Extract from St Kilda: The Silent Islands

By Alex Boyd

Published by Luath Press

Extract from ‘Introduction’

Having carefully lowered my camera cases into the boat, a task sometimes made impossible due to the rising and falling of the sea, we then set off, my eyes fixed on that most iconic of sights, the ruins of village bay beyond. It was not however the empty streets of Hirta which fascinated me, but something more modern, something absent from the countless tourist images of the islands, and much less sympathetic to the surroundings; a Cold War military base.

Instead of a structure hewn from local stone, the concrete and steel of a crumbling military installation are what first greet the eye of the visitor. Foremost among these is the unsightly but essential power station which keeps the modern St Kildans supplied with electricity, the one building which for obvious reasons rarely appears in the vast visual documentation of the islands.

Coming ashore, the extent of the military base becomes clearer, with the long low buildings of the 1960s accommodation blocks, sergeants mess, and the rather Victorian sounding ‘ablution block’ sitting side by side with the more well known cottages and cleits. It is in many ways an uneasy balance, but one which has allowed St Kilda to thrive, with the efforts of National Trust work parties supported by that of QinetiQ, the company who run the military base on behalf of the Ministry of Defence.

Turning my back on the base I looked out over the harbour, towards Dun, observing the strange spectacle of a bay full of yachts, tour boats and other pleasure craft. Hirta of course is a regular stopping point for a variety of cruise ships, and it is not unusual to find Village Bay thronged with tourists, wandering with guide books in hand around the ruins of the cottages, stopping to take self portraits, viewing the home and sometime prison of Lady Grange, and finishing the day by visiting the National Trust gift shop for a tea-towel or commemorative mug before boarding launches back to their ships.

Deciding to go somewhere quieter, I sought to leave Village Bay behind entirely, with the intention of exploring the lesser known areas of the island such as Gleann Mor and the Amazon’s House, and to walk the ridge leading between Mullach Mor and Mullach Sgar, both hills crowned with radar stations which track live rocket firing from South Uist.

It was from the vantage point of the hills above Hirta that the island began to show a different side, with the long grassy valley of Gleann Mor offering a sense of solitude largely absent from the busy working environment of Village Bay. It was also here I began to get a sense of the knife-edge existence that those who had lived on this island must have endured, with the exposed landscapes, sheer cliff drops down to the Atlantic below, and fragile rocky promontories adding to the sense of the dramatic. It would be to this place that I would often return on my visits to the island, slowly watching mist and cloud drifting in the valley before me, concealing and then revealing the vista below.

It would be a year until I would next return to the islands, these images staying with me, the thoughts and feelings I had experienced slowly coming together in a way that made me want to respond to the environment, to document what I had seen and had felt.

I had resolved to respond in a way which did not obscure the true St Kilda. I would document the military presence as well as the natural beauty of the islands, and the ruins of Village Bay, to show a more balanced view, something which in truth is still rarely seen. I would do this all with a battered medium format camera which had once belonged to the English landscape photographer Fay Godwin, whose work I would often return to as guidance and as a point of departure.

The result is this book, a collection of images made over the course of several years and several journeys. They tell of days when the islands were bathed in a singular Hebridean light, or more likely completely obscured by clouds and mist. They are a journey around the archipelago, and are intended as a visual poem of the place rather than as a guide. For now they are the silent islands; quietly waiting, alone out in the North Atlantic, a place of austere beauty.

St Kilda: The Silent Islands by Alex Boyd is out now published by Luath Press priced £20.

This month our columnist David Robinson looks at what makes the Ullapool Book Festival special including its unique mix of cherry blossom, egalitarianism and longstanding Canadian connections.

Around now, the cherry and plum trees are starting to blossom on Market Street, and for those of us who love Ullapool, this can only mean one thing. It’s book festival time.

Some years – when a hot late spring hazes into summer and the sun planes Loch Broom into Mediterranean laziness, the Village Hall can be almost hidden by blossom: you could drive past down Quay Street and not know that anything was happening.

Even in a normal Scottish spring, that would be a big mistake. Because although I haven’t yet visited every book festival in Scotland, the one that takes place in Ullapool Village Hall must be hard to beat. If you want to see literary Scotland at its egalitarian best (no green room, no signing queues, every event £8, and everyone up for the Friday night ceilidh), it’s a great place to start.

There may be other, bigger gatherings of Scottish writers at other, bigger book festivals, but Ullapool’s begins with the simple aim of getting together the best Scottish writers the organisers — led, as they have been since the start, by festival chair Joan Michael — can find. This year that objective has once again been well and truly met in a programme that includes Denise Mina, Bernard MacLaverty, Jane Harris and Douglas Dunn.

But Ullapool does a lot more than just celebrate Scotland’s own literary culture. It’s open to the world too, and often it manages to do both things at once. On Saturday 12 May, for example, there’s an event with Gaelic and Catalan writers with simultaneous translation into English through individual headsets. Which other book festival have you ever heard doing that? Me neither.

Then there’s the Canada connection. It started a decade ago, when the great Alistair MacLeod visited the festival, then in its third year. Really, though, the link was first forged in 1773 when the flat-bottomed ship Hector sailed out of Loch Broom to Nova Scotia and the Highland emigrant trail there began. (The MacLeods themselves followed not too long after, settling in Cape Breton — the subject of so much of Alistair’s own fiction — in 1806).

Because the Ullapool book festival has been so assiduous about keeping up that connection by inviting a Canadian author, that audience in the Village Hall on Market Street may well be the best-read in Canadian literature in Britain. And when it comes writing from Newfoundland, they could all probably go on Mastermind.

Why? Because they’ve seen the best. Even before the independence referendum, for example, they’d heard Wayne Johnson read from The Colony of Unrequited Dreams – about Joey Smallwood, a politician not unlike Alex Salmond except that he campaigned against Newfoundland independence and for a union with its larger neighbour. They’d heard Johnson talk about his family memoir, Baltimore’s Mansion, and how his father had hoped that one day above the island’s capital, St John’s, they’d see the Pink, White and Green proudly flying — pink for the rose of England, white for the St Andrew’s Cross, green for Ireland — as the flag of an independent country. That dream died in the 1948 referendum (it was close: just 7,000 votes), but Johnson still has the flag tattooed on his upper arm as a symbol of what might have been.

With both Johnson’s books as a spine of historical knowledge, even those of us who have never been to Newfoundland could half-imagine ourselves into the island. In The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, Smallwood, the fisherman’s union leader, assiduously worked his way round even the smallest outports — coastal hamlets that were all but impossible to reach overland. In 2015, Johnson’s fellow Newfoundlander Michael Crummey, reading from his novel Sweetland showed us those places in the near-present, just as isolated as ever but, because of the collapse of cod fishing, economically withering away, with their inhabitants queuing up for resettlement. This, too, was a story with strong Scottish resonances, and those who held out against resettlement did so for reasons that we can also understand — because, for all the hardship of their daily lives, they were still in thrall to the land’s harsh beauty.

They seem at home by Loch Broom, these visiting Newfoundlanders and Cape Bretoners, and maybe it’s no surprise. Apart from the extent of uncleared forest and the presence of indigenous peoples (and yes, we’ve had a former chief of the Potlotek First Nation on stage at the Village Hall), there are few great differences between Auld and Nova Scotias. Our minds find it easy to snake off into their land, their stories to fly back into our imaginations. In 2016, for example, Lisa Moore read from her novel February, about the 1982 Ocean Ranger disaster off the Newfoundland coast in which an oil rig was lost. It’s not too hard to see this as the great Piper Alpha novel we’ve never yet had — one which loops round the decades as mourning finally sinks into ordinary family life and the possibility of love begins again.

Last year, another Newfoundland novelist, Michael Winter came to the Village Hall to talk about his book Into the Blizzard, his first non-fiction book, about the destruction of the all-volunteer Newfoundland Regiment on 1 July 6, 1916, on the first day of the Battle of the Somme (of its 780 members, only 68 were able to report for duty the following morning). His book gets its title because one watching officer noted that when the men came under machine-gun fire, they instinctively tucked their chins into their advancing shoulder just as, back home, they would have advanced into a snowstorm. And if there was ever proof about the interlinking of their island story and ours, consider this: after being the only non-Scots ever to guard Edinburgh Castle, the Newfoundlanders left Scotland to fight only because so many Royal Scots were killed in the Gretna Green train disaster of 1915.

I have been privileged to chair all of these authors on their visits to Ullapool, yet I always will recall something the first of them told me. Alexander MacLeod spends his summers in Cape Breton, and his father’s short stories and solitary novel are all rooted there, but when he came over in 2012 he pointed out that such places have an altogether disproportionate influence on Canadian literature. That, he said, is why he made a deliberate point of including stories from the Canadian rustbelt in his own book Light Lifting (whose opening story “Miracle Mile” is one of the best I have ever read in a debut collection).

“We’re the most urbanised country in the West, but you’d never know it to read Canadian literature,” he told me. “You’d never realise that 70 per cent of the population lives in just five cities. But this country is just so huge that the landscape exerts this amazing pressure on all writers.

“It’s the same with the weather. If you took plots that involve extreme weather out of Canadian literature, that would decimate it. Yet it’s real enough: as dad always used to say, this is a country in which, for four months of the year, if you have to spend a night outside, you will die. That’s not like Miami or Greece. Other things will happen, but you will not die of exposure.”

David Robinson will be interviewing Canadian writer Ann-Marie MacDonald at the Ullapool Book Festival at 10.15am on Sunday 13 May.

Chapter 3 – The Time Machine

It’s not very often that you get the chance to travel back in time.

Through the doors of the aircraft hangar, waiting on the grass beside an apron of runway, was a 1942 DH82a de Havilland Tiger Moth – an open cockpit tandem biplane made of steel tubing, thin plywood and stretched fabric. This was going to be my time machine.

I walked out from the hangar and across the runway with my pilot, William Mackaness. Together, we were aiming to recreate a pioneering flight made from this same Perthshire aerodrome in the summer of 1939. Back then the pilot was a man called Geoffrey Alington, who operated a company called Air Touring. And his passenger was Osbert Guy Stanhope Crawford – now dubbed the ‘father of aerial archaeology’. Crawford’s flight was about travelling back in time too.

The air was almost perfectly still – the aerodrome’s windsock was hanging listlessly from its pole. Beyond, to the north, you could see a wide expanse of farmland and the solid outline of the Cairngorms. The late summer sun was dropping, catching the distant mountains half in light and half in shadow. Set against the flatness of the land they looked somehow artificial, like the backdrop to a theatre set. This sense of unreality was appropriate. On top of my olive-green flight-suit I was wearing a leather and fur-lined Irvin jacket that had once belonged to a Second World War pilot.

‘Right now you’ll feel really hot’, William said. ‘But once you’re in the air you’ll be grateful for it’.

William had already begun his starting sequence. ‘There’s something almost magical about it’ he said. ‘It’s a checklist you learn off by heart – a ritual that puts you in a different mindset, that marks the start of your journey.’ First came the ‘walk round’ – feeling the tension in the flying wires, looking at the fuselage for any signs of damage, making sure the wheels were at the right pressure and were free rolling, inspecting the fuel tank above the cockpit – capable of holding 19 imperial gallons; ‘enough for about two and a half hours of flying’ as William explained. Next he checked the oil in the Tiger Moth’s 130hp Gipsy Major Engine. ‘It’s nicknamed the “Dripsy”’, he said ‘because it’s notorious for leaking oil’. A detail that, I confess, I did not want to hear immediately before take-off.

William compared this process to a kind of dance – I could see what he meant. Even climbing into the aircraft had a sequence of set steps: right foot here, left foot there, twist your body this way, grip just that part of the wing – not below or above – left leg over, then lower yourself down to your seat. Why? Because, very simply, if you step in the wrong place there’s a good chance you might put your foot straight through something important…

As I fastened the seatbelt straps over my shoulders and around my waist, William began to, as he put it, ‘tickle’ the engine – first allowing the fuel to flow down to the intake manifold, then drawing it into the engine itself by turning the large single propeller on the nose. The propeller was a startling piece of craftsmanship. And very clearly of another time – a single piece of wood, carved exquisitely into a sort of curved figure-of-eight and lacquered to a smooth liquid shine, with gold-metal trim for the edges that sliced through the air. It brought to mind the fluid, streamlined hull of some vintage speedboat.

‘Magnetos off, fuel is on, throttle closed, four blades’, William recited. ‘Four blades’ referred to turning the propeller four times, to ensure that each cylinder takes in the fuel air mixture. Then it was ‘magnetos on’ – creating the electric spark that ignites the engine. With a guttural roar, the propeller in front of me spun to a blur. We sat for a few minutes, letting the engine and the oil warm up, before nimbly taxiing over the grass and on to the runway.

The take-off was remarkably quick. William ramped the engine up to 1600rpm with the breaks still on. Then he gently released the breaks and fed in the throttle, which he controlled with his feet. ‘You need soft shoes for it’ he told me, ‘you have to feel the aircraft, and the power, right in the soles of your feet’. Within seconds we were racing over the tarmac. I pulled the goggles down from my canvas flying helmet as the rush of air tore at my eyes. Another few seconds later, we were up. And we were going back in time.

Scotland from the Sky by James Crawford is published on 3 May by Historic Environment Scotland priced £25. All images used here are taken from the book. The book accompanies the BBC documentary series of the same name which will be broadcast in May.

Award-winning author Gill Lewis makes her debut to the Barrington Stoke list with a stunning tale of the wild that hides in us all. Run Wild is a thought-provoking and touching story that celebrates the unique bond between children and nature.

Extract from Run Wild

by Gill Lewis

Published by Barrington Stoke

The wolf is still at the old gasworks.

Somehow I thought he might have gone away or that maybe we had made him up in our heads. But he’s still there, lying on the pile of sacks. He must have got up at some point, because the bread crusts Connor threw for him have gone. I look over at Jakub. His eyes are wide, wide open.

“It’s a wolf,” Jakub whispers as if he can’t believe it. “A real wolf.”

The wolf watches us too. He lifts up his nose and sniffs the air. Then he turns away and licks his lips.

“I told you,” says Asha. “He wants to eat us.”

Jakub shakes his head. “No,” he says. “He’s scared. If he looks away and licks his lips, it means he sees you as the top wolf.”

“Are you sure?” I ask.

Jakub nods. “It’s wolf language.”

Jakub opens his book for me to see, and I look at pictures of wolves, some with tails and heads tucked low and others standing with their tails right up. Some of the wolves are snarling at each other and showing their teeth. “Ugh, I wouldn’t want to get into a fight with a wolf,” I say.

Jakub closes the book. “Wolves don’t want to fight with each other. It’s not worth the risk. That’s why they use body language to sort out who’s top wolf. They don’t eat people either. That’s just in fairy tales.”

“If you know so much about wolves,” says Asha, “then what’s this one doing here?”

Jakub looks back at the wolf and shrugs. “I don’t know. It shouldn’t be here. The last wolf in Britain was killed in 1680.”

“Well, this one’s hungry,” I say. I take a can of dog food from my bag and pull the ring to open it. I don’t have a bowl, so I rip a spare page from my pad of paper and tip the meaty chunks out. I wrap it up and throw the whole thing to the wolf.

He scrabbles to his feet and limps towards the food.

“He’s hurt his foot,” says Asha.

The wolf doesn’t put his front right paw on the ground. He sniffs at the food, then rips the paper with his teeth. He eats the meat in big greedy gulps. When he’s finished, he turns and limps out of the warehouse. We follow him at a distance and watch him make his way slowly down to the river, where he laps at the water. His ears twitch forward and back, listening. Then we watch as he goes back into the warehouse and settles into the pile of sacks. He spins around and around before he flumps down with his head on his paws and turns to watch us again.

“We can’t do any more for him at the moment,” I say. “Best give him some space.”

Asha nods. “C’mon, let’s try out that ramp.”

I grab my board and turn to Connor and Jakub. “Don’t go near the wolf or you can’t come back.”

“Can we explore?” says Connor.

I nod. “Don’t go near the river, OK?”

I watch them walk out into the wasteland. Then I turn back around to see Asha already at the top of the ramp ready to fly down. She pushes off and picks up speed, twisting between bricks and rubble.

“That was so cool,” she says, a massive grin on her face. “C’mon. I’ll race you.”

We build obstacles and make mini ramps from old boards balanced on bricks, and we don’t even notice the time pass until Connor and Jakub come running in. At first I think something’s wrong. Connor is doubled over. He’s shaking and there are tears running down his face. It’s only when I get close I see he’s laughing.

Jakub is holding something in his cupped hands. “We found a farting beetle!” he shouts.

Connor explodes into laughter again.

Asha rolls her eyes. “What’ve you got?”

Connor tries to speak between gulping air. “When Jakub tried to pick it up, it actually farted and I’m not even joking. It stinks!”

Jakub opens his hands and we see a small beetle with bright-green metallic wings and a red body. It moves so quickly that Jakub has to let it scuttle from hand to hand.

“Don’t let it go,” says Connor. He puts his hand into his school bag and pulls out the notebook where he keeps all his drawings and notes about dinosaurs. He starts to draw the beetle. “We have to find out what it is,” he says.

I watch Connor draw the beetle next to his picture of a dinosaur feeding in a swamp.

Asha pulls out her phone. “It’s got to have a name.” She speaks out loud as she taps into Google on her phone. “Green farting beetle in London.”

“You’ll never find it,” I say.

Her eyebrows shoot up in surprise. “It is here. It’s actually here. It’s called a Streaked bombardier beetle. It says it squirts acid and makes a farting sound. It’s meant to be really, really rare.”

“We found loads of others,” says Connor. “D’you want to see?”

We leave our skateboards and follow Jakub and Connor outside to a pile of rubble. Jakub pulls up a stone, and about ten little green beetles scuttle away to find shelter under other rocks. Then he and Connor turn over other stones to look for more bugs.

Asha sits down in the shade of a bush. “It’s so hot,” she says. She slips off her shoes and socks, digs her toes into the dirt and stares at them. “When did we last do this?”

I look across at her. “Do what?” I ask.

“Go barefoot,” she says.

“I don’t know,” I say. “Years ago maybe. It was probably in your garden.”

Asha grins. “Do it. Do it now.”

I kick off my shoes and pull off my socks. I press my feet against the ground and feel the warmth through my skin.

It feels good to touch the earth.

Asha sighs. “Just think, there was a day when we ran barefoot for the last time together and we didn’t even know.”

“Well, it’s not today,” I say. I stand up and grin. “Race you!”

Asha laughs and runs after me. The stones spike against my feet, but I don’t stop until Asha catches hold of me and pulls me down. We lie in the long grass and catch our breath.

It feels like we’re five years old again.

Asha picks the white puffball of a dandelion and holds it in front of me. “Blow and make a wish,” she says.

I smile. Last time we did this, I think I wished I could ride on a unicorn. Wishes were easy back then. Now what do I wish for? To be more popular? To be clever? For Dad to find a job? To be a happy family like we were before? I don’t know. I blow and watch the dandelion seeds drift up and away.

Asha closes her eyes. “I could sleep here all day.”

I lie next to her and stare up at the sky. It’s a pale hazy blue, criss-crossed by aeroplane vapour trails. It’s quiet too. The drone of traffic and hum of city life seem so far, far away.

I feel my body sink against the small stones and soft grass. I dig my fingers deep into the earth, and it’s as if everything is draining out of me. I lie still and listen to the lap of small waves from a riverboat and the pop of seed heads bursting in the heat.

Everything is quiet.

Everything is still.

For the first time in a long while I feel I can breathe.

I watch a heron flap above us, its wing beats slow and lazy. It’s a huge bird, filling up the sky. It flies down to the river, its wings outstretched and its legs ready to land. It vanishes somewhere into the reeds in the old dock. As we lie still, the wasteland comes to life around us. A flock of small birds flurry down to a wide puddle. Butterflies dance in shafts of sunlight, and small bees buzz from flower to flower. Three cormorants fly low, heading up the river. I prop myself up on my elbows and just watch. The more I look, the more I see.

It’s not a wasteland.

It’s a lost world.

A hidden wilderness.

Connor must be thinking the same, because he folds his arms around his knees and says, “It’s like the Land That Time Forgot.”

I smile because it’s one of Connor’s favourite old movies, where explorers find a hidden world full of dinosaurs.

“We’ll have to give it a name,” says Asha. “It belongs to us now.”

“It belongs to the wolf,” says Jakub. “We’ll call it Wolf Land.”

Run Wild by Gill Lewis is out now published by Barrington Stoke and priced £6.99

The first children’s story I ever wrote was inspired by a trip to Staffa. This magical island with its basalt columns and a luminous blue-green cave is home to a colony of puffins. If your timing is right (between April and July) you can stride across the grassy top of Staffa and get quite close to the puffins, who seem surprisingly relaxed about human contact. Perhaps this is because they’re standing on the edge of a precipitous cliff!

The magical island of Staffa

Puffins are charming little birds, also known as Clowns of the Sea. I didn’t know this at the time, but clearly their colourful beaks and big orange feet gave me the same impression. My first puffin story features a misfit bird called Lewis who, unlike his brother Harris, hates eating fish and is afraid of heights. He longs to be a circus clown, and as Harris points out, his clumsy gait and comical face make Lewis perfect for the job.

A puffin or Clown of the Sea

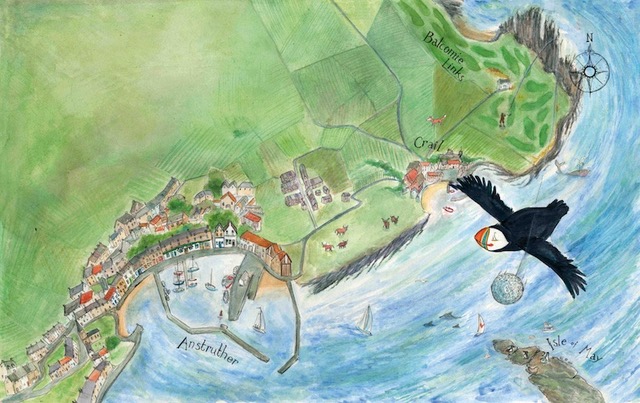

Lewis Clowns Around was published in 2011 by Floris Books. The realistic illustrations of the Firth of Forth, rocky cliffs and the Meadows in Edinburgh were beautifully done by Gabby Grant. Two years later she illustrated the sequel, Harris the Hero, a story about the brother who has been left behind. Harris flies over a coastal vista of Anstruther and Crail, helps rescue a baby seal and ends up happily paired with a puffin called Isla on the Isle of May.

The final image of Harris and Isla shows a fluffy little puffling between them, so naturally the next book would focus on their baby. By this time Gabby was busy with her own offspring, so the third puffin story, Skye the Puffling, was illustrated by Jon Mitchell. In each case, a great deal of research into the habitat and behaviour of the Atlantic puffin in Scotland is what gives these books their authenticity.

Harris and Golf Ball

My most recent book for Floris features another irresistible Scottish native, the red squirrel. In Rowan the Red Squirrel we have a young brother and sister, Rowan and Hazel, who venture out on their first exploration of the forest on their own. “Remember what Mum said – watch out for the fox!” calls Rowan as his sister hops out of sight. The forest holds all sorts of surprises for the pair, including scary encounters with a hedgehog, a woodpecker, a fox and an owl. Jon Mitchell has captured all these woodland creatures with great charm, and I’m inspired to get out into the Scottish countryside to see red squirrels in the wild. Maybe I’ll get some ideas for a story about Hazel…

About the Author

Lynne Rickards was born in Canada and now lives in Scotland with her husband and two children. She grew up reading Dr Seuss books and as a result she loves writing in rhyme. She is the author of the Puffin Adventures Picture Kelpies: Lewis Clowns Around, Harris the Hero, Skye the Puffling. Skye the Puffling was recently adapted into an abridged board book as part of the Wee Kelpies series – Skye the Puffling: A Wee Puffin Board Book. Her latest picture book about family of red squirrels, Rowan the Red Squirrel, is out now.

Lynne Rickards was born in Canada and now lives in Scotland with her husband and two children. She grew up reading Dr Seuss books and as a result she loves writing in rhyme. She is the author of the Puffin Adventures Picture Kelpies: Lewis Clowns Around, Harris the Hero, Skye the Puffling. Skye the Puffling was recently adapted into an abridged board book as part of the Wee Kelpies series – Skye the Puffling: A Wee Puffin Board Book. Her latest picture book about family of red squirrels, Rowan the Red Squirrel, is out now.

As far as I know, Elaine Thomson’s Jem Flockhart is the only 1840s apothecary detective in crime fiction. But that is the least important thing about her. Here’s the most:

“I had never worn stays, or petticoats. I had never sat in silence while men talked, had never modified my words or behaviour so as to guard against showing any man up as a fool or to preserve his self-worth. I walked the streets without fear of having my virtue threatened, I went wherever I wished, and I might smoke or spit as I pleased.”

Spitting apart, in other words, she is a modern everywoman. Except she’s not, because the first two books in the series have also shown quite convincingly how completely she is immersed in her own world of 1840s medicine. Two years ago, in Beloved Poison, Thomson showed her at work in London’s crumbling St Saviour’s hospital, which was about to be demolished to make way for a railway line. Last year’s Dark Asylum had Jem investigating a particularly gruesome murder at Angel Meadow insane asylum, where her father was a patient. In both, the period detail is present and awesomely correct, just as it is in the latest book in the series, The Blood, which is set on a seamen’s floating hospital, the Golden Fleece. (It is typical of Thomson’s microscopic attention to detail that this is only ever known as “The Blood” as Cockney rhyming slang reduces the ship’s name to “The Blood and Fleas”.)

The settings might change, but Jem is able to move between them easily first of all because she is an apothecary and secondly because she is, as far as everyone else is concerned, a man. After her male twin died at birth along with her mother, her father passed off Jemima as his son Jeremiah and raised her as a boy. Disguised as a man, she remains an anomaly: a woman in the then all-male world of medicine.

The Victorians were not, of course, known for their ready acceptance of gender fluidity, and every day of her life a real-life Jemima would presumably have feared being exposed as a woman and so would not put herself in any situation (going to a brothel with male colleagues, for example, or having any dealings with the law) where this might be a risk. A real-life Jemima would, you can’t help thinking, make just about the worst kind of Victorian investigator imaginable.

Thomson, however, stands by her woman. Shrewdly, she gives Jem a port-wine birthmark over her eyes. No-one is going to look too closely at her: she is, in her own words, “born for disguise”.

Why does Thomson go so far in particularising her protagonist? She could, of course, claim that the real-life example of Victorian military surgeon James Miranda Barry (who was revealed to have been a woman after he died in 1865) showed that such levels of lifelong concealment were indeed possible. Still the question has to be asked: isn’t Jem too much of a problematic problem-solver for her own good?

But this, in turn, throws up an even bigger question: what do we read historical fiction for? When we follow Jem on board the floating hospital, investigating a trail of sudden deaths, what kind of authorial voice do we want in our heads? Is it one that takes us by the hand and shows us the streets of London as they were when brothels were the city’s biggest business, and medical science was in its infancy and which shines a spotlight on Victorian attitudes that are anathema to our own? Or do we prefer a story that takes all that for granted and is told without a 21st-century spotlight operator in sight?

When I first met Thomson, she was still writing as Elaine di Rollo (her former husband’s name). I was impressed by the verve with which her first two novels, The Peachgrowers’ Almanac (2008) and Bleakly Hall (2011) swung between light comedy and the horrors of history, and surprised that her job – lecturer in marketing at Napier – was only tangentially linked to history.

Yet history clearly fascinates her, and she always seems to have been good at explaining it. “At my PhD exam, they said mine was one of the only theses they’d ever read that was actually a bit of a page-turner,” she told me. Its subject was the Edinburgh Women’s Hospital, and some of the things she came across in her researches – such as the use of sexual surgery to correct “odd” behaviour among women (which might amount to little more than not being deferential enough towards men) – have subsequently reappeared in her fiction. Women doctors battling against the male establishment, patients struggling against poverty and domestic violence: these are also themes that emerge in her Jem Flockhart crime novels but which she first encountered while trying to imagine the lives distilled into neat copperplate writing in the archives beneath Edinburgh City Chambers.

You could, therefore, argue that the feminist slant in Thomson’s Jem Flockhart novels is a necessary corrective to the image of Victorian Britain the Victorians left behind themselves. “The corpses of men find their way into the river by accident,” Jem’s father tells her. “Women’s arrive there by design.” Just so: and the silence behind that is surely worth looking at.

Similarly with sex. In Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming Pool Library, there is a scene in which his promiscuous protagonist William Beckwith is leafing through the diaries of the octogenarian peer who has asked him to write his biography. “I’m always forgetting,” he notes, “how sexy the past must have been.” Exactly: and again, that’s something else historians can never quite get to grips with and about which the archives are usually silent.

Fortunately, historical fiction doesn’t have to be equally dumb. And that’s why even though a real-life Jem Flockhart mightn’t have been have been such an effective mid-19th century crime-buster, a fictional one will do very nicely indeed.

The Blood by ES Thomson is published this month by Constable, price £14.99.

Native and Roman on the Northern Frontier presents the definitive report of a programme of excavation and survey at two sites south of Eskdalemuir, in the valley of the River White Esk, Dumfriesshire, which have wide-ranging implications for the study of the Iron Age and Roman frontiers. Over two years a small-scale intervention at the Castle O’er hillfort and the total excavation of a unique enclosure at Over Rig were carried out, the results of which are brought together and documented in detail for the first time in this volume.

Native and Roman on the Northern Frontier

By Roger Mercer

Published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

In the isolation of Upper Eskdale in Dumfriesshire archaeological remains dating from the Neolithic to the medieval period have survived in relatively good condition. A sequence of surveys and studies has shown an active Neolithic ceremonial focus, with great standing stone delineated settings and a kilometre-long bank barrow, Bronze Age cairns and cists, and an Iron Age hillfort known as Castle O’er, from which the area takes its name.

The hillfort lies at the heart of a complex pattern of linear earthworks that appears to be designed for the containment and control of animals. Associated with this complex was a further semi-circular, multi-embanked site built on the verge of the immediate cliff-like descent to the River White Esk which could be allotted no clear function or parallel type. This enclosure was known by the local name Over Rig.

Fearful that Over Rig was in danger of erosion by the river, it was chosen for excavation by Historic Scotland and excavated by a team from the University of Edinburgh. The team decided to investigate the hillfort at the same time in an attempt to tie together all of the Iron Age components and better understand the ancient landscape of the period.

An appraisal of the sequence of development at Castle O’er hillfort revealed that the site’s occupation reaches back to at least the middle of the first millennium bc, when a densely nucleated settlement was probably set within a high, defensive wooden palisade containing a number of great 12-metre-diameter roundhouses aligned along a levelled central roadway.

Occupation continued until about 200 bc, although the palisade was replaced at some point by a massive bank and ditch. At that date the fort itself may have fallen out of use as the landscape was being opened up by massive tree-clearance. Small farmsteads – terraced into the hillside and simply defended – appeared at relatively even intervals along the valley bottoms of the Esk and its tributaries.

Evidence gained from fossil pollens suggests that at this time the haughs of the rivers may have produced barley crops, and maybe protected woodland, while the hill-land behind was given over to sheep and cattle, thereby establishing a relatively prosperous farming landscape.

From early in the first century ad it seems likely that the construction of the outer complex of linear earthworks was added to earthwork annexes already built onto the old hillfort. Such a complex could have served to enclose herds of cattle and possibly horses – both of which we know were husbanded in Iron Age societies in Scotland, perhaps as tribute to rulers.

This facility would take on new relevance as by about 70 ad, some 30 years after their appearance in Britain, Roman forces had reached the Solway-Tyne line, which for a time became an effective frontier with a sizeable garrison. By the early 80s Agricola had embarked on his extraordinary adventure 300km to the north and must have felt secure in undertaking such long-range penetration.

By the 120s AD Hadrian’s Wall was under construction and Roman writers tell us some basic details of the ration allowances for their soldiers. We also now have a good idea of the number of units and troops stationed on the Wall and its associated forts. It is therefore a fairly straightforward calculation to determine the demand the Roman army made on the local economy. For the western part of the Wall, some 3,500 cattle would have been required per annum and probably as many as 800 ponies for cavalry remounts.

Agricola’s sense of security indicates a peaceful population around his lines of communication and a reliable supply of provisions, strongly suggesting a relatively peaceful take-over and the agreement of protocols and relations between Roman forces and at least the proximate ‘Scottish’ natives.

During the period of Roman presence the Over Rig enclosure was built in a dell beside the Esk. Excavation suggests that this unique site has a ceremonial function which is likely to have taken advantage of the site’s extraordinary acoustic qualities. In effect it was an amphitheatre, unknown elsewhere in Iron Age Britain and possibly influenced by Roman presence or drawn from Irish parallels.

The old hillfort was finally reoccupied, probably after the decrease of Roman influence in the area, its interior surrounded by a wall which was at least partly laced with timber. This fort was attacked at least twice and on one occasion, probably in the fifth or sixth century ad, the south-west gate was burned. At this time there was a minor decline in the availability of grassland for grazing, however upland grazing for sheep and cattle continued, through the supremacy of the monastic regime at Melrose who controlled the Eskdale estate, until hill farming was replaced by recent afforestation.

The excavations at Castle O’er and Over Rig have thus created and clarified the use of the upper Esk valley over a period of 5,000 years.

Native and Roman on the Northern Frontier: Excavations and Survey in a Later Prehistoric Landscape in Upper Eskdale, Dumfriesshire by Roger Mercer is available now, published by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (RRP £30). The book can be ordered online via the Society’s website.

Aimed at all concerned about the environment, this book presents a radical vision of the future of farming and community life, based on hidden insights from the life and spirit of the soil and on the author’s experiences of growing up in the small, agricultural community of Clatt in North-East Scotland. The author, Bruce Ball, a soils specialist has a research and consultancy career spanning more than 35 years. His regular contact with soil in the field and with farmers has led to a deep understanding of the critical importance of soil to our future survival.

Extract from The Landscape Below: Soil, soul and agriculture

By Bruce C Ball

Published by Wild Goose Publishing

INTRODUCTION

Man – despite his artistic pretensions, his sophistication and his many accomplishments – owes his existence to a 15cm layer of topsoil and the fact that it rains.

Anon.

I have appreciated the beauty of the natural world all my life. Growing up in a rural environment, the way I saw the world was shaped by the hills and rivers and the cycles of flowers, trees and animals. However, it wasn’t until middle age that I recognised the hidden beauty, in people, voices, eyes, gestures, poetry. That we often obscure beauty beneath ugliness and the materialism of the modern world is something I have come to see as a coping strategy for our loss of connection to the unseen value of all around us. The challenges society faces today suggest an addiction that has led to shortages of resources like oil, food and water and to reliance on things we have come to see as essential, while we ignore the ele- ments of life that have real value. The inequalities evident between rich and poor can load relationships with guilt and resentment, causing us to overlook the fact that we are all – in essence – the same.

I grew up with shortages because my folks didn’t have much money and we lived in a house without a reliable water supply. I came with economy built in. Our house was isolated but we had some land, a few hens, cows next door and plenty of wildlife, so what I lacked in toys and company I made up for by spending time outside learning the language of the hens, the animals, the birds, the trees, the vegetables, the stars and the soil.

Recently, I have begun to get impatient with our society which uses too much of everything, including other people, and which seems to be so angry and unhappy. Our destructive way of living, which burns up our last reserves of oil instead of conserving them for the next generation and which throws away so many things, is plain stupid. Sucking so much water out of the ground and fighting each other is plain stupid, as is our continued degradation of the environment.

I became a soil scientist mainly to learn how crops grew and to discover how to get them to grow better. We rely on the soil to feed us, despite our high-tech society, and we use crops and cultivation techniques that have changed little over the years. Only about 11% of the earth’s surface is covered by soil. Yet I soon realised that, even when we think we’re caring for it, we often treat that soil like dirt. We chuck fertiliser or water at it, churn it up and squash it back together with bigger and bigger machines. Our soils are losing their quality, becoming exhausted, so that over one third of the areas of productive soils are degraded. The soil is literally and figuratively the foundation of the environment, albeit hidden most of the time. Moreover, our soils are actually disappearing. As you read this, soils are being lost worldwide at an average rate of 300 tons per minute. If this continues, our remaining topsoil might not survive much beyond fifty years.

Shortages of soil, fertiliser and water will make it more and more difficult to feed our increasing population, leading to the very real prospect of food scarcity. Even if we’re not greatly concerned about global warming and peak oil, we can’t do without food. Nor can we deny that it is happening as some do with global warming. The evidence is clear in the lost soil, in problems with excessive nitrogen fertiliser use, in disappearing freshwater resources, destroyed forests, extinct animal species and desertification. There is no room for ‘abused land’ sceptics. We have already seen food riots and protests as a result of high prices. We need to learn the lesson from previous civilisations like that of the Maya. We tend to associate them with magnificent temples rising from the jungle. But they lost most of their soil due to erosion under their intensive agriculture. Those who destroy their soils ultimately destroy themselves.

I’ve spent time in my career developing simple methods to observe soil and to learn from it. When I handle the soil, it says good things to me. It speaks of its willingness to suck up water, to take in fertiliser, to become warm and to feed me. But like everything it has its breaking point, although it also responds to kindness. There is a parallel between caring for the soil and caring for others. I believe that achievement of this caring involves a search for beauty, not as an abstract concept but as a recognition of value.

My search began back in the community where I grew up. The people there loved the soil and conserved the environment instinctively. Most had successfully assimilated modern ways, yet had kept a traditional approach in their relationship with the land and with each other.

As a child, I recognised beauty in the yellow and brown colours of the local soil. As an adult, I discovered the strange purple soils derived from lava-like pumice stone in the nearby village of Gartly. The differences in colour alone remind us of the hidden complexity in the earth we walk on. Soil was described by Hildegard of Bingen four hundred years ago as ‘afire with the light of God’. This light comes from below as a crop germinates and emerges – she calls it ‘the greening power of the soil’. But the action of this light for growth depends upon the health of the soil and, because of its hidden nature, when its quality diminishes, we may not notice until it is too late.

In a similar way, our mental and spiritual health is being eroded from the foundations of our communities and our wider society. Globally we are facing an economic recession. In the northern hemi- sphere we are also facing a social recession. Despite the accumulation of material wealth, which we believed would bring us security, there is growing violence, pressure on the environment and widespread social inequality which makes us feel increasingly unhappy and isolated.

My career as a soil scientist began as a search for ways to improve yields for economic growth. My work with church groups began as a means of re-creating community. Both have brought unexpected results. Through recognising the beauty of the soil and the bonds between people, I have a greater appreciation of both and have found that the original aims of economy and community can be achieved in more holistic ways, by reconnection with the land and tuning in to the urge of the spiritual. We need to get back to our roots in the soil and delve within us to access the stored knowledge of past generations. There are close links between how the soil works, and how we manage it, and how we cope with others and manage our lives. This was well illustrated in the community of Clatt where I grew up. The people of the soil – those who not only work the land but also feel for it – were those who fostered com- munity developments. There was a tangible link between caring for the soil and caring for people.

Good soil management is not easy and our quick-fix approaches often lead to long-term damage. We could possibly feed ourselves without environmental damage if we all behaved rationally. But we have never behaved rationally before, so it’s unlikely that we will now. We claim to be ecological in fighting pollution and resource depletion. Yet this is often with the objective of preserving the health and affluence of people in developed countries – ‘shallow ecology’ in other words. In contrast, deep ecology1 sees the world as a net- work of phenomena that are all fundamentally linked and interdependent. This approach values all people, animals, plants and minerals equally. To move towards this deep ecological approach I think we need some help from the spiritual. We need to become aware of the sacredness of our environment, to listen and learn and become conscious of our connection to the spiritual within all things, so that we treat everything with reverence. In this book I look to the inner space both of soil and of humanity. I show the urgent importance of soil life for the future of humankind. The management of soils and farming can integrate with the spiritual and the social to point us towards the creation of sustainable communities based on beauty, justice and transformation. In this way we will be able to satisfy our needs and desires without robbing future generations.

To maintain my connection with the real world, I wrote this book on trains, boats, planes and, with some difficulty, on buses. This brought me into some interesting conversations with comments like:

‘You might change soil but you won’t change people.’

‘Ah you’re one of those who think all men are your brothers, then?’

‘You need to stop those immigrants from ripping us off and taking our jobs.’

‘Do you really believe in global warming?’

‘Why should we work when others can’t be bothered to get out and find a job?’

‘The economy has to grow for us to survive.’

‘We have always managed to adapt to problems in the past.’ ‘OK, so what are you, personally, doing about it?’

The result is a book about the hidden life of the soil and about the hidden forces that drive you and me. Developing an awareness of hidden problems and opportunities, and acting on them by searching for beauty, offers some pointers for improving our lives. Beauty ultimately comes from our inner landscape and often appears when we are waiting on the spiritual. The searching itself brings awareness of our every action, our environment and our resources and has a natural outcome in a desire for the good of others.

Note:

1 The concept of deep ecology was attributed originally to Naess 1973 and an example of its development is given in Capra 1997.

The Landscape Below: Soil, soul and agriculture by Bruce C Ball with a foreword by Alastair McIntosh, is now published by Wild Goose Publications priced £9.99.

The teeming seas and lengthy, fragmented coastline of Scotland are home to hundreds of species and colonies of seabirds and shorebirds. Shorebirds in Action conveys beautifully the author’s fascination with this group of birds.

Extract from Shorebirds in Action: An Introduction to Waders and their Behaviour

by Richard Chandler

Published by Whittles Publishing

What is the particular appeal of shorebirds? This book attempts to answer that question. Take a few random reasons as part of the answer. Shorebirds have evolved to occupy a surprising range of habitats worldwide, from the Arctic, through the tropics, to the Antarctic. They occur coastally, inland, on wetlands, in deserts, on open grassland and in woodland and forest. Many of these are wild places that appeal to those of us who have even a mild sense of adventure. Included amongst the shorebirds are the most extraordinary migrants of any animal species, which regularly fly for days at a time, covering thousands of kilometres. Many species have developed what are, even in these days of electronic sophistication, extraordinary sensing devices to find food below ground. Every spring they enliven the lengthening days with their dramatic in-flight displays and with their wonderful calls – even if the calls have to sometimes be interpreted as a stream of expletives! They have a surprising range of plumages, some species having the same appearance all their lives, others completely change their appearance every few months, matched by a surprisingly complex range of breeding strategies. And the list goes on.

My fascination with shorebirds started with an academic research expedition to high Arctic Spitsbergen in the early 1970s where I was involved in geotechnical engineering, not avian biology! At that time, it was not possible to fly there and a whole week beckoned on the ‘fast’ mail boat from Bergen, sailing north up the Norwegian coast, across the Barents Sea, past Bear Island, to the Svalbard archipelago – and I needed something to occupy my time. I had treated myself to a pair of binoculars a few months earlier, so the obvious solution was bird watching! My list of birds seen during the expedition was quite short, particularly in Spitsbergen itself, but it included a few shorebird species: breeding Grey Phalaropes; a single, off-route Red Knot (it was red, in full breeding plumage); and Purple Sandpipers, which confused me as they had darkish legs, despite the book I had with me implying that yellow legs were an important field mark. I later discovered that the field guide omitted to mention that their legs got darker in the breeding season!

A few months later, now with a real interest in shorebirds, a visit to the Isle of Sheppey in Kent, UK, again found me puzzling over shorebird identity – this time different species were involved, and they all looked confusingly similar. So similar in fact that I was not only confused, but even challenged, to put a name to them.

At about the same time I discovered the journal British Birds, which had recently published an article on bird photography that showed how much could be learnt from high quality photographic images. I was hooked, both by the shorebirds themselves and now on photographing them. This book is one result.

The intention here is to describe and illustrate aspects of shorebird behaviour. Although this is deliberately not a shorebird identification guide, one criterion used for selecting the photographs is to show as many different species as possible. As a result, about 180 shorebird species are illustrated – around 80% of the world’s total of 226 species – hopefully allowing this book also to be a useful identification reference.

A few images of other bird species are also included to show similar – or contrasting – behaviour to that of shorebirds. The book is meant, in the context of its relatively compact size, to be read either as an introductory text on shorebird behaviour, or enjoyed as a series of photographs, showing that behaviour – but preferably both, accompanied by the captions that explain what is being illustrated. The reader who wishes for more detail on shorebird identification, plumages and ageing, as opposed to behaviour, can refer to other texts.

Most of the aspects of a shorebird’s life and behaviour are described here: plumages and moult, feeding, physiology and comfort behaviour, breeding, migration and flocking. It is well beyond the scope of a relatively small book to deal with all these topics on a species-by-species basis, and consequently the more detailed coverage is restricted to a relatively few species that are reasonably representative of the world’s shorebirds. Examples are provided from Europe, Asia, Australasia, and both North and South America in an attempt to provide a survey that is as wide ranging as possible. The reader who is interested in taking the subject further is directed to the references at the end of this Introduction.

Shorebirds in Action: An Introduction to Waders and their Behaviour by Richard Chandler is out now published by Whittles Publishing.

What if time is layered, like a stack of pancakes? And what if trees, interconnected by a complex mycelial network, exemplify the most perfect type of freedom? The backdrop to Pauls Bankovskis’ 18 is a pivotal moment in Latvian history – the year is 1918 and Latvians are fighting for their independence – however, the novel’s scope is much broader. Our narrator is a deserter who traverses the country (and possibly time itself) largely by foot, narrowly avoiding all types of danger in a history now lost in myth and oblivion.

Throughout the chaos depicted in the novel one thing stands out as a constant source of insight and calm: the forest, and particularly its trees. As the story progresses a fascinating and beautiful theory surfaces that connects humanity, nature, space and time. In the following essay, Bankovskis discusses the influence of the forest on his life and writing.

Written in Latvian by Pauls Bankovskis

Translated by Ieva Lešinska

Trees Speak

The most powerful image in Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1975 film Mirror, in my opinion, is not Mother, played by the wonderful Margarita Terekhova, but Mother Nature – more specifically, the forest. It’s those scenes in which the screen is filled with twigs or branches, with the wind blowing past, over and through them. At these moments, Friedrich Engels’ saying about seeing the forest for the trees, endlessly bandied about yet uttered in a completely different context,* suddenly acquires a direct and literal sense. May I be forgiven by natural scientists for my wilful use of zoomorphic or even anthropomorphic comparisons, but it really looks like the moving branches do not “act” or “behave” like extensions of autonomous, free-standing biological organisms: rather, they appear as one complex whole. It’s not unlike the countless YouTube videos featuring clouds of birds which, in a mysterious consensus and coordination, create complex moving figures, or the schools of tiny fish which exhibit similar skills in documentaries on deep-sea life.

I’ve often observed this phenomenon first hand as well. Sometimes I sit on the veranda of our country house at a small, rickety table, and outside the window, half-covered by a vine, I can see the edge of the forest. By the fence there I can watch deer as they come out and graze; I’ve seen a fox going about its business and once, paying no heed to any of this, a badger trundled out for a little walk. Animals come and go, some distant noise or our movement in the house makes them prick their ears and in an instant they retreat into the wings of the forest. Only the set design seems to stay the same: aspens with their perpetually quivering leaves, two birches on the dry hill overgrown with bilberries, the monstrously entangled black roots of the spruce downed by a storm several years ago and the crooked pine to the right of it, and in the foreground a small birch grove.

Unseen by the human eye, the core population of this grove has managed to overcome the insignificance of undergrowth and fill out the lanky thinness of adolescence and early youth, and now stands tall as a serious brigade, albeit a little apart from the rest of the forest. As befits adults, they’re all dressed in the splendour of white bark now, yet nothing has changed in their behaviour or even character. As soon as the birches perceive a stronger gust of wind with the tips of their leaves, they’re poised to begin a coordinated choreographic performance that includes an elaborate prologue or warm-up, a gusty development of the theme and then a tumultuous culmination. It all ends with a retreat, a movement akin to ebbing, when a wave that has somersaulted and broken against the shore returns to the sea.

Just as the undulation of the sea, the dance of the birches seems to express both hope and melancholy. I would like to believe that over the years I’ve learnt the unique repertoire of movements that set our birch collective’s performance apart from those of other groves, copses and stands, but I’m afraid I haven’t the slightest hope of interpreting and understanding the message of this collaboration between the wind and the trees. Confronted with it I feel like a numskull, ignorant of sign language and watching an interpreter signing away on TV without realising that it’s possible to turn on the sound. Or perhaps a more apt comparison would be with the attempts of earthlings to communicate with extraterrestrials, as in Ted Chiang’s Story of Your Life, on which the film Arrival is based. Although the film differs considerably from the novella, the idea that our language has an impact on how we perceive the world is crucial in both versions.

The birches and other trees rustled by the wind remind me of visitors who’ve arrived from a great distance. And I’m not just trying to be poetic. Ten or eleven thousand years separate us from the time when the territory of Latvia was almost entirely covered with forests, with predecessors of plants still found there today: that distance is hard to manage even in my mind. Time travel is difficult whichever way you go: it’s no easier going back four thousand years – to a time when our forests became more or less like what I can see through my veranda window – than it is to travel in the direction of the future.

I once read somewhere that Chinese history, culture, art and even language could not be imagined without the image of a river – metaphoric, symbolic and even literal. I am told that the first word I managed to utter as a toddler was “mežā” (in the forest), perhaps because for my mother, the forest in Līgatne was a favourite place to take a stroll. So it could be that being in a forest and the feeling of a forest’s presence are as deeply rooted in me as the idea of a river in some Chinese person who might be sitting on a different veranda somewhere on the other side of the world.

Outside my window, the wind gathers speed, grabs on to the foliage, sways the branches, and for a brief moment I have a feeling that I know what the trees are trying to tell me. It could be the same thing they’ve said, the same story they’ve told for millennia – even before the arrival of the first people in these parts. And I hope that they’ll continue to talk this way amongst themselves even after I, and all of us, have become a part of them.

*Engels reproached those who were unable to see the forest for the trees, who preferred to look at the world metaphysically, in his work Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1880). He argued that delving into metaphysics made such people into individualists and prevented them from perceiving what was important in society as a whole.

This article was translated as part of Vagabond Voices’ Think in Translation project, which aims to promote reading in translation, and to make translated works more accessible. Think in Translation has been made possible thanks to The Space and Creative Scotland. For more info, please visit vagabondvoices.co.uk/think-in-translation

About the author: Writer and journalist Pauls Bankovskis was born in Līgatne, Latvia, in 1973. He studied glasswork at the Riga School for Applied Arts as well as philosophy at the University of Latvia (1992–1996). His prose was first published in 1993. Since then he’s published ten novels and two collections of short stories, as well as an award-winning children’s book and a non-fiction work. His focus tends to shift from Latvia’s history, myths and legends to the realities of the recent Soviet past to the possibilities of the future. His novel 18, providing a rich, idiosyncratic vision of a momentous time in Latvia’s history, was first published in 2014 as part of a series of historical novels entitled We. Latvia. The 20th Century. Vagabond Voices published the English translation of 18 in 2017.

About the author: Writer and journalist Pauls Bankovskis was born in Līgatne, Latvia, in 1973. He studied glasswork at the Riga School for Applied Arts as well as philosophy at the University of Latvia (1992–1996). His prose was first published in 1993. Since then he’s published ten novels and two collections of short stories, as well as an award-winning children’s book and a non-fiction work. His focus tends to shift from Latvia’s history, myths and legends to the realities of the recent Soviet past to the possibilities of the future. His novel 18, providing a rich, idiosyncratic vision of a momentous time in Latvia’s history, was first published in 2014 as part of a series of historical novels entitled We. Latvia. The 20th Century. Vagabond Voices published the English translation of 18 in 2017.

The photo above of Pauls Bankovskis is by Stewart Ennis.

The elm has fallen away from public consciousness in favour of our more iconic trees – fir, birch and pine, among others. Here, Max Coleman argues for the elm to regain its central position as a tree worth noticing and nurturing.

Extract from Wych Elm

By Max Coleman

Published by Royal Botanic Garden of Edinburgh (RBGE)

Losing the names for nature in everyday language can be viewed as symptomatic of a wider problem. The common concern about this linguistic loss is that we are gradually losing our sense of connection to nature. Why, after all, would we care about plants and animals we cannot put a name to?

The names of what many people would regard as familiar wildlife are being removed from children’s dictionaries, and this has galvanised efforts to bring nature to life for children. I wholeheartedly support anything that seeks to connect people with nature. My own small contribution to this effort has been to wave the flag for one of Scotland’s most majestic, and also most forgotten, native trees – the wych elm.

The wych or Scotch elm, Ulmus glabra, has been growing in Scotland for around 9,000 years. We know this from radiocarbon dated pollen extracted from bogs and lake sediments. Not only has it been here longer than people have inhabited Scotland, but it has also proved itself to be incredibly useful to us. An unusual quality of elm wood is that the fibres are interlocking. This makes wych elm resistant to splitting and yet flexible at the same time. As a consequence, elm has been the wood of choice for a range of specific uses including wheel construction, boat building, furniture making and archer’s bows.

So why, you might reasonably ask, has a tree with such strong cultural connections, perhaps back to the earliest Scots, fallen from our consciousness? It is not that people don’t care about trees; far from it. Some of the largest and most influential environmental charities have grown out of our love of trees and a desire to protect both trees and woodlands.

Perhaps the most obvious reason wych elm has failed to keep up with the likes of oak, birch and our national tree, the iconic Scots pine, is that we no longer rely on wood as we once did. Unfortunately, the great utility of elm is irrelevant in the modern world. Granted, there has been a revival of interest in bespoke furniture made from native hardwoods, and elm has been prominent in this for its structural qualities and the beauty of its grain. However, the elm items that quietly kept life ticking over such as wheel hubs, boat keels and water pipes have long since been replaced by other materials or new technologies.

Elms of all kinds have also been hit hard by disease which has dramatically reduced their numbers and made them much less prominent in the landscape. This might just seem like bad luck, but in fact is actually due to our own actions. Hardly a month goes by without a new tree health story in the media. Although the media do tend to sensationalise things it is certainly true that the increasing global movement of people and goods, including plants and plant products, has made the inadvertent introduction of pests more likely. This can lead to potentially devastating consequences for trees.

To combat the growing threats to plant health the watch word these days is biosecurity. This involves all of us being much more aware of the risks of moving pests around and taking measures to limit them. Boarder inspections, quarantine facilities and disinfectants are some of the measures that are becoming increasingly familiar. Home grown plants are being promoted to avoid the risks associated with imports. But, as far as the elm is concerned, this is all a case of shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted.

The elms nemesis, Dutch elm disease, is a fungus that evolved into a virulent strain as a direct result of the global trade in timber. The aggressive form of the disease arrived in southern Britain in the late 1960’s on infected timber from America and has been spreading north ever since. When the disease arrives in an area nearly all the elms die, and we no longer attempt to keep track of the losses. The best guess is that between 20 and 80 million trees have disappeared from countryside and town alike. Entire landscapes in England have lost the qualities provided by the distinctively shaped English elm. In Scotland some areas where wych elms were common have also been transformed.

Yet all is not as gloomy as the media would have you believe. Nearly everywhere a scattering of elms have survived. The exact reason why is not yet fully understood, but these trees are a source of potentially disease resistant stock for the future. The other cause for optimism is that northern Scotland is a rare refuge for the elm. Dutch elm disease can only get about courtesy of elm bark beetles. These small flying insects have certain minimum temperature requirements that must be met before they can disperse to new elms. It seems that the far north and west of Scotland may be climatically just outside of the comfort zone of these beetles and so beyond the reach of the disease. Lest we forget it, Scotland’s elms are rare survivors that should be cherished.

Wych Elm by Max Coleman is out now, published by Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh priced £20.

Christopher Somerville has covered the length and breadth of the UK on foot, and has written and broadcast about its history, landscape, wildlife and people for over 25 years. Now, in this extensive new volume, he selects his top 200 routes from his hugely popular Times column, ‘A Good Walk’.

More than just a basic guidebook, this is a meditation on our relationship with the landscape and a celebration of all that Britain has to offer. From Cornwall to Shetland via Pembrokeshire and Barrowdale, this is the most comprehensive collection of walks in the United Kingdom available in one book, and features trails to suit all skill levels and references, whether you want a gentle ramble to the pub or something much more challenging. Featuring stunning photography and using Christopher’s trademark with and lyricism, this is the perfect gift for ramblers anywhere.

Extract from The Times Britain’s Best Walks

By Christopher Somerville

Published by HarperCollins

Creag Meagaidh Nature Reserve, Highland

Start & finish: Creag Meagaidh NNR car park, PH20 1BX (OS ref NN483873)

Walk (8½ miles, moderate, OS Explorer 401): From car park follow red trail (otter symbol). In 500m pass to right of toilets/buildings (479876). Follow path on the level, then up steps; fork right at top (474879; ‘Coire Ardair’)

Long-horned Highland cattle put their heads up from the lush grazing in the floor of Aberarder Forest to peer through their luxuriant fringes and watch us go by.

We were heading for one of the most fascinating nature reserves in Scotland. Creag Meagaidh National Nature Reserve, centred around the great sombre cliffs and corries of the Creag Meagaidh range, has embarked on an ambitious programme to encourage the recolonisation of this rugged mountain landscape by the native flora and fauna that have been destroyed by overgrazing, deforestation and other manifestations of the heavy hand of man.

We walked a rising path through woods of young birch, oak and alder, free to grow now that the sheep have been removed and the deer controlled. The boggy hill slopes were a silent riot of wood cranesbill’s purple-blue flowers, intensely blue milkwort, stubby white heath spotted orchids, the yellow Maltese crosses of tormentil, and the roll-edged leaves of insect-eating butterwort in lime-green sprays.

Rocks along the path were inscribed with a phrase from a Sorley MacLean poem: “I saw the little tree rising, in its branches the jewelled music” — and that fitted the growing trees, the flower-starred banks and the exuberant singing of chaffinches, meadow pipits and skylarks.

A tiny brown frog bounced away as we brushed against the sprig of heather he was using as a springboard. At the top of the rise the path left the trees and curved west across open moorland tufted with bog cotton. Below in the glen the Allt Coire Ardair snaked and sparkled in its rocky bed. Northwards rose the flattened pyramid head of Coire a’ Chriochairein, and round in the west hung the high, rubble-filled notch called The Window that marks the northern edge of cliff-hung Coire Ardair. A lichened rock lay by the way, the parallel lines in its flat surface gouged out 10 000 years ago by the glacier that formed the precipitous glen.

The top of the glen was blocked by a low barrier of heath and grass, concealing the moraine or mass of rock and rubble that the head of the glacier had pushed before it up the valley, like dust before a broom. From its ridge we looked down to Lochan a’ Choire, suddenly revealed like a conjurer’s trick — a little glass-still lake under black, snow-streaked cliffs.

I ran down and scampered a quick, slip-and-slide circuit of the lochan. Then we sat on a ledge of mica-sparkling rock and ate our sandwiches to the glide and plop of small fish — Arctic char, residents of Lochan a’ Choire since they were isolated up here in the great melt at the end of the last glaciation. May they thrive another 10,000 years in this most beautiful mountain nature reserve.

The Times Britain’s Best Walks: 200 classic walks from The Times by Christopher Somerville is out now published by Harper Collins priced in various formats.

Collins has been working alongside wildlife charity Butterfly Conservation (BC) to create a guide perfect for budding explorers. With plenty of species to spot, including the Scotch Argus butterfly (native to Scotland), this little guide is an amazing companion during the warmer seasons for a spot of butterfly and moth spotting in the outdoors.

With nearly 60 different species of butterflies and over 2,500 species of moths in the UK alone, there’s plenty to discover and learn along the way.

Available at just £2.99 the i-Spy Butterflies and Moths is the latest addition to the modern range, alongside new titles i-Spy Garden Birds, i-Spy In the City and i-Spy At the Shops.

i-SPY Butterflies and Moths is published by Collins an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers at £2.99.

Author Lindsay Littleson takes us on a walking trail around Paisley to discover locations from her latest children’s novel, A Pattern of Secrets, published by Cranachan Publishing on 16 April 2018.

In 2015 my WW1 novel Shell Hole was shortlisted for the Dundee Great War Children’s Book Prize and I enjoyed engaging in research so much that I was inspired to write another historical novel, A Pattern of Secrets, this time focusing on Paisley, my local area.

A Pattern of Secrets, which is aimed at 9-12 year olds and is being published in April by Cranachan Books, is set in Paisley in the 1870’s, when the shawl industry was failing and the Paisley weavers were facing destitution.

The story is told from the perspective of two children; Jessie, the feisty daughter of a wealthy Paisley shawl manufacturer, and Jim, a homeless boy on a desperate quest to save his family. Jessie joins Jim in a frantic race against time to solve the mystery of a missing heirloom and rescue his mother and siblings.

The main character is Jessie Rowat, a Paisley girl who in real life grew up to become a suffragette and an accomplished artist and clothes designer. She was one of the famous Glasgow Girls and she and her husband, the artist Fra Newbery, were close friends of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Jessie’s life story was fascinating to research. She founded the embroidery department at the Glasgow School of Art and her embroidered stylised roses were an inspiration behind the famous Mackintosh rose.

As a teacher in the Paisley area, I’m keen that A Pattern of Secrets can be used by local schools as a novel study when they are learning about their town’s history.

I created A Pattern of Secrets: The Tour because I wanted to encourage pupils to go beyond the classroom, get outside and see their home town in a new, more positive light. Paisley’s textile glory days may be in the past, but its rich history is all around, sewn into the fabric of the place.

A Pattern of Secrets: The Tour!

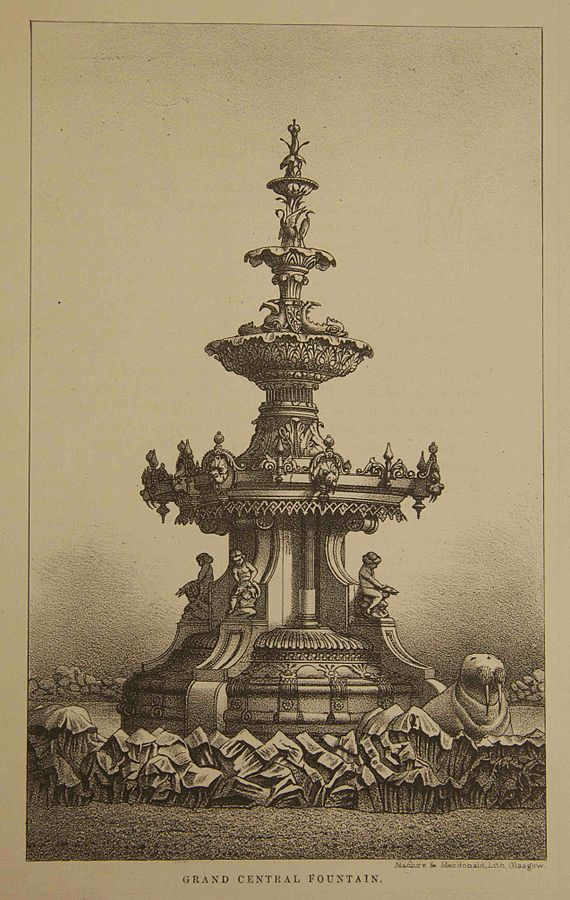

Stroll through the Fountain Gardens and admire Grand Central Fountain, which was restored in 2014 and features four life-size walruses.

Walk from Oakwood (former location of Paisley Grammar School), down School Wynd, along New Street and into County Place (now renamed County Square). The County Buildings and Prison on the right of the square have been replaced by a shopping centre, the Piazza. The hansom cabs have gone too but Gilmour Street Station is still there.

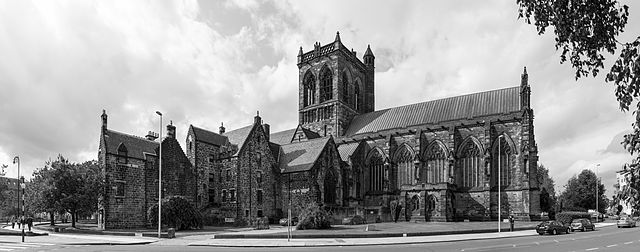

As you head towards Paisley Abbey, look for statues of George Clark and Peter and Thomas Coats, owners of Paisley’s biggest thread mills. The Abbey welcomes visitors and has a cafe and gift shop.

Many of the street names in Paisley are reminders of the town’s textile heritage. Look out for Silk Street, Gauze Street, Lawn Street, Cotton Street, Thread Street, Miller Street, Shuttle Street and Dyers Wynd.

If you have time, check out the exterior of St Margaret’s in Brodie Park (William Rowat’s family home has been recently converted into luxury flats).

There are lots of places readers of A Pattern of Secrets might like to visit to find out more about Paisley’s history in the textile history, including the Paisley Thread Mill Museum, the Sma’ Shot Cottages and the Paisley Museum and Art Gallery, where paintings by Jessie’s husband Fra Newbery can be viewed too.

Cranachan’s Yesteryear books are a fabulous way of discovering the ‘story’ in history, and getting outside and looking around the area where real life events happened, helps bring the story to life.

Images: Photo p160: Grand Central Fountain by Maclue and Macdonald, Lithographera, Glasgow (Public Domain)

A Pattern of Secrets by Lindsay Littleson is published by Cranachan Publishing

Svörður (eastern Iceland) – Turf, Peat

My great-uncle Allan was the one man I associated more than any other with the moorland during my childhood. During the last days of his life, however, he spent all his days lying in his bed, his old and grizzled face looking up briefly from his pillow when I entered the room.

‘Hello, Dan, ’ he would say, using one of the diminutives that were sometimes employed in the village for those with my forename. *