David Robinson has a bloody encounter with Alan Parks, the newest writer on Glasgow’s gritty crime writing block. Robinson considers how Bloody January – set in the 1970s – adds to the already ‘crowded corner of Clydeside crime fiction’ and finds it a punchy exploration of the darker side of life in Scotland’s largest city.

Read enough crime fiction set in Glasgow and it’s an easy enough scene to imagine. Early evening in a city centre pub, probably not too far from police HQ in Stewart Street. DI Alex Morrow is comparing notes with DS William Lorimer at one table, DI Colin Anderson and DS Freddie Costello are doing the same at another, forensic scientist Rhona MacLeod and investigative journalist Rosie Gilmour are chatting about old cases at a third. The door opens and detective Harry McCoy walks in.

The others look up, because he’s a new kid on the block. They don’t know too much about him, what kind of back-story he’s got, what sort of cases he already has under his belt. All the rest have been around for at least five books in series by Denise Mina, Alex Gray, Caro Ramsay (the Anderson & Costello series), Lin Anderson and Anna Smith respectively. There are, of course, plenty more Glaswegian crime writers than this, but the point remains: of all Britain’s cities, Glasgow is the most thoroughly policed by serial fiction.

So when Alan Parks’s debut novel Bloody January comes to us from Canongate already badged as “a Harry McCoy novel”, it’s a rather obvious clue to his publisher’s expectations. We’ll be seeing, they are saying, a lot more of him. The quotes on the cover (“The natural successor to William McIlvanney” – John Niven) back that up. But in the crowded corner of Clydeside crime fiction, what’s left to say? And, while we’re at it, how come Glasgow has such a stranglehold on the genre?

One key difference with Bloody January is its setting: the January in question is that of 1973, a whole decade before Taggart hit the small screen, two decades before anyone heard of tartan noir, and four decades before crime fiction became so important that it had to have its own literary festivals. For a crime writer, a Seventies setting has two key advantages: the absence of mobile phones makes plotting easier, and they can also shock readers into realising how much has changed by writing dialogue pitted, Life on Mars-style, with prejudices that are now almost silenced.

But the Seventies appealed to Alan Parks for an altogether different reason. Born and reared in Elderslie, he left Scotland to work in London in the music industry. He was a creative director for record companies such as London Records (where he befriended novelist John Niven), but when the industry effectively collapsed, he moved back to Glasgow in 2015.

“I’d find myself going on walks around the city, often to places I hadn’t seen since I was ten, back in the Seventies. I think that’s an age when things go in deep, even though at the time you are completely self-absorbed and don’t register them. So I thought that would be a good time to set a novel in too.”

He also wanted it to cover as wide a range of society as possible, and maybe again part of that impulse stems from his childhood. “We always used to catch the bus back to Elderslie from just by the St Enoch’s Hotel, and we’d see all those poor people there, huddling by the hot air vents and drinking god knows what. And we’d be going to Fraser’s or somewhere like that and it would all be very jolly, but then you’d see all those people still there when we caught the bus back. People always think that Glasgow is a poor town, but there has always been a level of glamour too, a wealthy strata, and I though there’s be an interesting contrast looking at those two sides of it.”

It’s true: when Parks’s Detective Inspector Harry McCoy starts his investigations, they range dizzyingly from lowlife to high, from taking drugs with his prostitute girlfriend to finding out the nefarious deeds perpetrated by an aristocratic shipyard owner. Hold on a minute, you might think: drug-taking policemen in the Seventies? But that’s only part of McCoy’s crowded back-story. One of his closest friends, Stevie Cooper, is now the boss of one of the city’s gangs. They’ve been close since Cooper stuck up for him against the priests in the children’s home. Yet while McCoy often has to turn a blind eye to whatever Cooper is currently up to, he still has a moral compass of sorts. Unlike many of his colleagues, he’s not on the take.

That kind of compromised, yet still idealistic, cop has now become familiar enough to us: it’s Jimmy McNulty in the TV series The Wire, or – closer to home, Alex Morrow, with her gangster half-brother, in Denise Mina’s fiction. But how plausible was such a character in the Seventies?

“Maybe there was a bit of dramatic licence there,” Parks admits. “Because when you look at their photos, the Glasgow police force of 1973 wasn’t too different from the early Sixties or even the Fifties – all suits, ties and trilbies. London may have been changing at full tilt in the Swinging Sixties and Carnaby Street pumping out new fashions, but none of that seemed to spread up here.”

To give Bloody January the social sweep Parks wanted, he needed to show gang life from the inside. There’s a neatly bleak example of that when McCoy visits his gangster friend in his drugs den as an informant is being tortured next door. “How d’you stand it?” he asks a girl working there. “Stand what?” she replies. And if violence is as commonplace as that, so too is rule-breaking by the police. In the very first chapter, a prison warden at Barlinnie asks McCoy whether his colleagues fitted up one of the inmates. “Nope,” McNulty replies, “whole thing was straight for once.”

Yet this old order of ubiquitous violence and police corruption is slowly changing. That dialogue takes place just outside the Special Unit at Barlinnie, set up, we are told, “by hippies blabbering on about Art Therapy, Positive Custody and Breaking Barriers”. Before too long, McCoy will be chatting up a sociology postgraduate student, asking her about feminism. There’s a David Bowie gig at Green’s Playhouse. Our post-millennial world is taking its time, but it’s on the way.

The old one, though, is still in focus: indeed, short of a Tardis, says John Niven, this book is the best way of getting back to Seventies Glasgow. Niven is a biased witness – he and Parks are friends, and without his encouragement this novel probably wouldn’t exist – but that doesn’t stop him being right on this occasion. The Seventies are here in all their seediness: old copies of Parade on the pavements, TVs on tick from DER, smokers lighting up one Kensitas after another. Familiar places like Paddy’s Market are sharply described (“there was nothing it didn’t have and nothing you’d want to buy”), but because the city has been knocked about a bit, even McCoy still has to search out old landmarks like the Pinkston chimney to work out which way he is facing.

Change is coming. You can see that far clearer in this novel than any written at the time. But any future gathering of Glasgow’s fictional detectives can relax. The new kid on the block won’t let the side down.

Bloody January by Alan Parks is out now published by Canongate, priced £12.99.

Bloody January by Alan Parks is out now published by Canongate, priced £12.99.

This official story of the Homeless World Cup explores how it has become such a global phenomenon. Showing how the power of sport can help excluded people transform their own lives, we gain insight into the origins of this unique tournament.

Extract from Home Game: A Ball Can Change The World

By Mel Young and Peter Barr

Published by Luath Press

From Zeroes to Heroes

The Homeless World Cup started as a “crazy idea” dreamed up by two journalists over a couple of beers in a beach-side bar in Cape Town in 2001. Since then it’s become a global organisation with partners in 75 countries, helping to transform the lives of well over one million people, thanks to the power of football.

According to researchers, the vast majority of the people involved have found a place to live or a job, continued education, rebuilt their relationships, recovered from a drug or alcohol problem or regained their mental health. In economic terms, this is a huge contribution. In human terms, it’s priceless.

The tournament has also had a major impact on the media, business, the government and general public, helping to transform their perceptions of homelessness and homeless people.

The early days were difficult, persuading other people and organisations to agree with us “a ball can change the world.” But gradually, the crazy dream gathered momentum.

When the first tournament kicked off in Graz in Austria, no-one knew what to expect. As Home Game describes, there were many more questions than answers:

“Will the tournament be a success? Will the players get on with each other? Will the football be good? Will the crowds turn up? How will the people of Graz respond? What will the media say? How will the players cope with the experience? Most of them have never been abroad before, and many are still fighting drug or alcohol problems. How will they handle the pressure? Will the managers and volunteers also be able to cope? Will Graz be a one-off event? Will the tournament have any long-term impact?” (Home Game page 76)

In Graz that day, our vision was becoming a reality, as 144 players paraded around the arena, but that was just the start of a phenomenon that since then has captured the hearts and minds of millions of people all over the world, from Graz to Oslo last year, via Edinburgh and Melbourne, Paris, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Rio, Santiago, Glasgow and Mexico City – a total of 15 cities so far have hosted the annual event.

The beginnings of the Homeless World Cup were a struggle but nothing compared to the struggle of all of the players. One day, they are homeless. They’re excluded. They’re the poorest of the poor. They’re “the people who do not exist.” But when they represent their countries at the Homeless World Cup, they are cheered on by thousands of people and asked for their autographs – transformed from zeroes to heroes.

Every year, some people say, “The players do not look like homeless people,” and we ask them, “What do homeless people look like?” What has happened is that all of the players have already set off on their journey. When they arrive at the event, they are fitter and healthier, better prepared for the challenge. But the tournament itself is only one step on the journey. It is part of the process. It is just the beginning. The struggle continues.

Home Game: A Ball Can Change The World by Mel Young and Peter Barr is out now published by Luath Press priced £16.99.

Home Game: A Ball Can Change The World by Mel Young and Peter Barr is out now published by Luath Press priced £16.99.

This historical novel for teens vividly imagines the life of the woman who could have been behind Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece. When Lisa crosses paths with the great painter, his portrait of ‘Lovely Lisa’ will become his masterpiece, and her smile will capture the imagination of the world.

Extract from Smile: The Story of the Original Mona Lisa

By Mary Hoffman

Published by Barrington Stoke

“Lovely Lisa,” he always called me. Of course, I was a baby then so I don’t know if I remember his words or if someone told me. But whenever I felt sad about something I hugged the words “lovely Lisa” to comfort me.

I hugged, too, the knowledge that Leonardo, the greatest artist in Italy, drew my portrait when I was little.

I was the first child born to my parents. I know now that my father’s first thought was probably, ‘A girl? Oh no! I’ll have to find a dowry if she’s to have a husband.’ But in the four golden years before my little brothers and sisters came along, I never felt that Father was disappointed in me.

And his second thought might have been, ‘At last – a living child!’ Father had lost two wives and the babies in their wombs before his third wife, my mother, made him a father. He loved me the more because of that, I’m sure.

We were not rich, but not poor either. We lived in the magnificent city of Florence – in a rented house in a rather smelly street on the south side of the river. My father insisted that our family was noble in origin and that – as a nobleman – he had no need for a job.

He owned farms outside the city and the money we lived on came from the rents that farmers paid him and the sale of wheat and animals. And as our family grew, with my three brothers and three sisters, the money had to stretch further.

So, what I remember of my early childhood was lots of love, especially from my father, enough food and clothes but nothing grand, a house in stinky old Via Squazza, and the story that a great artist had drawn my picture as a baby.

But I knew it was more than a story because that great artist, Leonardo da Vinci himself, had left my parents one of his drawings. Of course, Leonardo wasn’t so well known then. As I got older, I asked my parents about him and found that he had left Florence when I was three to go to work for the Duke of Milan.

And yet I could just remember the young man with the long fair hair and the velvet cloak the colour of roses. He was so very good-looking that I thought he was some kind of angel.

Leonardo was nearly thirty when he drew me for the first time. His father was Piero, a notary in the city, and Leonardo was his only child.

“But born out of wedlock,” my mother insisted. She took a strict view on such matters. “It was good of Piero to accept Leonardo as his son, when he was the result of a tumble with a servant.”

Even when I was very young and innocent, I felt this wasn’t quite right. Piero didn’t deserve praise for that. I knew it took two people to make a baby.

And so Piero da Vinci accepted this son, who turned out to be such a remarkable man. Piero and his first wife – for old Piero would go on to have four wives and twelve children – both raised that first boy.

Because he was born out of wedlock, Leonardo couldn’t be a lawyer or a doctor or even a notary like his father. And so, when his talent began to show, Leonardo was made apprentice to one of the city’s great painters – a man called Andrea with the nickname “of the True Eye”.

A Note on Smile from Mary Hoffman

There have been many theories about the woman who posed for Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait known as Mona Lisa, now in the Louvre Gallery in Paris.

I believe that the most likely model is Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a Florentine silk merchant called Francesco del Giocondo. The painting is sometimes called La Gioconda, which could mean “wife of Giocondo” or “the happy one”, which fits well with the portrait’s famous smile.

Leonardo never handed over his painting to Francesco del Giocondo. He still had it when he died in France in 1519, more than ten years after he left Florence. It must have had some deep personal meaning for him.

I have made the story of Smile up, apart from the facts of births, deaths and marriages.

Smile by Mary Hoffman is out now published by Barrington Stoke priced £6.99.

Smile by Mary Hoffman is out now published by Barrington Stoke priced £6.99.

MacSonnetries by Petra Reid is a collection of 154 sonnets. With each taking inspiration from one of Shakespeare’s sonnets, the result is a post-modern, and often post-human, response to the work of the great bard. Sometimes shocking, the sonnets explore our contemporary world at social, political, cultural, and ideological levels.

Extract from MacSonnetries: The Buds of May Be

By Petra Reid

Published by Scotland Street Press

The Beginning was not Hard to Find

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel:

That thou art now the world’s fresh ornament

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within in thy own bud buriest thy content,

And, tender churl, mak’st waste in niggarding:

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

R1.

Twenty-first creatures desiring increase

freeze their breeds, lest they turn tardy, or die;

bacterium you halted from decease

brings the self perfect future memory.

(She’ll be my double but with bigger eyes;

Amazon’s shipping five star ahem, fuel;

ne plus ultra’s where man’s future lies,

lending random sperm an ovum’s plain cruel.)

What price hard labour for world’s ornament,

how to digitalise mum’s gaudy spring?

I’m streaming my sweet uterine content:

Facebook foetuses rock – quit niggarding!

Guys! You can preview mini me-to-be

on nordicdads.com – like my wee thee!

There is a theory that Shakespeare was commissioned to write the first eighteen sonnets in his 154 sonnet cycle as a means of encouraging a young nobleman to marry. These “Reproduction” sonnets were my first encounter with that opus, and the eugenic nature of Sonnet 1 is very much of the scientific moment. What also struck me was how any prospective bearer of the noble seed in question had no representation in Shakespeare’s vision of birth inheritance – this is unsurprising, but ripe for reconsideration!

All of Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets have been answered with a voice responding to the dynamic of human relationships in our present and future of hyper-connectivity and Artificial Intelligence. Inspired by The Golden Shovel method (invented by American poet Terrance Hayes), I used some Silver Shears to detach line endings of each Shakespeare sonnet and transpose them onto a corresponding “R”, or “Response”, sonnet. Responses R1 through to R154 address DNA to badly behaved hen parties to co-opting the “Dark Lady” sequence for an exploration of bereavement and Mary Queen of Scots’ real legacy!

On his death, Robert Burns owned two complete collections of Shakespeare’s works. Two of the sonnet responses are translated into Scots, while the remainder play between colloquialism, arch rejoinder and vulgar humour. Burns’ “Merry Muses of Caledonia” was initially only for private circulation, as were Shakespeare’s sonnets (gate-crashing the lad parties was fun, both north and south of the border); there are some scant and highly subjective notes throughout alluding, not only to my own preoccupations, but to a broader picture of the personal/political situation we’re in just now. For example:

R60.

Birds on the game wave from 50+ shore,

we seniors who’d hoped for respectful end;

transpires we have to die quickly before

butchered pensions are all WASPI’S* contend;

nothings are our equity, slits of light;

Liz, ER I, the virgin queen as crowned,

beheaded her cousin—what a cat fight!

So let us male-hearted cougars confound

theft of contributions made in our youth;

no dead lead foundation but Botox’d brow;

young men seem to prefer us, in all truth,

altho’ the lady garden’s scant to mow**.

Byee! chaste life from bare shores where we stand;

tide’s rolling in on the State’s helping hand.

* Women Against State Pension Inequality

** See Nae Hair On’t by Robert Burns.

R154. Finis. Obvious. But it led to another beginning for me: how to translate the “R’s” into performance? There’s a flautist, who tells me that his playing style is influenced by the Celtic accent. For the launch event of the collection, we’ll be exploring this, playing it out with spoken voice. The beginning, the ending, always rests on one word, one note. Love.

Out on February 7 in time for Valentine’s Day, MacSonnetries will be published by Scotland Street Press priced £9.99.

Out on February 7 in time for Valentine’s Day, MacSonnetries will be published by Scotland Street Press priced £9.99.

MacSonnetries launches at Blackwell’s in Edinburgh on February 7; book your free ticket here.

Sue Reid Sexton travels solo in a tiny campervan. Using it as a creative space and general escape hatch, for a day or weeks at a time, she disappears up glens and over mountains to write novels. Writing on the Road is about these flights, but it’s also a travel journal and a guide to living in the moment, to coping when marriage unravels, and staying creative against all odds. And how not to be scared of the dark…

Extract from Writing on the Road

By Sue Reid Sexton

Published by Waverley Books

Beware, also, of the phone call to ‘civilisation’. One night recently my equilibrium was disturbed when, seeking reassurance, I called a friend who turned out to be a few sheets to the wind and speaking truths best kept to himself. I finished the call then drove three miles down the beautiful western side of Loch Awe, as I’d previously planned. This is a long leafy road with almost nothing man-made on it, very beautiful I’m sure, and on a brave more settled day I might have continued. But the call had ruffled me and caused nomophobia to kick in. I turned and came back to a busier spot on the eastern side of the loch. The sunset and early morning view were spectacular from this other road’s height, though if I’d known juggernauts were going to shake me awake at five in the morning I might have gone elsewhere.

It’s worth noting how, from the comfort of my warm sleeping bag, I considered the possibility of being smashed to pieces as they rollicked past, but concluded it was a risk worth taking, such was my comfort, and went back to sleep. It’s all relative, isn’t it?

And speaking of relatives, I try not to fall into the trap of succumbing to their fears as well as my own. As Robert Louis Stevenson said, ‘Keep your fears to yourself, but share your courage with others.’ This is a very caring outlook. Many of my family members are also writers. We have some artists and musicians too. When I’ve shared my concerns about the weird guy in the campervan next door, or the violent storm approaching my Tupperware box on wheels, these loving people either ridicule my overactive imagination which, coming from a family of vivid imaginers is a bit rich, or they express their love by suggesting I panic and leave immediately. I’m not sure withholding your fears in order to avoid having them ridiculed or magnified is what RLS meant, but his advice holds water. Your anxiety feeds that of others, which in turn feeds yours. You get caught in a whirlwind of fright just when you were seeking the sunshine of their love.

‘If the wind hits you sideways you’ll be blown right off the road, over the dry-stane dyke and into the valley below. Of course your entrails will be picked over by ravens, so it’s very environmentally friendly, not to mention deeply in tune with the universe,’ said another sarcastic friend when I phoned her from a similarly remote spot on a previous trip. From the darkness of my van, I imagined her lounging on a reassuring and deeply cushioned sofa by the telly. In truth, the laughter her own joke caused her was weirdly comforting.

Or, you can brave it out and tell everyone how great the solitude of the mountain was, how exciting the wind, how beautiful the sky, how cosy your tiny bunk, how interesting the odd man in the next camper is, how inspiring the resounding silence and how you wrote a story which derived from a mad dream you had last night in the light of a starlit sky with the trees turned inside out like white ghosts. In time your bravery will be real, but it can never be real if you don’t go there and survive, and aim to thrive, as you inevitably will.

Writing on the Road: Campervan Love and the Joy of Solitude by Sue Reid Sexton is out now published by Waverley Books priced £8.99.

by Sue Reid Sexton is out now published by Waverley Books priced £8.99.

You might also enjoy this exclusive article ‘Writing En Route’ by Sue, chronicling her trip to through the Midi-Pyrenees with her trusty campervan, on Books from Scotland.

Sue Reid Sexton appears at the Dundee Womens Festival on Thursday 15 March 2018 from 6 to 7pm, with ‘Writing on the Road: staying happy and creative in a campervan’. Please contact Central Library, Dundee to book a free space on 01382 431500.

Sita Brahmachari takes us back in time to a life-changing day fifteen years ago, that went on to become the inspiration for her heartwarming tale for children, Zebra Crossing Soul Song. A huge music lover, Sita reveals the soundtrack to which she wrote the book, and shows how her musical heroes shaped both characterisation and story.

What inspired Zebra Crossing Soul Song?

Fifteen years ago, when my son was four years old, a zebra crossing man saved his life. I wasn’t a published author then but as I have been scribbling stories and squirreling them away since well before Lenny’s age I wrote this in my notebook:

‘Zebra Crossing Story’

A story about a Zebra Crossing man who saves a boy’s life […] the crossing as a place of learning, growing, philosophy, psychology music, river, life. In the story that has emerged all these years later, Lenny looks back at his growing up through memories on the crossing from nursery to sixth form. As I wrote I was taken back to the hideous moment that every parent and carer fears of losing sight of their young child, only to find them heading for a busy road.

The Zebra stripes are no longer accompanied by a crossing person but every time I walk across the zebra I thank the crossing man for saving my son’s life. While writing I found myself listening to some of my favourite music tracks to allay the sense of panic that comes whenever I think of that moment on the road. The tracks I played have become the accompanying sound track of Zebra Crossing Soul Song.

Although I knew little about the crossing man who saved my son’s life, the character of Otis came to me… his name of course borrowed from Otis Redding – after all he had and has my true ‘Respect’.

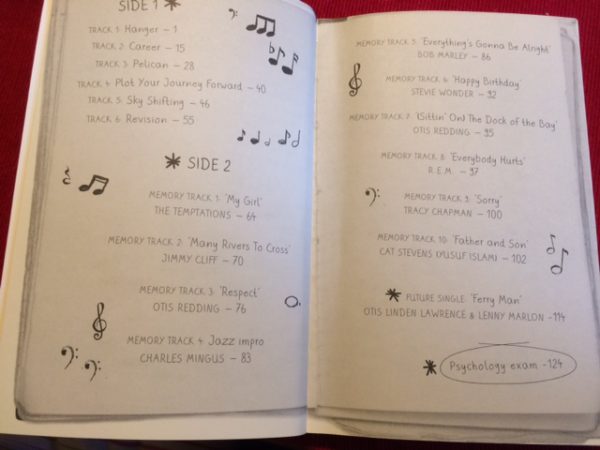

I wrote ‘Zebra Crossing Soul Song to this playlist…

There are no chapters in ‘Zebra Crossing Soul Song’, but tracks and a playlist to listen as you read.

Listening to ‘Father and Son’ by Yusuf Islam (formerly Cat Stevens) gave me the idea to create a lyrical dialogue between a boy and the Zebra Crossing Man who saved his life many years before. It also prompted me to create a different kind of family unit than that song depicts. Lenny has two dads in Kwame and David. Many people have influenced Lenny’s growing up but it’s Otis who has had the greatest impact.

“He taught me to think of words like songs

in my head

Otis was the best teacher I ever had

And now school’s ending

No Island in the middle

Otis is gone

And I’m moving on

Otis was a crossing man

Otis was a ferry man

Otis was a river of thought

Otis was a river of words.”

(Lenny’s song for Otis from Zebra Crossing Soul Song)

Recently I listened to a radio programme about the increase in the search for ‘perfectionism’ among young people and the negative impact it’s having on levels of anxiety and mental health. From what I gleaned the psychiatrist said the causes had interlocking spurs but were broadly:

- Personal as public – the presence of the Selfie and the production of ourselves, and our bodies as a potential site of perfectionism targeted for improvement. ‘What’s your best angle?’

- Educational – the constant reaching for targets and A* results rather than a focus on the process of learning.

- Societal – the need to bring order to a world that can seem increasingly unpredictable, insecure, fractured and chaotic… where plotting a future path may seem for many young people an impossible task.

In Zebra Crossing Soul Song Lenny struggles with the pressures and challenges that growing up today places on all young people stepping out into the world. He’s re-taking his A Level Psychology and struggling with revision on the subject of ‘memory.’ There are so many questions and expectations… Why did Otis ‘lose it’ on the Crossing? Why has he gone away? What will Lenny do with his life after exams? He’s drowning in the Career Fair requirements to ‘Plot his journey forward’ and he’s lost the one person in the world he could really work things out with.

But Lenny, like Otis is growing into a songman… finding in music a place to be, to relax, to explore his deepest thoughts, ideas and aspirations for himself and the impact he can make on the world, but most of all Lenny is starting to find out that there is more than one way to make the crossing.

Zebra Crossing Soul Song by Sita Brahmachari is out now published by Barrington Stoke priced £6.99.

by Sita Brahmachari is out now published by Barrington Stoke priced £6.99.

The Return of the Young Detective

By Kirsten Graham, Marketing, Floris Books

As a child, I loved a good mystery story. As a nineties kid, the proper classics like Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys were a bit old fashioned for me, but I remember my mum trying to persuade me of the merits of both. An Enid Blyton box set on my birthday one year got me hooked on the adventures of The Famous Five and The Secret Seven, and while I never understood why ginger beer was their beverage of choice, I loved the independence and the freedom that the central characters had, allowing them to take matters into their own hands, rather than relying on adults to solve the mystery.

And that, I think, is why the young detective genre has been making a comeback in children’s literature over the last few years. For children to read about people their own age outsmarting the adults and solving the case brings a sense of empowerment that helps them to become more confident individuals.

From Robin Stevens’ Murder Most Unladylike to Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events and Lauren Child’s Ruby Redfort, it seems that there is once again a young detective to match the interests of any child.

Here at Kelpies HQ, we’re fully embracing the trend, with three brand new young detective series debuting in 2017. Read on to meet your new favourite detectives!

Top-Secret Grandad and Me – David MacPhail

Since his dad literally did a vanishing act (he’s a magician), 12-year-old Jay Patel has turned detective. With the help of his grandad (who also happens to be possibly the world’s worst ghost), he’s on the case of a dead body that has vanished from the library of his Glasgow primary school.

Read this if you like quirky characters, wacky plot twists and plenty of silly, slapstick humour.

Top-Secret Grandad and Me: Death by Tumble Dryer (Book 1) is available now, and part of the Summer Reading Challenge 2018.

Look out for book 2, Death by Soup, in summer 2018!

The Artie Conan Doyle Mysteries – Robert J. Harris

A ghostly lady in grey. The paw prints of a gigantic hound. This case can only be solved by the world’s greatest detective. No, not Sherlock Holmes!

Meet boy-detective Artie Conan Doyle, the real brains behind Sherlock Holmes. In the first book in the series, Artie and his best friend Ham uncover the secrets of the sinister Gravediggers’ Club and soon they find themselves pitted against the villainous Colonel Braxton Dash. Will Artie survive his encounters with graveyards and ghosts in the foggy streets of nineteenth century Edinburgh – or will his first case be his last?

Read this if you like sharp, witty dialogue and want a thrilling introduction to the world of Sherlock Holmes, with a nod to the originals.

Artie Conan Doyle and the Gravediggers’ Club (Book 1) is available now. Look out for book 2, Artie Conan Doyle and the Vanishing Dragon, in March 2018.

You might also enjoy this article, ‘Writing for the Young Protagnonist’, by Robert J Harris here.

Museum Mystery Squad – Mike Nicholson

Some people think that museums are boring places full of glass cases, dust and stuff no one cares about: wrong! In a hidden headquarters below the exhibits there’s a gang ready to handle dangerous, spooky or just plain weird problems: the Museum Mystery Squad.

Techie-genius Nabster, mile-a-minute Kennedy and sharp-eyed Laurie (along with Colin the hamster!) tackle the surprising conundrums happening at the museum. From pre-historic creatures that move and secret Egyptian codes to missing treasure and strange messages from the past, there’s no brain-twisting, totally improbable puzzle the Squad can’t solve.

Read this if you like zany illustrations, weird and wonderful facts, and interactive puzzles and activities throughout the story.

Museum Mystery Squad and the Case of the Moving Mammoth (book 1), Hidden Heiroglyphics (book 2) and Curious Coins (book 3) are out now.

Look out for book 4, Museum Mystery Squad and the Case of the Roman Riddle, in April 2018 – it’s also part of the Summer Reading Challenge 2018.

Kate Blackadder, author of Stella’s Christmas Wish, introduces her festive novel and explains why she chose to set the narrative in Edinburgh.

I wrote a novel about a Scottish girl, Stella, working in London, who has to rush home to Melrose when her grandmother is taken to hospital, unconscious after a fall. Her sister Maddie seems to have gone missing from her flat in Edinburgh, a mystery emerges from their granny’s background, and on top of that Stella doesn’t want to bump into her ex-boyfriend, Ross, from whom she parted acrimoniously.

An early draft of the novel won the (unpublished) Romantic Novel prize at the Scottish Association of Writers’ Conference in 2014. When I rewrote it some time later I thought it would add to the drama to set the novel at Christmas time. Edinburgh, where I live, has become a winter destination as well as a summer one with a wonderland of delights in the city centre. Even if you have a lot of worries on your mind, as Stella does, the lead-up to Christmas is hard to avoid, so that became part of the story from the moment she emerges from Waverley Station and sees the Christmas tree on the mound.

Extract from Stella’s Christmas Wish

By Kate Blackadder

Published by Black and White Publishing

‘Waverley Station. This train terminates here. Please make sure you have all your luggage with you.’

The announcer’s voice jolted Stella out of her thoughts. She picked up her shoulder bag and her handbag, took her jacket from the rack, and walked down the train to retrieve her suitcase.

She hadn’t been back in Scotland since last Christmas. Maddie was right. It did smell different. Not necessarily better, here in the station, just different. It sounded different too. Funny how one’s ear became attuned to the sounds of another place.

And it was different in temperature – a chill wind whirled around her as she walked out of the station and along Waverley Bridge. She stopped for a moment to look around, at the heart of the city she’d spent her student years in, and her working life before she went to London.

There was Edinburgh Castle, on its rock above Scotland’s capital city, imposing its presence on the place as it had done for the last seven hundred years. It was up there, on the castle ramparts, that Ross first told her that he loved her. She averted her eyes, quailing at the thought that everywhere in the city there would be a reminder of him – they’d had so many good times here.

Considering how unfestive she was feeling, the very evident signs of the Christmas season came as a shock. On the Mound stood the tall spruce tree – one was donated to the city every year by the people of Norway, Stella remembered. Beside the dour grey towering Scott Monument a colourful fairground ride whirled incongruously and, further along, a gigantic wheel lifted customers above the rooftops. Silvery-white lights were wound round the trees along the edge of Princes Street Gardens, and on the other side of the street party dresses and gifts filled the shop windows.

The clock on the Balmoral Hotel showed half past twelve. She was about to hail the nearest taxi when she heard someone saying her name.

‘It’s Stella, isn’t it? Maddie’s sister?’

The friendly face, framed by shiny brown hair, did look familiar but Stella couldn’t think where she’d seen her before.

‘Isabel. I share a flat with Maddie.’

Of course. Maddie’s new flatmates were Isabel, who she knew from art college and whom Stella had met briefly once, and Skye who had the workshop next to her.

‘Isabel, of course. Do you work near here?’ Stella tried to gather her thoughts.

Isabel indicated the large department store across the road behind them. ‘I’m a buyer in the homeware department,’ she laughed. ‘So much for the art history degree. I’ve taken a half day’s holiday to do some Christmas shopping – didn’t expect to see you! Have you got off the train?’

Stella nodded. ‘My – our granny’s ill. She had a fall.’

‘I’m really sorry to hear that. That will be a shock for Maddie when she’s so far away,’ Isabel said, her face concerned.

‘Where is Maddie?’ Stella found herself reaching out and gripping Isabel’s sleeve. ‘How can I get hold of her?’

Isabel looked very surprised. ‘Didn’t she tell you? She went to Australia on Sunday. There was a stopover somewhere but she’ll have arrived by now.’

‘Australia!’

‘Yes, it all happened very quickly. I never know what Maddie’s going to do next but this was sudden even for her! Ross and Skye took her to the airport.’

‘Ross and Skye?’ Once again Stella echoed Isabel’s words.

‘Ross Drummond, you know, from … yes, of course you know him, sorry.’ Isabel looked embarrassed. ‘Skye’s our other flatmate – Maddie only got to know her this year so you’ve probably not met her. But what about your granny? You call her Alice, don’t you? Is she in hospital?’

Stella burst into tears. Isabel drew her to the side of the pavement out of the way of people rushing to and from the station.

‘She fell off a ladder,’ Stella hiccupped. ‘I’m on my way to see her. They don’t know yet if there’s any brain damage.’ She wiped her face almost angrily. ‘But I don’t understand about Maddie. Why – was it something to do with her work?’ Although she couldn’t imagine that was likely. ‘Will she be back for Christmas?’ But that was hardly likely either – the twenty-fifth was less than a week away. And how come ‘Ross and Skye’ were involved, she wondered, but not aloud.

Stella’s Christmas Wish by Kate Blackadder is out now published in e-book by Black and White Publishing priced £0.99.

Stella’s Christmas Wish by Kate Blackadder is out now published in e-book by Black and White Publishing priced £0.99.

The publication of A New Era coincides with the current exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. Both focus on an area that, until now, has been little known: Scottish modernism. Although Scottish artists were not at the forefront of the European modernist movement, curator and author Alice Strang suggests that they contributed in a wide-ranging and meaningful way.

Extract from A New Era: Scottish Modern Art 1900-1950

By Alice Strang

Published by National Galleries of Scotland Publishing

William Watson Peploe Orchestral Study in Radiation. Pen brush and ink on card c.1915. © National Galleries of Scotland

In 1907 John Duncan Fergusson moved from Edinburgh to Paris. Over the next six years, before the outbreak of the First World War, he occupied a unique position among British artists: living in Paris, he was at the heart of the artistic revolution that overturned centuries of pictorial tradition in the form of Fauvism, Cubism and abstract art. Forty-four years later, in 1951, William Gear was awarded a £500 Festival of Britain purchase prize for his abstract painting Autumn Landscape, prompting questions in parliament about this use (or ‘mis-use’, as many called it) of public money. Almost half a century of engagement by Scottish artists with modernism lies between these two events. That engagement is the subject of this publication and its accompanying exhibition.

What do we mean by modernism? It is often described, when referring to the visual arts and literature, as a utopian art form that turned its back on traditional narrative and questioned the means of its own making. So, in literature, in the work of James Joyce and Ezra Pound, for example, the construction of a coherent story is not the main point, but the use of language and the processes of the writing are. Similarly, in painting, in the work of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, colour, line and brushwork are removed from their traditional mimetic role and they become the story themselves. This shift away from storytelling towards an art that is self-referential and critical of its own means of production is equally evident in abstract expressionist painting, Minimalism and much twentieth century art.

Perhaps the most famous object in the historiography of modern art is a flow chart designed by Alfred H. Barr. The founding Director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Barr conceived the chart for the catalogue of his landmark exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art, held at his museum in 1936. For decades, the exhibition and flow chart shaped our understanding of modern art; to an extent, they still do. The chart outlines a history of modern art that puts Paul Cezanne, Paul Gauguin and the Neo-Impressionists at the top and other tributaries such as African sculpture, the machine aesthetic and Japanese prints all feeding into the bigger river that leads inexorably to Cubism, Constructivism, abstraction and Surrealism. Some great artists who are now highly valued, but were not in Barr’s day, do not fit into this scheme, although their work does bear upon the genesis of abstract art: Hilma af Klint, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and August Strindberg, to name but three.

This reading of modern art came in for criticism from the 1970s: new art-historical approaches going under the banner of ‘the social history of art’, linking semiology, structuralism and gender and race studies, questioned the neutrality and factual accuracy of this ideology. Barr’s chart has been satirised as simplistic, as being too focused on white male Westerners, and too obsessed with formalist aesthetics. It has been remade and corrected in countless rival versions. It is, in short, out of fashion.

At the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, we have focused in recent years on the debate about modernism and an enlarged understanding of twentieth-century art: our exhibition Modern Scottish Women (2016) examined the overlooked role that women artists played in Scottish modern art, while True to Life: British Realist Painting in the 1920s and 1930s (2017) centred on artists who had no wish to be defined as modernists and had more in common with the artists of the early Italian Renaissance than they did with the Cubists. In A New Era: Scottish Modern Art 1900-1950, we are seeking to look at the area outlined by Barr of Fauvism, Cubism, abstraction and Surrealism in the first half of the twentieth century, but focusing on an area of that story that remains very little known: Scottish modernism. Although Scottish artists were not at the forefront of the European modernist movement, they contributed in a wide-ranging and meaningful way.

A New Era: Scottish Modern Art 1900-1950 by Alice Strang is out now published by National Galleries of Scotland Publishing priced £19.95.

A New Era: Scottish Modern Art 1900-1950 by Alice Strang is out now published by National Galleries of Scotland Publishing priced £19.95.

It accompanies the newly opened exhibition A New Era which runs until June 2018.

All spreads and images above are taken from the book. They are all © The National Galleries of Scotland.

If you enjoyed this article then you can read another extract here on Books from Scotland.

Featuring 50 stories of exploration over more than 200 years of human history, The Great Horizon is published in association with the Royal Scottish Geographical Society. The book features those who set out to conquer new territories and claim world records alongside those who contributed to our understanding of the world all but accidentally. Author Jo Woolf reveals how working on the book led to her own exploration and adventure.

Extract from The Great Horizon: 50 Tales of Exploration

By Jo Woolf

Published by Sandstone Press

In December 1913, when Sir Ernest Shackleton publicly announced his plans for the Endurance expedition to the Antarctic, he received nearly five thousand letters from hopeful applicants. Shortly afterwards, a friend noticed that these letters had been sorted into three large drawers in his desk, which he had labelled ‘Mad’, ‘Hopeless’ and ‘Possible’.

Shackleton could only accept fifty of those applications, and it is tempting to wonder how many from each category were successful. I would love to believe those he considered ‘mad’ stood the best chance of all.

When asked to imagine an explorer, we likely picture someone muffled in furs and battling Arctic winds, or perspiring in the heat as they hack their way through an equatorial jungle. Exploration seems to be a basic human instinct; the Phoenicians and ancient Greeks, the Romans, the Vikings and the Polynesians all set sail in a quest for new territory. This questing spirit is also seen in the European Age of Discovery which inspired Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama and Ferdinand Magellan. In more recent centuries, explorers such as James Cook, Mungo Park and John Franklin staked their lives – and lost them – in the great unknown.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, vast regions of the world still lay unexplored; there were, quite literally, blank spaces on the map. In the pure spirit of adventure, these attracted men and women whose curiosity spurred them to travel the unknown landscape, and tantalised the minds of scientists eager to expand and enhance their knowledge. Then there was political power; if a nation could plant a flag in these uncharted places, it could claim them as its own. Explorers often took on many roles, for example as scientists, cartographers, ethnographers, even negotiators and diplomats. Very often, therefore, their stories are linked with events in the wider world. In the late 1800s the ‘scramble for Africa’ saw European countries vying to claim slices of the continent for trade; meanwhile the ‘Great Game’ was playing out in Central Asia, as Russia and Britain manoeuvred for power in the Himalayas. This is true even of more modern figures; Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the moon were arguably precipitated by the Cold War.

Some found themselves especially drawn to those inhospitable parts of the globe where the extremes of climate made human survival all but impossible. The Arctic and the Antarctic captured the imagination. The discovery of the Northwest and Northeast Passages opened up shorter routes for trading vessels, while the Antarctic was identified as a vast continent. For a growing band of explorers, the ultimate prizes were the Poles.

In more recent decades, our perception of exploration has undergone a subtle change. The euphoria that greeted new ‘conquests’ in previous centuries has gradually been replaced by a sense of responsibility. As we begin to understand the absolute dependence of human life on the survival of our natural environment, the efforts of modern-day explorers are focused on enhancing our awareness and encouraging us to look ahead for the welfare of generations to come. Although Sir Patrick Geddes warned us that ‘environment and organism, place and people, are inseparable’ over a hundred years ago, we are only just beginning to appreciate the truth in his words.

The experience of the explorer himself has changed, too. From the time when voyagers would bid goodbye to their families and head off into the great unknown, with absolutely no contact for several years at a time, we have progressed into an era of digital technology which allows instant communication and precise global positioning. Increasingly, the feeling that those early pioneers must have known is going to be lost to us: their vulnerability, their total isolation. It took nearly eleven months for the news of Scott’s death to reach the outside world. Admiral Teddy Evans, along with Tom Crean and William Lashly, was one of the last people to see him alive; as the two groups parted ways and Scott’s men headed towards the South Pole, Evans watched them until they became specks on the ‘great white horizon’.

In 2014 I was invited to the headquarters of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, to discuss writing about some of their medal recipients. The long list of names, stretching back to the late 1800s from the present day, reads like a Who’s Who of exploration. Alongside the ‘greats’ of Scott, Shackleton and Amundsen were some unfamiliar names that invited further investigation. From that point I set out on my own journey of exploration.

The Great Horizon: 50 Tales of Exploration by Jo Woolf is out now published by Sandstone Press priced £24.99.

The Great Horizon: 50 Tales of Exploration by Jo Woolf is out now published by Sandstone Press priced £24.99.

Acclaimed author and translator Susan Rennie introduces The Twal Days o Yule and traces the linguistic origins of some of the words used, from bonnie doos to lassies birlin, in her Scots version of the much-loved Christmas song.

Translating The Twal Days o Yule: A Scots Rhyme for Christmas

By Susan Rennie

There have been a myriad merry versions of ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’, since its first known appearance in the 18th century. Some early versions have ducks a-quacking, hares a-running and bells a-ringing for the gifts, and even a juniper tree substituting for the pear. But what gifts should appear in a distinctively Scottish version, using Scots words and rhymes throughout? Some of the gifts in Twal Days were chosen for their wonderful sound and alliteration in Scots, some for their visual potential for a picture-book, and others for their links to Scottish culture and tradition – or ideally all three!

The terms Yule and Yuletide have been used in Scots since the Middle Ages to refer to the festive period, and their roots lie in the name of the Old Norse festival jól. An earlier Scottish version of the ‘Twelve Days’ rhyme was called ‘The Yule Days’ and featured in Robert Chambers’s Popular Rhymes of Scotland (1842). In this version, Yule lasts for thirteen days (up to and including 6th January), and the gifts are sent by the King to his lady and include some very exotic creatures: a papingo, the old Scots word for ‘parrot’, and even an Arabian baboon!

The King sent his lady on the first Yule day, A papingo-aye;

Wha learns my carol and carries it away?

Tempting as it was to revive the venerable papingo, I decided to use a native bird for my chorus. The lead actor in Twal Days is therefore the reid robin, who sits in a rowan tree – chosen partly of course for the alliteration, and partly because the rowan tree has long been a symbol of good fortune in Scotland, and would therefore make a braw Yuletide gift. Reid robins and robin reidbreists have featured in Scots literature for centuries, and the phrase as reid as the rowan is a traditional simile dating back to medieval Scots.

For the second day of Yuletide, there are bonnie doos instead of turtle doves. Doo is a very old Scots word for a dove or pigeon, and the phrase bonnie doo is also a traditional term of endearment, which fits in bonnily with the theme of the rhyme. The earliest known English version of the rhyme has ‘four colly birds’, where colly is an English dialect word for ‘black’, related to ‘coal’. The name of the Scots collie or sheep-dog is thought to have the same origin, from the black patches on its coat – so in Twal Days there are 4 collie dugs (helpful for rounding up the sheep-a-shooglin who appear on day 7).

It is thought that the original ‘Twelve Days’ rhyme may have come from France, and several of the Scots words in Twal Days have a French origin. The word hoolet is familiar from its eerie role in Tam o’ Shanter (‘Kirk-Alloway was drawing nigh, Whare ghaists and houlets nightly cry’), but it has been used in Scots since the Middle Ages and comes from the medieval French hulotte. One medieval Scots poem includes the wonderfully alliterative howland howlattis (‘howling owls’) – which is not too far from my modern 6 hoolets hootin. However, the ‘3 French hens’ of the rhyme switch nationality in Twal Days to become Scottish tappit hens – the Scots term for a hen with a distinctive tuft of feathers on its head. (In Scotland, a tappit hen also humorously refers to a decanter with a fancy top that looks like a tufted hen.)

On day 9, I have lassies birlin rather than ladies dancing, but some 19th-century versions have ‘ladies spinning’, so I am in good company there. Birl is a surprisingly modern word, having appeared in Scots in the 18th century. It is probably onomatopoeic in origin, like whirl or burr – or indeed skirl and dirl ‘reverberate’, which is what the pipers and drummers do on days 11 and 12. The words dirlin and skirlin are partly chosen for their rhyme – and there is a nod to Scots literary tradition, too. In Tam o’Shanter, Auld Nick famously ‘screw’d the pipes and gart them skirl, Till roof and rafters a’ did dirl.’ The Scots verb skirl has been used to describe the sound of the bagpipes since at least the 17th century. It is also used for the sizzling sounds of frying – hence the name skirlie for a dish of fried oats and skirling-pan, the evocative Scots name for a frying pan. (Fans of Roald Dahl might spot a resemblance to the BFG’s word sizzle-pan, here too!)

I strayed a wee bit further from tradition on days 7 and 8; rather than swans-a-swimming and maids a-milking there are sheep a-shooglin and skaters skooshin. The 8 skaters skooshin were unashamedly a homage to Henry Raeburn’s iconic painting of ‘The Skating Minister’– an image which the illustrator, Matthew Land managed to suggest brilliantly.

I strayed a wee bit further from tradition on days 7 and 8; rather than swans-a-swimming and maids a-milking there are sheep a-shooglin and skaters skooshin. The 8 skaters skooshin were unashamedly a homage to Henry Raeburn’s iconic painting of ‘The Skating Minister’– an image which the illustrator, Matthew Land managed to suggest brilliantly.

Check out author, Susan Rennie, who reads an extract from her Scots version of the classic Christmas song, with beautiful illustrations by Matthew Land in this video.

About the Book

The 12 Days o Yule is a stunningly illustrated Scots version of the traditional Christmas rhyme. Journey through the twelve days of Yuletide with a cast of skaters skooshin, lassies birlin, sheep a-shooglin and the all-important five gowden rings. The book by Susan Rennie, with illustrations by Matthew Land, is out now published by Floris Books priced £5.99.

About the Author

Susan Rennie lectures on the history of Scots and lexicography at Glasgow University. A renowned Scots language expert, she is a co-founder of Scots language publisher Itchy Coo and author of several Scots language books for children. She has translated several classic children’s books into Scots including The Tiger Who Came to Tea and We’re Going on a Bear Hunt.

Check out Floris Books on Facebook for details of an exclusive discount code which runs until 14 December.

Despite its name, ‘Moon gardening’ doesn’t involve sowing seeds by the light of the Moon. Explaining what Moon gardening really is, this practical introduction shows how it can benefit your horticultural activity.

What Is ‘Moon Gardening’ Anyway?

Despite its name, ‘Moon gardening’ doesn’t involve sowing seeds by the light of the Moon. It’s far more practical than that!

As every gardener knows, there’s no magic spell for a thriving garden. But there are ways to work in harmony with the earth and environment to help your garden reach its full potential. The Moon influences the Earth every day – it’s common knowledge that the Moon’s power shapes our water to create tides – so shouldn’t the Moon also affect other parts of the Earth and the water within it too?

Moon gardening – or ‘lunar gardening’ – is simply about adapting your daily gardening tasks in order to benefit from lunar patterns. Much like planting at the right time of year to fit climatic changes, its aim is to work with the Moon and environmental conditions to make the most of their positive influence.

Moon gardening works on the principle that the Moon moves through different phases, passing through the twelve zodiac constellations. As it does so, it influences different plants in different ways. There are four categories of plants – root, leaf, fruit and flower – which are designated according to the part of the plant that we usually eat or work with. They may sound familiar to anyone who has come across the biodynamic gardening movement founded by Maria Thun.

The relative position of the Moon to the Sun, the Earth, and through the seasons, has an impact on plant types in different ways. For example, in the lunar ‘spring’, the Moon rises for 13 and a half days, following the path taken by the Sun from December 21st to June 21st. During this time, sap usually rises in all plant life and increases their vivacity, so it’s a great time to make cuttings or grafts, harvest leafy plants and cut flowers for bouquets.

With specific guidelines on when to sow, plant and harvest throughout the year, the Moon gardening technique brings a new level of precision to gardening and helps you to get more out of your allotment or vegetable patch. By working at favourable times with your chosen crops, you can produce better tasting and more plentiful vegetables, as well as stronger, healthier plants and flowers.

Although it’s now slipped out of mainstream gardening, this age-old technique has a dedicated following. Based on over 35 years’ experience from French lunar gardener Céleste, the annual Jardinez Avec La Lune is bought by 100,000 people every year, with over 2 million copies sold in its lifetime.

For 2018, Floris Books has made this bestseller available in English for the first time in The Moon Gardener’s Almanac. Why not download our free January sampler and give it a try for yourself?

The Moon Gardeners’ Almanac is a practical guide to harnessing the Moon’s positive influence over plants and flowers as part of your everyday gardening work.

Fully illustrated with easy-to-follow diagrams and space for your own notes, this essential month-by-month guide makes it easy to plan your gardening tasks. It makes a perfect stocking filler for any gardener or allotment keeper this Christmas.

The Moon Gardener’s Almanac 2018 by Thérèse Trédoulat and translated by Mado Spiegler, is available now priced £8.99 from Floris Books.

by Thérèse Trédoulat and translated by Mado Spiegler, is available now priced £8.99 from Floris Books.

Check out Floris Books on Facebook for details of an exclusive discount code which runs until 14 December.

Taking a break from reviewing, our monthly columnist David Robinson charts the trajectory of nature writing from past to present. A best-selling genre in Scotland today, it shows no sign of abating in popularity, and now sees books by long-established authors such as John Lister-Kaye sit alongside those by newer voices such as Amy Liptrot and Victoria Whitworth.

Expressive Exploration: Mapping Scotland’s New Nature Writing

In August, at the 2017 Edinburgh International Book Festival, Scotland’s greatest living nature writer launched his memoir. Even in 1969, ten years after he wrote Ring of Bright Water (Longmans, 1960), Lister-Kaye’s mentor Gavin Maxwell would never have dreamed of writing about how the psychodramas of his own repressed homosexuality found expression in a deep love of otters. Back then, nature writing was a fusion of enchanted lyricism and descriptive accuracy, nothing at all to do with the writer’s psyche. Even the little Maxwell did reveal about himself in print was something he always regretted.

Lister-Kaye was in his early twenties in 1969 when he moved to Scotland to work with Maxwell, who died of lung cancer within months. ‘After the funeral,’ he told me, ‘I remember sitting with [Maxwell’s agent] Peter Janson-Smith, and he told me that the one line in Ring that Gavin always wished he hadn’t written was when he admitted that he cared more about Mijbil [his otter] than any human being.’

Why? ‘Because, in a sense, he was exposing himself as a recluse. And yet that’s just what he was. In both his next books Maxwell would complain bitterly about people who just turned up at Sandaig without prior notification.’ It’s a small point, but a telling one. Whatever other qualities British nature writing used to have four decades ago, openness and self-disclosure were not among them.

Now look at how much has changed. On its cover Lister-Kaye’s book is garlanded with praise. ‘No-one writes more movingly, or with such transporting skill,’ says Helen MacDonald, whose H is for Hawk (Vintage, 2014) is as much about overcoming grief as it is about training goshawks. ‘A great naturalist,’ adds Chris Packham, who in his own childhood memoir Fingers in the Sparkle Jar, revealed last year that he loved his dogs more than any other humans, and that he was suicidal when any of them died. This is a man who keeps his dog’s body in his fridge, who dedicates his book to them: while Maxwell regretted his limited emotional honesty about his love for his pet otters, Packham feels no such compunctions. That invisible barrier between writing about the inner and the outer world has vanished.

The book that made the biggest difference in breaking down that barrier, says Lister-Kaye, was The Nature Cure (Chatto & Windus, 2005) in which Richard Mabey, the doyen of British nature writing, revealed the full extent of the depression that had plagued him for two years. ‘Ever since then,’ says Lister-Kaye, ‘there has been an interest in nature writing that exposes people’s inner feelings.’

The latest expressions of that new emotional openness are many and various. Among writers based in Scotland, Sara Maitland, Kathleen Jamie, Linda Cracknell and Esther Woolfson certainly have a place on any such list. Special mention on it must go to the Orkney Polar Bears, a group of wild swimmers who meet weekly to take the plunge in the cold seas off the archipelago. These aren’t just wild swimmers; they are wildly literate ones too.

For proof, read – if you still haven’t – the 2016 Wainwright Prize-winning The Outrun (Canongate, 2016) by Amy Liptrot, which charts how getting closer to the natural world on Orkney helped her recover from a spiral of addiction into which she had fallen while in London. On Papa Westray, she began writing a column for the Caught by the River website, which since 2007 has been one of the leading forums for new British nature writing, and she then reworked some of those early columns – on wild swimming, listening for corncrakes, watching meteor showers – into her brilliantly written book about finding her own nature cure.

A quote from Liptrot – ‘Attentive, astute and beautiful. It expanded my mind and heart’ – adorns the cover of her fellow Orkney Polar Bear Victoria Whitworth’s Swimming with Seals (Head of Zeus, 2017). For Whitworth, wild swimming was what brought joy (through the release of what she calls ‘endolphins’) and a sense of being without boundaries to a life that had seemed to be narrowing into an unhappy marriage to a former monk. The new, emotionally open – and largely female – school of nature writing is spreading fast. Almost, I’m tempted to say, like a ring of bright water.

This article originally appeared in the Autumn/Winter print edition of New Books Scotland produced in partnership by Publishing Scotland and Creative Scotland.

Until recently Glasgow was a major European port. Newly updated from the original 1986 publication, Half Of Glasgow’s Gone describes the port’s heyday, decline, neglect and subsequent redevelopment.

Extract from Half Of Glasgow’s Gone

By Michael Dick

Published by Brown, Son and Ferguson

Having been brought up in the country, I did not have many opportunities to visit Glasgow Harbour as a youngster. However, I do have very vague recollections of a school trip in 1959 to Gourock, when one of the highlights was the cruise down-river from Glasgow. Clearer memories emerged from the early 1960’s when I began to holiday with relatives at Sandbank on the Holy Loch, and sometimes took the cruise on the Queen Mary II from Bridge Wharf or the up-river cruise from Dunoon.

My passion for ships developed during that period and these excursions gave me a very clear picture of the great volume of shipping using facilities on the River Clyde. Trading vessels, of course, were to be seen predominantly in the Harbour but in the general confines of the River there were also ships being repaired; being built; being fitted-out and, sadly, being broken up.

My last cruise down-river in 1969 showed little radical change from 1959 save the demise of several shipyards and the novelty of the container terminal at Greenock. Even then you could not imagine Glasgow being anything other than a thriving port.

In spite of being employed in the Inverclyde area since 1971, for a while I lost track of the changing situation, especially within the Harbour. It was an incident one day in 1982 that led to the subsequent research which made me aware of the current position. Although I had made numerous crossings of the Kingston Bridge over the years, it was only then – and quite by chance – that I caught a glimpse of the former Kingston Dock, from the south-bound carriageway. It lay far below the Bridge, by the south bank of the river amid an overgrown wilderness. This aroused my curiosity and a subsequent investigation revealed a similar position at Prince’s and Queen’s Docks and that any vessels at riverside berths were in fact laid up. The Harbour had certainly lapsed into a state of decline within a relatively short period.

I became determined to recapture some of the atmosphere of what was a lost era, unlikely to return – through photographs, anecdotes and reported incidents. The contrasting view today is presented mainly through photographs and although generally one of bleakness and desolation, there are many aspects which reflect positive developments – albeit not strictly maritime.

This is an enhanced and updated second edition of the second edition of the 1986 book. Many of its black and white photographs have been enlarged, and there is a new colour photograph section, plus an additional chapter on Glasgow’s dockers.

– Michael Dick January 2017

Half Of Glasgow’s Gone by Michael Dick is out now published by Brown, Son and Ferguson priced £16.50.

Half Of Glasgow’s Gone by Michael Dick is out now published by Brown, Son and Ferguson priced £16.50.

Gallery: A Life in Art is an autobiography by William Hardie, who handled thousands of pictures as a leading art dealer over a 50 year period. Here we explore his influential connection to two key artists – John Byrne and David Hockney.

Extract from Gallery: A Life In Art

By William Hardie

Published by Waverley Books

John Byrne

Earlier, we had shown John Byrne’s drawings for the TV drama series Tutti Frutti. Concurrently with the Hunter show, a little exhibition of Byrne’s drawings for his television series Your Cheatin’ Heart occupied the small gallery. John, with his customary attention to every detail no matter how minute, had drawn the protagonists of his drama in character and in costume. The drawings functioned both as storyboard and as illustrations for the book which accompanied the series, which was produced and brilliantly cast by John. The show gave career-defining roles to Emma Thompson, Richard Wilson and Robbie Coltrane and several other actors. Robbie Coltrane opened the show with a practised speech. Later, on a visit to his house outside Glasgow, I admired his collection of 1950s American automobiles which were in keeping with his kingsize frame.

[…] John Byrne had recently mentioned watercolours painted by himself, and my expectations were high when he telephoned to say that he had an exhibition ready for me. So I was puzzled when three tea chests containing John’s collection of silk handkerchiefs arrived at the gallery. ‘Where’s the show?’ quoth I. ‘In the boxes’. ‘Are they watercolours?’ ‘No, hankies’. ‘What’s the show called?’ ‘Hankies’. John then spent three days mostly recumbent on the gallery floor collaging the hankies into miraculously meaningful, decorative and even beautiful compositions, which were pressed behind plexiglass in frames. Again, they were bought in large numbers by his eager fans, and although neither of us became millionaires as a result, it was enormous fun to do this gloriously cheeky show.

I realized later that the handkerchiefs hadn’t as it were come from nowhere, apart from John’s secret hanky drawer and his favourite junk shop. There had been an earlier group of oil paintings, ostensibly self-portraits, which had featured forms broken up – that is too strong an expression, better might be ‘folded’ or ‘streamed’ – into shapes resembling scarves, pashminas, shawls, throws, chadors: the right word eludes me.

David Hockney

At that time I went to virtually every opera at Theatre Royal. Sometime in 1992 John Cox was asked by Covent Garden to produce Die Frau Ohne Schatten, composed by Richard Strauss. He engaged David Hockney again to design the sets and costumes, and began to commute to Los Angeles for conferences with Hockney and with the late Peter Hemmings, the very English head of the Los Angeles Opera Company. Since Cox over the years had urged me to do a show with David Hockney, I half in jest said to him on the eve of one of these visits, ‘Can I come too?’ To my considerable surprise he agreed. So it was ultimately Richard Strauss and Mozart who were responsible for our exhibition of new paintings by David Hockney.

Because of its location, the Beverly Hills Hotel, where Hockney had actually painted the wave pattern on the floor of the pool, was ruled out. As the purpose of all my visits to LA was to stick as close as I dared to David Hockney until he agreed to do the show with us, Sunset Boulevard at La Cienaga was an ideal location, near the artist’s house up in the Hollywood Hills. When nothing in particular was happening, the art museums were easily reached by car: the Getty at Malibu, the Norton Simon at Santa Monica, the LA County Museum of Art on Wilshire at Venice, and The Huntington Library and Art Collections (home of Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy) in Pasadena. One day I drove up the Pacific Coast Highway to Bakersfield to see the 1,000 giant orange umbrellas planted by Christo across many acres of Magic Mountain. This huge installation had to be seen from a car.

On my first morning in California I found myself breakfasting on the terrace of the Mondrian Hotel on Sunset Boulevard with John Cox’s brother, the sculptor Stephen Cox, who was also staying in the hotel, and whom I was meeting for the first time. We were joined at table by Liz Lopresti, who introduced herself as a psychologist who counselled the astronaut Buzz Aldrin. Even in Los Angeles it is a trifle unusual to meet someone who knows a man who has walked on the Moon. (I once saw the first man on the Moon, Neil Armstrong, emerging from St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh surrounded by photographers.) Liz took us on a tour of LA. Stephen and I went for a swim in the ocean, with the jets from LAX thundering overhead every other minute.

The Mondrian Hotel was David’s suggestion. It was modernist pastiche painted red, yellow and black in the style of the abstract painter Piet Mondrian and by the architect J.L. Sert. The hotel had 1930s decor, all chrome, black glass and mirrors, a stunning view over the city below to the ocean, and a very LA clientele: the elevator would either disgorge soberly suited Silicon Valley executives, or people in sneakers, shorts and t-shirts ready for the beach; one never knew which it was going to be.

But the swimming pool was tiny. The current Hockney swimming pool (which is not the one in the early paintings) beckoned from Hollywood Hills, and thither Stephen and I took a taxi with a Mexican driver who had no English and didn’t have a clue where he was going, finally arriving at David Hockney’s house late. John Cox, who had been at the Hockney compound for a week, did the introductions. David was affable but abstracted. He was focused on the opera design, and seemed to have little interest at that stage in my proposed exhibition. The visitors had a swim and lunch, after which David fell asleep.

Waiting by a pool fringed with palm trees for the phone to ring is an essential part of the Hollywood experience. Especially if one is trying to persuade a very famous artist to agree to an exhibition.

Gallery: A Life In Art by William Hardie is out now published by Waverley Books priced £14.99.

Gallery: A Life In Art by William Hardie is out now published by Waverley Books priced £14.99.

What mischief does Jack Frost get up to in the night? A brand new tale, told in Scots and accompanied by enchanting illustrations, reveals his capers by moonlight…

Nip Nebs

By Susi Briggs and Ruthie Redden

Published by Curly Tale Books

Nip Nebs by Susi Briggs and Ruthie Redden is published in December by Curly Tale priced £9.99.

Nip Nebs by Susi Briggs and Ruthie Redden is published in December by Curly Tale priced £9.99.

If you know a keen knitter then we have a hunch that they’ll love receiving Knit Your Own Scotland. We show you how to make Andy Murray, Nessie, William Wallace and more!

Take a look at the PDF above (click in to view it in fullscreen mode) to discover fun patterns to make your own William Wallace, Andy Murray, Nessie and many more!

Knit Your Own Scotland by Jackie Holt and Ruth Bailey is out now published by Black and White priced £9.99.

by Jackie Holt and Ruth Bailey is out now published by Black and White priced £9.99.

Adventurer and environmentalist Huw Kingston spent 363 days circumnavigating the Mediterranean by sea kayak, foot, ocean rowboat and bike from Turkey back to Turkey. The journey saw him travel 13,000km and encompassed 17 countries. In this candid video interview Huw discusses his incredible Mediterranean journey and wider career.

You can read an extract from Mediterranean: A Year Around A Charmed and Troubled Sea by Huw Kingston here on Books from Scotland. The book is out now published by Whittles priced £19.99.

You can read an extract from Mediterranean: A Year Around A Charmed and Troubled Sea by Huw Kingston here on Books from Scotland. The book is out now published by Whittles priced £19.99.

After 6,504 miles and 15 months Katharine Lowrie and her husband completed running the length of South America. This video of highlights from their adventure includes the couple’s journey through frozen mountains, lush jungles, and jam-packed cities, as well as showing some of amazing animals that they encountered, such as anteaters, macaws and giant stick insects.

Running South America: With My Husband and Other Animals by Katharine Lowrie is out now published by Whittles priced £19.99.

Running South America: With My Husband and Other Animals by Katharine Lowrie is out now published by Whittles priced £19.99.

Part biography, part plant atlas, The Sweet Pea Man tells the story of the Victorian plant hybridist Henry Eckford and his life as a breeder of the famous Grandiflora sweet peas. A must read for all fascinated by plants, we go back to Eckford’s beginnings in Edinburgh in 1823.

Extract from The Sweet Pea Man

By Graham Martin

Published by Scotland Street Press

Henry Eckford was born on Saturday 17th May, 1823, the seventh of the eight children of James and Isabel Eckford. In 1810, with Isabel possibly already pregnant the two had run off to nearby Edinburgh to marry. There was, however, a problem… ‘Married irregularly at Edinburgh July 31st, 1810 James Eckford and Isabel Perie both of this parish they compeared before the Session September 9th 1810 paid a fine for their irregularity and the modr. [moderator] declared them married persons.’ So runs the Cockpen Parish Register for 1810. An irregular marriage was one that was, or was considered to be, contrary to Church of Scotland rules. Perhaps the banns hadn’t been read to the congregation on consecutive Sundays. Pregnancy is an unlikely cause. If it had occurred it was extremely recent, was probably unknown and could be hidden if it was. Although it was customary to marry in one’s parish, it was common enough here for couples to go to Edinburgh to be married. For one thing it was cheaper. It was usual to seek permission to marry from one’s parents or employers, permission that James and Isabel may not have had. James was thirty and Isabel sixteen, just, which gives us a clue; perhaps James had a past that he hadn’t quite managed to keep covered? A few years before, one James Eckford had been fathering illegitimate children down in the borders, at Traquair Mill. Perhaps too, the gentle loosening of the church’s grip on the nation’s affairs saw the church zealous where its writ remained.

The couple’s first child, Elizabeth, was born the following spring, at Shiels in Cockpen. They had a further three boys before moving to Stenhouse in Liberton, (not to be confused with the larger Edinburgh suburb of Stenhouse) in 1818. Here they had another four children, Henry being the third. Their last child, Isabella, was born in January 1826. If all the children survived, Henry as one of the youngest would have had a lot of siblings to make a fuss over him. Unfortunately, his father couldn’t have done. At some time between April 1825 and January 1826, James Eckford died. Isabel now had eight children to bring up alone, though almost certainly with the help of the extended family. Henry must have exhibited an early fascination with flowers. Still in his cradle, his grandfather told his parents “if you make that boy anything but a gardener you’ll spoil him!”.

***