeling like this, I’d want to help and show some support. As we all know, literature is one mode of support, so this book is a helping hand to all Millennials.

Where can I buy it?

No Filter will be published by Unbound, the crowdfunding publishers. You can pledge and pre-order the book here; everybody who pledges to the book gets their name in the back.

Check out an extract from No Filter below…

Millennial, You’re a Wizard: Hopefulness and the Harry Potter Generation

By Xandra Robinson-Burns

Some call us Gen Y, some Millennials, but another term for it is The Harry Potter Generation. Being Hogwarts-educated relates to Millennial characteristics of optimism, confidence, and dedication to a global community. Millennials are often accused of feeling entitled. I’m not about to dispute that claim, rather to say why it’s not such a bad thing – through Harry Potter. Hogwarts for me has always represented opportunity: a promise of a more magical existence. Receiving a Hogwarts letter is confirmation that there is something special stirring inside, that we are different, and that there is a place that celebrates us.

Ah yes. The Hogwarts letter. People think they’re clever for grabbing the attention of Harry Potter fans with the overused phrase: ‘Still waiting for your Hogwarts letter?’. The thing is, if you’ve read the books you should know the rules: you get our Hogwarts letter when you’re 11 years old. If you’re a wizard. If you’re British. If you’re not under 11 or British, why are you waiting?

Ah yes. The Hogwarts letter. People think they’re clever for grabbing the attention of Harry Potter fans with the overused phrase: ‘Still waiting for your Hogwarts letter?’. The thing is, if you’ve read the books you should know the rules: you get our Hogwarts letter when you’re 11 years old. If you’re a wizard. If you’re British. If you’re not under 11 or British, why are you waiting?

What Harry Potter fans long for is not a magical piece of paper in the (owl) post. We already have magical paper – thousands of pages of it, in the pages of the books themselves. These days, of course, you could be consuming the stories on an e-reader, although this digital alternative was not available for Millennials growing up with Harry. For the devoted fans, there wasn’t even a paperback option. Just the hardcover first edition, at midnight, at your local bookshop, in costume, with themed snacks and a trivia competition.

I can’t imagine my childhood without Harry Potter. It came to me when I needed it – I was given the first Harry Potter book as a moving away present when I was 9 years old, and every family move afterwards magically corresponded with a Potter book release. While I moved from place to place, Hogwarts became my consistent home. Summers that should have been filled with anxiety over new neighbourhoods, new schools, and new friends were instead made magical with the anticipation of new Potter books. As a generation, we exercised our hopefulness muscles, constantly having a new tome in our future. I was driven by the need to read and reread, to uncover all the clues, knowing that each new release also meant the beginning of a new cycle, with new answers and new questions.

Xandra-Robinson Burns

These book releases were an experience unique to us, counting down the days until Book 5, 6, 7, an experience that transcended the books and infiltrated our Harry Potter wall calendars in a real, live way. As an introverted child and constant new kid, the series helped me connect with others, through the characters we had in common. All you had to do was comment on my Harry Potter backpack (or t-shirt or toy owl companion) and I would pretty much be your friend. We would bond over whether the toilet was haunted by Moaning Myrtle, and send each other owl post.

My point is that the magic is not in a literal letter, but in what it stands for: it is an invitation to live more magically in our own world.

Edinburgh-based Xandra Robinson-Burns was featured in this recent Guardian article in June 2017.

Publishing Scotland, in association with Creative Scotland, are pleased to present New Books Scotland, a selection of the best books to look out for from Scottish publishers during spring and summer 2017.

You can discover new reads across fiction, non-fiction, and children’s, and if you’re an international publisher, rights are available for the showcased titles. Read the introduction, and view the PDF below, to find out what Scottish publishing is producing for your reading – and rights-buying – pleasure this year…

Introduction

Welcome to the latest showcase of Scottish writing and publishing 2017 for Spring/Summer 2017. There is an energy and dynamism in the current scene – from small presses discovering new talent and taking the risk on significant debuts, well-established writers at the height of their storytelling powers, newly revitalised children’s books and young adult imprints, to the latest in crime fiction. The energy, brewing for some years, and finding new outlets and new audiences, is reflected in this selection of new and upcoming books (fiction, non-fiction, and children’s books) being offered for rights sales.

As the support body for the book publishing industry in Scotland we are keen to see the writers and publishers find new audiences internationally, and our activities – international fellowship, Translation Fund, translator residencies, book fair stands, funding, and marketing, including the BooksfromScotland.com site – are designed to help their efforts in achieving just that. Here are the books you might want to keep an eye out for this year…