Bashabi Fraser’s work is often autobiographical and typically explores the vibrant cross-cultural connections between India and Scotland. In these poems from her latest collection, Fraser affectionately looks back on the relationship with her late mother while exploring the personal, yet also universal, experience of losing a loved one.

Shamsad Rahim

For the Bangladeshi community

You were their mother hen,

Protective and compassionate

Holding them under your generous wing.

For your friends who knew you

You were their full moon

Your broad smile their welcome

That made their hearts sing.

For your own loving family

You were their pole star

Reliable and constant

Who watched everything.

For your colleagues who valued you

You were their corner stone

Your presence an essence

Like a fresh mountain spring.

For your two cherished countries

Of Scotland and Bangladesh

You were a torchbearer

Of eternal wellbeing.

A presence in absence

It was warm Ma, when I left Kolkata

It was 4º the night I arrived in Edinburgh

I left Baba with moist eyes and a longing, lingering look

I met Neil with his delighted smile and sense of relief

In every room in Kolkata, you looked down on me

At every door in Edinburgh, I felt your absence

I tasted your sophisticated artistry in every meal there

I missed the intimacy of affectionate offering at my table here

The gardens had the green sheen of your magic touch there

While here our grass is sheeted under the silence of snowy fingers

Kolkata was troubled with the pressure of its millions

While Edinburgh streets were muffled and deserted

But this time Ma, the Boi Mela1 saw a confluence

As the Scottish Pavilion took centre stage

And Scots made the headlines and mingled with the city

The ghosts in the Scots Cemetery woke up and waltzed

In the corner that is forever Scotland

For the tropical grass has been cut back

To give them a dance floor as they celebrate life on the Hugli

The restoration of their gravestones in a renewal

Of a shared history, which flows like a tide

Between a tale of two cities unfolding

As I journey back and forth

From your spiritual hearth

To the bracing north

Carrying your presence in my very breath

My mother.

1 Book Fair – a reference to the Kolkata Book Fair in 2009 when Scotland was the Theme Country.

Letters to my Mother and Other Mothers by Bashabi Fraser is out now published by Luath Press priced £8.99. You can read more poems from the collection here.

In this bold award-winning memoir, Edinburgh-based author and journalist Chitra Ramaswamy delves into the exciting – yet also at times confusing and overwhelming – experience of pregnancy. In a series of intimate essays she charts the many changes to her body and mind while challenging the wider perception, and portrayal, of pregnancy in society. In this frank introductory extract, Chitra confronts pregnancy’s ‘riddle’.

Expecting: The Inner Life of Pregnancy

By Chitra Ramaswamy

Published by Saraband Books

November

An unremarkable Sunday morning in November. A noirish time of year when nature’s reel turns monochrome and the world becomes as smudged and grainy as old newsprint. Sombre November, as TS Eliot called it. The last gasps of another year. On the morning dog walk the leaves were pockmarked from an excess of autumn and had lost their florid complexion. They were beginning to blacken now and stick to my shoes as though slick with a thin layer of oil. It was the eleventh month of the year, though Novem means nine for it was the ninth month in the Roman calendar. Nine months. A clue dropped by a season, like so many leaves.

And so with all this promise of death I found myself taking a test proposing life. A frightening test, though perhaps there is no other kind. A test taken by oneself in the privacy of one’s own bathroom towards the end of another year. A test whose result is revealed not by a mark on a page but by a stream of one’s own bog-standard urine. A test for which there are only two results. Either life is there, burrowing in a place as close to you as your own heartbeat yet as mysterious as the inside of a mountain, or it is not and life, the other kind, goes on. How very simple. And how brutal too.

Like however many millions of women before me and who knows how many in tandem, I squatted, hovered, took aim and waited for a blue cross to materialise in a tiny window of possibility. I had done this a few times in my life. In Glasgow in my early twenties when my partner at the time had just moved to London and I felt vengeful and very alone. The result? Relief. Or more recently in Soho, in one of the new breed of budget design hotels characterised by receptions without people and rooms without windows. That time? Disappointment. On both these occasions, the result had been negative. Life, the other kind, had gone on.

This time was different and as is often the case with major moments, I knew before I knew. I had eaten oysters twice in the previous week – unusual in itself and almost willful in retrospect – and felt seasick as each sup slid down my throat. I had drunk whisky, smoked roll-ups and sung along to the Proclaimers in Edinburgh’s The Port O’ Leith, a floating pub, which in its own salty way is no less glamorous than sipping Bellinis in Venice or going for bagels in New York. But instead of feeling the euphoria that comes from belting out ‘sorrrrroooowwww’ with the bonfire of Laphroaig on your breath and the scent of the Firth of Forth on the air, I felt jittery. Five days previously, there had been a small rusty mark on a pair of pants, a question mark written in blood. It was enough of a hint for me.

And yet I had cause to doubt what is known in the business of trying to conceive – and one soon discovers that it is first and foremost a business – as an implantation bleed. That is, the moment when the ball of cells that goes by the dramatic name of a blastocyst burrows into the wall of the uterus, the most minuscule of plants taking root and making the ground shed tears of blood in response. Little blastocyst blasting its way into the world, so small and uncertain it has yet even to become embryonic.

My partner and I had been trying to make this everyday miracle happen for almost eighteen months. It had not been easy for us. We were two women for a start. The story was the kind of romantic comedy that would never get made, with all the madcap races across cities and highly charged encounters in hotel rooms you might expect. Stories that were good for dinner parties but bad for life. We had already done so much. Our preparation had been flawless; all we lacked was an outcome.

To start, a civil partnership to ensure we would both be the parents of a baby that might never be, a leap of faith that no heterosexual couple is required to make. Bizarrely, this needed to take place not just before birth but before conception, making the most private of acts a matter of public interest from the outset. And so it went on. Three donors and three corresponding excruciating encounters up and down the country. Home insemination kits bought off websites with deflating names like prideangel and fertilityzone. Blood tests at the GP’s to ensure I was fertile. Dispiriting monthly trips to buy yet more ovulation tests, cruelly addictive (and expensive) little sticks that so resembled pregnancy tests I began to feel dumbly thrilled when they showed up positive. Then a growing obsession with donor profiles on international cryobank sites, where you can buy sperm by the syringe and have it delivered to you in a hissing nitrogen tank, which if nothing else sounds like the birth of a post-modern superhero. And finally, a number of exchanges in a series of hotels with neither windows nor souls.

Every month, these brief encounters grew at once more workaday and strange. They began to gain an air of desperation, of waning passion and lost faith, sentiments that afflict most clandestine hotel trysts in the end. And the fact was they weren’t working. Like November, we remained sombre, in limbo, aching for our lives to turn Technicolor, to end and begin again. The frustration that comes when your body refuses to submit to your will grew exponentially, fattening like the foetus it seemed would never be. Meanwhile I grew increasingly defiant towards my own flesh and blood. I knew my body less and less with each passing month, just as we slowly grow to see a partner we no longer love as a stranger. To fail to get pregnant when one badly wants to is to engage in the most treacherous kind of battle: with one’s own innards. We can no more will a baby into our bodies than we can draw an illness out of them.

Now I waited once more. Watched the beads of condensation on the cistern as they trembled, brimmed over and wept. Listened to the pigeon that had taken up residence outside our bathroom window for much of the autumn cooing with the persistence of a clock. Pictured Claire, my partner of eight years, a few feet away in the sitting room with the dog curled at her feet, waiting too. Witnessed the world distil itself, telescoped by anticipation into a chain of beautiful moments. Like words, life has a way of becoming poetry when slowed down.

You must wait three minutes before reading a pregnancy test. The length of a pop song or an ad break. During this time I found myself feigning nonchalance for the benefit of no one but myself, imagining a camera lens hovering above my head as we do when we sense something monumental is afoot. I left the bathroom, paced our hall, allowed myself a Hitchcockian moment of suspense with all its long shadows and discordant strings, and then returned to the scene on which the plot of my life suddenly hinged. Finally I allowed myself a close-up. There it was. The revelation I had been imagining for so long. A moment not entirely unlike the adverts on television with their staunchly white couples flashing white teeth against white backgrounds, making fertility look oddly sterile, as innocent as ordering a salad for lunch. The vertical line was a little less significant than the horizontal, but it was a blue cross nonetheless. And beside it, an idiot’s guide to deciphering the message. + = pregnant. – = not pregnant. A turning point, the kind that is mammoth enough to be experienced twice. First as raw moment, all heartbeat and terror. Second as story: dramatised, edited and reconstructed even as it unfolds.

‘I’m a riddle in nine syllables,’ wrote Sylvia Plath in her 1959 poem ‘Metaphors’. Nine syllables. Nine lines. Nine months. The arc of pregnancy, with its triptych of trimesters, is as meticulously structured as a poem. Though, of course, one cannot break free of the conventions of pregnancy. There is no way to subvert its stanzas. Plath wrote these blackly humorous lines that peter out into quiet desperation when she was pregnant with her first child. The poem is funny in a cruel way: the joke is on her, and on all pregnant women who are reduced to mere metaphors as they rise like yeasty loaves. Plath would remain as ambivalent towards motherhood as she was towards pregnancy for the rest of her short life. How could she not be in a decade when the word itself was riddled with shame? When a pregnant woman was still a walking euphemism? In a family way. In a delicate condition. With child. Enceinte. Expecting.

Plath understood the tricksy nature of pregnancy, its deep and perplexing riddle, its silence as dark as the womb. She understood its peculiar contradiction: the problem of how you can be at your most lonely during the one time in your life when you are never alone. In philosophy the exploration of how a being relates to its world is known as the problem of self. Just think how this problem doubles, trebles, multiplies when there are at least two people inside one body. Plath understood what it was like to all of a sudden, after living with such unthinking ease in one’s own body, feel like ‘a means, a stage, a cow in calf’. She understood the wondrous absurdity of it.

She made sense of pregnancy by travelling beyond experience to a place where only metaphor would do. Plath’s attempt was to write about pregnancy by not writing about it, by veiling it, perhaps even illuminating it, with metaphor. It was all too lonely a place to live in the end. She was imprisoned in the bell jar, an image that in its own way recalls pregnancy too. After all, pregnant women often feel trapped in their bodies, or rather their bodies become the trap. And isn’t the womb, too, a kind of jar, albeit one we cannot look inside with the naked eye, one whose contents remain unseen until the lid is opened.

What, then, is the riddle of pregnancy? How are we even to begin to understand it? To find the right metaphors? Or perhaps even to abandon them: to crack open the jar and spill the contents? To cast aside the sentimentality, sanitisation, science, prescription, self-help, emotionally manipulative doggerel, lies, misconceptions, misogyny, unwanted advice, politicking, and the never-ending slew of news stories that serve only to patronise, petrify or pacify? How do we find some meaningful understanding of one of the most thrilling, challenging and alien experiences of all? To describe what it really feels like to grow a person within a person? To tell the curiously silenced story of how every single one of us began?

Pregnancy. The word both sounded heavy in my mouth and suggested a kind of heaviness. It had something to do with its staccato rhythm, the way it began harshly and then finished with a soft purr, as if it were a pregnancy in reverse. It wasn’t an easy word to speak aloud, just as it wasn’t an easy experience to articulate. This made me like its awkwardness: it suited it. And what of its meaning? In Latin, praegnans translates literally as ‘before birth’. It has long had a significance reaching beyond its description of the gestation of a foetus. There is the sense of pregnancy as carrying weight, depth or meaning. The pregnant pause. The pregnant moment. The pregnant utterance. By the late fourteenth century, to be pregnant also meant to be convincing, weighty or pithy. A pregnant argument was a compelling one. Then there was its sense of fullness and creativity. Its wonderful state of potentiality. I wanted to return to this definition of pregnancy as being ripe with meaning itself. To be pregnant with meaning as much as with child.

Then there was the trajectory of the thing itself. In a time when haste and choice and control meant everything, a pregnancy could not be speeded up. It was a journey characterised by its length, stubbornness and difficulty, and an ascent that had to be undertaken all the way to its peak. There was no veering off course. The journey was laid out before me: charted by nature herself. Though mountaineering seemed the most masculine of sports – the need to conquer, to get to the top and survey the world from its ceiling – here was perhaps the most challenging climb that the body could make, and it was indisputably feminine. I wanted to chart my pregnancy as one might a great journey, follow it as one might a trail. Walk the river all the way back to its source. Find a new route to the summit of Everest. My body would become a map. No, it would become the landscape itself. Its contours would be the topography, each month would become a milestone, each trimester a landmark. I might tick off rare moments with the satisfaction of a birder. I might mark months with the relish of a hiker bagging Munros. I might even enjoy getting lost. And what of birth? It would become the resting place. The end of the line. The top of the mountain. The final destination. The place where the wild things are.

Later that day Claire and I went for a walk in the Hermitage, an ancient woodland straight out of a Grimm’s fairytale and the kind of sheltered place that is particularly prized in a northern city blasted by wind and haar. The kind you burrow into, which seemed apt for that other journey on which I was embarking. In fact, this twelfth-century former hunting ground would bookend my pregnancy. Exactly forty- two weeks later I would wind up back in this deep green gorge, beating the very same paths on the day I went into labour.

Even in Edinburgh, where a daily commute through a medieval town carved into ice age rock makes you somewhat inured to all things old, the Hermitage feels ancient. These are surely the oldest trees in the city, as gnarled and characterful as storybook giants. Ash, beech, sycamore. Weathered, wide, Victorian in age and grandeur. Though wild boar and deer were once hunted here, these days you’re more likely to see locals in Hunter wellies calling on their Labradors, who invariably go by the name of Monty. As usual Claire and I made for an unusual couple, a sentiment so familiar it perversely made me more at home. Like all happy outsiders, I have always felt most myself in the places where I fit in the least. Well, here we were: two women, one Anglo-Indian, one Scottish, walking that most maligned and working class of dogs, the Stafforshire cross. And something else accompanying us too, a secret, a potentiality. Whenever fellow dog walkers asked a question about our dog, only one of us would be addressed, as though it were unfathomable for both of us to own her. If this was the case with a dog, how would we be seen – or rather not seen – with a baby?

We wandered in a daze, barely talking. I felt that odd commingling of excitement and dread that comes with getting what you want. My belly, as flat and featureless as a field, whirled with wish-fulfilment and a sense of the unknown as our dog thundered up the slopes ahead of us in search of squirrels. Everything as it always was, everything utterly changed. I felt too jumpy even to place a hand on my own stomach, which suddenly seemed to belong to someone else. Despite my long-held belief that a woman’s rights override those of her foetus, I felt that perhaps it did.

Our news was still new, as unspoken and frightening as a family secret. We were shocked by it, and this too was shocking, for how can something you’ve been planning so meticulously still surprise you when it comes off? The fact is I had been trying to conceive for so long that I had forgotten the point of it all. I was like the fisherman so stunned by the catch squirming on the end of his line that he throws it back in the water. The ritual of the rod, the river and the lure had so consumed me I had forgotten about the fish. And now that I had come to the end of the line, I realised that, like so many ends, it was only another beginning. This, too, was part of pregnancy’s riddle.

Expecting by Chitra Ramaswamy won the First Book of the Year in November 2016 at the Saltire Literary Awards and is out now published by Saraband Books priced £12.99.

In this guest post by publishers 404 Ink, the editors introduce their forth-coming anthology Nasty Women and, in doing so, demonstrate the uncompromising and upfront ethos of their exciting new imprint.

Nasty Women: The Push Back on Post-Truths

For us at 404 Ink, and many others following a locally and internationally politically challenging year, 2017 is the year to push back against post-truths and champion real experience. Instead of tiring of experts and experience, we were tired of falsehoods, sensationalism, and stories being twisted and contorted by people in 3am Twitter rants. We craved real, personal and unfiltered perspectives on the current political climate through a range of women’s eyes.

In November 2016, the idea of Nasty Women was sparked. 404 Ink’s first book spiralled from the shadow of Trump’s election in the United States of America, where a campaign of hatred, racism and misogyny was allowed to thrive. It started with a simple idea: to reclaim a title, and instead of slapping it on merchandise or Twitter bios, to really explore it. By Christmas, it was fully formulated.

Nasty Women is a collection of essays about being a woman in the twenty-first century. Many of these are voices you won’t hear anywhere else, and are increasingly phased out of public conversations by those who can shout loudest. It’s lucky that we at 404 Ink can shout pretty damn loud.

We revealed the cover and asked for the £6,000 needed to get the book off the ground on Kickstarter on January first. By January third it was fully funded, by January fourth, it soared past £7,000 with the best part of four weeks left to go. This tells us that people want real stories as an alternative to questionable media rhetoric. And we have a whole host of real stories to share with them. Repeal the eighth, Brexit, family, heritage, role models, mental health, disability, hobbies that give you a sense of power, finding your voice – owning your voice.

From the cover design by Maria Stoian

Katie Muriel is a woman of Latinx descent whose family is divided by race, political alliances and more. She writes about what it is to be a woman of colour in Trump’s America, and the realities of how that can tear families apart. Elise Hines documents her life moving around the States and racism she faced, and how she has gradually watched her country go from “hope to grope” in four years.

SimBajwa writes about being the daughter of Indian immigrants and how she wouldn’t change that for the world, where Zeba Talkhani reflects on her identity as a young girl growing up in Saudi Arabia, her identity now living her in Britain, and just what has changed.

Kaite Welsh navigates butch and femme identities, Chitra Ramaswamy considers pregnancy, where Laura Jane Grace of Against Me! chats to Sasha de Buyl-Pisco about her life as a trans woman today, and in the punk community.

Jen McGregor writes candidly about the battles of being a woman in control of your body, taking on contraception and the many battles women face to be informed and make the right choice, which can still be of great detriment to your body.

Mel Reeve tackles the stigma of being the ‘perfect’ survivor of sexual assault and the world’s perception of how you should respond and act. Laura Waddell writes on the experience of being a working class woman, Laura Lam considers her family’s past and keeping the history of nasty, complicated women alive, and Claire Heuchan, also known as blogger Sister Outrider, discusses being a Black woman online.

Joelle Owusu looks at Black fetishisation in her Melanin Manifesto, Nadine Aisha Jassat considers the power of names, Ren Aldridge of punk band Petrol Girls takes on culture’s ability to fight back against insidious attitudes and behaviours, JonaKottler writes on being fat in many countries, and so it continues with many more incredible women documenting their own experiences.

Nasty Women is a collection for people who will not be silenced, in a world where to speak up as a woman and simply tell your story is to be written off, attacked or shut down.

One of the beauties of small indie publishing is the ability to react and act quickly, and there’s nothing more motivating than the political and personal shifts in the past year. Books like The Good Immigrant, edited by Nikesh Shukla, are absolutely vital in pushing back against a hateful rhetoric that is frighteningly uprising globally, and Nasty Women is our small attempt to push with them. In 2017, that’s what 404 Ink will be doing alongside a host of incredible women, and we hope you’ll join us in doing the same.

Edinburgh-based 404 Ink will publish Nasty Women, edited by Heather McDaid and Laura Jones, on 8th March 2017. The video below tells you more about the project and you can pledge to aid publication of Nasty Women here on Kickstarter.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1965253475/nasty-women

In the first ever Gaelic travelogue, take a trip to urban Russia with author Maureen MacLeod who is Producer of the BBC Alba’s current affairs programme Eòrpa. The book’s title, A’ Toirt Mo Chasan Leam, roughly translates as ‘talking my feet with me’.

A’ Toirt Mo Chasan Leam

By Maureen MacLeod

Published by Acair

Moscow gu Yekaterinburg

B’ e seòrsa de dh’fhaochadh a bh’ ann nuair a nochd an tagsaidh aig fichead mionaid gu còig sa mhadainn. Bha cùisean air a bhith cho trang sna seachdainean a chaidh seachad leis na bh’ agam ri dhèanamh ’s leigeil soraidh le daoine. Bha an t-ullachadh seachad – seo a’ chiad latha dhan a’ chòrr dem bheatha.

Cha robh mi buileach cinnteach ciamar a bha mi a’ faireachdainn. Leis gu robh mi air a bhith na mo mhàl, b’ ann a-nis a bha e a’ drùidheadh orm gu robh mi a’ teiche. An robh mi dha-rìribh ag iarraidh a bhith air falbh bho Glaschu cho fada? Dè bu chòir dhomh a thoirt leam? Bha beagan den h-uile càil a-nis na mo mhàileid, cuid dheth bha mi an amharas nach cleachdainn idir! Ach, nach mi a bha fortanach cothrom a bhith agam bliadhna a ghabhail dheth, cuairt a chur air an t-saoghal, ’s mi cinnteach gu fidirinn is gu faicinn iomadh annas, math agus dona.

Ràinig mi Moscow mu cheithir uairean. Leig iad a-steach dhan dùthaich mi, gu talla far an robh an t-uabhas dhaoine a’ tairgse thagsaidhean. Chuir mi cùl riutha sin agus chaidh mi a shireadh rank. Cha robh sgeul air a leithid. Mu dheireadh, às dèidh bhith cur charan greis, ghabh mi lioft bho seann bhodach, a thuirt gur e dràibhear tagsaidh a bh’ ann. Cha robh mi cinnteach an e, ach cha robh duine ris an do choinnich mi fhathast coltach ri dràibhear tagsaidh agus bha mi den bheachd gum bithinn na bu shàbhailte còmhla ris-san, seach gu robh e cho sean, na bhithinn còmhla ris na cùis-eagail eile a bha mun cuairt! Bha an Lada aige a’ coimhead cho sean ris fhèin.

B’ e mo cheann-uidhe ostail le ainm uabhasach tarraingeach − “Godzillas.” Dh’fhaighnich mi mun phrìs agus thuirt am bodach gum bitheadh e mìle rouble − mu fhichead not. Bha an trafaig trang agus cha robh e a’ faighinn lorg air an àite. Thug e faisg air dà uair a thìde Godzillas a lorg. Thug mi dha beagan a bharrachd air mìle rouble. Sin nuair a thòisich am buaireadh. Dh’iarr e dà mhìle. Ach dh’aontaich sinn mìle. Cha robh càil a dhùil agam barrachd a thoirt dha. Thog e mo bhaga a-mach à deireadh an Lada agus dhiùlt e a thoirt dhomh gus an toirinn dha dà mhìle. Cha robh Beurla aigesan. Cha robh Ruisis agamsa. Cò againn a ghèilleadh an toiseach? Thilg mi ainmean mì-mhodhail air. Bu dìomhain dhomh. Thug mi dha dà mhìle rouble. Thug e dhomh mo bhaga. Chuala am boireannach anns an ostail pàirt den argamaid. Dh’fhaighnich i dhomh dè a phàigh mi airson an tagsaidh.

“Dà mhìle rouble”. Chrath i a ceann.

’S e àiteachan mìorbhaileach a th’ ann an ostailean. Tha iad a’ toirt dhut an cothrom coinneachadh ri measgachadh de dhaoine. Tha iad saor agus tha rudeigin an còmhnaidh a’ dol annta. Air an làimh eile, uaireannan chan eil e càilear gu bheil rudeigin an còmhnaidh a’ dol! Cuideachd, feumaidh tu feitheamh gu foighidneach gach trup a tha thu ag iarraidh dhan taigh-bheag agus dhan fhras.

Bha iad a’ leasachadh Godzillas, ga fhàgail mar rudeigin a chuireadh am muir air tìr. Thug mi sgrìob ghoirid mun sgìre timcheall mas deach mi a chadal. Bha mi ann an rùm còmhla ri còignear shrainnsear, a’ chiad bhlas air an t-saoghal a bhitheadh agam fad bliadhna. Chan fhada a sheasadh an t-airgead mas e agus gun coinnichinn tòrr coltach ris a’ mhèirleach ud. A dh’aindeoin a bhodaich ge-tà, bha mi na mo bhoil, mo thuras air tòiseachadh.

A Toirt Mo Chasan Leam by Maureen MacLeod is out now published by Acair priced £14.99.

You can also read an extract from Maureen’s novel Banais na Bliadhna, published by Sandstone Press, on Books from Scotland here.

For Radhika Swarup truth is central to how she writes. In this Q&A Radhika, a former investment banker and now author of Where the River Parts which tells the story of the tragedy that underpinned the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, muses upon her journey to becoming an author and emphasises the importance of history and family to her writing.

Radhika Swarup

Tell us about your debut novel, Where the River Parts?

Where the River Parts follows a Hindu Muslim couple caught up in the traumatic Partition of India and Pakistan. They are separated during the process, and don’t see each other for the next fifty years. It is only half a decade later, as both India and Pakistan are testing their nuclear weapons, that the two meet again in New York and face an impossible choice. Where the River Parts straddles half a century and three continents, and has been described as a timeless tale of love, loss and the barriers we build between us.

Tell us more about your journey into writing. When did you know you wanted to become a writer?

I always wrote as a child, but stopped when I went to university. My degree was in Economics, and after I graduated I began to work in investment banking, and for a while it seemed as if my days of writing – of indeed reading for pleasure – were at an end. And then at a private equity conference in Frankfurt, I found myself surrounded by industry veterans crowing over the latest Financial Times article to call them vultures. I realised I hated finance. It was my 26th birthday, and a moment I remember with absolute clarity. I left the celebrations of the conference and went to my hotel room to write, and was the happiest I had been in years.

What research, if any, did you do? What were your thoughts on the findings of your research?

As an Indian, and as someone who has lived in Pakistan, I was familiar with Partition. My family was impacted by the Partition too, and we made the move from Pakistan into India, so the whole tumultuous period is engraved on our psyche.

The sheer scale of the displacement, though, was unknown to me. 1 million people were murdered, and 16 million left homeless, largely in the 3 month period that followed Independence. I had to research these aspects of the past – the extent of the tragedy, the interactions between members of the Hindu, Muslim and Sikh communities in united India, the clothes worn during the period, how the flames of hatred were fanned – partly through books and other media, and partly through family accounts. I was both shocked and strangely un-surprised by what my research uncovered. Partition brought out both the best and worst in humanity, and we have seen the same emotional tapestry being woven far too often in recent times.

Do you have a personal family history tied to Partition or did most of the inspiration and background come from your research?

My family on my father’s side were affected by the Partition. They had to leave Lyallpur in West Punjab to make a new life in Delhi. Their experiences have largely seeped into the atmosphere I’ve tried to portray in Suhanpur, the fictional town my protagonists live in. I’ve had a wealth of details given to me about my family’s life in what became Pakistan, and I’ve tried to imbibe Where the River Parts with a sense of it.

Beyond telling me about their life in Pakistan, though, my family didn’t share any of the horrors they witnessed with me. Other ‘children’ in my extended family were similarly protected. It is only now as we have grown, and now that I have tried to delve deeper in my family’s involvement in the Partition, that stories have begun to come out. About the relative who risked life and limb to return to Pakistan to retrieve a family heirloom. About the young boy who travelled on a train to India – and miraculously survived – despite the Hindu symbol Om tattooed on his wrist. About my paternal grandparents, who were married shortly before the Partition, and travelled to Karachi, a city that fell the way of Pakistan, shortly before the worst of the violence was unleashed. About intimidation, about neighbours on both sides of the border turning against each other, about tragedies, about cowardice, about opportunism and about remarkable heroism.

Is it a difficult thing to bring a history so few of your readers will be familiar with so vividly into life? As a debut novelist, there must have been challenges…

I tried to focus on the fact that protagonists from that era and from that geography still had familiar concerns. A 17 year old girl was still consumed with her youth, her friendships and with love. She had no concept of a career back then, but she did recognise the need for education, and in that sense, she doesn’t feel so dissimilar to a young girl today. A 20 year old boy was still focussed on injustice, his career and the girl he loves. And though the setting is different for many readers today, I hope the common traits they share with the protagonists help make them feel real.

How do you see your role as a writer and what do you like most about it?

A writer tells the truth. That truth can take many forms – fantasy, irony, comedy or tragedy – and the truth itself can be contested, but to me the purpose of writing is to convey the world as it is or as it could be.

Have you ever created a character who you dislike but find yourself empathising with?

To a large extent I feel proprietorial towards my characters, and even when they behave in a way I wouldn’t personally condone, I find myself understanding how they have arrived at their choices.

If you could be transported instantly, anywhere in the world, where would you most like to spend your time writing? And why?

Rome. I spent a large portion of my childhood in the city, and there is something about the sun, the light, the unhurried way of life, and about the Roman relationship with art and beauty that never fails to inspire me.

What advice do you have for would be novelists?

We’ve all heard this before. Read and write, but it really is true. The more you read, the more you learn to perfect your own writing. And it is invaluable to get yourself a support group. Join a course, a writer’s group, write with friends. An online group, even. Anything that allows you to read other people’s writing and to get feedback on your own.

And what’s next for you? Are you working on something new?

I’m working on my next novel, which examines a woman’s response when the world she knows changes forever. It’s an internal exile, if you will, as compared to Where the River Parts’ epic journey. It’s in the early stages at the moment, but I’m really enjoying delving into her life.

Where the River Parts by Radhika Swarup is out now published by Sandstone Press priced £8.99. You can read an extract from the novel on Books from Scotland here.

Mongol [mong-gohl], noun, 1. a member of a pastoral people now living chiefly in Mongolia. 2. (offensive) a person affected with Down’s Syndrome.

In this powerful memoir, Uuganna Ramsay deftly addresses and challenges multiple prejudices. In this extract we are given insight into Uuganaa’s nomadic childhood when she lived in a one-room ger – or yurt – in the remote western reaches of Outer Mongolia.

Extract from Mongol

By Uuganaa Ramsay

Published by Saraband Books

Better than Lenin

Until my sister Zaya was born in 1984, I was an only child growing up in Uliastai, in the western reaches of Outer Mongolia. Both of my parents came from large families, with nine and eight brothers and sisters apiece, which meant that Zaya and I had seventeen aunts and uncles, not to mention their wives and husbands. Because I was a first grandchild for my paternal and maternal grandparents, all of those aunts and uncles spoilt me rotten.

Our traditional Mongolian house, known mostly in the West by its Russian name of ‘yurt’, was called a ger: portable, felt-covered, wooden-framed and circular. I later came to realise that while my parents moved around a fair bit in my childhood, the good thing about living in a ger is that wherever you go it’s still the same house, the same home. Beyond that our ger was special: not many were decorated as ours was. I loved waking up to the beautifully hand-painted support poles and above them the round toono, the single window at the top of the ger. Like the wooden poles, two columns and the toono frame were also hand-painted. There was something else, too: my paternal grandparents had seven boys and a girl, of whom my dad is the eldest; and grandfather told us that the beautiful big rug in the middle of our ger was bought by my grandparents when Dad was only 15.

Our home was also full of photos of me that had been enlarged in Russia, where my uncles and aunts had studied. This was during the socialist era of worshipping our Russian ‘brothers’ for helping us to rebuild a country and people that had for centuries struggled for independence from the Qing Dynasty of China. I dreamt of going abroad where you could get chewing gum, which was then a rare treat in rural Mongolia. My long ash-brown hair (fairer than usual for Mongolian children) meant that if any of my friends felt like teasing me they would call me ‘Russian’ or ‘a cat’ as an insult. Mongolians don’t like cats. It’s a superstition thing; they see dogs as honest and good friends to humans. But thanks to my uncles and aunts I was one of the trendiest children in town wherever I went, showing off my colourful Russian dresses and pretty ribbons.

Some of my happiest childhood hours were spent at an old desk, rescued from the school where my mum worked and now squeezed into our single-room home that already contained two metal beds, six beautifully decorated chests, a matching wardrobe, a yellow bookcase and a red kitchen cupboard arranged all around the wall. I felt very important doing my homework at that desk, with my schoolbooks and drawing implements. I even tried to make my own space by stitching a Russian poster of Lenin ‘Bypassing Capitalism’ to the wall hanging, beside the black German lamp that Father had brought back from Berlin in 1980. He was a vet, and had attended a professional development course in East Germany. I remember him bringing beautiful yellow leather boots for me and a television labelled ‘Wesna’ from Moscow, on his trip back. The television was a great attraction to my uncles and aunts and after meal times in the evenings our ger became something of a cinema.

Until the mid-80s we had only Russian programmes to watch – with my dad mostly interpreting for us – and I was so embarrassed at the sight of a man and woman kissing that I pretended to be reading or doing something else. Russian culture was much more open than ours. When Mongolian broadcasting reached into the rural areas, it was a great feeling to watch our people speaking their own language and playing our music. Those early programmes were taped and brought to our town by plane as it was impossible to broadcast to the whole country at the same time. Broadcasting via the Asiasat satellite was still to come in the 1990s. We watched the news and everything else three days later than Ulaanbaatar, the country’s capital. But our programmes were more restrained than the Russian ones, so I no longer had to hide my embarrassment.

My desk area was perfect for me to ignore what was going on behind me and get into whatever I was doing after my household chores. Reading became a passion, and my favourites were novels and short stories. My parents told me that I ‘lost my ears’ when I read. They had to come and physically close the book to get my attention. One night, I nearly burnt the ger down trying to finish a book. The lamp was too close to my dad’s radio and its glass front melted from the side. This led my parents to ban me from reading anything other than schoolbooks. I had to learn to switch off from the outside noise when concentrating on my studies. There were no other rooms where you could go. The ger has just one room, serving as bedroom, kitchen, living room, dining room, study room and just about any other room you would know in the West.

So it was useful to learn to concentrate on my studies when my parents were chatting to each other, my sister was toddling around, the TV was on and most of the time we had other relatives or friends dropping by. The ger has a stove right in the middle; as you enter it is facing towards the right side, and the chimney faces the opposite side, where the guests are normally seated. In some rare cases it is reversed in order to divert the evil spirits, which might happen if, for example, a family had been trying to have a baby without success.

In my carefully arranged office area I began to write poems and short stories. My first poems were titled ‘My Dad’s Work’ and ‘Teacher Lenin’. Even when I was very young my parents had great expectations for me. My mum was a teacher of Mongolian and Literature and our house was full of books. She used to read me stories whenever she could. Sometimes I would ask Dad for a story and he would start with: ‘Once upon a time there was a little bird looking for a nest. He decided to build a nest for himself and started carrying a piece of grass from far, far away.’ Then Father would stop. A few minutes later, I would ask, ‘How about now?’ He would say, ‘Still collecting more.’ Eventually, a few years later I was fed up with his usual response of ‘Still collecting more’, so I said, ‘Please finish the story when I’m older and driving a Volga in Leningrad.’ Of course, he was happy with that and probably relieved that a nagging child stopped asking for a story to which he did not yet know the ending himself!

Mongol by Uuganaa Ramsay is out now published by Saraband Books priced £8.99. You can read another excerpt from the book here and listen to Uuganaa’s ‘The Meaning of Mongol’ on BBC iPlayer here.

Uuganaa Ramsay presenting a recent Tedx Talk in 2016

In this month’s column David Robinson reviews Scotland-based author Jason Donald’s arresting new novel in which the eponymous Dalila leaves Kenya, and a personal history of brutal violence, to arrive in London. Yet Dalila soon discovers that London provides no escape from the many dangers she hoped she had left behind. Robinson praises Donald’s convincing treatment of this timely topic and argues that more novels must follow Dalila’s direction to further what he calls ‘fiction’s ‘real life footprint” to ensure that such important, yet oft-neglected, contemporary experiences are told in today’s publishing landscape.

Ten years ago, when The Scotsman ran Britain’s biggest short story competition, each year I used to pick what its theme should be. For the first one, I wanted to select a subject that was hardly ever covered in fiction, one that would guarantee an influx of freshly written and entirely original entries rather than tired old retreads dusted off from bottom-drawer oblivion.

I know, I thought. Let’s get everyone writing about Work.

Considering the fact that most of us work for a living, isn’t it odd so few writers write about it? Yet how many people do you know who would define themselves mainly in terms of their jobs? How many would move from one end of the country to the other – or even to another country altogether – for a better one? For how many people, is work – its gossip, politics, dreams – the most fulfilling part of their lives and its disappointments the source of their greatest regrets?

It’s only when you start thinking like this that you realise how little of real life fiction’s footprint actually covers. Of course, you will correctly point out, fiction depends on transformation while work relies on routine, which is probably why the world still awaits its first novel set in the office of a pensions actuary. And one reason we turn to fiction in the first place is precisely because we are creatures gifted with an imagination – Hogwarts, Xanadu, Borodino, the Culture – that the ordinary nine-to-five can’t match.

All the same, whenever I come across a novelist tackling an important subject I’ve never read anyone else attempting, and extending fiction’s footprint just that little bit further, I can’t help cheering them on. And among this month’s new Scottish releases, that’s precisely why I’m rooting for Jason Donald’s second novel.

Dalila charts the passage of its eponymous heroine, a 20-year-old Kenyan asylum-seeker, through the Home Office’s Kafkaesque bureaucracy, which sends her to Glasgow to await the results of her application. The novel is particularly well-researched: in the Noughties, when he was living in Ibrox, Donald taught English to asylum seekers for the best part of the decade. He has also done extensive voluntary work for charities working with refugees and those held in detention centres.

I’ve done none of that – indeed I’ve never even met an asylum seeker. But reading Dalila did what fiction is supposed to do: it turned a key in my mind and suddenly I was looking at a completely unfamiliar slice of life in a familiar city. I’ll give you an example. About half-way between Ibrox Stadium and the Glasgow Science Centre, there’s a spectacularly badly named building called Festival Court, where Dalila has to go to be assessed. It’s a real place, and used by asylum-seekers in real life, and now I’ve read the novel I can imagine, in a way I couldn’t before, what it must be like to go there, knowing that the person interviewing you there has the power to send you back to a place where your life could be at risk. That could happen right there and then. You might have turned up for that meeting at Festival Court, having picked up your children after school, fully immersed in everyday life in this new city, and they could be sent off to the detention centre with you, still in their school uniforms.

I’d never realised, in other words, that there was an office building in Glasgow that effectively was a border, just like the painted line you cross when you show your passport at the airport. I’d never thought of it like that – or to put it another way, I’d never read a novel that had made me feel empathy towards asylum seekers. Yet just as, in The Grapes of Wrath, the problems only really began when the Okies arrive in the supposed paradise of California, Dalila made me realise that it’s the same with asylum seekers arriving in Scotland. And this is, quite obviously, not a paradise at all but a cold place of purgatorial waiting, a limbo land where you can’t take any work, can’t understand the locals, have hardly any friends and even less money.

Mentioning Steinbeck’s classic brings me back to that business of fiction’s footprint. Thanks to Steinbeck, fiction opened up to our imaginations the lives of all of those who made the Grapes of Wrath journey west from the dustbowl states of Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas and Missouri to California (300-400,000 in the whole of the 1930s). And thanks to books like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, another American migration – the journey of up to 100,000 slaves fleeing slavery in the southern states to find freedom in the north – opened up minds even further in the century before. Indeed, it would be easy to argue that there’s never been a more influential novel in history.

Europe’s migrant crisis is, however, on an altogether bigger scale. The numbers of migrants pushing into Europe 1.2 million in 2015 alone – is vastly greater than the numbers of Okies heading west or slaves heading north combined. So where’s the great European migrant crisis novel?

Young adult fiction writers are streets ahead on this one. Michael Morpurgo’s Shadow and David Almond’s Jackdaw Summer are just two of those who have written about asylum seekers, but there are many more, and I’m glad of it: those Syrian children whose families have fled the civil war might find a greater degree of empathy in our classroom as a result. But apart from the partial exception of Chris Cleave’s 2008 novel The Other Hand, adult fiction seems to have given the subject a body swerve. Why?

“Maybe it’s just because we want comfortable narratives about a world we already know,” Jason Donald told me. “Certainly I did try to read novels about asylum seekers, not just to seek inspiration but to find out what the rest of the field was like. I struggled to find anything.”

He has, though, had the last laugh. Christopher Hampton, the Oscar-winning screenwriter behind such films as Dangerous Liaisons and Atonement, has already written a filmscript based on Donald’s novel. This is already Cape’s lead fiction title for January, comes with a back cover full of adoring quotes from Janice Galloway and Anne Donovan, and I don’t doubt that it will do well. Because when fiction extends its range beyond its usual subjects, when an empathetic novelist shows us what we’ve been ignoring all those years, we’re all the better for it. I said earlier on that I’ve never met an asylum seeker. I have now.

Dalila by Jason Donald is published by Jonathan Cape on 16th January, priced £16.99.

The Hairdresser of Harare

By Tendai Huchu

Published by Freight Books

In this informal interview the author of The Hairdresser of Harare reveals what inspires him, how living in Scotland provided a new perspective on Zimbabwe’s complex social problems, how he conceived the novel’s central character Vimbai, and his top tips for aspiring authors.

Listen to Tendai read an excerpt from The Hairdresser of Harare below.

The Hairdresser of Harare by Tendai Huchi is out now published by Freight Books priced £8.99.

A skilled and keen climber throughout his teenage years, at the age of just nineteen, Red Széll learned that he was going blind. His harnesses seemed to be packed away forever but after twenty years he began climbing again which led him to tackle the treacherous Orcadian sea stack The Old Man of Hoy. This inspiring extract shows Red’s long-standing love of climbing and details how the devastating diagnosis of Retinitis Pigmentosa led him to dangerous ‘night climbing’.

The Blind Man Of Hoy

By Red Széll

Published by Sandstone Press

According to my mother I began climbing to escape boredom and inertia at an early age, learning to scale the sides of my cot and mastering the downward traverse to my toy-box before I was a year old.

As I grew up I emulated Spiderman’s vertical ascents on every available play-frame, tree or building and watched John Noakes’ exploits with a mixture of awe and envy. Blue Peter also introduced me to the great mountaineering feats of the 1970’s and 80’s and I followed the expeditions goggle-eyed on the BBC. The death of Nick Estcourt on K2 had a greater impact on me than that of Elvis a few months earlier.

Chris Bonington had become a familiar figure from all his media work, but it was the simultaneous appearance of Joe Brown and The Old Man of Hoy on my TV screen in about 1984 that convinced me I could take my love of climbing to another level. Bonington was a larger-than-life gentleman-adventurer type but Brown came across as an ordinary bloke, a Manchester plumber. And The Old Man was a rock cathedral summoning the faithful that, in comparison to the mountaineering meccas of Anapurna and Everest, lay on my doorstep.

This form of climbing looked extremely accessible.

Rural Sussex is not renowned for its crags and peaks but the school’s Cadet Force promised a summer camp in The Brecons that included a couple of days rock climbing training with The Army; so I signed up and suffered a year’s square-bashing as my fee.

The course was so good that I stayed in the Cadets for another two years by the end of which both my climbing and marching were pretty sound, before escaping to the sixth form rock club with its twice-termly trips to Harrison’s Rocks in Kent. I was hooked.

At university I bypassed the Mountaineering Club, my recollection is that they were too Alpine for my taste and pocket, preferring the buttresses, slates and parapets of Cambridge’s roofline instead.

The company was good, the protection minimal if there at all. Perhaps it is as well that access to the window ledge necessary to complete The Senate House Leap (The K2 of Cambridge Night-Climbing, requiring the traverse of an 8ft wide void 70ft above the cobbles) was barred by the occupancy of a responsible adult in the room beyond.

My nights out on the tiles were numbered anyway. In September 1989, shortly before my 20th birthday, I was somewhat bluntly informed by a consultant ophthalmologist that I was suffering from Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) and “could expect to be effectively blind by the age of 30.”

RP is a degenerative eye condition that affects the photoreceptors at the back of the eye. First the rods, responsible in the main for night and peripheral vision die off, followed by the cones and their colour vision. If you’re lucky the bundle of cells that form the macular and are responsible for central vision hang around for a few years but they too are on borrowed time.

Back in 1989 I was still in the early stages. My field of vision had only decreased by about a quarter of the standard 95 degrees and I had yet to experience the joys of photopsia (the constant kaleidoscope of flashing lights that burst across my vision as my brain tries to fill in the gaps left by my increasingly dead retina).

Climbing, however, is all about trust. If I could no longer trust my own abilities how could I expect anyone else to want to climb with me? At the same time though, more than ever, I needed the release; I needed to feel in balance with myself.

I began to push my luck. Night-climbing in states of Dutch courage that make me cringe for my safety now (bear in mind it was a lack of night-vision that had got me referred to the consultant in the first place) to prove to myself that I could beat the condition.

My favourite ascent, that of the North East face of The Fitzwilliam Museum, topped out at a glorious glass cupola where I could enjoy a spliff before my descent. Maybe this is why I can remember so little of the English Literature I was meant to be reading at the time. Certainly being too wasted to be scared stiff saved me from serious injury on the couple of occasions I took nasty, unprotected, falls.

Red Széll will be presenting RNIB Radio’s ‘Read on’ programme from the 13th of January. With 154,000 listeners per week ‘Read On’ is broadcast on Fridays at 1pm and repeated on Sundays at 2pm and Mondays at 6pm on Freeview Channel 730, on-line and the programme is available as a podcast on iTunes.

The Blind Man Of Hoy by Red Széll is out now published by Sandstone Press priced £8.99.

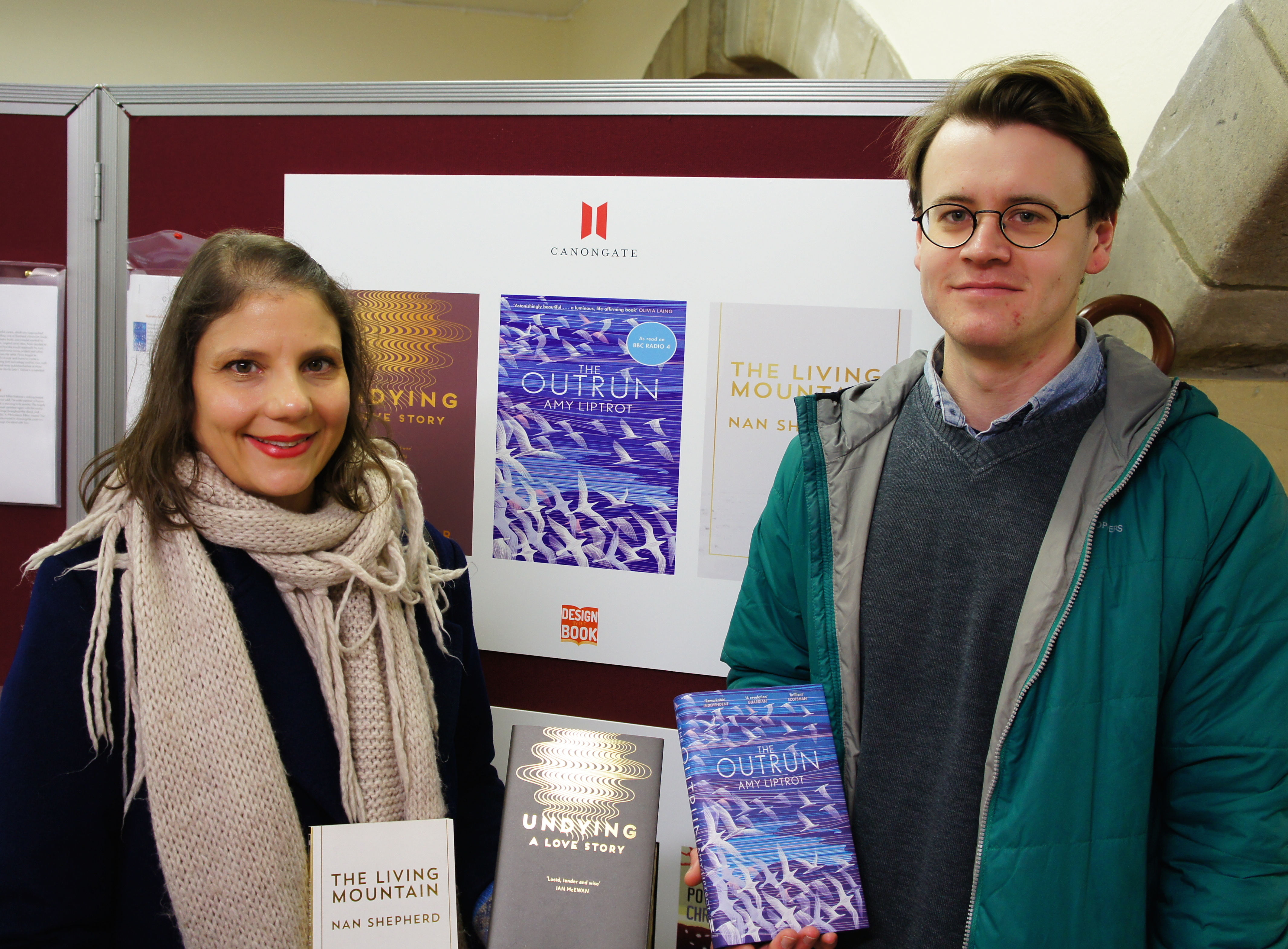

In today’s highly visual world, colour, font, and imaginative design all play their part in making books stand out on the shelves. For Book Week Scotland, the annual celebration of books and reading, Publishing Scotland showcased the best of contemporary design from publishers at Edinburgh Castle’s atmospheric Vaults. Featuring a diverse array of artwork, the ‘Design by the Book’ exhibition went behind the scenes of the creative process in the Year of Innovation, Architecture and Design.

Measuring tape at the ready while setting up the exhibition

Duncan Jones of ASLS (Association of Scottish Literary Studies) and artist/illustrator Ailsa Black

Rafi Romaya and Christopher Gale both from Canongate Books

Marc Cain from Pilring Press with author Craig A Smith and artist/illustrator Emily Dodds

Gillian Achurch and Alice Strang both from National Galleries of Scotland

Author Sara Sheridan with her novel published by Black & White

Kevin Robbins, designer, with Jethro Lennox from HarperCollins

Fiona MacLeod from Glasgow Museums Publishing with designer Fiona MacDonald

Designer Mark Mechan with Allan Cameron from Vagabond Voices

Leah McDowell from Floris Books with author Theresa Breslin

Designer Mark Mechan with his cover design for Waverley Books

Publishing Scotland’s Eleanor Logan poses with some of the featured books, authors, and publishers

Braving the cold outside the Castle Vaults at Edinburgh Castle

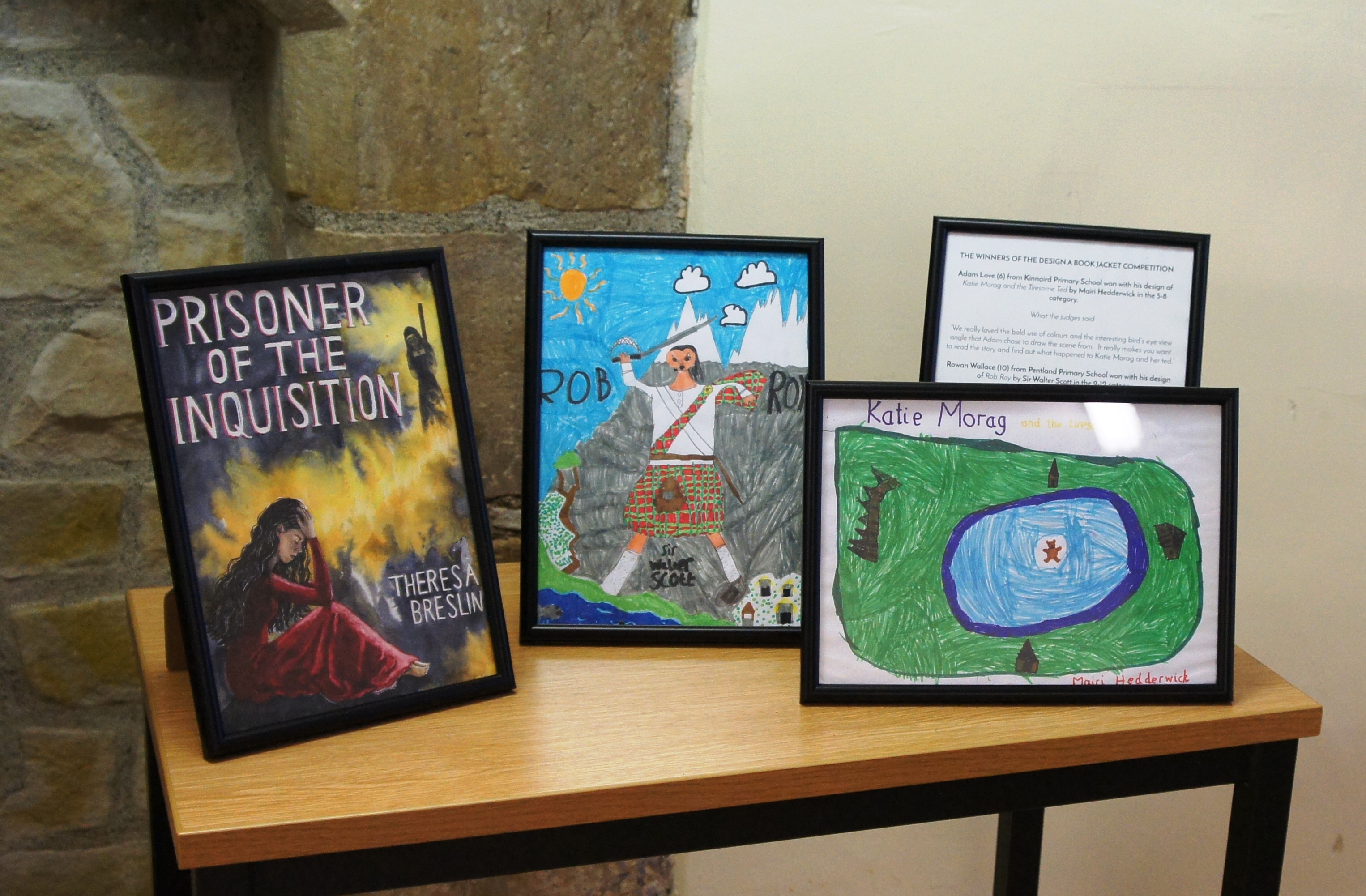

The exhibition also included the winning and shortlisted entries of the ‘Design a Book Jacket’ competition for children and young people, facilitated in partnership with the Scottish Library & Information Council (SLIC). The winners were Adam Love (5), Rowan Wallace (10) and Julia Speirs (17). You can see the winning entries, and find out more about the young artists below.

Competition judge Kate Leiper, the Edinburgh-based award-winning book illustrator, reveals why these three designs stood out from over 400 others:

- Adam Love from Kinnaird Primary School won with his design of Katie Morag and the Tiresome Ted by Mairi Hedderwick in the 5-8 category: ‘We really loved the bold use of colours and the interesting bird’s eye view angle that Adam chose to draw the scene from. It really makes you want to read the story and find out what happened to Katie Morag and her ted.’

- Rowan Wallace from Pentland Primary School won with his design of Rob Roy by Sir Walter Scott in the 9-12 category: ‘We were drawn to the composition of Rowan’s design and loved the portrayal of Rob Roy who looks very heroic in his skilfully drawn kilt. He has also been placed in a suitably dramatic background which is full of colour and interesting detail.’

- Julia Speirs from Bo’ness Academy won with her design of Prisoner of the Inquisition by Theresa Breslin in the 12-18 category: ‘We were all very impressed with Julia’s quality of drawing and painting which is very detailed and delicate. The figure in the foreground is particularly well observed in showing a character weighed down with emotion. Julia has also taken a lot of care over the lettering, ensuring that it can be read easily on what is quite a busy scene’.

Photo by Rob McDougall of Julia Speirs with Cabinet Secretary MSP Fiona Hyslop at Edinburgh Castle

If you’ve enjoyed this article you might like to see more brilliant cover designs from publishers in Scotland on the Design by the Book Pinterest board here. Design by the Book was exhibited at Edinburgh Castle from 21-27 November 2016. Betram Books and Bell & Bain were the exhibition sponsors; partners were Historic Environment Scotland, SLIC, Book Week Scotland and Creative Scotland. Publishing Scotland would like to thank everyone involved.

In this guest post by the founder of the unique Jolabokaflod Book Campaign, Christopher Norris proposes spreading the good news of Jolabokaflod far and wide to families this Christmas to remind everyone why books are so essential to our lives.

Origins of Jolabokaflod

Christopher Norris

The retail cycle each year in Iceland, from the launch of new books to the reading of these books at Christmas, is known as Jólabókaflóð, which translates roughly into English as ‘Christmas book flood’.

This tradition began during World War II once Iceland had gained its full independence from Denmark in 1944. Paper was one of the few commodities not rationed during the war, so Icelanders shared their love of books even more as other types of gifts were short supply. This increase in giving books as presents reinforced Iceland’s culture as a nation of bookaholics – for example, a study conducted by Bifröst University in 2013 found that half the country’s population read at least eight books a year.

Every year since 1944, the Icelandic book trade has published a catalogue – called Bókatíðindi (‘Book Bulletin’, in English) – that is sent to every household in the country in mid-November during the Reykjavik Book Fair. People use the catalogue to order books to give friends and family for Christmas.

During the festive season, gifts are opened on 24 December and, by tradition, everyone reads the books they have been given straight away, often while drinking hot chocolate or a Christmas ale cocktail called jólabland.

In October 2015, I was invited by BookMachine to write a regular blog posting for members of this international publishing community to read, having written a well-received piece about the future of publishing: ‘Publishing 2020: an Advent calendar of change‘. As I researched topics to write about, I read an detailed review in The Bookseller about the book trade in Iceland, ‘In depth: Iceland’s book market‘, and came across Jólabókaflóð for the first time.

As I was a pioneer of World Book Day in the UK, serving on the steering committee for the inaugural event in 1996-7, I realised that the Icelandic tradition of Jólabókaflóð offered a fabulous opportunity to promote book buying and reading within the same initiative, so the seeds of the Jolabokaflod Book Campaign were planted.

Urged on by the BookMachine executive, I launched Jolabokaflod Book Campaign at an RSA Bounce event in London for entrepreneurs in November 2015.

In December 2015, on a business trip to New York, I met with Hlynur Guðjónsson, Consul General and Trade Commissioner at the Consulate General of Iceland in New York, to share the vision of spreading the custom and practice of Jólabókaflóð to the UK and beyond. Mr Guðjónsson gave the Jolabokaflod Book Campaign his endorsement and facilitated contact with Icelandic organisations of potential mutual interest, including embassies and book trade bodies such as the Reykjavik UNESCO City of Literature and the Icelandic Literature Center, both players in annual ‘Christmas book flood’.

At Christmas 2015, the Jolabokaflod Book Campaign encouraged people all over the world to experience the joy of giving books as gifts and reading them over the festive period in a series of published articles and blog postings.

In my role as Head of Crowdfunding at CrowdPatch, I saw the opportunity to release people’s enthusiasm and creativity for running crowdfunding campaigns along Jolabokaflod principles – to buy books to give to others for active reading.

Between March and October 2016, I set up and ran the first Jolabokaflod Patch project at CrowdPatch – called The Icelanders Cometh – which built on the strong connection with Icelandic literature by seeking funds for UK libraries to spend on books published in English by Icelandic authors. The project successfully raised £2365.00, 103% of its target figure, which will soon by available for five participating library authorities to spend (including one in Scotland).

There is great potential for people to raise money via Jolabokaflod crowdfunding to spend on books for vulnerable and disadvantaged groups in local communities – for example: schools, unemployment groups, hospitals and prisons. This will be an evolving focus for the Jolabokaflod Book Campaign over the coming year.

Jolabokaflod UK at Christmas 2016

I have dual aims for Christmas 2016. In November this year, two concurrent digital media campaigns were launched: one to introduce the spirit of Jólabókaflóð to the UK and beyond, to encourage people everywhere to make the Icelandic tradition part of the way they celebrate Christmas; and the other to promote a UK version of the Book Bulletin online, to capture book recommendations to share with people seeking to buy Christmas gifts for their friends and families.

So, I am creating a buzz to encourage people to integrate Jolabokaflod into the way they celebrate Christmas and – via the Book Bulletin catalogue – to provide ideas for great books for people to buy to give to loved ones.

There are always moments in every household when there is a temptation to switch on the television or play a computer game. Jolabokaflod encourages people to make time for family reading over the festive season and reminds everyone that reading for pleasure is fun and therapeutic.

From the book trade perspective, Jolabokaflod creates a fabulous new opportunity to promote and sell books. A publisher, for example, only has to sell one book to be in profit after making a financial contribution to the Book Bulletin crowdfunding campaign, which is raising money for the Jolabokaflod 2017 programme. The Jolabokaflod Book Campaign publicises book recommendations in the catalogue via digital media, so we actively support publishers in their ambition to sell more books.

My overriding hope for this year’s Jolabokaflod campaign is to create market awareness and increased recognition of the tradition in time for a bigger campaign next year.

How you can help to spread the tradition of Jolabokaflod

Jolabokaflod is essentially a simple, viral concept – to encourage people to buy books as Christmas presents to give to friends and family for reading over the festive season. There are many ways in which you help to this Christmas tradition to spread: here are a few ideas:

- Tell friends and family about Jolabokaflod in person: word of mouth is still a potent way of sharing messages

- Include the org website URL in your email signatures

- Follow and ‘like’ Jolabokaflod on social media – Twitter: @Jolabokaflod; Facebook: /Jolabokaflod – and like and repost messages you would like to share with your networks

- Recommend your favourite books via the Book Bulletin crowdfunding campaign, and encourage other people to do so, too

- Think of an innovative crowdfunding campaign you would like to set up and run via the Jolabokaflod Patch at CrowdPatch in 2017, and tell other people about this opportunity as well

Scotland and Iceland are linked via their respective literary heritages. Indeed, these cultures are recognised worldwide: Edinburgh and Reykjavík are both UNESCO Cities of Literature.

Wouldn’t it be great to bind the connections between Scotland and Iceland further by spreading the good news of Jolabokaflod to families this Christmas? Let’s invite everyone in Scotland to make this wonderful tradition part of the way in which the festive season is celebrated. Let’s promote Jolabokaflod to remind everyone why books are so essential to our lives.

Christopher Norris is a media, publishing and social entrepreneur with over 25 years’ experience of joining the dots between crowdfunding, book publishing, digital media, television, music and film by being passionate about making things happen, publicising excellence, and helping others achieve their creative goals.

Chris is the Founder and Curator of the Jolabokaflod Book Campaign, a not-for-profit enterprise to introduce the Icelandic tradition of Jólabókaflóð to the UK and beyond. He is also Head of Crowdfunding at CrowdPatch, the crowdfunding platform for social entrepreneurs

He has managed many crowdfunding campaigns at CrowdPatch with a success rate of 100% – including Jolabokaflod Book Campaign projects The Icelanders Cometh and Book Bulletin, which is live until early February 2017.

In his senior executive role at CrowdPatch, Chris serves on the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Crowdfunding that meets regularly at the House of Commons under the chairmanship of Barry Sheerman MP.

Buy Buy Baby tells the story of two different women, Carol and Julia, and their lives in and around Glasgow. In this entertaining excerpt Julia steps into the murky world of online dating courtesy of the questionable Men2be agency.

Buy Buy Baby

By Helen MacKinven

Published by Cranachan Books

The Men2be agency promised that only “discerning professional men” were on their books. The naff name had initially put me off from registering, but I was keen to test the authenticity of the agency’s claim that the men were all highly successful professionals. The steep registration fee of £1500 did make me think twice about signing up. But it seemed a fair price to pay to filter out any undesirables.

Men2be’s secondary sifting process was a massive questionnaire for prospective members – it was going to take fucking ages to fill in. The online form wanted to know everything from how much I earned, the school I had gone to, the designer labels I favoured, the property I owned, to the car I drove. The dating agency’s strict criteria even ruled out any woman who was over a dress size twelve. Thank Christ I’d kept up my gym membership. I had to be a bit creative with a few facts and figures, or I’d never have passed the entry requirements. It wasn’t a problem; a good journalist knows how to massage the truth.

My best friend, Kirsty, had even emailed me a dictionary of terms for women’s personal ads. But the joke was only funny if I didn’t have to cross reference my own profile with the comedy version. It was obvious that if I wrote one thing, it meant something entirely different.

30ish = 38

Adventurous nature = slept with everyone

Athletic build = no tits

Voluptuous = fat bird

Average looking = ugly as a monkey’s arse

Gorgeous = pathological liar

Glamorous = high maintenance

Emotionally secure = on medication

Soulful= cries a lot

Contagious smile = does a lot of pills

Outgoing = loud and embarrassing

Fun = annoying

Free spirit = junkie

New age = body hair in all the wrong places

Looking for soul mate = stalker

Passionate = up for it

Sensuous = dirty

Open-minded = desperate

The humorous element of the list wasn’t completely lost on me, but it made me overanalyse every single word I chose to describe myself. No one wants to end up a cyber-spinster.

Did I want to sound intelligent or would being too clever put men off?

Did I want to sound fun or should I sound more serious?

Did I want to use a professional photo or would it look as if I was trying too hard?

Reading the variations, anyone would think that there were more sides to me than a Rubik’s cube. Updating my profile was the perfect displacement activity.

SCREEN NAME JOURNOJULES

LOCATION GLASGOW – CITY OF STYLE

AGE THIRTYSOMETHING

SEX JOURNOJULES – WHAT D’YA THINK?

EMPLOYMENT FREELANCE BUSINESS JOURNALIST

BODY TYPE JESSICA RABBIT

LAST BOOK READ SCOTTISH BUSINESS DIRECTORY

FAVOURITE AUTHOR VIRGINIA WOOLF

BEST/WORST LIE YOU’VE EVER TOLD

“IT’S NOT YOU, IT’S ME”

WHAT ARE YOU MOST SCARED OF?

BEING ON A PLANE, ABOUT TO CRASH… AND THE BLOODY BAR IS CLOSED

TOP THREE THINGS THAT ANNOY YOU

- REFORMED SMOKERS

- PEOPLE WHO EAT WITH THEIR MOUTHS OPEN

- RUDE SHOP ASSISTANTS

FIVE ITEMS YOU COULDN’T LIVE WITHOUT

- MY LIVER

- SEQUINS

- MY BLACKBERRY

- LA PAVONI ESPRESSO MACHINE

- MY NIECE HOLLY

The most difficult question to answer on all of the sites had to be, “WHAT ARE YOU LOOKING FOR IN A RELATIONSHIP?”

This was the BIGGY, the question that required the most thoughtful answer.

Over the last few months, I’d tried out a few:

“A guy that makes my nipples peak just by looking at them.”

“The total package with all the trimmings.”

“A best friend, lover, partner.”

“The other half of me.”

I toyed with answers for hours. Too slutty? Too tongue-in-cheek? Too corny? Choosing a response was a nightmare. Eventually I decided on an honest answer, minus a key detail.

“The last love of my life.”

I’d alluded to seeking a long-term partner (without any mention of the ‘B’ word) and hoped it wasn’t too scary a prospect for most men. It was a no-brainer NOT to advertise the whole truth. No man would ever reply to the most honest answer, the bluntest version being, “Desperately seeking a man to settle down with and start a family”.

Buy Buy Baby by Helen MacKinven is out now published by Cranachan Publishing priced £9.99

This Q&A with author Michelle Sloan reveals how she is continually inspired by the stories and bravery of previous generations. As she explains, her new book The Revenge of Tirpitz, allowed her to delve deep into researching wartime Norway which saw her encounter everything from reindeer husbandry to the indigenous Sami people of the North.

The Revenge of Tirpitz

By Michelle Sloan

Published by Cranachan Publishing

Interview with Michelle Sloan, author of The Revenge of Tirpitz

What was the inspiration for your book The Revenge of Tirpitz?

A few years ago, I watched a Channel 4 documentary called ‘The Dambusters’ Great Escape’, all about the final, successful bombing of the Nazi battleship Tirpitz. I found it utterly compelling. My dad had always had an interest in Tirpitz too so it was a familiar subject to me. But what really caught my imagination was the revelation that a German radar operator may have been working against his own people by withholding key information about the approaching British Lancasters thus creating time for them to successfully bomb Tirpitz. I began to wonder about weaving a story about this German. I wondered if I could fictionalise his escape on the ‘Shetland Bus’ – the fishing boats that sailed between Norway and Shetland.

The story is written with a dual timeline of modern day and 1944 during WWII. What is it that draws you to that specific time period?

It’s actually the little things that fascinate me – the lives of everyday people and how they coped and lived through the fear and restrictions imposed upon them during wartime. And then there’s the extraordinary bravery and commitment at that time to the cause. I suppose I relate it to myself – could I put myself in the position of the men and women who put their lives on the line?

How did you approach the research?

The research was the real joy of the process and was very varied! I’m lucky in that my sister-in-law is Norwegian and has an encyclopaedic knowledge not just of the history of her country during WW2 but of everything from reindeer husbandry to the Sami people of Northern Norway. I peppered her with questions! I read lots of fabulous books: ‘Target Tirpitz’ by Patrick Bishop and ‘The Shetland Bus’ by David Howarth. But I also had to research many other things for example life on board a fishing boat! So I watched lots of episodes of ‘Deadliest Catch’!

Who is your favourite character in the book?

Funnily enough, my favourite character only appears in one chapter! Inga, who is from the Mountain Sami and is a reindeer herder. I watched this fabulous clip on a BBC website about the reindeer in Northern Norway that swim as a herd across a freezing fiord. And this amazing young woman was in charge of the whole operation. She inspired me to create Inga – she’s very young but is confident, strong and intelligent. I would love to write a spin-off story about her.

When you’re not writing what would we find you doing?

Reading! I am always engrossed in a book! Even when I walk the dog or I’m cleaning the house, I’m listening to an audio book! At the moment, I’m engrossed in PD James’ ‘The Mistletoe Murder and other stories’ which is a seasonal collection of short stories. Apart from books, my other great love is theatre. I love all kinds of theatre from contemporary performance to musicals to children’s theatre.

What was your favourite book from your childhood?

Absolutely, without question, my favourite was and still is ‘The Box of Delights’ by John Masefield. There is something about the combination of an old-fashioned Christmas and ‘dark magic’ that is utterly transporting. I now get to enjoy the story with my own children.

The Revenge of Tirpitz by Michelle Sloan is out now published by Cranachan Publishing priced £7.99.

Award-winning author Matt Haig’s Christmas stories, accompanied by stunning illustrations by Chris Mould, appeal to adults and children alike. A Boy Called Christmas presents the true tale of Father Christmas, proving that nothing is impossible, while The Girl Who Saved Christmas asks whether, if magic has a beginning, can it also have an end?

This excerpt is read by Stephen Fry.

This excerpt is read by Carey Mulligan.

A Boy Called Christmas and The Girl Who Saved Christmas, both by Matt Haig and illustrated by Chris Mould, are out now published by Canongate Books priced £9.99 each or £20 for the boxed special edition set of both books.

Journey through the twelve days of Yuletide – told in Scots – and meet a cast of skaters skooshin, lassies birlin, sheep a-shooglin and the all-important five gowden rings in this video which also showcases the book’s stunning illustrations.

The 12 Days O Yule

By Susan Rennie

Published by Floris Books

The 12 Days O Yule by Susan Rennie, illustrated by Matthew Land, is out now published by Floris Books priced £5.99.

With examples spanning from Anglo-Saxon kings to today’s celebrities, Hello, My Name Is… expertly and entertainingly charts the history and importance of personal names-given names, surnames, name titles, and professional names. Here Burdess delves into how naming works worldwide and finds that there is not one standard practice but a diverse myriad of traditions.

Hello, My Name Is: The Remarkable History of Personal Names

By Neil Burdess

Published by Sandstone Press

Bart Simpson, Bart Homerson and Bart bin Homer: Names and naming around the world

In modern societies, we expect a child to be given a name almost immediately after birth, but what about more traditional societies? Richard Alford’s study of traditional societies still in existence in the mid-twentieth century found that naming a baby soon after birth was the most common practice, but it certainly wasn’t the only one. In societies where infant mortality was high, adults often didn’t name babies until it was clear that they would live through infancy. For example, children were named only when they reached a particular life-stage, such as when they could crawl, when they were weaned, or when their first tooth appeared. The thinking was that the family might grieve less if an unnamed child died. Other societies waited until a child’s physique or personality was clear so that the name could reflect this characteristic. Finally, some societies put off naming babies for supernatural reasons, believing that harmful spirits were less likely to notice an unnamed child.

Even in modern societies, the idea of announcing a child’s name immediately after birth is not a universal practice. For example, in Iceland a baby’s name is not announced until the official naming ceremony. As parents legally have up to six months to register a baby’s name, there can be a long period before the name becomes known. Before the naming ceremony, only the parents know the name—even grandparents and siblings are kept in the dark. Until then, the baby is called drengur or Gunnarsson if he’s a boy, and stúlka or Gunnarsdóttir if she’s a girl. If the parents don’t want to divulge the sex, they can call the baby elskan, an affectionate term meaning sweetheart.